16

History and Compatibility

Hurry Slowly (festina lente).

– Octavius, Caesar Augustus

-

Timeline; The Early Years; The ISO C++ Standards; Standards and Programming Style C++ Use

-

C++11 Language Features; C++14 Language Features; C++17 Language Features; C++11 Standard-Library Components; C++14 Standard-Library Components; C++17 Standard-Library Components; Removed and Deprecated Features

16.1 History

I invented C++, wrote its early definitions, and produced its first implementation. I chose and formulated the design criteria for C++, designed its major language features, developed or helped to develop many of the early libraries, and for 25 years was responsible for the processing of extension proposals in the C++ standards committee.

C++ was designed to provide Simula’s facilities for program organization [Dahl,1970] together with C’s efficiency and flexibility for systems programming [Kernighan,1978]. Simula was the initial source of C++’s abstraction mechanisms. The class concept (with derived classes and virtual functions) was borrowed from it. However, templates and exceptions came to C++ later with different sources of inspiration.

The evolution of C++ was always in the context of its use. I spent a lot of time listening to users and seeking out the opinions of experienced programmers. In particular, my colleagues at AT&T Bell Laboratories were essential for the growth of C++ during its first decade.

This section is a brief overview; it does not try to mention every language feature and library component. Furthermore, it does not go into details. For more information, and in particular for more names of people who contributed, see my two papers from the ACM History of Programming Languages conferences [Stroustrup,1993] [Stroustrup,2007] and my Design and Evolution of C++ book (known as “D&E”) [Stroustrup,1994]. They describe the design and evolution of C++ in detail and document influences from other programming languages.

Most of the documents produced as part of the ISO C++ standards effort are available online [WG21]. In my FAQ, I try to maintain a connection between the standard facilities and the people who proposed and refined those facilities [Stroustrup,2010]. C++ is not the work of a faceless, anonymous committee or of a supposedly omnipotent “dictator for life”; it is the work of many dedicated, experienced, hard-working individuals.

16.1.1 Timeline

The work that led to C++ started in the fall of 1979 under the name “C with Classes.” Here is a simplified timeline:

1979 Work on “C with Classes” started. The initial feature set included classes and derived classes, public/private access control, constructors and destructors, and function declarations with argument checking. The first library supported non-preemptive concurrent tasks and random number generators.

1984 “C with Classes” was renamed to C++. By then, C++ had acquired virtual functions, function and operator overloading, references, and the I/O stream and complex number libraries.

1985 First commercial release of C++ (October 14). The library included I/O streams, complex numbers, and tasks (non-preemptive scheduling).

1985 The C++ Programming Language (“TC++PL,” October 14) [Stroustrup,1986].

1989 The Annotated C++ Reference Manual (“the ARM”) [Ellis,1989].

1991 The C++ Programming Language, Second Edition [Stroustrup,1991], presenting generic programming using templates and error handling based on exceptions, including the “Resource Acquisition Is Initialization” (RAII) general resource-management idiom.

1997 The C++ Programming Language, Third Edition [Stroustrup,1997] introduced ISO C++, including namespaces, dynamic_cast, and many refinements of templates. The standard library added the STL framework of generic containers and algorithms.

1998 ISO C++ standard [C++,1998].

2002 Work on a revised standard, colloquially named C++0x, started.

2003 A “bug fix” revision of the ISO C++ standard was issued. A C++ Technical Report introduced new standard-library components, such as regular expressions, unordered containers (hash tables), and resource management pointers, which later became part of C++11.

2006 An ISO C++ Technical Report on Performance addressed questions of cost, predictability, and techniques, mostly related to embedded systems programming [C++,2004].

2011 ISO C++11 standard [C++,2011]. It provided uniform initialization, move semantics, types deduced from initializers (auto), range-for, variadic template arguments, lambda expressions, type aliases, a memory model suitable for concurrency, and much more. The standard library added several components, including threads, locks, and most of the components from the 2003 Technical Report.

2013 The first complete C++11 implementations emerged.

2013 The C++ Programming Language, Fourth Edition introduced C++11.

2014 ISO C++14 standard [C++,2014] completing C++11 with variable templates, digit separators, generic lambdas, and a few standard-library improvements. The first C++14 implementations were completed.

2015 The C++ Core Guidelines projects started [Stroustrup,2015].

2015 The concepts TS was approved.

2017 ISO C++17 standard [C++,2017] offering a diverse set of new features, including order of evaluation guarantees, structured bindings, fold expressions, a file system library, parallel algorithms, and variant and optional types. The first C++17 implementations were completed.

2017 The modules TS and the Ranges TS were approved.

2020 ISO C++20 standard (scheduled).

During development, C++11 was known as C++0x. As is not uncommon in large projects, we were overly optimistic about the completion date. Towards the end, we joked that the ’x’ in C++0x was hexadecimal so that C++0x became C++0B. On the other hand, the committee shipped C++14 and C++17 on time, as did the major compiler providers.

16.1.2 The Early Years

I originally designed and implemented the language because I wanted to distribute the services of a UNIX kernel across multiprocessors and local-area networks (what are now known as multicores and clusters). For that, I needed to precisely specify parts of a system and how they communicated. Simula [Dahl,1970] would have been ideal for that, except for performance considerations. I also needed to deal directly with hardware and provide high-performance concurrent programming mechanisms for which C would have been ideal, except for its weak support for modularity and type checking. The result of adding Simula-style classes to C (Classic C; §16.3.1), “C with Classes,” was used for major projects in which its facilities for writing programs that use minimal time and space were severely tested. It lacked operator overloading, references, virtual functions, templates, exceptions, and many, many details [Stroustrup,1982]. The first use of C++ outside a research organization started in July 1983.

The name C++ (pronounced “see plus plus”) was coined by Rick Mascitti in the summer of 1983 and chosen as the replacement for “C with Classes” by me. The name signifies the evolutionary nature of the changes from C; “++” is the C increment operator. The slightly shorter name “C+” is a syntax error; it had also been used as the name of an unrelated language. Connoisseurs of C semantics find C++ inferior to ++C. The language was not called D, because it was an extension of C, because it did not attempt to remedy problems by removing features, and because there already existed several would-be C successors named D. For yet another interpretation of the name C++, see the appendix of [Orwell,1949].

C++ was designed primarily so that my friends and I would not have to program in assembler, C, or various then-fashionable high-level languages. Its main purpose was to make writing good programs easier and more pleasant for the individual programmer. In the early years, there was no C++ paper design; design, documentation, and implementation went on simultaneously. There was no “C++ project” either, or a “C++ design committee.” Throughout, C++ evolved to cope with problems encountered by users and as a result of discussions among my friends, my colleagues, and me.

The very first design of C++ (then called “C with Classes”) included function declarations with argument type checking and implicit conversions, classes with the public/private distinction between the interface and the implementation, derived classes, and constructors and destructors. I used macros to provide primitive parameterization [Stroustrup,1982]. This was in non-experimental use by mid-1980. Late that year, I was able to present a set of language facilities supporting a coherent set of programming styles. In retrospect, I consider the introduction of constructors and destructors most significant. In the terminology of the time [Stroustrup,1979]:

A “new function” creates the execution environment for the member functions and the “delete function” reverses that.

Soon after, “new function’ and “delete function’ were renamed “constructor” and “destructor.” Here is the root of C++’s strategies for resource management (causing a demand for exceptions) and the key to many techniques for making user code short and clear. If there were other languages at the time that supported multiple constructors capable of executing general code, I didn’t (and don’t) know of them. Destructors were new in C++.

C++ was released commercially in October 1985. By then, I had added inlining (§1.3, §4.2.1), consts (§1.6), function overloading (§1.3), references (§1.7), operator overloading (§4.2.1), and virtual functions (§4.4). Of these features, support for run-time polymorphism in the form of virtual functions was by far the most controversial. I knew its worth from Simula but found it impossible to convince most people in the systems programming world of its value. Systems programmers tended to view indirect function calls with suspicion, and people acquainted with other languages supporting object-oriented programming had a hard time believing that virtual functions could be fast enough to be useful in systems code. Conversely, many programmers with an object-oriented background had (and many still have) a hard time getting used to the idea that you use virtual function calls only to express a choice that must be made at run time. The resistance to virtual functions may be related to a resistance to the idea that you can get better systems through more regular structure of code supported by a programming language. Many C programmers seem convinced that what really matters is complete flexibility and careful individual crafting of every detail of a program. My view was (and is) that we need every bit of help we can get from languages and tools: the inherent complexity of the systems we are trying to build is always at the edge of what we can express.

Early documents (e.g., [Stroustrup,1985] and [Stroustrup,1994]) described C++ like this:

C++ is a general-purpose programming language that

is a better C

supports data abstraction

supports object-oriented programming

Note not “C++ is an object-oriented programming language.” Here, “supports data abstraction” refers to information hiding, classes that are not part of class hierarchies, and generic programming. Initially, generic programming was poorly supported through the use of macros [Stroustrup,1981]. Templates and concepts came much later.

Much of the design of C++ was done on the blackboards of my colleagues. In the early years, the feedback from Stu Feldman, Alexander Fraser, Steve Johnson, Brian Kernighan, Doug McIlroy, and Dennis Ritchie was invaluable.

In the second half of the 1980s, I continued to add language features in response to user comments. The most important of those were templates [Stroustrup,1988] and exception handling [Koenig,1990], which were considered experimental at the time the standards effort started. In the design of templates, I was forced to decide among flexibility, efficiency, and early type checking. At the time, nobody knew how to simultaneously get all three. To compete with C-style code for demanding systems applications, I felt that I had to choose the first two properties. In retrospect, I think the choice was the correct one, and the search for better type checking of templates continues [DosReis,2006] [Gregor,2006] [Sutton,2011] [Stroustrup,2012a]. The design of exceptions focused on multilevel propagation of exceptions, the passing of arbitrary information to an error handler, and the integration between exceptions and resource management by using local objects with destructors to represent and release resources. I clumsily named that critical technique Resource Acquisition Is Initialization and others soon reduced that to the acronym RAII (§4.2.2).

I generalized C++’s inheritance mechanisms to support multiple base classes [Stroustrup,1987a]. This was called multiple inheritance and was considered difficult and controversial. I considered it far less important than templates or exceptions. Multiple inheritance of abstract classes (often called interfaces) is now universal in languages supporting static type checking and object-oriented programming.

The C++ language evolved hand-in-hand with some of the key library facilities. For example, I designed the complex [Stroustrup,1984], vector, stack, and (I/O) stream classes [Stroustrup,1985] together with the operator overloading mechanisms. The first string and list classes were developed by Jonathan Shopiro and me as part of the same effort. Jonathan’s string and list classes were the first to see extensive use as part of a library. The string class from the standard C++ library has its roots in these early efforts. The task library described in [Stroustrup,1987b] was part of the first “C with Classes” program ever written in 1980. It provided coroutines and a scheduler. I wrote it and its associated classes to support Simula-style simulations. Unfortunately, we had to wait until 2011 (30 years!) to get concurrency support standardized and universally available (Chapter 15). Coroutines are likely to be part of C++20 [CoroutinesTS]. The development of the template facility was influenced by a variety of vector, map, list, and sort templates devised by Andrew Koenig, Alex Stepanov, me, and others.

The most important innovation in the 1998 standard library was the STL, a framework of algorithms and containers (Chapter 11, Chapter 12). It was the work of Alex Stepanov (with Dave Musser, Meng Lee, and others) based on more than a decade’s work on generic programming. The STL has been massively influential within the C++ community and beyond.

C++ grew up in an environment with a multitude of established and experimental programming languages (e.g., Ada [Ichbiah,1979], Algol 68 [Woodward,1974], and ML [Paulson,1996]). At the time, I was comfortable in about 25 languages, and their influences on C++ are documented in [Stroustrup,1994] and [Stroustrup,2007]. However, the determining influences always came from the applications I encountered. It was a deliberate policy to have the development of C++ “problem driven” rather than imitative.

16.1.3 The ISO C++ Standards

The explosive growth of C++ use caused some changes. Sometime during 1987, it became clear that formal standardization of C++ was inevitable and that we needed to start preparing the ground for a standardization effort [Stroustrup,1994]. The result was a conscious effort to maintain contact between implementers of C++ compilers and their major users. This was done through paper and electronic mail and through face-to-face meetings at C++ conferences and elsewhere.

AT&T Bell Labs made a major contribution to C++ and its wider community by allowing me to share drafts of revised versions of the C++ reference manual with implementers and users. Because many of those people worked for companies that could be seen as competing with AT&T, the significance of this contribution should not be underestimated. A less enlightened company could have caused major problems of language fragmentation simply by doing nothing. As it happened, about a hundred individuals from dozens of organizations read and commented on what became the generally accepted reference manual and the base document for the ANSI C++ standardization effort. Their names can be found in The Annotated C++ Reference Manual (“the ARM”) [Ellis,1989]. The X3J16 committee of ANSI was convened in December 1989 at the initiative of Hewlett-Packard. In June 1991, this ANSI (American national) standardization of C++ became part of an ISO (international) standardization effort for C++. The ISO C++ committee is called WG21. From 1990, these joint C++ standards committees have been the main forum for the evolution of C++ and the refinement of its definition. I served on these committees throughout. In particular, as the chairman of the working group for extensions (later called the evolution group) from 1990 to 2014, I was directly responsible for handling proposals for major changes to C++ and the addition of new language features. An initial draft standard for public review was produced in April 1995. The first ISO C++ standard (ISO/IEC 14882-1998) [C++,1998] was ratified by a 22-0 national vote in 1998. A “bug fix release” of this standard was issued in 2003, so you sometimes hear people refer to C++03, but that is essentially the same language as C++98.

C++11, known for years as C++0x, is the work of the members of WG21. The committee worked under increasingly onerous self-imposed processes and procedures. These processes probably led to a better (and more rigorous) specification, but they also limited innovation [Stroustrup,2007]. An initial draft standard for public review was produced in 2009. The second ISO C++ standard (ISO/IEC 14882-2011) [C++,2011] was ratified by a 21-0 national vote in August 2011.

One reason for the long gap between the two standards is that most members of the committee (including me) were under the mistaken impression that the ISO rules required a “waiting period” after a standard was issued before starting work on new features. Consequently, serious work on new language features did not start until 2002. Other reasons included the increased size of modern languages and their foundation libraries. In terms of pages of standards text, the language grew by about 30% and the standard library by about 100%. Much of the increase was due to more detailed specification, rather than new functionality. Also, the work on a new C++ standard obviously had to take great care not to compromise older code through incompatible changes. There are billions of lines of C++ code in use that the committee must not break. Stability over decades is an essential “feature.”

C++11 added massively to the standard library and pushed to complete the feature set needed for a programming style that is a synthesis of the “paradigms” and idioms that had proven successful with C++98.

The overall aims for the C++11 effort were:

Make C++ a better language for systems programming and library building.

Make C++ easier to teach and learn.

The aims are documented and detailed in [Stroustrup,2007].

A major effort was made to make concurrent systems programming type-safe and portable. This involved a memory model (§15.1) and support for lock-free programming, This was the work of Hans Boehm, Brian McKnight, and others in the concurrency working group. On top of that, we added the threads library.

After C++11, there was wide agreement that 13 years between standards were far too many. Herb Sutter proposed that the committee adopt a policy of shipping on time at fixed intervals, the “train model.” I argued strongly for a short interval between standards to minimize the chance of delays because someone insisted on extra time to allow inclusion of “just one more essential feature.” We agreed on an ambitious 3-year schedule with the idea that we should alternate between minor and major releases.

C++14 was deliberately a minor release aiming at “completing C++11.” This reflects the reality that with a fixed release date, there will be features that we know we want, but can’t deliver on time. Also, once in widespread use, gaps in the feature set will inevitably be discovered.

To allow work to progress faster, to allow parallel development of independent features, and to better utilize the enthusiasm and skills of the many volunteers, the committee makes use of the ISO mechanisms of developing and publishing “Technical Specifications” (TSs). That seems to work well for standard-library components, though it can lead to more stages in the development process, and thus delays. For language features, TSs seems to work less well. Possibly the reason is that few significant language features are truly independent, because the work of crafting standards wording isn’t all that different between a standard and a TS, and because fewer people can experiment with compiler implementations.

C++17 was meant to be a major release. By “major,” I mean containing features that will change the way we think about design and structure our software. By this definition, C++17 was at best a medium release. It included a lot of minor extensions, but the features that would have made dramatic changes (e.g., concepts, modules, and coroutines) were either not ready or became mired in controversy and lack of design direction. As a result, C++17 includes a little bit for everyone, but nothing that will significantly change the life of a C++ programmer who has already absorbed the lessons of C++11 and C++14. I hope that C++20 will be the promised and much-needed major revision, and that the major new features will become widely available well before 2020. The dangers are “Design by committee,” feature bloat, lack of consistent style, and short-sighted decisions. In a committee with well over 100 members present at each meeting and more participating online, such undesirable phenomena are almost unavoidable. Making progress toward a simpler-to-use and more coherent language is very hard.

16.1.4 Standards and Style

A standard says what will work, and how. It does not say what constitutes good and effective use. There are significant differences between understanding the technical details of programming language features and using them effectively in combination with other features, libraries, and tools to produce better software. By “better” I mean “more maintainable, less error-prone, and faster.” We need to develop, popularize, and support coherent programming styles. Further, we must support the evolution of older code to these more modern, effective, and coherent styles.

With the growth of the language and its standard library, the problem of popularizing effective programming styles became critical. It is extremely difficult to make large groups of programmers depart from something that works for something better. There are still people who see C++ as a few minor additions to C and people who consider 1980s Object-Oriented programming styles based on massive class hierarchies the pinnacle of development. Many are struggling to use C++11 well in environments with lots of old C++ code. On the other hand, there are also many who enthusiastically overuse novel facilities. For example, some programmers are convinced that only code using massive amounts of template metaprogramming is true C++.

What is Modern C++? In 2015, I set out to answer this question by developing a set of coding guidelines supported by articulated rationales. I soon found that I was not alone in grappling with that problem and together with people from many parts of the world, notably from Microsoft, Red Hat, and Facebook, we started the “C++ Core Guidelines” project [Stroustrup,2015]. This is an ambitious project aiming at complete type-safety and complete resource-safety as a base for simpler, faster, and more maintainable code [Stroustrup,2015b]. In addition to specific coding rules with rationales, we back up the guidelines with static analysis tools and a tiny support library. I see something like that as necessary for moving the C++ community at large forward to benefit from the improvements in language features, libraries, and supporting tools.

16.1.5 C++ Use

C++ is now a very widely used programming language. Its user populations grew quickly from one in 1979 to about 400,000 in 1991; that is, the number of users doubled about every 7.5 months for more than a decade. Naturally, the growth rate slowed since that initial growth spurt, but my best estimate is that there are about 4.5 million C++ programmers in 2018 [Kazakova,2015]. Much of that growth happened after 2005 when the exponential explosion of processor speed stopped so that language performance grew in importance. This growth was achieved without formal marketing or an organized user community.

C++ is primarily an industrial language; that is, it is more prominent in industry than in education or programming language research. It grew up in Bell Labs inspired by the varied and stringent needs of telecommunications and of systems programming (including device drivers, networking, and embedded systems). From there, C++ use has spread into essentially every industry: microelectronics, Web applications and infrastructure, operating systems, financial, medical, automobile, aerospace, high-energy physics, biology, energy production, machine learning, video games, graphics, animation, virtual reality, and much more. It is primarily used where problems require C++’s combination of the ability to use hardware effectively and to manage complexity. This seems to be a continuously expanding set of applications [Stroustrup,1993] [Stroustrup,2014].

16.2 C++ Feature Evolution

Here, I list the language features and standard-library components that have been added to C++ for the C++11, C++14, and C++17 standards.

16.2.1 C++11 Language Features

Looking at a list of language features can be quite bewildering. Remember that a language feature is not meant to be used in isolation. In particular, most features that are new in C++11 make no sense in isolation from the framework provided by older features.

[1] Uniform and general initialization using {}-lists (§1.4, §4.2.3)

[2] Type deduction from initializer: auto (§1.4)

[3] Prevention of narrowing (§1.4)

[4] Generalized and guaranteed constant expressions: constexpr (§1.6)

[5] Range-for-statement (§1.7)

[6] Null pointer keyword: nullptr (§1.7)

[7] Scoped and strongly typed enums: enum class (§2.5)

[8] Compile-time assertions: static_assert (§3.5.5)

[9] Language mapping of {}-list to std::initializer_list (§4.2.3)

[10] Rvalue references, enabling move semantics (§5.2.2)

[11] Nested template arguments ending with >> (no space between the >s)

[12] Lambdas (§6.3.2)

[13] Variadic templates (§7.4)

[14] Type and template aliases (§6.4.2)

[15] Unicode characters

[16] long long integer type

[17] Alignment controls: alignas and alignof

[18] The ability to use the type of an expression as a type in a declaration: decltype

[19] Raw string literals (§9.4)

[20] Generalized POD (“Plain Old Data”)

[21] Generalized unions

[22] Local classes as template arguments

[23] Suffix return type syntax

[24] A syntax for attributes and two standard attributes: [[carries_dependency]] and [[noreturn]]

[25] Preventing exception propagation: the noexcept specifier (§3.5.1)

[26] Testing for the possibility of a throw in an expression: the noexcept operator.

[27] C99 features: extended integral types (i.e., rules for optional longer integer types); concatenation of narrow/wide strings; __STDC_HOSTED__; _Pragma(X); vararg macros and empty macro arguments

[28] __func__ as the name of a string holding the name of the current function

[29] inline namespaces

[30] Delegating constructors

[31] In-class member initializers (§5.1.3)

[32] Control of defaults: default and delete (§5.1.1)

[33] Explicit conversion operators

[34] User-defined literals (§5.4.4)

[35] More explicit control of template instantiation: extern templates

[36] Default template arguments for function templates

[37] Inheriting constructors

[38] Override controls: override and final (§4.5.1)

[39] A simpler and more general SFINAE (Substitution Failure Is Not An Error) rule

[40] Memory model (§15.1)

[41] Thread-local storage: thread_local

For a more complete description of the changes to C++98 in C++11, see [Stroustrup,2013].

16.2.2 C++14 Language Features

[1] Function return-type deduction; §3.6.2

[2] Improved constexpr functions, e.g., for-loops allowed (§1.6)

[3] Variable templates (§6.4.1)

[4] Binary literals (§1.4)

[5] Digit separators (§1.4)

[6] Generic lambdas (§6.3.3)

[7] More general lambda capture

[8] [[deprecated]] attribute

[9] A few more minor extensions

16.2.3 C++17 Language Features

[1] Guaranteed copy elision (§5.2.2)

[2] Dynamic allocation of over-aligned types

[3] Stricter order of evaluation (§1.4)

[4] UTF-8 literals (u8)

[5] Hexadecimal floating-point literals

[6] Fold expressions (§7.4.1)

[7] Generic value template arguments (auto template parameters)

[8] Class template argument type deduction (§6.2.3)

[9] Compile-time if (§6.4.3)

[10] Selection statements with initializers (§1.8)

[11] constexpr lambdas

[12] inline variables

[13] Structured bindings (§3.6.3)

[14] New standard attributes: [[fallthrough]], [[nodiscard]], and [[maybe_unused]]

[15] std::byte type

[16] Initialization of an enum by a value of its underlying type (§2.5)

[17] A few more minor extensions

16.2.4 C++11 Standard-Library Components

The C++11 additions to the standard library come in two forms: new components (such as the regular expression matching library) and improvements to C++98 components (such as move constructors for containers).

[1] initializer_list constructors for containers (§4.2.3)

[2] Move semantics for containers (§5.2.2, §11.2)

[3] A singly-linked list: forward_list (§11.6)

[4] Hash containers: unordered_map, unordered_multimap, unordered_set, and unordered_multiset (§11.6, §11.5)

[5] Resource management pointers: unique_ptr, shared_ptr, and weak_ptr (§13.2.1)

[6] Concurrency support: thread (§15.2), mutexes (§15.5), locks (§15.5), and condition variables (§15.6)

[7] Higher-level concurrency support: packaged_thread, future, promise, and async() (§15.7)

[8] tuples (§13.4.3)

[9] Regular expressions: regex (§9.4)

[10] Random numbers: distributions and engines (§14.5)

[11] Integer type names, such as int16_t, uint32_t, and int_fast64_t

[12] A fixed-sized contiguous sequence container: array (§13.4.1)

[13] Copying and rethrowing exceptions (§15.7.1)

[14] Error reporting using error codes: system_error

[15] emplace() operations for containers (§11.6)

[16] Wide use of constexpr functions

[17] Systematic use of noexcept functions

[18] Improved function adaptors: function and bind() (§13.8)

[19] string to numeric value conversions

[20] Scoped allocators

[21] Type traits, such as is_integral and is_base_of (§13.9.2)

[22] Time utilities: duration and time_point (§13.7)

[23] Compile-time rational arithmetic: ratio

[24] Abandoning a process: quick_exit

[25] More algorithms, such as move(), copy_if(), and is_sorted() (Chapter 12)

[26] Garbage collection ABI (§5.3)

[27] Low-level concurrency support: atomics

16.2.5 C++14 Standard-Library Components

[1] shared_mutex (§15.5)

[2] User-defined literals (§5.4.4)

[3] Tuple addressing by type (§13.4.3)

[4] Associative container heterogenous lookup

[5] Plus a few more minor features

16.2.6 C++17 Standard-Library Components

[1] File system (§10.10)

[2] Parallel algorithms (§12.9, §14.3.1)

[3] Mathematical special functions (§14.2)

[4] string_view (§9.3)

[5] any (§13.5.3)

[6] variant (§13.5.1)

[7] optional (§13.5.2)

[8] invoke()

[9] Elementary string conversions: to_chars and from_chars

[10] Polymorphic allocator (§13.6)

[11] A few more minor extensions

16.2.7 Removed and Deprecated Features

There are billions of lines of C++ “out there” and nobody knows exactly what features are in critical use. Consequently, the ISO committee removes older features only reluctantly and after years of warning. However, sometimes troublesome features are removed:

C++17 finally removed exceptions specifications:

void f() throw(X,Y); // C++98; now an error

The support facilities for exception specifications,

unexcepted_handler,set_unexpected(),get_unexpected(), andunexpected(), are similarly removed. Instead, usenoexcept(§3.5.1).Trigraphs are no longer supported.

The

auto_ptris deprecated. Instead, useunique_ptr(§13.2.1).The use of the storage specifier

registeris removed.The use of

++on aboolis removed.The C++98

exportfeature was removed because it was complex and not shipped by the major vendors. Instead,exportis used as a keyword for modules (§3.3).Generation of copy operations is deprecated for a class with a destructor (§5.1.1).

Assignment of a string literal to a

char*is removed. Instead useconst char*orauto.Some C++ standard-library function objects and associated functions are deprecated. Most relate to argument binding. Instead use lambdas and

function(§13.8).

By deprecating a feature, the standards committee expresses the wish that the feature will go away. However, the committee does not have a mandate to immediately remove a heavily used feature – however redundant or dangerous it may be. Thus, a deprecation is a strong hint to avoid the feature. It may disappear in the future. Compilers are likely to issue warnings for uses of deprecated features. However, deprecated features are part of the standard and history shows that they tend to remain supported “forever” for reasons of compatibility.

16.3 C/C++ Compatibility

With minor exceptions, C++ is a superset of C (meaning C11; [C11]). Most differences stem from C++’s greater emphasis on type checking. Well-written C programs tend to be C++ programs as well. A compiler can diagnose every difference between C++ and C. The C99/C++11 incompatibilities are listed in Appendix C of the standard.

16.3.1 C and C++ Are Siblings

Classic C has two main descendants: ISO C and ISO C++. Over the years, these languages have evolved at different paces and in different directions. One result of this is that each language provides support for traditional C-style programming in slightly different ways. The resulting incompatibilities can make life miserable for people who use both C and C++, for people who write in one language using libraries implemented in the other, and for implementers of libraries and tools for C and C++.

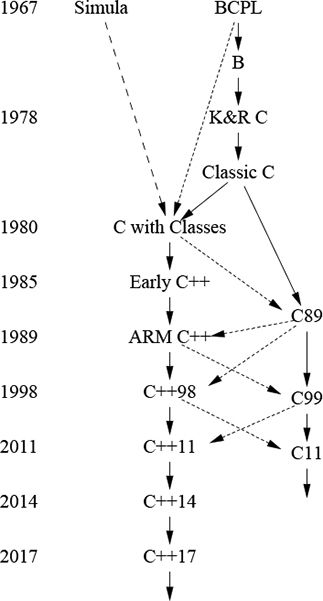

How can I call C and C++ siblings? Look at a simplified family tree:

A solid line means a massive inheritance of features, a dashed line a borrowing of major features, and a dotted line a borrowing of minor features. From this, ISO C and ISO C++ emerge as the two major descendants of K&R C [Kernighan,1978], and as siblings. Each carries with it the key aspects of Classic C, and neither is 100% compatible with Classic C. I picked the term “Classic C” from a sticker that used to be affixed to Dennis Ritchie’s terminal. It is K&R C plus enumerations and struct assignment. BCPL is defined by [Richards,1980] and C89 by [C1990].

Note that differences between C and C++ are not necessarily the result of changes to C made in C++. In several cases, the incompatibilities arise from features adopted incompatibly into C long after they were common in C++. Examples are the ability to assign a T* to a void* and the linkage of global consts [Stroustrup,2002]. Sometimes, a feature was even incompatibly adopted into C after it was part of the ISO C++ standard, such as details of the meaning of inline.

16.3.2 Compatibility Problems

There are many minor incompatibilities between C and C++. All can cause problems for a programmer, but all can be coped with in the context of C++. If nothing else, C code fragments can be compiled as C and linked to using the extern "C" mechanism.

The major problems for converting a C program to C++ are likely to be:

Suboptimal design and programming style.

A

void*implicitly converted to aT*(that is, converted without a cast).C++ keywords, such as

classandprivate, used as identifiers in C code.Incompatible linkage of code fragments compiled as C and fragments compiled as C++.

16.3.2.1 Style Problems

Naturally, a C program is written in a C style, such as the style used in K&R [Kernighan,1988]. This implies widespread use of pointers and arrays, and probably many macros. These facilities are hard to use reliably in a large program. Resource management and error handling are often ad hoc, documented (rather than language and tool supported), and often incompletely documented and adhered to. A simple line-for-line conversion of a C program into a C++ program yields a program that is often a bit better checked. In fact, I have never converted a C program into C++ without finding some bug. However, the fundamental structure is unchanged, and so are the fundamental sources of errors. If you had incomplete error handling, resource leaks, or buffer overflows in the original C program, they will still be there in the C++ version. To obtain major benefits, you must make changes to the fundamental structure of the code:

[1] Don’t think of C++ as C with a few features added. C++ can be used that way, but only suboptimally. To get really major advantages from C++ as compared to C, you need to apply different design and implementation styles.

[2] Use the C++ standard library as a teacher of new techniques and programming styles. Note the difference from the C standard library (e.g., = rather than strcpy() for copying and == rather than strcmp() for comparing).

[3] Macro substitution is almost never necessary in C++. Use const (§1.6), constexpr (§1.6), enum or enum class (§2.5) to define manifest constants, inline (§4.2.1) to avoid function-calling overhead, templates (Chapter 6) to specify families of functions and types, and namespaces (§3.4) to avoid name clashes.

[4] Don’t declare a variable before you need it and initialize it immediately. A declaration can occur anywhere a statement can (§1.8), in for-statement initializers (§1.7), and in conditions (§4.5.2).

[5] Don’t use malloc(). The new operator (§4.2.2) does the same job better, and instead of realloc(), try a vector (§4.2.3, §12.1). Don’t just replace malloc() and free() with “naked” new and delete (§4.2.2).

[6] Avoid void*, unions, and casts, except deep within the implementation of some function or class. Their use limits the support you can get from the type system and can harm performance. In most cases, a cast is an indication of a design error.

[7] If you must use an explicit type conversion, use an appropriate named cast (e.g., static_cast; §16.2.7) for a more precise statement of what you are trying to do.

[8] Minimize the use of arrays and C-style strings. C++ standard-library strings (§9.2), arrays (§13.4.1), and vectors (§11.2) can often be used to write simpler and more maintainable code compared to the traditional C style. In general, try not to build yourself what has already been provided by the standard library.

[9] Avoid pointer arithmetic except in very specialized code (such as a memory manager) and for simple array traversal (e.g., ++p).

[10] Do not assume that something laboriously written in C style (avoiding C++ features such as classes, templates, and exceptions) is more efficient than a shorter alternative (e.g., using standard-library facilities). Often (but of course not always), the opposite is true.

16.3.2.2 void*

In C, a void* may be used as the right-hand operand of an assignment to or initialization of a variable of any pointer type; in C++ it may not. For example:

void f(int n)

{

int* p = malloc(n*sizeof(int)); /* not C++; in C++, allocate using "new" */

// ...

}

This is probably the single most difficult incompatibility to deal with. Note that the implicit conversion of a void* to a different pointer type is not in general harmless:

char ch; void* pv = &ch; int* pi = pv; // not C++ *pi = 666; // overwrite ch and other bytes near ch

In both languages, cast the result of malloc() to the right type. If you use only C++, avoid malloc().

16.3.2.3 Linkage

C and C++ can (and often are) implemented to use different linkage conventions. The most basic reason for that is C++’s greater emphasis on type checking. A practical reason is that C++ supports overloading, so there can be two global functions called open(). This has to be reflected in the way the linker works.

To give a C++ function C linkage (so that it can be called from a C program fragment) or to allow a C function to be called from a C++ program fragment, declare it extern "C". For example:

extern "C" double sqrt(double);

Now sqrt(double) can be called from a C or a C++ code fragment. The definition of sqrt(double) can also be compiled as a C function or as a C++ function.

Only one function of a given name in a scope can have C linkage (because C doesn’t allow function overloading). A linkage specification does not affect type checking, so the C++ rules for function calls and argument checking still apply to a function declared extern "C".

16.4 Bibliography

[Boost] The Boost Libraries: free peer-reviewed portable C++ source libraries. www.boost.org.

[C,1990] X3 Secretariat: Standard – The C Language. X3J11/90-013. ISO Standard ISO/IEC 9899-1990. Computer and Business Equipment Manufacturers Association. Washington, DC.

[C,1999] ISO/IEC 9899. Standard – The C Language. X3J11/90-013-1999.

[C,2011] ISO/IEC 9899. Standard – The C Language. X3J11/90-013-2011.

[C++,1998] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Andrew Koenig): International Standard – The C++ Language. ISO/IEC 14882:1998.

[C++,2004] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Lois Goldtwaite): Technical Report on C++ Performance. ISO/IEC TR 18015:2004(E)

[C++Math,2010] International Standard – Extensions to the C++ Library to Support Mathematical Special Functions. ISO/IEC 29124:2010.

[C++,2011] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Pete Becker): International Standard – The C++ Language. ISO/IEC 14882:2011.

[C++,2014] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Stefanus du Toit): International Standard – The C++ Language. ISO/IEC 14882:2014.

[C++,2017] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Richard Smith): International Standard – The C++ Language. ISO/IEC 14882:2017.

[ConceptsTS] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Gabriel Dos Reis): Technical Specification: C++ Extensions for Concepts. ISO/IEC TS 19217:2015.

[CoroutinesTS] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Gor Nishanov): Technical Specification: C++ Extensions for Coroutines. ISO/IEC TS 22277:2017.

[Cppreference] Online source for C++ language and standard library facilities. www.cppreference.com.

[Cox,2007] Russ Cox: Regular Expression Matching Can Be Simple And Fast. January 2007. swtch.com/~rsc/regexp/regexp1.html.

[Dahl,1970] O-J. Dahl, B. Myrhaug, and K. Nygaard: SIMULA Common Base Language. Norwegian Computing Center S-22. Oslo, Norway. 1970.

[Dechev,2010] D. Dechev, P. Pirkelbauer, and B. Stroustrup: Understanding and Effectively Preventing the ABA Problem in Descriptor-based Lock-free Designs. 13th IEEE Computer Society ISORC 2010 Symposium. May 2010.

[DosReis,2006] Gabriel Dos Reis and Bjarne Stroustrup: Specifying C++ Concepts. POPL06. January 2006.

[Ellis,1989] Margaret A. Ellis and Bjarne Stroustrup: The Annotated C++ Reference Manual. Addison-Wesley. Reading, Massachusetts. 1990. ISBN 0-201-51459-1.

[Garcia,2015] J. Daniel Garcia and B. Stroustrup: Improving performance and maintainability through refactoring in C++11. Isocpp.org. August 2015. http://www.stroustrup.com/improving_garcia_stroustrup_2015.pdf.

[Garcia,2016] G. Dos Reis, J. D. Garcia, J. Lakos, A. Meredith, N. Myers, B. Stroustrup: A Contract Design. P0380R1. 2016-7-11.

[Garcia,2018] G. Dos Reis, J. D. Garcia, J. Lakos, A. Meredith, N. Myers, B. Stroustrup: Support for contract based programming in C++. P0542R4. 2018-4-2.

[Friedl,1997]: Jeffrey E. F. Friedl: Mastering Regular Expressions. O’Reilly Media. Sebastopol, California. 1997. ISBN 978-1565922570.

[GSL] N. MacIntosh (Editor): Guidelines Support Library. https://github.com/microsoft/gsl.

[Gregor,2006] Douglas Gregor et al.: Concepts: Linguistic Support for Generic Programming in C++. OOPSLA’06.

[Hinnant,2018] Howard Hinnant: Date. https://howardhinnant.github.io/date/date.html. Github. 2018.

[Hinnant,2018b] Howard Hinnant: Timezones. https://howardhinnant.github.io/date/tz.html. Github. 2018.

[Ichbiah,1979] Jean D. Ichbiah et al.: Rationale for the Design of the ADA Programming Language. SIGPLAN Notices. Vol. 14, No. 6. June 1979.

[Kazakova,2015] Anastasia Kazakova: Infographic: C/C++ facts. https://blog.jetbrains.com/clion/2015/07/infographics-cpp-facts-before-clion/ July 2015.

[Kernighan,1978] Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie: The C Programming Language. Prentice Hall. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. 1978.

[Kernighan,1988] Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie: The C Programming Language, Second Edition. Prentice-Hall. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. 1988. ISBN 0-13-110362-8.

[Knuth,1968] Donald E. Knuth: The Art of Computer Programming. Addison-Wesley. Reading, Massachusetts. 1968.

[Koenig,1990] A. R. Koenig and B. Stroustrup: Exception Handling for C++ (revised). Proc USENIX C++ Conference. April 1990.

[Maddock,2009] John Maddock: Boost.Regex. www.boost.org. 2009. 2017.

[ModulesTS] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Gabriel Dos Reis): Technical Specification: C++ Extensions for Modules. ISO/IEC TS 21544:2018.

[Orwell,1949] George Orwell: 1984. Secker and Warburg. London. 1949.

[Paulson,1996] Larry C. Paulson: ML for the Working Programmer. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 1996.

[RangesTS] ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 (editor: Eric Niebler): Technical Specification: C++ Extensions for Ranges. ISO/IEC TS 21425:2017. ISBN 0-521-56543-X.

[Richards,1980] Martin Richards and Colin Whitby-Strevens: BCPL – The Language and Its Compiler. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 1980. ISBN 0-521-21965-5.

[Stepanov,1994] Alexander Stepanov and Meng Lee: The Standard Template Library. HP Labs Technical Report HPL-94-34 (R. 1). 1994.

[Stepanov,2009] Alexander Stepanov and Paul McJones: Elements of Programming. Addison-Wesley. 2009. ISBN 978-0-321-63537-2.

[Stroustrup,1979] Personal lab notes.

[Stroustrup,1982] B. Stroustrup: Classes: An Abstract Data Type Facility for the C Language. Sigplan Notices. January 1982. The first public description of “C with Classes.”

[Stroustrup,1984] B. Stroustrup: Operator Overloading in C++. Proc. IFIP WG2.4 Conference on System Implementation Languages: Experience & Assessment. September 1984.

[Stroustrup,1985] B. Stroustrup: An Extensible I/O Facility for C++. Proc. Summer 1985 USENIX Conference.

[Stroustrup,1986] B. Stroustrup: The C++ Programming Language. Addison-Wesley. Reading, Massachusetts. 1986. ISBN 0-201-12078-X.

[Stroustrup,1987] B. Stroustrup: Multiple Inheritance for C++. Proc. EUUG Spring Conference. May 1987.

[Stroustrup,1987b] B. Stroustrup and J. Shopiro: A Set of C Classes for Co-Routine Style Programming. Proc. USENIX C++ Conference. Santa Fe, New Mexico. November 1987.

[Stroustrup,1988] B. Stroustrup: Parameterized Types for C++. Proc. USENIX C++ Conference, Denver, Colorado. 1988.

[Stroustrup,1991] B. Stroustrup: The C++ Programming Language (Second Edition). Addison-Wesley. Reading, Massachusetts. 1991. ISBN 0-201-53992-6.

[Stroustrup,1993] B. Stroustrup: A History of C++: 1979–1991. Proc. ACM History of Programming Languages Conference (HOPL-2). ACM Sigplan Notices. Vol 28, No 3. 1993.

[Stroustrup,1994] B. Stroustrup: The Design and Evolution of C++. Addison-Wesley. Reading, Massachusetts. 1994. ISBN 0-201-54330-3.

[Stroustrup,1997] B. Stroustrup: The C++ Programming Language, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. Reading, Massachusetts. 1997. ISBN 0-201-88954-4. Hardcover (“Special”) Edition. 2000. ISBN 0-201-70073-5.

[Stroustrup,2002] B. Stroustrup: C and C++: Siblings, C and C++: A Case for Compatibility, and C and C++: Case Studies in Compatibility. The C/C++ Users Journal. July-September 2002. www.stroustrup.com/papers.html.

[Stroustrup,2007] B. Stroustrup: Evolving a language in and for the real world: C++ 1991-2006. ACM HOPL-III. June 2007.

[Stroustrup,2009] B. Stroustrup: Programming – Principles and Practice Using C++. Addison-Wesley. 2009. ISBN 0-321-54372-6.

[Stroustrup,2010] B. Stroustrup: The C++11 FAQ. www.stroustrup.com/C++11FAQ.html.

[Stroustrup,2012a] B. Stroustrup and A. Sutton: A Concept Design for the STL. WG21 Technical Report N3351==12-0041. January 2012.

[Stroustrup,2012b] B. Stroustrup: Software Development for Infrastructure. Computer. January 2012. doi:10.1109/MC.2011.353.

[Stroustrup,2013] B. Stroustrup: The C++ Programming Language (Fourth Edition). Addison-Wesley. 2013. ISBN 0-321-56384-0.

[Stroustrup,2014] B. Stroustrup: C++ Applications. http://www.stroustrup.com/applications.html.

[Stroustrup,2015] B. Stroustrup and H. Sutter: C++ Core Guidelines. https://github.com/isocpp/CppCoreGuidelines/blob/master/CppCoreGuidelines.md.

[Stroustrup,2015b] B. Stroustrup, H. Sutter, and G. Dos Reis: A brief introduction to C++’s model for type- and resource-safety. Isocpp.org. October 2015. Revised December 2015. http://www.stroustrup.com/resource-model.pdf.

[Sutton,2011] A. Sutton and B. Stroustrup: Design of Concept Libraries for C++. Proc. SLE 2011 (International Conference on Software Language Engineering). July 2011.

[WG21] ISO SC22/WG21 The C++ Programming Language Standards Committee: Document Archive. www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg21.

[Williams,2012] Anthony Williams: C++ Concurrency in Action – Practical Multithreading. Manning Publications Co. ISBN 978-1933988771.

[Woodward,1974] P. M. Woodward and S. G. Bond: Algol 68-R Users Guide. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. London. 1974.

16.5 Advice

[1] The ISO C++ standard [C++,2017] defines C++.

[2] When chosing a style for a new project or when modernizing a code base, rely on the C++ Core Guidelines; §16.1.4.

[3] When learning C++, don’t focus on language features in isolation; §16.2.1.

[4] Don’t get stuck with decades-old language-feature sets and design techniques; §16.1.4.

[5] Before using a new feature in production code, try it out by writing small programs to test the standards conformance and performance of the implementations you plan to use.

[6] For learning C++, use the most up-to-date and complete implementation of Standard C++ that you can get access to.

[7] The common subset of C and C++ is not the best initial subset of C++ to learn; §16.3.2.1.

[8] Prefer named casts, such as static_cast over C-style casts; §16.2.7.

[9] When converting a C program to C++, first make sure that function declarations (prototypes) and standard headers are used consistently; §16.3.2.

[10] When converting a C program to C++, rename variables that are C++ keywords; §16.3.2.

[11] For portability and type safety, if you must use C, write in the common subset of C and C++; §16.3.2.1.

[12] When converting a C program to C++, cast the result of malloc() to the proper type or change all uses of malloc() to uses of new; §16.3.2.2.

[13] When converting from malloc() and free() to new and delete, consider using vector, push_back(), and reserve() instead of realloc(); §16.3.2.1.

[14] In C++, there are no implicit conversions from ints to enumerations; use explicit type conversion where necessary.

[15] For each standard C header <X.h> that places names in the global namespace, the header <cX> places the names in namespace std.

[16] Use extern "C" when declaring C functions; §16.3.2.3.

[17] Prefer string over C-style strings (direct manipulation of zero-terminated arrays of char).

[18] Prefer iostreams over stdio.

[19] Prefer containers (e.g., vector) over built-in arrays.