Chapter 2. Complexity

Complex: bad. Simple: good. We touched on this already, and it’s still true. We can measure complexity with some accuracy via static analysis. Measures such as JSLint, cyclomatic complexity, lines of code, and fan-in and fan-out are important. However, nothing measures complexity as accurately as showing your code to a coworker or colleague.

Code can be complex for a number of reasons, from the serious “this is a hairy algorithm” to the mundane “a JavaScript newbie wrote it and it’s nasty,” and everything in between. Analyzing the complexity of static code is a great starting point toward creating testable JavaScript.

Maintainable JavaScript is clear, consistent, and standards-based. Testable JavaScript is loosely coupled, short, and isolatable. The magic happens when your code is both maintainable and testable. Since you will spend about 50% of your time testing and debugging your code, which is significantly more time than you will spend coding it, you might as well make code maintenance as easy on yourself and others as possible.

Complexity is the bane of every software project. While some complexity is unavoidable, in many cases complexity can be avoided. Being able to recognize which parts of your application are complex, and understanding why, will allow you to reduce its overall complexity. As always, recognizing the problem is the first step toward fixing it.

It is also important to note that the algorithms your code relies on may be complex as well. In fact, typically these complex algorithms are what make your code unique and useful. If your core algorithms were not complex, someone probably would have already created your application. However, unavoidable (in fact, beneficial) algorithm complexity is no excuse for writing complicated code. Although the details, and perhaps the code, surrounding your algorithm may be complex, of course there is a lot more to your application than some core algorithms.

Code Size

As code size grows, code complexity increases and the number of people who understand the entire system shrinks. As the number of modules increases, integration testing becomes increasingly difficult and the number of module interaction permutations grows. It is not surprising, therefore, that the number-one indicator of bugs/bug potential is code size. The more code you have, the greater the chance it will have bugs in it. The total amount of code necessary for your project may not change, but the number of statements in a method can. The amount of code in each file is also changeable. Large methods are difficult to test and maintain, so make more small ones. In an ideal world, functions have no side effects and their return value(s) (if any) are completely dependent on their parameters. Code rarely gets to live in that world, but it is something to keep in mind while writing code, along with “how am I going to test this thing?”

One method that can keep functions minimally sized is command query separation. Commands are functions that do something; queries are functions that return something. In this world, commands are setters and queries are getters. Commands are tested using mocks and queries are tested using stubs (more on this in Chapter 4). Keeping these worlds separate, along with enhancing testability, can provide great scalability returns by ensuring that reads are separated from writes. Here is an example of command query separation using Node.js:

function configure(values) {

var fs = require('fs')

, config = { docRoot: '/somewhere' }

, key

, stat

;

for (key in values) {

config[key] = values[key];

}

try {

stat = fs.statSync(config.docRoot);

if (!stat.isDirectory()) {

throw new Error('Is not valid');

}

} catch(e) {

console.log("** " + config.docRoot +

" does not exist or is not a directory!! **");

return;

}

// ... check other values ...

return config;

}Let’s take a quick look at some test code for this function. In Chapter 4 we will discuss the syntax of these tests in greater detail, so for now we’ll just look at the flow:

describe("configure tests", function() {

it("undef if docRoot does not exist", function() {

expect(configure({ docRoot: '/xxx' })).toBeUndefined();

});

it("not undef if docRoot does exist", function() {

expect(configure({ docRoot: '/tmp' })).not.toBeUndefined();

});

it("adds values to config hash", function() {

var config = configure({ docRoot: '/tmp', zany: 'crazy' });

expect(config).not.toBeUndefined();

expect(config.zany).toEqual('crazy');

expect(config.docRoot).toEqual('/tmp');

});

it("verifies value1 good...", function() {

});

it("verifies value1 bad...", function() {

});

// ... many more validation tests with multiple expects...

});This function is doing too much. After setting default configuration

values, it goes on to check the validity of those values; in fact, the

function under test goes on to check five more values. The method is large

and each check is completely independent of the previous checks. Further,

all of the validation logic for each value is wrapped up in this single

function and it is impossible to validate a value in isolation. Testing

this beast requires many tests for each possible value for each

configuration value. Similarly, this function requires many unit tests,

with all of the validation tests wrapped up inside the unit tests for the

basic working of the function itself. Of course, over time more and more

configuration values will be added, so this is only going to get

increasingly ugly. Also, swallowing the thrown error in the try/catch

block renders the try/catch block useless. Finally, the return value

is confusing: either it is undefined if any value did not validate, or it

is the entire valid hash. And let’s not forget the side effects of the

console.log statements—but we will get

to that later.

Breaking this function into several pieces is the solution. Here is one approach:

function configure(values) {

var config = { docRoot: '/somewhere' }

, key

;

for (key in values) {

config[key] = values[key];

}

return config;

}

function validateDocRoot(config) {

var fs = require('fs')

, stat

;

stat = fs.statSync(config.docRoot);

if (!stat.isDirectory()) {

throw new Error('Is not valid');

}

}

function validateSomethingElse(config) { ... }Here, we split up the setting of the values (query, a return value) with a set of validation functions (commands, no return; possible errors thrown). Breaking this function into two smaller functions makes our unit tests more focused and more flexible.

We can now write separate, isolatable unit tests for each validation function instead of having them all within the larger “configure” unit tests:

describe("validate value1", function() {

it("accepts the correct value", function() {

// some expects

});

it("rejects the incorrect value", function() {

// some expects

});

});This is a great step toward testability, as the validation functions can now be tested in isolation without being wrapped up and hidden within the more general “configure” tests. However, separating setters from the validation now makes it possible to avoid validation entirely. While it may be desirable to do this, usually it is not. Here is where command query separation can break down—we do not want the side effect of setting the value without validating it simultaneously. Although separate validation functions are a good thing for testing, we need to ensure that they are called.

The next iteration might look like this:

function configure(values) {

var config = { docRoot: '/somewhere' };

for (var key in values) {

config[key] = values[key];

}

validateDocRoot(config);

validateSomethingElse(config);

...

return config;

}This new configuration function will either return a valid config object or throw an error. All of the

validation functions can be tested separately from the configure function itself.

The last bit of niceness would be to link each key in the config object to its validator function and keep

the entire hash in one central location:

var fields {

docRoot: { validator: validateDocRoot, default: '/somewhere' }

, somethingElse: { validator: validateSomethingElse }

};

function configure(values) {

var config = {};

for (var key in fields) {

if (typeof values[key] !== 'undefined') {

fields[key].validator(values[key]);

config[key] = values[key];

} else {

config[key] = fields[key].default;

}

}

return config;

}This is a great compromise. The validator functions are available separately for easier testing, they will all get called when new values are set, and all data regarding the keys is stored in one central location.

As an aside, there still is a problem. What is to stop someone from trying the following?

config.docRoot = '/does/not/exist';

Our validator function will not run, and now all bets are off. For

objects, there is a great solution: use the new ECMAScript 5 Object

methods. They allow object property creation with built-in validators,

getters, setters, and more, and all are very testable:

var obj = { realRoot : '/somewhere' };

Object.defineProperty(obj, 'docRoot',

{

enumerable: true

, set: function(value) {

validateDocRoot(value); this.realRoot = value; }

}

);Now the following:

config.docRoot = '/does/not/exist';

will run the set function, which

calls the validate function, which will

throw an exception if that path does not exist, so there is no escaping

the validation.

But this is weird. This assignment statement might now throw an

exception and will need to be wrapped in a try/catch

block. Even if you get rid of the throw, what do you now set config.docRoot to if validation fails?

Regardless of what you set it to, the outcome will be unexpected. And

unexpected outcomes spell trouble. Plus, the weirdness of the internal and

external names of docRoot versus

realRoot is confusing.

A better solution is to use private properties with public getters and setters. This keeps the properties private but everything else public, including the validator, for testability:

var Obj = (function() {

return function() {

var docRoot = '/somewhere';

this.validateDocRoot = function(val) {

// validation logic - throw Error if not OK

};

this.setDocRoot = function(val) {

this.validateDocRoot(val);

docRoot = val;

};

this.getDocRoot = function() {

return docRoot;

};

};

}());Now access to the docRoot

property is only possible through our API, which forces validation on

writes. Use it like so:

var myObject = new Obj();

try {

myObject.setDocRoot('/somewhere/else');

} catch(e) {

// something wrong with my new doc root

// old value of docRoot still there

}

// all is OK

console.log(myObject.getDocRoot());The setter is now wrapped in a try/catch

block, which is more expected than wrapping an assignment in a try/catch

block, so it looks sane.

But there is one more issue we can address—what about this?

var myObject = new Obj(); myObject.docRoot = '/somewhere/wrong'; // and then later... var dR = myObject.docRoot;

Gah! Of course, none of the methods in the API will know about or

use this spurious docRoot field created

erroneously by the user. Fortunately, there is a very easy fix:

var Obj = (function() {

return function() {

var docRoot = '/somewhere';

this.validateDocRoot = function(val) {

// validation logic - throw Exception if not OK

};

this.setDocRoot = function(val) {

this.validateDocRoot(val);

docRoot = val;

};

this.getDocRoot = function() {

return docRoot;

};

Object.preventExtensions(this)

};

}());Using Object.preventExensions

will throw a TypeError if anyone tries

to add a property to the object. The result: no more spurious properties.

This is very handy for all of your objects, especially if

you access properties directly. The interpreter will now catch any

mistyped/added property names by throwing a TypeError.

This code also nicely encapsulates command query separation with a

setter/getter/validator, all separate and each testable in isolation. The

validation functions could be made private, but to what end? It is best to

keep them public, not only so that they can be tested more easily, but

also because production code might want to verify whether a value is a

legitimate docRoot value or not without

having to explicitly set it on the object.

Here is the very clean test code—short, sweet, isolatable, and semantic:

describe("validate docRoot", function() {

var config = new Obj();

it("throw if docRoot does not exist", function() {

expect(config.validateDocRoot.bind(config, '/xxx')).toThrow();

});

it("not throw if docRoot does exist", function() {

expect(config.validateDocRoot.bind(config, '/tmp')).not.toThrow();

});

});Command query separation is not the only game in town and is not always feasible, but it is often a good starting point. Code size can be managed in a number of different ways, although breaking up code along command query lines plays to one of JavaScript’s great strengths: eventing. We will see how to use this to our advantage later in this chapter.

JSLint

While JSLint does not measure complexity directly, it does force you to know what your code is doing. This decreases complexity and ensures that you do not use any overly complicated or error-prone constructs. Simply put, it is a measure of code sanity. With inspiration from the original “lint” for C, JSLint analyzes code for bad style, syntax, and semantics. It detects the bad parts[3] of your code.

Refactoring bad code and replacing it with good code is the essence of testable JavaScript. Here is an example:

function sum(a, b) {

return

a+b;

}That example was simple enough. Let’s run it through JSLint:

Error:

Problem at line 2 character 5: Missing 'use strict' statement.

return

Problem at line 2 character 11: Expected ';' and instead saw 'a'.

return

Problem at line 3 character 8: Unreachable 'a' after 'return'.

a+b;

Problem at line 3 character 8: Expected 'a' at column 5,

not column 8.

a+b;

Problem at line 3 character 9: Missing space between 'a' and '+'.

a+b;

Problem at line 3 character 10: Missing space between '+' and 'b'.

a+b;

Problem at line 3 character 10: Expected an assignment or

function call and instead saw an expression.

a+b;Wow! Four lines of mostly nothing code generated seven JSLint

errors! What is wrong? Besides a missing use

strict statement, the biggest problem is the carriage return

character after the return. Due to

semicolon insertion, JavaScript will return undefined from this function. JSLint has caught

this error, and is complaining about other whitespace issues in this

function.

Not only is whitespace relevant for readability, but in this case it also causes an error that is very hard to track down. Use whitespace sanely, as JSLint requires; you cannot test what you cannot read and understand. Code readability is the fundamental step toward testable code. Programs are written for other programmers to maintain, enhance, and test. It is critically important that your code is readable. JSLint provides a good measure of readability (and sanity).

Here is the corrected code:

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}Let’s look at one more seemingly innocuous snippet:

for (var i = 0; i < a.length; i++)

a[i] = i*i;This time JSLint cannot even parse the entire chunk, and only gets this far:

Error:

Problem at line 1 character 6: Move 'var' declarations to the top

of the function.

for (var i = 0; i < a.length; i++)

Problem at line 1 character 6: Stopping. (33% scanned).The first issue is the var

declaration in the for loop. JavaScript

variables are all either global- or function-scoped. Declaring a variable

in a for loop does

not declare that variable for only the for loop. The variable is available inside the

function that contains the for loop. By

using this construct, you have just created a variable named i that is available anywhere throughout the

enclosing function. This is what JSLint is telling us about moving the

declaration to the top of the function. By writing the code this way, you

are confusing yourself and, even worse, the next programmer who maintains

this code.

While this is not mission-critical, you should get out of the habit of declaring variables anywhere other than at the beginning of a function. JavaScript variables are function-scoped, so be proud that you understand this key differentiator between JavaScript and other common languages! Move the declaration to the top of the enclosing function, where it makes sense.

OK, after we’ve moved the declaration up, JSLint now says the following:

Error:

Problem at line 2 character 28: Unexpected '++'.

for (i = 0; i < a.length; i++)

Problem at line 3 character 5: Expected exactly one space between

')' and 'a'.

a[i] = i*i;

Problem at line 3 character 5: Expected '{' and instead saw 'a'.

a[i] = i*i;

Problem at line 3 character 13: Missing space between 'i' and '*'.

a[i] = i*i;

Problem at line 3 character 14: Missing space between '*' and 'i'.

a[i] = i*i;JSLint is displeased with ++. The

prefix and postfix ++ and -- operators can be confusing. This may be their

least problematic form of usage and represents a very common programming

idiom, so perhaps JSLint is being a bit harsh here, but these operators are a holdover from C/C++ pointer arithmetic and

are unnecessary in JavaScript, so be wary of them. In cases when these

operators can cause confusion, be explicit about their use; otherwise, you

are probably OK. The Big Picture is that you must ensure that your code is

readable and understandable by others, so as usual, do not get too cute or

optimize prematurely.

JSLint also wants braces around all loops, so put braces around all your loops. Not only will the one line in your loop probably expand to more than one line in the future and trip someone up in the process, but also some static analysis tools (e.g., minifiers, code coverage generators, other static analysis tools, etc.) can get confused without braces around loops. Do everyone (including yourself) a favor, include them. The extra two bytes of “cost” this will incur are far outweighed by the readability of the resultant code.

Here is the JSLint-approved version of the preceding code:

for (i = 0; i < a.length; i = i + 1) {

a[i] = i * i;

}What is especially troubling about the original code is that there are no bugs in it! It will compile and run just fine, and will do what it was intended to do. But programs are written for other programmers, and the latent confusion and poor readability of the original code will become a liability as the codebase grows and the code is maintained by people other than the original author (or is maintained by the original author six months after he wrote it, when the intent is no longer fresh in his mind).

Rather than going through all of JSLint’s settings and exhortations, I’ll direct you to the JSLint website, where you can read about JSLint and its capabilities. Another good source of information is Crockford’s JavaScript: The Good Parts, which provides details on “good” versus “bad” JavaScript syntactic constructs. JSLint and Crockford’s book are great first steps toward testable JavaScript. JSLint can be a bit prescriptive for some; if you have a good reason to feel very strongly against what JSLint proposes and can articulate those feelings clearly to members of your group, check out JSHint, a fork of JSLint that is more flexible and forgiving than JSLint. JSLint can also read configuration settings in comments at the top of your JavaScript files, so feel free to tweak those. I recommend using a standard set of JSLint configuration options throughout your application.

As a quick aside, there is a larger problem here that JSLint cannot

resolve: use of a for loop is not

idiomatic JavaScript. Using the tools provided by the language clears up

just about all the issues JSLint had with the original loop:

a.forEach(function (val, index) {

a[index] = index * index;

});Use of the forEach method ensures

that the array value and index are scoped properly to just the function callback. Equally important is the fact

that this construct shows future maintainers of your code that you know

what you are doing and are comfortable with idiomatic JavaScript.

Although this immediately fixes all the issues we had with the

original code, at the time of this writing the forEach method unfortunately is not available

natively in all browsers—but not to worry! Adding it is simple; do not try

to write it yourself, but rather utilize Mozilla’s standards-based implementation. The

definition of the algorithm is here. It is important to note that the

callback function receives three arguments: the value, the current index,

and the object itself, not just the array element. While you can write a

barebones version of forEach in fewer

lines, do not be tempted to do this; use the standards-based version. You

can easily add this snippet of code to the top of your JavaScript to

ensure that forEach is available in

every context. Not surprisingly, IE 8 and earlier do not have native

forEach support. If you are sure your

code will not run in those environments or if you are writing server-side

JavaScript, you are good to go.

Unfortunately, adding this snippet of code will increase the size of the code that must be downloaded and parsed. However, after minification it compresses down to 467 bytes and will only be fully executed once on IE 8 and earlier.

This seems to be a good compromise, as the standard forEach method has a function-scoped index variable, so no attempted variable

declaration in the initializer is even possible. Plus, we don’t have to

deal with the ++ post-conditional, and

the braces are right there for you. Using the “good” features of

JavaScript and programming idiomatically always leads to cleaner and more

testable code.

In Chapter 8 we will integrate JSLint into our build to keep a close eye on our code.

Cyclomatic Complexity

Cyclomatic complexity is a measure of the number of independent paths through your code. Put another way, it is the minimum number of unit tests you will need to write to exercise all of your code. Let’s look at an example:

function sum(a, b) {

if (typeof(a) !== typeof(b)) {

throw new Error("Cannot sum different types!");

} else {

return a + b;

}

}This method has a cyclomatic complexity of 2. This means you will need to write two unit tests to test each branch and get 100% code coverage.

Note

In the preceding code, I used the !== operator even though typeof is guaranteed to return a string. While

not strictly necessary, in this case using !== and ===

is a good habit, and you should use them everywhere. The JSLint website

and Crockford’s JavaScript: The Good Parts provide

more details. Using strict equality will help you to more quickly

uncover bugs in your code.

Generating the cyclomatic complexity of your code is simple using a command-line tool such as jsmeter. However, determining what is optimal in terms of cyclomatic complexity is not so simple. For instance, in his paper “A Complexity Measure”, Thomas J. McCabe postulated that no method should have a cyclomatic complexity value greater than 10. Meanwhile, a study that you can read about states that cyclomatic complexity and bug probability will not correlate until cyclomatic complexity reaches a value of 25 or more. So why try to keep the cyclomatic complexity value less than 10? Ten is not a magic number, but rather a reasonable one, so while the correlation between code and bugs may not begin until cyclomatic complexity reaches 25, for general sanity and maintainability purposes keeping this number lower is a good idea. To be clear, code with a cyclomatic complexity value of 25 is very complex. Regardless of the number of bugs in that code currently, editing a method with that much complexity is almost assured to cause a bug. Table 2-1 shows how Aivosto.com measures “bad fix” probabilities as cyclomatic complexity increases.

Cyclomatic complexity | Bad fix probability |

1–10 | 5% |

20–30 | 20% |

> 50 | 40% |

Approaching 100 | 60% |

An interesting tidbit is apparent from this table: when fixing relatively simple code there is a 5% chance you will introduce a new bug. That is significant! The “bad fix” probability increases fourfold as cyclomatic complexity gets above 20. I have never seen a function with cyclomatic complexity reaching 50, let alone 100. If you see cyclomatic complexity approaching either of those numbers, you should scream and run for the hills.

Also, the number of unit tests necessary to test such a beast is prohibitive. As McCabe notes in the aforementioned paper, functions with complexities greater than 16 were also the least reliable.

Reading someone else’s code is the most reliable indicator of code quality and correctness (more on that later). The reader must keep track of what all the branches are doing while going over the code. Now, many scientists have conducted studies on short-term memory; the most famous of these postulates that humans have a working memory of “7 plus or minus 2” items (a.k.a. Miller’s Law),[4] although more recent research suggests the number is lower. However, for a professional programmer reading code, that cyclomatic complexity value can be higher for shorter periods of time, but it doesn’t have to be. Exactly what battle are you fighting to keep your code more complex? Keep it simple!

Large cyclomatic complexity values are usually due to a lot of

if/then/else

statements (or switch statements without

breaks for each case, but you are not using those as

they are not one of the “good parts,” right?). The simplest refactoring fix, then, is to break the method into smaller

methods or to use a lookup table. Here is an example of the former:

function doSomething(a) {

if (a === 'x') {

doX();

} else if (a === 'y') {

doY();

} else {

doZ();

}

}This can be refactored using a lookup table:

function doSomething(a) {

var lookup = { x: doX, y: doY }, def = doZ;

lookup[a] ? lookup[a]() : def();

}Note that by refactoring the conditional into a lookup table we have not decreased the number of unit tests that are necessary. For methods with a high cyclomatic complexity value, decomposing them into multiple smaller methods is preferable. Instead of a lot of unit tests for a single function, now you will have a lot of unit tests for a lot of smaller functions, which is significantly more maintainable.

Adding cyclomatic complexity checks as a precommit hook or a step in your build process is easy. Just be sure that you actually look at the output and act on it accordingly! For a preexisting project, break down the most complex methods and objects first, but not before writing unit tests! Certainly, the number-one rule of refactoring is “do no harm,” and you cannot be sure you are obeying this rule unless you have tests to verify the “before” and “after” versions of your code.

jscheckstyle is a very handy tool for computing the cyclomatic complexity of each of your functions and methods. In Chapter 8 we will integrate jscheckstyle with the Jenkins tool to flag code that may be overly complex and ripe for refactoring, but let’s sneak a quick peek at it now.

The following code will install the jscheckstyle package:

% sudo npm install jscheckstyle -gNow let’s run it against any JavaScript source file:

findresult-lm:~ trostler$ jscheckstyle firefox.js

The "sys" module is now called "util". It should have a similar

interface.

jscheckstyle results - firefox.js

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━┳┓

┃ Line ┃ Function ┃ Length ┃ Args ┃ Complex...

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 8 ┃ doSeleniumStuff ┃ 20 ┃ 0 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 26 ┃ anonymous ┃ 1 ┃ 0 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 31 ┃ startCapture ┃ 17 ┃ 1 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 39 ┃ anonymous ┃ 6 ┃ 1 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 40 ┃ anonymous ┃ 4 ┃ 1 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 44 ┃ anonymous ┃ 3 ┃ 1 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 49 ┃ doWS ┃ 40 ┃ 2 ┃ 2

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 62 ┃ ws.onerror ┃ 4 ┃ 1 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 67 ┃ ws.onopen ┃ 4 ┃ 1 ┃ 1

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 72 ┃ ws.onmessage ┃ 6 ┃ 1 ┃ 2

┣━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━╋┫

┃ 79 ┃ ws.onclose ┃ 9 ┃ 1 ┃ 1

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┻━━━━╋┛This outputs a list of all the functions present in the file, the number of lines in each function, the number of arguments for each function, and the cyclomatic complexity of each function. Note that the number of lines includes any blank lines and comments, so this measure is more relative than the other values, which are absolute.

Also note that in this output the bulk of these functions are contained

within other functions—in fact, there are only three top-level functions

in this file. The anonymous function on

line 26 is within the doSeleniumStuff

function. There are three anonymous

functions within the startCapture

function, and the doWS function

contains the four ws.* functions. This

tool unfortunately does not clearly capture the hierarchy of functions

within a file, so beware of it.

jscheckstyle can also output JSON and HTML using the —json and

—html command-line options.

A utility such as jscheckstyle provides you with an at-a-glance view of your underlying source code. While there are no absolutes when it comes to coding practice and style, cyclomatic complexity has been proven to be a valid measure of code complexity, and you would do well to understand its implications.

Reuse

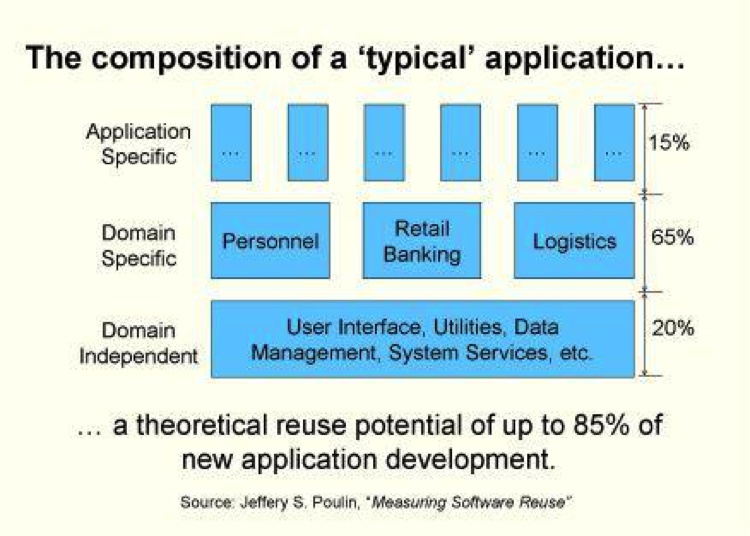

The best way to reduce code size is to decrease the amount of code you write. The theory is that using third-party (either external or internal) code that is production-ready and maintained by someone else takes a good chunk of responsibility away from you. Almost everyone uses third-party code, open source or not, in their programs. Jeffrey Poulin, while at Loral Federal Systems, estimated that up to 85% of code in a program is not application-specific; only 15% of the code in a program makes it unique. In his 1995 paper “Domain Analysis and Engineering: How Domain-Specific Frameworks Increase Software Reuse”, he says the following:

A typical application will consist of up to 20% general-purpose domain-independent software and up to another 65% of domain-dependent reusable software built specifically for that application domain. The remainder of the application will consist of custom software written exclusively for the application and having relatively little utility elsewhere.

He illustrates the three classes of software—application-specific, domain-specific, and domain-independent—as shown in Figure 2-1.

For JavaScript, the domain-independent code is the client-side framework such as YUI, or Node.js on the server side. The domain-specific software consists of other third-party modules you use in your application. You write the application-specific code.

Client-side JavaScript runs on many platforms (OS + browser combinations), and it would be insane for any web application to attempt to account for this. Using a good JavaScript framework is an absolute must in almost every circumstance. Frameworks such as YUI, Closure, and jQuery handle the bulk of the generic boilerplate code that makes application-specific code runnable across many platforms. Framework-provided façades give your code a consistent interface across browsers. Frameworks provide utilities, plug-ins, and add-ons that greatly reduce the size of your code. On the server side, Node.js uses the Node Package Manager tool (a.k.a. npm) to utilize modules uploaded to the npm registry (http://bit.ly/XUdvlF) in order to handle a large number of generic tasks.

Using event handling, a very basic and extremely important part of writing JavaScript, as an example, one can quickly see the dangers of not reusing code. While events are key to client-side JavaScript due to browser UIs, Node.js also makes extensive use of events and event callbacks. Yet there is nothing in the JavaScript language specification itself for handling events. These decisions were left up to the browser manufacturers, who were (and are) actively competing against one another. Not surprisingly, this led to fragmentation, until the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) stepped in and attempted to standardize client-side JavaScript events. Having to handle event registration and handler discrepancies in each browser is painful and very error-prone. Using a JavaScript framework solves these browser incompatibility problems for free. There are varying levels of support for the ECMAScript5 standard across browsers (especially Internet Explorer before version 9), so your favorite new language feature may not be present in a significant percentage of run-time environments. Do not get stuck supporting only one particular browser when you can support almost any modern browser, again for free, using a third-party framework.

Node.js also has a growing number of third-party modules that you can use via npm. A quick look at the npm registry shows the large number of modules available. Of course, the quality of the modules varies, but if nothing else, you can see how others have solved a problem similar to (if not the same as) yours to get you started.

Beyond basic JavaScript frameworks, there are a very large number of components available for use. It is your duty to use available prior art before attempting to roll your own code. Concentrate on the 15% that makes your application unique, and “offshore” the grunt work to well-established third-party libraries.

Equally important as reusing other people’s code is reusing your own code. In the Fan-In section we will discuss how you can discover code of yours that is not being reused properly (we will continue that discussion in Chapter 8, when we cover the dupfind tool). The general rule of thumb is that if you find that you are writing a chunk of code twice, it is time to pull the code into its own function. Whatever “extra” time you spend making the code sharable will pay dividends in the future. If the same chunk of code is required in two places, it will only be a matter of time before it is required in three places, and so on. Be vigilant about duplicated code. Do not let it slide “this one time.” As always, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, especially when debugging software.

Fan-Out

Fan-out is a measure of the number of modules or objects your function directly or indirectly depends on. Fan-out (and fan-in) were first studied in 1981 by Sallie Henry and Dennis Kafura, who wrote about them in “Software Structure Metrics Based on Information Flow,” published in IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. They postulated that 50% to 75% of the cost of software is due to maintenance, and they wanted to measure, as early as the design phase as possible, the complexity of software to be written. Building on previous work that demonstrated that greater complexity led to lower-quality software, they figured that if complexity could be measured and controlled while (or even before) the software was being built, everyone would win. They were familiar with McCabe’s work on measuring cyclomatic complexity and its relationship to software quality (published in 1976 and referenced earlier in this chapter) and other lexical analysis techniques, but they were convinced that they could get a better complexity measurement by measuring the underlying structure of the code instead of just counting tokens.

So, using information theory and analyzing flows between functions and modules, they cooked up a formula for a complexity measurement:

(fan_in * fan_out)2

They then calculated this value (and some variants) using the Unix OS and found a 98% correlation between it and “software changes” (i.e., bug fixes). To wit: the more complex a function or module measured by their formula, the more likely there were to be bugs in that function or module.

So, what the heck are fan-in and fan-out? Here is their definition of fan-out:

The fan-out of procedure A is the number of local flows from procedure A plus the number of data structures which procedure A updates.

In this definition, a local flow for A is counted as (using other methods B and C):

| 1 if A calls B |

| 2 if B calls A and A returns a value to B, which B subsequently utilizes |

| 3 if C calls both A and B, passing an output value from A to B |

So, adding all of those flows for function A, plus the number of global structures (external to A) that A updates, produces the fan-out for function A. Fan-in is defined similarly, as we will see shortly.

Calculating this value and the corresponding value for fan-in for all of your functions, multiplying those two numbers together, and squaring the result will give you another number that measures the complexity of a function.

Using this measure, Henry and Kafura note three problems inherent in highly complex code. First, high fan-in and fan-out numbers may indicate a function that is trying to do too much and should be broken up. Second, high fan-in and fan-out numbers can identify “stress points” in the system; maintaining these functions will be difficult as they touch many other parts of the system. And third, they cite inadequate refinement, which means the function needs to be refactored, because it is too big and is trying to do too much, or there is a missing layer of abstraction that is causing this function to have high fan-in and fan-out.

Building on function complexity measures, Henry and Kafura note that one can generate module complexity values, and from there one can measure the coupling between the modules themselves. Applying the lessons from the function level, one can determine which modules have high complexity and should be refactored or perhaps demonstrate that another layer of abstraction is necessary. They also found that typically the vast majority of a module’s complexity is due to a small number of functions (three!), regardless of the module’s size. So beware of the one “mongo” function that does way too much, while most of the other functions do very little!

Henry and Kafura also looked at function length (using lines of code) and found that only 28% of functions containing fewer than 20 lines of code had an error, whereas 78% of functions with more than 20 lines of code had errors. Keep it short and small, people!

Intuitively, it makes sense that functions with large fan-out are more problematic. JavaScript makes it very easy to declare and use global variables, but standards-based JavaScript tells us to not use the global space and instead to namespace everything locally. This helps to reduce fan-out by taking away part of the fan-out definition (“the number of data structures A updates”), but we still must account for our functions’ local flows.

You can inspect this easily by seeing how many foreign objects your

function requires. The following example uses YUI’s asynchronous require

mechanism to pull in the myModule chunk

of JavaScript code. A detailed discussion of this is available here; the main point to understand here

is that we are telling YUI about a dependency of our code, which YUI will

fetch for us. It will then execute our callback when the dependency has

been loaded:

YUI.use('myModule', function(Y) {

var myModule = function() {

this.a = new Y.A();

this.b = new Y.B();

this.c = new Y.C();

};

Y.MyModule = myModule;

}, { requires: [ 'a', 'b', 'c' ] });The fan-out for the myModule

constructor is 3 (in this case, the objects are not even being used; they

are just being created and stored for future methods, but they are still

required here, so they count against the constructor’s fan-out). And this

is without the constructor being instantiated and used yet. Three is not a

bad number, but again that number will grow when an outside object

instantiates myModule and uses any

return value from any local myModule

method it calls. Fan-out is a measure of what you need to keep track of in

your head as you edit this method. It is a count of the external methods

and objects this method manipulates.

Regardless of whether we are counting local flows, Miller’s Law argues that trying to remember and track more than seven things is increasingly difficult. Later reanalysis has brought that number down to four.[5] The point is that there is no specific number that is a danger indicator, but when fan-out is greater than 7 (or even 4) it is time to look at what is going on and possibly refactor. Excessive fan-out belies other issues, namely tight coupling, which we will also investigate in this chapter.

High fan-out can be problematic for even more reasons: the code is more complex, making it harder to understand and therefore test; each direct dependent must be mocked or stubbed out during testing, creating testing complexity; and fan-out is indicative of tight coupling, which makes functions and modules overly brittle.

A strategy to tame fan-out without eventing involves creating an object that encapsulates some of the fanned-out modules, leaving the original function with the single dependency on that new module. This obviously makes more sense as the fan-out of the original function increases, especially if the newly factored-out module can be reused by other functions as well.

Consider the following code, which has a fan-out of at least 8:

YUI.use('myModule', function(Y) {

var myModule = function() {

this.a = new Y.A();

this.b = new Y.B();

this.c = new Y.C();

this.d = new Y.D();

this.e = new Y.E();

this.f = new Y.F();

this.g = new Y.G();

this.h = new Y.H();

};

Y.MyModule = myModule;

}, { requires: [ 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h' ] });Testing this thing is going to be problematic; it needs to be refactored. The idea is to pull out a subset of related modules into another module:

YUI.use('mySubModule', function(Y) {

var mySubModule = function() {

this.a = new Y.A();

this.b = new Y.B();

this.c = new Y.C();

this.d = new Y.D();

};

mySubModule.prototype.getA = function() { return this.a; };

mySubModule.prototype.getB = function() { return this.b; };

mySubModule.prototype.getC = function() { return this.c; };

mySubModule.prototype.getD = function() { return this.d; };

Y.MySubModule = mySubModule;

}, { requires: [ 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] });

YUI.use('myModule', function(Y) {

var myModule = function() {

var sub = new Y.MySubModule();

this.a = sub.getA();

this.b = sub.getB();

this.c = sub.getC();

this.d = sub.getD();

this.e = new Y.E();

this.f = new Y.F();

this.g = new Y.G();

this.h = new Y.H();

};

Y.MyModule = myModule;

}, { requires: [ 'mySubModule', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h' ] });Here we have created a level of indirection between MyModule and modules a, b,

c, and d and reduced the fan-out by three, but has this

helped? Strangely, it has, a little. Even this brain-dead refactoring has

made our testing burden for MyModule

lighter. The total number of tests did increase a little because now

MySubModule must also be tested, but

the point is not to decrease the total amount of overall testing, but

instead to make it easier to test each module or function.

Clearly, this unsophisticated refactoring of MyModule to reduce its fan-out is not ideal. The

modules or objects that are refactored should in some way be related, and

the submodule they are refactored to should provide a more intelligent

interface to the underlying objects than just returning them whole cloth.

Using the façade pattern is really what is expected, wherein the

factored-out submodules are presented to the original module with a

simpler and more unified interface. Again, the total number of tests will

increase, but each piece will be easier to test in isolation. Here is a

quick example:

function makeChickenDinner(ingredients) {

var chicken = new ChickenBreast()

, oven = new ConventionalOven()

, mixer = new Mixer()

, dish = mixer.mix(chicken, ingredients)

return oven.bake(dish, new FDegrees(350), new Timer("50 minutes"));

}

var dinner = makeChickenDinner(ingredients);This function fans out like crazy. It creates

five external objects and calls two methods on two different objects. This

function is tightly coupled to five objects. Testing

it is difficult, as you will need to stub in all the objects and the

queries being made to them. Mocking the mixer’s mix method and the oven’s bake method will be difficult, as both return

values as well. Let’s see what a unit test for this function might look

like:

describe("test make dinner", function() {

// Mocks

Food = function(obj) {};

Food.prototype.attr = {};

MixedFood = function(args) {

var obj = Object.create(Food.prototype);

obj.attr.isMixed = true; return obj;

};

CookedFood = function(dish) {

var obj = Object.create(Food.prototype);

obj.attr.isCooked = true; return obj;

};

FDegrees = function(temp) { this.temp = temp };

Meal = function(dish) { this.dish = dish };

Timer = function(timeSpec) { this.timeSpec = timeSpec; };

ChickenBreast = function() {

var obj = Object.create(Food.prototype);

obj.attr.isChicken = true; return obj;

};

ConventionalOven = function() {

this.bake = function(dish, degrees, timer) {

return new CookedFood(dish, degrees, timer);

};

};

Mixer = function() {

this.mix = function(chicken, ingredients) {

return new MixedFood(chicken, ingredients);

};

};

Ingredients = function(ings) { this.ings = ings; };

// end Mocks

it("cooked dinner", function() {

this.addMatchers({

toBeYummy: function(expected) {

return this.actual.attr.isCooked

&& this.actual.attr.isMixed;

}

});

var ingredients = new Ingredients('parsley', 'salt')

, dinner = makeChickenDinner(ingredients)

;

expect(dinner).toBeYummy();

});

});Wow, that is a lot of code! And what are we actually testing here?

We had to mock out all referenced objects and their referenced objects,

plus create a new Ingredients object to

execute the makeChickenDinner method,

which then instantiates and utilizes our mocked-up object hierarchies.

Mocking and replacing all of those other objects is a lot of work to just

unit-test a single method. The whole thing is problematic. Let’s refactor

it and make it testable.

This function requires five objects—ChickenBreast, ConventionalOven, Mixer, FDegrees, and Timer—and five is near the upper limit of

fan-out that is comfortable. Not only is the fan-out high, but also the

coupling is very tight for all of those objects. Coupling and fan-out

usually go hand in hand, but not always. We can reduce coupling via

injection or eventing, and we can reduce fan-out by using façades that

encompass multiple objects. We will investigate coupling more fully later

in this chapter.

The first façade that we can create involves the oven. Creating an oven, setting its temperature, and setting its timer are ripe for abstraction. Then we inject the façade to reduce the coupling, which leaves us with this:

function Cooker(oven) {

this.oven = oven;

}

Cooker.prototype.bake = function(dish, deg, timer) {

return this.oven.bake(dish, deg, timer);

};

Cooker.prototype.degrees_f = function(deg) {

return new FDegrees(deg);

};

Cooker.prototype.timer = function(time) {

return new Timer(time);

};

function makeChickenDinner(ingredients, cooker) {

var chicken = new ChickenBreast()

, mixer = new Mixer()

, dish = mixer.mix(chicken, ingredients)

return cooker.bake(dish

, cooker.degrees_f(350)

, cooker.timer("50 minutes")

);

}

var cooker = new Cooker(new ConventionalOven())

, dinner = makeChickenDinner(ingredients, cooker);makeChickenDinner now has two

tightly coupled dependencies, ChickenBreast and Mixer, and an injected façade to handle the

cooking chores. The façade does not expose the entire API of the oven,

degrees, or timer, just enough to get the job done. We have really just

spread the dependencies around more evenly, making each function easier to

test and less tightly coupled, with less fan-out.

Here is the new test code for our refactored method:

describe("test make dinner refactored", function() {

// Mocks

Food = function() {};

Food.prototype.attr = {};

MixedFood = function(args) {

var obj = Object.create(Food.prototype);

obj.attr.isMixed = true;

return obj;

};

CookedFood = function(dish) {

var obj = Object.create(Food.prototype);

obj.attr.isCooked = true;

return obj;

};

ChickenBreast = function() {

var obj = Object.create(Food.prototype);

obj.attr.isChicken = true;

return obj;

};

Meal = function(dish) { this.dish = dish };

Mixer = function() {

this.mix = function(chicken, ingredients) {

return new MixedFood(chicken, ingredients);

};

};

Ingredients = function(ings) { this.ings = ings; };

// end Mocks

it("cooked dinner", function() {

this.addMatchers({

toBeYummy: function(expected) {

return this.actual.attr.isCooked

&& this.actual.attr.isMixed;

}

});

var ingredients = new Ingredients('parsley', 'salt')

, MockedCooker = function() {};

// Local (to this test) mocked Cooker object that can actually

// do testing!

MockedCooker.prototype = {

bake: function(food, deg, timer) {

expect(food.attr.isMixed).toBeTruthy();

food.attr.isCooked = true;

return food

}

, degrees_f: function(temp) { expect(temp).toEqual(350); }

, timer: function(time) {

expect(time).toEqual('50 minutes');

}

};

var cooker = new MockedCooker()

, dinner = makeChickenDinner(ingredients, cooker)

;

expect(dinner).toBeYummy();

});

});This new test code got rid of several generically mocked-out objects

and replaced them with a local mock that is specific to this test and can

actually do some real testing using expects within the mock itself.

This is now much easier to test as the Cooker object does very little. We can go

further and inject FDegrees and

Timer instead of being tightly coupled

to them. And of course, we can also inject or create another façade for

Chicken and maybe Mixer—you get the idea. Here’s the ultimate

injected method:

function makeChickenDinner(ingredients, cooker, chicken, mixer) {

var dish = mixer.mix(chicken, ingredients);

return cooker.bake(dish

, cooker.degrees_f(350)

, cooker.timer('50 minutes')

);

}Here are the dependencies we injected (we will discuss dependency injection fully in just a bit) and the corresponding code to test them:

describe("test make dinner injected", function() {

it("cooked dinner", function() {

this.addMatchers({

toBeYummy: function(expected) {

return this.actual.attr.isCooked

&& this.actual.attr.isMixed;

}

});

var ingredients = ['parsley', 'salt']

, chicken = {}

, mixer = {

mix: function(chick, ings) {

expect(ingredients).toBe(ings);

expect(chicken).toBe(chick);

return { attr: { isMixed: true } };

}

}

, MockedCooker = function() {}

;

MockedCooker.prototype = {

bake: function(food, deg, timer) {

expect(food.attr.isMixed).toBeTruthy();

food.attr.isCooked = true;

return food

}

, degrees_f: function(temp) { expect(temp).toEqual(350); }

, timer: function(time) {

expect(time).toEqual('50 minutes');

}

};

var cooker = new MockedCooker()

, dinner = makeChickenDinner(ingredients, cooker

, chicken, mixer)

;

expect(dinner).toBeYummy();

});

});All of the generic mocks are gone and the test code has full control over the mocks passed in, allowing much more extensive testing and flexibility.

When injecting and creating façades, it can become a game to see how far back you can pull object instantiation. As you head down that road, you run directly into the ultimate decoupling of event-based architectures (the subject of the next chapter).

Some may argue that abstracting functionality away behind façades makes code more complex, but that is not true. What we have done here is created smaller, bite-sized pieces of code that are significantly more testable and maintainable than the original example.

Fan-In

Most of what we discussed about fan-out also applies to fan-in, but not everything. It turns out that a large fan-in can be a very good thing. Think about common elements of an application: logging, utility routines, authentication and authorization checks, and so on. It is good for those functions to be called by all the other modules in the application. You do not want to have multiple logging functions being called by various pieces of code—they should all be calling the same logging function. That is code reuse, and it is a very good thing.

Fan-in can be a good measure of the reuse of common functions in code, and the more the merrier. In fact, if a common function has very low fan-in, you should ensure that there is no duplicated code somewhere else, which hinders code reuse.

In some cases, though, high fan-in is a bad thing. Uncommon and nonutility functions should have low fan-in. High(er) levels of code abstraction should also have low fan-in (ideally, a fan-in of 0 or 1). These high-level pieces of code are not meant to be used by lots of other pieces of code; typically they are meant to be used by just one other piece, usually to get them started once and that is it.

Here is the “official” fan-in definition:

The fan-in of procedure A is the number of local flows into procedure A plus the number of data structures from which procedure A retrieves information.

You get the idea: watch out for a piece of code that has large fan-in and large fan-out, as this is not desirable due to the high complexity and high amount of coupling that result.

Fan-in helps you identify code reuse (or not). Code reuse is good; scattered logging and debugging functions across your code are bad. Learn to centralize shared functions (and modules) and use them!

Coupling

While fan-out counts the number of dependent modules and objects required for a module or function, coupling is concerned with how those modules are put together. Submodules may reduce the absolute fan-out count, but they do not reduce the amount of coupling between the original module and the original dependent. The original module still requires the dependent; it is just being delivered via indirection instead of explicitly.

Some metrics try to capture coupling in a single number. These metrics are based on the six levels of coupling defined by Norman Fenton and Shari Lawrence Pfleeger in Software Metrics: A Rigorous & Practical Approach, 2nd Edition (Course Technology) way back in 1996. Each level is given a score—the higher the score, the tighter the coupling. We will discuss the six levels (from tightest to loosest) in the following subsections.

Content Coupling

Content coupling, the tightest form of coupling, involves actually calling

methods or functions on the external object or directly changing its

state by editing a property of the external object. Any one of the

following examples is a type of content coupling with the external

object O:

O.property = 'blah'; // Changing O's state directly

// Changing O's internals

O.method = function() { /* something else */ };

// Changing all Os!

O.prototype.method = function() { /* switcheroo */ };All of these statements content-couple this object to O. This kind of coupling scores a 5.

Common Coupling

Slightly lower on the coupling spectrum is common coupling. Your object is commonly coupled to another object if both objects share a global variable:

var Global = 'global';

Function A() { Global = 'A'; };

Function B() { Global = 'B'; };Here objects A and B are commonly coupled. This scores a

4.

Control Coupling

Next up is control coupling, a slightly looser form of coupling than common

coupling. This type of coupling controls how the external object acts

based on a flag or parameter setting. For example, creating a singleton

abstract factory at the beginning of your code and passing in an

env flag telling it how to act is a

form of control coupling:

var absFactory = new AbstractFactory({ env: 'TEST' });This scores a big fat 3.

Stamp Coupling

Stamp coupling is passing a record to an external object that only uses part of the record, like so:

// This object is stamp coupled to O

O.makeBread( { type: wheat, size: 99, name: 'foo' } );

// Elsewhere within the definition of O:

O.prototype.makeBread = function(args) {

return new Bread(args.type, args.size);

}Here we pass a record to the makeBread function, but that function only

uses two of the three properties within the record. This is stamp

coupling. Stamp coupling scores a 2.

Data Coupling

The loosest coupling of them all is data coupling. This type of coupling occurs when objects pass messages to one another, with no transfer of control to the external object. We will investigate this much further in Chapter 3. Data coupling scores a measly 1.

No Coupling

The last form of coupling (and my personal favorite), with absolutely zero coupling whatsoever between two objects, is the famed “no coupling.” No coupling scores a perfect 0.

Instantiation

While not formally a part of the coupling jargon, the act of instantiating a

nonsingleton global object is also a very tight form of coupling, closer

to content coupling than common coupling. Using new or Object.create creates a one-way, tightly coupled relationship between the

objects. What the creator does with that object determines whether the

relationship goes both ways.

Instantiating an object makes your code responsible for that object’s life cycle. Specifically, it has just been created by your code, and your code must now also be responsible for destroying it. While it may fall out of scope when the enclosing function ends or closes, any resources and dependencies the object requires can still be using memory—or even be executing. Instantiating an object foists responsibilities on the creator of which you must be aware. Certainly, the fewer objects your code instantiates, the clearer your conscience will be. Minimizing object instantiations minimizes code complexity; this is a nice target to aim for. If you find that you are creating a lot of objects, it is time to step back and rethink your architecture.

Coupling Metrics

The point of naming and scoring each type of coupling, besides giving us all a common frame of reference, is to generate metrics based on coupling found in functions, objects, and modules. An early metric calculates the coupling between two modules or objects by simply adding up the number of interconnections between the modules or objects and throwing in the maximum coupling score.[6] Other metrics try to measure the coupling inherent in a single module.[7] A matrix has also been created between all modules in an application to view the overall coupling between each of them.[8]

The point here is that a number or set of numbers can be derived to determine how tightly or loosely coupled a system or set of modules is. This implies that someone “above” the system is trying to determine its state. For our purposes, we are the programmers looking at this stuff every day. Once we know what to look for, we can find it and refactor if necessary. Again, code inspections and code reviews are an excellent way to find code coupling, instead of relying on a tool to root out coupling metrics.

Coupling in the Real World

Let’s look at some examples of coupling in JavaScript. The best way to understand loose coupling is to take a look at tight coupling:

function setTable() {

var cloth = new TableCloth()

, dishes = new Dishes();

this.placeTableCloth(cloth);

this.placeDishes(dishes);

}This helper method, presumably belonging to a Table class, is trying to set the table nicely.

However, this method is tightly coupled to both the

TableCloth and Dishes objects. Creating new objects within

methods creates a tight coupling.

This method is not isolatable due to the tight coupling—when I’m

ready to test it I also need the TableCloth and Dishes objects. Unit tests really want to test

the setTable method in isolation from

external dependencies, but this code makes that difficult.

As we saw in the cooking example earlier, globally mocking out the

TableCloth and Dishes objects is painful. This makes testing

more difficult, although it is certainly possible given JavaScript’s

dynamic nature. Mocks and/or stubs can be dynamically injected to handle

this, as we will see later. However, maintenance-wise this situation is

less than ideal.

We can borrow some ideas from our statically typed language friends and use injection to loosen the coupling, like so:

function setTable(cloth, dishes) {

this.placeTableCloth(cloth);

this.placeDishes(dishes);

}Now testing becomes much simpler, as our test code can just pass in mocks or stubs directly to the method. Our method is now much easier to isolate, and therefore much easier to test.

However, in some instances this approach will just push the problem farther up the stack. Something, somewhere is going to have to instantiate the objects we need. Won’t those methods now be tightly coupled?

In general, we want to instantiate objects as high as possible in the call stack. Here is how this method would be called in an application:

function dinnerParty(guests) {

var table = new Table()

, invitations = new Invitations()

, ingredients = new Ingredients()

, chef = new Chef()

, staff = new Staff()

, cloth = new FancyTableClothWithFringes()

, dishes = new ChinaWithBlueBorders()

, dinner;

invitations.invite(guests);

table.setTable(cloth, dishes);

dinner = chef.cook(ingredients);

staff.serve(dinner);

}This issue here, of course, is what if we wanted to have a more casual dinner party and use a paper tablecloth and paper plates?

Ideally, all our main objects would be created up front at the top of our application, but this is not always possible. So, we can borrow another pattern from our statically typed brethren: factories.

Factories allow us to instantiate objects lower in the call stack

but still remain loosely coupled. Instead of an explicit dependency on an

actual object, we now only have a dependency on a Factory. The Factory has dependencies on the objects it

creates; however, for testing we introduce a Factory that creates mocked or stubbed objects,

not the real ones. This leads us to the end of this line of thinking:

abstract factories.

Let’s start with just a regular Factory:

var TableClothFactory = {

getTableCloth: function(color) {

return Object.create(TableCloth,

{ color: { value: color }});

}

};I have parameterized the tablecloth’s color in our Factory—the parameter list to get a new instance

mirrors the constructor’s parameter list. Using this Factory is straightforward:

var tc = TableClothFactory.getTableCloth('purple');For testing, we do not want an actual TableCloth object. We are trying to test our

code in isolation. We really just want a mock or a stub instead:

var TableClothTestFactory = {

getTableCloth: function(color) {

return Y.Mock(); // Or whatever you want

};Here I’m using YUI’s excellent mocking framework. We will

investigate this deeper in Chapter 4. The code

looks almost exactly the same to get a mocked version of a TableCloth object:

var tc = TableClothTestFactory.getTableCloth('purple');If only there were some

way to reconcile these two factories so that our code always

does the right thing... Of course, there is: all we need to do is create a

factory to generate the appropriate TableCloth factory, and then we’ll really have

something!

var AbstractTableClothFactory = {

getFactory: function(kind) {

if (kind !== 'TEST') {

return TableClothFactory;

} else {

return TableClothTestFactory;

}

}

};All we did here was parameterize a Factory so that it returns an actual Factory that in turn returns the kind of

TableCloth object requested. This

monster is called an abstract factory.

For testing, we just want a mocked object; otherwise, we want the real

deal. Here is how we use it in a test:

var tcFactory = AbstractTableClothFactory.getFactory('TEST')

, tc = tcFactory.getTableCloth('purple');

// We just got a Mock'ed object!Now we have a way to instantiate objects without being tightly coupled to them. We have moved from very tight content coupling to much looser control coupling (that’s two less on the coupling scale; woo!). Testing now becomes much simpler, as we can create versions of factories that return mocked versions of objects instead of the “real” ones, which enables us to test just our code, without having to worry about all of our code’s dependencies.

Testing Coupled Code

It is interesting to note the type and amount of testing required to test the various levels of coupled code. Not too surprisingly, the more tightly coupled the code is, the more resources are required to test it. Let’s go through the levels.

Content-coupled code is difficult to test because unit testing wants to test code in isolation, but by definition content-coupled code is tightly coupled with at least one other object external to it. You need the entire set of unit-testing tricks here to try to test this code; typically you must use both mocked objects and stubs to replicate the environment within which this code expects to run. Due to the tight coupling, integration testing is also necessary to ensure that the objects work together correctly.

Commonly coupled code is easier to unit-test as the shared global variable can be easily mocked or stubbed out and examined to ensure that the object under test is reading, writing, and responding to that variable correctly.

Control-coupled code requires mocking out the controlled external object and verifying it is controlled correctly, which is easy enough to accomplish using a mock object.

Stamp-coupled code is easily unit-tested by mocking out the external object and verifying the passed parameter was correct.

Data-coupled code and noncoupled code are very easily tested through unit testing. Very little or nothing needs to be mocked or stubbed out, and the method can be tested directly.

Dependency Injection

We touched on injection only briefly earlier, so let’s take a closer look at it now. Dependencies make code complex. They make building more difficult, testing more difficult, and debugging more difficult; pretty much everything you would like to be simpler, dependencies make harder. Managing your code’s dependencies becomes an increasingly larger time sink as your application grows.

Injection and mocking are loosely related. Injection deals with constructing and injecting objects into your code, and mocking is replacing objects or method calls with canned dummy versions for testing. You could (and should!) use an injector to insert mocked versions of objects into your code for testing. But you should not use a mocking framework in production code!

Factoring out dependencies or manually injecting them into constructors or method calls helps to reduce code complexity, but it also adds some overhead: if an object’s dependencies are to be injected, another object is now responsible for correctly constructing that object. Haven’t we just pushed the problem back another layer? Yes, we have! The buck must stop somewhere, and that place is typically at the beginning of your application or test. Maps of object construction are dynamically defined up front, and this allows any object to be easily swapped out for another. Whether for testing or for upgrading an object, this is a very nice property to have.

A dependency injector can construct and inject fully formed objects into our code for us. Of course, an injector must be told how to actually construct these objects, and later, when you actually want an instance of that object, the injector will hand you one. There is no “magic” (well, perhaps a little); the injector can only construct objects you specify. Injectors get fancy by providing lots of different ways to describe exactly how your objects are constructed, but do not get lost in the weeds: you tell the injector how to construct an object (or have the injector pass control to your code to construct an object).

There is one more bit that injectors handle along with object construction: scope. Scope informs the injector whether to create a new instance or reuse an existing one. You tell the injector what scope each object should have, and when your code asks for an object of that type the injector will do the right thing (either create a new instance or reuse an existing one).

In Java this is all accomplished by subclasses and interfaces—the

dependent needs an instance of an interface or superclass, and the

injector supplies a concrete instantiation of an implementing class or

specific subclass. These types can be (mostly) checked at compile time,

and injectors can guard against passing in null objects. While JavaScript

does have the instanceof operator, it

has neither type checking nor the notion of implementing an interface

type. So, can we use dependency injection in JavaScript? Of course!

We know that instantiating dependent objects in constructors (or elsewhere within an object) tightly couples the dependency, which makes testing more difficult—so let the injector do it.

Let’s take a brief look at knit, a Google Guice-like injector for JavaScript. We know this code is “bad”:

var SpaceShuttle = function() {

this.mainEngine = new SpaceShuttleMainEngine();

this.boosterEngine1 = new SpaceShuttleSolidRocketBooster();

this.boosterEngine2 = new SpaceShuttleSolidRocketBooster();

this.arm = new ShuttleRemoteManipulatorSystem();

};With all of those objects being instantiated within the constructor,

how can we test a SpaceShuttle without

its real engines and arm? The first step is to make this constructor

injectable:

var SpaceShuttle = function(mainEngine, b1, b2, arm) {

this.mainEngine = mainEngine;

this.boosterEngine1 = b1;

this.boosterEngine2 = b2;

this.arm = arm;

};Now we can use knit to define how we want our

objects constructed:

knit = require('knit');

knit.config(function (bind) {

bind('MainEngine').to(SpaceShuttleMainEngine).is("construtor");

bind('BoosterEngine1').to(SpaceShuttleSolidRocketBooster)

.is("constructor");

bind('BoosterEngine2').to(SpaceShuttleSolidRocketBooster)

.is("constructor");

bind('Arm').to(ShuttleRemoteManipulatorSystem).is("constructor");

bind('ShuttleDiscovery').to(SpaceShuttle).is("constructor");

bind('ShuttleEndeavor').to(SpaceShuttle).is("constructor");

bind('Pad').to(new LaunchPad()).is("singleton");

});Here, the SpaceShuttleMainEngine,

SpaceShuttleSolidRocketBooster, and

ShuttleRemoteManipulatorSystem objects

are defined elsewhere, like so:

var SpaceShuttleMainEngine = function() {

...

};Now whenever a MainEngine is

requested, knit will fill it in:

var SpaceShuttle = function(MainEngine

, BoosterEngine1

, BoosterEngine2

, Arm) {

this.mainEngine = MainEngine;

...

}So the entire SpaceShuttle object

with all of its dependencies is available within the knit.inject method:

knit.inject(function(ShuttleDiscovery, ShuttleEndeavor, Pad) {

ShuttleDiscovery.blastOff(Pad);

ShuttleEndeavor.blastOff(Pad);

});knit has recursively figured out all of SpaceShuttle’s dependencies and constructed

SpaceShuttle objects for us. Specifying

Pad as a singleton ensures that any

request for a Pad object will always

return that one instantiation.

Suppose as time passes, Mexico creates an even more awesome ShuttleRemoteManipulatorSystem than Canada’s.

Switching to use that arm instead is trivial:

bind('Arm').to(MexicanShuttleRemoteManipulatorSystem).is("constructor");Now all objects that require an Arm will get Mexico’s version instead of

Canada’s without changing any other code.

Besides swapping out objects easily for newer or different versions, an injector framework can also inject mock or test objects into your application by changing the bindings.

Testing a SpaceShuttle blastoff

without actually blasting it off is a nice option that an injector allows

easily by simply changing the bindings.

The AngularJS framework also makes heavy use of dependency injection via regular expressions. Besides easing testing, controllers and other pieces of functionality can specify which objects they need to do their work (by function parameter lists) and the correct objects will be injected.

Dependency injection really shines the larger an application grows, and since all nontrivial applications will grow, utilizing dependency injection from the beginning gives your code a great head start.

Comments

Testable JavaScript has a comment block before every function or method that will be unit-tested. How else could you (or anyone else) possibly know what and how to test? While maintaining code, seeing comment blocks before functions (especially public functions) keeps the maintainer informed. You may think that having tests is more important and perhaps replaces the need for correct comments, but I disagree. Writing effective comments and keeping them up to date is an integral part of a developer’s job. Reading code is a more straightforward way to understand it, as opposed to relying on (or reading) the tests for it. While comments for methods are the most important, any comments referencing hard-to-understand code from programmer to programmer are invaluable. It is important that your comments explain both why and how the method exists and what exactly it does. Further, by taking advantage of structured comments, you can easily transform all of your hard work into readable HTML for all to browse.

Comments and tests should not be an either-or proposition. You are a professional programmer, so you can write tests and maintain comment blocks for, at minimum, all public methods. You should only use comments within methods to explain something that is not clear from the surrounding context. If you comment within a function, it is extremely important that you keep those comments up to date! It is far more preferable to have no comments in your code than to have incorrect comments.

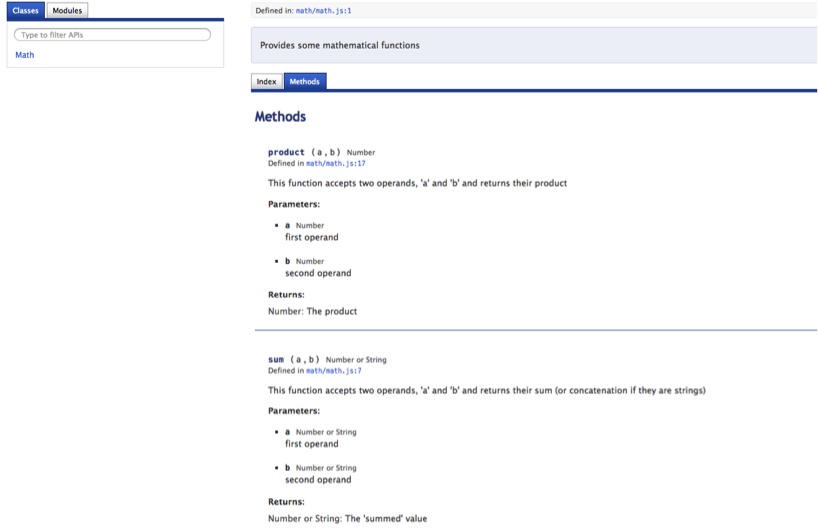

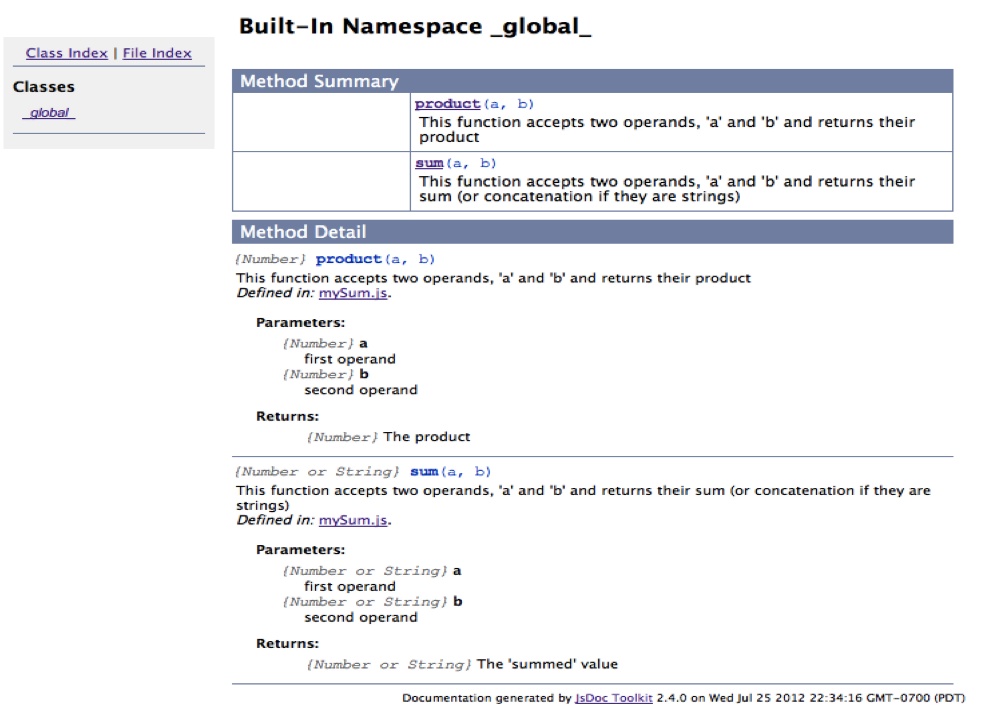

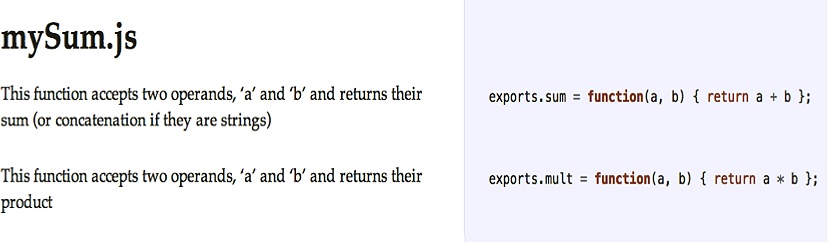

YUIDoc

YUIDoc is a Node.js package available via npm. Installation is easy:

% npm -g install yuidocjsThe yuidoc executable is now

available to transform all of your beloved comments into pretty HTML. In

this section, I will discuss version 0.3.28, the latest version

available at the time of this writing.

YUIDoc comments follow the Javadoc convention of starting with

/** and ending with */. In fact, you can run YUIDoc on any

language whose block comment tokens are /* and */.

YUIDoc provides seven primary tags. Each comment block must contain one and only one of these primary tags; the exhaustive list of tags is available here.

Ideally, you should be able to write unit tests using only the function or method YUIDoc.

Generating YUIDoc from the yuidoc command-line

tool is simple. YUIDoc, however, wants to work with directories, so

unlike with JSDoc (discussed next), you are not able to generate one