10

Input and Output

What you see is all you get.

– Brian W. Kernighan

10.1 Introduction

The I/O stream library provides formatted and unformatted buffered I/O of text and numeric values.

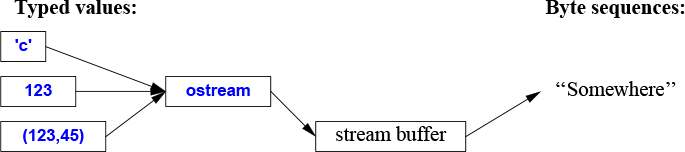

An ostream converts typed objects to a stream of characters (bytes):

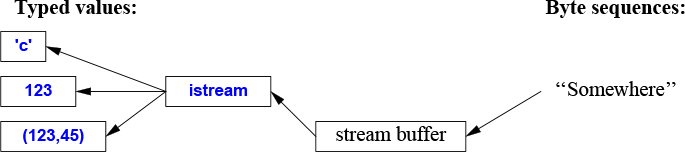

An istream converts a stream of characters (bytes) to typed objects:

The operations on istreams and ostreams are described in §10.2 and §10.3. The operations are type-safe, type-sensitive, and extensible to handle user-defined types (§10.5).

Other forms of user interaction, such as graphical I/O, are handled through libraries that are not part of the ISO standard and therefore not described here.

These streams can be used for binary I/O, be used for a variety of character types, be locale specific, and use advanced buffering strategies, but these topics are beyond the scope of this book.

The streams can be used for input into and output from std::strings (§10.3), for formatting into string buffers (§10.8), and for file I/O (§10.10).

The I/O stream classes all have destructors that free all resources owned (such as buffers and file handles). That is, they are examples of "Resource Acquisition Is Initialization" (RAII; §5.3).

10.2 Output

In <ostream>, the I/O stream library defines output for every built-in type. Further, it is easy to define output of a user-defined type (§10.5). The operator << (“put to”) is used as an output operator on objects of type ostream; cout is the standard output stream and cerr is the standard stream for reporting errors. By default, values written to cout are converted to a sequence of characters. For example, to output the decimal number 10, we can write:

void f()

{

cout << 10;

}

This places the character 1 followed by the character 0 on the standard output stream.

Equivalently, we could write:

void g()

{

int x {10};

cout << x;

}

Output of different types can be combined in the obvious way:

void h(int i)

{

cout << "the value of i is ";

cout << i;

cout << '\n';

}

For h(10), the output will be:

the value of i is 10

People soon tire of repeating the name of the output stream when outputting several related items. Fortunately, the result of an output expression can itself be used for further output. For example:

void h2(int i)

{

cout << "the value of i is " << i << '\n';

}

This h2() produces the same output as h().

A character constant is a character enclosed in single quotes. Note that a character is output as a character rather than as a numerical value. For example:

void k()

{

int b = 'b'; // note: char implicitly converted to int

char c = 'c';

cout << 'a' << b << c;

}

The integer value of the character 'b' is 98 (in the ASCII encoding used on the C++ implementation that I used), so this will output a98c.

10.3 Input

In <istream>, the standard library offers istreams for input. Like ostreams, istreams deal with character string representations of built-in types and can easily be extended to cope with user-defined types.

The operator >> (“get from”) is used as an input operator; cin is the standard input stream. The type of the right-hand operand of >> determines what input is accepted and what is the target of the input operation. For example:

void f()

{

int i;

cin >> i; // read an integer into i

double d;

cin >> d; // read a double-precision floating-point number into d

}

This reads a number, such as 1234, from the standard input into the integer variable i and a floating-point number, such as 12.34e5, into the double-precision floating-point variable d.

Like output operations, input operations can be chained, so I could equivalently have written:

void f()

{

int i;

double d;

cin >> i >> d; // read into i and d

}

In both cases, the read of the integer is terminated by any character that is not a digit. By default, >> skips initial whitespace, so a suitable complete input sequence would be

1234 12.34e5

Often, we want to read a sequence of characters. A convenient way of doing that is to read into a string. For example:

void hello()

{

cout << "Please enter your name\n";

string str;

cin >> str;

cout << "Hello, " << str << "!\n";

}

If you type in Eric the response is:

Hello, Eric!

By default, a whitespace character, such as a space or a newline, terminates the read, so if you enter Eric Bloodaxe pretending to be the ill-fated king of York, the response is still:

Hello, Eric!

You can read a whole line using the getline() function. For example:

void hello_line()

{

cout << "Please enter your name\n";

string str;

getline(cin,str);

cout << "Hello, " << str << "!\n";

}

With this program, the input Eric Bloodaxe yields the desired output:

Hello, Eric Bloodaxe!

The newline that terminated the line is discarded, so cin is ready for the next input line.

Using the formatted I/O operations is usually less error-prone, more efficient, and less code than manipulating characters one by one. In particular, istreams take care of memory management and range checking. We can do formatting to and from memory using stringstreamss (§10.8).

The standard strings have the nice property of expanding to hold what you put in them; you don’t have to pre-calculate a maximum size. So, if you enter a couple of megabytes of semicolons, the program will echo pages of semicolons back at you.

10.4 I/O State

An iostream has a state that we can examine to determine whether an operation succeeded. The most common use is to read a sequence of values:

vector<int> read_ints(istream& is)

{

vector<int> res;

for (int i; is>>i; )

res.push_back(i);

return res;

}

This reads from is until something that is not an integer is encountered. That something will typically be the end of input. What is happening here is that the operation is>>i returns a reference to is, and testing an iostream yields true if the stream is ready for another operation.

In general, the I/O state holds all the information needed to read or write, such as formatting information (§10.6), error state (e.g., has end-of-input been reached?), and what kind of buffering is used. In particular, a user can set the state to reflect that an error has occurred (§10.5) and clear the state if an error wasn’t serious. For example, we could imagine a version of read_ints() that accepted a terminating string:

vector<int> read_ints(istream& is, const string& terminator)

{

vector<int> res;

for (int i; is >> i; )

res.push_back(i);

if (is.eof()) // fine: end of file

return res;

if (is.fail()) { // we failed to read an int; was it the terminator?

is.clear(); // reset the state to good()

is.unget(); // put the non-digit back into the stream

string s;

if (cin>>s && s==terminator)

return res;

cin.setstate(ios_base::failbit); // add fail() to cin's state

}

return res;

}

auto v = read_ints(cin,"stop");

10.5 I/O of User-Defined Types

In addition to the I/O of built-in types and standard strings, the iostream library allows programmers to define I/O for their own types. For example, consider a simple type Entry that we might use to represent entries in a telephone book:

struct Entry {

string name;

int number;

};

We can define a simple output operator to write an Entry using a {"name",number} format similar to the one we use for initialization in code:

ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Entry& e)

{

return os << "{\"" << e.name << "\", " << e.number << "}";

}

A user-defined output operator takes its output stream (by reference) as its first argument and returns it as its result.

The corresponding input operator is more complicated because it has to check for correct formatting and deal with errors:

istream& operator>>(istream& is, Entry& e)

// read { "name", number } pair. Note: formatted with { " ", and }

{

char c, c2;

if (is>>c && c=='{' && is>>c2 && c2=='"') { // start with a { "

string name; // the default value of a string is the empty string: ""

while (is.get(c) && c!='"') // anything before a " is part of the name

name+=c;

if (is>>c && c==',') {

int number = 0;

if (is>>number>>c && c=='}') { // read the number and a }

e = {name,number}; // assign to the entry

return is;

}

}

}

is.setstate(ios_base::failbit); // register the failure in the stream

return is;

}

An input operation returns a reference to its istream that can be used to test if the operation succeeded. For example, when used as a condition, is>>c means “Did we succeed at reading a char from is into c?”

The is>>c skips whitespace by default, but is.get(c) does not, so this Entry-input operator ignores (skips) whitespace outside the name string, but not within it. For example:

{ "John Marwood Cleese", 123456 }

{"Michael Edward Palin", 987654}

We can read such a pair of values from input into an Entry like this:

for (Entryee; cin>>ee; ) // read from cin into ee

cout << ee << '\n'; // write ee to cout

The output is:

{"John Marwood Cleese", 123456}

{"Michael Edward Palin", 987654}

See §9.4 for a more systematic technique for recognizing patterns in streams of characters (regular expression matching).

10.6 Formatting

The iostream library provides a large set of operations for controlling the format of input and output. The simplest formatting controls are called manipulators and are found in <ios>, <istream>, <ostream>, and <iomanip> (for manipulators that take arguments). For example, we can output integers as decimal (the default), octal, or hexadecimal numbers:

cout << 1234 << ',' << hex << 1234 << ',' << oct << 1234 << '\n'; // print 1234,4d2,2322

We can explicitly set the output format for floating-point numbers:

constexpr double d = 123.456;

cout << d << "; " // use the default format for d

<< scientific << d << "; " // use 1.123e2 style format for d

<< hexfloat << d << "; " // use hexadecimal notation for d

<< fixed << d << "; " // use 123.456 style format for d

<< defaultfloat << d << '\n'; // use the default format for d

This produces:

123.456; 1.234560e+002; 0x1.edd2f2p+6; 123.456000; 123.456

Precision is an integer that determines the number of digits used to display a floating-point number:

The general format (

defaultfloat) lets the implementation choose a format that presents a value in the style that best preserves the value in the space available. The precision specifies the maximum number of digits.The scientific format (

scientific) presents a value with one digit before a decimal point and an exponent. The precision specifies the maximum number of digits after the decimal point.The fixed format (

fixed) presents a value as an integer part followed by a decimal point and a fractional part. The precision specifies the maximum number of digits after the decimal point.

Floating-point values are rounded rather than just truncated, and precision() doesn’t affect integer output. For example:

cout.precision(8); cout << 1234.56789 << ' ' << 1234.56789 << ' ' << 123456 << '\n'; cout.precision(4); cout << 1234.56789 << ' ' << 1234.56789 << ' ' << 123456 << '\n'; cout << 1234.56789 << '\n';

This produces:

1234.5679 1234.5679 123456 1235 1235 123456 1235

These floating-point manipulators are “sticky”; that is, their effects persist for subsequent floating-point operations.

10.7 File Streams

In <fstream>, the standard library provides streams to and from a file:

ifstreams for reading from a fileofstreams for writing to a filefstreams for reading from and writing to a file

For example:

ofstream ofs {"target"}; // "o" for "output"

if (!ofs)

error("couldn't open 'target' for writing");

Testing that a file stream has been properly opened is usually done by checking its state.

ifstream ifs {"source"}; // "i" for "input"

if (!ifs)

error("couldn't open 'source' for reading");

Assuming that the tests succeeded, ofs can be used as an ordinary ostream (just like cout) and ifs can be used as an ordinary istream (just like cin).

File positioning and more detailed control of the way a file is opened is possible, but beyond the scope of this book.

For the composition of file names and file system manipulation, see §10.10.

10.8 String Streams

In <sstream>, the standard library provides streams to and from a string:

istringstreams for reading from astringostringstreams for writing to astringstringstreams for reading from and writing to astring.

For example:

void test()

{

ostringstream oss;

oss << "{temperature," << scientific << 123.4567890 << "}";

cout << oss.str() << '\n';

}

The result from an ostringstream can be read using str(). One common use of an ostringstream is to format before giving the resulting string to a GUI. Similarly, a string received from a GUI can be read using formatted input operations (§10.3) by putting it into an istringstream.

A stringstream can be used for both reading and writing. For example, we can define an operation that can convert any type with a string representation into another that can also be represented as a string:

template<typename Target =string, typename Source =string>

Target to(Source arg) // convert Source to Target

{

stringstream interpreter;

Target result;

if (!(interpreter << arg) // write arg into stream

|| !(interpreter >> result) // read result from stream

|| !(interpreter >> std::ws).eof()) // stuff left in stream?

throw runtime_error{"to<>() failed"};

return result;

}

A function template argument needs to be explicitly mentioned only if it cannot be deduced or if there is no default (§7.2.4), so we can write:

auto x1 = to<string,double>(1.2); // very explicit (and verbose)

auto x2 = to<string>(1.2); // Source is deduced to double

auto x3 = to<>(1.2); // Target is defaulted to string; Source is deduced to double

auto x4 = to(1.2); // the <> is redundant;

// Target is defaulted to string; Source is deduced to double

If all function template arguments are defaulted, the <> can be left out.

I consider this a good example of the generality and ease of use that can be achieved by a combination of language features and standard-library facilities.

10.9 C-style I/O

The C++ standard library also supports the C standard-library I/O, including printf() and scanf(). Many uses of this library are unsafe from a type and security point-of-view, so I don’t recommend its use. In particular, it can be difficult to use for safe and convenient input. It does not support user-defined types. If you don’t use C-style I/O and care about I/O performance, call

ios_base::sync_with_stdio(false); // avoid significant overhead

Without that call, iostreams can be significantly slowed down to be compatible with the C-style I/O.

10.10 File System

Most systems have a notion of a file system providing access to permanent information stored as files. Unfortunately, the properties of file systems and the ways of manipulating them vary greatly. To deal with that, the file system library in <filesystem> offers a uniform interface to most facilities of most file systems. Using <filesystem>, we can portably

express file system paths and navigate through a file system

examine file types and the permissions associated with them

The filesystem library can handle unicode, but explaining how is beyond the scope of this book. I recommend the cppreference [Cppreference] and the Boost filesystem documentation [Boost] for detailed information.

Consider an example:

path f = "dir/hypothetical.cpp"; // naming a file

assert(exists(f)); // f must exist

if (is_regular_file(f)) // is f an ordinary file?

cout << f << " is a file; its size is " << file_size(f) << '\n';

Note that a program manipulating a file system is usually running on a computer together with other programs. Thus, the contents of a file system can change between two commands. For example, even though we first of all carefully asserted that f existed, that may no longer be true when on the next line, we ask if f is a regular file.

A path is quite a complicated class, capable of handling the native character sets and conventions of many operating systems. In particular, it can handle file names from command lines as presented by main(); for example:

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

if (argc < 2) {

cerr << "arguments expected\n";

return 1;

}

path p {argv[1]}; // create a path from the command line

cout << p << " " << exists(p) << '\n'; // note: a path can be printed like a string

// ...

}

A path is not checked for validity until it is used. Even then, its validity depends on the conventions of the system on which the program runs.

Naturally, a path can be used to open a file

void use(path p)

{

ofstream f {p};

if (!f) error("bad file name: ", p);

f << "Hello, file!";

}

In addition to path, <filesystem> offers types for traversing directories and inquiring about the properties of the files found:

File System Types (partial) |

|

|

A directory path |

|

A file system exception |

|

A directory entry |

|

For iterating over a directory |

|

For iterating over a directory and its subdirectories |

Consider a simple, but not completely unrealistic, example:

void print_directory(path p)

try

{

if (is_directory(p)) {

cout << p << ":\n";

for (const directory_entry& x : directory_iterator{p})

cout << " " << x.path() << '\n';

}

}

catch (const filesystem_error& ex) {

cerr << ex.what() << '\n';

}

A string can be implicitly converted to a path so we can exercise print_directory like this:

void use()

{

print_directory("."); // current directory

print_directory(".."); // parent directory

print_directory("/"); // Unix root directory

print_directory("c:"); // Windows volume C

for (string s; cin>>s; )

print_directory(s);

}

Had I wanted to list subdirectories also, I would have said recursive_directory_iterator{p}. Had I wanted to print entries in lexicographical order, I would have copied the paths into a vector and sorted that before printing.

Class path offers many common and useful operations:

Path Operations (partial) |

|

|

Character type used by the native encoding of the filesystem: |

|

|

|

A |

|

Alias for |

|

Assign |

|

|

|

|

|

The native format of |

|

|

|

|

|

The filename part of |

|

The stem part of |

|

The file extension part of |

|

The beginning of |

|

The end of |

|

Equality and inequality for |

|

Lexicographical comparisons |

|

Stream I/O to/from |

|

A path from a UTF-8 encoded source |

For example:

void test(path p)

{

if (is_directory(p)) {

cout << p << ":\n";

for (const directory_entry& x : directory_iterator(p)) {

const path& f = x; // refer to the path part of a directory entry

if (f.extension() == ".exe")

cout << f.stem() << " is a Windows executable\n";

else {

string n = f.extension().string();

if (n == ".cpp" || n == ".C" || n == ".cxx")

cout << f.stem() << " is a C++ source file\n";

}

}

}

}

We use a path as a string (e.g., f.extension) and we can extract strings of various types from a path (e.g., f.extension().string()).

Note that naming conventions, natural languages, and string encodings are rich in complexity. The filesystem-library abstractions offer portability and great simplification.

File System Operations (partial) |

|

|

Does |

|

Copy files or directories from |

|

Copy files or directories; report errors as error codes |

|

Copy file contents from |

|

Create new directory named |

|

Create new directory named |

|

|

|

Make |

|

|

|

Remove |

Many operations have overloads that take extra arguments, such as operating systems permissions. The handling of such is far beyond the scope of this book, so look them up if you need them.

Like copy(), all operations come in two versions:

The basic version as listed in the table, e.g.,

exists(p). The function will throwfilesystem_errorif the operation failed.A version with an extra

error_codeargument, e.g.,exists(p,e). Checketo see if the operations succeeded.

We use the error codes when operations are expected to fail frequently in normal use and the throwing operations when an error is considered exceptional.

Often, using an inquiry function is the simplest and most straightforward approach to examining the properties of a file. The <filesystem> library knows about a few common kinds of files and classifies the rest as “other”:

File types |

|

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

|

Is |

10.11 Advice

[1] iostreams are type-safe, type-sensitive, and extensible; §10.1.

[2] Use character-level input only when you have to; §10.3; [CG: SL.io.1].

[3] When reading, always consider ill-formed input; §10.3; [CG: SL.io.2].

[4] Avoid endl (if you don’t know what endl is, you haven’t missed anything); [CG: SL.io.50].

[5] Define << and >> for user-defined types with values that have meaningful textual representations; §10.1, §10.2, §10.3.

[6] Use cout for normal output and cerr for errors; §10.1.

[7] There are iostreams for ordinary characters and wide characters, and you can define an iostream for any kind of character; §10.1.

[8] Binary I/O is supported; §10.1.

[9] There are standard iostreams for standard I/O streams, files, and strings; §10.2, §10.3, §10.7, §10.8.

[10] Chain << operations for a terser notation; §10.2.

[11] Chain >> operations for a terser notation; §10.3.

[12] Input into strings does not overflow; §10.3.

[13] By default >> skips initial whitespace; §10.3.

[14] Use the stream state fail to handle potentially recoverable I/O errors; §10.4.

[15] You can define << and >> operators for your own types; §10.5.

[16] You don’t need to modify istream or ostream to add new << and >> operators; §10.5.

[17] Use manipulators to control formatting; §10.6.

[18] precision() specifications apply to all following floating-point output operations; §10.6.

[19] Floating-point format specifications (e.g., scientific) apply to all following floating-point output operations; §10.6.

[20] #include <ios> when using standard manipulators; §10.6.

[21] #include <iomanip> when using standard manipulators taking arguments; §10.6.

[22] Don’t try to copy a file stream.

[23] Remember to check that a file stream is attached to a file before using it; §10.7.

[24] Use stringstreams for in-memory formatting; §10.8.

[25] You can define conversions between any two types that both have string representation; §10.8.

[26] C-style I/O is not type-safe; §10.9.

[27] Unless you use printf-family functions call ios_base::sync_with_stdio(false); §10.9; [CG: SL.io.10].

[28] Prefer <filesystem> to direct use of a specific operating system interfaces; §10.10.