Chapter 3. Object-Oriented Programming in Java

Now that we’ve covered fundamental Java syntax, we are ready to begin object-oriented programming in Java. All Java programs use objects, and the type of an object is defined by its class or interface. Every Java program is defined as a class, and nontrivial programs include a number of classes and interface definitions.

This chapter explains how to define new classes and how to do object-oriented programming with them. We also introduce the concept of an interface, but a full discussion of interfaces and Java’s type system is deferred until Chapter 4.

Note

If you have experience with OO programming, however, be careful. The term “object-oriented” has different meanings in different languages. Don’t assume that Java works the same way as your favorite OO language. (This is particularly true for C++ or Python programmers.)

This is a fairly lengthy chapter, so let’s begin with an overview and some definitions.

Overview of Classes

Classes are the most fundamental structural element of all Java programs. You cannot write Java code without defining a class. All Java statements appear within classes, and all methods are implemented within classes.

Basic OO Definitions

Here are a couple important definitions:

- Class

-

A class is a collection of data fields that hold values and methods that operate on those values. A class defines a new reference type, such as the

Pointtype defined in Chapter 2.The

Pointclass defines a type that is the set of all possible two-dimensional points. - Object

-

An object is an instance of a class.

A

Pointobject is a value of that type: it represents a single two-dimensional point.

Objects are often created by instantiating a class with the new

keyword and a constructor invocation, as shown here:

Pointp=newPoint(1.0,2.0);

Constructors are covered later in this chapter in “Creating and Initializing Objects”.

A class definition consists of a signature and a body. The class signature defines the name of the class and may also specify other important information. The body of a class is a set of members enclosed in curly braces. The members of a class usually include fields and methods, and may also include constructors, initializers, and nested types.

Members can be static or nonstatic. A static member belongs to the class itself, while a nonstatic member is associated with the instances of a class (see “Fields and Methods”).

Note

There are four very common kinds of members—class fields, class methods, instance fields, and instance methods. The majority of work done with Java involves interacting with these kinds of members.

The signature of a class may declare that the class extends another class. The extended class is known as the superclass and the extension is known as the subclass. A subclass inherits the members of its superclass and may declare new members or override inherited methods with new implementations.

The members of a class may have access modifiers public,

protected, or private.1 These modifiers specify their

visibility and accessibility to clients and to subclasses. This allows

classes to control access to members that are not part of their public

API. This ability to hide members enables an object-oriented design

technique known as data encapsulation, which we discuss in

“Data Hiding and Encapsulation”.

Other Reference Types

The signature of a class may also declare that the class implements one or more interfaces. An interface is a reference type similar to a class that defines method signatures but does not usually include method bodies to implement the methods.

However, from Java 8 onward, interfaces may use the keyword default to

indicate that a method specified in the interface is optional. If a

method is optional, the interface file must include a default

implementation (hence the choice of keyword), which will be used by all

implementing classes that do not provide an implementation of the

optional method.

A class that implements an interface is required to provide bodies for the interface’s nondefault methods. Instances of a class that implement an interface are also instances of the interface type.

Classes and interfaces are the most important of the five fundamental reference types defined by Java. Arrays, enumerated types (or “enums”), and annotation types (usually just called “annotations”) are the other three. Arrays are covered in Chapter 2. Enums are a specialized kind of class and annotations are a specialized kind of interface—both are discussed later in Chapter 4, along with a full discussion of interfaces.

Class Definition Syntax

At its simplest level, a class definition consists of the keyword

class followed by the name of the class and a set of class members

within curly braces. The class keyword may be preceded by modifier

keywords and annotations. If the class extends another class, the class

name is followed by the extends keyword and the name of the class

being extended. If the class implements one or more interfaces, then the

class name or the extends clause is followed by the implements

keyword and a comma-separated list of interface names. For example:

publicclassIntegerextendsNumberimplementsSerializable,Comparable{// class members go here}

A generic class may also have type parameters and wildcards as part of its definition (see Chapter 4).

Class declarations may include modifier keywords. In addition to the access control modifiers (public, protected, etc.), these include:

abstract-

An

abstractclass is one whose implementation is incomplete and cannot be instantiated. Any class with one or moreabstractmethods must be declaredabstract. Abstract classes are discussed in “Abstract Classes and Methods”. final-

The

finalmodifier specifies that the class may not be extended. A class cannot be declared to be bothabstractandfinal. strictfp-

If a class is declared

strictfp, all its methods behave as if they were declaredstrictfp, and so exactly follow the formal semantics of the floating-point standard. This modifier is extremely rarely used.

Fields and Methods

A class can be viewed as a collection of data (also referred to as

state) and code to operate on that state. The data is stored in

fields, and the code is organized into methods.

This section covers fields and methods, the two most important kinds of class members. Fields and methods come in two distinct types: class members (also known as static members) are associated with the class itself, while instance members are associated with individual instances of the class (i.e., with objects). This gives us four kinds of members:

-

Class fields

-

Class methods

-

Instance fields

-

Instance methods

The simple class definition for the class Circle, shown in

Example 3-1, contains all four types of

members.

Example 3-1. A simple class and its members

publicclassCircle{// A class fieldpublicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.14159;// A useful constant// A class method: just compute a value based on the argumentspublicstaticdoubleradiansToDegrees(doubleradians){returnradians*180/PI;}// An instance fieldpublicdoubler;// The radius of the circle// Two instance methods: they operate on the instance fields of an objectpublicdoublearea(){// Compute the area of the circlereturnPI*r*r;}publicdoublecircumference(){// Compute the circumference// of the circlereturn2*PI*r;}}

Warning

It is not normally good practice to have a public field r—instead, it

would be much more usual to have a private field r and a method

radius() to provide access to it. The reason for this will be

explained later, in “Data Hiding and Encapsulation”. For now,

we use a public field simply to give examples of how to work with

instance fields.

The following sections explain all four common kinds of members. First, we cover the declaration syntax for fields. (The syntax for declaring methods is covered later in this chapter in “Data Hiding and Encapsulation”.)

Field Declaration Syntax

Field declaration syntax is much like the syntax for declaring local variables (see Chapter 2) except that field definitions may also include modifiers. The simplest field declaration consists of the field type followed by the field name.

The type may be preceded by zero or more modifier keywords or annotations, and the name may be followed by an equals sign and initializer expression that provides the initial value of the field. If two or more fields share the same type and modifiers, the type may be followed by a comma-separated list of field names and initializers. Here are some valid field declarations:

intx=1;privateStringname;publicstaticfinalintDAYS_PER_WEEK=7;String[]daynames=newString[DAYS_PER_WEEK];privateinta=17,b=37,c=53;

Field modifier keywords comprise zero or more of the following keywords:

public,protected,private-

These access modifiers specify whether and where a field can be used outside of the class that defines it.

static-

If present, this modifier specifies that the field is associated with the defining class itself rather than with each instance of the class.

final-

This modifier specifies that once the field has been initialized, its value may never be changed. Fields that are both

staticandfinalare compile-time constants thatjavacmay inline.finalfields can also be used to create classes whose instances are immutable. transient-

This modifier specifies that a field is not part of the persistent state of an object and that it need not be serialized along with the rest of the object.

volatile-

This modifier indicates that the field has extra semantics for concurrent use by two or more threads. The

volatilemodifier says that the value of a field must always be read from and flushed to main memory, and that it may not be cached by a thread (in a register or CPU cache). See Chapter 6 for more details.

Class Fields

A class field is associated with the class in which it is defined rather than with an instance of the class. The following line declares a class field:

publicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.14159;

This line declares a field of type double named PI and assigns it a

value of 3.14159.

The static modifier says that the field is a class field. Class

fields are sometimes called static fields because of this static

modifier. The final modifier says that the value of the field cannot be reassigned directly. Because the field PI represents a constant, we declare it final so that it cannot be changed.

It is a convention in Java (and many other languages) that constants are named with capital letters, which is why our field is named PI, not pi.

Defining constants like this is a common use for class fields, meaning that the static and final modifiers are often used together.

Not all class fields are constants, however.

In other words, a field can be declared static without being declared final.

Note

The use of public fields that are not final is almost never a

good practice—as multiple threads could update the field and cause

behavior that is extremely hard to debug.

A public static field is essentially a global variable. The names of class fields are qualified by the unique names of the classes that contain them, however. Thus, Java does not suffer from the name collisions that can affect other languages when different modules of code define global variables with the same name.

The key point to understand about a static field is that there is only a

single copy of it. This field is associated with the class itself, not

with instances of the class. If you look at the various methods of the

Circle class, you’ll see that they use this field. From inside the

Circle class, the field can be referred to simply as PI. Outside the

class, however, both class and field names are required to uniquely

specify the field. Methods that are not part of Circle access this

field as Circle.PI.

Class Methods

As with class fields, class methods are declared with the static

modifier:

publicstaticdoubleradiansToDegrees(doublerads){returnrads*180/PI;}

This line declares a class method named radiansToDegrees(). It has a

single parameter of type double and returns a double value.

Like class fields, class methods are associated with a class, rather than with an object. When invoking a class method from code that exists outside the class, you must specify both the name of the class and the method. For example:

// How many degrees is 2.0 radians?doubled=Circle.radiansToDegrees(2.0);

If you want to invoke a class method from inside the class in which it is defined, you don’t have to specify the class name. You can also shorten the amount of typing required via the use of a static import (as discussed in Chapter 2).

Note that the body of our Circle.radiansToDegrees() method uses the

class field PI. A class method can use any class fields and class

methods of its own class (or of any other class).

A class method cannot use any instance fields or instance methods

because class methods are not associated with an instance of the class.

In other words, although the radiansToDegrees() method is defined in

the Circle class, it cannot use the instance part of any Circle

objects.

Note

One way to think about this is that in any instance, we always have a reference—this—to the current object.

This is passed as an implicit parameter to any instance method.

However, class methods are not associated with a specific instance, so have no this reference, and no access to instance fields.

As we discussed earlier, a class field is essentially a global variable.

In a similar way, a class method is a global method, or global

function. Although radiansToDegrees() does not operate on Circle

objects, it is defined within the Circle class because it is a utility

method that is sometimes useful when you;re working with circles, and so it

makes sense to package it along with the other functionality of the

Circle class.

Instance Fields

Any field declared without the static modifier is an instance

field:

publicdoubler;// The radius of the circle

Instance fields are associated with instances of the class, so every

Circle object we create has its own copy of the double field r. In

our example, r represents the radius of a specific circle. Each

Circle object can have a radius independent of all other Circle

objects.

Inside a class definition, instance fields are referred to by name

alone. You can see an example of this if you look at the method body of

the circumference() instance method. In code outside the class, the

name of an instance method must be prefixed with a reference to the

object that contains it. For example, if the variable c holds a

reference to a Circle object, we use the expression c.r to refer to

the radius of that circle:

Circlec=newCircle();// Create a Circle object; store a ref in cc.r=2.0;// Assign a value to its instance field rCircled=newCircle();// Create a different Circle objectd.r=c.r*2;// Make this one twice as big

Instance fields are key to object-oriented programming. Instance fields hold the state of an object; the values of those fields make one object distinct from another.

Instance Methods

An instance method operates on a specific instance of a class (an

object), and any method not declared with the static keyword is

automatically an instance method.

Instance methods are the feature that makes object-oriented programming

start to get interesting. The Circle class defined in

Example 3-1 contains two instance methods,

area() and circumference(), that compute and return the area and

circumference of the circle represented by a given Circle object.

To use an instance method from outside the class in which it is defined, we must prefix it with a reference to the instance that is to be operated on. For example:

// Create a Circle object; store in variable cCirclec=newCircle();c.r=2.0;// Set an instance field of the objectdoublea=c.area();// Invoke an instance method of the object

Note

This is why it is called object-oriented programming; the object is the focus here, not the function call.

From within an instance method, we naturally have access to all the instance fields that belong to the object the method was called on. Recall that an object is often best considered to be a bundle containing state (represented as the fields of the object), and behavior (the methods to act on that state).

All instance methods are implemented by using an implicit parameter not shown in the method signature.

The implicit argument is named this; it holds a reference to the object through which the method is invoked.

In our example, that object is a Circle.

Note

The bodies of the area() and circumference() methods both use the

class field PI. We saw earlier that class methods can use only class

fields and class methods, not instance fields or methods. Instance

methods are not restricted in this way: they can use any member of a

class, whether it is declared static or not.

How the this Reference Works

The implicit this parameter is not shown in method signatures

because it is usually not needed; whenever a Java method accesses the

instance fields in its class, it is implicit that it is accessing fields

in the object referred to by the this parameter. The same is true when

an instance method invokes another instance method in the same

class—it’s taken that this means “call the instance method on the

current object.”

However, you can use the this keyword explicitly when you want to make

it clear that a method is accessing its own fields and/or methods. For

example, we can rewrite the area() method to use this explicitly to

refer to instance fields:

publicdoublearea(){returnCircle.PI*this.r*this.r;}

This code also uses the class name explicitly to refer to class field

PI. In a method this simple, it is not normally necessary to be quite

so explicit. In more complicated cases, however, you may sometimes find

that it increases the clarity of your code to use an explicit this

where it is not strictly required.

In some cases, the this keyword is required, however. For example,

when a method parameter or local variable in a method has the same name

as one of the fields of the class, you must use this to refer to the

field, because the field name used alone refers to the method parameter

or local variable.

For example, we can add the following method to the Circle class:

publicvoidsetRadius(doubler){this.r=r;// Assign the argument (r) to the field (this.r)// Note that we cannot just say r = r}

Some developers will deliberately choose the names of their method arguments in such a way that they don’t clash with field names, so the use of this can largely be avoided.

However, accessor methods (setter) generated by any of the major Java IDEs will use the this.x = x style shown here.

Finally, note that while instance methods can use the this keyword,

class methods cannot. This is because class methods are not associated

with individual objects.

Creating and Initializing Objects

Now that we’ve covered fields and methods, let’s move on to other important members of a class. In particular, we’ll look at constructors—these are class members whose job is to initialize the fields of a class as new instances of the class are created.

Take another look at how we’ve been creating Circle objects:

Circlec=newCircle();

This can easily be read as creating a new instance of Circle,

by calling something that looks a bit like a method. In fact, Circle()

is an example of a constructor. This is a member of a class that has

the same name as the class, and has a body, like a method.

Here’s how a constructor works. The new operator indicates that we

need to create a new instance of the class. First of all, memory is

allocated to hold the new object instance. Then, the constructor body is

called, with any arguments that have been specified. The constructor

uses these arguments to do whatever initialization of the new object is

necessary.

Every class in Java has at least one constructor, and their purpose is to perform any necessary initialization for a new object.

If the programmer does not explicitly define a constructor for a class, the javac compiler automatically creates a constructor (called the default constructor) that takes no arguments and performs no special initialization.

The Circle class seen in Example 3-1 used this mechanism to automatically delcare a constructor.

Defining a Constructor

There is some obvious initialization we could do for our Circle

objects, so let’s define a constructor.

Example 3-2 shows a new definition for

Circle that contains a constructor that lets us specify the radius of

a new Circle object. We’ve also taken the opportunity to make the

field r protected (to prevent access to it from arbitary objects).

Example 3-2. A constructor for the Circle class

publicclassCircle{publicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.14159;// A constant// An instance field that holds the radius of the circleprotecteddoubler;// The constructor: initialize the radius fieldpublicCircle(doubler){this.r=r;}// The instance methods: compute values based on the radiuspublicdoublecircumference(){return2*PI*r;}publicdoublearea(){returnPI*r*r;}publicdoubleradius(){returnr;}}

When we relied on the default constructor supplied by the compiler, we had to write code like this to initialize the radius explicitly:

Circlec=newCircle();c.r=0.25;

With the new constructor, the initialization becomes part of the object creation step:

Circlec=newCircle(0.25);

Here are some basic facts regarding naming, declaring, and writing constructors:

-

The constructor name is always the same as the class name.

-

A constructor is declared without a return type (not even the

voidplaceholder). -

The body of a constructor is the code that initializes the object. You can think of this as setting up the contents of the

thisreference. -

A constructor does not return

this(or any other value).

Defining Multiple Constructors

Sometimes you want to initialize an object in a number of different

ways, depending on what is most convenient in a particular circumstance.

For example, we might want to initialize the radius of a circle to a

specified value or a reasonable default value. Here’s how we can define

two constructors for Circle:

publicCircle(){r=1.0;}publicCircle(doubler){this.r=r;}

Because our Circle class has only a single instance field, we can’t

initialize it too many ways, of course. But in more complex classes, it

is often convenient to define a variety of constructors.

It is perfectly legal to define multiple constructors for a class, as long as each constructor has a different parameter list. The compiler determines which constructor you wish to use based on the number and type of arguments you supply. This ability to define multiple constructors is analogous to method overloading.

Invoking One Constructor from Another

A specialized use of the this keyword arises when a class has

multiple constructors; it can be used from a constructor to invoke one

of the other constructors of the same class. In other words, we can

rewrite the two previous Circle constructors as follows:

// This is the basic constructor: initialize the radiuspublicCircle(doubler){this.r=r;}// This constructor uses this() to invoke the constructor abovepublicCircle(){this(1.0);}

This is a useful technique when a number of constructors share a significant amount of initialization code, as it avoids repetition of that code. In more complex cases, where the constructors do a lot more initialization, this can be a very useful technique.

There is an important restriction on using this(): it can appear only

as the first statement in a constructor—but the call may be followed by

any additional initialization a particular constructor needs to perform.

The reason for this restriction involves the automatic invocation of

superclass constructors, which we’ll explore later in this chapter.

Field Defaults and Initializers

The fields of a class do not necessarily require initialization. If their initial values are not specified, the fields are automatically initialized to the default value false, \u0000, 0, 0.0, or null, depending on their type (see Table 2-1 for more details).

These default values are specified by the Java language specification and apply to both instance fields and class fields.

Note

The default values are essentially the “natural” interpretation of the zero bit pattern for each type.

If the default field value is not appropriate for your field, you can instead explicitly provide a different initial value. For example:

publicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.14159;publicdoubler=1.0;

Field declarations are not part of any method. Instead, the Java compiler generates initialization code for the field automatically and puts it into all the constructors for the class. The initialization code is inserted into a constructor in the order in which it appears in the source code, which means that a field initializer can use the initial values of any fields declared before it.

Consider the following code excerpt, which shows a constructor and two instance fields of a hypothetical class:

publicclassSampleClass{publicintlen=10;publicint[]table=newint[len];publicSampleClass(){for(inti=0;i<len;i++)table[i]=i;}// The rest of the class is omitted...}

In this case, the code generated by javac for the constructor is actually equivalent to the following:

publicSampleClass(){len=10;table=newint[len];for(inti=0;i<len;i++)table[i]=i;}

If a constructor begins with a this() call to another constructor, the

field initialization code does not appear in the first constructor.

Instead, the initialization is handled in the constructor invoked by the

this() call.

So, if instance fields are initialized in constructor, where are class fields initialized? These fields are associated with the class, even if no instances of the class are ever created. Logically, this means they need to be initialized even before a constructor is called.

To support this, javac generates a class initialization method automatically for every class. Class fields are initialized in the body of this method, which is invoked exactly once before the class is first used (often when the class is first loaded by the Java VM).

As with instance field initialization, class field initialization expressions are inserted into the class initialization method in the order in which they appear in the source code. This means that the initialization expression for a class field can use the class fields declared before it.

The class initialization method is an internal method that is hidden from Java programmers.

In the class file, it bears the name <clinit> (and you could see this method by, for example, examining the class file with javap—see Chapter 13 for more details on how to use javap to do this).

Initializer blocks

So far, we’ve seen that objects can be initialized through the initialization expressions for their fields and by arbitrary code in their constructors. A class has a class initialization method (which is like a constructor), but we cannot explicitly define the body of this method in Java, although it is perfectly legal to do so in bytecode.

Java does allow us to express class initialization, however, with a construct known as a static initializer.

A static initializer is simply the keyword static followed by a block of code in curly braces.

A static initializer can appear in a class definition anywhere a field or method definition can appear.

For example, consider the following code that performs some nontrivial initialization for two class fields:

// We can draw the outline of a circle using trigonometric functions// Trigonometry is slow, though, so we precompute a bunch of valuespublicclassTrigCircle{// Here are our static lookup tables and their own initializersprivatestaticfinalintNUMPTS=500;privatestaticdoublesines[]=newdouble[NUMPTS];privatestaticdoublecosines[]=newdouble[NUMPTS];// Here's a static initializer that fills in the arraysstatic{doublex=0.0;doubledelta_x=(Circle.PI/2)/(NUMPTS-1);for(inti=0,x=0.0;i<NUMPTS;i++,x+=delta_x){sines[i]=Math.sin(x);cosines[i]=Math.cos(x);}}// The rest of the class is omitted...}

A class can have any number of static initializers. The body of each

initializer block is incorporated into the class initialization method,

along with any static field initialization expressions. A static

initializer is like a class method in that it cannot use the this

keyword or any instance fields or instance methods of the class.

Subclasses and Inheritance

The Circle defined earlier is a simple class that distinguishes

circle objects only by their radii. Suppose, instead, that we want to

represent circles that have both a size and a position. For example, a

circle of radius 1.0 centered at point 0,0 in the Cartesian plane is

different from the circle of radius 1.0 centered at point 1,2. To do

this, we need a new class, which we’ll call PlaneCircle.

We’d like to add the ability to represent the position of a circle

without losing any of the existing functionality of the Circle class.

We do this by defining PlaneCircle as a subclass of Circle so that

PlaneCircle inherits the fields and methods of its superclass,

Circle. The ability to add functionality to a class by subclassing, or

extending, is central to the object-oriented programming paradigm.

Extending a Class

In Example 3-3, we show how we can implement

PlaneCircle as a subclass of the Circle class.

Example 3-3. Extending the Circle class

publicclassPlaneCircleextendsCircle{// We automatically inherit the fields and methods of Circle,// so we only have to put the new stuff here.// New instance fields that store the center point of the circleprivatefinaldoublecx,cy;// A new constructor to initialize the new fields// It uses a special syntax to invoke the Circle() constructorpublicPlaneCircle(doubler,doublex,doubley){super(r);// Invoke the constructor of the superclass, Circle()this.cx=x;// Initialize the instance field cxthis.cy=y;// Initialize the instance field cy}publicdoublegetCentreX(){returncx;}publicdoublegetCentreY(){returncy;}// The area() and circumference() methods are inherited from Circle// A new instance method that checks whether a point is inside the circle// Note that it uses the inherited instance field rpublicbooleanisInside(doublex,doubley){doubledx=x-cx,dy=y-cy;// Distance from centerdoubledistance=Math.sqrt(dx*dx+dy*dy);// Pythagorean theoremreturn(distance<r);// Returns true or false}}

Note the use of the keyword extends in the first line of

Example 3-3. This keyword tells Java that

PlaneCircle extends, or subclasses, Circle, meaning that it inherits

the fields and methods of that class.

The definition of the isInside() method shows field inheritance;

this method uses the field r (defined by the Circle class) as if it

were defined right in PlaneCircle itself. PlaneCircle also inherits

the methods of Circle. Therefore, if we have a PlaneCircle object

referenced by variable pc, we can say:

doubleratio=pc.circumference()/pc.area();

This works just as if the area() and circumference() methods were

defined in PlaneCircle itself.

Another feature of subclassing is that every PlaneCircle object is

also a perfectly legal Circle object. If pc refers to a

PlaneCircle object, we can assign it to a Circle variable and forget

all about its extra positioning capabilities:

// Unit circle at the originPlaneCirclepc=newPlaneCircle(1.0,0.0,0.0);Circlec=pc;// Assigned to a Circle variable without casting

This assignment of a PlaneCircle object to a Circle variable can be

done without a cast. As we discussed in Chapter 2,

a conversion like this is always legal. The value held in the Circle

variable c is still a valid PlaneCircle object, but the compiler

cannot know this for sure, so it doesn’t allow us to do the opposite

(narrowing) conversion without a cast:

// Narrowing conversions require a cast (and a runtime check by the VM)PlaneCirclepc2=(PlaneCircle)c;booleanorigininside=((PlaneCircle)c).isInside(0.0,0.0);

This distinction is covered in more detail in “Nested Types”, where we talk about the distinction between the compile and runtime type of an object.

Final classes

When a class is declared with the final modifier, it means that it cannot be extended or subclassed. java.lang.String is an example of a final class.

Declaring a class final prevents unwanted extensions to the class: if you invoke a method on a String object, you know that the method is the one defined by the String class itself, even if the String is passed to you from some unknown outside source.

In general, many of the classes that Java developers create should be final.

Think carefully about whether it will make sense to allow other (possibly unknown) code to extend your classes—if it doesn’t, then disallow the mechanism by declaring your classes final.

Superclasses, Object, and the Class Hierarchy

In our example, PlaneCircle is a subclass of Circle.

We can also say that Circle is the superclass of PlaneCircle.

The superclass of a class is specified in its extends clause, and a class may only have a single direct superclass:

publicclassPlaneCircleextendsCircle{...}

Every class the programmer defines has a superclass.

If the superclass is not specified with an extends clause, then the superclass is taken to be the class java.lang.Object.

As a result, the Object class is special for a couple of reasons:

-

It is the only class in Java that does not have a superclass.

-

All Java classes inherit (directly or indirectly) the methods of

Object.

Because every class (except Object) has a superclass, classes in Java

form a class hierarchy, which can be represented as a tree with

Object at its root.

Note

Object has no superclass, but every other class has exactly one

superclass. A subclass cannot extend more than one superclass. See

Chapter 4 for more information on how to achieve a

similar result.

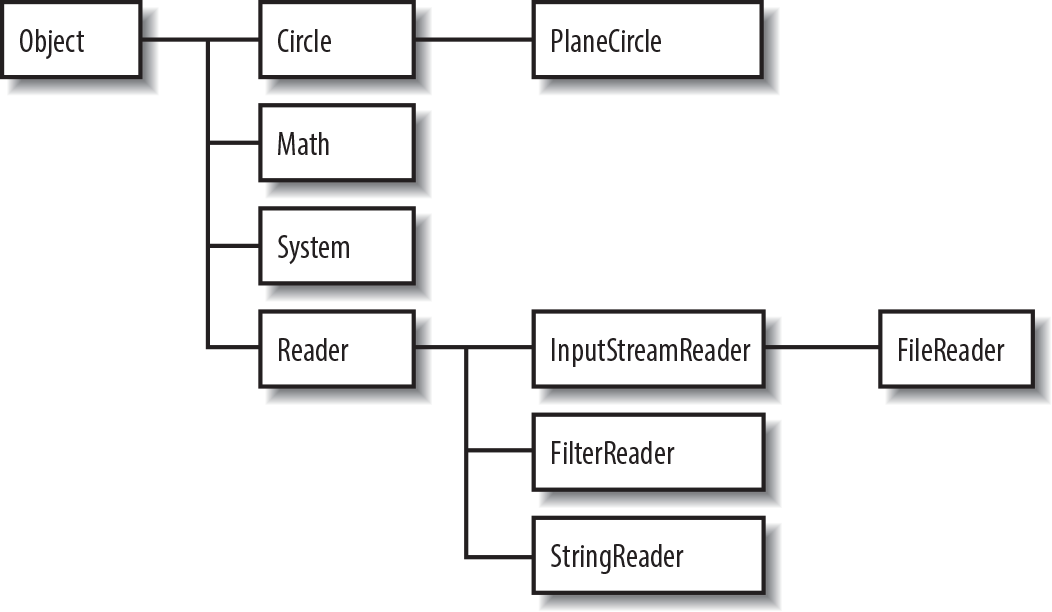

Figure 3-1 shows a partial class hierarchy

diagram that includes our Circle and PlaneCircle classes, as well as

some of the standard classes from the Java API.

Figure 3-1. A class hierarchy diagram

Subclass Constructors

Look again at the PlaneCircle() constructor from

Example 3-3:

publicPlaneCircle(doubler,doublex,doubley){super(r);// Invoke the constructor of the superclass, Circle()this.cx=x;// Initialize the instance field cxthis.cy=y;// Initialize the instance field cy}

Although this constructor explicitly initializes the cx and cy

fields newly defined by PlaneCircle, it relies on the superclass

Circle() constructor to initialize the inherited fields of the class.

To invoke the superclass constructor, our constructor calls super().

super is a reserved word in Java.

One of its main uses is to invoke the constructor of a superclass from within a subclass constructor.

This use is analogous to the use of this() to invoke one constructor of a class from within another constructor of the same class.

Invoking a constructor using super() is subject to the same restrictions as is using this():

-

super()can be used in this way only within a constructor. -

The call to the superclass constructor must appear as the first statement within the constructor, even before local variable declarations.

The arguments passed to super() must match the parameters of the superclass constructor.

If the superclass defines more than one constructor, super() can be used to invoke any one of them, depending on the arguments passed.

Constructor Chaining and the Default Constructor

Java guarantees that the constructor of a class is called whenever an instance of that class is created. It also guarantees that the constructor is called whenever an instance of any subclass is created. In order to guarantee this second point, Java must ensure that every constructor calls its superclass constructor.

Thus, if the first statement in a constructor does not explicitly invoke

another constructor with this() or super(), the javac compiler

inserts the call super() (i.e., it calls the superclass constructor

with no arguments). If the superclass does not have a visible

constructor that takes no arguments, this implicit invocation causes a

compilation error.

Consider what happens when we create a new instance of the PlaneCircle

class:

-

First, the

PlaneCircleconstructor is invoked. -

This constructor explicitly calls

super(r)to invoke aCircleconstructor. -

That

Circle()constructor implicitly callssuper()to invoke the constructor of its superclass,Object(Objectonly has one constructor). -

At this point, we’ve reached the top of the hierarchy and constructors start to run.

-

The body of the

Objectconstructor runs first. -

When it returns, the body of the

Circle()constructor runs. -

Finally, when the call to

super(r)returns, the remaining statements of thePlaneCircle()constructor are executed.

What all this means is that constructor calls are chained; any time an

object is created, a sequence of constructors is invoked, from subclass

to superclass on up to Object at the root of the class hierarchy.

Because a superclass constructor is always invoked as the first

statement of its subclass constructor, the body of the Object

constructor always runs first, followed by the constructor of its

subclass and on down the class hierarchy to the class that is being

instantiated.

Whenever a constructor is invoked, it can count on the fields of its superclass to be initialized by the time the constructor starts to run.

The default constructor

There is one missing piece in the previous description of constructor chaining. If a constructor does not invoke a superclass constructor, Java does so implicitly.

Note

If a class is declared without a constructor, Java implicitly adds a constructor to the class. This default constructor does nothing but invoke the superclass constructor.

For example, if we don’t declare a constructor for the PlaneCircle

class, Java implicitly inserts this constructor:

publicPlaneCircle(){super();}

In general, if a class does not define a no-argument constructor, all its subclasses must define constructors that explicitly invoke the superclass constructor with the necessary arguments.

If a class does not declare any constructors, it is given a no-argument

constructor by default. Classes declared public are given public

constructors. All other classes are given a default constructor that is

declared without any visibility modifier: such a constructor has default

visibility.

Note

If you are creating a public class that should not be publicly

instantiated, declare at least one non-public constructor

to prevent the insertion of a default public constructor.

Classes that should never be instantiated (such as java.lang.Math or java.lang.System) should define a private constructor.

Such a constructor can never be invoked from outside of the class, but it prevents the automatic insertion of the default constructor.

Hiding Superclass Fields

For the sake of example, imagine that our PlaneCircle class needs

to know the distance between the center of the circle and the origin

(0,0). We can add another instance field to hold this value:

publicdoubler;

Adding the following line to the constructor computes the value of the field:

this.r=Math.sqrt(cx*cx+cy*cy);// Pythagorean theorem

But wait; this new field r has the same name as the radius field r

in the Circle superclass. When this happens, we say that the field r

of PlaneCircle hides the field r of Circle. (This is a contrived

example, of course: the new field should really be called

distanceFromOrigin.)

Note

In code that you write, you should avoid declaring fields with names that hide superclass fields. It is almost always a sign of bad code.

With this new definition of PlaneCircle, the expressions r and

this.r both refer to the field of PlaneCircle. How, then, can we

refer to the field r of Circle that holds the radius of the circle?

A special syntax for this uses the super keyword:

r// Refers to the PlaneCircle fieldthis.r// Refers to the PlaneCircle fieldsuper.r// Refers to the Circle field

Another way to refer to a hidden field is to cast this (or any

instance of the class) to the appropriate superclass and then access the

field:

((Circle)this).r// Refers to field r of the Circle class

This casting technique is particularly useful when you need to refer to

a hidden field defined in a class that is not the immediate superclass.

Suppose, for example, that classes A, B, and C all define a field

named x and that C is a subclass of B, which is a subclass of A.

Then, in the methods of class C, you can refer to these different

fields as follows:

x// Field x in class Cthis.x// Field x in class Csuper.x// Field x in class B((B)this).x// Field x in class B((A)this).x// Field x in class Asuper.super.x// Illegal; does not refer to x in class A

Note

You cannot refer to a hidden field x in the superclass of a superclass

with super.super.x. This is not legal syntax.

Similarly, if you have an instance c of class C, you can refer to

the three fields named x like this:

c.x// Field x of class C((B)c).x// Field x of class B((A)c).x// Field x of class A

So far, we’ve been discussing instance fields. Class fields can also be

hidden. You can use the same super syntax to refer to the hidden value

of the field, but this is never necessary, as you can always refer to a

class field by prepending the name of the desired class. Suppose, for

example, that the implementer of PlaneCircle decides that the

Circle.PI field does not declare to enough decimal places. She can

define her own class field PI:

publicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.14159265358979323846;

Now code in PlaneCircle can use this more accurate value with the

expressions PI or PlaneCircle.PI. It can also refer to the old, less

accurate value with the expressions super.PI and Circle.PI. However,

the area() and circumference() methods inherited by PlaneCircle

are defined in the Circle class, so they use the value Circle.PI,

even though that value is hidden now by PlaneCircle.PI.

Overriding Superclass Methods

When a class defines an instance method using the same name, return type, and parameters as a method in its superclass, that method overrides the method of the superclass. When the method is invoked for an object of the class, it is the new definition of the method that is called, not the old definition from the superclass.

Tip

The return type of the overriding method may be a subclass of the return type of the original method (instead of being exactly the same type). This is known as a covariant return.

Method overriding is an important and useful technique in object-oriented programming.

PlaneCircle does not override either of the methods defined by Circle, and in fact it is difficult to think of a good example where any of the methods defined by Circle could have a well-defined override.

Warning

Don’t be tempted to consider subclassing Circle with a class like Ellipse—this would actually violate a core principle of object-oriented development (the Liskov principle, which we will meet later).

Instead, let’s look at a different example that does work with method overriding:

publicclassCar{publicstaticfinaldoubleLITRE_PER_100KM=8.9;protecteddoubletopSpeed;protecteddoublefuelTankCapacity;privateintdoors;publicCar(doubletopSpeed,doublefuelTankCapacity,intdoors){this.topSpeed=topSpeed;this.fuelTankCapacity=fuelTankCapacity;this.doors=doors;}publicdoublegetTopSpeed(){returntopSpeed;}publicintgetDoors(){returndoors;}publicdoublegetFuelTankCapacity(){returnfuelTankCapacity;}publicdoublerange(){return100*fuelTankCapacity/LITRE_PER_100KM;}}

This is a bit more complex, but will illustrate the concepts behind overriding.

Along with the Car class, we also have a specialized class, SportsCar.

This has several differences: it has a fixed-size fuel tank and only comes in a two-door version.

It may also have a much higher top speed than the regular form, but if the top speed rises above 200 km/h then the fuel efficiency of the car suffers, and as a result the overall range of the car starts to decrease:

publicclassSportsCarextendsCar{privatedoubleefficiency;publicSportsCar(doubletopSpeed){super(topSpeed,50.0,2);if(topSpeed>200.0){efficiency=200.0/topSpeed;}else{efficiency=1.0;}}publicdoublegetEfficiency(){returnefficiency;}@Overridepublicdoublerange(){return100*fuelTankCapacity*efficiency/LITRE_PER_100KM;}}

The upcoming discussion of method overriding considers only instance methods. Class methods behave quite differently, and they cannot be overridden. Just like fields, class methods can be hidden by a subclass but not overridden. As noted earlier in this chapter, it is good programming style to always prefix a class method invocation with the name of the class in which it is defined. If you consider the class name part of the class method name, the two methods have different names, so nothing is actually hidden at all.

Before we go any further with the discussion of method overriding, you should understand the difference between method overriding and method overloading. As we discussed in Chapter 2, method overloading refers to the practice of defining multiple methods (in the same class) that have the same name but different parameter lists. This is very different from method overriding, so don’t get them confused.

Overriding is not hiding

Although Java treats the fields and methods of a class analogously in many ways, method overriding is not like field hiding at all. You can refer to hidden fields simply by casting an object to an instance of the appropriate superclass, but you cannot invoke overridden instance methods with this technique. The following code illustrates this crucial difference:

classA{// Define a class named Ainti=1;// An instance fieldintf(){returni;}// An instance methodstaticcharg(){return'A';}// A class method}classBextendsA{// Define a subclass of Ainti=2;// Hides field i in class Aintf(){return-i;}// Overrides method f in class Astaticcharg(){return'B';}// Hides class method g() in class A}publicclassOverrideTest{publicstaticvoidmain(Stringargs[]){Bb=newB();// Creates a new object of type BSystem.out.println(b.i);// Refers to B.i; prints 2System.out.println(b.f());// Refers to B.f(); prints -2System.out.println(b.g());// Refers to B.g(); prints BSystem.out.println(B.g());// A better way to invoke B.g()Aa=(A)b;// Casts b to an instance of class ASystem.out.println(a.i);// Now refers to A.i; prints 1System.out.println(a.f());// Still refers to B.f(); prints -2System.out.println(a.g());// Refers to A.g(); prints ASystem.out.println(A.g());// A better way to invoke A.g()}}

While this difference between method overriding and field hiding may seem surprising at first, a little thought makes the purpose clear.

Suppose we are manipulating a bunch of Car and SportsCar objects, and store them in an array of type Car[]. We can do this because SportsCar is a subclass of Car, so all SportsCar objects are legal Car objects.

When we loop through the elements of this array, we don’t have to know or care whether the element is actually a Car or an SportsCar.

What we do care about very much, however, is that the correct value is computed when we invoke the range() method of any element of the array.

In other words, we don’t want to use the formula for the range of a car when the object is actually a sports car!

All we really want is for the objects we’re computing the ranges of to “do the right thing”—the Car objects to use their definition of how to compute their own range, and the SportsCar objects to use the definition that is correct for them.

Seen in this context, it is not surprising at all that method overriding is handled differently by Java than is field hiding.

Virtual method lookup

If we have a Car[] array that holds Car and SportsCar objects, how does javac know whether to call the range() method of the Car class or the SportsCar class for any given item in the array?

In fact, the source code compiler cannot know this at compilation time.

Instead, javac creates bytecode that uses virtual method lookup at runtime. When the interpreter runs the code, it looks up the appropriate range() method to call for each of the objects in the array.

That is, when the interpreter interprets the expression o.range(), it checks the actual runtime type of the object referred to by the variable o and then finds the range() method that is appropriate for that type.

Note

Some other languages (such as C# or C++) do not do virtual lookup by

default and instead have a virtual keyword that programmers must

explicitly use if they want to allow subclasses to be able to override a

method.

The JVM does not simply use the range() method that is associated with the static type of the variable o, as that would not allow method overriding to work in the way detailed earlier.

Virtual method lookup is the default for Java instance methods.

See Chapter 4 for more details about compile-time and runtime type and how this affects virtual method lookup.

Invoking an overridden method

We’ve seen the important differences between method overriding and

field hiding. Nevertheless, the Java syntax for invoking an overridden

method is quite similar to the syntax for accessing a hidden field: both

use the super keyword. The following code illustrates:

classA{inti=1;// An instance field hidden by subclass Bintf(){returni;}// An instance method overridden by subclass B}classBextendsA{inti;// This field hides i in Aintf(){// This method overrides f() in Ai=super.i+1;// It can retrieve A.i like thisreturnsuper.f()+i;// It can invoke A.f() like this}}

Recall that when you use super to refer to a hidden field, it is the

same as casting this to the superclass type and accessing the field

through that. Using super to invoke an overridden method, however, is

not the same as casting the this reference. In other words, in the

previous code, the expression super.f() is not the same as

((A)this).f().

When the interpreter invokes an instance method with the super syntax,

a modified form of virtual method lookup is performed. The first step,

as in regular virtual method lookup, is to determine the actual class of

the object through which the method is invoked. Normally, the runtime

search for an appropriate method definition would begin with this class.

When a method is invoked with the super syntax, however, the search

begins at the superclass of the class. If the superclass implements the

method directly, that version of the method is invoked. If the

superclass inherits the method, the inherited version of the method is

invoked.

Note that the super keyword invokes the most immediately overridden

version of a method. Suppose class A has a subclass B that has a

subclass C and that all three classes define the same method f().

The method C.f() can invoke the method B.f(), which it overrides

directly, with super.f(). But there is no way for C.f() to invoke

A.f() directly: super.super.f() is not legal Java syntax. Of

course, if C.f() invokes B.f(), it is reasonable to suppose that

B.f() might also invoke A.f().

This kind of chaining is relatively common with overridden methods: it is a way of augmenting the behavior of a method without replacing the method entirely.

Note

Don’t confuse the use of super to invoke an overridden method with the

super() method call used in a constructor to invoke a superclass

constructor. Although they both use the same keyword, these are two

entirely different syntaxes. In particular, you can use super to

invoke an overridden method anywhere in the overriding class, while you

can use super() only to invoke a superclass constructor as the very

first statement of a constructor.

It is also important to remember that super can be used only to invoke an overridden method from within the class that overrides it.

Given a reference to a SportsCar object e, there is no way for a program that uses e to invoke the range() method defined by the Car class on e.

Data Hiding and Encapsulation

We started this chapter by describing a class as a collection of data and methods. One of the most important object-oriented techniques we haven’t discussed so far is hiding the data within the class and making it available only through the methods.

This technique is known as encapsulation because it seals the data (and internal methods) safely inside the “capsule” of the class, where it can be accessed only by trusted users (i.e., the methods of the class).

Why would you want to do this? The most important reason is to hide the internal implementation details of your class. If you prevent programmers from relying on those details, you can safely modify the implementation without worrying that you will break existing code that uses the class.

Note

You should always encapsulate your code. It is almost always impossible to reason through and ensure the correctness of code that hasn’t been well-encapsulated, especially in multithreaded environments (and essentially all Java programs are multithreaded).

Another reason for encapsulation is to protect your class against accidental or willful stupidity. A class often contains a number of interdependent fields that must be in a consistent state. If you allow a programmer (including yourself) to manipulate those fields directly, he may change one field without changing important related fields, leaving the class in an inconsistent state. If instead he has to call a method to change the field, that method can be sure to do everything necessary to keep the state consistent. Similarly, if a class defines certain methods for internal use only, hiding these methods prevents users of the class from calling them.

Here’s another way to think about encapsulation: when all the data for a class is hidden, the methods define the only possible operations that can be performed on objects of that class.

Once you have carefully tested and debugged your methods, you can be confident that the class will work as expected. On the other hand, if all the fields of the class can be directly manipulated, the number of possibilities you have to test becomes unmanageable.

Note

This idea can be carried to a very powerful conclusion, as we will see in “Safe Java Programming” when we discuss the safety of Java programs (which differs from the concept of type safety of the Java programming language).

Other, secondary, reasons to hide fields and methods of a class include:

-

Internal fields and methods that are visible outside the class just clutter up the API. Keeping visible fields to a minimum keeps your class tidy and therefore easier to use and understand.

-

If a method is visible to the users of your class, you have to document it. Save yourself time and effort by hiding it instead.

Access Control

Java defines access control rules that can restrict members of a class

from being used outside the class. In a number of examples in this

chapter, you’ve seen the public modifier used in field and method

declarations. This public keyword, along with protected and

private (and one other, special one) are access control

modifiers; they specify the access rules for the field or method.

Access to modules

One of the biggest changes in Java 9 was the arrival of Java platform modules. These are a grouping of code that is larger than a single package, and which are intended as the future way to deploy code for reuse. As Java is often used in large applications and environments, the arrival of modules should make it easier to build and manage enterprise codebases.

The modules technology is an advanced topic, and if Java is one of the first programming languages you have encountered, you should not try to learn it until you have gained some language proficiency. An introductory treatment of modules is provided in Chapter 12 and we defer discussing the access control impact of modules until then.

Access to packages

Access control on a per-package basis is not directly part of the Java language. Instead, access control is usually done at the level of classes and members of classes.

Note

A package that has been loaded is always accessible to code defined within the same package. Whether it is accessible to code from other packages depends on the way the package is deployed on the host system. When the class files that comprise a package are stored in a directory, for example, a user must have read access to the directory and the files within it in order to have access to the package.

Access to classes

By default, top-level classes are accessible within the package in

which they are defined. However, if a top-level class is declared

public, it is accessible everywhere.

Tip

In Chapter 4, we’ll meet nested classes. These are classes that can be defined as members of other classes. Because these inner classes are members of a class, they also obey the member access-control rules.

Access to members

The members of a class are always accessible within the body of the

class. By default, members are also accessible throughout the package in

which the class is defined. This default level of access is often

called package access. It is only one of four possible levels of

access. The other three levels are defined by the public, protected,

and private modifiers. Here is some example code that uses these

modifiers:

publicclassLaundromat{// People can use this class.privateLaundry[]dirty;// They cannot use this internal field,publicvoidwash(){...}// but they can use these public methodspublicvoiddry(){...}// to manipulate the internal field.// A subclass might want to tweak this fieldprotectedinttemperature;}

These access rules apply to members of a class:

-

All the fields and methods of a class can always be used within the body of the class itself.

-

If a member of a class is declared with the

publicmodifier, it means that the member is accessible anywhere the containing class is accessible. This is the least restrictive type of access control. -

If a member of a class is declared

private, the member is never accessible, except within the class itself. This is the most restrictive type of access control. -

If a member of a class is declared

protected, it is accessible to all classes within the package (the same as the default package accessibility) and also accessible within the body of any subclass of the class, regardless of the package in which that subclass is defined. -

If a member of a class is not declared with any of these modifiers, it has default access (sometimes called package access) and it is accessible to code within all classes that are defined in the same package but inaccessible outside of the package.

Note

Default access is more restrictive than protected—as default access

does not allow access by subclasses outside the package.

protected access requires more elaboration. Suppose class A declares

a protected field x and is extended by a class B, which is defined

in a different package (this last point is important). Class B

inherits the protected field x, and its code can access that field

in the current instance of B or in any other instances of B that the

code can refer to. This does not mean, however, that the code of class

B can start reading the protected fields of arbitrary instances of

A.

Let’s look at this language detail in code. Here’s the definition for

A:

packagejavanut7.ch03;publicclassA{protectedfinalStringname;publicA(Stringnamed){name=named;}publicStringgetName(){returnname;}}

Here’s the definition for B:

packagejavanut7.ch03.different;importjavanut7.ch03.A;publicclassBextendsA{publicB(Stringnamed){super(named);}@OverridepublicStringgetName(){return"B: "+name;}}

Note

Java packages do not “nest,” so javanut7.ch03.different is just a

different package than javanut7.ch03; it is not contained inside it or

related to it in any way.

However, if we try to add this new method to B, we will get a

compilation error, because instances of B do not have access to

arbitary instances of A:

publicStringexamine(Aa){return"B sees: "+a.name;}

If we change the method to this:

publicStringexamine(Bb){return"B sees another B: "+b.name;}

then the compiler is happy, because instances of the same exact type can

always see each other’s protected fields. Of course, if B was in the

same package as A, then any instance of B could read any protected

field of any instance of A because protected fields are visible to

every class in the same package.

Access control and inheritance

The Java specification states that:

-

A subclass inherits all the instance fields and instance methods of its superclass accessible to it.

-

If the subclass is defined in the same package as the superclass, it inherits all non-

privateinstance fields and methods. -

If the subclass is defined in a different package, it inherits all

protectedandpublicinstance fields and methods. -

privatefields and methods are never inherited; neither are class fields or class methods. -

Constructors are not inherited (instead, they are chained, as described earlier in this chapter).

However, some programmers are confused by the statement that a subclass

does not inherit the inaccessible fields and methods of its superclass.

It could be taken to imply that when you create an instance of a

subclass, no memory is allocated for any private fields defined by the

superclass. This is not the intent of the statement, however.

Note

Every instance of a subclass does, in fact, include a complete instance of the superclass within it, including all inaccessible fields and methods.

This existence of potentially inaccessible members seems to be in conflict with the statement that the members of a class are always accessible within the body of the class. To clear up this confusion, we define “inherited members” to mean those superclass members that are accessible.

Then the correct statement about member accessibility is: “All inherited members and all members defined in this class are accessible.” An alternative way of saying this is:

-

A class inherits all instance fields and instance methods (but not constructors) of its superclass.

-

The body of a class can always access all the fields and methods it declares itself. It can also access the accessible fields and members it inherits from its superclass.

Member access summary

We summarize the member access rules in Table 3-1.

| Member visibility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessible to | Public | Protected | Default | Private |

|

Defining class |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Class in same package |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Subclass in different package |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Nonsubclass different package |

Yes | No | No | No |

There are a few generally observed rules about what parts of a Java program should use each visibility modifier. It is important that even beginning Java programmers follow these rules:

-

Use

publiconly for methods and constants that form part of the public API of the class. The only acceptable usage ofpublicfields is for constants or immutable objects, and they must be also declaredfinal. -

Use

protectedfor fields and methods that aren’t required by most programmers using the class but that may be of interest to anyone creating a subclass as part of a different package.

Note

protected members are technically part of the exported API of a class.

They must be documented and cannot be changed without potentially

breaking code that relies on them.

-

Use the default package visibility for fields and methods that are internal implementation details but are used by cooperating classes in the same package.

-

Use

privatefor fields and methods that are used only inside the class and should be hidden everywhere else.

If you are not sure whether to use protected, package, or private

accessibility, start with private. If this is overly restrictive, you

can always relax the access restrictions slightly (or provide accessor

methods, in the case of fields).

This is especially important for designing APIs because increasing access restrictions is not a backward-compatible change and can break code that relies on access to those members.

Data Accessor Methods

In the Circle example, we declared the circle radius to be a public

field. The Circle class is one in which it may well be reasonable to

keep that field publicly accessible; it is a simple enough class, with

no dependencies between its fields. On the other hand, our current

implementation of the class allows a Circle object to have a negative

radius, and circles with negative radii should simply not exist. As long

as the radius is stored in a public field, however, any programmer can

set the field to any value she wants, no matter how unreasonable. The

only solution is to restrict the programmer’s direct access to the field

and define public methods that provide indirect access to the field.

Providing public methods to read and write a field is not the same as

making the field itself public. The crucial difference is that methods

can perform error checking.

We might, for example, want to prevent Circle objects with negative

radii—these are obviously not sensible, but our current implementation

does not prohibit this. In Example 3-4, we

show how we might change the definition of Circle to prevent this.

This version of Circle declares the r field to be protected and

defines accessor methods named getRadius() and setRadius() to read

and write the field value while enforcing the restriction on negative

radius values. Because the r field is protected, it is directly (and

more efficiently) accessible to subclasses.

Example 3-4. The Circle class using data hiding and encapsulation

packageshapes;// Specify a package for the classpublicclassCircle{// The class is still public// This is a generally useful constant, so we keep it publicpublicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.14159;protecteddoubler;// Radius is hidden but visible to subclasses// A method to enforce the restriction on the radius// This is an implementation detail that may be of interest to subclassesprotectedvoidcheckRadius(doubleradius){if(radius<0.0)thrownewIllegalArgumentException("radius may not be negative.");}// The non-default constructorpublicCircle(doubler){checkRadius(r);this.r=r;}// Public data accessor methodspublicdoublegetRadius(){returnr;}publicvoidsetRadius(doubler){checkRadius(r);this.r=r;}// Methods to operate on the instance fieldpublicdoublearea(){returnPI*r*r;}publicdoublecircumference(){return2*PI*r;}}

We have defined the Circle class within a package named shapes; r is protected so any other classes in the shapes package

have direct access to that field and can set it however they like. The

assumption here is that all classes within the shapes package were

written by the same author or a closely cooperating group of authors, and

that the classes all trust each other not to abuse their privileged

level of access to each other’s implementation details.

Finally, the code that enforces the restriction against negative radius

values is itself placed within a protected method, checkRadius().

Although users of the Circle class cannot call this method, subclasses

of the class can call it and even override it if they want to change the

restrictions on the radius.

Note

It is a common convention in Java that data accessor methods begin with

the prefixes “get” and “set.” But if the field being accessed is of type

boolean, the get() method may be replaced with an equivalent method

that begins with “is”—the accessor method for a boolean

field named readable is typically called isReadable() instead of

getReadable().

Abstract Classes and Methods

In Example 3-4, we declared our Circle

class to be part of a package named shapes. Suppose we plan to

implement a number of shape classes: Rectangle, Square, Hexagon,

Triangle, and so on. We can give these shape classes our two basic

area() and circumference() methods. Now, to make it easy to work

with an array of shapes, it would be helpful if all our shape classes

had a common superclass, Shape. If we structure our class hierarchy

this way, every shape object, regardless of the actual type of shape it

represents, can be assigned to variables, fields, or array elements of

type Shape. We want the Shape class to encapsulate whatever features

all our shapes have in common (e.g., the area() and circumference()

methods). But our generic Shape class doesn’t represent any real kind

of shape, so it cannot define useful implementations of the methods.

Java handles this situation with abstract methods.

Java lets us define a method without implementing it by declaring the

method with the abstract modifier. An abstract method has no body;

it simply has a signature definition followed by a semicolon.2 Here are the rules about abstract methods and the

abstract classes that contain them:

-

Any class with an

abstractmethod is automaticallyabstractitself and must be declared as such. To fail to do so is a compilation error. -

An

abstractclass cannot be instantiated. -

A subclass of an

abstractclass can be instantiated only if it overrides each of theabstractmethods of its superclass and provides an implementation (i.e., a method body) for all of them. Such a class is often called a concrete subclass, to emphasize the fact that it is notabstract. -

If a subclass of an

abstractclass does not implement all theabstractmethods it inherits, that subclass is itselfabstractand must be declared as such. -

static,private, andfinalmethods cannot beabstract, because these types of methods cannot be overridden by a subclass. Similarly, afinalclass cannot contain anyabstractmethods. -

A class can be declared

abstracteven if it does not actually have anyabstractmethods. Declaring such a classabstractindicates that the implementation is somehow incomplete and is meant to serve as a superclass for one or more subclasses that complete the implementation. Such a class cannot be instantiated.

Note

The Classloader class that we will meet in

Chapter 11 is a good example of an abstract class

that does not have any abstract methods.

Let’s look at an example of how these rules work. If we define the

Shape class to have abstract area() and circumference() methods,

any subclass of Shape is required to provide implementations of these

methods so that it can be instantiated. In other words, every Shape

object is guaranteed to have implementations of these methods defined.

Example 3-5 shows how this might work. It

defines an abstract Shape class and two concrete subclasses of it.

Example 3-5. An abstract class and concrete subclasses

publicabstractclassShape{publicabstractdoublearea();// Abstract methods: notepublicabstractdoublecircumference();// semicolon instead of body.}classCircleextendsShape{publicstaticfinaldoublePI=3.14159265358979323846;protecteddoubler;// Instance datapublicCircle(doubler){this.r=r;}// ConstructorpublicdoublegetRadius(){returnr;}// Accessorpublicdoublearea(){returnPI*r*r;}// Implementations ofpublicdoublecircumference(){return2*PI*r;}// abstract methods.}classRectangleextendsShape{protecteddoublew,h;// Instance datapublicRectangle(doublew,doubleh){// Constructorthis.w=w;this.h=h;}publicdoublegetWidth(){returnw;}// Accessor methodpublicdoublegetHeight(){returnh;}// Another accessorpublicdoublearea(){returnw*h;}// Implementation ofpublicdoublecircumference(){return2*(w+h);}// abstract methods}

Each abstract method in Shape has a semicolon right after its

parentheses. They have no curly braces, and no method body is defined.

Using the classes defined in Example 3-5, we

can now write code such as:

Shape[]shapes=newShape[3];// Create an array to hold shapesshapes[0]=newCircle(2.0);// Fill in the arrayshapes[1]=newRectangle(1.0,3.0);shapes[2]=newRectangle(4.0,2.0);doubletotalArea=0;for(inti=0;i<shapes.length;i++)totalArea+=shapes[i].area();// Compute the area of the shapes

Notice two important points here:

-

Subclasses of

Shapecan be assigned to elements of an array ofShape. No cast is necessary. This is another example of a widening reference type conversion (discussed in Chapter 2). -

You can invoke the

area()andcircumference()methods for anyShapeobject, even though theShapeclass does not define a body for these methods. When you do this, the method to be invoked is found using virtual dispatch, which we met earlier. In our case this means that the area of a circle is computed using the method defined byCircle, and the area of a rectangle is computed using the method defined byRectangle.

Reference Type Conversions

Object references can be converted between different reference types. As with primitive types, reference type conversions can be widening conversions (allowed automatically by the compiler) or narrowing conversions that require a cast (and possibly a runtime check). In order to understand reference type conversions, you need to understand that reference types form a hierarchy, usually called the class hierarchy.

Every Java reference type extends some other type, known as its

superclass. A type inherits the fields and methods of its superclass

and then defines its own additional fields and methods. A special class named Object serves as the root of the class hierarchy in Java. All

Java classes extend Object directly or indirectly. The Object class

defines a number of special methods that are inherited (or overridden)

by all objects.

The predefined String class and the Point class we discussed earlier

in this chapter both extend Object. Thus, we can say that all String

objects are also Object objects. We can also say that all Point

objects are Object objects. The opposite is not true, however. We

cannot say that every Object is a String because, as we’ve just

seen, some Object objects are Point objects.

With this simple understanding of the class hierarchy, we can define the rules of reference type conversion:

-

An object reference cannot be converted to an unrelated type. The Java compiler does not allow you to convert a

Stringto aPoint, for example, even if you use a cast operator. -

An object reference can be converted to the type of its superclass or of any ancestor class. This is a widening conversion, so no cast is required. For example, a

Stringvalue can be assigned to a variable of typeObjector passed to a method where anObjectparameter is expected.

Note

No conversion is actually performed; the object is simply treated as if it were an instance of the superclass. This is a simple form of the Liskov substitution principle, after Barbara Liskov, the computer scientist who first explicitly formulated it.

-

An object reference can be converted to the type of a subclass, but this is a narrowing conversion and requires a cast. The Java compiler provisionally allows this kind of conversion, but the Java interpreter checks at runtime to make sure it is valid. Only cast a reference to the type of a subclass if you are sure, based on the logic of your program, that the object is actually an instance of the subclass. If it is not, the interpreter throws a