A data race, also known as a race condition, occurs when two or more threads attempt to write to the same shared memory simultaneously. As a result, the state of the shared memory during and at the end of the sequence of instructions executed by each thread is by definition, non-deterministic.

As we saw in Chapter 6, Debugging Multithreaded Code, data races are reported quite often by tools used to debug multi-threaded applications. For example:

==6984== Possible data race during write of size 1 at 0x5CD9260 by thread #1

==6984== Locks held: none

==6984== at 0x40362C: Worker::stop() (worker.h:37)

==6984== by 0x403184: Dispatcher::stop() (dispatcher.cpp:50)

==6984== by 0x409163: main (main.cpp:70)

==6984==

==6984== This conflicts with a previous read of size 1 by thread #2

==6984== Locks held: none

==6984== at 0x401E0E: Worker::run() (worker.cpp:51)

==6984== by 0x408FA4: void std::_Mem_fn_base<void (Worker::*)(), true>::operator()<, void>(Worker*) const (in /media/sf_Projects/Cerflet/dispatcher/dispatcher_demo)

==6984== by 0x408F38: void std::_Bind_simple<std::_Mem_fn<void (Worker::*)()> (Worker*)>::_M_invoke<0ul>(std::_Index_tuple<0ul>) (functional:1531)

==6984== by 0x408E3F: std::_Bind_simple<std::_Mem_fn<void (Worker::*)()> (Worker*)>::operator()() (functional:1520)

==6984== by 0x408D47: std::thread::_Impl<std::_Bind_simple<std::_Mem_fn<void (Worker::*)()> (Worker*)> >::_M_run() (thread:115)

==6984== by 0x4EF8C7F: ??? (in /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.21)

==6984== by 0x4C34DB6: ??? (in /usr/lib/valgrind/vgpreload_helgrind-amd64-linux.so)

==6984== by 0x53DF6B9: start_thread (pthread_create.c:333)

==6984== Address 0x5cd9260 is 96 bytes inside a block of size 104 alloc'd

==6984== at 0x4C2F50F: operator new(unsigned long) (in /usr/lib/valgrind/vgpreload_helgrind-amd64-linux.so)

==6984== by 0x40308F: Dispatcher::init(int) (dispatcher.cpp:38)

==6984== by 0x4090A0: main (main.cpp:51)

==6984== Block was alloc'd by thread #1

The code which generated the preceding warning was the following:

bool Dispatcher::stop() {

for (int i = 0; i < allWorkers.size(); ++i) {

allWorkers[i]->stop();

}

cout << "Stopped workers.\n";

for (int j = 0; j < threads.size(); ++j) {

threads[j]->join();

cout << "Joined threads.\n";

}

}

Consider this code in the Worker instance:

void stop() { running = false; }

We also have:

void Worker::run() {

while (running) {

if (ready) {

ready = false;

request->process();

request->finish();

}

if (Dispatcher::addWorker(this)) {

while (!ready && running) {

unique_lock<mutex> ulock(mtx);

if (cv.wait_for(ulock, chrono::seconds(1)) == cv_status::timeout) {

}

}

}

}

}

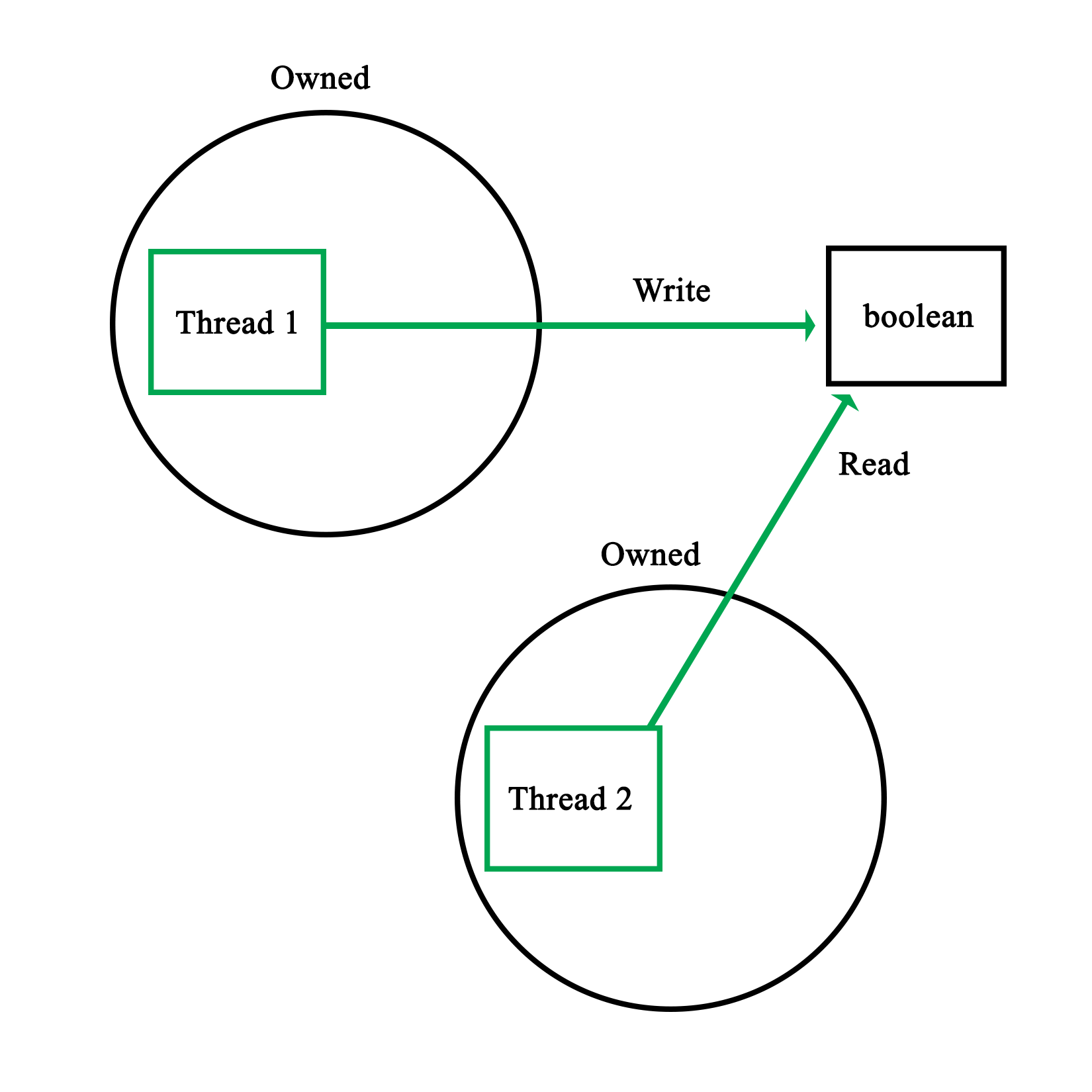

Here, running is a Boolean variable that is being set to false (writing to it from one thread), signaling the worker thread that it should terminate its waiting loop, where reading the Boolean variable is done from a different process, the main thread versus the worker thread:

This particular example's warning was due to a Boolean variable being simultaneously written and read. Naturally, the reason why this specific situation is safe has to do with atomics, as explained in detail in Chapter 8, Atomic Operations - Working with the Hardware.

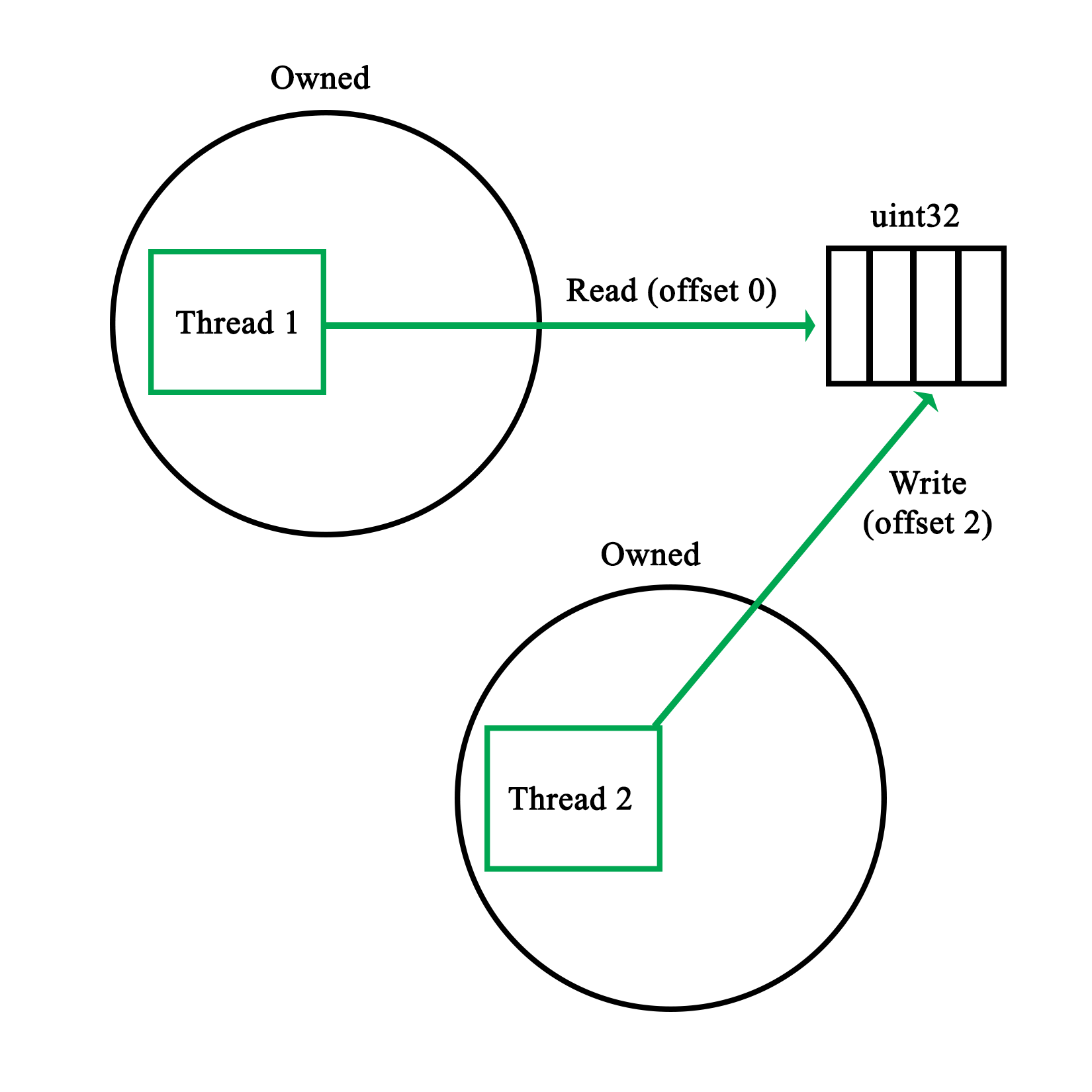

The reason why even an operation like this is potentially risky is because the reading operation may occur while the variable is still in the process of being updated. In the case of, for example, a 32-bit integer, depending on the hardware architecture, updating this variable might be done in one operation, or multiple. In the latter case, the reading operation might read an intermediate value with unpredictable results:

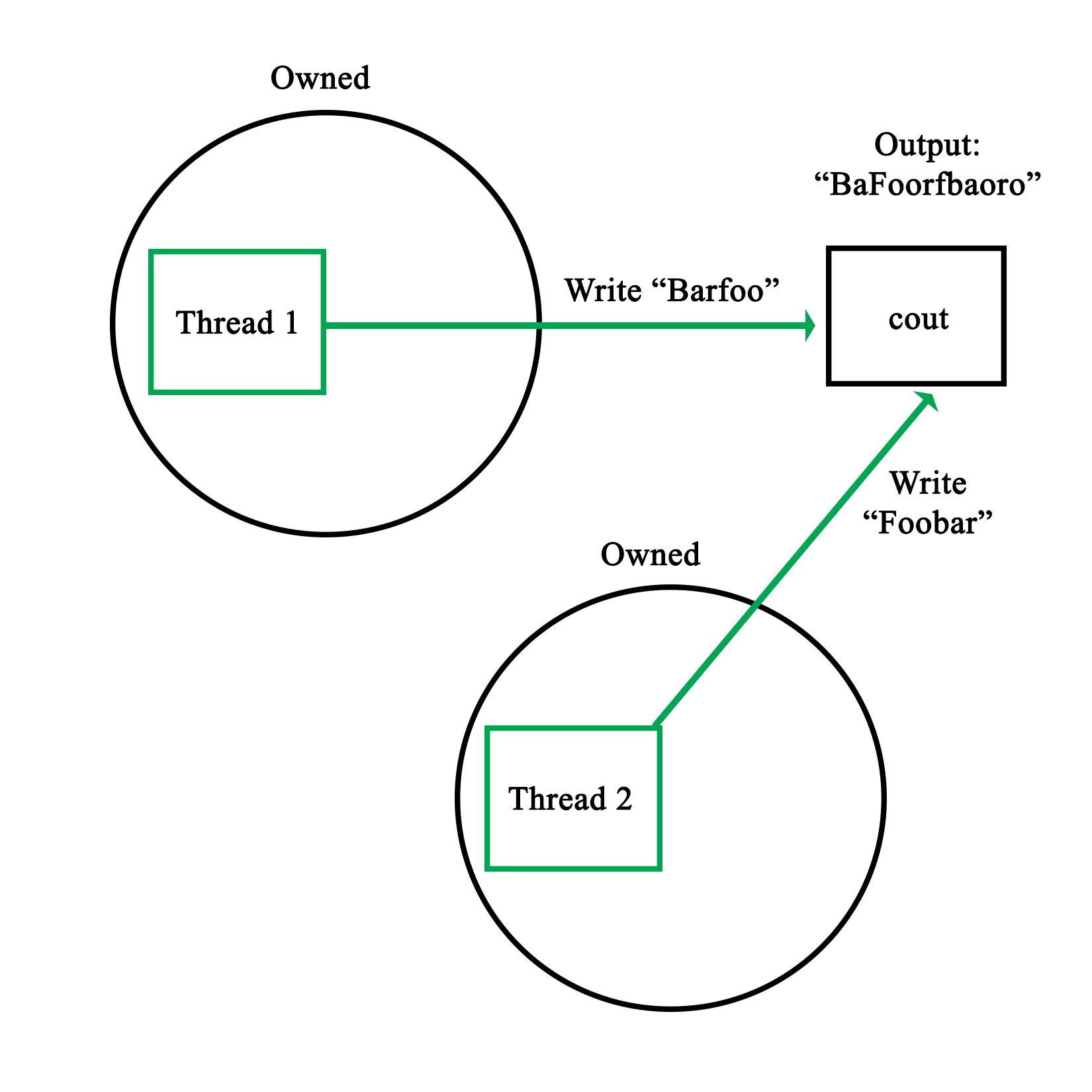

A more comical situation occurs when multiple threads write to a standard with out using, for example, cout. As this stream is not thread-safe, the resulting output stream will contain bits and pieces of the input streams, from whenever either of the threads got a chance to write:

The basic rules to prevent data races thus are:

- Never write to an unlocked, non-atomic, shared resource

- Never read from an unlocked, non-atomic, shared resource

This essentially means that any write or read has to be thread-safe. If one writes to shared memory, no other thread should be able to write to it at the same time. Similarly, when we read from a shared resource, we need to ensure that, at most, only other threads are also reading the shared resource.

This level of mutual exclusion is naturally accomplished by mutexes as we have seen in the preceding chapters, with a refinement offered in read-write locks, which allows for simultaneous readers while having writes as fully mutually exclusive events.

Of course, there are also gotchas with mutexes, as we will see in the following section.