7. Concurrency

JavaScript was designed as an embedded scripting language. JavaScript programs do not run as stand-alone applications, but as scripts in the context of a larger application. The flagship example is, of course, the web browser. A browser can have many windows and tabs running multiple web applications, each responding to various inputs and stimuli: user actions via keyboard, mouse, or touch, the arrival of data from the network, or timed alarms. These events can occur at any point—even simultaneously—during the lifetime of a web application. And for each kind of event, the application may wish to be notified of information and respond with custom behavior.

JavaScript’s approach to writing programs that respond to multiple concurrent events is remarkably user-friendly and powerful, using a combination of a simple execution model, sometimes known as event-queue or event-loop concurrency, with what are known as asynchronous APIs. Thanks to the effectiveness of this approach, as well as the fact that JavaScript is standardized independently of web browsers, JavaScript is used as the programming language for a variety of other applications, from desktop applications to server-side frameworks such as Node.js.

Curiously, the ECMAScript standard has, to date, never said a word about concurrency. Consequently, this chapter deals with “de facto” characteristics of JavaScript rather than the official standard. Never-theless, most JavaScript environments share the same approach to concurrency, and future versions of the standard may standardize on this widely implemented execution model. Regardless of the standard, working with events and asynchronous APIs is a fundamental part of programming in JavaScript.

Item 61: Don’t Block the Event Queue on I/O

JavaScript programs are structured around events: inputs that may come in simultaneously from a variety of external sources, such as interactions from a user (clicking a mouse button, pressing a key, or touching a screen), incoming network data, or scheduled alarms. In some languages, it’s customary to write code that waits for a particular input:

var text = downloadSync("http://example.com/file.txt");

console.log(text);

(The console.log API is a common utility in JavaScript platforms for printing out debugging information to a developer console.) Functions such as downloadSync are known as synchronous, or blocking: The program stops doing any work while it waits for its input—in this case, the result of downloading a file over the internet. Since the computer could be doing other useful work while it waits for the download to complete, such languages typically provide the programmer with a way to create multiple threads: subcomputations that are executed concurrently, allowing one portion of the program to stop and wait for (“block on”) a slow input while another portion of the program can carry on usefully doing independent work.

In JavaScript, most I/O operations are provided through asynchronous, or nonblocking APIs. Instead of blocking a thread on a result, the programmer provides a callback (see Item 19) for the system to invoke once the input arrives:

downloadAsync("http://example.com/file.txt", function(text) {

console.log(text);

});

Rather than blocking on the network, this API initiates the download process and then immediately returns after storing the callback in an internal registry. At some point later, when the download has completed, the system calls the registered callback, passing it the text of the downloaded file as its argument.

Now, the system does not just jump right in and call the callback the instant the download completes. JavaScript is sometimes described as providing a run-to-completion guarantee: Any user code that is currently running in a shared context, such as a single web page in a browser, or a single running instance of a web server, is allowed to finish executing before the next event handler is invoked. In effect, the system maintains an internal queue of events as they occur, and invokes any registered callbacks one at a time.

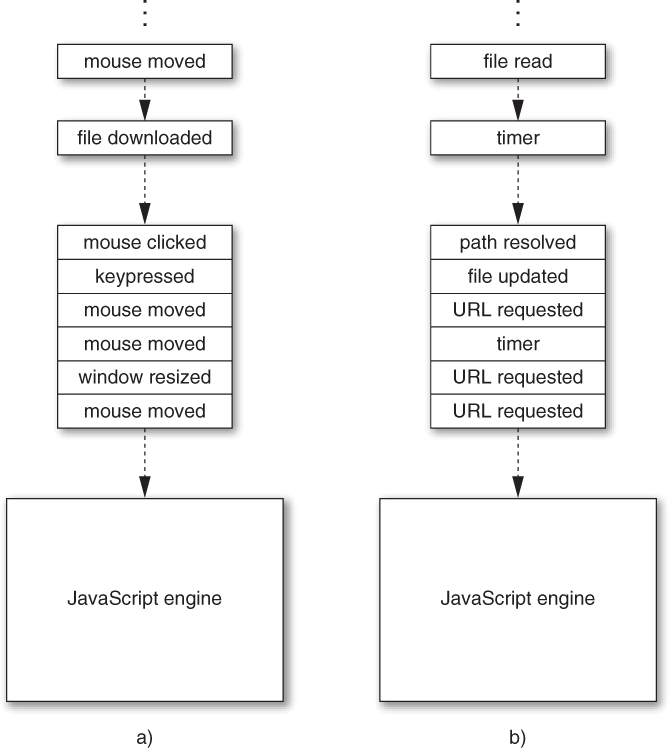

Figure 7.1 shows an illustration of example event queues in client-side and server-side applications. As events occur, they are added to the end of the application’s event queue (at the top of the diagram). The JavaScript system executes the application with an internal event loop, which plucks events off of the bottom of the queue—that is, in the order in which they were received—and calls any registered JavaScript event handlers (callbacks like the one passed to downloadAsync above) one at a time, passing the event data as arguments to the handlers.

Figure 7.1. Example event queues in a) a web client application and b) a web server

The benefit of the run-to-completion guarantee is that when your code runs, you know that you have complete control over the application state: You never have to worry that some variable or object property will change out from under you due to concurrently executing code. This has the pleasant result that concurrent programming in JavaScript tends to be much easier than working with threads and locks in languages such as C++, Java, or C#.

Conversely, the drawback of run-to-completion is that any and all code you write effectively holds up the rest of the application from proceeding. In interactive applications like the browser, a blocked event handler prevents any other user input from being handled and can even prevent the rendering of a page, leading to an unresponsive user experience. In a server setting, a blocked handler can prevent other network requests from being handled, leading to an unresponsive server.

The single most important rule of concurrent JavaScript is never to use any blocking I/O APIs in the middle of an application’s event queue. In the browser, hardly any blocking APIs are even available, although a few have sadly leaked into the platform over the years. The XMLHttpRequest library, which provides network I/O similar to the downloadAsync function above, has a synchronous version that is considered bad form. Synchronous I/O has disastrous consequences for the interactivity of a web application, preventing the user from interacting with a page until the I/O operation completes.

By contrast, asynchronous APIs are safe for use in an event-based setting, because they force your application logic to continue processing in a separate “turn” of the event loop. In the examples above, imagine that it takes a couple of seconds to download the URL. In that time, an enormous number of other events may occur. In the synchronous implementation, those events would pile up in the event queue, but the event loop would be stuck waiting for the JavaScript code to finish executing, preventing the processing of any other events. But in the asynchronous version, the JavaScript code registers an event handler and returns immediately, allowing other event handlers to process intervening events before the download completes.

In settings where the main application’s event queue is unaffected, blocking operations are less problematic. For example, the web platform provides the Worker API, which makes it possible to spawn concurrent computations. Unlike conventional threads, workers are executed in a completely isolated state, with no access to the global scope or web page contents of the application’s main thread, so they cannot interfere with the execution of code running in from the main event queue. In a worker, using the synchronous variant of XMLHttpRequest is less problematic; blocking on a download does prevent the Worker from continuing, but it does not prevent the page from rendering or the event queue from responding to events. In a server setting, blocking APIs are unproblematic during startup, that is, before the server begins responding to incoming requests. But when servicing requests, blocking APIs are every bit as catastrophic as in the event queue of the browser.

Things to Remember

• Asynchronous APIs take callbacks to defer processing of expensive operations and avoid blocking the main application.

• JavaScript accepts events concurrently but processes event handlers sequentially using an event queue.

• Never use blocking I/O in an application’s event queue.

Item 62: Use Nested or Named Callbacks for Asynchronous Sequencing

Item 61 shows how asynchronous APIs perform potentially expensive I/O operations without blocking the application from continuing doing work and processing other input. Understanding the order of operations of asynchronous programs can be a little confusing at first. For example, this program prints out "starting" before it prints "finished", even though the two actions appear in the opposite order in the program source:

downloadAsync("file.txt", function(file) {

console.log("finished");

});

console.log("starting");

The downloadAsync call returns immediately, without waiting for the file to finish downloading. Meanwhile, JavaScript’s run-to-completion guarantee ensures that the next line executes before any other event handlers are executed. This means that "starting" is sure to print before "finished".

The easiest way to understand this sequence of operations is to think of an asynchronous API as initiating rather than performing an operation. The code above first initiates the download of a file and then immediately prints out "starting". When the download completes, in some separate turn of the event loop, the registered event handler prints "finished".

So, if placing several statements in a row only works if you need to do something after initiating an operation how do you sequence completed asynchronous operations? For example, what if we need to look up a URL in an asynchronous database and then download the contents of that URL? It’s impossible to initiate both requests back-to-back:

db.lookupAsync("url", function(url) {

// ?

});

downloadAsync(url, function(text) { // error: url is not bound

console.log("contents of " + url + ": " + text);

});

This can’t possibly work, because the URL resulting from the database lookup is needed as the argument to downloadAsync, but it’s not in scope. And with good reason: All we’ve done at that step is initiate the database lookup; the result of the lookup simply isn’t available yet.

The most straightforward answer is to use nesting. Thanks to the power of closures (see Item 11), we can embed the second action in the callback to the first:

db.lookupAsync("url", function(url) {

downloadAsync(url, function(text) {

console.log("contents of " + url + ": " + text);

});

});

There are still two callbacks, but the second is contained within the first, creating a closure that has access to the outer callback’s variables. Notice how the second callback refers to url.

Nesting asynchronous operations is easy, but it quickly gets unwieldy when scaling up to longer sequences:

db.lookupAsync("url", function(url) {

downloadAsync(url, function(file) {

downloadAsync("a.txt", function(a) {

downloadAsync("b.txt", function(b) {

downloadAsync("c.txt", function(c) {

// ...

});

});

});

});

});

One way to mitigate excessive nesting is to lift nested callbacks back out as named functions and pass them any additional data they need as extra arguments. The two-step example above could be rewritten as:

db.lookupAsync("url", downloadURL);

function downloadURL(url) {

downloadAsync(url, function(text) { // still nested

showContents(url, text);

});

}

function showContents(url, text) {

console.log("contents of " + url + ": " + text);

}

This still uses a nested callback inside downloadURL in order to combine the outer url variable with the inner text variable as arguments to showContents. We can eliminate this last nested callback with bind (see Item 25):

db.lookupAsync("url", downloadURL);

function downloadURL(url) {

downloadAsync(url, showContents.bind(null, url));

}

function showContents(url, text) {

console.log("contents of " + url + ": " + text);

}

This approach leads to more sequential-looking code, but at the cost of having to name each intermediate step of the sequence and copy bindings from step to step. This can get awkward in cases like the longer example above:

db.lookupAsync("url", downloadURLAndFiles);

function downloadURLAndFiles(url) {

downloadAsync(url, downloadABC.bind(null, url));

}

// awkward name

function downloadABC(url, file) {

downloadAsync("a.txt",

// duplicated bindings

downloadFiles23.bind(null, url, file));

}

// awkward name

function downloadBC(url, file, a) {

downloadAsync("b.txt",

// more duplicated bindings

downloadFile3.bind(null, url, file, a));

}

// awkward name

function downloadC(url, file, a, b) {

downloadAsync("c.txt",

// still more duplicated bindings

finish.bind(null, url, file, a, b));

}

function finish(url, file, a, b, c) {

// ...

}

Sometimes a combination of the two approaches strikes a better balance, albeit still with some nesting:

db.lookupAsync("url", function(url) {

downloadURLAndFiles(url);

});

function downloadURLAndFiles(url) {

downloadAsync(url, downloadFiles.bind(null, url));

}

function downloadFiles(url, file) {

downloadAsync("a.txt", function(a) {

downloadAsync("b.txt", function(b) {

downloadAsync("c.txt", function(c) {

// ...

});

});

});

}

Even better, this last step can be improved with an additional abstraction for downloading multiple files and storing them in an array:

function downloadFiles(url, file) {

downloadAllAsync(["a.txt", "b.txt", "c.txt"],

function(all) {

var a = all[0], b = all[1], c = all[2];

// ...

});

}

Using downloadAllAsync also allows us to download multiple files concurrently. Sequencing means that each operation cannot even be initiated until the previous one completes. And some operations are inherently sequential, like downloading the URL we fetched from a database lookup. But if we have a list of filenames to download, chances are there’s no reason to wait for each file to finish downloading before requesting the next. Item 66 explains how to implement concurrent abstractions such as downloadAllAsync.

Beyond nesting and naming callbacks, it’s possible to build higher-level abstractions to make asynchronous control flow simpler and more concise. Item 68 describes one particularly popular approach. Beyond that, it’s worth exploring asynchrony libraries or experimenting with abstractions of your own.

Things to Remember

• Use nested or named callbacks to perform several asynchronous operations in sequence.

• Try to strike a balance between excessive nesting of callbacks and awkward naming of non-nested callbacks.

• Avoid sequencing operations that can be performed concurrently.

Item 63: Be Aware of Dropped Errors

One of the more difficult aspects of asynchronous programming to manage is error handling. In synchronous code, it’s easy to handle errors in one fell swoop by wrapping a section of code with a try block:

try {

f();

g();

h();

} catch (e) {

// handle any error that occurred...

}

With asynchronous code, a multistep process is usually divided into separate turns of the event queue, so it’s not possible to wrap them all in a single try block. In fact, asynchronous APIs cannot even throw exceptions at all, because by the time an asynchronous error occurs, there is no obvious execution context to throw the exception to! Instead, asynchronous APIs tend to represent errors as special arguments to callbacks, or take additional error-handling callbacks (sometimes referred to as errbacks). For example, an asynchronous API for downloading a file like the one from Item 61 might take an extra function to be called in case of a network error:

downloadAsync("http://example.com/file.txt", function(text) {

console.log("File contents: " + text);

}, function(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

});

To download several files, you can nest the callbacks as explained in Item 62:

downloadAsync("a.txt", function(a) {

downloadAsync("b.txt", function(b) {

downloadAsync("c.txt", function(c) {

console.log("Contents: " + a + b + c);

}, function(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

});

}, function(error) { // repeated error-handling logic

console.log("Error: " + error);

});

}, function(error) { // repeated error-handling logic

console.log("Error: " + error);

});

Notice how in this example, each step of the process uses the same error-handling logic, but we’ve repeated the same code in several places. As always in programming, we should strive to avoid duplicating code. It’s easy enough to abstract this out by defining an error-handling function in a shared scope:

function onError(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

}

downloadAsync("a.txt", function(a) {

downloadAsync("b.txt", function(b) {

downloadAsync("c.txt", function(c) {

console.log("Contents: " + a + b + c);

}, onError);

}, onError);

}, onError);

Of course, if we combine multiple steps into a single compound operation with utilities such as downloadAllAsync (as Items 62 and 66 recommend), we naturally end up only needing to provide a single error callback:

downloadAllAsync(["a.txt", "b.txt", "c.txt"], function(abc) {

console.log("Contents: " + abc[0] + abc[1] + abc[2]);

}, function(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

});

Another style of error-handling API, popularized by the Node.js platform, takes only a single callback whose first argument is either an error, if one occurred, or a falsy value such as null otherwise. For these kinds of APIs, we can still define a common error-handling function, but we need to guard each callback with an if statement:

function onError(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

}

downloadAsync("a.txt", function(error, a) {

if (error) {

onError(error);

return;

}

downloadAsync("b.txt", function(error, b) {

// duplicated error-checking logic

if (error) {

onError(error);

return;

}

downloadAsync(url3, function(error, c) {

// duplicated error-checking logic

if (error) {

onError(error);

return;

}

console.log("Contents: " + a + b + c);

});

});

});

In frameworks with this style of error callback, programmers often abandon conventions requiring if statements to span multiple lines with braced bodies, leading to more concise, less distracting error handling:

function onError(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

}

downloadAsync("a.txt", function(error, a) {

if (error) return onError(error);

downloadAsync("b.txt", function(error, b) {

if (error) return onError(error);

downloadAsync(url3, function(error, c) {

if (error) return onError(error);

console.log("Contents: " + a + b + c);

});

});

});

Or, as always, combining steps with an abstraction helps eliminate duplication:

var filenames = ["a.txt", "b.txt", "c.txt"];

downloadAllAsync(filenames, function(error, abc) {

if (error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

return;

}

console.log("Contents: " + abc[0] + abc[1] + abc[2]);

});

One of the practical differences between try...catch and typical error-handling logic in asynchronous APIs is that try makes it easier to define “catchall” logic so that it’s difficult to forget to handle errors in an entire region of code. With asynchronous APIs like the one above, it’s very easy to forget to provide error handling in any of the steps of the process. Often, this results in an error getting silently dropped. A program that ignores errors can be very frustrating for users: The application provides no feedback that something went wrong (sometimes resulting in a hanging progress notification that never clears). Similarly, silent errors are a nightmare to debug, since they provide no clues about the source of the problem. The best cure is prevention: Working with asynchronous APIs requires vigilance to make sure you handle all error conditions explicitly.

Things to Remember

• Avoid copying and pasting error-handling code by writing shared error-handling functions.

• Make sure to handle all error conditions explicitly to avoid dropped errors.

Item 64: Use Recursion for Asynchronous Loops

Consider a function that takes an array of URLs and tries to download one at a time until one succeeds. If the API were synchronous, it would be easy to implement with a loop:

function downloadOneSync(urls) {

for (var i = 0, n = urls.length; i < n; i++) {

try {

return downloadSync(urls[i]);

} catch (e) { }

}

throw new Error("all downloads failed");

}

But this approach won’t work for downloadOneAsync, because we can’t suspend a loop and resume it in a callback. If we tried using a loop, it would initiate all of the downloads rather than waiting for one to continue before trying the next:

function downloadOneAsync(urls, onsuccess, onerror) {

for (var i = 0, n = urls.length; i < n; i++) {

downloadAsync(urls[i], onsuccess, function(error) {

// ?

});

// loop continues

}

throw new Error("all downloads failed");

}

So we need to implement something that acts like a loop, but that doesn’t continue executing until we explicitly say so. The solution is to implement the loop as a function, so we can decide when to start each iteration:

function downloadOneAsync(urls, onsuccess, onfailure) {

var n = urls.length;

function tryNextURL(i) {

if (i >= n) {

onfailure("all downloads failed");

return;

}

downloadAsync(urls[i], onsuccess, function() {

tryNextURL(i + 1);

});

}

tryNextURL(0);

}

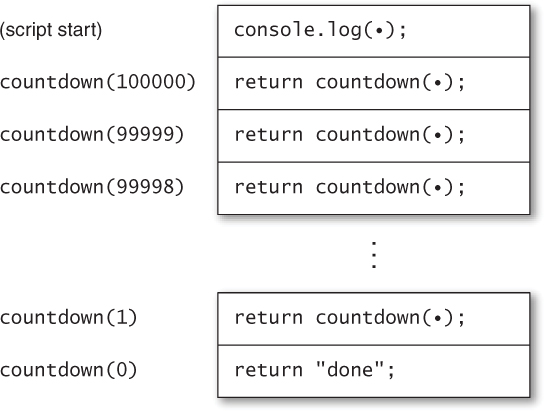

The local tryNextURL function is recursive: Its implementation involves a call to itself. Now, in typical JavaScript environments, a recursive function that calls itself synchronously can fail after too many calls to itself. For example, this simple recursive function tries to call itself 100,000 times, but in most JavaScript environments it fails with a runtime error:

function countdown(n) {

if (n === 0) {

return "done";

} else {

return countdown(n – 1);

}

}

countdown(100000); // error: maximum call stack size exceeded

So how could the recursive downloadOneAsync be safe if countdown explodes when n is too large? To answer this, let’s take a small detour and unpack the error message provided by countdown.

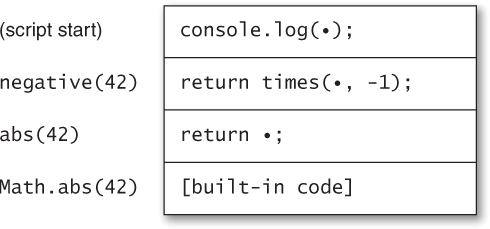

JavaScript environments usually reserve a fixed amount of space in memory, known as the call stack, to keep track of what to do next after returning from function calls. Imagine executing this little program:

function negative(x) {

return abs(x) * -1;

}

function abs(x) {

return Math.abs(x);

}

console.log(negative(42));

At the point in the application where Math.abs is called with the argument 42, there are several other function calls in progress, each waiting for another to return. Figure 7.2 illustrates the call stack at this point. At the point of each function call, the bullet symbol (•) depicts the place in the program where a function call has occurred and where that call will return to when it finishes. Like the traditional stack data structure, this information follows a “last-in, first-out” protocol: The most recent function call that pushes information onto the stack (represented as the bottommost frame of the stack) will be the first to pop back off the stack. When Math.abs finishes, it returns to the abs function, which returns to the negative function, which in turn returns to the outermost script.

Figure 7.2. A call stack during the execution of a simple program

When a program is in the middle of too many function calls, it can run out of stack space, resulting in a thrown exception. This condition is known as stack overflow. In our example, calling countdown(100000) requires countdown to call itself 100,000 times, each time pushing another stack frame, as shown in Figure 7.3. The amount of space required to store so many stack frames exhausts the space allocated by most JavaScript environments, leading to a runtime error.

Figure 7.3. A call stack during the execution of a recursive function

Now take another look at downloadOneAsync. Unlike countdown, which can’t return until the recursive call returns, downloadOneAsync only calls itself from within an asynchronous callback. Remember that asynchronous APIs return immediately—before their callbacks are invoked. So downloadOneAsync returns, causing its stack frame to be popped off of the call stack, before any recursive call causes a new stack frame to be pushed back on the stack. (In fact, the callback is always invoked in a separate turn of the event loop, and each turn of the event loop invokes its event handler with the call stack initially empty.) So downloadOneAsync never starts eating up call stack space, no matter how many iterations it requires.

Things to Remember

• Loops cannot be asynchronous.

• Use recursive functions to perform iterations in separate turns of the event loop.

• Recursion performed in separate turns of the event loop does not overflow the call stack.

Item 65: Don’t Block the Event Queue on Computation

Item 61 explains how asynchronous APIs help to prevent a program from clogging up an application’s event queue. But this is not the whole story. After all, as every programmer can tell you, it’s easy enough to stall an application without even a single function call:

while (true) { }

And it doesn’t take an infinite loop to write a sluggish program. Code takes time to run, and inefficient algorithms or data structures can lead to long-running computations.

Of course, efficiency is not a concern that’s unique to JavaScript. But event-based programming does impose particular constraints. In order to preserve a high degree of interactivity in a client application, or to ensure that all incoming requests get adequately serviced in a server application, it’s critical to keep each turn of the event loop as short as possible. Otherwise, the event queue can start getting backed up, growing at a faster rate than event handlers can be dispatched to shrink it again. In the browser setting, expensive computations also lead to a bad user experience, since a page’s user interface is mostly unresponsive while JavaScript code is running.

So what can you do if your application needs to perform expensive computations? There’s no one right answer, but there are a few common techniques available. Perhaps the simplest approach is to use a concurrency mechanism like the web client platform’s Worker API. This can be a good approach for games with artificial intelligence that may need to search through a large space of possible moves. The game might start up by spawning a dedicated worker for computing moves:

var ai = new Worker("ai.js");

This has the effect of spawning a new concurrent thread of execution with its own separate event queue, using the source file ai.js as the worker’s script. The worker runs in a completely isolated state: It has no direct access to any of the objects of the application. However, the application and worker can communicate with each other by sending messages to each other, in the form of strings. So whenever the game requires the computer to make a move, it can send a message to the worker:

var userMove = /* ... */;

ai.postMessage(JSON.stringify({

userMove: userMove

}));

The argument to postMessage is added to the worker’s event queue as a message. To process responses from the worker, the game registers an event handler:

ai.onmessage = function(event) {

executeMove(JSON.parse(event.data).computerMove);

};

Meanwhile, the source file ai.js instructs the worker to listen for messages and perform the work required to compute next moves:

self.onmessage = function(event) {

// parse the user move

var userMove = JSON.parse(event.data).userMove;

// generate the next computer move

var computerMove = computeNextMove(userMove);

// format the computer move

var message = JSON.stringify({

computerMove: computerMove

});

self.postMessage(message);

};

function computeNextMove(userMove) {

// ...

}

Not all JavaScript platforms provide an API like Worker. And sometimes the overhead of passing messages can become too costly. A different approach is to break up an algorithm into multiple steps, each consisting of a manageable chunk of work. Consider the work-list algorithm from Item 48 for searching a social network graph:

Member.prototype.inNetwork = function(other) {

var visited = {};

var worklist = [this];

while (worklist.length > 0) {

var member = worklist.pop();

// ...

if (member === other) { // found?

return true;

}

// ...

}

return false;

};

If the while loop at the heart of this procedure is too expensive, the search might block the application event queue for unacceptably long periods of time. Even if the Worker API is available, it might be expensive or inconvenient to implement, since it requires either copying the entire state of the network graph or storing the graph state in a worker and always using message passing to update and query the network.

Luckily, the algorithm is defined as a sequence of individual steps: the iterations of the while loop. We can convert inNetwork to an asynchronous function by adding a callback parameter and, as described in Item 64, replacing the while loop with an asynchronous, recursive function:

Member.prototype.inNetwork = function(other, callback) {

var visited = {};

var worklist = [this];

function next() {

if (worklist.length === 0) {

callback(false);

return;

}

var member = worklist.pop();

// ...

if (member === other) { // found?

callback(true);

return;

}

// ...

setTimeout(next, 0); // schedule the next iteration

}

setTimeout(next, 0); // schedule the first iteration

};

Let’s examine in detail how this code works. In place of the while loop, we’ve written a local function called next, which has the responsibility of performing a single iteration of the loop and then scheduling the next iteration to run asynchronously in the application event queue. This allows other events that have occurred in the meantime to be processed before continuing with the next iteration. When the search is complete, by either finding a match or exhausting the work-list, we call the callback with the result value and effectively complete the loop by returning from next without scheduling anymore iterations.

To schedule iterations, we are using the common setTimeout API, available in multiple JavaScript platforms, for registering next to run after a minimal amount of elapsed time (0 milliseconds). This has the effect of adding the callback to the event queue almost right away. It’s worth noting that while setTimeout is relatively portable across platforms, there’s often a better alternative available. In the browser setting, for example, it’s actually throttled to a minimum timeout of 4 milliseconds, and there are alternatives using postMessage that enqueue an event immediately.

If performing only one iteration of the algorithm in each turn of the application event queue is overkill, we can tune the algorithm to perform a customized number of iterations per turn. This is easily accomplished with a simple counter loop surrounding the main portion of next:

Member.prototype.inNetwork = function(other, callback) {

// ...

function next() {

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

// ...

}

setTimeout(next, 0);

}

setTimeout(next, 0);

};

Things to Remember

• Avoid expensive algorithms in the main event queue.

• On platforms that support it, the Worker API can be used for running long computations in a separate event queue.

• When the Worker API is not available or is too costly, consider breaking up computations across multiple turns of the event loop.

Item 66: Use a Counter to Perform Concurrent Operations

Item 63 suggested the utility function downloadAllAsync to take an array of URLs and download them all, returning the array of file contents, one string per URL. Besides cleaning up nested callbacks, downloadAllAsync’s primary benefit is downloading files concurrently: Instead of waiting for each file to finish downloading, we can initiate all the downloads at once, in a single turn of the event loop.

Concurrent logic is subtle and easy to get wrong. Here is an implementation with a devious little flaw:

function downloadAllAsync(urls, onsuccess, onerror) {

var result = [], length = urls.length;

if (length === 0) {

setTimeout(onsuccess.bind(null, result), 0);

return;

}

urls.forEach(function(url) {

downloadAsync(url, function(text) {

if (result) {

// race condition

result.push(text);

if (result.length === urls.length) {

onsuccess(result);

}

}

}, function(error) {

if (result) {

result = null;

onerror(error);

}

});

});

}

This function has a serious bug, but first let’s look at how it works. We start by ensuring that if the input array is empty, the callback is invoked with an empty result array—if we didn’t, neither of the two callbacks would ever be invoked, since the forEach loop would be empty. (Item 67 explains why we call setTimeout to invoke the onsuccess callback instead of calling it directly.) Next, we iterate over the URL array, requesting an asynchronous download for each. For each successful download, we add the file contents to the result array; if all URLs have been successfully downloaded, we call the onsuccess callback with the completed result array. If any download fails, we invoke the onerror callback with the error value. In case of multiple failed downloads, we also set the result array to null to make sure that onerror is only called once, for the first error that occurs.

To see what goes wrong, consider a use such as this:

var filenames = [

"huge.txt", // huge file

"tiny.txt", // tiny file

"medium.txt" // medium-sized file

];

downloadAllAsync(filenames, function(files) {

console.log("Huge file: " + files[0].length); // tiny

console.log("Tiny file: " + files[1].length); // medium

console.log("Medium file: " + files[2].length); // huge

}, function(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

});

Since the files are downloaded concurrently, the events can occur (and consequently be added to the application event queue) in arbitrary orders. If, for example, tiny.txt completes first, followed by medium.txt and then huge.txt, the callbacks installed in downloadAllAsync will be called in a different order than the order they were created in. But the implementation of downloadAllAsync pushes each intermediate result onto the end of the result array as soon as it arrives. So downloadAllAsync produces an array containing downloaded files stored in an unknown order. It’s almost impossible to use an API like that correctly, because the caller has no way to figure out which result is which. The example above, which assumes the results are in the same order as the input array, will fail completely in this case.

Item 48 introduced the idea of nondeterminism: unspecified behavior that programs cannot rely on without behaving unpredictably. Concurrent events are the most important source of nondeterminism in JavaScript. Specifically, the order in which events occur is not guaranteed to be the same from one execution of an application to the next.

When an application depends on the particular order of events to function correctly, the application is said to suffer from a data race: Multiple concurrent actions can modify a shared data structure differently depending on the order in which they occur. (Intuitively, the concurrent operations are “racing” against one another to see who will finish first.) Data races are truly sadistic bugs: They may not even show up in a particular test run, since running the same program twice may result in different behavior each time. For example, the user of downloadAllAsync might try to reorder the files based on which was more likely to download first:

downloadAllAsync(filenames, function(files) {

console.log("Huge file: " + files[2].length);

console.log("Tiny file: " + files[0].length);

console.log("Medium file: " + files[1].length);

}, function(error) {

console.log("Error: " + error);

});

In this case, the results might arrive in the same order most of the time, but from time to time, due perhaps to changing server loads or network caches, the files might not arrive in the expected order. These tend to be the most challenging bugs to diagnose, because they’re so difficult to reproduce. Of course, we could go back to downloading the files sequentially, but then we lose the performance benefits of concurrency.

The solution is to implement downloadAllAsync so that it always produces predictable results regardless of the unpredictable order of events. Instead of pushing each result onto the end of the array, we store it at its original index:

function downloadAllAsync(urls, onsuccess, onerror) {

var length = urls.length;

var result = [];

if (length === 0) {

setTimeout(onsuccess.bind(null, result), 0);

return;

}

urls.forEach(function(url, i) {

downloadAsync(url, function(text) {

if (result) {

result[i] = text; // store at fixed index

// race condition

if (result.length === urls.length) {

onsuccess(result);

}

}

}, function(error) {

if (result) {

result = null;

onerror(error);

}

});

});

}

This implementation takes advantage of the forEach callback’s second argument, which provides the array index for the current iteration. Unfortunately, it’s still not correct. Item 51 describes the contract of array updates: Setting an indexed property always ensures that the array’s length property is greater than that index. Imagine a request such as:

downloadAllAsync(["huge.txt", "medium.txt", "tiny.txt"]);

If the file tiny.txt finishes loading before one of the other files, the result array will acquire a property at index 2, which causes result.length to be updated to 3. The user’s success callback will then be prematurely called with an incomplete array of results.

The correct implementation uses a counter to track the number of pending operations:

function downloadAllAsync(urls, onsuccess, onerror) {

var pending = urls.length;

var result = [];

if (pending === 0) {

setTimeout(onsuccess.bind(null, result), 0);

return;

}

urls.forEach(function(url, i) {

downloadAsync(url, function(text) {

if (result) {

result[i] = text; // store at fixed index

pending--; // register the success

if (pending === 0) {

onsuccess(result);

}

}

}, function(error) {

if (result) {

result = null;

onerror(error);

}

});

});

}

Now no matter what order the events occur in, the pending counter accurately indicates when all events have completed, and the complete results are returned in the proper order.

Things to Remember

• Events in a JavaScript application occur nondeterministically, that is, in unpredictable order.

• Use a counter to avoid data races in concurrent operations.

Item 67: Never Call Asynchronous Callbacks Synchronously

Imagine a variation of downloadAsync that keeps a cache (implemented as a Dict—see Item 45) to avoid downloading the same file multiple times. In the cases where the file is already cached, it’s tempting to invoke the callback immediately:

var cache = new Dict();

function downloadCachingAsync(url, onsuccess, onerror) {

if (cache.has(url)) {

onsuccess(cache.get(url)); // synchronous call

return;

}

return downloadAsync(url, function(file) {

cache.set(url, file);

onsuccess(file);

}, onerror);

}

As natural as it may seem to provide data immediately if it’s available, this violates the expectations of an asynchronous API’s clients in subtle ways. First of all, it changes the expected order of operations. Item 62 showed the following example, which for a well-behaved asynchronous API should always log messages in a predictable order:

downloadAsync("file.txt", function(file) {

console.log("finished");

});

console.log("starting");

With the naïve implementation of downloadCachingAsync above, such client code could end up logging the events in either order, depending on whether the file has been cached:

downloadCachingAsync("file.txt", function(file) {

console.log("finished"); // might happen first

});

console.log("starting");

The order of logging messages is one thing. More generally, the purpose of asynchronous APIs is to maintain the strict separation of turns of the event loop. As Item 61 explains, this simplifies concurrency by alleviating code in one turn of the event loop from having to worry about other code changing shared data structures concurrently. An asynchronous callback that gets called synchronously violates this separation, causing code intended for a separate turn of the event loop to execute before the current turn completes.

For example, an application might keep a queue of files remaining to download and display a message to the user:

downloadCachingAsync(remaining[0], function(file) {

remaining.shift();

// ...

});

status.display("Downloading " + remaining[0] + "...");

If the callback is invoked synchronously, the display message will show the wrong filename (or worse, "undefined" if the queue is empty).

Invoking an asynchronous callback can cause even subtler problems. Item 64 explains that asynchronous callbacks are intended to be invoked with an essentially empty call stack, so it’s safe to implement asynchronous loops as recursive functions without any danger of accumulating unbounded call stack space. A synchronous call negates this guarantee, making it possible for an ostensibly asynchronous loop to exhaust the call stack space. Yet another issue is exceptions: With the above implementation of downloadCachingAsync, if the callback throws an exception, it will be thrown in the turn of the event loop that initiated the download, rather than in a separate turn as expected.

To ensure that the callback is always invoked asynchronously, we can use an existing asynchronous API. Just as we did in Items 65 and 66, we use the common library function setTimeout to add a callback to the event queue after a minimum timeout. There may be preferable alternatives to setTimeout for scheduling immediate events, depending on the platform.

var cache = new Dict();

function downloadCachingAsync(url, onsuccess, onerror) {

if (cache.has(url)) {

var cached = cache.get(url);

setTimeout(onsuccess.bind(null, cached), 0);

return;

}

return downloadAsync(url, function(file) {

cache.set(url, file);

onsuccess(file);

}, onerror);

}

We use bind (see Item 25) to save the result as the first argument for the onsuccess callback.

Things to Remember

• Never call an asynchronous callback synchronously, even if the data is immediately available.

• Calling an asynchronous callback synchronously disrupts the expected sequence of operations and can lead to unexpected interleaving of code.

• Calling an asynchronous callback synchronously can lead to stack overflows or mishandled exceptions.

• Use an asynchronous API such as setTimeout to schedule an asynchronous callback to run in another turn.

Item 68: Use Promises for Cleaner Asynchronous Logic

A popular alternative way to structure asynchronous APIs is to use promises (sometimes known as deferreds or futures). The asynchronous APIs we’ve discussed in this chapter take callbacks as arguments:

downloadAsync("file.txt", function(file) {

console.log("file: " + file);

});

By contrast, a promise-based API does not take callbacks as arguments; instead, it returns a promise object, which itself accepts callbacks via its then method:

var p = downloadP("file.txt");

p.then(function(file) {

console.log("file: " + file);

});

So far this hardly looks any different from the original version. But the power of promises is in their composability. The callback passed to then can be used not only to cause effects (in the above example, to print out to the console), but also to produce results. By returning a value from the callback, we can construct a new promise:

var fileP = downloadP("file.txt");

var lengthP = fileP.then(function(file) {

return file.length;

});

lengthP.then(function(length) {

console.log("length: " + length);

});

One way to think about a promise is as an object that represents an eventual value—it wraps a concurrent operation that may not have completed yet, but will eventually produce a result value. The then method allows us to take one promise object that represents one type of eventual value and generate a new promise object that represents another type of eventual value—whatever we return from the callback.

This ability to construct new promises from existing promises gives them great flexibility, and enables some simple but very powerful idioms. For example, it’s relatively easy to construct a utility for “joining” the results of multiple promises:

var filesP = join(downloadP("file1.txt"),

downloadP("file2.txt"),

downloadP("file3.txt"));

filesP.then(function(files) {

console.log("file1: " + files[0]);

console.log("file2: " + files[1]);

console.log("file3: " + files[2]);

});

Promise libraries also often provide a utility function called when, which can be used similarly:

var fileP1 = downloadP("file1.txt"),

fileP2 = downloadP("file2.txt"),

fileP3 = downloadP("file3.txt");

when([fileP1, fileP2, fileP3], function(files) {

console.log("file1: " + files[0]);

console.log("file2: " + files[1]);

console.log("file3: " + files[2]);

});

Part of what makes promises an excellent level of abstraction is that they communicate their results by returning values from their then methods, or by composing promises via utilities such as join, rather than by writing to shared data structures via concurrent callbacks. This is inherently safer because it avoids the data races discussed in Item 66. Even the most conscientious programmer can make simple mistakes when saving the results of asynchronous operations in shared variables or data structures:

var file1, file2;

downloadAsync("file1.txt", function(file) {

file1 = file;

});

downloadAsync("file2.txt", function(file) {

file1 = file; // wrong variable

});

Promises avoid this kind of bug because the style of concisely composing promises avoids modifying shared data.

Notice also that sequential chains of asynchronous logic actually appear sequential with promises, rather than with the unwieldy nesting patterns demonstrated in Item 62. What’s more, error handling is automatically propagated through promises. When you chain a collection of asynchronous operations together through promises, you can provide a single error callback for the entire sequence, rather than passing an error callback to every step as in the code in Item 63.

Despite this, it is sometimes useful to create certain kinds of races purposefully, and promises provide an elegant mechanism for doing this. For example, an application may need to try downloading the same file simultaneously from several different servers and take whichever one completes first. The select (or choose) utility takes several promises and produces a promise whose value is whichever result becomes available first. In other words, it “races” several promises against one another.

var fileP = select(downloadP("http://example1.com/file.txt"),

downloadP("http://example2.com/file.txt"),

downloadP("http://example3.com/file.txt"));

fileP.then(function(file) {

console.log("file: " + file);

});

Another use of select is to provide timeouts to abort operations that take too long:

var fileP = select(downloadP("file.txt"), timeoutErrorP(2000));

fileP.then(function(file) {

console.log("file: " + file);

}, function(error) {

console.log("I/O error or timeout: " + error);

});

In that last example, we’re demonstrating the mechanism for providing error callbacks to a promise as the second argument to then.

Things to Remember

• Promises represent eventual values, that is, concurrent computations that eventually produce a result.

• Use promises to compose different concurrent operations.

• Use promise APIs to avoid data races.

• Use select (also known as choose) for situations where an intentional race condition is required.