1. Accustoming Yourself to JavaScript

JavaScript was designed to feel familiar. With syntax reminiscent of Java and constructs common to many scripting languages (such as functions, arrays, dictionaries, and regular expressions), JavaScript seems like a quick learn to anyone with a little programming experience. And for novice programmers, it’s possible to get started writing programs with relatively little training thanks to the small number of core concepts in the language.

As approachable as JavaScript is, mastering the language takes more time, and requires a deeper understanding of its semantics, its idiosyncrasies, and its most effective idioms. Each chapter of this book covers a different thematic area of effective JavaScript. This first chapter begins with some of the most fundamental topics.

Item 1: Know Which JavaScript You Are Using

Like most successful technologies, JavaScript has evolved over time. Originally marketed as a complement to Java for programming interactive web pages, JavaScript eventually supplanted Java as the web’s dominant programming language. JavaScript’s popularity led to its formalization in 1997 as an international standard, known officially as ECMAScript. Today there are many competing implementations of JavaScript providing conformance to various versions of the ECMA-Script standard.

The third edition of the ECMAScript standard (commonly referred to as ES3), which was finalized in 1999, continues to be the most widely adopted version of JavaScript. The next major advancement to the standard was Edition 5, or ES5, which was released in 2009. ES5 introduced a number of new features as well as standardizing some widely supported but previously unspecified features. Because ES5 support is not yet ubiquitous, I will point out throughout this book whenever a particular Item or piece of advice is specific to ES5.

In addition to multiple editions of the standard, there are a number of nonstandard features that are supported by some JavaScript implementations but not others. For example, many JavaScript engines support a const keyword for defining variables, yet the ECMAScript standard does not provide any definition for the syntax or behavior of const. Moreover, the behavior of const differs from implementation to implementation. In some cases, const variables are prevented from being updated:

const PI = 3.141592653589793;

PI = "modified!";

PI; // 3.141592653589793

Other implementations simply treat const as a synonym for var:

const PI = 3.141592653589793;

PI = "modified!";

PI; // "modified!"

Given JavaScript’s long history and diversity of implementations, it can be difficult to keep track of which features are available on which platform. Compounding this problem is the fact that JavaScript’s primary ecosystem—the web browser—does not give programmers control over which version of JavaScript is available to execute their code. Since end users may use different versions of different web browsers, web programs have to be written carefully to work consistently across all browsers.

On the other hand, JavaScript is not exclusively used for client-side web programming. Other uses include server-side programs, browser extensions, and scripting for mobile and desktop applications. In some of these cases, you may have a much more specific version of JavaScript available to you. For these cases, it makes sense to take advantage of additional features specific to the platform’s particular implementation of JavaScript.

This book is concerned primarily with standard features of JavaScript. But it is also important to discuss certain widely supported but nonstandard features. When dealing with newer standards or nonstandard features, it is critical to understand whether your applications will run in environments that support those features. Otherwise, you may find yourself in situations where your applications work as intended on your own computer or testing infrastructure, but fail when you deploy them to users running your application in different environments. For example, const may work fine when tested on an engine that supports the nonstandard feature but then fail with a syntax error when deployed in a web browser that does not recognize the keyword.

ES5 introduced another versioning consideration with its strict mode. This feature allows you to opt in to a restricted version of JavaScript that disallows some of the more problematic or error-prone features of the full language. The syntax was designed to be backward-compatible so that environments that do not implement the strict-mode checks can still execute strict code. Strict mode is enabled in a program by adding a special string constant at the very beginning of the program:

"use strict";

Similarly, you can enable strict mode in a function by placing the directive at the beginning of the function body:

function f(x) {

"use strict";

// ...

}

The use of a string literal for the directive syntax looks a little strange, but it has the benefit of backward compatibility: Evaluating a string literal has no side effects, so an ES3 engine executes the directive as an innocuous statement—it evaluates the string and then discards its value immediately. This makes it possible to write code in strict mode that runs in older JavaScript engines, but with a crucial limitation: The old engines will not perform any of the checks of strict mode. If you don’t test in an ES5 environment, it’s all too easy to write code that will be rejected when run in an ES5 environment:

function f(x) {

"use strict";

var arguments = []; // error: redefinition of arguments

// ...

}

Redefining the arguments variable is disallowed in strict mode, but an environment that does not implement the strict-mode checks will accept this code. Deploying this code in production would then cause the program to fail in environments that implement ES5. For this reason you should always test strict code in fully compliant ES5 environments.

One pitfall of using strict mode is that the "use strict" directive is only recognized at the top of a script or function, which makes it sensitive to script concatenation, where large applications are developed in separate files that are then combined into a single file for deploying in production. Consider one file that expects to be in strict mode:

// file1.js

"use strict";

function f() {

// ...

}

// ...

and another file that expects not to be in strict mode:

// file2.js

// no strict-mode directive

function g() {

var arguments = [];

// ...

}

// ...

How can we concatenate these two files correctly? If we start with file1.js, then the whole combined file is in strict mode:

// file1.js

"use strict";

function f() {

// ...

}

// ...

// file2.js

// no strict-mode directive

function f() {

var arguments = []; // error: redefinition of arguments

// ...

}

// ...

And if we start with file2.js, then none of the combined file is in strict mode:

// file2.js

// no strict-mode directive

function g() {

var arguments = [];

// ...

}

// ...

// file1.js

"use strict";

function f() { // no longer strict

// ...

}

// ...

In your own projects, you could stick to a “strict-mode only” or “nonstrict-mode only” policy, but if you want to write robust code that can be combined with a wide variety of code, you have a few alternatives.

Never concatenate strict files and nonstrict files. This is probably the easiest solution, but it of course restricts the amount of control you have over the file structure of your application or library. At best, you have to deploy two separate files, one containing all the strict files and one containing the nonstrict files.

Concatenate files by wrapping their bodies in immediately invoked function expressions. Item 13 provides an in-depth explanation of immediately invoked function expressions (IIFEs), but in short, by wrapping each file’s contents in a function, they can be independently interpreted in different modes. The concatenated version of the above example would look like this:

// no strict-mode directive

(function() {

// file1.js

"use strict";

function f() {

// ...

}

// ...

})();

(function() {

// file2.js

// no strict-mode directive

function f() {

var arguments = [];

// ...

}

// ...

})();

Since each file’s contents are placed in a separate scope, the strict-mode directive (or lack of one) only affects that file’s contents. For this approach to work, however, the contents of files cannot assume that they are interpreted at global scope. For example, var and function declarations do not persist as global variables (see Item 8 for more on globals). This happens to be the case with popular module systems, which manage files and dependencies by automatically placing each module’s contents in a separate function. Since files are all placed in local scopes, each file can make its own decision about whether to use strict mode.

Write your files so that they behave the same in either mode. To write a library that works in as many contexts as possible, you cannot assume that it will be placed inside the contents of a function by a script concatenation tool, nor can you assume whether the client codebase will be strict or nonstrict. The simplest way to structure your code for maximum compatibility is to write for strict mode but explicitly wrap the contents of all your code in functions that enable strict mode locally. This is similar to the previous solution, in that you wrap each file’s contents in an IIFE, but in this case you write the IIFE by hand instead of trusting the concatenation tool or module system to do it for you, and explicitly opt in to strict mode:

(function() {

"use strict";

function f() {

// ...

}

// ...

})();

Notice that this code is treated as strict regardless of whether it is concatenated in a strict or nonstrict context. By contrast, a function that does not opt in to strict mode will still be treated as strict if it is concatenated after strict code. So the more universally compatible option is to write in strict mode.

Things to Remember

• Decide which versions of JavaScript your application supports.

• Be sure that any JavaScript features you use are supported by all environments where your application runs.

• Always test strict code in environments that perform the strict-mode checks.

• Beware of concatenating scripts that differ in their expectations about strict mode.

Item 2: Understand JavaScript’s Floating-Point Numbers

Most programming languages have several types of numeric data, but JavaScript gets away with just one. You can see this reflected in the behavior of the typeof operator, which classifies integers and floating-point numbers alike simply as numbers:

typeof 17; // "number"

typeof 98.6; // "number"

typeof -2.1; // "number"

In fact, all numbers in JavaScript are double-precision floating-point numbers, that is, the 64-bit encoding of numbers specified by the IEEE 754 standard—commonly known as “doubles.” If this fact leaves you wondering what happened to the integers, keep in mind that doubles can represent integers perfectly with up to 53 bits of precision. All of the integers from –9,007,199,254,740,992 (–253) to 9,007,199,254,740,992 (253) are valid doubles. So it’s perfectly possible to do integer arithmetic in JavaScript, despite the lack of a distinct integer type.

Most arithmetic operators work with integers, real numbers, or a combination of the two:

0.1 * 1.9 // 0.19

-99 + 100; // 1

21 - 12.3; // 8.7

2.5 / 5; // 0.5

21 % 8; // 5

The bitwise arithmetic operators, however, are special. Rather than operating on their arguments directly as floating-point numbers, they implicitly convert them to 32-bit integers. (To be precise, they are treated as 32-bit, big-endian, two’s complement integers.) For example, take the bitwise OR expression:

8 | 1; // 9

This simple-looking expression actually requires several steps to evaluate. As always, the JavaScript numbers 8 and 1 are doubles. But they can also be represented as 32-bit integers, that is, sequences of thirty-two 1’s and 0’s. As a 32-bit integer, the number 8 looks like this:

00000000000000000000000000001000

You can see this for yourself by using the toString method of numbers:

(8).toString(2); // "1000"

The argument to toString specifies the radix, in this case indicating a base 2 (i.e., binary) representation. The result drops the extra 0 bits on the left since they don’t affect the value.

The integer 1 is represented in 32 bits as:

00000000000000000000000000000001

The bitwise OR expression combines the two bit sequences by keeping any 1 bits found in either input, resulting in the bit pattern:

00000000000000000000000000001001

This sequence represents the integer 9. You can verify this by using the standard library function parseInt, again with a radix of 2:

parseInt("1001", 2); // 9

(The leading 0 bits are unnecessary since, again, they don’t affect the result.)

All of the bitwise operators work the same way, converting their inputs to integers and performing their operations on the integer bit patterns before converting the results back to standard JavaScript floating-point numbers. In general, these conversions require extra work in JavaScript engines: Since numbers are stored as floating-point, they have to be converted to integers and then back to floating-point again. However, optimizing compilers can sometimes infer when arithmetic expressions and even variables work exclusively with integers, and avoid the extra conversions by storing the data internally as integers.

A final note of caution about floating-point numbers: If they don’t make you at least a little nervous, they probably should. Floating-point numbers look deceptively familiar, but they are notoriously inaccurate. Even some of the simplest-looking arithmetic can produce inaccurate results:

0.1 + 0.2; // 0.30000000000000004

While 64 bits of precision is reasonably large, doubles can still only represent a finite set of numbers, rather than the infinite set of real numbers. Floating-point arithmetic can only produce approximate results, rounding to the nearest representable real number. When you perform a sequence of calculations, these rounding errors can accumulate, leading to less and less accurate results. Rounding also causes surprising deviations from the kind of properties we usually expect of arithmetic. For example, real numbers are associative, meaning that for any real numbers x, y, and z, it’s always the case that (x + y) + z = x + (y + z).

But this is not always true of floating-point numbers:

(0.1 + 0.2) + 0.3; // 0.6000000000000001

0.1 + (0.2 + 0.3); // 0.6

Floating-point numbers offer a trade-off between accuracy and performance. When accuracy matters, it’s critical to be aware of their limitations. One useful workaround is to work with integer values wherever possible, since they can be represented without rounding. When doing calculations with money, programmers often scale numbers up to work with the currency’s smallest denomination so that they can compute with whole numbers. For example, if the above calculation were measured in dollars, we could work with whole numbers of cents instead:

(10 + 20) + 30; // 60

10 + (20 + 30); // 60

With integers, you still have to take care that all calculations fit within the range between –253 and 253, but you don’t have to worry about rounding errors.

Things to Remember

• JavaScript numbers are double-precision floating-point numbers.

• Integers in JavaScript are just a subset of doubles rather than a separate datatype.

• Bitwise operators treat numbers as if they were 32-bit signed integers.

• Be aware of limitations of precisions in floating-point arithmetic.

Item 3: Beware of Implicit Coercions

JavaScript can be surprisingly forgiving when it comes to type errors. Many languages consider an expression like

3 + true; // 4

to be an error, because boolean expressions such as true are incompatible with arithmetic. In a statically typed language, a program with such an expression would not even be allowed to run. In some dynamically typed languages, while the program would run, such an expression would throw an exception. JavaScript not only allows the program to run, but it happily produces the result 4!

There are a handful of cases in JavaScript where providing the wrong type produces an immediate error, such as calling a nonfunction or attempting to select a property of null:

"hello"(1); // error: not a function

null.x; // error: cannot read property 'x' of null

But in many other cases, rather than raising an error, JavaScript coerces a value to the expected type by following various automatic conversion protocols. For example, the arithmetic operators -, *, /, and % all attempt to convert their arguments to numbers before doing their calculation. The operator + is subtler, because it is overloaded to perform either numeric addition or string concatenation, depending on the types of its arguments:

2 + 3; // 5

"hello" + " world"; // "hello world"

Now, what happens when you combine a number and a string? JavaScript breaks the tie in favor of strings, converting the number to a string:

"2" + 3; // "23"

2 + "3"; // "23"

Mixing types like this can sometimes be confusing, especially because it’s sensitive to the order of operations. Take the expression:

1 + 2 + "3"; // "33"

Since addition groups to the left (i.e., is left-associative), this is the same as:

(1 + 2) + "3"; // "33"

By contrast, the expression

1 + "2" + 3; // "123"

evaluates to the string "123"—again, left-associativity dictates that the expression is equivalent to wrapping the left-hand addition in parentheses:

(1 + "2") + 3; // "123"

The bitwise operations not only convert to numbers but to the subset of numbers that can be represented as 32-bit integers, as discussed in Item 2. These include the bitwise arithmetic operators (~, &, ^, and |) and the shift operators (<<, >>, and >>>).

These coercions can be seductively convenient—for example, for automatically converting strings that come from user input, a text file, or a network stream:

"17" * 3; // 51

"8" | "1"; // 9

But coercions can also hide errors. A variable that turns out to be null will not fail in an arithmetic calculation, but silently convert to 0; an undefined variable will convert to the special floating-point value NaN (the paradoxically named “not a number” number—blame the IEEE floating-point standard!). Rather than immediately throwing an exception, these coercions cause the calculation to continue with often confusing and unpredictable results. Frustratingly, it’s particularly difficult even to test for the NaN value, for two reasons. First, JavaScript follows the IEEE floating-point standard’s head-scratching requirement that NaN be treated as unequal to itself. So testing whether a value is equal to NaN doesn’t work at all:

var x = NaN;

x === NaN; // false

Moreover, the standard isNaN library function is not very reliable because it comes with its own implicit coercion, converting its argument to a number before testing the value. (A more accurate name for isNaN probably would have been coercesToNaN.) If you already know that a value is a number, you can test it for NaN with isNaN:

isNaN(NaN); // true

But other values that are definitely not NaN, yet are nevertheless coercible to NaN, are indistinguishable to isNaN:

isNaN("foo"); // true

isNaN(undefined); // true

isNaN({}); // true

isNaN({ valueOf: "foo" }); // true

Luckily there’s an idiom that is both reliable and concise—if somewhat unintuitive—for testing for NaN. Since NaN is the only JavaScript value that is treated as unequal to itself, you can always test if a value is NaN by checking it for equality to itself:

var a = NaN;

a !== a; // true

var b = "foo";

b !== b; // false

var c = undefined;

c !== c; // false

var d = {};

d !== d; // false

var e = { valueOf: "foo" };

e !== e; // false

You can also abstract this pattern into a clearly named utility function:

function isReallyNaN(x) {

return x !== x;

}

But testing a value for inequality to itself is so concise that it’s commonly used without a helper function, so it’s important to recognize and understand.

Silent coercions can make debugging a broken program particularly frustrating, since they cover up errors and make them harder to diagnose. When a calculation goes wrong, the best approach to debugging is to inspect the intermediate results of a calculation, working back to the last point before things went wrong. From there, you can inspect the arguments of each operation, looking for arguments of the wrong type. Depending on the bug, it could be a logical error, such as using the wrong arithmetic operator, or a type error, such as passing the undefined value instead of a number.

Objects can also be coerced to primitives. This is most commonly used for converting to strings:

"the Math object: " + Math; // "the Math object: [object Math]"

"the JSON object: " + JSON; // "the JSON object: [object JSON]"

Objects are converted to strings by implicitly calling their toString method. You can test this out by calling it yourself:

Math.toString(); // "[object Math]"

JSON.toString(); // "[object JSON]"

Similarly, objects can be converted to numbers via their valueOf method. You can control the type conversion of objects by defining these methods:

"J" + { toString: function() { return "S"; } }; // "JS"

2 * { valueOf: function() { return 3; } }; // 6

Once again, things get tricky when you consider that + is overloaded to perform both string concatenation and addition. Specifically, when an object contains both a toString and a valueOf method, it’s not obvious which method + should call: It’s supposed to choose between concatenation and addition based on types, but with implicit coercion, the types are not actually given! JavaScript resolves this ambiguity by blindly choosing valueOf over toString. But this means that if someone intends to perform a string concatenation with an object, it can behave unexpectedly:

var obj = {

toString: function() {

return "[object MyObject]";

},

valueOf: function() {

return 17;

}

};

"object: " + obj; // "object: 17"

The moral of this story is that valueOf was really only designed to be used for objects that represent numeric values such as Number objects. For these objects, the toString and valueOf methods return consistent results—a string representation or numeric representation of the same number—so the overloaded + always behaves consistently regardless of whether the object is used for concatenation or addition. In general, coercion to strings is far more common and useful than coercion to numbers. It’s best to avoid valueOf unless your object really is a numeric abstraction and obj.toString() produces a string representation of obj.valueOf().

The last kind of coercion is sometimes known as truthiness. Operators such as if, ||, and && logically work with boolean values, but actually accept any values. JavaScript values are interpreted as boolean values according to a simple implicit coercion. Most JavaScript values are truthy, that is, implicitly coerced to true. This includes all objects—unlike string and number coercion, truthiness does not involve implicitly invoking any coercion methods. There are exactly seven falsy values: false, 0, -0, "", NaN, null, and undefined. All other values are truthy. Since numbers and strings can be falsy, it’s not always safe to use truthiness to check whether a function argument or object property is defined. Consider a function that takes optional arguments with default values:

function point(x, y) {

if (!x) {

x = 320;

}

if (!y) {

y = 240;

}

return { x: x, y: y };

}

This function ignores any falsy arguments, which includes 0:

point(0, 0); // { x: 320, y: 240 }

The more precise way to check for undefined is to use typeof:

function point(x, y) {

if (typeof x === "undefined") {

x = 320;

}

if (typeof y === "undefined") {

y = 240;

}

return { x: x, y: y };

}

This version of point correctly distinguishes between 0 and undefined:

point(); // { x: 320, y: 240 }

point(0, 0); // { x: 0, y: 0 }

Another approach is to compare to undefined:

if (x === undefined) { ... }

Item 54 discusses the implications of truthiness testing for library and API design.

Things to Remember

• Type errors can be silently hidden by implicit coercions.

• The + operator is overloaded to do addition or string concatenation depending on its argument types.

• Objects are coerced to numbers via valueOf and to strings via toString.

• Objects with valueOf methods should implement a toString method that provides a string representation of the number produced by valueOf.

• Use typeof or comparison to undefined rather than truthiness to test for undefined values.

Item 4: Prefer Primitives to Object Wrappers

In addition to objects, JavaScript has five types of primitive values: booleans, numbers, strings, null, and undefined. (Confusingly, the typeof operator reports the type of null as "object", but the ECMA-Script standard describes it as a distinct type.) At the same time, the standard library provides constructors for wrapping booleans, numbers, and strings as objects. You can create a String object that wraps a string value:

var s = new String("hello");

In some ways, a String object behaves similarly to the string value it wraps. You can concatenate it with other values to create strings:

s + " world"; // "hello world"

You can extract its indexed substrings:

s[4]; // "o"

But unlike primitive strings, a String object is a true object:

typeof "hello"; // "string"

typeof s; // "object"

This is an important difference, because it means that you can’t compare the contents of two distinct String objects using built-in operators:

var s1 = new String("hello");

var s2 = new String("hello");

s1 === s2; // false

Since each String object is a separate object, it is only ever equal to itself. The same is true for the nonstrict equality operator:

s1 == s2; // false

Since these wrappers don’t behave quite right, they don’t serve much of a purpose. The main justification for their existence is their utility methods. JavaScript makes these convenient to use with another implicit coercion: You can extract properties and call methods of a primitive value, and it acts as though you had wrapped the value with its corresponding object type. For example, the String prototype object has a toUpperCase method, which converts a string to uppercase. You can use this method on a primitive string value:

"hello".toUpperCase(); // "HELLO"

A strange consequence of this implicit wrapping is that you can set properties on primitive values with essentially no effect:

"hello".someProperty = 17;

"hello".someProperty; // undefined

Since the implicit wrapping produces a new String object each time it occurs, the update to the first wrapper object has no lasting effect. There’s really no point to setting properties on primitive values, but it’s worth being aware of this behavior. It turns out to be another instance of where JavaScript can hide type errors: If you set properties on what you expect to be an object, but use a primitive value by mistake, your program will simply silently ignore the update and continue. This can easily cause the error to go undetected and make it harder to diagnose.

Things to Remember

• Object wrappers for primitive types do not have the same behavior as their primitive values when compared for equality.

• Getting and setting properties on primitives implicitly creates object wrappers.

Item 5: Avoid using == with Mixed Types

What would you expect to be the value of this expression?

"1.0e0" == { valueOf: function() { return true; } };

These two seemingly unrelated values are actually considered equivalent by the == operator because, like the implicit coercions described in Item 3, they are both converted to numbers before being compared. The string "1.0e0" parses as the number 1, and the object is converted to a number by calling its valueOf method and converting the result (true) to a number, which also produces 1.

It’s tempting to use these coercions for tasks like reading a field from a web form and comparing it with a number:

var today = new Date();

if (form.month.value == (today.getMonth() + 1) &&

form.day.value == today.getDate()) {

// happy birthday!

// ...

}

But it’s actually easy to convert values to numbers explicitly using the Number function or the unary + operator:

var today = new Date();

if (+form.month.value == (today.getMonth() + 1) &&

+form.day.value == today.getDate()) {

// happy birthday!

// ...

}

This is clearer, because it conveys to readers of your code exactly what conversion is being applied, without requiring them to memorize the conversion rules. An even better alternative is to use the strict equality operator:

var today = new Date();

if (+form.month.value === (today.getMonth() + 1) && // strict

+form.day.value === today.getDate()) { // strict

// happy birthday!

// ...

}

When the two arguments are of the same type, there’s no difference in behavior between == and ===. So if you know that the arguments are of the same type, they are interchangeable. But using strict equality is a good way to make it clear to readers that there is no conversion involved in the comparison. Otherwise, you require readers to recall the exact coercion rules to decipher your code’s behavior.

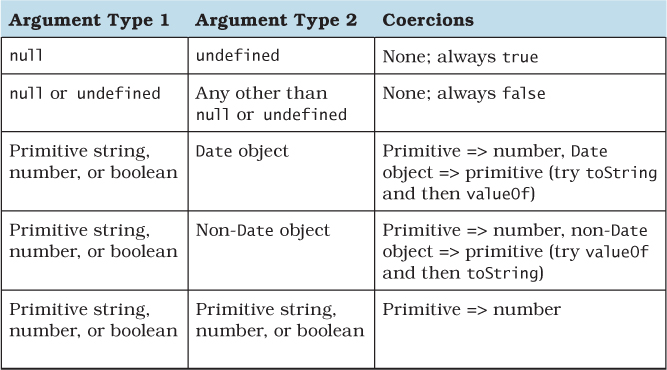

As it turns out, these coercion rules are not at all obvious. Table 1.1 contains the coercion rules for the == operator when its arguments are of different types. The rules are symmetric: For example, the first rule applies to both null == undefined and undefined == null. Most of the time, the conversions attempt to produce numbers. But the rules get subtle when they deal with objects. The operation tries to convert an object to a primitive value by calling its valueOf and toString methods, using the first primitive value it gets. Even more subtly, Date objects try these two methods in the opposite order.

Table 1.1. Coercion Rules for the == Operator

The == operator deceptively appears to paper over different representations of data. This kind of error correction is sometimes known as “do what I mean” semantics. But computers cannot really read your mind. There are too many data representations in the world for JavaScript to know which one you are using. For example, you might hope that you could compare a string containing a date to a Date object:

var date = new Date("1999/12/31");

date == "1999/12/31"; // false

This particular example fails because converting a Date object to a string produces a different format than the one used in the example:

date.toString(); // "Fri Dec 31 1999 00:00:00 GMT-0800 (PST)"

But the mistake is symptomatic of a more general misunderstanding of coercions. The == operator does not infer and unify arbitrary data formats. It requires both you and your readers to understand its subtle coercion rules. A better policy is to make the conversions explicit with custom application logic and use the strict equality operator:

function toYMD(date) {

var y = date.getYear() + 1900, // year is 1900-indexed

m = date.getMonth() + 1, // month is 0-indexed

d = date.getDate();

return y

+ "/" + (m < 10 ? "0" + m : m)

+ "/" + (d < 10 ? "0" + d : d);

}

toYMD(date) === "1999/12/31"; // true

Making conversions explicit ensures that you don’t mix up the coercion rules of ==, and—even better—relieves your readers from having to look up the coercion rules or memorize them.

Things to Remember

• The == operator applies a confusing set of implicit coercions when its arguments are of different types.

• Use === to make it clear to your readers that your comparison does not involve any implicit coercions.

• Use your own explicit coercions when comparing values of different types to make your program’s behavior clearer.

Item 6: Learn the Limits of Semicolon Insertion

One of JavaScript’s conveniences is the ability to leave off statement-terminating semicolons. Dropping semicolons results in a pleasantly lightweight aesthetic:

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x || 0

this.y = y || 0

}

Point.prototype.isOrigin = function() {

return this.x === 0 && this.y === 0

}

This works thanks to automatic semicolon insertion, a program parsing technique that infers omitted semicolons in certain contexts, effectively “inserting” the semicolon into the program for you automatically. The ECMAScript standard precisely specifies the semicolon insertion mechanism, so optional semicolons are portable between JavaScript engines.

But similar to the implicit coercions of Items 3 and 5, semicolon insertion has its pitfalls, and you simply can’t avoid learning its rules. Even if you never omit semicolons, there are additional restrictions in the JavaScript syntax that are consequences of semicolon insertion. The good news is that once you learn the rules of semicolon insertion, you may find it liberating to drop unnecessary semicolons.

The first rule of semicolon insertion is:

Semicolons are only ever inserted before a } token, after one or more newlines, or at the end of the program input.

In other words, you can only leave out semicolons at the end of a line, block, or program. So the following are legal functions:

function square(x) {

var n = +x

return n * n

}

function area(r) { r = +r; return Math.PI * r * r }

function add1(x) { return x + 1 }

But this is not:

function area(r) { r = +r return Math.PI * r * r } // error

The second rule of semicolon insertion is:

Semicolons are only ever inserted when the next input token cannot be parsed.

In other words, semicolon insertion is an error correction mechanism. As a simple example, this snippet:

a = b

(f());

parses just fine as a single statement, equivalent to:

a = b(f());

That is, no semicolon is inserted. By contrast, this snippet:

a = b

f();

is parsed as two separate statements, because

a = b f();

is a parse error.

This rule has an unfortunate implication: You always have to pay attention to the start of the next statement to detect whether you can legally omit a semicolon. You can’t leave off a statement’s semicolon if the next line’s initial token could be interpreted as a continuation of the statement.

There are exactly five problematic characters to watch out for: (, [, +, -, and /. Each one of these can act either as an expression operator or as the prefix of a statement, depending on the context. So watch out for statements that end with an expression, like the assignment statement above. If the next line starts with any of the five problematic characters, no semicolon will be inserted. By far, the most common scenario where this occurs is a statement beginning with a parenthesis, like the example above. Another common scenario is an array literal:

a = b

["r", "g", "b"].forEach(function(key) {

background[key] = foreground[key] / 2;

});

This looks like two statements: an assignment followed by a statement that calls a function on the strings "r", "g", and "b" in order. But because the statement begins with [, it parses as a single statement, equivalent to:

a = b["r", "g", "b"].forEach(function(key) {

background[key] = foreground[key] / 2;

});

If that bracketed expression looks odd, remember that JavaScript allows comma-separated expressions, which evaluate from left to right and return the value of their last subexpression: in this case, the string "b".

The +, -, and / tokens are less commonly found at the beginning of statements, but it’s not unheard of. The case of / is particularly subtle: At the start of a statement, it is actually not an entire token but the beginning of a regular expression token:

/Error/i.test(str) && fail();

This statement tests a string with the case-insensitive regular expression /Error/i. If a match is found, the statement calls the fail function. But if this code follows an unterminated assignment:

a = b

/Error/i.test(str) && fail();

then the code parses as a single statement equivalent to:

a = b / Error / i.test(str) && fail();

In other words, the initial / token parses as the division operator!

Experienced JavaScript programmers learn to look at the line following a statement whenever they want to leave out a semicolon, to make sure the statement won’t be parsed incorrectly. They also take care when refactoring. For example, a perfectly correct program with three inferred semicolons:

a = b // semicolon inferred

var x // semicolon inferred

(f()) // semicolon inferred

can unexpectedly change to a different program with only two inferred semicolons:

var x // semicolon inferred

a = b // no semicolon inferred

(f()) // semicolon inferred

Even though it should be equivalent to move the var statement up one line (see Item 12 for details of variable scope), the fact that b is followed by a parenthesis means that the program is mis-parsed as:

var x;

a = b(f());

The upshot is that you always need to be aware of omitted semicolons and check the beginning of the following line for tokens that disable semicolon insertion. Alternatively, you can follow a rule of always prefixing statements beginning with (, [, +, -, or / with an extra semicolon. For example, the previous example can be changed to protect the parenthesized function call:

a = b // semicolon inferred

var x // semicolon on next line

;(f()) // semicolon inferred

Now it’s safe to move the var declaration to the top without fear of changing the program:

var x // semicolon inferred

a = b // semicolon on next line

;(f()) // semicolon inferred

Another common scenario where omitted semicolons can cause problems is with script concatenation (see Item 1). Each file might consist of a large function call expression (see Item 13 for more about immediately invoked function expressions):

// file1.js

(function() {

// ...

})()

// file2.js

(function() {

// ...

})()

When each file is loaded as a separate program, a semicolon is automatically inserted at the end, turning the function call into a statement. But when the files are concatenated:

(function() {

// ...

})()

(function() {

// ...

})()

the result is treated as one single statement, equivalent to:

(function() {

// ...

})()(function() {

// ...

})();

The upshot: Omitting a semicolon from a statement requires being aware of not only the next token in the current file, but any token that might follow the statement after script concatenation. Similar to the approach described above, you can protect scripts against careless concatenation by defensively prefixing every file with an extra semicolon, at least if its first statement begins with one of the five vulnerable characters (, [, +, -, or /:

// file1.js

;(function() {

// ...

})()

// file2.js

;(function() {

// ...

})()

This ensures that even if the preceding file omits its final semicolon, the combined results will still be treated as separate statements:

;(function() {

// ...

})()

;(function() {

// ...

})()

Of course, it’s better if the script concatenation process adds extra semicolons between files automatically. But not all concatenation tools are well written, so your safest bet is to add semicolons defensively.

At this point, you might be thinking, “This is too much to worry about. I’ll just never omit semicolons and I’ll be fine.” Not so: There are also cases where JavaScript will forcibly insert a semicolon even though it might appear that there is no parse error. These are the so-called restricted productions of the JavaScript syntax, where no newline is allowed to appear between two tokens. The most hazardous case is the return statement, which must not contain a newline between the return keyword and its optional argument. So the statement:

return { };

returns a new object, whereas the code snippet:

return

{ };

parses as three separate statements, equivalent to:

return;

{ }

;

In other words, the newline following the return keyword forces an automatic semicolon insertion, which parses as a return with no argument followed by an empty block and an empty statement. The other restricted productions are

• A throw statement

• A break or continue statement with an explicit label

• A postfix ++ or -- operator

The purpose of the last rule is to disambiguate code snippets such as the following:

a

++

b

Since ++ can serve as either a prefix or a suffix, but the latter cannot be preceded by a newline, this parses as:

a; ++b;

The third and final rule of semicolon insertion is:

Semicolons are never inserted as separators in the head of a for loop or as empty statements.

This simply means that you must always explicitly include the semicolons in a for loop’s head. Otherwise, input such as this:

for (var i = 0, total = 1 // parse error

i < n

i++) {

total *= i

}

results in a parse error. Similarly, a loop with an empty body requires an explicit semicolon. Otherwise, leaving off the semicolon results in a parse error:

function infiniteLoop() { while (true) } // parse error

So this is one case where the semicolon is required:

function infiniteLoop() { while (true); }

Things to Remember

• Semicolons are only ever inferred before a }, at the end of a line, or at the end of a program.

• Semicolons are only ever inferred when the next token cannot be parsed.

• Never omit a semicolon before a statement beginning with (, [, +, -, or /.

• When concatenating scripts, insert semicolons explicitly between scripts.

• Never put a newline before the argument to return, throw, break, continue, ++, or --.

• Semicolons are never inferred as separators in the head of a for loop or as empty statements.

Item 7: Think of Strings As Sequences of 16-Bit Code Units

Unicode has a reputation for being complicated—despite the ubiquity of strings, most programmers avoid learning about Unicode and hope for the best. But at a conceptual level, there’s nothing to be afraid of. The basics of Unicode are perfectly simple: Every unit of text of all the world’s writing systems is assigned a unique integer between 0 and 1,114,111, known as a code point in Unicode terminology. That’s it—hardly any different from any other text encoding, such as ASCII. The difference, however, is that while ASCII maps each index to a unique binary representation, Unicode allows multiple different binary encodings of code points. Different encodings make trade-offs between the amount of storage required for a string and the speed of operations such as indexing into a string. Today there are multiple standard encodings of Unicode, the most popular of which are UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32.

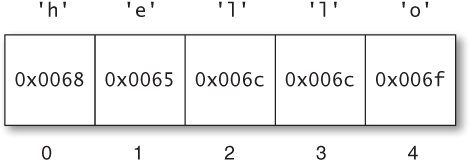

Complicating the picture further, the designers of Unicode historically miscalculated their budget for code points. It was originally thought that Unicode would need no more than 216 code points. This made UCS-2, the original standard 16-bit encoding, a particularly attractive choice. Since every code point could fit in a 16-bit number, there was a simple, one-to-one mapping between code points and the elements of their encodings, known as code units. That is, UCS-2 was made up of individual 16-bit code units, each of which corresponded to a single Unicode code point. The primary benefit of this encoding is that indexing into a string is a cheap, constant-time operation: Accessing the nth code point of a string simply selects from the nth 16-bit element of the array. Figure 1.1 shows an example string consisting only of code points in the original 16-bit range. As you can see, the indices match up perfectly between elements of the encoding and code points in the Unicode string.

Figure 1.1. A JavaScript string containing code points from the Basic Multilingual Plane

As a result, a number of platforms at the time committed to using a 16-bit encoding of strings. Java was one such platform, and JavaScript followed suit: Every element of a JavaScript string is a 16-bit value. Now, if Unicode had remained as it was in the early 1990s, each element of a JavaScript string would still correspond to a single code point.

This 16-bit range is quite large, encompassing far more of the world’s text systems than ASCII or any of its myriad historical successors ever did. Even so, in time it became clear that Unicode would outgrow its initial range, and the standard expanded to its current range of over 220 code points. The new increased range is organized into 17 subranges of 216 code points each. The first of these, known as the Basic Multilingual Plane (or BMP), consists of the original 216 code points. The additional 16 ranges are known as the supplementary planes.

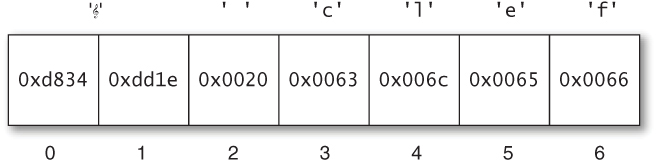

Once the range of code points expanded, UCS-2 had become obsolete: It needed to be extended to represent the additional code points. Its successor, UTF-16, is mostly the same, but with the addition of what are known as surrogate pairs: pairs of 16-bit code units that together encode a single code point 216 or greater. For example, the musical G clef symbol (“ ”), which is assigned the code point U+1D11E—the conventional hexadecimal spelling of code point number 119,070—is represented in UTF-16 by the pair of code units

”), which is assigned the code point U+1D11E—the conventional hexadecimal spelling of code point number 119,070—is represented in UTF-16 by the pair of code units 0xd834 and 0xdd1e. The code point can be decoded by combining selected bits from each of the two code units. (Cleverly, the encoding ensures that neither of these “surrogates” can ever be confused for a valid BMP code point, so you can always tell if you’re looking at a surrogate, even if you start searching from somewhere in the middle of a string.) You can see an example of a string with a surrogate pair in Figure 1.2. The first code point of the string requires a surrogate pair, causing the indices of code units to differ from the indices of code points.

Figure 1.2. A JavaScript string containing a code point from a supplementary plane

Because each code point in a UTF-16 encoding may require either one or two 16-byte code units, UTF-16 is a variable-length encoding: The size in memory of a string of length n varies based on the particular code points in the string. Moreover, finding the nth code point of a string is no longer a constant-time operation: It generally requires searching from the beginning of the string.

But by the time Unicode expanded in size, JavaScript had already committed to 16-bit string elements. String properties and methods such as length, charAt, and charCodeAt all work at the level of code units rather than code points. So whenever a string contains code points from the supplementary planes, JavaScript represents each as two elements—the code point’s UTF-16 surrogate pair—rather than one. Simply put:

An element of a JavaScript string is a 16-bit code unit.

Internally, JavaScript engines may optimize the storage of string contents. But as far as their properties and methods are concerned, strings behave like sequences of UTF-16 code units. Consider the string from Figure 1.2. Despite the fact that the string contains six code points, JavaScript reports its length as 7:

" clef".length; // 7

clef".length; // 7

"G clef".length; // 6

Extracting individual elements of the string produces code units rather than code points:

" clef".charCodeAt(0); // 55348 (0xd834)

clef".charCodeAt(0); // 55348 (0xd834)

" clef".charCodeAt(1); // 56606 (0xdd1e)

clef".charCodeAt(1); // 56606 (0xdd1e)

" clef".charAt(1) === " "; // false

clef".charAt(1) === " "; // false

" clef".charAt(2) === " "; // true

clef".charAt(2) === " "; // true

Similarly, regular expressions operate at the level of code units. The single-character pattern (“.”) matches a single code unit:

/^.$/.test(" "); // false

"); // false

/^..$/.test(" "); // true

"); // true

This state of affairs means that applications working with the full range of Unicode have to work a lot harder: They can’t rely on string methods, length values, indexed lookups, or many regular expression patterns. If you are working outside the BMP, it’s a good idea to look for help from code point-aware libraries. It can be tricky to get the details of encoding and decoding right, so it’s advisable to use an existing library rather than implement the logic yourself.

While JavaScript’s built-in string datatype operates at the level of code units, this doesn’t prevent APIs from being aware of code points and surrogate pairs. In fact, some of the standard ECMAScript libraries correctly handle surrogate pairs, such as the URI manipulation functions encodeURI, decodeURI, encodeURIComponent, and decodeURIComponent. Whenever a JavaScript environment provides a library that operates on strings—for example, manipulating the contents of a web page or performing I/O with strings—you should consult the library’s documentation to see how it handles the full range of Unicode code points.

Things to Remember

• JavaScript strings consist of 16-bit code units, not Unicode code points.

• Unicode code points 216 and above are represented in JavaScript by two code units, known as a surrogate pair.

• Surrogate pairs throw off string element counts, affecting length, charAt, charCodeAt, and regular expression patterns such as “.”.

• Use third-party libraries for writing code point-aware string manipulation.

• Whenever you are using a library that works with strings, consult the documentation to see how it handles the full range of code points.