A deadlock is described pretty succinctly by its name already. It occurs when two or more processes attempt to gain access to a resource which the other is holding, while that other thread is simultaneously waiting to gain access to a resource which it is holding.

For example:

- Thread 1 gains access to resource A

- Thread 1 and 2 both want to gain access to resource B

- Thread 2 wins and now owns B, with thread 1 still waiting on B

- Thread 2 wants to use A now, and waits for access

- Both thread 1 and 2 wait forever for a resource

In this situation, we assume that the thread will be able to gain access to each resource at some point, while the opposite is true, thanks to each thread holding on to the resource which the other thread needs.

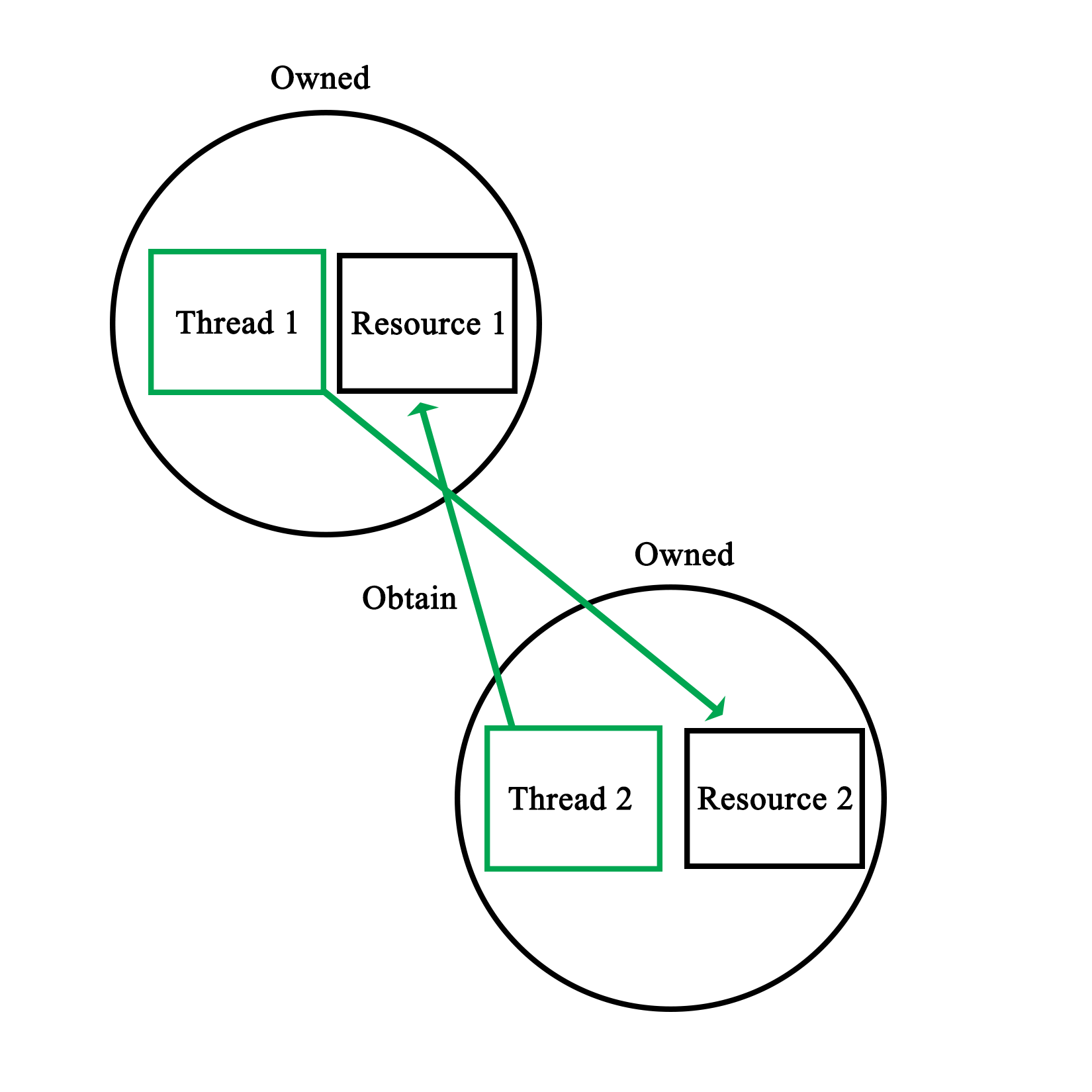

Visualized, this deadlock process would look like this:

This makes it clear that two basic rules when it comes to preventing deadlocks are:

- Try to never hold more than one lock at any time.

- Release any held locks as soon as you can.

We saw a real-life example of this in Chapter 4, Thread Synchronization and Communication, when we looked at the dispatcher demonstration code. This code involves two mutexes, to safe-guard access to two data structures:

void Dispatcher::addRequest(AbstractRequest* request) {

workersMutex.lock();

if (!workers.empty()) {

Worker* worker = workers.front();

worker->setRequest(request);

condition_variable* cv;

mutex* mtx;

worker->getCondition(cv);

worker->getMutex(mtx);

unique_lock<mutex> lock(*mtx);

cv->notify_one();

workers.pop();

workersMutex.unlock();

}

else {

workersMutex.unlock();

requestsMutex.lock();

requests.push(request);

requestsMutex.unlock();

}

}

The mutexes here are the workersMutex and requestsMutex variables. We can clearly see how at no point do we hold onto a mutex before trying to obtain access to the other one. We explicitly lock the workersMutex at the beginning of the method, so that we can safely check whether the workers data structure is empty or not.

If it's not empty, we hand the new request to a worker. Then, as we are done with the workers, data structure, we release the mutex. At this point, we retain zero mutexes. Nothing too complex here, as we just use a single mutex.

The interesting thing is in the else statement, for when there is no waiting worker and we need to obtain the second mutex. As we enter this scope, we retain one mutex. We could just attempt to obtain the requestsMutex and assume that it will work, yet this may deadlock, for this simple reason:

bool Dispatcher::addWorker(Worker* worker) {

bool wait = true;

requestsMutex.lock();

if (!requests.empty()) {

AbstractRequest* request = requests.front();

worker->setRequest(request);

requests.pop();

wait = false;

requestsMutex.unlock();

}

else {

requestsMutex.unlock();

workersMutex.lock();

workers.push(worker);

workersMutex.unlock();

}

return wait;

}

The accompanying function to the earlier preceding function we see also uses these two mutexes. Worse, this function runs in a separate thread. As a result, when the first function holds the workersMutex as it tries to obtain the requestsMutex, with this second function simultaneously holding the latter, while trying to obtain the former, we hit a deadlock.

In the functions, as we see them here, however, both rules have been implemented successfully; we never hold more than one lock at a time, and we release any locks we hold as soon as we can. This can be seen in both else cases, where as we enter them, we first release any locks we do not need any more.

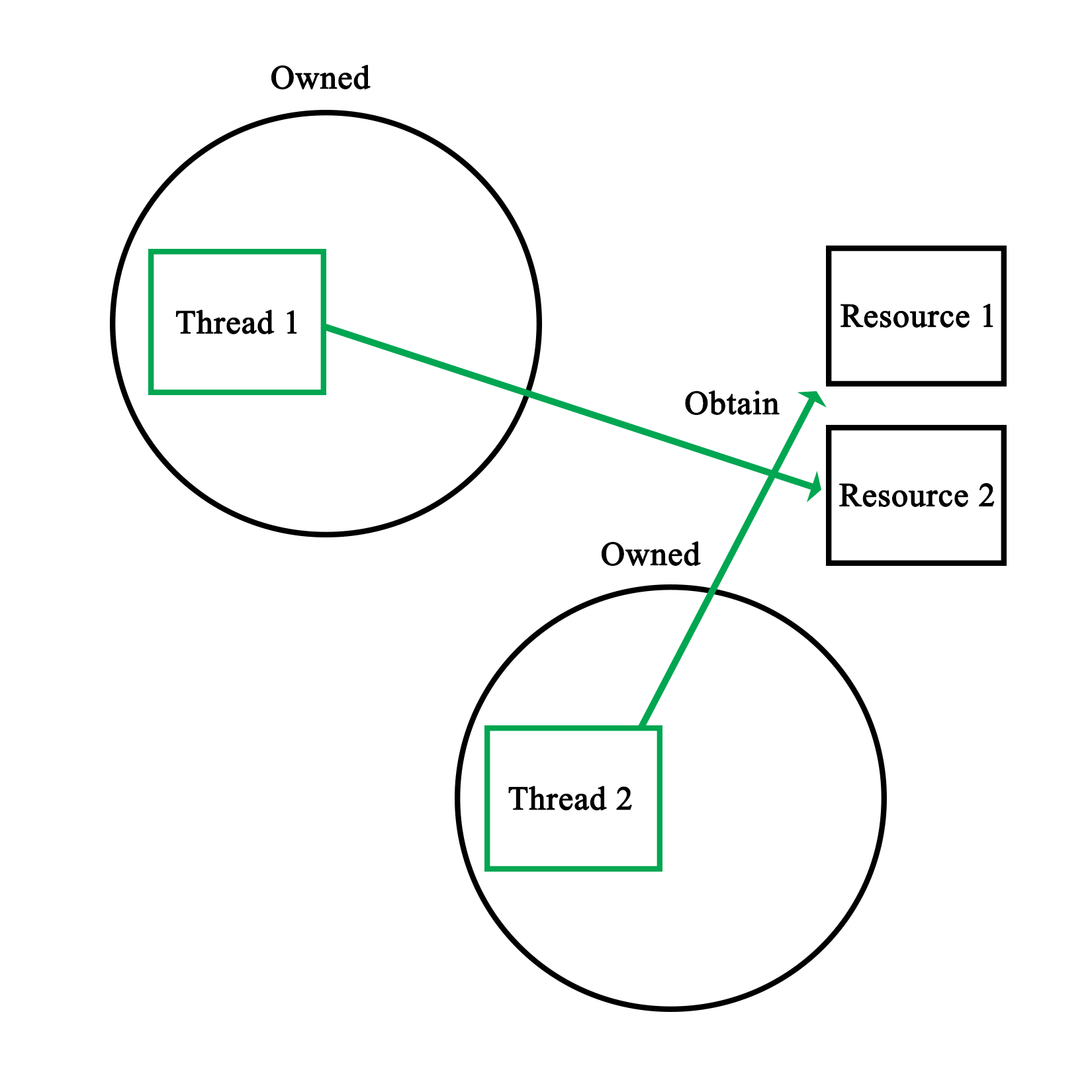

As in either case, we do not need to check respectively, the workers or requests data structures any more; we can release the relevant lock before we do anything else. This results in the following visualization:

It is of course possible that we may need to use data contained in two or more data structures or variables; data which is used by other threads simultaneously. It may be difficult to ensure that there is no chance of a deadlock in the resulting code.

Here, one may want to consider using temporary variables or similar. By locking the mutex, copying the relevant data, and immediately releasing the lock, there is no chance of deadlock with that mutex. Even if one has to write back results to the data structure, this can be done in a separate action.

This adds two more rules in preventing deadlocks:

- Try to never hold more than one lock at a time.

- Release any held locks as soon as you can.

- Never hold a lock any longer than is absolutely necessary.

- When holding multiple locks, mind their order.