13

Utilities

The time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time.

– Bertrand Russell

13.1 Introduction

Not all standard-library components come as part of obviously labeled facilities, such as “containers” or “I/O.” This section gives a few examples of small, widely useful components. Such components (classes and templates) are often called vocabulary types because they are part of the common vocabulary we use to describe our designs and programs. Such library components often act as building blocks for more powerful library facilities, including other components of the standard library. A function or a type need not be complicated or closely tied to a mass of other functions and types to be useful.

13.2 Resource Management

One of the key tasks of any nontrivial program is to manage resources. A resource is something that must be acquired and later (explicitly or implicitly) released. Examples are memory, locks, sockets, thread handles, and file handles. For a long-running program, failing to release a resource in a timely manner (“a leak”) can cause serious performance degradation and possibly even a miserable crash. Even for short programs, a leak can become an embarrassment, say by a resource shortage increasing the run time by orders of magnitude.

The standard library components are designed not to leak resources. To do this, they rely on the basic language support for resource management using constructor/destructor pairs to ensure that a resource doesn’t outlive an object responsible for it. The use of a constructor/destructor pair in Vector to manage the lifetime of its elements is an example (§4.2.2) and all standard-library containers are implemented in similar ways. Importantly, this approach interacts correctly with error handling using exceptions. For example, this technique is used for the standard-library lock classes:

mutex m; // used to protect access to shared data

// ...

void f()

{

scoped_lock<mutex> lck {m}; // acquire the mutex m

// ... manipulate shared data ...

}

A thread will not proceed until lck’s constructor has acquired the mutex (§15.5). The corresponding destructor releases the resources. So, in this example, scoped_lock’s destructor releases the mutex when the thread of control leaves f() (through a return, by “falling off the end of the function,” or through an exception throw).

This is an application of RAII (the “Resource Acquisition Is Initialization” technique; §4.2.2). RAII is fundamental to the idiomatic handling of resources in C++. Containers (such as vector and map, string, and iostream) manage their resources (such as file handles and buffers) similarly.

13.2.1 unique_ptr and shared_ptr

The examples so far take care of objects defined in a scope, releasing the resources they acquire at the exit from the scope, but what about objects allocated on the free store? In <memory>, the standard library provides two “smart pointers” to help manage objects on the free store:

[1] unique_ptr to represent unique ownership

[2] shared_ptr to represent shared ownership

The most basic use of these “smart pointers” is to prevent memory leaks caused by careless programming. For example:

void f(int i, int j) // X* vs. unique_ptr<X>

{

X* p = new X; // allocate a new X

unique_ptr<X> sp {new X}; // allocate a new X and give its pointer to unique_ptr

// ...

if (i<99) throw Z{}; // may throw an exception

if (j<77) return; // may return "early"

// ... use p and sp ..

delete p; // destroy *p

}

Here, we “forgot” to delete p if i<99 or if j<77. On the other hand, unique_ptr ensures that its object is properly destroyed whichever way we exit f() (by throwing an exception, by executing return, or by “falling off the end”). Ironically, we could have solved the problem simply by not using a pointer and not using new:

void f(int i, int j) // use a local variable

{

Xx;

// ...

}

Unfortunately, overuse of new (and of pointers and references) seems to be an increasing problem.

However, when you really need the semantics of pointers, unique_ptr is a very lightweight mechanism with no space or time overhead compared to correct use of a built-in pointer. Its further uses include passing free-store allocated objects in and out of functions:

unique_ptr<X> make_X(int i)

// make an X and immediately give it to a unique_ptr

{

// ... check i, etc. ...

return unique_ptr<X>{new X{i}};

}

A unique_ptr is a handle to an individual object (or an array) in much the same way that a vector is a handle to a sequence of objects. Both control the lifetime of other objects (using RAII) and both rely on move semantics to make return simple and efficient.

The shared_ptr is similar to unique_ptr except that shared_ptrs are copied rather than moved. The shared_ptrs for an object share ownership of an object; that object is destroyed when the last of its shared_ptrs is destroyed. For example:

void f(shared_ptr<fstream>);

void g(shared_ptr<fstream>);

void user(const string& name, ios_base::openmode mode)

{

shared_ptr<fstream> fp {new fstream(name,mode)};

if (!*fp) // make sure the file was properly opened

throw No_file{};

f(fp);

g(fp);

// ...

}

Now, the file opened by fp’s constructor will be closed by the last function to (explicitly or implicitly) destroy a copy of fp. Note that f() or g() may spawn a task holding a copy of fp or in some other way store a copy that outlives user(). Thus, shared_ptr provides a form of garbage collection that respects the destructor-based resource management of the memory-managed objects. This is neither cost free nor exorbitantly expensive, but it does make the lifetime of the shared object hard to predict. Use shared_ptr only if you actually need shared ownership.

Creating an object on the free store and then passing the pointer to it to a smart pointer is a bit verbose. It also allows for mistakes, such as forgetting to pass a pointer to a unique_ptr or giving a pointer to something that is not on the free store to a shared_ptr. To avoid such problems, the standard library (in <memory>) provides functions for constructing an object and returning an appropriate smart pointer, make_shared() and make_unique(). For example:

struct S {

int i;

string s;

double d;

// ...

};

auto p1 = make_shared<S>(1,"Ankh Morpork",4.65); // p1 is a shared_ptr<S>

auto p2 = make_unique<S>(2,"Oz",7.62); // p2 is a unique_ptr<S>

Now, p2 is a unique_ptr<S> pointing to a free-store-allocated object of type S with the value {2,"Oz"s,7.62}.

Using make_shared() is not just more convenient than separately making an object using new and then passing it to a shared_ptr, it is also notably more efficient because it does not need a separate allocation for the use count that is essential in the implementation of a shared_ptr.

Given unique_ptr and shared_ptr, we can implement a complete “no naked new” policy (§4.2.2) for many programs. However, these “smart pointers” are still conceptually pointers and therefore only my second choice for resource management – after containers and other types that manage their resources at a higher conceptual level. In particular, shared_ptrs do not in themselves provide any rules for which of their owners can read and/or write the shared object. Data races (§15.7) and other forms of confusion are not addressed simply by eliminating the resource management issues.

Where do we use “smart pointers” (such as unique_ptr) rather than resource handles with operations designed specifically for the resource (such as vector or thread)? Unsurprisingly, the answer is “when we need pointer semantics.”

When we share an object, we need pointers (or references) to refer to the shared object, so a

shared_ptrbecomes the obvious choice (unless there is an obvious single owner).When we refer to a polymorphic object in classical object-oriented code (§4.5), we need a pointer (or a reference) because we don’t know the exact type of the object referred to (or even its size), so a

unique_ptrbecomes the obvious choice.A shared polymorphic object typically requires

shared_ptrs.

We do not need to use a pointer to return a collection of objects from a function; a container that is a resource handle will do that simply and efficiently (§5.2.2).

13.2.2 move() and forward()

The choice between moving and copying is mostly implicit (§3.6). A compiler will prefer to move when an object is about to be destroyed (as in a return) because that’s assumed to be the simpler and more efficient operation. However, sometimes we must be explicit. For example, a unique_ptr is the sole owner of an object. Consequently, it cannot be copied:

void f1()

{

auto p = make_unique<int>(2);

auto q = p; // error: we can't copy a unique_ptr

// ...

}

If you want a unique_ptr elsewhere, you must move it. For example:

void f1()

{

auto p = make_unique<int>(2);

auto q = move(p); // p now holds nullptr

// ...

}

Confusingly, std::move() doesn’t move anything. Instead, it casts its argument to an rvalue reference, thereby saying that its argument will not be used again and therefore may be moved (§5.2.2). It should have been called something like rvalue_cast. Like other casts, it’s error-prone and best avoided. It exists to serve a few essential cases. Consider a simple swap:

template <typename T>

void swap(T& a, T& b)

{

T tmp {move(a)}; // the T constructor sees an rvalue and moves

a = move(b); // the T assignment sees an rvalue and moves

b = move(tmp); // the T assignment sees an rvalue and moves

}

We don’t want to repeatedly copy potentially large objects, so we request moves using std::move().

Like for other casts, there are tempting, but dangerous, uses of std::move(). Consider:

string s1 = "Hello"; string s2 = "World"; vector<string> v; v.push_back(s1); // use a "const string&" argument; push_back() will copy v.push_back(move(s2)); // use a move constructor

Here s1 is copied (by push_back()) whereas s2 is moved. This sometimes (only sometimes) makes the push_back() of s2 cheaper. The problem is that a moved-from object is left behind. If we use s2 again, we have a problem:

cout << s1[2]; // write 'l' cout << s2[2]; // crash?

I consider this use of std::move() to be too error-prone for widespread use. Don’t use it unless you can demonstrate significant and necessary performance improvement. Later maintenance may accidentally lead to unanticipated use of the moved-from object.

The state of a moved-from object is in general unspecified, but all standard-library types leave a moved-from object in a state where it can be destroyed and assigned to. It would be unwise not to follow that lead. For a container (e.g., vector or string), the moved-from state will be “empty.” For many types, the default value is a good empty state: meaningful and cheap to establish.

Forwarding arguments is an important use case that requires moves (§7.4.2). We sometimes want to transmit a set of arguments on to another function without changing anything (to achieve “perfect forwarding”):

template<typename T, typename ... Args>

unique_ptr<T> make_unique(Args&&... args)

{

return unique_ptr<T>{new T{std::forward<Args>(args)...}}; // forward each argument

}

The standard-library forward() differs from the simpler std::move() by correctly handling subtleties to do with lvalue and rvalue (§5.2.2). Use std::forward() exclusively for forwarding and don’t forward() something twice; once you have forwarded an object, it’s not yours to use anymore.

13.3 Range Checking: gsl::span

Traditionally, range errors have been a major source of serious errors in C and C++ programs. The use of containers (Chapter 11), algorithms (Chapter 12), and range-for has significantly reduced this problem, but more can be done. A key source of range errors is that people pass pointers (raw or smart) and then rely on convention to know the number of elements pointed to. The best advice for code outside resource handles is to assume that at most one object is pointed to [CG: F.22], but without support that advice is unmanageable. The standard-library string_view (§9.3) can help, but that is read-only and for characters only. Most programmers need more.

The Core Guidelines [Stroustrup,2015] offer guidelines and a small Guidelines Support Library [GSL], including a span type for referring to a range of elements. This span is being proposed for the standard, but for now it is just something you can download if needed.

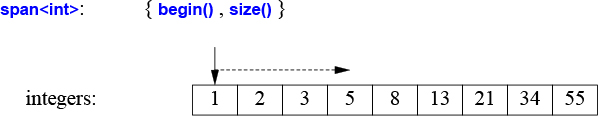

A string_span is basically a (pointer,length) pair denoting a sequence of elements:

A span gives access to a contiguous sequence of elements. The elements can be stored in many ways, including in vectors and built-in arrays. Like a pointer, a span does not own the characters it points to. In that, it resembles a string_view (§9.3) and an STL pair of iterators (§12.3).

Consider a common interface style:

void fpn(int* p, int n)

{

for (int i = 0; i<n; ++i)

p[i] = 0;

}

We assume that p points to n integers. Unfortunately, this assumption is simply a convention, so we can’t use it to write a range-for loop and the compiler cannot implement cheap and effective range checking. Also, our assumption can be wrong:

void use(int x)

{

int a[100];

fpn(a,100); // OK

fpn(a,1000); // oops, my finger slipped! (range error in fpn)

fpn(a+10,100); // range error in fpn

fpn(a,x); // suspect, but looks innocent

}

We can do better using a span:

void fs(span<int> p)

{

for (int x : p)

x = 0;

}

We can use fs like this:

void use(int x)

{

int a[100];

fs(a); // implicitly creates a span<int>{a,100}

fs(a,1000); // error: span expected

fs({a+10,100}); // a range error in fs

fs({a,x}); // obviously suspect

}

That is, the common case, creating a span directly from an array, is now safe (the compiler computes the element count) and notationally simple. For other cases, the probability of mistakes is lowered because the programmer has to explicitly compose a span.

The common case where a span is passed along from function to function is simpler than for (pointer,count) interfaces and obviously doesn’t require extra checking:

void f1(span<int> p);

void f2(span<int> p)

{

// ...

f1(p);

}

When used for subscripting (e.g., r[i]), range checking is done and a gsl::fail_fast is thrown in case of a range error. Range checks can be suppressed for performance critical code. When span makes it into the standard, I expect that std::span will use contracts [Garcia,2017] to control responses to range violation.

Note that just a single range check is needed for the loop. Thus, for the common case where the body of a function using a span is a loop over the span, range checking is almost free.

A span of characters is supported directly and called gsl::string_span.

13.4 Specialized Containers

The standard library provides several containers that don’t fit perfectly into the STL framework (Chapter 11, Chapter 12). Examples are built-in arrays, array, and string. I sometimes refer to those as “almost containers,” but that is not quite fair: they hold elements, so they are containers, but each has restrictions or added facilities that make them awkward in the context of the STL. Describing them separately also simplifies the description of the STL.

“Almost Containers” |

|

|

Built-in array: a fixed-size contiguously allocated sequence of |

|

A fixed-size contiguously allocated sequence of |

|

A fixed-size sequence of |

|

A sequence of bits compactly stored in a specialization of |

|

Two elements of types |

|

A sequence of an arbitrary number of elements of arbitrary types |

|

A sequence of characters of type |

|

An array of numeric values of type |

Why does the standard library provide so many containers? They serve common but different (often overlapping) needs. If the standard library didn’t provide them, many people would have to design and implement their own. For example:

pairandtupleare heterogeneous; all other containers are homogeneous (all elements are of the same type).array,vector, andtupleelements are contiguously allocated;forward_listandmapare linked structures.bitsetandvector<bool>hold bits and access them through proxy objects; all other standard-library containers can hold a variety of types and access elements directly.basic_stringrequires its elements to be some form of character and to provide string manipulation, such as concatenation and locale-sensitive operations.valarrayrequires its elements to be numbers and to provide numerical operations.

All of these containers can be seen as providing specialized services needed by large communities of programmers. No single container could serve all of these needs because some needs are contradictory, for example, “ability to grow” vs. “guaranteed to be allocated in a fixed location,” and “elements do not move when elements are added” vs. “contiguously allocated.”

13.4.1 array

An array, defined in <array>, is a fixed-size sequence of elements of a given type where the number of elements is specified at compile time. Thus, an array can be allocated with its elements on the stack, in an object, or in static storage. The elements are allocated in the scope where the array is defined. An array is best understood as a built-in array with its size firmly attached, without implicit, potentially surprising conversions to pointer types, and with a few convenience functions provided. There is no overhead (time or space) involved in using an array compared to using a built-in array. An array does not follow the “handle to elements” model of STL containers. Instead, an array directly contains its elements.

An array can be initialized by an initializer list:

array<int,3> a1 = {1,2,3};

The number of elements in the initializer must be equal to or less than the number of elements specified for the array.

The element count is not optional:

array<int> ax = {1,2,3}; // error size not specified

The element count must be a constant expression:

void f(int n)

{

array<string,n> aa = {"John's", "Queens' "}; // error: size not a constant expression

//

}

If you need the element count to be a variable, use vector.

When necessary, an array can be explicitly passed to a C-style function that expects a pointer. For example:

void f(int* p, int sz); // C-style interface

void g()

{

array<int,10> a;

f(a,a.size()); // error: no conversion

f(&a[0],a.size()); // C-style use

f(a.data(),a.size()); // C-style use

auto p = find(a.begin(),a.end(),777); // C++/STL-style use

// ...

}

Why would we use an array when vector is so much more flexible? An array is less flexible so it is simpler. Occasionally, there is a significant performance advantage to be had by directly accessing elements allocated on the stack rather than allocating elements on the free store, accessing them indirectly through the vector (a handle), and then deallocating them. On the other hand, the stack is a limited resource (especially on some embedded systems), and stack overflow is nasty.

Why would we use an array when we could use a built-in array? An array knows its size, so it is easy to use with standard-library algorithms, and it can be copied using =. However, my main reason to prefer array is that it saves me from surprising and nasty conversions to pointers. Consider:

void h()

{

Circle a1[10];

array<Circle,10> a2;

// ...

Shape* p1 = a1; // OK: disaster waiting to happen

Shape* p2 = a2; // error: no conversion of array<Circle,10> to Shape*

p1[3].draw(); // disaster

}

The “disaster” comment assumes that sizeof(Shape)<sizeof(Circle), so subscripting a Circle[] through a Shape* gives a wrong offset. All standard containers provide this advantage over built-in arrays.

13.4.2 bitset

Aspects of a system, such as the state of an input stream, are often represented as a set of flags indicating binary conditions such as good/bad, true/false, and on/off. C++ supports the notion of small sets of flags efficiently through bitwise operations on integers (§1.4). Class bitset<N> generalizes this notion by providing operations on a sequence of N bits [0:N), where N is known at compile time. For sets of bits that don’t fit into a long long int, using a bitset is much more convenient than using integers directly. For smaller sets, bitset is usually optimized. If you want to name the bits, rather than numbering them, you can use a set (§11.4) or an enumeration (§2.5).

A bitset can be initialized with an integer or a string:

bitset<9> bs1 {"110001111"};

bitset<9> bs2 {0b1'1000'1111}; // binary literal using digit separators (§1.4)

The usual bitwise operators (§1.4) and the left- and right-shift operators (<< and >>) can be applied:

bitset<9> bs3 = ~bs1; // complement: bs3=="001110000" bitset<9> bs4 = bs1&bs3; // all zeros bitset<9> bs5 = bs1<<2; // shift left: bs5 = "000111100"

The shift operators (here, <<) “shift in” zeros.

The operations to_ullong() and to_string() provide the inverse operations to the constructors. For example, we could write out the binary representation of an int:

void binary(int i)

{

bitset<8*sizeof(int)>b = i; // assume 8-bit byte (see also §14.7)

cout << b.to_string() << '\n'; // write out the bits of i

}

This prints the bits represented as 1s and 0s from left to right, with the most significant bit leftmost, so that argument 123 would give the output

00000000000000000000000001111011

For this example, it is simpler to directly use the bitset output operator:

void binary2(int i)

{

bitset<8*sizeof(int)>b = i; // assume 8-bit byte (see also §14.7)

cout << b << '\n'; // write out the bits of i

}

13.4.3 pair and tuple

Often, we need some data that is just data; that is, a collection of values, rather than an object of a class with well-defined semantics and an invariant for its value (§3.5.2). In such cases, a simple struct with an appropriate set of appropriately named members is often ideal. Alternatively, we could let the standard library write the definition for us. For example, the standard-library algorithm equal_range returns a pair of iterators specifying a subsequence meeting a predicate:

template<typename Forward_iterator, typename T, typename Compare>

pair<Forward_iterator,Forward_iterator>

equal_range(Forward_iterator first, Forward_iterator last, const T& val, Compare cmp);

Given a sorted sequence [first:last), equal_range() will return the pair representing the subsequence that matches the predicate cmp. We can use that to search in a sorted sequence of Records:

auto less = [](const Record& r1, const Record& r2) { return r1.name<r2.name;}; // compare names

void f(const vector<Record>& v) // assume that v is sorted on its "name" field

{

auto er = equal_range(v.begin(),v.end(),Record{"Reg"},less);

for (auto p = er.first; p!=er.second; ++p) // print all equal records

cout << *p; // assume that << is defined for Record

}

The first member of a pair is called first and the second member is called second. This naming is not particularly creative and may look a bit odd at first, but such consistent naming is a boon when we want to write generic code. Where the names first and last are too generic, we can use structured binding (§3.6.3):

void f2(const vector<Record>& v) // assume that v is sorted on its "name" field

{

auto [first,last] = equal_range(v.begin(),v.end(),Record{"Reg"},less);

for (auto p = first; p!=last; ++p) // print all equal records

cout << *p; // assume that << is defined for Record

}

The standard-library pair (from <utility>) is quite frequently used in the standard library and elsewhere. A pair provides operators, such as =, ==, and <, if its elements do. Type deduction makes it easy to create a pair without explicitly mentioning its type. For example:

void f(vector<string>& v)

{

pair p1 {v.begin(),2}; // one way

auto p2 = make_pair(v.begin(),2); // another way

// ...

}

Both p1 and p2 are of type pair<vector<string>::iterator,int>.

If you need more than two elements (or less), you can use tuple (from <utility>). A tuple is a heterogeneous sequence of elements; for example:

tuple<string,int,double> t1 {"Shark",123,3.14}; // the type is explicitly specified

auto t2 = make_tuple(string{"Herring"},10,1.23); // the type is deduced to tuple<string,int,double>

tuple t3 {"Cod"s,20,9.99}; // the type is deduced to tuple<string,int,double>

Older code tends to use make_tuple() because template argument type deduction from constructor arguments is C++17.

Access to tuple members is through a get function template:

string s = get<0>(t1); // get the first element: "Shark" int x = get<1>(t1); // get the second element: 123 double d = get<2>(t1); // get the third element: 3.14

The elements of a tuple are numbered (starting with zero) and the indices must be constants.

Accessing members of a tuple by their index is general, ugly, and somewhat error-prone. Fortunately, an element of a tuple with a unique type in that tuple can be “named” by its type:

auto s = get<string>(t1); // get the string: "Shark" auto x = get<int>(t1); // get the int: 123 auto d = get<double>(t1); // get the double: 3.14

We can use get<> for writing also:

get<string>(t1) = "Tuna"; // write to the string get<int>(t1) = 7; // write to the int get<double>(t1) = 312; // write to the double

Like pairs, tuples can be assigned and compared if their elements can be. Like tuple elements, pair elements can be accessed using get<>().

Like for pair, structured binding (§3.6.3) can be used for tuple. However, when code doesn’t need to be generic, a simple struct with named members often leads to more maintainable code.

13.5 Alternatives

The standard library offers three types to express alternatives:

variantto represent one of a specified set of alternatives (in<variant>)optionalto represent a value of a specified type or no value (in<optional>)anyto represent one of an unbounded set of alternative types (in<any>)

These three types offer related functionality to the user. Unfortunately, they don’t offer a unified interface.

13.5.1 variant

A variant<A,B,C> is often a safer and more convenient alternative to explicitly using a union (§2.4). Possibly the simplest example is to return either a value or an error code:

variant<string,int> compose_message(istream& s)

{

string mess;

// ... read from s and compose message ...

if (no_problems)

return mess; // return a string

else

return error_number; // return an int

}

When you assign or initialize a variant with a value, it remembers the type of that value. Later, we can inquire what type the variant holds and extract the value. For example:

auto m = compose_message(cin));

if (holds_alternative<string>(m)) {

cout << m.get<string>();

}

else {

int err = m.get<int>();

// ... handle error ...

}

This style appeals to some people who dislike exceptions (see §3.5.3), but there are more interesting uses. For example, a simple compiler may need to distinguish between different kind of nodes with different representations:

using Node = variant<Expression,Statement,Declaration,Type>;

void check(Node* p)

{

if (holds_alternative<Expression>(*p)) {

Expression& e = get<Expression>(*p);

// ...

}

else if (holds_alternative<Statement>(*p)) {

Statement& s = get<Statement>(*p);

// ...

}

// ... Declaration and Type ...

}

This pattern of checking alternatives to decide on the appropriate action is so common and relatively inefficient that it deserves direct support:

void check(Node* p)

{

visit(overloaded {

[](Expression& e) { /* ... */ },

[](Statement& s) { /* ... */ },

// ... Declaration and Type ...

}, *p);

}

This is basically equivalent to a virtual function call, but potentially faster. As with all claims of performance, this “potentially faster” should be verified by measurements when performance is critical. For most uses, the difference in performance is insignificant.

Unfortunately, the overloaded is necessary and not standard. It’s a “piece of magic” that builds an overload set from a set of arguments (usually lambdas):

template<class... Ts>

struct overloaded : Ts... {

using Ts::operator()...;

};

template<class... Ts>

overloaded(Ts...) −> overloaded<Ts...>; // deduction guide

The “visitor” visit then applies () to the overload, which selects the most appropriate lambda to call according to the overload rules.

A deduction guide is a mechanism for resolving subtle ambiguities, primarily for constructors of class templates in foundation libraries. (§6.2.3)

If we try to access a variant holding a different type than the expected one, bad_variant_access is thrown.

13.5.2 optional

An optional<A> can be seen as a special kind of variant (like a variant<A,nothing>) or as a generalization of the idea of an A* either pointing to an object or being nullptr.

An optional can be useful for functions that may or may not return an object:

optional<string> compose_message(istream& s)

{

string mess;

// ... read from s and compose message ...

if (no_problems)

return mess;

return {}; // the empty optional

}

Given that, we can write

if (auto m = compose_message(cin))

cout << *m; // note the dereference (*)

else {

// ... handle error ...

}

This appeals to some people who dislike exceptions (see §3.5.3). Note the curious use of *. An optional is treated as a pointer to its object rather than the object itself.

The optional equivalent to nullptr is the empty object, {}. For example:

int cat(optional<int> a, optional<int> b)

{

int res = 0;

if (a) res+=*a;

if (b) res+=*b;

return res;

}

int x = cat(17,19);

int y = cat(17,{});

int z = cat({},{});

If we try to access an optional that does not hold a value, the result is undefined; an exception is not thrown. Thus, optional is not guaranteed type safe.

13.5.3 any

An any can hold an arbitrary type and know which type (if any) it holds. It is basically an unconstrained version of variant:

any compose_message(istream& s)

{

string mess;

// ... read from s and compose message ...

if (no_problems)

return mess; // return a string

else

return error_number; // return an int

}

When you assign or initialize an any with a value, it remembers the type of that value. Later, we can inquire what type the any holds and extract the value. For example:

auto m = compose_message(cin)); string& s = any_cast<string>(m); cout << s;

If we try to access an any holding a different type than the expected one, bad_any_access is thrown. There are also ways of accessing an any that do not rely on exceptions.

13.6 Allocators

By default, standard-library containers allocate space using new. Operators new and delete provide a general free store (also called dynamic memory or heap) that can hold objects of arbitrary size and user-controlled lifetime. This implies time and space overheads that can be eliminated in many special cases. Therefore, the standard-library containers offer the opportunity to install allocators with specific semantics where needed. This has been used to address a wide variety of concerns related to performance (e.g., pool allocators), security (allocators that clean-up memory as part of deletion), per-thread allocation, and non-uniform memory architectures (allocating in specific memories with pointer types to match). This is not the place to discuss these important, but very specialized and often advanced techniques. However, I will give one example motivated by a real-world problem for which a pool allocator was the solution.

An important, long-running system used an event queue (see §15.6) using vectors as events that were passed as shared_ptrs. That way, the last user of an event implicitly deleted it:

struct Event {

vector<int> data = vector<int>(512);

};

list<shared_ptr<Event>> q;

void producer()

{

for (int n = 0; n!=LOTS; ++n) {

lock_guard lk {m}; // m is a mutex (§15.5)

q.push_back(make_shared<Event>());

cv.notify_one();

}

}

From a logical point of view this worked nicely. It is logically simple, so the code is robust and maintainable. Unfortunately, this led to massive fragmentation. After 100,000 events had been passed among 16 producers and 4 consumers, more than 6GB memory had been consumed.

The traditional solution to fragmentation problems is to rewrite the code to use a pool allocator. A pool allocator is an allocator that manages objects of a single fixed size and allocates space for many objects at a time, rather than using individual allocations. Fortunately, C++17 offers direct support for that. The pool allocator is defined in the pmr (“polymorphic memory resource”) sub-namespace of std:

pmr::synchronized_pool_resource pool; // make a pool

struct Event {

vector<int> data = vector<int>{512,&pool}; // let Events use the pool

};

list<shared_ptr<Event>> q {&pool}; // let q use the pool

void producer()

{

for (int n = 0; n!=LOTS; ++n) {

scoped_lock lk {m}; // m is a mutex (§15.5)

q.push_back(allocate_shared<Event,pmr::polymorphic_allocator<Event>>{&pool});

cv.notify_one();

}

}

Now, after 100,000 events had been passed among 16 producers and 4 consumers, less than 3MB memory had been consumed. That’s about a 2000-fold improvement! Naturally, the amount of memory actually in use (as opposed to memory wasted to fragmentation) is unchanged. After eliminating fragmentation, memory use was stable over time so the system could run for months.

Techniques like this have been applied with good effects from the earliest days of C++, but generally they required code to be rewritten to use specialized containers. Now, the standard containers optionally take allocator arguments. The default is for the containers to use new and delete.

13.7 Time

In <chrono>, the standard library provides facilities for dealing with time. For example, here is the basic way of timing something:

using namespace std::chrono; // in sub-namespace std::chrono; see §3.4 auto t0 = high_resolution_clock::now(); do_work(); auto t1 = high_resolution_clock::now(); cout << duration_cast<milliseconds>(t1−t0).count() << "msec\n";

The clock returns a time_point (a point in time). Subtracting two time_points gives a duration (a period of time). Various clocks give their results in various units of time (the clock I used measures nanoseconds), so it is usually a good idea to convert a duration into a known unit. That’s what duration_cast does.

Don’t make statements about “efficiency” of code without first doing time measurements. Guesses about performance are most unreliable.

To simplify notation and minimize errors, <chrono> offers time-unit suffixes (§5.4.4). For example:

this_thread::sleep(10ms+33us); // wait for 10 milliseconds and 33 microseconds

The chrono suffixes are defined in namespace std::chrono_literals.

An elegant and efficient extension to <chrono>, supporting longer time intervals (e.g., years and months), calendars, and time zones, is being added to the standard for C++20. It is currently available and in wide production use [Hinnant,2018] [Hinnant,2018b]. You can say things like

auto spring_day = apr/7/2018; cout << weekday(spring_day) << '\n'; // Saturday

It even handles leap seconds.

13.8 Function Adaption

When passing a function as a function argument, the type of the argument must exactly match the expectations expressed in the called function’s declaration. If the intended argument “almost matches expectations,” we have three good alternatives:

Use a lambda (§13.8.1).

Use

std::mem_fn()to make a function object from a member function (§13.8.2).Define the function to accept a

std::function(§13.8.3).

There are many other ways, but usually one of these three ways works best.

13.8.1 Lambdas as Adaptors

Consider the classical “draw all shapes” example:

void draw_all(vector<Shape*>& v)

{

for_each(v.begin(),v.end(),[](Shape* p) { p−>draw(); });

}

Like all standard-library algorithms, for_each() calls its argument using the traditional function call syntax f(x), but Shape's draw() uses the conventional OO notation x−>f(). A lambda easily mediates between the two notations.

13.8.2 mem_fn()

Given a member function, the function adaptor mem_fn(mf) produces a function object that can be called as a nonmember function. For example:

void draw_all(vector<Shape*>& v)

{

for_each(v.begin(),v.end(),mem_fn(&Shape::draw));

}

Before the introduction of lambdas in C++11, mem_fn() and equivalents were the main way to map from the object-oriented calling style to the functional one.

13.8.3 function

The standard-library function is a type that can hold any object you can invoke using the call operator (). That is, an object of type function is a function object (§6.3.2). For example:

int f1(double);

function<int(double)> fct1 {f1}; // initialize to f1

int f2(string);

function fct2 {f2}; // fct2's type is function<int(string)>

function fct3 = [](Shape* p) { p−>draw(); }; // fct3's type is function<void(Shape*)>

For fct2, I let the type of the function be deduced from the initializer: int(string).

Obviously, functions are useful for callbacks, for passing operations as arguments, for passing function objects, etc. However, it may introduce some run-time overhead compared to direct calls, and a function, being an object, does not participate in overloading. If you need to overload function objects (including lambdas), consider overloaded (§13.5.1).

13.9 Type Functions

A type function is a function that is evaluated at compile time given a type as its argument or returning a type. The standard library provides a variety of type functions to help library implementers (and programmers in general) to write code that takes advantage of aspects of the language, the standard library, and code in general.

For numerical types, numeric_limits from <limits> presents a variety of useful information (§14.7). For example:

constexpr float min = numeric_limits<float>::min(); // smallest positive float

Similarly, object sizes can be found by the built-in sizeof operator (§1.4). For example:

constexprint szi = sizeof(int); // the number of bytes in an int

Such type functions are part of C++’s mechanisms for compile-time computation that allow tighter type checking and better performance than would otherwise have been possible. Use of such features is often called metaprogramming or (when templates are involved) template metaprogramming. Here, I just present the use of two facilities provided by the standard library: iterator_traits (§13.9.1) and type predicates (§13.9.2). Concepts (§7.2) make some of these techniques redundant and simplify many of the rest, but concepts are still not standard or universally available, so the techniques presented here are in wide use.

13.9.1 iterator_traits

The standard-library sort() takes a pair of iterators supposed to define a sequence (Chapter 12). Furthermore, those iterators must offer random access to that sequence, that is, they must be random-access iterators. Some containers, such as forward_list, do not offer that. In particular, a forward_list is a singly-linked list so subscripting would be expensive and there is no reasonable way to refer back to a previous element. However, like most containers, forward_list offers forward iterators that can be used to traverse the sequence by algorithms and for-statements (§6.2).

The standard library provides a mechanism, iterator_traits, that allows us to check which kind of iterator is provided. Given that, we can improve the range sort() from §12.8 to accept either a vector or a forward_list. For example:

void test(vector<string>& v, forward_list<int>& lst)

{

sort(v); // sort the vector

sort(lst); // sort the singly-linked list

}

The techniques needed to make that work are generally useful.

First, I write two helper functions that take an extra argument indicating whether they are to be used for random-access iterators or forward iterators. The version taking random-access iterator arguments is trivial:

template<typename Ran> // for random-access iterators

void sort_helper(Ran beg, Ran end, random_access_iterator_tag) // we can subscript into [beg:end)

{

sort(beg,end); // just sort it

}

The version for forward iterators simply copies the list into a vector, sorts, and copies back:

template<typename For> // for forward iterators

void sort_helper(For beg, For end, forward_iterator_tag) // we can traverse [beg:end)

{

vector<Value_type<For>> v {beg,end}; // initialize a vector from [beg:end)

sort(v.begin(),v.end()); // use the random access sort

copy(v.begin(),v.end(),beg); // copy the elements back

}

Value_type<For> is the type of For’s elements, called it’s value type. Every standard-library iterator has a member value_type. I get the Value_type<For> notation by defining a type alias (§6.4.2):

template<typename C>

using Value_type = typename C::value_type; // C's value type

Thus, for a vector<X>, Value_type<X> is X.

The real “type magic” is in the selection of helper functions:

template<typename C>

void sort(C& c)

{

using Iter = Iterator_type<C>;

sort_helper(c.begin(),c.end(),Iterator_category<Iter>{});

}

Here, I use two type functions: Iterator_type<C> returns the iterator type of C (that is, C::iterator) and then Iterator_category<Iter>{} constructs a “tag” value indicating the kind of iterator provided:

std::random_access_iterator_tagifC’s iterator supports random accessstd::forward_iterator_tagifC’s iterator supports forward iteration

Given that, we can select between the two sorting algorithms at compile time. This technique, called tag dispatch, is one of several used in the standard library and elsewhere to improve flexibility and performance.

We could define Iterator_type like this:

template<typename C>

using Iterator_type = typename C::iterator; // C's iterator type

However, to extend this idea to types without member types, such as pointers, the standard-library support for tag dispatch comes in the form of a class template iterator_traits from <iterator>. The specialization for pointers looks like this:

template<class T>

struct iterator_traits<T*>{

using difference_type = ptrdiff_t;

using value_type = T;

using pointer = T*;

using reference = T&;

using iterator_category = random_access_iterator_tag;

};

We can now write:

template<typename Iter>

using Iterator_category = typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::iterator_category; // Iter's category

Now an int* can be used as a random-access iterator despite not having a member type; Iterator_category<int*> is random_access_iterator_tag.

Many traits and traits-based techniques will be made redundant by concepts (§7.2). Consider the concepts version of the sort() example:

template<RandomAccessIterator Iter>

void sort(Iter p, Iter q); // use for std::vector and other types supporting random access

template<ForwardIterator Iter>

void sort(Iter p, Iter q)

// use for std::list and other types supporting just forward traversal

{

vector<Value_type<Iter>> v {p,q};

sort(v); // use the random-access sort

copy(v.begin(),v.end(),p);

}

template<RangeR>

void sort(R& r)

{

sort(r.begin(),r.end()); // use the appropriate sort

}

Progress happens.

13.9.2 Type Predicates

In <type_traits>, the standard library offers simple type functions, called type predicates that answers a fundamental question about types. For example:

bool b1 = Is_arithmetic<int>(); // yes, int is an arithmetic type bool b2 = Is_arithmetic<string>(); // no, std::string is not an arithmetic type

Other examples are is_class, is_pod, is_literal_type, has_virtual_destructor, and is_base_of. They are most useful when we write templates. For example:

template<typename Scalar>

class complex {

Scalar re, im;

public:

static_assert(Is_arithmetic<Scalar>(), "Sorry, I only support complex of arithmetic types");

// ...

};

To improve readability compared to using the standard library directly, I defined a type function:

template<typename T>

constexpr bool Is_arithmetic()

{

return std::is_arithmetic<T>::value ;

}

Older programs use ::value directly instead of (), but I consider that quite ugly and it exposes implementation details.

13.9.3 enable_if

Obvious ways of using type predicates includes conditions for static_asserts, compile-time ifs, and enable_ifs. The standard-library enable_if is a widely used mechanism for conditonally introducing definitions. Consider defining a “smart pointer”:

template<typename T>

class Smart_pointer {

T& operator*();

T& operator−>(); // should work if and only if T is a class

};

The −> should be defined if and only if T is a class type. For example, Smart_pointer<vector<T>> should have −>, but Smart_pointer<int> should not. We cannot use a compile-time if because we are not inside a function. Instead, we write

template<typename T>

class Smart_pointer {

T& operator*();

std::enable_if<Is_class<T>(),T&> operator−>(); // is defined if and only if T is a class

};

My type function Is_class() is defined using the type trait is_class in just the way I defined is_aritmetic() in §13.9.2.

If Is_class<T>() is true, the type of operator−>() is T&; otherwise, the definition of operator−>() is ignored.

The syntax of enable_if is odd, awkward to use, and will in many cases be rendered redundant by concepts (§7.2). However, enable_if is the basis for much current template metaprogramming and for many standard-library components. It relies on a subtle language feature called SFINAE (“Substitution Failure Is Not An Error”).

13.10 Advice

[1] A library doesn’t have to be large or complicated to be useful; §13.1.

[2] A resource is anything that has to be acquired and (explicitly or implicitly) released; §13.2.

[3] Use resource handles to manage resources (RAII); §13.2; [CG: R.1].

[4] Use unique_ptr to refer to objects of polymorphic type; §13.2.1; [CG: R.20].

[5] Use shared_ptr to refer to shared objects (only); §13.2.1; [CG: R.20].

[6] Prefer resource handles with specific semantics to smart pointers; §13.2.1.

[7] Prefer unique_ptr to shared_ptr; §5.3, §13.2.1.

[8] Use make_unique() to construct unique_ptrs; §13.2.1; [CG: R.22].

[9] Use make_shared() to construct shared_ptrs; §13.2.1; [CG: R.23].

[10] Prefer smart pointers to garbage collection; §5.3, §13.2.1.

[11] Don’t use std::move(); §13.2.2; [CG: ES.56].

[12] Use std::forward() exclusively for forwarding; §13.2.2.

[13] Never read from an object after std::move()ing or std::forward()ing it; §13.2.2.

[14] Prefer spans to pointer-plus-count interfaces; §13.3; [CG: F.24].

[15] Use array where you need a sequence with a constexpr size; §13.4.1.

[16] Prefer array over built-in arrays; §13.4.1; [CG: SL.con.2].

[17] Use bitset if you need N bits and N is not necessarily the number of bits in a built-in integer type; §13.4.2.

[18] Don’t overuse pair and tuple; named structs often lead to more readable code; §13.4.3.

[19] When using pair, use template argument deduction or make_pair() to avoid redundant type specification; §13.4.3.

[20] When using tuple, use template argument deduction and make_tuple() to avoid redundant type specification; §13.4.3; [CG: T.44].

[21] Prefer variant to explicit use of unions; §13.5.1; [CG: C.181].

[22] Use allocators to prevent memory fragmentation; §13.6.

[23] Time your programs before making claims about efficiency; §13.7.

[24] Use duration_cast to report time measurements with proper units; §13.7.

[25] When specifying a duration, use proper units; §13.7.

[26] Use mem_fn() or a lambda to create function objects that can invoke a member function when called using the traditional function call notation; §13.8.2.

[27] Use function when you need to store something that can be called; §13.8.3.

[28] You can write code to explicitly depend on properties of types; §13.9.

[29] Prefer concepts over traits and enable_if whenever you can; §13.9.

[30] Use aliases and type predicates to simplify notation; §13.9.1, §13.9.2.