Chapter 8. Working with Java Collections

This chapter introduces Java’s interpretation of fundamental data structures, known as the Java Collections. These abstractions are core to many (if not most) programming types, and form an essential part of any programmer’s basic toolkit. Accordingly, this is one of the most important chapters of the entire book, and provides a toolkit that is essential to virtually all Java programmers.

In this chapter, we will introduce the fundamental interfaces and the type hierarchy, show how to use them, and discuss aspects of their overall design. Both the “classic” approach to handling the Collections and the newer approach (using the Streams API and the lambda expressions functionality introduced in Java 8) will be covered.

Introduction to Collections API

The Java Collections are a set of generic interfaces that describe the most common forms of data structure. Java ships with several implementations of each of the classic data structures, and because the types are represented as interfaces, it is very possible for development teams to develop their own, specialized implementations of the interfaces for use in their own projects.

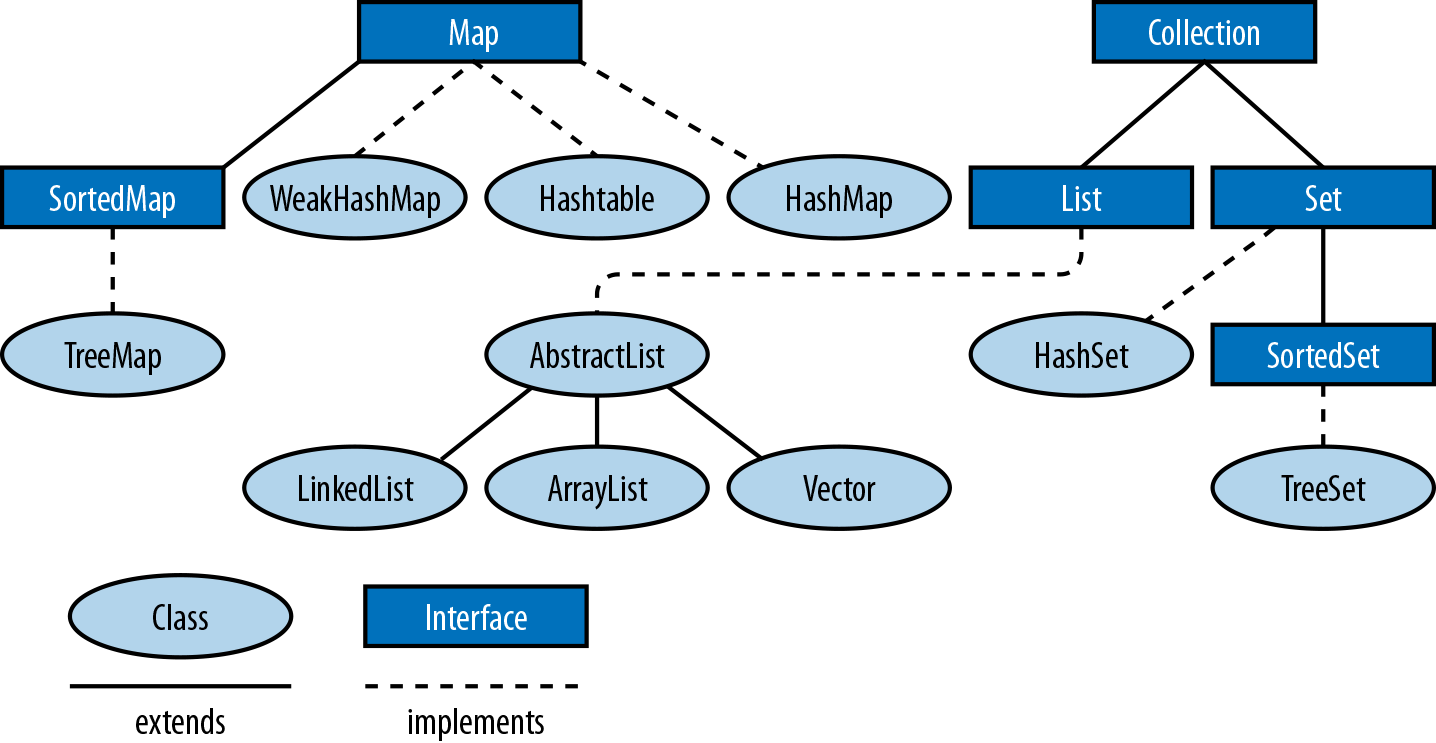

The Java Collections define two fundamental types of data structures. A

Collection is a grouping of objects, while a Map is a set of

mappings, or associations, between objects. The basic layout of the Java

Collections is shown in Figure 8-1.

Within this basic description, a Set is a type of Collection with no

duplicates, and a List is a Collection in which the elements are

ordered (but may contain duplicates).

Figure 8-1. Collections classes and inheritance

SortedSet and SortedMap are specialized sets and maps that maintain

their elements in a sorted order.

Collection, Set, List, Map, SortedSet, and SortedMap are all

interfaces, but the java.util package also defines various concrete

implementations, such as lists based on arrays and linked lists, and

maps and sets based on hash tables or binary trees. Other important

interfaces are Iterator and Iterable, which allow you to loop

through the objects in a collection, as we will see later on.

The Collection Interface

Collection<E> is a parameterized interface that represents a generalized grouping of objects of type E. We can create a collection of any kind of reference type.

Note

To work properly with the expectations of collections, you must take care when defining hashCode() and equals() methods, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Methods are defined for adding and removing objects from the group, testing an object for membership in the group, and iterating through all elements in the group. Additional methods return the elements of the group as an array and return the size of the collection.

Note

The grouping within a Collection may or may not allow duplicate

elements and may or may not impose an ordering on the elements.

The Java Collections Framework provides Collection because it defines

the features shared by all common forms of data structure. The JDK

ships Set, List, and Queue as subinterfaces of Collection.

The following code illustrates the operations you can perform on

Collection objects:

// Create some collections to work with.Collection<String>c=newHashSet<>();// An empty set// We'll see these utility methods later. Be aware that there are// some subtleties to watch out for when using themCollection<String>d=Arrays.asList("one","two");Collection<String>e=Collections.singleton("three");// Add elements to a collection. These methods return true// if the collection changes, which is useful with Sets that// don't allow duplicates.c.add("zero");// Add a single elementc.addAll(d);// Add all of the elements in d// Copy a collection: most implementations have a copy constructorCollection<String>copy=newArrayList<String>(c);// Remove elements from a collection.// All but clear return true if the collection changes.c.remove("zero");// Remove a single elementc.removeAll(e);// Remove a collection of elementsc.retainAll(d);// Remove all elements that are not in dc.clear();// Remove all elements from the collection// Querying collection sizebooleanb=c.isEmpty();// c is now empty, so trueints=c.size();// Size of c is now 0.// Restore collection from the copy we madec.addAll(copy);// Test membership in the collection. Membership is based on the equals// method, not the == operator.b=c.contains("zero");// trueb=c.containsAll(d);// true// Most Collection implementations have a useful toString() methodSystem.out.println(c);// Obtain an array of collection elements. If the iterator guarantees// an order, this array has the same order. The array is a copy, not a// reference to an internal data structure.Object[]elements=c.toArray();// If we want the elements in a String[], we must pass one inString[]strings=c.toArray(newString[c.size()]);// Or we can pass an empty String[] just to specify the type and// the toArray method will allocate an array for usstrings=c.toArray(newString[0]);

Remember that you can use any of the methods shown here with any Set,

List, or Queue. These subinterfaces may impose membership

restrictions or ordering constraints on the elements of the collection

but still provide the same basic methods.

Note

Methods such as addAll(), retainAll(), clear(), and remove() that

alter the collection were conceived of as optional parts of the API.

Unfortunately, they were specified a long time ago, when the received

wisdom was to indicate the absence of an optional method by throwing

UnsupportedOperationException. Accordingly, some implementations

(notably read-only forms) may throw this unchecked exception.

Collection, Map, and their subinterfaces do not extend the interfaces

Cloneable or Serializable. All of the collection and

map implementation classes provided in the Java Collections Framework,

however, do implement these interfaces.

Some collection implementations place restrictions on the elements that

they can contain. An implementation might prohibit null as an element,

for example. And EnumSet restricts membership to the values of a

specified enumerated type.

Attempting to add a prohibited element to a collection always throws an

unchecked exception such as NullPointerException or

ClassCastException. Checking whether a collection contains a

prohibited element may also throw such an exception, or it may simply

return false.

The Set Interface

A set is a collection of objects that does not allow duplicates: it

may not contain two references to the same object, two references to

null, or references to two objects a and b such that

a.equals(b). Most general-purpose Set implementations impose no

ordering on the elements of the set, but ordered sets are not prohibited

(see SortedSet and LinkedHashSet). Sets are further distinguished

from ordered collections like lists by the general expectation that they

have an efficient contains method that runs in constant or

logarithmic time.

Set defines no additional methods beyond those defined by

Collection but places additional restrictions on those methods. The

add() and addAll() methods of a Set are required to enforce the

no-duplicates rules: they may not add an element to the Set if the set

already contains that element. Recall that the add() and addAll()

methods defined by the Collection interface return true if the call

resulted in a change to the collection and false if it did not. This

return value is relevant for Set objects because the no-duplicates

restriction means that adding an element does not always result in a

change to the set.

Table 8-1 lists the implementations of the

Set interface and summarizes their internal representation, ordering

characteristics, member restrictions, and the performance of the basic

add(), remove(), and contains operations as well as iteration

performance. You can read more about each class in the reference

section. Note that CopyOnWriteArraySet is in the

java.util.concurrent package; all the other implementations are part

of java.util. Also note that java.util.BitSet is not a Set

implementation. This legacy class is useful as a compact and efficient

list of boolean values but is not part of the Java Collections

Framework.

| Class | Internal representation | Since | Element order | Member restric-tions | Basic opera-tions | Iteration perfor-mance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hashtable |

1.2 |

None |

None |

O(1) |

O(capacity) |

Best general-purpose implementation. |

|

Linked hashtable |

1.2 |

Insertion order |

None |

O(1) |

O(n) |

Preserves insertion order. |

|

Bit fields |

5.0 |

Enum declaration |

Enum values |

O(1) |

O(n) |

Holds non- |

|

Red-black tree |

1.2 |

Sorted ascending |

Comparable |

O(log(n)) |

O(n) |

|

|

Array |

5.0 |

Insertion order |

None |

O(n) |

O(n) |

Threadsafe without synchronized methods. |

The TreeSet implementation uses a red-black tree data structure to

maintain a set that is iterated in ascending order according to the

natural ordering of Comparable objects or according to an ordering

specified by a Comparator object. TreeSet actually implements the

SortedSet interface, which is a subinterface of Set.

The SortedSet interface offers several interesting methods that take

advantage of its sorted nature. The following code illustrates:

publicstaticvoidtestSortedSet(String[]args){// Create a SortedSetSortedSet<String>s=newTreeSet<>(Arrays.asList(args));// Iterate set: elements are automatically sortedfor(Stringword:s){System.out.println(word);}// Special elementsStringfirst=s.first();// First elementStringlast=s.last();// Last element// all elements but firstSortedSet<String>tail=s.tailSet(first+'\0');System.out.println(tail);// all elements but lastSortedSet<String>head=s.headSet(last);System.out.println(head);SortedSet<String>middle=s.subSet(first+'\0',last);System.out.println(middle);}

Warning

The addition of \0 characters is needed because the tailSet() and

related methods use the successor of an element, which for strings is

the string value with a NULL character (ASCII code 0) appended.

From Java 9 onward, the API has also been upgraded with a helper static method on the Set interface, like this:

Set<String>set=Set.of("Hello","World");

This API has several overloads that each take a fixed number of arguments, and also a varargs overload. The latter is used for the case where arbitarily many elements are wanted in the set, and falls back to the standard varargs mechanism (marshaling the elements into an array before the call).

The List Interface

A List is an ordered collection of objects. Each element of a list

has a position in the list, and the List interface defines methods to

query or set the element at a particular position, or index. In this

respect, a List is like an array whose size changes as needed to

accommodate the number of elements it contains. Unlike sets, lists allow

duplicate elements.

In addition to its index-based get() and set() methods, the List

interface defines methods to add or remove an element at a particular

index and also defines methods to return the index of the first or last

occurrence of a particular value in the list. The add() and remove()

methods inherited from Collection are defined to append to the list

and to remove the first occurrence of the specified value from the list.

The inherited addAll() appends all elements in the specified

collection to the end of the list, and another version inserts the

elements at a specified index. The retainAll() and removeAll()

methods behave as they do for any Collection, retaining or removing

multiple occurrences of the same value, if needed.

The List interface does not define methods that operate on a range of

list indexes. Instead, it defines a single subList() method that

returns a List object that represents just the specified range of the

original list. The sublist is backed by the parent list, and any changes

made to the sublist are immediately visible in the parent list. Examples

of subList() and the other basic List manipulation methods are shown

here:

// Create lists to work withList<String>l=newArrayList<String>(Arrays.asList(args));List<String>words=Arrays.asList("hello","world");List<String>words2=List.of("hello","world");// Querying and setting elements by indexStringfirst=l.get(0);// First element of listStringlast=l.get(l.size-1);// Last element of listl.set(0,last);// The last shall be first// Adding and inserting elements. add can append or insertl.add(first);// Append the first word at end of listl.add(0,first);// Insert first at the start of the list againl.addAll(words);// Append a collection at the end of the listl.addAll(1,words);// Insert collection after first word// Sublists: backed by the original listList<String>sub=l.subList(1,3);// second and third elementssub.set(0,"hi");// modifies 2nd element of l// Sublists can restrict operations to a subrange of backing listStrings=Collections.min(l.subList(0,4));Collections.sort(l.subList(0,4));// Independent copies of a sublist don't affect the parent list.List<String>subcopy=newArrayList<String>(l.subList(1,3));// Searching listsintp=l.indexOf(last);// Where does the last word appear?p=l.lastIndexOf(last);// Search backward// Print the index of all occurrences of last in l. Note subListintn=l.size();p=0;do{// Get a view of the list that includes only the elements we// haven't searched yet.List<String>list=l.subList(p,n);intq=list.indexOf(last);if(q==-1)break;System.out.printf("Found '%s' at index %d%n",last,p+q);p+=q+1;}while(p<n);// Removing elements from a listl.remove(last);// Remove first occurrence of the elementl.remove(0);// Remove element at specified indexl.subList(0,2).clear();// Remove a range of elements using subListl.retainAll(words);// Remove all but elements in wordsl.removeAll(words);// Remove all occurrences of elements in wordsl.clear();// Remove everything

Foreach loops and iteration

One very important way of working with collections is to process each

element in turn, an approach known as iteration. This is an older way

of looking at data structures, but is still very useful (especially for

small collections of data) and is easy to understand. This approach

fits naturally with the for loop, as shown in this bit of code, and is

easiest to illustrate using a List:

ListCollection<String>c=newArrayList<String>();// ... add some Strings to cfor(Stringword:c){System.out.println(word);}

The sense of the code should be clear—it takes the elements of c one

at a time and uses them as a variable in the loop body. More formally,

it iterates through the elements of an array or collection (or any

object that implements java.lang.Iterable). On each iteration it

assigns an element of the array or Iterable object to the loop

variable you declare and then executes the loop body, which typically

uses the loop variable to operate on the element. No loop counter or

Iterator object is involved; the loop performs the iteration

automatically, and you need not concern yourself with correct

initialization or termination of the loop.

This type of for loop is often referred to as a foreach loop.

Let’s see how it works. The following bit of code shows a rewritten (and

equivalent) for loop, with the method calls explicitly shown:

// Iteration with a for loopfor(Iterator<String>i=c.iterator();i.hasNext();){System.out.println(i.next());}

The Iterator object, i, is produced from the collection, and used

to step through the collection one item at a time. It can also be used

with while loops:

//Iterate through collection elements with a while loop.//Some implementations (such as lists) guarantee an order of iteration//Others make no guarantees.Iterator<String>iterator()=c.iterator();while(iterator.hasNext()){System.out.println(iterator.next());}

Here are some more things you should know about the syntax of the foreach loop:

-

As noted earlier,

expressionmust be either an array or an object that implements thejava.lang.Iterableinterface. This type must be known at compile time so that the compiler can generate appropriate looping code. -

The type of the array or

Iterableelements must be assignment-compatible with the type of the variable declared in thedeclaration. If you use anIterableobject that is not parameterized with an element type, the variable must be declared as anObject. -

The

declarationusually consists of just a type and a variable name, but it may include afinalmodifier and any appropriate annotations (see Chapter 4). Usingfinalprevents the loop variable from taking on any value other than the array or collection element the loop assigns it and serves to emphasize that the array or collection cannot be altered through the loop variable. -

The loop variable of the foreach loop must be declared as part of the loop, with both a type and a variable name. You cannot use a variable declared outside the loop as you can with the

forloop.

To understand in detail how the foreach loop works with collections, we

need to consider two interfaces, java.util.Iterator and

java.lang.Iterable:

publicinterfaceIterator<E>{booleanhasNext();Enext();voidremove();}

Iterator defines a way to iterate through the elements of a collection

or other data structure. It works like this: while there are more

elements in the collection (hasNext() returns true), call next to

obtain the next element of the collection. Ordered collections, such as

lists, typically have iterators that guarantee that they’ll return

elements in order. Unordered collections like Set simply guarantee

that repeated calls to next() return all elements of the set without

omissions or duplications but do not specify an ordering.

Warning

The next() method of Iterator performs two functions—it advances

through the collection and also returns the old head value of the

collection. This combination of operations can cause problems when you are programming in a functional

or immutable style, as it mutates the underlying collection.

The Iterable interface was introduced to make the foreach loop work.

A class implements this interface in order to advertise that it is able

to provide an Iterator to anyone interested:

publicinterfaceIterable<E>{java.util.Iterator<E>iterator();}

If an object is Iterable<E>, that means that it has an

iterator() method that returns an Iterator<E>, which has a next()

method that returns an object of type E.

Note

If you use the foreach loop with an Iterable<E>, the loop

variable must be of type E or a superclass or interface.

For example, to iterate through the elements of a List<String>, the

variable must be declared String or its superclass Object, or one of

the interfaces it implements: CharSequence, Comparable, or

Serializable.

Random access to Lists

A general expectation of List implementations is that they can be

efficiently iterated, typically in time proportional to the size of the

list. Lists do not all provide efficient random access to the elements

at any index, however. Sequential-access lists, such as the LinkedList

class, provide efficient insertion and deletion operations at the

expense of random-access performance. Implementations that provide

efficient random access implement the RandomAccess marker interface,

and you can test for this interface with instanceof if you need to

ensure efficient list manipulations:

// Arbitrary list we're passed to manipulateList<?>l=...;// Ensure we can do efficient random access. If not, use a copy// constructor to make a random-access copy of the list before// manipulating it.if(!(linstanceofRandomAccess))l=newArrayList<?>(l);

The Iterator returned by the iterator() method of a List iterates

the list elements in the order that they occur in the list. List

implements Iterable, and lists can be iterated with a foreach loop

just as any other collection can.

To iterate just a portion of a list, you can use the subList() method

to create a sublist view:

List<String>words=...;// Get a list to iterate// Iterate just all elements of the list but the firstfor(Stringword:words.subList(1,words.size))System.out.println(word);

Table 8-1 summarizes the five

general-purpose List implementations in the Java platform. Vector

and Stack are legacy implementations and should not be used.

CopyOnWriteArrayList is part of the java.util.concurrent package

and is only really suitable for multithreaded use cases.

| Class | Representation | Since | Random access | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Array |

1.2 |

Yes |

Best all-around implementation. |

|

Double-linked list |

1.2 |

No |

Efficient insertion and deletion. |

|

Array |

5.0 |

Yes |

Threadsafe; fast traversal, slow modification. |

|

Array |

1.0 |

Yes |

Legacy class; synchronized methods. Do not use. |

|

Array |

1.0 |

Yes |

Extends |

The Map Interface

A map is a set of key objects and a mapping from each member of

that set to a value object. The Map interface defines an API for

defining and querying mappings. Map is part of the Java Collections

Framework, but it does not extend the Collection interface, so a Map

is a little-c collection, not a big-C Collection. Map is a

parameterized type with two type variables. Type variable K represents

the type of keys held by the map, and type variable V represents the

type of the values that the keys are mapped to. A mapping from String

keys to Integer values, for example, can be represented with a

Map<String,Integer>.

The most important Map methods are put(), which defines a key/value

pair in the map; get(), which queries the value associated with a

specified key; and remove(), which removes the specified key and its

associated value from the map. The general performance expectation for

Map implementations is that these three basic methods are quite

efficient: they should usually run in constant time and certainly no

worse than in logarithmic time.

An important feature of Map is its support for “collection views.”

These can be summarized simply:

-

A

Mapis not aCollection -

The keys of a

Mapcan be viewed as aSet -

The values can be viewed as a

Collection -

The mappings can be viewed as a

SetofMap.Entryobjects.

Note

Map.Entry is a nested interface defined within Map: it simply

represents a single key/value pair.

The following sample code shows the get(), put(), remove(), and

other methods of a Map and also demonstrates some common uses of the

collection views of a Map:

// New, empty mapMap<String,Integer>m=newHashMap<>();// Immutable Map containing a single key/value pairMap<String,Integer>singleton=Collections.singletonMap("test",-1);// Note this rarely used syntax to explicitly specify the parameter// types of the generic emptyMap method. The returned map is immutableMap<String,Integer>empty=Collections.<String,Integer>emptyMap();// Populate the map using the put method to define mappings// from array elements to the index at which each element appearsString[]words={"this","is","a","test"};for(inti=0;i<words.length;i++){m.put(words[i],i);// Note autoboxing of int to Integer}// Each key must map to a single value. But keys may map to the// same valuefor(inti=0;i<words.length;i++){m.put(words[i].toUpperCase(),i);}// The putAll() method copies mappings from another Mapm.putAll(singleton);// Query the mappings with the get() methodfor(inti=0;i<words.length;i++){if(m.get(words[i])!=i)thrownewAssertionError();}// Key and value membership testingm.containsKey(words[0]);// truem.containsValue(words.length);// false// Map keys, values, and entries can be viewed as collectionsSet<String>keys=m.keySet();Collection<Integer>values=m.values();Set<Map.Entry<String,Integer>>entries=m.entrySet();// The Map and its collection views typically have useful// toString methodsSystem.out.printf("Map: %s%nKeys: %s%nValues: %s%nEntries: %s%n",m,keys,values,entries);// These collections can be iterated.// Most maps have an undefined iteration order (but see SortedMap)for(Stringkey:m.keySet())System.out.println(key);for(Integervalue:m.values())System.out.println(value);// The Map.Entry<K,V> type represents a single key/value pair in a mapfor(Map.Entry<String,Integer>pair:m.entrySet()){// Print out mappingsSystem.out.printf("'%s' ==> %d%n",pair.getKey(),pair.getValue());// And increment the value of each Entrypair.setValue(pair.getValue()+1);}// Removing mappingsm.put("testing",null);// Mapping to null can "erase" a mapping:m.get("testing");// Returns nullm.containsKey("testing");// Returns true: mapping still existsm.remove("testing");// Deletes the mapping altogetherm.get("testing");// Still returns nullm.containsKey("testing");// Now returns false.// Deletions may also be made via the collection views of a map.// Additions to the map may not be made this way, however.m.keySet().remove(words[0]);// Same as m.remove(words[0]);// Removes one mapping to the value 2 - usually inefficient and of// limited usem.values().remove(2);// Remove all mappings to 4m.values().removeAll(Collections.singleton(4));// Keep only mappings to 2 & 3m.values().retainAll(Arrays.asList(2,3));// Deletions can also be done via iteratorsIterator<Map.Entry<String,Integer>>iter=m.entrySet().iterator();while(iter.hasNext()){Map.Entry<String,Integer>e=iter.next();if(e.getValue()==2)iter.remove();}// Find values that appear in both of two maps. In general, addAll()// and retainAll() with keySet() and values() allow union and// intersectionSet<Integer>v=newHashSet<>(m.values());v.retainAll(singleton.values());// Miscellaneous methodsm.clear();// Deletes all mappingsm.size();// Returns number of mappings: currently 0m.isEmpty();// Returns truem.equals(empty);// true: Maps implementations override equals

With the arrival of Java 9, the Map interface has also been enhanced with factory methods for spinning up collections easily:

Map<String,Double>capitals=Map.of("Barcelona",22.5,"New York",28.3);

The situation is a little more complicated as compared to Set and List, as the Map type has both keys and values, and Java does not allow more than one varargs parameter in a method declaration.

The solution is to have fixed argument size overloads, up to 10 entries and also to provide a new static method, entry(), that will construct an object to represent the key/value pair.

The code can then be written to use the varargs form like this:

Map<String,Double>capitals=Map.ofEntries(entry("Barcelona",22.5),entry("New York",28.3));

Note that the method name has to be different from of() due to the difference in type of the arguments—this is now a varargs method in Map.Entry.

The Map interface includes a variety of general-purpose and

special-purpose implementations, which are summarized in

Table 8-2. As always, complete details are

in the JDK’s documentation and javadoc. All classes in

Table 8-2 are in the java.util package

except ConcurrentHashMap and ConcurrentSkipListMap, which are

part of java.util.concurrent.

| Class | Representation | Since | null keys | null values | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hashtable |

1.2 |

Yes |

Yes |

General-purpose implementation. |

|

Hashtable |

5.0 |

No |

No |

General-purpose threadsafe

implementation; see |

|

Hashtable |

6.0 |

No |

No |

Specialized threadsafe

implementation; see |

|

Array |

5.0 |

No |

Yes |

Keys are instances of an enum. |

|

Hashtable plus list |

1.4 |

Yes |

Yes |

Preserves insertion or access order. |

|

Red-black tree |

1.2 |

No |

Yes |

Sorts by key value. Operations

are O(log(n)). See |

|

Hashtable |

1.4 |

Yes |

Yes |

Compares with |

|

Hashtable |

1.2 |

Yes |

Yes |

Doesn’t prevent garbage collection of keys. |

|

Hashtable |

1.0 |

No |

No |

Legacy class; synchronized methods. Do not use. |

|

Hashtable |

1.0 |

No |

No |

Extends |

The ConcurrentHashMap and ConcurrentSkipListMap classes of the

java.util.concurrent package implement the ConcurrentMap

interface of the same package. ConcurrentMap extends Map and

defines some additional atomic operations that are important in

multithreaded programming. For example, the putIfAbsent() method is

like put() but adds the key/value pair to the map only if the key is

not already mapped.

TreeMap implements the SortedMap interface, which extends Map to

add methods that take advantage of the sorted nature of the map.

SortedMap is quite similar to the SortedSet interface. The

firstKey() and lastKey() methods return the first and last keys in

the keySet(). And headMap(), tailMap(), and subMap() return a

restricted range of the original map.

The Queue and BlockingQueue Interfaces

A queue is an ordered collection of elements with methods for extracting elements, in order, from the head of the queue. Queue implementations are commonly based on insertion order as in first-in, first-out (FIFO) queues or last-in, first-out (LIFO) queues.

Note

LIFO queues are also known as stacks, and Java provides a Stack

class, but its use is strongly discouraged—instead, use implementations of

the Deque interface.

Other orderings are also possible: a priority queue orders its

elements according to an external Comparator object, or according to

the natural ordering of Comparable elements. Unlike a Set, Queue

implementations typically allow duplicate elements. Unlike List, the

Queue interface does not define methods for manipulating queue

elements at arbitrary positions. Only the element at the head of the

queue is available for examination. It is common for Queue

implementations to have a fixed capacity: when a queue is full, it is

not possible to add more elements. Similarly, when a queue is empty, it

is not possible to remove any more elements. Because full and empty

conditions are a normal part of many queue-based algorithms, the Queue

interface defines methods that signal these conditions with return

values rather than by throwing exceptions. Specifically, the peek()

and poll() methods return null to indicate that the queue is empty.

For this reason, most Queue implementations do not allow null

elements.

A blocking queue is a type of queue that defines blocking put()

and take() methods. The put() method adds an element to the queue,

waiting, if necessary, until there is space in the queue for the

element. And the take() method removes an element from the head of the

queue, waiting, if necessary, until there is an element to remove.

Blocking queues are an important part of many multithreaded algorithms,

and the BlockingQueue interface (which extends Queue) is defined as

part of the java.util.concurrent package.

Queues are not nearly as commonly used as sets, lists, and maps, except perhaps in certain multithreaded programming styles. In lieu of example code here, we’ll try to clarify the different possible queue insertion and removal operations.

Adding Elements to Queues

add()-

This

Collectionmethod simply adds an element in the normal way. In bounded queues, this method may throw an exception if the queue is full. offer()-

This

Queuemethod is likeadd()but returnsfalseinstead of throwing an exception if the element cannot be added because a bounded queue is full.BlockingQueuedefines a timeout version ofoffer()that waits up to a specified amount of time for space to become available in a full queue. Like the basic version of the method, it returnstrueif the element was inserted andfalseotherwise. put()-

This

BlockingQueuemethod blocks: if the element cannot be inserted because the queue is full,put()waits until some other thread removes an element from the queue, and space becomes available for the new element.

Removing Elements from Queues

remove()-

In addition to the

Collection.remove()method, which removes a specified element from the queue, theQueueinterface defines a no-argument version ofremove()that removes and returns the element at the head of the queue. If the queue is empty, this method throws aNoSuchElementException. poll()-

This

Queuemethod removes and returns the element at the head of the queue, likeremove()does, but returnsnullif the queue is empty instead of throwing an exception.BlockingQueuedefines a timeout version ofpoll()that waits up to a specified amount of time for an element to be added to an empty queue. take()-

This

BlockingQueuemethod removes and returns the element at the head of the queue. If the queue is empty, it blocks until some other thread adds an element to the queue. drainTo()-

This

BlockingQueuemethod removes all available elements from the queue and adds them to a specifiedCollection. It does not block to wait for elements to be added to the queue. A variant of the method accepts a maximum number of elements to drain.

Querying

In this context, querying refers to examining the element at the head without removing it from the queue.

element()-

This

Queuemethod returns the element at the head of the queue but does not remove that element from the queue. It throwsNoSuchElementExceptionif the queue is empty. peek()-

This

Queuemethod is likeelementbut returnsnullif the queue is empty.

Note

When using queues, it is usually a good idea to pick one particular

style of how to deal with a failure. For example, if you want

operations to block until they succeed, then choose put() and

take(). If you want to examine the return code of a method to see if

the queue operation suceeded, then offer() and poll() are an

appropriate choice.

The LinkedList class also implements Queue. It provides unbounded

FIFO ordering, and insertion and removal operations require constant

time. LinkedList allows null elements, although their use is

discouraged when the list is being used as a queue.

There are two other Queue implementations in the java.util package.

PriorityQueue orders its elements according to a Comparator or

orders Comparable elements according to the order defined by their

compareTo() methods. The head of a PriorityQueue is always the

smallest element according to the defined ordering. Finally,

ArrayDeque is a double-ended queue implementation. It is often used

when a stack implementation is needed.

The java.util.concurrent package also contains a number of

BlockingQueue implementations, which are designed for use in

multithreaded programing style; advanced versions that can remove the

need for synchronized methods are available.

Utility Methods

The java.util.Collections class is home to quite a few static utility

methods designed for use with collections. One important group of these

methods are the collection wrapper methods: they return a

special-purpose collection wrapped around a collection you specify. The

purpose of the wrapper collection is to wrap additional functionality

around a collection that does not provide it itself. Wrappers exist to

provide thread-safety, write protection, and runtime type checking.

Wrapper collections are always backed by the original collection,

which means that the methods of the wrapper simply dispatch to the

equivalent methods of the wrapped collection. This means that changes

made to the collection through the wrapper are visible through the

wrapped collection and vice versa.

The first set of wrapper methods provides threadsafe wrappers around

collections. Except for the legacy classes Vector and Hashtable, the

collection implementations in java.util do not have synchronized

methods and are not protected against concurrent access by multiple

threads. If you need threadsafe collections and don’t mind the

additional overhead of synchronization, create them with code like this:

List<String>list=Collections.synchronizedList(newArrayList<>());Set<Integer>set=Collections.synchronizedSet(newHashSet<>());Map<String,Integer>map=Collections.synchronizedMap(newHashMap<>());

A second set of wrapper methods provides collection objects through

which the underlying collection cannot be modified. They return a

read-only view of a collection: an UnsupportedOperationException will result from changing the collection’s content. These wrappers

are useful when you must pass a collection to a method that must not be

allowed to modify or mutate the content of the collection in any way:

List<Integer>primes=newArrayList<>();List<Integer>readonly=Collections.unmodifiableList(primes);// We can modify the list through primesprimes.addAll(Arrays.asList(2,3,5,7,11,13,17,19));// But we can't modify through the read-only wrapperreadonly.add(23);// UnsupportedOperationException

The java.util.Collections class also defines methods to operate on

collections. Some of the most notable are methods to sort and search the

elements of collections:

Collections.sort(list);// list must be sorted firstintpos=Collections.binarySearch(list,"key");

Here are some other interesting Collections methods:

// Copy list2 into list1, overwriting list1Collections.copy(list1,list2);// Fill list with Object oCollections.fill(list,o);// Find the largest element in Collection cCollections.max(c);// Find the smallest element in Collection cCollections.min(c);Collections.reverse(list);// Reverse listCollections.shuffle(list);// Mix up list

It is a good idea to familiarize yourself fully with the utility methods

in Collections and Arrays, as they can save you from writing your own

implementation of a common task.

Special-case collections

In addition to its wrapper methods, the java.util.Collections class

also defines utility methods for creating immutable collection

instances that contain a single element and other methods for creating

empty collections. singleton(), singletonList(), and

singletonMap() return immutable Set, List, and Map objects that

contain a single specified object or a single key/value pair. These

methods are useful when you need to pass a single object to a method

that expects a collection.

The Collections class also includes methods that return empty

collections. If you are writing a method that returns a collection, it

is usually best to handle the no-values-to-return case by returning an

empty collection instead of a special-case value like null:

Set<Integer>si=Collections.emptySet();List<String>ss=Collections.emptyList();Map<String,Integer>m=Collections.emptyMap();

Finally, nCopies() returns an immutable List that contains a

specified number of copies of a single specified object:

List<Integer>tenzeros=Collections.nCopies(10,0);

Arrays and Helper Methods

Arrays of objects and collections serve similar purposes. It is possible to convert from one to the other:

String[]a={"this","is","a","test"};// An array// View array as an ungrowable listList<String>l=Arrays.asList(a);// Make a growable copy of the viewList<String>m=newArrayList<>(l);// asList() is a varargs method so we can do this, too:Set<Character>abc=newHashSet<Character>(Arrays.asList('a','b','c'));// Collection defines the toArray method. The no-args version creates// an Object[] array, copies collection elements to it and returns it// Get set elements as an arrayObject[]members=set.toArray();// Get list elements as an arrayObject[]items=list.toArray();// Get map key objects as an arrayObject[]keys=map.keySet().toArray();// Get map value objects as an arrayObject[]values=map.values().toArray();// If you want the return value to be something other than Object[],// pass in an array of the appropriate type. If the array is not// big enough, another one of the same type will be allocated.// If the array is too big, the collection elements copied to it// will be null-filledString[]c=l.toArray(newString[0]);

In addition, there are a number of useful helper methods for working with Java’s arrays, which are included here for completeness.

The java.lang.System class defines an arraycopy() method that is

useful for copying specified elements in one array to a specified

position in a second array. The second array must be the same type as

the first, and it can even be the same array:

char[]text="Now is the time".toCharArray();char[]copy=newchar[100];// Copy 10 characters from element 4 of text into copy,// starting at copy[0]System.arraycopy(text,4,copy,0,10);// Move some of the text to later elements, making room for insertions// If target and source are the same,// this will involve copying to a temporarySystem.arraycopy(copy,3,copy,6,7);

There are also a number of useful static methods defined on the

Arrays class:

int[]intarray=newint[]{10,5,7,-3};// An array of integersArrays.sort(intarray);// Sort it in place// Value 7 is found at index 2intpos=Arrays.binarySearch(intarray,7);// Not found: negative return valuepos=Arrays.binarySearch(intarray,12);// Arrays of objects can be sorted and searched tooString[]strarray=newString[]{"now","is","the","time"};Arrays.sort(strarray);// sorted to: { "is", "now", "the", "time" }// Arrays.equals compares all elements of two arraysString[]clone=(String[])strarray.clone();booleanb1=Arrays.equals(strarray,clone);// Yes, they're equal// Arrays.fill initializes array elements// An empty array; elements set to 0byte[]data=newbyte[100];// Set them all to -1Arrays.fill(data,(byte)-1);// Set elements 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 to -2Arrays.fill(data,5,10,(byte)-2);

Arrays can be treated and manipulated as objects in Java. Given an

arbitrary object o, you can use code such as the following to find out

if the object is an array and, if so, what type of array it is:

Classtype=o.getClass();if(type.isArray()){ClasselementType=type.getComponentType();}

Java Streams and Lambda Expressions

One of the major reasons for introducing lambda expressions in Java 8 was to facilitate the overhaul of the Collections API to allow more modern programming styles to be used by Java developers. Until the release of Java 8, the handling of data structures in Java looked a little bit dated. Many languages now support a programming style that allows collections to be treated as a whole, rather than requiring them to be broken apart and iterated over.

In fact, many Java developers had taken to using alternative data structures libraries to achieve some of the expressivity and productivity that they felt was lacking in the Collections API. The key to upgrading the APIs was to introduce new classes and methods that would accept lambda expressions as parameters—to define what needed to be done, rather than precisely how. This is a conception of programming that comes from the functional style.

The introduction of the functional collections—which are called Java Streams to make clear their divergence from the older collections approach—is an important step forward.

A stream can be created from a collection simply by calling the stream() method on an existing collection.

Note

The desire to add new methods to existing interfaces was directly responsible for the new language feature referred to as default methods (see “Default Methods” for more details). Without this new mechanism, older implementations of the Collections interfaces would fail to compile under Java 8, and would fail to link if loaded into a Java 8 runtime.

However, the arrival of the Streams API does not erase history. The Collections API is deeply embedded in the Java world, and it is not functional. Java’s commitment to backward compatibility and to a rigid language grammar means that the Collections will never go away. Java code, even when written in a functional style, will never be full of boilerplate, and will never have the concise syntax that we see in languages such as Haskell or Scala.

This is part of the inevitable trade-off in language design—Java has retrofitted functional capabilities on top of an imperative design and base. This is not the same as designing for functional programming from the ground up. A more important question is: are the functional capabilities supplied from Java 8 onward what working programmers need to build their applications?

The rapid adoption of Java 8 over previous versions and the community reaction seem to indicate that the new features have been a success, and that they have provided what the ecosystem was looking for.

In this section, we will give a basic introduction to the use of Java streams and lambda expressions in the Java Collections. For a fuller treatment, see Java 8 Lambdas by Richard Warburton (O’Reilly).

Functional Approaches

The approach that Java 8 Streams wished to enable was derived from functional programming languages and styles. We met some of these key patterns in “Nonstatic Member Classes”—let’s reintroduce them and look at some examples of each.

Filter

The idiom applies a piece of code (that returns either true or false)

to each element in a collection, and builds up a new collection

consisting of those elements that “passed the test” (i.e., the bit of

code returned true when applied to the element).

For example, let’s look at some code to work with a collection of cats and pick out the tigers:

String[]input={"tiger","cat","TIGER","Tiger","leopard"};List<String>cats=Arrays.asList(input);Stringsearch="tiger";Stringtigers=cats.stream().filter(s->s.equalsIgnoreCase(search)).collect(Collectors.joining(", "));System.out.println(tigers);

The key piece is the call to filter(), which takes a lambda

expression. The lambda takes in a string and returns a Boolean value.

This is applied over the whole collection cats, and a new collection

is created, which only contains tigers (however they were capitalized).

The filter() method takes in an instance of the Predicate

interface, from the package java.util.function. This is a

functional interface, with only a single nondefault method, and so is a

perfect fit for a lambda expression.

Note the final call to collect(); this is an essential part of the

API and is used to “gather up” the results at the end of the lambda

operations. We’ll discuss it in more detail in the next section.

Predicate has some other very useful default methods, such as for

constructing combined predicates by using logic operations. For example,

if the tigers want to admit leopards into their group, this can be

represented by using the or() method:

Predicate<String>p=s->s.equalsIgnoreCase(search);Predicate<String>combined=p.or(s->s.equals("leopard"));Stringpride=cats.stream().filter(combined).collect(Collectors.joining(", "));System.out.println(pride);

Note that it’s much clearer if the Predicate<String> object p is explicitly created, so that the defaulted or() method can be called on it and the second lambda expression (which will also be automatically converted to a Predicate<String>) passed to it.

Map

The map idiom in Java 8 makes use of a new interface Function<T, R>

in the package java.util.function.

Like Predicate<T>, this is a functional interface, and so only has one nondefaulted method, apply().

The map idiom is about transforming a stream of one type into a stream of a potentially different type. This shows up in the API as the fact that Function<T, R> has two separate type parameters.

The name of the type parameter R indicates that this represents the return type of the function.

Let’s look at a code example that uses map():

List<Integer>namesLength=cats.stream().map(String::length).collect(Collectors.toList());System.out.println(namesLength);

This is called upon the previous cats variable (which is a Stream<String>) and applies the function String::length (a method reference) to each string in turn.

The result is a new stream—but of Integer this time.

Note that unlike the collections API, the map() method does not mutate the stream in place, but returns a new value.

This is key to the functional style as used here.

forEach

The map and filter idioms are used to create one collection from another. In languages that are strongly functional, this would be combined with requiring that the original collection was not affected by the body of the lambda as it touched each element. In computer science terms, this means that the lambda body should be “side-effect free.”

In Java, of course, we often need to deal with mutable data, so the Streams API provides a way to mutate elements as the collection is traversed—the forEach() method. This takes an argument of type Consumer<T>, which is a functional interface that is expected to operate by side effects (although whether it actually mutates the data or not is of lesser importance).

This means that the signature of lambdas that can be converted to Consumer<T> is (T t) → void.

Let’s look at a quick example of forEach():

List<String>pets=Arrays.asList("dog","cat","fish","iguana","ferret");pets.stream().forEach(System.out::println);

In this example, we are simply printing out each member of the

collection. However, we’re doing so by using a special kind of method

reference as a lambda expression. This type of method reference is

called a bound method reference, as it involves a specific object (in

this case, the object System.out, which is a static public field of

System). This is equivalent to the lambda expression:

s->System.out.println(s);

This is of course eligible for conversion to an instance of a type that

implements Consumer<? super String> as required by the method

signature.

Warning

Nothing prevents a map() or filter() call from mutating elements. It

is only a convention that they must not, but it’s one that every Java

programmer should adhere to.

There’s one final functional technique that we should look at before we move on. This is the practice of aggregating a collection down to a single value, and it’s the subject of our next section.

Reduce

Let’s look at the reduce() method. This implements the reduce idiom,

which is really a family of similar and related operations, some

referred to as fold, or aggregation, operations.

In Java 8, reduce() takes two arguments. These are the initial value,

which is often called the identity (or zero), and a function to apply

step by step. This function is of type BinaryOperator<T>, which is

another functional interface that takes in two arguments of the same

type, and returns another value of that type. This second argument to

reduce() is a two-argument lambda. reduce() is defined in the

javadoc like this:

Treduce(Tidentity,BinaryOperator<T>aggregator);

The easy way to think about the second argument to reduce() is that it

creates a “running total” as it runs over the stream. It starts by

combining the identity with the first element of the stream to produce

the first result, then combines that result with the second element of

the stream, and so on.

It can help to imagine that the implementation of reduce() works a bit

like this:

publicTreduce(Tidentity,BinaryOperator<T>aggregator){TrunningTotal=identity;for(Telement:myStream){runningTotal=aggregator.apply(runningTotal,element);}returnresult;}

Note

In practice, implementations of reduce() can be more sophisticated

than these, and can even execute in parallel if the data structure and

operations are amenable to this.

Let’s look at a quick example of a reduce() and calculate the sum of

some primes:

doublesumPrimes=((double)Stream.of(2,3,5,7,11,13,17,19,23).reduce(0,(x,y)->{returnx+y;}));System.out.println("Sum of some primes: "+sumPrimes);

In all of the examples we’ve met in this section, you may have noticed

the presence of a stream() method call on the List instance. This

is part of the evolution of the Collections—it was originally chosen

partly out of necessity, but has proved to be an excellent abstraction.

Let’s move on to discuss the Streams API in more detail.

The Streams API

The fundamental issue that caused the Java library designers to introduce the Streams API was the large number of implementations of the core collections interfaces present in the wild.

As these implementations predate Java 8 and lambdas, they would not have any of the methods corresponding to the new functional operations.

Worse still, as method names such as map() and filter() have never been part of the interface of the Collections, implementations may already have methods with those names.

To work around this problem, a new abstraction called a Stream was introduced.

The idea is that a Stream object can be generated from a collection object via the stream() method.

This Stream type, being new and under the control of the library designers, is then guaranteed to be free of collisions.

This then mitigates the risk of clash, as only Collections implementations that contained a stream() method would be affected.

A Stream object plays a similar role to an Iterator in the new approach to collections code.

The overall idea is for the developer to build up a sequence (or “pipeline”) of operations (such as map, filter, or reduce) that need to be applied to the collection as a whole.

The actual content of the operations will usually be expressed by using a

lambda expression for each operation.

At the end of the pipeline, the results usually need to be gathered up, or “materialized” back into an actual collection again.

This is done either by using a Collector or by finishing the pipeline with a “terminal method” such as reduce() that returns an actual value, rather than another stream.

Overall, the new approach to collections looks like

this:

stream()filter()map()collect()Collection->Stream->Stream->Stream->Collection

The Stream class behaves as a sequence of elements that are accessed

one at a time (although there are some types of streams that support

parallel access and can be used to process larger collections in a

naturally multithreaded way). In a similar way to an Iterator, the

Stream is used to take each item in turn.

As is usual for generic classes in Java, Stream is parameterized by a

reference type. However, in many cases, we actually want streams of

primitive types, especially ints and doubles. We cannot have

Stream<int>, so instead in java.util.stream there are special

(nongeneric) classes such as IntStream and DoubleStream. These are

known as primitive specializations of the Stream class and have

APIs that are very similar to the general Stream methods, except that

they use primitives where appropriate.

For example, in the reduce() example, we’re actually using primitive

specialization over most of the pipeline.

Lazy evaluation

In fact, streams are more general than iterators (or even collections), as streams do not manage storage for data. In earlier versions of Java, there was always a presumption that all of the elements of a collection existed (usually in memory). It was possible to work around this in a limited way by insisting on the use of iterators everywhere, and by having the iterators construct elements on the fly. However, this was neither very convenient nor that common.

By contrast, streams are an abstraction for managing data, rather than

being concerned with the details of storage. This makes it possible to

handle more subtle data structures than just finite collections. For

example, infinite streams can easily be represented by the Stream

interface, and can be used as a way to, for example, handle the set of

all square numbers. Let’s see how we could accomplish this using a

Stream:

publicclassSquareGeneratorimplementsIntSupplier{privateintcurrent=1;@OverridepublicsynchronizedintgetAsInt(){intthisResult=current*current;current++;returnthisResult;}}IntStreamsquares=IntStream.generate(newSquareGenerator());PrimitiveIterator.OfIntstepThrough=squares.iterator();for(inti=0;i<10;i++){System.out.println(stepThrough.nextInt());}System.out.println("First iterator done...");// We can go on as long as we like...for(inti=0;i<10;i++){System.out.println(stepThrough.nextInt());}

One significant consequence of modeling the infinite stream is that

methods like collect() won’t work. This is because we can’t

materialize the whole stream to a collection (we would run out of memory

before we created the infinite amount of objects we would need).

Instead, we must adopt a model in which we pull the elements out of the stream as we need them.

Essentially, we need a bit of code that returns the next element as we demand it.

The key technique that is used to accomplish this is lazy evaluation. This essentially means that values are not necessarily computed until they are needed.

Note

Lazy evaluation is a big change for Java, as until JDK 8 the value of an expression was always computed as soon as it was assigned to a variable (or passed into a method). This familiar model, where values are computed immediately, is called “eager evaluation” and it is the default behavior for evaluation of expressions in most mainstream programming languages.

Fortunately, lazy evaluation is largely a burden that falls on the

library writer, not the developer, and for the most part when using the

Streams API, Java developers don’t need to think closely about lazy

evaluation. Let’s finish off our discussion of streams by looking at an

extended code example using reduce(), and calculate the average word

length in some Shakespeare quotes:

String[]billyQuotes={"For Brutus is an honourable man","Give me your hands if we be friends and Robin shall restore amends","Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows"};List<String>quotes=Arrays.asList(billyQuotes);// Create a temporary collection for our wordsList<String>words=quotes.stream().flatMap(line->Stream.of(line.split(" +"))).collect(Collectors.toList());longwordCount=words.size();// The cast to double is only needed to prevent Java from using// integer divisiondoubleaveLength=((double)words.stream().map(String::length).reduce(0,(x,y)->{returnx+y;}))/wordCount;System.out.println("Average word length: "+aveLength);

In this example, we’ve introduced the flatMap() method. In our

example, it takes in a single string, line, and returns a stream of

strings, which is obtained by splitting up the line into its component

words. These are then “flattened” so that all the sub-streams from each

string are just combined into a single stream.

This has the effect of splitting up each quote into its component words,

and making one superstream out of them. We count the words by creating

the object words, essentially “pausing” halfway through the stream

pipeline, and rematerializing into a collection to get the number of

words before resuming our stream operations.

Once we’ve done that, we can proceed with the reduce, and add up the length of all the words, before dividing by the number of words that we have, across the quotes. Remember that streams are a lazy abstraction, so to perform an eager operation (like getting the size of a collection that backs a stream) we have to rematerialize the collection.

Streams utility default methods

Java 8 takes the opportunity to introduce a number of new methods to the Java Collections libraries. Now that the language supports default methods, it is possible to add new methods to the Collections without breaking backward compatibility.

Some of these methods are scaffold methods for the Streams

abstraction. These include methods such as Collection::stream,

Collection::parallelStream, and Collection::spliterator (which has

specialized forms List::spliterator and Set::spliterator).

Others are “missing methods,” such as Map::remove and Map::replace.

Some of these have been backported from the java.util.concurrent package where they were originally defined.

As an example, this includes the List::sort method, which is defined in List like this:

// Essentially just forwards to the helper method in Collectionspublicdefaultvoidsort(Comparator<?superE>c){Collections.<E>sort(this,c);}

Another example is the missing method Map::putIfAbsent, which has been

adopted from the ConcurrentMap interface in java.util.concurrent.

We also have the method Map::getOrDefault, which allows the programmer to avoid a lot of tedious null checks, by providing a value that should be returned if the key is not found.

The remaining methods provide additional functional techniques using the

interfaces of java.util.function:

Collection::removeIf-

This method takes a

Predicateand iterates internally over the collection, removing any elements that satisfy the predicate object. Map::forEach-

The single argument to this method is a lambda expression that takes two arguments (one of the key’s type and one of the value’s type) and returns

void. This is converted to an instance ofBiConsumerand is applied to each key/value pair in the map. Map::computeIfAbsent-

This takes a key and a lambda expression that maps the key type to the value type. If the specified key (first parameter) is not present in the map, then it computes a default value by using the lambda expression and puts it in the map.

(See also Map::computeIfPresent, Map::compute, and Map::merge.)

Summary

In this chapter, we’ve met the Java Collections libraries, and seen

how to start working with Java’s implementations of fundamental and

classic data structures. We’ve met the general Collection interface,

as well as List, Set, and Map. We’ve seen the original, iterative

way of handling collections, and also introduced the new Java 8 style,

based on ideas from fundamental programming.

Finally, we’ve met the Streams API and seen how the new approach is more general, and is able to express more subtle programming concepts than the classic approach.

We’ve only scratched the surface—the Streams API is a fundamental shift in how Java code is written and architected. There are inherent design limitations in how far the ideals of functional programming can be implemented in Java. Having said that, the possibility that Streams represent “just enough functional programming” is compelling.

Let’s move on. In the next chapter, we’ll continue looking at data, and common tasks like text processing, handling numeric data, and Java 8’s new date and time libraries.