3

Modularity

Don’t interrupt me while I’m interrupting.

– Winston S. Churchill

-

Exceptions; Invariants; Error-Handling Alternatives; Contracts; Static Assertions

3.1 Introduction

A C++ program consists of many separately developed parts, such as functions (§1.2.1), user-defined types (Chapter 2), class hierarchies (§4.5), and templates (Chapter 6). The key to managing this is to clearly define the interactions among those parts. The first and most important step is to distinguish between the interface to a part and its implementation. At the language level, C++ represents interfaces by declarations. A declaration specifies all that’s needed to use a function or a type. For example:

double sqrt(double); // the square root function takes a double and returns a double

class Vector {

public:

Vector(int s);

double& operator[](int i);

int size();

private:

double* elem; // elem points to an array of sz doubles

int sz;

};

The key point here is that the function bodies, the function definitions, are “elsewhere.” For this example, we might like for the representation of Vector to be “elsewhere” also, but we will deal with that later (abstract types; §4.3). The definition of sqrt() will look like this:

double sqrt(double d) // definition of sqrt()

{

// ... algorithm as found in math textbook ...

}

For Vector, we need to define all three member functions:

Vector::Vector(int s) // definition of the constructor

:elem{new double[s]}, sz{s} // initialize members

{

}

double& Vector::operator[](int i) // definition of subscripting

{

return elem[i];

}

int Vector::size() // definition of size()

{

return sz;

}

We must define Vector’s functions, but not sqrt() because it is part of the standard library. However, that makes no real difference: a library is simply “some other code we happen to use” written with the same language facilities we use.

There can be many declarations for an entity, such as a function, but only one definition.

3.2 Separate Compilation

C++ supports a notion of separate compilation where user code sees only declarations of the types and functions used. The definitions of those types and functions are in separate source files and are compiled separately. This can be used to organize a program into a set of semi-independent code fragments. Such separation can be used to minimize compilation times and to strictly enforce separation of logically distinct parts of a program (thus minimizing the chance of errors). A library is often a collection of separately compiled code fragments (e.g., functions).

Typically, we place the declarations that specify the interface to a module in a file with a name indicating its intended use. For example:

// Vector.h:

class Vector {

public:

Vector(int s);

double& operator[](int i);

int size();

private:

double* elem; // elem points to an array of sz doubles

int sz;

};

This declaration would be placed in a file Vector.h. Users then include that file, called a header file, to access that interface. For example:

// user.cpp:

#include "Vector.h" // get Vector's interface

#include <cmath> // get the standard-library math function interface including sqrt()

double sqrt_sum(Vector& v)

{

double sum = 0;

for (int i=0; i!=v.size(); ++i)

sum+=std::sqrt(v[i]); // sum of square roots

return sum;

}

To help the compiler ensure consistency, the .cpp file providing the implementation of Vector will also include the .h file providing its interface:

// Vector.cpp:

#include "Vector.h" // get Vector's interface

Vector::Vector(int s)

:elem{new double[s]}, sz{s} // initialize members

{

}

double& Vector::operator[](int i)

{

return elem[i];

}

int Vector::size()

{

return sz;

}

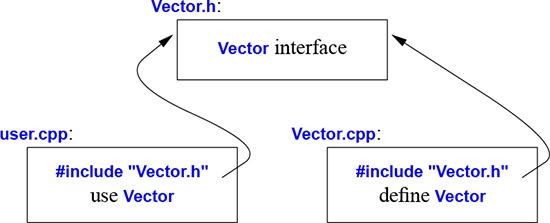

The code in user.cpp and Vector.cpp shares the Vector interface information presented in Vector.h, but the two files are otherwise independent and can be separately compiled. Graphically, the program fragments can be represented like this:

Strictly speaking, using separate compilation isn’t a language issue; it is an issue of how best to take advantage of a particular language implementation. However, it is of great practical importance. The best approach to program organization is to think of the program as a set of modules with well-defined dependencies, represent that modularity logically through language features, and then exploit the modularity physically through files for effective separate compilation.

A .cpp file that is compiled by itself (including the h files it #includes) is called a translation unit. A program can consist of many thousand translation units.

3.3 Modules (C++20)

The use of #includes is a very old, error-prone, and rather expensive way of composing programs out of parts. If you #include header.h in 101 translation units, the text of header.h will be processed by the compiler 101 times. If you #include header1.h before header2.h the declarations and macros in header1.h might affect the meaning of the code in header2.h. If instead you #include header2.h before header1.h, it is header2.h that might affect the code in header1.h. Obviously, this is not ideal, and in fact it has been a major source of cost and bugs since 1972 when this mechanism was first introduced into C.

We are finally about to get a better way of expressing physical modules in C++. The language feature, called modules is not yet ISO C++, but it is an ISO Technical Specification [ModulesTS]. Implementations are in use, so I risk recommending it here even though details are likely to change and it may be years before everybody can use it in production code. Old code, in this case code using #include, can “live” for a very long time because it can be costly and time consuming to update.

Consider how to express the Vector and sqrt_sum() example from §3.2 using modules:

// file Vector.cpp:

module; // this compilation will define a module

// ... here we put stuff that Vector might need for its implementation ...

export module Vector; // defining the module called "Vector"

export class Vector {

public:

Vector(int s);

double& operator[](int i);

int size();

private:

double* elem; // elem points to an array of sz doubles

int sz;

};

Vector::Vector(int s)

:elem{new double[s]}, sz{s} // initialize members

{

}

double& Vector::operator[](int i)

{

return elem[i];

}

int Vector::size()

{

return sz;

}

export int size(const Vector& v) { return v.size(); }

This defines a module called Vector, which exports the class Vector, all its member functions, and the non-member function size().

The way we use this module is to import it where we need it. For example:

// file user.cpp:

import Vector; // get Vector's interface

#include <cmath> // get the standard-library math function interface including sqrt()

double sqrt_sum(Vector& v)

{

double sum = 0;

for (int i=0; i!=v.size(); ++i)

sum+=std::sqrt(v[i]); // sum of square roots

return sum;

}

I could have imported the standard library mathematical functions also, but I used the old-fashioned #include just to show that you can mix old and new. Such mixing is essential for gradually upgrading older code from using #include to import.

The differences between headers and modules are not just syntactic.

A module is compiled once only (rather than in each translation unit in which it is used).

Two modules can be

imported in either order without changing their meaning.If you import something into a module, users of your module do not implicitly gain access to (and are not bothered by) what you imported:

importis not transitive.

The effects on maintainability and compile-time performance can be spectacular.

3.4 Namespaces

In addition to functions (§1.3), classes (§2.3), and enumerations (§2.5), C++ offers namespaces as a mechanism for expressing that some declarations belong together and that their names shouldn’t clash with other names. For example, I might want to experiment with my own complex number type (§4.2.1, §14.4):

namespace My_code {

class complex {

// ...

};

complex sqrt(complex);

// ...

int main();

}

int My_code::main()

{

complex z {1,2};

auto z2 = sqrt(z);

std::cout << '{' << z2.real() << ',' << z2.imag() << "}\n";

// ...

}

int main()

{

return My_code::main();

}

By putting my code into the namespace My_code, I make sure that my names do not conflict with the standard-library names in namespace std (§3.4). That precaution is wise, because the standard library does provide support for complex arithmetic (§4.2.1, §14.4).

The simplest way to access a name in another namespace is to qualify it with the namespace name (e.g., std::cout and My_code::main). The “real main()” is defined in the global namespace, that is, not local to a defined namespace, class, or function.

If repeatedly qualifying a name becomes tedious or distracting, we can bring the name into a scope with a using-declaration:

void my_code(vector<int>& x, vector<int>& y)

{

using std::swap; // use the standard-library swap

// ...

swap(x,y); // std::swap()

other::swap(x,y); // some other swap()

// ...

}

A using-declaration makes a name from a namespace usable as if it was declared in the scope in which it appears. After using std::swap, it is exactly as if swap had been declared in my_code().

To gain access to all names in the standard-library namespace, we can use a using-directive:

using namespace std;

A using-directive makes unqualified names from the named namespace accessible from the scope in which we placed the directive. So after the using-directive for std, we can simply write cout rather than std::cout. By using a using-directive, we lose the ability to selectively use names from that namespace, so this facility should be used carefully, usually for a library that’s pervasive in an application (e.g., std) or during a transition for an application that didn’t use namespaces.

Namespaces are primarily used to organize larger program components, such as libraries. They simplify the composition of a program out of separately developed parts.

3.5 Error Handling

Error handling is a large and complex topic with concerns and ramifications that go far beyond language facilities into programming techniques and tools. However, C++ provides a few features to help. The major tool is the type system itself. Instead of painstakingly building up our applications from the built-in types (e.g., char, int, and double) and statements (e.g., if, while, and for), we build types (e.g., string, map, and regex) and algorithms (e.g., sort(), find_if(), and draw_all()) that are appropriate for our applications. Such higher-level constructs simplify our programming, limit our opportunities for mistakes (e.g., you are unlikely to try to apply a tree traversal to a dialog box), and increase the compiler’s chances of catching errors. The majority of C++ language constructs are dedicated to the design and implementation of elegant and efficient abstractions (e.g., user-defined types and algorithms using them). One effect of such abstraction is that the point where a run-time error can be detected is separated from the point where it can be handled. As programs grow, and especially when libraries are used extensively, standards for handling errors become important. It is a good idea to articulate a strategy for error handling early on in the development of a program.

3.5.1 Exceptions

Consider again the Vector example. What ought to be done when we try to access an element that is out of range for the vector from §2.3?

The writer of

Vectordoesn’t know what the user would like to have done in this case (the writer ofVectortypically doesn’t even know in which program the vector will be running).The user of

Vectorcannot consistently detect the problem (if the user could, the out-of-range access wouldn’t happen in the first place).

Assuming that out-of-range access is a kind of error that we want to recover from, the solution is for the Vector implementer to detect the attempted out-of-range access and tell the user about it. The user can then take appropriate action. For example, Vector::operator[]() can detect an attempted out-of-range access and throw an out_of_range exception:

double& Vector::operator[](int i)

{

if (i<0 || size()<=i)

throw out_of_range{"Vector::operator[]"};

return elem[i];

}

The throw transfers control to a handler for exceptions of type out_of_range in some function that directly or indirectly called Vector::operator[](). To do that, the implementation will unwind the function call stack as needed to get back to the context of that caller. That is, the exception handling mechanism will exit scopes and functions as needed to get back to a caller that has expressed interest in handling that kind of exception, invoking destructors (§4.2.2) along the way as needed. For example:

void f(Vector& v)

{

// ...

try{ // exceptions here are handled by the handler defined below

v[v.size()] = 7; // try to access beyond the end of v

}

catch (out_of_range& err) { // oops: out_of_range error

// ... handle range error ...

cerr << err.what() << '\n';

}

// ...

}

We put code for which we are interested in handling exceptions into a try-block. The attempted assignment to v[v.size()] will fail. Therefore, the catch-clause providing a handler for exceptions of type out_of_range will be entered. The out_of_range type is defined in the standard library (in <stdexcept>) and is in fact used by some standard-library container access functions.

I caught the exception by reference to avoid copying and used the what() function to print the error message put into it at the throw-point.

Use of the exception-handling mechanisms can make error handling simpler, more systematic, and more readable. To achieve that, don’t overuse try-statements. The main technique for making error handling simple and systematic (called Resource Acquisition Is Initialization; RAII) is explained in §4.2.2. The basic idea behind RAII is for a constructor to acquire all resources necessary for a class to operate and have the destructor release all resources, thus making resource release guaranteed and implicit.

A function that should never throw an exception can be declared noexcept. For example:

void user(int sz) noexcept

{

Vector v(sz);

iota(&v[0],&v[sz],1); // fill v with 1,2,3,4... (see §14.3)

// ...

}

If all good intent and planning fails, so that user() still throws, std::terminate() is called to immediately terminate the program.

3.5.2 Invariants

The use of exceptions to signal out-of-range access is an example of a function checking its argument and refusing to act because a basic assumption, a precondition, didn’t hold. Had we formally specified Vector’s subscript operator, we would have said something like “the index must be in the [0:size()) range,” and that was in fact what we tested in our operator[](). The [a:b) notation specifies a half-open range, meaning that a is part of the range, but b is not. Whenever we define a function, we should consider what its preconditions are and consider whether to test them (§3.5.3). For most applications it is a good idea to test simple invariants; see also §3.5.4.

However, operator[]() operates on objects of type Vector and nothing it does makes any sense unless the members of Vector have “reasonable” values. In particular, we did say “elem points to an array of sz doubles” but we only said that in a comment. Such a statement of what is assumed to be true for a class is called a class invariant, or simply an invariant. It is the job of a constructor to establish the invariant for its class (so that the member functions can rely on it) and for the member functions to make sure that the invariant holds when they exit. Unfortunately, our Vector constructor only partially did its job. It properly initialized the Vector members, but it failed to check that the arguments passed to it made sense. Consider:

Vector v(−27);

This is likely to cause chaos.

Here is a more appropriate definition:

Vector::Vector(int s)

{

if (s<0)

throw length_error{"Vector constructor: negative size"};

elem = new double[s];

sz = s;

}

I use the standard-library exception length_error to report a non-positive number of elements because some standard-library operations use that exception to report problems of this kind. If operator new can’t find memory to allocate, it throws a std::bad_alloc. We can now write:

void test()

{

try{

Vector v(−27);

}

catch (std::length_error& err) {

// handle negative size

}

catch (std::bad_alloc& err) {

// handle memory exhaustion

}

}

You can define your own classes to be used as exceptions and have them carry arbitrary information from a point where an error is detected to a point where it can be handled (§3.5.1).

Often, a function has no way of completing its assigned task after an exception is thrown. Then, “handling” an exception means doing some minimal local cleanup and rethrowing the exception. For example:

void test()

{

try{

Vector v(−27);

}

catch (std::length_error&) { // do something and rethrow

cerr << "test failed: length error\n";

throw; // rethrow

}

catch (std::bad_alloc&) { // Ouch! this program is not designed to handle memory exhaustion

std::terminate(); // terminate the program

}

}

In well-designed code try-blocks are rare. Avoid overuse by systematically using the RAII technique (§4.2.2, §5.3).

The notion of invariants is central to the design of classes, and preconditions serve a similar role in the design of functions. Invariants

help us to understand precisely what we want

force us to be specific; that gives us a better chance of getting our code correct (after debugging and testing).

The notion of invariants underlies C++’s notions of resource management supported by constructors (Chapter 4) and destructors (§4.2.2, §13.2).

3.5.3 Error-Handling Alternatives

Error handling is a major issue in all real-world software, so naturally there are a variety of approaches. If an error is detected and it cannot be handled locally in a function, the function must somehow communicate the problem to some caller. Throwing an exception is C++’s most general mechanism for that.

There are languages where exceptions are designed simply to provide an alternate mechanism for returning values. C++ is not such a language: exceptions are designed to be used to report failure to complete a given task. Exceptions are integrated with constructors and destructors to provide a coherent framework for error handling and resource management (§4.2.2, §5.3). Compilers are optimized to make returning a value much cheaper than throwing the same value as an exception.

Throwing an exception is not the only way of reporting an error that cannot be handled locally. A function can indicate that it cannot perform its allotted task by:

throwing an exception

somehow return a value indicating failure

terminating the program (by invoking a function like

terminate(),exit(), orabort()).

We return an error indicator (an “error code”) when:

A failure is normal and expected. For example, it is quite normal for a request to open a file to fail (maybe there is no file of that name or maybe the file cannot be opened with the permissions requested).

An immediate caller can reasonably be expected to handle the failure.

We throw an exception when:

An error is so rare that a programmer is likely to forget to check for it. For example, when did you last check the return value of

printf()?An error cannot be handled by an immediate caller. Instead, the error has to percolate back to an ultimate caller. For example, it is infeasible to have every function in an application reliably handle every allocation failure or network outage.

New kinds of errors can be added in lower-modules of an application so that higher-level modules are not written to cope with such errors. For example, when a previously single-threaded application is modified to use multiple threads or resources are placed remotely to be accessed over a network.

No suitable return path for errors codes are available. For example, a constructor does not have a return value for a “caller” to check. In particular, constructors may be invoked for several local variables or in a partially constructed complex object so that clean-up based on error codes would be quite complicated.

The return path of a function is made more complicated or expensive by a need to pass both a value and an error indicator back (e.g., a

pair; §13.4.3), possibly leading to the use of out-parameters, non-local error-status indicators, or other workarounds.The error has to be transmitted up a call chain to an “ultimate caller.” Repeatedly checking an error-code would be tedious, expensive, and error-prone.

The recovery from errors depends on the results of several function calls, leading to the need to maintain local state between calls and complicated control structures.

The function that found the error was a callback (a function argument), so the immediate caller may not even know what function was called.

An error implies that some “undo action” is needed.

We terminate when

An error is of a kind from which we cannot recover. For example, for many – but not all – systems there is no reasonable way to recover from memory exhaustion.

The system is one where error-handling is based on restarting a thread, process, or computer whenever a non-trivial error is detected.

One way to ensure termination is to add noexcept to a function so that a throw from anywhere in the function’s implementation will turn into a terminate(). Note that there are applications that can’t accept unconditional terminations, so alternatives must be used.

Unfortunately, these conditions are not always logically disjoint and easy to apply. The size and complexity of a program matters. Sometimes the tradeoffs change as an application evolves. Experience is required. When in doubt, prefer exceptions because their use scales better, and don’t require external tools to check that all errors are handled.

Don’t believe that all error codes or all exceptions are bad; there are clear uses for both. Furthermore, do not believe the myth that exception handling is slow; it is often faster than correct handling of complex or rare error conditions, and of repeated tests of error codes.

RAII (§4.2.2, §5.3) is essential for simple and efficient error-handling using exceptions. Code littered with try-blocks often simply reflects the worst aspects of error-handling strategies conceived for error codes.

3.5.4 Contracts

There is currently no general and standard way of writing optional run-time tests of invariants, preconditions, etc. A contract mechanism is proposed for C++20 [Garcia,2016] [Garcia,2018]. The aim is to support users who want to rely on testing to get programs right – running with extensive run-time checks – but then deploy code with minimal checks. This is popular in high-performance applications in organizations that rely on systematic and extensive checking.

For now, we have to rely on ad hoc mechanisms. For example, we could use a command-line macro to control a run-time check:

double& Vector::operator[](int i)

{

if (RANGE_CHECK && (i<0 || size()<=i))

throw out_of_range{"Vector::operator[]"};

return elem[i];

}

The standard library offers the debug macro, assert(), to assert that a condition must hold at run time. For example:

void f(const char* p)

{

assert(p!=nullptr); // p must not be the nullptr

// ...

}

If the condition of an assert() fails in “debug mode,” the program terminates. If we are not in debug mode, the assert() is not checked. That’s pretty crude and inflexible, but often sufficient.

3.5.5 Static Assertions

Exceptions report errors found at run time. If an error can be found at compile time, it is usually preferable to do so. That’s what much of the type system and the facilities for specifying the interfaces to user-defined types are for. However, we can also perform simple checks on most properties that are known at compile time and report failures to meet our expectations as compiler error messages. For example:

static_assert(4<=sizeof(int), "integers are too small"); // check integer size

This will write integers are too small if 4<=sizeof(int) does not hold; that is, if an int on this system does not have at least 4 bytes. We call such statements of expectations assertions.

The static_assert mechanism can be used for anything that can be expressed in terms of constant expressions (§1.6). For example:

constexpr double C = 299792.458; // km/s

void f(double speed)

{

constexpr double local_max = 160.0/(60*60); // 160 km/h == 160.0/(60*60) km/s

static_assert(speed<C,"can't go that fast"); // error: speed must be a constant

static_assert(local_max<C,"can't go that fast"); // OK

// ...

}

In general, static_assert(A,S) prints S as a compiler error message if A is not true. If you don’t want a specific message printed, leave out the S and the compiler will supply a default message:

static_assert(4<=sizeof(int)); // use default message

The default message is typically the source location of the static_assert plus a character representation of the asserted predicate.

The most important uses of static_assert come when we make assertions about types used as parameters in generic programming (§7.2, §13.9).

3.6 Function Arguments and Return Values

The primary and recommended way of passing information from one part of a program to another is through a function call. Information needed to perform a task is passed as arguments to a function and the results produced are passed back as return values. For example:

int sum(const vector<int>& v)

{

int s = 0;

for (const int i : v)

s += i;

return s;

}

vector fib = {1,2,3,5,8,13,21};

int x = sum(fib); // x becomes 53

There are other paths through which information can be passed between functions, such as global variables (§1.5), pointer and reference parameters (§3.6.1), and shared state in a class object (Chapter 4). Global variables are strongly discouraged as a known source of errors, and state should typically be shared only between functions jointly implementing a well-defined abstraction (e.g., member functions of a class; §2.3).

Given the importance of passing information to and from functions, it is not surprising that there are a variety of ways of doing it. Key concerns are:

Is an object copied or shared?

If an object is shared, is it mutable?

Is an object moved, leaving an “empty object” behind (§5.2.2)?

The default behavior for both argument passing and value return is “copy” (§1.9), but some copies can implicitly be optimized to moves.

In the sum() example, the resulting int is copied out of sum() but it would be inefficient and pointless to copy the potentially very large vector into sum(), so the argument is passed by reference (indicated by the &; §1.7).

The sum() has no reason to modify its argument. This immutability is indicated by declaring the vector argument const (§1.6), so the vector is passed by const-reference.

3.6.1 Argument Passing

First consider how to get values into a function. By default we copy (“pass-by-value”) and if we want to refer to an object in the caller’s environment, we use a reference (“pass-by-reference”). For example:

void test(vector<int> v, vector<int>& rv) // v is passed by value; rv is passed by reference

{

v[1] = 99; // modify v (a local variable)

rv[2] = 66; // modify whatever rv refers to

}

int main()

{

vector fib = {1,2,3,5,8,13,21};

test(fib,fib);

cout << fib[1] << '' << fib[2] << '\n'; // prints 2 66

}

When we care about performance, we usually pass small values by-value and larger ones by-reference. Here “small” means “something that’s really cheap to copy.” Exactly what “small” means depends on machine architecture, but “the size of two or three pointers or less” is a good rule of thumb.

If we want to pass by reference for performance reasons but don’t need to modify the argument, we pass-by-const-reference as in the sum() example. This is by far the most common case in ordinary good code: it is fast and not error-prone.

It is not uncommon for a function argument to have a default value; that is, a value that is considered preferred or just the most common. We can specify such a default by a default function argument. For example:

void print(int value, int base =10); // print value in base "base" print(x,16); // hexadecimal print(x,60); // sexagesimal (Sumerian) print(x); // use the dafault: decimal

This is a notationally simpler alternative to overloading:

void print(int value, int base); // print value in base "base"

void print(int value) // print value in base 10

{

print(value,10);

}

3.6.2 Value Return

Once we have computed a result, we need to get it out of the function and back to the caller. Again, the default for value return is to copy and for small objects that’s ideal. We return “by reference” only when we want to grant a caller access to something that is not local to the function. For example:

class Vector {

public:

// ...

double& operator[](int i) { return elem[i]; } // return reference to ith element

private:

double* elem; // elem points to an array of sz

// ...

};

The ith element of a Vector exists independently of the call of the subscript operator, so we can return a reference to it.

On the other hand, a local variable disappears when the function returns, so we should not return a pointer or reference to it:

int& bad()

{

int x;

// ...

return x; // bad: return a reference to the local variable x

}

Fortunately, all major C++ compilers will catch the obvious error in bad().

Returning a reference or a value of a “small” type is efficient, but how do we pass large amounts of information out of a function? Consider:

Matrix operator+(const Matrix& x, const Matrix& y)

{

Matrix res;

// ... for all res[i,j], res[i,j] = x[i,j]+y[i,j] ...

return res;

}

Matrix m1, m2;

// ...

Matrix m3 = m1+m2; // no copy

A Matrix may be very large and expensive to copy even on modern hardware. So we don’t copy, we give Matrix a move constructor (§5.2.2) and very cheaply move the Matrix out of operator+(). We do not need to regress to using manual memory management:

Matrix* add(const Matrix& x, const Matrix& y) // complicated and error-prone 20th century style

{

Matrix* p = new Matrix;

// ... for all *p[i,j], *p[i,j] = x[i,j]+y[i,j] ...

return p;

}

Matrix m1, m2;

// ...

Matrix* m3 = add(m1,m2); // just copy a pointer

// ...

delete m3; // easily forgotten

Unfortunately, returning large objects by returning a pointer to it is common in older code and a major source of hard-to-find errors. Don’t write such code. Note that operator+() is as efficient as add(), but far easier to define, easier to use, and less error-prone.

If a function cannot perform its required task, it can throw an exception (§3.5.1). This can help avoid code from being littered with error-code tests for “exceptional problems.”

The return type of a function can be deduced from its return value. For example:

auto mul(int i, double d) { return i*d; } // here, "auto" means "deduce the return type"

This can be convenient, especially for generic functions (function templates; §6.3.1) and lambdas (§6.3.3), but should be used carefully because a deduced type does not offer a stable interface: a change to the implementation of the function (or lambda) can change the type.

3.6.3 Structured Binding

A function can return only a single value, but that value can be a class object with many members. This allows us to efficiently return many values. For example:

struct Entry {

string name;

int value;

};

Entry read_entry(istream& is) // naive read function (for a better version, see §10.5)

{

string s;

int i;

is >> s >> i;

return {s,i};

}

auto e = read_entry(cin);

cout << "{ " << e.name << "," << e.value << " }\n";

Here, {s,i} is used to construct the Entry return value. Similarly, we can “unpack” an Entry’s members into local variables:

auto [n,v] = read_entry(is);

cout << "{ " << n << "," << v << " }\n";

The auto [n,v] declares two local variables n and v with their types deduced from read_entry()’s return type. This mechanism for giving local names to members of a class object is called structured binding.

Consider another example:

map<string,int> m;

// ... fill m ...

for (const auto [key,value] : m)

cout << "{" << key "," << value << "}\n";

As usual, we can decorate auto with const and &. For example:

void incr(map<string,int>& m) // increment the value of each element of m

{

for (auto& [key,value] : m)

++value;

}

When structured binding is used for a class with no private data, it is easy to see how the binding is done: there must be the same number of names defined for the binding as there are nonstatic data members of the class, and each name introduced in the binding names the corresponding member. There will not be any difference in the object code quality compared to explicitly using a composite object; the use of structured binding is all about how best to express an idea.

It is also possible to handle classes where access is through member functions. For example:

complex<double> z = {1,2};

auto [re,im] = z+2; // re=3; im=2

A complex has two data members, but its interface consists of access functions, such as real() and imag(). Mapping a complex<double> to two local variables, such as re and im is feasible and efficient, but the technique for doing so is beyond the scope of this book.

3.7 Advice

[1] Distinguish between declarations (used as interfaces) and definitions (used as implementations); §3.1.

[2] Use header files to represent interfaces and to emphasize logical structure; §3.2; [CG: SF.3].

[3] #include a header in the source file that implements its functions; §3.2; [CG: SF.5].

[4] Avoid non-inline function definitions in headers; §3.2; [CG: SF.2].

[5] Prefer modules over headers (where modules are supported); §3.3.

[6] Use namespaces to express logical structure; §3.4; [CG: SF.20].

[7] Use using-directives for transition, for foundational libraries (such as std), or within a local scope; §3.4; [CG: SF.6] [CG: SF.7].

[8] Don’t put a using-directive in a header file; §3.4; [CG: SF.7].

[9] Throw an exception to indicate that you cannot perform an assigned task; §3.5; [CG: E.2].

[10] Use exceptions for error handling only; §3.5.3; [CG: E.3].

[11] Use error codes when an immediate caller is expected to handle the error; §3.5.3.

[12] Throw an exception if the error is expected to percolate up through many function calls; §3.5.3.

[13] If in doubt whether to use an exception or an error code, prefer exceptions; §3.5.3.

[14] Develop an error-handling strategy early in a design; §3.5; [CG: E.12].

[15] Use purpose-designed user-defined types as exceptions (not built-in types); §3.5.1.

[16] Don’t try to catch every exception in every function; §3.5; [CG: E.7].

[17] Prefer RAII to explicit try-blocks; §3.5.1, §3.5.2; [CG: E.6].

[18] If your function may not throw, declare it noexcept; §3.5; [CG: E.12].

[19] Let a constructor establish an invariant, and throw if it cannot; §3.5.2; [CG: E.5].

[20] Design your error-handling strategy around invariants; §3.5.2; [CG: E.4].

[21] What can be checked at compile time is usually best checked at compile time; §3.5.5 [CG: P.4] [CG: P.5].

[22] Pass “small” values by value and “large“ values by references; §3.6.1; [CG: F.16].

[23] Prefer pass-by-const-reference over plain pass-by-reference; _module.arguments_; [CG: F.17].

[24] Return values as function-return values (rather than by out-parameters); §3.6.2; [CG: F.20] [CG: F.21].

[25] Don’t overuse return-type deduction; §3.6.2.

[26] Don’t overuse structured binding; using a named return type is often clearer documentation; §3.6.3.