CHAPTER 7

ANTIVIRUS

Antivirus (AV) is a necessity in every computer system. When you purchase a computer at a major retail store or on a website, an AV solution usually comes bundled with the system or is offered at a discounted rate. The computer security policies of federal government and private industry alike now largely require that AV be present on any system that connects to their network. Home users look to AV software to protect their system and data from malicious viruses, worms, Trojans, spyware, adware, and a host of other Internet-based threats. This situation has been going on for a very long time and is obviously good business for the AV companies—but is it good for the consumer? Does AV technology really work? How does it work and is it sustainable?

In this chapter, we’ll present the facts about the features and techniques common to nearly all AV software on the market today. Then, we’ll take a critical look at the debate about the usefulness of AV technology and how the industry has fought for its survival in recent years.

The terms antivirus and anti-malware are used interchangeably in the industry. Anti-malware has become a catchall solution to all malware threats, but it is still acceptable to use the term antivirus since it has been in the parlance of the security industry from the beginning and is understood as being synonymous with anti-malware, the newer term.

Now and Then: The Evolution of Antivirus Technology

Malware has a sordid and lengthy history. It has evolved from a simple file-infecting virus to the deadlier advance malware threats we see quite often today. This evolution of malware technology has pushed antivirus technology to evolve as well. This cat-and-mouse game is a familiar one, which we’ve also seen in the struggle between rootkit authors and anti-rootkit technology: advances in one technology force advancements in the other, resulting in an endless cycle of one-ups.

To set the context, the cat-and-mouse game in the AV world started in the late 1980s with simple file viruses that infected computer programs on disk. Viruses were transmitted via removable media such as floppy diskettes. At the time, simple antivirus applications checked for the presence of these malicious files on disk and removed them. Out of this concept arose one of the industry giants: Norton. And thus the AV industry was born.

To counter the growing detection industry, virus authors utilized more advanced infection and transmission methods. The Internet’s rise in the mid-1990s was the perfect incubation and breeding ground for such viruses, and soon transmission capabilities became literally unbounded as email developed into a primary source of communication for personal and business use. Antivirus products modified their approach to also scan outgoing email for viruses. Free webmail services like Yahoo! added virus-scanning capabilities to help stave off the threat. A similar evolution occurred in other products, such as web browsers and email clients, in the form of toolbars and add-ons.

This made the AV industry a billion-dollar business.

The Virus Landscape

Before delving into the issues surrounding antivirus products, we want to cover pertinent aspects of the viruses themselves—taxonomies, classifications, and naming conventions. All of these aspects impact the performance and scope of AV products. We’ll also quickly review the main types of viruses that plague systems today.

Understanding the capabilities of each virus type is important in order to determine the threat, its potential impact, and a plan for incident response and/or handling. Viruses generally operate in a dedicated environment, such as the file system or boot sector or within a macro. We’ll look at typical file and boot sector viruses, which have remained in public purview for over 25 years; the development, growth, and success of macro viruses; and the evolution of complex viruses. Later in this chapter, we’ll cover examples of each virus type to illustrate real-world examples of viruses and what makes them successful.

Definition of a Virus

A virus, in its purest technical definition, is a file that modifies other files by taking control of its execution flow and/or by attaching itself to the target file. A virus can modify system objects on disk or in memory or disrupt normal system operation in some way. Viruses tend to be destructive to the system, attached devices, and data. A virus should not be confused with related terms such as worms, Trojans, backdoors, and other malware, although the capabilities of all of these tend to overlap. Here is a quick summary of the distinctions among these various types of malware:

• Trojan Horse A program that claims or appears to have—or creates the perception of having—a certain functionality yet does something really malicious.

• Worm A program that autonomously propagates across networks by infecting host machines.

• Backdoor A stealthy program that bypasses normal authentication or connectivity methods to provide unauthorized access to a computer.

Another classification of malware-like programs is grayware, which typically includes adware and spyware, programs that are not as dangerous as malware but can still reduce system performance, weaken the system’s security posture, expose new vulnerabilities, and generally install nuisance applications that can affect the system’s usability.

• Spyware A program that captures data, which includes but is not limited to computing habits, to create a profile of the user.

• Adware A program that serves advertisements, usually through pop-ups, based on the collected computing habits of a victimized user.

Viruses, on the other hand, infect existing programs and applications and spread by infecting these applications on host machines. Depending on the specific goals of the virus, it may also escalate its privileges using privileged system functions and even install a rootkit for entrenchment. Most viruses do not attempt to be stealthy, unless the virus is advanced and includes polymorphic capabilities.

A computer virus is analogous to a biological virus in many ways: it relies on a host to survive and has representative characteristics that can be used to identify and inoculate against the virus.

Antivirus products were originally intended to inoculate programs against known viruses. Since that time, antivirus products have expanded in step with the growing classes of malware and grayware and generally advertise the capability to detect all of these types of programs. This chapter, however, focuses solely on viruses.

Classification

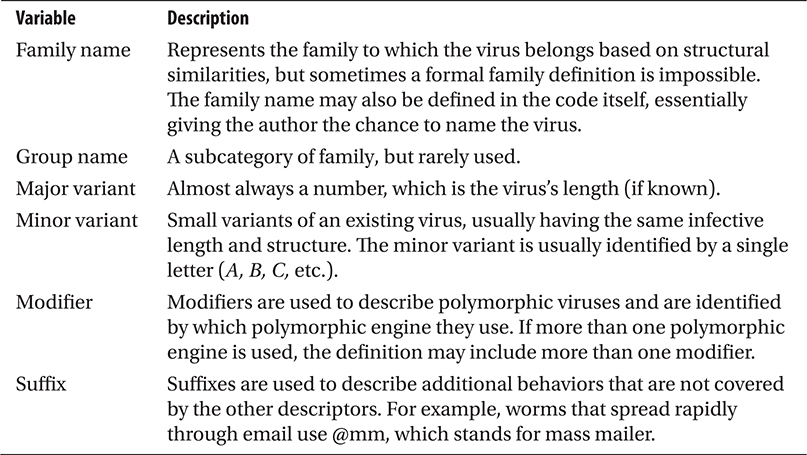

Virus researchers classify viruses using a taxonomic system to maintain order in the field of virus research and information sharing. Rather than belaboring the topic of computer virus naming-convention standards and the lack of updates since the early nineties—a sentiment of frustration shared by Symantec (http://www.symantec.com/avcenter/reference/virus.and.vulnerability.pdf) and other AV vendors—we’ll provide a brief reference guide for generally accepted naming conventions. In 1991, the Computer AntiVirus Researchers Organization (CARO) formed a committee to provide a standard naming convention for virus research. The convention agreed upon is

OS/Platform.Family_Name.Group_Name.Major_Variant.Minor_Variant[:Modifier]@suffix

Each part of the naming convention should only use alphanumeric characters, which are not case sensitive. Underscores and spaces may be used to increase readability. Each section should be limited to 20 characters.

Table 7-1 describes each part of the naming convention set forth by CARO.

Table 7-1 CARO Virus Naming Convention Descriptions

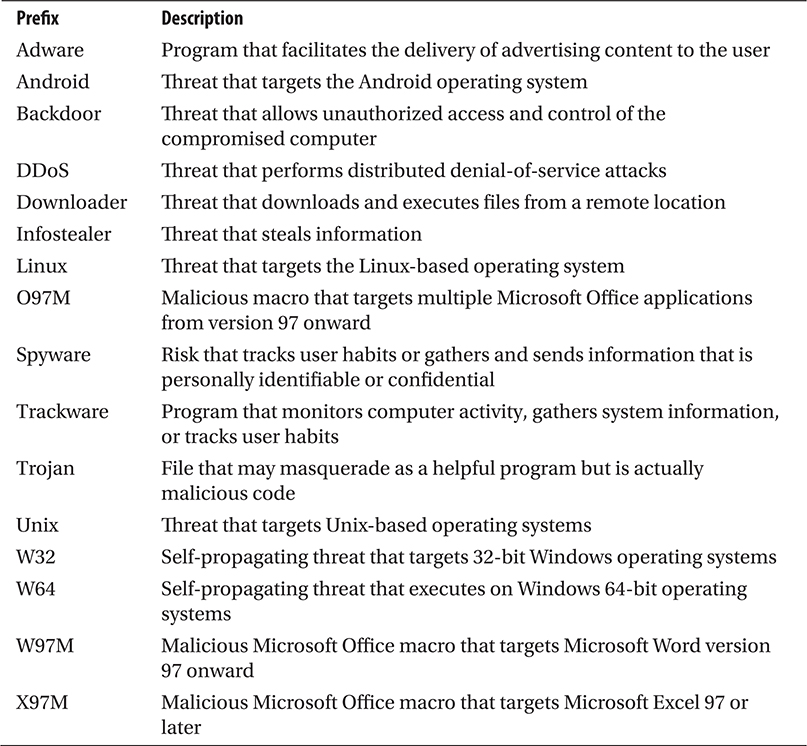

Table 7-2 contains common prefixes used today. For more information about suffixes and for a complete list of prefixes, you can go to Symantec’s website at http://www.symantec.com/security_response/virusnaming.jsp.

Table 7-2 Standard Virus Naming Convention Prefixes from Symantec

Simple Viruses

In this section, we’ll cover several virus types and their attributes. These viruses are known as simple or pathogen viruses. These programs have been the mainstay of malware for the past quarter-century.

File Virus

File Virus

In addition to the basic intent of a virus as defined previously, a file virus infects one or more executable binaries that reside on disk. Usually this means adding functionality to the file, but it can also constitute partial or complete overwriting of the file. This type of virus achieves stealth by hiding itself in a potentially trusted file, so the next time the user loads the file, the virus gets executed as well. However, as noted in our definition of a virus, stealth is not a primary goal.

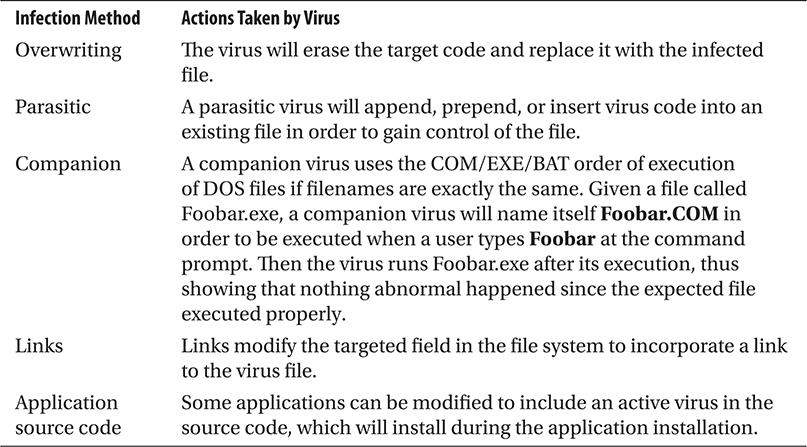

To carry out these actions, the virus must use some method of infection. Table 7-3 shows common methods used to infect the system.

Table 7-3 Common File Virus Infection Methods

Boot Sector Virus

Boot Sector Virus

Boot sector viruses are designed to infect the Master Boot Record (MBR) of a system’s hard drive. The Master Boot Record, one type of a boot sector, stores information about the disk, such as the number and types of partitions. In drive geometry terms, the MBR is always located at location cylinder 0, head 0, sector 1.

The boot process is initiated in firmware by the system BIOS and then transferred to whatever operating system is installed, which is pointed to by the MBR. A boot sector virus simply infects the MBR on the system; the BIOS executes the virus instead of the operating system. The virus moves a copy of the original boot sector to another location on the disk so the virus can pass control to the original boot sector to continue with the normal boot process.

The virus must be present in the boot sector of the primary boot device on a computer system in order to be executed. This boot sequence can easily be modified in modern BIOS programs to point to a CD-ROM, USB device, or disk drive. If the system boots from uninfected media, the virus will not get loaded.

Macro Virus

Macro Virus

Macro viruses were popular in the mid-1990s when the Macro functionality was introduced in the Microsoft Office suite. Macros allowed users to perform specific tasks within the Office suite that went beyond typical content/data generation/processing. In other words, an application macro (or just macro) was a programmed shortcut to a task that was often repeated. What viruses exploited with the introduction of this functionality was the ability to save code inside the document and transfer the same code to other similar documents, thus replicating or propagating to other files.

The use of macros, while extremely useful and beneficial, also proved to be very damaging. Macros programmed in Microsoft Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) and Word Basic can be loaded automatically when Microsoft Office applications are loaded. This offers the virus an ideal opportunity to launch without notifying the user. For example, a user receives an email containing an attached Word document and opens it. The Word document launches, and the macro virus is loaded on the target system. The automatic loading of macro viruses can be done through hundreds of different macro types and on any application that can support document-bound macros. Microsoft applications are commonly targeted for this type of virus because of their global popularity/adoption rate, extensive integration, and support of macros.

Most applications disable many macro controls by default or require user interaction in order to run the macro. The Microsoft Office Isolated Conversion Environment (MOICE) (http://support.microsoft.com/kb/935865) is a free tool developed by Microsoft that helps prevent macro viruses in Office 2003 and Office 2007 from ever running by dynamically converting binary Microsoft documents into the Office open XML format in an isolated sandbox. This conversion removes any malicious content that may cause a virus to load and execute successfully. MOICE is recommended as a basic security measure by the National Security Agency (NSA) in one of their Mitigation Monday unclassified papers.

In 2015, Sophos saw an attack utilizing a macro virus. Cyber criminals went way back because of the belief that it is easier to transmit a booby-trapped document than an executable file to a target system since it is common practice for organizations to block the transmission of executable files to and from the organization. More about Sophos’s findings can be found in their blog: https://blogs.sophos.com/2015/09/28/why-word-malware-is-basic/.

Complex Viruses

In this section, we’ll look at how complex viruses have evolved in the constant “arms race” between virus development and detection. This has kept the creativity within virus development efforts alive, as attackers search for new techniques to evade or sidestep antivirus software while antivirus development companies continue to defend against global virus attacks.

Encrypted Viruses

Encrypted Viruses

The encrypted virus was the first major breakthrough in an effort to avoid detection by antivirus software scanners; an encryption engine would encipher the text, helping to evade ASCII or hex-detection scanning of a simple antivirus engine. The concept was to encipher the virus payload and utilize a self-decrypting module in order to execute the code at runtime. This prohibited the antivirus scanner from detecting the virus through older signature-detection methods. However, antivirus software signature-detection techniques evolved to focus detection on the decryption modules themselves, which were found and analyzed within the previously discovered copies of the virus.

Oligomorphic Viruses

Oligomorphic Viruses

The next logical step for encrypted malware after their decryption routines were regularly detected by AV products was to randomize the decryption routine itself. Oligomorphic code is a code sample that is able to select among several decryptors randomly in order to infect a target. This allows oligomorphic viruses to take the basics of an encrypted virus to a higher level by utilizing multiple decryptors. An oligomorphic virus is capable of changing the decryptor, just as a polymorphic virus (explained next) can; however, it cannot change the encrypted base code. Some viruses are able to create multiple decryptor patterns that are unrecognizable in each new generation to avoid signature-based antivirus detection.

Polymorphic Viruses

Polymorphic Viruses

The most common type of morphing code in some viruses is polymorphism. Polymorphic viruses are able to create an unlimited number of new decryptors that can all use different encryption methods on the virus body. Polymorphic engines are designed to use pseudorandom number generators as well as techniques to create multiple variations of bogus code in order to obfuscate the body of the virus code, making it extremely hard to detect the virus.

Metamorphic Viruses

Metamorphic Viruses

Metamorphic viruses differ from polymorphic viruses in that they do not contain a constant virus body or decryptors. With each new generation, the virus body itself morphs just enough to evade detection. This morphing code is encapsulated in one single code body that is able to carry the virus code. The largest significant identifier of metamorphic code is that it does not completely alter its code. Rather, it simply modifies its functionality, such as swapping registers, altering flow controls, and reordering independent instructions. These relatively insignificant semantic alterations have no impact on the virus’s capability and easily fool many AV products.

Entry-Point Obscuring Viruses

Entry-Point Obscuring Viruses

The last type of complex virus worth discussing is the entry-point obscuring (EPO) virus. This type of virus is designed to write code at a random location within an existing program in the form of a patch or update to that program. Then, when the newly infected program is executed, it, in turn, jumps into the virus code and begins executing the virus instead of the trusted program. Now that the virus can be executed from within a trusted program on the machine, the antivirus engine is less likely to detect this execution method. This family of viruses is still common today and capable of operating for long periods of time undetected on a system.

Antivirus—Core Features and Techniques

The ultimate goal of AV products is to protect endpoint hosts from malicious software, specifically the types of viruses previously discussed. Therefore, AV products typically install on the host machine and run various services and one or more agents, collectively known as the antivirus engine. There are two primary modes of detection engines: manual or on demand and real time or on access.

Manual or “On-Demand” Scanning

The most rudimentary capability of an AV product is to scan files when directed by the user. Usually this scenario involves a security-conscious user downloading a program or a file attachment and then initiating the on-demand scan for that file. Because this method requires user interaction to initiate the scan, the system is not protected from a large class of dynamic malware such as macro viruses that execute when a document is opened. If users aren’t aware of macro viruses, however, they won’t know to scan the file before opening it. Even if the user does scan the file, the detection is only as good as the AV product and its underlying engine. In either event, there is no guarantee that all viruses will be detected.

An on-demand scan is effectively an offline scan, meaning the file is stored on disk and is not being executed. The AV engine will inspect the file on disk and compare it with binary signatures in its signature database (we’ll get to signature scanning shortly). If the antivirus engine finds a match, the AV program will alert the user that the file is infected and offer various remediation actions such as to delete, rename, or quarantine the file. Quarantining the file typically involves the AV product moving the file to an isolated folder on the hard drive where it is disabled and marked “nonexecutable.” This prevents the file from being accidentally executed by the user.

Because this type of detection relies on user-initiated scanning, most AV products offer this as a secondary product capability. The most useful scanning is offered in one or more dynamic, real-time components that actively scan for viruses transparently as the user works on the system. This is known as on-access scanning.

Real-Time or “On-Access” Scanning

On-access scanning occurs mostly without the user’s knowledge. As the user opens applications, reads email, or downloads web content, the AV engine is constantly scanning the system’s memory and disk for viruses. If a virus is detected, the AV product will first attempt to halt the malicious activity (e.g., if it is network activity, the AV will block the activity) and then notify the user to take action. This type of scanning is the opposite of on-demand scanning, which takes place offline.

On-access scanning is the primary detection method for all major AV products on the market today. The details of how this type of detection is implemented are, of course, proprietary, but each vendor uses well-known techniques to detect viruses. In fact, you may notice a striking similarity to techniques discussed in Chapter 4. An on-access scanner triggers a scan of files at these times:

• On write When the file is being created and written to the disk

• On execute Before the file is loaded in memory for execution

If a malware signature match is found, the engine issues an infection alert.

On-access and on-demand scanning complement each other in the monumental task of protecting a computer from thousands of active security threats. Almost all antivirus vendors combine these scanning engines to create a more robust product. On-access protection ensures users have some sort of “real-time” protection as they work with files and programs on a daily basis and helps stop malicious programs that users may not or cannot scan manually. On-access protection increases the likelihood that newly introduced executable files will be scanned before they’re executed. Best practice is to also run your own regularly scheduled on-demand scans. Regular offline scans can help detect malicious programs that were loaded before the real-time engine was up and running.

Signature-Based Detection

Signature-based detection has been used by AV companies since the dawn of the industry. This is the bread and butter of AV products because it represents a living and breathing list of known malicious viruses that keeps the cash flow steady in an industry whose future is in question. AV companies rely on subscriptions from consumers and corporations alike for a substantial portion of their income. These subscriptions, which include product updates and patches, are largely for signature update files that are distributed multiple times throughout the day. These files keep the user’s AV product up to date with the latest signatures for viruses in the wild and those that were sourced and collected by the security vendor’s researchers.

The signature itself can be as simple as a string pattern match or byte signature or as complex as a scoring system that examines attributes of the suspect file to gauge its capabilities. A string-matching signature can contain wildcards and is flexible enough to detect padding or garbage in viruses that attempt to morph during execution. Signature schemes and formats vary among the numerous AV vendor products available, and each product uses different algorithms and logic to select identifying virus features to form signatures. However, the basic process involves disassembling the binary code of known viruses and recording byte sequences that implement the virus’s core capability. A very simple example of a byte sequence signature to detect Portable Executable (PE) files, a format every executable program on a Windows system must contain to run, is to scan a file for the MZ header byte sequence 4D 5A. Every PE file contains these two bytes. A more realistic example of a byte sequence signature is the byte signature of a well-known encryption or packing library (such as Ultimate Packer for Executables, or UPX) that most malware, specifically Trojans, worms, and backdoors, use as part of their source code.

The other type of signature, basically a template for a scoring system, is implemented in the scanning engine logic and relies on signature templates that are filled dynamically during scanning. An example template contains various attributes of the potentially malicious file, such as what libraries the program uses (i.e., ones that would allow Internet connectivity, encryption, and sensitive system libraries); whether it is packed or compressed (often viruses will pack their files to evade signature-detection engines); whether it has an encryption/decryption routine (which may indicate it encrypts its own code to evade AV detection); and other attributes of the PE header section of the file (if it is an executable) that may indicate tampering or invalid values meant to confuse signature scanners (such as an invalid program entry point).

Beyond the very basic, regular-expression pattern matching and the somewhat “real-time” nature of the signature templates, very little dynamic capability is inherent to signatures. In the end, there must be an exact signature match for the virus to be detected, and as we have shown previously, viruses are rarely this predictable.

Signature-based detection has several well-documented weaknesses:

• It relies on a signature database that must be constantly updated, requiring action on the part of both the vendor (to produce the list) and the consumer (to download/install it).

• The signature database is a static snapshot in time and becomes immediately outdated once it is released to the consumer.

• There are literally hundreds of thousands of viruses in the wild, each having potentially thousands of various strains and mutations that require their own signature; this includes only the viruses the AV companies know about.

• It can only detect malware behavior and/or characteristics that it knows about.

• Self-modifying malware such as metamorphic viruses may defeat signature-based detection engines, but most AV engines have evolved to emulate or sandbox metamorphic code generation and obfuscation so the decrypted code can be matched with signatures without any cloak.

As shown in test results by av-test.org, an independent AV testing group, AV products are pretty good at detecting viruses based on signatures (see https://www.av-test.org/en/compare-manufacturer-results/). In their November–December 2015 report, the industry average for detection of widespread and prevalent malware during that time period was 99 percent. This doesn’t address the capability of the AV product to defend the system against active threats, however—the results simply indicate how good the AV company’s signature-writing capabilities are. And you would think the antivirus vendor would be fairly adept at such a process, having had decades of practice.

Anomaly/Heuristic-Based Detection

Heuristic-based detection attempts to make up for shortcomings in signature-based detection, as well as provide some rudimentary defense for end users until the virus is discovered and a signature can be produced and released by the AV vendor. Rather than scanning a system for known, static signatures, heuristic detection observes system behavior and key “hooking points” for anomalous activity in a proactive manner. Some example heuristic techniques include

• Checking critical system components that are commonly abused by malware, such as SSDT, IDT, and API functions for hooking.

• Behavior blocking—profiling or baselining applications for normal behavior—so when an application displays abnormal behavior, the application may be considered corrupt (an example is MS Word trying to connect to the Internet).

• Memory attribute monitoring—in other words, if a memory page is marked executable, it will be monitored more closely than nonexecutable memory, especially if the attribute changes during runtime.

• Analysis of program Portable Executable (PE) section information within the file binary, searching for malformed sections or invalid entries meant to confuse analysis engines.

• Presence of anomalous code and/or strings in a process or program.

• Weight-based and rule-based scoring systems that look at multiple areas.

• Presence of packed, obfuscated, or encrypted code/sections.

• Analysis of decompiled/disassembled code to determine abnormal operations such as pointer arithmetic with static (and valid) addresses.

• The use of expert systems, a concept in artificial intelligence whereby the product trains on datasets and learns to predict behavior over time.

Some antivirus engines use the malformations described here as signatures or data for scoring-based algorithms.

Antivirus products have evolved to use optimized heuristic capabilities that are no longer system hogs, nor do they have significant effect on system performance. AV-test.org shows an industry average of two seconds when it comes to the product’s influence on computer speed in daily usage when visiting websites, downloading software, installing and running programs, and copying data. On usability, the industry average for false detections of legitimate software as malware during a system scan is 5 percent. Improvements have been made, but there is always room for more.

A Critical Look at the Role of Antivirus Technology

We’ve described the capabilities and techniques of AV technology, but now we’ll shift gears and discuss the role of AV in the computer security industry. This role is somewhat controversial and has been debated for many years. We’ll start with the good news.

Where Antivirus Excels

The good news is AV technology has a place, and it does some things very well. As noted in “Signature-Based Detection,” AV performs with extreme accuracy when detecting viruses that have at least one publicly known signature. This capability is an important one because it captures a lot of “low-hanging fruit”—that is, ten-year-old malware that is somehow still in the wild. This type of malware is easily caught by most modern AV engines. In short, AV, in general, is good at catching what it knows about.

Security professionals should not be so quick to dismiss this capability. In today’s highly distributed enterprise networks, basic system and network hygiene is difficult to maintain. A strong AV solution is considered a bare necessity and fundamental requirement of basic system hygiene.

As part of corporate AV strategy, the use of host- and network-level controls can greatly enhance overall security posture, particularly as it relates to virus infections and worm propagation. When designing an enterprise AV policy, complement host-based software with network-based controls such as network intrusion detection systems (NIDS), firewalls, Network Access Control (NAC) devices, and Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems. Properly configured and maintained rules, alerts, and filters can prevent virus attacks, from low-level to enterprise-wide events.

The information logs collected via these devices can greatly increase awareness of potential virus threats and suspicious events. Properly configuring and maintaining these devices will go a long way toward preventing virus and worm threats, as well as providing excellent information for those who need to monitor and respond to virus incidents.

AV also serves the purposes of the average home user, a fairly large customer base. There’s something to be said for the peace of mind an AV product can provide, and sometimes considering alternatives to AV is not necessary—Granny doesn’t need to surf in a virtual machine (VM). On systems such as these, off-the-shelf AV products suffice.

Top Performers in the Antivirus Industry

The best practice to determine the top performers in the industry is to reference multiple antivirus test results from the AV-Test Institute, AV-Comparatives, Virus Bulletin, and PCMag.com, among others.

Challenges for Antivirus

Obviously, antivirus technology has mastered signature detection and has fairly impressive heuristics for some of the malware it’s up against. However, AV often falls short of expectations and has a notorious reputation for missing some very high-profile malware. In this section, we’ll take a critical look at these weak areas that have empirical data to support this claim.

Detection Rates

So why and how often does AV fail to recognize malware? Some of the numbers you will see from independent tests of known malware show extremely high detection rates. Perhaps this difference points out a disparity between reality and the lab. Results also vary wildly depending on the width and depth of the malware sampling used to test the product. Since there are literally hundreds of thousands of malware, some tiny nuances in one sampling may go undetected.

There are some logical reasons why AV products have mixed success in detecting malware. We’ve covered many of those reasons, such as complexity and the sheer volume of malware today. Detection may simply reduce to being a resource issue—there simply aren’t enough engineers to produce and test the signatures in a timely manner. AV products must also maintain a low profile and not impact system performance. This forces software-engineering decisions that may negatively impact detection rates. Heuristic engines have been shown to produce higher false-positive rates, something that is unacceptable in corporate environments. Thus, AV companies might have to throttle some detection capability to improve the false-positive rate.

Response to Emerging Threats

Perhaps one of the most crucial measures of a successful AV product is how quickly the company responds to new and emerging malware.

When the Target breach happened, researchers from various security vendors immediately went to work to investigate, capture, and analyze the suspected malware involved. When Stuxnet was discovered, research into Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems and how Stuxnet was able to take control of such systems went into high gear. It was critical for security vendors to respond quickly to these new and emerging threats because they understood that corporations and home users rely on anti-malware products as their last line of defense when it comes to endpoints. The first vendor that provides information and a solution gets the attention and has better positioning when it comes to selling its products. As with the Target breach and Stuxnet, nowadays, most attacks are targeted, so the emerging threat is not as widespread as it was before. Attacks are usually low-key and designed for a specific company, like the retail chains that were breached in 2014, including Target, Home Depot, and Michaels. A security-conscious enterprise must have a capable incident response team as part of their security team or have the ability to contract such teams from a security provider.

Then there’s the problem of customer acceptance and implementation: just because a signature is available doesn’t mean a customer has his or her AV product configured to automatically download and install new updates. Thus, adoption of the latest signatures is solely dependent on the customer, so the success of AV products (and halting the spread of an active virus) will always be determined by the customer. This fact is particularly true for home users, which is why most opportunistic attacks aimed at home users are typically successful.

Large networks and enterprise environments have to comply with policies and regulations defined by a governing body or agency, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), if the enterprise falls under its umbrella. AV updates are usually downloaded by a central management server, which, in turn, delivers the updates to hosts connected to the network. These updates are set to be installed on a schedule. During this gap, hosts continue to be vulnerable. The situation is even worse for production (live) servers that endure additional delays. Most companies require updates to be manually tested in an offline network before they are applied to live servers (otherwise, any incompatibilities or bugs in the update could force a reboot of the live server that would impact business operations).

This time delay between the release of an updated signature from the AV company and the installation of the update on end hosts is perhaps the greatest weakness in the signature-scanning concept and continues to plague the industry. Not every corporate network has implemented or properly follows an aggressive AV update policy. It is not uncommon to find production servers with outdated signature databases that are months to years old.

Keep in mind that just because a particular vendor is fast at releasing updates doesn’t mean the updates are of high quality. Knee-jerk reactions can be just as dangerous as not reacting at all. Plus, the response times for any particular AV company will depend on how the company chooses to classify the virus threat when it learns of it. If a vendor considers a certain virus to be a medium threat, it will give it less attention, and therefore, the response time will be slower.

On a final note, it is also important to consider how frequently a vendor releases updates. A certain vendor may have very fast response times for an attack that garners media attention, but whether it provides consistently high-quality and regular updates throughout the year may be an entirely different story.

0-day Exploits

A 0-day (zero-day) exploit is a working piece of attack code that targets a previously undisclosed vulnerability in a system. We’ve discussed how signature-based detection fails to detect malware that modifies its code dynamically (such as metamorphic and polymorphic viruses), as well as how heuristics can fail to detect advanced malware. The 0-day class of malware represents the hardest target for any detection system. And because AV detection strategies rely on things they have seen before (whether it be a signature or a heuristic behavior), this makes 0-day detection extremely problematic. Although some 0-day exploits may be caught by AV engines due to similarities in the underlying exploit (for example, many 0-day exploits attempt to open a remote shell that allows remote console access to the victim machine), most evade AV detection simply because the AV engine can’t reliably detect what it doesn’t know about.

Vulnerabilities in Antivirus Products

No software is perfect. Antivirus products also fall prey to vulnerabilities caused by bugs and design flaws in their software. Most reputable security companies are well aware of this risk and always take precautions to make sure that whatever they release has been tested multiple times for vulnerabilities.

Keep in mind that vulnerabilities in security products make them a prime mark for malware writers to exploit, motivating them to create malware that targets antivirus products to evade detection.

The Future of the Antivirus Industry

Signature detection is not only the antivirus industry’s strength but also its weakness. It’s a strength because it gives AV products the ability to pinpoint specific malware with minimal false positives. But it’s a weakness because a signature approach cannot handle the onslaught of the millions of malware we see today. The future of the antivirus industry will depend on how it adapts to the ever-changing threat landscape, which is being shaped by attackers who are able to produce millions of malware on a monthly basis.

The biggest threat to the antivirus industry is the malware factory. Regardless of what other features an antivirus product may add in the future, if it cannot solve the malware factory problem, the industry will be deemed irrelevant. In a malware factory, which Christopher Elisan first introduced in his book Malware, Rootkits & Botnets: A Beginner’s Guide (McGraw-Hill Professional, 2012), malware is produced at a staggering pace. If a malware factory installation can produce 100,000 unique malware samples in a day, researchers will have a hard time catching up without any automated sandbox systems to analyze and gather IoCs (indicators of compromise) from each malware sample. Signatures are generated automatically from these IoCs, meaning there is one signature for every sample. So, for 100,000 samples, the result is 100,000 signatures. This will bloat the antivirus product’s signature database, which is not advisable.

To thrive, antivirus products need a new approach to detecting malware, for instance, a signatureless approach that can make sense of all the indicators of compromise. Think data science and machine learning instead of signature creation. Data produced by automated sandbox systems and static analysis systems are processed to create meaningful features that can be used to come up with an algorithm that will detect malware of a certain family or classification. Rather than a 1:1 signature, there is an algorithm that can detect malware from the same family or class.

Not that signature detection will be abandoned altogether. It can still be employed, especially if specific detection is needed. A good combination of both will help the antivirus industry to prosper.

Summary and Countermeasures

We discussed the issues surrounding antivirus technologies in reasonable depth in this chapter, and the reader should now be up to speed on the current state of the industry. Antivirus weaknesses and strengths were covered; some skeletons in the closet were revealed (not for the first time); and a few possible outcomes for the industry’s future have been surmised. What should the reader take away from this chapter?

Simply put, for now, keep your AV product. Wait and see how things turn out. For the average home user, antivirus is a must in today’s rapidly evolving, Internet-based world. With the number of antivirus companies, products, and integrated services, antivirus has become a necessary last-line defense against malicious infections. For home users, the solution is relatively simple: install and configure automatic definition updates. Required updates will then be downloaded and installed without any user interaction and greatly increase your security posture while giving you piece of mind.

As for enterprise networks, we highly recommend a dedicated security team that is responsible for the constant maintenance, updates, and administration of the enterprise security solution. It is also imperative, if resources allow, to establish a security response team, or at least access to one, when an attack is detected within the organization.

Most antivirus vendors have integrated several products into an information security suite that allows for antivirus, desktop firewalls, host intrusion detection, and even network access control from a single application. However, every enterprise must ensure that the updates are reaching 100 percent of users to maintain a 100 percent effective antivirus solution.

Most likely, the AV industry will not make a major course correction because business is good. There’s nothing wrong with this, as long as users are informed about what the AV product is doing and understands its limitations. The real danger is when users assume AV will protect them 100 percent from viruses and malware.

Users should educate themselves on what AV products offer and some possible alternatives. Common sense is also highly recommended. When used, some very basic best practices can prevent a majority of malicious software from bothering you:

• Do not log in as administrator for everyday computer use.

• Use built-in Microsoft technologies like Data Execution Prevention (DEP).

• Use your browser’s protected mode.

• Use perimeter defenses as part of a layered security strategy.

You should plan ahead and know how to recover in the event your system becomes infected. Such a proactive approach to security includes

• Use Windows restore points and the PC backup feature when you first use a new computer.

• Use Symantec Ghost Solution or similar application to create a backup of your entire system.

• Utilize “shadow partitions” to maintain a redundant, restorable copy of your OS.

• Back up critical data to read-only media.

The concept of “reimaging” a system is a common response action when a virus infection is discovered. Reimaging a system typically involves restoring the system to a “known good state” by overwriting the hard drive with a baseline backup image that includes only basic software and system files. This action essentially reverts the system to a known good state with minimal software. Be careful not to rely on simple reimaging as a defense against virus infections, as backup copies can be infected as well. Additionally, the attack vector may still exist on your newly reimaged system, ready to be exploited again by attackers.