Chapter 8. Remembering Information: Databases

The HTML and CSS that give your website its pretty face reside in individual files on your web server. So does the PHP code that processes forms and performs other dynamic wizardry. There’s a third kind of information necessary to a web application, though: data. And while you can store data such as user lists and product information in individual files, most people find it easier to use databases, which are the focus of this chapter.

Lots of information falls under the broad umbrella of data:

- Who your users are, such as their names and email addresses

- What your users do, such as message board posts and profile information

- The “stuff” that your site is about, such as a list of record albums, a product catalog, or what’s for dinner

There are three big reasons why this kind of data belongs in a database instead of in files: convenience, simultaneous access, and security. A database program makes it much easier to search for and manipulate individual pieces of information. With a database program, you can do things such as change the email address for user Duck29 to ducky@ducks.example.com in one step. If you put usernames and email addresses in a file, changing an email address would be much more complicated: you’d have to read the old file, search through each line until you find the one for Duck29, change the line, and write the file back out. If, at same time, one request updates Duck29’s email address and another updates the record for user Piggy56, one update could be lost, or (worse) the data file could be corrupted. Database software manages the intricacies of simultaneous access for you.

In addition to searchability, database programs usually provide you with a different set of access control options compared to files. It is an exacting process to set things up properly so that your PHP programs can create, edit, and delete files on your web server without opening the door to malicious attackers who could abuse that setup to alter your PHP scripts and data files. A database program makes it easier to arrange the appropriate levels of access to your information. It can be configured so that your PHP programs can read and change some information, but only read other information. However the database access control is set up, it doesn’t affect how files on the web server are accessed. Just because your PHP program can change values in the database doesn’t give an attacker an opportunity to change your PHP programs and HTML files themselves.

The word database is used in a few different ways when talking about web applications. A database can be a pile of structured information, a program (such as MySQL or Oracle) that manages that structured information, or the computer on which that program runs. This book uses “database” to mean the pile of structured information. The software that manages the information is a database program, and the computer that the database program runs on is a database server.

Most of this chapter uses the PHP Data Objects (PDO) database program abstraction layer. This is a part of PHP that simplifies communication between your PHP program and your database program. With PDO, you can use the same functions in PHP to talk to many different kinds of database programs. Without PDO, you need to rely on other PHP functions to talk to your database program. The appropriate set of functions varies with each database program. Some of the more exotic features of your database program may only be accessible through the database-specific functions.

Organizing Data in a Database

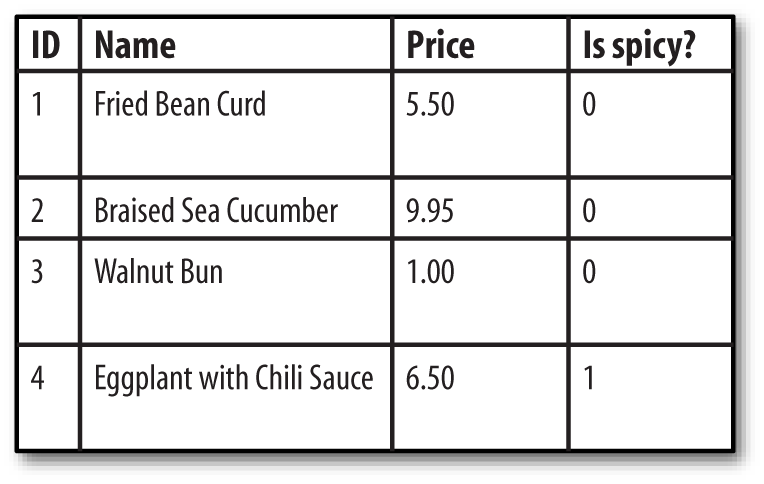

Information in your database is organized in tables, which have rows and columns. (Columns are also sometimes referred to as fields.) Each column in a table is a category of information, and each row is a set of values for each column. For example, a table holding information about dishes on a menu would have columns for each dish’s ID, name, price, and whether or not it’s spicy. Each row in the table is the group of values for one particular dish—for example, “1,” “Fried Bean Curd,” “5.50,” and “0” (meaning not spicy).

You can think of a table as being organized like a simple spreadsheet, with column names across the top, as shown in Figure 8-1.

One important difference between a spreadsheet and a database table, however, is that the rows in a database table have no inherent order. When you want to retrieve data from a table with the rows arranged in a particular way (e.g., in alphabetic order by student name), you need to explicitly specify that order when you ask the database for the data. The “SQL Lesson: ORDER BY and LIMIT” sidebar in this chapter describes how to do this.

Figure 8-1. Data organized in a table

Structured Query Language (SQL) is a language used to ask questions of and give instructions to the database program. Your PHP program sends SQL queries to a database program. If the query retrieves data in the database (for example, “Find me all spicy dishes”), then the database program responds with the set of rows that match the query. If the query changes data in the database (for example, “Add this new dish” or “Double the prices of all nonspicy dishes”), then the database program replies with whether or not the operation succeeded.

SQL is a mixed bag when it comes to case-sensitivity. SQL keywords are not case-sensitive, but in this book they are always written in uppercase to distinguish them from the other parts of the queries. Names of tables and columns in your queries generally are case-sensitive. All of the SQL examples in this book use lowercase column and table names to help you distinguish them from the SQL keywords. Any literal values that you put in queries are case-sensitive. Telling the database program that the name of a new dish is fried bean curd is different than telling it that the new dish is called FRIED Bean Curd.

Almost all of the SQL queries that you write to use in your PHP programs will rely on one of four SQL commands: INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, or SELECT. Each of these commands is described in this chapter. “Creating a Table” describes the CREATE TABLE command, which you use to make new tables in your database.

To learn more about SQL, read SQL in a Nutshell, by Kevin E. Kline (O’Reilly). It provides an overview of standard SQL as well as the SQL extensions in MySQL, Oracle, PostgreSQL, and Microsoft SQL Server. For more in-depth information about working with PHP and MySQL, read Learning PHP, MySQL & JavaScript, by Robin Nixon (O’Reilly). MySQL Cookbook by Paul DuBois (O’Reilly) is also an excellent source for answers to lots of SQL and MySQL questions.

Connecting to a Database Program

To establish a connection to a database program, create a new PDO object. You pass the PDO constructor a string that describes the database you are connecting to, and it returns an object that you use in the rest of your program to exchange information with the database program.

Example 8-1 shows a call to new PDO() that connects to a database named restaurant in a MySQL server running on db.example.com, using the username penguin and the password top^hat.

Example 8-1. Connecting with a PDO object

$db=newPDO('mysql:host=db.example.com;dbname=restaurant','penguin','top^hat');

The string passed as the first argument to the PDO constructor is called a data source name (DSN). It begins with a prefix indicating what kind of database program to connect to, then has a :, then some semicolon-separated key=value pairs providing information about how to connect. If the database connection needs a username and password, these are passed as the second and third arguments to the PDO constructor.

The particular key=value pairs you can put in a DSN depend on what kind of database program you’re connecting to. Although the PHP engine has the capability to connect to many different databases with PDO, that connectivity has to be enabled when the engine is built and installed on your server. If you get a could not find driver message when creating a PDO object, it means that your PHP engine installation does not incorporate support for the database you’re trying to use.

Table 8-1 lists the DSN prefixes and options for some of the most popular database programs that work with PDO.

| Database program | DSN prefix | DSN options | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MySQL | mysql |

host, port, dbname, unix_socket, charset |

unix_socket is for local MySQL connections. Use it or host and port, but not both. |

| PostgreSQL | pgsql |

host, port, dbname, user, password, others |

The whole connection string is passed to an internal PostgreSQL connection function, so you can use any of the options listed in the PostgreSQL documentation. |

| Oracle | oci |

dbname, charset |

The value of dbname should either be an Oracle Instant Client connection URI of the form //hostname:port/database or an address name defined in your tnsnames.ora file. |

| SQLite | sqlite |

None | After the prefix, the entire DSN must be either a path to an SQLite database file, or the string :memory: to use a temporary in-memory database. |

| ODBC | odbc |

DSN, UID, PWD |

The value for the DSN key inside the DSN string should either be a name defined in your ODBC catalog or a full ODBC connection string. |

| MS SQL Server or Sybase | mssql, sybase, dblib |

host, dbname, charset, appname |

The appname value is a string that the database program uses to describe your connection in its statistics. The mssql prefix is for when the PHP engine is using Microsoft’s SQL Server libraries; the sybase prefix is for when the engine is using Sybase CT-Lib libraries; the dblib prefix is for when the engine is using the FreeTDS libraries. |

The host and port DSN options, as seen in Example 8-1, specify the host and network port of the database server. The charset option, available with some database programs, specifies how the database program should handle non-English characters. The user and password options for PostgreSQL and the UID and PWD options for ODBC provide a way to put the connection username and password in the DSN string. If they are used, their values override any username or password passed as additional arguments to the PDO constructor.

If all goes well with new PDO(), it returns an object that you use to interact with the database. If there is a problem connecting, it throws a PDOException exception. Make sure to catch exceptions that could be thrown from the PDO constructor so you can verify that the connection succeeded before going forward in your program. Example 8-2 shows how to do this.

Example 8-2. Catching connection errors

try{$db=newPDO('mysql:host=localhost;dbname=restaurant','penguin','top^hat');// Do some stuff with $db here}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't connect to the database: ".$e->getMessage();}

In Example 8-2, if the PDO constructor throws an exception, then any code inside the try block after the call to new PDO() doesn’t execute. Instead, the PHP engine jumps ahead to the catch block, where an error is displayed.

For example, if top^hat is the wrong password for user penguin, Example 8-2 prints something like:

Couldn't connect to the database: SQLSTATE[HY000] [1045] Access denied for user 'penguin'@'client.example.com' (using password: YES)

Creating a Table

Before you can put any data into or retrieve any data from a database table, you must create the table. This is usually a one-time operation. You tell the database program to create a new table once. Your PHP program that uses the table may read from or write to that table every time it runs, but it doesn’t have to re-create the table each time. If a database table is like a spreadsheet, then creating a table is like making a new spreadsheet file. After you create the file, you can open it many times to read or change it.

The SQL command to create a table is CREATE TABLE. You provide the name of the table and the names and types of all the columns in the table. Example 8-3 shows the SQL command to create the dishes table pictured in Figure 8-1.

Example 8-3. Creating the dishes table

CREATETABLEdishes(dish_idINTEGERPRIMARYKEY,dish_nameVARCHAR(255),priceDECIMAL(4,2),is_spicyINT)

Example 8-3 creates a table called dishes with four columns. The dishes table looks like the one pictured in Figure 8-1. The columns in the table are dish_id, dish_name, price, and is_spicy. The dish_id and is_spicy columns are integers. The price column is a decimal number. The dish_name column is a string.

After the literal CREATE TABLE comes the name of the table. Then, between the parentheses, is a comma-separated list of the columns in the table. The phrase that defines each column has two parts: the column name and the column type. In Example 8-3, the column names are dish_id, dish_name, price, and is_spicy. The column types are INTEGER, VARCHAR(255), DECIMAL(4,2), and INT.

Additionally, the dish_id column’s type has PRIMARY KEY after it. This tells the database program that the values for this column can’t be duplicated in this table. Only one row can have a particular dish_id value at a time. Additionally, this lets SQLite, the database program used in this chapter’s examples, automatically assign new unique values to this column when we insert data. Other database programs have different syntax for automatically assigning unique integer IDs. For example, MySQL uses the AUTO_INCREMENT keyword, PostgreSQL uses serial types, and Oracle uses sequences.

INT and INTEGER can generally be used interchangeably. However, a quirk of SQLite is that in order to get the automatic assign-new-unique-values behavior with PRIMARY KEY, you need to specify the column type INTEGER exactly.

Some column types include length or formatting information in parentheses. For example, VARCHAR(255) means “a variable-length character column that is at most 255 characters long.” The type DECIMAL(4,2) means “a decimal number with two digits after the decimal place and four digits total.” Table 8-2 lists some common types for database table columns.

| Column type | Description |

|---|---|

VARCHAR(length) |

A variable-length string up to length characters long |

INT |

An integer |

BLOBa |

Up to 64 KB of string or binary data |

DECIMAL(total_digits,decimal_places) |

A decimal number with a total of total_digits digits and decimal_places digits after the decimal point |

DATETIMEb |

A date and time, such as 1975-03-10 19:45:03 or 2038-01-18 22:14:07 |

a PostgreSQL calls this b Oracle calls this | |

Different database programs support different column types, although all database programs should support the types listed in Table 8-2. The maximum and minimum numbers that the database can handle in numeric columns and the maximum size of text columns varies based on what database program you are using. For example, MySQL allows VARCHAR columns to be up to 255 characters long, but Microsoft SQL Server allows VARCHAR columns to be up to 8,000 characters long. Check your database manual for the specifics that apply to you.

To actually create the table, you need to send the CREATE TABLE command to the database. After connecting with new PDO(), use the exec() function to send the command as shown in Example 8-4.

Example 8-4. Sending a CREATE TABLE command to the database program

try{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION);$q=$db->exec("CREATE TABLE dishes (dish_id INT,dish_name VARCHAR(255),price DECIMAL(4,2),is_spicy INT)");}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't create table: ".$e->getMessage();}

The next section explains exec() in much more detail. The call to $db->setAttribute() in Example 8-4 ensures that PDO throws exceptions if there are problems with queries, not just a problem when connecting. Error handling with PDO is also discussed in the next section.

The opposite of CREATE TABLE is DROP TABLE. It removes a table and the data in it from a database. Example 8-5 shows the syntax of a query that removes the dishes table.

Example 8-5. Removing a table

DROPTABLEdishes

Once you’ve dropped a table, it’s gone for good, so be careful with DROP TABLE!

Putting Data into the Database

Assuming the connection to the database succeeds, the object returned by new PDO() provides access to the data in your database. Calling that object’s functions lets you send queries to the database program and access the results. To put some data into the database, pass an INSERT statement to the object’s exec() method, as shown in Example 8-6.

Example 8-6. Inserting data with exec()

try{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION);$affectedRows=$db->exec("INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name, price, is_spicy)VALUES ('Sesame Seed Puff', 2.50, 0)");}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't insert a row: ".$e->getMessage();}

The exec() method returns the number of rows affected by the SQL statement that was sent to the database server. In this case, inserting one row returns 1 because one row (the row you inserted) was affected.

If something goes wrong with INSERT, an exception is thrown. Example 8-7 attempts an INSERT statement that has a bad column name in it. The dishes table doesn’t contain a column called dish_size.

Example 8-7. Checking for errors from exec()

try{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION);$affectedRows=$db->exec("INSERT INTO dishes (dish_size, dish_name,price, is_spicy)VALUES ('large', 'Sesame Seed Puff', 2.50, 0)");}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't insert a row: ".$e->getMessage();}

Because the call to $db->setAttribute() tells PDO to throw an exception any time there’s an error, Example 8-7 prints:

Couldn't insert a row: SQLSTATE[HY000]: General error: 1 table dishes has no column named dish_size

PDO has three error modes: exception, silent, and warning. The exception error mode, which is activated by calling $db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE, PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION), is the best for debugging and is the mode that makes it easiest to ensure you don’t miss a database problem. If you don’t handle an exception that PDO generates, your program stops running.

The other two error modes require you to check the return values from your PDO function calls to determine if there is an error and then use additional PDO methods to find information about the error.

The silent mode is the default. Like other PDO methods, if exec() fails at its task, it returns false. Example 8-8 checks exec()’s return value and then uses PDO’s errorInfo() method to get details of the problem.

Example 8-8. Working with the silent error mode

// The constructor always throws an exception if it failstry{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't connect: ".$e->getMessage();}$result=$db->exec("INSERT INTO dishes (dish_size, dish_name, price, is_spicy)VALUES ('large', 'Sesame Seed Puff', 2.50, 0)");if(false===$result){$error=$db->errorInfo();"Couldn't insert!\n";"SQL Error={$error[0]}, DB Error={$error[1]}, Message={$error[2]}\n";}

Example 8-8 prints:

Couldn't insert! SQL Error=HY000, DB Error=1, Message=table dishes has no column named dish_size

In Example 8-8, the return value from exec() is compared with false using the triple-equals-sign identity operator to distinguish between an actual error (false) and a successful query that just happened to affect zero rows. Then, errorInfo() returns a three-element array with error information. The first element is an SQLSTATE error code. These are error codes that are mostly standardized across different database programs. In this case, HY000 is a catch-all for general errors. The second element is an error code specific to the particular database program in use. The third element is a textual message describing the error.

The warning mode is activated by setting the PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE attribute to PDO::ERRMODE_WARNING, as shown in Example 8-9. In this mode, functions behave as they do in silent mode—no exceptions, returning false on error—but the PHP engine also generates a warning-level error message. Depending on how you’ve configured error handling, this message may get displayed on screen or in a log file. “Controlling Where Errors Appear” shows how to control where error messages appear.

Example 8-9. Working with the warning error mode

// The constructor always throws an exception if it failstry{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't connect: ".$e->getMessage();}$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_WARNING);$result=$db->exec("INSERT INTO dishes (dish_size, dish_name, price, is_spicy)VALUES ('large', 'Sesame Seed Puff', 2.50, 0)");if(false===$result){$error=$db->errorInfo();"Couldn't insert!\n";"SQL Error={$error[0]}, DB Error={$error[1]}, Message={$error[2]}\n";}

Example 8-9 produces the same output as Example 8-8 but also generates the following error message:

PHP Warning: PDO::exec(): SQLSTATE[HY000]: General error: 1 table dishes has no column named dish_size in error-warning.php on line 10

Use the exec() function to change data with UPDATE. Example 8-15 shows some UPDATE statements.

Example 8-15. Changing data with exec()

try{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION);// Eggplant with Chili Sauce is spicy// If we don't care how many rows are affected,// there's no need to keep the return value from exec()$db->exec("UPDATE dishes SET is_spicy = 1WHERE dish_name = 'Eggplant with Chili Sauce'");// Lobster with Chili Sauce is spicy and pricy$db->exec("UPDATE dishes SET is_spicy = 1, price=price * 2WHERE dish_name = 'Lobster with Chili Sauce'");}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't insert a row: ".$e->getMessage();}

Also use the exec() function to delete data with DELETE. Example 8-16 shows exec() with two DELETE statements.

Example 8-16. Deleting data with exec()

try{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION);// remove expensive dishesif($make_things_cheaper){$db->exec("DELETE FROM dishes WHERE price > 19.95");}else{// or, remove all dishes$db->exec("DELETE FROM dishes");}}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't delete rows: ".$e->getMessage();}

Remember that exec() returns the number of rows changed or removed by an UPDATE or DELETE statement. Use the return value to find out how many rows that query affected. Example 8-21 reports how many rows have had their prices changed by an UPDATE query.

Example 8-21. Finding how many rows an UPDATE or DELETE affects

// Decrease the price of some dishes$count=$db->exec("UPDATE dishes SET price = price + 5 WHERE price > 3");'Changed the price of '.$count.' rows.';

If there are two rows in the dishes table whose price is more than 3, then Example 8-21 prints:

Changed the price of 2 rows.

Inserting Form Data Safely

As “HTML and JavaScript” explained, printing unsanitized form data can leave you and your users vulnerable to a cross-site scripting attack. Using unsanitized form data in SQL queries can cause a similar problem, called an “SQL injection attack.” Consider a form that lets a user suggest a new dish. The form contains a text element called new_dish_name into which the user can type the name of a new dish. The call to exec() in Example 8-25 inserts the new dish into the dishes table, but is vulnerable to an SQL injection attack.

Example 8-25. Unsafe insertion of form data

$db->exec("INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name)VALUES ('$_POST[new_dish_name]')");

If the submitted value for new_dish_name is reasonable, such as Fried Bean Curd, then the query succeeds. PHP’s regular double-quoted string interpolation rules make the query INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name) VALUES ('Fried Bean Curd'), which is valid and respectable. A query with an apostrophe in it causes a problem, though. If the submitted value for new_dish_name is General Tso's Chicken, then the query becomes INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name) VALUES ('General Tso's Chicken'). This makes the database program confused. It thinks that the apostrophe between Tso and s ends the string, so the s Chicken' after the second single quote is an unwanted syntax error.

What’s worse, a user who really wants to cause problems can type in specially constructed input to wreak havoc. Consider this unappetizing input:

x'); DELETE FROM dishes; INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name) VALUES ('y.

When that gets interpolated, the query becomes:

INSERTINTODISHES(dish_name)VALUES('x');DELETEFROMdishes;INSERTINTOdishes(dish_name)VALUES('y')

Some databases let you pass multiple queries separated by semicolons in one call of exec(). On those databases, the previous input will cause the dishes table to be demolished: a dish named x is inserted, all dishes are deleted, and a dish named y is inserted.

By submitting a carefully built form input value, a malicious user can inject arbitrary SQL statements into your database program. To prevent this, you need to escape special characters (most importantly, the apostrophe) in SQL queries. PDO provides a helpful feature called prepared statements that makes this a snap.

With prepared statements, you separate your query execution into two steps. First, you give PDO’s prepare() method a version of your query with a ? in the SQL in each place you want a value to go. This method returns a PDOStatement object. Then, you call execute() on your PDOStatement object, passing it an array of values to be substituted for the placeholding ? characters. The values are appropriately quoted before they are put into the query, protecting you from SQL injection attacks. Example 8-26 shows the safe version of the query from Example 8-25.

Example 8-26. Safe insertion of form data

$stmt=$db->prepare('INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name) VALUES (?)');$stmt->execute(array($_POST['new_dish_name']));

You don’t need to put quotes around the placeholder in the query. PDO takes care of that for you, too. If you want to use multiple values in a query, put multiple placeholders in the query and in the value array. Example 8-27 shows a query with three placeholders.

Example 8-27. Using multiple placeholders

$stmt=$db->prepare('INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name,price,is_spicy) VALUES (?,?,?)');$stmt->execute(array($_POST['new_dish_name'],$_POST['new_price'],$_POST['is_spicy']));

A Complete Data Insertion Form

Example 8-28 combines the database topics covered so far in this chapter with the form-handling code from Chapter 7 to build a complete program that displays a form, validates the submitted data, and then saves the data into a database table. The form displays input elements for the name of a dish, the price of a dish, and whether the dish is spicy. The information is inserted into the dishes table.

The code in Example 8-28 relies on the FormHelper class defined in Example 7-29. Instead of repeating it in this example, the code assumes it has been saved into a file called FormHelper.php and then loads it with the require 'FormHelper.php' line at the top of the program.

Example 8-28. Program for inserting records into dishes

<?php// Load the form helper classrequire'FormHelper.php';// Connect to the databasetry{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');}catch(PDOException$e){"Can't connect: ".$e->getMessage();exit();}// Set up exceptions on DB errors$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION);// The main page logic:// - If the form is submitted, validate and then process or redisplay// - If it's not submitted, displayif($_SERVER['REQUEST_METHOD']=='POST'){// If validate_form() returns errors, pass them to show_form()list($errors,$input)=validate_form();if($errors){show_form($errors);}else{// The submitted data is valid, so process itprocess_form($input);}}else{// The form wasn't submitted, so displayshow_form();}functionshow_form($errors=array()){// Set our own defaults: price is $5$defaults=array('price'=>'5.00');// Set up the $form object with proper defaults$form=newFormHelper($defaults);// All the HTML and form display is in a separate file for clarityinclude'insert-form.php';}functionvalidate_form(){$input=array();$errors=array();// dish_name is required$input['dish_name']=trim($_POST['dish_name']??'');if(!strlen($input['dish_name'])){$errors[]='Please enter the name of the dish.';}// price must be a valid floating-point number and// more than 0$input['price']=filter_input(INPUT_POST,'price',FILTER_VALIDATE_FLOAT);if($input['price']<=0){$errors[]='Please enter a valid price.';}// is_spicy defaults to 'no'$input['is_spicy']=$_POST['is_spicy']??'no';returnarray($errors,$input);}functionprocess_form($input){// Access the global variable $db inside this functionglobal$db;// Set the value of $is_spicy based on the checkboxif($input['is_spicy']=='yes'){$is_spicy=1;}else{$is_spicy=0;}// Insert the new dish into the tabletry{$stmt=$db->prepare('INSERT INTO dishes (dish_name, price, is_spicy)VALUES (?,?,?)');$stmt->execute(array($input['dish_name'],$input['price'],$is_spicy));// Tell the user that we added a dish'Added '.htmlentities($input['dish_name']).' to the database.';}catch(PDOException$e){"Couldn't add your dish to the database.";}}?>

Example 8-28 has the same basic structure as the form examples from Chapter 7: functions for displaying, validating, and processing the form with some global logic that determines which function to call. The two new pieces are the global code that sets up the database connection and the database-related activities in process_form().

The database setup code comes after the require statements and before the if ($_SERVER['REQUEST_METHOD'] == 'POST'). The new PDO() call establishes a database connection, and the next few lines check to make sure the connection succeeded and then set up exception mode for error handling.

The show_form() function displays the form HTML defined in the insert-form.php file. This file is shown in Example 8-29.

Example 8-29. Form for inserting records into dishes

<formmethod="POST"action="<?=$form->encode($_SERVER['PHP_SELF']) ?>"><table><?phpif($errors){?><tr><td>You need to correct the following errors:</td><td><ul><?phpforeach($errorsas$error){?><li><?=$form->encode($error)?></li><?php}?></ul></td><?php}?><tr><td>Dish Name:</td><td><?=$form->input('text',['name'=>'dish_name'])?></td></tr><tr><td>Price:</td><td><?=$form->input('text',['name'=>'price'])?></td></tr><tr><td>Spicy:</td><td><?=$form->input('checkbox',['name'=>'is_spicy','value'=>'yes'])?>Yes</td></tr><tr><td colspan="2" align="center"><?=$form->input('submit',['name'=>'save','value'=>'Order'])?></td></tr></table></form>

Aside from connecting, all of the other interaction with the database is in the process_form() function. First, the global $db line lets you refer to the database connection variable inside the function as $db instead of the clumsier $GLOBALS['db']. Then, because the is_spicy column of the table holds a 1 in the rows of spicy dishes and a 0 in the rows of nonspicy dishes, the if() clause in process_form() assigns the appropriate value to the local variable $is_spicy based on what was submitted in $input['is_spicy'].

After that come the calls to prepare() and execute() that actually put the new information into the database. The INSERT statement has three placeholders that are filled by the variables $input['dish_name'], $input['price'], and $is_spicy. No value is necessary for the dish_id column because SQLite populates that automatically. Lastly, process_form() prints a message telling the user that the dish was inserted. The htmlentities() function protects against any HTML tags or JavaScript in the dish name. Because prepare() and execute() are inside a try block, if anything goes wrong, an alternate error message is printed.

Retrieving Data from the Database

Use the query() method to retrieve information from the database. Pass it an SQL query for the database. It returns a PDOStatement object that provides access to the retrieved rows. Each time you call the fetch() method of this object, you get the next row returned from the query. When there are no more rows left, fetch() returns a value that evaluates to false, making it perfect to use in a while() loop. This is shown in Example 8-30.

Example 8-30. Retrieving rows with query() and fetch()

$q=$db->query('SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishes');while($row=$q->fetch()){"$row[dish_name],$row[price]\n";}

Example 8-30 prints:

Walnut Bun, 1 Cashew Nuts and White Mushrooms, 4.95 Dried Mulberries, 3 Eggplant with Chili Sauce, 6.5

The first time through the while() loop, fetch() returns an array containing Walnut Bun and 1. This array is assigned to $row. Since an array with elements in it evaluates to true, the code inside the while() loop executes, printing the data from the first row returned by the SELECT query. This happens three more times. On each trip through the while() loop, fetch() returns the next row in the set of rows returned by the SELECT query. When it has no more rows to return, fetch() returns a value that evaluates to false, and the while() loop is done.

By default, fetch() returns an array with both numeric and string keys. The numeric keys, starting at 0, contain each column’s value for the row. The string keys do as well, with key names set to column names. In Example 8-30, the same results could be printed using $row[0] and $row[1].

If you want to find out how many rows a SELECT query has returned, your only foolproof option is to retrieve all the rows and count them. The PDOStatement object provides a rowCount() method, but it doesn’t work with all databases. If you have a small number of rows and you’re going to use them all in your program, use the fetchAll() method to put them into an array without looping, as shown in Example 8-31.

Example 8-31. Retrieving all rows without a loop

$q=$db->query('SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishes');// $rows will be a four-element array; each element is// one row of data from the database$rows=$q->fetchAll();

If you have so many rows that retrieving them all is impractical, ask your database program to count the rows for you with SQL’s COUNT() function. For example, SELECT COUNT(*) FROM dishes returns one row with one column whose value is the number of rows in the entire table.

If you are expecting only one row to be returned from a query, you can chain your fetch() call onto the end of query(). Example 8-37 uses a chained fetch() to display the least expensive item in the dishes table. The ORDER BY and LIMIT parts of the query in Example 8-37 are explained in the sidebar “SQL Lesson: ORDER BY and LIMIT”.

Example 8-37. Retrieving a row with a chained fetch()

$cheapest_dish_info = $db->query('SELECT dish_name, price

FROM dishes ORDER BY price LIMIT 1')->fetch();

print "$cheapest_dish_info[0], $cheapest_dish_info[1]";

Example 8-37 prints:

Walnut Bun, 1

Changing the Format of Retrieved Rows

So far, fetch() has been returning rows from the database as combined numerically and string-indexed arrays. This makes for concise and easy interpolation of values in double-quoted strings—but it can also be problematic. Trying to remember, for example, which column from the SELECT query corresponds to element 6 in the result array can be difficult and error-prone. Some string column names might require quoting to interpolate properly. And having the PHP engine set up numeric indexes and string indexes is wasteful if you don’t need them both. Fortunately, PDO lets you specify that you’d prefer to have each result row delivered in a different way. Pass an alternate fetch style to fetch() or fetchAll() as a first argument and you get your row back as only a numeric array, only a string array, or an object.

To get a row back as an array with only numeric keys, pass PDO::FETCH_NUM as the first argument to fetch() or fetchAll(). To get an array with only string keys, use PDO::FETCH_ASSOC (remember that string-keyed arrays are sometimes called “associative” arrays).

To get a row back as an object instead of an array, use PDO::FETCH_OBJ. The object that’s returned for each row has property names that correspond to column names.

Example 8-43 shows these alternate fetch styles in action.

Example 8-43. Using a different fetch style

// With numeric indexes only, it's easy to join the values together$q=$db->query('SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishes');while($row=$q->fetch(PDO::FETCH_NUM)){implode(', ',$row)."\n";}// With an object, property access syntax gets you the values$q=$db->query('SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishes');while($row=$q->fetch(PDO::FETCH_OBJ)){"{$row->dish_name}has price{$row->price}\n";}

If you want to use an alternate fetch style repeatedly, you can set the default for a particular statement for all queries you issue on a given connection. To set the default for a statement, call setFetchMode() on your PDOStatement object, as shown in Example 8-44.

Example 8-44. Setting a default fetch style on a statement

$q=$db->query('SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishes');// No need to pass anything to fetch(); setFetchMode()// takes care of it$q->setFetchMode(PDO::FETCH_NUM);while($row=$q->fetch()){implode(', ',$row)."\n";}

To set the default fetch style for everything, use setAttribute() to set the PDO::ATTR_DEFAULT_FETCH_MODE attribute on your database connection, like this:

// No need to call setFetchMode() or pass anything to fetch();// setAttribute() takes care of it$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_DEFAULT_FETCH_MODE,PDO::FETCH_NUM);$q=$db->query('SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishes');while($row=$q->fetch()){implode(', ',$row)."\n";}$anotherQuery=$db->query('SELECT dish_name FROM dishes WHERE price < 5');// Each subarray in $moreDishes is numerically indexed, too$moreDishes=$anotherQuery->fetchAll();

Retrieving Form Data Safely

It’s possible to use placeholders with SELECT statements just as you do with INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE statements. Instead of using query() directly, use prepare() and execute(), but give prepare() a SELECT statement.

However, when you use submitted form data or other external input in the WHERE clause of a SELECT, UPDATE, or DELETE statement, you must take extra care to ensure that any SQL wildcards are appropriately escaped. Consider a search form with a text element called dish_search into which the user can type the name of a dish she’s looking for. The call to execute() in Example 8-45 uses placeholders to guard against confounding single quotes in the submitted value.

Example 8-45. Using a placeholder in a SELECT statement

$stmt=$db->prepare('SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishesWHERE dish_name LIKE ?');$stmt->execute(array($_POST['dish_search']));while($row=$stmt->fetch()){// ... do something with $row ...}

Whether dish_search is Fried Bean Curd or General Tso's Chicken, the placeholder interpolates the value into the query appropriately. However, what if dish_search is %chicken%? Then, the query becomes SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishes WHERE dish_name LIKE '%chicken%'. This matches all rows that contain the string chicken, not just rows in which dish_name is exactly %chicken%.

To prevent SQL wildcards in form data from taking effect in queries, you must forgo the comfort and ease of the placeholder and rely on two other functions: quote() in PDO and PHP’s built-in strtr() function. First, call quote() on the submitted value. This does the same quoting operation that the placeholder does. For example, it turns General Tso's Chicken into 'General Tso''s Chicken'. The next step is to use strtr() to backslash-escape the SQL wildcards % and _. The quoted and wildcard-escaped value can then be used safely in a query.

Example 8-50 shows how to use quote() and strtr() to make a submitted value safe for a WHERE clause.

Example 8-50. Not using a placeholder in a SELECT statement

// First, do normal quoting of the value$dish=$db->quote($_POST['dish_search']);// Then, put backslashes before underscores and percent signs$dish=strtr($dish,array('_'=>'\_','%'=>'\%'));// Now, $dish is sanitized and can be interpolated right into the query$stmt=$db->query("SELECT dish_name, price FROM dishesWHERE dish_name LIKE$dish");

You can’t use a placeholder in this situation because the escaping of the SQL wildcards has to happen after the regular quoting. The regular quoting puts a backslash before single quotes, but also before backslashes. If strtr() processes the string first, a submitted value such as %chicken% becomes \%chicken\%. Then, the quoting (whether by quote() or the placeholder processing) turns \%chicken\% into '\\%chicken\\%'. This is interpreted by the database to mean a literal backslash, followed by the “match any characters” wildcard, followed by chicken, followed by another literal backslash, followed by another “match any characters” wildcard. However, if quote() goes first, %chicken% is turned into '%chicken%'. Then, strtr() turns it into '\%chicken\%'. This is interpreted by the database as a literal percent sign, followed by chicken, followed by another percent sign, which is what the user entered.

Not quoting wildcard characters has an even more drastic effect in the WHERE clause of an UPDATE or DELETE statement. Example 8-51 shows a query incorrectly using placeholders to allow a user-entered value to control which dishes have their prices set to $1.

Example 8-51. Incorrect use of placeholders in an UPDATE statement

$stmt=$db->prepare('UPDATE dishes SET price = 1 WHERE dish_name LIKE ?');$stmt->execute(array($_POST['dish_name']));

If the submitted value for dish_name in Example 8-51 is Fried Bean Curd, then the query works as expected: the price of that dish only is set to 1. But if $_POST['dish_name'] is %, then all dishes have their price set to 1! The quote() and strtr() technique prevents this problem. The right way to do the update is in Example 8-52.

Example 8-52. Correct use of quote() and strtr() with an UPDATE statement

// First, do normal quoting of the value$dish=$db->quote($_POST['dish_name']);// Then, put backslashes before underscores and percent signs$dish=strtr($dish,array('_'=>'\_','%'=>'\%'));// Now, $dish is sanitized and can be interpolated right into the query$db->exec("UPDATE dishes SET price = 1 WHERE dish_name LIKE$dish");

A Complete Data Retrieval Form

Example 8-53 is another complete database and form program. It presents a search form and then prints an HTML table of all rows in the dishes table that match the search criteria. Like Example 8-28, it relies on the form helper class being defined in a separate FormHelper.php file.

Example 8-53. Program for searching the dishes table

<?php// Load the form helper classrequire'FormHelper.php';// Connect to the databasetry{$db=newPDO('sqlite:/tmp/restaurant.db');}catch(PDOException$e){"Can't connect: ".$e->getMessage();exit();}// Set up exceptions on DB errors$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_ERRMODE,PDO::ERRMODE_EXCEPTION);// Set up fetch mode: rows as objects$db->setAttribute(PDO::ATTR_DEFAULT_FETCH_MODE,PDO::FETCH_OBJ);// Choices for the "spicy" menu in the form$spicy_choices=array('no','yes','either');// The main page logic:// - If the form is submitted, validate and then process or redisplay// - If it's not submitted, displayif($_SERVER['REQUEST_METHOD']=='POST'){// If validate_form() returns errors, pass them to show_form()list($errors,$input)=validate_form();if($errors){show_form($errors);}else{// The submitted data is valid, so process itprocess_form($input);}}else{// The form wasn't submitted, so displayshow_form();}functionshow_form($errors=array()){// Set our own defaults$defaults=array('min_price'=>'5.00','max_price'=>'25.00');// Set up the $form object with proper defaults$form=newFormHelper($defaults);// All the HTML and form display is in a separate file for clarityinclude'retrieve-form.php';}functionvalidate_form(){$input=array();$errors=array();// Remove any leading/trailing whitespace from submitted dish name$input['dish_name']=trim($_POST['dish_name']??'');// Minimum price must be a valid floating-point number$input['min_price']=filter_input(INPUT_POST,'min_price',FILTER_VALIDATE_FLOAT);if($input['min_price']===null||$input['min_price']===false){$errors[]='Please enter a valid minimum price.';}// Maximum price must be a valid floating-point number$input['max_price']=filter_input(INPUT_POST,'max_price',FILTER_VALIDATE_FLOAT);if($input['max_price']===null||$input['max_price']===false){$errors[]='Please enter a valid maximum price.';}// Minimum price must be less than the maximum priceif($input['min_price']>=$input['max_price']){$errors[]='The minimum price must be less than the maximum price.';}$input['is_spicy']=$_POST['is_spicy']??'';if(!array_key_exists($input['is_spicy'],$GLOBALS['spicy_choices'])){$errors[]='Please choose a valid "spicy" option.';}returnarray($errors,$input);}functionprocess_form($input){// Access the global variable $db inside this functionglobal$db;// Build up the query$sql='SELECT dish_name, price, is_spicy FROM dishes WHEREprice >= ? AND price <= ?';// If a dish name was submitted, add to the WHERE clause.// We use quote() and strtr() to prevent user-entered wildcards from working.if(strlen($input['dish_name'])){$dish=$db->quote($input['dish_name']);$dish=strtr($dish,array('_'=>'\_','%'=>'\%'));$sql.=" AND dish_name LIKE$dish";}// If is_spicy is "yes" or "no", add appropriate SQL// (if it's "either", we don't need to add is_spicy to the WHERE clause)$spicy_choice=$GLOBALS['spicy_choices'][$input['is_spicy']];if($spicy_choice=='yes'){$sql.=' AND is_spicy = 1';}elseif($spicy_choice=='no'){$sql.=' AND is_spicy = 0';}// Send the query to the database program and get all the rows back$stmt=$db->prepare($sql);$stmt->execute(array($input['min_price'],$input['max_price']));$dishes=$stmt->fetchAll();if(count($dishes)==0){'No dishes matched.';}else{'<table>';'<tr><th>Dish Name</th><th>Price</th><th>Spicy?</th></tr>';foreach($dishesas$dish){if($dish->is_spicy==1){$spicy='Yes';}else{$spicy='No';}printf('<tr><td>%s</td><td>$%.02f</td><td>%s</td></tr>',htmlentities($dish->dish_name),$dish->price,$spicy);}}}?>

Example 8-53 is a lot like Example 8-28: it uses the standard display/validate/process form structure with global code for database setup and database interaction inside process_form(). The show_form() function displays the form HTML defined in the retrieve-form.php file. This file is shown in Example 8-54.

Example 8-54. Form for retrieving information about dishes

<formmethod="POST"action="<?=$form->encode($_SERVER['PHP_SELF']) ?>"><table><?phpif($errors){?><tr><td>You need to correct the following errors:</td><td><ul><?phpforeach($errorsas$error){?><li><?=$form->encode($error)?></li><?php}?></ul></td><?php}?><tr><td>Dish Name:</td><td><?=$form->input('text',['name'=>'dish_name'])?></td></tr><tr><td>Minimum Price:</td><td><?=$form->input('text',['name'=>'min_price'])?></td></tr><tr><td>Maximum Price:</td><td><?=$form->input('text',['name'=>'max_price'])?></td></tr><tr><td>Spicy:</td><td><?=$form->select($GLOBALS['spicy_choices'],['name'=>'is_spicy'])?></td></tr><tr><td colspan="2" align="center"><?=$form->input('submit',['name'=>'search','value'=>'Search'])?></td></tr></table></form>

One difference in Example 8-53 is an additional line in its database setup code: a call to setAttribute() that changes the fetch mode. Since process_form() is going to retrieve information from the database, the fetch mode is important.

The process_form() function builds up a SELECT statement, sends it to the database with execute(), retrieves the results with fetchAll(), and prints the results in an HTML table. Up to four factors go into the WHERE clause of the SELECT statement. The first two are the minimum and maximum price. These are always in the query, so they get placeholders in $sql, the variable that holds the SQL statement.

Next comes the dish name. That’s optional, but if it’s submitted, it goes into the query. A placeholder isn’t good enough for the dish_name column, though, because the submitted form data could contain SQL wildcards. Instead, quote() and strtr() prepare a sanitized version of the dish name, and it’s added directly onto the WHERE clause.

The last possible column in the WHERE clause is is_spicy. If the submitted choice is yes, then AND is_spicy = 1 goes into the query so that only spicy dishes are retrieved. If the submitted choice is no, then AND is_spicy = 0 goes into the query so that only nonspicy dishes are found. If the submitted choice is either, then there’s no need to have is_spicy in the query—rows should be picked regardless of their spiciness.

After the full query is constructed in $sql, it’s prepared with prepare() and sent to the database program with execute(). The second argument to execute() is an array containing the minimum and maximum price values so that they can be substituted for the placeholders. The array of rows that fetchAll() returns is stored in $dishes.

The last step in process_form() is printing some results. If there’s nothing in $dishes, No dishes matched is displayed. Otherwise, a foreach() loop iterates through dishes and prints out an HTML table row for each dish, using printf() to format the price properly and htmlentities() to encode any special characters in the dish name. An if() clause turns the database-friendly is_spicy values of 1 or 0 into the human-friendly values of Yes or No.

Chapter Summary

This chapter covered:

- Figuring out what kinds of information belong in a database

- Understanding how data is organized in a database

- Establishing a database connection

- Creating a table in the database

- Removing a table from the database

- Using the SQL

INSERTcommand - Inserting data into the database with

exec() - Checking for database errors by handling exceptions

- Changing the error mode with

setAttribute() - Using the SQL

UPDATEandDELETEcommands - Changing or deleting data with

exec() - Counting the number of rows affected by a query

- Using placeholders to insert data safely

- Using the SQL

SELECTcommand - Retrieving data from the database with

query()andfetch() - Counting the number of rows retrieved by

query() - Using the SQL

ORDER BYandLIMITkeywords withSELECT - Retrieving rows as string-keyed arrays or objects

- Using the SQL wildcards with

LIKE:%and_ - Escaping SQL wildcards in

SELECTstatements - Saving submitted form parameters in the database

- Using data from the database in form elements

Exercises

The following exercises use a database table called dishes with the following structure:

CREATETABLEdishes(dish_idINT,dish_nameVARCHAR(255),priceDECIMAL(4,2),is_spicyINT)

Here is some sample data to put into the dishes table:

INSERTINTOdishesVALUES(1,'Walnut Bun',1.00,0)INSERTINTOdishesVALUES(2,'Cashew Nuts and White Mushrooms',4.95,0)INSERTINTOdishesVALUES(3,'Dried Mulberries',3.00,0)INSERTINTOdishesVALUES(4,'Eggplant with Chili Sauce',6.50,1)INSERTINTOdishesVALUES(5,'Red Bean Bun',1.00,0)INSERTINTOdishesVALUES(6,'General Tso''s Chicken',5.50,1)

- Write a program that lists all of the dishes in the table, sorted by price.

- Write a program that displays a form asking for a price. When the form is submitted, the program should print out the names and prices of the dishes whose price is at least the submitted price. Don’t retrieve from the database any rows or columns that aren’t printed in the table.

- Write a program that displays a form with a

<select>menu of dish names. Create the dish names to display by retrieving them from the database. When the form is submitted, the program should print out all of the information in the table (ID, name, price, and spiciness) for the selected dish. - Create a new table that holds information about restaurant customers. The table should store the following information about each customer: customer ID, name, phone number, and the ID of the customer’s favorite dish. Write a program that displays a form for putting a new customer into the table. The part of the form for entering the customer’s favorite dish should be a

<select>menu of dish names. The customer’s ID should be generated by your program, not entered in the form.