Chapter 1. Serverless and OpenWhisk Architecture

Welcome to the world of Apache OpenWhisk. OpenWhisk is an open source Serverless platform, designed to make easy and fun developing applications in the Cloud.

Serverless does not mean “without the server”, it means “without managing the server”. Indeed we will see how we can build complex applications without having to care of the server (except, of course, when we deploy the platform itself).

A serverless environment is most suitable for a growing class of applications needing processing “in the cloud” that you can split into multiple simple services. It is often referred as a “microservices” architecture.

Typical applications using a Serverless environment are:

-

services for static or third party websites

-

voice applications like Amazon Alexa

-

backends for mobile applications

This chapter is the first of the book, so we start introducing the architecture of OpenWhisk, its, and weaknesses.

Once you have a bird’s eye look to the platform, we can go on, discussing its architecture to explain the underlying magic. We focus on the Serverless Model to give a better understanding of how it works and its constraints. Then we complete the chapter trying to put things in perspective, showing how we got there and its advantages compared with similar architectures already in use: most notably to what is most likely its closest relative: JavaEE.

Apache OpenWhisk Architecture

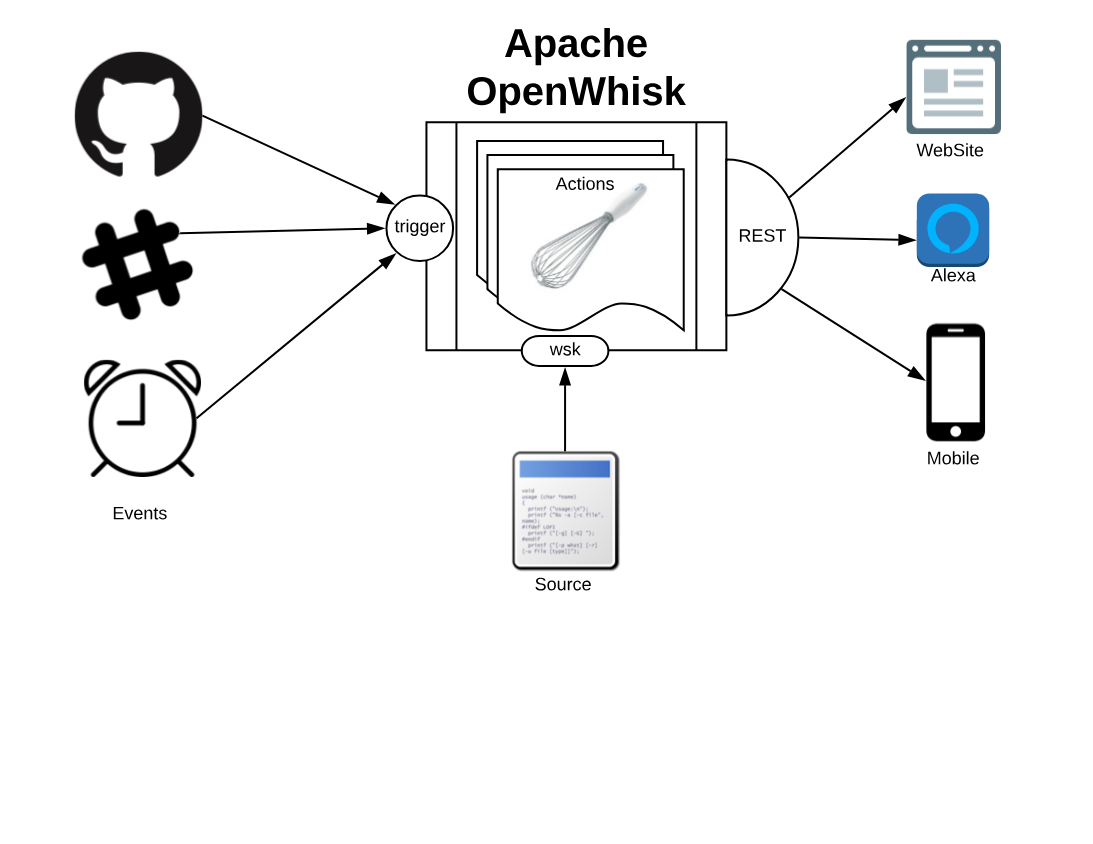

Apache OpenWhisk, shown in Figure Figure 1-1, according to its definition, is a Serverless Open Source Cloud Platform. It works executing functions (called Actions) in response to Events at any scale. Events can be originated by multiple sources, including timers, or websites like Slack or GitHub.

It accepts source code as input, provisioned straight with a command line interface, then delivers services through the web to multiple consumers. Examples of typical consumers are other websites, mobile applications or services based on REST APIs like the voice assistant Amazon Alexa.

Figure 1-1. Apache OpenWhisk from the Outside

Functions and Events

Computation in a Serverless environment is generally split in functions. A function is typically a piece of code that will receive input and will provide an output in response. It is important to note that a function is expected to be stateless.

Frequently web applications are stateful. Just think of a shopping cart application for an e-commerce: while you navigate the website, you add your items to the basket, to buy them at the end. You keep a state, the cart.

Being stateful however is an expensive property that limits scalability: you need to provide something to store data. Most importantly, you will need something to synchronize the state between invocations. When your load increase, this “state keeping” infrastructure will limit your ability to grow. If you are stateless, you can usually add more servers.

The OpenWhisk solution, and more widely the solution adopted by Serverless environments is the requirement functions must be stateless. You can keep state, but you will use separate storage designed to scale.

To run functions to perform our computations, the environment will manage the infrastructure and invoke the actions when there is something to do.

In short, “having something to do” is what is called an event. So the developer must code thinking what to do when something happens (a request from the user, a new data is available), and process it quickly. The rest belongs to the cloud environment.

In conclusion, Serverless environments allow you to build your application out of simple stateless functions, or actions as they are called in the context of OpenWhisk, triggered by events. We will see later in this chapter which other constraints those actions must satisfy.

Architecture Overview

We just saw OpenWhisk from the outside, and now we have an idea of what it does. Now it is time to investigate its architecture, to understand better how it works under the hood.

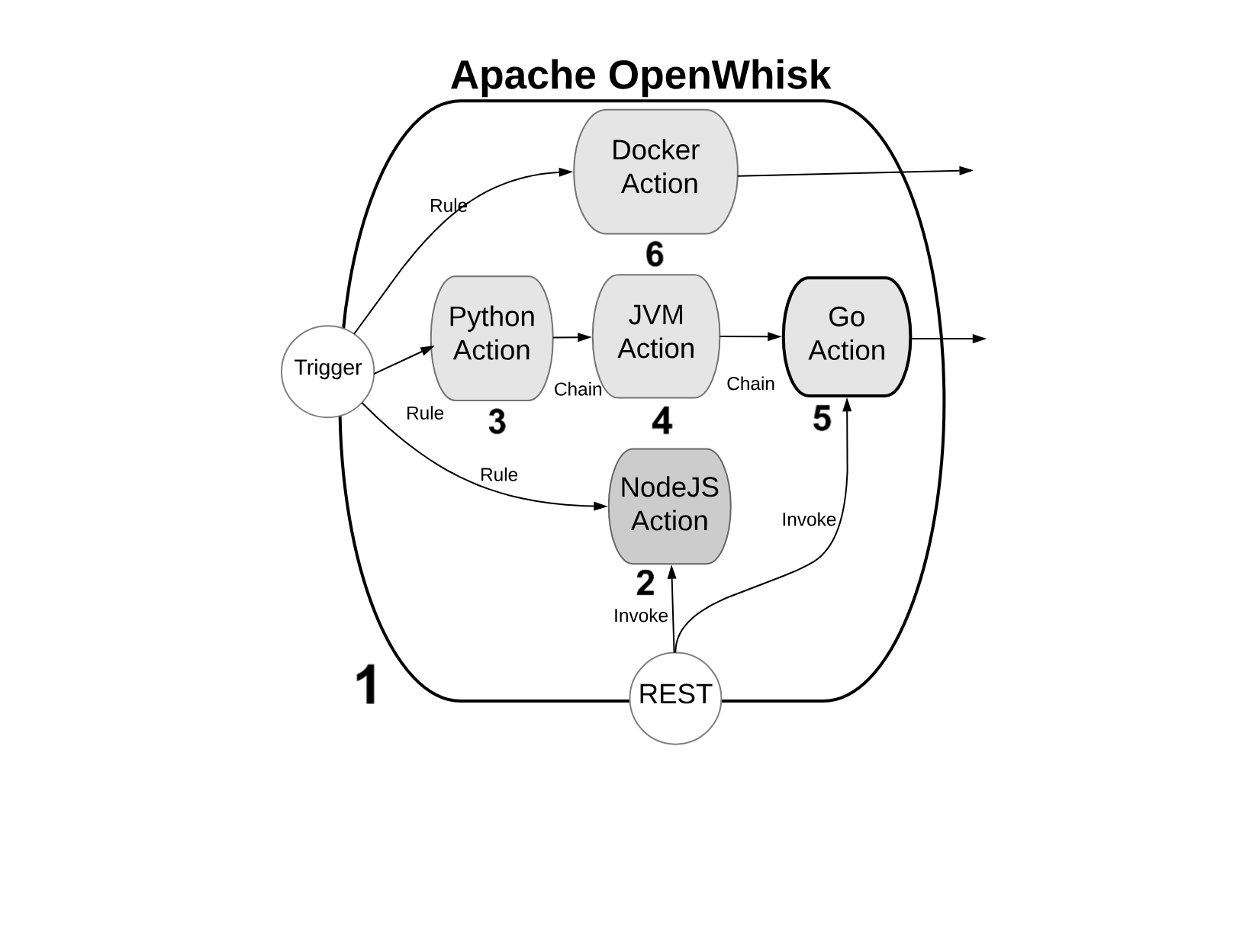

Figure 1-2. OpenWhisk High Level Archiecture - Actions

We will refer to the Figure Figure 1-2, with some numbered markers. In the Figure, the big container (see 1) at the center, is OpenWhisk itself. It acts as a container of actions. We will see later what an action and what the container is.

Warning

Actions, as you can see, can be developed in many programming languages. We will discuss the differences among the various options in the next paragraph.

For the architect, you can consider it as an opaque system that executes those actions in response to events.

Note

It is essential to know the “container” will schedule them, creating and destroying actions that are not needed, and it will also scale them, creating duplicates in response to an increase in load.

Programming Languages for OpenWhisk

You can write actions in many programming languages. Probably the more natural to use are interpreted programming languages: like JavaScript (see 2) (actually, Node.js) or Python (see 3). Those programming languages are interpreted and give an immediate feedback since you can execute them without compilation. They are also generally of higher level, hence more comfortable to use (while the drawback is usually they are slower than compiled languages). Since OpenWhisk is a highly responsive system, where you can immediately run your code in the cloud, probably the majority of the developers prefer to use those “interactive” programming languages.

Note

The “default” language for OpenWhisk is indeed Javascript. However other languages are also first class citizen. While Javascript is the more commonly used, nothing in OpenWhisk favors it over other languages.

In addition to purely interpreted (or compiled-on-the-fly languages, as it is correct to say), you can use also pre-compiled interpreted languages, like the languages of the Java family. Java, Scala and Kotlin (see 4) are the more common programming languages of this family. They run on the Java Virtual Machine, and they are distributed not in source form but an intermediate form. The developer must create a “jar” file to run the action. This jar includes the so-called “bytecode” that OpenWhisk will execute when it will be deployed . A Java Virtual Machine is the actual executor of the action.

Finally, in OpenWhisk you can use compiled languages, producing a binary executable that runs on “bare metal” without interpreters or virtual machines. Examples of those binary languages are Swift, Go or the classical C/C++, see (see 5).

OpenWhisk supports out-of-the-box Go and Swift. You need to send the code of an action compiled in Linux elf format for the amd64 processor architecture, so a compilation infrastructure is needed. However today, with the help of Docker, is not complicated to install on any system the necessary toolchain for the compilation.

Finally, you can use in OpenWhisk any arbitrary language or system that can you can package like a Docker image (see 6) and that you can publish on Docker Hub: OpenWhisk allows to retrieve such an image and run it, as long as you follow its conventions. We will discuss this in the chapter devoted to native actions.

Actions and Action Composition

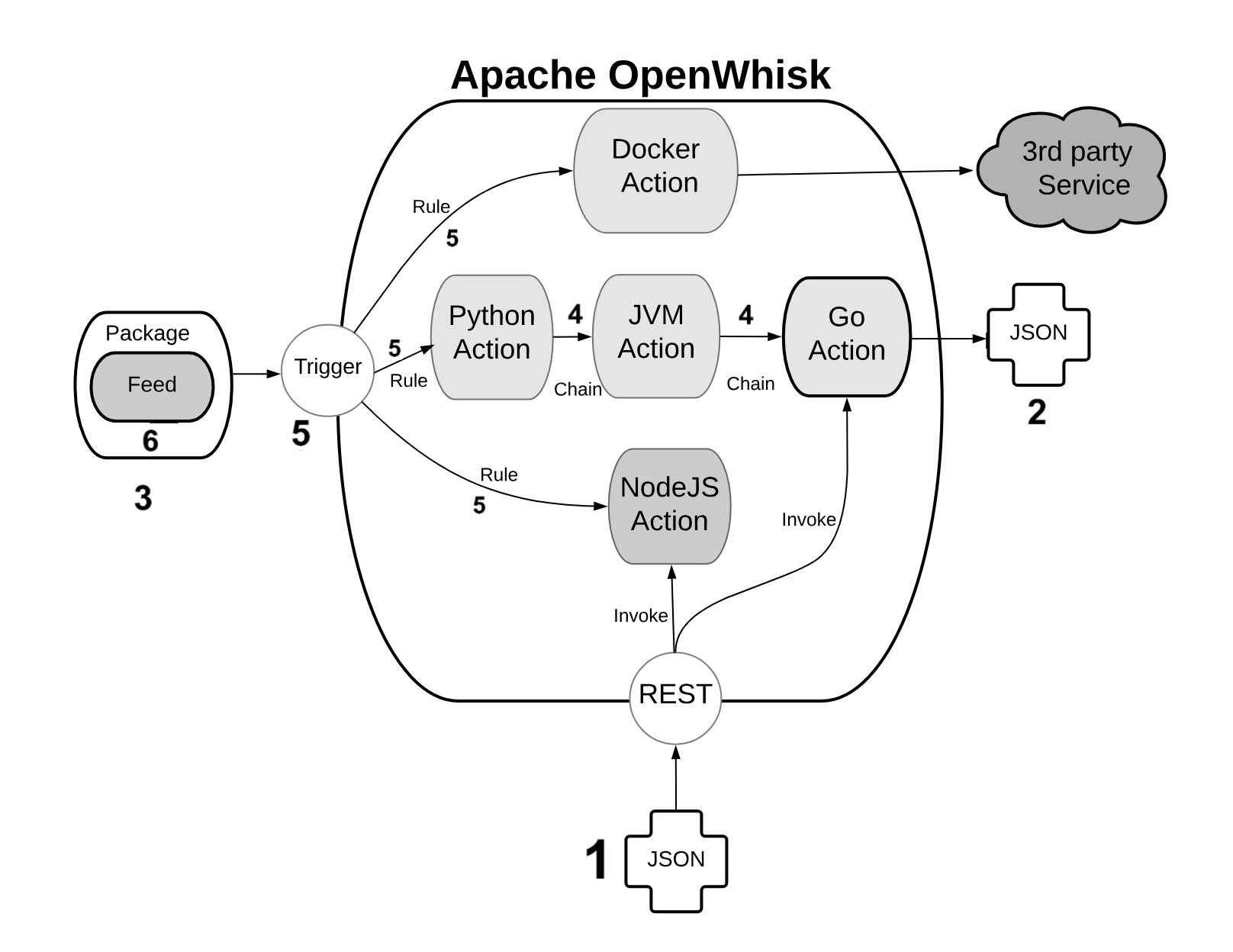

OpenWhisk applications are a collection of actions. We already saw the available type of actions. Now let’s see in Figure Figure 1-3 how they are assembled to build applications.

Figure 1-3. Open Whisk High Level Architecture - Components

An action is a piece of code, written in one of the supported programming languages, that you can invoke. On invocation, the action will receive some information as input (see 1).

To standardize parameter passing among multiple programming languages, OpenWhisk uses the widely supported JSON format, since it is pretty simple, and there are libraries to encode and decode this format available basically for every programming language.

The parameters are passed to actions as a JSON string, that the action receives when it starts, and it is expected to process. At the end of the processing, each action must produce its result that is then returned also as a JSON string (see 2).

You can group actions in packages (see 3). A package acts as a unit of distribution. You can share a package with others using bindings. You can also customize a package providing parameters that are different for each binding.

Actions can be combined in many ways. The simplest form of combination is chaining them in sequences (see 4)

Chained actions will use as input the output of the preceding actions. Of course, the first action of a sequence will receive the parameters (in JSON format), and the last action of the sequence will produce the final result, as a JSON string.

However, since not all the flows can be implemented as a linear pipeline of input and output, there is also a way to split the flow of an action in multiple directions.

This feature is implemented using triggers and rules (see 5).

A trigger is merely a named invocation. You can create a trigger, but by itself a trigger does nothing. However, you can then associate the trigger with multiple actions using Rules.

Once you have created the trigger and associated some action with it, you can fire the trigger providing parameters.

Note

Triggers cannot be part of a package. They are something top-level. They can be part of a namespace, however, discussed in the following paragraph.

The connection between actions and triggers is called a feed (see 6). A feed is an ordinary action that must follow an implementation pattern. We will see in the chapter devoted to the design pattern. Essentially it must implement an observer pattern, and be able to activate a trigger when an event happens.

When you create an action that follows the feed pattern (and that can be implemented in many different ways), that action can be marked as a feed in a package. In this case, you can combine a trigger and feed when you deploy the application, to use a feed as a source of events for a trigger (and in turn activate other actions).

How OpenWhisk Works

Once it is clear what are the components of OpenWhisk, it is time to see what are the actual steps that are performed when it executes an action.

As we can see the process is pretty complicated. We are going to meet some critical components of OpenWhisk. OpenWhisk is “built on the shoulder of giants,” and it uses some widely known and well developed open source projects.

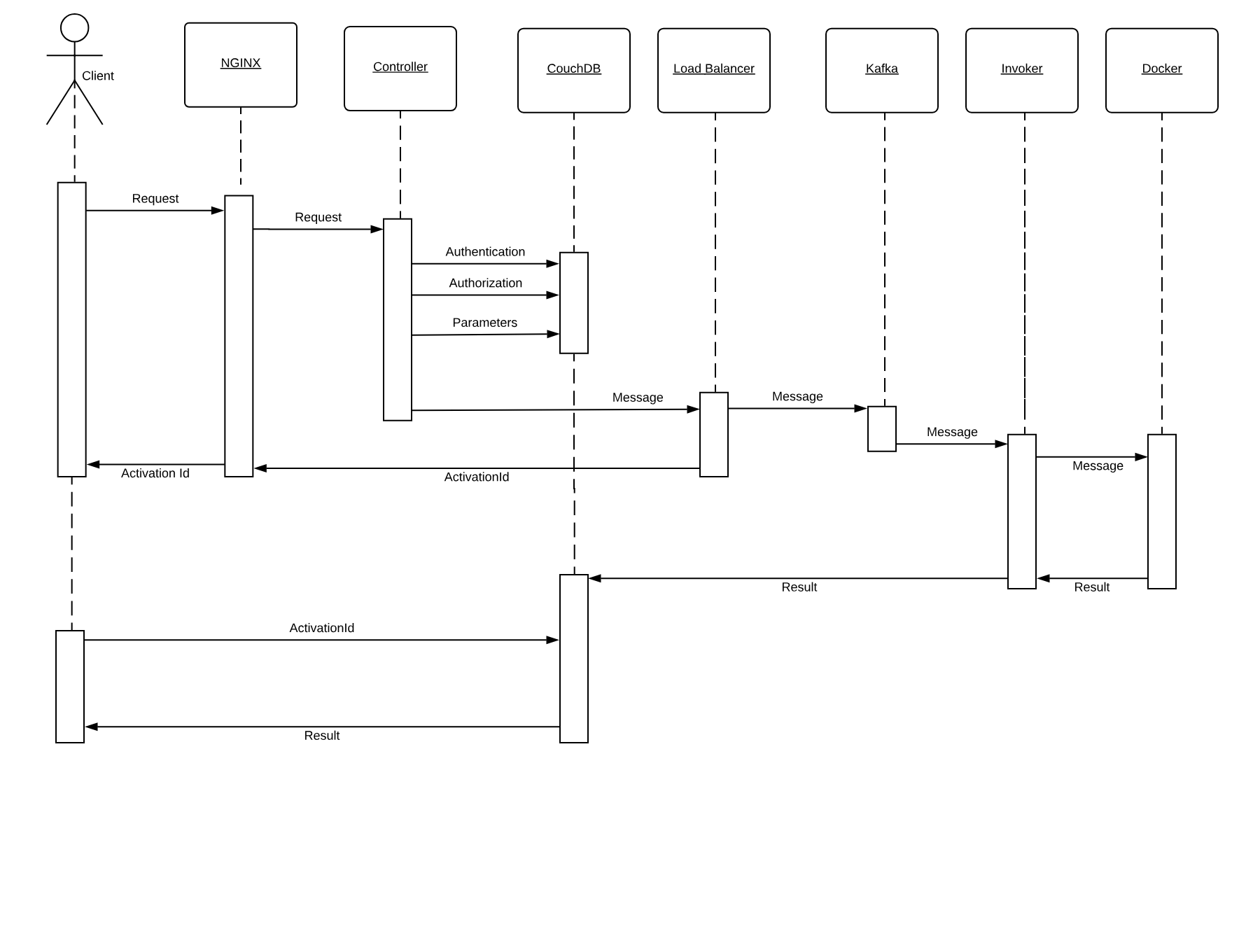

Figure 1-4. How OpenWhisk processes an action

More in detail it includes:

-

NGINX, a high-performance web server and reverse proxy.

-

CouchDB, a scalable, document-oriented, NO-SQL Database.

-

Kafka, a distributed, high performing, publish-subscribe messaging system.

-

Docker, an environment to manage execution of applications in an efficient but constrained, virtual-machine like environment.

Furthermore, OpenWhisk can be split into some components of its own:

-

the Controller, managing the execution of actions

-

the Load Balancer, distributing the load

-

the Invoker, actually executing the actions

In Figure Figure 1-4 we can see how the whole processing happens. We are going to discuss it in detail, step by step.

Note

Basically, all the processing done in OpenWhisk is asynchronous, so we will go into the details of an asynchronous action invocation. Synchronous execution fires an asynchronous execution and then wait for the result.

Nginx

Everything starts when an action is invoked. There are different ways to invoke an action:

-

from the Web, when the action is exposed as Web Action

-

when another action invokes it through the API

-

when a trigger is activated and there is a rule to invoke the action

-

from the Command Line Interface

Let’s call the client the subject who invokes the action. OpenWhisk is a RESTful system, so every invocation is translated in an https call and hits the so-called “edge” node.

The edge is actually the web server and reverse proxy Nginx. The primary purpose of Nginx is implementing support for the “https” secure web protocol. So it deploys all the certificates required for secure processing. Nginx then forwards the requests to the actual internal service component, the Controller.

Controller

The Controller, that is implemented in Scala, before effectively executing the action, performs pretty complicated processing.

-

It needs to be sure it can execute the action. Hence the need to authenticate the requests, verifying if the source of the request is a legitimate subject.

-

Once the origin of the request has been identified, it needs to be authorized, verifying that the subject has the appropriate permissions.

-

The request must be enriched with all the default parameters that have been configured. Those parameters, as we will see, are part of the action configuration.

To perform all those steps the Controller consults the database, that in OpenWhisk is CouchDB.

Once validated and enriched, the action is now is ready to be executed, so it is sent to the next component of the processing, the Load Balancer.

Load Balancer

Load Balancer job, as its name states, is to balance the load among the various executors in the system, which are called in OpenWhisk Invokers.

We already saw that OpenWhisk executes actions in runtimes, and there are runtimes available for many programming languages. The Load Balancer keeps an eye on all the available instances of the runtime, checks its status and decide which one should be used to serve the new action requested, or if it must create a new instance.

We got to the point where the system is ready to invoke the action. However, you can not just send your action to an Invoker, because it can be busy serving another action. There is also the possibility that an invoker crashed, or even the whole system may have crashed and is restarting.

So, because we are working in a massively parallel environment that is expected to scale, we have to consider the eventuality we do not have the resources available to execute the action immediately. Hence we have to buffer invocations.

The solution for this purpose is using Kafka. Kafka is a high performing “publish and subscribe” messaging system, able to store your requests, keep them waiting until they are ready to be executed. The request is turned in a message, addressed to the invoker the Load Balancer chose for the execution.

Each message sent to an Invoker has an identifier, the ActivationId. Once the message has been queued in Kafka, the ActivationId is sent back as the final answer of the request to the client, and the request completes.

Because as we said the processing is asynchronous, the Client is expected to come back later to check the result of the invocation.

Invoker

The Invoker is the critical component of OpenWhisk and it is in charge of executing the Actions. Actions are actually executed by the Invoker creating an isolated environment provided by Docker.

Docker can create execution environments (called “Containers”) that resemble an entire operating system, providing everything code written in any programming language needs to run.

In a sense, an environment provided by Docker looks like, as seen by action, to an entire computer for it (just like a Virtual Machine). However, execution within containers is much more efficient than VMs, so they are used in preference to actual emulated environments.

Note

It would be safe to say that, without containers, the entire concept of a Serverless Environment like OpenWhisk executing actions as separate entities, would not have been possible to implement.

Docker actually uses Images as the starting point for creating containers where it executes actions. A runtime is really a Docker image. The Invoker launches a new Image for the chosen runtime then initialize it with the code of the action.

OpenWhisk provides a set of Docker Images including support for the various languages, and the execution logic to accept the initialization: JavaScript, Python, Java, Go, etc.

Once the runtime is up and running, the invoker passes the whole action requests that have been constructed in the processing so far. Also, Invokers will take care of managing and storing logs to facilitate debugging.

Once OpenWhisk completes the processing, it must store the result somewhere. This place is again CouchDB (where also configuration data are stored). Each result of the execution of an action is then associated with the ActivationId, the one that was sent back to the client. Thus the client will be able to retrieve the result of its request querying the database with the id.

Aysnchronous Client

As we already said, the processing described so far is asynchronous. This fact means the client will start a request and forget. Well, it will not leave it behind entirely, because it returns an activation id as a result of an invocation. As we have seen so far, the activation id is used to associate the result in the database after the processing.

So, to retrieve the final result, the client will have to perform a request again later, passing the activation id as a parameter. Once the action completes, the result, the logs, and other information are available in the database and can be retrieved.

Synchronous processing is available in addition to the asynchronous one. It primarily works in the same way as the asynchronous, except the client will block waiting for the action to complete and retrieve the result immediately.

Serverless Execution Constraints

The OpenWhisk architecture and its way of operation mandate that, When you develop Serverless applications, you have to abide by some constraints and limitations.

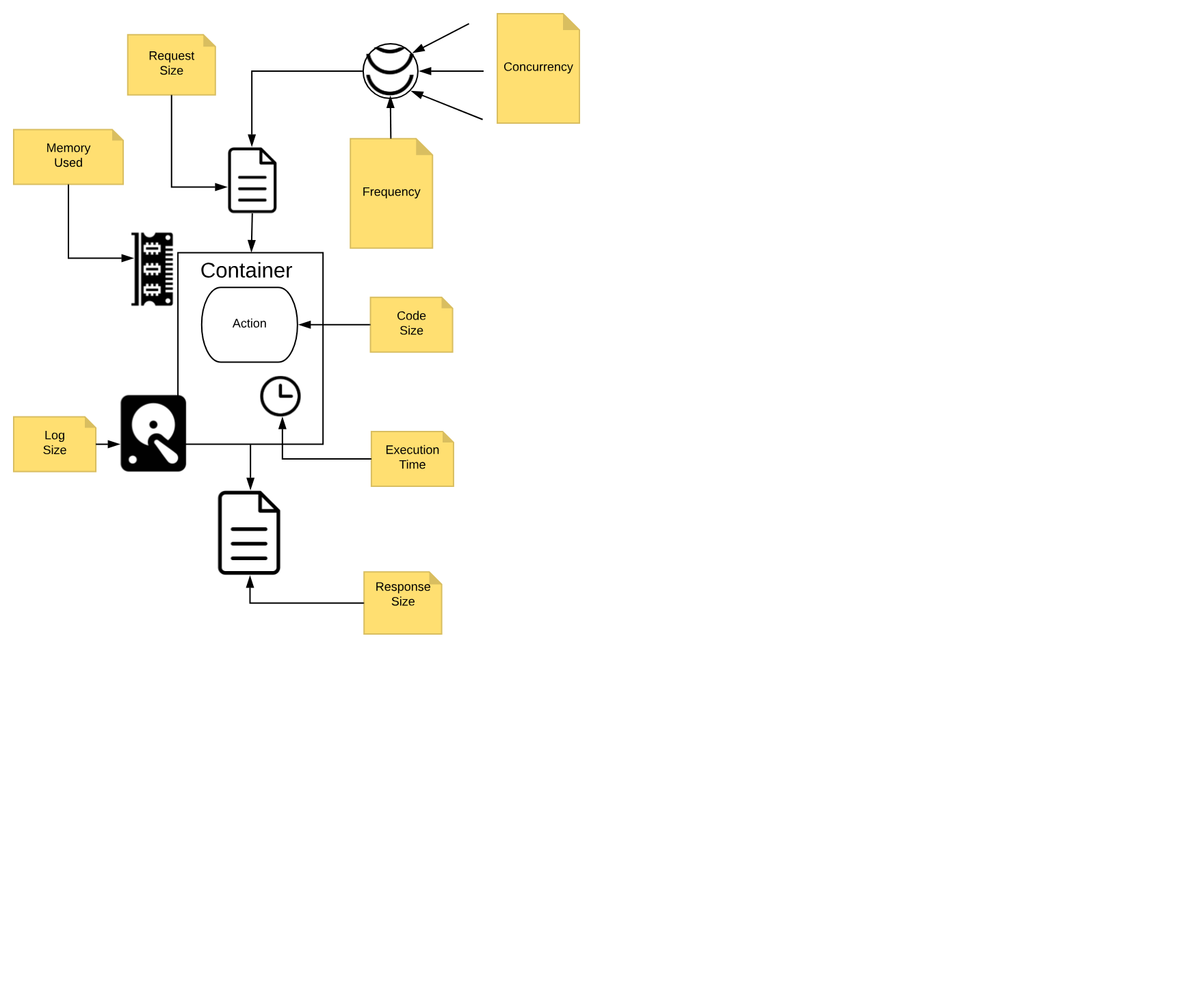

Figure 1-5. OpenWhisk Action Execution Constraints

We call those constraints execution model, and we are going to discuss it in detail.

You need to think to your application as decomposed as a set of actions, collaborating each other to reach the purpose of the application.

It is essential to keep in mind that each action, running in a Serverless environment, will be executed within certain limits, and those limits must be considered when designing the application.

Action Execution Constraints

In Figure Figure 1-5 are depicted the significant constraints an action is subject.

All the constraints have some value in term of time or space, either timeout, frequency, memory, size of disk space. Some are configurable; others are hardcoded. The standard values (that can be different according to the particular cloud or installation you are using) are:

-

execution time: max 1 minute per action (configurable)

-

memory used: max 256MB per action (configurable)

-

log size: max 10MB per action (configurable)

-

code size: max 48MB per action (fixed)

-

parameters: max 1MB per action (fixed)

-

result: max 1MB per action (fixed)

Furthermore, there are global constraints:

-

concurrency: max 100 concurrent activations can be queued at the same time (configurable)

-

frequency: max 120 activations per minute can be requested (configurable)

Note

Global constraints are actually per namespace. Think to a namespace as the collection of all the OpenWhisk resources assigned to a specific user, so it is practically equivalent to a Serverless application, since it is split into multiple entities.

Let’s discuss more in detail those constraints.

Actions are Functional

As already mentioned, each action must be a function, invoked with a single input and must produce a single output.

The input is a string in JSON format. The action usually deserializes the string in a data structure, specific to the programming language used for the implementation.

The runtime generally performs the deserialization, so the developer will receive an already parsed data structure.

If you use dynamic languages like Javascript or Python, usually you receive something like a Javascript object or a Python dictionary, that can be efficiently processed using the feature of the programming language.

If you use a more statically typed language like Java or Go, you may need to put more effort in decoding the input. Libraries for performing the decoding task are generally readily available. However, some decoding work may be necessary to map the generally untyped arguments to the typed data structure of the language.

The same holds true for returning the output. It must be a single data structure, the programming language you are using can create, but it must be serialized back in JSON format before being returned. Runtimes also usually take care of serializing data structures back in a string.

Actions are Event Driven

Everything in the Serverless environment is activated by events. You cannot have any long running process. It is the system that will invoke actions, only when they are needed.

For example, an event is a user that when is browsing the web opens the URL of a serverless application. In such a case, the action is triggered to serve it.

However, this is only one possible event. Other events include for example a request, maybe originated by another action, that arrives on a message queue.

Also, database management is event-driven. You can perform a query on a database, then wait until an event is triggered when the data arrives.

Other websites can also originate events. For example, you may receive an event:

-

when someone pushes a commit on GitHub

-

when a user interacts with Slack and sends a message

-

when a scheduled alarm is triggered

-

when an action update a database

etc.

Actions do not have Local State

Actions are executed in Docker containers. As a consequence (by Docker design) file system is ephemeral. Once a container terminates, all the data stored on the file system will be removed too.

However, this does not mean you cannot store anything on files when using a function. You can use files for temporary data while executing an application.

Indeed a container can be used multiple times, so for example, if your application needs some data downloaded from the web, an action can download some stuff it makes available to other actions executed in the same container.

What you cannot assume is that the data will stay there forever. At some point in time, either the container will be destroyed or another container will be created to execute the action. In a new container, the data you downloaded in a precedent execution of the action will be no more available.

In short, you can use local storage only as a cache for speed up further actions, but you cannot rely on the fact data you store in a file will persist forever. For long-term persistence, you need to use other means. Typically a database or another form of cloud storage.

Actions are Time Bounded

It is essential to understand that action must execute in the shortest time possible. As we already mentioned, the execution environment imposes time limits on the execution time of an action. If the action does not terminate within the timeout, it will be aborted. This fact is also true for background actions or threads you may have started.

So you need to be well aware of this behavior and ensure your code will not keep going for an unlimited amount of time, for example when it gets larger input. Instead, you may sometimes need to split the processing into smaller chunks and ensure the execution time of your action will stay within limits.

Also usually the billing charge is time-dependent. If you run your application in a cloud provider supporting OpenWhisk, you are charged for the time your action takes. So faster actions will result in lower cost. When you have millions of actions executed, a few milliseconds speedier action can sum up in significant savings.

Actions are Not Ordered

Note also that actions are not ordered. You cannot rely on the fact action is invoked before another. If you have action A at time X and action B at time Y, with X < Y, action B can be executed before A.

As a consequence, if the action has a side effect, for example writing in the database, the side effect of action A may be applied later than the action B. Furthermore, there is not even any guarantee that an action will be executed entirely before or after another action. They may overlap in time.

So for example when you write in a database you must be aware that while you are writing in it, and before you have finished, another action may start writing in it too. So you have to provide your transaction support.

From JavaEE to Serverless

The Serverless Architecture looks brand new, however it shares concepts and practices with existing architectures. In a sense, it is an evolution of those historical architectures.

Of course, every architectural decision made in the past has been adapted to emerging technologies, most notably virtualization and containers. Also, the requirements of the Cloud era impose scalability virtually unlimited.

To better understand the genesis and the advantages of the Serverless Architecture, it makes sense to compare OpenWhisk architecture it with another essential historical precedent that is currently in extensive use: the Architecture of Java Enterprise Edition, or JavaEE.

Classical JavaEE Architecture

The core idea behind JavaEE was allowing the development of large application out of small, manageable parts. It was a technology designed to help application development for large organizations, using the Java programming language. Hence the name of Java Enterprise Edition.

Note

At the time of the creation of JavaEE, everything was based on the Java programming language, or more specifically, the Java Virtual Machine. Historically, when JavaEE was created Java was the only programming language available for building large, scalable applications (meant to replace C++). Scripting languages like Python were at the time considered toys and not in extensive use.

To facilitate the development of that vast and complex application, JavaEE provided a productive (and complicated) infrastructure of services.

To use them, JavaEE offered many different types of components, each one deployable separately, and many ways to let the various part to communicate with each other.

Those services were put together and made available through the use of Application Server. JavaEE itself was a specification.

The actual implementation was a set of competing products. The most prominent names in the world of application servers that are still in broad use today are Oracle Weblogic and IBM WebSphere.

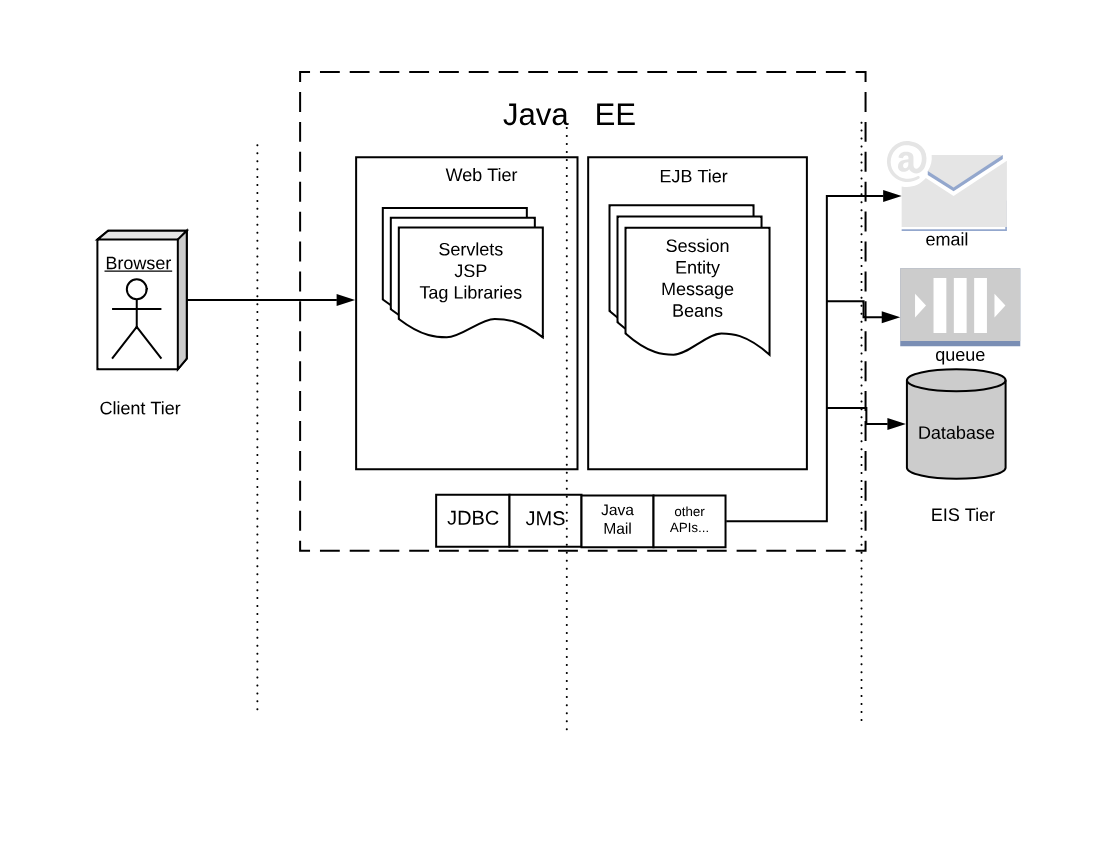

Figure 1-6. JavaEE Architecture

If we look at the classical JavaEE architecture we can quickly identify the following tiers:

-

The client (front end) tier

-

The web (back-end) tier

-

The EJB (business) tier

-

The EIS (integration) tier

The following ideas characterize it:

-

Application is split into discrete components, informally called beans.

-

Components are executed in (Java-based) containers.

-

Interface to the external world is provided by connectors.

In JavaEE, we have different types of components.

The client tier is expected to implement the application logic at the client level. Historically Java was used to implement applet, small java components that can be downloaded and run in the browser. Javascript, CSS, and HTML nowadays entirely replace those web components

In the web tier, the most crucial kind of components are the servlets. They are further specialized in JSP, tag libraries, etc. Those components define the web user interface at the server level.

The so-called business logic, managing data and connection to other “enterprise systems” is expected to be implemented in the Business Tier using the so-called EJB (Enterprise Java Beans). There were many flavors of EJB, like Entity Beans, Session Beans, Message Beans, etc.

Each component in JavaEE is a set of Java classes that must implement an API. The developer writes those classes and then deliver them to the Application Server, that loads the components and run them in their containers.

Furthermore, application servers also provide a set of connectors to interface the application with the external world, the EIS tier. There were connectors, written for Java, allowing to interface to virtually any resource of interest,

The more common in JavaEE are connectors to:

-

databases

-

message queues

-

email and other communication systems

In the JavaEE world, Application Servers provided the implementation of all the JavaEE specification, and included APIs and connectors, to be a one-stop solution for all the development needs of enterprises.

Serveless equivalent of JavaEE

For many reasons, the architecture of Serverless application and OpenWhisk can be seen as an evolution of JavaEE. Everything starts from the same basic idea: split your application into many small, manageable parts, and provide a system to quickly put together all those pieces.

However, the technological landscape driving the development of Serverless environment is different than the one driving JavaEE development. In our brave new world, we have:

-

applications are spread among multiple servers in the cloud, requiring virtually infinite scalability

-

numerous programming languages, including scripting languages, are in extensive use and must be usable

-

virtual machine and container technologies are available to wrap and control the execution of programs

-

HTTP can be considered a standard transport protocol

-

JSON is simple and widely used to be usable as a universal exchange format

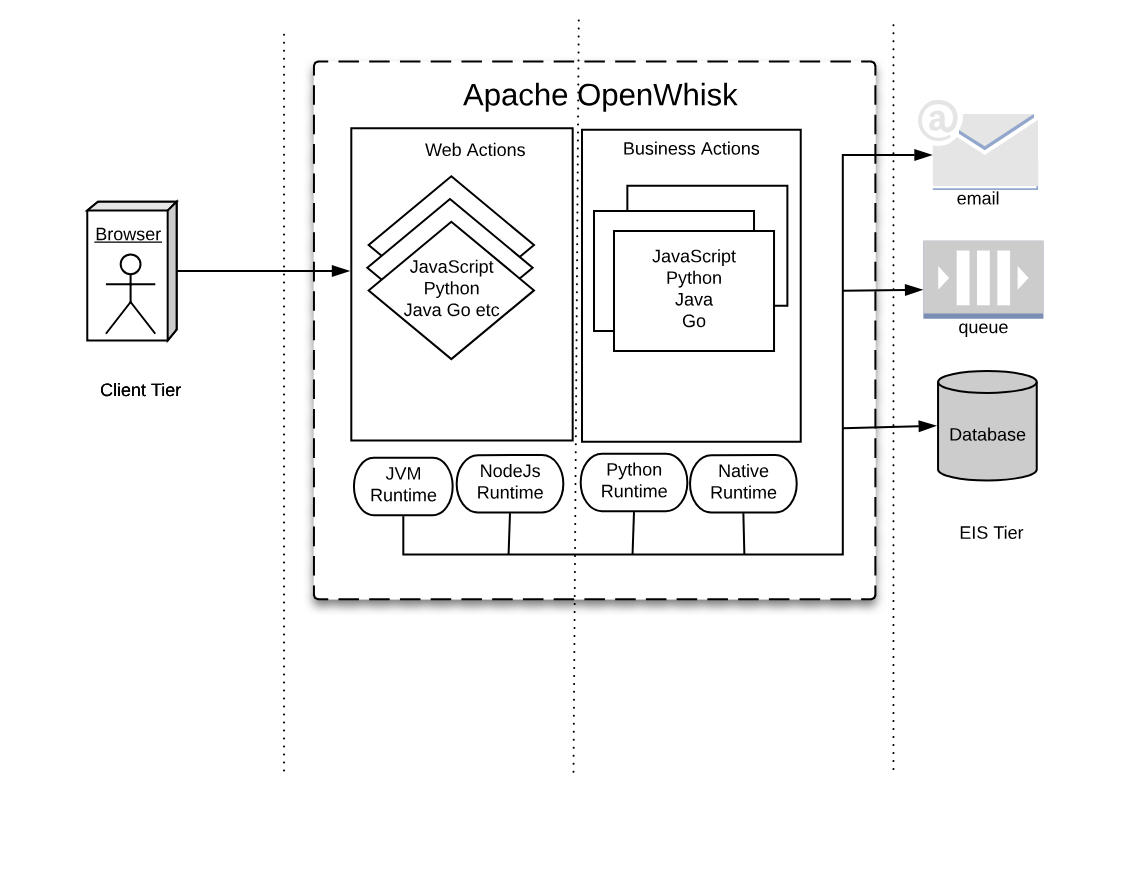

Now, let’s compare JavaEE with the OpenWhisk architecture in Figure Figure 1-7. The Figure is intentionally similar to the Figure Figure 1-6, to highlight similarities and differences.

Figure 1-7. Serverless Architecture

Tiers

As you can see in the Figure, we can recognize web tier and a business tier also in OpenWhisk, in addition to a client and an integration tier.

While there is not a formal difference between the two tiers, in practice we have actions directly exposed to the web (web actions) and actions that are not.

Web Actions can be considered to be the web tier. Those actions which are meant to serve events, either coming from web actions or triggered by other services in the infrastructure, can be considered “Business Actions,” defining a “Business Tier.”

Components

In JavaEE, everything runs in the Java Virtual Machine, and everything must be coded in Java (or any language that can generate JVM-compatible byte-code).

In OpenWhisk, you can code applications in multiple programming languages. We use their runtimes as equivalents of the Java Virtual Machine. Furthermore, those runtimes are wrapped in Docker containers to provide isolation and control over resource usage.

Hence you can write your components in any (supported) language you like. You are no more confined to write your application solely for the JVM. However, a JVM runtime is available, so you can still use Java and its family of languages if you like.

You can now write your code for the JavaScript Virtual Machine, more commonly referred to as NodeJs .

Note

Under the hood, Nodes it is an adaptation of the V8 Javascript interpreter that powers the Chrome Browser. It is a fast executor of the javascript language, which also does complicated things like compiling on-the-fly to native code.

If you choose to use the Python programming languages, you are also using its interpreter. Python has many available interpreters, one being the move widely used CPython, but there is also other available, like Pypy. The JVM can even execute Python.

Furthermore, you may choose not to use a virtual machine at all, but write your application in a language producing native executables like Swift or Go. In the Serverless world, it is becoming to become a popular choice. As long as you compile your application for Linux and AMD64, you can use it for OpenWhisk.

APIs

In JavaEE, you have APIs available to interact with the rest of the world, written in Java itself. Basically, the JavaEE model is , and every interesting resource for writing applications has been adapted to be used by Java.

In OpenWhisk, you have first and before all only one API, available for all the supported programming languages. This API is the OpenWhisk API itself, and it is a RESTful API. You can invoke it over HTTP using JSON as an interchange format.

This API can even be invoked directly just using an HTTP library, reading and writing JSON strings. However, are available wrappers for all the supported programming languages to use it efficiently. This API acts as glue for the various components in OpenWhisk.

All the communication between the different parts in OpenWhisk are performed in JSON over HTTP.

Connectors

In JavaEE, you have connectors for each external system you want to communicate with, primarily drivers. For example, if you’re going to interact with an Oracle database you need an Oracle JDBC driver, to communicate with IBM DB2 you need a specify DB2 JDBC driver, etc. The same holds true for messaging queues, email, etc.

In OpenWhisk, interaction with other systems is wrapped in packages, that are a collection of actions explicitly written to interact with a particular system. You can use any programming language and available APIs and drivers to communicate with it. So if you have for example a Java driver for a database, you can write a package to interact with it. Those packages act as Connectors.

In the IBM Cloud, there are packages available to communicate with essential services in the cloud. Most notably, we have

-

the cloud database Cloudant

-

the Kafka messaging system,

-

the enterprise chat Slack

-

many others, some specific to IBM services

You use the Feed mechanism provided by OpenWhisk to hook in those systems.

Application Server

Finally, in JavaEE, everything is managed by Application Servers. They are “the place” where Enterprise Applications are meant to be deployed.

In a sense, OpenWhisk itself replaces the Application Server concept, providing a cloud-based, multi-node, language agnostic execution service.

Using a serverless engine like OpenWhisk, the cloud becomes a transparent entity where you deploy your code. The environment manages the distribution of application in the Cloud.

Note

The problem becomes not to install your code, but to install correctly OpenWhisk. Each component of OpenWhisk must be then appropriately deployed according to the available resources of the Cloud. The installation of OpenWhisk in Cloud is a complex subject, and we will devote a chapter of the book to discuss it.

For now, we have to say that OpenWhisk by itself runs in Docker containers. However, scaling Docker in a Cloud requires you to manage those Docker containers under some supervisor system called Orchestrators.

There are many Orchestrator available. At this stage, OpenWhisk supports:

-

Kubernetes, a widely used orchestration system, initially developed by Google

-

DC/OS, a “cloud” operating system, supporting the management of distributed application and Docker.