Chapter 5. Interaction Is an Enhancement

“The Web is the most hostile software engineering environment imaginable.”

—DOUGLAS CROCKFORD

In February 2011, shortly after Gawker Media launched a unified redesign of its various properties (Lifehacker, Gizmodo, Jezebel, etc.), users visiting those sites were greeted by a blank stare (Figure 5.1). Not a single one displayed any content. What happened? JavaScript happened. Or, more accurately, JavaScript didn’t happen.1

In architecting its new platform, Gawker Media had embraced JavaScript as the delivery mechanism for its content. It would send a hollow HTML shell to the browser and then load the actual page content via JavaScript. The common wisdom was that this approach would make these sites appear more “app like” and “modern.” But on launch day, a single error in the JavaScript code running the platform brought the system to its knees. That one solitary error caused a lengthy “site outage”—I use that term liberally because the servers were actually still working—for every Gawker property and lost the company countless page views and ad impressions.

It’s worth noting that, in the intervening years, Gawker Media has updated its sites to deliver content in the absence of JavaScript.

Late one night in January 2014 the “parental filter” used by Sky Broadband—one of the UK’s largest ISPs (Internet service providers)—began classifying code.jquery.com as a “malware and phishing” website.2 The jQuery CDN (content delivery network) is at that URL. No big deal—jQuery is only the JavaScript library that nearly three-quarters of the world’s top 10,000 websites rely on to make their web pages work.

With the domain so mischaracterized, Sky’s firewall leapt into action and began “protecting” the vast majority of their customers from this “malicious” code. All of a sudden, huge swaths of the Web abruptly stopped working for every Sky Broadband customer who had not specifically opted out of this protection. Any site that relied on CDN’s copy of jQuery to load content, display advertising, or enable interactions was dead in the water—through no fault of their own.

In September 2014, Ars Technica revealed that Comcast was injecting self-promotional advertising into websites served via its Wi-Fi hotspots.3 Such injections are effectively a man-in-the middle attack,4 creating a situation that had the potential to break a website. As security expert Dan Kaminsky put it this way:

[Y]ou no longer know, as a website developer, precisely what code is running in browsers out there. You didn’t send it, but your customers received it.

Comcast isn’t the only organization that does this. Hotels, airports, and other “free” Wi-Fi providers routinely inject advertising and other code into websites that pass through their networks.

Many web designers and developers mistakenly believe that JavaScript support is a given or that issues with JavaScript drifted off with the decline of IE 8, but these three stories are all recent, and none of them concerned a browser support issue. If these stories tell you anything, it’s that you need to develop the 1964 Chrysler Imperial5 of websites—sites that soldier on even when they are getting pummeled from all sides. After all, devices, browsers, plugins, servers, networks, and even the routers that ultimately deliver your sites all have a say in how (and what) content actually gets to your users.

5 The 1964 Chrysler Imperial is a bit of a legend. It’s one of the few cars that has actually been outright banned from “demolition derby” events because it’s practically indestructible.

Get Familiar with Potential Issues So You Can Avoid Them

It seems that nearly every other week a new JavaScript framework comes out, touting a new approach that is going to “revolutionize” the way we build websites. Frameworks such as Angular, Ember, Knockout, and React do away with the traditional model of browsers navigating from page to page of server-generated content. Instead, these frameworks completely take over the browser and handle all the requests to the server, usually fetching bits and pieces of content a few at a time to control the whole experience end to end. No more page refreshes. No more waiting.

There’s just one problem: Without JavaScript, nothing happens.

No, I’m not here to tell you that you shouldn’t use JavaScript.6 I think JavaScript is an incredibly useful tool, and I absolutely believe it can make your users’ experiences better...when it’s used wisely.

6 It would be a short chapter if I did.

Understand Your Medium

In the early days of the Web, “proper” software developers shied away from JavaScript. Many viewed it as a “toy” language (and felt similarly about HTML and CSS). It wasn’t as powerful as Java or Perl or C in their minds, so it wasn’t really worth learning. In the intervening years, however, JavaScript has changed a lot.

Many of these developers began paying attention to JavaScript in the mid-2000s when Ajax became popular. But it wasn’t until a few years later that they began bringing their talents to the Web in droves, lured by JavaScript frameworks and their promise of a more traditional development experience for the Web. This, overall, is a good thing—we need more people working on the Web to make it better. The one problem I’ve seen, however, is the fundamental disconnect traditional software developers seem to have with the way deploying code on the Web works.

In traditional software development, you have some say in the execution environment. On the Web, you don’t. I’ll explain. If I’m writing server-side software in Python or Rails or even PHP, one of two things is true:

• I control the server environment, including the operating system, language versions, and packages.

• I don’t control the server environment, but I have knowledge of it and can author my program accordingly so it will execute as anticipated.

In the more traditional installed software world, you can similarly control the environment by placing certain restrictions on what operating systems your code supports and what dependencies you might have (such as available hard drive space or RAM). You provide that information up front, and your potential users can choose your software—or a competing product—based on what will work for them.

On the Web, however, all bets are off. The Web is ubiquitous. The Web is messy. And, as much as I might like to control a user’s experience down to the pixel, I understand that it’s never going to happen because that isn’t the way the Web works. The frustration I sometimes feel with my lack of control is also incredibly liberating and pushes me to come up with more creative approaches. Unfortunately, traditional software developers who are relatively new to the Web have not come to terms with this yet. It’s understandable; it took me a few years as well.

You do not control the environment executing your JavaScript code, interpreting your HTML, or applying your CSS. Your users control the device (and, thereby, its processor speed, RAM, etc.). Depending on the device, your users might choose the operating system, browser, and browser version they use. Your users can decide which add-ons they use in the browser. Your users can shrink or enlarge the fonts used to display your site. And the Internet providers sit between you and your users, dictating the network speed, regulating the latency, and ultimately controlling how (and what part of) your content makes it into their browser. All you can do is author a compelling, adaptive experience and then cross your fingers and hope for the best.

The fundamental problem with viewing JavaScript as a given—which these frameworks do—is that it creates the illusion of control. It’s easy to rationalize this perspective when you have access to the latest and greatest hardware and a speedy and stable connection to the Internet. If you never look outside of the bubble of our industry, you might think every one of your users is so well-equipped. Sure, if you are building an internal web app, you might be able to dictate the OS/browser combination for all your users and lock down their machines to prevent them from modifying any settings, but that’s not the reality on the open Web. The fact is that you can’t absolutely rely on the availability of any specific technology when it comes to delivering your website to the world.

It’s critical to craft your website’s experiences to work in any situation by being intentional in how you use specific technologies, such as JavaScript. Take advantage of their benefits while simultaneously understanding that their availability is not guaranteed. That’s progressive enhancement.

The history of the Web is littered with JavaScript disaster stories. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use JavaScript or that it’s inherently bad. It simply means you need to be smart about your approach to using it. You need to build robust experiences that allow users to do what they need to do quickly and easily, even if your carefully crafted, incredibly well-designed JavaScript-driven interface can’t run.

Why No JavaScript?

Often the term progressive enhancement is synonymous with “no JavaScript.” If you’ve read this far, I hope you understand that this is only one small part of the puzzle. Millions of the Web’s users have JavaScript. Most browsers support it, and few users ever turn it off. You can—and indeed should—use JavaScript to build amazing, engaging experiences on the Web.

If it’s so ubiquitous, you may well wonder why you should worry about the “no JavaScript” scenario at all. I hope the stories I shared earlier shed some light on that, but if they weren’t enough to convince you that you need a “no JavaScript” strategy, consider this: The U.K.’s GDS (Government Digital Service) ran an experiment to determine how many of its users did not receive JavaScript-based enhancements, and it discovered that number to be 1.1 percent, or 1 in every 93 users.7,8 For an ecommerce site like Amazon, that’s 1.75 million people a month, which is a huge number.9 But that’s not the interesting bit.

8 A recent Pew Research study pegged the JavaScript-deprived percentage of its survey respondents closer to 15 percent, which seems crazy. Incidentally, it also found that “the flashier tools JavaScript makes possible do not improve and may in fact degrade data quality.” See http://perma.cc/W7YK-MR3K.

9 The most recent stat I’ve seen pegs Amazon.com at around 175 million unique monthly visitors. See http://perma.cc/ELV4-UH9Q.

First, a little about GDS’s methodology. It ran the experiment on a high-traffic page that drew from a broad audience, so it was a live sample which was more representative of the true picture, meaning the numbers weren’t skewed by collecting information only from a subsection of its user base. The experiment itself boiled down to three images:

• A baseline image included via an img element

• An img contained within a noscript element

• An image that would be loaded via JavaScript

The noscript element, if you are unfamiliar, is meant to encapsulate content you want displayed when JavaScript is unavailable. It provides a clean way to offer an alternative experience in “no JavaScript” scenarios. When JavaScript is available, the browser ignores the contents of the noscript element entirely.

With this setup in place, the expectation was that all users would get two images. Users who fell into the “no JavaScript” camp would receive images 1 and 2 (the contents of noscript are exposed only when JavaScript is not available or turned off). Users who could use JavaScript would get images 1 and 3.

What GDS hadn’t anticipated, however, was a third group: users who got image 1 but didn’t get either of the other images. In other words, they should have received the JavaScript enhancement (because noscript was not evaluated), but they didn’t (because the JavaScript injection didn’t happen). Perhaps most surprisingly, this was the group that accounted for the vast majority of the “no JavaScript” users—0.9 percent of the users (as compared to 0.2 percent who received image 2).

What could cause something like this to happen? Many things:

• JavaScript errors introduced by the developers

• JavaScript errors introduced by in-page third-party code (e.g., ads, sharing widgets, and the like)

• JavaScript errors introduced by user-controlled browser add-ons

• JavaScript being blocked by a browser add-on

• JavaScript being blocked by a firewall or ISP (or modified, as in the earlier Comcast example)

• A missing or incomplete JavaScript program because of network connectivity issues (the “train goes into a tunnel” scenario)

• Delayed JavaScript download because of slow network download speed

• A missing or incomplete JavaScript program because of a CDN outage

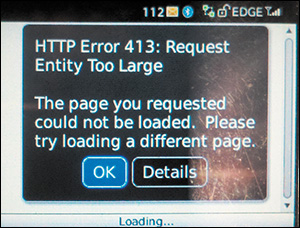

• Not enough RAM to load and execute the JavaScript10 (Figure 5.2)

10 Stuart Langridge put together a beautiful chart of these at http://perma.cc/BPN4-5XRR if you’d like to decorate your workspace.

Figure 5.2 A BlackBerry device attempting to browse to the Obama for America campaign site in 2012. It ran out of RAM trying to load 4.2MB of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. http://perma.cc/K8YS-YHDV.

That’s a ton of potential issues that can affect whether a user gets your JavaScript-based experience. I’m not bringing them up to scare you off using JavaScript; I just want to make sure you realize how many factors can affect whether users get it. In truth, most users will get your enhancements. Just don’t put all your eggs in the JavaScript basket. Diversify the ways you deliver your content and experiences. It reduces risk and ensures your site will support the broadest number of users. It pays to hope for the best and plan for the worst.

Design a Baseline

When you create experiences that work without JavaScript, you ensure that even if the most catastrophic error happens, your users will still be able to complete key tasks such as registering for an account, logging in to your site, or buying a product. This is easily achievable using standard HTML markup, links to actual pages, and forms that can be submitted to a server. HTTP is your friend. It’s the foundation of the Web, and you should embrace it.

As you’ll recall from Chapter 3, using non-native controls to handle activities such as form submission increases the number of dependencies your site has in order to deliver the right experience. Using real links, actual buttons, and other native controls keeps the number of dependencies to an absolute minimum, ensuring your users can do what they came to your site to do.

Establishing this sort of baseline for a web project built as a “single-page app”—using a front-end MVC (Model-View-Controller) framework such as Angular, Backbone, or Ember—used to be a challenge. In fact, it was the primary driver for many JavaScript programmers to call for the death of progressive enhancement, as Ember creator Tom Dale did in 2013.11

We live in a time where you can assume JavaScript is part of the web platform. Worrying about browsers without JavaScript is like worrying about whether you’re backwards compatible with HTML 3.2 or CSS2. At some point, you have to accept that some things are just part of the platform. Drawing the line at JavaScript is an arbitrary delineation that doesn’t match the state of browsers in 2013.

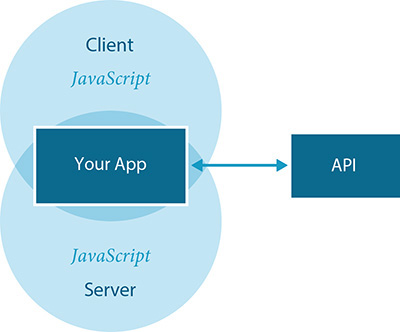

As JavaScript has become more firmly established as a server-side programming language too (thanks to node.js), it has become possible for developers to execute much of the code they send to the browser on the server. This technique, dubbed isomorphic JavaScript by Nodejitsu,12 enables the server to respond to page requests in the traditional way, delivering the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript as it traditionally would (Figure 5.3). Those HTML pages contain links to other HTML pages and forms that submit back to the server. Assuming the conditions are right, that baseline experience is then overtaken by JavaScript, and the whole experience is converted into a single-page app. It’s a fantastic example of progressive enhancement: a universally usable “no JavaScript” experience that gets replaced by a “single-page app” experience when it’s possible to do so.

Figure 5.3 A diagram of how isomorphic JavaScript works, adapted from a visualization created by Airbnb.

In 2012, Twitter was one of the first big sites to move initial rendering of its single-page app to the server (although it didn’t do it using server-side JavaScript). Twitter found that this move created a more stable experience for its users, and it also improved the speed of the site, reducing rendering time to one-fifth the time it took to get to the first render using the MVC framework.13 Airbnb transitioned to an isomorphic JavaScript approach about a year later, citing page performance and SEO as major factors in their decision.14

In the intervening years, more sites have embraced this approach, and many of the popular MVC frameworks have followed. Even Tom Dale changed his tune and released Ember FastBoot.15

Say what you will about server-rendered apps, the performance of your server is much more predictable, and more easily upgraded, than the many, many different device configurations of your users. Server-rendering is important to ensure that users who are not on the latest-and-greatest can see your content immediately when they click a link.

I couldn’t agree more. JavaScript execution in the client is never guaranteed. You should always begin with a JavaScript-less baseline, delivered by a server, and build up the experience from there. Progressive enhancement—even in the world of single-page apps and client-side MVC frameworks—just makes sense.

Program Defensively

Unlike HTML and CSS, JavaScript isn’t fault tolerant. It can’t be; it’s a programming language. If any part of the program isn’t understood, the program can’t be run. This makes authoring JavaScript a little more challenging than writing HTML and CSS. You must program defensively by acknowledging your program’s dependencies and take every precaution to minimize the fallout when one of them is not available.

As JavaScript is a programming language, you can dictate which parts of your program should run in different scenarios. By using conditional logic, you can create alternate paths for the browser’s JavaScript interpreter to follow. For example, you could create alternate paths based on what elements are in the page. Or you could create alternate experiences based on which language features the browser supports (or which it doesn’t). You could also enhance the page in different ways based on the amount of screen real estate available to you.

Conditional logic—using if, if...else, and so on—makes this possible and is an invaluable tool for ensuring your program doesn’t break. Let’s look at a few examples.

Look Before You Act

You should test for the elements you need for your interface. With the exception of html, head, and body, you can’t assume any element exists when your JavaScript program runs.

There are three main reasons why an element you expected to be on the page might not actually be there.

• Your JavaScript and HTML have gotten out of sync. This could happen if someone updated an HTML template (e.g., moving an element or removing a particular class) without realizing there was JavaScript that depended on the original markup.

• Depending on when your code is being executed, the element may not exist yet. This can happen frequently if the element in question is generated by another part of your JavaScript program. This sort of issue is referred to as a race condition because two tasks are running asynchronously and you have no way of knowing which will finish first.

• The element might have existed on page load, but it’s no longer there. This can happen if another part of the program has removed or otherwise manipulated the element. It can also happen if a browser add-on has manipulated the document (which many of them do).

Being aware of this, you can alter your JavaScript to be more flexible. Two ways of addressing these potential issues are by looking for an element before you try to do something with it and by delegating behavior rather than assigning explicit event handlers. Let’s take a look at these two approaches in more detail.

Isolate DOM Manipulation

You can elegantly avoid missing element errors by looking for an element before you try to do something with it. Let’s say you want to look for a specific element in the DOM like form.registration. You could do something like this:

var $reg_form = document.querySelector(

‘form.registration’ );

Assuming form.registration exists, $reg_form would now be a reference to that element. But, if it doesn’t, $reg_form would be null. Knowing that, you can avoid throwing a JavaScript error by encapsulating any code related to manipulating $reg_form inside a conditional.

if ( $reg_form ) {

// hooray, we can do something with it now.

}

The null value is falsey, meaning that in a conditional like this, it evaluates as false. If document.querySelector successfully collected an element, its value would be truthy, and the conditional would evaluate as true.

Delegate Behavior

If you’re looking to add a custom behavior to an interaction with an HTML element (a.k.a. an event handler), you can use the event model to your advantage and avoid missing element issues altogether. Let’s continue looking at form.registration and say you want to do something when it’s submitted. You could look for the element (as I did earlier) and then attach the event handler to that element using addEventListener or onclick. Alternately, you could also listen for the event further up in the DOM, such as on the body element.

document.body.addEventListener( ‘submit’, function(e) {

if ( e.target &&

e.target.matches( ‘form.registration’ ) ) {

// do something with the form submission

}

}, false );

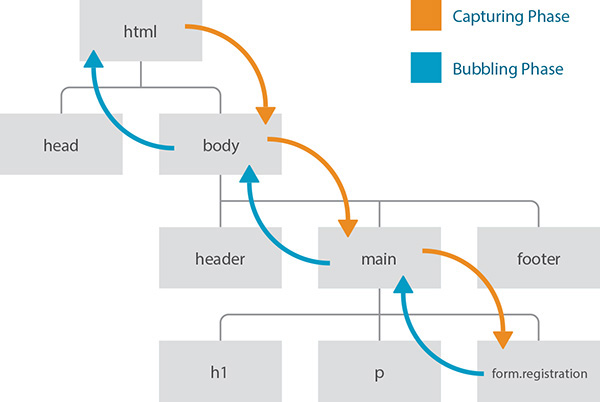

This approach is called event delegation, and the reason it works is that events move up and down the DOM tree in the event capturing and event bubbling phases, respectively (Figure 5.4). So, the submit event of a form hits the html element (as the root node), then the body element, then however many other ancestor elements exist between the body and form.registration, and then finally the form itself. That’s the event capturing phase. Then it does the whole thing in reverse, starting with the form and moving ancestor by ancestor up the DOM tree to the html element. That’s the bubbling phase. Since the third argument in this method call is false, the event handler will execute only on the bubbling phase.

Figure 5.4 The W3C event model indicating the capturing (orange) and bubbling (blue) phase of an event.

The beauty of this approach is that without form.registration in the DOM, no errors are encountered. When it is available—even if that happens after the listener is registered—the event handler is in place to do whatever it needs to when the form is submitted. As an added bonus, if you wanted to apply the same event-handling logic to multiple elements on the page, you could do it once on a shared ancestor rather than assigning individual event handlers for each element. A great use case for this is a sortable list, where you can assign the handler on the list container (e.g., ol.sortable) rather than on the individual list items themselves.

The downside to this approach is that, with certain events, running an event listener at such a high level can negatively affect performance. Imagine if event-handling code had to run and the conditionals inside it had to be evaluated every time someone clicked an element on the page. Depending on the complexity, that could make the experience slow or laggy. Whenever possible, assign event delegation as close to the element you want to control as you can (as in the example of the sortable list container earlier).

Test for Feature Support

You’ve seen a couple of examples of where conditionals are excellent for isolating code for use with specific elements, but they’re also extremely useful when it comes to using new (or newish) JavaScript features. Consider this bit of JavaScript:

if ( ‘addEventListener’ in window ) {

// we can use addEventListener

}

This code tests for whether the window object contains a member named addEventListener. If this sounds familiar, it’s because I covered this same concept, feature detection, with CSS in the previous chapter (@supports). This form of logic is even more critical in JavaScript because, as a programming language, JavaScript is not fault tolerant. Feature detection is necessary for creating robust programs in JavaScript.

The addEventListener method is the modern standard for attaching event handlers. Back during the height of the browser wars, however—before addEventListener was standardized—Microsoft developed a competing method called attachEvent that did largely the same thing. Until the release of IE 9 in 2011, addEventListener was completely unavailable in their browser. To enable the same interactions in IE versions prior to that and in every other browser, developers were forced to support both methods. So, instead of the example shown earlier, you’d see something like this:

if ( ‘addEventListener’ in window ) {

// code using addEventListener

} else if ( ‘attachEvent’ in window ) {

// code using attachEvent

}

This update creates two alternate paths (or forks in the program) for the browser’s JavaScript interpreter to take. The order is important because you could have a browser that supports both (e.g., IE 9–10), and you should always favor the standardized method (addEventListener) over the proprietary one (attachEvent). Thankfully, attachEvent was removed from IE in version 11, so it will soon be a thing of the past, but this is still a good example of feature detection.

It’s worth noting that some features are challenging to test. Sometimes browsers offer partial support for new feature or have otherwise incomplete implementations. In these cases, browsers may lie about or somehow misrepresent their support when you only test for the existence of an object or method. For instance, currently Safari understands HTML5 form validation (i.e., it pays attention to required attributes, pattern, etc.), and it can tell you, via the JavaScript API, that a field is not valid, but it won’t stop the form from being submitted.16 Testing for support of the required attribute, for instance, doesn’t give you the full picture. In cases like this, your tests need to be more robust. For example, you might need to try using the feature or setting the property and then test to see whether the outcome is what you expected. Whole JavaScript libraries have been developed to assist you with more complex feature detection. Modernizr17 is probably the most popular and fully featured of these testing libraries.

Feature detection enables you to isolate blocks of code that have a particular feature dependency without running the risk of causing the interpreter to fail. A JavaScript error, you’ll recall, was what took down Gawker Media’s whole network of sites. Feature detection is another way to reduce the likelihood that will happen on your site.

Make Sure Libraries Are There

One of the critical flaws of so many sites that succumbed to the Sky Broadband jQuery fiasco is that their code did not test to make sure the jQuery library had loaded before trying to run. You see this pattern a lot in jQuery plugins and example code, but this is a potential issue for any JavaScript library.

The HTML5 Boilerplate18 uses an interesting approach to maximize the potential for properly loading jQuery.

<script src="http://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>window.jQuery || document.write(‘<script src="js/vendor/jquery-1.min.js"><\/script>’)</script>

The first script element attempts to download jQuery from Google’s CDN. The second script element contains JavaScript to test whether the jQuery object is available. If it isn’t (which means the CDN version of jQuery didn’t load), the JavaScript writes in a third script element pointing to a copy that exists locally on the server. The reasoning behind this approach is that when many sites use this pattern, there’s a good chance your users already have a version of jQuery from the Google CDN in their cache. That means it won’t need to be downloaded again (leading to faster page load). The CDN version will be requested if they don’t have it, and if that request fails, the copy stored on the domain’s server will be used. This is a really well-thought-out pattern.

That said, it’s still possible that jQuery (or whatever library you use this pattern with) might not be available. Perhaps the user lost all network connectivity while going through a tunnel or walking out of their mobile provider’s coverage zone; life happens, and you need to plan accordingly. So, before you attempt to use a library in your JavaScript, test to make sure it’s there. You could, for instance, include something like this at the top of your jQuery-dependent script:

if ( typeof(jQuery) == ‘undefined’ ) {

return;

}

That would cause the program to exit if jQuery isn’t available. With simple tests such as this in place, you can rest assured that your users can meet the minimum dependency requirements your JavaScript program has before their absence causes a problem.

Establish Minimum Requirements for Enhancement

The BBC uses feature detection in an interesting way. It runs tests for several features at once and uses them to infer the caliber of browser it’s dealing with.

if ( ‘querySelector’ in document &&

‘localStorage’ in window &&

‘addEventListener’ in window ) {

// an "HTML5" browser

}

This conditional checks to see whether all three tests return true before executing the program within the curly braces. If the browser passes these tests—the BBC calls that “cutting the mustard”19—it goes ahead and loads the JavaScript enhancements. If not, it doesn’t bother.

There’s a reason the BBC has chosen these three specific feature tests.

• document.querySelector: The code for finding elements (so you can then do something with them) takes up a sizable chunk of any JavaScript library. If a browser supports CSS-based selection, that simplifies the code needed to do it and makes it unnecessary to have as part of the library (thereby saving you in both file size and program performance).

• window.addEventListener: I talked about this one already. Event handling is the other major component of nearly every JavaScript library. When you no longer need to support two different event systems, your program can get even smaller.

• window.localStorage: This feature allows you to store content locally in the browser so you can pluck it out later. Its availability can aid in performance-tuning a site and dealing with intermittent network connectivity.

Each project is different and has different requirements. Your project may not use localStorage, for instance, so this bit of logic might not be appropriate for you, but the idea is a sound one. If you want to focus your efforts on enhancing the experience for folks who have the language features you want to use, test for each before you use them. Never assume that because one feature is supported, another one must be as well; there’s no guarantee.

It’s worth noting that you can use an approach such as this to establish a minimum level of support and then test for additional features within your JavaScript program when you want to use them. That allows you to deliver enhancements in an à la carte fashion—delivering only the ones that each specific user can actually use.

Finding ways to avoid introducing your own JavaScript errors is the first step toward ensuring that the awesome progressive enhancements you’ve created stand any chance of making it to your users.

Cut Your Losses

Some browsers, particularly older versions of IE, can be problematic when it comes to JavaScript. The event model differences are just one example of the forks you need in your code to accommodate them. Sometimes it’s best to avoid delivering JavaScript to these browsers at all. Thankfully, there’s an easy way to do this using another proprietary Microsoft technology: Conditional Comments.20 Conditional Comments are exactly what you’d expect: a specifically formatted HTML comment that is interpreted by IE but is ignored by all other browsers (because it’s a comment). Here’s a simple example:

<!--[if lte IE 6]>

Only IE 6 and earlier see this text.

<![endif]-->

This appears as merely a comment to any non-IE browser because it starts with <!--. IE, however, evaluates the conditional before deciding what to do with the contents (in this case, delivering them to IE 6 and older). Conditional Comments work in IE 9 and earlier; Microsoft stopped supporting them in IE 10.

But wait, I was talking about hiding content from older versions of IE, not showing it to them. Interestingly, you can do that too. The code is just slightly more complex.

<!--[if gte IE 8]><!-->

IE 8+ and all non-IE browsers see this text.

<!--<![endif]-->

To break this down for you, a comment is started by the <!--. If the browser supports Conditional Comments, the condition is evaluated. If it evaluates as true, the contents are revealed. For browsers that don’t support Conditional Comments, the contents need to be revealed too, so the opening bit of the Conditional Comment needs to be closed with -->. Sadly, browsers that support Conditional Comments will display the --> as text, but putting <! first hides it (as a comment). Next up is the content that will be exposed in IE 8+ and all other browsers. Finally, the last line closes the Conditional Comment, hiding its nonstandard syntax from other browsers by putting it in a comment using <!--. Phew!

Taken all together, you can use this setup to avoid delivering JavaScript to older/problematic versions of IE altogether:

<!--[if gte IE 9]><!-->

<script src="enhancements.js"></script>

<!--<![endif]-->

With this code in place, your JavaScript would be delivered to IE 9–11, Microsoft Edge, and every other browser. IE 8 and older would get the “no JavaScript” experience. Since you intentionally designed an experience for that scenario—you did, right?—your users can still do what they need to do. As an added bonus, you’re spared the headache of trying to debug your JavaScript in those browsers. It’s yet another perfect example of supporting as many users as you can while optimizing the experience for folks with more capable browsers.

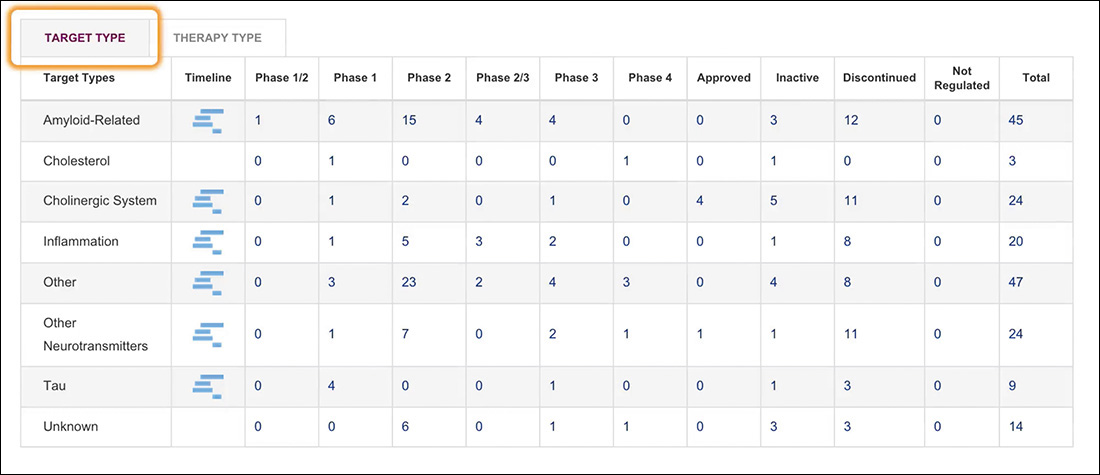

Build What You Need

As I mentioned in Chapter 3, AlzForum uses a tabbed interface, but the baseline markup is not the markup required for a tabbed interface. The baseline markup is simply a container that is classified as a tabbed interface. The JavaScript program it uses21 looks for any elements classified in such a way and then builds a tabbed interface dynamically, based on their contents.

By reading in the contents and parsing the document outline, the script generates the following:

• A container for the tabs

• As many tabs as are necessary

• As many content panels as are necessary

It assigns the appropriate role values to make the interface appear as a tabbed interface to assistive technology: tablist, tab, and tabpanel, respectively.

The program uses another set of ARIA attributes to establish relationships between the related elements. First, it adds aria-controls to the tab. The aria-controls attribute indicates that the tab controls the element referenced in the value of the attribute. In this case, the attribute’s value is set to reference the id the program generated onto the corresponding content panel. Second, it adds an aria-describedby attribute that operates just like aria-controls but indicates that the tab is described by the contents within the referenced content panel.

To make the connection in the other direction, each content panel is given an aria-labelledby attribute with a value pointing to the id generated onto the corresponding tab. As you’d expect, aria-labelledby is used to indicate the element that labels the current element.

Here’s a simplified version of the script-generated markup so you can see the relationships:

<ol role="tablist">

<li role="tab" id="tab-0"

aria-controls="tabpanel-0"

aria-describedby="tabpanel-0">Target Type</li>

<li role="tab" id="tab-1"

aria-controls="tabpanel-1"

aria-describedby="tabpanel-1">Therapy Type

</li>

</ol>

<section role="tabpanel" id="tabpanel-0"

aria-labelledby="tab-0">

<!-- panel 1 contents -->

</section>

<section role="tabpanel" id="tabpanel-1"

aria-labelledby="tab-1">

<!-- panel 2 contents -->

</section>

Without the JavaScript necessary to make the tabbed interface behave like a tabbed interface, these ARIA roles and properties would be pointless. As with the extra markup necessary to create the interface, JavaScript is the perfect place to add these accessibility enhancements.

As I discussed in Chapter 3, whenever possible, you should look for opportunities to extract JavaScript-dependent markup from the page and generate it programmatically. It reduces page weight, reduces the possibility of confusing users by including markup they don’t need, and eases maintenance because all code necessary for the component to operate is managed in one place.

Describe What’s Going On

In addition to defining the purpose elements are serving (using role) and the relationships between elements (using properties such as aria-describedby), ARIA also gives you the ability to explain what’s happening in an interface via a set of attributes referred to as ARIA states. When creating a JavaScript-driven widget, these three components are invaluable. They enhance the accessibility of your interfaces by mapping web-based interactions to traditional desktop software accessibility models already familiar to your users.

The tabbed interface script on AlzForum (Figure 5.5) uses several ARIA states to inform users of what’s happening in the interface while they are interacting with it. The first of these is aria-selected, which indicates which tab is currently active. When the page loads and the script constructs the tabbed interface, the first tab is active, so aria-selected is set to “true” on that tab. The other tabs are not active, so aria-selected is “false” on them. Here’s a simplified example of one of the tab lists:

<ol role="tablist">

<li role="tab" aria-selected="true" ...>Target

Type</li>

<li role="tab" aria-selected="false" ...>Therapy

Type</li>

</ol>

When a user activates the second tab in order to display its related contents, that activated tab becomes aria-selected="true", and the other tab is set to aria-selected="false". At the other end of the tabbed interface, a similar switch is happening but with another set of ARIA states.

When the interface initially loads and the first content panel is displayed, that panel is aria-hidden="false" because it’s visible. All the other content panels are set to aria-hidden="true". When a new tab is activated, the new panel is set to aria-hidden="false", and the previously visible one is aria-hidden="true".

With these roles, properties, and states in place, assistive technologies such as screen readers can identify this markup as a tabbed interface and explain the interface to the user. For instance, ChromeVox (Google’s screen reader add-on for Chrome) would say the following when this markup is encountered:

Tab list with two items. Target Type tab selected, one of two.

When the user navigates to the second tab, it would read the following:

Therapy Type tab selected, two of two.

When activating the content panel, it would say the following:

Therapy Type tab panel.

From there, the user can instruct the screen reader to continue reading the contents of the content panel. It’s a pretty nice experience without requiring too much of you, the programmer. The straightforward, declarative nature of ARIA is one of its greatest strengths.

Write Code That Takes Declarative Instruction

Declarative code, as in code you can understand by reading it, is incredibly useful from a maintenance standpoint. It can make it obvious what’s happening and makes it easy for a team to collaborate.

In the AlzForum example, the developers used a class to indicate a tabbed interface should be created. That’s declarative, but it can also create confusion, especially if there is a reason the tabbed interface should not be created. Thankfully, there is another option for providing declarative instruction: data attributes.

Data attributes are a completely customizable group of attributes that begin with data-. With that prefix, you can create whatever attribute names you want, such as data-turnitup or data-bring-the-noise. You have carte blanche to name them whatever makes you happy. That said, it’s a good idea to use a name that’s intuitive as a courtesy to your fellow developers (or you, a few weeks removed from this project). It’s also considered a best practice to separate words with hyphens.

In the case of AlzForum, it might have made more sense to give the container a data attribute of data-can-become="tabbed" or data-tabbed-interface; it wouldn’t even need to be given a value. The script could then look for that indicator instead of the class.

var $container = document.querySelectorAll(

‘[data-can-become=tabbed]’ );

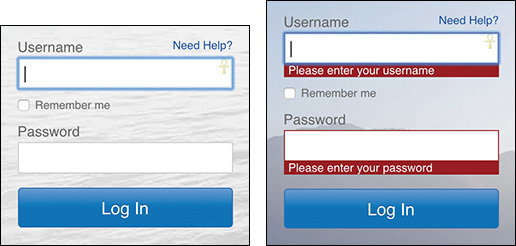

There are many hugely beneficial ways to use data attributes. On Fidelity’s website,22 they use data attributes to hold the form validation error message strings. Here’s a simplified excerpt from their login form:

<input type="password" name="PIN"

required="required" aria-required="true"

data-msg-required="Please enter your password"

data-msg-invalid="This field is not properly formatted"

>

The validation script, jQuery Validation,23 uses two data attributes to provide feedback to users when either they forget to fill in the password (data-msg-required) or the value they supply isn’t valid (data-msg-invalid). By taking this approach, the actual JavaScript program does not need to contain these messages (Figure 5.6), nor does it need to be updated when the wording needs to change. This loose coupling of logic and messaging leads to better maintainability.

Figure 5.6 A login form with validation error messages on Fidelity’s website. View the video of it in action at http://perma.cc/H83U-2M3Y.

Data attributes are accessible in your JavaScript via an element’s dataset property. In the case of the Fidelity code, you could write something like this to access them:

var $field = document.querySelector( ‘[name=PIN]’ ),

required_msg = $field.dataset.msgRequired,

invalid_msg = $field.dataset.msgInvalid;

Note that the data attributes are automatically coerced into “camel case”—where letters immediately following a hyphen are capitalized and the hyphens are removed—as properties of the dataset.

One final note on data attributes: since these are declarative instructions that are generally scoped to one use case, it’s a good idea to prefix every data attribute related to that use case identically. So if you have a bunch of data attributes related to a tabbed interface, make your attributes start with data-tab-interface-, data-tabs-, or similar. This will reduce the possibility of name collisions with other scripts.

You can see this form of “namespacing” in use on the container for another tabbed interface on AlzForum’s Mutations database page.24

<div class="tabbed-interface"

data-tab-section="[data-zoom-frame]"

data-tab-header=".pane-subtitle"

data-tab-hide-headers="false"

data-tab-carousel

>

<!-- contents to be converted -->

</div>

These various data attributes all provide additional instruction to the tabbed interface program to configure the final output.

When used well, declarative data attributes can make the progressive enhancement of your pages even easier by reducing the initial development and ongoing maintenance overhead of your programs. Data attributes make it easier to build more generic programs that pay attention to declarative configuration instructions, and they also help you reduce the overall volume of JavaScript code required to bring your interface dreams into reality.

Adapt the Interface

If you happened to load the tabbed interface example from AlzForum on a small screen, you might have noticed that the experience isn’t terribly awesome (Figure 5.7). The table-based content in the content panels gets linearized for a more mobile-friendly layout (using a max-width media query and some clever generated content), but the tabs remain and continue to allow the user to toggle between the two different content panels. This experience could certainly be improved.

One way to improve the experience might be to simply allow it to remain linearized on smaller screens. To do that, the script could be updated to check the available screen width when the page is rendering (and again on window resize, just in case). If the browser width is above a certain threshold, the tabbed interface could be generated. If not, the content could be left alone or the tabbed interface could be reverted to the linearized version of the content.

This allows you to provide three experiences of the interface:

• Headings with tables for “no JavaScript” scenarios without media query support

• Headings with linearized tables for “no JavaScript” scenarios with media query support and a narrow screen width

• A tabbed interface for users who get the JavaScript enhancement and are on a wide-enough screen

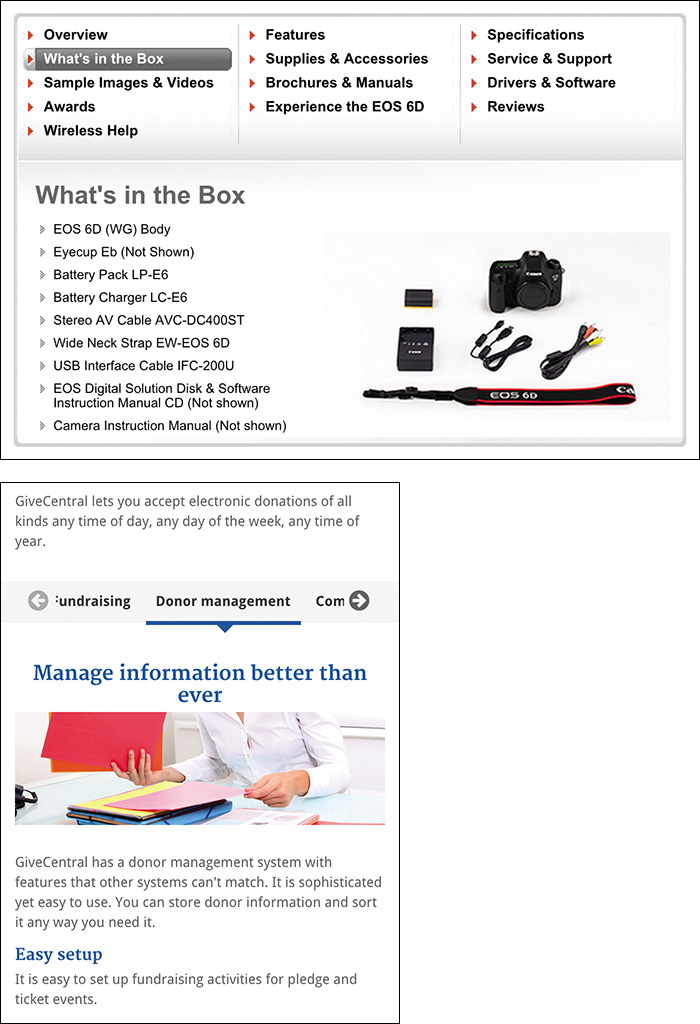

But where do you set the threshold? You could set it based on some arbitrary number, but there are instances when the screen width may be “big enough” to handle a tabbed interface but it isn’t big enough to allow all the tabs to sit nicely side by side. Then you have two choices.

• Keep the tabs on one line and make users scroll to see additional ones that don’t fit.

• Stack the tabs.

As Figure 5.8 demonstrates, neither results in a particularly good experience for your users. The Canon example25 shows how stacked tabs can run the risk of not looking like navigation tools. Give Central’s horizontally scrolling tabs26 have the potential to cut off content, rendering it less useful.

Figure 5.8 Above: Three columns of stacked tabs on Canon’s page about the EOS D6 camera. Left: Horizontally scrolling tabs on Give Central.

The horizontal scrolling tabs could also end up scroll jacking the page. Scroll jacking is when something other than the expected scroll behavior happens when you are scrolling a page. In the case of some scrolling tab implementations, when your mouse cursor ends up over one while scrolling, the vertical scroll stops, and the tabs begin scrolling horizontally.

So, if neither of those two options works well, what’s left? Not setting a fixed threshold.

Instead of checking an arbitrarily predefined threshold against the browser width, why not test the width required for the tabs themselves? It’s inconsequential to generate a dummy tab list and inject an invisible version of it into the page for a fraction of a second to determine its display width. Then you can compare that value against the available screen real estate and determine whether to load the tabbed interface. As an added bonus, this approach will let each tabbed interface self-determine whether it should be created, providing users with the most appropriate experience given the amount of screen real estate.

Consider Alternatives

So, on the narrow screen, this approach gives AlzForum’s users a linearized view of the content. That’s a fantastic baseline, but tabs are an excellent enhancement for reducing the cognitive load heaped on users by incredibly long pages. Is there a way to enhance the experience for the narrow screen too? Sure there is.

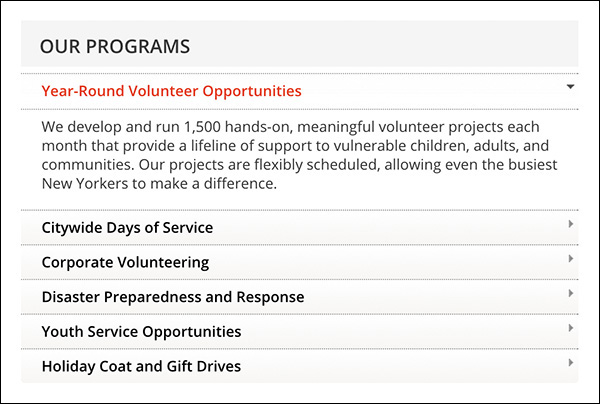

Accordion interfaces (like the one in Figure 5.9) act similarly to tabbed interfaces—they hide content until it is requested by the user. An accordion might make a good alternative to a tabbed interface when there isn’t enough room to fit the tabs horizontally across the screen. A few small tweaks to the JavaScript program could make that happen quite easily.

Figure 5.9 An accordion interface on NewYorkCares.org.

Taking it a step further, you may recall that the details and summary elements create a native accordion in browsers that support them.27 You could test for that option and convert the linear markup into a series of details elements if the browser supports it in order to reduce the number of JavaScript events running on the page.

As I’ve said many times before, experience isn’t one monolithic thing. You can use JavaScript to progressively enhance your websites, build incredibly nimble and flexible interfaces, and provide the most appropriate experiences for your users, tailored to their needs and capabilities.

Apply No Styles Before Their Time

When you are creating JavaScript-driven interfaces like those I’ve been discussing, it’s tempting to style the markup to look like the interface from the get-go. That’s a mistake. Continuing with the tabbed interface example, imagine coming to a page and seeing something that looks like a tabbed interface but doesn’t actually work like one. That would be frustrating, right? For this reason, you should find some mechanism for indicating that the coast is clear and it’s safe to apply your widget-related styles. Perhaps you can have JavaScript add a class or data attribute somewhere further up the DOM tree and use that as a switch to apply the styles. Though not specifically widget-related, this is precisely what Adobe Typekit28 does.

Plant a Flag

Typekit is a service that enables you to embed any of a number of high-quality fonts on your website. The code it gives you to embed the fonts is a small JavaScript that verifies your domain’s right to include the typefaces you’re requesting (for licensing purposes). If your site is allowed to use the fonts, the JavaScript injects a link element that points to a CSS file with @font-face blocks for each typeface. When the JavaScript program has run its course, it adds a class of wf-active to the html element.29 This class acts as a flag to indicate that fonts are loaded and everything is OK.30

29 Typekit’s JavaScript actually adds numerous class names during its life cycle: wf-loading while it gets started, wf-active when it finished successfully, and wf-inactive if something goes wrong. You can read more about these classes and other “font events” at http://perma.cc/4G59-LTWR.

30 Typekit gets bonus points for using a unique prefix (wf-) to reduce potential collision with other “active” class names.

This approach allows you to specify alternate fallback fonts if something goes wrong.

.module-title {

/* default styles */

}

.wf-active .module-title {

/* Adobe Typekit enhanced styles */

}

You may be wondering why you’d want to do something like that when CSS provides for font stacks31 that automatically support fallback options. In many cases, you won’t need to do this, but sometimes the font you are loading has different characteristics or weights than the “web-safe” fallback options defined in your font stack. In cases like that, you may want your baseline type to be sized differently or have different letter-spacing or line-height settings. You can’t fine-tune fonts in the same way with only a font stack.

Capitalize on ARIA

When you are dealing with an interface that maps well to a dynamic ARIA construct (e.g., tabbed interfaces, tree lists, accordions), you can keep things simple and use the ARIA roles and states as your selectors. AlzForum uses this approach for its tabbed interface.

[role=tablist] {

/* styles for the tab container */

}

[role=tab] {

/* styles for tabs */

}

[role=tab][aria-selected=true] {

/* styles for the current tab */

}

[role=tabpanel] {

/* styles for the current content panel */

}

[role=tabpanel][aria-hidden=true] {

/* styles for the other content panels */

}

This approach is an alternative to using a class or data attribute as a trigger for your styles, but it operates in much the same way if you are adding these roles and states dynamically (like you should be).

Enhance on Demand

Just as you should be selective about when you apply certain styles, you can be selective about when you load content and assets that are “nice to have.” I first mentioned this concept, called lazy loading, in Chapter 2 in my discussion of thumbnail images on newspaper sites. The idea behind lazy loading is that only the core content is loaded by default as part of the baseline experience. Once that baseline is in place, additional text content, images, or even CSS and JavaScript can be loaded as needed. Sometimes that need is user-driven; other times it’s programmatic.

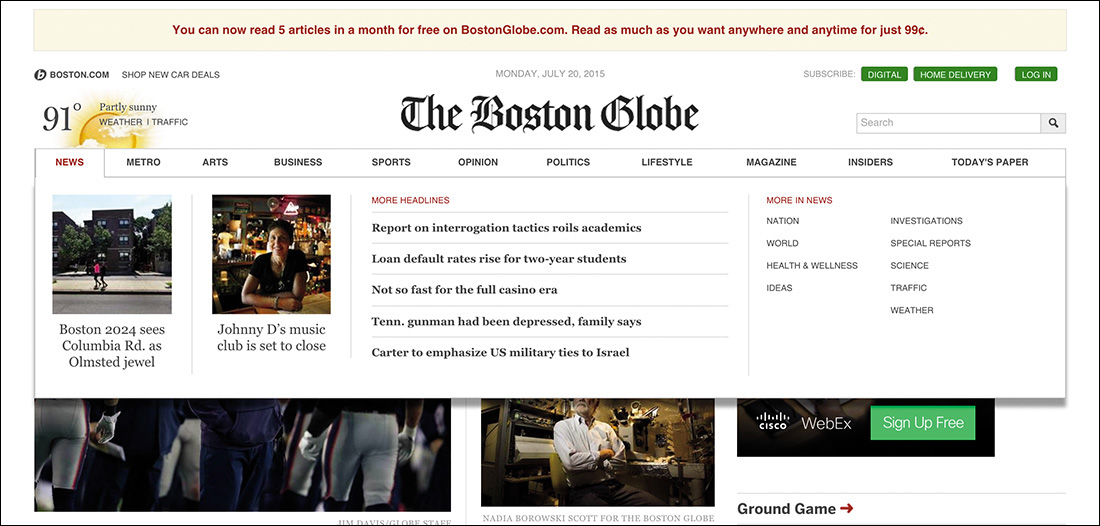

The Boston Globe website, for instance, uses lazy loading to inject large content drawers for each of its main navigation items (Figure 5.10). These drawers highlight numerous stories, some of which include thumbnail images. This content is useful but not necessary for every user who comes to the site. In fact, these drawers are really useful only if a user can hover over the navigation menu. For these reasons, the markup for these drawers is lazy loaded once the page is finished loading and only if the screen is larger than 788px and the browser supports hover events.

Figure 5.10 The Boston Globe uses lazy loading to inject promotional content drawers into the page. They are revealed when hovering the main navigation items.

This approach often gets used for other common types of supplemental content, such as related items and reviews in ecommerce or comments on a blog. That said, the benefits of lazy loading are not limited to content. Web design consultancy The Filament Group wrote a lengthy post about how it uses lazy loading to improve page-load performance.32 The approach inserts critical CSS and JavaScript into the page within style and script elements, respectively. It uses two JavaScript functions, loadCSS and loadJS, to asynchronously load the remaining CSS required to render the page and any additional JavaScript enhancements. Their approach also places a link to the full CSS file within a noscript element in order to deliver CSS in a “no JavaScript” scenario. Of course, as you learned from the GDS experiment, noscript content is not always available when JavaScript fails.

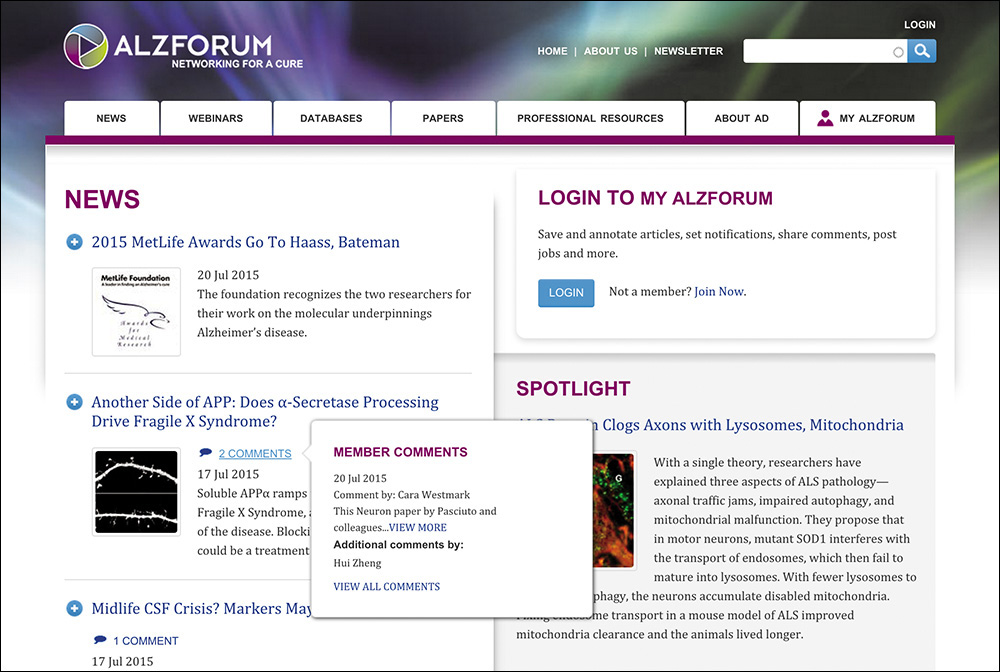

AlzForum also uses lazy loading in a few places on its site. One particularly interesting implementation is on the home page,33 where it lazy loads comment preview tooltips for its news teasers (Figure 5.11). Each comment link includes a reference to the URL for the tooltip markup in a data attribute.

<a href="node/459071/#comments"

data-tooltip="/api/brf_comments/hover_comments?id=459071">2 comments</a>

With that declarative markup in place, it would have been easy to write some JavaScript to load the tooltip content when a user hovers the link. To improve the site’s performance, AlzForum might even have considered looking for all the elements with data-tooltip attributes, looping through the list, and loading the associated tooltip content in anticipation of a user wanting it. But AlzForum went even a step beyond that and wrote code that collects the data tooltip URLs and then combines them into a single request. The API responding to the request can look for multiple id values and return the markup for all the tooltips. The JavaScript then splits up the returned markup and assigns each tooltip to its respective link. This approach is incredibly efficient—a single request has far less overhead than the eight to ten that would be required if they were gathered individually.

Lazy loading embodies the spirit of progressive enhancement. It allows you to identify optional content and code, loading it only when it makes sense to do so. It’s also an approach that drastically improves your users’ experiences by enabling your website to be rendered faster. In Chapter 6, you’ll explore another lazy loading technique in even greater depth.

Look Beyond the Mouse

When it comes to interaction, we tend to be very mouse-focused. We design small buttons and links, closely grouped together. We listen for “click” events predominantly. And we often ignore the ways that nonmousing or multimodal users interact with our pages. Progressive enhancement asks us to look for every opportunity to enhance a user’s experience, which means embracing more than just the mouse.

Empower the Keyboard

With the pervasiveness of the mouse and an increased reliance on touchscreens, it’s easy to forget about the humble keyboard, but that would be a critical mistake. The keyboard is an incredibly useful tool and is the standard interface for vision-impaired users and power users alike. When it comes to the keyboard, we’ve learned a great deal in the last few years. First, we realized that access keys were a good idea in theory but not so great in practice.34 Second, we realized that overzealous application of the tabindex attribute could get your users jumping (and not in a good way).35 But the most important thing we’ve discovered is that we can use JavaScript to “juggle” tabindex values in order to streamline a user’s path through a complex widget such as a tabbed interface or an accordion.

So, what exactly is tabindex juggling? Well, sometime in 2005 (it’s hard to pin down the exact origin), we discovered that assigning tabindex="-1" to an element would remove that element from the default tab order of the document.36 Interestingly, despite being taken out of the document’s tab order, the element remained focusable via JavaScript (using element.focus()). This opened up a lot of possibilities for controlling a user’s experience.

36 This was especially interesting because, according to the W3C spec, tabindex should accept values only between 0 and 32767. Yeah, you read that right: 32767.

Let’s walk through a scenario, revisiting the tabbed interface from AlzForum.

1. A user arrives at the tabbed interface and presses the Tab key on the keyboard, bringing focus to the first tab (which is associated with the visible content panel).

2. Pressing the Tab key again moves focus out of the tabbed interface and to the next piece of focusable content (e.g., a link, form field, or any element with a tabindex of 0 or higher).

3. Holding Shift while hitting the Tab key returns the user to the tab list and restores focus to the currently active tab.

4. Using the arrow keys, the user can move forward and backward through the tabs in the tab list.

5. Hitting the Enter key at any point while navigating through the tab list brings focus to the content panel associated with the currently focused tab.

This is all made possible with tabindex juggling. Here’s how this interaction becomes possible:

1. By assigning a tabindex of -1 to every tab and tab panel, you remove them from the default tab order of the page.

2. Going back and reassigning a value of 0 to the currently active tab restores it to its default position in the tab order.

3. Using JavaScript, you can dynamically adjust the tabindex value of each tab as a user moves left or right and up or down on the keyboard. You do this by changing the destination tab to a tabindex of 0 and giving the previously selected one a tabindex of -1.

4. The content panels always have a tabindex of -1, which means a user can focus them only via an interaction that involves JavaScript (which sits by listening for the Enter key to be pressed).

Juggling tabindex may sound complicated, but it’s really not. In the tab-swapping scenario, it can be as simple as this:

old_tab.setAttribute( ‘tabindex’, ‘-1’ );

new_tab.setAttribute( ‘tabindex’, ‘0’ );

Enhance for Touch

Since the advent of the iPhone, touch has become an important interaction to consider, but touch didn’t start there. We’ve had touchscreens since the mid-1960s. We’ve had them in portable devices since way back in 1984 when Casio introduced the AT–550 watch37 and in mobile phones since IBM announced the Simon38 in 1993. But things definitely took a massive leap forward when Apple released the iPhone in 2007.

37 That watch was pretty crazy. It allowed you to trigger the calculator function by tapping in the lower-left corner of the watch face. You could then draw the numbers and operands you wanted to use in your calculation: http://perma.cc/A78S-MC25. Could it have been the first smart watch?

38 The IBM Simon was the first combination of a cellular telephone and a touchscreen. It was also a personal digital assistant (PDA) and supported sending and receiving email.

At the time, most of us were used to designing interactions with a continuously available mouse pointer in mind. When someone browses the Web with their finger, we don’t have a constant sense of where they are in the interface. We don’t have the ability to sense when they are hovering over an element—events such as mousemove, mouseenter, and the like are simply irrelevant.

Thankfully, the click event already existed. It does a good job of unifying keyboard- and mouse-based activation of elements such as links and buttons. The Safari browser for iOS triggers click events as well, albeit with a 300ms delay.39 The reason for the delay is to allow for a user to double-tap the screen to zoom.

39 Other touch devices do it, too. Here’s a good overview and workaround: http://perma.cc/9DVB-CYRM.

Accompanying the release of the iPhone were a handful of touch-related events: touchstart, touchend, touchmove, and touchcancel. The touchend event, in particular, became a solid alternative to click because it avoided the 300ms delay altogether.

As per usual, we began to make assumptions based on the availability of touch. Here’s an example of something I regret doing at the time:

if ( ‘ontouchend’ in window ) {

tap_event = ‘touchend’;

}

/* and later on */

element.addEventListener( tap_event, myCallback,

false );

Do not try this at home. This code assumes that click is a good baseline (which it is), but then it clobbers it as the event to look for if touch is available, assuming touch is the right event to trigger myCallback (my fake event-handler function). What if a user can do both?

You can assign both event handlers, but that’s a little cumbersome.

element.addEventListener( ‘click’, myCallback,

false );

element.addEventListener( ‘touchend’, myCallback,

false );

Unfortunately, this code would also fire myCallback twice on a device that supports both event types—the click handler version will fire 300ms behind the touchend one. To overcome that issue, you’d need to ensure the handler is fired only once, requiring even more code (and some additional abstraction).40

40 You can see this code in action on CodePen: http://perma.cc/AS4P-NCAQ.

// determine if touch is available

var has_touch = ‘touchend’ in window;

// abstract the event assignment

function assignTapHandler( the_element, callback ) {

// track whether it’s been called

var called = false;

// ensure the event has not been called already

// before firing the callback

function once() {

if ( !called ) {

callback.apply( this, arguments );

// note that it’s been called

called = true;

}

}

// attach the event listeners

the_element.addEventListener( ‘click’, once,

false );

if ( has_touch ) {

the_element.addEventListener( <touchend>, once,

false );

}

}

// finally, use the abstraction

assignTapHandler( element, myCallback );

Phew! That’s a lot to wrap your head around for something as simple as a click or tap. What if you wanted to support pen events too? If only it could be easier....

This problem is precisely what Pointer Events41 were developed to address. Pointer Events abstract pointer-based interactions—mouse, pen, touch, and whatever’s next—to a series of generic events that fire no matter what type of interaction is happening. Once you’ve caught the event, you can decide what to do with it and even whether you want to do something different based on the mode of input.

window.addEventListener(‘pointerdown’, detectInput,

false);

function detectInput( event ) {

switch( event.pointerType ) {

case ‘mouse’:

// mouse input detected

break;

case ‘pen’:

// pen/stylus input detected

break;

case ‘touch’:

// touch input detected

break;

default:

// pointerType could not be detected

// or is not accounted for

}

}

Pointer Events are still new but have gained significant traction. As I write this, Apple is the lone holdout. Ideally, that will have changed by the time you pick up this book.42

42 Can I Use would know: http://perma.cc/QQ95-6F7Y.

Don’t Depend on the Network

More and more of your users are weaving the Web into the parts of their lives when they aren’t behind a desk with a hardwired connection to the Internet. As people move around during the day, their connections bounce from cell tower to Wi-Fi hotspot to cell tower again: 4G to Wi-Fi to 3G to Edge to hotel Wi-Fi (which is absolutely in a class of its own...and not a good one). Your users move in and out of these different networks throughout the day. And, for many, at least some part of their daily travels take them into a “dead zone” where they simply can’t get a signal. Clearly, you can’t depend on the network to be there all the time, so how do you cope?

There are numerous options that make it possible to handle network issues elegantly, and they all require JavaScript. In fact, this is one area where JavaScript really brings a lot of value in terms of enhancing a user’s experience.

Store Things on the Client

Back in the early days of the Web, the only way you could store data on a user’s computer was via cookies. Cookies let you store information such as session IDs, someone’s username, or even certain preferences such as the number of items to display per page, but they aren’t practical for any substantial amount of content. Cookies are limited to 4,093 bytes in total length per domain (that’s for all cookies on the domain, not per cookie). They’re also a bit of a performance killer because each request sent by the browser includes every cookie in use by the domain receiving the request.

We needed something better. That something better came in two forms: localStorage and sessionStorage.43 These two technologies operate in the same way, but localStorage persists from session to session (i.e., it sticks around even when you’ve quit the browser application), and sessionStorage is available only for the duration of your session (i.e., while the browser is open). In both, the information you store is private to your domain, and you are limited to about 5MB of storage. I’ll focus on localStorage, but you can rest assured that sessionStorage can do the same things because they are both instances of the same Storage object.

You can detect localStorage support just like any other JavaScript language feature.

if ( ‘localStorage’ in window &&

window.localStorage !== null ) {

// It’s safe to use localStorage

}

You might be wondering why there are two conditions that need to be met before you proceed down the path of using localStorage. A user must give your site permission to store information on their machine. If they decline, window.localStorage will be null.

You can store data as string-based key-value pairs, like this:

localStorage.setItem( ‘key’, ‘value’ );

You are limited to storing strings of data, so you can’t save DOM references. You can, however, store JavaScript objects if you coerce them to JSON strings first.

localStorage.setItem( ‘my_object’,

JSON.stringify( my_object ) );

Getting them back is easy too.

var my_value = localStorage.getItem( ‘key’ ),

my_object = JSON.parse( localStorage.getItem(

‘my_object’ ) );

Just be aware that your data stores can be overwritten accidentally.

localStorage.setItem( ‘key’, ‘value’ );

// and later on or in another script

localStorage.setItem( ‘key’, ‘another value’ );

This isn’t so much of an issue if you don’t use localStorage for much or you are a one-person dev shop, but if you want to play well in the localStorage sandbox, it’s a good idea to namespace your keys. I tend to prefer prepending the JavaScript object name to the key. So if I were to use localStorage to store a reference to the currently selected tab in a tabbed interface, I might do something like this:

localStorage.setItem( ‘TabInterface.current’,

‘tab-0’ );

Alternatively, you could use a helper such as Squirrel.js that allows you to create an isolated data store within localStorage based on this idea.44

Client-side storage can be used for all sorts of helpful enhancements. Perhaps you’d like to store your CSS locally to improve performance and provide a better offline experience.45 Or maybe you simply want to cache responses given by heavy Ajax calls so you only need to make them once.46 Or maybe you want to reduce your users’ frustrations with forms and save the content as they enter it, just in case the browser crashes.47

Riffing on the form idea a bit more, you could hijack a form submission and post the form data via XMLHttpRequest. If the request fails (because the user is offline or you can’t read the server), you could capture the form data in a JSON object, squirrel it away in localStorage, and inform the user you’ll send it when the connection is back up. You could then have JavaScript poll at a certain interval to see when the connection comes back. When it does, you could submit the data and inform the user that it’s been sent. Talk about enhancing the forms experience!

You could even take this approach further and make an entire web app function offline, performing data synchronizations with the server only when a connection is available. It’s entirely possible. And if you don’t want to write the logic yourself, there are tools such as PouchDB48 that can rig it all up for you. With localStorage, the possibilities are endless. OK, that’s not really true; they’re bound by the 5MB storage limit, but I think you get my point.

Of course, localStorage is not the only option when it comes to enabling offline experiences, but it is one of the easiest ways to get started.

Taking Offline Further

If you like the ability to store structured content locally but find that localStorage is limited in terms of its power and storage space, indexedDB49 might be what you are looking for. When you work with indexedDB, your storage limit increases tenfold to 50MB. The indexedDB data store is also much more advanced than the simple key-value pairings of localStorage; its capabilities much more closely resemble what you’d expect from a traditional database. The one trade-off for this additional power and storage space is a more complex API, but it is intuitive once you understand how all the pieces fit together.

Another option worth considering is a Service Worker.50 A Service Worker is a script that is run by the browser in a separate thread from your website but that is registered and governed by your site. As Service Workers exist within the browser, they are granted access to features that would not make sense in a web-page context. Eventually this will include push messages, background sync, geofencing, and more, but Service Workers are a new idea and are starting with one feature: the ability to intercept and handle network requests, including managing the caching of resources for offline use. Previous to Service Workers, the only way we had to control what browsers cached was via the Application Cache, and it was complicated and fraught with issues.51 Service Workers should make the Application Cache obsolete.

50 The Working Draft specification is at http://perma.cc/4XRC-MH36, and you can find a good introduction to them at http://perma.cc/A6U4-2MLX.

As I am writing this, Service Workers are still in their infancy, and only Chrome has a complete implementation of the draft specification. That said, Firefox is working on one, and Microsoft is showing an interest in Service Workers as well. When they do land, Service Workers will undoubtedly be an excellent tool for enhancing your users’ experiences when the network is not available.

Finally, if the website you work on is more transactional than informational, all of this offline business can help you in another way as well: You can easily make your website installable. The W3C has been working on the Application Manifest specification52 to enable websites to become installable applications. The spec is still a draft as I am writing this, but we are already starting to see tools—like ManifoldJS53—that allow you to generate installable application wrappers for your website. These “hosted” apps already work on Android, Chrome OS, Firefox OS, iOS, and even Windows. Once installed, your website can request access to more of the operating system’s core services such as the address book, calendar, and more. Talk about progressive enhancement!

Wield Your Power Wisely

Make no mistake, progressive enhancement with JavaScript requires considerably more effort than it does with CSS or HTML. The first and most critically important thing you can do is to become familiar with all the things that can potentially demolish your JavaScript-based experiences. The more familiarity you have with them, the more steps you can take to mitigate the potential damage.

Having a solid experience in the absence of JavaScript is a good starting point because it will ensure your users will always be able to do what they came to your site to do, no matter what happens. From there, authoring your JavaScript programs defensively—detecting language features and elements you want to work with—will help you avoid introducing errors when an outside influence such as a browser plugin or ad service messes with your page.

There’s nothing wrong with setting a minimum threshold for browser support using feature detection; just be sure your choices aren’t arbitrary and accurately reflect your goals for the project. You could even take this a step further and avoid delivering JavaScript to browsers you know are particularly old or incapable of using tools such as Conditional Comments. With a JavaScript-less baseline in place, your users on unsupported browsers will still be taken care of, and you can focus on enhancing the experiences of users who have access to more modern browsers.

When you are designing JavaScript-driven widgets, don’t embed the markup in the document. Instead, use class or data attribute triggers to inform your JavaScript program that it can convert the existing markup into a specific interactive widget and enable the necessary styles. This reduces the potential for user confusion in seeing an interface that might not behave as expected, and it also gives you more flexibility to evolve the implementation over time. Use ARIA to explain the component parts of the interface and what’s happening as a user interacts with it so that your users who require the aid of assistive technology are just as well-supported as your other users. Adapt your widgets to be appropriate to the form factor, prioritizing your users’ reading experience over your JavaScript cleverness.

Finally, look for ways to increase the reach of your creations by opening them up to alternative inputs such as touch, keyboards, and pens. And recognize that even the network is not a given in our increasingly mobile world. Take advantage of the tools that allow you to improve the performance of your website through clever caching and moving more of your experience offline. Your users will thank you for it.

JavaScript is an incredibly powerful tool with the astonishing potential to drastically improve or unforgivably ruin your users’ experience. As Spider-Man’s Uncle Ben famously said, “With great power there must also come great responsibility!” Armed with a solid understanding of how to best wield the power of JavaScript, you’re sure to make smart decisions and build even more usable sites.