![]()

BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI

![]()

BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI

Copyright © 2017 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: July 2017

Production reference: 1270717

ISBN 978-1-78712-170-6

|

Author Maya Posch |

Copy Editor Sonia Mathur |

|

Reviewer Louis E. Mauget |

Project Coordinator Vaidehi Sawant |

|

Commissioning Editor Aaron Lazar |

Proofreader Safis Editing |

|

Acquisition Editor Chaitanya Nair |

Indexer Francy Puthiry |

|

Content Development Editor Rohit Kumar Singh |

Graphics Abhinash Sahu |

|

Technical Editors Ketan Kamble |

Production Coordinator Nilesh Mohite |

Maya Posch is a software engineer by trade and a self-professed electronics, robotics, and AI nut, running her own software development company, Nyanko, with her good friend, Trevor Purdy, where she works on various game development projects and some non-game projects. Apart from this, she does various freelance jobs for companies around the globe. You can visit her LinkedIn profile for more work-related details.

Aside from writing software, she likes to play with equations and write novels, such as her awesome reimagining of the story of the Nintendo classic, Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and the survival-horror novel she recently started, Viral Desire. You can check out her Scribd profile for a full listing of her writings.

Maya is also interested in biochemistry, robotics, and reverse-engineering of the human body. To know more about her, visit her blog, Artificial Human. If there's anything she doesn't lack, it has to be sheer ambition, it seems.

Louis E. Mauget learned to program a long time ago at the Michigan State University as a physics major learning to use software in designing a cyclotron. Later, he worked for 34 years at IBM. He went on to work for several consulting firms, including a long-term engagement with the railroad industry. He is currently consulting for Keyhole Software at Leawood, Kansas.

Lou has coded in C++, Java, JavaScript, Python, and newer languages, as each was conceived. His current interests include reactive functional programming, containers, Node JS, NoSQL, geospatial systems, mobile, and so on, in any new language or framework.

He occasionally blogs about software technology for Keyhole Software. He has coauthored three computer books and authored two IBM DeveloperWorks XML tutorials and a WebSphere Journal LDAP tutorial. Lou co-wrote several J2EE certification tests for IBM. He has also worked as a reviewer for Packt Publishing and others.

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

![]()

Get the most in-demand software skills with Mapt. Mapt gives you full access to all Packt books and video courses, as well as industry-leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career.

Thanks for purchasing this Packt book. At Packt, quality is at the heart of our editorial process. To help us improve, please leave us an honest review on this book's Amazon page at https://www.amazon.com/dp/1787121704.

If you'd like to join our team of regular reviewers, you can e-mail us at customerreviews@packtpub.com. We award our regular reviewers with free eBooks and videos in exchange for their valuable feedback. Help us be relentless in improving our products!

Multithreaded applications execute multiple threads in a single processor environment, to achieve. Filled with practical examples, this book will help you become a master at writing robust concurrent and parallel applications in C++. In this book, you will delve into the fundamentals of multithreading and concurrency and find out how to implement them. While doing so, you will explore atomic operations to optimize code performance and also apply concurrency to both distributed computing and GPGPU processing.

Chapter 1, Revisiting Multithreading, summarizes multithreading in C++, revisiting all the concepts you should already be familiar with and going through a basic example of multithreading using the native threading support added in the 2011 revision of C++.

Chapter 2, Multithreading Implementation on the Processor and OS, builds upon the fundamentals provided by the hardware implementations discussed in the preceding chapter, showing how OSes have used the capabilities to their advantage and made them available to applications. It also discusses how processes and threads are allowed to use the memory and processor in order to prevent applications and threads from interfering with each other.

Chapter 3, C++ Multithreading APIs, explores the wide variety of multithreading APIs available as OS-level APIs (for example, Win32 and POSIX) or as provided by a framework (for example, Boost, Qt, and POCO). It briefly runs through each API, listing the differences compared to the others as well as the advantages and disadvantages it may have for your application.

Chapter 4, Thread Synchronization and Communication, takes the topics learned in the previous chapters and explores an advanced multithreading implementation implemented using C++ 14's native threading API, which allows multiple threads to communicate without any thread-safety issues. It also covers the differences between the many types of synchronization mechanisms, including mutexes, locks, and condition variables.

Chapter 5, Native C++ Threads and Primitives, includes threads, concurrency, local storage, as well as thread-safety supported by this API. Building upon the example in the preceding chapter, it discusses and explores extending and optimizing thread-safty using the features offered by the full feature set in C++ 11 and C++ 14.

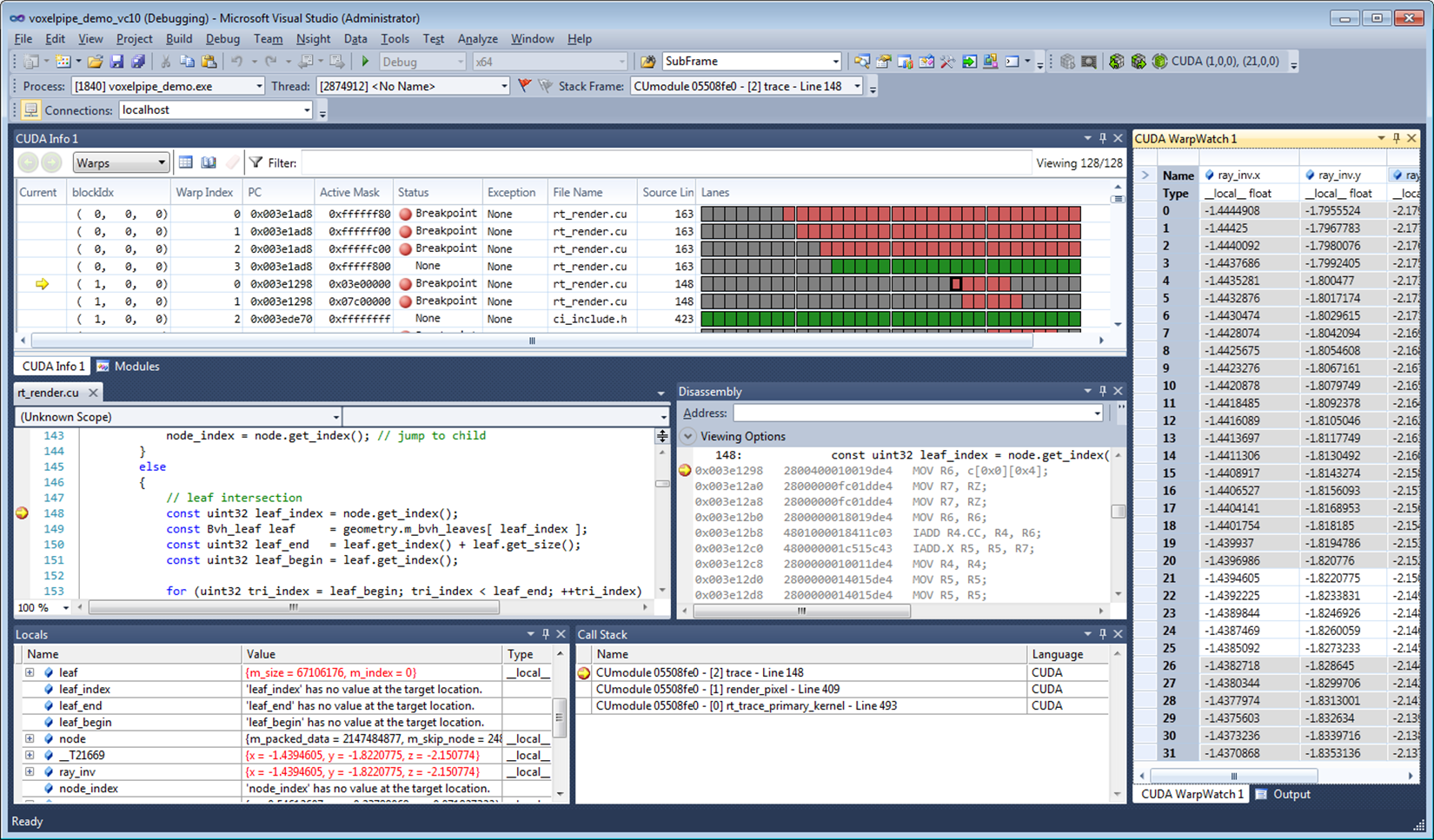

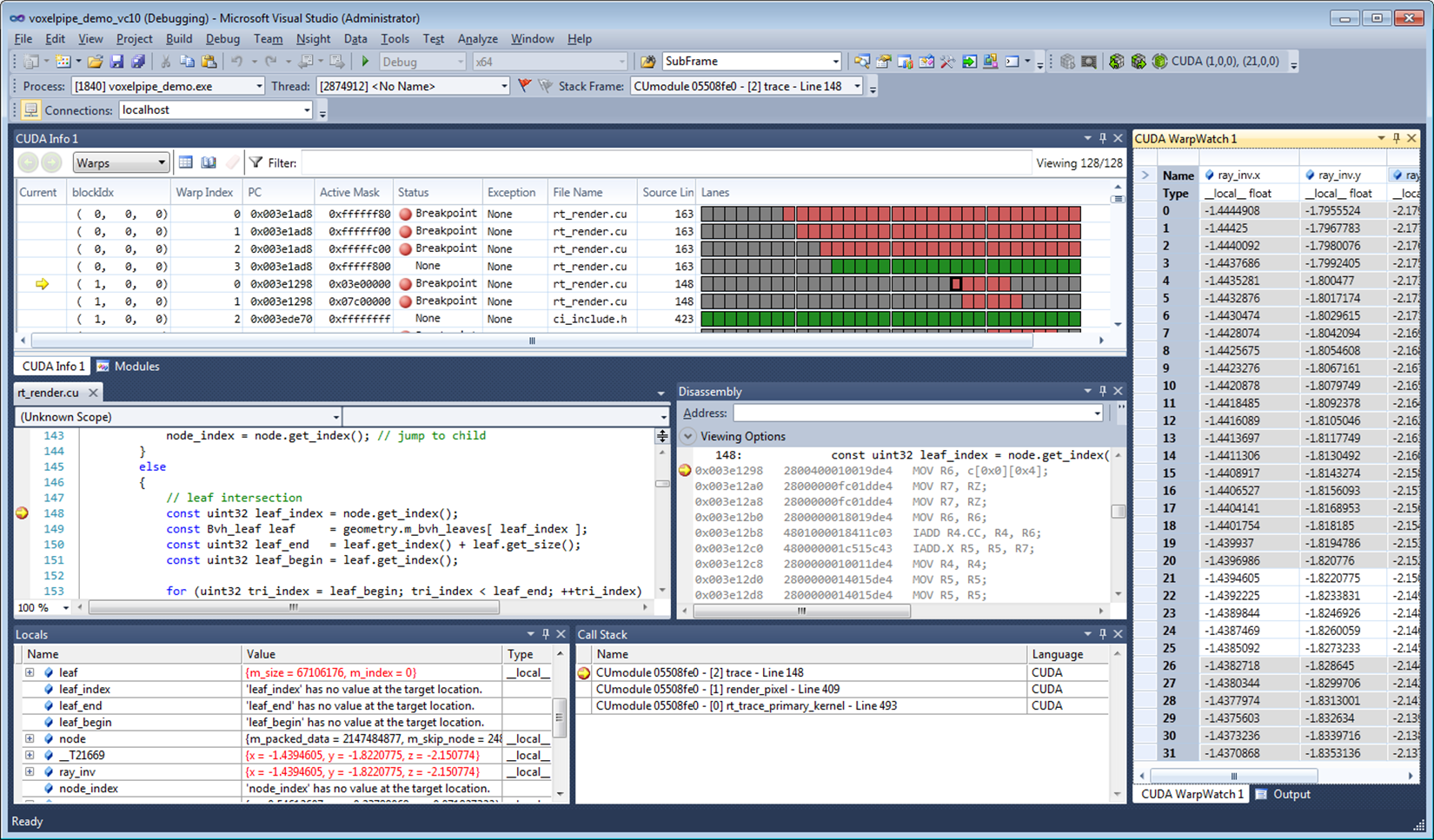

Chapter 6, Debugging Multithreaded Code, teaches you how to use tools such as Valgrind (Memcheck, DRD, Helgrind, and so on) to analyze the multithreaded performance of an application, find hotspots, and resolve or prevent issues resulting from concurrent access.

Chapter 7, Best Practices, covers common pitfalls and gotchas and how to spot them before they come back to haunt you. It also explores a number of common and less common scenarios using examples.

Chapter 8, Atomic Operations – Working with the Hardware, covers atomic operations in detail: what they are and how they are best used. Compiler support is looked at across CPU architectures and an evaluation is made of when it is worth to invest time in implementing atomic operations in your code. It also looks at how such optimizations will limit the portability of your code.

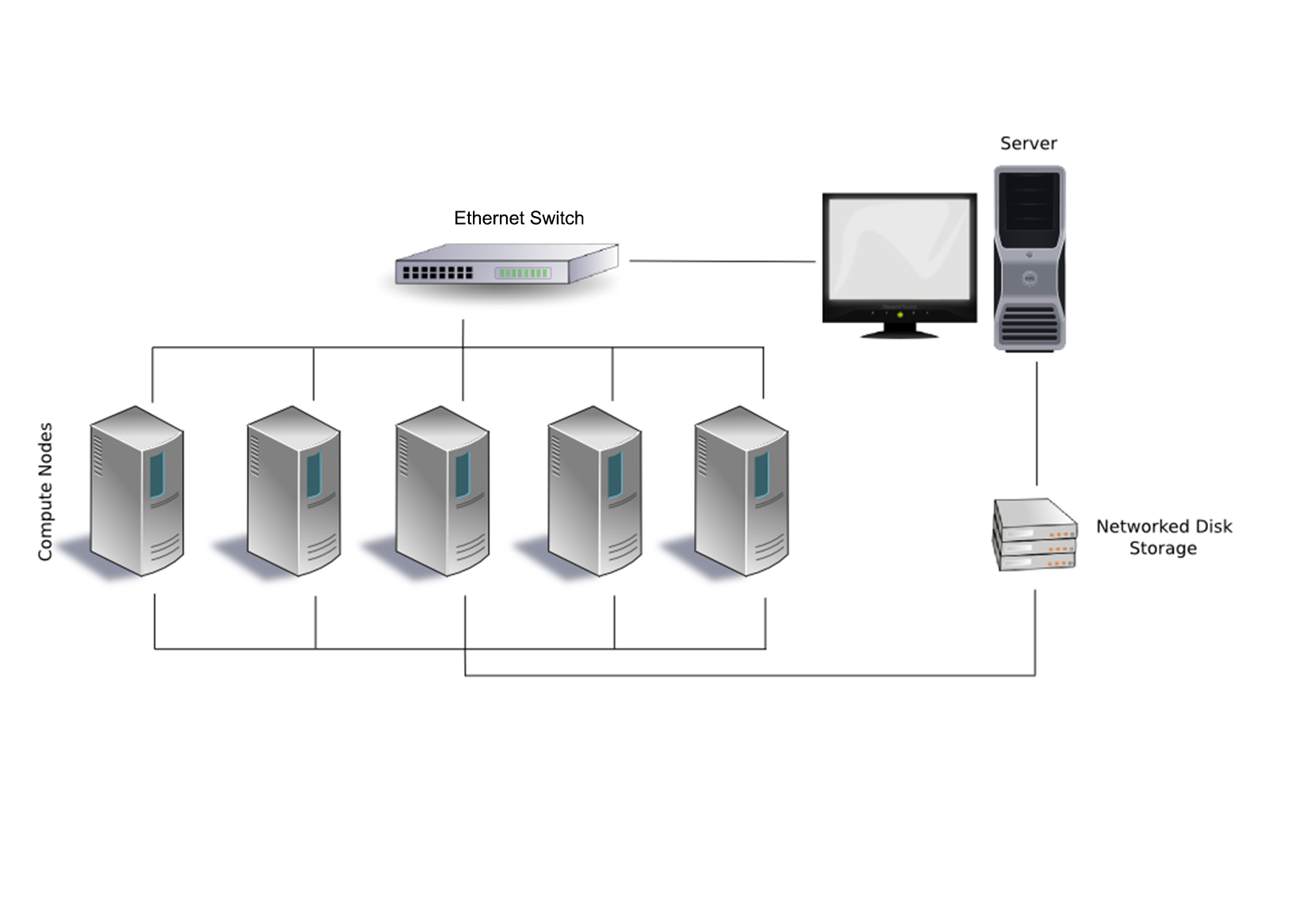

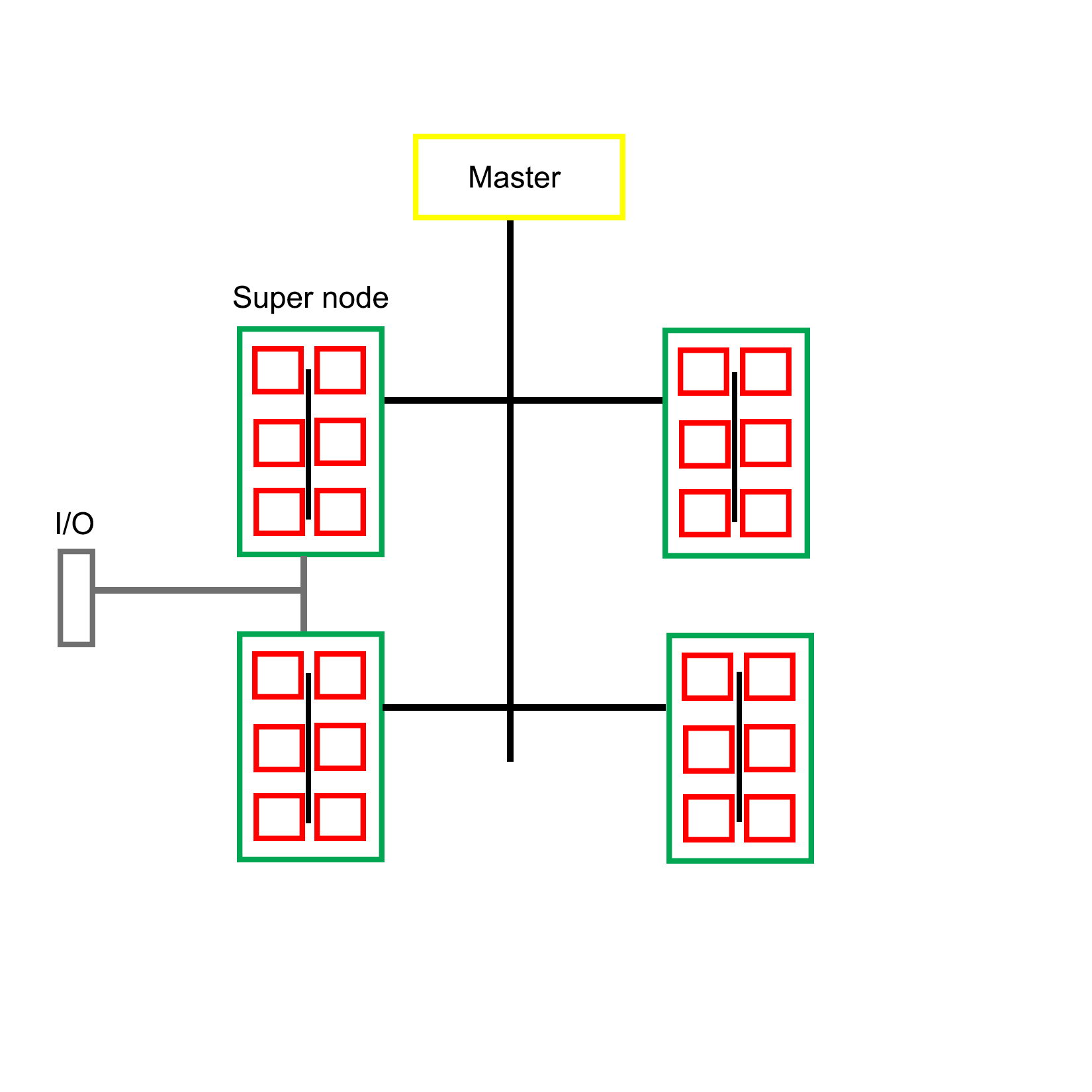

Chapter 9, Multithreading with Distributed Computing, takes many of the lessons learned in the preceding chapters and applies them on a multi-system, cluster-level scale. Using an OpenMPI-based example, it shows how multithreading can be done across multiple systems, such as the nodes in a computer cluster.

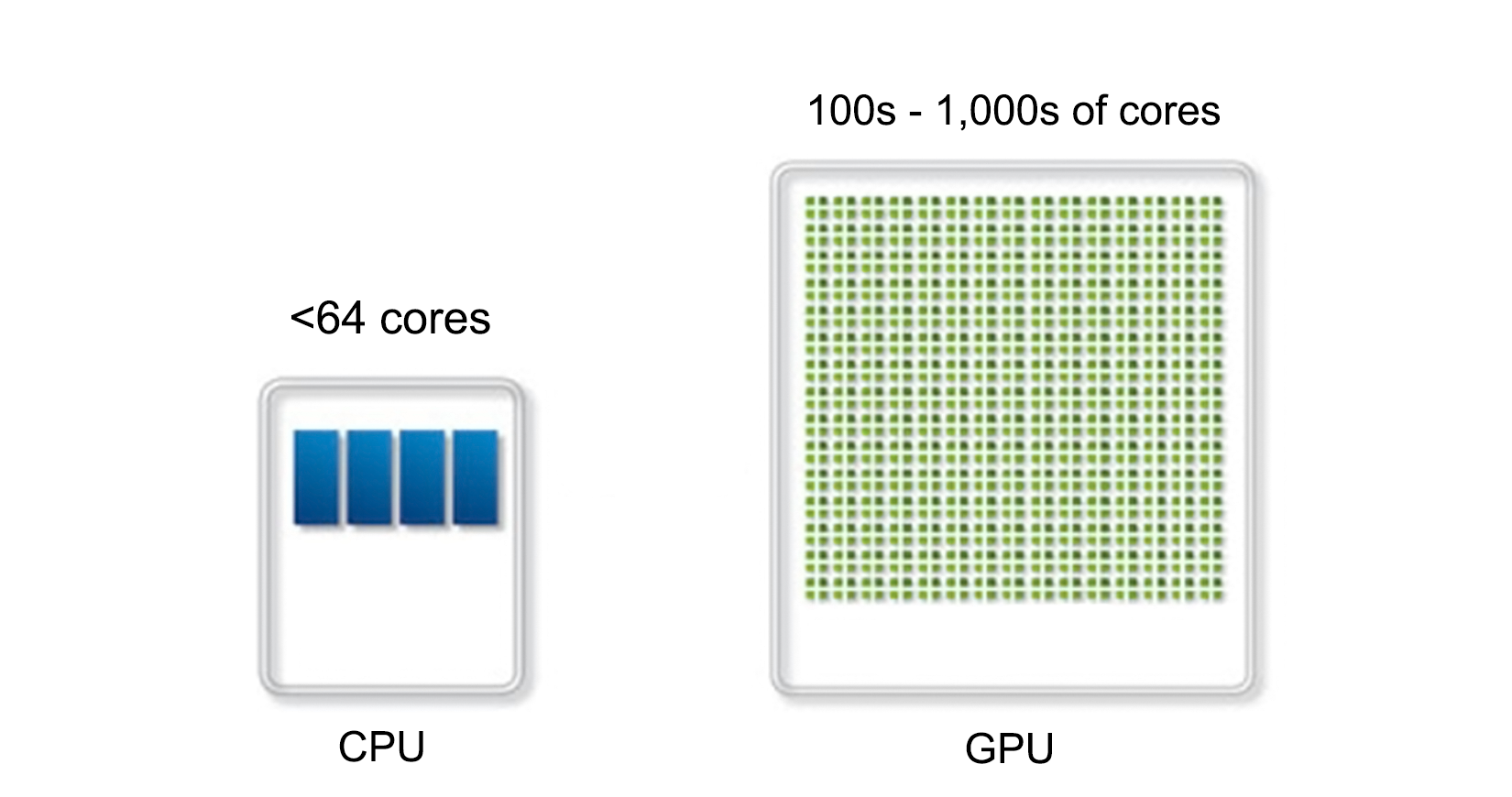

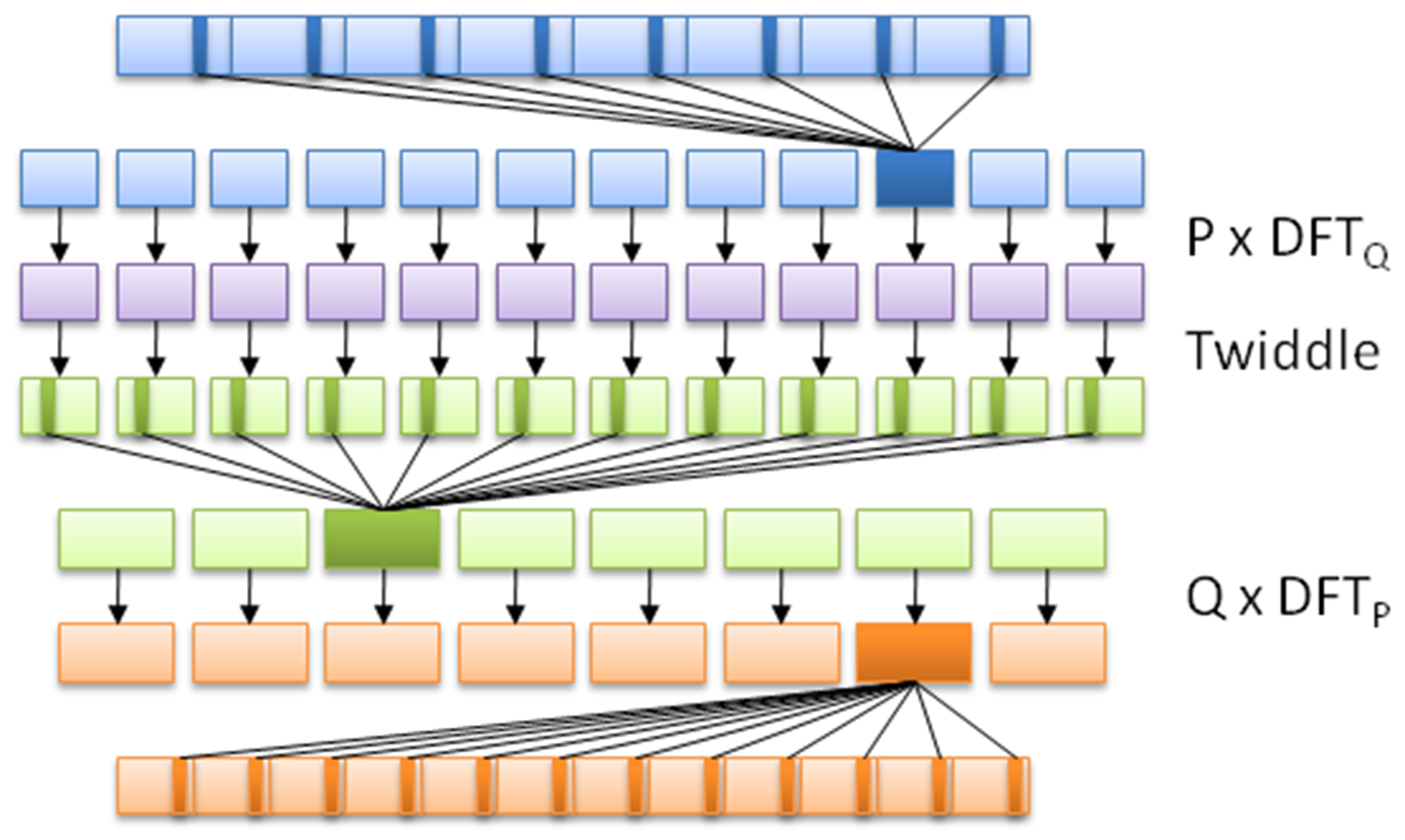

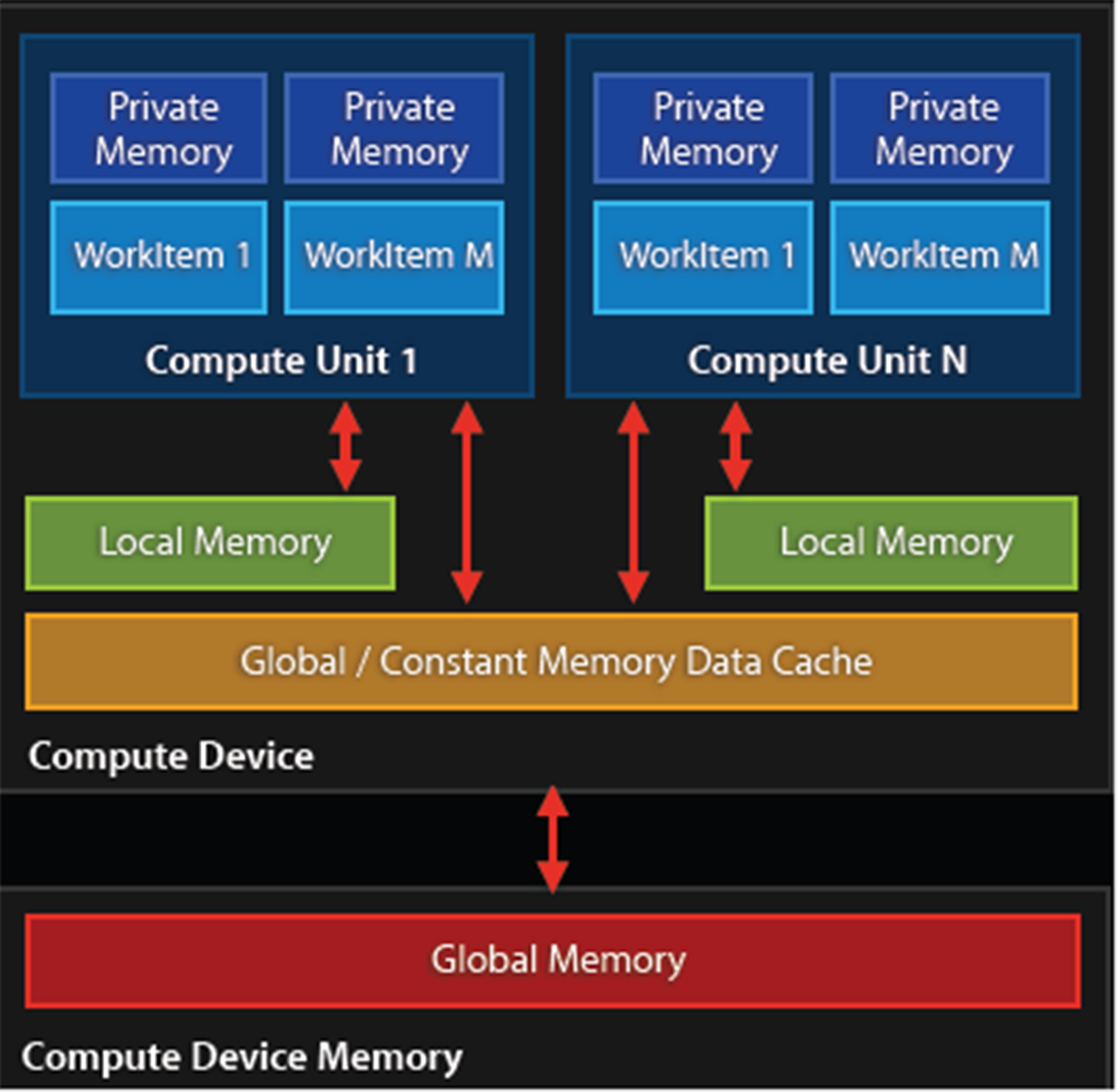

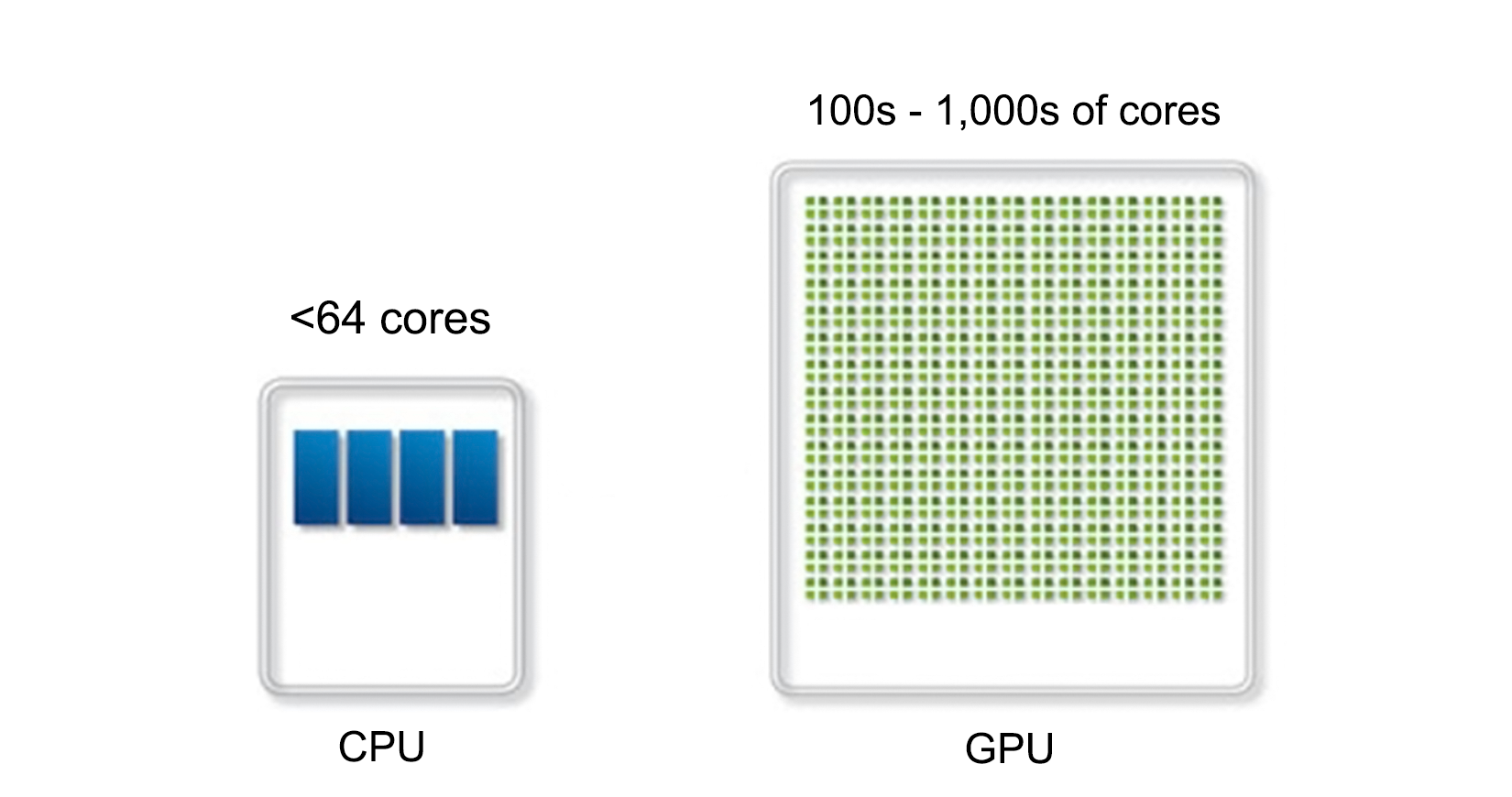

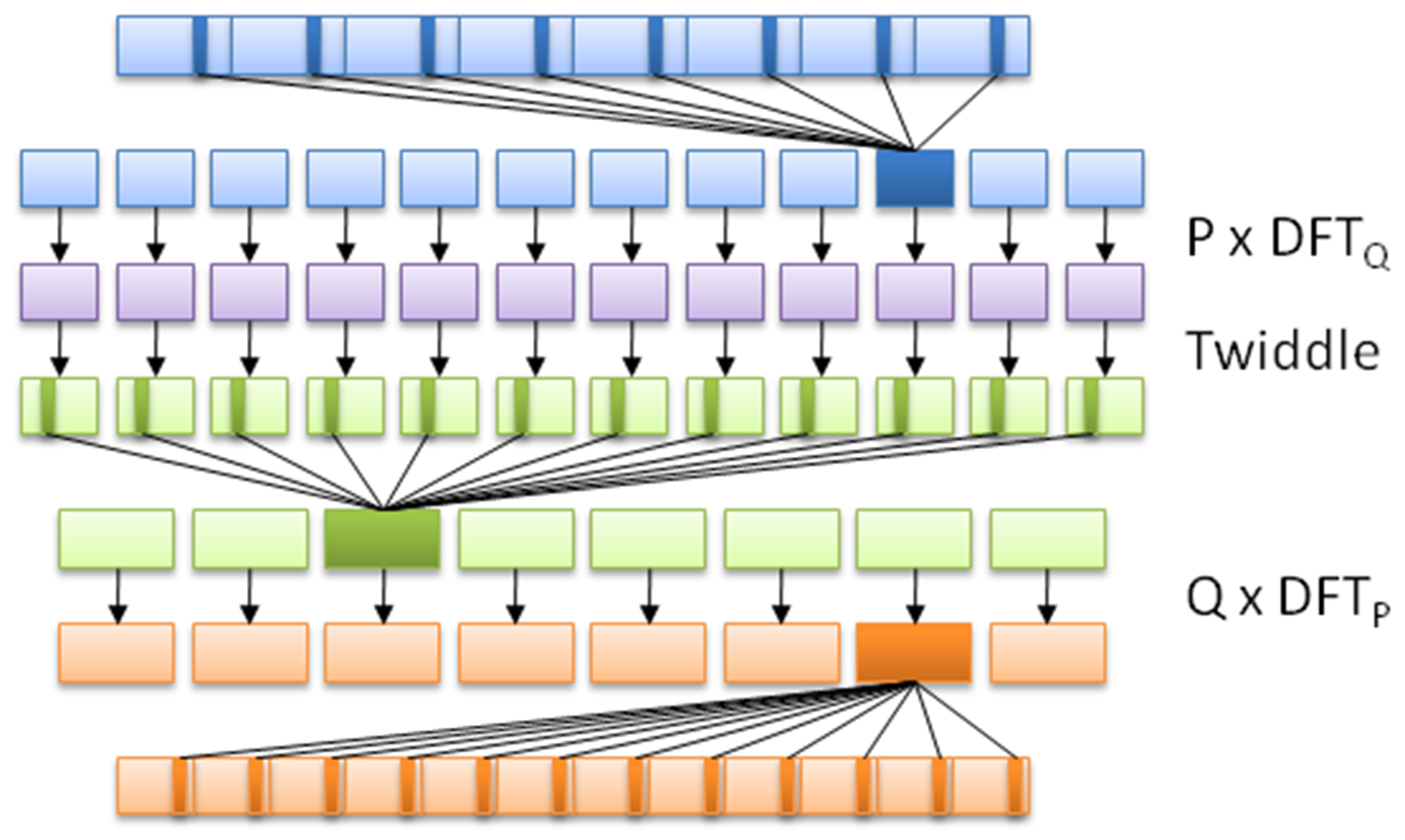

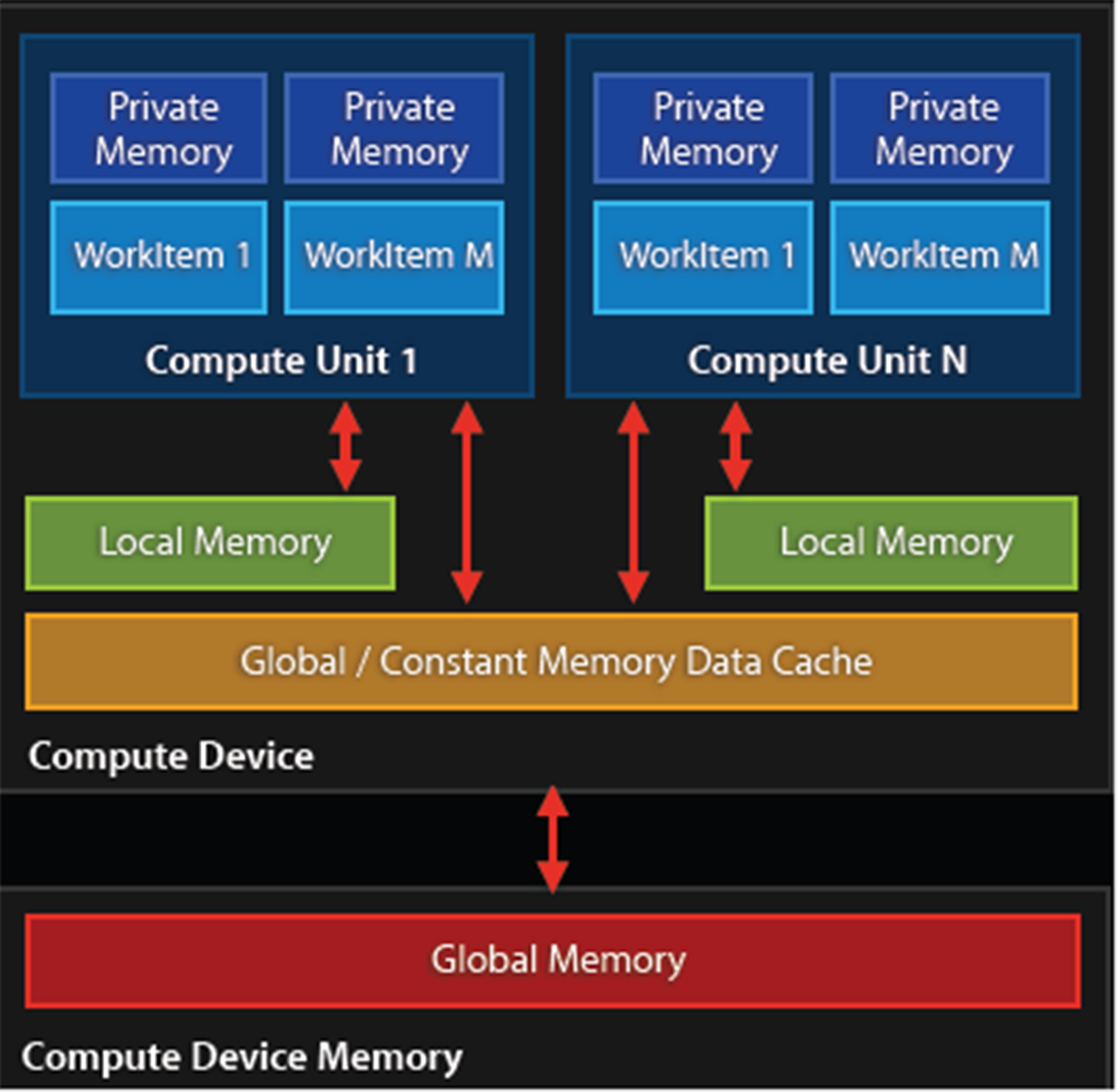

Chapter 10, Multithreading with GPGPU, shows the use of multithreading in GPGPU applications (for example, CUDA and OpenCL). Using an OpenCL-based example, a basic multithreaded application is explored that can execute tasks in parallel. This chapter takes lessons learned in the preceding chapters and applies them to processing on video cards and derived hardware (for example, rack-mounted vector processor hardware).

To follow the instructions in this book, you will need any OS (Windows, Linux, or macOS) and any C++ compiler installed on your systems.

This book is for intermediate C++ developers who wish to extend their knowledge of multithreading and concurrent processing. You should have basic experience with multithreading and be comfortable using C++ development toolchains on the command line.

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles are shown as follows: "The randGen() method takes two parameters, defining the range of the returned value:"

A block of code is set as follows:

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Thread " << tid << " adding " << rval << ". New value: " << val << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

values_mtx.lock();

values.push_back(val);

values_mtx.unlock();

}

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Thread " << tid << " adding " << rval << ". New value: " << val << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

values_mtx.lock();

values.push_back(val);

values_mtx.unlock();

}

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ make

g++ -o ch01_mt_example -std=c++11 ch01_mt_example.cpp

New terms and important words are shown in bold. Words that you see on the screen, for example, in menus or dialog boxes, appear in the text.

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book-what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of. To send us general feedback, simply e-mail feedback@packtpub.com, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message. If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you. You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Mastering-CPP-Multithreading. We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books-maybe a mistake in the text or the code-we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title. To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyrighted material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the suspected pirated material. We appreciate your help in protecting our authors and our ability to bring you valuable content.

If you have a problem with any aspect of this book, you can contact us at questions@packtpub.com, and we will do our best to address the problem.

Chances are that if you're reading this book, you have already done some multithreaded programming in C++, or, possibly, other languages. This chapter is meant to recap the topic purely from a C++ point of view, going through a basic multithreaded application, while also covering the tools we'll be using throughout the book. At the end of this chapter, you will have all the knowledge and information needed to proceed with the further chapters.

Topics covered in this chapter include the following:

During the course of this book, we'll be assuming the use of a GCC-based toolchain (GCC or MinGW on Windows). If you wish to use alternative toolchains (clang, MSVC, ICC, and so on), please consult the documentation provided with these for compatible commands.

To compile the examples provided in this book, makefiles will be used. For those unfamiliar with makefiles, they are a simple but powerful text-based format used with the make tool for automating build tasks including compiling source code and adjusting the build environment. First released in 1977, make remains among the most popular build automation tools today.

Familiarity with the command line (Bash or equivalent) is assumed, with MSYS2 (Bash on Windows) recommended for those using Windows.

In its most basic form, a multithreaded application consists of a singular process with two or more threads. These threads can be used in a variety of ways; for example, to allow the process to respond to events in an asynchronous manner by using one thread per incoming event or type of event, or to speed up the processing of data by splitting the work across multiple threads.

Examples of asynchronous responses to events include the processing of the graphical user interface (GUI) and network events on separate threads so that neither type of event has to wait on the other, or can block events from being responded to in time. Generally, a single thread performs a single task, such as the processing of GUI or network events, or the processing of data.

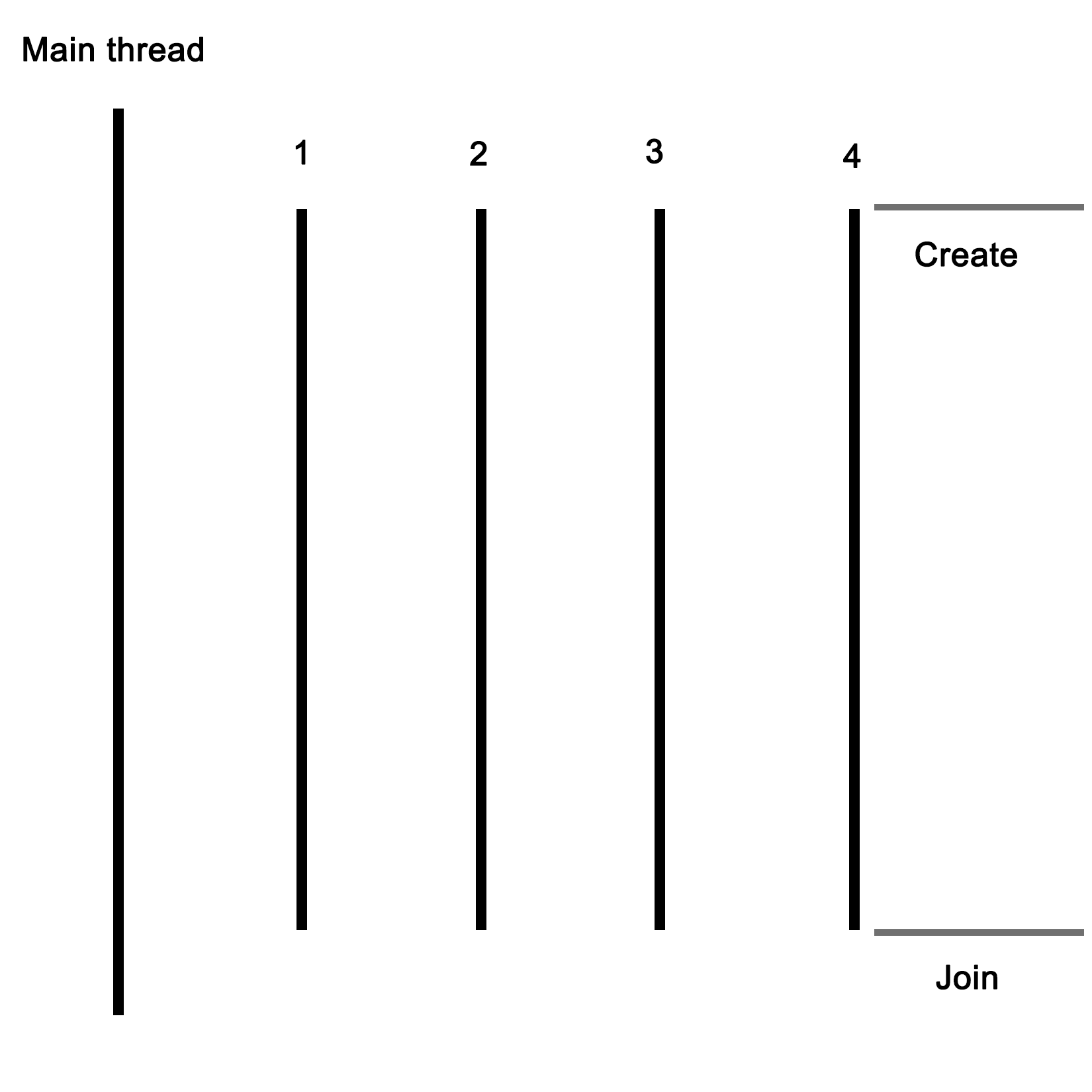

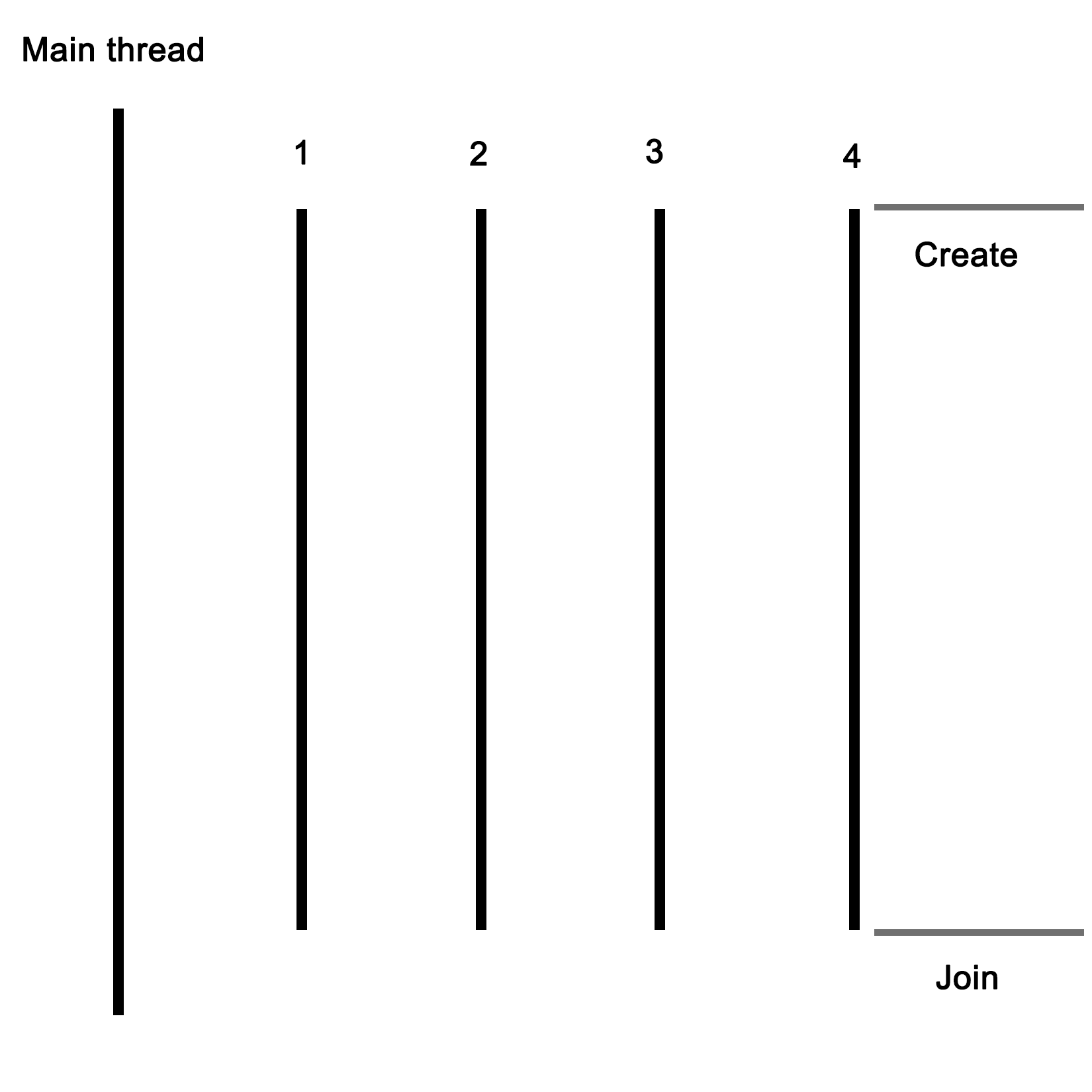

For this basic example, the application will start with a singular thread, which will then launch a number of threads, and wait for them to finish. Each of these new threads will perform its own task before finishing.

Let's start with the includes and global variables for our application:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

using namespace std;

// --- Globals

mutex values_mtx;

mutex cout_mtx;

vector<int> values;

Both the I/O stream and vector headers should be familiar to anyone who has ever used C++: the former is here used for the standard output (cout), and the vector for storing a sequence of values.

The random header is new in c++11, and as the name suggests, it offers classes and methods for generating random sequences. We use it here to make our threads do something interesting.

Finally, the thread and mutex includes are the core of our multithreaded application; they provide the basic means for creating threads, and allow for thread-safe interactions between them.

Moving on, we create two mutexes: one for the global vector and one for cout, since the latter is not thread-safe.

Next we create the main function as follows:

int main() {

values.push_back(42);

We push a fixed value onto the vector instance; this one will be used by the threads we create in a moment:

thread tr1(threadFnc, 1);

thread tr2(threadFnc, 2);

thread tr3(threadFnc, 3);

thread tr4(threadFnc, 4);

We create new threads, and provide them with the name of the method to use, passing along any parameters--in this case, just a single integer:

tr1.join();

tr2.join();

tr3.join();

tr4.join();

Next, we wait for each thread to finish before we continue by calling join() on each thread instance:

cout << "Input: " << values[0] << ", Result 1: " << values[1] << ", Result 2: " << values[2] << ", Result 3: " << values[3] << ", Result 4: " << values[4] << "\n";

return 1;

}

At this point, we expect that each thread has done whatever it's supposed to do, and added the result to the vector, which we then read out and show the user.

Of course, this shows almost nothing of what really happens in the application, mostly just the essential simplicity of using threads. Next, let's see what happens inside this method that we pass to each thread instance:

void threadFnc(int tid) {

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Starting thread " << tid << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

In the preceding code, we can see that the integer parameter being passed to the thread method is a thread identifier. To indicate that the thread is starting, a message containing the thread identifier is output. Since we're using a non-thread-safe method for this, we use the cout_mtx mutex instance to do this safely, ensuring that just one thread can write to cout at any time:

values_mtx.lock();

int val = values[0];

values_mtx.unlock();

When we obtain the initial value set in the vector, we copy it to a local variable so that we can immediately release the mutex for the vector to enable other threads to use the vector:

int rval = randGen(0, 10);

val += rval;

These last two lines contain the essence of what the threads created do: they take the initial value, and add a randomly generated value to it. The randGen() method takes two parameters, defining the range of the returned value:

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Thread " << tid << " adding " << rval << ". New value: " << val << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

values_mtx.lock();

values.push_back(val);

values_mtx.unlock();

}

Finally, we (safely) log a message informing the user of the result of this action before adding the new value to the vector. In both cases, we use the respective mutex to ensure that there can be no overlap when accessing the resource with any of the other threads.

Once the method reaches this point, the thread containing it will terminate, and the main thread will have one less thread to wait for to rejoin. The joining of a thread basically means that it stops existing, usually with a return value passed to the thread which created the thread. This can happen explicitly, with the main thread waiting for the child thread to finish, or in the background.

Lastly, we'll take a look at the randGen() method. Here we can see some multithreaded specific additions as well:

int randGen(const int& min, const int& max) {

static thread_local mt19937 generator(hash<thread::id>()(this_thread::get_id()));

uniform_int_distribution<int> distribution(min, max);

return distribution(generator)

}

This preceding method takes a minimum and maximum value as explained earlier, which limits the range of the random numbers this method can return. At its core, it uses a mt19937-based generator, which employs a 32-bit Mersenne Twister algorithm with a state size of 19937 bits. This is a common and appropriate choice for most applications.

Of note here is the use of the thread_local keyword. What this means is that even though it is defined as a static variable, its scope will be limited to the thread using it. Every thread will thus create its own generator instance, which is important when using the random number API in the STL.

A hash of the internal thread identifier is used as a seed for the generator. This ensures that each thread gets a fairly unique seed for its generator instance, allowing for better random number sequences.

Finally, we create a new uniform_int_distribution instance using the provided minimum and maximum limits, and use it together with the generator instance to generate the random number which we return.

In order to compile the code described earlier, one could use an IDE, or type the command on the command line. As mentioned in the beginning of this chapter, we'll be using makefiles for the examples in this book. The big advantages of this are that one does not have to repeatedly type in the same extensive command, and it is portable to any system which supports make.

Further advantages include being able to have previous generated artifacts removed automatically and to only compile those source files which have changed, along with a detailed control over build steps.

The makefile for this example is rather basic:

GCC := g++

OUTPUT := ch01_mt_example

SOURCES := $(wildcard *.cpp)

CCFLAGS := -std=c++11 -pthread

all: $(OUTPUT)

$(OUTPUT):

$(GCC) -o $(OUTPUT) $(CCFLAGS) $(SOURCES)

clean:

rm $(OUTPUT)

.PHONY: all

From the top down, we first define the compiler that we'll use (g++), set the name of the output binary (the .exe extension on Windows will be post-fixed automatically), followed by the gathering of the sources and any important compiler flags.

The wildcard feature allows one to collect the names of all files matching the string following it in one go without having to define the name of each source file in the folder individually.

For the compiler flags, we're only really interested in enabling the c++11 features, for which GCC still requires one to supply this compiler flag.

For the all method, we just tell make to run g++ with the supplied information. Next we define a simple clean method which just removes the produced binary, and finally, we tell make to not interpret any folder or file named all in the folder, but to use the internal method with the .PHONY section.

When we run this makefile, we see the following command-line output:

$ make

g++ -o ch01_mt_example -std=c++11 ch01_mt_example.cpp

Afterwards, we find an executable file called ch01_mt_example (with the .exe extension attached on Windows) in the same folder. Executing this binary will result in a command-line output akin to the following:

$ ./ch01_mt_example.exe

Starting thread 1.

Thread 1 adding 8. New value: 50.

Starting thread 2.

Thread 2 adding 2. New value: 44.

Starting thread 3.

Starting thread 4.

Thread 3 adding 0. New value: 42.

Thread 4 adding 8. New value: 50.

Input: 42, Result 1: 50, Result 2: 44, Result 3: 42, Result 4: 50

What one can see here already is the somewhat asynchronous nature of threads and their output. While threads 1 and 2 appear to run synchronously, starting and quitting seemingly in order, threads 3 and 4 clearly run asynchronously as both start simultaneously before logging their action. For this reason, and especially in longer-running threads, it's virtually impossible to say in which order the log output and results will be returned.

While we use a simple vector to collect the results of the threads, there is no saying whether Result 1 truly originates from the thread which we assigned ID 1 in the beginning. If we need this information, we need to extend the data we return by using an information structure with details on the processing thread or similar.

One could, for example, use struct like this:

struct result {

int tid;

int result;

};

The vector would then be changed to contain result instances rather than integer instances. One could pass the initial integer value directly to the thread as part of its parameters, or pass it via some other way.

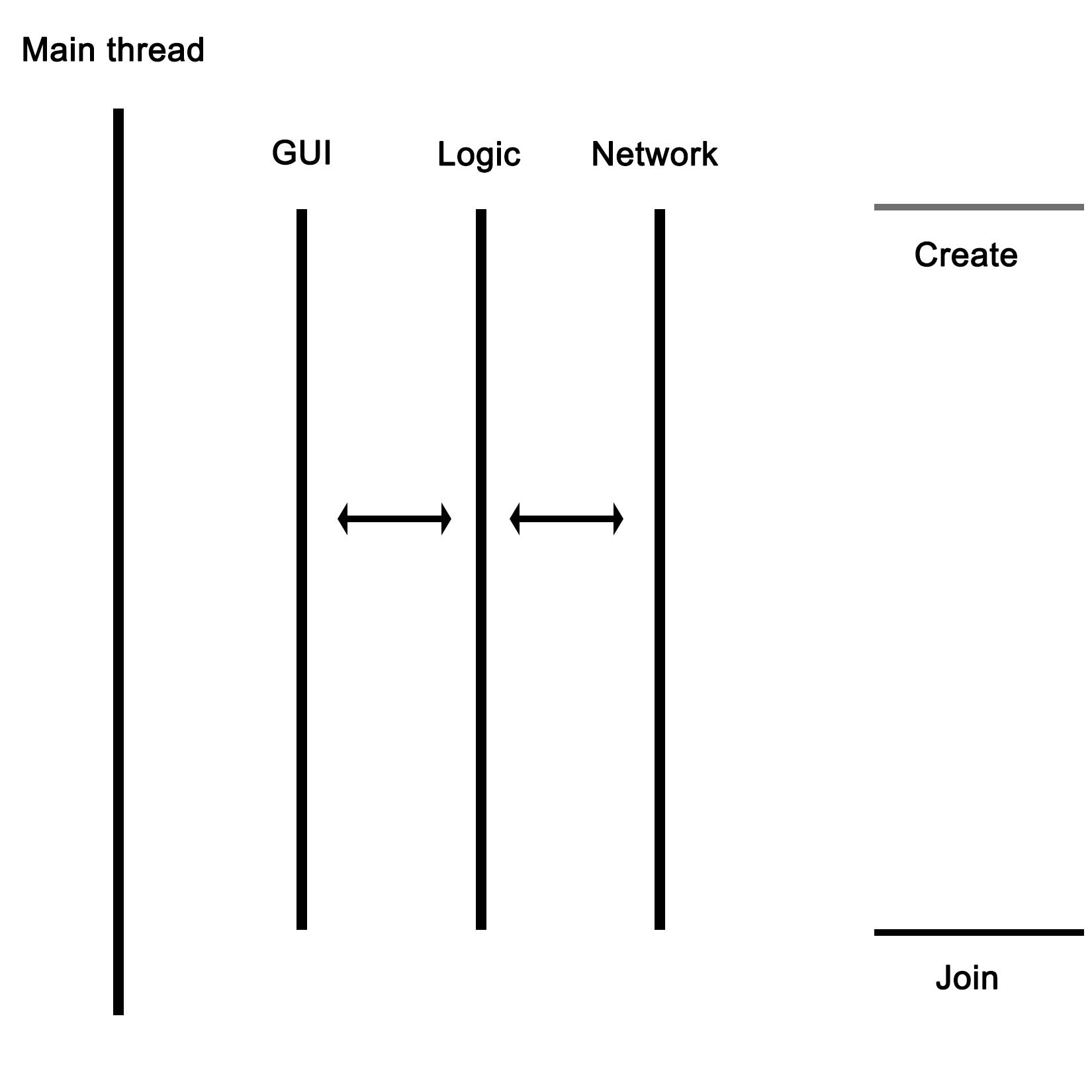

The example in this chapter is primarily useful for applications where data or tasks have to be handled in parallel. For the earlier mentioned use case of a GUI-based application with business logic and network-related features, the basic setup of a main application, which launches the required threads, would remain the same. However, instead of having each thread to be the same, each would be a completely different method.

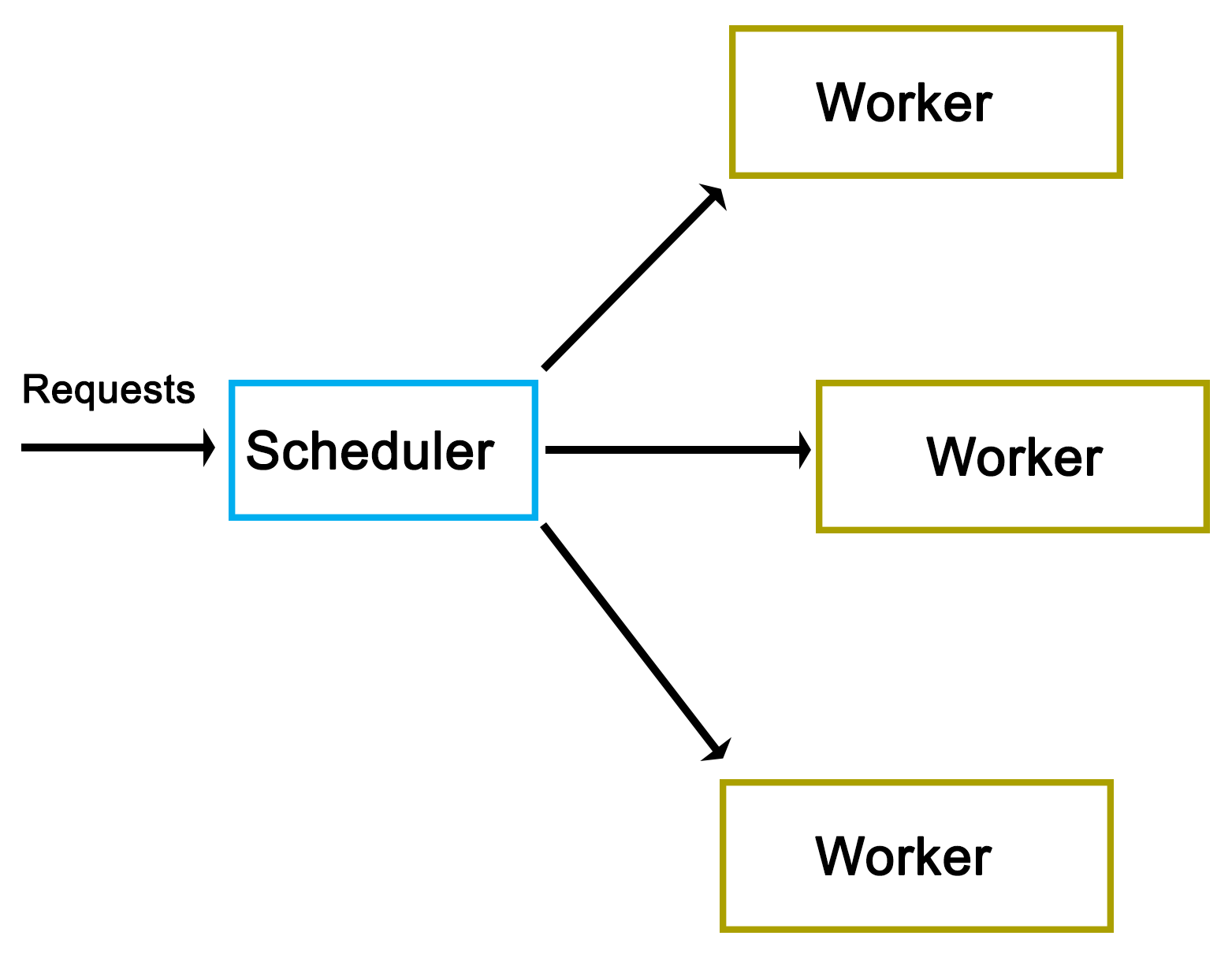

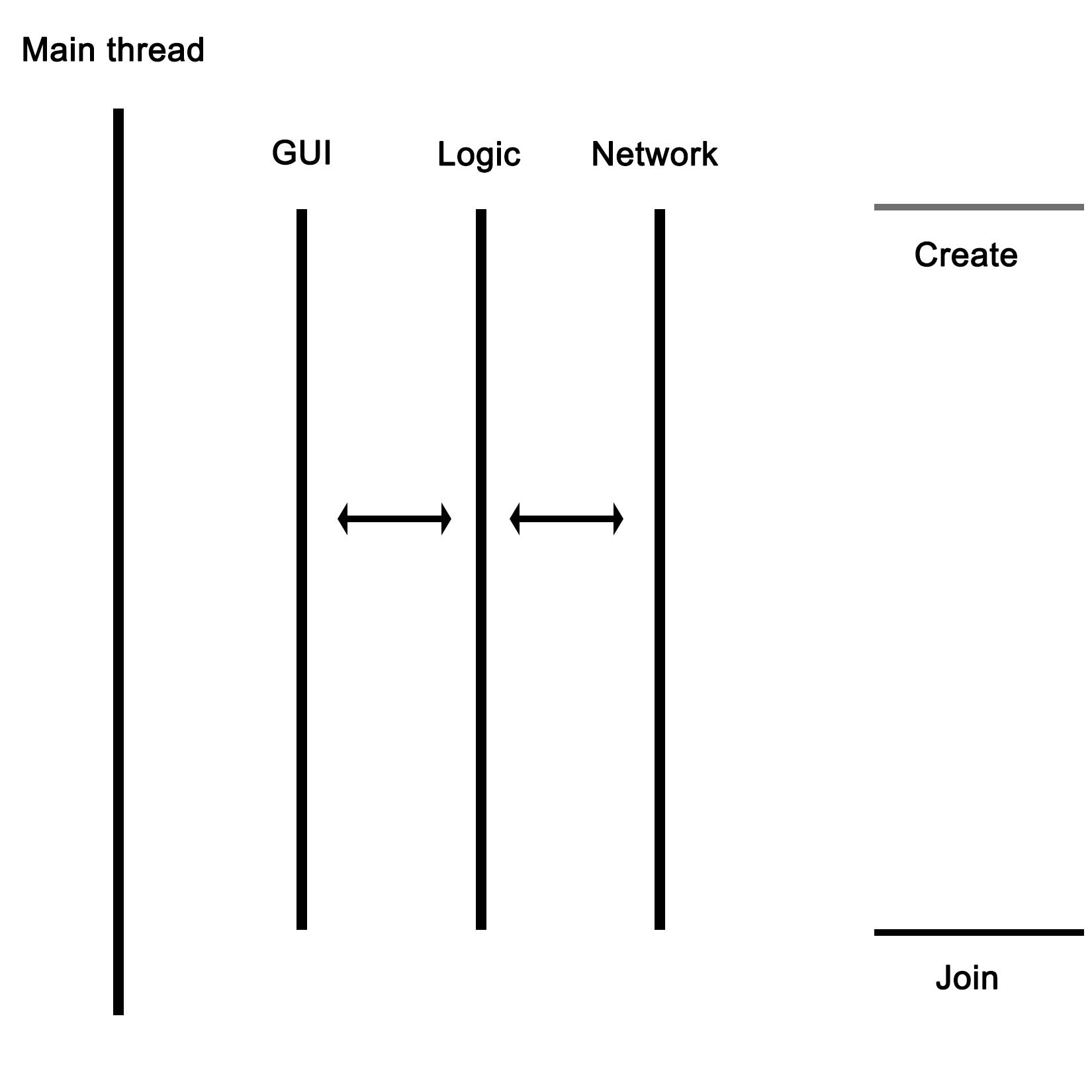

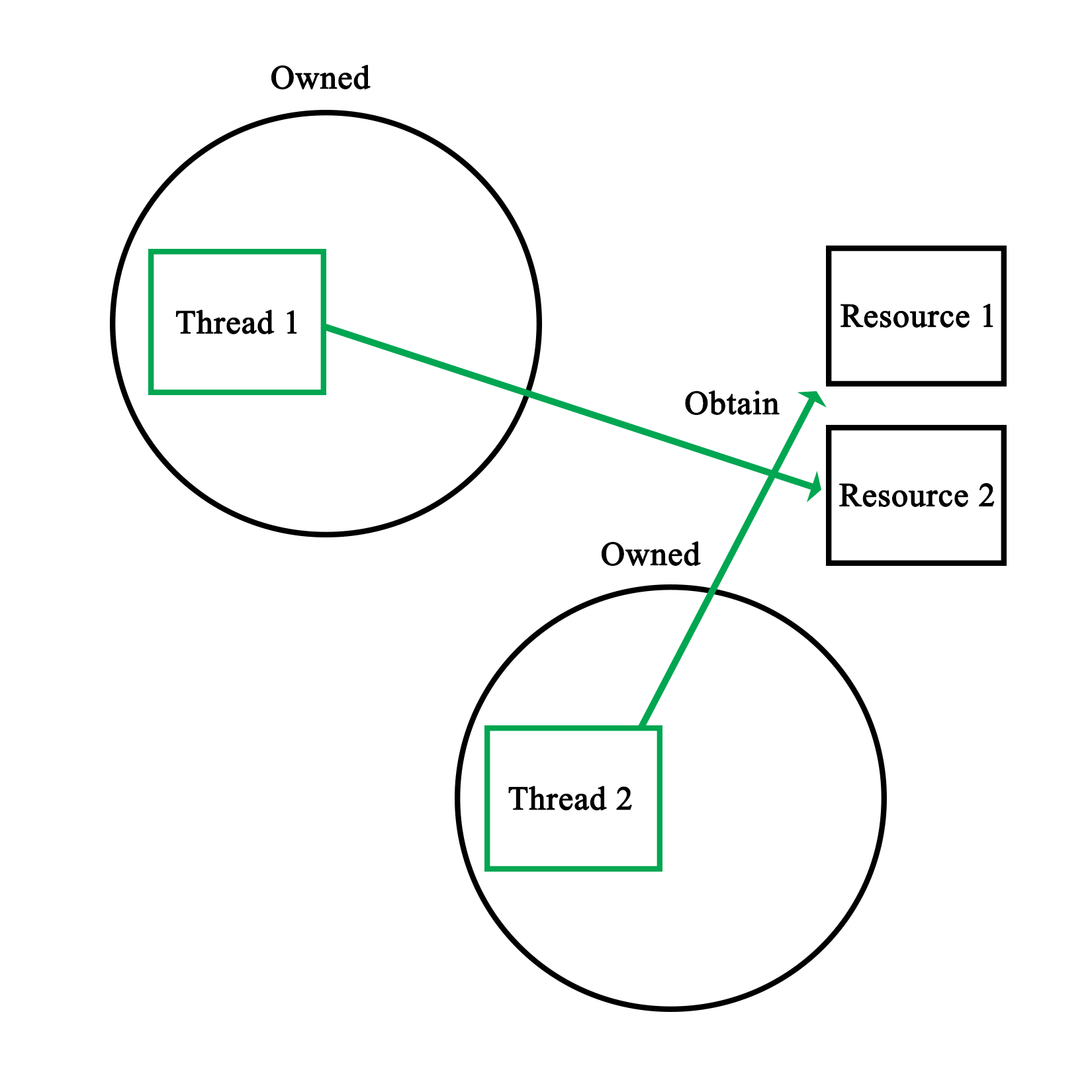

For this type of application, the thread layout would look like this:

As the graphic shows, the main thread would launch the GUI, network, and business logic thread, with the latter communicating with the network thread to send and receive data. The business logic thread would also receive user input from the GUI thread, and send updates back to be displayed on the GUI.

In this chapter, we went over the basics of a multithreaded application in C++ using the native threading API. We looked at how to have multiple threads perform a task in parallel, and also explored how to properly use the random number API in the STL within a multithreaded application.

In the next chapter, we'll discuss how multithreading is implemented both in hardware and in operating systems. We'll see how this implementation differs per processor architecture and operating system, and how this affects our multithreaded application.

The foundation of any multithreaded application is formed by the implementation of the required features by the hardware of the processor, as well as by the way these features are translated into an API for use by applications by the operating system. An understanding of this foundation is crucial for developing an intuitive understanding of how to best implement a multithreaded application.

This chapter looks at how hardware and operating systems have evolved over the years to arrive at the current implementations and APIs as they are in use today. It shows how the example code of the previous chapter ultimately translates into commands to the processor and related hardware.

Topics covered in this chapter include the following:

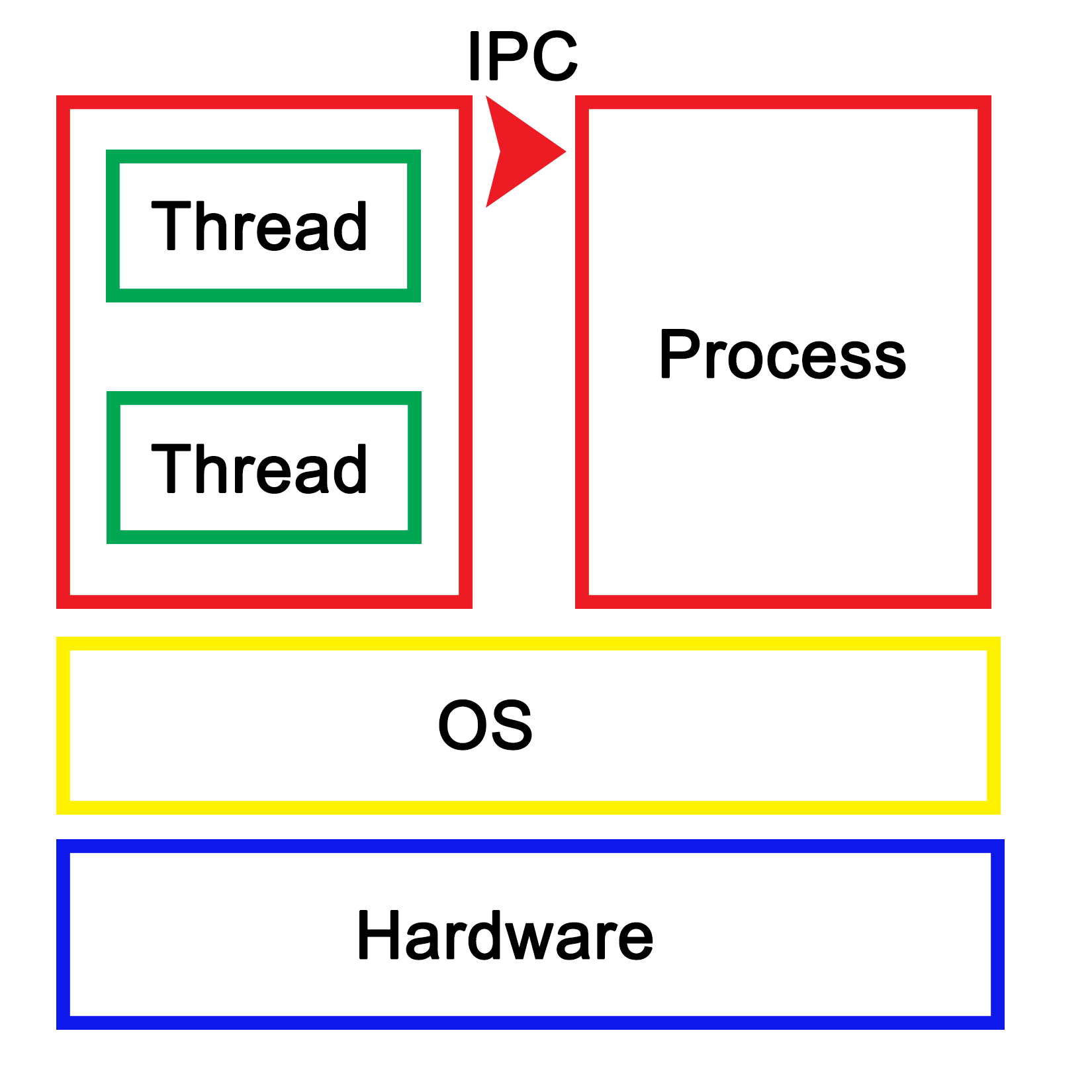

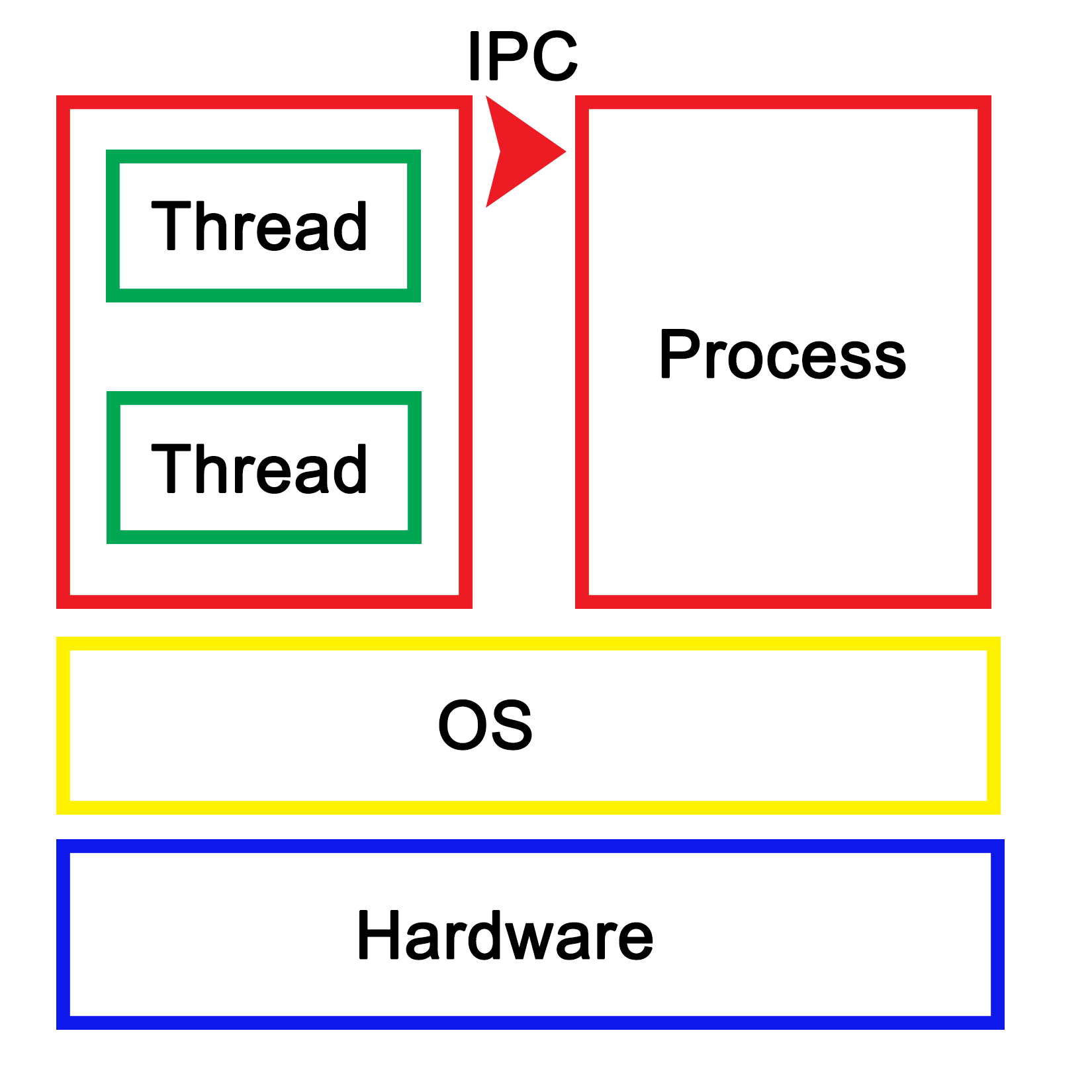

Essentially, to the operating system (OS), a process consists of one or more threads, each thread processing its own state and variables. One would regard this as a hierarchical configuration, with the OS as the foundation, providing support for the running of (user) processes. Each of these processes then consists of one or more threads. Communication between processes is handled by inter-process communication (IPC), which is provided by the operating system.

In a graphical view, this looks like the following:

Each process within the OS has its own state, with each thread in a process having its own state as well as the relative to the other threads within that same process. While IPC allows processes to communicate with each other, threads can communicate with other threads within the process in a variety of ways, which we'll explore in more depth in upcoming chapters. This generally involves some kind of shared memory between threads.

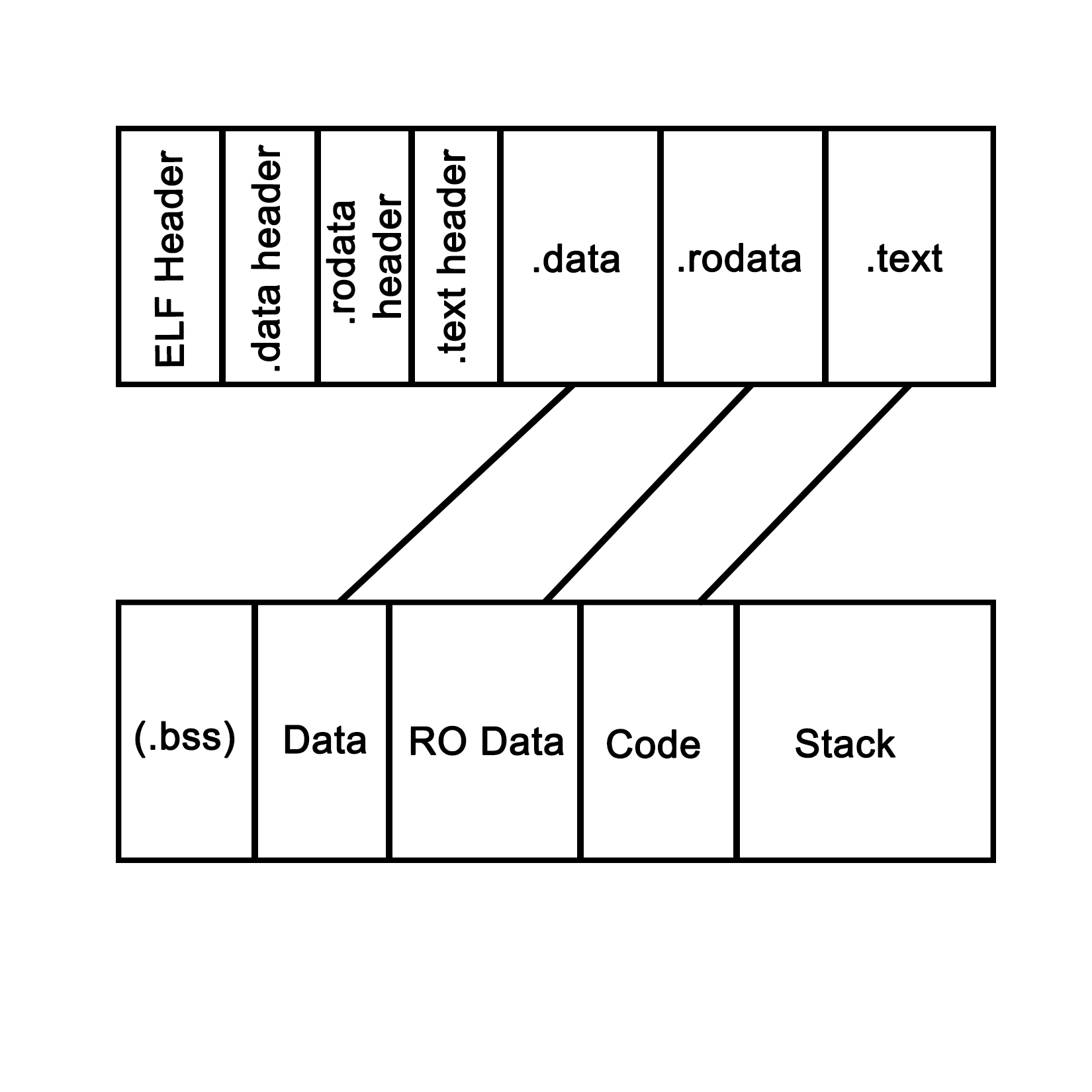

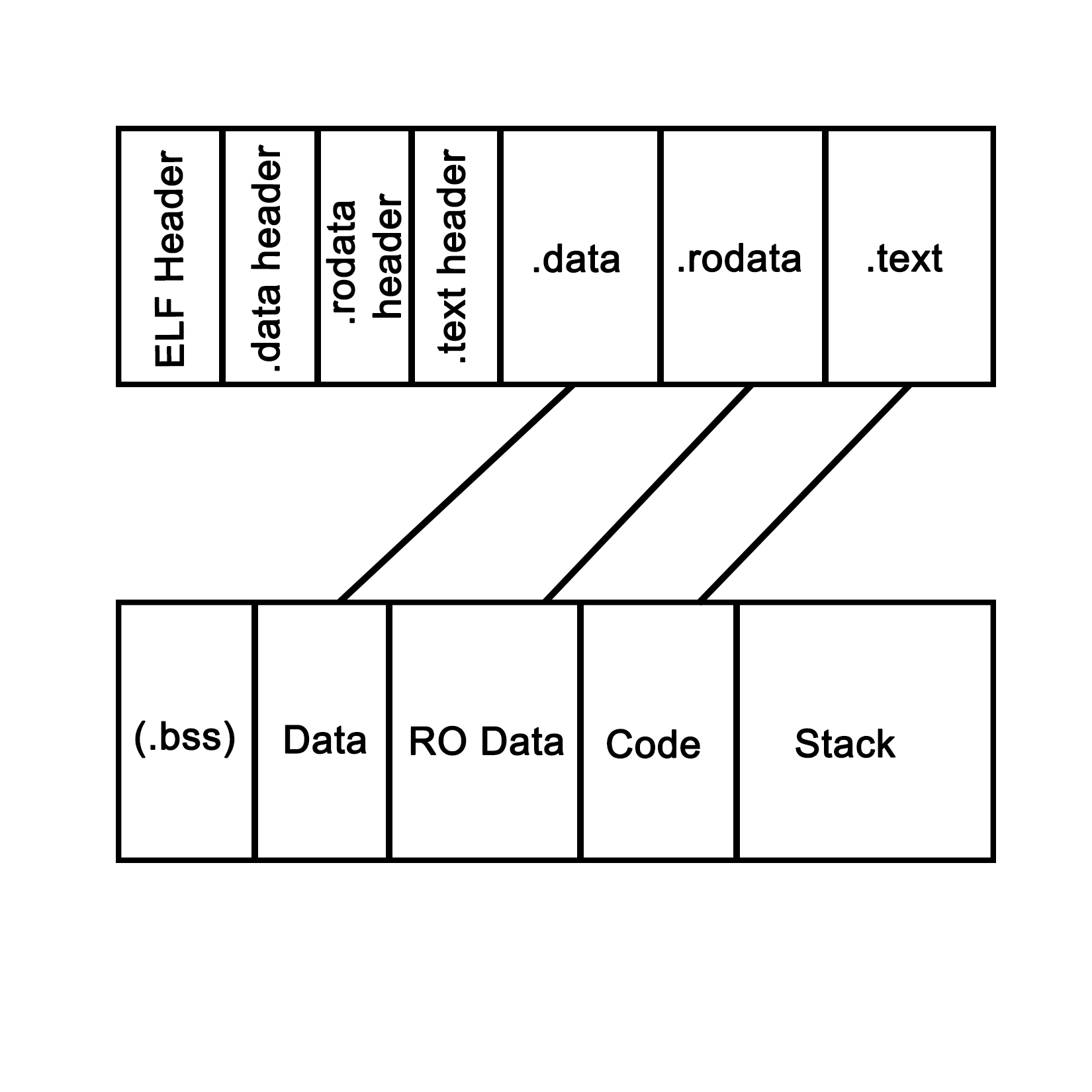

An application is loaded from binary data in a specific executable format such as, for example, Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) which is generally used on Linux and many other operating systems. With ELF binaries, the following number of sections should always be present:

The .bss section is, essentially, allocated with uninitialized memory including empty arrays which thus do not take up any space in the binary, as it makes no sense to store rows of pure zeroes in the executable. Similarly, there is the .data section with initialized data. This contains global tables, variables, and the like. Finally, the .rodata section is like .data, but it is, as the name suggests, read-only. It contains things such as hardcoded strings.

In the .text section, we find the actual application instructions (code) which will be executed by the processor. The whole of this will get loaded by the operating system, thus creating a process. The layout of such a process looks like the following diagram:

This is what a process looks like when launched from an ELF-format binary, though the final format in memory is roughly the same in basically any OS, including for a Windows process launched from a PE-format binary. Each of the sections in the binary are loaded into their respective sections, with the BSS section allocated to the specified size. The .text section is loaded along with the other sections, and its initial instruction is executed once this is done, which starts the process.

In system languages such as C++, one can see how variables and other program state information within such a process are stored both on the stack (variables exist within the scope) and heap (using the new operator). The stack is a section of memory (one allocated per thread), the size of which depends on the operating system and its configuration. One can generally also set the stack size programmatically when creating a new thread.

In an operating system, a process consists of a block of memory addresses, the size of which is constant and limited by the size of its memory pointers. For a 32-bit OS, this would limit this block to 4 GB. Within this virtual memory space, the OS allocates a basic stack and heap, both of which can grow until all memory addresses have been exhausted, and further attempts by the process to allocate more memory will be denied.

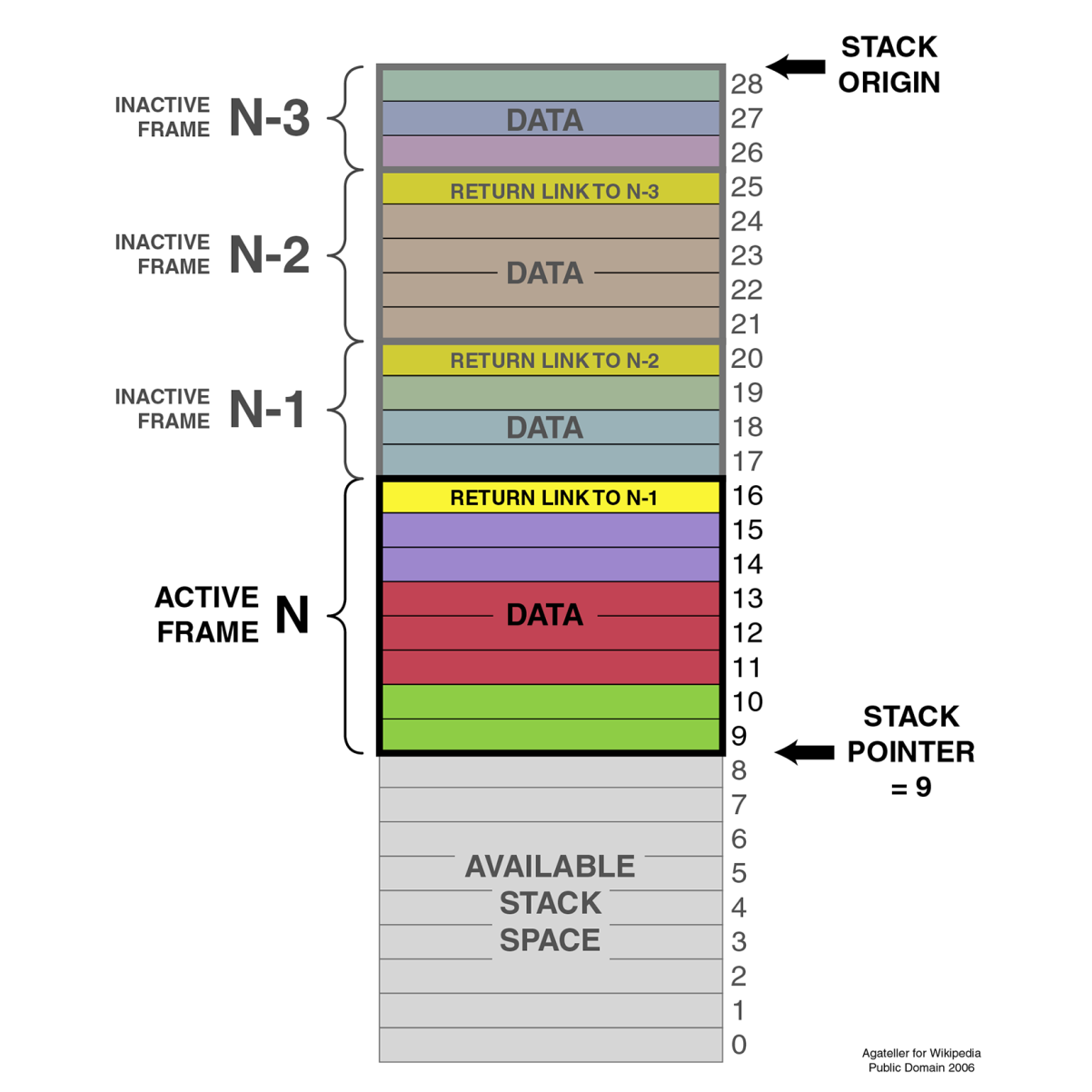

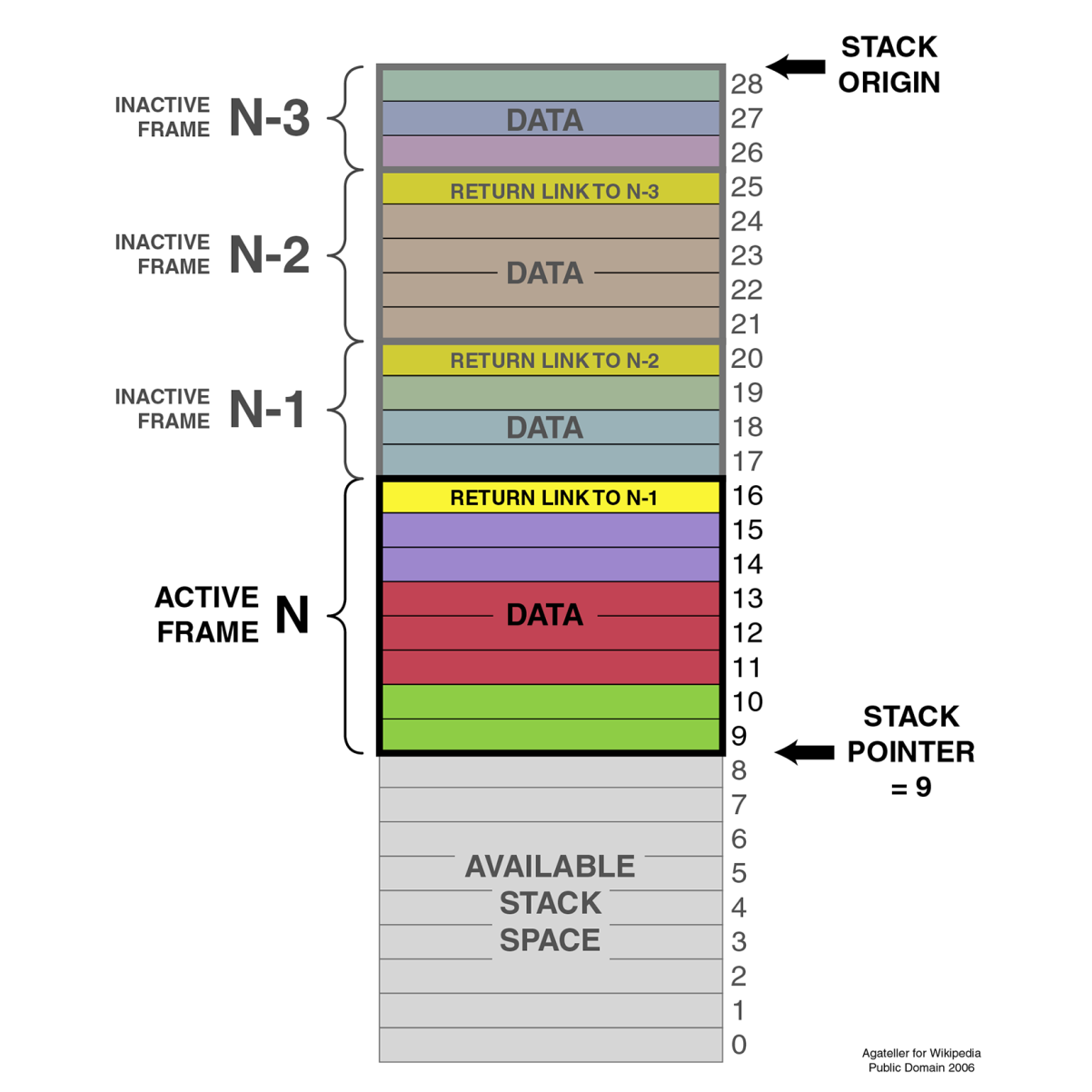

The stack is a concept both for the operating system and for the hardware. In essence, it's a collection (stack) of so-called stack frames, each of which is composed of variables, instructions, and other data relevant to the execution frame of a task.

In hardware terms, the stack is part of the task (x86) or process state (ARM), which is how the processor defines an execution instance (program or thread). This hardware-defined entity contains the entire state of a singular thread of execution. See the following sections for further details on this.

A task is defined as follows in the Intel IA-32 System Programming guide, Volume 3A:

"A task is a unit of work that a processor can dispatch, execute, and suspend. It can be used to execute a program, a task or process, an operating-system service utility, an interrupt or exception handler, or a kernel or executive utility."

"The IA-32 architecture provides a mechanism for saving the state of a task, for dispatching tasks for execution, and for switching from one task to another. When operating in protected mode, all processor execution takes place from within a task. Even simple systems must define at least one task. More complex systems can use the processor's task management facilities to support multitasking applications."

This excerpt from the IA-32 (Intel x86) manual summarizes how the hardware supports and implements support for operating systems, processes, and the switching between these processes.

It's important to realize here that, to the processor, there's no such thing as a process or thread. All it knows of are threads of execution, defined as a series of instructions. These instructions are loaded into memory somewhere, and the current position in these instructions is kept track of along with the variable data (variables) being created, as the application is executed within the data section of the process.

Each task also runs within a hardware-defined protection ring, with the OS's tasks generally running on ring 0, and user tasks on ring 3. Rings 1 and 2 are rarely used except for specific use cases with modern OSes on the x86 architecture. These rings are privilege-levels enforced by the hardware and allow for example for the strict separation of kernel and user-level tasks.

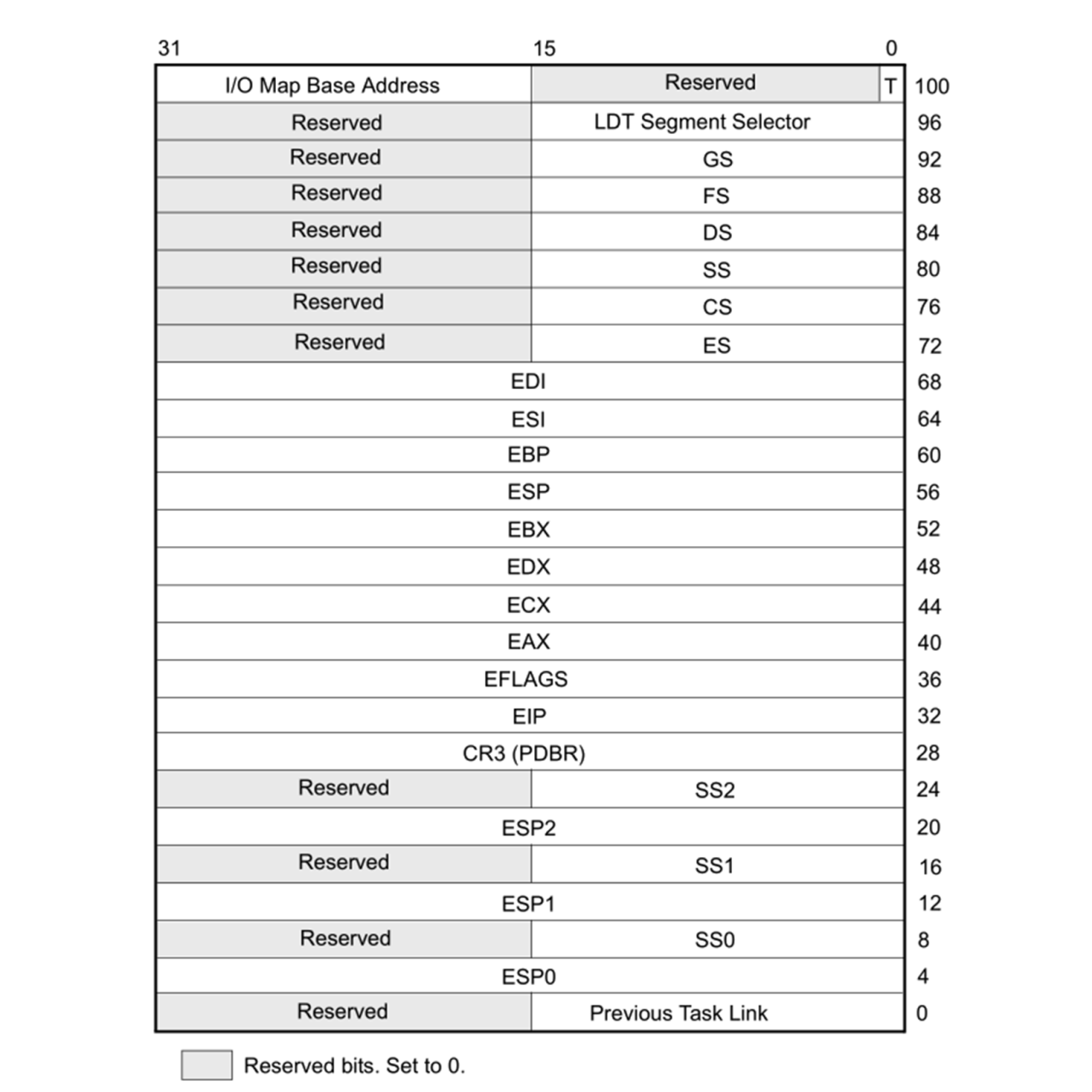

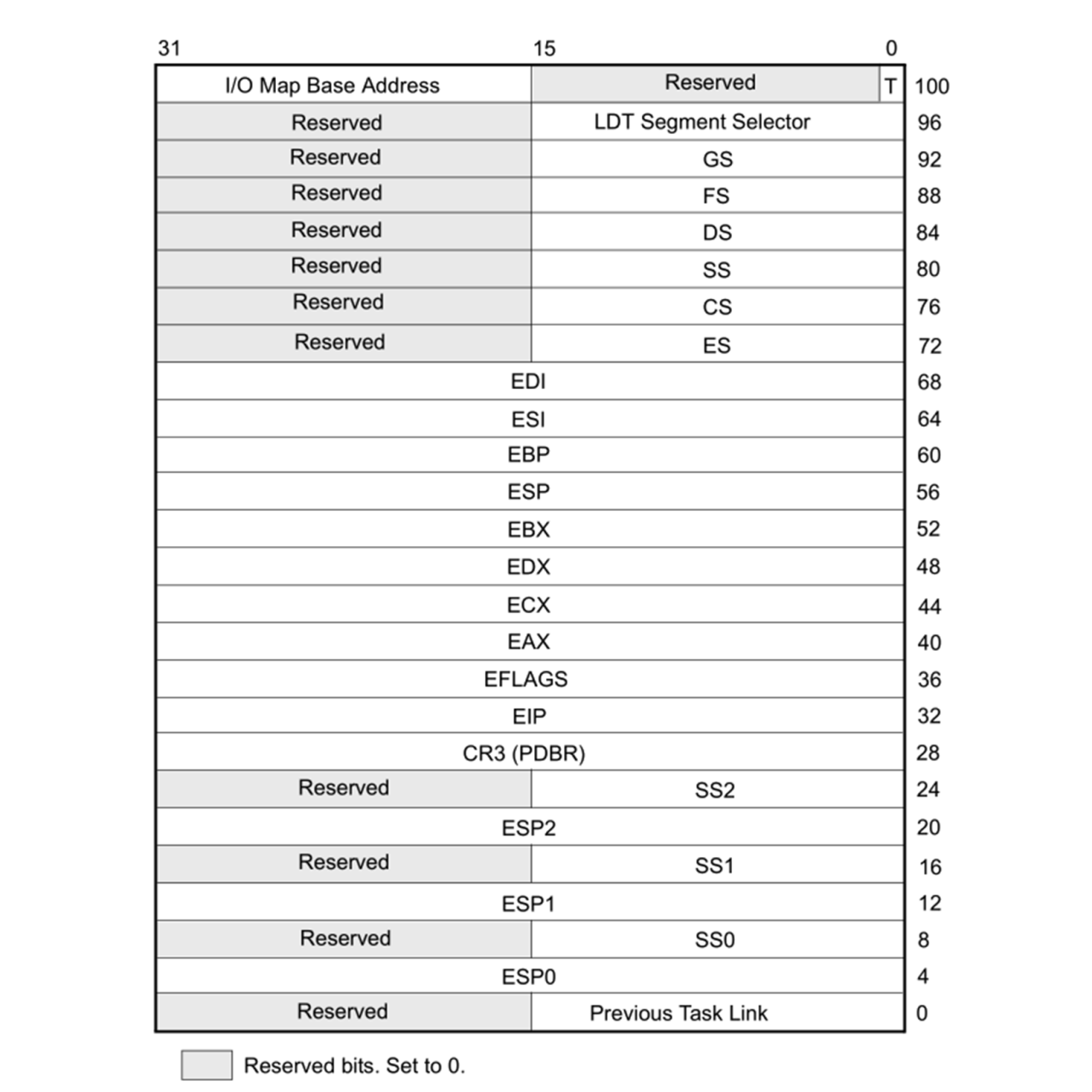

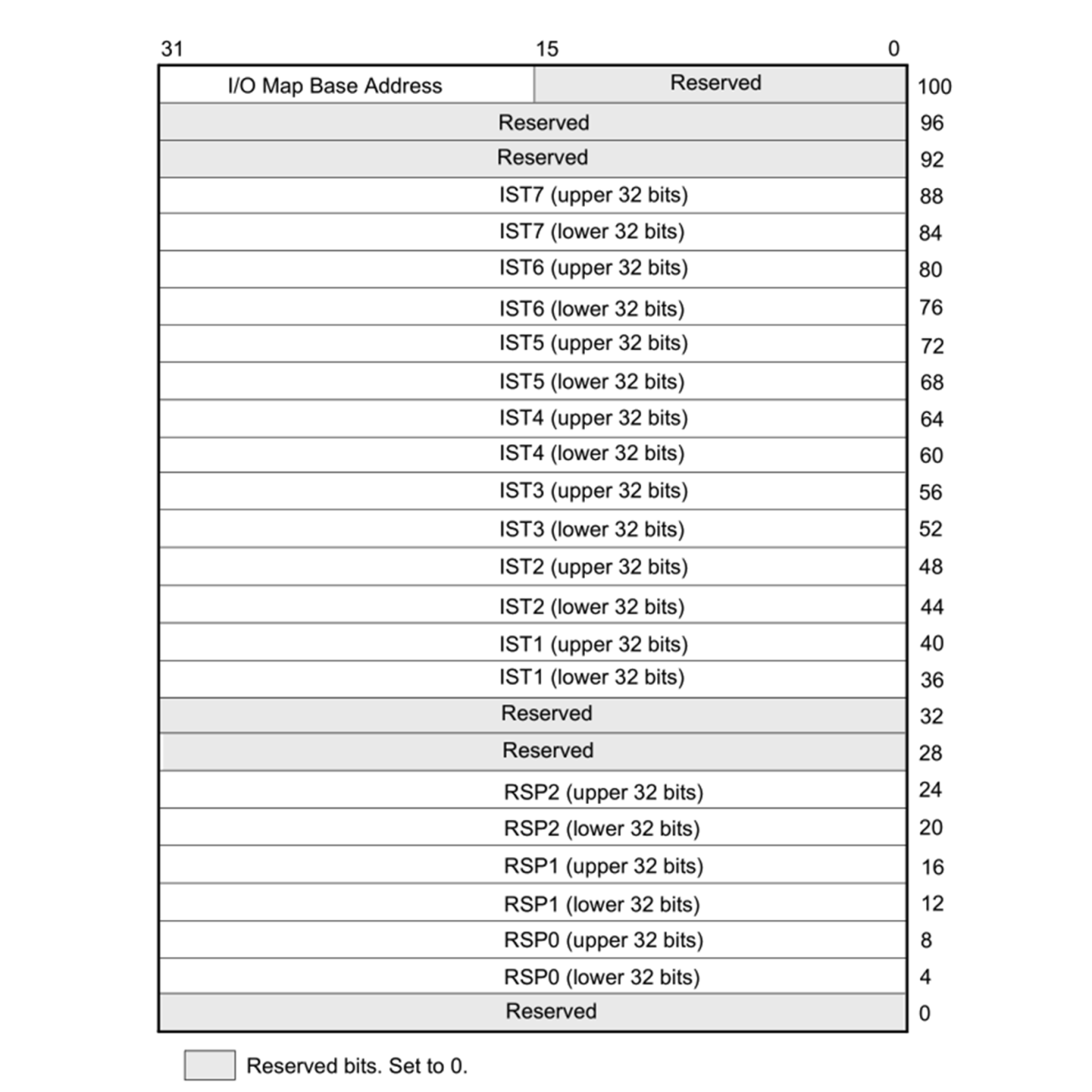

The task structure for both 32-bit and 64-bit tasks are quite similar in concept. The official name for it is the Task State Structure (TSS). It has the following layout for 32-bit x86 CPUs:

Following are the firlds:

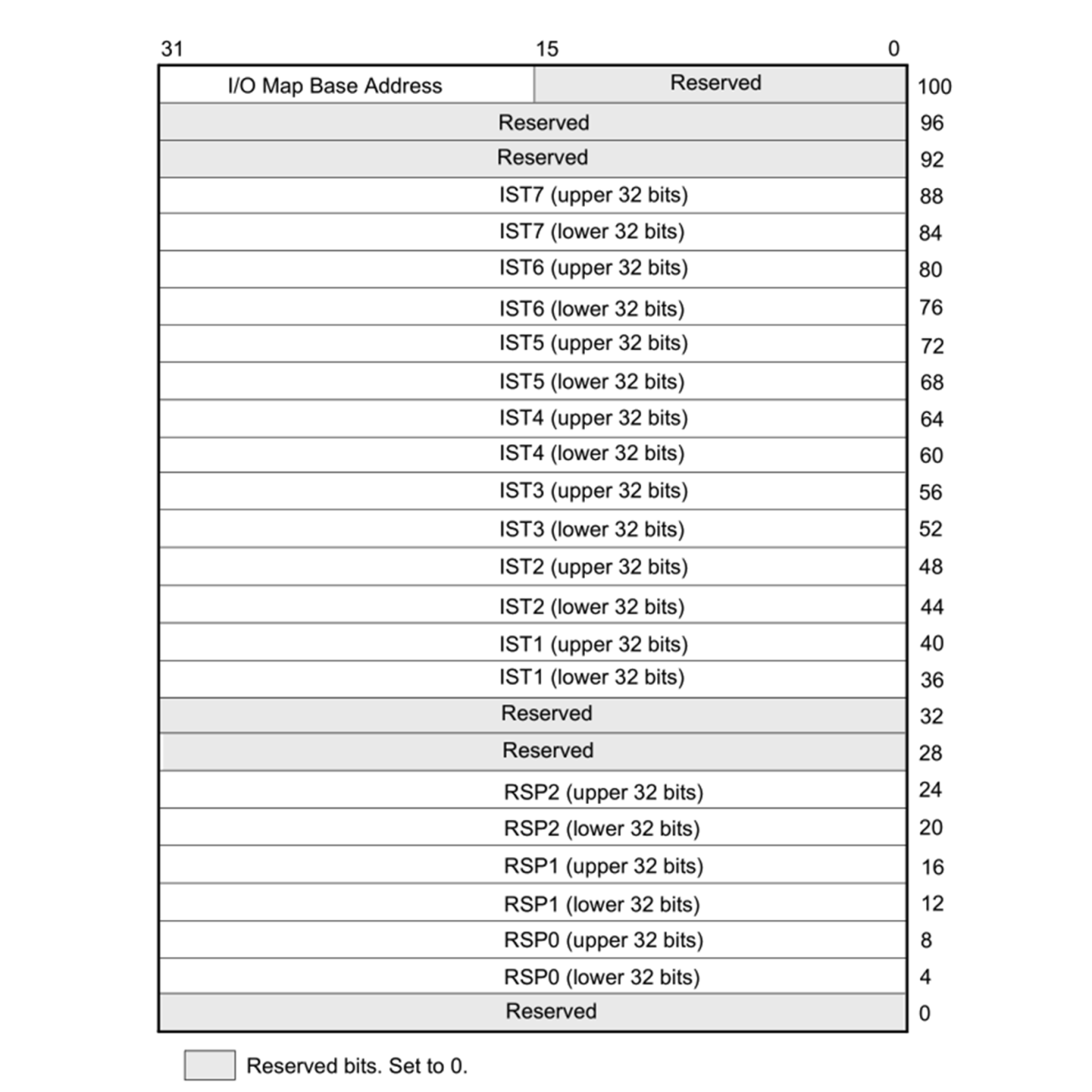

For 64-bit x86_64 CPUs, the TSS layout looks somewhat different, since hardware-based task switching is not supported in this mode:

Here, we have similar relevant fields, just with different names:

Even though on x86 in 32-bit mode, the CPU supports hardware-based switching between tasks, most operating systems will use just a single TSS structure per CPU regardless of the mode, and do the actual switching between tasks in software. This is partially due to efficiency reasons (swapping out only pointers which change), partially due to features which are only possible this way, such as measuring CPU time used by a process/thread, and to adjust the priority of a thread or process. Doing it in software also simplifies the portability of code between 64-bit and 32-bit systems, since the former do not support hardware-based task switching.

During a software-based task switch (usually via an interrupt), the ESP/RSP, and so on are stored in memory and replaced with the values for the next scheduled task. This means that once execution resumes, the TSS structure will now have the Stack Pointer (SP), segment pointer(s), register contents, and all other details of the new task.

The source of the interrupt can be based in hardware or software. A hardware interrupt is usually used by devices to signal to the CPU that they require attention by the OS. The act of calling a hardware interrupt is called an Interrupt Request, or IRQ.

A software interrupt can be due to an exceptional condition in the CPU itself, or as a feature of the CPU's instruction set. The action of switching tasks by the OS's kernel is also performed by triggering a software interrupt.

In ARM architectures, applications usually run in the unprivileged Exception Level 0 (EL0) level, which is comparable to ring 3 on x86 architectures, and the OS kernel in EL1. The ARMv7 (AArch32, 32-bit) architecture has the SP in the general purpose register 13. For ARMv8 (AArch64, 64-bit), a dedicated SP register is implemented for each exception level: SP_EL0, SP_EL1, and so on.

For task state, the ARM architecture uses Program State Register (PSR) instances for the Current Program State Register (CPSR) or the Saved Program State Register (SPSR) program state's registers. The PSR is part of the Process State (PSTATE), which is an abstraction of the process state information.

While the ARM architecture is significantly different from the x86 architecture, when using software-based task switching, the basic principle does not change: save the current task's SP, register state, and put the next task's detail in there instead before resuming processing.

As we saw in the preceding sections, the stack together with the CPU registers define a task. As mentioned earlier, this stack consists of stack frames, each of which defines the (local) variables, parameters, data, and instructions for that particular instance of task execution. Of note is that although the stack and stack frames are primarily a software concept, it is an essential feature of any modern OS, with hardware support in many CPU instruction sets. Graphically, it can be be visualized like the following:

The SP (ESP on x86) points to the top of the stack, with another pointer (Extended Base Pointer (EBP) for x86). Each frame contains a reference to the preceding frame (caller return address), as set by the OS.

When using a debugger with one's C++ application, this is basically what one sees when requesting the backtrack--the individual frames of the stack showing the initial stack frame leading up until the current frame. Here, one can examine each individual frame's details.

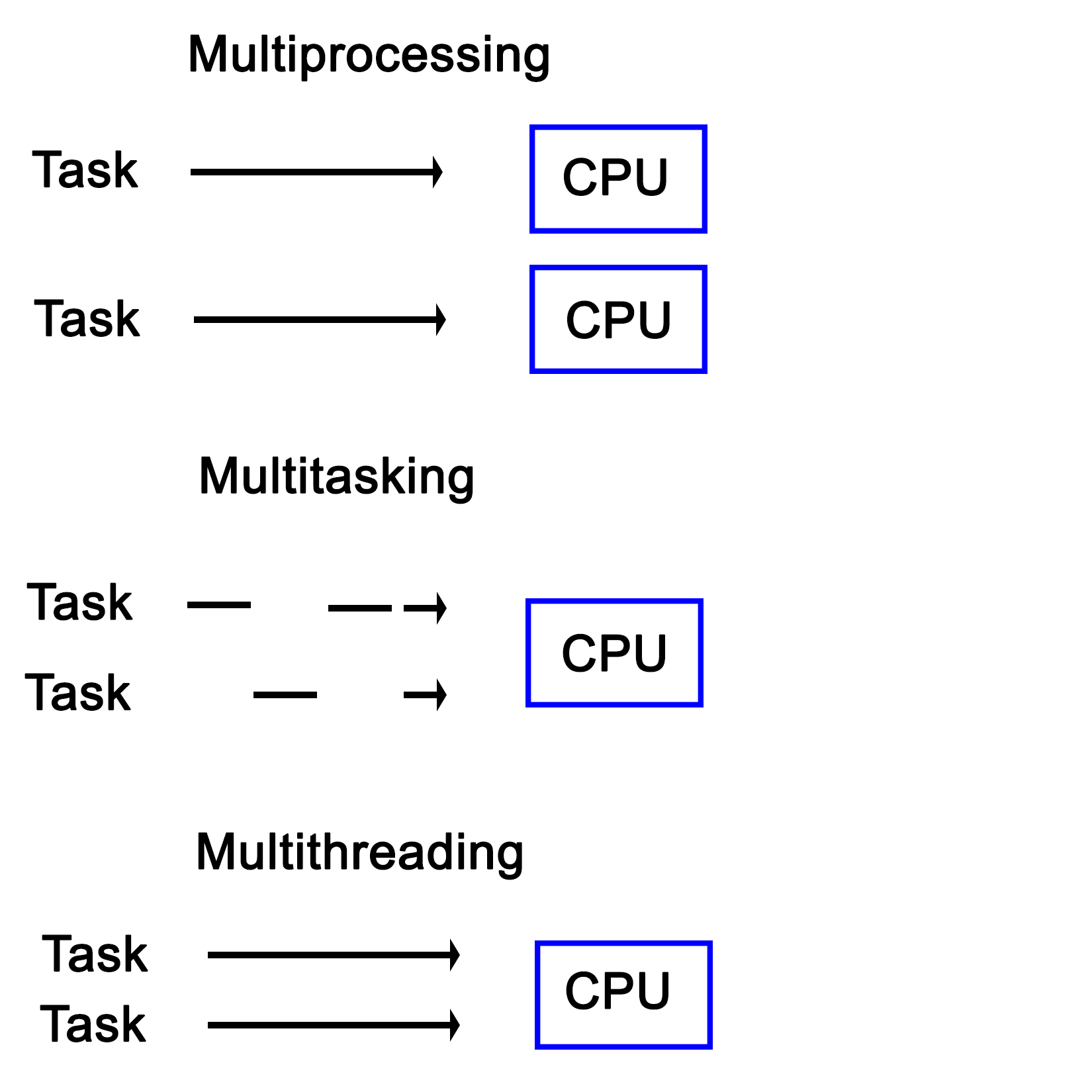

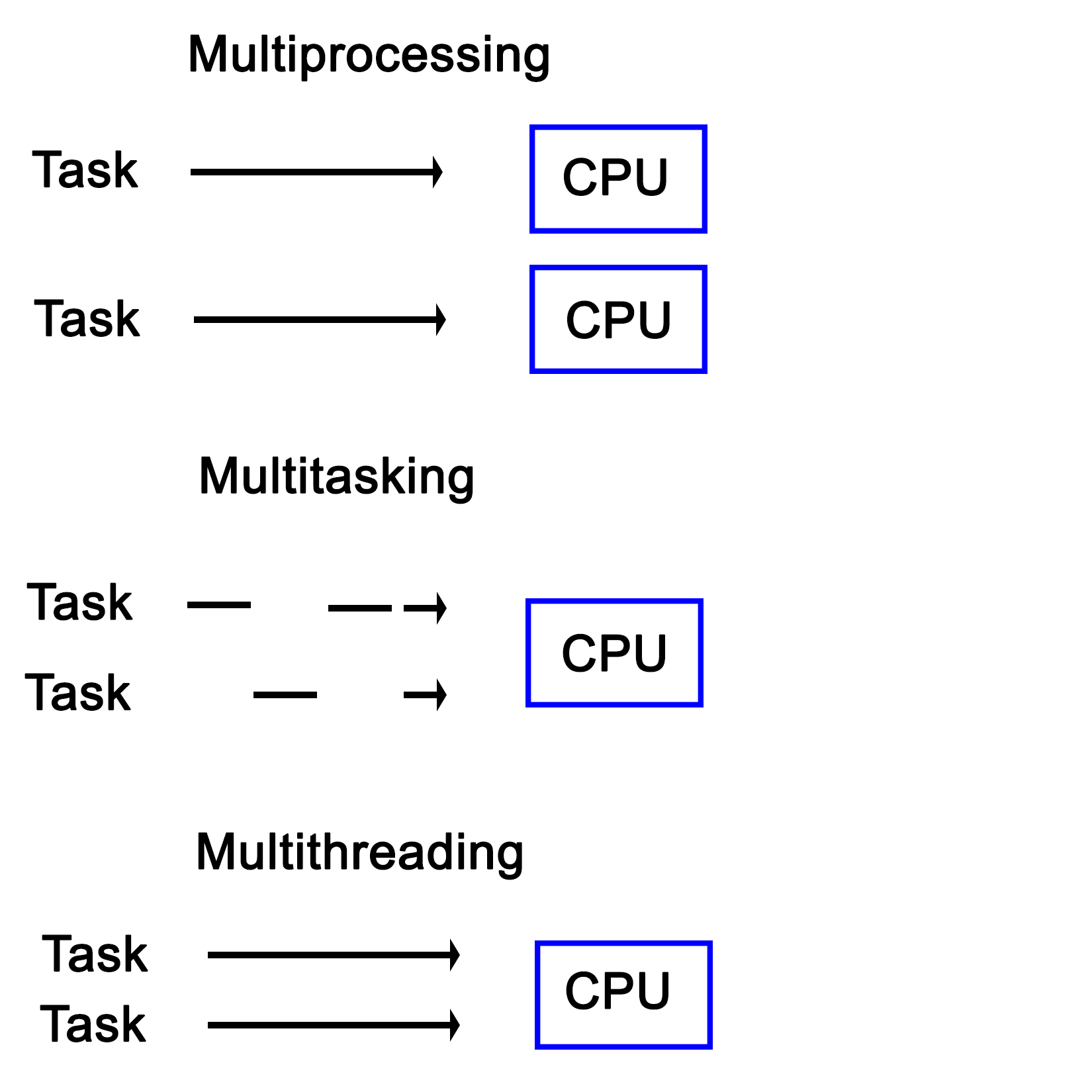

Over the past decades, a lot of different terms related to the way tasks are processed by a computer have been coined and come into common use. Many of these are also used interchangeably, correctly or not. An example of this is multithreading in comparison with multiprocessing.

Here, the latter means running one task per processor in a system with multiple physical processors, while the former means running multiple tasks on a singular processor simultaneously, thus giving the illusion that they are all being executed simultaneously:

Another interesting distinction between multiprocessing and multitasking is that the latter uses time-slices in order to run multiple threads on a single processor core. This is different from multithreading in the sense that in a multitasking system, no tasks will ever run in a concurrent fashion on the same CPU core, though tasks can still be interrupted.

The concept of a process and a shared memory space between the threads contained within the said process is at the very core of multithreaded systems from a software perspective. Though the hardware is often not aware of this--seeing just a single task to the OS. However, such a multithreaded process contains two or many more threads. Each of these threads then perform its own series of tasks.

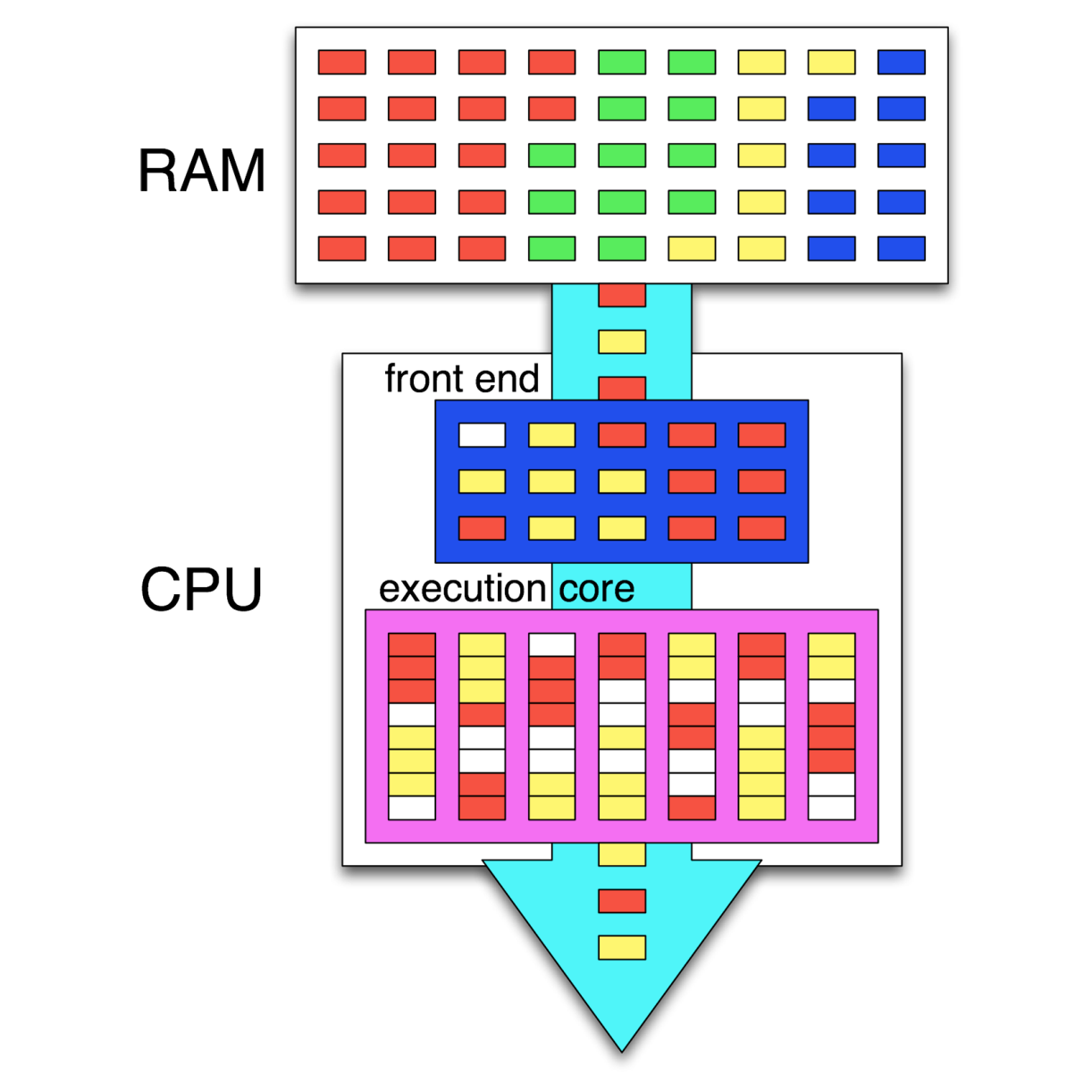

In other implementations, such as Intel's Hyper-Threading (HT) on x86 processors, this multithreading is implemented in the hardware itself, where it's commonly referred to as SMT (see the section Simultaneous multithreading (SMT) for details). When HT is enabled, each physical CPU core is presented to the OS as being two cores. The hardware itself will then attempt to execute the tasks assigned to these so-called virtual cores concurrently, scheduling operations which can use different elements of a processing core at the same time. In practice, this can give a noticeable boost in performance without the operating system or application requiring any type of optimization.

The OS can of course still do its own scheduling to further optimize the execution of task, since the hardware is not aware of many details about the instructions it is executing.

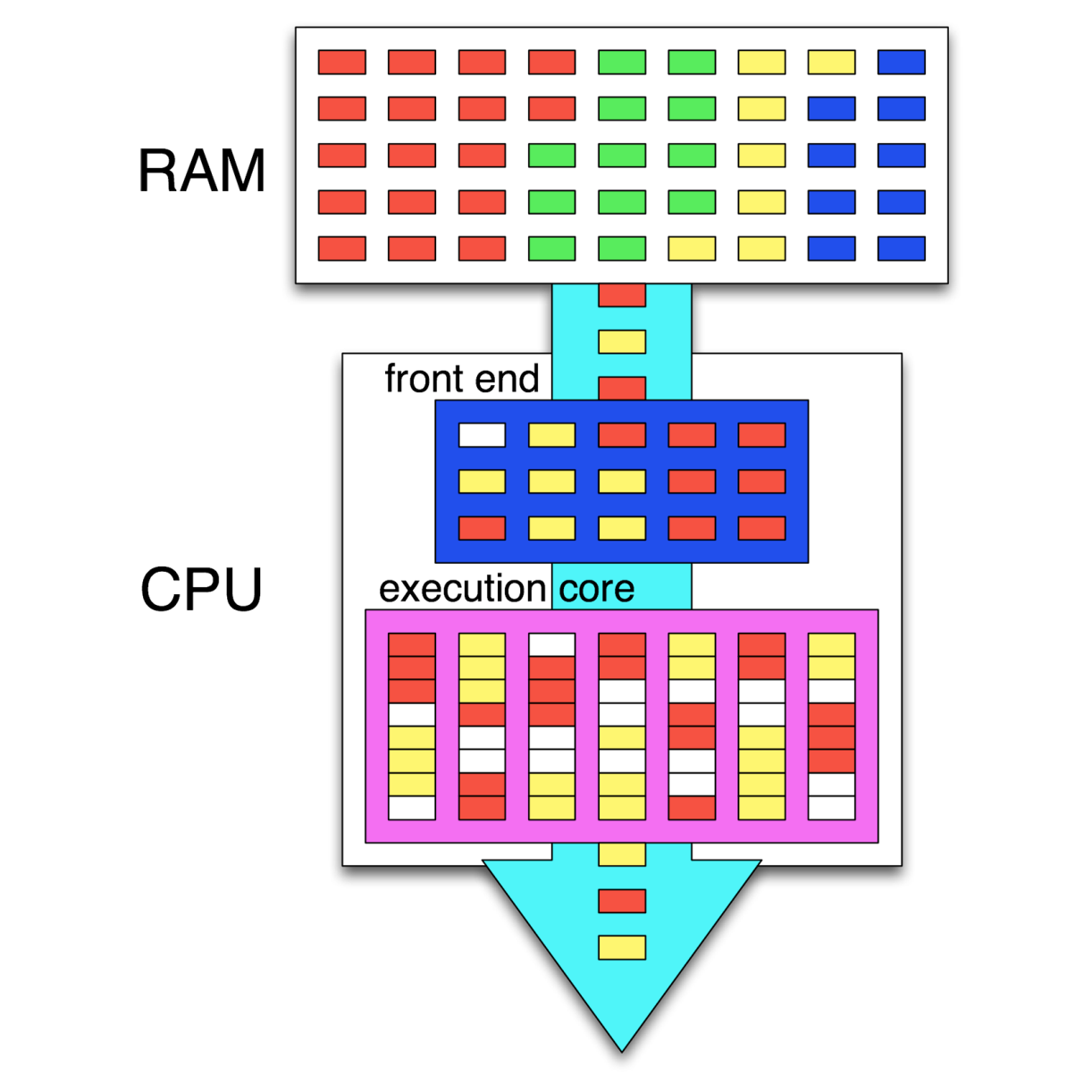

Having HT enabled looks like this in the visual format:

In this preceding graphic, we see the instructions of four different tasks in memory (RAM). Out of these, two tasks (threads) are being executed simultaneously, with the CPU's scheduler (in the frontend) attempting to schedule the instructions so that as many instructions as possible can be executed in parallel. Where this is not possible, so-called pipeline bubbles (in white) appear where the execution hardware is idle.

Together with internal CPU optimizations, this leads to a very high throughput of instructions, also called Instructions Per Second (IPC). Instead of the GHz rating of a CPU, this IPC number is generally far more significant for determining the sheer performance of a CPU.

Different types of computer architecture are classified using a system which was first proposed by Michael J. Flynn, back in 1966. This classification system knows four categories, defining the capabilities of the processing hardware in terms of the number of input and output streams:

An important thing to note with these categories is that they are all defined in terms of multiprocessing, meaning that they refer to the intrinsic capabilities of the hardware. Using software techniques, virtually any method can be approximated on even a regular SISD-style architecture. This is, however, part of multithreading.

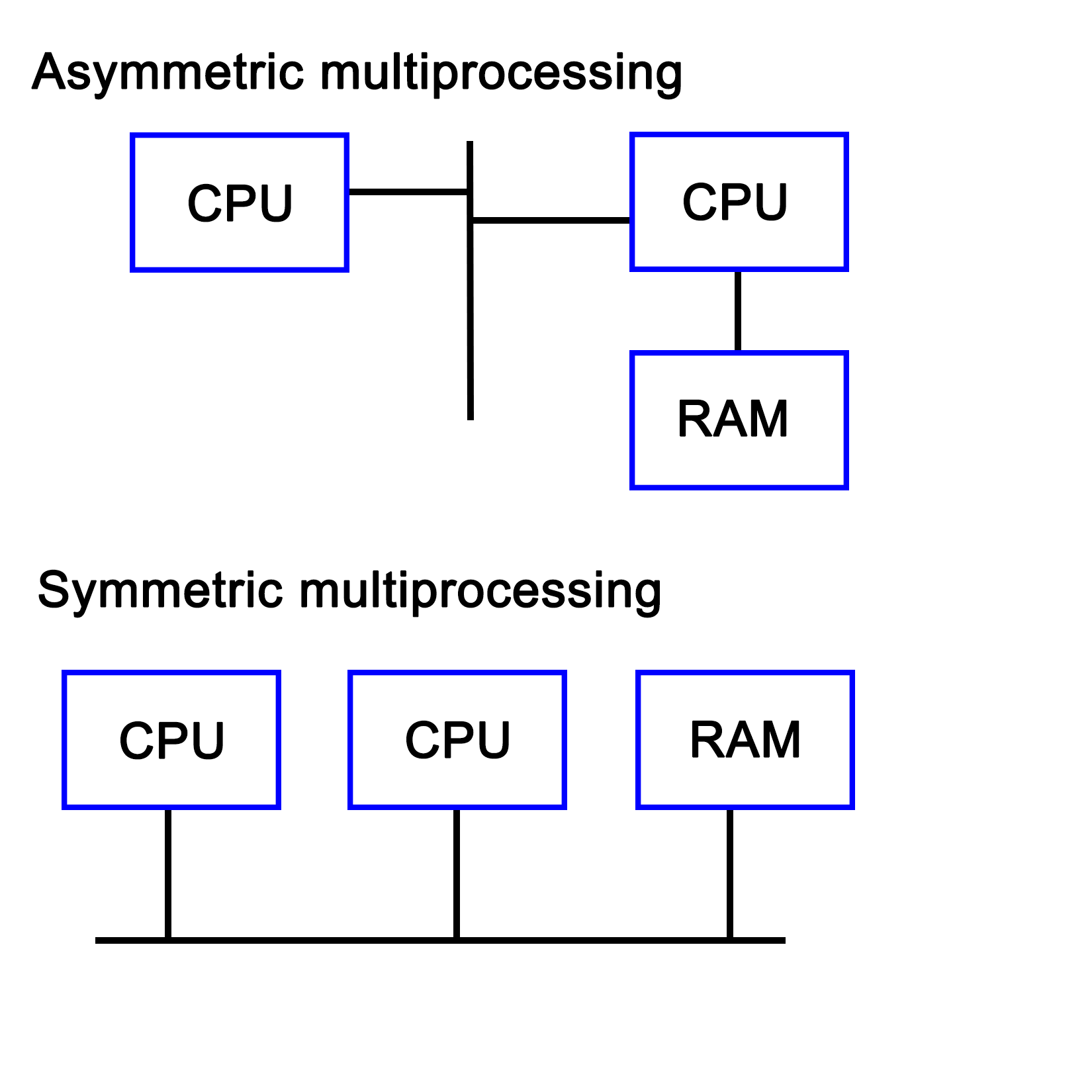

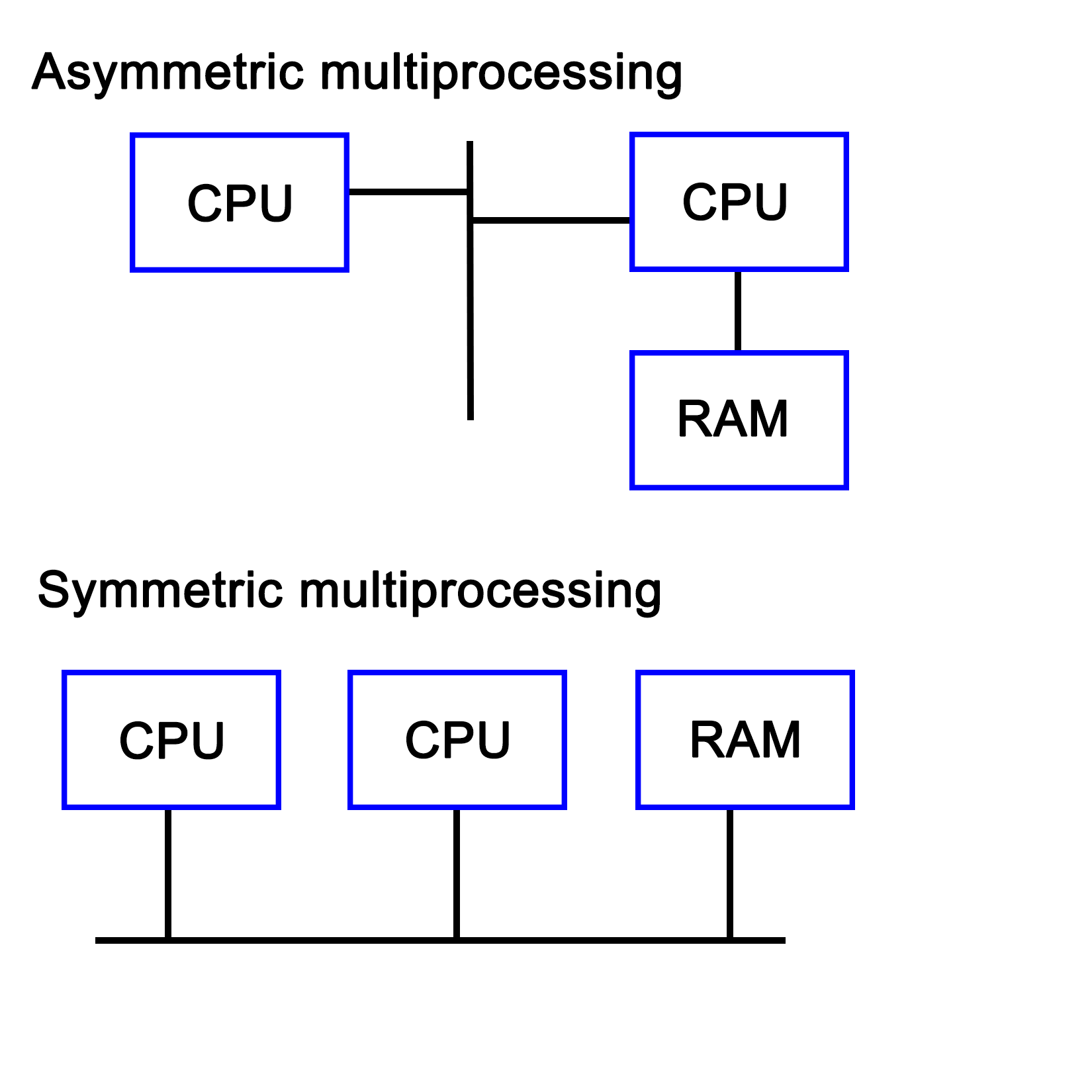

Over the past decades, many systems were created which contained multiple processing units. These can be broadly divided into Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP) and Asymmetric Multiprocessing (AMP) systems.

AMP's main defining feature is that a second processor is attached as a peripheral to the primary CPU. This means that it cannot run control software, but only user applications. This approach has also been used to connect CPUs using a different architecture to allow one to, for example, run x86 applications on an Amiga, 68k-based system.

With an SMP system, each of the CPUs are peers having access to the same hardware resources, and set up in a cooperative fashion. Initially, SMP systems involved multiple physical CPUs, but later, multiple processor cores got integrated on a single CPU die:

With the proliferation of multi-core CPUs, SMP is the most common type of processing outside of embedded development, where uniprocessing (single core, single processor) is still very common.

Technically, the sound, network, and graphic processors in a system can be considered to be asymmetric processors related to the CPU. With an increase in General Purpose GPU (GPGPU) processing, AMP is becoming more relevant.

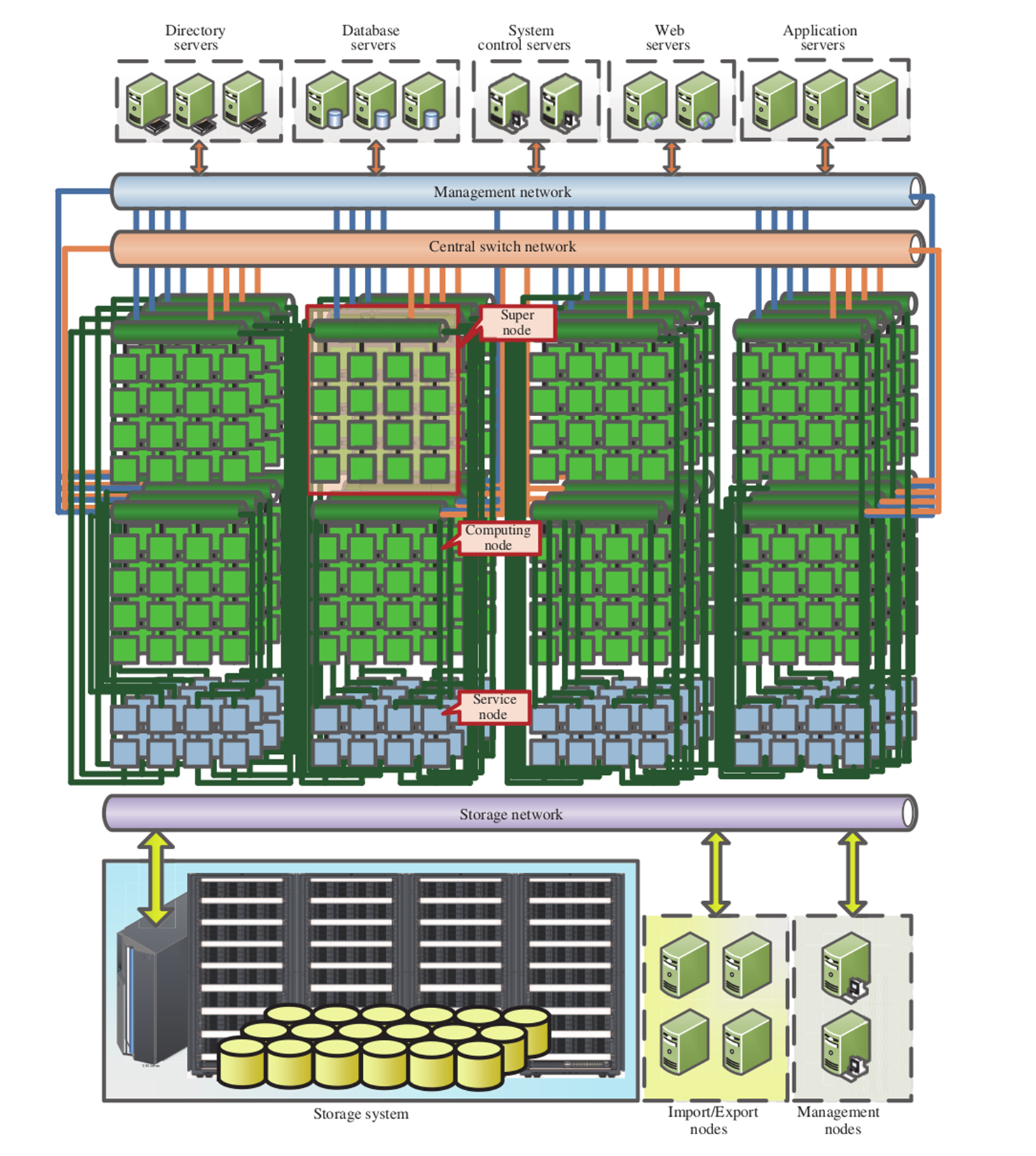

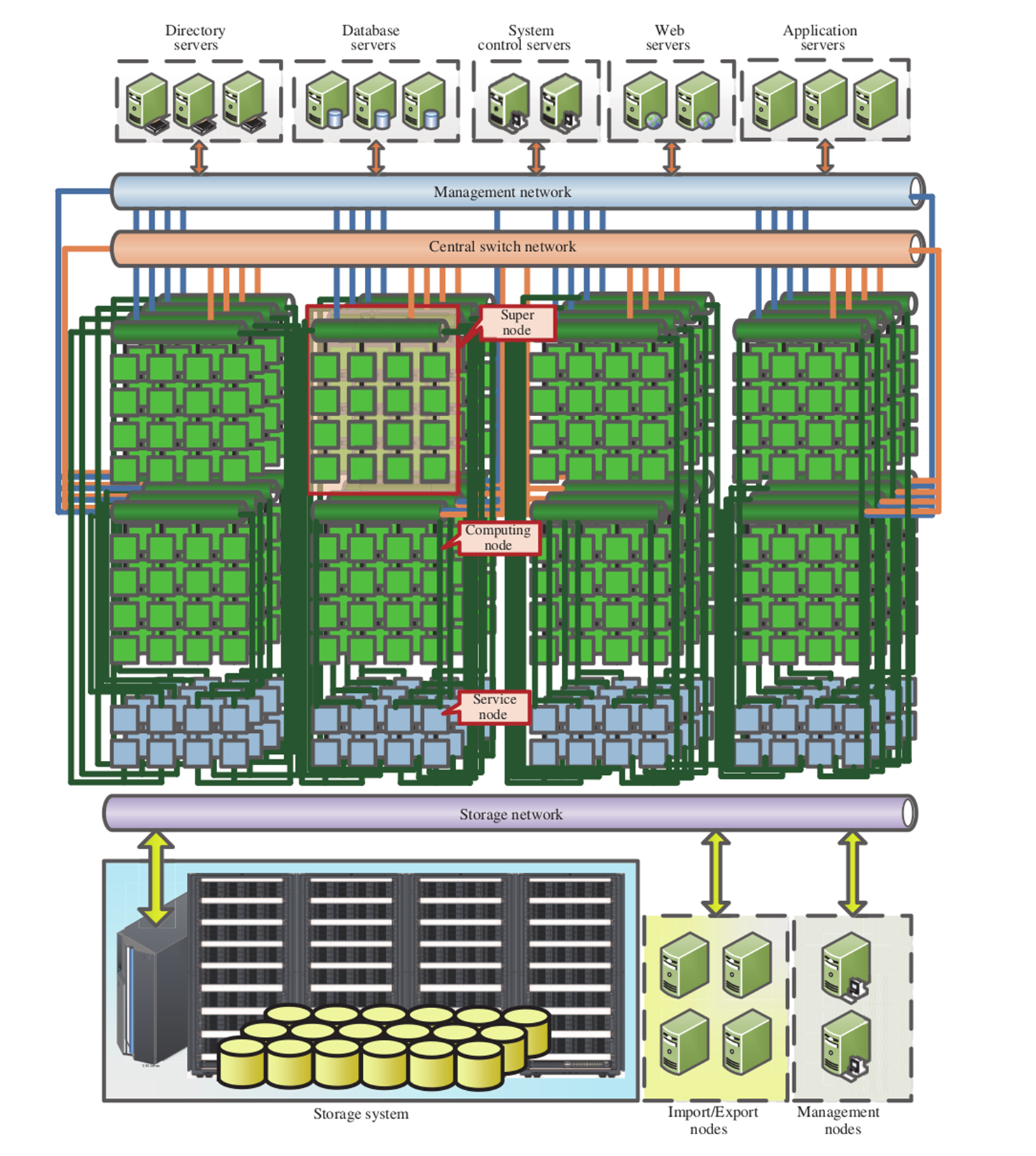

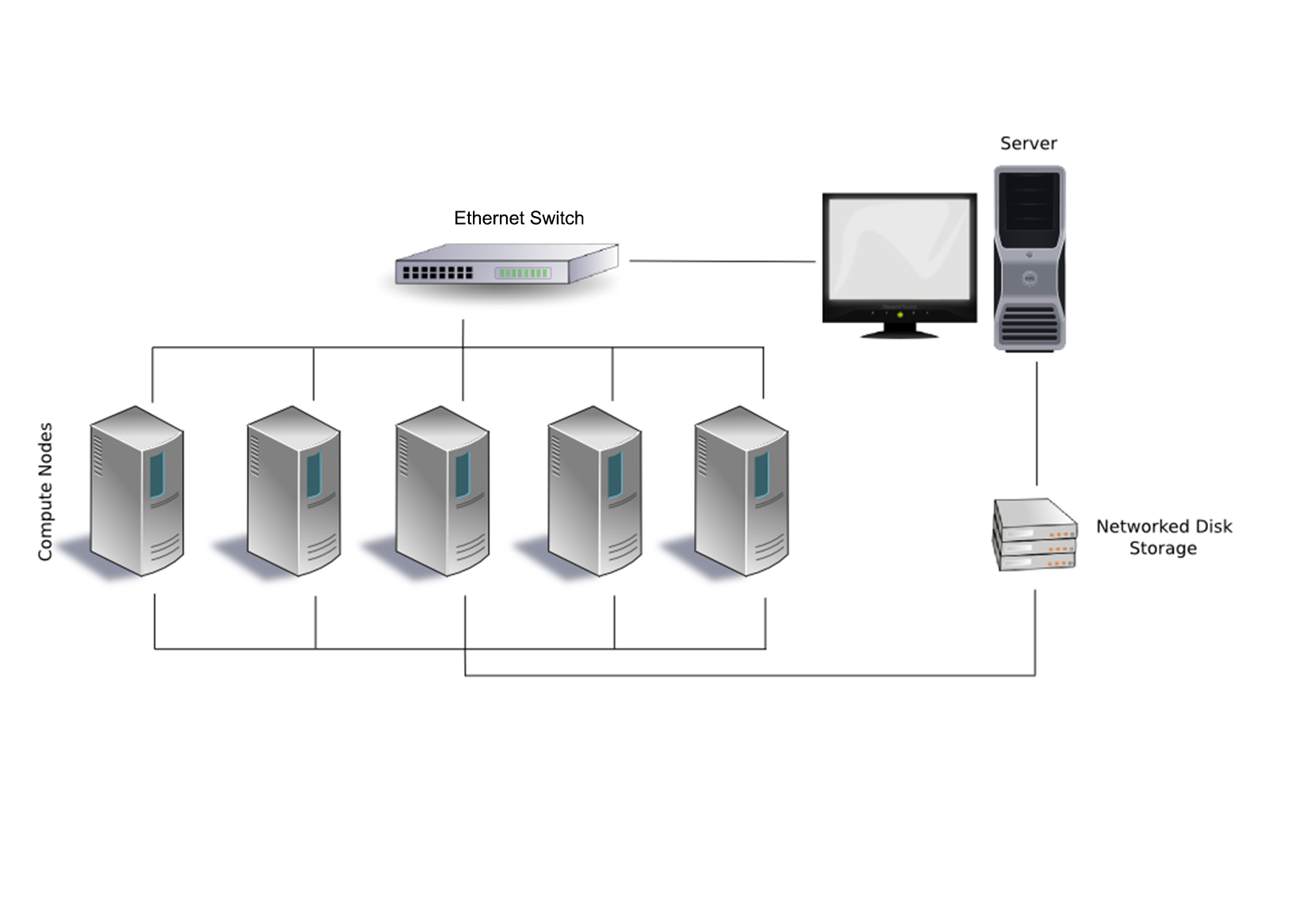

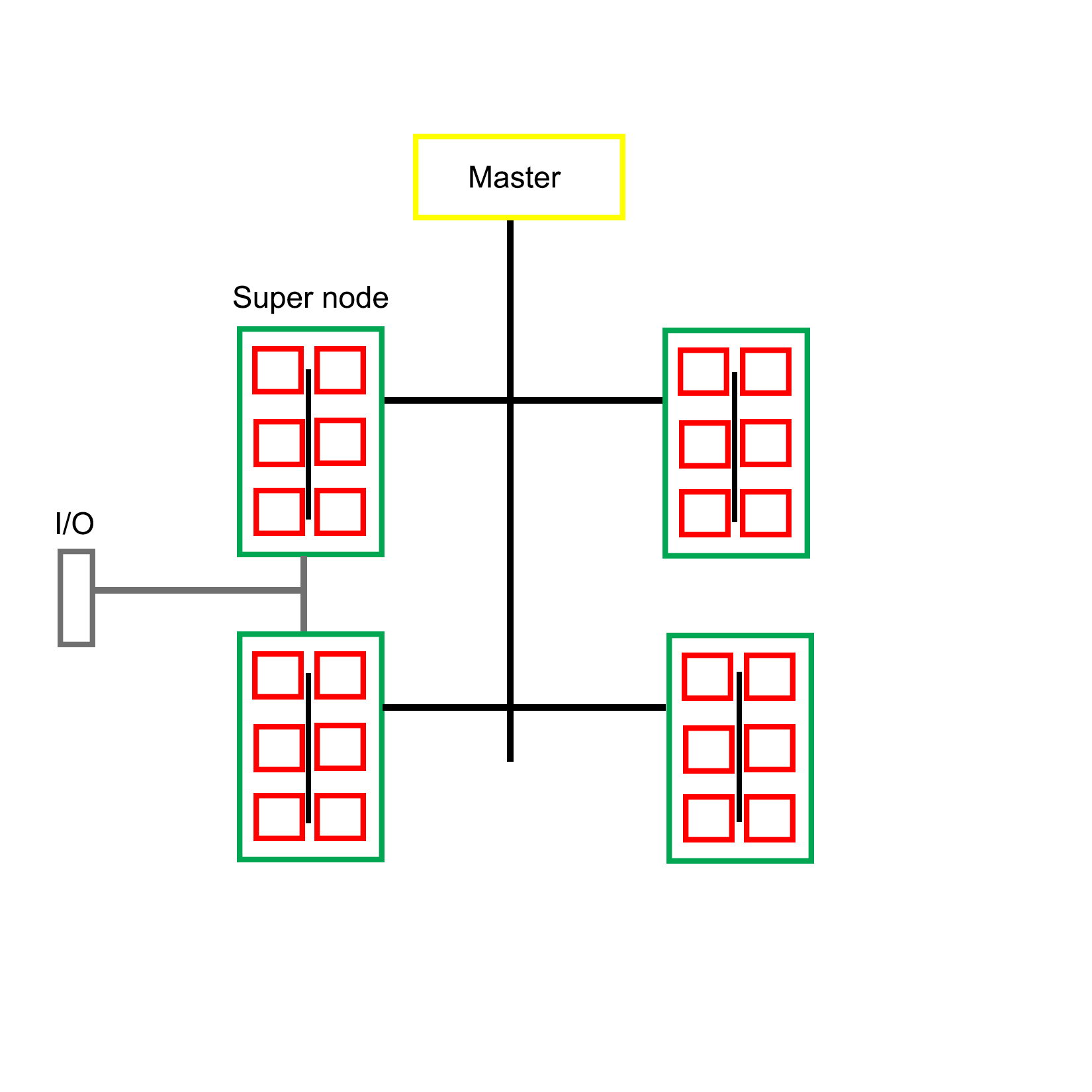

A multiprocessing system does not necessarily have to be implemented within a single system, but can also consist of multiple systems which are connected in a network. Such a cluster is then called a loosely coupled multiprocessing system. We cover distributing computing in Chapter 9, Multithreading with Distributed Computing.

This is in contrast with a tightly coupled multiprocessing system, whereby the system is integrated on a single printed circuit board (PCB), using the same low-level, high-speed bus or similar.

Virtually any modern system combines multiprocessing with multithreading, courtesy of multi-core CPUs, which combine two or more processing cores on a single processor die. What this means for an operating system is that it has to schedule tasks both across multiple processing cores while also scheduling them on specific cores in order to extract maximum performance.

This is the area of task schedulers, which we will look at in a moment. Suffice it to say that this is a topic worthy of its own book.

Like multiprocessing, there is not a single implementation, but two main ones. The main distinction between these is the maximum number of threads the processor can execute concurrently during a single cycle. The main goal of a multithreading implementation is to get as close to 100% utilization of the processor hardware as reasonably possible. Multithreading utilizes both thread-level and process-level parallelism to accomplish this goal.

The are two types of multithreading, which we will cover in the following sections.

Also known as super-threading, the main subtypes for temporal multithreading (TMT) are coarse-grained and fine-grained (or interleaved). The former switches rapidly between different tasks, saving the context of each before switching to another task's context. The latter type switches tasks with each cycle, resulting in a CPU pipeline containing instructions from various tasks from which the term interleaved is derived.

The fine-grained type is implemented in barrel processors. They have an advantage over x86 and other architectures that they can guarantee specific timing (useful for hard real-time embedded systems) in addition to being less complex to implement due to assumptions that one can make.

SMT is implemented on superscalar CPUs (implementing instruction-level parallelism), which include the x86 and ARM architectures. The defining characteristic of SMT is also indicated by its name, specifically, its ability to execute multiple threads in parallel, per core.

Generally, two threads per core is common, but some designs support up to eight concurrent threads per core. The main advantage of this is being able to share resources among threads, with an obvious disadvantage of conflicting needs by multiple threads, which has to be managed. Another advantage is that it makes the resulting CPU more energy efficient due to a lack of hardware resource duplication.

Intel's HT technology is essentially Intel's SMT implementation, providing a basic two thread SMT engine starting with some Pentium 4 CPUs in 2002.

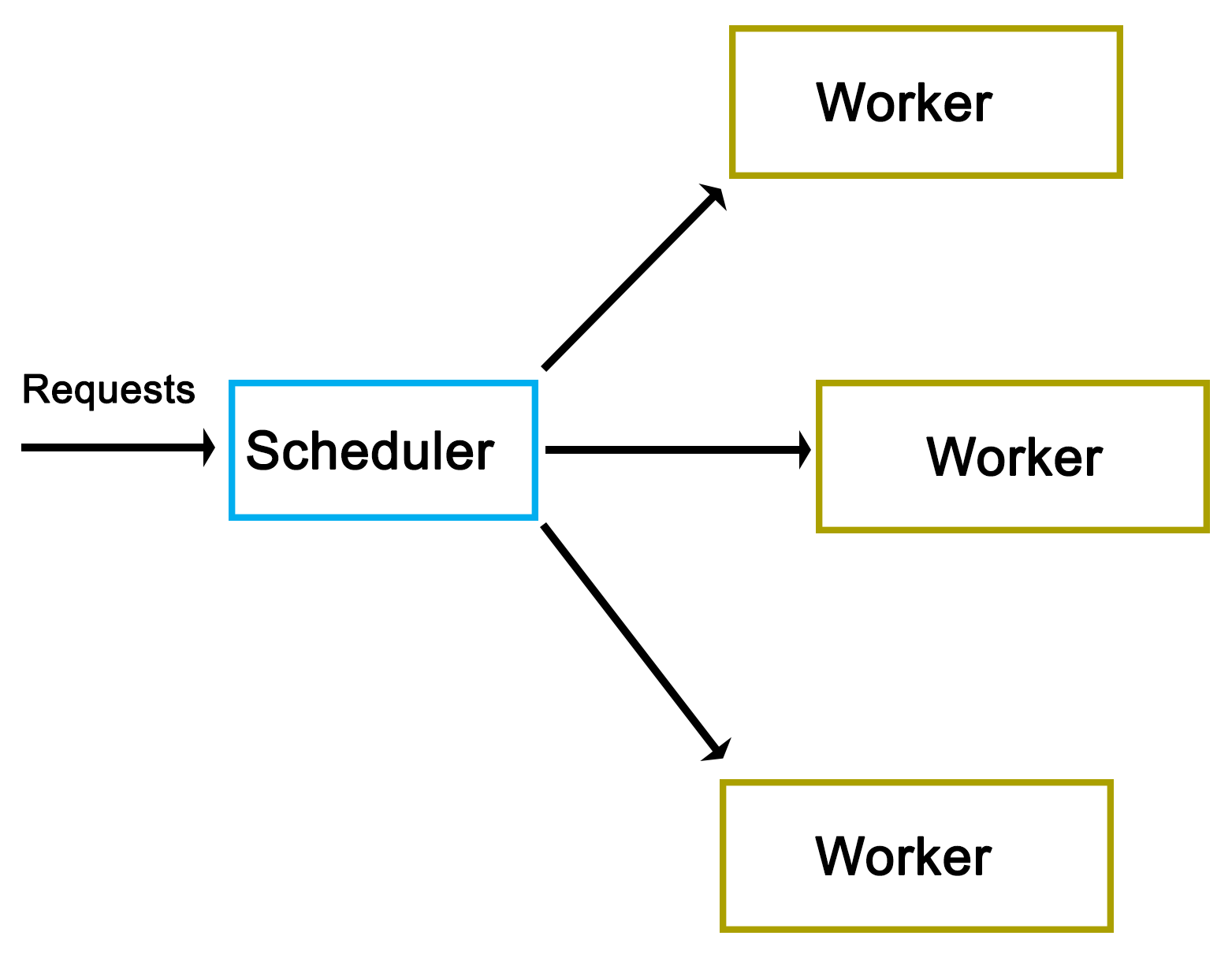

A number of task-scheduling algorithms exist, each focusing on a different goal. Some may seek to maximize throughput, others minimize latency, while others may seek to maximize response time. Which scheduler is the optimal choice solely depends on the application the system is being used for.

For desktop systems, the scheduler is generally kept as general-purpose as possible, usually prioritizing foreground applications over background applications in order to give the user the best possible desktop experience.

For embedded systems, especially in real-time, industrial applications would instead seek to guarantee timing. This allows processes to be executed at exactly the right time, which is crucial in, for example, driving machinery, robotics, or chemical processes where a delay of even a few milliseconds could be costly or even fatal.

The scheduler type is also dependent on the multitasking state of the OS--a cooperative multitasking system would not be able to provide many guarantees about when it can switch out a running process for another one, as this depends on when the active process yields.

With a preemptive scheduler, processes are switched without them being aware of it, allowing the scheduler more control over when processes run at which time points.

Windows NT-based OSes (Windows NT, 2000, XP, and so on) use what is called a multilevel feedback queue, featuring 32 priority levels. This type of priority scheduler allows one to prioritize tasks over other tasks, allowing one to fine-tune the resulting experience.

Linux originally (kernel 2.4) also used a multilevel feedback queue-based priority scheduler like Windows NT with an O(n) scheduler. With version 2.6, this was replaced with an O(1) scheduler, allowing processes to be scheduled within a constant amount of time. Starting with Linux kernel 2.6.23, the default scheduler is the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), which ensures that all tasks get a comparable share of CPU time.

The type of scheduling algorithm used for a number of commonly used or well-known OSes is listed in this table:

|

Operating System |

Preemption |

Algorithm |

|

Amiga OS |

Yes |

Prioritized round-robin scheduling |

|

FreeBSD |

Yes |

Multilevel feedback queue |

|

Linux kernel before 2.6.0 |

Yes |

Multilevel feedback queue |

|

Linux kernel 2.6.0-2.6.23 |

Yes |

O(1) scheduler |

|

Linux kernel after 2.6.23 |

Yes |

Completely Fair Scheduler |

|

classic Mac OS pre-9 |

None |

Cooperative scheduler |

|

Mac OS 9 |

Some |

Preemptive scheduler for MP tasks, and cooperative for processes and threads |

|

OS X/macOS |

Yes |

Multilevel feedback queue |

|

NetBSD |

Yes |

Multilevel feedback queue |

|

Solaris |

Yes |

Multilevel feedback queue |

|

Windows 3.1x |

None |

Cooperative scheduler |

|

Windows 95, 98, Me |

Half |

Preemptive scheduler for 32-bit processes, and cooperative for 16-bit processes |

|

Windows NT (including 2000, XP, Vista, 7, and Server) |

Yes |

Multilevel feedback queue |

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scheduling_(computing))

The preemptive column indicates whether the scheduler is preemptive or not, with the next column providing further details. As one can see, preemptive schedulers are very common, and used by all modern desktop operating systems.

In the demonstration code of Chapter 1, Revisiting Multithreading, we looked at a simple c++11 application which used four threads to perform some processing. In this section, we will look at the same application, but from a hardware and OS perspective.

When we look at the start of the code in the main function, we see that we create a data structure containing a single (integer) value:

int main() {

values.push_back(42);

After the OS creates a new task and associated stack structure, an instance of a vector data structure (customized for integer types) is allocated on the stack. The size of this was specified in the binary file's global data section (BSS for ELF).

When the application's execution is started using its entry function (main() by default), the data structure is modified to contain the new integer value.

Next, we create four threads, providing each with some initial data:

thread tr1(threadFnc, 1);

thread tr2(threadFnc, 2);

thread tr3(threadFnc, 3);

thread tr4(threadFnc, 4);

For the OS, this means creating new data structures, and allocating a stack for each new thread. For the hardware, this initially does not change anything if no hardware-based task switching is used.

At this point, the OS's scheduler and the CPU can combine to execute this set of tasks (threads) as efficiently and quickly as possible, employing features of the hardware including SMP, SMT, and so on.

After this, the main thread waits until the other threads stop executing:

tr1.join();

tr2.join();

tr3.join();

tr4.join();

These are blocking calls, which mark the main thread as being blocked until these four threads (tasks) finish executing. At this point, the OS's scheduler will resume execution of the main thread.

In each newly created thread, we first output a string on the standard output, making sure that we lock the mutex to ensure synchronous access:

void threadFnc(int tid) {

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Starting thread " << tid << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

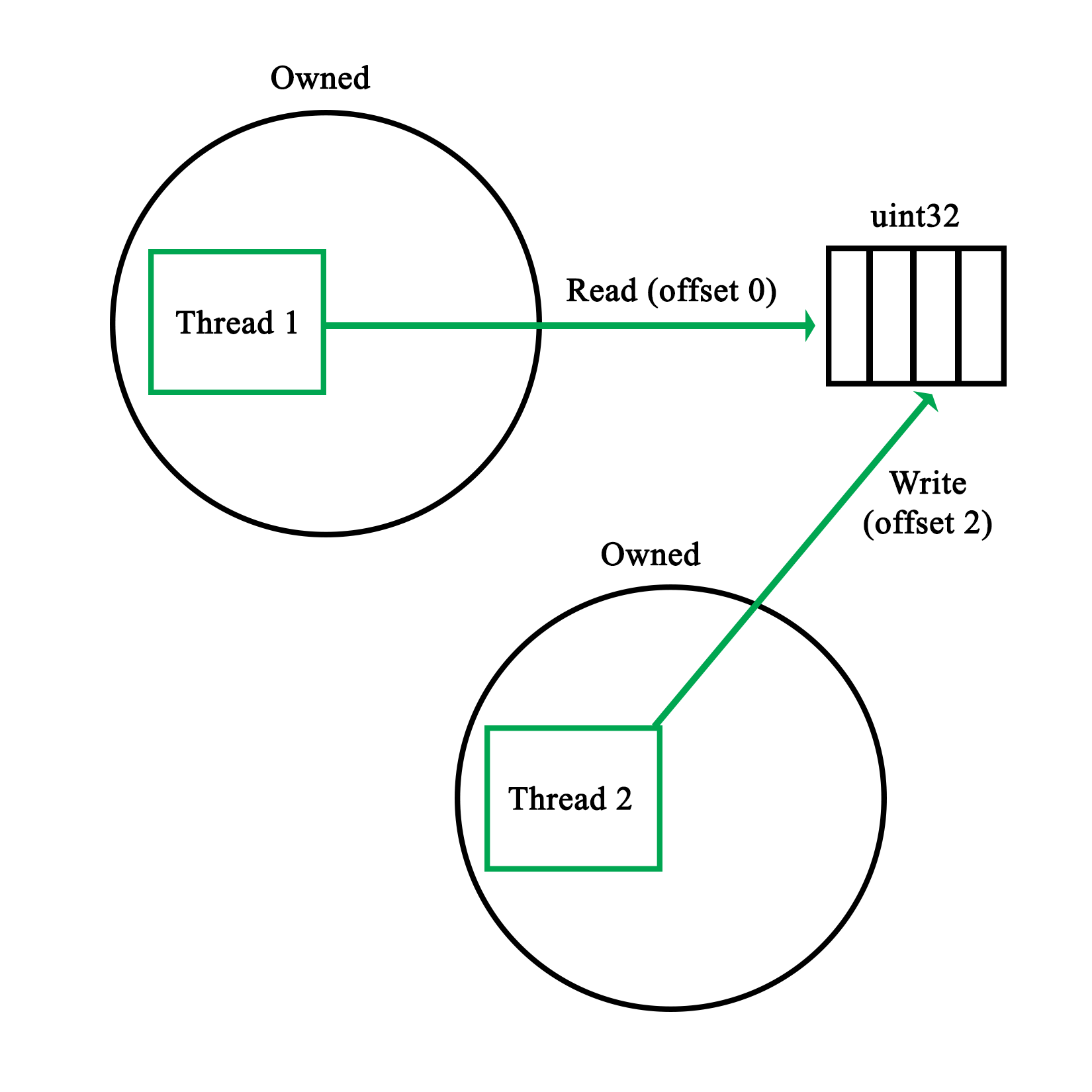

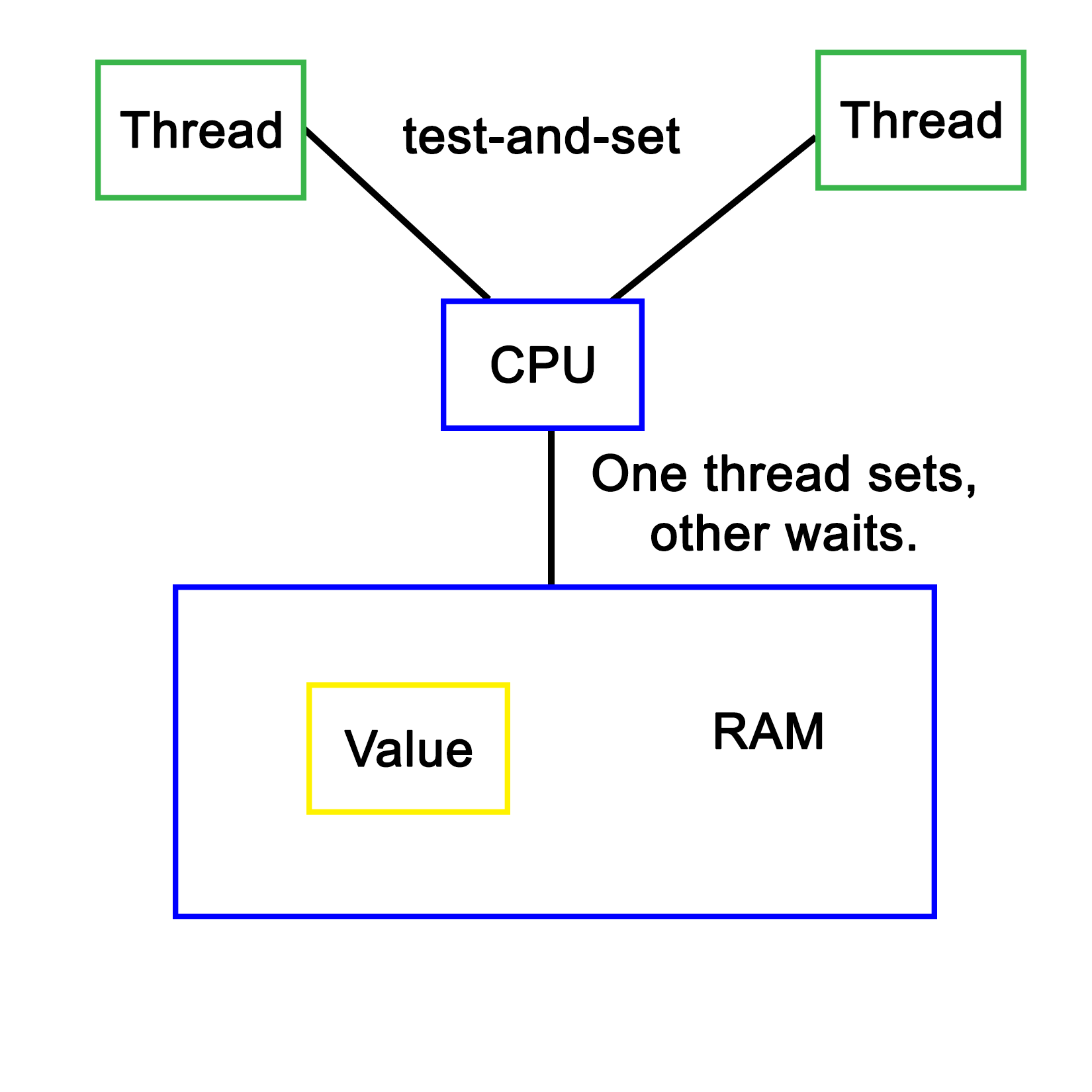

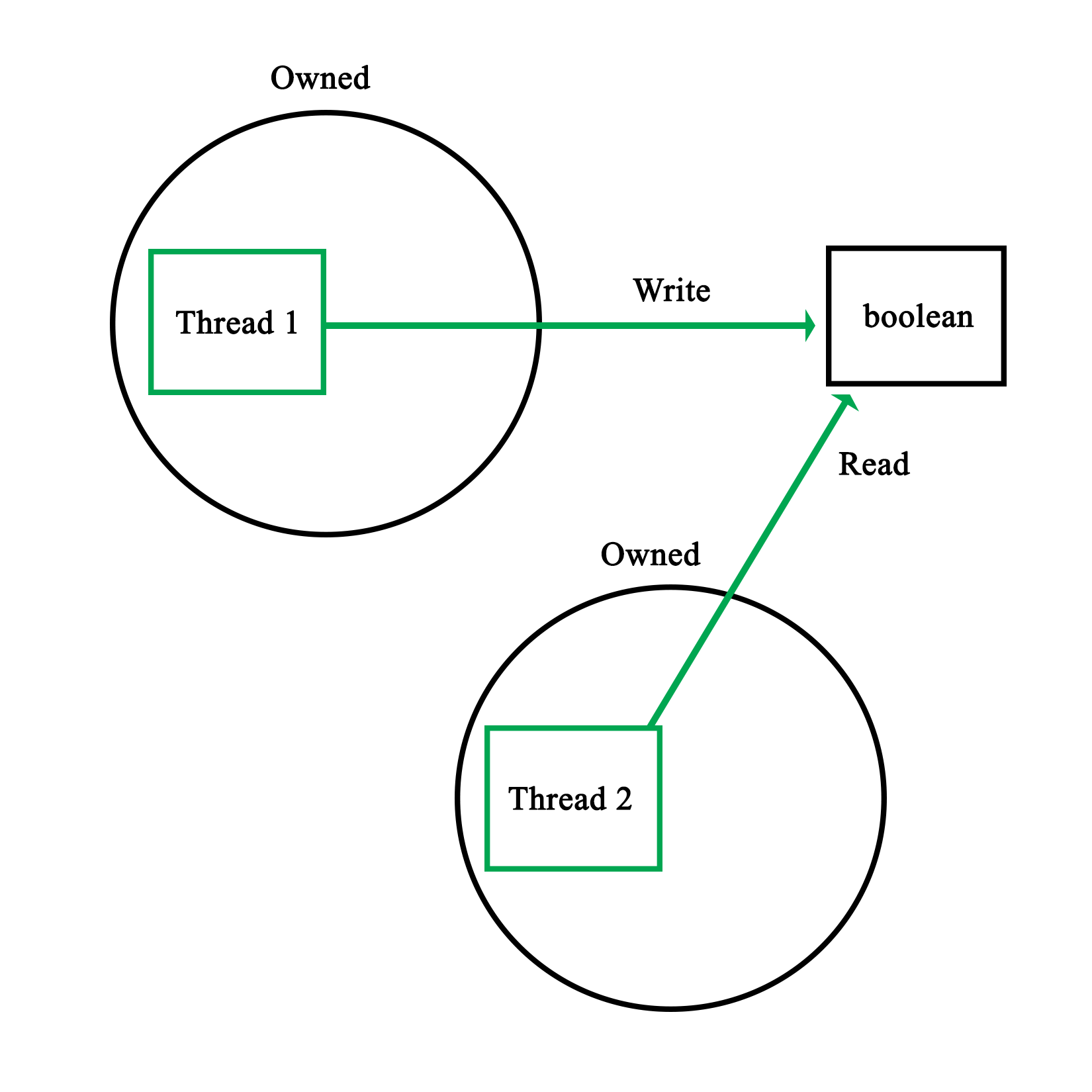

A mutex, in essence, is a singular value being stored on the stack of heap, which then is accessed using an atomic operation. This means that some form of hardware support is required. Using this, a task can check whether it is allowed to proceed yet, or has to wait and try again.

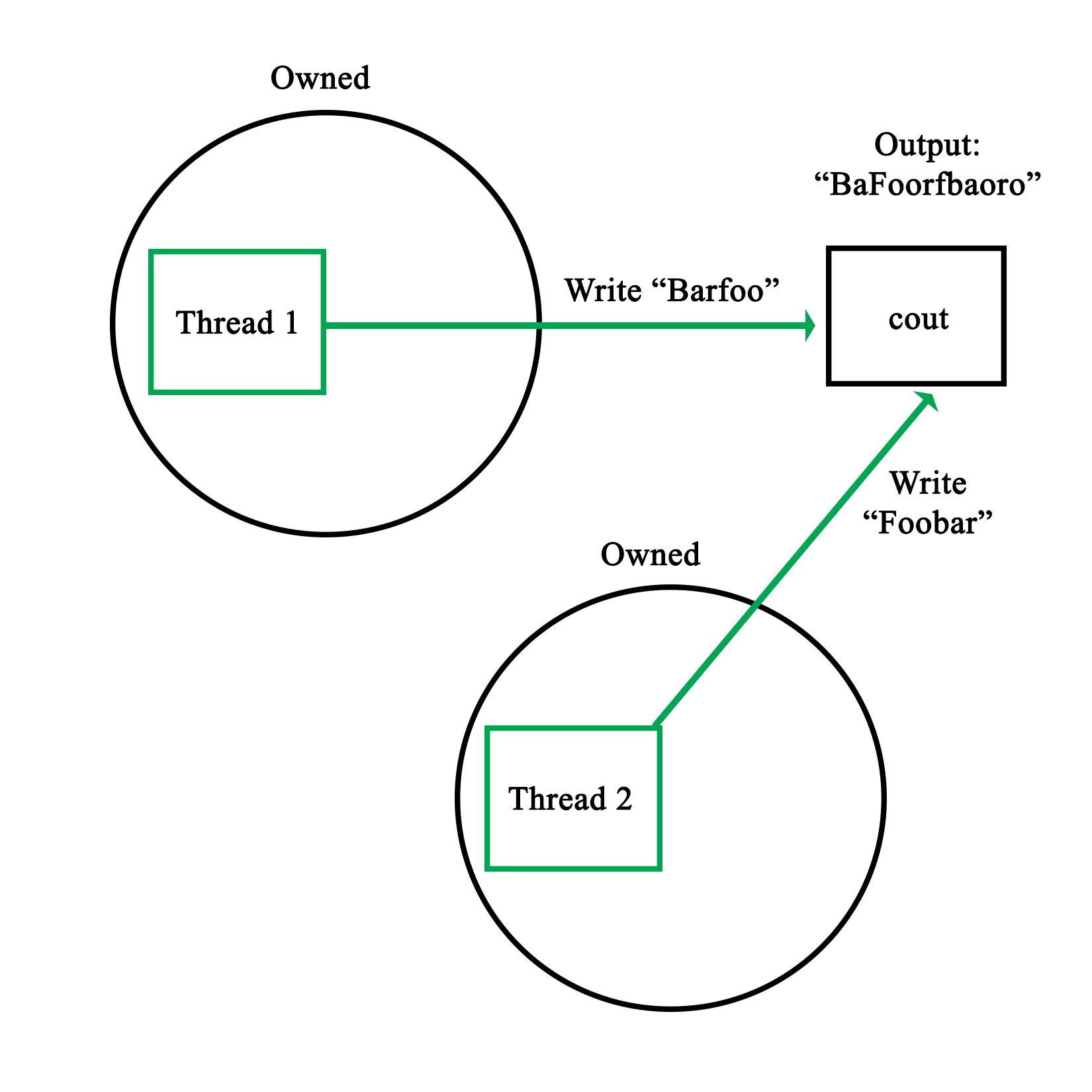

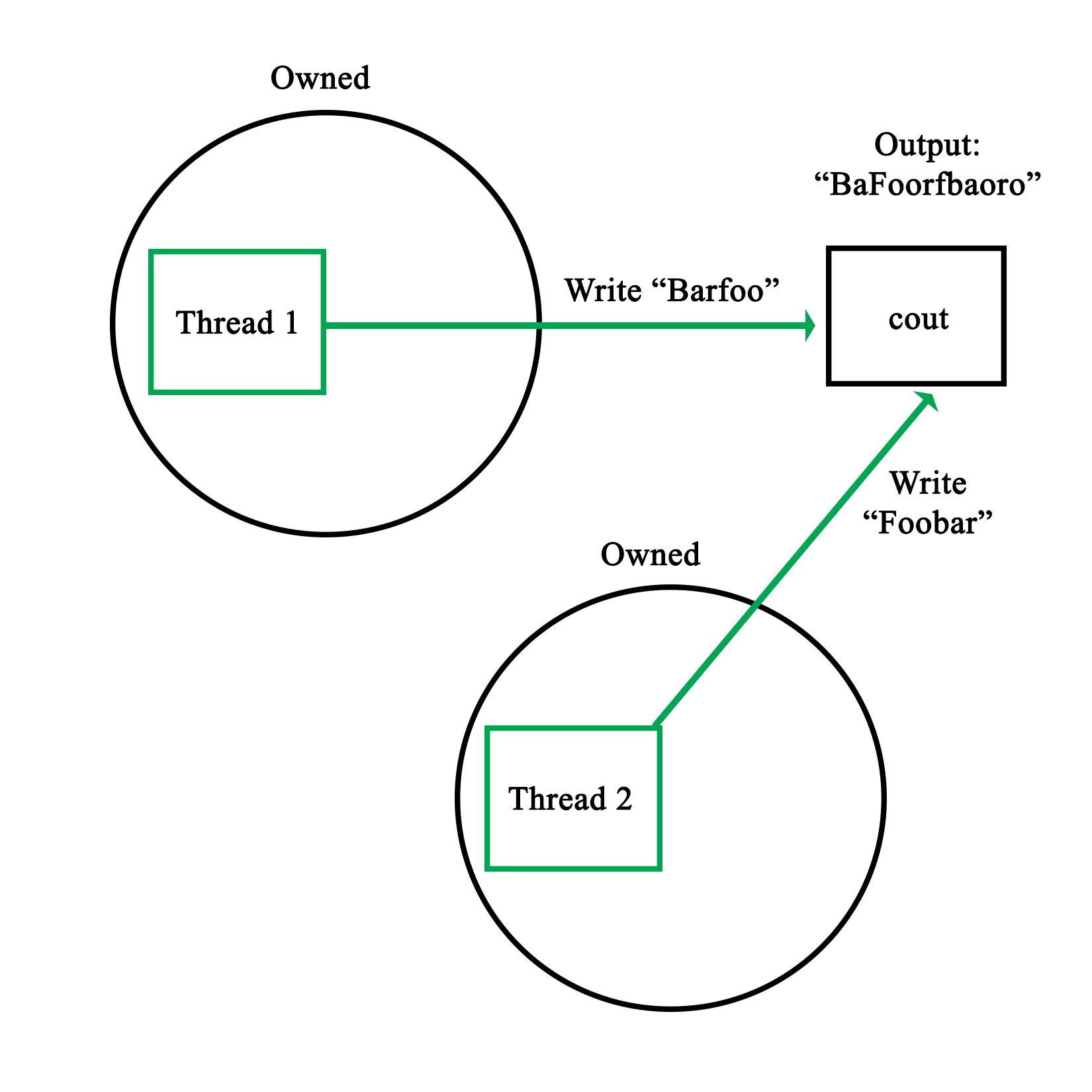

In this last particular piece of code, this mutex lock allows us to output on the standard C++ output stream without other threads interfering.

After this, we copy the initial value in the vector to a local variable, again ensuring that it's done synchronously:

values_mtx.lock();

int val = values[0];

values_mtx.unlock();

The same thing happens here, except now the mutex lock allows us to read the first value in the vector without risking another thread accessing or even changing it while we use it.

This is followed by the generating of a random number as follows:

int rval = randGen(0, 10);

val += rval;

This uses the randGen() method, which is as follows:

int randGen(const int& min, const int& max) {

static thread_local mt19937 generator(hash<thread::id>() (this_thread::get_id()));

uniform_int_distribution<int> distribution(min, max);

return distribution(generator);

}

This method is interesting due to its use of a thread-local variable. Thread-local storage is a section of a thread's memory which is specific to it, and used for global variables, which, nevertheless, have to remain limited to that specific thread.

This is very useful for a static variable like the one used here. That the generator instance is static is because we do not want to reinitialize it every single time we use this method, yet we do not want to share this instance across all threads. By using a thread-local, static instance, we can accomplish both goals. A static instance is created and used, but separately for each thread.

The Thread function then ends with the same series of mutexes being locked, and the new value being copied to the array.

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Thread " << tid << " adding " << rval << ". New value: " << val << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

values_mtx.lock();

values.push_back(val);

values_mtx.unlock();

}

Here we see the same synchronous access to the standard output stream, followed by synchronous access to the values data structure.

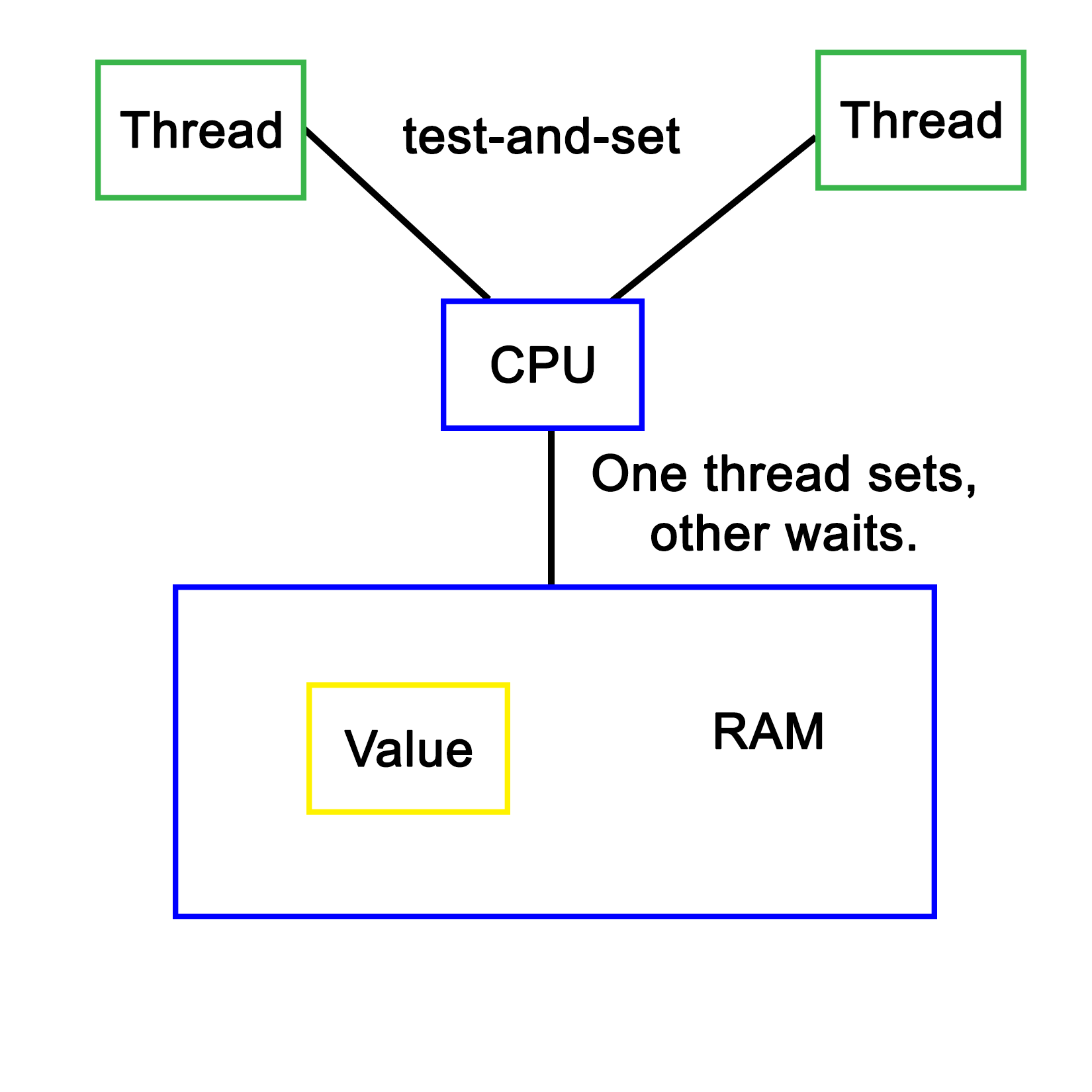

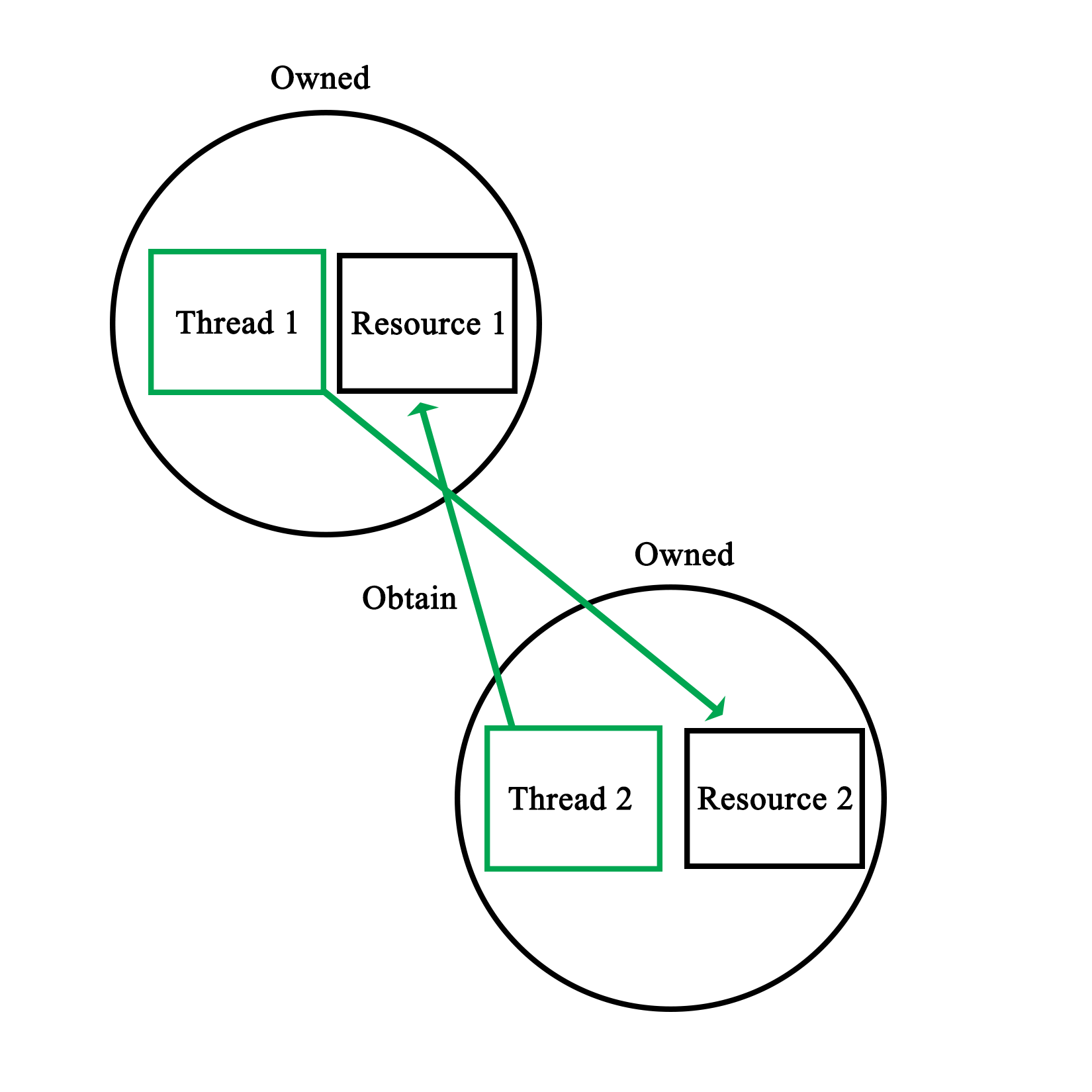

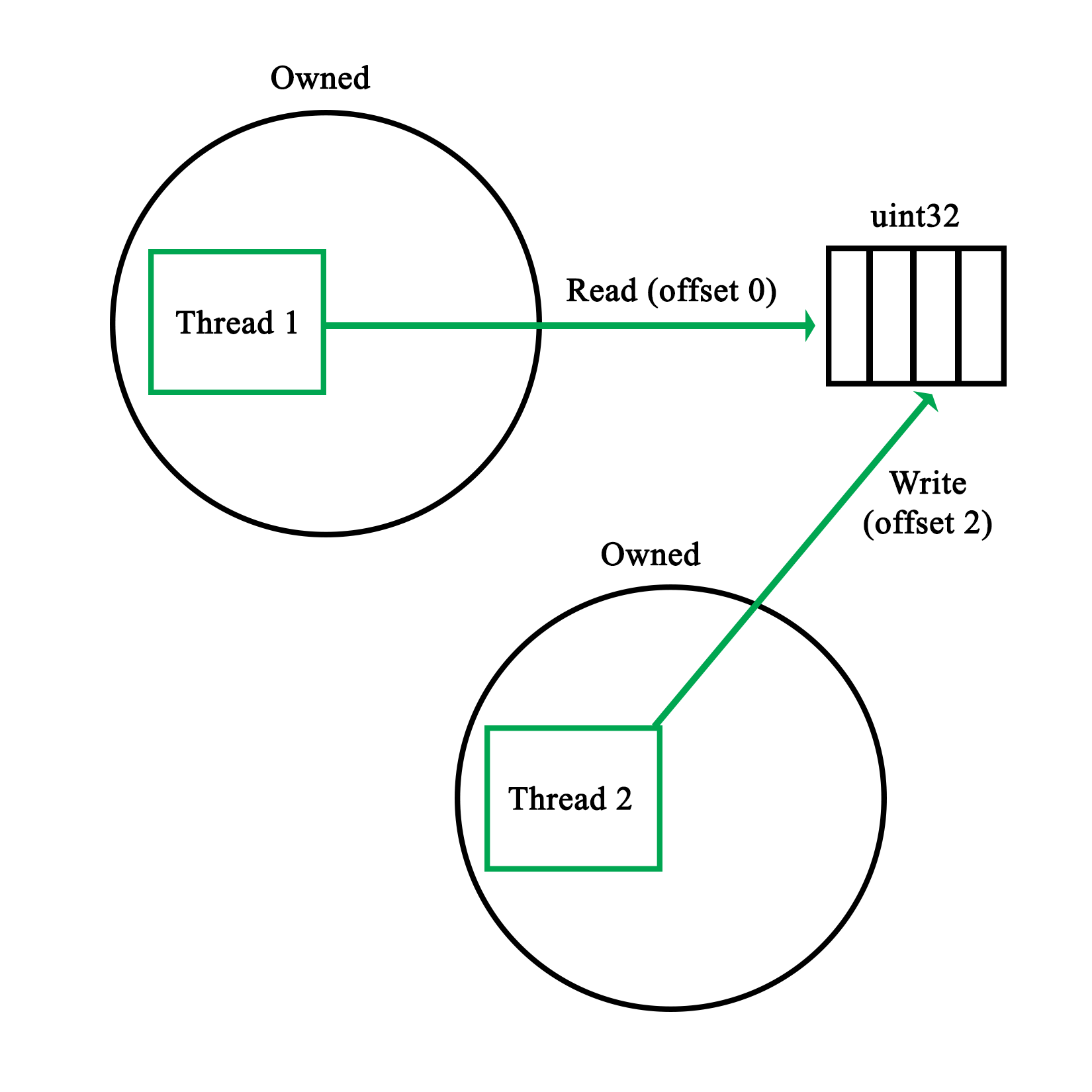

Mutual exclusion is the principle which underlies thread-safe access of data within a multithreaded application. One can implement this both in hardware and software. The mutual exclusion (mutex) is the most elementary form of this functionality in most implementations.

The simplest hardware-based implementation on a uniprocessor (single processor core), non-SMT system is to disable interrupts, and thus, prevent the task from being changed. More commonly, a so-called busy-wait principle is employed. This is the basic principle behind a mutex--due to how the processor fetches data, only one task can obtain and read/write an atomic value in the shared memory, meaning, a variable sized the same (or smaller) as the CPU's registers. This is further detailed in Chapter 8, Atomic Operations - Working with the Hardware.

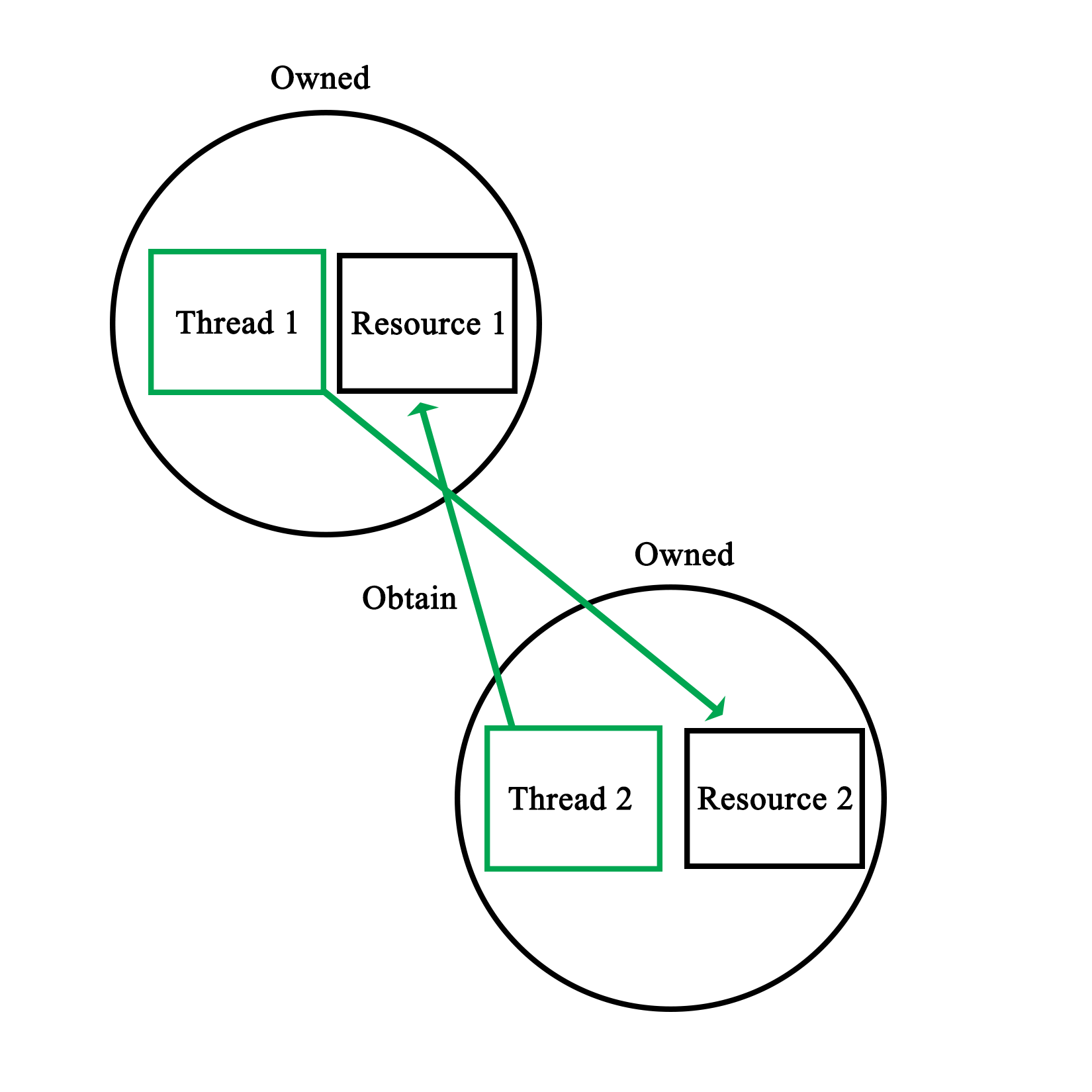

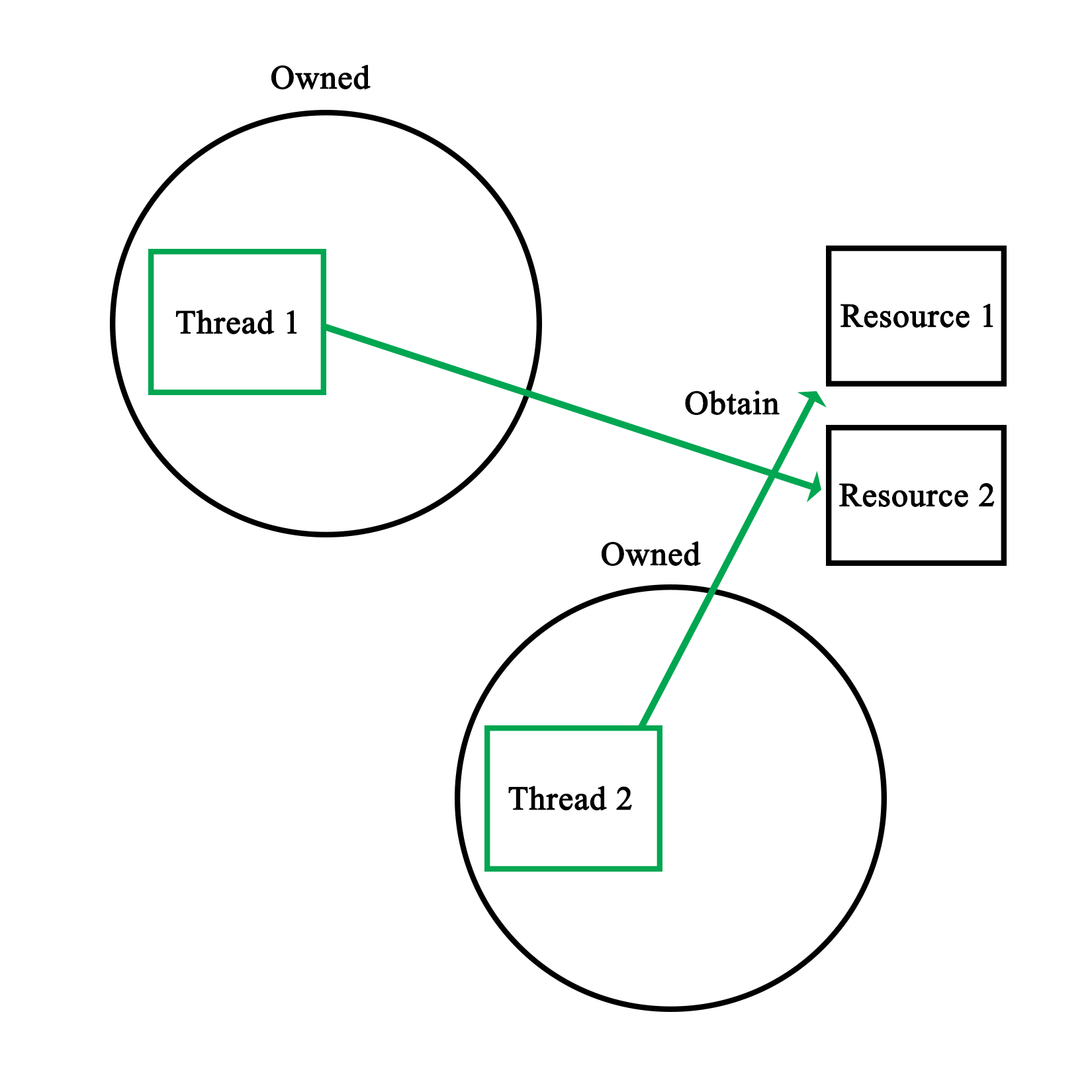

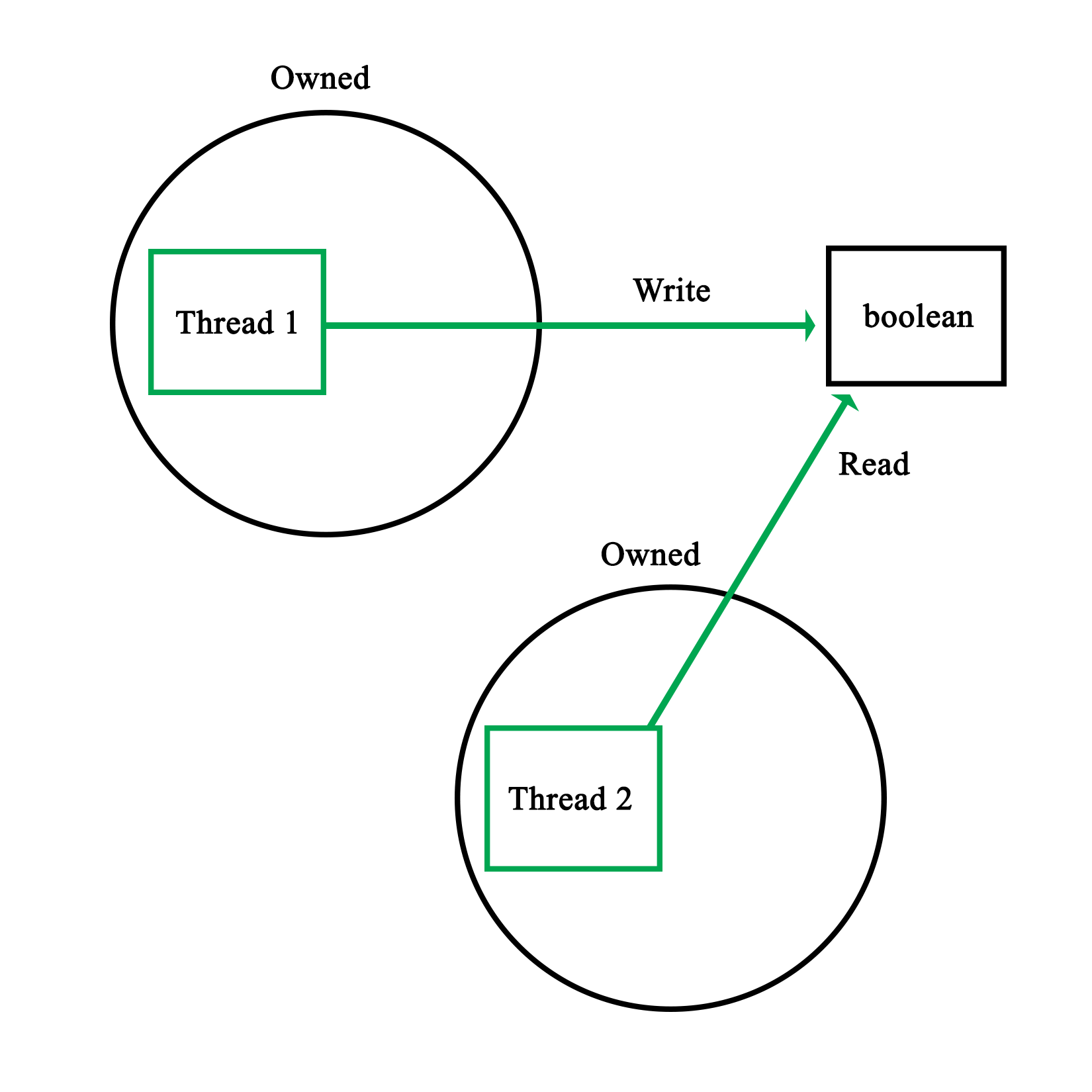

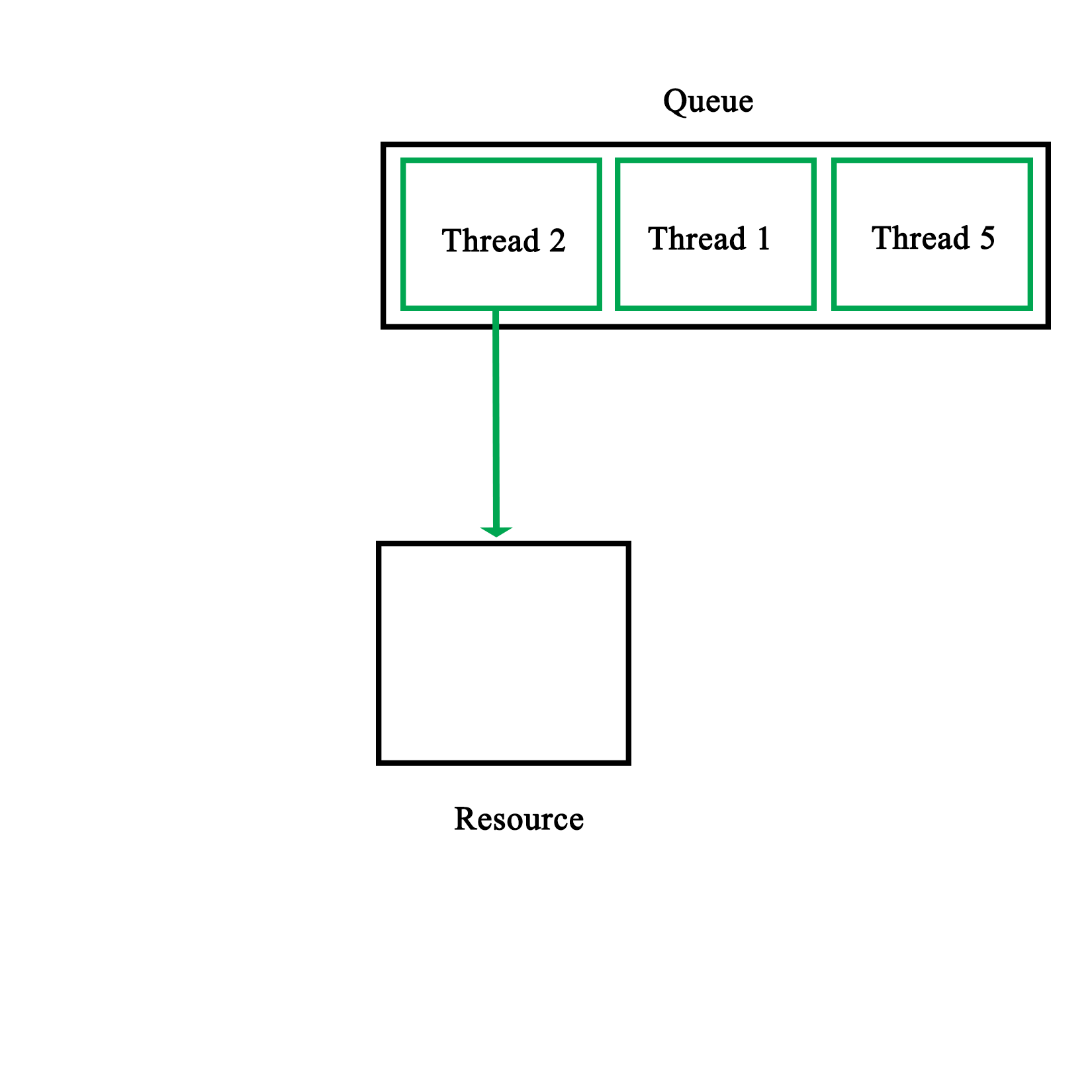

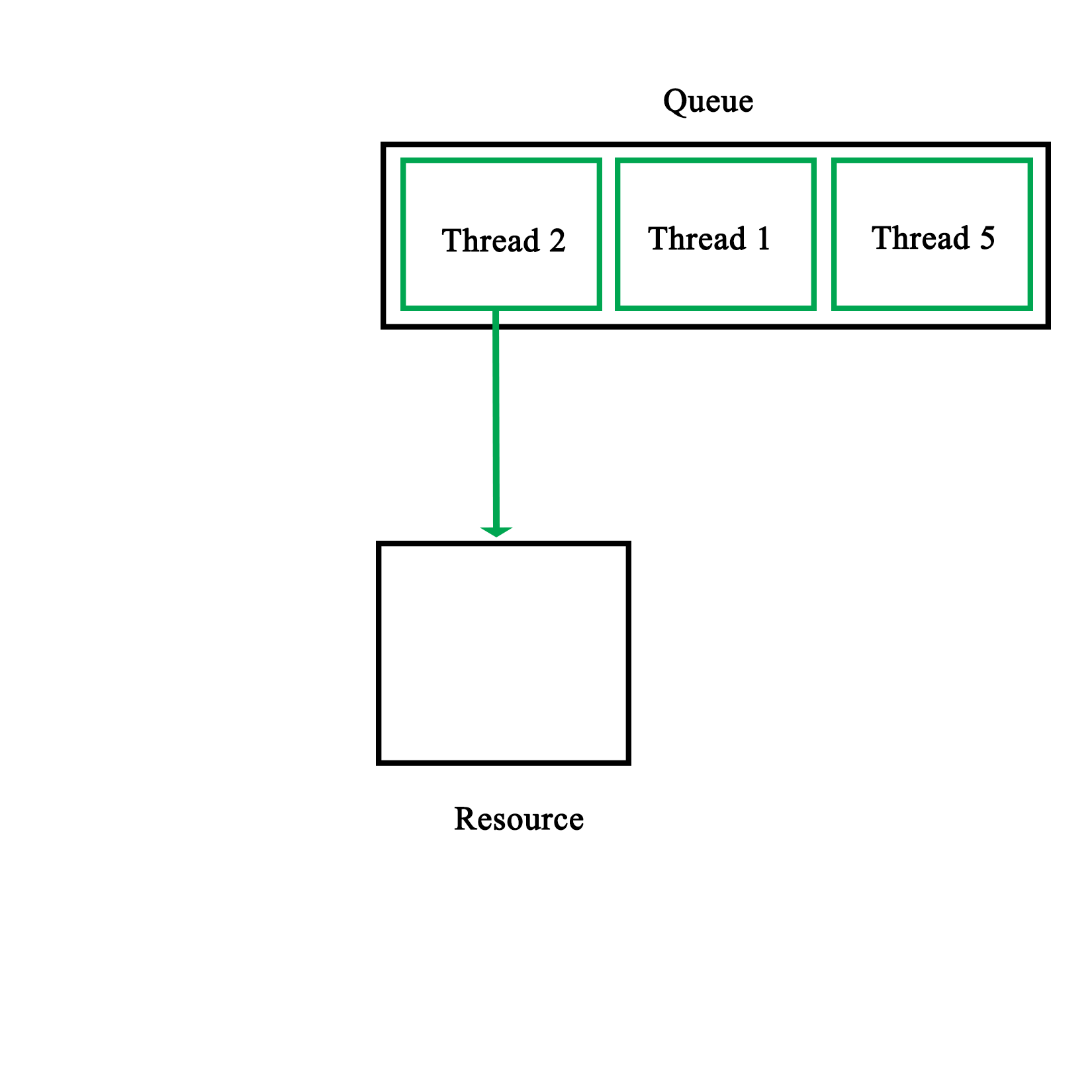

When our code tries to lock a mutex, what this does is read the value of such an atomic section of memory, and try to set it to its locked value. Since this is a single operation, only one task can change the value at any given time. Other tasks will have to wait until they can gain access in this busy-wait cycle, as shown in this diagram:

Software-defined mutual exclusion implementations are all based on busy-waiting. An example is Dekker's algorithm, which defines a system in which two processes can synchronize, employing busy-wait to wait for the other process to leave the critical section.

The pseudocode for this algorithm is as follows:

variables

wants_to_enter : array of 2 booleans

turn : integer

wants_to_enter[0] ← false

wants_to_enter[1] ← false

turn ← 0 // or 1

p0:

wants_to_enter[0] ← true

while wants_to_enter[1] {

if turn ≠ 0 {

wants_to_enter[0] ← false

while turn ≠ 0 {

// busy wait

}

wants_to_enter[0] ← true

}

}

// critical section

...

turn ← 1

wants_to_enter[0] ← false

// remainder section

p1:

wants_to_enter[1] ← true

while wants_to_enter[0] {

if turn ≠ 1 {

wants_to_enter[1] ← false

while turn ≠ 1 {

// busy wait

}

wants_to_enter[1] ← true

}

}

// critical section

...

turn ← 0

wants_to_enter[1] ← false

// remainder section

(Referenced from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dekker's_algorithm)

In this preceding algorithm, processes indicate the intent to enter a critical section, checking whether it's their turn (using the process ID), then setting their intent to enter the section to false after they have entered it. Only once a process has set its intent to enter to true again will it enter the critical section again. If it wishes to enter, but turn does not match its process ID, it'll busy-wait until the condition becomes true.

A major disadvantage of software-based mutual exclusion algorithms is that they only work if out-of-order (OoO) execution of code is disabled. OoO means that the hardware actively reorders incoming instructions in order to optimize their execution, thus changing their order. Since these algorithms require that various steps are executed in order, they no longer work on OoO processors.

In this chapter, we saw how processes and threads are implemented both in operating systems and in hardware. We also looked at various configurations of processor hardware and elements of operating systems involved in scheduling to see how they provide various types of task processing.

Finally, we took the multithreaded program example of the previous chapter, and ran through it again, this time considering what happens in the OS and processor while it is being executed.

In the next chapter, we will take a look at the various multithreading APIs being offered via OS and library-based implementations, along with examples comparing these APIs.

While C++ has a native multithreading implementation in the Standard Template Library (STL), OS-level and framework-based multithreading APIs are still very common. Examples of these APIs include Windows and POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface) threads, and those provided by the Qt, Boost, and POCO libraries.

This chapter takes a detailed look at the features provided by each of these APIs, as well as the similarities and differences between each of them. Finally, we'll look at common usage scenarios using example code.

Topics covered by this chapter include the following:

Before the C++ 2011 (C++11) standard, many different threading implementations were developed, many of which are limited to a specific software platform. Some of these are still relevant today, such as Windows threads. Others have been superseded by standards, of which POSIX Threads (Pthreads) has become the de facto standard on UNIX-like OSes. This includes Linux-based and BSD-based OS, as well as OS X (macOS) and Solaris.

Many libraries were developed to make cross-platform development easier. Although Pthreads helps to make UNIX-like OS more or less compatible one of the prerequisites to make software portable across all major operating systems, a generic threading API is needed. This is why libraries such as Boost, POCO, and Qt were created. Applications can use these and rely on the library to handle any differences between platforms.

Pthreads were first defined in the POSIX.1c standard (Threads extensions, IEEE Std 1003.1c-1995) from 1995 as an extension to the POSIX standard. At the time, UNIX had been chosen as a manufacturer-neutral interface, with POSIX unifying the various APIs among them.

Despite this standardization effort, differences still exist in Pthread implementations between OS's which implement it (for example, between Linux and OS X), courtesy of non-portable extensions (marked with _np in the method name).

For the pthread_setname_np method, the Linux implementation takes two parameters, allowing one to set the name of a thread other than the current thread. On OS X (since 10.6), this method only takes one parameter, allowing one to set the name of the current thread only. If portability is a concern, one has to be mindful of such differences.

After 1997, the POSIX standard revisions were managed by the Austin Joint Working Group. These revisions merge the threads extension into the main standard. The current revision is 7, also known as POSIX.1-2008 and IEEE Std 1003.1, 2013 edition--with a free copy of the standard available online.

OS's can be certified to conform to the POSIX standard. Currently, these are as mentioned in this table:

| Name | Developer | Since version | Architecture(s) (current) | Notes |

|

AIX |

IBM |

5L |

POWER |

Server OS |

|

HP-UX |

Hewlett-Packard |

11i v3 |

PA-RISC, IA-64 (Itanium) |

Server OS |

|

IRIX |

Silicon Graphics (SGI) |

6 |

MIPS |

Discontinued |

|

Inspur K-UX |

Inspur |

2 |

X86_64, |

Linux based |

|

Integrity |

Green Hills Software |

5 |

ARM, XScale, Blackfin, Freescale Coldfire, MIPS, PowerPC, x86. |

Real-time OS |

|

OS X/MacOS |

Apple |

10.5 (Leopard) |

X86_64 |

Desktop OS |

|

QNX Neutrino |

BlackBerry |

1 |

Intel 8088, x86, MIPS, PowerPC, SH-4, ARM, StrongARM, XScale |

Real-time, embedded OS |

|

Solaris |

Sun/Oracle |

2.5 |

SPARC, IA-32 (<11), x86_64, PowerPC (2.5.1) |

Server OS |

|

Tru64 |

DEC, HP, IBM, Compaq |

5.1B-4 |

Alpha |

Discontinued |

|

UnixWare |

Novell, SCO, Xinuos |

7.1.3 |

x86 |

Server OS |

Other operating systems are mostly compliant. The following are examples of the same:

| Name | Platform | Notes |

|

Android |

ARM, x86, MIPS |

Linux based. Bionic C-library. |

|

BeOS (Haiku) |

IA-32, ARM, x64_64 |

Limited to GCC 2.x for x86. |

|

Darwin |

PowerPC, x86, ARM |

Uses the open source components on which macOS is based. |

|

FreeBSD |

IA-32, x86_64, sparc64, PowerPC, ARM, MIPS, and so on |

Essentially POSIX compliant. One can rely on documented POSIX behavior. More strict on compliance than Linux, in general. |

|

Linux |

Alpha, ARC, ARM, AVR32, Blackfin, H8/300, Itanium, m68k, Microblaze, MIPS, Nios II, OpenRISC, PA-RISC, PowerPC, s390, S+core, SuperH, SPARC, x86, Xtensa, and so on |

Some Linux distributions (see previous table) are certified as being POSIX compliant. This does not imply that every Linux distribution is POSIX compliant. Some tools and libraries may differ from the standard. For Pthreads, this may mean that the behavior is sometimes different between Linux distributions (different scheduler, and so on) as well as compared to other OS's implementing Pthreads. |

|

MINIX 3 |

IA-32, ARM |

Conforms to POSIX specification standard 3 (SUSv3, 2004). |

|

NetBSD |

Alpha, ARM, PA-RISC, 68k, MIPS, PowerPC, SH3, SPARC, RISC-V, VAX, x86, and so on |

Almost fully compatible with POSX.1 (1990), and mostly compliant with POSIX.2 (1992). |

|

Nuclear RTOS |

ARM, MIPS, PowerPC, Nios II, MicroBlaze, SuperH, and so on |

Proprietary RTOS from Mentor Graphics aimed at embedded applications. |

|

NuttX |

ARM, AVR, AVR32, HCS12, SuperH, Z80, and so on |

Light-weight RTOS, scalable from 8 to 32-bit systems with strong focus on POSIX compliance. |

|

OpenBSD |

Alpha, x86_64, ARM, PA-RISC, IA-32, MIPS, PowerPC, SPARC, and so on |

Forked from NetBSD in 1995. Similar POSIX support. |

|

OpenSolaris/illumos |

IA-32, x86_64, SPARC, ARM |

Compliant with the commercial Solaris releases being certified compatible. |

|

VxWorks |

ARM, SH-4, x86, x86_64, MIPS, PowerPC |

POSIX compliant, with certification for user-mode execution environment. |

From this it should be obvious that it's not a clear matter of following the POSIX specification, and being able to count on one's code compiling on each of these platforms. Each platform will also have its own set of extensions to the standard for features which were omitted in the standard, but are still desirable. Pthreads are, however, widely used by Linux, BSD, and similar software.

It's also possible to use the POSIX APIs in a limited fashion using, for example, the following:

| Name | Compliance |

|

Cygwin |

Mostly complete. Provides a full runtime environment for a POSIX application, which can be distributed as a normal Windows application. |

|

MinGW |

With MinGW-w64 (a redevelopment of MinGW), Pthreads support is fairly complete, though some functionality may be absent. |

|

Windows Subsystem for Linux |

WSL is a Windows 10 feature, which allows a Ubuntu Linux 14.04 (64-bit) image's tools and utilities to run natively on top of it though not those using GUI features or missing kernel features. Otherwise, it offers similar compliance as Linux. This feature currently requires that one runs the Windows 10 Anniversary Update and install WSL by hand using instructions provided by Microsoft. |

POSIX on Windows is generally not recommended. Unless there are good reasons to use POSIX (large existing code base, for example), it's far easier to use one of the cross-platform APIs (covered later in this chapter), which smooth away any platform issues.

In the following sections, we'll look at the features offered by the Pthreads API.

These are all the functions which start with either pthread_ or pthread_attr_. These functions all apply to threads themselves and their attribute objects.

The basic use of threads with Pthreads looks like the following:

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 5

The main Pthreads header is pthread.h. This gives access to everything but semaphores (covered later in this section). We also define a constant for the number of threads we wish to start here:

void* worker(void* arg) {

int value = *((int*) arg);

// More business logic.

return 0;

}

We define a simple Worker function, which we'll pass to the new thread in a moment. For demonstration and debugging purposes one could first add a simple cout or printf-based bit of business logic to print out the value sent to the new thread.

Next, we define the main function as follows:

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

pthread_t threads[NUM_THREADS];

int thread_args[NUM_THREADS];

int result_code;

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; ++i) {

thread_args[i] = i;

result_code = pthread_create(&threads[i], 0, worker, (void*) &thread_args[i]);

}

We create all of the threads in a loop in the preceding function. Each thread instance gets a thread ID assigned (first argument) when created in addition to a result code (zero on success) returned by the pthread_create() function. The thread ID is the handle to reference the thread in future calls.

The second argument to the function is a pthread_attr_t structure instance, or 0 if none. This allows for configuration characteristics of the new thread, such as the initial stack size. When zero is passed, default parameters are used, which differ per platform and configuration.

The third parameter is a pointer to the function which the new thread will start with. This function pointer is defined as a function which returns a pointer to void data (that is, custom data), and accepts a pointer to void data. Here, the data being passed to the new thread as an argument is the thread ID:

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; ++i) {

result_code = pthread_join(threads[i], 0);

}

exit(0);

}

Next, we wait for each worker thread to finish using the pthread_join() function. This function takes two parameters, the ID of the thread to wait for, and a buffer for the return value of the Worker function (or zero).

Other functions to manage threads are as follows:

Beyond this, there are the pthread_attr_* functions to manipulate and obtain information about a pthread_attr_t structure.

These are functions prefixed with either pthread_mutex_ or pthread_mutexattr_. They apply to mutexes and their attribute objects.

Mutexes in Pthreads can be initialized, destroyed, locked, and unlocked. They can also have their behavior customized using a pthread_mutexattr_t structure, which has its corresponding pthread_mutexattr_* functions for initializing and destroying an attribute on it.

A basic use of a Pthread mutex using static initialization looks as follows:

static pthread_mutex_t func_mutex = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

void func() {

pthread_mutex_lock(&func_mutex);

// Do something that's not thread-safe.

pthread_mutex_unlock(&func_mutex);

}

In this last bit of code, we use the PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER macro, which initializes the mutex for us without having to type out the code for it every time. In comparison to other APIs, one has to manually initialize and destroy mutexes, though the use of macros helps somewhat.

After this, we lock and unlock the mutex. There's also the pthread_mutex_trylock() function, which is like the regular lock version, but which will return immediately if the referenced mutex is already locked instead of waiting for it to be unlocked.

In this example, the mutex is not explicitly destroyed. This is, however, a part of normal memory management in a Pthreads-based application.

These are functions which are prefixed with either pthread_cond_ or pthread_condattr_. They apply to condition variables and their attribute objects.

Condition variables in Pthreads follow the same pattern of having an initialization and a destroy function in addition to having the same for managing a pthread_condattr_t attribution structure.

This example covers basic usage of Pthreads condition variables:

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define COUNT_TRIGGER 10

#define COUNT_LIMIT 12

int count = 0;

int thread_ids[3] = {0,1,2};

pthread_mutex_t count_mutex;

pthread_cond_t count_cv;

In the preceding code, we get the standard headers, and define a count trigger and limit, whose purpose will become clear in a moment. We also define a few global variables: a count variable, the IDs for the threads we wish to create, as well as a mutex and condition variable:

void* add_count(void* t) {

int tid = (long) t;

for (int i = 0; i < COUNT_TRIGGER; ++i) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&count_mutex);

count++;

if (count == COUNT_LIMIT) {

pthread_cond_signal(&count_cv);

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&count_mutex);

sleep(1);

}

pthread_exit(0);

}

This preceding function, essentially, just adds to the global counter variable after obtaining exclusive access to it with the count_mutex. It also checks whether the count trigger value has been reached. If it has, it will signal the condition variable.

To give the second thread, which also runs this function, a chance to get the mutex, we sleep for 1 second in each cycle of the loop:

void* watch_count(void* t) {

int tid = (int) t;

pthread_mutex_lock(&count_mutex);

if (count < COUNT_LIMIT) {

pthread_cond_wait(&count_cv, &count_mutex);

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&count_mutex);

pthread_exit(0);

}

In this second function, we lock the global mutex before checking whether we have reached the count limit yet. This is our insurance in case the thread running this function does not get called before the count reaches the limit.

Otherwise, we wait on the condition variable providing the condition variable and locked mutex. Once signaled, we unlock the global mutex, and exit the thread.

A point to note here is that this example does not account for spurious wake-ups. Pthreads condition variables are susceptible to such wake-ups which necessitate one to use a loop and check whether some kind of condition has been met:

int main (int argc, char* argv[]) {

int tid1 = 1, tid2 = 2, tid3 = 3;

pthread_t threads[3];

pthread_attr_t attr;

pthread_mutex_init(&count_mutex, 0);

pthread_cond_init (&count_cv, 0);

pthread_attr_init(&attr);

pthread_attr_setdetachstate(&attr, PTHREAD_CREATE_JOINABLE);

pthread_create(&threads[0], &attr, watch_count, (void *) tid1);

pthread_create(&threads[1], &attr, add_count, (void *) tid2);

pthread_create(&threads[2], &attr, add_count, (void *) tid3);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

pthread_join(threads[i], 0);

}

pthread_attr_destroy(&attr);

pthread_mutex_destroy(&count_mutex);

pthread_cond_destroy(&count_cv);

return 0;

}

Finally, in the main function, we create the three threads, with two running the function which adds to the counter, and the third running the function which waits to have its condition variable signaled.

In this method, we also initialize the global mutex and condition variable. The threads we create further have the "joinable" attribute explicitly set.

Finally, we wait for each thread to finish, after which we clean up, destroying the attribute structure instance, mutex, and condition variable before exiting.

Using the pthread_cond_broadcast() function, it's further possible to signal all threads which are waiting for a condition variable instead of merely the first one in the queue. This enables one to use condition variables more elegantly with some applications, such as where one has a lot of worker threads waiting for new dataset to arrive without having to notify every thread individually.

Functions which implement synchronization are prefixed with pthread_rwlock_ or pthread_barrier_. These implement read/write locks and synchronization barriers.

A read/write lock (rwlock) is very similar to a mutex, except that it has the additional feature of allowing infinite threads to read simultaneously, while only restricting write access to a singular thread.

Using rwlock is very similar to using a mutex:

#include <pthread.h>

int pthread_rwlock_init(pthread_rwlock_t* rwlock, const pthread_rwlockattr_t* attr);

pthread_rwlock_t rwlock = PTHREAD_RWLOCK_INITIALIZER;

In the last code, we include the same general header, and either use the initialization function, or the generic macro. The interesting part is when we lock rwlock, which can be done for just read-only access:

int pthread_rwlock_rdlock(pthread_rwlock_t* rwlock);

int pthread_rwlock_tryrdlock(pthread_rwlock_t* rwlock);

Here, the second variation returns immediately if the lock has been locked already. One can also lock it for write access as follows:

int pthread_rwlock_wrlock(pthread_rwlock_t* rwlock);

int pthread_rwlock_trywrlock(pthread_rwlock_t * rwlock);

These functions work basically the same, except that only one writer is allowed at any given time, whereas multiple readers can obtain a read-only lock.

Barriers are another concept with Pthreads. These are synchronization objects which act like a barrier for a number of threads. All of these have to reach the barrier before any of them can proceed past it. In the barrier initialization function, the thread count is specified. Only once all of these threads have called the barrier object using the pthread_barrier_wait() function will they continue executing.

Semaphores were, as mentioned earlier, not part of the original Pthreads extension to the POSIX specification. They are declared in the semaphore.h header for this reason.

In essence, semaphores are simple integers, generally used as a resource count. To make them thread-safe, atomic operations (check and lock) are used. POSIX semaphores support the initializing, destroying, incrementing and decrementing of a semaphore as well as waiting for the semaphore to reach a non-zero value.

With Pthreads, TLS is accomplished using keys and methods to set thread-specific data:

pthread_key_t global_var_key;

void* worker(void* arg) {

int *p = new int;

*p = 1;

pthread_setspecific(global_var_key, p);

int* global_spec_var = (int*) pthread_getspecific(global_var_key);

*global_spec_var += 1;

pthread_setspecific(global_var_key, 0);

delete p;

pthread_exit(0);

}

In the worker thread, we allocate a new integer on the heap, and set the global key to its own value. After increasing the global variable by 1, its value will be 2, regardless of what the other threads do. We can set the global variable to 0 once we're done with it for this thread, and delete the allocated value:

int main(void) {

pthread_t threads[5];

pthread_key_create(&global_var_key, 0);

for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i)

pthread_create(&threads[i],0,worker,0);

for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) {

pthread_join(threads[i], 0);

}

return 0;

}

A global key is set and used to reference the TLS variable, yet each of the threads we create can set its own value for this key.

While a thread can create its own keys, this method of handling TLS is fairly involved compared to the other APIs we're looking at in this chapter.

Relative to Pthreads, Windows threads are limited to Windows operating systems and similar (for example ReactOS, and other OS's using Wine). This provides a fairly consistent implementation, easily defined by the Windows version that the support corresponds to.

Prior to Windows Vista, threading support missed features such as condition variables, while having features not found in Pthreads. Depending on one's perspective, having to use the countless "type def" types defined by the Windows headers can be a bother as well.

A basic example of using Windows threads, as adapted from the official MSDN documentation sample code, looks like this:

#include <windows.h>

#include <tchar.h>

#include <strsafe.h>

#define MAX_THREADS 3

#define BUF_SIZE 255

After including a series of Windows-specific headers for the thread functions, character strings, and more, we define the number of threads we wish to create as well as the size of the message buffer in the Worker function.

We also define a struct type (passed by void pointer: LPVOID) to contain the sample data we pass to each worker thread:

typedef struct MyData {

int val1;

int val2;

} MYDATA, *PMYDATA;

DWORD WINAPI worker(LPVOID lpParam) {

HANDLE hStdout = GetStdHandle(STD_OUTPUT_HANDLE);

if (hStdout == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

return 1;

}

PMYDATA pDataArray = (PMYDATA) lpParam;

TCHAR msgBuf[BUF_SIZE];

size_t cchStringSize;

DWORD dwChars;

StringCchPrintf(msgBuf, BUF_SIZE, TEXT("Parameters = %d, %dn"),

pDataArray->val1, pDataArray->val2);

StringCchLength(msgBuf, BUF_SIZE, &cchStringSize);

WriteConsole(hStdout, msgBuf, (DWORD) cchStringSize, &dwChars, NULL);

return 0;

}

In the Worker function, we cast the provided parameter to our custom struct type before using it to print its values to a string, which we output on the console.

We also validate that there's an active standard output (console or similar). The functions used to print the string are all thread safe.

void errorHandler(LPTSTR lpszFunction) {

LPVOID lpMsgBuf;

LPVOID lpDisplayBuf;

DWORD dw = GetLastError();

FormatMessage(

FORMAT_MESSAGE_ALLOCATE_BUFFER |

FORMAT_MESSAGE_FROM_SYSTEM |

FORMAT_MESSAGE_IGNORE_INSERTS,

NULL,

dw,

MAKELANGID(LANG_NEUTRAL, SUBLANG_DEFAULT),

(LPTSTR) &lpMsgBuf,

0, NULL);

lpDisplayBuf = (LPVOID) LocalAlloc(LMEM_ZEROINIT,

(lstrlen((LPCTSTR) lpMsgBuf) + lstrlen((LPCTSTR) lpszFunction) + 40) * sizeof(TCHAR));

StringCchPrintf((LPTSTR)lpDisplayBuf,

LocalSize(lpDisplayBuf) / sizeof(TCHAR),

TEXT("%s failed with error %d: %s"),

lpszFunction, dw, lpMsgBuf);

MessageBox(NULL, (LPCTSTR) lpDisplayBuf, TEXT("Error"), MB_OK);

LocalFree(lpMsgBuf);

LocalFree(lpDisplayBuf);

}