Appendix A. Additional Tools

In this appendix, we will discuss two tools that used to ship as part of the JDK but are now either deprecated or only available as separate downloads. The tools are:

-

Nashorn

-

VisualVM

Nashorn is a fully compliant implementation of JavaScript and an accompanying shell and was first made available as part of Java 8, but is officially deprecated as of Java 11.

JVisualVM (often referred to as VisualVM) is a graphical tool, based on the Netbeans platform. It is used for monitoring JVMs and essentially acts as an equivalent, graphical aggregate of many of the tools featured in “Command-Line Tools”.

Introduction to Nashorn

In this section, we will assume some basic understanding of JavaScript. If you aren’t already familiar with basic JavaScript concepts, then Head First JavaScript by Michael Morrison (O’Reilly) is a good place to start.

If you recall the comparison between Java and JavaScript outlined in “Java Compared to JavaScript”, you know that the two languages are very different. It may, therefore, seem surprising that JavaScript should be able to run on top of the same virtual machine as Java.

Non-Java Languages on the JVM

In fact, there are a very large number of non-Java languages that run on the JVM—and some of them are a lot more unlike Java than JavaScript is. This is made possible by the fact that the Java language and JVM are only very loosely coupled, and only really interact via the definition of the class file format. This can be accomplished in two different ways:

-

The source language has an interpreter that has been implemented in Java. The interpreter runs on the JVM and executes programs written in the source language.

-

The source language ships with a compiler that produces class files from units of source language code. The resulting compiled class files are then directly executed on the JVM, usually with some additional language-specific runtime support.

With Java 8, Oracle has included Nashorn, a new JavaScript implementation that runs on the JVM. Nashorn is designed to replace the original JavaScript-on-the-JVM project—which was called Rhino (Nashorn is the German word for “rhino”).

Nashorn is a completely rewritten implementation and strives for easy interoperability with Java, high performance, and precise conformance to the JavaScript ECMA specifications. Nashorn was the first implementation of JavaScript to hit a perfect 100% on spec compliance and is already at least 20 times faster than Rhino on most workloads.

Nashorn takes the full-compilation approach—but with the added refinement that the compiler is inside the runtime, so that JavaScript source code is never compiled before program execution begins. This means that JavaScript that was not specifically written for Nashorn can still be easily deployed on the platform.

Note

Nashorn is unlike many other JVM languages (such as JRuby) in that it does not implement any form of interpreter. Nashorn always compiles JavaScript to JVM bytecode and executes the bytecode directly.

This is interesting from a technical perspective, but many developers are curious as to what role Nashorn is intended to play in the mature and well-established Java ecosystem. Let’s look at that role next.

Motivation

Nashorn serves several purposes within the Java and JVM ecosystem. First, it provides a viable environment for JavaScript developers to discover the power of the JVM. Second, it enables companies to continue to leverage their existing investment in Java technologies while additionally adopting JavaScript as a development language. Last, it provides a great engineering showcase for the advanced virtual machine technology present in the HotSpot Java Virtual Machine.

With the continued growth and adoption of JavaScript, broadening out from its traditional home in the browser to more general-purpose computing and the server side, Nashorn represents a great bridge between the existing rock-solid Java ecosystem and a promising wave of new technologies.

For now, let’s move on to discuss the mechanics of how Nashorn works, and how to get started with the platform. There are several different ways in which JavaScript code can be executed on Nashorn, and in the next section we’ll look at two of the most commonly used.

Executing JavaScript with Nashorn

In this section, we’ll be introducing the Nashorn environment, and discuss two different ways of executing JavaScript (both of which are present in the bin subdirectory of $JAVA_HOME):

jrunscript-

A simple script runner for executing JavaScript as .js files.

jjs-

A more full-featured shell—suitable for both running scripts and use as an interactive, read-eval-print-loop (REPL) environment for exploring Nashorn and its features.

Let’s start by looking at the basic runner, which is suitable for the majority of simple JavaScript applications.

Running from the Command Line

To run a JavaScript file called my_script.js with Nashorn, just use

the jrunscript command:

jrunscriptmy_script.js

jrunscript can also be used with different script engines than Nashorn

(see “Nashorn and javax.script” for more details on

script engines) and it provides a -l switch to specify them if needed:

jrunscript–lnashornmy_script.js

Note

With this switch, jrunscript can even run scripts in languages other

than JavaScript, provided a suitable script engine is available.

The basic runner is perfectly suitable for simple use cases, but it has

limitations and so for serious use we need a more capable execution

environment. This is provided by jjs, the Nashorn shell.

Using the Nashorn Shell

The Nashorn shell command is jjs. This can be used either

interactively, or non-interactively, as a drop-in replacement for

jrunscript.

The simplest JavaScript example is, of course, the classic “Hello World,” so let’s look at how we would achieve this in the interactive shell:

$jjsjjs>("Hello World!");HelloWorld!jjs>

Nashorn interoperability with Java can be easily handled from the shell. We’ll discuss this in full detail in “Calling Java from Nashorn”, but to give a first example, we can directly access Java classes and methods from JavaScript by using the fully qualified class name. As a concrete example, let’s access Java’s built-in regular expression support:

jjs>varpattern=java.util.regex.Pattern.compile("\\d+");jjs>varmyNums=pattern.split("a1b2c3d4e5f6");jjs>(myNums);[Ljava.lang.String;@10b48321jjs>(myNums[0]);a

Note

When we used the REPL to print out the JavaScript variable myNums, we

got the result [Ljava.lang.String;@10b48321—this is a tell-tale sign

that despite being represented in a JavaScript variable, myNums is

really a Java array of strings.

We’ll have a great deal more to say about interoperation between Nashorn

and Java later on, but first let’s discuss some of the additional

features of jjs. The general form of the jjs command is:

jjs[<options>]<files>[--<arguments>]

There are a number of options that can be passed to jjs—some of the

most common are:

-

-cpor-classpathindicates where additional Java classes can be found (to be used via theJava.typemechanism, as we’ll see later). -

-doeor-dump-on-errorwill produce a full error dump if Nashorn is forced to exit. -

-Jis used to pass options to the JVM. For example, if we want to increase the maximum memory available to the JVM:$jjs-J-Xmx4gjjs>java.lang.Runtime.getRuntime().maxMemory()3817799680 -

-strictcauses all script and functions to be run in JavaScript strict mode. This is a feature of JavaScript that was introduced with ECMAScript version 5, and is intended to reduce bugs and errors. Strict mode is recommended for all new development in JavaScript, and if you’re not familiar with it you should read up on it. -

-Dallows the developer to pass key/value pairs to Nashorn as system properties, in the usual way for the JVM. For example:$jjs–DmyKey=myValuejjs>java.lang.System.getProperty("myKey");myValue -

-vor-versionis the standard Nashorn version string. -

-fvor-fullversionprints the full Nashorn version string. -

-fxis used to execute a script as a JavaFx GUI application. This allows a JavaFX programmer to write a lot less boilerplate by making use of Nashorn.1

Nashorn and javax.script

Nashorn is not the first scripting language to ship with the Java platform.

The story starts with the inclusion of javax.script in Java 6, which provided a general interface for scripting language engines to interoperate with Java.

This general interface included concepts fundamental to scripting

languages, such as execution and compilation of scripting code (whether

a full script or just a single scripting statement in existing context).

In addition, a notion of binding between scripting

entities and Java was introduced, as well as script engine discovery.

Finally, javax.script provides optional support for invocation

(distinct from execution, as it allows intermediate code to be exported

from a scripting language’s runtime and used by the JVM runtime).

The example language provided was Rhino, but many other scripting languages were created to take advantage of the support provided. With Java 8, Rhino has been removed, and Nashorn is now the default scripting language supplied with the Java platform.

Introducing javax.script with Nashorn

Let’s look at a very simple example of how to use Nashorn to run JavaScript from Java:

importjavax.script.*;ScriptEngineManagerm=newScriptEngineManager();ScriptEnginee=m.getEngineByName("nashorn");try{e.eval("print('Hello World!');");}catch(finalScriptExceptionse){// ...}

The key concept here is ScriptEngine (obtained from a

ScriptEngineManager). This provides an empty scripting environment, to

which we can add code via the eval() method.

Tip

This is a very simple usage of eval()—however, we can easily imagine using it with the contents of a file loaded at runtime rather than a simple string as in this case.

The Nashorn engine provides a single global JavaScript object, so all

calls to eval() will execute on the same environment. This means that

we can make a series of eval() calls and build up JavaScript state in

the script engine. For example:

e.eval("i = 27;");e.put("j",15);e.eval("var z = i + j;");System.out.println(((Number)e.get("z")).intValue());// prints 42

Note that one of the problems with interacting with a scripting engine directly from Java is that we don’t normally have any information about what the types of values are.

Nashorn has a fairly close binding to much of the Java type system, however, so we need to be somewhat careful. When you are dealing with the JavaScript equivalents of primitive types, these will typically be converted to the appropriate (boxed) types when they are made visible to Java. For example, if we add the following line to our previous example:

System.out.println(e.get("z").getClass());

it’s easy to see that the value e.get("z") returns is of type

java.lang.Integer. If we change the code very slightly, like this:

e.eval("i = 27.1;");e.put("j",15);e.eval("var z = i + j;");System.out.println(e.get("z").getClass());

then this is sufficient to alter the type of the return value of

e.get("z") to type java.lang.Double, which marks out the distinction

between the two type systems. In other implementations of JavaScript,

these would both be treated as the numeric type (as JavaScript does not

define integer types). Nashorn, however, is more aware of the actual

type of the data.

Note

When dealing wih JavaScript, the Java programmer must be consciously aware of the difference between Java’s static typing and the dynamic nature of JavaScript types. Bugs can easily creep in otherwise.

In our examples, we have made use of the get() and put() methods on

the ScriptEngine. These allow us to directly get and set objects

within the global scope of the script being executed by a Nashorn

engine, without having to write or eval JavaScript code directly.

The javax.script API

Let’s round out this section with a brief description of some key

classes and interfaces in the javax.script API. This is a fairly small

API (six interfaces, five classes, and one exception) that has not

changed since its introduction in Java 6.

ScriptEngineManager-

The entry point into the scripting support. It maintains a list of available scripting implementations in this process. This is achieved via Java’s service provider mechanism, which is a very general way of managing extensions to the platform that may have wildly different implementations. By default, the only scripting extension available is Nashorn, although other scripting environments (such as Groovy or JRuby) can also be plugged in by the programmer.

ScriptEngine-

This class represents the script engine responsible for maintaining the environment in which our scripts will be interpreted.

Bindings-

This interface extends

Mapand provides a mapping between strings (the names of variables or other symbols) and scripting objects. Nashorn uses this to implement theScriptObjectMirrormechanism for interoperability.

In practice, most applications will deal with the relatively opaque

interface offered by methods on ScriptEngine such as eval(),

get(), and put(), but it’s useful to understand the basics of how

this interface plugs in to the overall scripting API.

Advanced Nashorn

Nashorn is a sophisticated programming environment that has been engineered to be a robust platform for deploying applications, and to have great interoperability with Java. Let’s look at some more advanced use cases for JavaScript-to-Java integration, and examine how this is achieved by looking inside Nashorn at some implementation details.

Calling Java from Nashorn

As each JavaScript object is compiled into an instance of a Java class, it’s perhaps not surprising that Nashorn has seamless integration with Java—despite the major difference in type systems and language features. However, there are still mechanisms that need to be in place to get the most out of this integration.

We’ve already seen that we can directly access Java classes and methods from Nashorn, for example:

$jjs-Dkey=valuejjs>(java.lang.System.getProperty("key"));value

Let’s take a closer look at the syntax and see how to achieve this support in Nashorn.

JavaClass and JavaPackage

From a Java perspective, the expression

java.lang.System.getProperty("key") reads as fully qualified access

to the static method getProperty() on java.lang.System. However, as

JavaScript syntax, this reads like a chain of property accesses,

starting from the symbol java—so let’s investigate how this symbol

behaves in the jjs shell:

jjs>(java);[JavaPackagejava]jjs>(java.lang.System);[JavaClassjava.lang.System]

So java is a special Nashorn object that gives access to the Java

system packages, which are given the JavaScript type JavaPackage,

and Java classes are represented by the JavaScript type JavaClass.

Any top-level package can be directly used as a package navigation

object, and subpackages can be assigned to a JavaScript object. This

allows syntax that gives concise access to Java classes:

jjs>varjuc=java.util.concurrent;jjs>varchm=newjuc.ConcurrentHashMap;

In addition to navigation by package objects, there is another object,

called Java, that has a number of useful methods on it. One of the

most important is the Java.type() method. This allows the user to

query the Java type system and get access to Java classes. For example:

jjs>varclz=Java.type("java.lang.System");jjs>(clz);[JavaClassjava.lang.System]

If the class is not present on the classpath (e.g., specified using the

-cp option to jjs), then a ClassNotFoundException is thrown (jjs

will wrap this in a Java RuntimeException):

jjs>varklz=Java.type("Java.lang.Zystem");java.lang.RuntimeException:java.lang.ClassNotFoundException:Java.lang.Zystem

The JavaScript JavaClass objects can be used like Java class objects

in most cases (they are a slightly different type—but just think of them

as the Nashorn-level mirror of a class object). For example, we can use

a JavaClass to create a new Java object directly from Nashorn:

jjs>varclz=Java.type("java.lang.Object");jjs>varobj=newclz;jjs>(obj);java.lang.Object@73d4cc9ejjs>(obj.hashCode());1943325854// Note that this syntax does not workjjs>varobj=clz.new;jjs>(obj);undefined

However, you should be slightly careful. The jjs environment

automatically prints out the results of expressions, which can lead to

some unexpected behavior:

jjs>varclz=Java.type("java.lang.System");jjs>clz.out.println("Baz!");Baz!null

The point here is that java.lang.System.out.println() has a return

type of void (i.e., it does not return a value). However, jjs

expects expressions to have a value and, in the absence of a variable

assignment, it will print it out. So the nonexistent return value of

println() is mapped to the JavaScript value null and printed out.

JavaScript functions and Java lambda expressions

The interoperability between JavaScript and Java goes to a very deep

level. We can even use JavaScript functions as anonymous implementations

of Java interfaces (or as lambda expressions). For example, let’s use a

JavaScript function as an instance of the Callable interface (which

represents a block of code to be called later). This has only a single

method, call(), which takes no parameters and returns void. In

Nashorn, we can use a JavaScript function as a lambda expression

instead:

jjs>varclz=Java.type("java.util.concurrent.Callable");jjs>(clz);[JavaClassjava.util.concurrent.Callable]jjs>varobj=newclz(function(){("Foo");});jjs>obj.call();Foo

The takeaway here is that, in Nashorn, there is

no distinction between a JavaScript function and a Java lambda

expression. Just as we saw in Java, the function is being automatically

converted to an object of the appropriate type. Let’s look at how we

might use a Java ExecutorService to execute some Nashorn JavaScript

on a Java thread pool:

jjs>varjuc=java.util.concurrent;jjs>varexc=juc.Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor();jjs>varclbl=newjuc.Callable(function(){\java.lang.Thread.sleep(10000);return1;});jjs>varfut=exc.submit(clbl);jjs>fut.isDone();falsejjs>fut.isDone();true

The reduction in boilerplate compared to the equivalent Java code (even with Java 8 lambdas) is quite staggering. However, there are some limitations caused by the manner in which lambdas have been implemented. For example:

jjs>varfut=exc.submit(function(){\java.lang.Thread.sleep(10000);return1;});java.lang.RuntimeException:java.lang.NoSuchMethodException:Can'tunambiguouslyselectbetweenfixedaritysignatures[(java.lang.Runnable),(java.util.concurrent.Callable)]ofthemethodjava.util.concurrent.Executors.FinalizableDelegatedExecutorService↵.submitforargumenttypes[jdk.nashorn.internal.objects.ScriptFunctionImpl]

The problem here is that the thread pool has an overloaded submit()

method. One version will accept a Callable and the other will accept a

Runnable. Unfortunately, the JavaScript function is eligible (as a

lambda expression) for conversion to both types. This is where the error

message about not being able to “unambiguously select” comes from. The

runtime could choose either, and can’t choose between them.

Nashorn’s JavaScript Language Extensions

As we’ve discussed, Nashorn is a completely conformant implementation of ECMAScript 5.1 (as JavaScript is known to the standards body). In addition, however, Nashorn also implements a number of JavaScript language syntax extensions, to make life easier for the developer. These extensions should be familiar to developers used to working with JavaScript, and quite a few of them duplicate extensions present in the Mozilla dialect of JavaScript. Let’s take a look at a few of the most common, and useful, extensions.

Single expression functions

Nashorn also supports another small syntax enhancement, designed to

make one-line functions that comprise a single expression easier to

read. If a function (named or anonymous) comprises just a single

expression, then the braces and return statements can be omitted. In the

example that follows, cube() and cube2() are completely equivalent

functions, but cube() is not normally legal JavaScript syntax:

functioncube(x)x*x*x;functioncube2(x){returnx*x*x;}(cube(3));(cube2(3));

Multiple catch clauses

JavaScript supports try, catch, and throw in a similar way to

Java.

However, standard JavaScript only allows a single catch clause

following a try block. There is no support for different catch clauses

handling different types of exception. Fortunately, there is already an

existing Mozilla syntax extension to offer this feature, and Nashorn

implements it as well, as shown in this example:

functionfnThatMightThrow(){if(Math.random()<0.5){thrownewTypeError();}else{thrownewError();}}try{fnThatMightThrow();}catch(eifeinstanceofTypeError){("Caught TypeError");}catch(e){("Caught some other error");}

Nashorn implements a few other nonstandard syntax extensions (and when

we met scripting mode for jjs, we saw some other useful syntax

innovations), but these are likely to be the most familiar and widely

used.

Under the Hood

As we have previously discussed, Nashorn works by compiling JavaScript programs directly to JVM bytecode, and then runs them just like any other class. It is this functionality that enables, for example, the straightforward representation of JavaScript functions as lambda expressions and their easy interoperability.

Let’s take a closer look at an earlier example, and see how we’re able to use a function as an anonymous implementation of a Java interface:

jjs>varclz=Java.type("java.util.concurrent.Callable");jjs>varobj=newclz(function(){("Foo");});jjs>(obj);jdk.nashorn.javaadapters.java.util.concurrent.Callable@290dbf45

This means that the actual type of the JavaScript object implementing

Callable is jdk.nashorn.javaadapters.java.util.concurrent.Callable.

This class is not shipped with Nashorn, of course. Instead, Nashorn

spins up dynamic bytecode to implement whatever interface is required

and just maintains the original name as part of the package structure

for readability.

Note

Remember that dynamic code generation is an essential part of Nashorn, and that all JavaScript code is compiled by Nashorn in Java bytecode and never interpreted.

One final note is that Nashorn’s insistence on 100% compliance with the spec does sometimes restrict the capabilities of the implementation. For example, consider printing out an object, like this:

jjs>varobj={foo:"bar",cat:2};jjs>(obj);[objectObject]

The ECMAScript specification requires the output to be

[object Object]—conformant implementations are not allowed to give

more useful detail (such as a complete list of the properties and values

contained in obj).

The Future of Nashorn and GraalVM

In the spring of 2018 Oracle announced the first release of GraalVM, a research project from Oracle Labs that may in time lead to the replacement of the current Java runtime (HotSpot). The research effort can be thought of as several separate but connected projects—it is a new JIT compiler for HotSpot, and also a new polyglot virtual machine. We will refer to the JIT compiler as Graal and the new VM as GraalVM.

The overall aim of the Graal effort is a rethinking of how compilation works for Java (and, in the case of GraalVM, for other languages as well). The basic observation that Graal starts from is very simple:

A compiler for Java transforms bytecode to machine code—in Java terms it is just a method that accepts a

byte[]and returns anotherbyte[]—so why wouldn’t we want to write the compiler in Java?

It turns out that there are some major advantages to writing a compiler in Java, rather than C++ (as the current compilers are):

-

No pointer handling bugs or crashes in the compiler

-

Able to use a Java toolchain for compiler development

-

Much lower barriers to entry for engineers to start working on the compiler

-

Much faster prototyping of new compiler features

-

The compiler could be made independent of HotSpot

Graal uses the new JVM Compiler Interface (JVMCI, delivered as JEP 243) to plug in to HotSpot, but it can also be used independently, and is a major part of GraalVM. The Graal technology is present and shipping as of Java 11, but it is still not considered fully production-ready for most use cases.

Longer term, Oracle is investing considerable resources in GraalVM, and toward a future that is truly polyglot. One initial step toward that future can be seen in GraalVM’s ability to fully embed non-Java languages in Java apps running inside GraalVM.

Note

Some of Graal’s capabilities can be thought of as a replacement for JSR 223 (Scripting for the Java Platform), but the Graal approach goes much further and deeper than comparable technologies in previous HotSpot capabilities.

The feature relies on GraalVM and the Graal SDK, which is provided as part of the GraalVM default classpath but should be included explicitly as a dependency in developer projects. In this simple example, we’re just calling a JavaScript function from Java:

importorg.graalvm.polyglot.Context;publicclassHelloPolyglot{publicstaticvoidmain(String[]args){System.out.println("Hello World: Java!");Contextcontext=Context.create();context.eval("js","print('Hello World: JavaScript!');");}}

A basic form of polyglot capability has existed since Java 6 and the introduction of the Scripting API.

It was significantly enhanced in Java 8 with the arrival of Nashorn, the invokedynamic-based implementation of JavaScript.

What sets the technology in GraalVM apart is that the ecosystem now explicitly includes an SDK and supporting tools for implementing multiple languages and having them running as co-equal and interoperable citizens on the underlying VM. Java becomes just one language (albeit an important one) among many that run on GraalVM.

The keys to this step forward are a component called Truffle and a simple, bare-bones VM, SubstrateVM, capable of executing JVM bytecode. Truffle provides a runtime and libraries for creating interpreters for non-Java languages. Once these interpreters are running, the Graal compiler will step in and compile the interpreters into fast machine code. Out of the box, GraalVM ships with JVM bytecode, JavaScript, and LLVM support—with additional languages expected to be added over time.

The GraalVM approach means that, for example, the JS runtime can call a foreign method on an object in a separate runtime, with seamless type conversion (at least for simple cases).

This ability to have fungibility across languages that have very different semantics and type systems has been discussed among JVM engineers for a very long time (at least 10 years), and with the arrival of GraalVM it has taken a very significant step toward the mainstream.

The significance of GraalVM for Nashorn is that Oracle has announced their intention to deprecate Nashorn and to eventually remove it from their distribution of Java. The intended replacement is the GraalVM version of JavaScript, but at the time of writing, there is no timescale for this, and Oracle has committed to not removing Nashorn until the replacement is fully ready.

VisualVM

VisualVM was introduced with Java 6, but has been removed from the main Java distribution package as of Java 9. This means that the only way to get a version for use on current Javas is to use the standalone version of VisualVM. However, even for Java 8 installations, the standalone is more up to date and a better choice for serious work. You can download the latest version from http://visualvm.java.net/.

After downloading VisualVM, ensure that the visualvm binary is added to your PATH (otherwise, on Java 8 you’ll get the JRE default binary).

Tip

jvisualvm is a replacement for the jconsole tool common in earlier

Java versions. The compatability plug-in available for visualvm

obsoletes jconsole; all installations using jconsole should migrate.

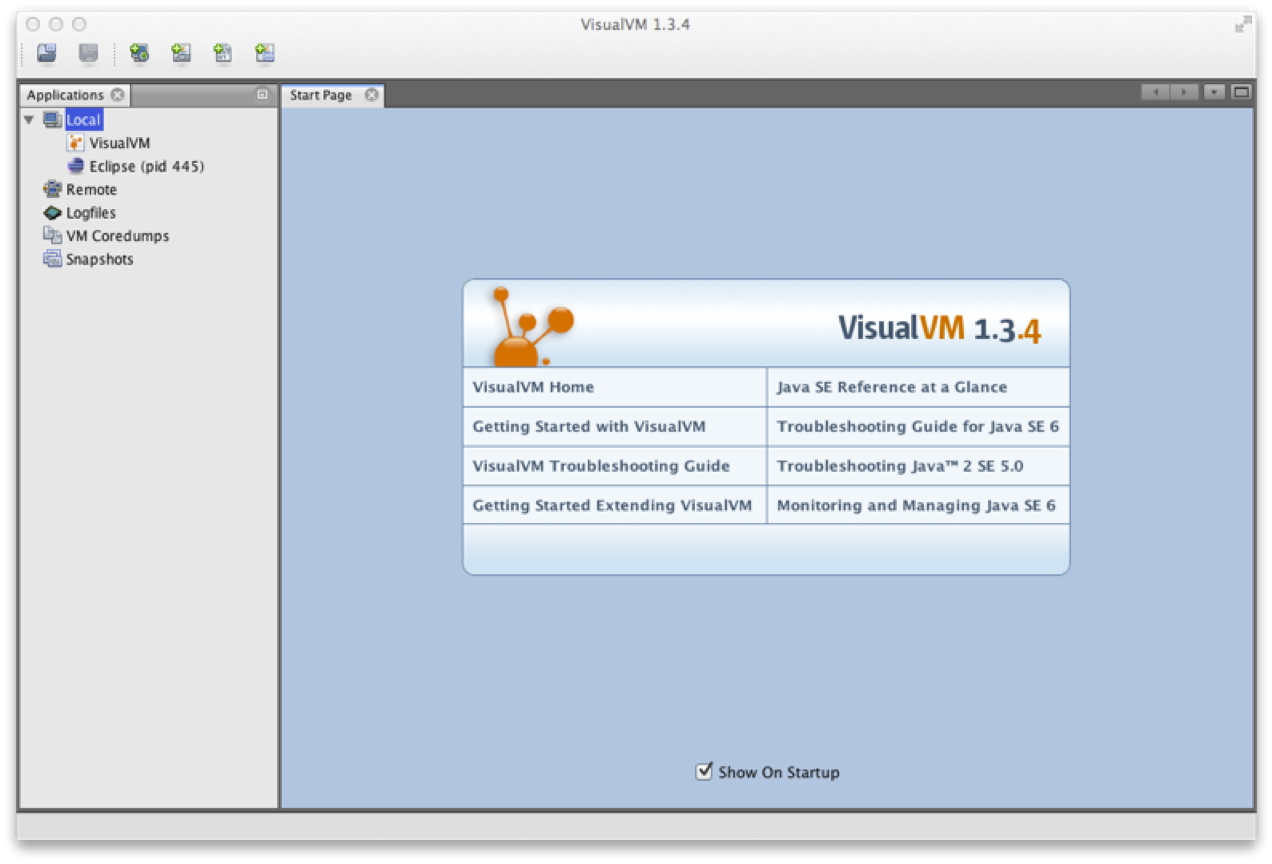

The first time you run VisualVM, it will calibrate your machine, so make sure that you aren’t running any other applications while calibration is being performed. After calibration, VisualVM will open to a screen like that shown in Figure A-1.

There are slightly different approaches for attaching VisualVM to a running process, depending on whether the process is local or remote.

Local processes are listed down the lefthand side of the screen. Double-click on one of the local processes and it will appear as a new tab on the righthand pane.

For a remote process, enter the hostname and a display name that will be used on the tab. The default port to connect to is 1099, but this can be changed.

In order to connect to a remote process, jstatd must be running on the

remote host (see the entry for jstatd in

“Command-Line Tools” for more details). If you are

connecting to an application server, you may find that the app server

vendor provides an equivalent capability to jstatd directly in the

server, and that jstatd is unnecessary.

Figure A-1. VisualVM welcome screen

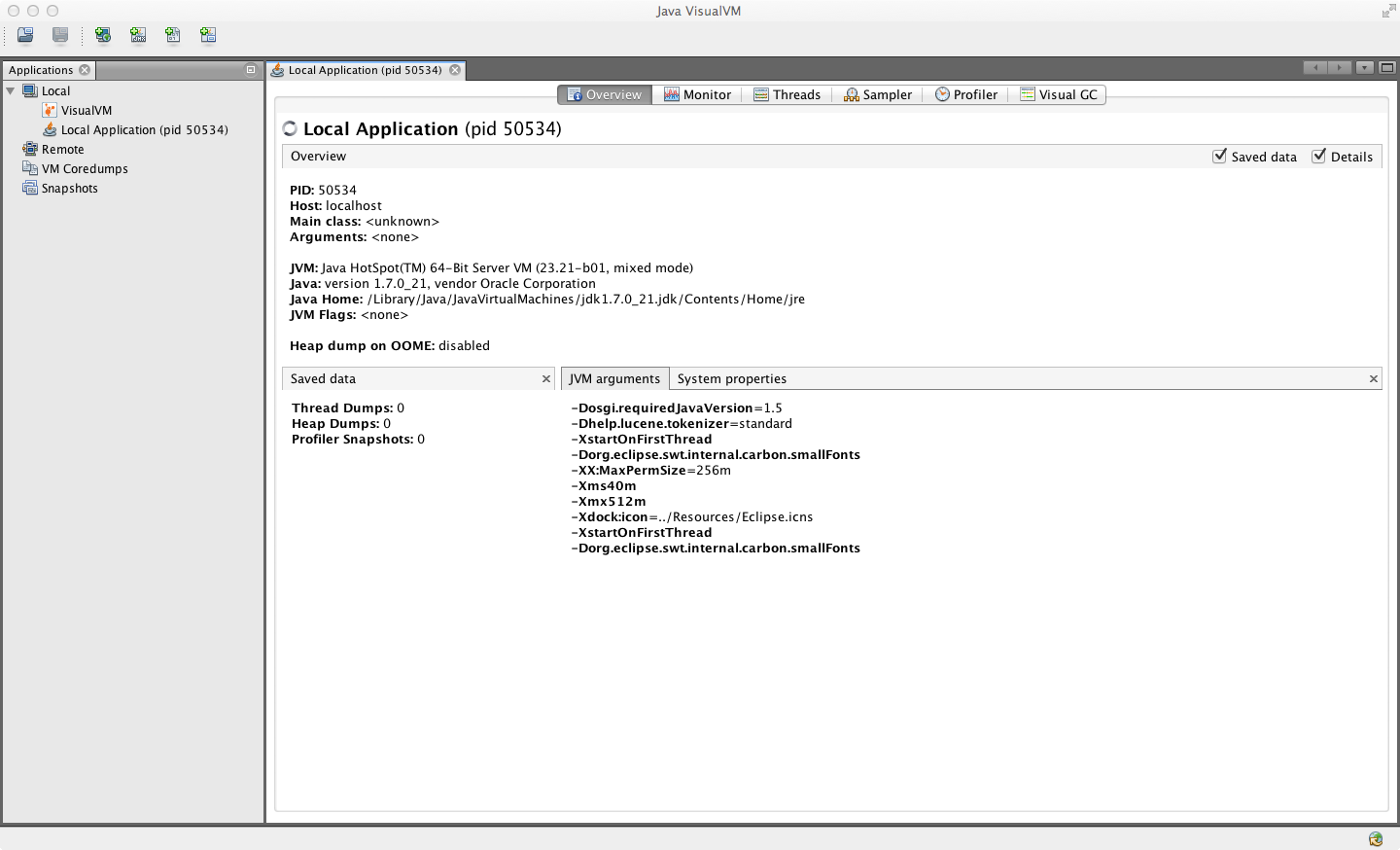

The Overview tab (see Figure A-2) provides a summary of information about your Java process. This includes the flags and system properties that were passed in, and the exact Java version being executed.

Figure A-2. Overview tab

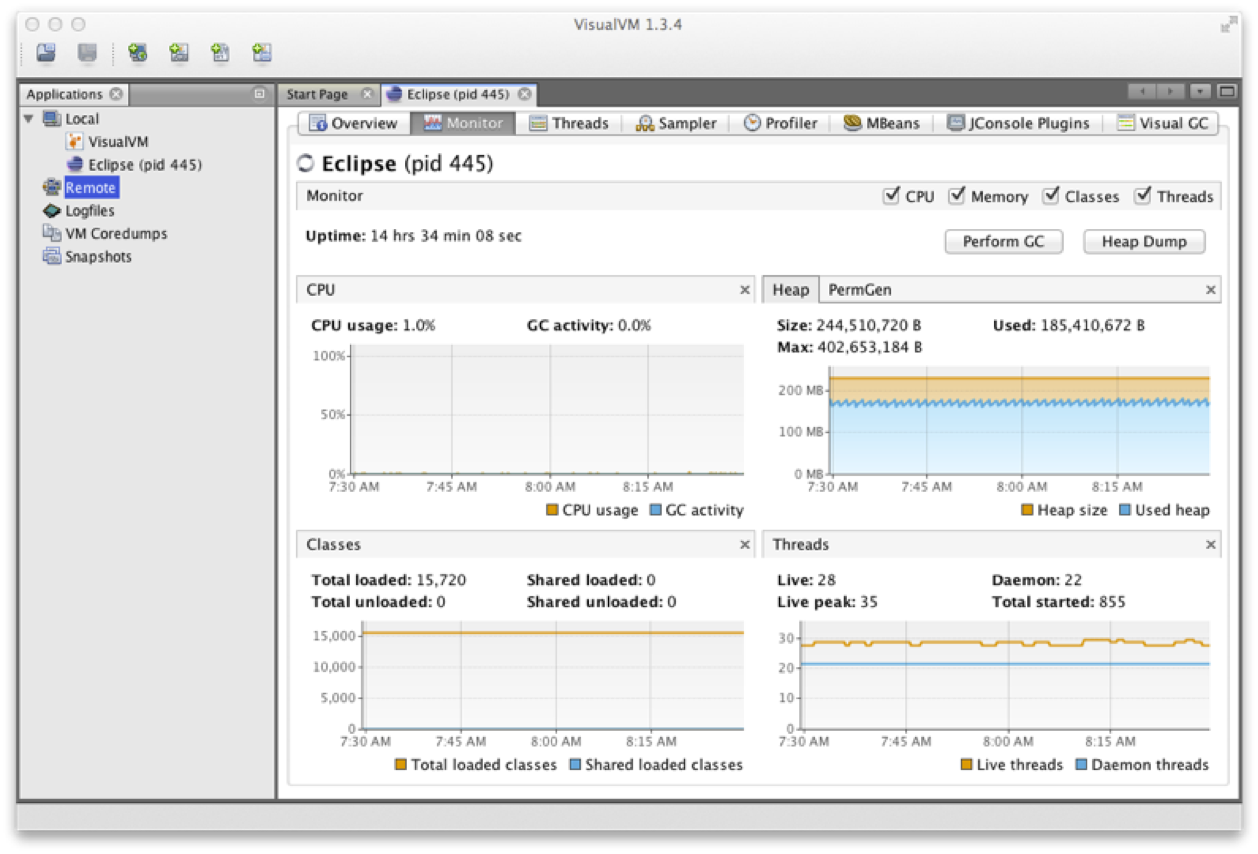

In the Monitor tab, as shown in Figure A-3, graphs and data about the active parts of the JVM system are displayed. This is essentially high-level telemetry data for the JVM—including CPU usage and how much CPU is being used for GC.

Figure A-3. Monitor tab

Other information displayed includes the number of classes loaded and unloaded, basic heap memory information, and an overview of the numbers of threads running.

From this tab, it is also possible to ask the JVM to produce a heap dump, or to perform a full GC—although in normal production operation, neither is recommended.

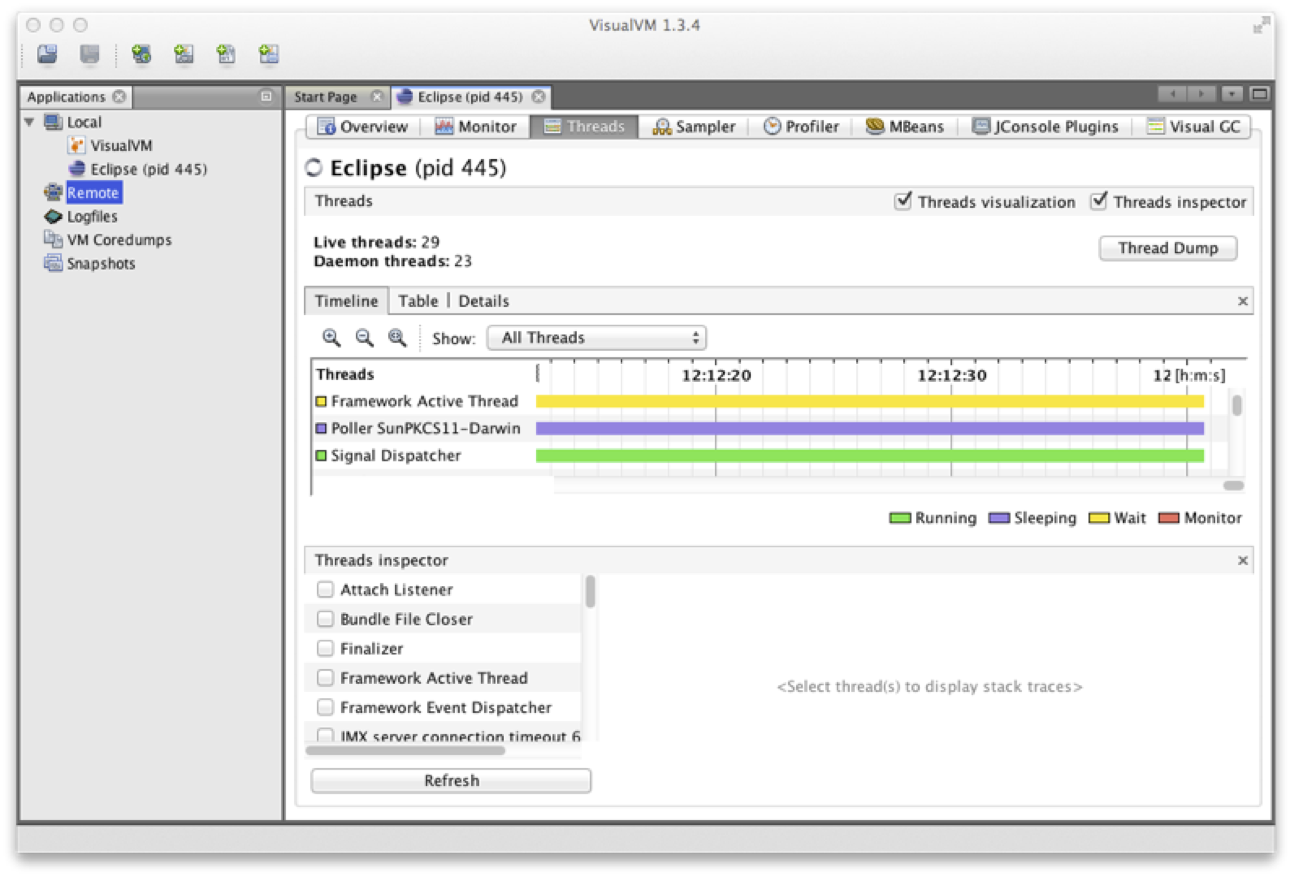

Figure A-4 shows the Threads tab, which displays data on actively running threads in the JVM. This is displayed as a continuous timeline, with the ability to inspect individual thread details and perform thread dumps for deeper analysis.

This presents a similar view to jstack, but with better abilities to

diagnose deadlocks and thread starvation. Here we can clearly see the difference

between synchronized locks (i.e., operating system monitors) and the

user-space lock objects of java.util.concurrent.

Threads that are contending on locks backed by operating system monitors (i.e., synchronized blocks) will be placed into the BLOCKED state. This shows up as red in VisualVM.

Figure A-4. Threads tab

Warning

Locked java.util.concurrent lock objects place their threads into

WAITING (yellow in VisualVM). This is because the implementation

provided by java.util.concurrent is purely user space and does not

involve the operating system.

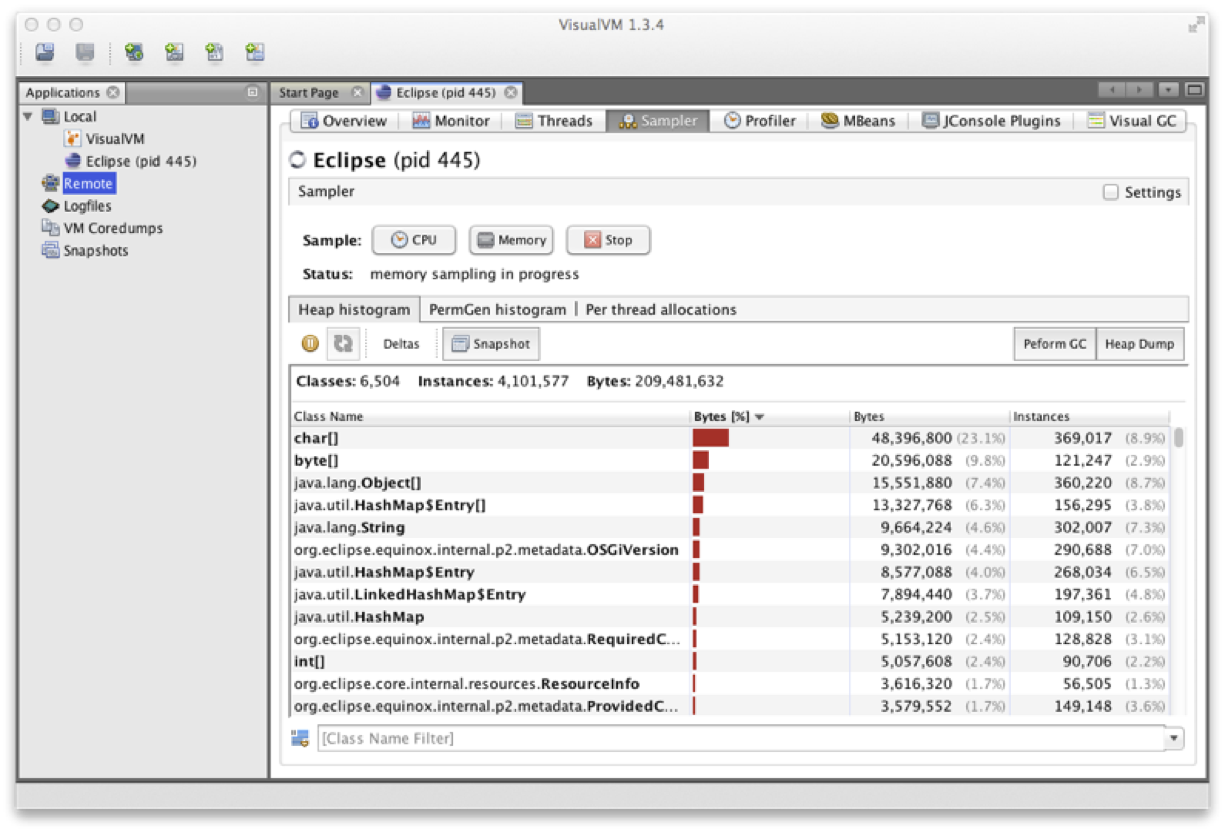

The Sampler tab in memory sampling mode, as shown in Figure A-5, enables the developer to see what the most common objects are, in terms of bytes and instances (in a manner similar to jmap -histo).

The objects displayed on the Metaspace submode are typically core Java/JVM constructs.2 Normally, we need to look deeper into other parts of the system, such as classloading, to see the code responsible for creating these objects.

Figure A-5. Sampler tab

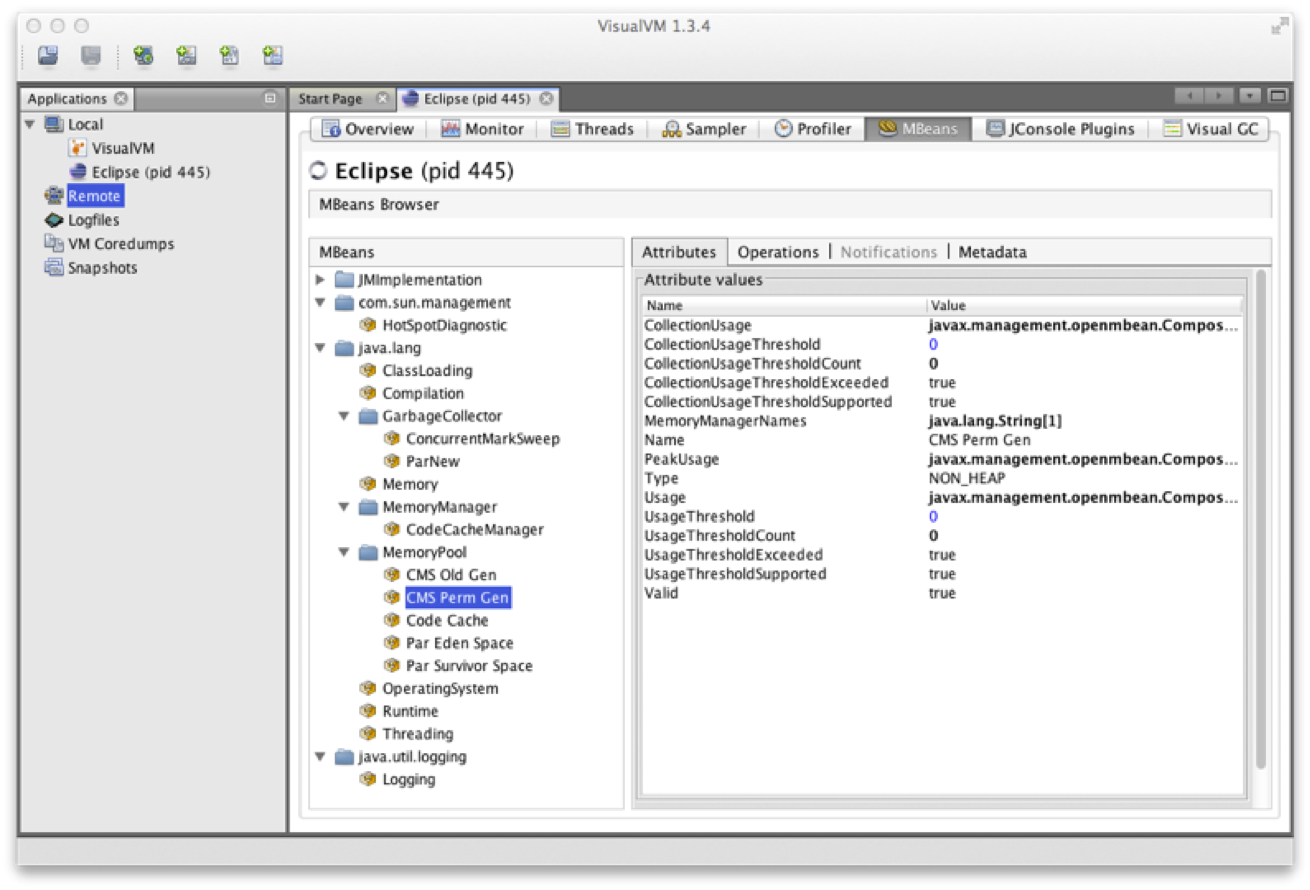

jvisualvm has a plug-in system, which you can use to extend the functionality of the framework by downloading and installing extra plug-ins. We recommend always installing the MBeans plug-in (shown in Figure A-6) and the VisualGC plug-in (discussed next, and shown in Figure A-7), and usually the JConsole compatibility plug-in, just in case.

The MBeans tab allows the operator to interact with Java management services (essentially MBeans). JMX is a great way to provide runtime control of your Java/JVM applications, but a full discussion is outside the scope of this book.

Figure A-6. MBeans plug-in

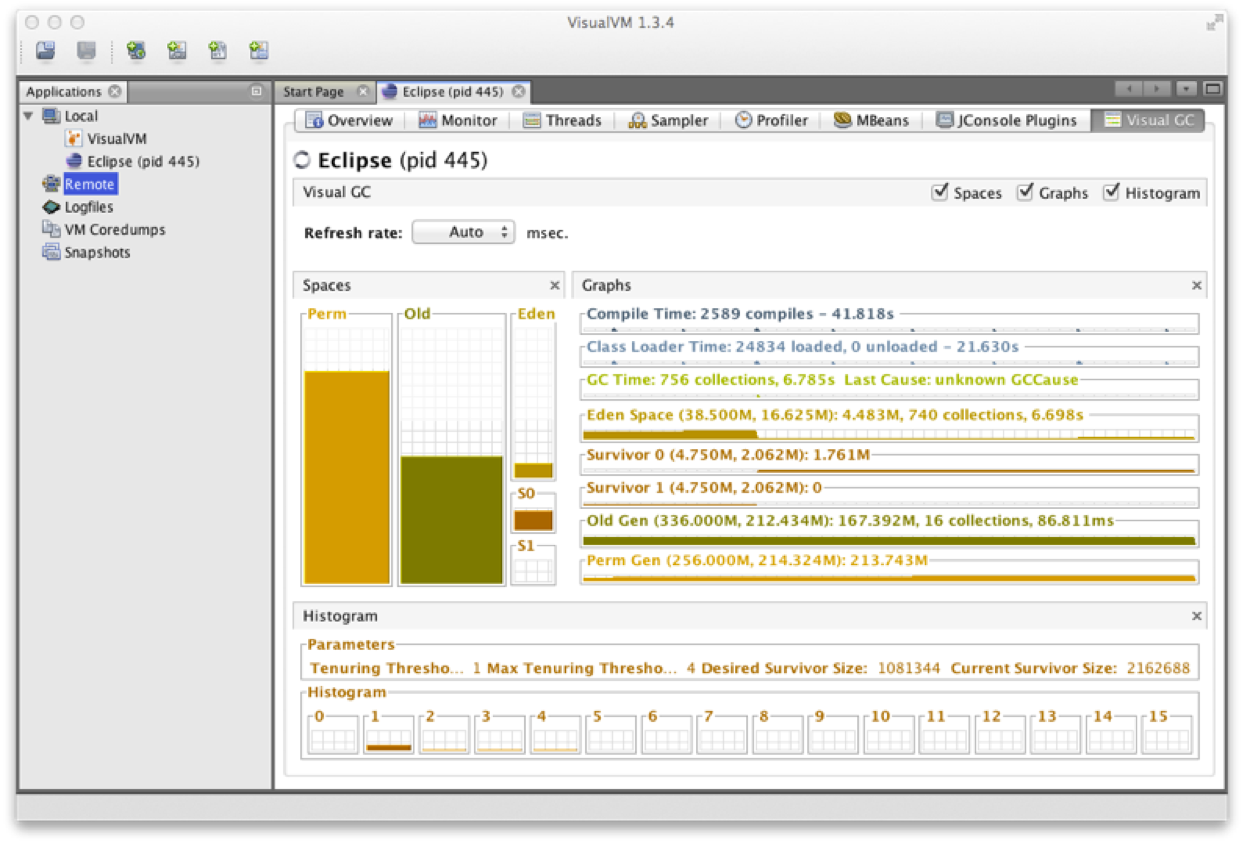

The VisualGC plug-in, shown in Figure A-7, is one of the simplest and best initial GC debugging tools available. As mentioned in Chapter 6, for serious analysis, GC logs are preferred to the JMX-based view that VisualGC provides.

Figure A-7. VisualGC plug-in

Having said that, VisualGC can be a good way to start to understand the GC behavior of an application, and to inform deeper investigations. It provides a near real-time view of the memory pools inside HotSpot, and allows the developer to see how GC causes objects to flow from space to space over the course of GC cycles.