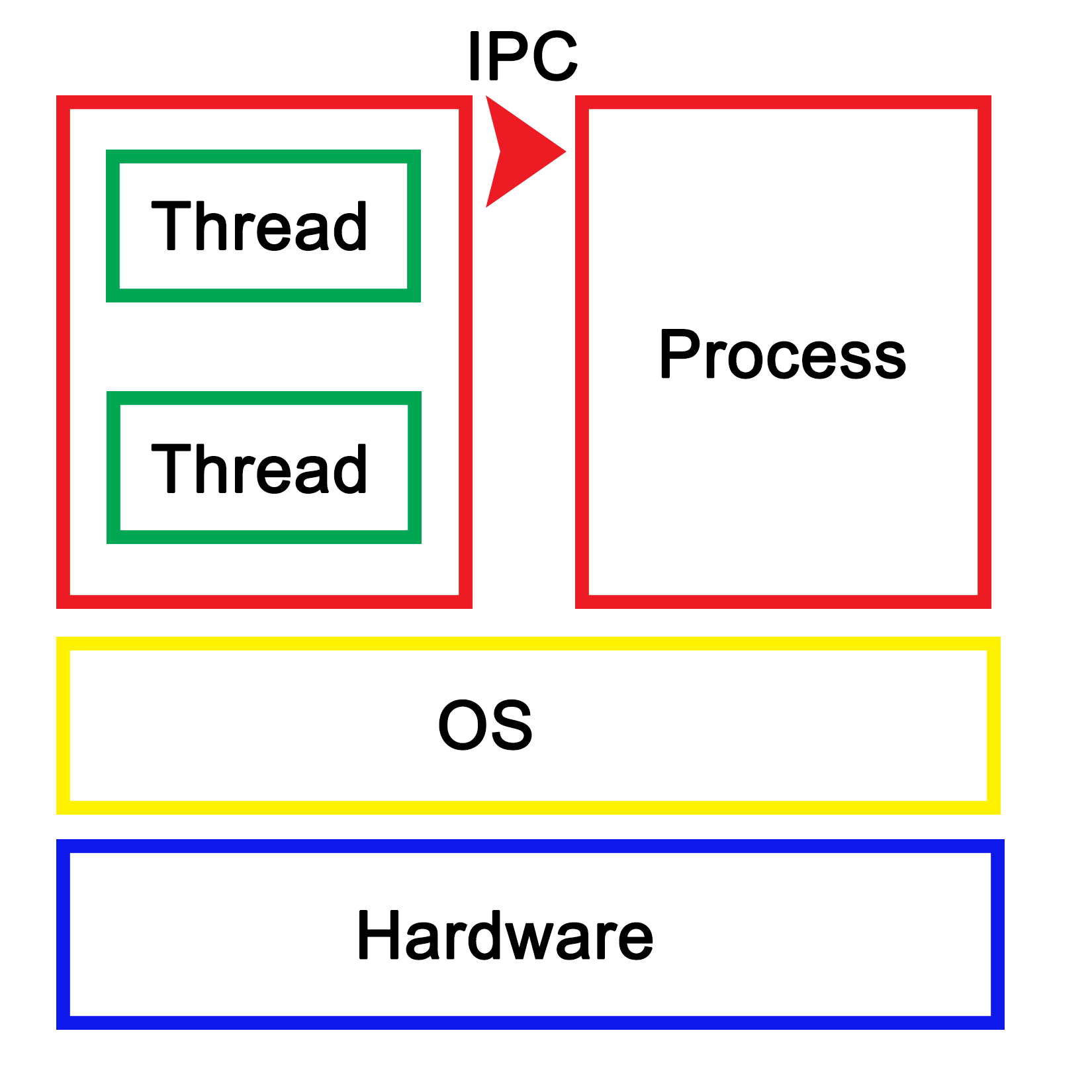

Essentially, to the operating system (OS), a process consists of one or more threads, each thread processing its own state and variables. One would regard this as a hierarchical configuration, with the OS as the foundation, providing support for the running of (user) processes. Each of these processes then consists of one or more threads. Communication between processes is handled by inter-process communication (IPC), which is provided by the operating system.

In a graphical view, this looks like the following:

Each process within the OS has its own state, with each thread in a process having its own state as well as the relative to the other threads within that same process. While IPC allows processes to communicate with each other, threads can communicate with other threads within the process in a variety of ways, which we'll explore in more depth in upcoming chapters. This generally involves some kind of shared memory between threads.

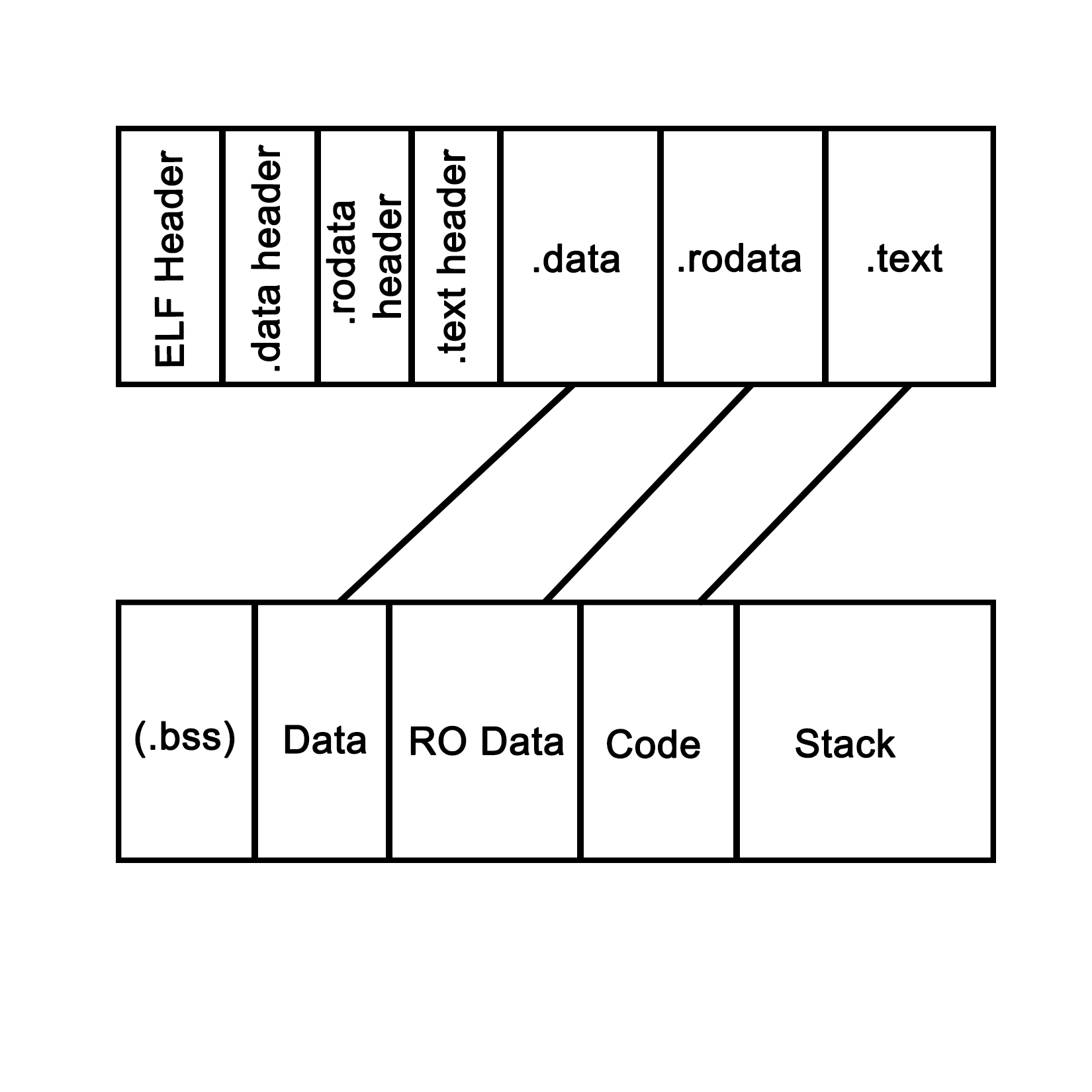

An application is loaded from binary data in a specific executable format such as, for example, Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) which is generally used on Linux and many other operating systems. With ELF binaries, the following number of sections should always be present:

- .bss

- .data

- .rodata

- .text

The .bss section is, essentially, allocated with uninitialized memory including empty arrays which thus do not take up any space in the binary, as it makes no sense to store rows of pure zeroes in the executable. Similarly, there is the .data section with initialized data. This contains global tables, variables, and the like. Finally, the .rodata section is like .data, but it is, as the name suggests, read-only. It contains things such as hardcoded strings.

In the .text section, we find the actual application instructions (code) which will be executed by the processor. The whole of this will get loaded by the operating system, thus creating a process. The layout of such a process looks like the following diagram:

This is what a process looks like when launched from an ELF-format binary, though the final format in memory is roughly the same in basically any OS, including for a Windows process launched from a PE-format binary. Each of the sections in the binary are loaded into their respective sections, with the BSS section allocated to the specified size. The .text section is loaded along with the other sections, and its initial instruction is executed once this is done, which starts the process.

In system languages such as C++, one can see how variables and other program state information within such a process are stored both on the stack (variables exist within the scope) and heap (using the new operator). The stack is a section of memory (one allocated per thread), the size of which depends on the operating system and its configuration. One can generally also set the stack size programmatically when creating a new thread.

In an operating system, a process consists of a block of memory addresses, the size of which is constant and limited by the size of its memory pointers. For a 32-bit OS, this would limit this block to 4 GB. Within this virtual memory space, the OS allocates a basic stack and heap, both of which can grow until all memory addresses have been exhausted, and further attempts by the process to allocate more memory will be denied.

The stack is a concept both for the operating system and for the hardware. In essence, it's a collection (stack) of so-called stack frames, each of which is composed of variables, instructions, and other data relevant to the execution frame of a task.

In hardware terms, the stack is part of the task (x86) or process state (ARM), which is how the processor defines an execution instance (program or thread). This hardware-defined entity contains the entire state of a singular thread of execution. See the following sections for further details on this.