12

Algorithms

Do not multiply entities beyond necessity.

– William Occam

12.1 Introduction

A data structure, such as a list or a vector, is not very useful on its own. To use one, we need operations for basic access such as adding and removing elements (as is provided for list and vector). Furthermore, we rarely just store objects in a container. We sort them, print them, extract subsets, remove elements, search for objects, etc. Consequently, the standard library provides the most common algorithms for containers in addition to providing the most common container types. For example, we can simply and efficiently sort a vector of Entrys and place a copy of each unique vector element on a list:

void f(vector<Entry>& vec, list<Entry>& lst)

{

sort(vec.begin(),vec.end()); // use < for order

unique_copy(vec.begin(),vec.end(),lst.begin()); // don't copy adjacent equal elements

}

For this to work, less than (<) and equal (==) must be defined for Entrys. For example:

bool operator<(const Entry& x, const Entry& y) // less than

{

return x.name<y.name; // order Entries by their names

}

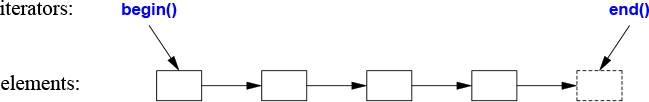

A standard algorithm is expressed in terms of (half-open) sequences of elements. A sequence is represented by a pair of iterators specifying the first element and the one-beyond-the-last element:

In the example, sort() sorts the sequence defined by the pair of iterators vec.begin() and vec.end(), which just happens to be all the elements of a vector. For writing (output), you need only to specify the first element to be written. If more than one element is written, the elements following that initial element will be overwritten. Thus, to avoid errors, lst must have at least as many elements as there are unique values in vec.

If we wanted to place the unique elements in a new container, we could have written:

list<Entry> f(vector<Entry>& vec)

{

list<Entry> res;

sort(vec.begin(),vec.end());

unique_copy(vec.begin(),vec.end(),back_inserter(res)); // append to res

return res;

}

The call back_inserter(res) constructs an iterator for res that adds elements at the end of a container, extending the container to make room for them. This saves us from first having to allocate a fixed amount of space and then filling it. Thus, the standard containers plus back_inserter()s eliminate the need to use error-prone, explicit C-style memory management using realloc(). The standard-library list has a move constructor (§5.2.2) that makes returning res by value efficient (even for lists of thousands of elements).

If you find the pair-of-iterators style of code, such as sort(vec.begin(),vec.end()), tedious, you can define container versions of the algorithms and write sort(vec) (§12.8).

12.2 Use of Iterators

For a container, a few iterators referring to useful elements can be obtained; begin() and end() are the best examples of this. In addition, many algorithms return iterators. For example, the standard algorithm find looks for a value in a sequence and returns an iterator to the element found:

bool has_c(const string& s, char c) // does s contain the character c?

{

auto p = find(s.begin(),s.end(),c);

if (p!=s.end())

return true;

else

return false;

}

Like many standard-library search algorithms, find returns end() to indicate “not found.” An equivalent, shorter, definition of has_c() is:

bool has_c(const string& s, char c) // does s contain the character c?

{

return find(s.begin(),s.end(),c)!=s.end();

}

A more interesting exercise would be to find the location of all occurrences of a character in a string. We can return the set of occurrences as a vector of string iterators. Returning a vector is efficient because vector provides move semantics (§5.2.1). Assuming that we would like to modify the locations found, we pass a non-const string:

vector<string::iterator> find_all(string& s, char c) // find all occurrences of c in s

{

vector<string::iterator> res;

for (auto p = s.begin(); p!=s.end(); ++p)

if (*p==c)

res.push_back(p);

return res;

}

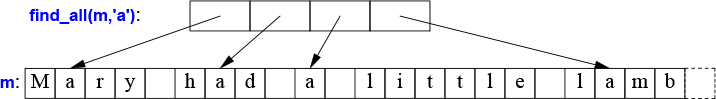

We iterate through the string using a conventional loop, moving the iterator p forward one element at a time using ++ and looking at the elements using the dereference operator *. We could test find_all() like this:

void test()

{

string m {"Mary had a little lamb"};

for (auto p : find_all(m,'a'))

if (*p!='a')

cerr << "a bug!\n";

}

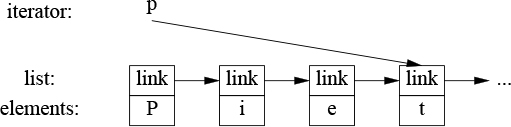

That call of find_all() could be graphically represented like this:

Iterators and standard algorithms work equivalently on every standard container for which their use makes sense. Consequently, we could generalize find_all():

template<typename C, typename V>

vector<typename C::iterator> find_all(C& c, V v) // find all occurrences of v in c

{

vector<typename C::iterator> res;

for (auto p = c.begin(); p!=c.end(); ++p)

if (*p==v)

res.push_back(p);

return res;

}

The typename is needed to inform the compiler that C’s iterator is supposed to be a type and not a value of some type, say, the integer 7. We can hide this implementation detail by introducing a type alias (§6.4.2) for Iterator:

template<typename T>

using Iterator = typename T::iterator; // T's iterator

template<typename C, typename V>

vector<Iterator<C>> find_all(C& c, V v) // find all occurrences of v in c

{

vector<Iterator<C>> res;

for (auto p = c.begin(); p!=c.end(); ++p)

if (*p==v)

res.push_back(p);

return res;

}

We can now write:

void test()

{

string m {"Mary had a little lamb"};

for (auto p : find_all(m,'a')) // p is a string::iterator

if (*p!='a')

cerr << "string bug!\n";

list<double> ld {1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 1.1};

for (auto p : find_all(ld,1.1)) // p is a list<double>::iterator

if (*p!=1.1)

cerr << "list bug!\n";

vector<string> vs { "red", "blue", "green", "green", "orange", "green" };

for (auto p : find_all(vs,"red")) // p is a vector<string>::iterator

if (*p!="red")

cerr << "vector bug!\n";

for (auto p : find_all(vs,"green"))

*p = "vert";

}

Iterators are used to separate algorithms and containers. An algorithm operates on its data through iterators and knows nothing about the container in which the elements are stored. Conversely, a container knows nothing about the algorithms operating on its elements; all it does is to supply iterators upon request (e.g., begin() and end()). This model of separation between data storage and algorithm delivers very general and flexible software.

12.3 Iterator Types

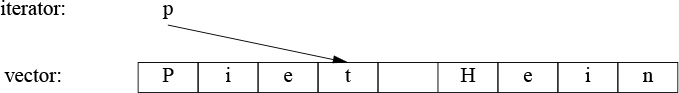

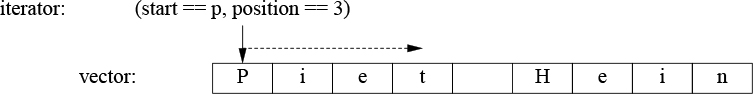

What are iterators really? Any particular iterator is an object of some type. There are, however, many different iterator types, because an iterator needs to hold the information necessary for doing its job for a particular container type. These iterator types can be as different as the containers and the specialized needs they serve. For example, a vector’s iterator could be an ordinary pointer, because a pointer is quite a reasonable way of referring to an element of a vector:

Alternatively, a vector iterator could be implemented as a pointer to the vector plus an index:

Using such an iterator would allow range checking.

A list iterator must be something more complicated than a simple pointer to an element because an element of a list in general does not know where the next element of that list is. Thus, a list iterator might be a pointer to a link:

What is common for all iterators is their semantics and the naming of their operations. For example, applying ++ to any iterator yields an iterator that refers to the next element. Similarly, * yields the element to which the iterator refers. In fact, any object that obeys a few simple rules like these is an iterator – Iterator is a concept (§7.2, §12.7). Furthermore, users rarely need to know the type of a specific iterator; each container “knows” its iterator types and makes them available under the conventional names iterator and const_iterator. For example, list<Entry>::iterator is the general iterator type for list<Entry>. We rarely have to worry about the details of how that type is defined.

12.4 Stream Iterators

Iterators are a general and useful concept for dealing with sequences of elements in containers. However, containers are not the only place where we find sequences of elements. For example, an input stream produces a sequence of values, and we write a sequence of values to an output stream. Consequently, the notion of iterators can be usefully applied to input and output.

To make an ostream_iterator, we need to specify which stream will be used and the type of objects written to it. For example:

ostream_iterator<string> oo {cout}; // write strings to cout

The effect of assigning to *oo is to write the assigned value to cout. For example:

int main()

{

*oo = "Hello, "; // meaning cout<<"Hello, "

++oo;

*oo = "world!\n"; // meaning cout<<"world!\n"

}

This is yet another way of writing the canonical message to standard output. The ++oo is done to mimic writing into an array through a pointer.

Similarly, an istream_iterator is something that allows us to treat an input stream as a read-only container. Again, we must specify the stream to be used and the type of values expected:

istream_iterator<string> ii {cin};

Input iterators are used in pairs representing a sequence, so we must provide an istream_iterator to indicate the end of input. This is the default istream_iterator:

istream_iterator<string> eos {};

Typically, istream_iterators and ostream_iterators are not used directly. Instead, they are provided as arguments to algorithms. For example, we can write a simple program to read a file, sort the words read, eliminate duplicates, and write the result to another file:

int main()

{

string from, to;

cin >> from >> to; // get source and target file names

ifstream is {from}; // input stream for file "from"

istream_iterator<string> ii {is}; // input iterator for stream

istream_iterator<string> eos {}; // input sentinel

ofstream os {to}; // output stream for file "to"

ostream_iterator<string> oo {os,"\n"}; // output iterator for stream

vector<string> b {ii,eos}; // b is a vector initialized from input

sort(b.begin(),b.end()); // sort the buffer

unique_copy(b.begin(),b.end(),oo); // copy buffer to output, discard replicated values

return !is.eof() || !os; // return error state (§1.2.1, §10.4)

}

An ifstream is an istream that can be attached to a file, and an ofstream is an ostream that can be attached to a file (§10.7). The ostream_iterator’s second argument is used to delimit output values.

Actually, this program is longer than it needs to be. We read the strings into a vector, then we sort() them, and then we write them out, eliminating duplicates. A more elegant solution is not to store duplicates at all. This can be done by keeping the strings in a set, which does not keep duplicates and keeps its elements in order (§11.4). That way, we could replace the two lines using a vector with one using a set and replace unique_copy() with the simpler copy():

set<string> b {ii,eos}; // collect strings from input

copy(b.begin(),b.end(),oo); // copy buffer to output

We used the names ii, eos, and oo only once, so we could further reduce the size of the program:

int main()

{

string from, to;

cin >> from >> to; // get source and target file names

ifstream is {from}; // input stream for file "from"

ofstream os {to}; // output stream for file "to"

set<string> b {istream_iterator<string>{is},istream_iterator<string>{}}; // read input

copy(b.begin(),b.end(),ostream_iterator<string>{os,"\n"}); // copy to output

return !is.eof() || !os; // return error state (§1.2.1, §10.4)

}

It is a matter of taste and experience whether or not this last simplification improves readability.

12.5 Predicates

In the examples so far, the algorithms have simply “built in” the action to be done for each element of a sequence. However, we often want to make that action a parameter to the algorithm. For example, the find algorithm (§12.2, §12.6) provides a convenient way of looking for a specific value. A more general variant looks for an element that fulfills a specified requirement, a predicate. For example, we might want to search a map for the first value larger than 42. A map allows us to access its elements as a sequence of (key,value) pairs, so we can search a map<string,int>’s sequence for a pair<const string,int> where the int is greater than 42:

void f(map<string,int>& m)

{

auto p = find_if(m.begin(),m.end(),Greater_than{42});

// ...

}

Here, Greater_than is a function object (§6.3.2) holding the value (42) to be compared against:

struct Greater_than {

int val;

Greater_than(int v) : val{v} { }

bool operator()(const pair<string,int>& r) const { return r.second>val; }

};

Alternatively, we could use a lambda expression (§6.3.2):

auto p = find_if(m.begin(), m.end(), [](const pair<string,int>& r) { return r.second>42; });

A predicate should not modify the elements to which it is applied.

12.6 Algorithm Overview

A general definition of an algorithm is “a finite set of rules which gives a sequence of operations for solving a specific set of problems [and] has five important features: Finiteness ... Definiteness ... Input ... Output ... Effectiveness” [Knuth,1968,§1.1]. In the context of the C++ standard library, an algorithm is a function template operating on sequences of elements.

The standard library provides dozens of algorithms. The algorithms are defined in namespace std and presented in the <algorithm> header. These standard-library algorithms all take sequences as inputs. A half-open sequence from b to e is referred to as [b:e). Here are a few examples:

Selected Standard Algorithms |

|

|

For each element |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Replace elements |

|

Replace elements |

|

Copy [ |

|

Copy elements |

|

Move [ |

|

Copy [ |

|

Sort elements of [ |

|

Sort elements of [ |

|

[ |

|

Merge two sorted sequences [ |

|

Merge two sorted sequences [ |

These algorithms, and many more (e.g., §14.3), can be applied to elements of containers, strings, and built-in arrays.

Some algorithms, such as replace() and sort(), modify element values, but no algorithm adds or subtracts elements of a container. The reason is that a sequence does not identify the container that holds the elements of the sequence. To add or delete elements, you need something that knows about the container (e.g., a back_inserter; §12.1) or directly refers to the container itself (e.g., push_back() or erase(); §11.2).

Lambdas are very common as operations passed as arguments. For example:

vector<int> v = {0,1,2,3,4,5};

for_each(v.begin(),v.end(),[](int& x){ x=x*x; }); // v=={0,1,4,9,16,25}

The standard-library algorithms tend to be more carefully designed, specified, and implemented than the average hand-crafted loop, so know them and use them in preference to code written in the bare language.

12.7 Concepts (C++20)

Eventually, the standard-library algorithms will be specified using concepts (Chapter 7). The preliminary work on this can be found in the Ranges Technical Specification [RangesTS]. Implementations can be found on the Web. The concepts are defined in <experimental/ranges>, but hopefully something very similar will be added to namespace std for C++20.

Ranges are a generalization of the C++98 sequences defined by begin()/end() pairs. A Range is a concept specifying what it takes to be a sequence of elements. It can be defined by

A

{begin,end}pair of iteratorsA

{begin,n}pair, wherebeginis an iterator andnis the number of elementsA

{begin,pred}pair, wherebeginis an iterator andpredis a predicate; ifpred(p)istruefor the iteratorp, we have reached the end of the sequence. This allows us to have infinite sequences and sequences that are generated “on the fly.”

This Range concept is what allows us to say sort(v) rather than sort(v.begin(),v.end()) as we had to using the STL since 1994. For example:

template<BoundedRangeR>

requires Sortable<R>

void sort(R& r)

{

return sort(begin(r),end(r));

}

The relation for Sortable is defaulted to less.

In addition to Range, the Ranges TS offers many useful concepts. These concepts are found in <experimental/ranges/concepts>. For precise definitions, see [RangesTS].

Core language concepts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

A |

|

|

Common is important for specifying algorithms that should work with a variety of related types while still being mathematically sound. Common<T,U> is a type C that we can use for comparing a T with a U by first converting both to Cs. For example, we would like to compare a std::string with a C-style string (a char*) and an int with a double, but not a std::string with an int. To ensure that we specialize common_type_t, used in the definition of Common, suitably:

using common_type_t<std::string,char*> = std::string; using common_type_t<double,int> = double;

The definition of Common is a bit tricky but solves a hard fundamental problem. Fortunately, we don’t need to define a common_type_t specialization unless we want to use operations on mixes of types for which a library doesn’t (yet) have suitable definitions. Common or CommonReference is used in the definitions of most concepts and algorithms that can compare values of different types.

The concepts related to comparison are strongly influenced by [Stepanov,2009].

Comparison concepts |

|

|

A |

|

A |

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

A |

|

|

The use of both WeaklyEqualityComparableWith and WeaklyEqualityComparable shows a (so far) missed opportunity to overload.

Object concepts |

|

|

A |

|

A |

|

A |

|

A |

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Regular is the ideal for types. A Regular type works roughly like an int and simplifies much of our thinking about how to use a type (§7.2). The lack of default == for classes means that most classes start out as SemiRegular even though most could and should be Regular.

Callable concepts |

|

|

An |

|

|

|

An |

|

|

|

A |

A function f() is equality preserving if x==y implies that f(x)==f(y).

Strict weak ordering is what the standard library usually assumes for comparisons, such as <; look it up if you feel the need to know.

Relation and StrictWeakOrder differ only in semantics. We can’t (currently) represent that in code so the names simply express our intent.

Iterator concepts |

|

|

An |

|

An that is, |

|

A sentinel |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

Can merge sorted sequences defined by |

|

Can sort sequences defined by |

|

Can sort sequences defined by |

The different kinds (categories) of iterators are used to select the best algorithm for a given algorithm; see §7.2.2 and §13.9.1. For an example of an InputIterator, see §12.4.

The basic idea of a sentinel is that we can iterate over a range starting at an iterator until the predicate becomes true for an element. That way, an iterator p and a sentinel s define a range [p:s(*p)). For example, we could define a predicate for a sentinel for traversing a C-style string using a pointer as the iterator:

[](const char* p) {return *p==0; }

The summary of Mergeable and Sortable are simplified relative to [RangesTS].

Range concepts |

|

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

|

An |

There are a few more concepts in [RangesTS], but this set is a good start.

12.8 Container Algorithms

When we can’t wait for Ranges, we can define our own simple range algorithms. For example, we can easily provide the shorthand to say just sort(v) instead of sort(v.begin(),v.end()):

namespace Estd {

using namespace std;

template<typename C>

void sort(C& c)

{

sort(c.begin(),c.end());

}

template<typename C, typename Pred>

void sort(C& c, Pred p)

{

sort(c.begin(),c.end(),p);

}

// ...

}

I put the container versions of sort() (and other algorithms) into their own namespace Estd (“extended std”) to avoid interfering with other programmers’ uses of namespace std and also to make it easier to replace this stopgap with Ranges.

12.9 Parallel Algorithms

When the same task is to be done to many data items, we can execute it in parallel on each data item provided the computations on different data items are independent:

parallel execution: tasks are done on multiple threads (often running on several processor cores)

vectorized execution: tasks are done on a single thread using vectorization, also known as SIMD (“Single Instruction, Multiple Data”).

The standard library offers support for both and we can be specific about wanting sequential execution; in <execution>, we find:

seq: sequential executionpar: parallel execution (if feasible)par_unseq: parallel and/or unsequenced (vectorized) execution (if feasible).

Consider std::sort():

sort(v.begin(),v.end()); // sequential sort(seq,v.begin(),v.end()); // sequential (same as the default) sort(par,v.begin(),v.end()); // parallel sort(par_unseq,v.begin(),v.end()); // parallel and/or vectorized

Whether it is worthwhile to parallelize and/or vectorize depends on the algorithm, the number of elements in the sequence, the hardware, and the utilization of that hardware by programs running on it. Consequently, the execution policy indicators are just hints. A compiler and/or run-time scheduler will decide how much concurrency to use. This is all nontrivial and the rule against making statements about efficiency without measurement is very important here.

Most standard-library algorithms, including all in the table in §12.6 except equal_range, can be requested to be parallelized and vectorized using par and par_unseq as for sort(). Why not equal_range()? Because so far nobody has come up with a worthwhile parallel algorithm for that.

Many parallel algorithms are used primarily for numeric data; see §14.3.1.

When requesting parallel execution, be sure to avoid data races (§15.2) and deadlock (§15.5).

12.10 Advice

[1] An STL algorithm operates on one or more sequences; §12.1.

[2] An input sequence is half-open and defined by a pair of iterators; §12.1.

[3] When searching, an algorithm usually returns the end of the input sequence to indicate “not found”; §12.2.

[4] Algorithms do not directly add or subtract elements from their argument sequences; §12.2, §12.6.

[5] When writing a loop, consider whether it could be expressed as a general algorithm; §12.2.

[6] Use predicates and other function objects to give standard algorithms a wider range of meanings; §12.5, §12.6.

[7] A predicate must not modify its argument; §12.5.

[8] Know your standard-library algorithms and prefer them to hand-crafted loops; §12.6.

[9] When the pair-of-iterators style becomes tedious, introduce a container/range algorithm; §12.8.