4. Objects and Prototypes

Objects are JavaScript’s fundamental data structure. Intuitively, an object represents a table relating strings to values. But when you dig deeper, there is a fair amount of machinery that goes into objects.

Like many object-oriented languages, JavaScript provides support for implementation inheritance: the reuse of code or data through a dynamic delegation mechanism. But unlike many conventional languages, JavaScript’s inheritance mechanism is based on prototypes rather than classes. For many programmers, JavaScript is the first object-oriented language they encounter without classes.

In many languages, every object is an instance of an associated class, which provides code shared between all its instances. JavaScript, by contrast, has no built-in notion of classes. Instead, objects inherit from other objects. Every object is associated with some other object, known as its prototype. Working with prototypes can be different from classes, although many concepts from traditional object-oriented languages still carry over.

Item 30: Understand the Difference between prototype, getPrototypeOf, and __proto__

Prototypes involve three separate but related accessors, all of which are named with some variation on the word prototype. This unfortunate overlap naturally leads to quite a bit of confusion. Let’s get straight to the point.

• C.prototype is used to establish the prototype of objects created by new C().

• Object.getPrototypeOf(obj) is the standard ES5 mechanism for retrieving obj’s prototype object.

• obj.__proto__ is a nonstandard mechanism for retrieving obj’s prototype object.

To understand each of these, consider a typical definition of a JavaScript datatype. The User constructor expects to be called with the new operator and takes a name and the hash of a password string and stores them on its created object.

function User(name, passwordHash) {

this.name = name;

this.passwordHash = passwordHash;

}

User.prototype.toString = function() {

return "[User " + this.name + "]";

};

User.prototype.checkPassword = function(password) {

return hash(password) === this.passwordHash;

};

var u = new User("sfalken",

"0ef33ae791068ec64b502d6cb0191387");

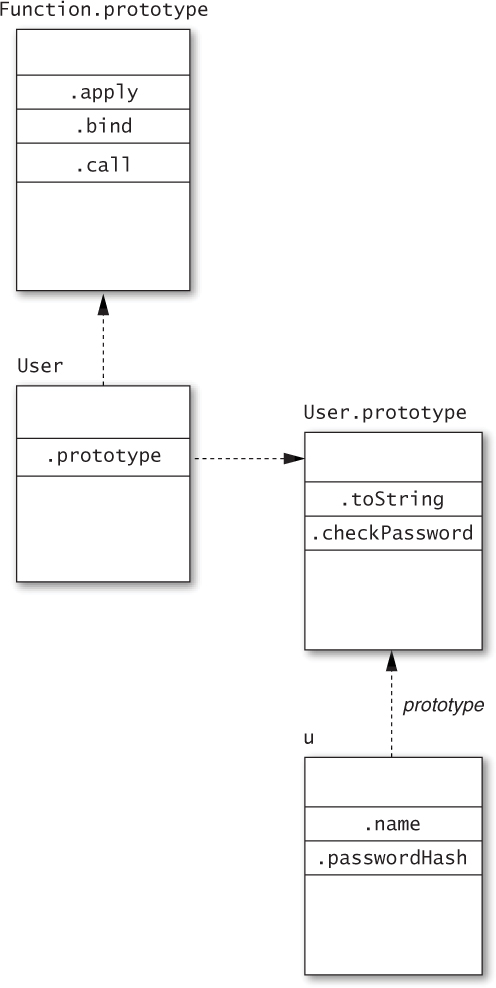

The User function comes with a default prototype property, containing an object that starts out more or less empty. In this example, we add two methods to the User.prototype object: toString and checkPassword. When we create an instance of User with the new operator, the resultant object u gets the object stored at User.prototype automatically assigned as its prototype object. Figure 4.1 shows a diagram of these objects.

Figure 4.1. Prototype relationships for the User constructor and instance

Notice the arrow linking the instance object u to the prototype object User.prototype. This link describes the inheritance relationship. Property lookups start by searching the object’s own properties; for example, u.name and u.passwordHash return the current values of immediate properties of u. Properties not found directly on u are looked up in u’s prototype. Accessing u.checkPassword, for example, retrieves a method stored in User.prototype.

This leads us to the next item in our list. Whereas the prototype property of a constructor function is used to set up the prototype relationship of new instances, the ES5 function Object.getPrototypeOf() can be used to retrieve the prototype of an existing object. So, for example, after we create the object u in the example above, we can test:

Object.getPrototypeOf(u) === User.prototype; // true

Some environments produce a nonstandard mechanism for retrieving the prototype of an object via a special __proto__ property. This can be useful as a stopgap for environments that do not support ES5’s Object.getPrototypeOf. In such environments, we can similarly test:

u.__proto__ === User.prototype; // true

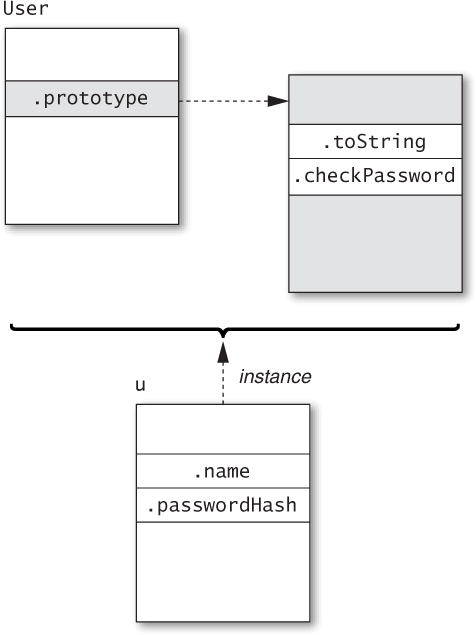

A final note about prototype relationships: JavaScript programmers will often describe User as a class, even though it consists of little more than a function. Classes in JavaScript are essentially the combination of a constructor function (User) and a prototype object used to share methods between instances of the class (User.prototype).

Figure 4.2 provides a good way to think about the User class conceptually. The User function provides a public constructor for the class, and User.prototype is an internal implementation of the methods shared between instances. Ordinary uses of User and u have no need to access the prototype object directly.

Figure 4.2. Conceptual view of the User “class”

Things to Remember

• C.prototype determines the prototype of objects created by new C().

• Object.getPrototypeOf(obj) is the standard ES5 function for retrieving the prototype of an object.

• obj.__proto__ is a nonstandard mechanism for retrieving the prototype of an object.

• A class is a design pattern consisting of a constructor function and an associated prototype.

Item 31: Prefer Object.getPrototypeOf to __proto__

ES5 introduced Object.getPrototypeOf as the standard API for retrieving an object’s prototype, but only after a number of JavaScript engines had long provided the special __proto__ property for the same purpose. Not all JavaScript environments support this extension, however, and those that do are not entirely compatible. Environments differ, for example, on the treatment of objects with a null prototype. In some environments, __proto__ is inherited from Object.prototype, so an object with a null prototype has no special __proto__ property:

var empty = Object.create(null); // object with no prototype

"__proto__" in empty; // false (in some environments)

In others, __proto__ is always handled specially, regardless of an object’s state:

var empty = Object.create(null); // object with no prototype

"__proto__" in empty; // true (in some environments)

Wherever Object.getPrototypeOf is available, it is the more standard and portable approach to extracting prototypes. Moreover, the __proto__ property leads to a number of bugs due to its pollution of all objects (see Item 45). JavaScript engines that currently support the extension may choose in the future to allow programs to disable it in order to avoid these bugs. Preferring Object.getPrototypeOf ensures that code will continue to work even if __proto__ is disabled.

For JavaScript environments that do not provide the ES5 API, it is easy to implement in terms of __proto__:

if (typeof Object.getPrototypeOf === "undefined") {

Object.getPrototypeOf = function(obj) {

var t = typeof obj;

if (!obj || (t !== "object" && t !== "function")) {

throw new TypeError("not an object");

}

return obj.__proto__;

};

}

This implementation is safe to include in ES5 environments, because it avoids installing the function if Object.getPrototypeOf already exists.

Things to Remember

• Prefer the standards-compliant Object.getPrototypeOf to the nonstandard __proto__ property.

• Implement Object.getPrototypeOf in non-ES5 environments that support __proto__.

Item 32: Never Modify __proto__

The special __proto__ property provides an additional power that Object.getPrototypeOf does not: the ability to modify an object’s prototype link. While this power may seem innocuous (after all, it’s just another property, right?), it actually has serious implications and should be avoided. The most obvious reason to avoid modifying __proto__ is portability: Since not all platforms support the ability to change an object’s prototype you simply can’t write portable code that does it.

Another reason to avoid modifying __proto__ is performance. All modern JavaScript engines heavily optimize the act of getting and setting object properties, since these are some of the most common operations that JavaScript programs perform. These optimizations are built on the engine’s knowledge of the structure of an object. When you change the object’s internal structure, say, by adding or removing properties to the object or an object in its prototype chain, some of these optimizations are invalidated. Modifying __proto__ actually changes the inheritance structure itself, which is the most destructive change possible. This can invalidate many more optimizations than modifications to ordinary properties.

But the biggest reason to avoid modifying __proto__ is for maintaining predictable behavior. An object’s prototype chain defines its behavior by determining its set of properties and property values. Modifying an object’s prototype link is like giving it a brain transplant: It swaps the object’s entire inheritance hierarchy. It may be possible to imagine exceptional situations where such an operation could be helpful, but as a matter of basic sanity, an inheritance hierarchy should remain stable.

For creating new objects with a custom prototype link, you can use ES5’s Object.create. For environments that do not implement ES5, Item 33 provides a portable implementation of Object.create that does not rely on __proto__.

Things to Remember

• Never modify an object’s __proto__ property.

• Use Object.create to provide a custom prototype for new objects.

Item 33: Make Your Constructors new-Agnostic

When you create a constructor such as the User function in Item 30, you rely on callers to remember to call it with the new operator. Notice how the function assumes that the receiver is a brand-new object:

function User(name, passwordHash) {

this.name = name;

this.passwordHash = passwordHash;

}

If a caller forgets the new keyword, then the function’s receiver becomes the global object:

var u = User("baravelli", "d8b74df393528d51cd19980ae0aa028e");

u; // undefined

this.name; // "baravelli"

this.passwordHash; // "d8b74df393528d51cd19980ae0aa028e"

Not only does the function uselessly return undefined, it also disastrously creates (or modifies, if they happen to exist already) the global variables name and passwordHash.

If the User function is defined as ES5 strict code, then the receiver defaults to undefined:

function User(name, passwordHash) {

"use strict";

this.name = name;

this.passwordHash = passwordHash;

}

var u = User("baravelli", "d8b74df393528d51cd19980ae0aa028e");

// error: this is undefined

In this case, the faulty call leads to an immediate error: The first line of User attempts to assign to this.name, which throws a TypeError. So, at least with a strict constructor function, the caller can quickly discover the bug and fix it.

Still, in either case, the User function is fragile. When used with new it works as expected, but when used as a normal function it fails. A more robust approach is to provide a function that works as a constructor no matter how it’s called. An easy way to implement this is to check that the receiver value is a proper instance of User:

function User(name, passwordHash) {

if (!(this instanceof User)) {

return new User(name, passwordHash);

}

this.name = name;

this.passwordHash = passwordHash;

}

This way, the result of calling User is an object that inherits from User.prototype, regardless of whether it’s called as a function or as a constructor:

var x = User("baravelli", "d8b74df393528d51cd19980ae0aa028e");

var y = new User("baravelli",

"d8b74df393528d51cd19980ae0aa028e");

x instanceof User; // true

y instanceof User; // true

One downside to this pattern is that it requires an extra function call, so it is a bit more expensive. It’s also hard to use for variadic functions (see Items 21 and 22), since there is no straightforward analog to the apply method for calling variadic functions as constructors. A somewhat more exotic approach makes use of ES5’s Object.create:

function User(name, passwordHash) {

var self = this instanceof User

? this

: Object.create(User.prototype);

self.name = name;

self.passwordHash = passwordHash;

return self;

}

Object.create takes a prototype object and returns a new object that inherits from it. So when this version of User is called as a function, the result is a new object inheriting from User.prototype, with the name and passwordHash properties initialized.

While Object.create is only available in ES5, it can be approximated in older environments by creating a local constructor and instantiating it with new:

if (typeof Object.create === "undefined") {

Object.create = function(prototype) {

function C() { }

C.prototype = prototype;

return new C();

};

}

(Note that this only implements the single-argument version of Object.create. The real version also accepts an optional second argument that describes a set of property descriptors to define on the new object.)

What happens if someone calls this new version of User with new? Thanks to the constructor override pattern, it behaves just like it does with a function call. This works because JavaScript allows the result of a new expression to be overridden by an explicit return from a constructor function. When User returns self, the result of the new expression becomes self, which may be a different object from the one bound to this.

Protecting a constructor against misuse may not always be worth the trouble, especially when you are only using a constructor locally. Still, it’s important to understand how badly things can go wrong if a constructor is called in the wrong way. At the very least, it’s important to document when a constructor function expects to be called with new, especially when sharing it across a large codebase or from a shared library.

Things to Remember

• Make a constructor agnostic to its caller’s syntax by reinvoking itself with new or with Object.create.

• Document clearly when a function expects to be called with new.

Item 34: Store Methods on Prototypes

It’s perfectly possible to program in JavaScript without prototypes. We could implement the User class from Item 30 without defining anything special in its prototype:

function User(name, passwordHash) {

this.name = name;

this.passwordHash = passwordHash;

this.toString = function() {

return "[User " + this.name + "]";

};

this.checkPassword = function(password) {

return hash(password) === this.passwordHash;

};

}

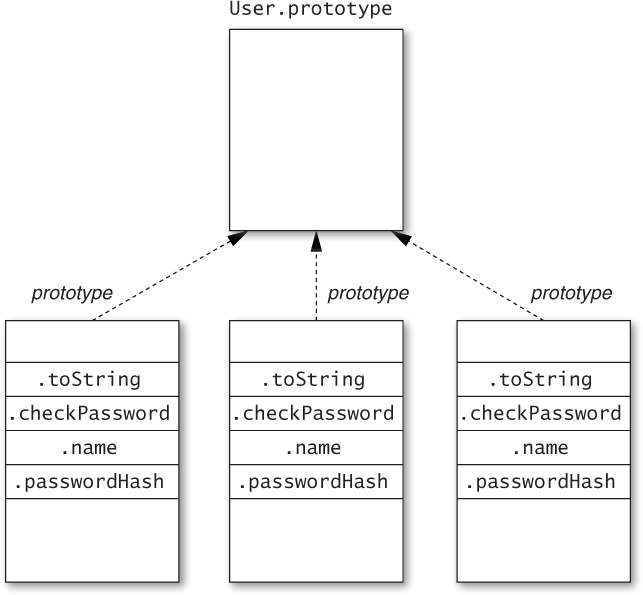

For most purposes, this class behaves pretty much the same as its original implementation. But when we construct several instances of User, an important difference emerges:

var u1 = new User(/* ... */);

var u2 = new User(/* ... */);

var u3 = new User(/* ... */);

Figure 4.3 shows what these three objects and their prototype object look like. Instead of sharing the toString and checkPassword methods via the prototype, each instance contains a copy of both methods, for a total of six function objects.

Figure 4.3. Storing methods on instance objects

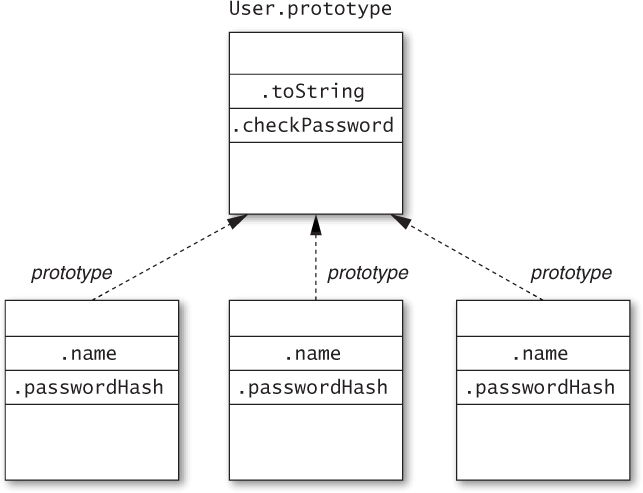

By contrast, Figure 4.4 shows what these three objects and their prototype object look like using the original definition. The toString and checkPassword methods are created once and shared between all instances through their prototype.

Figure 4.4. Storing methods on a prototype object

Storing methods on a prototype makes them available to all instances without requiring multiple copies of the functions that implement them or extra properties on each instance object. You might expect that storing methods on instance objects could optimize the speed of method lookups such as u3.toString(), since it doesn’t have to search the prototype chain to find the implementation of toString. However, modern JavaScript engines heavily optimize prototype lookups, so copying methods onto instance objects is not necessarily guaranteed to provide noticeable speed improvements. And instance methods are almost certain to use more memory than prototype methods.

Things to Remember

• Storing methods on instance objects creates multiple copies of the functions, one per instance object.

• Prefer storing methods on prototypes over storing them on instance objects.

Item 35: Use Closures to Store Private Data

JavaScript’s object system does not particularly encourage or enforce information hiding. The name of every property is a string, and any piece of a program can get access to any of the properties of an object simply by asking for it by name. Features such as for...in loops and ES5’s Object.keys() and Object.getOwnPropertyNames() functions even make it easy to learn all the property names of an object.

Often, JavaScript programmers resort to coding conventions rather than any absolute enforcement mechanism for private properties. For example, some programmers use naming conventions such as prefixing or suffixing private property names with an underscore character (_). This does nothing to enforce information hiding, but it suggests to well-behaved users of an object that they should not inspect or modify the property so that the object can remain free to change its implementation.

Nevertheless, some programs actually call for a higher degree of hiding. For example, a security-sensitive platform or application framework may wish to send an object to an untrusted application without risk of the application tampering with the internals of the object. Another situation where enforcement of information hiding can be useful is in heavily used libraries, where subtle bugs can crop up when careless users accidentally depend on or interfere with implementation details.

For these situations, JavaScript does provide one very reliable mechanism for information hiding: the closure.

Closures are an austere data structure. They store data in their enclosed variables without providing direct access to those variables. The only way to gain access to the internals of a closure is for the function to provide access to it explicitly. In other words, objects and closures have opposite policies: The properties of an object are automatically exposed, whereas the variables in a closure are automatically hidden.

We can take advantage of this to store truly private data in an object. Instead of storing the data as properties of the object, we store it as variables in the constructor, and turn the methods of the object into closures that refer to those variables. Let’s revisit the User class from Item 30 once more:

function User(name, passwordHash) {

this.toString = function() {

return "[User " + name + "]";

};

this.checkPassword = function(password) {

return hash(password) === passwordHash;

};

}

Notice how, unlike in other implementations, the toString and checkPassword methods refer to name and passwordHash as variables, rather than as properties of this. An instance of User now contains no instance properties at all, so outside code has no direct access to the name and password hash of an instance of User.

A downside to this pattern is that, in order for the variables of the constructor to be in scope of the methods that use them, the methods must be placed on the instance object. Just as Item 34 discussed, this can lead to a proliferation of copies of methods. Nevertheless, in situations where guaranteed information hiding is critical, it may be worth the additional cost.

Things to Remember

• Closure variables are private, accessible only to local references.

• Use local variables as private data to enforce information hiding within methods.

Item 36: Store Instance State Only on Instance Objects

Understanding the one-to-many relationship between a prototype object and its instances is crucial to implementing objects that behave correctly. One of the ways this can go wrong is by accidentally storing per-instance data on a prototype. For example, a class implementing a tree data structure might contain an array of children for each node. Putting the array of children on the prototype object leads to a completely broken implementation:

function Tree(x) {

this.value = x;

}

Tree.prototype = {

children: [], // should be instance state!

addChild: function(x) {

this.children.push(x);

}

};

Consider what happens when we try to construct a tree with this class:

var left = new Tree(2);

left.addChild(1);

left.addChild(3);

var right = new Tree(6);

right.addChild(5);

right.addChild(7);

var top = new Tree(4);

top.addChild(left);

top.addChild(right);

top.children; // [1, 3, 5, 7, left, right]

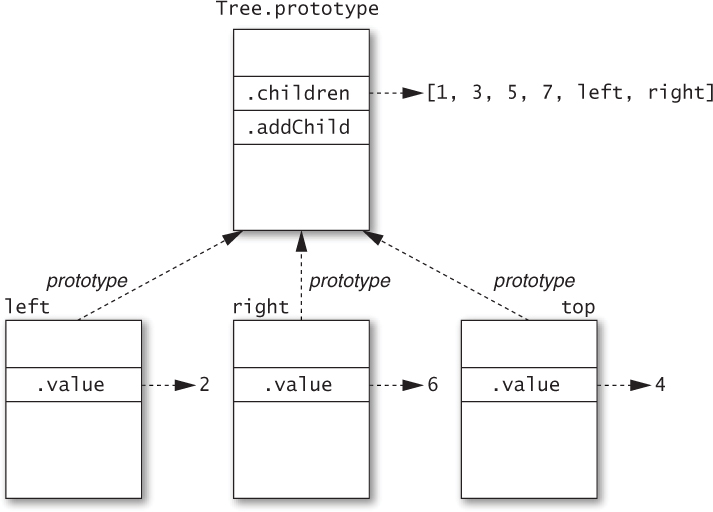

Each time we call addChild, we append a value to Tree.prototype .children, which contains the nodes in the order of any calls to addChild anywhere! This leaves the Tree objects in the incoherent state shown in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5. Storing instance state on a prototype object

The correct way to implement the Tree class is to create a separate children array for each instance object:

function Tree(x) {

this.value = x;

this.children = []; // instance state

}

Tree.prototype = {

addChild: function(x) {

this.children.push(x);

}

};

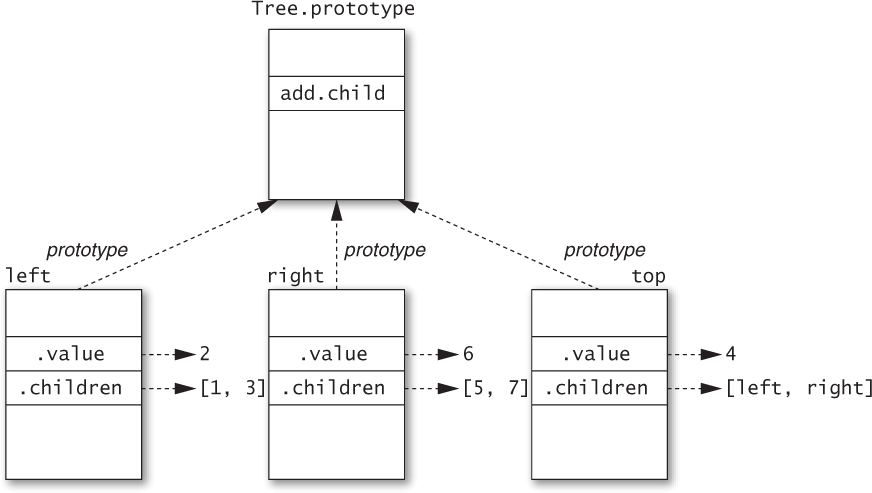

Running the same example code above, we get the expected state, shown in Figure 4.6.

Figure 4.6. Storing instance state on instance objects

The moral of this story is that stateful data can be problematic when shared. Methods are generally safe to share between multiple instances of a class because they are typically stateless, other than referring to instance state via references to this. (Since the method call syntax ensures that this is bound to the instance object even for a method inherited from a prototype, shared methods can still access instance state.) In general, any immutable data is safe to share on a prototype, and stateful data can in principle be stored on a prototype, too, so long as it’s truly intended to be shared. But methods are by far the most common data found on prototype objects. Per-instance state, meanwhile, must be stored on instance objects.

Things to Remember

• Mutable data can be problematic when shared, and prototypes are shared between all their instances.

• Store mutable per-instance state on instance objects.

Item 37: Recognize the Implicit Binding of this

The CSV (comma-separated values) file format is a simple text representation for tabular data:

Bösendorfer,1828,Vienna,Austria

Fazioli,1981,Sacile,Italy

Steinway,1853,New York,USA

We can write a simple, customizable class for reading CSV data. (For simplicity, we’ll leave off the ability to parse quoted entries such as "hello, world".) Despite its name, CSV comes in different varieties allowing different characters for separators. So our constructor takes an optional array of separator characters and constructs a custom regular expression to use for splitting each line into entries:

function CSVReader(separators) {

this.separators = separators || [","];

this.regexp =

new RegExp(this.separators.map(function(sep) {

return "\\" + sep[0];

}).join("|"));

}

A simple implementation of a read method can proceed in two steps: First, split the input string into an array of individual lines; second, split each line of the array into individual cells. The result should then be a two-dimensional array of strings. This is a perfect job for the map method:

CSVReader.prototype.read = function(str) {

var lines = str.trim().split(/\n/);

return lines.map(function(line) {

return line.split(this.regexp); // wrong this!

});

};

var reader = new CSVReader();

reader.read("a,b,c\nd,e,f\n"); // [["a,b,c"], ["d,e,f"]]

This seemingly simple code has a major but subtle bug: The callback passed to lines.map refers to this, expecting to extract the regexp property of the CSVReader object. But map binds its callback’s receiver to the lines array, which has no such property. The result: this.regexp produces undefined, and the call to line.split goes haywire.

This bug is the result of the fact that this is bound in a different way from variables. As Items 18 and 25 explain, every function has an implicit binding of this, whose value is determined when the function is called. With a lexically scoped variable, you can always tell where it receives its binding by looking for an explicitly named binding occurrence of the name: for example, in a var declaration list or as a function parameter. By contrast, this is implicitly bound by the nearest enclosing function. So the binding of this in CSVReader.prototype.read is different from the binding of this in the callback function passed to lines.map.

Luckily, similar to the forEach example in Item 25, we can take advantage of the fact that the map method of arrays takes an optional second argument to use as a this-binding for the callback. So in this case, the easiest fix is to forward the outer binding of this to the callback by way of the second map argument:

CSVReader.prototype.read = function(str) {

var lines = str.trim().split(/\n/);

return lines.map(function(line) {

return line.split(this.regexp);

}, this); // forward outer this-binding to callback

};

var reader = new CSVReader();

reader.read("a,b,c\nd,e,f\n");

// [["a","b","c"], ["d","e","f"]]

Now, not all callback-based APIs are so considerate. What if map did not accept this additional argument? We would need another way to retain access to the outer function’s this-binding so that the callback could still refer to it. The solution is straightforward enough: Just use a lexically scoped variable to save an additional reference to the outer binding of this:

CSVReader.prototype.read = function(str) {

var lines = str.trim().split(/\n/);

var self = this; // save a reference to outer this-binding

return lines.map(function(line) {

return line.split(self.regexp); // use outer this

});

};

var reader = new CSVReader();

reader.read("a,b,c\nd,e,f\n");

// [["a","b","c"], ["d","e","f"]]

Programmers commonly use the variable name self for this pattern, signaling that the only purpose for the variable is as an extra alias to the current scope’s this-binding. (Other popular variable names for this pattern are me and that.) The particular choice of name is not of great importance, but using a common name makes it easier for other programmers to recognize the pattern quickly.

Yet another valid approach in ES5 is to use the callback function’s bind method, similar to the approach described in Item 25:

CSVReader.prototype.read = function(str) {

var lines = str.trim().split(/\n/);

return lines.map(function(line) {

return line.split(this.regexp);

}.bind(this)); // bind to outer this-binding

};

var reader = new CSVReader();

reader.read("a,b,c\nd,e,f\n");

// [["a","b","c"], ["d","e","f"]]

Things to Remember

• The scope of this is always determined by its nearest enclosing function.

• Use a local variable, usually called self, me, or that, to make a this-binding available to inner functions.

Item 38: Call Superclass Constructors from Subclass Constructors

A scene graph is a collection of objects describing a scene in a visual program such as a game or graphical simulation. A simple scene contains a collection of all of the objects in the scene, known as actors, a table of preloaded image data for the actors, and a reference to the underlying graphics display, often known as the context:

function Scene(context, width, height, images) {

this.context = context;

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

this.images = images;

this.actors = [];

}

Scene.prototype.register = function(actor) {

this.actors.push(actor);

};

Scene.prototype.unregister = function(actor) {

var i = this.actors.indexOf(actor);

if (i >= 0) {

this.actors.splice(i, 1);

}

};

Scene.prototype.draw = function() {

this.context.clearRect(0, 0, this.width, this.height);

for (var a = this.actors, i = 0, n = a.length;

i < n;

i++) {

a[i].draw();

}

};

All actors in a scene inherit from a base Actor class, which abstracts out common methods. Every actor stores a reference to its scene along with coordinate positions and then adds itself to the scene’s actor registry:

function Actor(scene, x, y) {

this.scene = scene;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

scene.register(this);

}

To enable changing an actor’s position in the scene, we provide a moveTo method, which changes its coordinates and then redraws the scene:

Actor.prototype.moveTo = function(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.scene.draw();

};

When an actor leaves the scene, we remove it from the scene graph’s registry and redraw the scene:

Actor.prototype.exit = function() {

this.scene.unregister(this);

this.scene.draw();

};

To draw an actor, we look up its image in the scene graph image table. We’ll assume that every actor has a type field that can be used to look up its image in the image table. Once we have this image data, we can draw it onto the graphics context, using the underlying graphics library. (This example uses the HTML Canvas API, which provides a drawImage method for drawing an Image object onto a <canvas> element in a web page.)

Actor.prototype.draw = function() {

var image = this.scene.images[this.type];

this.scene.context.drawImage(image, this.x, this.y);

};

Similarly, we can determine an actor’s size from its image data:

Actor.prototype.width = function() {

return this.scene.images[this.type].width;

};

Actor.prototype.height = function() {

return this.scene.images[this.type].height;

};

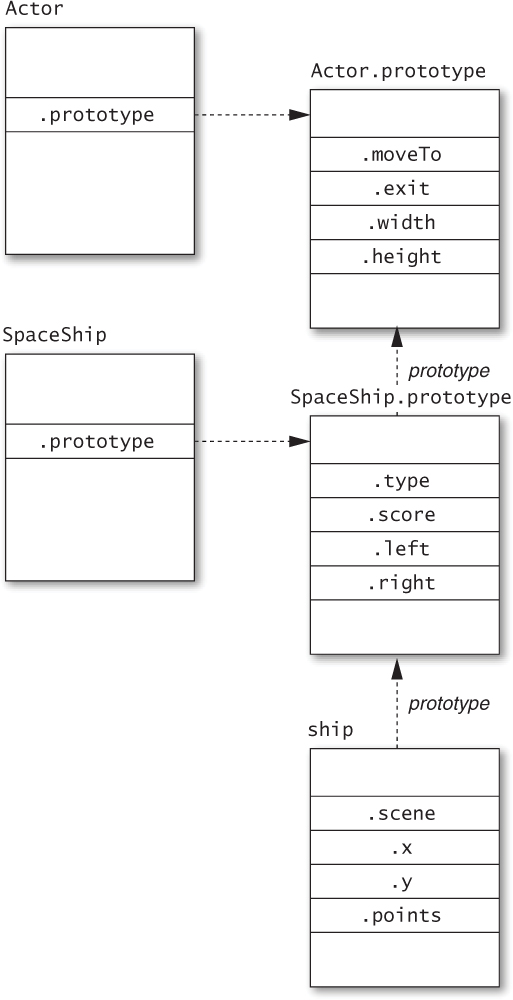

We implement specific types of actors as subclasses of Actor. For example, a spaceship in an arcade game would have a SpaceShip class that extends Actor. Like all classes, SpaceShip is defined as a constructor function. But in order to ensure that instances of SpaceShip are properly initialized as actors, the constructor must explicitly call the Actor constructor. We do this by invoking Actor with the receiver bound to the new object:

function SpaceShip(scene, x, y) {

Actor.call(this, scene, x, y);

this.points = 0;

}

Calling the Actor constructor first ensures that all the instance properties created by Actor are added to the new object. After that, SpaceShip can define its own instance properties such as the ship’s current points count.

In order for SpaceShip to be a proper subclass of Actor, its prototype must inherit from Actor.prototype. The best way to do the extension is with ES5’s Object.create:

SpaceShip.prototype = Object.create(Actor.prototype);

(Item 33 describes an implementation of Object.create for environments that do not support ES5.) If we had tried to create SpaceShip’s prototype object with the Actor constructor, there would be several problems. The first problem is that we don’t have any reasonable arguments to pass to Actor:

SpaceShip.prototype = new Actor();

When we initialize the SpaceShip prototype, we haven’t yet created any scenes to pass as the first argument. And the SpaceShip prototype doesn’t have a useful x or y coordinate. These properties should be instance properties of individual SpaceShip objects, not properties of SpaceShip.prototype. More problematically, the Actor constructor adds the object to the scene’s registry, which we definitely do not want to do with the SpaceShip prototype. This is a common phenomenon with subclasses: The superclass constructor should only be invoked from the subclass constructor, not when creating the subclass prototype.

Once we’ve created the SpaceShip prototype object, we can add all the properties that are shared by instances, including a type name for indexing into the scene’s table of image data and methods specific to spaceships.

SpaceShip.prototype.type = "spaceShip";

SpaceShip.prototype.scorePoint = function() {

this.points++;

};

SpaceShip.prototype.left = function() {

this.moveTo(Math.max(this.x - 10, 0), this.y);

};

SpaceShip.prototype.right = function() {

var maxWidth = this.scene.width - this.width();

this.moveTo(Math.min(this.x + 10, maxWidth), this.y);

};

Figure 4.7 shows a diagram of the inheritance hierarchy for instances of SpaceShip. Notice how the scene, x, and y properties are defined only on the instance object, rather than on any prototype object, despite being created by the Actor constructor.

Figure 4.7. An inheritance hierarchy with subclasses

Things to Remember

• Call the superclass constructor explicitly from subclass constructors, passing this as the explicit receiver.

• Use Object.create to construct the subclass prototype object to avoid calling the superclass constructor.

Item 39: Never Reuse Superclass Property Names

Imagine that we wish to add functionality to the scene graph library of Item 38 for collecting diagnostic information, which can be useful for debugging or profiling. To do this, we’d like to give each Actor instance a unique identification number:

function Actor(scene, x, y) {

this.scene = scene;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.id = ++Actor.nextID;

scene.register(this);

}

Actor.nextID = 0;

Now let’s do the same thing for individual instances of a subclass of Actor—say, an Alien class representing enemies of our spaceship. In addition to its actor identification number, we’d like each alien to have a separate alien identification number.

function Alien(scene, x, y, direction, speed, strength) {

Actor.call(this, scene, x, y);

this.direction = direction;

this.speed = speed;

this.strength = strength;

this.damage = 0;

this.id = ++Alien.nextID; // conflicts with actor id!

}

Alien.nextID = 0;

This code creates a conflict between the Alien class and its Actor superclass: Both classes attempt to write to an instance property called id. While each class may consider the property to be “private” (i.e., only relevant and accessible to methods defined directly on that class), the fact is that the property is stored on instance objects and named with a string. If two classes in an inheritance hierarchy refer to the same property name, they will refer to the same property.

As a result, subclasses must always be aware of all properties used by their superclasses, even if those properties are conceptually private. The obvious resolution in this case is to use distinct property names for the Actor identification number and Alien identification number:

function Actor(scene, x, y) {

this.scene = scene;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.actorID = ++Actor.nextID; // distinct from alienID

scene.register(this);

}

Actor.nextID = 0;

function Alien(scene, x, y, direction, speed, strength) {

Actor.call(this, scene, x, y);

this.direction = direction;

this.speed = speed;

this.strength = strength;

this.damage = 0;

this.alienID = ++Alien.nextID; // distinct from actorID

}

Alien.nextID = 0;

Things to Remember

• Be aware of all property names used by your superclasses.

• Never reuse a superclass property name in a subclass.

Item 40: Avoid Inheriting from Standard Classes

The ECMAScript standard library is small, but it comes with a handful of important classes such as Array, Function, and Date. It can be tempting to extend these with subclasses, but unfortunately their definitions have enough special behavior that well-behaved subclasses are impossible to write.

A good example is the Array class. A library for operating on file systems might wish to create an abstraction of directories that inherits all of the behavior of arrays:

function Dir(path, entries) {

this.path = path;

for (var i = 0, n = entries.length; i < n; i++) {

this[i] = entries[i];

}

}

Dir.prototype = Object.create(Array.prototype);

// extends Array

Unfortunately, this approach breaks the expected behavior of the length property of arrays:

var dir = new Dir("/tmp/mysite",

["index.html", "script.js", "style.css"]);

dir.length; // 0

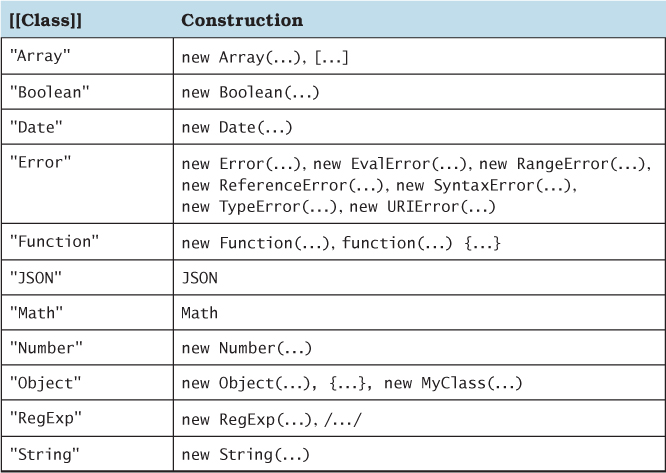

The reason this fails is that the length property operates specially on objects that are marked internally as “true” arrays. The ECMA-Script standard specifies this as an invisible internal property called [[Class]]. Don’t let the name mislead you—JavaScript doesn’t secretly have an internal class system. The value of [[Class]] is just a simple tag: Array objects (created by the Array constructor or the [] syntax) are stamped with the [[Class]] value "Array", functions are stamped with the [[Class]] value "Function", and so on. Table 4.1 shows the complete set of [[Class]] values defined by ECMAScript.

Table 4.1. Values of the [[Class]] Internal Property, As Defined by ECMAScript

So what does this magic [[Class]] property have to do with length? As it turns out, the behavior of length is defined specially for objects whose [[Class]] internal property has the value "Array". For these objects, the length property keeps itself in sync with the number of indexed properties of the object. If you add more indexed properties to the object, the length property increases itself automatically; if you decrease length, it automatically deletes any indexed properties beyond its new value.

But when we extend the Array class, instances of the subclass are not created by new Array() or the literal [] syntax. So instances of Dir have the [[Class]] "Object". There is even a test for this: The default Object.prototype.toString method queries the internal [[Class]] property of its receiver to create a generic description of an object, so you can call it explicitly on any given object and see:

var dir = new Dir("/", []);

Object.prototype.toString.call(dir); // "[object Object]"

Object.prototype.toString.call([]); // "[object Array]"

As a result, instances of Dir do not inherit the expected special behavior of the length property of arrays.

A better implementation defines an instance property with the array of entries:

function Dir(path, entries) {

this.path = path;

this.entries = entries; // array property

}

Array methods can be redefined on the prototype by delegating to the corresponding methods of the entries property:

Dir.prototype.forEach = function(f, thisArg) {

if (typeof thisArg === "undefined") {

thisArg = this;

}

this.entries.forEach(f, thisArg);

};

Most of the constructors of the ECMAScript standard library have similar problems, where certain properties or methods expect the right [[Class]] or other special internal properties that subclasses cannot provide. For this reason it’s advisable to avoid inheriting from any of the following standard classes: Array, Boolean, Date, Function, Number, RegExp, or String.

Things to Remember

• Inheriting from standard classes tends to break due to special internal properties such as [[Class]].

• Prefer delegating to properties instead of inheriting from standard classes.

Item 41: Treat Prototypes As an Implementation Detail

An object provides a small, simple, and powerful set of operations to its consumers. The most basic interactions a consumer has with an object are getting its property values and calling its methods. These operations do not particularly care where in a prototype hierarchy the properties are stored. The implementation of an object may evolve over time to implement a property in different places on the object’s prototype chain, but as long as its value remains consistent, these basic operations behave the same. Put simply: Prototypes are an implementation detail of an object’s behavior.

At the same time, JavaScript provides convenient introspection mechanisms for inspecting the details of an object. The Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty method determines whether a property is stored directly as an “own” property (i.e., an instance property) of an object, ignoring the prototype hierarchy completely. The Object.getPrototypeOf and __proto__ facilities (see Item 30) allow programs to traverse the prototype chain of an object and look at its prototype objects individually. These are powerful and sometimes useful features.

But a good programmer knows when to respect abstraction boundaries. Inspecting implementation details—even without modifying them—creates a dependency between components of a program. If the producer of an object changes its implementation details, the consumer that depends on them will break. These kinds of bugs can be especially difficult to diagnose because they constitute action at a distance: One author changes the implementation of one component, and another component (often written by a different programmer) breaks.

Similarly, JavaScript does not distinguish between public and private properties of an object (see Item 35). Instead, it’s your responsibility to rely on documentation and discipline. If a library provides an object with properties that are undocumented or specifically documented as internal, chances are good that those properties are best left alone by consumers.

Things to Remember

• Objects are interfaces; prototypes are implementations.

• Avoid inspecting the prototype structure of objects you don’t control.

• Avoid inspecting properties that implement the internals of objects you don’t control.

Item 42: Avoid Reckless Monkey-Patching

Having inveighed against violating abstractions in Item 41, let’s now consider the ultimate violation. Since prototypes are shared as objects, anyone can add, remove, or modify their properties. This controversial practice is commonly known as monkey-patching.

The appeal of monkey-patching lies in its power. Are arrays missing a useful method? Just add it yourself:

Array.prototype.split = function(i) { // alternative #1

return [this.slice(0, i), this.slice(i)];

};

Voilà: Every array instance has a split method.

But problems arise when multiple libraries monkey-patch the same prototypes in incompatible ways. Another library might monkey-patch Array.prototype with a method of the same name:

Array.prototype.split = function() { // alternative #2

var i = Math.floor(this.length / 2);

return [this.slice(0, i), this.slice(i)];

};

Any uses of split on an array now have roughly a 50% chance of being broken, depending on which of the two methods they expect.

At the very least, any library that modifies shared prototypes such as Array.prototype should clearly document that it does so. This at least gives clients adequate warning about potential conflicts between libraries. Nevertheless, two libraries that monkey-patch prototypes in conflicting ways cannot be used within the same program. One alternative is that if a library only monkey-patches prototypes as a convenience, it may provide the modifications in a function that users can choose to call or ignore:

function addArrayMethods() {

Array.prototype.split = function(i) {

return [this.slice(0, i), this.slice(i)];

};

};

Of course, this approach only works if the library providing addArrayMethods does not actually depend on Array.prototype.split.

Despite the hazards, there is one particularly reliable and invaluable use of monkey-patching: the polyfill. JavaScript programs and libraries are frequently deployed on multiple platforms, such as the different versions of web browsers made by different vendors. These platforms can differ in how many standard APIs they implement. For example, ES5 defines new Array methods such as forEach, map, and filter, and some versions of browsers may not support these methods. The behavior of the missing methods is defined by a widely supported standard, and many programs and libraries may depend on these methods. Since their behavior is standardized, providing implementations for these methods does not pose the same risk of incompatibility between libraries. In fact, multiple libraries can provide implementations for the same standard methods (assuming they are all correctly implemented), since they all implement the same standard API.

You can safely fill in these platform gaps by guarding monkey-patches with a test:

if (typeof Array.prototype.map !== "function") {

Array.prototype.map = function(f, thisArg) {

var result = [];

for (var i = 0, n = this.length; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = f.call(thisArg, this[i], i);

}

return result;

};

}

Testing for the presence of Array.prototype.map ensures that a built-in implementation, which is likely to be more efficient and better tested, won’t be overwritten.

Things to Remember

• Avoid reckless monkey-patching.

• Document any monkey-patching performed by a library.

• Consider making monkey-patching optional by performing the modifications in an exported function.

• Use monkey-patching to provide polyfills for missing standard APIs.