5. Arrays and Dictionaries

Objects are JavaScript’s most versatile data structure. Depending on the situation, an object can represent a fixed record of name-value associations, an object-oriented data abstraction with inherited methods, a dense or sparse array, or a hash table. Naturally, mastering such a multipurpose tool demands different idioms for different needs. In the preceding chapter we studied the use of structured objects and inheritance. This chapter tackles the use of objects as collections: aggregate data structures with varying numbers of elements.

Item 43: Build Lightweight Dictionaries from Direct Instances of Object

At its heart, a JavaScript object is a table mapping string property names to values. This makes objects pleasantly lightweight for implementing dictionaries: variable-sized collections mapping strings to values. JavaScript even provides a convenient construct for enumerating the property names of an object, the for...in loop:

var dict = { alice: 34, bob: 24, chris: 62 };

var people = [];

for (var name in dict) {

people.push(name + ": " + dict[name]);

}

people; // ["alice: 34", "bob: 24", "chris: 62"]

But every object also inherits properties from its prototype object (see Chapter 4), and the for...in loop enumerates an object’s inherited properties as well as its “own” properties. For example, what happens if we create a custom dictionary class that stores its elements as properties of the dictionary object itself?

function NaiveDict() { }

NaiveDict.prototype.count = function() {

var i = 0;

for (var name in this) { // counts every property

i++;

}

return i;

};

NaiveDict.prototype.toString = function() {

return "[object NaiveDict]";

};

var dict = new NaiveDict();

dict.alice = 34;

dict.bob = 24;

dict.chris = 62;

dict.count(); // 5

The problem is that we are using the same object to store both the fixed properties of the NaiveDict data structure (count, toString) and the variable entries of the specific dictionary (alice, bob, chris). So when count enumerates the properties of a dictionary, it counts all of these properties (count, toString, alice, bob, chris) instead of just the entries we care about. See Item 45 for an improved Dict class that does not store its elements as instance properties, instead providing dict.get(key) and dict.set(key, value) methods. In this Item we focus on the pattern of using object properties as dictionary elements.

A similar mistake is to use the Array type to represent dictionaries. This is an especially easy trap to fall into for programmers familiar with languages such as Perl and PHP, where dictionaries are commonly called “associative arrays.” Deceptively, since we can add properties to any type of JavaScript object this usage pattern will sometimes appear to work:

var dict = new Array();

dict.alice = 34;

dict.bob = 24;

dict.chris = 62;

dict.bob; // 24

Unfortunately, this code is vulnerable to prototype pollution, where properties on a prototype object can cause unexpected properties to appear when enumerating dictionary entries. For example, another library in the application may decide to add some convenience methods to Array.prototype:

Array.prototype.first = function() {

return this[0];

};

Array.prototype.last = function() {

return this[this.length – 1];

};

Now see what happens when we attempt to enumerate the elements of our array:

var names = [];

for (var name in dict) {

names.push(name);

}

names; // ["alice", "bob", "chris", "first", "last"]

This brings us to the primary rule of using objects as lightweight dictionaries: Only use direct instances of Object as dictionaries—not subclasses such as NaiveDict, and certainly not arrays. For example, we can simply replace new Array() above with new Object() or even an empty object literal. The result is much less susceptible to prototype pollution:

var dict = {};

dict.alice = 34;

dict.bob = 24;

dict.chris = 62;

var names = [];

for (var name in dict) {

names.push(name);

}

names; // ["alice", "bob", "chris"]

Now, our new version is still not guaranteed to be safe from pollution. Anyone could still come along and add properties to Object.prototype, and we’d be stuck again. But by using a direct instance of Object, we localize the risk to Object.prototype alone.

So how is this solution any better? For one, as Item 47 explains, nobody should ever add properties to Object.prototype that could pollute a for...in loop. By contrast, it’s not unreasonable to add properties to Array.prototype. For example, Item 42 explains how to add standard methods to Array.prototype in environments that don’t provide them. These properties end up polluting for...in loops. Similarly, a user-defined class will typically have properties on its prototype. Sticking to direct instances of Object (and always observing the rule of Item 47) keeps your for...in loops free of pollution.

But beware! As Items 44 and 45 attest, this rule is necessary but not sufficient for building well-behaved dictionaries. As convenient as lightweight dictionaries are, they suffer from a number of hazards. It’s important to study all three of these Items—or, if you prefer not to memorize the rules, use an abstraction like the Dict class of Item 45.

Things to Remember

• Use object literals to construct lightweight dictionaries.

• Lightweight dictionaries should be direct descendants of Object.prototype to protect against prototype pollution in for...in loops.

Item 44: Use null Prototypes to Prevent Prototype Pollution

One of the easiest ways to avoid prototype pollution is to just make it impossible in the first place. But before ES5, there was no standard way to create a new object with an empty prototype. You might be tempted to try setting a constructor’s prototype property to null or undefined:

function C() { }

C.prototype = null;

But instantiating this constructor still results in instances of Object:

var o = new C();

Object.getPrototypeOf(o) === null; // false

Object.getPrototypeOf(o) === Object.prototype; // true

ES5 offers the first standard way to create an object with no prototype. The Object.create function is capable of dynamically constructing objects with a user-specified prototype link and a property descriptor map, which describes the values and attributes of the new object’s properties. By simply passing a null prototype argument and an empty descriptor map, we can build a truly empty object:

var x = Object.create(null);

Object.getPrototypeOf(o) === null; // true

No amount of prototype pollution can affect the behavior of such an object.

Older JavaScript environments that do not support Object.create may support one other approach worth mentioning. In many environments, the special property __proto__ (see Items 31 and 32) provides magic read and write access to the internal prototype link of an object. The object literal syntax also supports initializing the prototype link of a new object to null:

var x = { __proto__: null };

x instanceof Object; // false (non-standard)

This syntax is equally convenient, but where Object.create is available, it is the more reliable approach. The __proto__ property is nonstandard and not all uses of it are portable. JavaScript implementations are not guaranteed to support it in the future, so you should stick to the standard Object.create where possible.

Sadly, while the nonstandard __proto__ can be used to solve some problems, it also causes an additional problem of its own, preventing prototype-free objects from being a truly robust implementation of dictionaries. Item 45 describes how in some JavaScript environments, the property key "__proto__" itself pollutes objects even when they have no prototype. If you can’t be sure that the string "__proto__" will never be used as a key in your dictionary, you should consider using the more robust Dict class described in Item 45.

Things to Remember

• In ES5, use Object.create(null) to create prototype-free empty objects that are less susceptible to pollution.

• In older environments, consider using { __proto__: null }.

• But beware that __proto__ is neither standard nor entirely portable and may be removed in future JavaScript environments.

• Never use the name "__proto__" as a dictionary key since some environments treat this property specially.

Item 45: Use hasOwnProperty to Protect Against Prototype Pollution

Items 43 and 44 talk about property enumeration, but we haven’t addressed the issue of prototype pollution in property lookup. It’s tempting to use JavaScript’s native syntax for object manipulation for all of our dictionary operations:

"alice" in dict; // membership test

dict.alice; // retrieval

dict.alice = 24; // update

But remember that JavaScript’s object operations always work with inheritance. Even an empty object literal inherits a number of properties from Object.prototype:

var dict = {};

"alice" in dict; // false

"bob" in dict; // false

"chris" in dict; // false

"toString" in dict; // true

"valueOf" in dict; // true

Luckily, Object.prototype provides the hasOwnProperty method, which is just the tool we need to avoid prototype pollution when testing for dictionary entries:

dict.hasOwnProperty("alice"); // false

dict.hasOwnProperty("toString"); // false

dict.hasOwnProperty("valueOf"); // false

Similarly, we can protect property lookups against pollution by guarding the lookup with a test:

dict.hasOwnProperty("alice") ? dict.alice : undefined;

dict.hasOwnProperty(x) ? dict[x] : undefined;

Unfortunately, we aren’t quite done. When we call dict.hasOwnProperty, we’re asking to look up the hasOwnProperty method of dict. Normally this would simply be inherited from Object.prototype. But if we store an entry in the dictionary under the name "hasOwnProperty", the prototype’s method is no longer accessible:

dict.hasOwnProperty = 10;

dict.hasOwnProperty("alice");

// error: dict.hasOwnProperty is not a function

You might be thinking that a dictionary would never store an entry with a name as exotic as "hasOwnProperty". And of course, it’s up to you in the context of any given program to decide that this isn’t a scenario you ever expect to happen. But it certainly can happen, especially if you’re filling the dictionary with entries from an external file, network resource, or user interface input, where third parties beyond your control get to decide what keys end up in the dictionary.

The safest approach is to make no assumptions. Instead of calling hasOwnProperty as a method of the dictionary, we can use the call method described in Item 20. First we extract the hasOwnProperty method in advance from any well-known location:

var hasOwn = Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty;

Or more concisely:

var hasOwn = {}.hasOwnProperty;

Now that we have a local variable bound to the proper function, we can call it on any object by using the function’s call method:

hasOwn.call(dict, "alice");

This approach works regardless of whether its receiver has overridden its hasOwnProperty method:

var dict = {};

dict.alice = 24;

hasOwn.call(dict, "hasOwnProperty"); // false

hasOwn.call(dict, "alice"); // true

dict.hasOwnProperty = 10;

hasOwn.call(dict, "hasOwnProperty"); // true

hasOwn.call(dict, "alice"); // true

To avoid inserting this boilerplate everywhere we do a lookup, we can abstract out this pattern into a Dict constructor that encapsulates all of the techniques for writing robust dictionaries in a single datatype definition:

function Dict(elements) {

// allow an optional initial table

this.elements = elements || {}; // simple Object

}

Dict.prototype.has = function(key) {

// own property only

return {}.hasOwnProperty.call(this.elements, key);

};

Dict.prototype.get = function(key) {

// own property only

return this.has(key)

? this.elements[key]

: undefined;

};

Dict.prototype.set = function(key, val) {

this.elements[key] = val;

};

Dict.prototype.remove = function(key) {

delete this.elements[key];

};

Notice that we don’t protect the implementation of Dict.prototype.set, since adding the key to the dictionary object becomes one of the elements object’s own properties, even if there is a property of the same name in Object.prototype.

This abstraction is more robust than using JavaScript’s default object syntax and almost as convenient to use:

var dict = new Dict({

alice: 34,

bob: 24,

chris: 62

});

dict.has("alice"); // true

dict.get("bob"); // 24

dict.has("valueOf"); // false

Recall from Item 44 that in some JavaScript environments, the special property name __proto__ can cause pollution problems of its own. In some environments, the __proto__ property is simply inherited from Object.prototype, so empty objects are (mercifully) truly empty:

var empty = Object.create(null);

"__proto__" in empty;

// false (in some environments)

var hasOwn = {}.hasOwnProperty;

hasOwn.call(empty, "__proto__");

// false (in some environments)

In others, only the in operator reports true:

var empty = Object.create(null);

"__proto__" in empty; // true (in some environments)

var hasOwn = {}.hasOwnProperty;

hasOwn.call(empty, "__proto__"); // false (in some

environments)

But unfortunately, some environments permanently pollute all objects with the appearance of an instance property called __proto__:

var empty = Object.create(null);

"__proto__" in empty; // true (in some environments)

var hasOwn = {}.hasOwnProperty;

hasOwn.call(empty, "__proto__"); // true (in some environments)

This means that depending on the environment, the following code could have different results:

var dict = new Dict();

dict.has("__proto__"); // ?

For maximum portability and safety, this leaves us with no choice but to add a special case for the "__proto__" key to each of the Dict methods, resulting in the following more complex but safer final implementation:

function Dict(elements) {

// allow an optional initial table

this.elements = elements || {}; // simple Object

this.hasSpecialProto = false; // has "__proto__" key?

this.specialProto = undefined; // "__proto__" element

}

Dict.prototype.has = function(key) {

if (key === "__proto__") {

return this.hasSpecialProto;

}

// own property only

return {}.hasOwnProperty.call(this.elements, key);

};

Dict.prototype.get = function(key) {

if (key === "__proto__") {

return this.specialProto;

}

// own property only

return this.has(key)

? this.elements[key]

: undefined;

};

Dict.prototype.set = function(key, val) {

if (key === "__proto__") {

this.hasSpecialProto = true;

this.specialProto = val;

} else {

this.elements[key] = val;

}

};

Dict.prototype.remove = function(key) {

if (key === "__proto__") {

this.hasSpecialProto = false;

this.specialProto = undefined;

} else {

delete this.elements[key];

}

};

This implementation is guaranteed to work regardless of an environment’s handling of __proto__, since it avoids ever dealing with properties of that name:

var dict = new Dict();

dict.has("__proto__"); // false

Things to Remember

• Use hasOwnProperty to protect against prototype pollution.

• Use lexical scope and call to protect against overriding of the hasOwnProperty method.

• Consider implementing dictionary operations in a class that encapsulates the boilerplate hasOwnProperty tests.

• Use a dictionary class to protect against the use of "__proto__" as a key.

Item 46: Prefer Arrays to Dictionaries for Ordered Collections

Intuitively, a JavaScript object is an unordered collection of properties. Getting and setting different properties should work in any order, producing the same results and roughly the same efficiency. The ECMAScript standard does not specify any particular order of property storage and is even largely mum on the subject of enumeration.

But here’s the catch: A for...in loop has to pick some order to enumerate an object’s properties. And since the standard allows JavaScript engines the freedom to choose an order, their choice can subtly change your program’s behavior. A common mistake is to provide an API that requires an object representing an ordered mapping from strings to values, such as for creating an ordered report:

function report(highScores) {

var result = "";

var i = 1;

for (var name in highScores) { // unpredictable order

result += i + ". " + name + ": " +

highScores[name] + "\n";

i++;

}

return result;

}

report([{ name: "Hank", points: 1110100 },

{ name: "Steve", points: 1064500 },

{ name: "Billy", points: 1050200 }]);

// ?

Because different environments may choose to store and enumerate the properties of the object in different orders, this function can result in different strings, potentially jumbling the order of the “high scores” report.

Keep in mind that it may not always be obvious whether your program depends on the order of object enumeration. If you don’t test your program in multiple JavaScript environments, you may not even notice that its behavior can change based on the exact ordering of a for...in loop.

If you need to depend on the order of entries in a data structure, use an array instead of a dictionary. The report function above would work completely predictably in any JavaScript environment if its API expected an array of objects instead of a single object:

function report(highScores) {

var result = "";

for (var i = 0, n = highScores.length; i < n; i++) {

var score = highScores[i];

result += (i + 1) + ". " +

score.name + ": " + score.points + "\n";

}

return result;

}

report([{ name: "Hank", points: 1110100 },

{ name: "Steve", points: 1064500 },

{ name: "Billy", points: 1050200 }]);

// "1. Hank: 1110100\n2. Steve: 1064500\n3. Billy: 1050200\n"

By accepting an array of objects, each with a name and points property, this version predictably iterates over the elements in a precise order: from 0 to highScores.length – 1.

A terrific source of subtle order dependencies is floating-point arithmetic. Consider a dictionary of films that maps titles to ratings:

var ratings = {

"Good Will Hunting": 0.8,

"Mystic River": 0.7,

"21": 0.6,

"Doubt": 0.9

};

As we saw in Item 2, rounding in floating-point arithmetic can lead to subtle dependencies on the order of operations. When combined with undefined order of enumeration, this can lead to some unpredictable loops:

var total = 0, count = 0;

for (var key in ratings) { // unpredictable order

total += ratings[key];

count++;

}

total /= count;

total; // ?

As it turns out, popular JavaScript environments do in fact perform this loop in different orders. For example, some environments enumerate object keys in the order in which they are added to the object, effectively computing:

(0.8 + 0.7 + 0.6 + 0.9) / 4 // 0.75

Others always enumerate potential array indices first before any other keys. Since the movie 21 happens to have a name that is a viable array index, it gets enumerated first, resulting in:

(0.6 + 0.8 + 0.7 + 0.9) / 4 // 0.7499999999999999

In this case, a better representation is to use integer values in the dictionary, since integer addition can be performed in any order. This way, the sensitive division operations are performed only at the very end—crucially, after the loop is complete:

(8 + 7 + 6 + 9) / 4 / 10 // 0.75

(6 + 8 + 7 + 9) / 4 / 10 // 0.75

In general, you should always take care when executing a for...in loop that the operations you perform behave the same regardless of their order.

Things to Remember

• Avoid relying on the order in which for...in loops enumerate object properties.

• If you aggregate data in a dictionary, make sure the aggregate operations are order-insensitive.

• Use arrays instead of dictionary objects for ordered collections.

Item 47: Never Add Enumerable Properties to Object.prototype

The for...in loop is awfully convenient, but as we saw in Item 43 it is susceptible to prototype pollution. Now, the most common use of for...in by far is enumerating the elements of a dictionary. The implication is unavoidable: If you want to permit the use of for...in on dictionary objects, never add enumerable properties to the shared Object.prototype.

This rule may come as a great disappointment: What could be more powerful than adding convenience methods to Object.prototype that suddenly all objects can share? For example, what if we added an allKeys method that produces an array of an object’s property names?

Object.prototype.allKeys = function() {

var result = [];

for (var key in this) {

result.push(key);

}

return result;

};

Sadly, this method pollutes even its own result:

({ a: 1, b: 2, c: 3 }).allKeys(); // ["allKeys", "a", "b", "c"]

Of course, we could always improve our allKeys method to ignore properties of Object.prototype. But with freedom comes responsibility, and our actions on a highly shared prototype object have consequences on everyone who uses that object. Just by adding one single property to Object.prototype, we force everyone everywhere to protect his for...in loops.

It is slightly less convenient, but ultimately much more cooperative, to define allKeys as a function rather than as a method.

function allKeys(obj) {

var result = [];

for (var key in obj) {

result.push(key);

}

return result;

}

But if you do want to add properties to Object.prototype, ES5 provides a mechanism for doing it more cooperatively. The Object.defineProperty method makes it possible to define an object property simultaneously with metadata about the property’s attributes. For example, we can define the above property exactly as before but make it invisible to for...in by setting its enumerable attribute to false:

Object.defineProperty(Object.prototype, "allKeys", {

value: function() {

var result = [];

for (var key in this) {

result.push(key);

}

return result;

},

writable: true,

enumerable: false,

configurable: true

});

Admittedly, this code is a mouthful. But this version has the distinct advantage of not polluting every other for...in loop over every other instance of Object.

In fact, it’s worth using this technique for other objects as well. Whenever you need to add a property that should not be visible to for...in loops, Object.defineProperty is your friend.

Things to Remember

• Avoid adding properties to Object.prototype.

• Consider writing a function instead of an Object.prototype method.

• If you do add properties to Object.prototype, use ES5’s Object.defineProperty to define them as nonenumerable properties.

Item 48: Avoid Modifying an Object during Enumeration

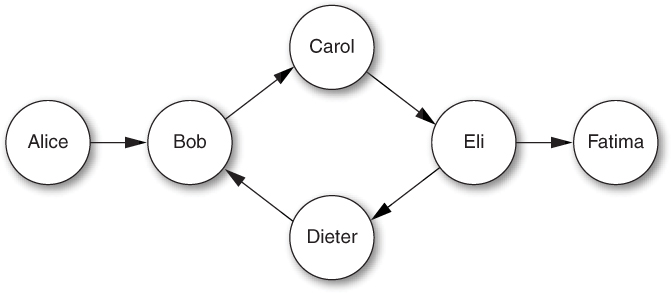

A social network has a set of members and, for each member, a registered list of friends:

function Member(name) {

this.name = name;

this.friends = [];

}

var a = new Member("Alice"),

b = new Member("Bob"),

c = new Member("Carol"),

d = new Member("Dieter"),

e = new Member("Eli"),

f = new Member("Fatima");

a.friends.push(b);

b.friends.push(c);

c.friends.push(e);

d.friends.push(b);

e.friends.push(d, f);

Searching that network means traversing the social network graph (see Figure 5.1). This is often implemented with a work-set, which starts with a single root node, and has nodes added as they are discovered and removed as they are visited. It may be tempting to try to implement this traversal with a single for...in loop:

Figure 5.1. A social network graph

Member.prototype.inNetwork = function(other) {

var visited = {};

var workset = {};

workset[this.name] = this;

for (var name in workset) {

var member = workset[name];

delete workset[name]; // modified while enumerating

if (name in visited) { // don't revisit members

continue;

}

visited[name] = member;

if (member === other) { // found?

return true;

}

member.friends.forEach(function(friend) {

workset[friend.name] = friend;

});

}

return false;

};

Unfortunately, in many JavaScript environments this code doesn’t work at all:

a.inNetwork(f); // false

What happened? As it turns out, a for...in loop is not required to keep current with modifications to the object being enumerated. In fact, the ECMAScript standard leaves room for different JavaScript environments to behave differently with respect to concurrent modifications. In particular, the standard states:

If new properties are added to the object being enumerated during enumeration, the newly added properties are not guaranteed to be visited in the active enumeration.

The practical consequence of this underspecification is that we cannot rely on for...in loops to behave predictably if we modify the object being enumerated.

Let’s give our graph traversal another try, this time managing the loop control ourselves. While we’re at it, we should use our dictionary abstraction to avoid prototype pollution. We can place the dictionary in a WorkSet class that tracks the number of elements currently in the set:

function WorkSet() {

this.entries = new Dict();

this.count = 0;

}

WorkSet.prototype.isEmpty = function() {

return this.count === 0;

};

WorkSet.prototype.add = function(key, val) {

if (this.entries.has(key)) {

return;

}

this.entries.set(key, val);

this.count++;

};

WorkSet.prototype.get = function(key) {

return this.entries.get(key);

};

WorkSet.prototype.remove = function(key) {

if (!this.entries.has(key)) {

return;

}

this.entries.remove(key);

this.count--;

};

In order to pick an arbitrary element of the set, we need a new method for the Dict class:

Dict.prototype.pick = function() {

for (var key in this.elements) {

if (this.has(key)) {

return key;

}

}

throw new Error("empty dictionary");

};

WorkSet.prototype.pick = function() {

return this.entries.pick();

};

Now we can implement inNetwork with a simple while loop, choosing arbitrary elements one at a time and removing them from the work-set.

Member.prototype.inNetwork = function(other) {

var visited = {};

var workset = new WorkSet();

workset.add(this.name, this);

while (!workset.isEmpty()) {

var name = workset.pick();

var member = workset.get(name);

workset.remove(name);

if (name in visited) { // don't revisit members

continue;

}

visited[name] = member;

if (member === other) { // found?

return true;

}

member.friends.forEach(function(friend) {

workset.add(friend.name, friend);

});

}

return false;

};

The pick method is an example of nondeterminism: an operation that is not guaranteed by the language semantics to produce a single, predictable result. This nondeterminism comes from the fact that the for...in loop may choose a different order of enumeration in different JavaScript environments (or even in different executions within the same JavaScript environment, at least in principle). Working with nondeterminism can be tricky, because it introduces an element of unpredictability into your program. Tests that pass on one platform may fail on others or even fail intermittently on the same platform.

Some sources of nondeterminism are unavoidable. A random number generator is supposed to produce unpredictable results; checking the current date and time always gets a different answer; responding to user actions such as mouse clicks or keystrokes necessarily behaves differently depending on the user. But it’s a good idea to be clear about what parts of a program have a single expected result and which parts can vary.

For these reasons, it’s worth considering using a deterministic alternative to a work-set algorithm: a work-list algorithm. By storing work items in an array instead of a set, the inNetwork method always traverses the graph in exactly the same order.

Member.prototype.inNetwork = function(other) {

var visited = {};

var worklist = [this];

while (worklist.length > 0) {

var member = worklist.pop();

if (member.name in visited) { // don't revisit

continue;

}

visited[member.name] = member;

if (member === other) { // found?

return true;

}

member.friends.forEach(function(friend) {

worklist.push(friend); // add to work-list

});

}

return false;

};

This version of inNetwork adds and removes work items deterministically. Since the method always returns true for connected members no matter what path it finds, the end result is the same. But this may not be the case for other methods you might care to write, such as a variation on inNetwork that produces the actual path found through the graph from member to member.

Things to Remember

• Make sure not to modify an object while enumerating its properties with a for...in loop.

• Use a while loop or classic for loop instead of a for...in loop when iterating over an object whose contents might change during the loop.

• For predictable enumeration over a changing data structure, consider using a sequential data structure such as an array instead of a dictionary object.

Item 49: Prefer for Loops to for...in Loops for Array Iteration

What is the value of mean in this code?

var scores = [98, 74, 85, 77, 93, 100, 89];

var total = 0;

for (var score in scores) {

total += score;

}

var mean = total / scores.length;

mean; // ?

Did you spot the bug? If you said the answer was 88, you understood the intention of the program but not its actual result. This program commits the all-too-easy mistake of confusing the keys and values of an array of numbers. A for...in loop always enumerates the keys. A plausible next guess would be (0 + 1 + ... + 6) / 7 = 21, but even that is incorrect. Remember that object property keys are always strings, even the indexed properties of an array. So the += operation ends up performing string concatenation, resulting in an unintended total of "00123456". The end result? An implausible mean value of 17636.571428571428.

The proper way to iterate over the contents of an array is to use a classic for loop.

var scores = [98, 74, 85, 77, 93, 100, 89];

var total = 0;

for (var i = 0, n = scores.length; i < n; i++) {

total += scores[i];

}

var mean = total / scores.length;

mean; // 88

This approach ensures that you have integer indices when you need them and array element values when you need them, and that you never confuse the two or trigger unexpected coercions to strings. Moreover, it ensures that the iteration occurs in the proper order and does not accidentally include noninteger properties stored on the array object or in its prototype chain.

Notice the use of the array length variable n in the for loop above. If the loop body does not modify the array, the loop behavior is identical to simply recalculating the array length on every iteration:

for (var i = 0; i < scores.length; i++) { ... }

Still, there are a couple of small benefits to computing the array length once ahead of the loop. First, even optimizing JavaScript compilers may sometimes find it difficult to prove that it is safe to avoid recomputing scores.length. But more importantly, it communicates to the person reading the code that the loop’s termination condition is simple and fixed.

Things to Remember

• Always use a for loop rather than a for...in loop for iterating over the indexed properties of an array.

• Consider storing the length property of an array in a local variable before a loop to avoid recomputing the property lookup.

Item 50: Prefer Iteration Methods to Loops

Good programmers hate writing the same code twice. Copying and pasting boilerplate code duplicates bugs, makes programs harder to change, clutters up programs with repetitive patterns, and leaves programmers endlessly reinventing the wheel. Perhaps worst of all, repetition makes it too easy for someone reading a program to overlook minor differences from one instance of a pattern to another.

JavaScript’s for loops are reasonably concise and certainly familiar from many other languages such as C, Java, and C#, but they allow for quite different behavior with only slight syntactic variation. Some of the most notorious bugs in programming result from simple mistakes in determining the termination condition of a loop:

for (var i = 0; i <= n; i++) { ... }

// extra end iteration

for (var i = 1; i < n; i++) { ... }

// missing first iteration

for (var i = n; i >= 0; i--) { ... }

// extra start iteration

for (var i = n - 1; i > 0; i--) { ... }

// missing last iteration

Let’s face it: Figuring out termination conditions is a drag. It’s boring and there are just too many little ways to mess up.

Thankfully, JavaScript’s closures (see Item 11) are a convenient and expressive way to build iteration abstractions for these patterns that save us from having to copy and paste loop headers.

ES5 provides convenience methods for some of the most common patterns. Array.prototype.forEach is the simplest of these. Instead of writing:

for (var i = 0, n = players.length; i < n; i++) {

players[i].score++;

}

we can write:

players.forEach(function(p) {

p.score++;

});

This code is not only more concise and readable, but it also eliminates the termination condition and any mention of array indices.

Another common pattern is to build a new array by doing something to each element of another array. We could do this with a loop:

var trimmed = [];

for (var i = 0, n = input.length; i < n; i++) {

trimmed.push(input[i].trim());

}

Alternatively, we could do this with forEach:

var trimmed = [];

input.forEach(function(s) {

trimmed.push(s.trim());

});

But this pattern of building a new array from an existing array is so common that ES5 introduced Array.prototype.map to make it simpler and more elegant:

var trimmed = input.map(function(s) {

return s.trim();

});

Another common pattern is to compute a new array containing only some of the elements of an existing array. Array.prototype.filter makes this straightforward: It takes a predicate—a function that produces a truthy value if the element should be kept in the new array, and a falsy value if the element should be dropped. For example, we can extract from a price list only those listings that fall within a particular price range:

listings.filter(function(listing) {

return listing.price >= min && listing.price <= max;

});

Of course, these are just methods available by default in ES5. There’s nothing stopping us from defining our own iteration abstractions. For example, one pattern that sometimes comes up is extracting the longest prefix of an array that satisfies a predicate:

function takeWhile(a, pred) {

var result = [];

for (var i = 0, n = a.length; i < n; i++) {

if (!pred(a[i], i)) {

break;

}

result[i] = a[i];

}

return result;

}

var prefix = takeWhile([1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32], function(n) {

return n < 10;

}); // [1, 2, 4, 8]

Notice that we pass the array index i to pred, which it can choose to use or ignore. In fact, all of the iteration functions in the standard library, including forEach, map, and filter, pass the array index to the user-provided function.

We could also define takeWhile as a method by adding it to Array.prototype (see Item 42 for a discussion of the consequences of monkey-patching standard prototypes like Array.prototype):

Array.prototype.takeWhile = function(pred) {

var result = [];

for (var i = 0, n = this.length; i < n; i++) {

if (!pred(this[i], i)) {

break;

}

result[i] = this[i];

}

return result;

};

var prefix = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32].takeWhile(function(n) {

return n < 10;

}); // [1, 2, 4, 8]

There is one thing that loops tend to do better than iteration functions: abnormal control flow operations such as break and continue. For example, it would be awkward to attempt to implement takeWhile using forEach:

function takeWhile(a, pred) {

var result = [];

a.forEach(function(x, i) {

if (!pred(x)) {

// ?

}

result[i] = x;

});

return result;

}

We could use an internal exception to implement the early termination of the loop, but this would be awkward and likely inefficient:

function takeWhile(a, pred) {

var result = [];

var earlyExit = {}; // unique value signaling loop break

try {

a.forEach(function(x, i) {

if (!pred(x)) {

throw earlyExit;

}

result[i] = x;

});

} catch (e) {

if (e !== earlyExit) { // only catch earlyExit

throw e;

}

}

return result;

}

Once an abstraction becomes more verbose than the code it is replacing, it’s a pretty sure sign that the cure is worse than the disease.

Alternatively, the ES5 array methods some and every can be used as loops that may terminate early. Arguably, these methods were not created for this purpose; they are described as predicates, applying a callback predicate repeatedly to each element of an array. Specifically, the some method returns a boolean indicating whether its callback returns a truthy value for any one of the array elements:

[1, 10, 100].some(function(x) { return x > 5; }); // true

[1, 10, 100].some(function(x) { return x < 0; }); // false

Analogously, every returns a boolean indicating whether its callback returns a truthy value for all of the elements:

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].every(function(x) { return x > 0; }); // true

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].every(function(x) { return x < 3; }); // false

Both methods are short-circuiting: If the callback to some ever produces a truthy value, some returns without processing any more elements; similarly, every returns immediately if its callback produces a falsy value.

This behavior makes these methods useful as a variant of forEach that can terminate early. For example, we can implement takeWhile with every:

function takeWhile(a, pred) {

var result = [];

a.every(function(x, i) {

if (!pred(x)) {

return false; // break

}

result[i] = x;

return true; // continue

});

return result;

}

Things to Remember

• Use iteration methods such as Array.prototype.forEach and Array.prototype.map in place of for loops to make code more readable and avoid duplicating loop control logic.

• Use custom iteration functions to abstract common loop patterns that are not provided by the standard library.

• Traditional loops can still be appropriate in cases where early exit is necessary; alternatively, the some and every methods can be used for early exit.

Item 51: Reuse Generic Array Methods on Array-Like Objects

The standard methods of Array.prototype were designed to be reusable as methods of other objects—even objects that do not inherit from Array. As it turns out, a number of such array-like objects crop up in various places in JavaScript.

A good example is a function’s arguments object, described in Item 22. Unfortunately, the arguments object does not inherit from Array.prototype, so we cannot simply call arguments.forEach to iterate over each argument. Instead, we have to extract a reference to the forEach method object and use its call method (see Item 20):

function highlight() {

[].forEach.call(arguments, function(widget) {

widget.setBackground("yellow");

});

}

The forEach method is a Function object, which means it inherits the call method from Function.prototype. This lets us call forEach with a custom value for its internal binding of this (in our case, the arguments object), followed by any number of arguments (in our case, the single callback function). In other words, this code behaves just like we want.

On the web platform, the DOM’s NodeList class is another instance of an array-like object. Operations such as document.getElementsByTagName that query a web page for nodes produce their search results as NodeLists. Like the arguments object, a NodeList acts like an array but does not inherit from Array.prototype.

So what exactly makes an object “array-like”? The basic contract of an array object amounts to two simple rules.

• It has an integer length property in the range 0...232 – 1.

• The length property is greater than the largest index of the object. An index is an integer in the range 0...232 – 2 whose string representation is the key of a property of the object.

This is all the behavior an object needs to implement to be compatible with any of the methods of Array.prototype. Even a simple object literal can be used to create an array-like object:

var arrayLike = { 0: "a", 1: "b", 2: "c", length: 3 };

var result = Array.prototype.map.call(arrayLike, function(s) {

return s.toUpperCase();

}); // ["A", "B", "C"]

Strings act like immutable arrays, too, since they can be indexed and their length can be accessed as a length property. So the Array.prototype methods that do not modify their array work with strings:

var result = Array.prototype.map.call("abc", function(s) {

return s.toUpperCase();

}); // ["A", "B", "C"]

Now, simulating all the behavior of a JavaScript array is trickier, thanks to two more aspects of the behavior of arrays.

• Setting the length property to a smaller value n automatically deletes any properties with an index greater than or equal to n.

• Adding a property with an index n that is greater than or equal to the value of the length property automatically sets the length property to n + 1.

The second of these rules is a particularly tall order, since it requires monitoring the addition of indexed properties in order to update length automatically. Thankfully, neither of these two rules is necessary for the purpose of using Array.prototype methods, since they all forcibly update the length property whenever they add or remove indexed properties.

There is just one Array method that is not fully generic: the array concatenation method concat. This method can be called on any array-like receiver, but it tests the [[Class]] of its arguments. If an argument is a true array, its contents are concatenated to the result; otherwise, the argument is added as a single element. This means, for example, that we can’t simply concatenate an array with the contents of an arguments object:

function namesColumn() {

return ["Names"].concat(arguments);

}

namesColumn("Alice", "Bob", "Chris");

// ["Names", { 0: "Alice", 1: "Bob", 2: "Chris" }]

In order to convince concat to treat an array-like object as a true array, we have to convert it ourselves. A popular and concise idiom for doing this conversion is to call the slice method on the array-like object:

function namesColumn() {

return ["Names"].concat([].slice.call(arguments));

}

namesColumn("Alice", "Bob", "Chris");

// ["Names", "Alice", "Bob", "Chris"]

Things to Remember

• Reuse generic Array methods on array-like objects by extracting method objects and using their call method.

• Any object can be used with generic Array methods if it has indexed properties and an appropriate length property.

Item 52: Prefer Array Literals to the Array Constructor

JavaScript’s elegance owes a lot to its concise literal syntax for the most common building blocks of JavaScript programs: objects, functions, and arrays. A literal is a lovely way to express an array:

var a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

Now, you could use the Array constructor instead:

var a = new Array(1, 2, 3, 4, 5);

But even setting aside aesthetics, it turns out that the Array constructor has some subtle issues. For one, you have to be sure that no one has rebound the Array variable:

function f(Array) {

return new Array(1, 2, 3, 4, 5);

}

f(String); // new String(1)

You also have to be sure that no one has modified the global Array variable:

Array = String;

new Array(1, 2, 3, 4, 5); // new String(1)

There’s one more special case to worry about. If you call the Array constructor with a single numeric argument, it does something completely different: It attempts to create an array with no elements but whose length property is the given argument. This means that ["hello"] and new Array("hello") behave the same, but [17] and new Array(17) do completely different things!

These are not necessarily difficult rules to learn, but it’s clearer and less prone to accidental bugs to use array literals, which have more regular, consistent semantics.

Things to Remember

• The Array constructor behaves differently if its first argument is a number.

• Use array literals instead of the Array constructor.