CHAPTER 9

HOST-BASED INTRUSION PREVENTION

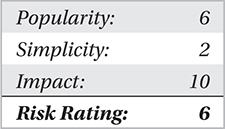

Simply put, a host-based intrusion prevention system (HIPS) is a host-based application that monitors the local operating system and installed applications in order to protect against unauthorized executions and/or launching of malicious processes on the local host, whereas a network intrusion prevention system (NIPS), although it behaves similarly, is designed to protect a network rather than an individual host. Intrusion prevention systems monitor system activities for specific malicious behaviors in real time and then attempt to block and/or prevent those processes from executing. A HIPS system is generally implemented to protect critical enterprise servers and user workstations from real-time mobile code outbreaks across a network that typically exploit the trusts generated when running within an enterprise.

HIPS Architectures

A HIPS will typically be one of several components within an enterprise that provide intrusion detection and intrusion prevention. Numerous vendors supply “cradle-to-grave” or “encompassing” IDS/IPS solutions that plug right into enterprise networks. Here are some of the components you’ll generally find paired with host-based intrusion prevention systems:

• Security information and event management server (SIEM) This is the common name for a security system infrastructure management server. SIEMs typically leverage information from additional enterprise security devices rather than simply from an IDS/IPS system. SIEMs allow you to receive security information from systems such as firewalls, servers, antivirus, and many other logs to give you a clear analytical view of the network.

• Host-based intrusion detection system (HIDS) This is a passive IDS that monitors a local computer’s ingress and egress communications and applications. This type of IDS will only detect and will not attempt to deny or prevent a suspicious action, versus a HIPS, which will attempt to deny or prevent the intrusion.

• Network intrusion detection system (NIDS) This passive form of IDS monitors the network and alerts on suspicious activity. The alerting mechanisms or methods are based solely on the type or family of intrusion detection (behavior or signature) system you have.

• Network intrusion prevention system (NIPS) This active form of intrusion detection identifies suspicious activity and denies network access, thereby preventing attacks and propagation of malware.

Following are a few simple diagrams illustrating common architectures where HIPS can be used and explaining how it can complement the rest of your intrusion detection network to best prevent malware outbreaks.

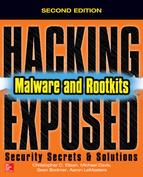

Workstation Perspective Figure 9-1 shows the placement of host intrusion prevention systems on all of the workstations, providing preventive protection.

Figure 9-1 Server IDS, network IPS, and workstation-based IPS architecture

Network Perspective When using intrusion prevention systems in a network, you typically separate the user and server segments in order to identify quickly which side of your network is hemorrhaging from a recent malware infection. You can separate the network between any two segments. This method is useful when trying to prevent malware propagation.

Server Perspective Throughout the server segment in Figure 9-1, you see a mixed HIDS and HIPS breakout. Some operational stakeholders want passive intrusion detection on critical systems so daily business operations are not impacted. This is the cautious business approach, as applications can sometimes generate unexpected behaviors and accidently deny access to critical applications.

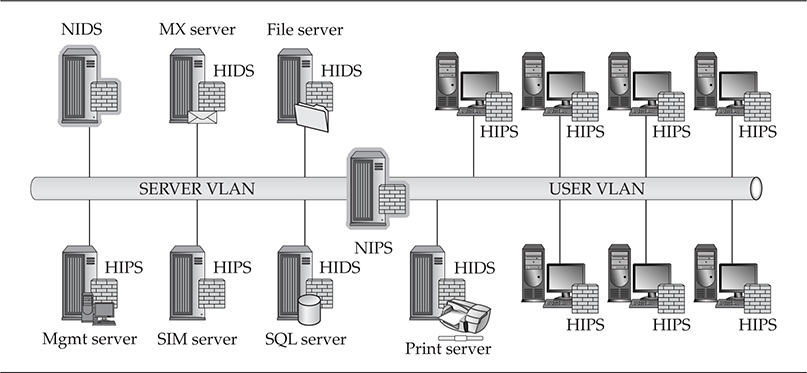

Workstation Perspective Figure 9-2 also shows the placement of HIPS on all the workstations, providing preventive protection. As also shown in Figure 9-1, this approach is very solid defense-in-depth when fighting malware.

Figure 9-2 Network- and host-based mixed IPS and IDS architecture

Network Perspective In Figure 9-2, a passive intrusion detection method is being implemented across both network segments. This setup can detect malware, but it will do absolutely nothing when it comes to denying access to malware executing across the network.

Server Perspective Throughout the server segment in Figure 9-2, you again see a mixed HIDS and HIPS breakdown. Almost every network we’ve come across has some level of a mixed HIDS and HIPS server farm due to the industry superstition regarding intrusion prevention systems between major network segments and their sometimes questionable actions when access to information is severed due to the IPS shutting down a connection. Because this superstition can sometimes come true, management stakeholders do have cause to be nervous when it comes to HIPS on critical systems.

A combination of HIDS and HIPS is also good practice when it comes to defending against known and zero-day exploit attacks.

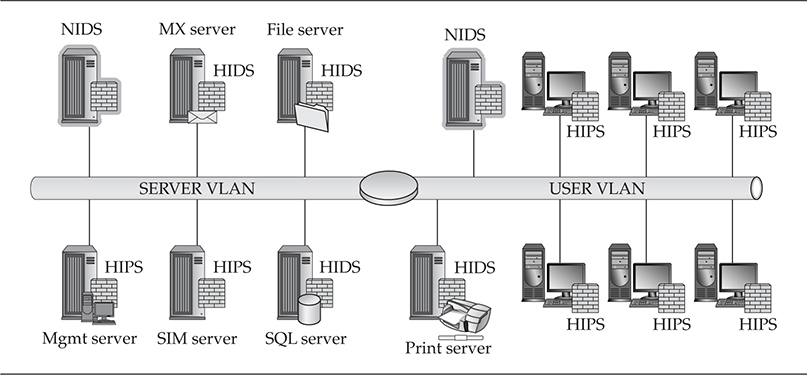

Workstation Perspective In Figure 9-3, HIPS are also placed on all of the workstations, which provides preventive protection. Overall, this is the recommended setup when implementing HIPS on your network. These are the first network components that have the highest likelihood of becoming infected.

Figure 9-3 Network- and host-based IPS architecture

Network Perspective You can only use this approach with higher-end NIPS that have more than a single set of LAN interfaces that could be used between each network segment. With this method, building redundancy into these configurations when a single device is holding the fate of network continuity in its hands is a good idea.

Server Perspective The configuration shown in Figure 9-3 is useful when you cannot take any chances and security is far more important than operations. When it comes to stopping malware propagation through your server as soon as possible, deploy this type of server protection.

Growing Past Intrusion Detection

The forerunner of intrusion prevention technology was intrusion detection in which static signature sets were implemented in order to identify unwanted and/or malicious traffic on a network or host. An IPS has several advantages over an IDS, specifically where the IPS is designed to sit inline with traffic flows to prevent an attack rather than idle on a wire to simply issue an alarm when an event occurs that may or may not be noticed by security staff. Most IPSs can also inspect and decode network packets up to layer 7 (the Application layer), providing a much deeper insight into the actual content of data crossing your network, which is where the attacks hide today. Packet decoding is the process of taking binary data and passing it through an engine that decodes the data into a human-readable form. In the analysis phase of packet inspection, an analyst will review the information in decoded packets in an attempt to validate network activity that has been detected and is visible.

Encrypted network traffic that has been detected cannot be analyzed because of the encryption—another example of a covert channel. The encryption process that does occur to secure the traffic is handled between two hosts and a traditional IDS, but this process is not capable of intercepting the session keys, which are needed to decrypt the stream. However, if an inline IPS were in place when the encrypted stream passed through, the IPS could handle and process every packet, see the content of the stream, and also pass that decoded stream to vulnerability and exploit analysis modules for deeper packet inspection.

A HIPS is stronger in several ways because it doesn’t require the normal updating mechanisms that most signature-based security products require, as its goal is to identify malware behavior upon execution. A HIPS will identify the methods in which malware will modify system states in order to execute its intended design rather than rely on a single signature to identify an attack vector (as an IDS would). If configured to do so, a HIPS is able to monitor changes made by running processes that are executed by the system or user, and it generally has a default mode that provides a “standard” level of coverage. However, as each network differs in some way, every primary policy for your enterprise needs to have its own “custom” policy.

A more reliable HIPS comes with anti-rootkit modules that perform checks against every possible method in which control of the system kernel could be quietly assumed and used to gain control of the host operating system. Unlike traditional signature-based systems that can be subverted by simply defeating the signature-based engine, a HIPS looks for the actual methods in which applications function. There are numerous cyber-underground malware-testing sites that function similarly to VirusTotal.com. These sites enable malware writers to circumvent signature-based engines and are also helpful in testing the accuracy of antivirus signatures. Their Robin Hood approach is brilliant in working for the greater good. They are able to receive uploads of various binary files and then analyze the uploaded files in order to baseline all major antivirus signatures. Once the uploader (malware writer) finishes the analysis report and determines that his or her build is undetected by a large enough grouping of antivirus engines, the uploader, if he or she distributes the malicious code, now becomes a criminal. A HIPS, whether signature (rule) based or behavioral based, can be set in passive or active mode and has the ability to capture encrypted traffic if desired.

Behavioral vs. Signature

A HIPS can be either behavioral (policy or expert system based), signature ruleset based, or a combination of both. A policy-based HIPS generally uses a clearly defined set of rules about what is approved or unapproved behavior for an application and will notify the user of a potentially malicious activity and request the user either “allow” or “block” the action. Expert systems are much more complicated as they’re designed with a superset of rules that are scored and rated each time an action occurs and then a decision is made on behalf of the user, which can be followed by a prompt requesting the user approve whether it should “allow” or “block” the action.

Finally, a HIPS can be configured so an administrator isn’t required to be involved. The system can be configured to decide to allow or block based on network behavior training (tuning). This configuration can come with some headaches, but if you stick with it and properly tune the HIPS system, the payoffs are enormous.

After the user makes this decision, the expert system will actually learn from that user’s decision and then make a new rule referencing this event. In the end, this approach to a HIPS implementation is best, as the system overall can deduce itself whether a registry entry in HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run was added by malware. This approach with expert-based systems has proven to generate fewer false positives. When false positives do occur, however, the event is generally severe enough that most administrators will remember the pain for some time to come. False positives can lead to the loss of trust in a system that takes away resources from daily operations to investigate nothing.

Not common with signature-based scanners, which are mostly focused on dynamic code analysis, a behavioral-based HIPS focuses on detecting and blocking generic malicious behaviors and events as they are executed. Behavioral systems look for various flags and/or types of actions such as file/system modifications, unknown application/script startups, unknown applications registering to auto-start, Dynamic Link Library (DLL) injections, process/thread modifications, and layered service provider (LSP) installations. Focusing on these areas is a very strong approach to security because there are infinite ways to write code in order to evade the standard signature sets released by signature-based tools and only a limited range of ways in which malicious code can behave. Let’s look under the hood of each approach and try to decide which provides stronger protection against malware…

Behavioral Based

There is a huge difference between behavioral- and signature-based security applications, and the end result also varies significantly. The overall issue with both is embedded in the detection method; behavioral security uses pattern mappings of known applications, whereas signature security leverages known patterns of identified malware execution processes. This process is quite adequate at detecting anomalous behavior in trusted or rogue applications after they’ve been running for quite some time. Even today, some of the default behavioral-based engines perform quite well when malware is attempting to write or execute on a protected host.

The weakness of behavioral-based detection systems is their reliance on the end user or enterprise security administrator to understand and identify the malware’s behavior. The strengths of behavioral-based systems—the focus areas mentioned in the previous section—are also standard in most legitimate applications. Understanding which event is good or bad can quickly become an arduous process for users who typically get frustrated with the limitless alarms and may eventually turn off the system itself. Thankfully most behavioral systems have a whitelist and blacklist of default, known, and authorized applications and are generally updated across an enterprise or through a generally available update service.

A weakness of behavioral systems is their inability to identify malware unless it actually executes and performs the actions it registers as being malicious. Therefore, damage could already have been done even though the behavioral system has identified the malicious behavior. More than one type of behavioral-based identification system leverages expert systems and heuristics, which work by using a rule base with associated severity weights. Finally, an inherent weakness of behavioral-based systems is their inability to sometimes identify malware once it’s introduced into a system, as the behavioral engine is searching for malware behaviors versus signatures, which can be detected quickly if there is an available signature that identifies the malware. As long as the malware is inactive, it will not be detected by a behavioral system, but upon execution, it will be detected based on its behavior.

We cannot forget the anomaly-based detection system, which is generally used on business networks that are still rule based in nature. Simply put, the inherent rules are defined to detect specific types of traffic pattern behaviors. Adversaries can develop malware that evades detection by knowing which rules may be installed “by default” and/or are “generally accepted security practices,” again using the information security industry’s best practices against us. These hybrid systems are called either anomaly-based intrusion detection or intrusion detection/prevention systems (IDPSs). There are downfalls to relying solely on behavioral-based systems, although the systems provide many strong benefits. Keep in mind that behavioral-based systems are only as good as their policies. Out-of-the-box defaults are not precise enough for any one network so customizing policies is important.

Signature Based

Most in the security community have at one time or another had something negative to say about signature-based intrusion detection systems. These systems do have well-known weaknesses, but they also have strengths. Their primary strength lies in their ability to exactly identify well-known attack methods and malware with a single signature by labeling a specific segment of code or data within a file. Signature-based scanners can also identify malware when the specific predefined signature is identified. The signature engine is the easiest to implement and manage due to the standard signature update services that are typically available for any open source or commercially available malware detection system. Signature-based engines rely on partial, exact, or hybrid matching in order to identify malware; for example, the system could identify a filename, SHA, or MD5 hash, which it can then match to the malware itself. Signature-based systems are also mostly faster when it comes to performance and throughput.

That said, signature-based intrusion detection systems do have a common weakness—not being able to detect anything for which the system doesn’t have a loaded signature. A related issue is that slight variants of well-known attacks and malware signatures cannot be effectively identified. Attackers can modify existing malware easily using countless methods to simply bypass publicly and/or privately available signature sets. Here are some methods used:

• Altering strings, for instance, text within code such as simple strings, code comments, or printed strings that are not altered as far as functionality

• Hex editing

• Implementing packers that are known to be unsupported by the victim’s IDS vendor

• Implementing an alternative delivery method for the same attack

• Methods in which an elegant technique can “alter the signature” identified by IDS vendors

• Custom-developing malware that is, for the most part, widely undetectable until after the first several releases

Malware writers can test their latest device of destruction’s ability to be detected by security signatures at various sites such as VirusTotal.com and viruscan.jotti.org. These sites are great for the security community to use as well in order to identify and test a malware sample. The downside is they can also be used against the security community. Your malware sample may be tested against IDS or IPS signatures as well as antivirus signatures, depending on which site you use.

Finally signature-based engines can only be aware of attack methods postmortem or after they’ve been made public because a signature can’t be produced before then. These signature updates are typically distributed once every week, which never does anyone any good, seeing as a new worm can spread across the globe in a matter of hours. As per the earlier section, “HIPS Architectures,” these types of security systems are only as good as their configurations and their placement within the network.

Anti-Detection Evasion Techniques

IPS systems have unbelievably high effectiveness rates since they are inline and do not have to simply interpret network stacks. Intrusion prevention systems can easily clean up TCP flags and transport information being passed in sessions—information that you may want to ensure is stripped out to better protect your internal systems. Information to strip includes operating system, application versions, and/or specific internal protocol settings. An IPS can also correct cyclic redundancy checks as well as unfragment packets and TCP sequencing methods that can be used to trick other network security devices, such as intrusion detection systems and firewalls. Most importantly, IPSs are not vulnerable to the multitude of IDS-evasion techniques currently available. We’ll quickly highlight some of the popular evasion techniques in the IDS arena. These techniques illustrate the ways in which someone with malicious intent can bypass network detection and remain hidden from the security monitoring staff.

Basic String Matching Weaknesses

Basic String Matching Weaknesses

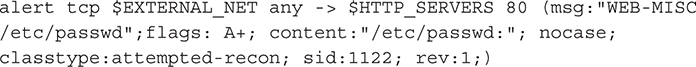

This method is the simplest one to use for evading an intrusion detection system without raising the suspicions of an ever-vigilant security administrator. Almost all intrusion detection systems rely heavily on basic string matching. The following IDS signature is an example of a very early SNORT signature, which is the de-facto standard for most signature-based systems:

Here, you could easily bypass etc/passwd by changing it to /etc/rc.d/../.\passwd, which is really the same exact path as /etc/passwd; you’re just moving the directories up and down. The basic failure with exact string matching is that minute changes can be made to so many strings that you’ll almost always have to generate a signature for each variant. And using regular expressions (REGEX) can increase the system load by requiring that the system attempt to identify the difference between a valid string and a malicious one.

Polymorphic Shellcode

Polymorphic Shellcode

This method, which is much newer and based on previous malware evasion techniques, is limited in nature to injection vectors (buffer overflows). Standard IDS signature detection relies on network traffic analysis, protocol analysis, and signature matching, which this circumvents. Polymorphic shellcode was developed by K2 with the release of ADMmutate. ADMmutate is a tool developed to obfuscate the detection of NOP sled and shellcode:

• NOP sled By far the oldest and most favored technique for executing a buffer overflow against a memory stack

• Shellcode A piece of code that is delivered as a payload used to open a reverse command shell so the attacker can remotely control a victim’s system

IDS systems typically trigger on NOP sled and shellcode signatures. ADMmutate allows an attacker to send an attack across a network and have it look different enough each time that it cannot be easily detected via an NIDS.

Session Splicing

Session Splicing

This method is a low-level anti-IDS technique used to splice data that would typically be sent in one packet to avoid detection. For example, GET / HTTP/1.0 could be split into several packets, G, ET, /, HT, TP, /, 1, .0. Using this method, a malware writer could circumvent a NIDS. This method is very easy to execute against HTTP-based sessions as they are plaintext and can be executed against SQL queries as well.

Fragmentation Attacks

Fragmentation Attacks

This method is implemented by breaking down an IP datagram into smaller packets so it can be transmitted over different network channels or media; the victim then reassembles the packets. Only in the past few years have NIDS had the ability to include some form of packet reassembly and comparison. The issue surrounding packet reassembly is the immense overhead the NIDS requires to store enough packets to identify, which need to be reassembled while continuing to monitor the rest of the network and reassemble every session it sees. Reassembly could quickly bring down a NIDS in terms of performance or cause it to crash from the overload.

Denial of Service

Denial of Service

This form of evasion can be used in two ways, either against the device and/or against the operator managing that device. Tools available to perform denial of service (DoS) against a NIDS include Stick, Snot, and several other tools you can find on the Internet. The most common goals of executing an IDS evasion using DoS techniques are to

• Introduce such an exorbitant amount of traffic-triggering signatures that the NIDS manager can’t possibly identify which attacks are true and/or which are false positives

• Introduce so much log information that the physical storage resources are completely consumed, preventing the NIDS from recording any more network events

• Introduce enough data onto the network that the device’s processing resources are consumed and the NIDS is unable to see any other network sessions

• Induce software or hardware failure on the NIDS in order to lock it up completely until a reboot can occur

Countermeasure: Combine NIPS with HIPS

Countermeasure: Combine NIPS with HIPS

A great approach toward a defense-in-depth strategy is to deploy a combination of NIPS devices with HIPS hosts across your enterprise. By combining these devices and hosts and setting up central reporting for your network security devices (firewalls, IDS, content filtering and management, and so on), you can increase network protection levels and help augment your response times due to these devices’ protection/blocking capabilities. Although a HIPS is strong from the sheer fact that it can evenly analyze encrypted and unencrypted traffic, the host operating system’s encryption/decryption process allows the HIPS to see the entire session. Having the ability to see into the session level gives you much more control at the point where modern attacks start—as client-based exploits. The one drawback to a HIPS is its obtuse view of network events, as it only sees traffic destined for its own IP address. Implementing a central management system so security administrators are able to correlate events across the network addresses this weakness.

A NIPS is good for blocking and protecting against traffic across an entire network. It can see various network events such as host scanning and malware propagation. When a NIPS sees this activity, it can block the traffic and protect the rest of your network from being compromised while also alerting you to the attack. An IDS would simply sit there on the sidelines and “perhaps” warn you of the event if it can detect it. However, there are disadvantages to a NIPS; it is an inline device and could be attacked in such a way that it’s shut down, essentially blocking all traffic going over that wire. Also important to note is that a NIDS or NIPS cannot see attacks at the operating system level like a HIPS can; therefore, combining these systems so they work together from a management and event-correlation perspective is important.

The different data outputs of the various technologies can be overwhelming to a network administrator. It is important to have a very succinct and holistic view of what is going on in a network. Security information and event management (SIEM) solutions give a network administrator meaningful information by combining different security events and security information from these technologies.

IPS Evasion Techniques

IPS Evasion Techniques

At the beginning of this section, we mentioned that IPSs are not vulnerable to the multitude of IDS-evasion techniques that are currently available, but IPSs are not perfect. In 2013, Michael Dyrmose wrote a paper on how to beat an IPS. In his abstract, he stated that manipulating the header, payload, and traffic flow of a well-known attack makes it possible to trick the IPS inspection engines into passing the traffic, allowing the attacker shell access to the target system protected by the IPS. You can read more about his work at https://www.sans.org/reading-room/whitepapers/intrusion/beating-ips-34137.

The principle applied here is the same principle applied to masking malware to evade detection systems. Attackers understand what enables the security product to identify the threat so they modify those variables or their characteristics to fool the security product into believing nothing malicious is passing through.

How Do You Detect Intent?

The ability to answer this question has been the “golden nugget” for enterprise security products for many years. The only means by which the security industry has really been able to identify intent has been through post mortem analysis of malware after infection. Identifying intent “post” infection is not where we need to be as an industry. Detecting the intent of malware goes beyond simply analyzing the immediate functions of the malware itself; this is simply the first stage of the intent identification process.

The ability to identify whether an action is actually user driven or a user-driven feature (user intent) is a difficult task. With the operating systems, applications, and background services available, not producing numerous false positives is difficult. Given these challenges, identifying malware intent is extremely difficult. Applications are unable to separate out user-driven actions from malware-driven actions, as most common applications share background features that perform similar tasks. On some occasions, network requests, file access requests, or systems calls are the same whether from user-driven applications or malware. To identify intent, ask these questions:

• How do you detect malware intent—upon or through execution?

• What actions are usable in an inference model to identify intent?

• What tools or methods can you use to detect intent?

Here are some simple concepts for identifying or inferring the differences between a user action and a malware action:

• A user launches a web browser (Microsoft Edge, Firefox, Chrome, etc.) from a shortcut that calls that browser through the explorer.exe process. From this perspective, you can infer this is user-initiated behavior as opposed to a direct application call.

• A system identifies whether a network IP was contacted through a direct network call and/or through a process initiated by the user. For instance, was an HTTP connection to www.facebook.com/maliciousprofile generated through a mouse click from within the browser process or from a process not associated with the web browser?

The important items to note are the mouse- or user-initiated activities and the process behaviors associated with those activities. With malware, direct process requests typically bypass the need to actually run within a trusted process. There are some attack tools available, however, that can be used to inject the malware directly into a process to avoid detection.

One such tool, Meterpreter, is a plug-in for the Metasploit framework. Meterpreter is able to avoid detection by not creating a new process in the process table, which is typically a dead giveaway for malware or host intrusion. Meterpreter actually injects an additional thread within the process it exploited initially, typically a system-level service. This way it avoids having to use chroot (a Unix command to change permissions on files) or alter any permissions for a process that might trigger the HIPS. This example is just one of a set of tools that can be used to bypass detection.

Malware intent can also be detected by analyzing the output or end result of each malware action. To do this, the host must allow the malware to run or to run in a virtual sandbox on the system so it can’t do any harm. A virtual sandbox is designed so an unknown or untrusted program can be run in an isolated environment without access to the computer’s files, the network, and/or system settings. Tools such as ThreatAnalyzer (which can be purchased from http://www.threattracksecurity.com/Sandbox) allow security analysts to run suspected malware from within a virtual sandbox to determine whether the file is malicious and to test files for known malicious content or behavior.

Virtual sandboxes have made such gargantuan leaps when it comes to speed and performance that they are now fast enough to be used inline in IPS technologies. As long as files can be intercepted, they can be pushed through the sandbox and wait until the verdict is rendered to either allow or block the file.

Allowing the malware to execute for analysis purposes lets you determine the malware’s functionality and how that functionality was configured. Identity theft, data theft, fraud, or just propagation could be inferred end goals; knowing this helps you better understand the intent of the malware. You can then better understand the threats to the enterprise, and your security team will be able to place protections in the right locations.

HIPS and the Future of Security

Since the turn of the century, antivirus firms have slowly lost more and more of their ability to detect malware variants and home-brewed goodies. Now, however, antivirus firms are slowly incorporating HIPS-based modules into their products.

HIPS products themselves are not the silver bullet that will defend your network against all threats, however; HIPS products are another tool to use to defend your network. They can operate in both active defense (blocking) mode and passive (simply issuing alarms and reporting) mode, but they can also identify and block the actual attack rather than just sit idle and issue an alarm like a NIDS. As enterprises grow considerably and budgets become tighter, augmenting personnel with IPS solutions has become more cost effective. We’re in no way stating that an IPS solution can replace a security engineer, as humans will always have to validate an automated system’s policies, actions, and output. Security engineers will also need to intervene in order to identify, analyze, collect evidence, and validate real attacks and operate and maintain security systems.

The best part about an IPS solution is that you can layer it anywhere within your network:

• You can deploy an IPS solution between your client and server segments using an active defense mode, which protects your servers, key corporate services, and data from your users (as users are the bane of every administrator’s existence).

• You can deploy one NIPS for your entire server LAN or deploy a HIPS on each server. Either solution would work; which you choose depends on your budget and how paranoid you are that a NIPS will accidentally block users from key services.

• You can deploy an IPS solution between your web server and the Internet. With this approach, you would have an inline defense (veritably invisible to adversaries), which in active defense mode could protect your web applications—the most frequently attacked systems on the Internet (typically attacked via SQL injection and XSS).

Today network- and host-based security applications have converged with regard to functionality. Firewall, antivirus, application defense, content management, and intrusion prevention technologies are combined to form a more unified security solution. Solutions that offer a hybrid of the core security technologies will overtake all of the independent solutions in several years; today vendors are creating fused solutions that package an entire suite of security solutions into one offering. And there are numerous vendors that can provide the intrusion prevention services you’re looking for. In 2004, Gartner declared the “IDS is dead, long live IPS,” creating the IPS buzz, which has been steadily getting louder ever since. However, IDS is still very much around because without it, it would be hard to secure an endpoint. Take, for example, most backdoors, RATs (remote access tools), and Trojans used by attackers. IDS solutions can still detect the majority of these malware classes and families. An IDS is still a good complement to other security solutions that are used to protect the network and each of the endpoints connected to it.

Summary

You should implement an IPS solution into your enterprise architecture if you want to prevent a malware outbreak. Our recommendation is to deploy inline NIPS between your critical or operational server segment and client network segments and between the Internet and your web demilitarized zone, or DMZ. Deploying sturdy HIPS onto your client workstations can also dramatically increase your overall security posture when trying to protect your enterprise from malware. It is always important to evaluate the corporate assets within your enterprise no matter what role those assets play in order to deploy host- and network-based protections properly and provide the best coverage for your enterprise.