CHAPTER 1

MALWARE PROPAGATION

Malware Is Still King

We are close to the end of the second decade of our new millennium, and we are still seeing an explosion of techniques, tools, platforms, and capabilities that most were surprised to see a decade ago. Since our first edition, the landscape has changed a great deal in terms of the techniques used, but, surprisingly, much has remained flat when it comes to methods of infection. Criminals have riddled networks with new concepts, campaigns, and tools that have boggled the minds of millions around the world. Several new variants of threats have shaped and brought us to where we are today. Employers have grown increasingly nervous about the morning news headlines, as the possibility of being breached by a nameless threat that pillages networks of countless valuables has become ever present.

It’s become the norm for sensitive data from breached companies and organizations to be dumped on the Web, free for all the public to see. Most of the time, these breaches are made possible through malware compromise. Malware is propagated to targets, and if the targets are not well equipped to defend against the onslaught of malware delivery and various propagation techniques, they may well be on their way to a news headline.

Clearly, malware is still king; it is still king when it comes to the threats plaguing the interconnected world of digital assets and devices.

The Spread of Malware

Malware is still spreading at breakneck speed. The technologies used to spread malware remain the same but with improvements tailored specifically for the target entity. Let’s take as an example the email used by the attacker in our previous case study. It shows that the phishing email used was crafted to contain content that was only applicable to the target by mentioning the quarterly meeting. Since the first edition of this book was published, most attacks target organizations using customized malware-spreading techniques.

Attackers are still using these tried-and-true techniques. And they are still motivated by money, the theft of sensitive information, and sustained unauthorized access to target systems. This is why attackers now build their creations to be stealthier, more discreet, and target customized. Malware has become more for profit than for fun.

Why They Want Your Workstation

Technology advances and the availability of attack vectors were factors in attackers changing their methods, but their target, you, ultimately made the decision for them. Authors of malware and rootkits realized they could generate revenue for themselves by utilizing the malware they were creating to steal sensitive data, such as your online banking username and password; commit click fraud; and sell remote control of infected workstations to spammers as spam relays. They could actually receive a return on investment for the time they put into writing their malware. Your workstation is now worth much more than it was before; therefore, the attackers’ tools needed to adapt to maintain control of infected workstations as well as infect as many other workstations as possible. It is important to note that by using other people’s machines, the attacker achieves the following:

• Makes it harder to link the crime back to the attacker

• Prevents isolation of the culprit because infected machines are typically business critical

• Leverages the computing power that an army of bots offers

The home user is just one target of malware authors. The corporate workstation is just as juicy and inviting. Enterprise workstation users routinely save confidential corporate documents to their local workstation, log into personal accounts online such as bank accounts, and log into corporate servers that contain corporate intellectual property. All of these items are of interest to attackers and are routinely gathered during malware infections.

The workstation is the attacker’s main source of sensitive information. It is also the springboard to gain access to network servers, especially if the workstation has privileges to connect to highly protected network segments within an organization.

Intent Is Hard to Detect

The change in landscape has increased the technical challenges for malware authors over the years, but the greatest change has been a change in intent. In years past, many virus authors wrote viruses purely for ego gratification and to show off to their friends. Virus writers were part of an underground subculture that rewarded members for new techniques and for mass destruction. The race to be the smartest author caused many virus authors to push the envelope and actually release their creations, causing massive amounts of damage. These acts were synonymous with the plot of many bad movies in which two boys constantly try to “one up” each other when fighting over a girl in high school but all they leave is destruction in their wake. In the end, neither gets the girl and the two boys end up in trouble and looking stupid. The same was true for virus authors who released viruses. In countries where writing viruses is illegal, the virus writers were caught and prosecuted.

Some virus authors weren’t in it for ego but for protest, as was the case with Onel A. De Guzman. De Guzman was seen as a Robin Hood in the Philippines. He wrote the portion of the ILOVEYOU virus that stole the usernames and passwords people used to access the Internet and gave the information to others to utilize. In the Philippines, where Internet access cost as much as $100 per month, many saw his virus as a great benefit. In addition to de Guzman, Dark Avenger, a Bulgarian virus author, was cited as saying he wrote viruses and released them “because they gave him a sense of political power and freedom he was denied in Bulgaria.”

Today, malware and rootkits are not about ego or protest—they’re about money. Malware authors want money, and the easiest way to get it is to steal it from you. Their intent with the programs they have written has changed dramatically. Malware and rootkits are now precision-theft tools, not billboards for shouting their accolades and propaganda to friends. Why does this shift matter?

The shift to malicious intent by authors sent a signal to those who protect users from malware that they needed to shift their detection and prevention capabilities. Viruses and worms are technical anomalies. In general, their functionality is not composed of a common set of features that normal computer users may execute, such as a word-processing application; therefore, detecting and preventing an anomaly is easier than detecting a user doing something malicious. The problem with detecting malicious intent is in who defines what is malicious. Is it the antivirus companies or the media? Different computer users have different risk tolerances so one person may be able to tolerate a piece of malware running in return for the benefit it may provide, whereas someone else may not tolerate any malware.

Understanding the intent of a legitimate user’s action is hard, if not impossible. Governments around the world have been trying to understand the intent of human action within the law enforcement and legal system for years with little success. Conviction rates in most countries following an Anglo-Saxon legal system (such as the United States) range from 40 to 80 percent. If the legal systems around the world, which have been dealing with this problem for hundreds of years, have a hard time determining intent, how do we stand a chance in stopping malware?

We believe we do, but the battle is an ongoing struggle between the attackers and the defenders in the cyberwarfare community, which is why the remainder of the book focuses on arming you with the technical knowledge about how malware propagates, infects, maintains control, and steals data. Hopefully, armed with this information, you will be able to determine the intent of the applications running on your workstation and take the first step in defending your network against malware.

It’s a Business

As mentioned previously, malware authors are focused on making a profit. Like all entrepreneurs who want to make money, they start various businesses to take advantage of the situation. An attack campaign that has no return on investment for the cybercriminals is a waste of time. There has to be a return. Stolen information can be sold. Financial credentials can be abused. Unauthorized access to computer systems can fetch a handsome price from a competing organization.

Many groups out there offer malware-related services to those who are willing to pay. These cybercriminal groups often operate in countries where there are no laws regarding the commission of a cybercrime or where they can’t be traced or prosecuted.

Significant Malware Propagation Techniques

Malware traditionally employs attacks against platforms and applications such as Microsoft Windows, Linux, Mac OS, Microsoft Office Suite, and many third-party applications. Some malware has even been distributed unknowingly by manufacturers and embedded directly in installation discs only to be discovered several months later, which still occurs today. The two most popular forms of propagation in the late 1990s were via email and direct file execution.

Now, as insignificant as this brief history of viruses may seem to many of you, we highlight several malware outbreaks for significant reasons. Most important are the need to understand the evolution in techniques over the years to what is commonly seen today and to understand where these methods originated. We also want to illustrate how the “old reliable” techniques still work just as well today as they did more than 20 years ago. The security community has evolved into what it is today by learning the lessons from the propagation techniques they inevitably thwarted, but they now face a serious challenge in battling and stopping attacks based on these techniques. Finally, this section will serve as a quick overview for those readers who are newer in the community and were not around when these malware samples were more common.

Social Engineering

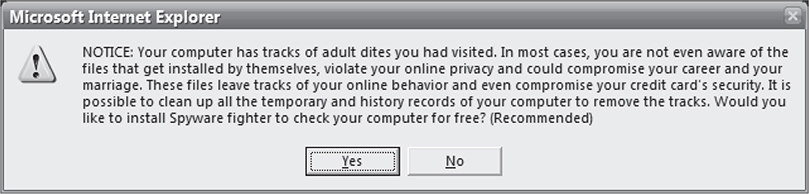

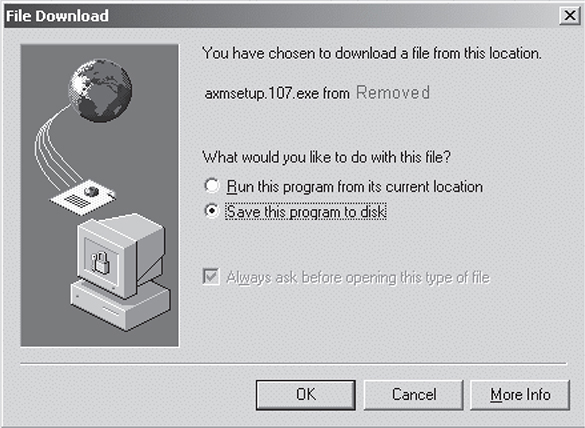

Historically, the oldest and still the most effective method for delivering and propagating malware across a network is to violate human trust relationships. Social engineering involves the crafting of a story that is then delivered to a victim in hopes the victim believes the story and then performs the desired steps in order to execute the malware. Typically, the user is unaware of the actual infection, although sometimes the delivery method or story by which the “false trust” is built is fairly shallow. Sometimes the user senses something is wrong or an event raises his or her suspicions, and after a quick inspection, the user discovers the overall plot. The enterprise security team then attempts to remove the malware and prevent propagation through the network. Without social engineering, almost all malware today would not be able to infect systems. Following are some potentially malicious screens that might build a “false trust” in hopes that the user will click away and become infected or provide personal information.

Here is a short list of ambiguous filenames malware writers have employed to entice unsuspecting social engineering victims to open the files, thus kicking off the infection process:

• ACDSee 9.exe

• Adobe Photoshop 9 full.exe

• Ahead Nero 7.exe

• Matrix 3 Revolution English Subtitles.exe

• Microsoft Office 2003 Crack, Working!.exe

• Microsoft Windows XP, WinXP Crack, working Keygen.exe

• Serials.txt.exe

• WinAmp 6 New!.exe

• Windows Sourcecode update.doc.exe

File Execution

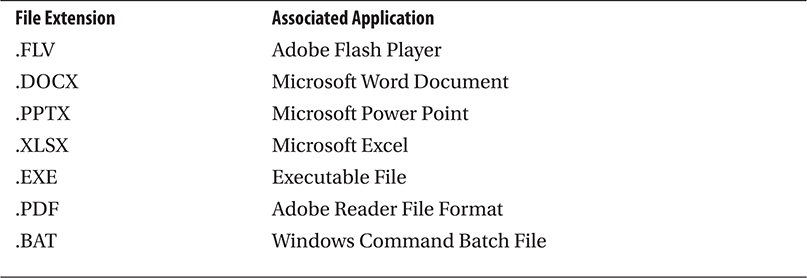

This is what it is; file execution is the most straightforward method for malware infection. A user clicks the file, whether renamed and/or embedded within another file, such as portable executables, Microsoft Office documents, Adobe PDFs, or compressed Zips. The file can be delivered through the social-engineering techniques just discussed or via peer-to-peer (P2P) networking, enterprise network file sharing, email, or nonvolatile memory device transfers. Today, some malware is delivered in the form of downloadable flash games that you enjoy while, in the background, your system is now the victim of someone’s sly humor such as StormWorm. Some infections come to you as simple graphic design animations, PowerPoint slides of dancing bears, and even patriotic stories. This propagation technique—file execution—is the foundation for all malware: Essentially, if you don’t execute it, then the malware is not going to infect your system. Table 1-1 lists some simple examples of various Windows-based file types that have been used to deliver malware to victims via file execution, and Figure 1-1 shows the most frequently emailed file types.

Table 1-1 Most Popular File Types for Distributing Malware

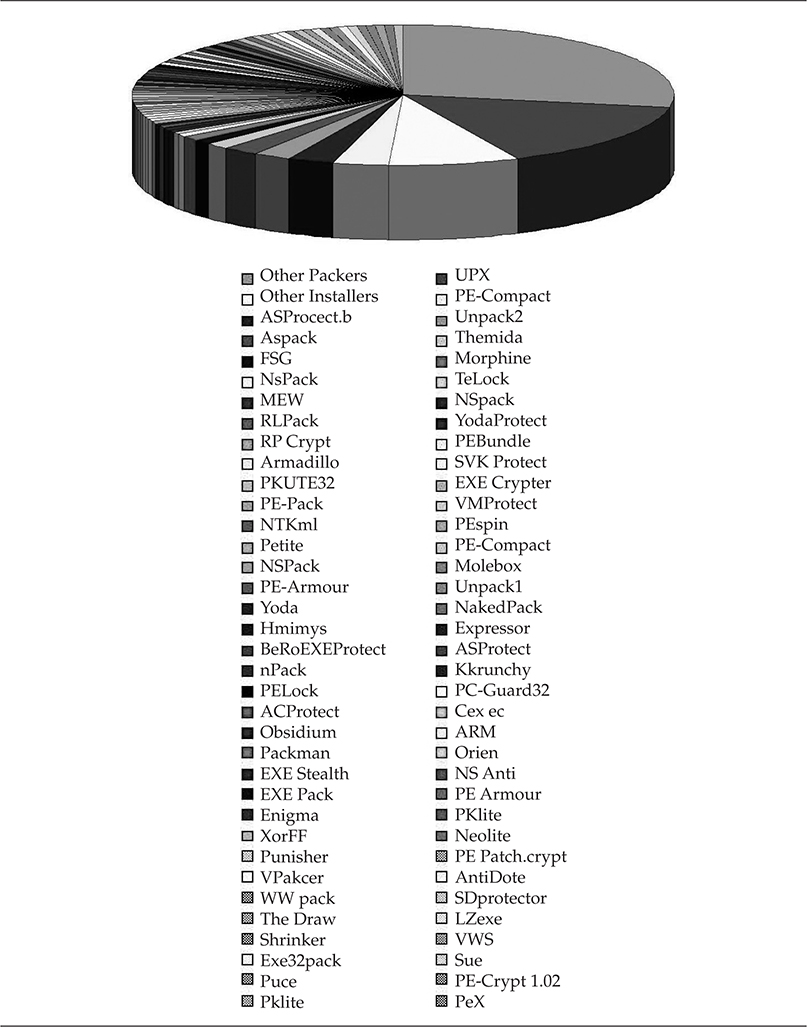

Figure 1-1 Most frequently emailed file types

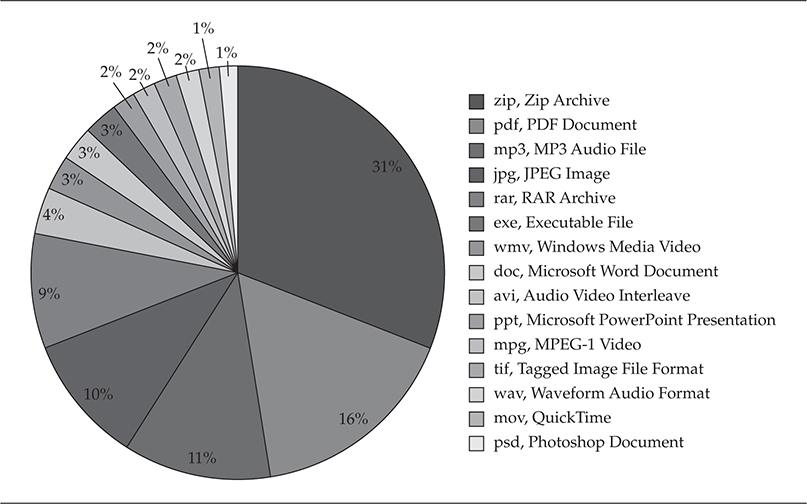

The forbearers of malware implemented methods that were novel and, for the most part, well thought out and not overly malicious beyond destroying the computer itself. These attackers were more focused on a show of ego and ingenuity through the release of proof-of-concept code. The malware they released did have several implementation weaknesses such as easily identifiable binaries, system entries, and easily detectable propagation techniques. But their methods kept security professionals up at night, wondering when the other shoe would drop, until better antivirus engines and network intrusion detection systems were developed. Figure 1-2 provides a simple timeline of the lifecycle of intrusion detection systems, which were the best tools in the late 1990s and early turn of the millennium for identifying malware propagating across networks.

Figure 1-2 Intrusion detection system timeline

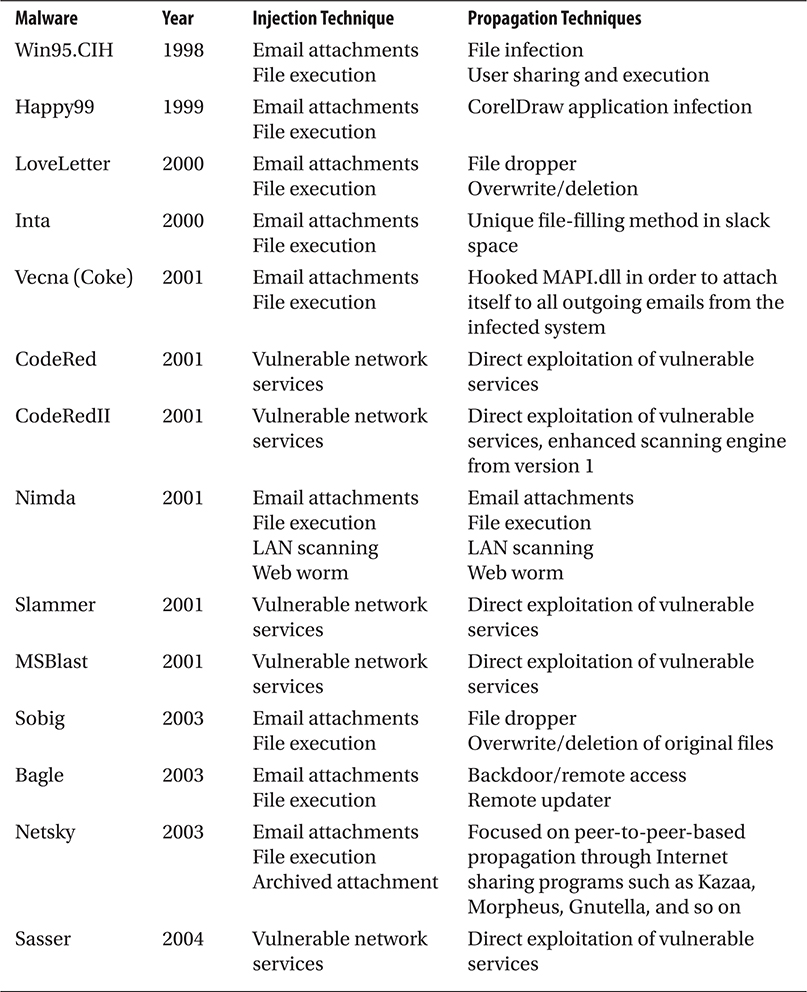

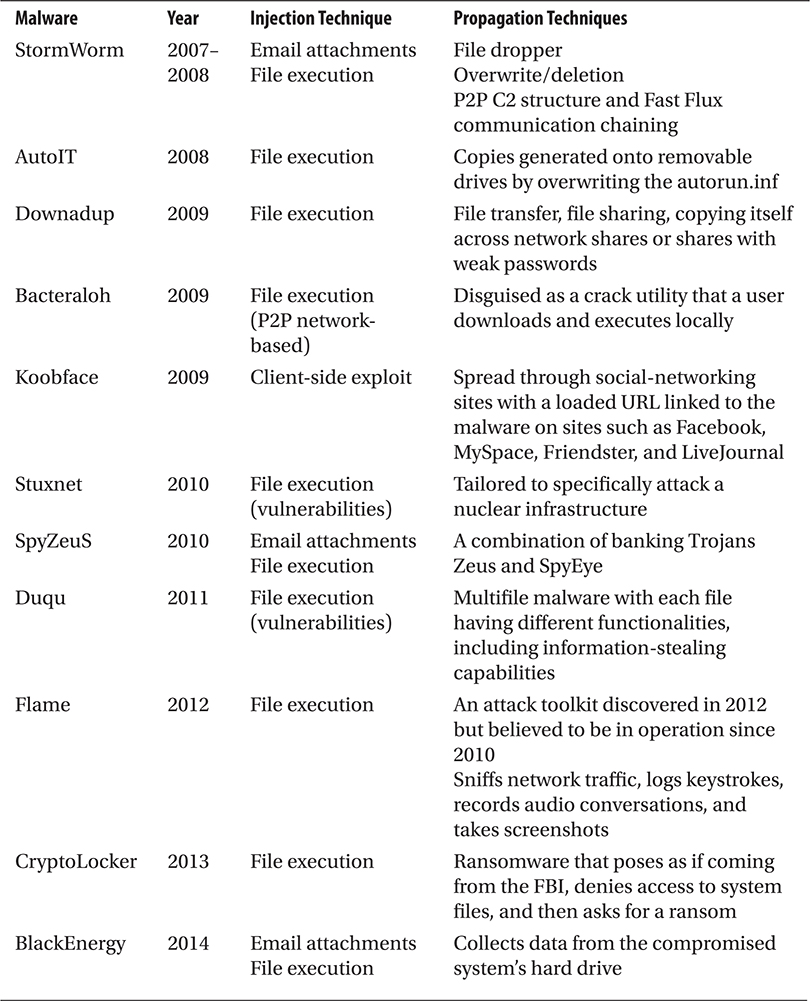

Table 1-2 breaks out the propagation techniques used in some of the most infamous early malware attacks.

Table 1-2 Propagation Techniques Used in Early Malware Attacks

Modern Malware Propagation Techniques

Thanks to very creative advancements in network applications, network services, and operating system features, identifying malware propagation has become much more difficult than it used to be for IDSs. IDS signatures have proven to be practically helpless against new malware releases or polymorphic malware. At the early turn of the millennium, an entirely new breed of propagation techniques was released into the world, techniques spawned from the lessons learned from prior malware outbreaks.

Malware trends have evolved to such a point that we now rely on experts to predict potential new outbreaks or methods where old techniques may lead to innovations that dwarfed the damage done by predecessors. New techniques are built on using system enhancements and feature upgrades of operating systems and applications against end users. Table 1-3 lists some of the newest evolutions in malware propagation methods.

Table 1-3 New Evolutions in Malware

The worms described in Table 1-3 use newer methods of infection and propagation and have been the source of significant outbreaks in IT history. By itself, Downadup infected over 9 million computers in less than 5 days. The discovery of Stuxnet showed how malware can be used to destroy an infrastructure. Evaluating the development of malware is important—from custom-targeted malware against organizations all the way down to simple client-side exploits that execute malicious code in order to remotely take control of victim computers. Although almost all of the popular examples are Microsoft Windows–focused malware that were reported in the press and printed in everyone’s morning paper, quantifying the entirety of the malware out there in the wild is still key.

All of the techniques used during malware’s initial evolutionary period can be seen conceptually in today’s malware releases. The damage these techniques have caused has only increased due to advances in network and routing services developed to ease the network administrator’s daily roles and responsibilities.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, malware authors began using techniques that have been increasingly difficult for forensics analysts and network defenders to identify and mitigate against. Historically, methods have ranged from quite traditional straightforward ones to highly innovative approaches, which cause many headaches for administrators around the world. In the following sections, we discuss one the biggest outbreaks and then move on to describing other samples and their functionality.

In 2007, we had the pleasure of experiencing one of the most elusive and eloquently implemented worms to date, known as StormWorm.

StormWorm

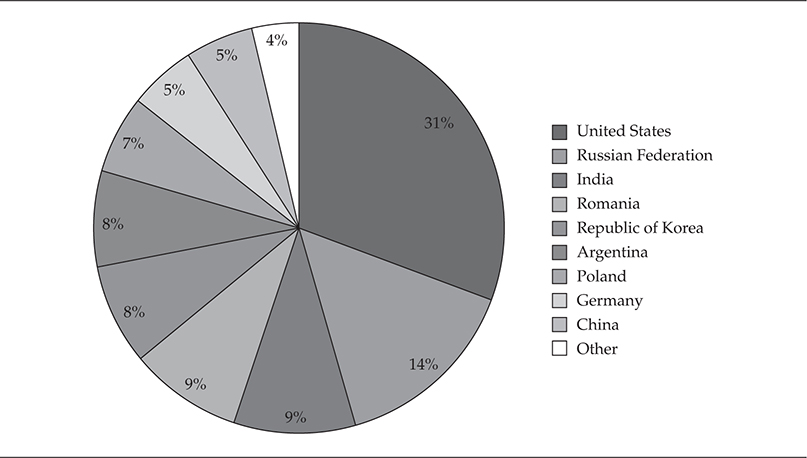

StormWorm was an emailer worm that utilized social engineering of the recipient from trusted friends using attached binaries or malicious code embedded within Microsoft Office attachments, which would then leverage well-known client-side attacks against vulnerable versions of Microsoft Internet Explorer and Microsoft Office, specifically versions 2003 and 2007. Originally discovered on January 17, 2007, StormWorm, a peer-to-peer botnet framework and backdoor Trojan horse, affected computers using Microsoft operating systems. StormWorm seeded a peer-to-peer botnet farm network, which was a newer command-and-control technique, in order to ensure persistence of the herd and increase the ability to survive attacks against its command-and-control structure because there was no single point of centralized control. Each compromised machine connected to a subset of the entire botnet herd, which ranged from 25 to 50 other compromised machines. In Figure 1-3, you can see the effectiveness of StormWorm’s command-and-control structure—one of the main reasons it was so difficult to protect against and track down.

Figure 1-3 StormWorm infection by country

In a peer-to-peer botnet, no one machine has a full list of the entire botnet; each only has a subset of the overall list, with some overlapping machines that spread like an intricate web, making it difficult to gauge the true extent of the zombie network. StormWorm’s size was never exactly calculated. However, it was estimated that StormWorm was the single largest botnet herd in recorded history, potentially ranging from 1 to 10 million victim systems. StormWorm was so large that several international security groups were reportedly attacked by the operators of StormWorm after they determined these groups were trying to actively combat and take down the botnet. Imagine national security groups and agencies brought down for days due to the massive power of this international botnet.

On infection, StormWorm would install Win32.Agent.dh, which inevitably led to the downfall of the initial variants implemented by the author. Some security groups felt that this flaw could be a possible pretest or weapons test by an unknown entity because the actual host code was engineered with flaws that could be stopped after some initial analysis of the binary. Keep in mind that numerous methods can be used to ensure malware is very difficult to detect. These methods include metamorphism, polymorphism, and hardware-based infection of devices, which are the most difficult to detect from the operating system. To date, no one knows whether or not the implemented flaws were intentional; this is still a mystery, and no consensus has been reached within the security community. If it had been a truly planned global epidemic, the author(s) would have probably taken more time to employ some of the more intricate techniques to ensure the rootkit was more difficult to discover or that it remained persistent on the victim host.

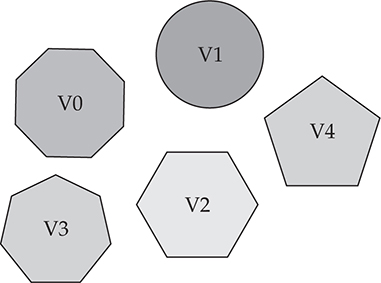

Metamorphism

Metamorphic malware changes as it reproduces or propagates, making it difficult to identify using signature-based antivirus or malicious-software removal tools. Each variant is just slightly different enough from the first to enable the variant to survive long enough to propagate to additional systems. Metamorphism is highly dependent on the algorithm used to create the mutations; if it isn’t properly implemented, countermeasures can be used to enumerate the possible iterations of the metamorphic engine. The following diagram shows how each iteration of the metamorphic engine is changed just enough to alter its signature to keep it from being detected.

Metamorphic engines are not new and have been in use for almost two decades. The innovative ways in which malware mutates on a machine have improved to make overall removal of the infection and even detection on the system quite difficult. Following are some case studies of infamous malware samples that employed metamorphism.

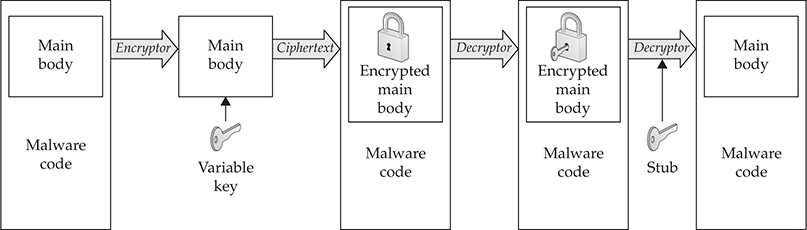

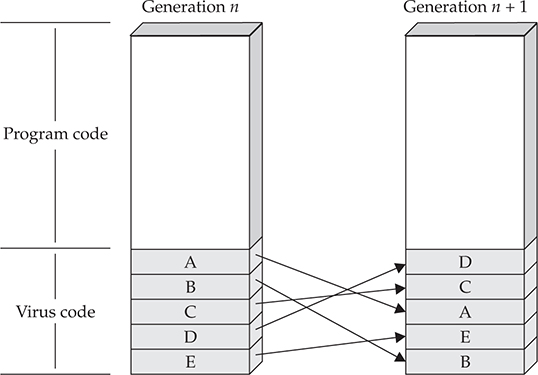

Polymorphism

Polymorphism refers to self-replicating malware that takes on a different structure than the original. Polymorphism is a form of camouflage that was initially adopted by malware writers in order to defeat the simple string searches antivirus engines employed to discover malware on a given host. Antivirus companies soon countered this technique. However, the encryption process that is the core of polymorphism has continued to evolve to ensure survivability of the malware on a host with security. The following illustration shows a typical process employed by a polymorphic engine. As you can see, each iteration of the malware is completely different. This technique makes it more difficult for antivirus programs to detect the iteration of the malware. More often than not, as will be covered in Chapter 7, antivirus engines look for the base static code of the malware in order to detect it, or in some cases, they use a behavioral approach and attempt to identify whether the newly added file behaves like malware.

Oligomorphic

This antidetection technique is generally considered a poor man’s polymorphic engine. It self-selects a decryptor from a set number of predefined alternatives. That being said, these predefined alternatives can be identified and detected with a fixed set of limited decryptors. In the following diagram, you can see the limitations of an oligomorphic engine and its effectiveness for use in real malware launches.

Obfuscation

Most malware seen on a daily basis is obfuscated in any number of ways. The most commonly found form of obfuscation is packing code via compression or encryption, which is covered in the next section. However, the concept of code obfuscation is vitally important to malware today. The two important types are host and network obfuscation in order to bypass both types of protection measures.

Obfuscation can sometimes be malware’s downfall. For instance, a writer implements obfuscation methods to such a severe state that network defenders can actually use the evasion technique to create signatures that detect the malware. In the next two sections, we’re going to discuss the two most important components of malware obfuscation: portable executable (PE) packers and network encoding.

Archivers, Encryptors, and Packers

Any number of publicly available utilities that are meant to protect data and ensure integrity can also be successfully used to protect malware during propagation, at rest, and most importantly, from forensic analysis. Let’s review, in order of evolution, archivers, encryptors, and packers, and how they are used today to infect systems.

Archivers In the late 1990s, ZIP, RAR, CAB, and TAR utilities were used to obfuscate malware. For the archiver to run, it typically needed to be installed on the victim host unless the writer had included the utility as part of the loader. This method became the least used due to the fact that in order for the malware to execute, it needed to be unpacked and moved to a location on the hard disk that could be readily scanned by the antivirus engine and removed. This method is dated and not used widely anymore because of the sophistication of antivirus scanners and their ability to scan multiple depths within archived files in a search for embedded portable executables.

Encryptors These are typically employed by most software developers to protect the core code of their applications. The core code is encrypted and compressed, which makes it hard to reverse (engineer) or to identify functions within the application by hackers. Cryptovirology is a synonymous term for the study of cryptography processes used by malware to obfuscate and protect itself in order to sustain survivability. Historically, malware implemented shared-key (symmetric) encryption methods, but once the forensics community identified this method, reversing it was fairly easy, leading to the implementation of public key encryption.

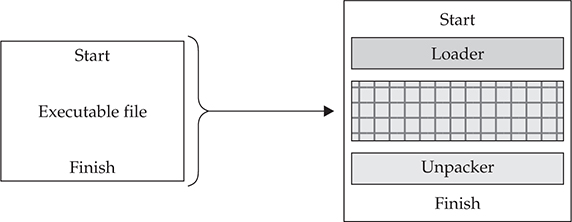

Packers Almost all malware samples today implement packers in some fashion in order to bypass security programs such as antivirus or anti-spyware tools. A packer is, in simple terms, an encryption module used to obfuscate the actual main body of code that executes the true functionality of the malware. Packers are used to bypass network-detection tools during transfer and host-based protection products. There are dozens of packers publicly and privately available on the Internet today. The private and one-off packers can be the most difficult to detect since they are not publicly available and not easily identified by enterprise security products. There is a distinct difference between packers and archiving utilities. Packers are not generally employed by the common computer user. Packers generally protect executables and DLLs without the need for any preinstalled utility on the victim host.

Just like attackers’ skill levels, packers also have varying levels of sophistication that come with numerous functionality options. Packers often protect against antivirus protections and also increase the ability of the malware to hide itself. Packers can provide a robust set of features for attackers such as the ability to detect virtual machines and crash when within them; generate numerous exceptions, leveraging polymorphic code to evade execution prevention; and insert junk instructions that increase the size of the packed file, thereby making detection more difficult. You will typically find ADD, SUB, XOR, or calls to null functions within junk instructions to throw off forensic analysis. You will also find multiple files packed or protected together such as the executable files; other executable files will be loaded in the address space of the primary unpacked file.

The following is a simple example of a packer’s process:

The most powerful part of using a packer is the malware never needs to hit the hard disk. Everything is run as in-process memory, which can generally bypass most antivirus and host-based security tools. With this approach, if the packer is known, an antivirus engine can identify it as it unpacks the malware. If it is a private or new packer, the antivirus engine has no hope of preventing the malware from executing; the game is lost and no security alerts are triggered for an administrator to act on. In Figure 1-4 you can clearly see the increase in the number of packers identified over the past years by the forensic community.

Figure 1-4 Packers commonly used in executables

Network Encoding

Most network security tools can be bypassed when using network encoding. Today almost all enterprise networks allow HTTP or HTTPS through all gateways so encoded malware can sneak past boundary protection systems.

Technically speaking, handling encoding/decoding is nontrivial. Because traffic flow needs to be fast, however, decoding the traffic would create such performance degradation that usability would be affected. Encoding to bypass network security is indeed being done, but let’s not forget that it is done based on the premise that network analysis tools don’t have the luxury of analysis because of their impact on usability.

The following is a very common method of network encoding.

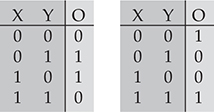

XOR and XNOR XOR is a simple encryption process that is implemented with network communications in order to avoid obvious detection by network security devices. You would typically find an XOR stream hiding within a protocol such as Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). This way, if an IDS analyst performed only a simple evaluation, the traffic would seem encrypted, but when deep packet inspection was implemented, the analyst would notice the stream was not actual SSL traffic.

XOR is a simple binary operation that will take two binary inputs and output 0 if both inputs are the same and 1 if both inputs are not the same. XNOR operates in the same, but opposite, way. So, if both inputs are the same, the output is 1, and if both inputs are different, the output is 0. When the malware is ready to execute, it will run the binary through the reverse process to access the data and run as it was programmed to do. XOR and XNOR are very simple engines that quickly change information at rest or on-the-fly to help evade detection methods.

Most intelligent malware writers do not employ archivers for encoding anymore since most enterprise gateway applications can decode any given number of publicly available archiving utilities. It is possible to implement fragmented transfers or “trickling” of archive-protected malware into a network. If any part of the malware is identified, however, it would be cleaned or removed from the system, essentially crippling the malware so it can’t be assembled into a complete state as intended by the writer.

Dynamic Domain Name Services

Dynamic Domain Name Services (DDNS) is by far the most innovative advancement for the bad guys, even though it was originally meant to be an administrative enhancement so enterprise administrators could add machines to the network quickly. Microsoft implemented it in their Active Directory Enterprise System as a way to rapidly inform other computers on the network about machines that were coming online or going offline. However, DDNS has enabled malware to phone home and operate anonymously without fear of attribution or apprehension. DDNS is a domain name system in which the domain name to IP resolution can be updated in real time, typically within minutes. The name server hosting the domain name is almost always holding the cache record of the command-and-control server. But the IP address of the (compromised/victim) host could be anywhere and move at any moment. Limiting the caching of the domain to a very short period (minutes) to avoid other name server nodes from caching the old address of the original host ensures the victim resolves with the writer’s hosted name server.

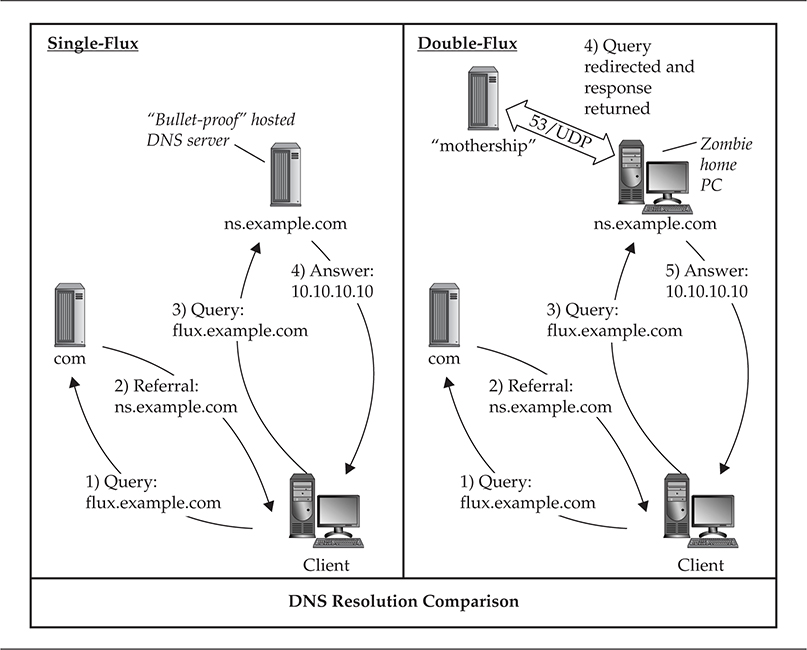

Fast Flux

Fast Flux is one of the most popular communication platforms in use by botnets, malware, and phishing schemes to deliver content and command-and-control through a constantly changing network of proxied compromised hosts. A peer-to-peer network topology can also implement Fast Flux as a command-and-control framework distributed throughout numerous command-and-control servers and passed along like a daisy chain without fear of attribution. Fast Flux is highly similar to DDNS but is much faster and much harder to catch up with if you are trying to catch the writer or mastermind behind the malware. StormWorm, which we covered earlier, was an early malware variant that made best use of this technique. Figure 1-5 illustrates the two forms of Fast Flux: Single-Flux and Double-Flux. In this figure, you see a simple process for both Single- and Double-Flux between the victim and the lookup process for each method.

Figure 1-5 Single-Flux and Double-Flux

Single-Flux

The first form of Fast Flux generally incorporates multiple nodes within a network to register and deregister addresses. This is typically associated with a single DNS A (address) record for a single DNS entry and produces a fluctuating list of destination addresses for a single domain name, which could be from a list with hundreds to thousands of entries. Typically Single-Flux DNS records are set with very short time-to-live (TTL) to ensure the records are never cached and the addresses can move about quickly without fear of being recorded.

Double-Flux

The second form of Fast Flux is much more difficult to implement. This implementation is similar to Single-Flux; however, instead of a network of multiple hosts registering and deregistering DNS A (address) records, the multiple hosts are name servers that register and deregister NS records that produce lists for the DNS zone. This ensures the malware has a layer of protection and survivability if one of the nodes is discovered. You will generally see compromised hosts acting as proxies within the network of name servers, embedding a web of proxies throughout compromised hosts in order to protect the identity of the malware network where instructions are executed. Due to the number of implemented proxies, protecting the malware writer is completely possible, which increases the survival rate of the malware system even beyond IP blocks put in place to prevent access of compromised hosts to the command-and-control point, which can come from multiple sources.

Just remember, an attacker only needs one vector to own you, and a defender needs to be aware and protect against every possible vector. The odds are stacked in whose favor? Vigilance is a must in this field…

The features added to routing and network services over the past decade to ease the administrators’ workload are being used against them to propagate malware for monetary purposes. There isn’t much protection from most of these techniques beyond holistic training and educating your users so they don’t open emails or attachments from even trusted sources without truly vetting them by the trusted sender. That it has come down to this is sad, but today your users are your last line of defense. If they aren’t trained to perform simple analytical functions, your network is lost due to the propagation methods we’ve been discussing. It is important to note that users today do not have the tools available that would allow them to quickly verify domain names and/or trusts from domain names received in email attachments. There are enterprise tools available to authenticate trusts; however, the overall time needed to perform validation of trusts would be cost prohibitive to daily business operations.

Now let’s get to the fun section of this chapter…

Malware Propagation Injection Vectors

This section introduces actual methods for delivering malware to victims in order to actually get into their computers. There are many active ways to send or deliver malware. There are also passive infection methods that are dependent on social engineering or on the victim accessing the content where the malware is stored. These methods are in use every day, and this section will hopefully provide some insight into a vital part of the overall malware lifecycle: making you a victim.

Have you ever received an email with an attachment you were not so sure of, but on first glance thought interesting enough to open? Over the past years, electronic mail has been the bane of network administrators and the open gate for all bad guys who want to enter your network. It was true in the 1990s and is so much more the case today. From a security administrator’s perspective, you want to block as much as humanly possible. From a network operation’s perspective, you want to ensure business continuity as much as possible, which means leaving some doors open. Email is one of the two always-open ways into your network, with malicious websites being the second. We will cover websites in the next section of this chapter. Since 2007 worm propagation through direct machine-to-machine infection is basically dead due to the strengthening of enterprise security measures and boundary protections.

Historically overlooked by administrators, but never by malware writers, is the last bastion and strongest approach into the network—the “users.” They are how you get through the hard shell of any network. The most common email-based malware injection techniques contain embedded exploits that use techniques also known as client-side exploits. Social engineering is the core foundation for all email-based attacks, which goes back to training your staff. However, this still hasn’t quite sunk into the minds of leaders of some organizations.

Do you still feel comfortable with your users opening any email sent to them? Are there times when you want to tie up users on your network with duct tape or put a layer of plate glass between them and the keyboard, only allowing a small pole for them to push one key at a time to increase the delay between breakouts? The point is that you cannot restrict your network users so far as to hinder their daily business processes. If you do, they will certainly find a way to bypass your security measures. So there will always be a fine line between operations and security and user training and awareness.

Email Threats

Email Threats

This section highlights one of the two most arduous delivery mechanisms to defend against. In today’s business world, every member of the staff is typically provided a corporate or business email address to conduct business with external organizations or individuals. This alone is a huge task for security administrators and an even larger burden of trust on the shoulders of organizational stakeholders who need to constantly train and monitor their staff to ensure they understand and are aware of the threats. Some of these methods will be very familiar if you fight malware for a living, but some may not be.

Social Engineering of Trusted Insiders Social engineering as it relates to malware is something that has been and will be covered numerous times throughout this book because social engineering is by far the single most powerful infection vector for malware writers. Ensuring a trusted insider does not recognize that he or she is reading a generic “dancing bear” email or a highly sophisticated and “targeted” email—both of which are designed to fool the reader into opening or executing the content and/or attachment in order to take control of the recipient’s system—is the most important goal of the criminal. Once the criminal has socially engineered the victim, the attacker can use almost any method to exploit the victim. Finally, the most important point for security administrators is to truly understand and be aware that this method requires that you be on point and ensure security programs include mandatory training of incoming employees.

Email as Malware Backdoor This technique was first seen during the summer of 2008—malware that was intelligent enough to download its own Secure Socket Layer Dynamic Link Libraries (ssl.dll), which then enabled the malware to open its own hidden covert channel to external public web-mail systems (Yahoo!, Hotmail, Gmail, and so on). What did this mean? It meant communications from your internal systems heading to public personal email systems could be malware logging in to receive either new updates or instructions, or it could be sending data from your internal network. This method has been spotted several times during the course of engagements with some organizations that have been attacked.

Email Attack Types: Microsoft Office File Handling

Email Attack Types: Microsoft Office File Handling

Typically, this is the second line of injection right after social engineering. This method implements various exploit code embedded in a myriad of Microsoft Office products. To date Microsoft Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and Outlook have been the primary focus. However, several others have been targeted for use as a way to quickly compromise a system immediately after a file attachment from an email has been executed. The most important thing to remember is this type of attack can be employed with Adobe and almost any other local application running on your system that is used to read and/or open an attachment. Here we’ve included just one of hundreds of examples of this type of attack for your reference:

• Name Microsoft Office Memory Corruption Vulnerability

• CVE CVE-2015-2477

• CWE ID 119

• Microsoft Security Bulletin MS15-081

• Description A vulnerability that allows remote attackers to execute arbitrary code via a crafted document

• Affected Microsoft Office 2007 SP3, Office for Mac 2011, Office for Mac 2016, and Word Viewer

• Solution The vulnerability has been fixed, and users should apply patches from https://technet.microsoft.com/library/security/ms15-081.

Countermeasures for Email Threats

Countermeasures for Email Threats

In the following sections, we discuss some of the most powerful countermeasures against email threats today. However simple they may seem, they are terribly important.

Rule 1 Understanding what you are receiving is the most important step toward protecting yourself from malware infection through email. Is the file you received a known carrier of malware and able to take control of your system? Ensure your users enable View File Extensions.

Rule 2 Never open an executable file type from anyone unless you expressly requested that file, especially since malware will typically come from someone you know. Have friends who send you executables actually rename the file extension before transit, for example, rename .exe to .ex_ or .zip to .zzz. More importantly refer to Rule 3 if there is any question about the attachment. One thing you should remember is that this method only works when dealing with email systems that do not perform file header checks that identify the file type.

Rule 3 Always patch your systems whenever possible. We highly recommend that home users configure their system to check for updates at least once a day. Typically the late evening or early morning is the best time of day so as to not conflict with other applications and/or daily business operations. For enterprise users, we highly recommend the Microsoft Windows Server Update Services (WSUS). This suite can push out updates across your enterprise from a single server, be set to check for updates several times a day, and only requires download from a single point. This avoids having your entire enterprise attempt to download from Microsoft once a day and all of a sudden create a bottleneck on your network at various times, depending on the locations of your enterprise offices.

Rule 4 Delete the attachment if you do not need it.

Malicious Websites

Client-side attacks have been the buzz for the past few years. The bad guys have realized users aren’t inherently well trained and are thus susceptible to social engineering. We’re not saying users aren’t smart; they’re just undertrained.

Let’s discuss the concept of the contagion worm for a moment. In the paper, “How to 0wn the Internet in Your Spare Time,” which can be found at http://www.icir.org/vern/papers/cdc-usenix-sec02/, the writers discuss numerous propagation techniques, but the most pivotal portion of the paper is the discussion of the contagion worm concept. The concept of the contagion worm is similar to “the perfect storm” in terms of being a worm that can hop from server to clients so seamlessly that it could feasibly infect millions of machines with ease in a matter of hours when executed correctly.

Seems quite devastating, doesn’t it? This method is highly effective and could potentially cause millions of Internet users to fall victim to malware infections without their knowledge for prolonged periods of time.

Malicious Website Threats

Malicious Website Threats

Malicious websites are a serious problem because any website can be malicious; even some of the most famous websites around the world have fallen prey to malicious entities who loaded malware on the site, waiting for millions of unsuspecting users to visit the site and immediately be infected by a Trojan dropper. Now, most of the time, you will find 1 in 5 sites are in danger of being infected by malware and turned into malicious websites. On the other hand, 1 in 20 websites actually have some form of malicious infection, embedded redirect, and/or link to an infected site. What does this mean for you? Your users surf the Internet every day and check their personal, professional, and social media websites, correct? This opens up your enterprise and your users’ home networks to threats, which can propagate into your enterprise networks if your VPN is not properly configured to filter unauthorized ports and protocols.

A serious issue to address is the need to properly configure your VPN when users are coming in from outside the “safety” of your internal network. A vast array of malicious content, which can range from a backdoor, Trojan-PSW, Trojan-Dropper, Trojan-Clicker, and/or Trojan-Downloader, can open the door to any number of remotely accessible variants of malware that are meant to be used over a long duration. Bottom line is web or HTTP filtering is highly recommended when you are the one at risk if something malicious breaks out.

Targeted Malicious Websites You need to be aware that the hacking community isn’t a stupid bunch as most world leaders believe. There are attackers who actually identify what specific sites a group of users on a network utilize or visit on a daily basis, and they simply focus their efforts on compromising those specific sites to ensure they can quickly load some client-side exploits; then their prey falls quickly and easily without anyone being the wiser. Not to mention this threat is the easiest to execute because any perimeter network security device will not be alerted to the malicious user’s approach and attack….

A very good example of this is the waterhole attack. Download the paper from http://blogsdev.rsa.com/wp-content/uploads/VOHO_WP_FINAL_READY-FOR-Publication-09242012_AC.pdf to read more about it.

Malicious Website Attacks

Malicious Website Attacks

The basis for website attacks are client-side exploits; it’s that simple. Your computer visits a site and downloads the site code, which is then executed locally. It’s all hidden in the packets of your HTTP session and can typically be embedded and obfuscated in ways that firewalls, NIDS, and antivirus can’t catch in time. A client-side exploit is an elegant, straightforward, and direct way into your network without being noticed until days, weeks, and sometimes even several months later when you realize the enterprise system is behaving oddly. Almost all of the attacks are pointed at your Internet browser; no matter which you use—Firefox, Chrome, Safari, and many others—you’re not safe.

Countermeasures for Malicious Website-Based Malware

Countermeasures for Malicious Website-Based Malware

Training Users need to understand that surfing the Internet can bring malware into your enterprise. More often than not, in today’s world, email links sent to a user perform a client-side exploit when clicked and then load various types of malware onto the host. This attack can primarily be prevented through due diligence and education.

Anti-Spyware Modules With the release of Windows XP, Microsoft introduced their anti-spyware tool—Microsoft Anti-Spyware—which was part of the acquisition of GIANT Software Corporation in 2002. It was actually a good tool, which was “free” to verified and licensed users of Windows XP. Microsoft later released Windows Defender, which is also a good tool. However, these tools are only as good as the system they are protecting. A vulnerable system will bring Windows Defender to its knees, preventing it from protecting the operating system from further infection. Bottom line, though—these tools can help, and we need all the tools we can get.

Web-Based Content Filtering Some enterprise network tools such as web or URL filtering are helpful in the fight against malicious websites, but they are only as good as the bad-IP lists, scanning algorithms, and signatures to identify attack and malware variants. The bane of every signature-based system is having all of the signatures needed to identify the malicious activity and/or being fast enough to handle the large amount of enterprise-level traffic.

Phishing

Phishing is a tried-and-true method of getting information from a target entity. It still has the attention of anyone working in any IT-related industry. One of your users at work or at home gets an email that seems legitimate but in actuality is a cleverly crafted façade to lure the user into clicking a link or providing personal or professional information that can disclose enough details to allow an attacker to steal the identity of that person or get more information on that person’s corporation in order to gain access to a private or public information resource and thus cause more damage or make a profit.

A cleverly crafted phishing email can be a nightmare for the target organization and for the security industry tasked to protect it. Phishing can lead to direct identity theft or a URL with malicious code (client-side attacks), which brings us back to the previous section.

Now you would probably like to know, “How do I prevent phishing of my users?”

Training! Train your staff to identify who is sending an email; if it is legitimate and if there is an embedded URL or attachment, have the staff call the sender to verify before opening the email. Most international organizations preach that to their staff. It only takes a moment and could honestly save your organization millions in remediation.

Email malware propagation is the most effective phishing method. Email phishing concepts have been in use since the mid-1990s, beginning most notably within the America Online network. However, spear-phishing, a more targeted phishing method, has continued to turn up over the past few years.

Threats from Phishing

Threats from Phishing

There are two primary threats that you really need to give attention to when dealing with phishing: the loss of personal information and the loss of corporate information that can be gleamed from you or your employees through phishing schemes, which can be beyond damaging. There is a third threat, but it also runs in line with malicious websites, which we just covered. These threats don’t seem to be much at first—a fake setup that looks official, tricking you into submitting information. Those who do fall for the schemes always lose more than the few minutes it took to fill out the form, however.

Now imagine this—you just spent 10 to 15 minutes filling out a form that asked you for your information (identification, banking, health, professional, corporate, and so on). It didn’t get you anywhere but a dead POST submit link (which is the final Submit button found on standard web forms), and now all of that information is floating in the wild of cyberspace and in the hands of numerous entities whose goal is to use that information for any number of purposes, none of which are in your best interests. Sometimes simply clicking buttons on a malicious website is all the approval a computer needs to begin loading malware in the background while you are filling out a form or waiting for the submittal process to finish.

Attacks from Phishing

Attacks from Phishing

There are two primary types of phishing attacks: active and passive.

Active Phishing These schemes are email based and typically ask a user to click a link upon reading the email, which takes the user to a forged site that looks similar to a real major corporation’s site. You typically see active phishing schemes set up to mirror large corporations.

Ask your personal or corporate bank if it has any current public warnings of phishing schemes targeting its members. You can also check with large corporations, such as eBay, Amazon, Apple, Yahoo!, Facebook, and even Microsoft.

A user generally trusts these sites since he or she probably has an account or owns the software that company makes. More importantly, these phishing schemes will ask for account information in order to steal the customer’s credentials and then use that account for their own nefarious purposes. Active phishing can also be seen in free advertisements, where a user receives an email offering “a free $500 gift certificate” if he or she fills out a form and submits the information and even possibly supplies the email addresses of several friends.

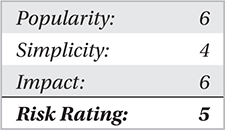

The following is an example of an active phishing scheme:

Passive Phishing These schemes are typically idle sites that are tied to search engine queries and wait low-and-slow for trusting users to happen on them. Users are then enticed with a hollow front-end of data and asked to fill out an application and then click Submit. After clicking Submit, they are typically given the runaround with the same page and end up frustrated to no end and leave the site. This passive approach can have two results. One, the information provided is used for another malicious purpose; or two, the site actually executes the malware when the user clicks the Submit button and then installs itself on the user’s computer. The latter is covered earlier in the “Malicious Websites” section, but this is still another way malware is delivered and piggybacked by other forms of malicious code.

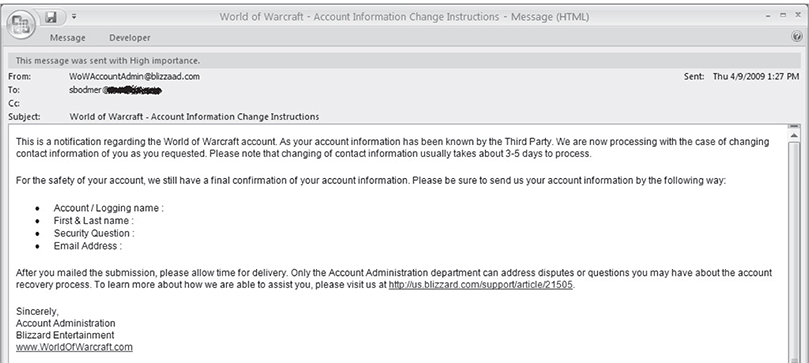

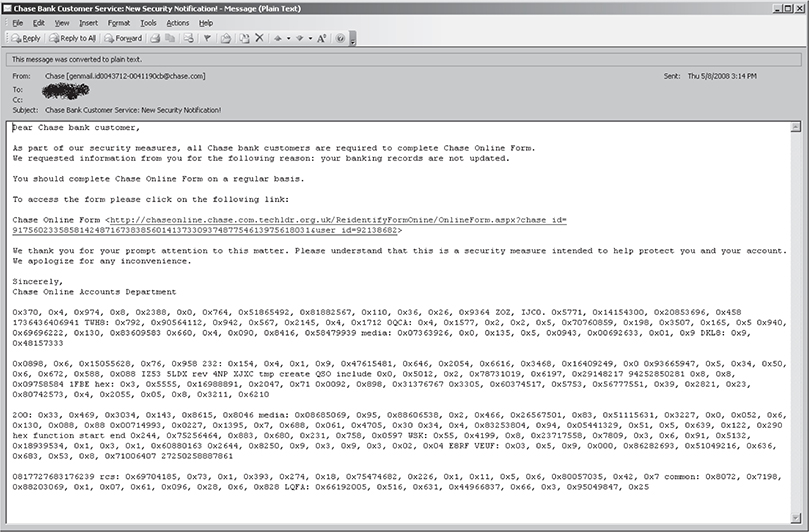

The following emails are some examples of passive phishing schemes.

Countermeasures for Phishing

Countermeasures for Phishing

Training Users need to understand that when they surf the Internet they can bring malware into your enterprise. More often than not, in today’s world email links sent to a user will lead to a site where he or she is asked to input personal or corporate information that can be used to steal information. This attack can be prevented through due diligence and education.

Anti-Phishing Modules Since the release of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer 7.0, anti-phishing modules and pop-up blockers were introduced as fully integrated modules to provide further protection for your systems. However, most end users unfortunately disable this service to prevent an impact to business operations and/or personal quality of life during office hours.

Awareness Campaigns You can train your staff about phishing attacks by hiring a group to perform this activity in a nonvolatile way, thus training them to identify potential phishing attempts in the future.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P)

This technology reared its ugly head in the late 1990s. It was initially a godsend to most end users, and then some crafty-minded individual or group figured out they could release malware in a P2P file, and upon execution of that file after download, they owned you. In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled it was legal for media companies to employ malware in copyright material and deploy it onto P2P networks to take down machines of illegal downloaders several months after the bad guys started doing this for financial gain. It was an impressive feat that amazed us at the time.

Today, the concept of peer-to-peer networks has far surpassed the initial model primarily employed for decentralized information dissemination and Morpheus-style file-sharing networks. Now malware implements peer-to-peer communications in order to spread botnets and worms to historically unpredicted proportions. Years ago security experts had predicted that new advances in malware would cause global epidemics, and we are now at a level that those revelations have come true. Peer-to-peer malware has been one of the hottest methods for employing malware on a massive scale without fear of attribution or prosecution by authorities. The power of implementing a peer-to-peer malware network is in its raw ability to sustain survivability against the need for any single point of command and control. Don’t forget that P2P file-sharing networks are also huge proprietors of malware hidden within illegally distributed files on networks such as BitTorrent, Kazaa, and many others. This highly successful network architecture has paved the way for attackers to implement a similar command-and-control structure.

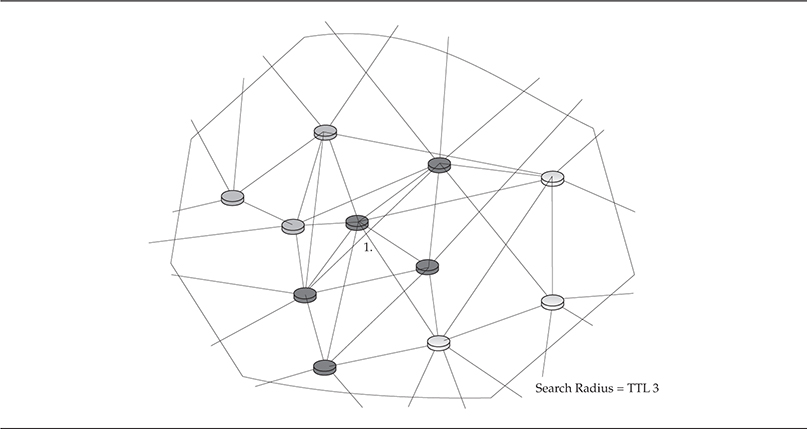

For example, out of a 1000-host peer-to-peer malware network, you may have a dozen command-and-control (C2) servers. Now each of these command-and-control servers has a subset of each of the 1000 hosts under its control. Let’s say 75 to 90 hosts report to each command-and-control server. Now each subset has at least a small knowledge (2 to 6 hosts) of another subset within a very small time-to-live radius (TTL = 3). If six hosts sitting on the same segment report to different C2 servers, each would notionally have a list of every host within its subset and then some additional hosts within the TTL radius. This method of communication ensures all C2 servers are aware of the entirety of the network without having direct access to it or network defenders having direct knowledge of the entire network. Figure 1-6 is a diagram of the C2 structure of a malware peer-to-peer network. If you look at host 1 and watch the communication paths, it would ship out information to every host within three TTLs, crossing over several subsets where each of the updates is passed along to its respective C2 server.

Figure 1-6 P2P common architecture

Threats from P2P

Threats from P2P

We break down P2P threats into two categories—operational and legal—both of which have severe implications for your home and enterprise networks.

Operational Not only does P2P open up numerous ports on your network, it can open up your network files and information to millions of other P2P users around the world. Some of those users are harmless, and some are set up on P2P just to spread malware and infection across the globe. With the latter, your information can be infected by the malware upon execution. Now, the application and ports are open on your network and act as a doorway for “anyone” to waltz right in and do whatever he or she wants to your network. These methods essentially have a domino effect of one infected file infecting a system and so on and so on. You get the point.

Legal I’m not a lawyer and will not pretend to be, but we are all aware of the international laws that have been put into place over the past decades to protect corporation copyright and licensing. The emergence of P2P has cost the international software and media market billions of dollars and has negatively impacted markets across the world. So, in short, if your users or family are using P2P networks to download files within your enterprise, you are more than likely compromised and, at any moment, can be identified by any number of legal bodies scouring the P2P networks looking for IP addresses where their legal jurisdiction can enact penalties that range into the millions of dollars.

Attacks from P2P

Attacks from P2P

Operational concern stems from controlling the use of P2P applications within your networks and the associated file execution of P2P files, which is the mission-critical issue you need to address. Bottom line, if users are able to install, download, and execute P2P files, you’re not going to like what your executives have to say about your performance.

Countermeasures for P2P

Countermeasures for P2P

Training Users must understand that installing P2P applications at home or at the office can lead to enormous malware infections. The use of P2P as a backbone to spread malware has been in use since the late 1990s through Morpheus, Kazaa, Gnutella, and many others, easily available for download over the Internet. P2P applications come and go, and those that can be downloaded today such as Transmission-qt, Vuze, and Deluge, among others, are open to abuse by attackers. Users need to be trained explicitly on both the legal and technical implications of using P2P applications, especially when using P2P applications at home on the same PC they use to connect to your VPN and thus into your enterprise. That four-letter word that everyone loves—“free”—is not always as free as it appears. P2P networks do have legitimate uses, but more often than not, hackers will abuse the P2P trust by embedding or hiding malware in freely traded files, and users will mistakenly download and infect themselves because they don’t fully understand the threats involved when downloading from these networks.

Corporate Policy Corporate policy is also very important in protecting your enterprise. Users who are aware of a gap in corporate policy could use this to their advantage by playing dumb. Even more critical, your corporate policy should explicitly state what could happen if an employee is caught running a P2P application on the network—especially when a professional company has to assume any liability when someone downloads illegal and potentially malicious files onto corporate systems.

Worms

In the section, “Significant Malware Propagation Techniques,” we covered most of the industrywide malware epidemics and their propagation techniques. However, we did not discuss the overall strategies of worms and their use beyond delivery points; we didn’t really get into what the worms can do from an enterprise-impact perspective. Worms are simply the propagation layer of the writer’s end goal. In the next chapter, we’ll discuss the functionality of malware in depth, so sit back and keep reading so you can better understand the functionality of the malware once it is on your system.

Threats from Worms

Threats from Worms

Worms were the bane of every network and security administrator when worm outbreaks were exploding. StormWorm, which was discussed earlier, was by far the most dangerous and effective worm developed to date. It leveraged a Trojan-Dropper, rootkit, and a P2P communication structure—an amazing and beautiful “almost” perfect cyberstorm (and so rightfully named StormWorm). The biggest threat from worms in and of themselves was the myriad of functionality that was encoded in them and especially their ability to propagate throughout the Internet and enterprise networks within hours.

Conficker, another computer worm, victimized millions of Microsoft Windows users. Infected machines became part of a botnet used mostly for stealing financial data and other information from the compromised system. It was also known for its domain generation algorithm (DGA); each day it generated different domains that it used to communicate with its command and control.

Attacks from Worms

Attacks from Worms

Typically, you see several propagation techniques implemented within a worm. Social engineering causing file execution (client-based) injection, web-based infection (client-based), network service exploitation, and email-based propagation have been the most commonly used methods. All of these attacks from worms have been so quick to execute and propagate that you need to better understand the methods that a worm may itself employ in order to propagate further. The newer the worm variant, the more sophisticated and fluid the propagation methods have become across a network. And although worms aren’t the issue they were previously, they still cause very bad headaches.

Countermeasures for Worms

Countermeasures for Worms

Strong Network Protections There aren’t any tools available that are 100 percent effective in protecting your system from worms. Unfortunately, you need to employ a layered approach and use several tools to help identify and proactively defend your network resources. Typically, a mixed IPS, such as an exact and partial fingerprint-matching system, is needed at your network’s most crucial data ingress and egress points, in addition to daily updated antivirus engines on your network.

Strong Host Protection There are several HIPS tools available. In Chapter 9, we’ll cover several of the best-of-breed tools to help identify and prevent the propagation of worms across your network.

Summary

Overall, the propagation techniques we have covered are extremely difficult to defend against and even more difficult to identify beyond traditional postmortem methods. Any combination of the discussed techniques can and have caused global epidemics that have sent the world into temporary chaos. Just the right combination of any of these techniques is incredibly difficult to stop. The only technologies in use today that can even come anywhere near being close to identifying these techniques are behavior-based intrusion protection systems and/or honeynet technologies that see all malicious activity in real time.

As you can see, the malware of today is much more efficient and well planned, which inevitably comes back to money. Most of the malware released is developed from a pool of resources and is just as well funded as antivirus and security firms. More importantly, it “never” fails that an unproven concept will be proven within 18 months of any security researcher predicting the next big wave of malware.