2. Variable Scope

Scope is like oxygen to a programmer. It’s everywhere. You often don’t even think about it. But when it gets polluted . . . you choke.

The good news is that JavaScript’s core scoping rules are simple, well designed, and incredibly powerful. But there are exceptions. Working effectively with JavaScript requires mastering some basic concepts of variable scope as well as the corner cases that can lead to subtle but nasty problems.

Item 8: Minimize Use of the Global Object

JavaScript makes it easy to create variables in its global namespace. Global variables take less effort to create, since they don’t require any kind of declaration, and they are automatically accessible to all code throughout the program. This convenience makes them an easy temptation for beginners. But seasoned programmers know to avoid global variables. Defining global variables pollutes the common namespace shared by everyone, introducing the possibility of accidental name collisions. Globals go against the grain of modularity: They lead to unnecessary coupling between separate components of a program. As convenient as it may be to “code now and organize later,” the best programmers constantly pay attention to the structure of their programs, continuously grouping related functionality and separating unrelated components as a part of the programming process.

Since the global namespace is the only real way for separate components of a JavaScript program to interact, some uses of the global namespace are unavoidable. A component or library has to define a global name so that other parts of the program can use it. Otherwise, it’s best to keep variables as local as possible. It’s certainly possible to write a program with nothing but global variables, but it’s asking for trouble. Even very simple functions that define their temporary variables globally would have to worry whether any other code might use those same variable names:

var i, n, sum; // globals

function averageScore(players) {

sum = 0;

for (i = 0, n = players.length; i < n; i++) {

sum += score(players[i]);

}

return sum / n;

}

This definition of averageScore won’t work if the score function it depends on uses any of the same global variables for its own purposes:

var i, n, sum; // same globals as averageScore!

function score(player) {

sum = 0;

for (i = 0, n = player.levels.length; i < n; i++) {

sum += player.levels[i].score;

}

return sum;

}

The answer is to keep such variables local to just the portion of code that needs them:

function averageScore(players) {

var i, n, sum;

sum = 0;

for (i = 0, n = players.length; i < n; i++) {

sum += score(players[i]);

}

return sum / n;

}

function score(player) {

var i, n, sum;

sum = 0;

for (i = 0, n = player.levels.length; i < n; i++) {

sum += player.levels[i].score;

}

return sum;

}

JavaScript’s global namespace is also exposed as a global object, which is accessible at the top of a program as the initial value of the this keyword. In web browsers, the global object is also bound to the global window variable. Adding or modifying global variables automatically updates the global object:

this.foo; // undefined

foo = "global foo";

this.foo; // "global foo"

Similarly, updating the global object automatically updates the global namespace:

var foo = "global foo";

this.foo = "changed";

foo; // "changed"

This means that you have two mechanisms to choose from for creating a global variable: You can declare it with var in the global scope, or you can add it to the global object. Either works, but the var declaration has the benefit of more clearly conveying the effect on the program’s scope. Given that a reference to an unbound variable results in a runtime error, making scope clear and simple makes it easier for users of your code to understand what globals it declares.

While it’s best to limit your use of the global object, it does provide one particularly indispensable use. Since the global object provides a dynamic reflection of the global environment, you can use it to query a running environment to detect which features are available on the platform. For example, ES5 introduced a new global JSON object for reading and writing the JSON data format. As a stopgap for deploying code in environments that may or may not have yet provided the JSON object, you can test the global object for its presence and provide an alternate implementation:

if (!this.JSON) {

this.JSON = {

parse: ...,

stringify: ...

};

}

If you are already providing an implementation of JSON, you could of course simply use your own implementation unconditionally. But built-in implementations provided by the host environment are almost always preferable: They are highly tested for correctness and conformance to standards, and quite often provide better performance than a third-party implementation.

The technique of feature detection is especially important in web browsers, where the same code may be executed by a wide variety of browsers and browser versions. Feature detection is a relatively easy way to make programs robust to the variations in platform feature sets. The technique applies elsewhere, too, such as for sharing libraries that may work both in the browser and in JavaScript server environments.

Things to Remember

• Avoid declaring global variables.

• Declare variables as locally as possible.

• Avoid adding properties to the global object.

• Use the global object for platform feature detection.

Item 9: Always Declare Local Variables

If there’s one thing more troublesome than a global variable, it’s an unintentional global variable. Unfortunately, JavaScript’s variable assignment rules make it all too easy to create global variables accidentally. Instead of raising an error, a program that assigns to an unbound variable simply creates a new global variable and assigns to it. This means that forgetting to declare a local variable silently turns it into a global variable:

function swap(a, i, j) {

temp = a[i]; // global

a[i] = a[j];

a[j] = temp;

}

This program manages to execute without error, even though the lack of a var declaration for the temp variable leads to the accidental creation of a global variable. A proper implementation declares temp with var:

function swap(a, i, j) {

var temp = a[i];

a[i] = a[j];

a[j] = temp;

}

Purposefully creating global variables is bad style, but accidentally creating global variables can be a downright disaster. Because of this, many programmers use lint tools, which inspect your program’s source code for bad style or potential bugs, and often feature the ability to report uses of unbound variables. Typically, a lint tool that checks for undeclared variables takes a user-provided set of known globals (such as those expected to exist in the host environment, or globals defined in separate files) and then reports any references or assignments to variables that are neither provided in the list nor declared in the program. It’s worth taking some time to explore what development tools are available for JavaScript. Integrating automated checks for common errors such as accidental globals into your development process can be a lifesaver.

Things to Remember

• Always declare new local variables with var.

• Consider using lint tools to help check for unbound variables.

Item 10: Avoid with

Poor with. There is probably no single more maligned feature in JavaScript. Nevertheless, with came by its notoriety honestly: Whatever conveniences it may offer, it more than makes up for them in unreliability and inefficiency.

The motivations for with are understandable. Programs often need to call a number of methods in sequence on a single object, and it is convenient to avoid repeated references to the object:

function status(info) {

var widget = new Widget();

with (widget) {

setBackground("blue");

setForeground("white");

setText("Status: " + info); // ambiguous reference

show();

}

}

It’s also tempting to use with to “import” variables from objects serving as modules:

function f(x, y) {

with (Math) {

return min(round(x), sqrt(y)); // ambiguous references

}

}

In both cases, with makes it temptingly easy to extract the properties of an object and bind them as local variables in the block.

These examples look appealing. But neither actually does what it’s supposed to. Notice how both examples have two different kinds of variables: those that we expect to refer to properties of the with object, such as setBackground, round, and sqrt, and those that we expect to refer to outer variable bindings, such as info, x, and y. But nothing in the syntax actually distinguishes these two types of variables—they all just look like variables.

In fact, JavaScript treats all variables the same: It looks them up in scope, starting with the innermost scope and working its way outward. The with statement treats an object as if it represented a variable scope, so inside the with block, variable lookup starts by searching for a property of the given variable name. If the property is not found in the object, then the search continues in outer scopes.

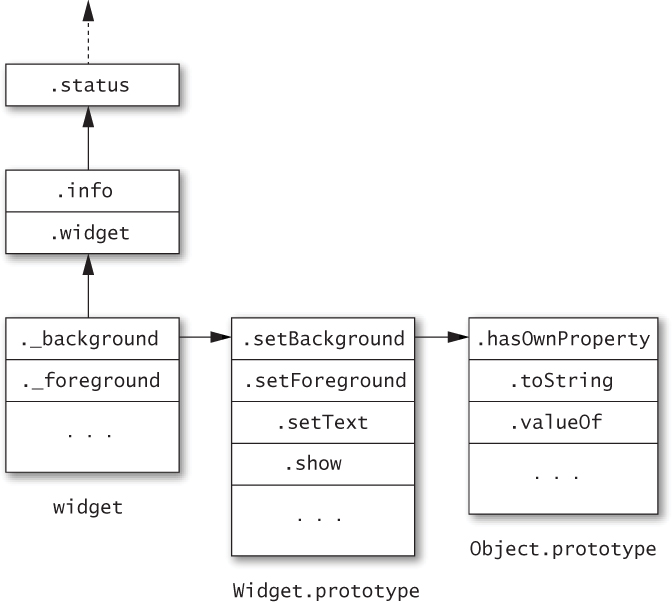

Figure 2.1 shows a diagram of a JavaScript engine’s internal representation of the scope of the status function while executing the body of its with statement. This is known in the ES5 specification as the lexical environment (or scope chain in older versions of the standard). The innermost scope of the environment is provided by the widget object. The next scope out has bindings for the function’s local variables info and widget. At the next level is a binding for the status function. Notice how, in a normal scope, there are exactly as many bindings stored in that level of the environment as there are variables in that local scope. But for the with scope, the set of bindings is dependent on whatever happens to be in the object at a given point in time.

Figure 2.1. Lexical environment (or “scope chain”) for the status function

How confident are we that we know what properties will or won’t be found on the object we provided to with? Every reference to an outer variable in a with block implicitly assumes that there is no property of the same name in the with object—or in any of its prototype objects. Other parts of the program that create or modify the with object and its prototypes may not share those assumptions. They certainly should not have to read your local code to find what local variables you happen to be using.

This conflict between variable scope and object namespaces makes with blocks extremely brittle. For example, if the widget object in the above example acquires an info property, then suddenly the behavior of the status function will use that property instead of the status function’s info parameter. This could happen during the evolution of the source code if, for example, a programmer decides that all widgets should have an info property. Worse, something could add an info property to the Widget prototype object at runtime, causing the status function to start breaking at unpredictable points:

status("connecting"); // Status: connecting

Widget.prototype.info = "[[widget info]]";

status("connected"); // Status: [[widget info]]

Similarly, the function f above could be broken if someone adds an x or y property to the Math object:

Math.x = 0;

Math.y = 0;

f(2, 9); // 0

It might be unlikely that anyone would add x and y properties to Math. But it’s not always easy to predict whether a particular object might be modified, or might have properties you didn’t know about. And as it turns out, a feature that is unpredictable for humans can also be unpredictable for optimizing compilers. Normally, JavaScript scopes can be represented with efficient internal data structures and variable lookups can be performed quickly. But because a with block requires searching an object’s prototype chain for all variables in its body, it will typically run much more slowly than an ordinary block.

There is no single feature of JavaScript that directly replaces with as a better alternative. In some cases, the best alternative is simply to bind an object to a short variable name:

function status(info) {

var w = new Widget();

w.setBackground("blue");

w.setForeground("white");

w.addText("Status: " + info);

w.show();

}

The behavior of this version is much more predictable. None of the variable references are sensitive to the contents of the object w. So even if some code modifies the Widget prototype, status continues to behave as expected:

status("connecting"); // Status: connecting

Widget.prototype.info = "[[widget info]]";

status("connected"); // Status: connected

In other cases, the best approach is to bind local variables explicitly to the relevant properties:

function f(x, y) {

var min = Math.min, round = Math.round, sqrt = Math.sqrt;

return min(round(x), sqrt(y));

}

Again, once we eliminate with, the function’s behavior becomes predictable:

Math.x = 0;

Math.y = 0;

f(2, 9); // 2

Things to Remember

• Avoid using with statements.

• Use short variable names for repeated access to an object.

• Explicitly bind local variables to object properties instead of implicitly binding them with a with statement.

Item 11: Get Comfortable with Closures

Closures may be an unfamiliar concept to programmers coming from languages that don’t support them. And they may seem intimidating at first. But rest assured that making the effort to master closures will pay for itself many times over.

Luckily, there’s really nothing to be afraid of. Understanding closures only requires learning three essential facts. The first fact is that JavaScript allows you to refer to variables that were defined outside of the current function:

function makeSandwich() {

var magicIngredient = "peanut butter";

function make(filling) {

return magicIngredient + " and " + filling;

}

return make("jelly");

}

makeSandwich(); // "peanut butter and jelly"

Notice how the inner make function refers to magicIngredient, a variable defined in the outer makeSandwich function.

The second fact is that functions can refer to variables defined in outer functions even after those outer functions have returned! If that sounds implausible, remember that JavaScript functions are first-class objects (see Item 19). That means that you can return an inner function to be called sometime later on:

function sandwichMaker() {

var magicIngredient = "peanut butter";

function make(filling) {

return magicIngredient + " and " + filling;

}

return make;

}

var f = sandwichMaker();

f("jelly"); // "peanut butter and jelly"

f("bananas"); // "peanut butter and bananas"

f("marshmallows"); // "peanut butter and marshmallows"

This is almost identical to the first example, except that instead of immediately calling make("jelly") inside the outer function, sandwichMaker returns the make function itself. So the value of f is the inner make function, and calling f effectively calls make. But somehow, even though sandwichMaker already returned, make remembers the value of magicIngredient.

How does this work? The answer is that JavaScript function values contain more information than just the code required to execute when they’re called. They also internally store any variables they may refer to that are defined in their enclosing scopes. Functions that keep track of variables from their containing scopes are known as closures. The make function is a closure whose code refers to two outer variables: magicIngredient and filling. Whenever the make function is called, its code is able to refer to these two variables because they are stored in the closure.

A function can refer to any variables in its scope, including the parameters and variables of outer functions. We can use this to make a more general-purpose sandwichMaker:

function sandwichMaker(magicIngredient) {

function make(filling) {

return magicIngredient + " and " + filling;

}

return make;

}

var hamAnd = sandwichMaker("ham");

hamAnd("cheese"); // "ham and cheese"

hamAnd("mustard"); // "ham and mustard"

var turkeyAnd = sandwichMaker("turkey");

turkeyAnd("Swiss"); // "turkey and Swiss"

turkeyAnd("Provolone"); // "turkey and Provolone"

This example creates two distinct functions, hamAnd and turkeyAnd. Even though they both come from the same make definition, they are two distinct objects: The first function stores "ham" as the value of magicIngredient, and the second stores "turkey".

Closures are one of JavaScript’s most elegant and expressive features, and are at the heart of many useful idioms. JavaScript even provides a more convenient literal syntax for constructing closures, the function expression:

function sandwichMaker(magicIngredient) {

return function(filling) {

return magicIngredient + " and " + filling;

};

}

Notice that this function expression is anonymous: It’s not even necessary to name the function since we are only evaluating it to produce a new function value, but do not intend to call it locally. Function expressions can have names as well (see Item 14).

The third and final fact to learn about closures is that they can update the values of outer variables. Closures actually store references to their outer variables, rather than copying their values. So updates are visible to any closures that have access to them. A simple idiom that illustrates this is a box—an object that stores an internal value that can be read and updated:

function box() {

var val = undefined;

return {

set: function(newVal) { val = newVal; },

get: function() { return val; },

type: function() { return typeof val; }

};

}

var b = box();

b.type(); // "undefined"

b.set(98.6);

b.get(); // 98.6

b.type(); // "number"

This example produces an object containing three closures: its set, get, and type properties. Each of these closures shares access to the val variable. The set closure updates the value of val, and subsequently calling get and type sees the results of the update.

Things to Remember

• Functions can refer to variables defined in outer scopes.

• Closures can outlive the function that creates them.

• Closures internally store references to their outer variables, and can both read and update their stored variables.

Item 12: Understand Variable Hoisting

JavaScript supports lexical scoping: With only a few exceptions, a reference to a variable foo is bound to the nearest scope in which foo was declared. However, JavaScript does not support block scoping: Variable definitions are not scoped to their nearest enclosing statement or block, but rather to their containing function.

Failing to understand this idiosyncrasy of JavaScript can lead to subtle bugs such as this:

function isWinner(player, others) {

var highest = 0;

for (var i = 0, n = others.length; i < n; i++) {

var player = others[i];

if (player.score > highest) {

highest = player.score;

}

}

return player.score > highest;

}

This program appears to declare a local variable player within the body of a for loop. But because JavaScript variables are function-scoped rather than block-scoped, the inner declaration of player simply redeclares a variable that was already in scope—namely, the player parameter. Each iteration of the loop then overwrites the same variable. As a result, the return statement sees player as the last element of others instead of the function’s original player argument.

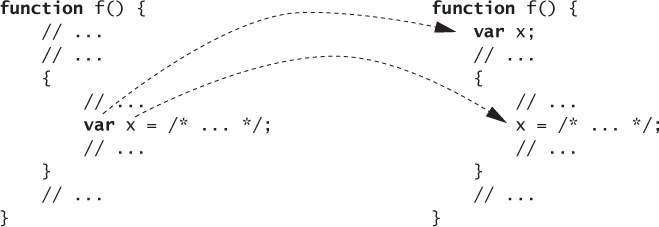

A good way to think about the behavior of JavaScript variable declarations is to understand them as consisting of two parts: a declaration and an assignment. JavaScript implicitly “hoists” the declaration part to the top of the enclosing function and leaves the assignment in place. In other words, the variable is in scope for the entire function, but it is only assigned at the point where the var statement appears. Figure 2.2 provides a visualization of hoisting.

Figure 2.2. Variable hoisting

Hoisting can also lead to confusion about variable redeclaration. It is legal to declare the same variable multiple times within the same function. This often comes up when writing multiple loops:

function trimSections(header, body, footer) {

for (var i = 0, n = header.length; i < n; i++) {

header[i] = header[i].trim();

}

for (var i = 0, n = body.length; i < n; i++) {

body[i] = body[i].trim();

}

for (var i = 0, n = footer.length; i < n; i++) {

footer[i] = footer[i].trim();

}

}

The trimSections function appears to declare six local variables (three called i and three called n), but hoisting results in only two. In other words, after hoisting, the trimSections function is equivalent to this rewritten version:

function trimSections(header, body, footer) {

var i, n;

for (i = 0, n = header.length; i < n; i++) {

header[i] = header[i].trim();

}

for (i = 0, n = body.length; i < n; i++) {

body[i] = body[i].trim();

}

for (i = 0, n = footer.length; i < n; i++) {

footer[i] = footer[i].trim();

}

}

Because redeclarations can lead to the appearance of distinct variables, some programmers prefer to place all var declarations at the top of their functions, effectively hoisting their variables manually, in order to avoid ambiguity. Regardless of whether you prefer this style, it’s important to understand the scoping rules of JavaScript, both for writing and reading code.

The one exception to JavaScript’s lack of block scoping is, appropriately enough, exceptions. That is, try...catch binds a caught exception to a variable that is scoped just to the catch block:

function test() {

var x = "var", result = [];

result.push(x);

try {

throw "exception";

} catch (x) {

x = "catch";

}

result.push(x);

return result;

}

test(); // ["var", "var"]

Things to Remember

• Variable declarations within a block are implicitly hoisted to the top of their enclosing function.

• Redeclarations of a variable are treated as a single variable.

• Consider manually hoisting local variable declarations to avoid confusion.

Item 13: Use Immediately Invoked Function Expressions to Create Local Scopes

What does this (buggy!) program compute?

function wrapElements(a) {

var result = [], i, n;

for (i = 0, n = a.length; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = function() { return a[i]; };

}

return result;

}

var wrapped = wrapElements([10, 20, 30, 40, 50]);

var f = wrapped[0];

f(); // ?

The programmer may have intended for it to produce 10, but it actually produces the undefined value.

The way to make sense of this example is to understand the distinction between binding and assignment. Entering a scope at runtime allocates a “slot” in memory for each variable binding in that scope. The wrapElements function binds three local variables: result, i, and n. So when it is called, wrapElements allocates slots for these three variables. On each iteration of the loop, the loop body allocates a closure for the nested function. The bug in the program comes from the fact that the programmer apparently expected the function to store the value of i at the time the nested function was created. But in fact, it contains a reference to i. Since the value of i changes after each function is created, the inner functions end up seeing the final value of i. This is the key point about closures:

Closures store their outer variables by reference, not by value.

So all the closures created by wrapElements refer to the single shared slot for i that was created before the loop. Since each iteration of the loop increments i until it runs off the end of the array, by the time we actually call one of the closures, it looks up index 5 of the array and returns undefined.

Notice that wrapElements would behave exactly the same even if we put the var declarations in the head of the for loop:

function wrapElements(a) {

var result = [];

for (var i = 0, n = a.length; i < n; i++) {

result[i] = function() { return a[i]; };

}

return result;

}

var wrapped = wrapElements([10, 20, 30, 40, 50]);

var f = wrapped[0];

f(); // undefined

This version looks even a bit more deceptive, because the var declaration appears to be inside the loop. But as always, the variable declarations are hoisted to the top of the loop. So once again, there is only a single slot allocated for the variable i.

The solution is to force the creation of a local scope by creating a nested function and calling it right away:

function wrapElements(a) {

var result = [];

for (var i = 0, n = a.length; i < n; i++) {

(function() {

var j = i;

result[i] = function() { return a[j]; };

})();

}

return result;

}

This technique, known as the immediately invoked function expression, or IIFE (pronounced “iffy”), is an indispensable workaround for JavaScript’s lack of block scoping. An alternate variation is to bind the local variable as a parameter to the IIFE and pass its value as an argument:

function wrapElements(a) {

var result = [];

for (var i = 0, n = a.length; i < n; i++) {

(function(j) {

result[i] = function() { return a[j]; };

})(i);

}

return result;

}

However, be careful when using an IIFE to create a local scope, because wrapping a block in a function can introduce some subtle changes to the block. First of all, the block cannot contain any break or continue statements that jump outside of the block, since it is illegal to break or continue outside of a function. Second, if the block refers to this or the special arguments variable, the IIFE changes their meaning. Chapter 3 discusses techniques for working with this and arguments.

Things to Remember

• Understand the difference between binding and assignment.

• Closures capture their outer variables by reference, not by value.

• Use immediately invoked function expressions (IIFEs) to create local scopes.

• Be aware of the cases where wrapping a block in an IIFE can change its behavior.

Item 14: Beware of Unportable Scoping of Named Function Expressions

JavaScript functions may look the same wherever they go, but their meaning changes depending on the context. Take a code snippet such as the following:

function double(x) { return x * 2; }

Depending on where it appears, this could be either a function declaration or a named function expression. A declaration is familiar: It defines a function and binds it to a variable in the current scope. At the top level of a program, for example, the above declaration would create a global function called double. But the same function code can be used as an expression, where it has a very different meaning. For example:

var f = function double(x) { return x * 2; };

According to the ECMAScript specification, this binds the function to a variable f rather than double. Of course, we don’t have to give a function expression a name. We could use the anonymous function expression form:

var f = function(x) { return x * 2; };

The official difference between anonymous and named function expressions is that the latter binds its name as a local variable within the function. This can be used to write recursive function expressions:

var f = function find(tree, key) {

if (!tree) {

return null;

}

if (tree.key === key) {

return tree.value;

}

return find(tree.left, key) ||

find(tree.right, key);

};

Note that find is only in scope within the function itself. Unlike a function declaration, a named function expression can’t be referred to externally by its internal name:

find(myTree, "foo"); // error: find is not defined

Using named function expressions for recursion may not seem particularly useful, since it’s fine to use the outer scope’s name for the function:

var f = function(tree, key) {

if (!tree) {

return null;

}

if (tree.key === key) {

return tree.value;

}

return f(tree.left, key) ||

f(tree.right, key);

};

Or we could just use a declaration:

function find(tree, key) {

if (!tree) {

return null;

}

if (tree.key === key) {

return tree.value;

}

return find(tree.left, key) ||

find(tree.right, key);

}

var f = find;

The real usefulness of named function expressions, though, is for debugging. Most modern JavaScript environments produce stack traces for Error objects, and the name of a function expression is typically used for its entry in a stack trace. Debuggers with facilities for inspecting the stack typically make similar use of named function expressions.

Sadly, named function expressions have been a notorious source of scoping and compatibility issues, due to a combination of an unfortunate mistake in the history of the ECMAScript specification and bugs in popular JavaScript engines. The specification mistake, which existed through ES3, was that JavaScript engines were required to represent the scope of a named function expression as an object, much like the problematic with construct. While this scope object only contains a single property binding the function’s name to the function, it also inherits properties from Object.prototype. This means that just naming a function expression also brings all of the properties of Object.prototype into scope. The results can be surprising:

var constructor = function() { return null; };

var f = function f() {

return constructor();

};

f(); // {} (in ES3 environments)

This program looks like it should produce null, but it actually produces a new object, because the named function expression inherits Object.prototype.constructor (i.e., the Object constructor function) in its scope. And just like with, the scope is affected by dynamic changes to Object.prototype. One part of a program could add or delete properties to Object.prototype and variables within named function expressions everywhere would be affected.

Thankfully, ES5 corrected this mistake. But some JavaScript environments continue to use the obsolete object scoping. Worse, some are even less standards-compliant and use objects as scopes even for anonymous function expressions! Then, even removing the function expression’s name in the preceding example produces an object instead of the expected null:

var constructor = function() { return null; };

var f = function() {

return constructor();

};

f(); // {} (in nonconformant environments)

The best way to avoid these problems on systems that pollute their function expressions’ scopes with objects is to avoid ever adding new properties to Object.prototype and avoid using local variables with any of the names of the standard Object.prototype properties.

The next bug seen in popular JavaScript engines is hoisting named function expressions as if they were declarations. For example:

var f = function g() { return 17; };

g(); // 17 (in nonconformant environments)

To be clear, this is not standards-compliant behavior. Worse, some JavaScript environments even treat the two functions f and g as distinct objects, leading to unnecessary memory allocation! A reasonable workaround for this behavior is to create a local variable of the same name as the function expression and assign it to null:

var f = function g() { return 17; };

var g = null;

Redeclaring the variable with var ensures that g is bound even in those environments that do not erroneously hoist the function expression, and setting it to null ensures that the duplicate function can be garbage-collected.

It would certainly be reasonable to conclude that named function expressions are just too problematic to be worth using. A less austere response would be to use named function expressions during development for debugging, and to run code through a preprocessor to anonymize all function expressions before shipping. But one thing is certain: You should always be clear about what platforms you are shipping on (see Item 1). The worst thing you could do is to litter your code with workarounds that aren’t even necessary for the platforms you support.

Things to Remember

• Use named function expressions to improve stack traces in Error objects and debuggers.

• Beware of pollution of function expression scope with Object.prototype in ES3 and buggy JavaScript environments.

• Beware of hoisting and duplicate allocation of named function expressions in buggy JavaScript environments.

• Consider avoiding named function expressions or removing them before shipping.

• If you are shipping in properly implemented ES5 environments, you’ve got nothing to worry about.

Item 15: Beware of Unportable Scoping of Block-Local Function Declarations

The saga of context sensitivity continues with nested function declarations. It may surprise you to know that there is no standard way to declare functions inside a local block. Now, it’s perfectly legal and customary to nest a function declaration at the top of another function:

function f() { return "global"; }

function test(x) {

function f() { return "local"; }

var result = [];

if (x) {

result.push(f());

}

result.push(f());

return result;

}

test(true); // ["local", "local"]

test(false); // ["local"]

But it’s an entirely different story if we move f into a local block:

function f() { return "global"; }

function test(x) {

var result = [];

if (x) {

function f() { return "local"; } // block-local

result.push(f());

}

result.push(f());

return result;

}

test(true); // ?

test(false); // ?

You might expect the first call to test to produce the array ["local", "global"] and the second to produce ["global"], since the inner f appears to be local to the if block. But recall that JavaScript is not block-scoped, so the inner f should be in scope for the whole body of test. A reasonable second guess would be ["local", "local"] and ["local"]. And in fact, some JavaScript environments behave this way. But not all of them! Others conditionally bind the inner f at runtime, based on whether its enclosing block is executed. (Not only does this make code harder to understand, but it also leads to slow performance, not unlike with statements.)

What does the ECMAScript standard have to say about this state of affairs? Surprisingly, almost nothing. Until ES5, the standard did not even acknowledge the existence of block-local function declarations; function declarations are officially specified to appear only at the outermost level of other functions or of a program. ES5 even recommends turning function declarations in nonstandard contexts into a warning or error, and popular JavaScript implementations report them as an error in strict mode—a strict-mode program with a block-local function declaration will report a syntax error. This helps detect unportable code, and it clears a path for future versions of the standard to specify more sensible and portable semantics for block-local declarations.

In the meantime, the best way to write portable functions is to avoid ever putting function declarations in local blocks or substatements. If you want to write a nested function declaration, put it at the outermost level of its parent function, as shown in the original version of the code. If, on the other hand, you need to choose between functions conditionally, the best way to do this is with var declarations and function expressions:

function f() { return "global"; }

function test(x) {

var g = f, result = [];

if (x) {

g = function() { return "local"; }

result.push(g());

}

result.push(g());

return result;

}

This eliminates the mystery of the scoping of the inner variable (renamed here to g): It is unconditionally bound as a local variable, and only the assignment is conditional. The result is unambiguous and fully portable.

Things to Remember

• Always keep function declarations at the outermost level of a program or a containing function to avoid unportable behavior.

• Use var declarations with conditional assignment instead of conditional function declarations.

Item 16: Avoid Creating Local Variables with eval

JavaScript’s eval function is an incredibly powerful and flexible tool. Powerful tools are easy to abuse, so they’re worth understanding. One of the simplest ways to run afoul of eval is to allow it to interfere with scope.

Calling eval interprets its argument as a JavaScript program, but that program runs in the local scope of the caller. The global variables of the embedded program get created as locals of the calling program:

function test(x) {

eval("var y = x;"); // dynamic binding

return y;

}

test("hello"); // "hello"

This example looks clear, but it behaves subtly differently than the var declaration would behave if it were directly included in the body of test. The var declaration is only executed when the eval function is called. Placing an eval in a conditional context brings its variables into scope only if the conditional is executed:

var y = "global";

function test(x) {

if (x) {

eval("var y = 'local';"); // dynamic binding

}

return y;

}

test(true); // "local"

test(false); // "global"

Basing scoping decisions on the dynamic behavior of a program is almost always a bad idea. The result is that simply understanding which binding a variable refers to requires following the details of how the program executes. This is especially tricky when the source code passed to eval is not even defined locally:

var y = "global";

function test(src) {

eval(src); // may dynamically bind

return y;

}

test("var y = 'local';"); // "local"

test("var z = 'local';"); // "global"

This code is brittle and unsafe: It gives external callers the power to change the internal scoping of the test function. Expecting eval to modify its containing scope is also not safe for compatibility with ES5 strict mode, which runs eval in a nested scope to prevent this kind of pollution. A simple way to ensure that eval does not affect outer scopes is to run it in an explicitly nested scope:

var y = "global";

function test(src) {

(function() { eval(src); })();

return y;

}

test("var y = 'local';"); // "global"

test("var z = 'local';"); // "global"

Things to Remember

• Avoid creating variables with eval that pollute the caller’s scope.

• If eval code might create global variables, wrap the call in a nested function to prevent scope pollution.

Item 17: Prefer Indirect eval to Direct eval

The eval function has a secret weapon: It’s more than just a function.

Most functions have access to the scope where they are defined, and nothing else. But eval has access to the full scope at the point where it’s called. This is such immense power that when compiler writers first tried to optimize JavaScript, they discovered that eval made it difficult to make any function calls efficient, since every function call needed to make its scope available at runtime in case the function turned out to be eval.

As a compromise, the language standard evolved to distinguish two different ways of calling eval. A function call involving the identifier eval is considered a “direct” call to eval:

var x = "global";

function test() {

var x = "local";

return eval("x"); // direct eval

}

test(); // "local"

In this case, compilers are required to ensure that the executed program has complete access to the local scope of the caller. The other kind of call to eval is considered “indirect,” and evaluates its argument in global scope. For example, binding the eval function to a different variable name and calling it through the alternate name causes the code to lose access to any local scope:

var x = "global";

function test() {

var x = "local";

var f = eval;

return f("x"); // indirect eval

}

test(); // "global"

The exact definition of direct eval depends on the rather idiosyncratic specification language of the ECMAScript standard. In practice, the only syntax that can produce a direct eval is a variable with the name eval, possibly surrounded by (any number of) parentheses. A concise way to write an indirect call to eval is to use the expression sequencing operator (,) with an apparently pointless number literal:

(0,eval)(src);

How does this peculiar-looking function call work? The number literal 0 is evaluated but its value is ignored, and the parenthesized sequence expression produces the eval function. So (0,eval) behaves almost exactly the same as the plain identifier eval, with the one important difference being that the whole call expression is treated as an indirect eval.

The power of direct eval can be easily abused. For example, evaluating a source string coming from over the network can expose internals to untrusted parties. Item 16 talks about the dangers of eval dynamically creating local variables; these dangers are only possible with direct eval. Moreover, direct eval costs dearly in performance. In general, you should assume that direct eval causes its containing function and all containing functions up to the outermost level of the program to be considerably slower.

There are occasionally reasons to use direct eval. But unless there’s a clear need for the extra power of inspecting local scope, use the less easily abused and less expensive indirect eval.

Things to Remember

• Wrap eval in a sequence expression with a useless literal to force the use of indirect eval.

• Prefer indirect eval to direct eval whenever possible.