Chapter 3. Cloud Asset Management and Protection

At this point, you should have a good idea of what data you have, where it’s stored, and how you plan to protect it at rest. Now it’s time to look at other cloud assets and how to inventory and protect them.

As mentioned in Chapter 2, cloud providers maintain a list of which assets you have provisioned, because they want to be able to bill you! They also provide APIs to view this list, and sometimes have specialized applications to help you with inventory and asset management.

Warning

In general, your cloud provider will know only about assets you provision via their portal or APIs. For example, if you provision a virtual machine and then manually create containers on it, the cloud provider will have no way of knowing about the containers.

Cloud infrastructure and services are often inexpensive and easy to provision, which can quickly lead to a huge number of assets strewn all over the world and forgotten. Each of these forgotten assets is like a ticking time bomb, waiting to explode into a security incident.

Differences from Traditional IT

One important difference with cloud asset management and protection is that you generally don’t have to worry about physical assets or protection at all for your cloud environments! You can gleefully outsource asset tags, anti-tailgating, slab-to-slab barriers, placement of data center windows, cameras, and other physical security and physical asset tracking controls.

Another important difference lies in the IT group’s participation in the process of provisioning cloud assets. In a traditional IT environment, creating an asset such as a server is often difficult and time consuming. It usually requires going to a centralized IT group, who usually follow a detailed provisioning process and will maintain a list of assets in a database or a spreadsheet. There is a natural barrier to creating shadow IT (IT resources that are hidden or not officially approved for use), because IT typically requires capital assets. In most organizations, large capital expenditures are carefully controlled.

One important benefit of cloud computing is replacing these large capital expenditures with monthly expenses, and offloading the capacity planning to an IaaS provider. This is great, but it also means that it’s more difficult for the IT and finance areas of the business to be effective gatekeepers for IT resources. Anyone in any area of the business can easily provision a huge number of IT resources with only a credit card (and sometimes not even that). This can quickly lead to asset management problems.

Prior to the cloud, most organizations had some amount of shadow IT. In the cloud era, this problem is often far worse—and it’s not just servers.

Types of Cloud Assets

Before we can effectively manage cloud assets, we need to understand what they are and their security-relevant characteristics. I find that creating clearly defined categories of assets helps to organize my thinking. For this reason, I have categorized cloud assets as compute, storage, and network, but you could choose different categories.

More types of cloud assets are created every day, and it’s likely that you will not have all of these types of assets. You also don’t need to track all of these assets in a single place. The important thing is to know about all assets that are relevant to your security.

If you are coming into an environment with a large number of existing cloud assets, keep in mind that you don’t have to have a 100% solution for asset management immediately. Concentrate on the assets that are the most security relevant to get immediate value, and then add additional types of assets to your inventory incrementally. For many organizations, the most security relevant assets will be a few types of data storage and compute assets.

As you read through the types of cloud assets, it may help to jot down notes of the types of assets that you already know about, and put stars next to the ones that are most relevant for security. Although this chapter is primarily around asset management, some of the security properties of these assets may inform the current or future designs of your cloud environment. In the second part of this chapter, I’ll share some ideas on how to inventory the cloud asset types you’ve identified here.

Tip

Many cloud assets are ephemeral, in that they are created and deleted fairly often. This can make asset management more difficult, and it may also make some popular methods of asset tracking ineffective, such as tracking by IP address.

Compute assets

Compute assets typically take data, process it, and do something with the results. For example, a very simple compute resource might take data from a database and send it to a web browser on request, or send it to a business partner, or combine it with data in another database.

These cloud asset categories are not completely distinct. Compute resources may also store data, particularly temporary data. With some types of regulated data, it may be necessary to ensure that you’re tracking every place that data could be, so don’t forget about temporary data storage.

Virtual Machines

Virtual Machines (VMs) are the most familiar cloud asset type. VMs run operating system and processes that perform business functions. VMs in cloud environments behave very similarly to their on-premises equivalents in many cases.

VMs always have an operating system, which includes a kernel as well as other “user space” programs shipped with the kernel by the operating system vendor. Some servers can perform all of their functions using only the software shipped as part of the operating system. However, most VMs have additional software installed, such as platform/middleware software and custom application code that your organization has written.

Because so many different components can be mixed together to make up a VM, we need to be careful about vulnerability management, access management, and configuration management for each of the different layers of a server. Successful attackers may get access to any data the VM has access to, as well as use that VM to attack the rest of your infrastructure or other people.

Some example inventory items to track for VMs:

-

The operating system name and version. Operating system vendors support versions with security fixes for only a limited amount of time, so it’s important to stay reasonably up-to-date and run a supported version of your OS.

-

The names and versions of any platform or middleware software. This may be software such as web servers, database servers, or queue managers. It’s important to track this software for vulnerability management purposes (in case security advisories are released for that software) as well as license management.

-

Any custom application code on the VM that your organization maintains.

-

The IP addresses of the VM and what Virtual Private Cloud network it’s in, if applicable.

-

The users allowed access to the operating system, and to the platform/middleware/application software if different.

Most of these are the same as on-premises VMs. However, cloud VMs generally only take a minute or two to create, which means that they can be created and deleted as needed. This is great for scaling up and down quickly to meet demand, but can make asset management more difficult. For this reason, you will probably need to use agents installed on your VMs or an inventory system from your cloud provider to collect all of the relevant information automatically.

In addition to tracking the VMs themselves (often called “instances”), you also need to track the “images” or templates that are copied to create new VMs. You don’t want new servers to come online with critical vulnerabilities, even if they are patched quickly after starting.

Some cloud providers provide “bare metal” systems in addition to VMs.1 These have the same security needs as VMs, but may also have firmware that occasionally needs to be updated.

Many cloud providers also provide “dedicated” VMs. These are created in the same way as regular VMs, except that the provider promises to not schedule any other customer’s VMs on the same physical systems with yours.

Bare metal machines and dedicated VMs are not subject to the risks described in “Virtual Machine Attacks”, but typically cost more. As with all security decisions, you must weigh the costs and benefits. In general, I do not require bare metal machines or dedicated VMs for additional security until the more common problems such as vulnerability management and access management are well under control.

Note that many of the following asset types can be seen as a deconstruction of a VM into smaller components provided “as-a-service”.

Containers

Like VMs, containers also run processes that perform business functions, such as a web server or custom application code. However, containers do not contain a full operating system like a VM. Containers use the kernel of the VM they are hosted on, and might not have any of the other software that comes with the operating system.

Containers can start up in under a second, which means that in many environments they are created and deleted almost constantly.

If your containers contain a full copy of the operating system and allow administrators to log in, they are basically miniature VMs. Although containers can be used in this “mini-VM” model, this isn’t the best way to use them. Your asset management strategy for containers depends partly upon how you are using them. We will look at two models, the “native” container model and the “mini-VM” model.

Native container model

In the native container model:

-

Containers should hold the bare minimum operating system components needed to perform their function.

-

Each container should perform only a single function (or “concern” in some documentation).

-

Containers are immutable, meaning that they don’t change over time. A container may make changes in some other component, such as writing data to a storage service, but that storage is maintained separately from the container itself.

-

Immutable containers remain a perfect copy of the code in the image during their lifetimes — they don’t update their own code, and nobody logs in to change it. Rather than updating containers, old containers are destroyed and new containers are created with updated code.

Native, immutable containers should not need to have administrators logging into them for routine maintenance, although you probably need some provision for obtaining emergency access occasionally. If container logins are not allowed in general, access management to the containers becomes less of a risk than with servers. Vulnerability and configuration management are still important risks, but the scope for a given container is much narrower than the scope for a server that might perform many different functions.

Native containers are generally created and destroyed much more often than VMs. That means it makes more sense to inventory the container images than the containers themselves, and just keep track of which image a container is copied from. A container image needs to be inventoried primarily in order to track the software and configurations in the image, so that the image may be updated with security fixes and new configurations as vulnerabilities are discovered.

“Mini-VM” container model

In a model where you treat containers like miniature VMs:

-

Containers will usually run a full copy of the user-mode components of the operating system.

-

Containers perform multiple functions or concerns, such as running two different types of services in the same container.

-

Containers allow administrative logins and change over time.

If you’re using containers like mini-VMs, you should inventory and protect them just like VMs. This means installing agents to inventory them, tracking users and software, and all of the other items from the VM section above.

In both models, you should inventory and update the images, because you don’t want new containers to be brought up with vulnerabilities.

Container orchestration systems

Containers are great, but what’s even better is to have something that takes care of bundling containers together to perform higher-level functions, starting up multiple copies of these bundles, performing load balancing to those copies, and providing other features such as easy ways for the components to talk to one another. This type of system is called a container orchestration system.

The most popular implementation of container orchestration as of this writing is Kubernetes with Docker containers. In a Kubernetes deployment, the primary assets are clusters, which hold pods, which hold Docker containers, which are copied from images. In a Kubernetes environment, consider inventorying the following components:

-

Kubernetes clusters, so that access to them can be controlled and the Kubernetes software may be kept up to date. Vulnerabilities in the Kubernetes software could compromise all of the pods running on it.

-

Kubernetes pods, which may contain one or more Docker containers. The Kubernetes command line or API may be used to track the pods currently in existence and which containers make up those pods.

-

Docker container images.

Application Platform-as-a-Service (aPaaS)

Application Platform-as-a-Service (aPaaS) offerings, such as Cloud Foundry or AWS Elastic Beanstalk, allow you to deploy your code without provisioning VMs yourself. These offerings also provide many resources, such as databases, as part of the platform. So, for example, a deployment may consist of the code you’ve written plus a database provisioned by the aPaaS. The deployment starts running when you create it and stops running when you destroy it, but you never have to actually create a VM or container to hold it; that’s done for you by your cloud provider.

Security of an aPaaS is very specific to aPaaS and to the provider’s implementation of that aPaaS. It’s important to understand the isolation model that keeps your compute, network, and storage separate from other cloud customers. For example, with many Cloud Foundry deployments, you will be running on the same VMs as other customers, which provides limited compute isolation. You will often not be able to contact other containers on the network, so you may have good network isolation. Storage isolation will depend upon what level, if any, encryption is performed by the persistent storage services available from your provider, and may vary from one storage service to another.

When you create an aPaaS deployment, you need to track both the deployment itself and its dependencies (such as build packs or other subcomponents) for the purposes of vulnerability and configuration management. However, you don’t need to inventory anything about the underlying compute resources or storage resources, because these are outside of your control.

Serverless

Serverless functions are a way to have your code running only as needed; some examples are AWS Lambda, Azure Functions, Google Cloud Functions, and IBM Cloud Functions.

Serverless offerings differ from application Platform-as-a-Service because nothing runs until its service has been requested; there’s nothing specific to you that sits around waiting for incoming requests. This means you don’t have to track both an “image” and the “instances” that are created from that image, because there are no long-running instances.

For serverless assets, you don’t need to inventory any operating system or platform components. You only need to inventory the serverless deployments you have so that you can manage vulnerabilities in your code and control access to the function.

Storage assets

Storage assets typically “persist” data, and as such tend to be more permanent than the other types of assets mentioned here. Sometimes data is described as “sticky”, because moving large amounts of data around can be difficult and time-consuming. You have already identified your most important data and storage assets in Chapter 2, but there may be other storage assets that you haven’t considered.

Because I recommend an asset-oriented approach to risk assessment for most organizations, this book places particular emphasis on storage assets. Access management is the most important security consideration for all of the cloud storage assets listed in the following sections.

Block storage

Block storage is just the cloud version of a hard drive; data is made available in small blocks to a server, such as 16KB, in the same manner as a spinning disk controller. Some examples are AWS Elastic Block Storage, Azure Virtual Disks, Google Persistent Disks, and IBM Cloud Block Storage.

The primary security concern with block storage is access management, because an attacker who gets direct access to the block storage bypasses any operating system level controls you may have on the server using that storage.

File storage

File storage is the cloud version of a filesystem, organizing data into directories and files. Some examples are AWS Elastic File System, Azure Files, Google Cloud Storage FUSE, and IBM Cloud File Storage. As with block storage, the primary concern is access management. Although the filesystem itself often provides access control lists for the files, these ACLs are enforced by the operating system, not by the file storage. An attacker with access to the file storage can read all files stored there.

Object storage

In storage terms, an “object” is very similar to a flat file, in that it is a stream of bytes with metadata about the file. The primary differences are:

-

Files are stored in folders that may be inside other folders. Objects are all thrown together into a “bucket”, without any further levels of organization inside the bucket.2

-

Objects may have custom metadata associated with them. Files are limited to the types of metadata that a filesystem provides, such as creator, creation time, and permissions.

-

Objects cannot be changed after creation. To make updates, you replace the object with a new object all at once. With files, you may update only part of a file, or add additional data to it.

-

Object storage offers per-object access control that is enforced by the object storage system. File storage typically enforces access control to the whole filesystem, but then depends upon the operating system using the filesystem to enforce per-file controls.

Most object storage offers different layers of access control, such as high-level policies for a bucket and individual ACLs for specific objects. There have been many notable data breaches when object storage bucket policies were set for open access, so it’s very important to keep track of your object storage assets and the access control policies for each one.

Some examples of object storage services are Amazon S3, Azure Blob storage, Google Cloud Storage, and IBM Cloud Object Storage.

Images

Images are chunks of code—including all the underlying system components, such as the operating system—that you use to run VMs, containers, or aPaaS deployments in a cloud environment. You make a copy of an image and start that copy running. The new copy is often called an “instance” and may begin to diverge from the image at that point. VMs, bare metal systems, containers, and application PaaS environments all copy images to create running systems.

While images are stored on some type of cloud storage, such as block storage or object storage, access to images is often controlled separately from the underlying storage.

Different types of cloud assets and providers manage images in different ways, but often there are many people in the organization who can get access to the contents of the images and create instances from them. For this reason, images shouldn’t contain every bit of information needed for an instance to run. For example, images should not contain sensitive information such as passwords or API keys, because not everyone who has access to create or view the image should know these secrets. The image should be configured so that when a copy (instance) of that image is started, the instance gets the secrets from a secure location that very few people have access to. This is discussed further in the Secrets Management section of Chapter 4. Depending on how you build images, you may be able to perform some checks to ensure secrets aren’t included in the image.

If your images do contain some sort of sensitive information, it’s important to track images and control access to them so that an attacker doesn’t look into the image, pull the credentials out, and use them. In addition, all images must be tracked so that they can be kept up to date with security patches for the operating system, middleware/platform, or custom application software. If you don’t, you’ll create cloud assets that are vulnerable as soon as they are created. This is discussed further in Chapter 5.

Cloud databases

Entire treatises have been written about the different types of databases, but as an extreme simplification, cloud databases tend to come in relational and non-relational flavors. A relational database will typically have multiple tables with defined ways to link the data in the different tables. A non-relational database will typically just have the data dumped in a single location in a semi-structured format.

The databases chosen can have significant impacts on the security of the overall application. For example, some in-memory databases used for fast performance do not natively offer encryption either over the network or on disk, which may be a risk depending on the types of data stored.

Most cloud providers offer several different flavors of both relational and non-relational databases. All cloud databases can provide access control at the database layer, and some databases can provide more fine-grained control of data in the database.

Message queues

Message queues allow components to send small amounts of data (typically less than 256KB) to one another, usually through a “publisher/subscriber” model. Although this can be convenient, even smaller chunks of data such as this may contain sensitive data, such as personally identifiable information, so it’s important to protect access to your message queues. In addition, if some of your components take instructions from messages, an attacker with write access to the message queue might be able to make them do something undesirable.

Secrets, such as encryption keys or passwords, should not be sent across a message queue in general, but should use a storage service specifically designed for this type of data, as described below and in Chapter 4.

Configuration storage

In many cases, a cloud deployment brings together code and configuration. The same code is usually shared between different instances of the application, and instances are deployed to different areas or regions using different configurations. Configuration storage allows you keep this configuration information separate from the code. Some examples are etcd, Hashicorp Consul, and AWS Systems Manager Parameter Store.

Secrets configuration storage

Secrets configuration storage is a subset of configuration storage specifically designed to hold secret data that may be used to access other systems. Just as it’s a good practice to separate your code and configurations, it’s also a good idea to separately access to your secrets from other configuration data. Many people may need to be able to view your code and your configurations, but very few people should be able to view the secrets! Therefore, it’s important to identify any assets that store secrets, make sure they’re built to protect those secrets, and carefully control access.

This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4. Some examples of secret storage solutions are Hashicorp Vault, Keywhiz, Kubernetes Secrets, and AWS Secrets Manager.

Encryption key storage

Encryption keys are a specific type of secret that are used for encrypting and decrypting data. As with secrets configuration, there are many benefits to using a special-purpose service for this type of data, such as being able to perform wrap and unwrap operations without exposing the master key. You need to identify any assets that store encryption keys and carefully control access to these in addition to controlling access to the encrypted data.

These types of systems were discussed in detail in Chapter 2, and the main types of encryption key storage are dedicated Hardware Security Modules and multi-tenant Key Management Systems.

Certificate storage

Another specialization of secret storage, certificate storage systems can safely store your x509 private keys, which are used to cryptographically prove that you own the certificate. In addition, these systems can alert you when one of your certificates is due to expire.

Source code repositories and deployment pipelines

Many organizations carefully track other types of assets, but allow their source code to be distributed all over the place and built using many different pipelines.

In many cases, source code doesn’t need to be kept secret if good practices such as separating out configuration and secrets are followed. However, ensuring that an attacker doesn’t modify your source code or any artifacts during the deployment path is very important, so these assets need to be tracked to protect integrity.

In addition, you need to have a good inventory of your source code repositories in order to effectively check for vulnerabilities. There are tools available to check for bugs in code you’ve written as well as known vulnerabilities in code you have incorporated from other sources. These tools cannot operate on code that they are not aware of! This will be covered in more depth in Chapter 5.

Network assets

Network assets are the cloud equivalent of on-premises switches, routers, VLANs, subnets, load balancer appliances, and similar assets. They enable communication between other assets and to the outside world, and often perform some security functions.

Virtual Private Clouds and subnets

Virtual Private Clouds (VPCs) and subnets are high-level ways to draw boundaries around what’s allowed to talk to what. It’s important to have a good inventory of these; as discussed earlier, many other controls such as network scans depend on having good inputs for what to scan to be effective. These are discussed further in Chapter 6.

Content Delivery Networks

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) can distribute content globally for low-latency access. While the information in a CDN may not be sensitive in most cases, an attacker with access to the CDN can poison the content with malware, bitcoin miners, or DDOS code.

DNS records

You need to track your DNS records and the registrars you use to register DNS. Although TLS connections offer protection against spoofing, as of this writing some browsers do not default to TLS. Spoofing DNS records can lead someone to go to an attacker’s site instead of yours, and then the attacker can steal credentials, read all of the data going through to your site, and even change data in transit.

In addition to security concerns, if you don’t track one of your DNS domains and forget to renew it, you’ll have a service outage!

TLS certificates

TLS certificates (often still called SSL certificates, and more properly x509 certificates) rely on cryptographic principles. They are the best line of defense against an attacker spoofing your web site. You need to track your TLS certificates for the following reasons:

-

There are cases where an entire class of certificates needs to be re-issued, such as when a particular cryptographic algorithm is found to be weak or when a certificate authority has a security issue.

-

You must track who has access to the private keys, because these individuals have the ability to impersonate your site.

-

Like DNS, if you forget to renew a certificate, you will often have a service outage because connections will fail when a certificate has expired.

If you have a large number of certificates, consider using a certificate storage service, discussed above, to track them.

Load balancers, reverse proxies, and web application firewalls

DNS records usually point to one of these network assets for processing and traffic direction. It’s important to have a good inventory of these assets for proper access control, because these assets can usually see and modify all of the network traffic to your applications. These are covered in more detail in Chapter 6.

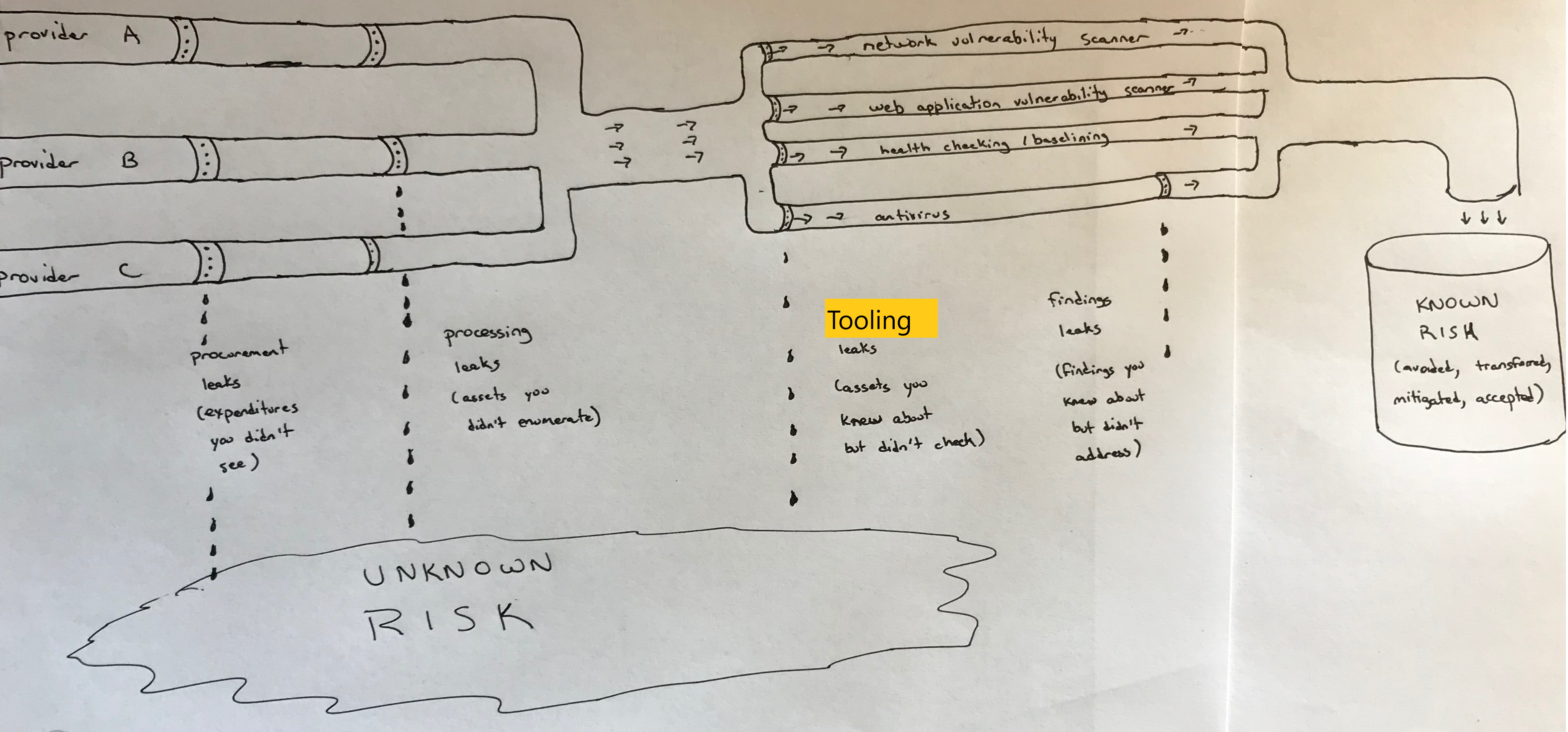

Asset Management Pipeline

So, now that you know what types of assets to look for, what can you do to track them? In most organizations, there are natural control points on the way to provision services and infrastructure. These will vary between organizations, but you must find those control points and tighten them up to ensure you know about all of your cloud assets and manage the risk appropriately.

I like to explain this using a plumbing analogy. Imagine you have a pipeline, containing your various cloud assets, flowing from your cloud providers and leading to your different security systems. You must try to prevent all of the “leaks” that could allow assets to get left out of important security efforts. This is true whether you’re running your entire company’s IT, or whether you’re only responsible for a single application. Conceptually this looks like Figure 3-1. We’ll look now at each piece of the plumbing.

Figure 3-1. Sample asset management pipeline

Procurement leaks

At the source you have multiple ways for assets to be created. You may have multiple cloud providers with different delivery models (IaaS, PaaS, SaaS) provisioning many different types of assets. In most cases, you’ll be charged for these assets. That often means that a good first step is with the procurement process.

Tip

Some cloud providers have built in asset management systems that already integrate with the other services they provide, and may even have ways to bring in assets from your on-premises environments or other cloud providers. This is a growing field, so look into what your providers offer before building something custom-made.

This isn’t foolproof — some cloud resources can be provisioned without spending any money, and in larger organizations people may be able to categorize their cloud expenses in different ways. However, it’s a good start.

Look through your IT charges. For each cloud expense, you need to go to the individual responsible for incurring the charges and get some limited auditing credentials.3 This will allow you to automatically pull inventory information. A “leak” here usually means that you’ve missed an entire cloud provider, either because you didn’t see the expense or because it’s a free service.4

Processing leaks

The second step is to use those audit credentials to find out exactly what the cloud providers are doing for you. That means you need to use their portals, APIs, or inventory systems to pull a list of assets. Note that you may have assets inside of other assets. For example, you may have a web server inside a container inside a VM.

Every cloud provider has a portal, API, or set of command line utilities that may be used to retrieve information about assets. Almost always, automation using the API or command line tools is preferable because manual inventories are difficult to keep up to date. However, a manual inventory is better than nothing, and might even be sufficient if changes are very infrequent.

In addition to portals and APIs, some cloud providers and third parties have inventory or security tracking systems. As of this writing, this is an immature area, but these offer considerable promise, so investigate whether there is a system that meets your requirements before creating something custom-made. Some systems allow you to track down to the level of what’s installed on different virtual machines, feed directly into other security services available such as scanners, and import assets from other providers or on-premises infrastructure. Table 3-0 lists some current services.

| Infrastructure | Ways to audit usage |

|---|---|

Amazon Web Services |

API, Portal, Command Line, AWS Systems Manager Inventory |

Microsoft Azure |

API, Portal, Command Line, Azure Automation Inventory |

Google Compute Platform |

API, Portal, Command Line, Cloud Security Command Center Asset Inventory |

IBM Cloud |

API, Portal, Command Line, IBM Cloud Security Advisor |

Kubernetes |

API, Dashboard |

Make sure you delve into each asset type to find additional assets that could be important from a security perspective. A “leak” here means that you queried the cloud provider for assets, but you didn’t inventory some cloud assets for that provider. For example, you may have inventoried all of the virtual machines, but missed the object storage buckets that your team provisioned. If you don’t inventory those object storage buckets, your downstream tools and processes cannot check the buckets to make sure that access to them is controlled properly, or that they’ve been assigned the proper tags.

Tooling leaks

The third step is to ensure that each tool that helps check the security of your assets is tied into this asset inventory and can obtain the information it needs to do its job. Some examples:

-

Your network vulnerability scanner should be able to obtain the IP addresses in use from the VM information or VPC subnet information.

-

Your web application vulnerability scanner should be able to obtain the URLs of each of your web applications.

-

Your health checking or baselining system needs to know about the different VMs so that it can check the configurations of each.

-

If your organization uses Windows systems, your antivirus solution will need a list of all Windows systems in order to effectively track alerts and ensure antivirus signatures are up to date.

A “leak” in this area means that you knew about some assets, but didn’t have your tools or processes check those assets for security issues. More information on these tools and protective measures will be discussed in Chapter 5, but there’s really no way for these tools to find security issues in assets that they don’t know about.

Findings leaks

The final step is to ensure you’re actually addressing any findings from your tooling systems. This may seem simple, but in practice these findings are often ignored, particularly with “noisy” scanning systems that create a lot of false positives.

It’s perfectly acceptable to decide to accept a finding (risk) without fixing it, but ignoring the findings without any sort of review is a “leak”.

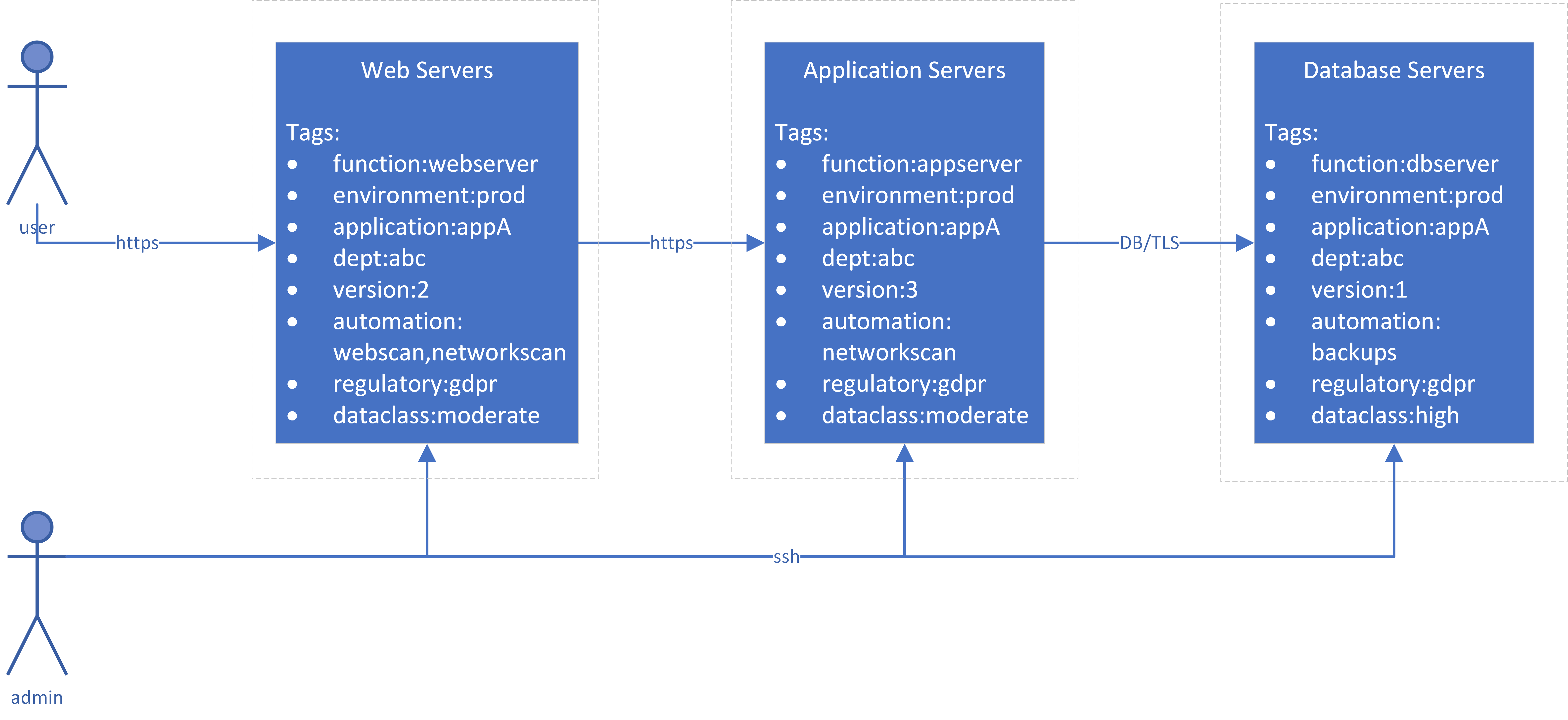

Tagging Cloud Assets

It makes sense to categorize and organize your assets when creating them, so that you know what they contain and what they are used for. Tags can make automation and access control much easier. Just as you tagged data assets with the types of data on them in Chapter 2, you also need to tag other types of assets with both the types of data processed by them as well as why the asset is needed.

It’s important to use the same data tags from Chapter 2 to indicate the types of data processed on compute assets, so that you have a consistent view of where your data is stored and processed. However, while it’s relatively simple to come up with a set of data classification levels or a list of compliance requirements, there are almost endless possibilities for other operational tags.

Some examples of the types of tags that may be useful are:

-

Function of the asset

-

Environment type for the asset, such as development, test, or production

-

Application or project that the asset is used for

-

Department that is responsible for the asset

-

Version number

-

Automation tags, which can indicate whether that asset should be selected for action by scripts, scanners, or other automation

Warning

With many cloud providers, tags are case sensitive, so ApplicationA and applicationA won’t match.

Looking at our sample application from Chapter 1, we can add some tags to the servers as seen in Figure 3-2:

Proper tagging can enable automated security checks. For example, perhaps you have a very sensible policy that sensitive data must not be stored or accessed on development and test systems. To help enforce this policy, you could:

-

Have automation that searches VMs and tags them with “dataclass:sensitive-data” if the automation detects either certain types of data (such as credit card numbers) or credentials to access sensitive data (such as the production database)

-

Have automation in your build processes to automatically tag VMs as “environment:development”, “environment:test”, or “environment:production” as they’re created

-

Create a report of any assets that have a “dataclass:sensitive-data” tag along with either a “environment:development” or “environment:test” tag

For tags to be effective, you must maintain a consistent set of tag names and allowed values, which means having a tagging policy and sticking to it. In most smaller organizations, the tagging policy should be organization-wide. A larger organization will need to agree on some organization-wide tags, as well as allow business-unit specific tags. In either case, there should be a clear owner of the tagging policy who adds additional tags to the official list as needed.

You may want to develop automation to collect all of the tags currently in use and report on any that are not specified in your organization or business unit tagging policy.

Summary

There are so many different as-a-service offerings available today that it can be very difficult to understand and track all of them.

You need to get the “biggest bang for the buck” for your tracking efforts. This means prioritizing the tracking of providers and assets where losing track of the asset is most likely to cause a large impact, such as assets that store or process sensitive data or that have administrative control over other assets. For example, you may choose not to worry about tracking all of your virtual machine images until you have tight tracking of all of your databases where customer data is stored, your existing virtual machines that have access to those databases, and your source code (and dependent libraries) that process customer data.

Use a pipeline approach that tracks cloud providers, assets created by those providers, what your security tooling does with those assets, and what you do with the findings from those security tools. If you have on-premises resources, treat those the same way as resources at a third party cloud provider, although you may not have tagging or an API for automation.

Asset management can also have important benefits besides security. For example, you may discover that you have assets that are no longer needed, and deleting these can cut costs in addition to reducing security risk. If you’re having difficulty getting support for an asset management solution based solely on security requirements, try pitching it also as a cost-control measure.

1 There are people who claim that bare metal is not cloud. By the most commonly accepted definition of cloud, NIST SP 800-145, the essential characteristics of cloud are on-demand self-service, broad network access, resource pooling, rapid elasticity, and managed service. None of these essential characteristics require virtualization technology, although there can be arguments over the definition of “rapid”.

2 You can simulate a folder hierarchy in object storage by using object names with slashes in them. However, if you want to display the objects in a “folder” named “A”, the object storage system is really just searching for all object names that begin with “A/”.

3 Make sure to follow the least privilege principle, and ensure that credentials for inventory automation don’t provide more power to your inventory system than absolutely necessary! An inventory system should not need to read anything but metadata or modify anything other than tags.

4 Note that free services are often not entirely “free”; the provider may get to use your data or get certain rights to your data, so you should inspect the terms of service!