In its most basic form, a multithreaded application consists of a singular process with two or more threads. These threads can be used in a variety of ways; for example, to allow the process to respond to events in an asynchronous manner by using one thread per incoming event or type of event, or to speed up the processing of data by splitting the work across multiple threads.

Examples of asynchronous responses to events include the processing of the graphical user interface (GUI) and network events on separate threads so that neither type of event has to wait on the other, or can block events from being responded to in time. Generally, a single thread performs a single task, such as the processing of GUI or network events, or the processing of data.

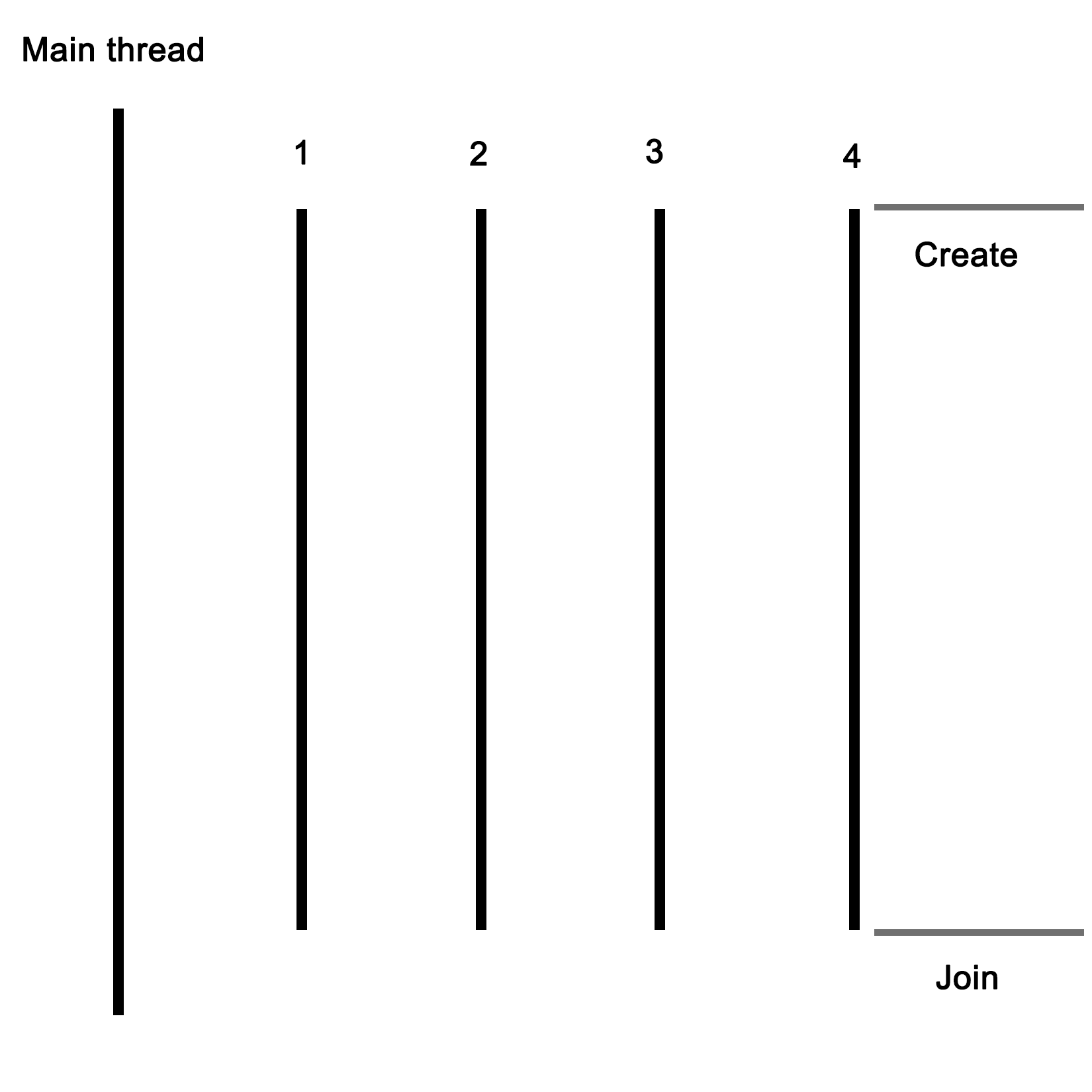

For this basic example, the application will start with a singular thread, which will then launch a number of threads, and wait for them to finish. Each of these new threads will perform its own task before finishing.

Let's start with the includes and global variables for our application:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

using namespace std;

// --- Globals

mutex values_mtx;

mutex cout_mtx;

vector<int> values;

Both the I/O stream and vector headers should be familiar to anyone who has ever used C++: the former is here used for the standard output (cout), and the vector for storing a sequence of values.

The random header is new in c++11, and as the name suggests, it offers classes and methods for generating random sequences. We use it here to make our threads do something interesting.

Finally, the thread and mutex includes are the core of our multithreaded application; they provide the basic means for creating threads, and allow for thread-safe interactions between them.

Moving on, we create two mutexes: one for the global vector and one for cout, since the latter is not thread-safe.

Next we create the main function as follows:

int main() {

values.push_back(42);

We push a fixed value onto the vector instance; this one will be used by the threads we create in a moment:

thread tr1(threadFnc, 1);

thread tr2(threadFnc, 2);

thread tr3(threadFnc, 3);

thread tr4(threadFnc, 4);

We create new threads, and provide them with the name of the method to use, passing along any parameters--in this case, just a single integer:

tr1.join();

tr2.join();

tr3.join();

tr4.join();

Next, we wait for each thread to finish before we continue by calling join() on each thread instance:

cout << "Input: " << values[0] << ", Result 1: " << values[1] << ", Result 2: " << values[2] << ", Result 3: " << values[3] << ", Result 4: " << values[4] << "\n";

return 1;

}

At this point, we expect that each thread has done whatever it's supposed to do, and added the result to the vector, which we then read out and show the user.

Of course, this shows almost nothing of what really happens in the application, mostly just the essential simplicity of using threads. Next, let's see what happens inside this method that we pass to each thread instance:

void threadFnc(int tid) {

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Starting thread " << tid << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

In the preceding code, we can see that the integer parameter being passed to the thread method is a thread identifier. To indicate that the thread is starting, a message containing the thread identifier is output. Since we're using a non-thread-safe method for this, we use the cout_mtx mutex instance to do this safely, ensuring that just one thread can write to cout at any time:

values_mtx.lock();

int val = values[0];

values_mtx.unlock();

When we obtain the initial value set in the vector, we copy it to a local variable so that we can immediately release the mutex for the vector to enable other threads to use the vector:

int rval = randGen(0, 10);

val += rval;

These last two lines contain the essence of what the threads created do: they take the initial value, and add a randomly generated value to it. The randGen() method takes two parameters, defining the range of the returned value:

cout_mtx.lock();

cout << "Thread " << tid << " adding " << rval << ". New value: " << val << ".\n";

cout_mtx.unlock();

values_mtx.lock();

values.push_back(val);

values_mtx.unlock();

}

Finally, we (safely) log a message informing the user of the result of this action before adding the new value to the vector. In both cases, we use the respective mutex to ensure that there can be no overlap when accessing the resource with any of the other threads.

Once the method reaches this point, the thread containing it will terminate, and the main thread will have one less thread to wait for to rejoin. The joining of a thread basically means that it stops existing, usually with a return value passed to the thread which created the thread. This can happen explicitly, with the main thread waiting for the child thread to finish, or in the background.

Lastly, we'll take a look at the randGen() method. Here we can see some multithreaded specific additions as well:

int randGen(const int& min, const int& max) {

static thread_local mt19937 generator(hash<thread::id>()(this_thread::get_id()));

uniform_int_distribution<int> distribution(min, max);

return distribution(generator)

}

This preceding method takes a minimum and maximum value as explained earlier, which limits the range of the random numbers this method can return. At its core, it uses a mt19937-based generator, which employs a 32-bit Mersenne Twister algorithm with a state size of 19937 bits. This is a common and appropriate choice for most applications.

Of note here is the use of the thread_local keyword. What this means is that even though it is defined as a static variable, its scope will be limited to the thread using it. Every thread will thus create its own generator instance, which is important when using the random number API in the STL.

A hash of the internal thread identifier is used as a seed for the generator. This ensures that each thread gets a fairly unique seed for its generator instance, allowing for better random number sequences.

Finally, we create a new uniform_int_distribution instance using the provided minimum and maximum limits, and use it together with the generator instance to generate the random number which we return.