Chapter 6. Network Security

In both traditional and cloud environments, network controls are an important part of overall security, because they rule out entire hosts or networks as entry points. If you can’t talk to a component at all, it is difficult to compromise it. Sometimes network controls are like the fences around a military base, making it more difficult to even get started without being detected. At other times they’re like a goalie that stops the ball after all other defenses have failed.

In this day and age, remaining disconnected from the Internet is not an option for most companies. The network is so fundamental to modern applications that it’s also almost impossible to tightly control every single communication. This means that network controls are in many cases secondary controls, and are here to help mitigate the effects of some other problem. If everything else were configured absolutely perfectly--that is, if all of your systems were perfectly patched for vulnerabilities, and all unnecessary services were turned off, and all services authenticated and authorized any users or other services perfectly—you could safely have no network controls at all! However, we don’t live in a perfect world, so we need to make use of the principle of defense in depth and add a layer of network controls to the controls we’ve discussed previously.

Differences from Traditional IT

Despite cries of “the perimeter is dead!” for many years, administrators have depended heavily upon the network perimeter for security in the past. Network security was sometimes the only security that system administrators relied upon. That’s not a good model for any environment, traditional or cloud.

In an on-premises environment, the perimeters are often easy to define. In the simplest case, you draw one dotted line (trust zone) around your DMZ, another dotted line around your internal network, and you carefully limit what comes into the DMZ and what comes from the DMZ to your internal network.

In the cloud, the decision of what is inside your perimeter, and the implementation of that perimeter, is often quite different from an on-premises environment. Your trust boundaries aren’t as obvious; if you’re making use of a database-as-a-service, is that inside or outside of your perimeter? If you have deployments around the world for disaster recovery and latency reasons, are those deployments all inside the same perimeters or different perimeters? In addition, creating these perimeters is no longer costly when you move to most cloud environments, so you can afford to have separate network segments for every application and use other services such as web application firewalls (WAFs) quickly and easily.

The most confusing thing about network controls in cloud environments is the large variety of delivery models you can use to build your application. What makes sense is different for each delivery model. We need to consider what a reasonable network security model looks like for:

-

IaaS environments, such as bare metal and virtual machines. These are the closest to traditional environments, but can often benefit from per-application segmentation, which is not feasible in most on-premises environments.

-

Orchestrated container-based environments, such as Docker and Kubernetes. If applications are decomposed into microservices, more granular network controls are possible inside the individual applications.

-

“Application PaaS” environments, such as Cloud Foundry, Elastic Beanstalk, and Heroku. These differ in the amount of network controls available. Some may allow for per-component isolation, some may not provide configurable firewall functions at all, and some may allow the use of firewall functions from the IaaS down.

-

Serverless or “function-as-a-service” environments, such as AWS Lambda, OpenWhisk, Azure Functions, and Google Cloud Functions. These operate in a shared environment that may not offer network controls, or may offer network controls only on the front end.

-

Software as a service (SaaS) environments. While some SaaS offerings provide simple network controls (such as access only via VPN or from whitelisted IP addresses), many do not.

In addition, many applications use more than one of these service models as part of the overall solution. For example, you might use both containers and traditional IaaS in your application, or a mixture of your own code with a SaaS. This may mean that some areas of your application can have better coverage for network controls than others, so it’s important to keep your overall threat model and biggest risks in mind.

Concepts and Definitions

Although cloud networking brings some new ideas to the table, many traditional concepts and definitions are still relevant in cloud environments. However, as described in the following subsections, they may be used in slightly different ways.

Whitelists and Blacklists

A “whitelist” is a list of things that are allowed, with everything else denied. A whitelist may be contrasted with a “blacklist”, which is a specific list of things to deny, while allowing everything else. In general, we want to be as restrictive as possible (without being silly), so most of the time we want to use whitelists and deny everything else.

IP whitelists are what many people think of as “traditional” firewall rules. They specify a source address, a destination address, and a destination port.1 IP whitelists can be useful for allowing only specific systems even to try to get access to your application. But because IP addresses are so easy to spoof, they should not be used as the only method to authenticate systems. That bears repeating: it’s almost never a good idea to authenticate or authorize access simply based on what part of the network the request comes from. Techniques such as TLS certificates should be used to authenticate other systems, with IP whitelists playing a supporting role.

IP whitelists also aren’t good for controlling user access. This is because users have the irritating habit of moving around on the network. In addition, IP addresses don’t belong to users, but to the systems they’re using, and NAT firewalls are still ubiquitous enough to make those IP addresses ambiguous. So IP whitelists don’t authenticate individuals; they authenticate systems or local networks in a relatively easy-to-fool way.

In many cloud environments, systems are created and destroyed regularly and you have little control over the IP addresses assigned to your systems. For that reason, IP whitelist source or destination addresses may need a much broader reach than was traditionally acceptable. They may even be specified as “0.0.0.0/0” (representing any address) in limited cases, which firewall administrators have traditionally not allowed for most rules. Remember that we are depending on many other controls besides just IP whitelisting to protect us.

With the rise of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) and Global Server Load Balancers (GSLBs), IP whitelists are also becoming less useful for some types of filtering (such as controls on outbound connections) because the network addresses can change rapidly. If you stick to requiring specific IP addresses for all rules and the CDN’s addresses change every week, you will end up with a lot of incorrectly blocked connections.

With those caveats in mind, IP whitelisting is still an important tool for cutting off network access where it isn’t needed, as long as it isn’t used as the primary defense or the only method to authenticate systems and users.

DMZ

A DMZ (which in warfare stands for “demilitarized zone”) is a concept from traditional network controls that carries over well to many cloud environments. It’s simply an area at the front of your application into which you let the least trusted traffic (such as visitor traffic). In most cases, you’ll place simpler, less trusted components in the DMZ, such as your proxy, load balancer, or static content web server. If that particular component is compromised, it should not provide a large advantage to the attacker.

A separate DMZ area may not make sense in some cloud environments, or may already be provided as part of the service model (particularly in PaaS environments).

Proxies

Proxies are simply components that receive a request, send the request to some other component to be serviced, and then send the response back to the original requester. In both cloud and traditional environments, they are often used in one of two models:

-

Forward proxies, where the requester is one of your components and the proxy is making requests on your behalf.

-

Reverse proxies, where the proxy is making requests on behalf of your users and relaying those requests in to your back-end servers.

Proxies can be useful for both functional requirements (to spread different requests out to different backend servers) and for security. Forward proxies are most often used to put rules on what traffic is allowed out of the network (see egress controls, discussed below).

Reverse proxies can improve security if there’s a vulnerability in a protocol or in a particular implementation of a protocol. In that case, the proxy may be compromised, but will usually provide an attacker with less access to the network or critical resources than the actual back-end server would.

Reverse proxies also provide a better user experience, by giving the end user the appearance of dealing with a single host. Cloud environments often make even more use of reverse proxies than traditional environments, because the application functions may be spread out across multiple back-end components. This is particularly true for microservice-friendly environments, such as Kubernetes, which includes several proxies as part of its core functionality.

Although you can have a proxy for almost any protocol, in practice the term proxy usually refers to an HTTP/HTTPS proxy.2

Software Defined Networking (SDN)

SDN is an often-overused term that can apply to many different virtualized networking technologies. In this context, however, SDN may be used by your cloud provider to implement the virtual networks that you use. The networks you see may actually be encapsulated on top of another network, and the rules for processing their traffic may be managed centrally instead of at each physical switch or router.

From your perspective, you can treat the network as if you were using physical switches and routers, even though the implementation may be a centralized control plane coordinating many different data plane devices to get traffic from one place to another.

Network Features Virtualization (NFV) or Virtual Network Functions (VNFs)

NFV, also called VNF, is just the idea that you no longer need a dedicated hardware box to perform many network functions, such as firewalling, routing, or IDS/IPS. You may use NFV appliances in your design explicitly, and NFV is also how many cloud providers provide network functions to you “as-a-service”. When possible, you should use the “as-a-service” functions rather than maintaining your own services.

Overlay Networks and Encapsulation

An overlay network is a virtual network that you create on top of your provider’s network. Overlay networks are often used to allow your virtual systems to communicate with each other as if they were on the same network, regardless of the underlying provider network.

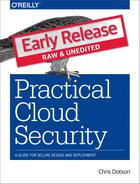

This is most often accomplished by “encapsulation”, where packets between your virtual systems are put inside packets sent across your provider network (Figure 6-1). Some common examples of encapsulation methods are VXLAN, GRE, or IP-in-IP.

Figure 6-1. Encapsulating IP packets between systems

For example, if virtual machine A on host 1 wants to talk to virtual machine B on host 2, it will send out a packet. Host 1 would wrap that packet up in another packet and send it to host 2, which will unwrap it and hand the original packet to virtual machine B. From the perspective of the virtual machines, they’re plugged into the same Ethernet switch and/or IP subnet, even though they may be across the world from one another.

Virtual Private Cloud (VPC)

In the original concept of “Cloud”, all provisioned systems were reachable on the Internet, even if the systems did not require inbound access from the Internet. Later, “private cloud” used the same delivery model as the public cloud, but for systems owned and operated by a single company instead of being shared among multiple companies. Private clouds could be located inside a company’s perimeter, with no access from outside and no sharing of resources.

Although each cloud provider’s definition of VPC can vary, the VPC hardly ever isolates virtual hosts to the same degree as a true private cloud. Shared resources in cloud IaaS often include storage, network, and compute resources. VPC, despite the name, generally deals only with network isolation, by allowing you to create separate virtual networks to keep your applications separate from other customers or applications.

That said, VPC is the best of both worlds for many companies. With VPC, you get the cost and elasticity benefits of a highly shared environment, and still have tight control over which components of your application you expose to the rest of the world. Cloud providers often implement VPC via software defined networking and/or overlay networks.

While it still makes sense in many cases for the front door of your application to be on the Internet, VPC allows you to keep the majority of your application in a private area unreachable by anyone but you. VPC can also allow you to keep your entire application private, accessible only by a VPN or other private link.

Network Address Translation (NAT)

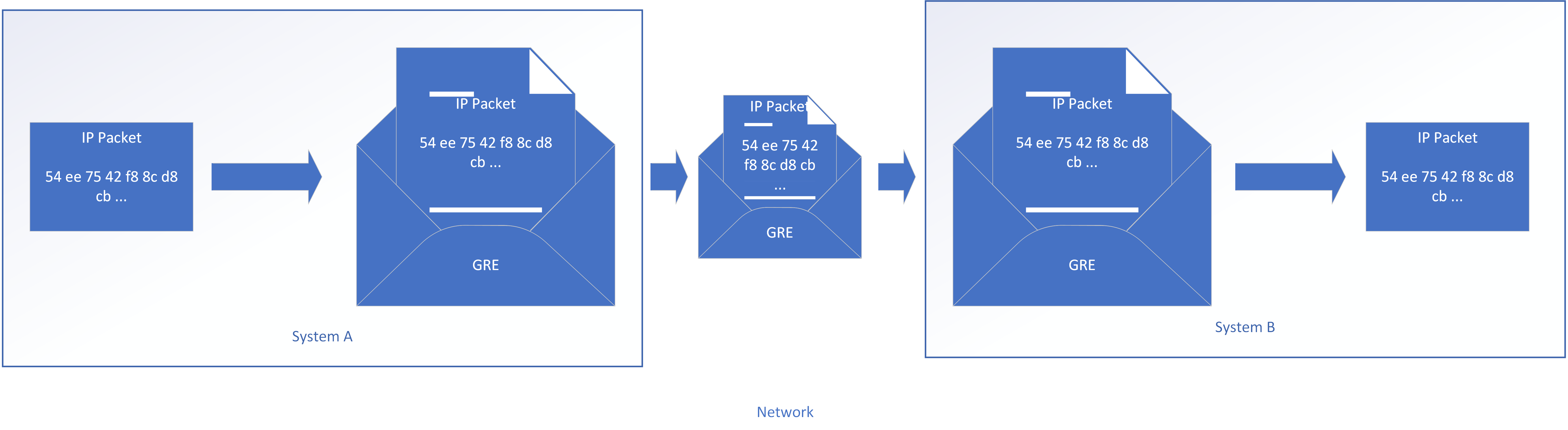

Network address translation was originally designed to combat the shortage of IP addresses by using the same IP addresses in multiple parts of the Internet, and “translating” those addresses to publicly routable addresses before sending them across the Internet (Figure 6-2). Although IPv6 will eventually save us from dealing with NAT, we’re stuck with it for the foreseeable future.

Figure 6-2. Network address translation in and out of a VPC

NAT is used heavily in cloud environments, particularly in VPC environments where you use private range addresses defined in RFC 1918 for the systems inside of the VPC. These addresses are easy to spot and start with “10.”, or “192.168.”, or “172.16.” through “172.31.” The difference in cloud environments is that you generally don’t have to manually configure NAT rules in a firewall. In most cases, you can simply define the rules using the portal or API, and the NAT function will be performed automatically for you.

Source NAT (SNAT, or “masquerading”) is changing the source addresses as packets leave your VPC area. Destination NAT (DNAT) is changing the destination address of packets from the outside as they enter your VPC area so that they go to a particular system inside the VPC. If you don’t perform DNAT to a system inside your VPC, then there’s no way for an outside system to reach the inside system.

There’s a commonly repeated phrase that “NAT is not security”. That is 100% true, but practically useless. Performing NAT doesn’t in itself provide any security; you’re just making a few changes as you route IP packets. However, the presence of NAT implies the existence of a firewall capable of doing NAT, which is also whitelisting the DNAT traffic, and which is configured to drop all packets that don’t match a DNAT rule (or process them locally). It’s the firewall providing the security, not NAT. However, the presence of NAT in almost all cases implies the security you get from whitelisting, and some people use NAT as shorthand for the translation plus these firewall features.

Using NAT in your solution doesn’t mean you’re relying only on the translation feature for security. You also have exactly the same security without NAT by using IP whitelists for the traffic you want to forward with an implied “drop everything else” rule at the bottom.

IPv6

Internet protocol version 6 is a system of addressing machines that makes far more addresses available than the traditional IPv4. From a security perspective, IPv6 has several improvements, such as mandatory support for IPsec transport security, Cryptographically Generated Addresses, and a larger address space that makes scanning a range of addresses much more time consuming.

IPv6 has the potential to make system administration tasks easier in the near future, because overlapping IPv4 ranges can make life difficult from the perspectives of asset management, event management, and firewall rules.3 (Which host does that 10.1.2.3 refer to? The one over here, or the one over there?) Although the use of IPv4 on the Internet will probably continue for decades, a move to IPv6 for internal administration purposes is much more likely.

From a practical point of view, the most important thing with IPv6 is to ensure that you maintain IPv6 whitelists if your systems have IPv6 addresses. Even though many end users don’t know about IPv6, attackers can use it to circumvent your IPv4 controls.

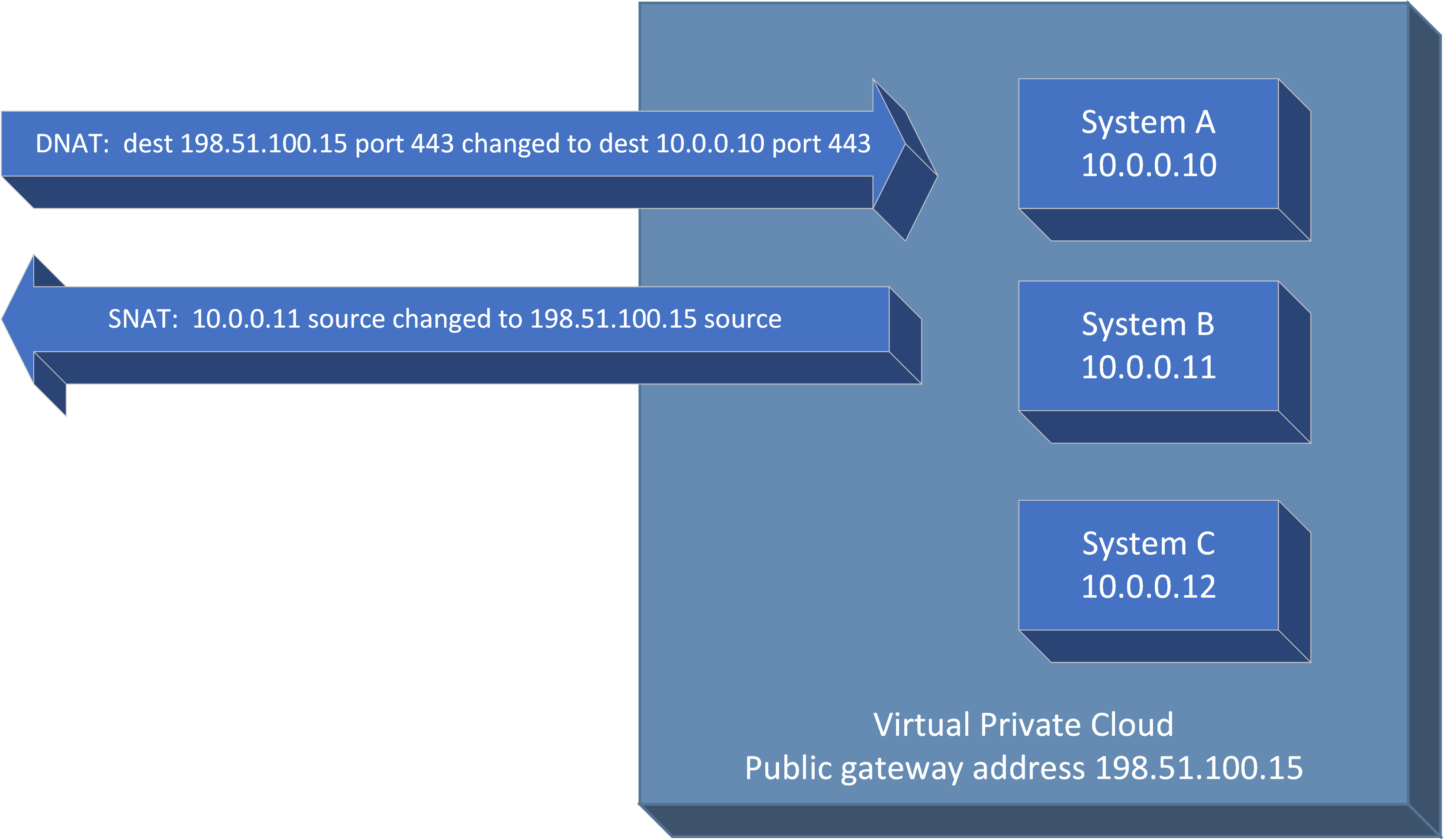

Putting it all together in the sample application

Now that we’ve covered some of the key concepts, the remainder of this chapter will be based on our simple web application in the cloud that is accessed from the Internet and that uses a back-end database (Figure 6-3). In this example, we’ll be protecting against a threat actor named Molly, whose primary motivation is stealing our customers’ personal information from the database to sell on the dark web.

Figure 6-3. Sample application with network controls

Note that this is just a somewhat intricate example for illustration purposes, so you may not need all of the controls pictured for your environment. I recommend that you prioritize network controls in the order listed in the following subsections. Don’t spend a lot of time designing the later controls until you’ve put the earlier controls in place and have verified that they are effective; it’s much better to have TLS and a simple firewall configured correctly and being monitored than to have five different network controls that are configured poorly and ignored.

To use an analogy, ensure your doors are locked securely before putting bars on your second story windows!

Encryption in Motion

TLS (Transport Layer Security, formerly known as SSL) is the most common method for securing communication of data “in motion” (flowing between systems on the network). Some people may categorize this as an application-level control rather than a network-level control, because in a traditional environment it’s often under the control of the “application team” rather than the “network team”. In cloud environments, those may not be separate groups, so it’s included as a network control here. Any way you classify it, encryption in motion is a very important security control.

Many components support TLS natively. In cloud environments, I recommend using TLS not just at the front end, but for all communications that cross a physical or virtual network switch. This includes communications that may realistically cross such boundaries in the future as components are moved around. Communications between components that will always remain on the same operating system, or between different containers in a pod in Kubernetes, do not gain a security benefit from using TLS.

There is debate in some circles as to whether it’s a good idea to encrypt traffic going across networks you control, because you lose the ability to inspect the traffic as it passes through your network. The implicit assumption is that it’s unlikely for an attacker to get through your perimeter to view the traffic that you want to inspect. As of this writing, one of the top causes of breaches is attacks on web application attacks, allowing an attacker into the application server-which is behind the perimeter, it should be noted. There’s no reason to think this trend will reverse. For this reason, I recommend encrypting all network traffic that contains information that would harm you if made public. This easy rule of thumb excludes network traffic such as “ping”, which contains no useful information for an attacker. Rather than relying upon network inspection to detect an attacker, you should rely upon event information generated by your systems. Refer to Chapter 7 for more information.

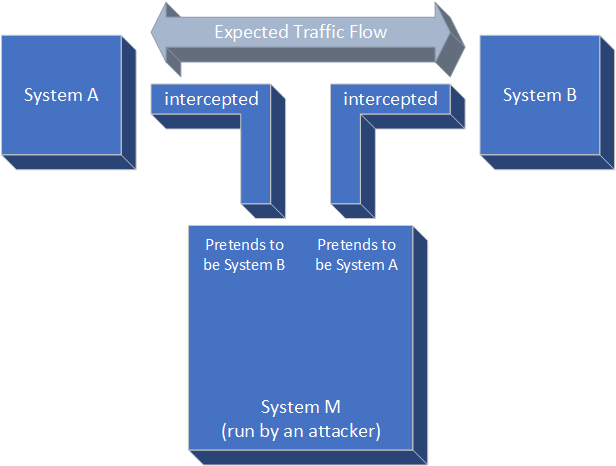

Simply turning on TLS is not sufficient, however. TLS loses most of its effectiveness if you do not also authenticate the other end of the connection by certificate checking, because it’s not difficult for an attacker to hijack a connection and perform a “man in the middle” attack. As an example, even on modern container environments it can be possible for a compromised container “M” to trick other containers “A” and “B” to send traffic through “M” (Figure 6-4). Without certificate checking, “A” thinks it has an encrypted TLS connection to “B”, when in reality it has an encrypted connection to “M”. “M” decrypts the connection, reads the passwords or other sensitive data, and then makes an encrypted connection to “B” and passes through the data (possibly changing it at the same time). TLS encryption doesn’t help at all in this situation without certificate checking!

Figure 6-4. Man in the middle attack

What this means is that you also have to perform key management-creating a separate key pair and getting a certificate signed for each one of your systems-which can be painful and difficult to automate.

Fortunately, in cloud environments this is becoming easier! One way to do this is via “identity documents”, which some cloud providers make available to systems when they’re provisioned. The provisioned system can retrieve a cryptographically signed identity document that can be used to prove its identity to other components. When you combine an identity document with the ability to automatically issue TLS certificates, you can have a system automatically come up, authenticate itself with a PKI provider, and get a keypair and certificate that are trusted by other components in your environment. In this fashion, you can be certain that you’re talking the the system you intended to and not to a man-in-the-middle attacker. You do have to trust the cloud provider, but you already have to trust them because they create instances and manipulate existing instances.

A couple of examples:

-

You can automatically create certificates using AWS Instance Identity Documents and Hashicorp Vault. When an AWS instance boots, it can retrieve its Instance Identity Document and signature and send those to Vault, which will verify the signature and provide a token for reading additional secrets. The instance can then use this token to have Vault automatically generate a keypair and sign the TLS certificate.

-

On Kubernetes environments with Istio, Istio Auth can provide keys and certs to Kubernetes containers. It does this by watching to see when new containers are created, automatically generating keys/certificates, and making them available to containers as secret mounts.

-

Cloud certificate storage systems, such as AWS Certificate Manager, Azure Key Vault, and IBM Cloud Certificate Manager can easily provision certificates and safely store private keys.

Heartbleed notwithstanding, TLS is still a very secure protocol if configured properly. At the time of this writing, TLS 1.3 is the current version of the protocol that should be used, and only specific ciphersuites4 should be allowed. While there are definitive references for valid ciphersuites, such as NIST SP 800-52, for most users an online test such as one provided by SSL Labs is the fastest way to verify whether a public-facing TLS interface is configured properly. Once you have verified your public interface, you can then copy a valid configuration to any non-public-facing TLS interfaces you have. Network vulnerability scanning tools such as Nessus can also highlight weak protocols or ciphersuites allowed by your systems.

You will need to include new ciphersuites as they become available, and remove old ciphersuites from your configuration as vulnerabilities are discovered. You can review acceptable ciphersuites as part of your vulnerability management processes, because network vulnerability scanners can spot out-of-date ciphersuites that are no longer secure. Fortunately, ciphersuites are compromised at a much lower rate than other tools in common use, where vulnerabilities are routinely discovered.

It’s also important to generate new TLS private keys whenever getting a new certificate, or whenever they may have been compromised. Solutions such as Let’s Encrypt generate new private keys and renew certificates automatically, which can limit the amount of time that someone can impersonate your web site if the private keys are stolen.

Our attacker, Molly, may be able to snoop on or manipulate the connection between the user and the web server, or between the web servers and the application servers, or between the application servers and the database. With a correct TLS implementation, she shouldn’t be able to get any useful data (such as the credentials for accessing the database, in order to steal the data).

Firewalls and Network Segmentation

Firewalls are a network control that is familiar to many people. Once you have a plan to secure all of your communications, you can begin dividing your network into separate segments (based on trust zones) and putting firewall controls in place. At their simplest, network firewalls implement IP whitelists between two networks (each of which may contain many hosts). Firewall appliances may also perform many other functions, such as a terminating VPN, IDS/IPS, or WAF, but for this section, we’ll concentrate on the IP whitelist functionality.

Firewalls are usually used for two main purposes:

-

Perimeter control, for separating your systems from the rest of the world

-

Internal segmentation, to keep sets of systems separated from one another

You might use the same technologies to accomplish both purposes. One important difference is in what you pay attention to, however. On the Internet there’s always someone trying to attack you, so alerts from the perimeter are very “noisy”. On internal segmentation firewalls, any denied connection attempts are either an attacker trying to move laterally or a misconfiguration. Either one should be investigated!

There are three main firewall implementations in the cloud:

-

Virtual firewall appliances. While still appropriate for some implementations, this is largely a “lift and shift” model from on-premises environments. Note that most virtual firewall appliances are “next generation” appliances that combine whitelisting with additional functionality described below, such as WAF or IDS/IPS. While you design and implement your network controls, treat these separate functions as if they were just separate devices plugged back-to-back, and don’t worry about designing the higher-level controls until you have the perimeter and internal segmentation designed.

-

Network access control lists (ACLs). Instead of operating your own firewall appliance, you simply define rules for each network about what’s allowed into and out of that network.

-

Security groups. Similar to Network ACLs, you simply define security group rules and they’re implemented “as-a-service”. The difference is that security groups apply at a per-OS or per-pod level instead of per-network. Some implementations may not have all the features that Network ACLs provide, such as logging of accepted and denied connections.

Table 6-1 shows, as of this writing, the IP whitelisting controls available on popular cloud services.

| Provider | IP Whitelisting Features |

|---|---|

Amazon Web Services IaaS |

VPC and Network ACLs; security groups; and virtual appliances available in the marketplace |

Microsoft Azure IaaS |

Virtual Networks, Network Security Groups (NSGs), and Network Virtual Appliances |

Google Compute Platform IaaS |

VPC and firewall rules |

IBM Cloud IaaS |

VPC with network ACLs; Gateway Appliances; and Security Groups |

Kubernetes (overlay on an IaaS) |

Network policies |

Perimeter Control

The first firewall control you should design is a perimeter of some form. This may be implemented via a firewall appliance, but more often will simply be a Virtual Private Cloud with a network ACL. Most providers have the ability to create network ACLs. If so, you don’t need to worry about the underlying firewall at all; you simply provide rules between security zones and everything below that is abstracted from you.

You may be tempted to share a perimeter among several different applications. In traditional environments, firewalls are often costly and time-consuming to use; they require a physical device, and in many organizations a separate team will configure the firewall. For those reasons, multiple applications that don’t actually need to communicate with one another often share network segments. This can be a significant security risk, because a breach in a less important application can provide a foothold for an attacker to pivot to a more important application, often undetected.

In cloud environments, you should give each application its own separate perimeter controls. This may sound like a lot of trouble, but remember that in most cases you are just providing rules for the cloud provider’s firewall to enforce. By defining the network perimeter rules separately for each application, you can manage the rules along with configuration of the application, and each application can change its own perimeter rules without affecting other applications (unless the other applications can no longer reach it at all!).

In our example, for perimeter control and internal segmentation we’ll put the entire application inside a VPC with private subnets for the backend web and application servers and network ACLs. Depending on the application, we might have also chosen to use only security groups without VPC for all systems in the application, or to use virtual firewall appliances as the interface between the Internet and the rest of the application.

On AWS, GCP, and IBM Cloud, we would create a VPC with one Public subnet for the web servers (DMZ), and a Private Subnet for the application servers. On Azure, we would create Virtual Networks with subnets. We would then specify what communications should be allowed into our VPC from the Internet.

Internal Segmentation

Okay, now we have a perimeter behind which we can place our sample application (in the form of a VPC) so that we can allow only specific traffic in to our application. The next step is to implement network controls inside our application. Your application will generally have a few different trust boundaries such as the web layer (DMZ), the application layer, and the database layer.

In the traditional IT world, internal segmentation was often messy: you would need lots of different 802.1Q VLANs, which had to be requested via a ticket, or you would use a host firewall solution that you could centrally manage. In cloud environments, a few clicks or invocations of the APIs can create as many subnets as you need, often without any additional charges.

Once we have created our three subnets (some of them may have been created automatically when we created a VPC), we’re ready to apply Network ACLs or Network Security groups. In our simple example, we would allow only HTTPS traffic from the Internet to the web subnet, HTTPS traffic from the web subnet into the application subnet, and ssh into both. This is very similar to traditional environments, except that we can create these subnets so quickly and easily that we can afford to have separate ones for each application, with no sharing.

Most cloud providers also allow you to use a command line tool or a REST API to do everything you can on the portal. This is essential for automating deployments, although it does require you do to a little more manual “plumbing” work in some cases. In this case, we would create a VPC with one public subnet and two private subnets, attach an Internet gateway, route traffic out the gateway, and allow only tcp/443 into the DMZ subnet. Rather than create a script from scratch, I recommend that you use an infrastructure-as-code tool like Hashicorp Terraform, AWS Cloud Formation, or OpenStack Heat templates. Tools such as these allow you to declare what you want your network infrastructure to look like, and automatically issue the correct commands to create or modify your cloud infrastructure to match.

Cloud web consoles, command line invocations, and APIs change over time, so the best reference is usually the cloud provider’s online documentation. The important concept is that most cloud platforms allow you to create a “Virtual Private Cloud” that contains one or more subnets that you can use for trust zones.

Security Groups

At this point, you already have a perimeter and firewall rules, so why would you need more IP whitelists? The reason is that it’s possible that our attacker has obtained a small foothold into one of our subnets (probably the DMZ), which gets her behind our subnet controls described above. We’d like to block or detect her attempts to move elsewhere within our application, such as by attacking our administrative ports. To do this, we’ll use per-system firewalls.

Although you can certainly use local firewalls on your operating system, most cloud providers provide a method for the cloud infrastructure itself to filter traffic coming into your virtual system before your operating system sees it. This feature is often called “security groups”.5

Tip

If you choose to use Security Groups to meet your internal network segmentation requirements, make sure that you can detect denied connections, because not all implementations permit feeding these denied attempts to a SIEM. Please refer to Chapter 7 for more information.

Just as in traditional environments, configure your security groups to allow traffic in only on the ports needed for that type of system. For example, on an application server, allow traffic in only on the application server port. In addition, restrict administrative access ports, such as SSH, to particular IP addresses that you know you’ll perform administration functions from, such as your bastion host or corporate IP range. In most implementations, you not only can specify a specific IP source, but can also allow traffic from any instance that has another security group specified.

If you allow administrative access from your entire company’s IP range, note that any compromised workstation, server, or mobile device in your environment can be used to access the administrative interface. This is still better than leaving it open to the entire Internet, but don’t get complacent: these ports should still be protected as if they were open to the Internet! That means they should be scanned for vulnerabilities, and authenticate all connections via complex passwords, or keys and certificates.

In some smaller deployments, you might choose to put your entire application into a single VPC (or even directly on the public Internet) and use security groups for both perimeter control and internal segmentation. For example, the database server may have a security group in place that allows SSH access only from a subnet you trust, and allows database access only from your application servers. If there’s a one-to-one correspondence between your security groups and your subnets (that is, everything on the same subnet also uses the same security group), defining subnets might create additional complexity without much benefit. While most implementations will benefit from both, security groups have a slight edge in that they offer better protection against a misconfigured service on one of your systems; with network ACLs, anything that gets into the subnet can exploit that misconfigured service.

Like many other network controls, internal segmentation is a redundant layer of security. It will help you if there’s an issue somewhere else, such as because you misconfigured your perimeter, an attacker gets in past your perimeter, or you accidentally left a service running with default credentials.

Service Endpoints

It’s important to note that some layers of your application, like the database, might be shared as-a-service functions. This means that they’re actually outside your perimeter, although they can be virtually behind your perimeter via proper access controls and service endpoints. To illustrate this, the version of the sample application in this chapter shows a database-as-a-service in use.

“Service endpoint” functionality is available on several cloud providers. An endpoint is just a place to go to reach the service, and a service endpoint makes your as-a-service instance directly reachable via an IP address on your virtual private cloud subnet. This is convenient in that you don’t have to specify outbound firewall rules to reach the instance, but the real beauty of this feature is that the service can be accessed only via that virtual IP address. For example, even if someone on the Internet obtains the correct credentials for your database, they still cannot access the instance. They would need to get into your VPC and talk to the virtual IP address there using the credentials.

Even if service endpoint functionality is not available, the as-a-service function might allow you to whitelist which IPs can connect. If so, this is mostly equivalent to service endpoint functionality (although slightly more difficult) and can help guard against stolen or weak credentials.

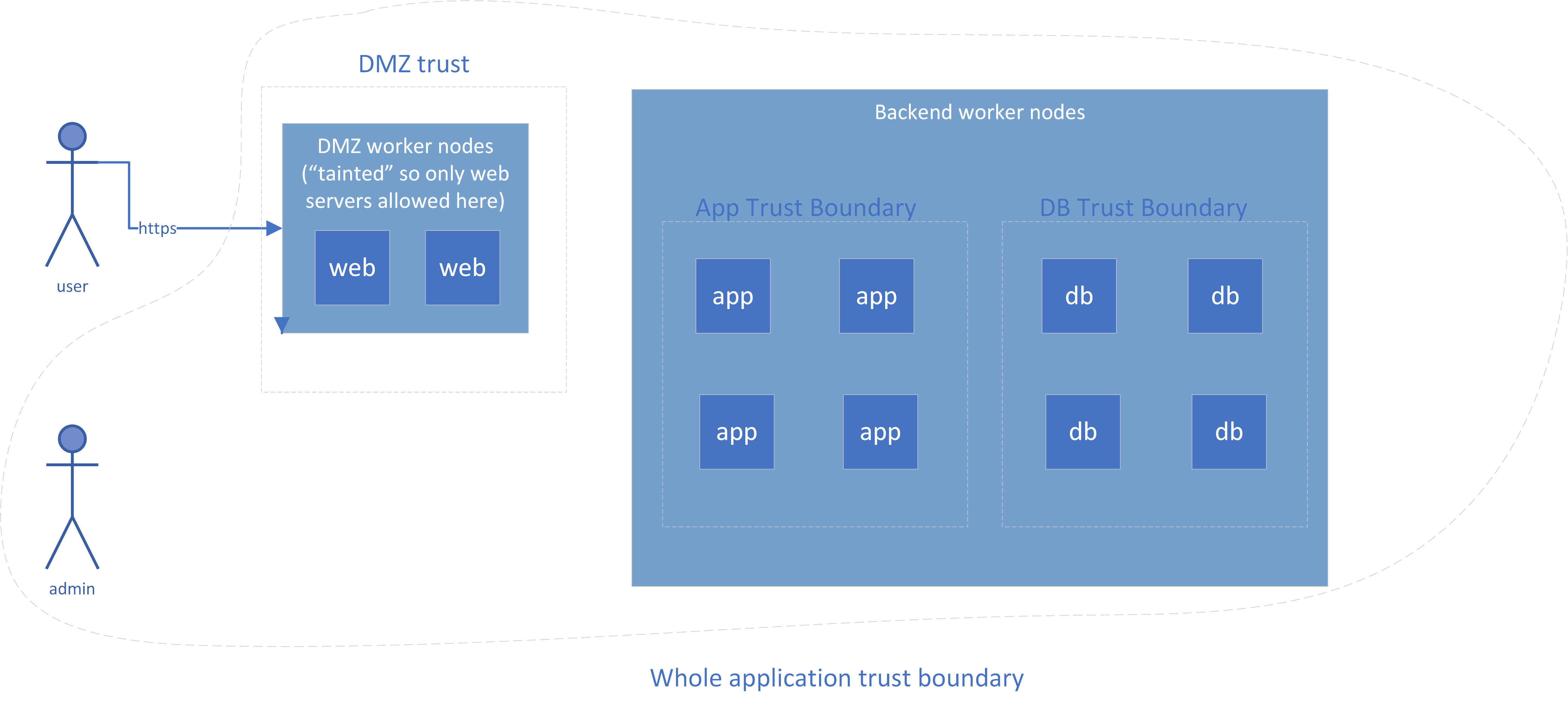

Container Firewalling and Network Segmentation

What about isolating access in a container world? Although the implementation differs somewhat, the concepts are still essentially the same. At the time of this writing, Kubernetes is the most popular container orchestration solution, so I’ll focus on it here so as not to get lost in vagueness.

For a perimeter, you will typically use existing IaaS network controls such as VPC or security groups, but you may also use Kubernetes network policies to enact local firewalls on the worker nodes. In either case, the goal is to prevent any inbound traffic except to the nodeport, ingress controller, or whatever mechanism you’re using to accept traffic from outside. This can be an extra safeguard to prevent a misconfigured backed service from accidentally being reachable from the Internet.

For internal segmentation, you can use Kubernetes network policies to isolate pods. For example, the database pods can be configured to only allow access from the application server pods.

The equivalent functionality to security groups is already “built in” for many use cases. In container networking, you allow access only to specific ports on the container as part of the configuration. This performs much of the functionality of security groups at the container level. In addition, containers are usually running only the specific processes needed and no other unnecessary services. One of the primary benefits of security groups is that they act as a second layer of protection in case unnecessary services are running, to prevent access to them.

For a certain amount of virtual machine separation, you can also “taint” specific worker nodes so that only DMZ pods will be scheduled on those nodes. You might put those nodes into a separate VPC subnet. Figure 6-5 shows an alternate version of the sample application using containers.

Figure 6-5. Sample Container Network Controls

Note that this addresses only network isolation; compute isolation is still a concern in the container world, which is why Figure 6-5 showed the most vulnerable systems isolated to separate worker nodes. Containers all run on the same operating system, and an operating system provides a lot more functionality than the virtualized hardware of a VM, which means that there are more possibilities for an attacker who gets inside a container to “break out” and affect other containers.

Allow Administrative Access

Now that you have set up some walls around your application and some internal trip wires to catch anyone who’s gotten inside, other systems or your administrators may need a way of getting past your perimeter to maintain your application.

One of the worst things our attacker, Molly, can do is to get access to administrative interfaces—for example, direct access to our database administration interfaces—and pull all of our customer data out through the back door. Requiring that all administrative access take place via a VPN or a bastion host makes her have to go through considerable effort before even attempting to log into our back-end database. This section discusses when to use VPNs or bastion hosts.

Note

Your administrators might not need to get inside the perimeter if you have a method to run commands on servers (such as AWS Systems Manager Run Command, or kubectl exec), or if your administrators can always diagnose problems via the logs coming out and replace any component that’s acting up with a new version. It’s ideal if you can run day-to-day operations without getting behind the perimeter, but many applications aren’t designed for this.

Bastion Hosts

Bastion hosts (also called “jump hosts”) are systems for administrative access that are accessible from a less trusted network (such as the Internet). The network is set up so that all communication to the internal networks must flow through a bastion host.

A bastion host has the following useful security properties:

-

Like a VPN, it reduces your attack surface, because it’s a single-purpose hardened host that other machines “hide” behind.

-

It can allow for session recording, which is very useful for advanced privileged user monitoring. Session recordings may be spot-checked to catch an insider attack, use of stolen credentials, or an attacker’s use of a Remote Access Trojan (RAT)6 to control a legitimate administrator’s workstation.

-

In some cases, a bastion host performs a “protocol shift” (for example, incoming RDP connections where a user then uses a web browser for HTTPS connections). This can make things more difficult for attackers because the attacker needs to compromise both the bastion host and the destination application.

I recommend using bastion hosts if the advanced capabilities of session recording or protocol shifts are useful in your environment, or if a client-to-site VPN is not suitable for some reason. Otherwise, I recommend using client-to-site VPNs provided as-a-service for administrative access, because it’s one less thing for you to maintain.

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs)

Creating a VPN is like stretching a virtual cable from one location to another. In reality, the connectivity is actually performed by using an encrypted session across an untrusted network like the Internet. There are two primary VPN functions, which are very different:

-

Site-to-site communications, where two separate sets of systems communicate with one another using an encrypted “tunnel” over an untrusted network such as the Internet. This might be used for all users at a site to get through the perimeter to access the application, or for one application to talk to another application. It should not be used to protect administrative interfaces.

-

Client-to-site (or “road warrior”) communications, where an individual user with a workstation or mobile device virtually “plugs in” to a remote network. This might be used by an end user to access an application or by an administrator to work on the individual components of an application.

The following subsections describe each solution and show its advantages and drawbacks.

Site-to-site VPNs

VPNs for site-to-site communications can provide additional security, but they can also lead to poor security practices. For this reason, I no longer recommend using a site-to-site VPN if all of the communication flows between the sites use TLS, and IP whitelisting is applied where feasible. The reasons for this are:

-

Setting up a site-to-site VPN is more work than using TLS. A VPN requires configuring two firewalls (or often four, as they’re usually redundant pairs) with the proper parameters, credentials, and routing information.

-

Using a site-to-site VPN is arguably less secure if it leads to the use of insecure protocols. That’s because VPNs still leave the data in motion unprotected on either end before entering the tunnel, so an attacker who manages to get inside the perimeter may be able to eavesdrop on that traffic.7

-

Site-to-site VPNs are too “coarse-grained”, in that they’ll allow anyone on one network (often a large corporate network) to access another network (such as your administrative interfaces). It’s better to perform access control at the administrative user level than the network level.

Of course, you can use both a VPN and TLS connections inside the VPN for additional security. However, your efforts are probably better spent elsewhere in most cases, and you should definitely prioritize end-to-end encryption with TLS first. There is some limited security benefit in hiding the details of your communications (such as destination ports) from an attacker. If you do choose to use both TLS and a VPN, make sure to use a different protocol for your VPN, such as IPsec, or the same vulnerability may allow an attacker to compromise both the VPN and the transport security inside it.

Client-to-site VPNs

I no longer recommend client-to-site VPNs for end user access to most “internal” corporate applications.8 VPNs are inconvenient for end users and can be detrimental to battery life on mobile devices. Plus, once the user base is large enough, it’s often possible for an attacker to request, and be granted, regular user access. You should already have implemented the controls in the Identity and Access Management section, so a VPN layer may be a redundant implementation of the same access management controls your application is already using. If you do decide to require VPN access for your application, I recommend using a completely different set of credentials for the VPN, such as a TLS certificate issued by a completely different administrative domain from tho one issuing your normal user credentials.

However, client-to-site VPNs can be a good way for your administrators to gain access to the internal workings of your cloud environment. (Another good way is a “bastion host” or “jump host”, discussed above). The reasons I suggest a VPN for administrators, and not for regular end users, are that the back-end connections used by administrators are higher risk (because there are more of them, so they’re harder to secure), the cost is lower (because there are fewer administrators than end users), and there should be few enough administrators that it’s harder for an attacker to accidentally be granted access. So VPN access is worth it for administrators, but not for end users in most cases.

VPNs have both the benefit and drawback of permitting more protocols than bastion hosts. Being able to use additional protocols can make life easier for administrators, but can also make it easier for an attacker driving a compromised workstation to attack the production network. VPNs also don’t support session recording, so for these reasons, higher-security environments will often use bastion hosts.

Client-to-site VPNs are usually easy to use, but often require some sort of software to be installed on the administrator’s workstation, which can be a concern in companies that restrict software installation. Most solutions support the use of complex credentials (such as a certificate or a key) and two factor access (2FA) to mitigate the risk of easily guessed credentials or stolen credentials.

Examples of client-to-site VPN access on different cloud platforms are listed in Table 6-2.

| Provider | VPN Features |

|---|---|

Amazon Web Services |

Amazon Managed VPN |

Microsoft Azure |

VPN Gateway |

Google Compute Platform |

Google Cloud VPN |

IBM Cloud |

IBM Cloud VPN |

Note

Some industry or regulatory certifications may require you log the creation of VPN connections. Make sure you can get connection logs out of your VPN solution!

Web Application Firewalls and RASP

At this point you should have a perimeter, internal controls, and a way for your administrators to get through the perimeter as needed. Now, let’s move on to some more advanced controls.

A Web Application Firewall (WAF) is a great way to provide an extra layer of protection against common programming errors in your application, as well as vulnerabilities in libraries or other dependencies that you use. A WAF is really just a smart proxy; it gets the request, checks the request for various bad behaviors such as SQL injection attacks, and then makes the request to the back-end system if it’s safe to do so. WAFs can protect against attacks that traditional firewalls can’t, because the TCP/IP traffic is perfectly legitimate and the traditional firewalls don’t look at the actual effects on the application layer.

WAFs can also help you respond quickly to a new vulnerability, because it’s often faster to configure the WAF to block the exploit than to update all of your systems.

Warning

In traditional environments, WAFs can often be a “blinky box” that’s put in place and then ignored. In both traditional and cloud environments, if you don’t set up the proper rules, customized for your application, maintain those rules, and look at alerts, you probably aren’t getting a lot of value from your WAF. Many WAFs are just used to “check a box” and are only in place because they offer an easier route to PCI compliance than code inspections.

In cloud environments, a WAF may be delivered as Software-as-a-Service, as an appliance, or in a distributed (host-based) model. In the cases of a WAF service or appliance, you must be careful to ensure that all traffic actually passes through the WAF. This often requires the use of IP whitelists to block all traffic that’s not coming from the WAF, which can lead to additional maintenance because the list of IP addresses for requests coming from a Cloud WAF offering will vary over time. It can also be difficult to route all traffic through your WAF appliance without creating a single point of failure. Some cloud providers offer services, such as AWS Firewall Manager, that help you ensure that your applications are always covered by a WAF.

A host-based model doesn’t have these problems; all traffic will be processed by the distributed WAF regardless. You do need to have good inventory management and deployment processes (to ensure that the WAF gets deployed to each system), but this is often an easier task than ensuring that all traffic flows through a SaaS or appliance.

A RASP (Runtime Application Self-Protection) module is similar to a WAF in many ways. Like a WAF, RASP modules attempt to block exploits at the application layer, but the mechanism used is significantly different. A RASP works by embedding alongside your application code and watching how requests to the application are handled by the application, instead of only seeing the requests. RASP modules must support the specific language and application environment, whereas WAFs can be used in front of almost any application. Some vendors have both WAF and RASP module offerings, and an application can be protected by both a RASP module and a WAF.

Our attacker, Molly, may attempt to come right in the front door as a normal user and find some problem with our application that allows her to steal all of our customer data. If we’ve accidentally left a way for her to fool our application into giving up the data, a WAF or RASP module might be able to block it.

Note that one of the most common methods of attacking web applications is the use of stolen or weak credentials. If Molly has a set of administrative credentials providing access to all data, a WAF or RASP module will not defend against this type of attack, which is why identity and access management is so important! However, I still recommend the use of SaaS or host-based WAFs and RASP modules for web applications on cloud, and even APIs can get some limited benefits from parameter checking.

Note

A cloud WAF service will be able to see all of the content in your communications. This should not be an issue for most organizations, with the proper legal agreements in place and when dealing with a reputable WAF company, but may be a problem for some high security or highly regulated organizations.

Anti-DDoS

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks are a huge problem on the Internet for many companies. If you receive too many fake requests or too much useless traffic, you can’t provide services to the legitimate requesters.

The other controls we’ve discussed are generally recommended; you should rarely accept the risk of doing without them. However, you need to check your threat model before investing too much in anti-DDoS measures. Put more bluntly, is anyone going to care enough to knock you off the Internet, and how big of a problem is it for you if they do? Unlike a data breach where you can never remove all copies of the stolen data, a DDoS attack will eventually end.

If you’re running any sort of online retailing application, or a large corporation’s web presence, or any other application such as a game service where downtime can obviously cost you money or cause embarrassment, you’re certainly a target for extortionists who will demand money in return for stopping an attack. If you’re hosting any content that’s controversial, you’re likewise an obvious target. Note that the bar to entry is very low; there are “testing” services available cheaply that can easily generate too much traffic for your site to handle, so it only takes one individual with a few hundred dollars to ruin your day.

However, if you’re running a back-office application where some downtime will not obviously limit your business or embarrass you, you may need very little in the way of anti-DDoS measures. If this is the case, make sure that you clearly document that you’re accepting the risk of DDoS attacks and get agreement from all of your stakeholders! While foregoing anti-DDOS (or having very limited anti-DDOS protections) may be the correct choice in some cases, it should not be the default choice and it’s not a choice to be taken lightly.

Anti-DDoS measures can be a “blinky box” or virtual appliance, but in most cases today, anti-DDoS is delivered in a SaaS model. This is largely due to economies of scale; anti-DDoS services often need a large internet “pipe” and lot of compute power to sort through all of the incoming requests and filter out the fake ones, but this capacity is needed only occasionally for each customer.

If you choose to use an anti-DDoS service, I recommend you use a cloud provider. You will need to have a method to route all of your traffic through that provider, tune your rules, and practice an attack scenario. There are third-party providers, and some IaaS providers also provide anti-DDOS as a service.

Intrusion detection and prevention systems

In a traditional IT world, an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) is often a “blinky box” that generates alerts when the traffic that passes through it matches one of its rules. An Intrusion Prevention System (IPS) will block the traffic in addition to alerting. An IDS/IPS agent may also be deployed to each host, configured centrally, to detect and block malicious traffic coming to that host. IDS and IPS are almost always offered in the same product, and are generally treated as the same control. If you are more certain that traffic is malicious, or your risk tolerance is lower, you will configure a particular rule to block rather than just alert.

An IDS/IPS rule may be signature based, and trigger on the content of the communication. For example, the IDS/IPS may trigger on seeing a particular stream of bytes included in a piece of malware. For this to work, the IDS/IPS needs to be able to see the clear text communications, which it often does by performing a sanctioned “man-in-the-middle” attack to decrypt all of the communications. This is a valid model, but it makes the IDS/IPS a valuable target for attackers. Not only can an attacker on the IDS/IPS watch all traffic going through it, but an attacker that obtains the signing certificates or private keys used by the IDS/IPS may be able to carry out attacks elsewhere on the network.

IDS/IPS rules may also be based on behavior, triggering only on the metadata of the network traffic. For example, a system that is initiating connections to a lot of network ports (port scanning) may be owned by an attacker. Such rules can be useful even when traffic is encrypted end-to-end so that the IDS/IPS cannot look inside it.

For this control, there is not a lot of difference between traditional deployments and cloud deployments. In the “blinky box” model, the box will often be a virtual appliance instead of a physical box in cloud environments. However, all traffic must flow through that virtual appliance in order for it to detect or prevent attacks. This can sometimes lead to scalability concerns, because virtual appliances often cannot process as much traffic as a dedicated box with hardware optimizations. It can also be difficult to position an infrastructure IDS/IPS solution so that all traffic flows through it, If you succeed at this, you may still add considerable latency as traffic takes extra hops to get to the IDS/IPS and then to the back-end system, instead of directly from the end user to the back end system.

Host-based IDS/IPS solutions in cloud environments also function similarly to their traditional counterparts, although they can often be baked into virtual machine images or container layers more easily than they can be rolled out to already installed operating systems. Incorporating them into images can be an easier model to use in cloud environments, because the systems being protected may be spread around the world.

Although there is some difference of opinion on the matter, an IDS/IPS might not add much value as part of a perimeter control if a Web Application Firewall is used correctly. This is because the Web Application Firewall prevents the IDS/IPS from seeing most attacks. However, an IDS/IPS can be very useful for detecting an attacker who is already through the perimeter. If our attacker Molly attempts to perform reconnaissance via a port scan from one of our cloud instances, an internal IDS/IPS may be able to alert us to the threat.

If you have already correctly implemented and tested the other controls above and want additional protection, I recommend baking a host-based IDS/IPS agent into each of your system images and having the agents report to a central logging server for analysis.

Egress Filtering

You’ve implemented all of the controls above and you want to tighten down the environment even further. Great! You absolutely have to expect and block attacks from the outside. However, it’s possible someone will take control of one of your components. For that reasons, it is also be a good idea to limit outbound, or “egress”, communications from components that you should be able to trust. Some reasons to perform egress filtering include:

-

An attacker may want to steal a copy of your data, by transferring it to some place outside your control. This is termed “data exfiltration”. Egress filtering can help reduce or slow data exfiltration in the event of a successful attack. However, in addition to limiting “normal” connections, you must take care also to block other avenues of data exfiltration such as DNS tunnelling, ICMP tunnelling, and hijacking of existing allowed inbound connections. For example, if an attacker compromises a web or application server, that system will happily serve up the data, bypassing any egress controls). This is primarily useful when you have a large volume of data to protect; smaller amounts of data could be written down or screen-shotted9.

-

Egress filtering can also help prevent “watering hole” attacks, although these are less common against servers than against end users. For example, your policy may require that all components are updated from an internal trusted source. However, due to human error, a service might be configured to make unauthorized calls out to an update server that could be compromised by an attacker to provide it with a malicious update. In this case, egress filtering would be a second line of defense against that attack by making it impossible for the misconfigured component to reach out to the update server.

Tip

Egress filtering is required for some environments: for example, the NIST 800-53 controls list the requirement under SC-7(5) for moderate environments and as an optional enhancement in SC-5 to prevent your own systems from participating in a DDoS attack against someone else. Egress filtering controls can include simple outbound port restrictions, outbound IP whitelists and port restrictions, and even an authenticating proxy that allows only the traffic that the specific component requires.

Outbound port restrictions are the simplest way to limit traffic, but also the least effective. For example, you may decide that there’s no good reason for any part of your cloud deployment to be talking to anything else other than over the default HTTPS port, tcp/443, but that you can allow tcp/443 to any destination. That may prevent some types of malware from calling home, but is a very weak control overall. In a cloud deployment, port-based egress filtering can be done via security groups or network ACLs, analogous to the way it’s done for the ingress controls discussed earlier.

Like inbound IP whitelisting, outbound IP whitelisting is becoming less and less feasible with the rise of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) and Global Server Load Balancers (GSLBs). While these are very important tools for making content and services available more quickly and reliably, they render IP-based controls ineffective because the content may reside at many different IP addresses around the world that change rapidly.

There are two general ways to implement effective egress controls. The first is via an “explicit proxy”, enforced by configuration each component not to communicate directly with the outside world, but instead to ask the proxy to make the connection on its behalf. Most operating systems have the ability to set an explicit proxy; for example, on Linux, you can set the HTTP_PROXY and HTTPS_PROXY environment variables, and on Windows you can change the proxy settings in the control panel. Many applications that run on the operating system will use this proxy if it’s set, but not all.

The second way to accomplish this is via a “transparent proxy”. In this case, something on the network (such as an intelligent router) sends the traffic to the proxy. The proxy then evaluates the request (for example, to see whether it’s going to a whitelisted set of URLs) and makes the request on behalf of the backend system if it meets the validation requirements. Some newer technologies, such as Istio, can transparently proxy only allowed traffic within a Kubernetes cluster.

While HTTP is certainly the most common protocol to proxy, there are proxies available for other protocols as well. Note that for HTTPS connections, the source should validate that the destination is the correct system by means of an x509 certificate.10 This validation will fail unless the transparent proxy has the ability to impersonate any site, which is risky.

Warning

As with IDS/IPS, proxies themselves become an attractive target for attackers. Anyone with access to the proxy can perform a man-in-the-middle attack and listen to or modify any data flowing through it, which can easily compromise the entire application. In addition, if the proxy has a signing certificate trusted by the components in your cloud deployment, an attacker who gets that signing certificate can impersonate any site until the certificate is removed from the trust store of all components. If you choose to implement a proxy for egress traffic, make sure that it is protected at least as well as the other components of the system.

In general, I recommend only limited egress controls (such as port level controls via network ACLs and security groups), unless slowing data exfiltration in the event of a breach is a primary concern. If you have large volumes of valuable data and want to give yourself additional time to respond, strict egress controls may help. In this example, I’ve shown a combination egress proxy and Data Loss Prevention system, but this may also be performed by an as-a-service offering.

Data Loss Prevention

Data Loss Prevention, or DLP, watches for sensitive data that is either improperly stored in the environment or leaving the environment. Cloud providers may offer DLP services as an add-on feature to other services, or you may choose to implement DLP controls yourself in your environment.

If implemented in an IaaS/PaaS cloud environment, DLP may be implemented as part of egress controls. For example, the web proxy for outbound communications may be configured with DLP technology to alert an administrator or block an outbound communication if it contains credit card information. DLP may also be integrated into an IDS/IPS device or as a standalone virtual appliance that traffic flows through and is decrypted and inspected.

A SaaS environment may integrate DLP directly to prevent certain data types from being stored at all or to automatically tag such information. This type of DLP, if available, may be considerably more effective than egress-based DLP controls, but is highly specific to the SaaS service.

If you have sensitive information such as payment information or personal health data, you may need to incorporate DLP controls into your cloud environment. For the majority of cloud deployments, however, DLP may not be required. Unless you are willing to carefully configure the solution, follow up on alerts, and deal with false positives, DLP will only provide you with a false sense of security.

Summary

Do you know what our attacker, Molly, actually does in a lot of cases? She will point scanning tools such as Nmap, Nessus, or Burp Suite at every system she can find. She’ll find some command injection attack, or MySQL instance with default credentials, or vulnerable SMTP server, or something else stupid that has been missed despite the all of the vulnerability and asset management processes in place. She’ll get in via default credentials, an unpatched vulnerability, or similar problem and compromise the rest of the system from there.

At that point several things have probably already gone wrong: your asset management process has a leak, or items vulnerable to attack were turned on by accident, or your vulnerability management process missed a vulnerable component or configuration, or someone set a stupid password despite policies and controls to avoid it. The network controls may be either your first or last line of defense in those cases, but don’t depend on them as your only line of defense.

As examples, the perimeter might be able to stop someone from getting in to exploit these failures in other processes, or at least give you a chance to notice an attack in progress and respond. TLS may prevent an attacker with a small foothold from sniffing credentials or data. The WAF may jump in front of an injection attack that would have tricked your application to giving out all of your data through the front door. Security groups may help protect you by saying, “Look, this is a virtual machine or container for component X. It needs to let in only specific traffic for component X, and also maybe some administrative stuff. Also, the administrative stuff should come only from over here, not from a kid in his parents’ basement.”

For those reasons, network controls are an important layer of protection for your cloud environment. While a lot of technically complicated controls are available, it’s important to prioritize them to get the best protection for your efforts. I recommend the to go through the following steps in the order listed:

-

Draw a diagram of your application, with trust boundaries.

-

Make sure that your inbound connections use TLS, and that all component-to-component communications that may go across the wire use TLS with authentication.

-

Enforce a perimeter and internal segmentation, and provide a secure way for your administrators to manage the systems via a bastion host, a VPN, or another method offered by your cloud provider.

-

Set up a web application firewall, RASP, and/or IDS/IPS, if appropriate.

-

Set up DDoS protection if appropriate.

-

Set up at least limited egress (outbound) filtering.

-

Check all of these configurations regularly to make sure they’re still correct and useful. Some cloud providers provide services to check configurations, including network configurations. For example, you could have an automated check to make sure all of your systems’ security groups are configured to only permit ssh access from specific IPs.

It should be somewhat obvious that none of the controls presented here are particularly effective in a “check-the-box” mode, where you deploy them and then do not take care to tune them, update them, and investigate what they’re finding. It’s very important not only to set up these controls, but also to continually review logs to detect intrusion attempts or attackers already in the network trying to move laterally. This leads us into the next chapter.

1 If you think about it, they should really be named “TCP/UDP whitelists” if they include port information.

2 If the protocol being proxied is IP, it’s called “Network Address Translation” and “routing” instead of proxying, but the concept is the same!

3 If you think about it, the problem of “we ran out of numbers” is a really silly reason to have to put up with these headaches.

4 A ciphersuite is a set of encryption and signing algorithms that are used to protect the TLS connection. Although there are a lot of important details that are of interest to cryptographers, in general you just need to know which ones are currently considered safe and limit your connections to use those. In some cases, you may need to accept less secure ciphersuites if you don’t control the other end of the connection-for example, if you need to allow out of date browsers to connect.

5 Many cloud providers distinguish between security groups, which apply to a single system, and network access control lists, which apply to the traffic entering and exiting the subnet. However, Microsoft Azure uses Network Security Groups that can apply to both systems and subnets.

6 A Remote Access Trojan is a type of malware used to control an unsuspecting user’s system. For example, an administrator may browse to a malicious web site, which silently installs a RAT. Late at night when the administrator is asleep, an attacker may take control of the administrator’s workstation and use open sessions or cached credentials to attack the system.

7 Internet users around the world became alerted to this potential through Edward Snowden’s explosive revelations.

8 Google doesn’t either.

9 This type of copying is often called the “analog hole” and is almost impossible to block

10 Don’t turn off certificate checking, except as a very temporary measure for troubleshooting connection errors. TLS provides very limited protection if certificate checking is turned off.