Chapter 2. Data Asset Management and Protection

Now that Chapter 1 has given you some idea of where your provider’s responsibility ends and yours begins, your first step is to figure out where your data is — or is going to be — and how you’re going to protect it. There is often a lot of confusion about the term “asset management”. What exactly are our assets, and what do we need to do to manage them? The obvious (and unhelpful) answer is that assets are anything valuable that you have. Let’s start to home in on the details.

In this book, I’ve broken up asset management into “data asset management” and “cloud asset management”. Data assets are the important information you have, such as customer names and addresses, credit card information, bank account information, or credentials to access such data. Cloud assets are the things you have that store and process your data — compute resources such as servers or containers, storage such as object stores or block storage, and platform instances such as databases or queues. Managing these assets is covered in the next chapter. While you can start with either data assets or cloud assets, and may need to go back and forth a bit to get a full picture, I find it easier to start with data assets.

The theory of managing data assets in the cloud is no different than on-premises, but in practice there are some cloud technologies that can help.

Data Identification and Classification

If you’ve created at least a “back-of-the-napkin” diagram and threat model in the first chapter, you’ll have some idea of what your important data is, as well as the threat actors you have to worry about and what they might be after. Let’s look at different ways the threat actors may attack your data.

One of the more popular information security models is the “CIA triad” — confidentiality, integrity, and availability. A threat actor trying to breach your data confidentiality wants to steal it, usually to sell it for money or embarrass you. A threat actor trying to breach your data integrity wants to change your data, such as by altering a bank balance. (Note that this can be effective even if the attacker cannot read the bank balances; I’d be happy to have my bank balance be a copy of Bill Gates’s even if I don’t know what that value is.) A threat actor trying to breach your data availability wants to take you offline for fun or profit, or use ransomware to encrypt your files1.

Most of us have limited resources and must prioritize our efforts.2 A data classification system can assist with this, but resist the urge to make it more complicated than absolutely necessary.

Example Data Classification Levels

Every organization is different, but the following rules may be a good, simple starting point for assessing the value of your data, and therefore the risk of having it breached.

- Low

-

While the information in this category may or may not be intended for public release, if it were released publicly the impact to the organization would be very low or negligible. Some examples might include:

-

Your servers’ public IP addresses

-

Application log data without any personal data, secrets, or value to attackers

-

Software installation materials without any secrets or other items of value to attackers

-

- Moderate

-

This information should not be disclosed outside of the organization without the proper nondisclosure agreements. In many cases this type of data should be disclosed only on a need-to-know basis within the organization, especially in larger organizations. In most organizations, the majority of information will fall into this category. Some examples:

-

Detailed information on how your information systems are designed, which may be useful to an attacker

-

Information on your personnel, which could provide information to attackers for phishing or pretexting attacks

-

Routine financial information, such as purchase orders or travel reimbursements, which might be used (for example) to infer that an acquisition was likely

-

- High

-

This information is vital to the organization, and disclosure could cause significant harm. There should be very tightly controlled access and multiple safeguards on access to this data. In some organizations, this type of data is called “crown jewels”. Some examples might be:

-

Information about about future strategy or financial information, which would provide a significant advantage to competitors

-

Trade secrets, such as the recipe for your popular soft drink or fried chicken

-

Secrets that provide the “keys to the kingdom”, such as full access credentials to your cloud infrastructure

-

Sensitive information placed into your hands for safekeeping, such as your customers’ financial data

-

Any other information where a breach might be newsworthy

-

Note that laws and industry rules may effectively dictate how you classify some information. For example, the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has many different requirements for personal data, so in this example you may choose to classify all personal data as “moderate” and protect it accordingly. PCI requirements would probably dictate that you classify cardholder data as “high” if you have it in your environment.

Also, note that there are cloud services that can help with data classification and protection. As examples, Amazon Macie can help you find sensitive data in S3 buckets, and Google Cloud Data Loss Prevention API that can help you classify or mask certain types of sensitive data.

Whatever data classification system you use, write down a definition of each classification level and some examples of each, and make sure that everyone generating, collecting, or protecting data understands the classification system.

Relevant Industry or Regulatory Requirements

This is is a book on security, not compliance. As a gross over-generalization, compliance is about proving your security to a third party — and that’s much easier to accomplish if you have actually secured your systems and data. The information in this book will help you with being secure, but there will be additional compliance work and documentation after you’ve secured your systems.

However, some compliance requirements may inform your security design. So even at this early stage, it’s important to make note of a few industry or regulatory requirements:

- EU GDPR

-

This regulation may apply to the personal data of any European Union or European Economic Area citizen, regardless of where in the world the data is. GDPR requires you to catalog, protect, and audit access to “any information relating to an identifiable person who can be directly or indirectly identified in particular by reference to an identifier.” The techniques in this chapter may help you meet some GDPR requirements, but you must make sure that you include relevant personal data as part of the data you’re protecting.

- US FISMA or FedRAMP

-

FISMA is per-agency, whereas FedRAMP certification may be used with multiple agencies, but both require you to classify your data and systems in accordance with FIPS 199 and other US government standards. If you’re in an area where you may need one of these certifications, you should use the FIPS 199 classification levels.

- US ITAR

-

If you are subject to ITAR regulations, in addition to your own controls, you will need to choose cloud services that support ITAR. Such services are available from some cloud providers and are managed only by US personnel.

- Global PCI-DSS

-

If you’re handling credit card information, there are specific controls that you have to put in place, and there are certain types of data you’re not allowed to store.

- US HIPAA

-

If you’re in the US and dealing with any PHI (protected health information), you’ll need to include that information in your list and protect it, which often involves encryption.

There are many other regulatory and industry requirements around the world, such as MTCS (Singapore), G-Cloud (UK), and IRAP (Australia). If you think you may be subject to any of these, review the types of data they are designed to protect so that you can ensure that you catalog and protect that data accordingly.

Data Asset Management in Cloud

Most of the preceding information is good general practice and not specific to cloud environments. However, cloud providers are in a unique situation to help you identify and classify your data. For starters, they will be able to tell you everywhere you are storing data, because they want to charge you for the storage!

In addition, use of cloud services brings some level of standardization by design. In many cases, your persistent data in the cloud is probably going to be in one of the cloud services that store data, such as object storage, file storage, block storage, a cloud database, or a cloud message queue — all of which show up in your cloud asset inventory, rather than being spread across thousands of different disks attached to many different physical servers.

Your cloud provider gives you the tools to inventory these storage locations, as well as to access them (in a carefully controlled manner) to determine what types of data are stored there. There are also cloud services that will look at all of your storage locations and automatically attempt to classify where your important data is. You can then use this information to tag your cloud assets that store data.

When you’re identifying your important data, don’t forget about passwords, API keys, and other secrets that can be used to read or modify that data! We’ll talk about the best way to secure secrets in Chapter 4, but you need to know exactly where they are.

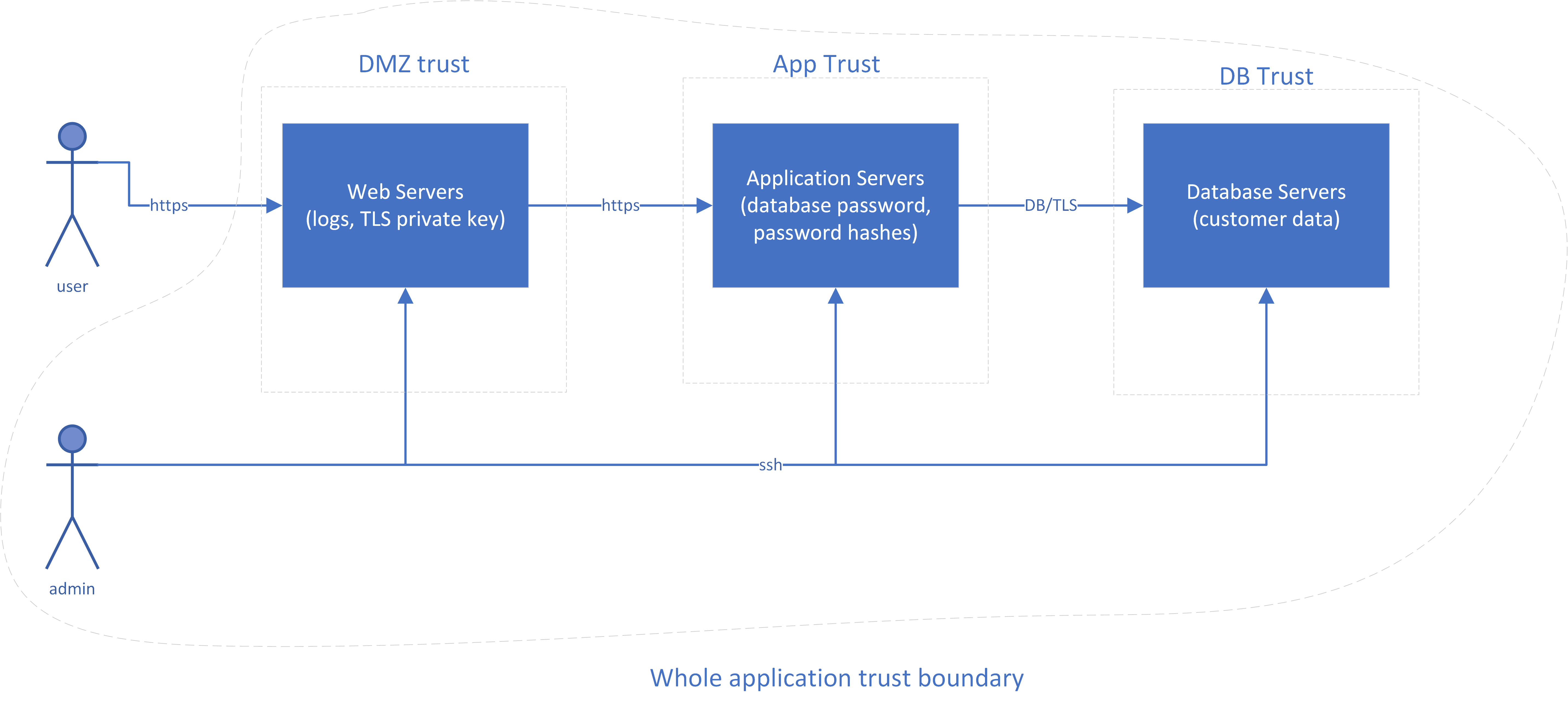

If we look at our sample application, there’s obviously customer data in the database. However, where else do you have important assets?

-

The web servers have log data that may be used to identify your customers.

-

Your web server has a private key for a TLS certificate; with that and a little DNS or BGP hijacking, anyone could pretend to be your site and steal your customers’ passwords as they try to log in.

-

Do you keep a list of password hashes to verify your customers? Hopefully you’re using some sort of federated ID system as described in Chapter 4, but if not, the password hashes are a nice target3 for attackers.

-

Your application server needs a password or API key to access the database. With this password, an attacker could read or modify everything in the database that the application can.

Even in this really simple application, there are a lot of non-obvious things you need to protect. Figure 2-1 repeats Figure 1-7 from the previous chapter, adding the data assets in the boxes.

Figure 2-1. Sample Application Diagram with Data Assets

Tagging Cloud Resources

Most cloud providers, as well as container management systems such as Kubernetes, have the concept of tags. A tag is usually a combination of a name (or “key”) and a value. These tags can be used for lots of purposes, from categorizing resources in an inventory, to making access decisions, to choosing what to alert on. For example, you might have a key of “PII-data” and a value of “Yes” for anything that contains personally identifiable information, or you might use a key of “Datatype” and a value of “PII”.

The problem is clear: if everyone in your organization uses different tags, they won’t be very useful! Create a list of tags with explanations for when they must be used, use these same tags across multiple cloud providers, and require them to be applied by automation when resources are created. Even if one of your cloud providers doesn’t explicitly support the use of tags, there are often other description fields that may be used to hold tags in easy-to-parse formats such as JSON.

Tags are free to use, so there’s really no concern with creating a lot of them, although cloud providers do impose limits on how many tags a resource can have (usually between 15 and 64 tags per resource). If you don’t need to use them for categorizing or making decisions later, they’re easily ignored.

Some cloud providers even offer automation to check whether tags are properly applied to resources, so that you can catch untagged or mistagged resources early and correct them. For example, if you have a rule that every asset must be tagged with the maximum data classification allowed on that asset, then you can run automated scans to find any resources where the tag is missing or where the value isn’t one of the classification levels you have decided upon.

Although all of the major providers support tags in some fashion, as of this writing there isn’t full coverage of all services on these providers. For example, you may be able to tag virtual machines you create, but not databases. Where tags are not available, you’ll need to do things the old fashioned way, with a manual list of instances of those services.

| Infrastructure | Feature name |

|---|---|

Amazon Web Services |

Tags |

Microsoft Azure |

Tags |

Google Compute Platform |

Labels and Network Tags |

IBM Cloud |

Tags |

Kubernetes |

Labels |

We will talk more about tagging resources in Chapter 3, but for now, jot down some data-related tags that may apply to your different cloud resources, such as “dataclass:low”, “dataclass:moderate”, “dataclass:high”, or “regulatory:gdpr”.

Protecting Data in the Cloud

Many of the data protection techniques discussed in this section may also be applied on-premises, but many cloud providers give you easy, standardized, and less expensive ways to protect your data.

Tokenization

Why store the data when you can store something that functions similarly to the data but is useless to an attacker? Tokenization, which is most often used with credit card numbers, replaces a piece of sensitive data with a token (usually randomly generated). It has the benefit that the token generally has the same characteristics (such as being 16 numbers) as the original data, so underlying systems that are built to take that data don’t need to be modified. Only one place (a “token service”) knows the actual sensitive data. Tokenization can be used on its own or in conjunction with encryption.

Examples include cloud services that work with your browser to tokenize sensitive data before sending it, and cloud services that sit in between the browser and the application to tokenize sensitive data before it reaches the application.

Encryption

Encryption is the silver bullet of the data protection world; we want to “encrypt all the things”. Unfortunately, it’s a little more complicated than that. Data can be in three states:

-

In motion (being transmitted across a network)

-

In use (currently being processed in a computer’s CPU or held in RAM)

-

At rest (on persistent storage, such as a disk)

Encryption of data in motion is an essential control, and is discussed in detail later in Chapter 6. In this chapter, we’ll discuss the other two states.

Tip

More bits are not always necessary (or even useful). For example, AES-128 meets US Federal Government standards as of this writing and is often faster than AES-256, although quantum computers may eventually pose a threat to AES-128. Also, a hash algorithm like SHA-512 offers no additional protection if the hash is truncated later to a shorter length.

Encryption of data in use

As of this writing, encryption of data “in use” is still relatively new and is targeted primarily at very high security environments. It requires support in the hardware platform, and must also be exposed by the cloud provider. The most common implementation is to encrypt process memory so that even a privileged user (or malware running as a privileged user) cannot read it, and the processor can read it only when that specific process is running.4 If you are in a very high security environment and your threat model includes protecting data in memory from a privileged user, you should seek out a platform that supports memory encryption; it goes by brand names such as Intel SGX, AMD SME, or IBM Z Pervasive Encryption.

Encryption of data at rest

Encryption of data at rest can be the most complicated to implement correctly. The problem is not in encrypting the data; there are many libraries to do this. The problem is that once you’ve encrypted the data, you now have an encryption key that can be used to access it. Where do many people put this? Right next to the data! Imagine locking a door and then hanging the key on a hook next to it helpfully labeled “Key”. To have real security (instead of just ticking a checkbox indicating that you’ve encrypted data), you must have proper key management. Fortunately, there are cloud services to help.

Tip

Encrypted data can’t be effectively compressed. If you want to make use of compression, compress the data before encrypting it.

In traditional on-premises environments with high security requirements, you would purchase a Hardware Security Module (HSM) to hold your encryption keys, usually in the form of an expansion card or a module accessed over the network. An HSM has significant logical and physical protections against unauthorized access. With most systems, anyone with physical access can easily get access, but an HSM has sensors to wipe out the data as soon as someone tries to take it apart, scan it with X-Rays, fiddle with its power source, or look threateningly in its general direction. HSMs are expensive, and so are not feasible for most deployments.

However, in cloud environments, advanced technologies such as Hardware Security Modules and encryption key management systems are now within reach of projects with modest budgets.

Some cloud providers have an option to rent a dedicated HSM for your environment. While this may be required for the highest-security environments, a dedicated HSM is still expensive in a cloud environment. However, a Key Management Service (KMS) is a multitenant service that uses an HSM on the back end to keep keys safe. You do have to trust both the HSM and the KMS (instead of just the HSM), which adds a little additional risk. However, compared to performing your own key management (often incorrectly), a KMS provides excellent security at zero or very low cost. You can have the benefits of proper key management in projects with more modest security budgets.

Table 2-0 lists the “rent-a-dedicated-HSM” and Key Management Services on the major cloud providers, as of this writing.

| Provider | Dedicated HSM option | Key Management Service |

|---|---|---|

Amazon Web Services |

CloudHSM |

Amazon KMS |

Microsoft Azure |

--- |

Key Vault (Software Keys) |

Google Compute Platform |

--- |

Cloud KMS |

IBM Cloud |

Cloud HSM |

Key Protect |

So how do you actually use a KMS correctly? This is where things get a little complicated.

Key Management

The simplest approach to key management is to generate a key, encrypt the data with that key, stuff the key into the KMS, and then write the encrypted data to disk along with a note as to which key was used to encrypt it. There are two main problems with this approach:

-

It puts a lot of load on the poor KMS. There are good reasons for wanting a different key for every file, so a KMS with a lot of customers would have to store billions or trillions of keys with near instantaneous retrieval.

-

If you want to securely erase the data, you have to trust the KMS to irrevocably erase the key when you’re done with it, and not leave any backup copies lying around. Alternatively, you have to overwrite5 all of the encrypted data, which can take a while.

We often don’t want to wait for hours or days to overwrite a lot of data. It’s better if you have the option to quickly and securely erase data objects in two ways: by deleting a key at the KMS, which may effectively erase a lot of different objects at once, or by deleting a key where the data is actually stored, to delete a single data object. For these reasons, you typically have two levels of keys: a Key Encryption Key and a Data Encryption Key. As the names suggest, the key encryption key is used to encrypt (or “wrap”) data encryption keys, and the wrapped keys are stored right next to the data. The key encryption key usually stays in the Key Management Service and never comes out, for safety. The wrapped data encryption keys are sent to the HSM for unwrapping when needed, and then the unwrapped keys used to encrypt or decrypt the data. You never write down the unwrapped keys. When you’re done with the current encryption or decryption operation, you forget about them6.

The use of keys is easier to understand with a real-world analogy. Imagine you are selling your house (which contains all of your data), and you provide a key to your realtor to unlock your door. This house key is like a data encryption key; it can be used to directly access your house (data). The realtor will place this key into a key box on your door, and protect it with a code provided by the realtor service. This code is like the key encryption key, and the realtor service that hands out codes is like the Key Management Service. In this mildly strained analogy, you actually take the key box to the Key Management Service, and it gives you a copy of the key inside with the agreement that won’t make a copy of it (write it to disk) and you’ll melt (forget) that copy when finished with it. You never actually see the code that opens the box.

The end result is that when you walk up to the house (data), you know the data key’s right there, but it can’t be opened without another key or password. Of course, in the real world, a hammer and a little time would get the key out of the box, or would allow you to break a window and not need the key. The cryptographic equivalent of the hammer is guessing the key or password used to protect the data key. This is usually by trying all of the possibilities (“brute force”) or for passwords trying many common passwords (a “dictionary attack”). If the encryption algorithm and the implementation of that algorithm are correct, the expected time for the “hammer” to get into the box is longer than the lifetime of the universe.

Server-side and Client-side Encryption

The great news is that you usually don’t have to do most of this key management yourself! For most cloud providers, if you’re using their storage and their KMS, and you turn on KMS encryption for your storage instances, the storage service will automatically create data encryption keys, wrap them using a key encryption key that you can manage in the KMS, and store the wrapped keys along with the data. You can still manage the keys in the KMS, but you do not have to ask the KMS to wrap or unwrap them, or perform operations with the data encryption keys. Some providers call this “server-side encryption”.

Because the multi-tenant storage service does have the ability to decrypt your data, an error in that storage service could potentially allow an unauthorized user to ask the storage service to decrypt your data. For this reason, having the storage service perform the encryption/decryption is not _quite _as secure as doing the decryption in your own instance — if you implement it correctly, using well known libraries and processes. This is often called “client-side encryption”. However, unless you have a very low risk tolerance (and a budget to match that low risk tolerance), I recommend that you use well-tested cloud services and allow them to handle the encryption/decryption for you.

Note that when using client-side encryption, the server does not have the ability to read the encrypted data because it doesn’t have the keys. This means no server-side searches, calculation, indexing, malware scans, or other higher value tasks can be performed. Homomorphic encryption may make it feasible for operations such as addition to be performed correctly on encrypted data without decrypting the data, but as of this writing it’s too slow to be practical for a while.

Warning

Unless you have devoted most of your distinguished career to cryptography, do not attempt to create or implement your own crypto systems. Even when performing the encryption/decryption yourself, use only well-tested implementations of secure algorithms, such as those recommended in NIST SP 800-131A Rev 1 or later.

Cryptographic erasure

It’s actually difficult to reliably destroy large amounts of data7. It takes a long time to overwrite it completely, and even then there may be other copies of the data sitting around. We can solve this by “cryptographic erase”; we never write the cleartext data on the disk, only an encrypted version.

When we want to make data unrecoverable, we can wipe or revoke access to the key encryption key in the KMS, which will make all of the data encryption keys “wrapped” with that key encryption key useless, wherever they are in the world. We can also wipe a specific piece of data by wiping out just its wrapped data encryption key, so a multi-terabyte file can be effectively made unrecoverable by overwriting a 256-bit key.

How encryption foils different types of attacks

As we’ve discussed, encryption of data at rest can protect data from attackers by limiting their choices; the data is available in the clear only in a few places, depending on where the encryption is being performed. Let’s look at some typical successful attackers and how much our encryption choices will annoy them.

Attacker gains unauthorized access to physical media

Attackers might successfully steal disks from the data center or the dumpster, or steal tapes in transit.

Encryption at rest protects data on the physical media, so that an attacker can’t make use of the data even if they gain access to the media (such as by breaking a password). This is great news, although this type of attack typically isn’t a large risk given the physical controls and media controls most cloud providers practice. (It’s far more important for portable devices such as smartphones and laptops.) Encryption performed only to “check the box” will often only help to mitigate the threat of physical theft — and sometimes not even this threat, because this protection fails if you store unwrapped keys on the same media as the data.

Attacker gains unauthorized access to the platform or storage system

Perhaps you have an attacker or a rogue operator who is able to read and write your data in a database, block storage, file storage, or object storage instance.

If the storage system itself is responsible for performing the encryption, the attacker will often be able to trick the system into giving it the data, depending on the technical controls in place within the storage system. However, this will at least leave auditable tracks in a completely different system (the key management system), so it may be possible to limit an attack if key access the behavior looks unusual and anyone notices it quickly enough.

If the application only sends data that is already encrypted to the storage system, an attacker here only has access to a useless “bag of bits”. The attacker can make the data unavailable, but cannot compromise integrity or confidentiality.

As previously mentioned, you must weigh your trust in the storage system’s controls versus your trust and investment in your own controls. Generally speaking, the storage system’s owner has more to lose if there’s a breach than you do; it will hurt you, but it may well put the provider out of business.

Attacker gains unauthorized access to the hypervisor

Most cloud environments have multiple virtual machines (“guests”) running on top of a hypervisor, which runs on the physical hardware. A common concern is that an attacker on the same physical machine will be able to read or modify data from other guests on the same physical system.

If an attacker can read a guest’s memory, they may use a memory scan to find the data encryption keys and then use them to decrypt the data. This is significantly more difficult than just reading the data directly, and there’s a lot of benefit to making an attacker’s life difficult. However, it is often possible, so if this is a serious concern for you, consider using single-tenant hypervisors or bare metal systems, or a hardware technology that encrypts data in memory. If you look at the statistics available on data breaches, however, your security investment would probably be better spent elsewhere in most cases.

Attacker gains unauthorized access to the operating system

If an attacker gains unauthorized access to the operating system that your application is running on, there are two scenarios to consider:

-

The attacker has limited operating system access. At this point, the operating system controls are the only effective controls. Encryption at rest will not prevent access to the data if the attacker has access to the process or files holding the encryption keys, or access to the decrypted storage.

-

The attacker has full operating system access. Privilege escalation exploits are plentiful, so an attacker that gets limited operating system access can often end up with full privileges. Given enough time, and without the data-in-use protections discussed at the beginning of the chapter, the attacker can read process memory, retrieve any encryption keys used by higher layers, and access all of the data accessible to that process.

Attacker gains unauthorized access to the application

If an attacker gains unauthorized access to the application, all bets are off, because the application must be able to read the data in order to function. However, proper use of encryption and other access controls may keep the attacker from being able to read any data other than the data the compromised application has access to.

In general, if the “bottom” of the stack is the physical hardware and the “top” of the stack is the application, you get protection against more types of breaches by having the encryption happen as close to the “top” of the stack as possible. However, the tradeoff is often having to do more work yourself, and you need to take into account the likelihood of breaches at the lower layers.

In many cases, a lot more effort has gone into securing those lower layers than you will invest in securing your application. Unless your application is at least as secure as the layers below it, you actually increase risk instead of reducing it if you move the encryption work up to the application itself. An application compromise will forfeit the whole game. For this reason, I recommend making use of the encryption tools available at the lower layers (such as encrypted databases, encrypted block/file storage, etc.) for most workloads. I recommend application level encryption only for highly sensitive data, due to the additional effort required versus the minimal reduction in risk it provides.

Summary

When planning your cloud strategy, you need to figure out what data you have, both the obvious and non-obvious parts. Classify each type of data by the impact to you if it’s read, modified, or deleted by an attacker. Agree organization-wide on which tags to use in a “tag dictionary”, and use the tagging features of your cloud provider to tag resources that contain data.

If possible, you should decide on an encryption strategy before you create storage instances, because it can be difficult to change later. In most cases, you should use your cloud provider’s key management system to manage the encryption keys, and you should use built-in encryption in the storage services if available, accepting the risk that the storage service may be compromised. If you do need to encrypt the data yourself prior to storing it, use only well-tested implementations of secure algorithms.

Carefully control the users and systems that have access to the keys, and set up alerts to let you know when the keys are being accessed in any unusual fashion. This will provide an additional layer of protection in addition to the access controls on the storage instances, and can also provide you with an easy way to cryptographically erase the information when you’re done with it.

One of the concerns with encryption is that it can reduce performance, due to the extra processing time required to encrypt and decrypt the data. Fortunately, this is no longer as big of a concern; hardware is cheap, and all of the major chip makers have some form of hardware acceleration built into their CPUs. Performance concerns are rarely a good excuse for not encrypting data, but you can be certain only by testing with real world controls.

Another, more important concern around encryption is the availability of your data. If you cannot access the encryption keys, you cannot access your data. Ensure that you have some sort of “break the glass” process for getting access to the encryption keys, and make sure that it’s “noisy” and cannot be used without detection and alerting.

1 Arguably ransomware is both an availability and an integrity breach, because it uses unauthorized modifications of your data in order to make it unavailable.

2 If you have unlimited resources, please contact me!

3 Remember LinkedIn’s 6.5 million password hashes that were cracked, and then used to compromise other accounts where users used the same password as on LinkedIn?

4 Note that in-memory encryption protects data only from attacks from outside the process; if you manage to trick the process itself into doing something it shouldn’t, it can read the memory and divulge the data.

5 Despite a well-known paper from 1996 exploring the ability to recover data on a hard disk that’s been overwritten, it’s not practical today. Recovering overwritten data from SSDs is slightly more practical due to the way writes happen, but most SSDs have a “secure erase” feature to sanitize the entire drive; see a 2011 Usenix paper for more details.

6 This is an extremely simplified explanation. For a really deep discussion of all things cryptographic, see Bruce Schneier’s book Applied Cryptography.

7 Although paradoxically, it’s often easy to do by accident!