Chapter 11. Classloading, Reflection, and Method Handles

In Chapter 3, we met Java’s Class objects, as a

way of representing a live type in a running Java process. In this

chapter, we will build on this foundation to discuss how the Java

environment loads and makes new types available. In the second half of

the chapter, we will introduce Java’s introspection capabilities—both

the original Reflection API and the newer Method Handles capabilities.

Class Files, Class Objects, and Metadata

Class files, as we saw in Chapter 1, are the result of compiling Java source files (or, potentially, other languages) into the intermediate form used by the JVM. These are binary files that are not designed to be human readable.

The runtime representation of these class files are the class objects that contain metadata, which represents the Java type that the class file was created from.

Examples of Class Objects

You can obtain a class object in Java in several ways. The simplest is:

Class<?>myCl=getClass();

This returns the class object of the instance that it is called from.

However, as we know from our survey of the public methods of Object,

the getClass() method on Object is public, so we can also obtain the

class of an arbitrary object o:

Class<?>c=o.getClass();

Class objects for known types can also be written as “class literals”:

// Express a class literal as a type name followed by ".class"c=int.class;// Same as Integer.TYPEc=String.class;// Same as "a string".getClass()c=byte[].class;// Type of byte arrays

For primitive types and void, we also have class objects that are

represented as literals:

// Obtain a Class object for primitive types with various// predefined constantsc=Void.TYPE;// The special "no-return-value" typec=Byte.TYPE;// Class object that represents a bytec=Integer.TYPE;// Class object that represents an intc=Double.TYPE;// etc.; see also Short, Character, Long, Float

For unknown types, we will have to use more sophisticated methods.

Class Objects and Metadata

The class objects contain metadata about the given type. This includes the methods, fields, constructors, and the like that are defined on the class in question. This metadata can be accessed by the programmer to investigate the class, even if nothing is known about the class when it is loaded.

For example, we can find all the deprecated methods in the class file

(they will be marked with the @Deprecated annotation):

Class<?>clz=getClassFromDisk();for(Methodm:clz.getMethods()){for(Annotationa:m.getAnnotations()){if(a.annotationType()==Deprecated.class){System.out.println(m.getName());}}}

We could also find the common ancestor class of a pair of class files. This simple form will work when both classes have been loaded by the same classloader:

publicstaticClass<?>commonAncestor(Class<?>cl1,Class<?>cl2){if(cl1==null||cl2==null)returnnull;if(cl1.equals(cl2))returncl1;if(cl1.isPrimitive()||cl2.isPrimitive())returnnull;List<Class<?>>ancestors=newArrayList<>();Class<?>c=cl1;while(!c.equals(Object.class)){if(c.equals(cl2))returnc;ancestors.add(c);c=c.getSuperclass();}c=cl2;while(!c.equals(Object.class)){for(Class<?>k:ancestors){if(c.equals(k))returnc;}c=c.getSuperclass();}returnObject.class;}

Class files have a very specific layout that they must conform to if they are to be legal and loadable by the JVM. The sections of the class file are (in order):

-

Magic number (all class files start with the four bytes

CA FE BA BEin hexadecimal) -

Version of class file standard in use

-

Constant pool for this class

-

Access flags (

abstract,public, etc.) -

Name of this class

-

Inheritance info (e.g., name of superclass)

-

Implemented interfaces

-

Fields

-

Methods

-

Attributes

The class file is a simple binary format, but it is not human readable.

Instead, tools like javap (see Chapter 13)

should be used to comprehend the contents.

One of the most often used sections in the class file is the Constant Pool, which contains representations of all the methods, classes, fields, and constants that the class needs to refer to (whether they are in this class or another). It is designed so that bytecodes can simply refer to a constant pool entry by its index number—which saves space in the bytecode representation.

There are a number of different class file versions created by various Java versions. However, one of Java’s backward compatibility rules is that JVMs (and tools) from newer versions can always use older class files.

Let’s look at how the classloading process takes a collection of bytes on disk and turns it into a new class object.

Phases of Classloading

Classloading is the process by which a new type is added to a running JVM process. This is the only way that new code can enter the system, and the only way to turn data into code in the Java platform. There are several phases to the process of classloading, so let’s examine them in turn.

Loading

The classloading process starts with loading a byte array. This is

usually read in from a filesystem, but can be read from a URL or other

location (often represented as a Path object).

The Classloader::defineClass() method is responsible for turning a

class file (represented as a byte array) into a class object. It is a

protected method and so is not accessible without subclassing.

The first job of defineClass() is loading. This produces the skeleton

of a class object, corresponding to the class you’re attempting to load.

By this stage, some basic checks have been performed on the class (e.g.,

the constants in the constant pool have been checked to ensure that

they’re self-consistent).

However, loading doesn’t produce a complete class object by itself, and the class isn’t yet usable. Instead, after loading, the class must be linked. This step breaks down into separate subphases:

-

Verification

-

Preparation and resolution

-

Initialization

Verification

Verification confirms that the class file conforms to expectations, and that it doesn’t try to violate the JVM’s security model (see “Secure Programming and Classloading” for details).

JVM bytecode is designed so that it can be (mostly) checked statically. This has the effect of slowing down the classloading process but speeding up runtime (as checks can be omitted).

The verification step is designed to prevent the JVM from executing bytecodes that might crash it or put it into an undefined and untested state where it might be vulnerable to other attacks by malicious code. Bytecode verification is a defense against malicious hand-crafted Java bytecodes and untrusted Java compilers that might output invalid bytecodes.

Note

The default methods mechanism works via classloading. When an implementation of an interface is being loaded, the class file is examined to see if implementations for default methods are present. If they are, classloading continues normally. If some are missing, the implementation is patched to add in the default implementation of the missing methods.

Preparation and Resolution

After successful verification, the class is prepared for use. Memory is allocated and static variables in the class are readied for initialization.

At this stage, variables aren’t initialized, and no bytecode from the new class has been executed. Before we run any code, the JVM checks that every type referred to by the new class file is known to the runtime. If the types aren’t known, they may also need to be loaded—which can kick off the classloading process again, as the JVM loads the new types.

This process of loading and discovery can execute iteratively until a stable set of types is reached. This is called the “transitive closure” of the original type that was loaded.1

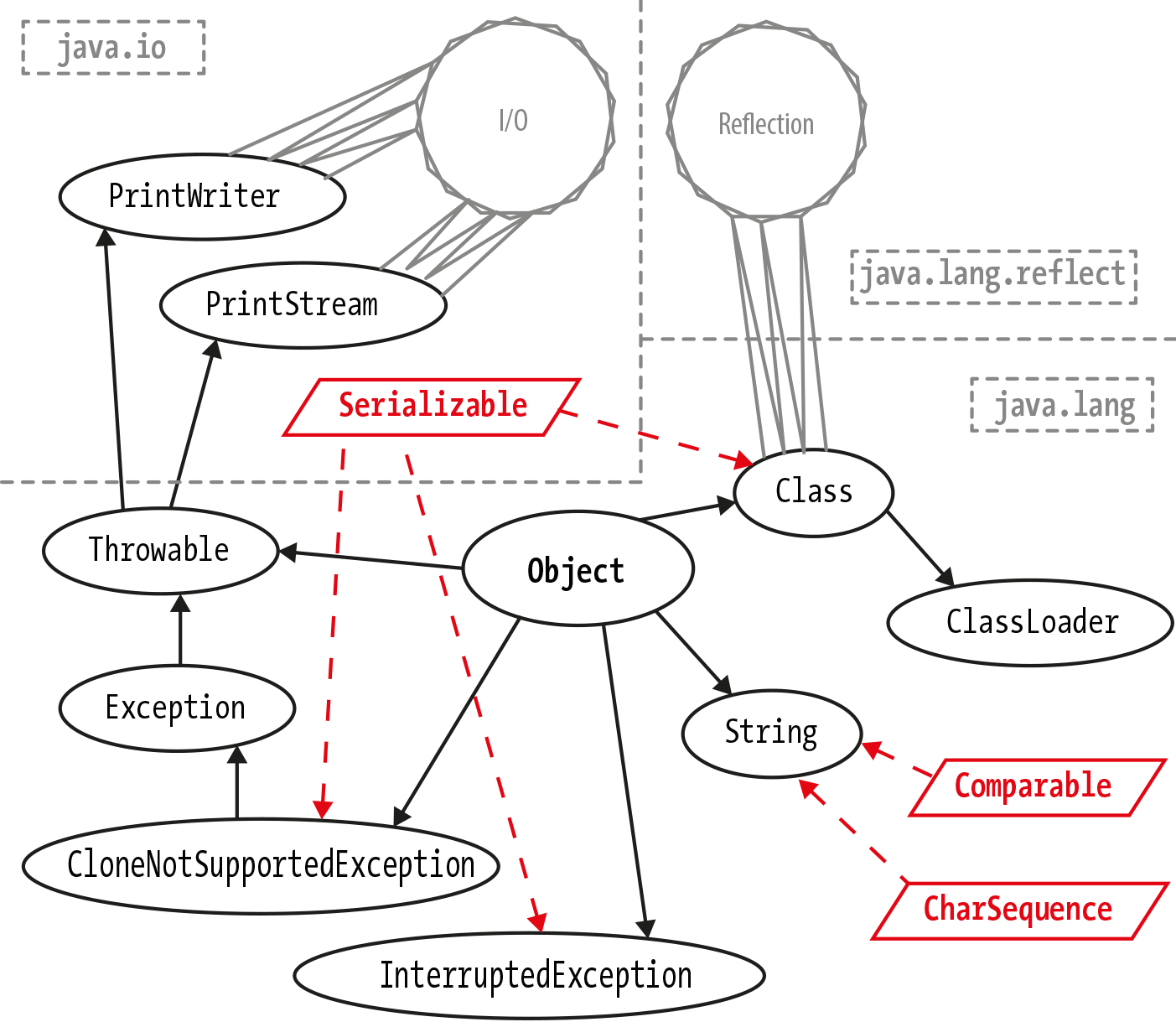

Let’s look at a quick example, by examining the dependencies of

java.lang.Object. Figure 11-1 shows a

simplified dependency graph for Object. It only shows the direct

dependencies of Object that are visible in the public API of Object,

and the direct, API-visible dependencies of those dependencies. In

addition, the dependencies of Class on the reflection subsystem, and

of PrintStream and PrintWriter on the I/O subsystems, are shown in

very simplified form.

In Figure 11-1, we can see part of the

transitive closure of Object.

Figure 11-1. Transitive closure of types

Initialization

Once resolved, the JVM can finally initialize the class. Static variables can be initialized and static initialization blocks are run.

This is the first time that the JVM is executing bytecode from the newly loaded class. When the static blocks complete, the class is fully loaded and ready to go.

Secure Programming and Classloading

Java programs can dynamically load Java classes from a variety of sources, including untrusted sources, such as websites reached across an insecure network. The ability to create and work with such dynamic sources of code is one of the great strengths and features of Java. To make it work successfully, however, Java puts great emphasis on a security architecture that allows untrusted code to run safely, without fear of damage to the host system.

Java’s classloading subsystem is where a lot of safety features are implemented. The central idea of the security aspects of the classloading architecture is that there is only one way to get new executable code into the process: a class.

This provides a “pinch point”—the only way to create a new class is to

use the functionality provided by Classloader to load a class from a

stream of bytes. By concentrating on making classloading secure, we can

constrain the attack surface that needs to be protected.

One extremely helpful aspect of the JVM’s design is that the JVM is a stack machine, so all operations are evaluated on a stack, rather than in registers. The stack state can be deduced at every point in a method, and this can be used to ensure that the bytecode doesn’t attempt to violate the security model.

Some of the security checks that are implemented by the JVM are:

-

All the bytecode of the class has valid parameters.

-

All methods are called with the right number of parameters of the correct static types.

-

Bytecode never tries to underflow or overflow the JVM stack.

-

Local variables are not used before they are initialized.

-

Variables are only assigned suitably typed values.

-

Field, method, and class access control modifiers must be respected.

-

No unsafe casts (e.g., attempts to convert an

intto a pointer). -

All branch instructions are to legal points within the same method.

Of fundamental importance is the approach to memory, and pointers. In assembly and C/C++, integers and pointers are interchangeable, so an integer can be used as a memory address. We can write it in assembly like this:

moveax,[STAT];Move4bytesfromaddrSTATintoeax

The lowest level of the Java security architecture involves the design of the Java Virtual Machine and the bytecodes it executes. The JVM does not allow any kind of direct access to individual memory addresses of the underlying system, which prevents Java code from interfering with the native hardware and operating system. These intentional restrictions on the JVM are reflected in the Java language itself, which does not support pointers or pointer arithmetic.

Neither the language nor the JVM allow an integer to be cast to an object reference or vice versa, and there is no way whatsoever to obtain an object’s address in memory. Without capabilities like these, malicious code simply cannot gain a foothold.

Recall from Chapter 2 that Java has two types of

values—primitives and object references. These are the only things

that can be put into variables. Note that “object contents” cannot be

put into variables. Java has no equivalent of C’s struct and always

has pass-by-value semantics. For reference types, what is passed is a

copy of the reference—which is a value.

References are represented in the JVM as pointers, but they are not directly manipulated by the bytecode. In fact, bytecode does not have opcodes for “access memory at location X.”

Instead, all we can do is access fields and methods; bytecode cannot call an arbitrary memory location. This means that the JVM always knows the difference between code and data. In turn, this prevents a whole class of stack overflow and other attacks.

Applied Classloading

To apply knowledge of classloading, it’s important to fully understand

java.lang.ClassLoader.

This is an abstract class that is fully functional and has no abstract

methods. The abstract modifier exists only to ensure that users must

subclass ClassLoader if they want to make use of it.

In addition to the aforementioned defineClass() method, we can load

classes via a public loadClass() method. This is commonly used by

the URLClassLoader subclass, which can load classes from a URL or file

path.

We can use URLClassLoader to load classes from the local disk like

this:

Stringcurrent=newFile(".").getCanonicalPath();try(URLClassLoaderulr=newURLClassLoader(newURL[]{newURL("file://"+current+"/")})){Class<?>clz=ulr.loadClass("com.example.DFACaller");System.out.println(clz.getName());}

The argument to loadClass() is the binary name of the class file. Note

that in order for the URLClassLoader to find the classes correctly,

they need to be in the expected place on the filesystem. In this

example, the class com.example.DFACaller would need to be found in the

file com/example/DFACaller.class relative to the working directory.

Alternatively, Class provides Class.forName(), a static method that

can load classes that are present on the classpath but that haven’t been

referred to yet.

This method takes a fully qualified class name. For example:

Class<?>jdbcClz=Class.forName("oracle.jdbc.driver.OracleDriver");

It throws a ClassNotFoundException if class can’t be found. As the

example indicates, this was commonly used in older versions of JDBC to

ensure that the correct driver was loaded, while avoiding a direct

import dependency on the driver classes.

With the advent of JDBC 4.0, this initialization step is no longer required.

Class.forName() has an alternative, three-argument form, which is

sometimes used in conjunction with alternative class loaders:

Class.forName(Stringname,booleaninited,Classloaderclassloader);

There are a host of subclasses of ClassLoader that deal with

individual special cases of classloading—which fit into the classloader

hierarchy.

Classloader Hierarchy

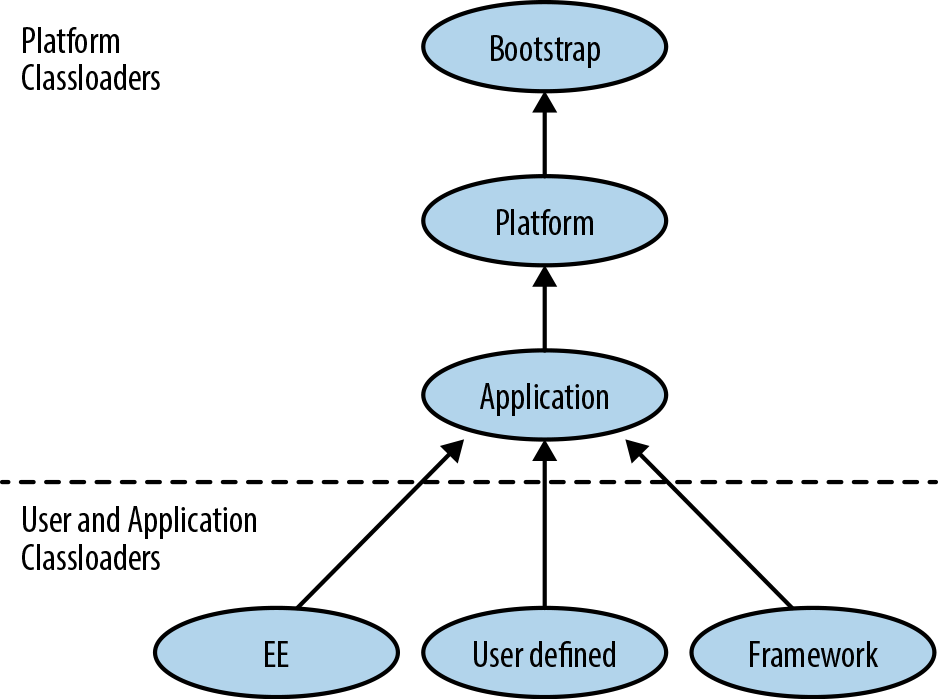

The JVM has a hierarchy of classloaders; each classloader in the system (apart from the initial, “bootstrap” classloader) has a parent that it can delegate to.

Note

The arrival of modules in Java 9 has affected the details of the way that classloading operates. In particular, the classloaders that load the JRE classes are now modular classloaders.

The convention is that a classloader will ask its parent to resolve and load a class, and will only perform the job itself if the parent classloader is unable to comply. Some common classloaders are shown in Figure 11-2.

Figure 11-2. Classloader hierarchy

Bootstrap classloader

This is the first classloader to appear in any JVM process, and is only used to load the core system classes. In older texts, it is sometimes referred to as the primordial classloader, but modern usage favors the bootstrap name.

For performance reasons, the bootstrap classloader does no verification, and relies on the boot classpath being secure. Types loaded by the bootstrap classloader are implicitly granted all security permissions and so this group of modules is kept as restricted as possible.

Platform classloader

This level of the classloader hierarchy was originally used as the extension classloader, but this mechanism has now been removed.

In its new role this classloader (which has the bootstrap classloader as its parent) is now known as the platform classloader. It is available via the method ClassLoader::getPlatformClassLoader and appears in (and is required by) the Java specification from version 9 onward.

It loads the remaining modules from the base system (the equivalent of the old rt.jar used in version 8 and earlier).

In the new modular implementations of Java, far less code is required to bootstrap a Java process and accordingly, as much JDK code (now represented as modules) as possible has been moved out of the scope of the bootstrap loader and into the platform loader instead.

Application classloader

This was historically sometimes called the system classloader, but this is a bad name, as it doesn’t load the system (the bootstrap and platform classloaders do). Instead, it is the classloader that loads application code from either the module path or the classpath. It is the most commonly encountered classloader, and it has the platform classloader as its parent.

To perform classloading, the application classloader first searches the named modules on the module path (the modules known to any of the three built-in classloaders). If the requested class is found in a module known to one of these classloaders then that classloader will load the class. If the class is not found in any known named module, the application classloader delegates to its parent (the platform classloader). If the parent fails to find the class, the application classloader searches the classpath. If the class is found on the classpath, it is loaded as a member of the application classloader’s unnamed module.

The application classloader is very widely used, but many advanced Java

frameworks require functionality that the main classloaders do not

supply. Instead, extensions to the standard classloaders are required.

This forms the basis of “custom classloading”—which relies on

implementing a new subclass of ClassLoader.

Custom classloader

When performing classloading, sooner or later we have to turn data

into code. As noted earlier, the defineClass() (actually a group of

related methods) is responsible for converting a byte[] into a class

object.

This method is usually called from a subclass—for example, this simple custom classloader that creates a class object from a file on disk:

publicstaticclassDiskLoaderextendsClassLoader{publicDiskLoader(){super(DiskLoader.class.getClassLoader());}publicClass<?>loadFromDisk(StringclzName)throwsIOException{byte[]b=Files.readAllBytes(Paths.get(clzName));returndefineClass(null,b,0,b.length);}}

Notice that in the preceding example we didn’t need to have the class

file in the “correct” location on disk, as we did for the

URLClassLoader example.

We need to provide a classloader to act as parent for any custom

classloader. In this example, we provided the classloader that loaded

the DiskLoader class (which would usually be the application

classloader).

Custom classloading is a very common technique in Java EE and advanced SE environments, and it provides very sophisticated capabilities to the Java platform. We’ll see an example of custom classloading later on in this chapter.

One drawback of dynamic classloading is that when working with a class object that we loaded dynamically, we typically have little or no information about the class. To work effectively with this class, we will therefore usually have to use a set of dynamic programming techniques known as reflection.

Reflection

Reflection is the capability of examining, operating on, and modifying objects at runtime. This includes modifying their structure and behavior—even self-modification.

Warning

The Java modules system introduces major changes to how reflection works on the platform. It is important to reread this section after you have gained an understanding of how modules work, and how the two capabilities interact.

Reflection is capable of working even when type and method names are not known at compile time. It uses the essential metadata provided by class objects, and can discover method or field names from the class object—and then acquire an object representing the method or field.

Instances can also be constructed reflexively (by using

Class::newInstance() or another constructor). With a reflexively

constructed object and a Method object, we can call any method

on an object of a previously unknown type.

This makes reflection a very powerful technique—so it’s important to understand when we should use it, and when it’s overkill.

When to Use Reflection

Many, if not most, Java frameworks use reflection in some capacity. Writing architectures that are flexible enough to cope with code that is unknown until runtime usually requires reflection. For example, plug-in architectures, debuggers, code browsers, and REPL-like environments are usually implemented on top of reflection.

Reflection is also widely used in testing (e.g., by the JUnit and TestNG libraries) and for mock object creation. If you’ve used any kind of Java framework you have almost certainly been using reflective code, even if you didn’t realize it.

To start using the Reflection API in your own code, the most important thing to realize is that it is about accessing objects where virtually no information is known, and that the interactions can be cumbersome because of this.

If some static information is known about dynamically loaded classes (e.g., that the classes loaded all implement a known interface), this can greatly simplify the interaction with the classes and reduce the burden of operating reflectively.

It is a common mistake to try to create a reflective framework that attempts to account for all possible circumstances, instead of dealing only with the cases that are immediately applicable to the problem domain.

How to Use Reflection

The first step in any reflective operation is to get a Class object

representing the type to be operated on. From this, other objects,

representing fields, methods, or constructors, can be accessed and

applied to instances of the unknown type.

To get an instance of an unknown type, it is simplest to use the

no-arg constructor, which is made available directly via the Class

object:

Class<?>clz=getSomeClassObject();Objectrcvr=clz.newInstance();

For constructors that take arguments, you will have to look up the

precise constructor needed, represented as a Constructor object.

The Method objects are one of the most commonly used objects provided

by the Reflection API. We’ll discuss them in detail—the Constructor and

Field objects are similar in many respects.

Method objects

A class object contains a Method object for each method on the class.

These are lazily created after classloading, and so they aren’t immediately

visible in an IDE’s debugger.

Let’s look at the source code from Method to see what information and

metadata is held for each method:

privateClass<?>clazz;privateintslot;// This is guaranteed to be interned by the VM in the 1.4// reflection implementationprivateStringname;privateClass<?>returnType;privateClass<?>[]parameterTypes;privateClass<?>[]exceptionTypes;privateintmodifiers;// Generics and annotations supportprivatetransientStringsignature;// Generic info repository; lazily initializedprivatetransientMethodRepositorygenericInfo;privatebyte[]annotations;privatebyte[]parameterAnnotations;privatebyte[]annotationDefault;privatevolatileMethodAccessormethodAccessor;

This provides all available information, including the exceptions the

method can throw, annotations (with a retention policy of RUNTIME),

and even the generics information that was otherwise removed by javac.

We can explore the metadata contained on the Method object by calling

accessor methods, but by far the single biggest use case for Method is

reflexive invocation.

The methods represented by these objects can be executed by reflection

using the invoke() method on Method. An example of invoking

hashCode() on a String object follows:

Objectrcvr="a";try{Class<?>[]argTypes=newClass[]{};Object[]args=null;Methodmeth=rcvr.getClass().getMethod("hashCode",argTypes);Objectret=meth.invoke(rcvr,args);System.out.println(ret);}catch(IllegalArgumentException|NoSuchMethodException|SecurityExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}catch(IllegalAccessException|InvocationTargetExceptionx){x.printStackTrace();}

To get the Method object we want to use, we call getMethod() on the

class object. This will return a reference to a Method corresponding

to a public method on the class.

Note that the static type of rcvr was declared to be Object. No

static type information was used during the reflective invocation. The

invoke() method also returns Object, so the actual return type of

hashCode() has been autoboxed to Integer.

This autoboxing is one of the aspects of Reflection where you can see some of the slight awkwardness of the API—which is the subject of the next section.

Problems with Reflection

Java’s Reflection API is often the only way to deal with dynamically loaded code, but there are a number of annoyances in the API that can make it slightly awkward to deal with:

-

Heavy use of

Object[]to represent call arguments and other instances. -

Also

Class[]when talking about types. -

Methods can be overloaded on name, so we need an array of types to distinguish between methods.

-

Representing primitive types can be problematic—we have to manually box and unbox.

void is a particular problem—there is a void.class, but it’s not

used consistently. Java doesn’t really know whether void is a type or

not, and some methods in the Reflection API use null instead.

This is cumbersome, and can be error prone—in particular, the slight verbosity of Java’s array syntax can lead to errors.

One further problem is the treatment of non-public methods. Instead

of using getMethod(), we must use getDeclaredMethod() to get a

reference to a non-public method, and then override the Java access

control subsystem with setAccessible() to allow it to be executed:

publicclassMyCache{privatevoidflush(){// Flush the cache...}}Class<?>clz=MyCache.class;try{Objectrcvr=clz.newInstance();Class<?>[]argTypes=newClass[]{};Object[]args=null;Methodmeth=clz.getDeclaredMethod("flush",argTypes);meth.setAccessible(true);meth.invoke(rcvr,args);}catch(IllegalArgumentException|NoSuchMethodException|InstantiationException|SecurityExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}catch(IllegalAccessException|InvocationTargetExceptionx){x.printStackTrace();}

However, it should be pointed out that reflection always involves unknown information. To some degree, we just have to live with some of this verbosity as the price of dealing with reflective invocation, and the dynamic, runtime power that it gives to the developer.

As a final example in this section, let’s show how to combine

reflection with custom classloading to inspect a class file on disk

and see if it contains any deprecated methods (these should be marked

with @Deprecated):

publicclassCustomClassloadingExamples{publicstaticclassDiskLoaderextendsClassLoader{publicDiskLoader(){super(DiskLoader.class.getClassLoader());}publicClass<?>loadFromDisk(StringclzName)throwsIOException{byte[]b=Files.readAllBytes(Paths.get(clzName));returndefineClass(null,b,0,b.length);}}publicvoidfindDeprecatedMethods(Class<?>clz){for(Methodm:clz.getMethods()){for(Annotationa:m.getAnnotations()){if(a.annotationType()==Deprecated.class){System.out.println(m.getName());}}}}publicstaticvoidmain(String[]args)throwsIOException,ClassNotFoundException{CustomClassloadingExamplesrfx=newCustomClassloadingExamples();if(args.length>0){DiskLoaderdlr=newDiskLoader();Class<?>clzToTest=dlr.loadFromDisk(args[0]);rfx.findDeprecatedMethods(clzToTest);}}}

Dynamic Proxies

One last piece of the Java Reflection story is the creation of

dynamic proxies. These are classes (which extend

java.lang.reflect.Proxy) that implement a number of interfaces. The

implementing class is constructed dynamically at runtime, and forwards

all calls to an invocation handler object:

InvocationHandlerh=newInvocationHandler(){@OverridepublicObjectinvoke(Objectproxy,Methodmethod,Object[]args)throwsThrowable{Stringname=method.getName();System.out.println("Called as: "+name);switch(name){case"isOpen":returnfalse;case"close":returnnull;}returnnull;}};Channelc=(Channel)Proxy.newProxyInstance(Channel.class.getClassLoader(),newClass[]{Channel.class},h);c.isOpen();c.close();

Proxies can be used as stand-in objects for testing (especially in test mocking approaches).

Another use case is to provide partial implementations of interfaces, or to decorate or otherwise control some aspect of delegation:

publicclassRememberingListimplementsInvocationHandler{privatefinalList<String>proxied=newArrayList<>();@OverridepublicObjectinvoke(Objectproxy,Methodmethod,Object[]args)throwsThrowable{Stringname=method.getName();switch(name){case"clear":returnnull;case"remove":case"removeAll":returnfalse;}returnmethod.invoke(proxied,args);}}RememberingListhList=newRememberingList();List<String>l=(List<String>)Proxy.newProxyInstance(List.class.getClassLoader(),newClass[]{List.class},hList);l.add("cat");l.add("bunny");l.clear();System.out.println(l);

Proxies are an extremely powerful and flexible capability that are used within many Java frameworks.

Method Handles

In Java 7, a brand new mechanism for introspection and method access

was introduced. This was originally designed for use with dynamic

languages, which may need to participate in method dispatch decisions at

runtime. To support this at the JVM level, the new invokedynamic

bytecode was introduced. This bytecode was not used by Java 7 itself,

but with the advent of Java 8, it was extensively used in both lambda

expressions and the Nashorn JavaScript implementation.

Even without invokedynamic, the new Method Handles API is comparable

in power to many aspects of the Reflection API—and can be cleaner and

conceptually simpler to use, even standalone. It can be thought of as

Reflection done in a safer, more modern way.

MethodType

In Reflection, method signatures are represented as Class[]. This is

quite cumbersome. By contrast, method handles rely on MethodType

objects. These are a typesafe and object-oriented way to represent

the type signature of a method.

They include the return type and argument types, but not the receiver type or name of the method. The name is not present, as this allows any method of the correct signature to be bound to any name (as per the functional interface behavior of lambda expressions).

A type signature for a method is represented as an immutable instance of

MethodType, as acquired from the factory method

MethodType.methodType(). For example:

MethodTypem2Str=MethodType.methodType(String.class);// toString()// Integer.parseInt()MethodTypemtParseInt=MethodType.methodType(Integer.class,String.class);// defineClass() from ClassLoaderMethodTypemtdefClz=MethodType.methodType(Class.class,String.class,byte[].class,int.class,int.class);

This single piece of the puzzle provides significant gains over Reflection, as it makes method signatures significantly easier to represent and discuss. The next step is to acquire a handle on a method. This is achieved by a lookup process.

Method Lookup

Method lookup queries are performed on the class where a method is

defined, and are dependent on the context that they are executed from.

In this example, we can see that when we attempt to look up the protected

Class::defineClass() method from a general lookup context, we fail to

resolve it with an IllegalAccessException, as the protected method is

not accessible:

publicstaticvoidlookupDefineClass(Lookupl){MethodTypemt=MethodType.methodType(Class.class,String.class,byte[].class,int.class,int.class);try{MethodHandlemh=l.findVirtual(ClassLoader.class,"defineClass",mt);System.out.println(mh);}catch(NoSuchMethodException|IllegalAccessExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}}Lookupl=MethodHandles.lookup();lookupDefineClass(l);

We always need to call MethodHandles.lookup()—this gives us a lookup

context object based on the currently executing method.

Lookup objects have several methods (which all start with find)

declared on them for method resolution. These include findVirtual(),

findConstructor(), and findStatic().

One big difference between the Reflection and Method Handles APIs is

access control. A Lookup object will only return methods that are

accessible to the context where the lookup was created—and there is no

way to subvert this (no equivalent of Reflection’s setAccessible()

hack).

Method handles therefore always comply with the security manager, even when the equivalent reflective code does not. They are access-checked at the point where the lookup context is constructed—the lookup object will not return handles to any methods to which it does not have proper access.

The lookup object, or method handles derived from it, can be returned to other contexts, including ones where access to the method would no longer be possible. Under those circumstances, the handle is still executable—access control is checked at lookup time, as we can see in this example:

publicclassSneakyLoaderextendsClassLoader{publicSneakyLoader(){super(SneakyLoader.class.getClassLoader());}publicLookupgetLookup(){returnMethodHandles.lookup();}}SneakyLoadersnLdr=newSneakyLoader();l=snLdr.getLookup();lookupDefineClass(l);

With a Lookup object, we’re able to produce method handles to any

method we have access to. We can also produce a way of accessing fields

that may not have a method that gives access. The findGetter() and

findSetter() methods on Lookup produce method handles that can read

or update fields as needed.

Invoking Method Handles

A method handle represents the ability to call a method. They are

strongly typed and as typesafe as possible. Instances are all of some

subclass of java.lang.invoke.MethodHandle, which is a class that needs

special treatment from the JVM.

There are two ways to invoke a method handle—invoke() and

invokeExact(). Both of these take the receiver and call arguments as

parameters. invokeExact() tries to call the method handle directly as

is, whereas invoke() will massage call arguments if needed.

In general, invoke() performs an asType() conversion if

necessary—this converts arguments according to these rules:

-

A primitive argument will be boxed if required.

-

A boxed primitive will be unboxed if required.

-

Primitives will be widened is necessary.

-

A

voidreturn type will be massaged to 0 ornull, depending on whether the expected return was primitive or of reference type. -

nullvalues are passed through, regardless of static type.

With these potential conversions in place, invocation looks like this:

Objectrcvr="a";try{MethodTypemt=MethodType.methodType(int.class);MethodHandles.Lookupl=MethodHandles.lookup();MethodHandlemh=l.findVirtual(rcvr.getClass(),"hashCode",mt);intret;try{ret=(int)mh.invoke(rcvr);System.out.println(ret);}catch(Throwablet){t.printStackTrace();}}catch(IllegalArgumentException|NoSuchMethodException|SecurityExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}catch(IllegalAccessExceptionx){x.printStackTrace();}

Method handles provide a clearer and more coherent way to access the same dynamic programming capabilities as Reflection. In addition, they are designed to work well with the low-level execution model of the JVM and thus hold out the promise of much better performance than Reflection can provide.