Developing Open Serverless Solutions

Copyright © 2019 Michele Sciabarrà. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492046165 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Learning OpenWhisk, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-04610-3

Welcome to the world of Apache OpenWhisk. OpenWhisk is an open source Serverless platform, designed to make easy and fun developing applications in the Cloud.

Serverless does not mean “without the server”, it means “without managing the server”. Indeed we will see how we can build complex applications without having to care of the server (except, of course, when we deploy the platform itself).

A serverless environment is most suitable for a growing class of applications needing processing “in the cloud” that you can split into multiple simple services. It is often referred as a “microservices” architecture.

Typical applications using a Serverless environment are:

services for static or third party websites

voice applications like Amazon Alexa

backends for mobile applications

This chapter is the first of the book, so we start introducing the architecture of OpenWhisk, its, and weaknesses.

Once you have a bird’s eye look to the platform, we can go on, discussing its architecture to explain the underlying magic. We focus on the Serverless Model to give a better understanding of how it works and its constraints. Then we complete the chapter trying to put things in perspective, showing how we got there and its advantages compared with similar architectures already in use: most notably to what is most likely its closest relative: JavaEE.

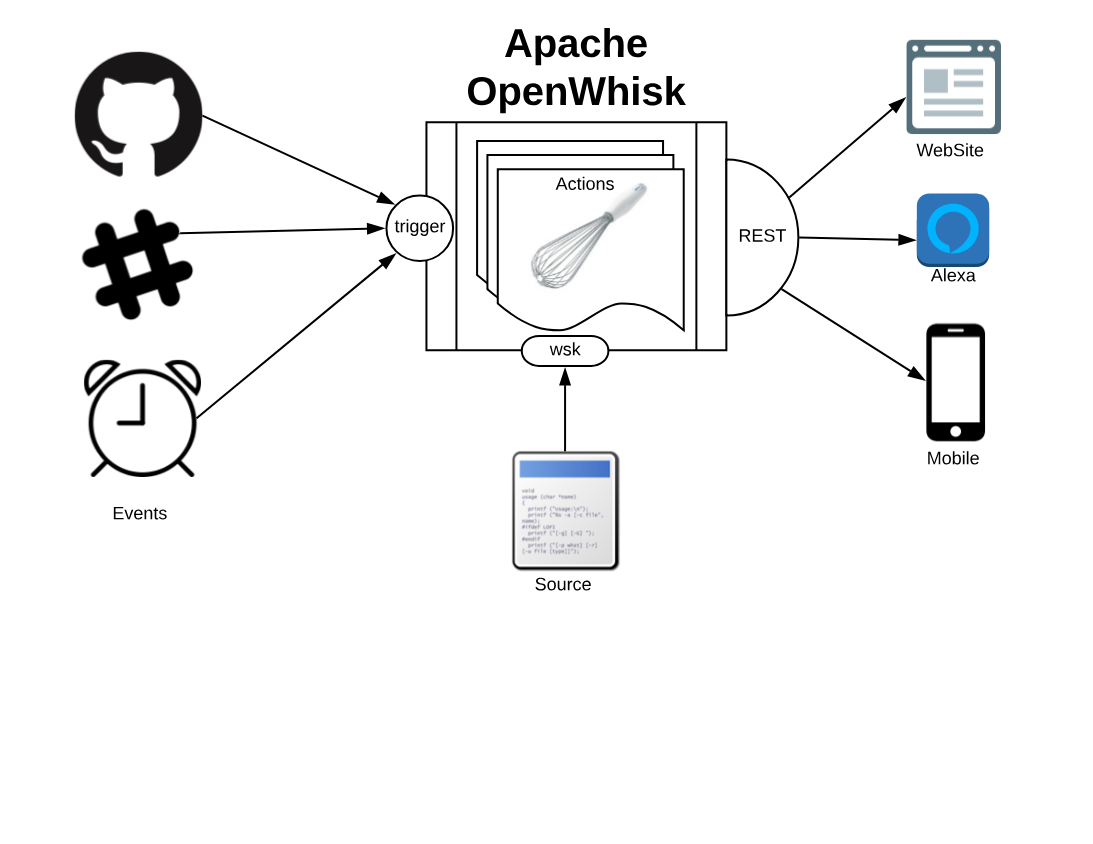

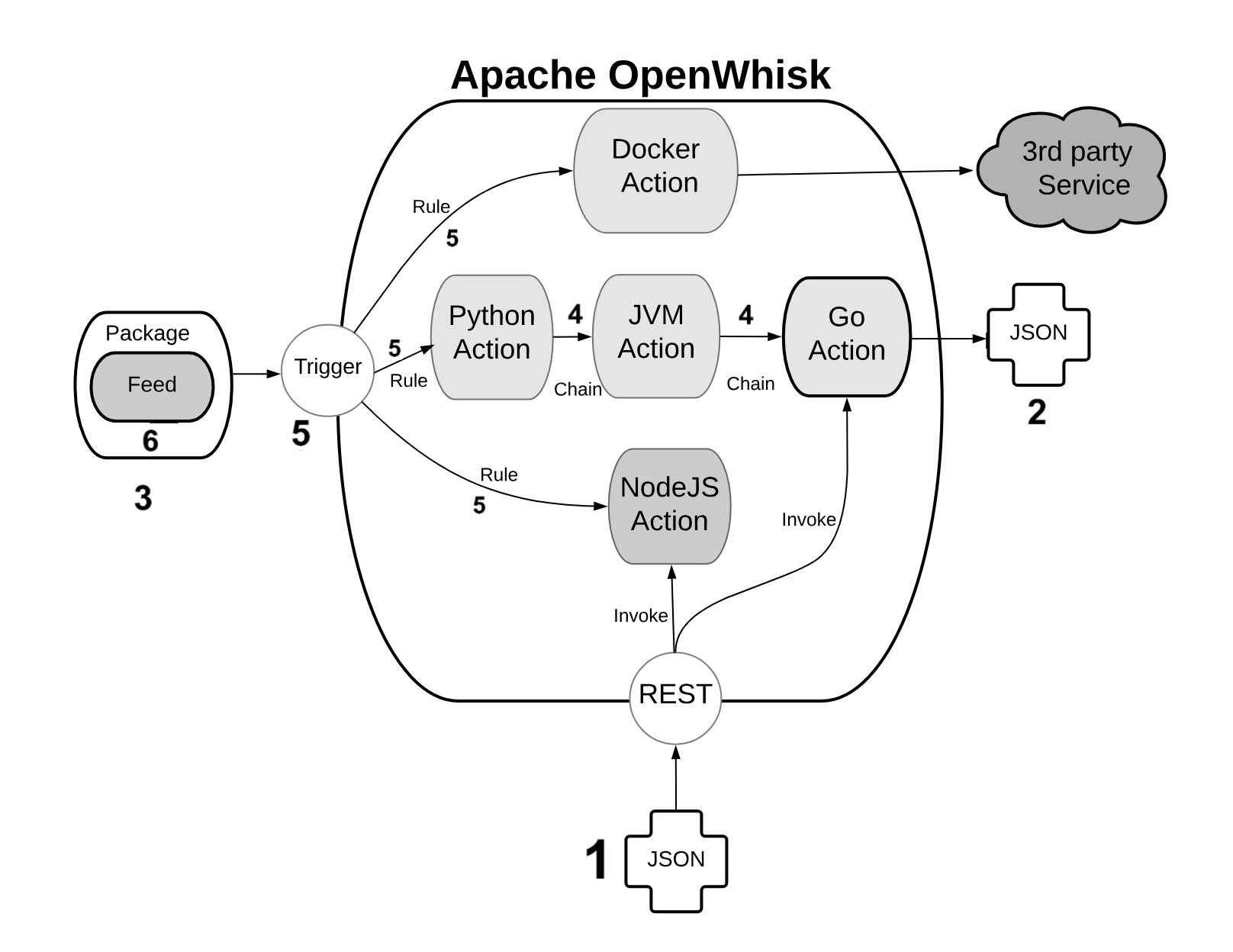

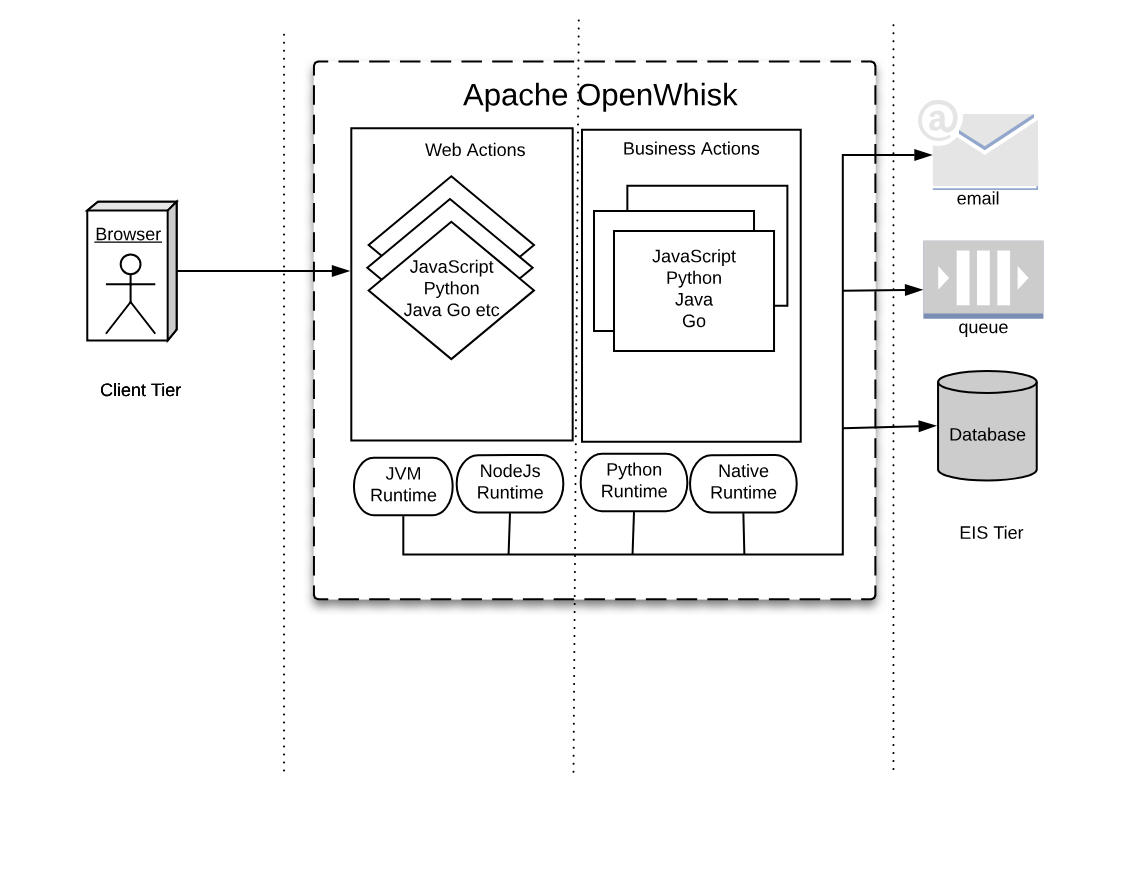

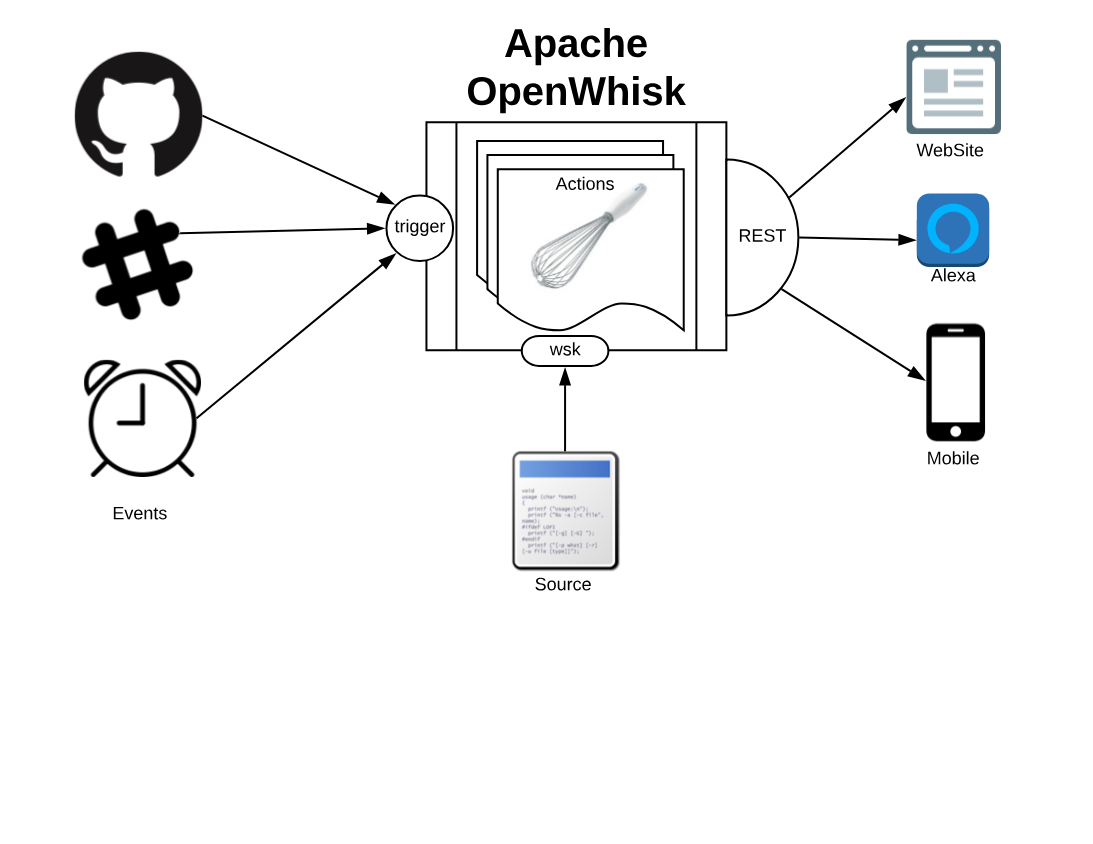

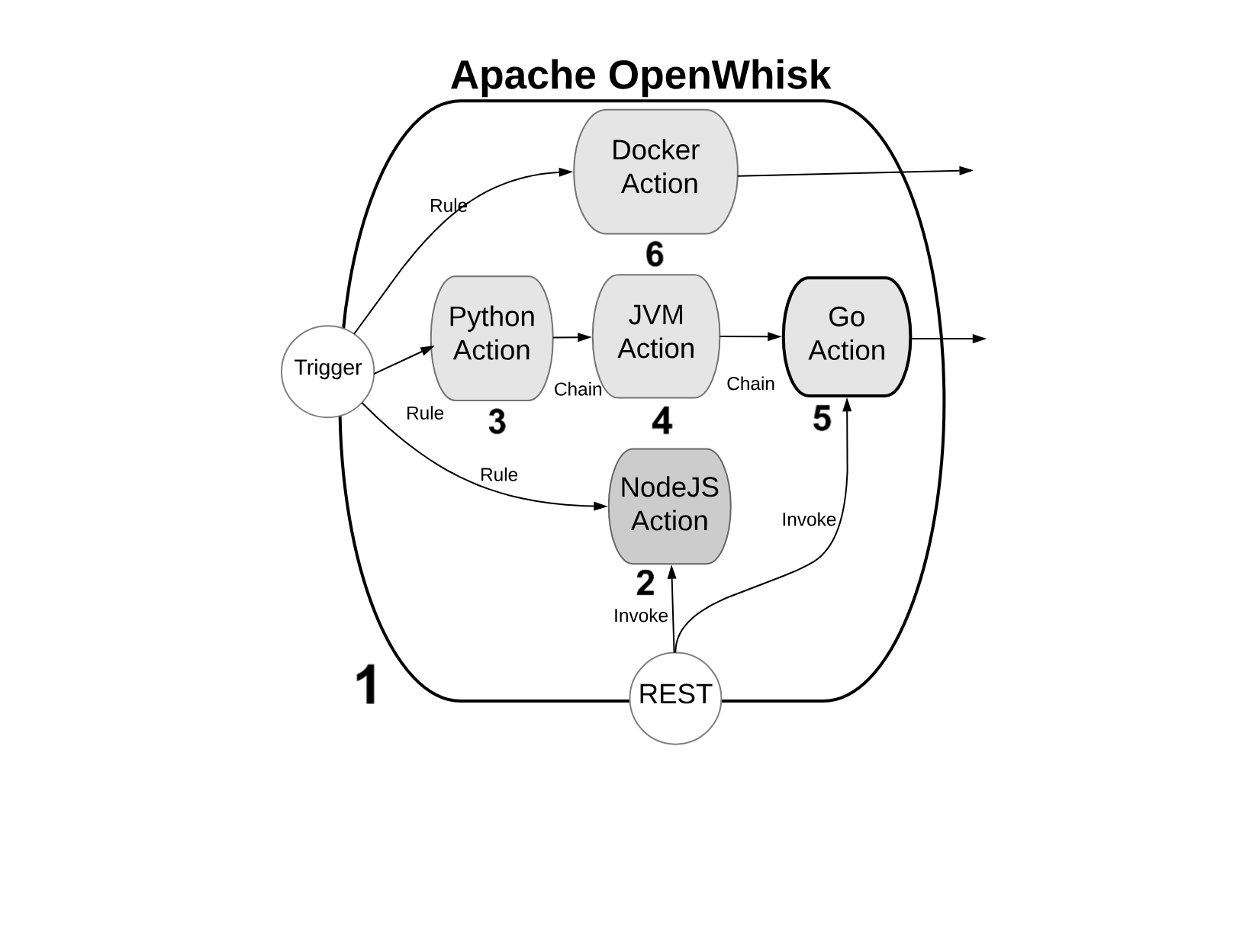

Apache OpenWhisk, shown in Figure Figure 1-1, according to its definition, is a Serverless Open Source Cloud Platform. It works executing functions (called Actions) in response to Events at any scale. Events can be originated by multiple sources, including timers, or websites like Slack or GitHub.

It accepts source code as input, provisioned straight with a command line interface, then delivers services through the web to multiple consumers. Examples of typical consumers are other websites, mobile applications or services based on REST APIs like the voice assistant Amazon Alexa.

Computation in a Serverless environment is generally split in functions. A function is typically a piece of code that will receive input and will provide an output in response. It is important to note that a function is expected to be stateless.

Frequently web applications are stateful. Just think of a shopping cart application for an e-commerce: while you navigate the website, you add your items to the basket, to buy them at the end. You keep a state, the cart.

Being stateful however is an expensive property that limits scalability: you need to provide something to store data. Most importantly, you will need something to synchronize the state between invocations. When your load increase, this “state keeping” infrastructure will limit your ability to grow. If you are stateless, you can usually add more servers.

The OpenWhisk solution, and more widely the solution adopted by Serverless environments is the requirement functions must be stateless. You can keep state, but you will use separate storage designed to scale.

To run functions to perform our computations, the environment will manage the infrastructure and invoke the actions when there is something to do.

In short, “having something to do” is what is called an event. So the developer must code thinking what to do when something happens (a request from the user, a new data is available), and process it quickly. The rest belongs to the cloud environment.

In conclusion, Serverless environments allow you to build your application out of simple stateless functions, or actions as they are called in the context of OpenWhisk, triggered by events. We will see later in this chapter which other constraints those actions must satisfy.

We just saw OpenWhisk from the outside, and now we have an idea of what it does. Now it is time to investigate its architecture, to understand better how it works under the hood.

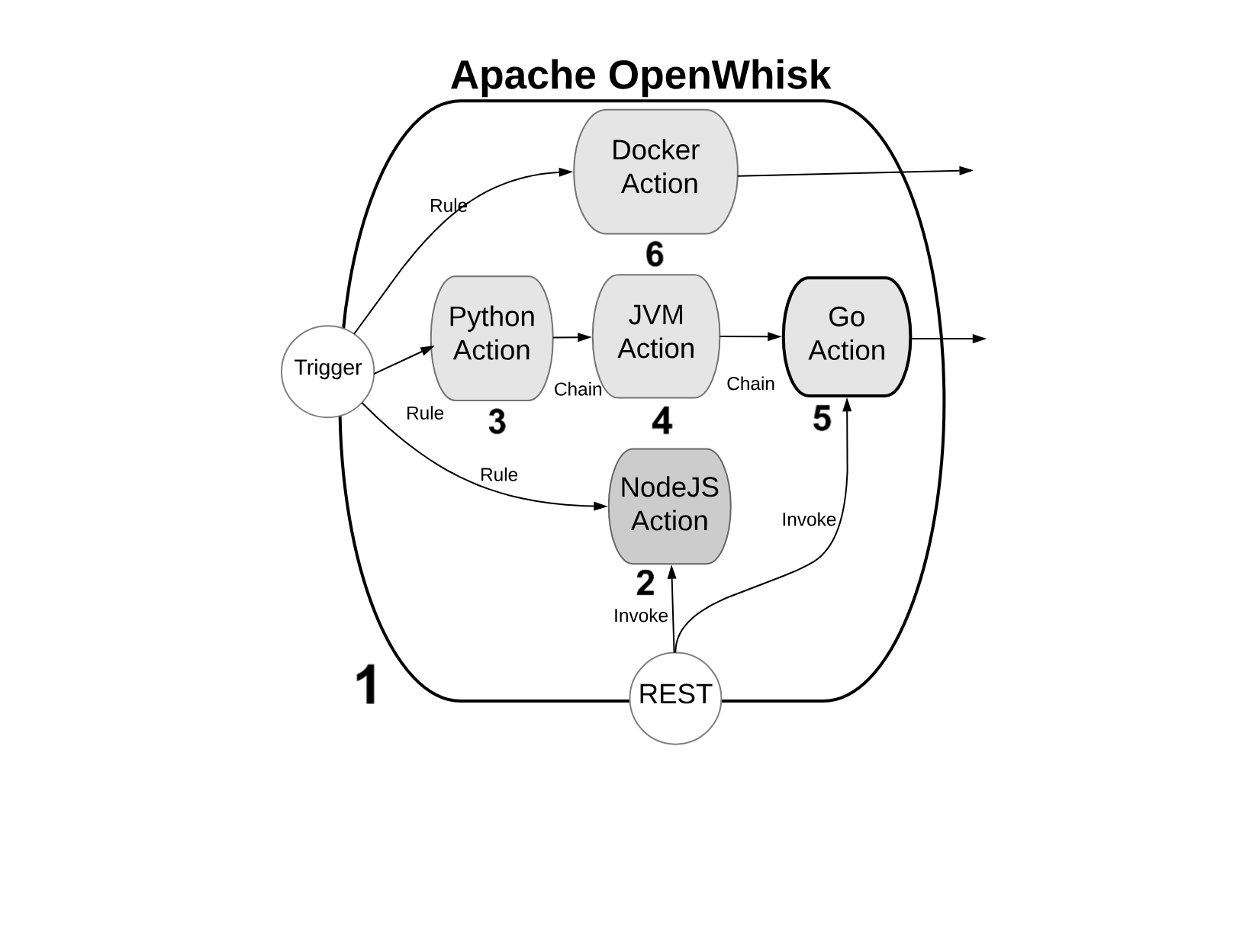

We will refer to the Figure Figure 1-2, with some numbered markers. In the Figure, the big container (see 1) at the center, is OpenWhisk itself. It acts as a container of actions. We will see later what an action and what the container is.

Actions, as you can see, can be developed in many programming languages. We will discuss the differences among the various options in the next paragraph.

For the architect, you can consider it as an opaque system that executes those actions in response to events.

It is essential to know the “container” will schedule them, creating and destroying actions that are not needed, and it will also scale them, creating duplicates in response to an increase in load.

You can write actions in many programming languages. Probably the more natural to use are interpreted programming languages: like JavaScript (see 2) (actually, Node.js) or Python (see 3). Those programming languages are interpreted and give an immediate feedback since you can execute them without compilation. They are also generally of higher level, hence more comfortable to use (while the drawback is usually they are slower than compiled languages). Since OpenWhisk is a highly responsive system, where you can immediately run your code in the cloud, probably the majority of the developers prefer to use those “interactive” programming languages.

The “default” language for OpenWhisk is indeed Javascript. However other languages are also first class citizen. While Javascript is the more commonly used, nothing in OpenWhisk favors it over other languages.

In addition to purely interpreted (or compiled-on-the-fly languages, as it is correct to say), you can use also pre-compiled interpreted languages, like the languages of the Java family. Java, Scala and Kotlin (see 4) are the more common programming languages of this family. They run on the Java Virtual Machine, and they are distributed not in source form but an intermediate form. The developer must create a “jar” file to run the action. This jar includes the so-called “bytecode” that OpenWhisk will execute when it will be deployed . A Java Virtual Machine is the actual executor of the action.

Finally, in OpenWhisk you can use compiled languages, producing a binary executable that runs on “bare metal” without interpreters or virtual machines. Examples of those binary languages are Swift, Go or the classical C/C++, see (see 5).

OpenWhisk supports out-of-the-box Go and Swift. You need to send the code of an action compiled in Linux elf format for the amd64 processor architecture, so a compilation infrastructure is needed. However today, with the help of Docker, is not complicated to install on any system the necessary toolchain for the compilation.

Finally, you can use in OpenWhisk any arbitrary language or system that can you can package like a Docker image (see 6) and that you can publish on Docker Hub: OpenWhisk allows to retrieve such an image and run it, as long as you follow its conventions. We will discuss this in the chapter devoted to native actions.

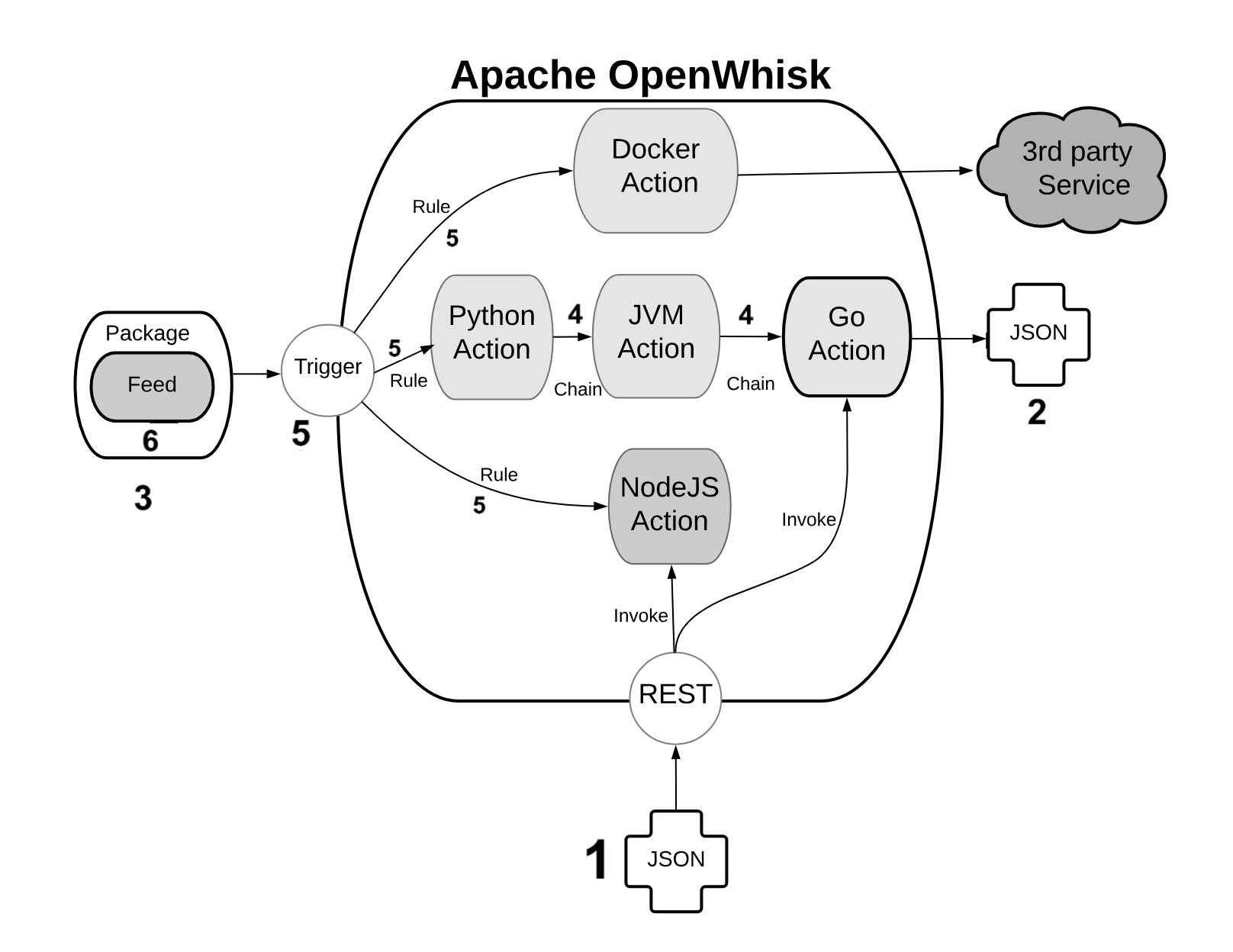

OpenWhisk applications are a collection of actions. We already saw the available type of actions. Now let’s see in Figure Figure 1-3 how they are assembled to build applications.

An action is a piece of code, written in one of the supported programming languages, that you can invoke. On invocation, the action will receive some information as input (see 1).

To standardize parameter passing among multiple programming languages, OpenWhisk uses the widely supported JSON format, since it is pretty simple, and there are libraries to encode and decode this format available basically for every programming language.

The parameters are passed to actions as a JSON string, that the action receives when it starts, and it is expected to process. At the end of the processing, each action must produce its result that is then returned also as a JSON string (see 2).

You can group actions in packages (see 3). A package acts as a unit of distribution. You can share a package with others using bindings. You can also customize a package providing parameters that are different for each binding.

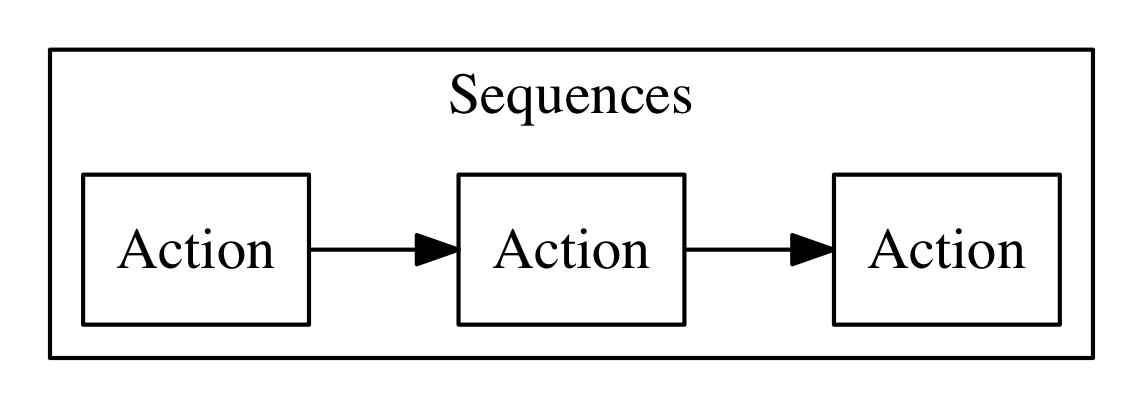

Actions can be combined in many ways. The simplest form of combination is chaining them in sequences (see 4)

Chained actions will use as input the output of the preceding actions. Of course, the first action of a sequence will receive the parameters (in JSON format), and the last action of the sequence will produce the final result, as a JSON string.

However, since not all the flows can be implemented as a linear pipeline of input and output, there is also a way to split the flow of an action in multiple directions.

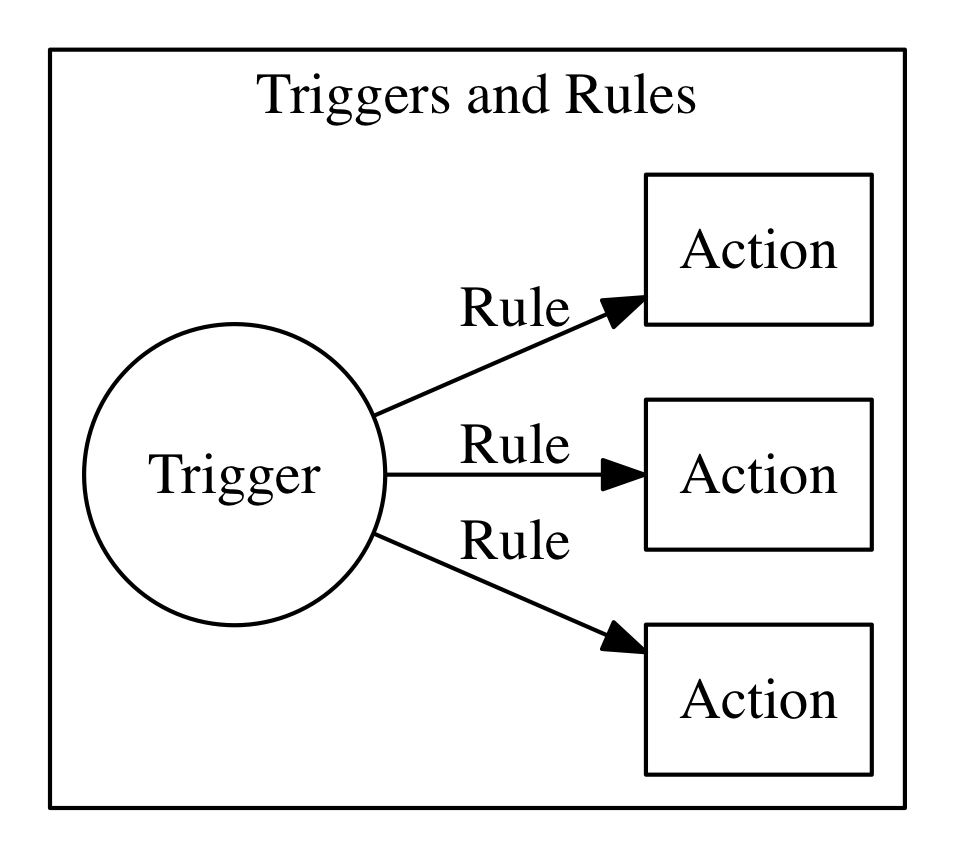

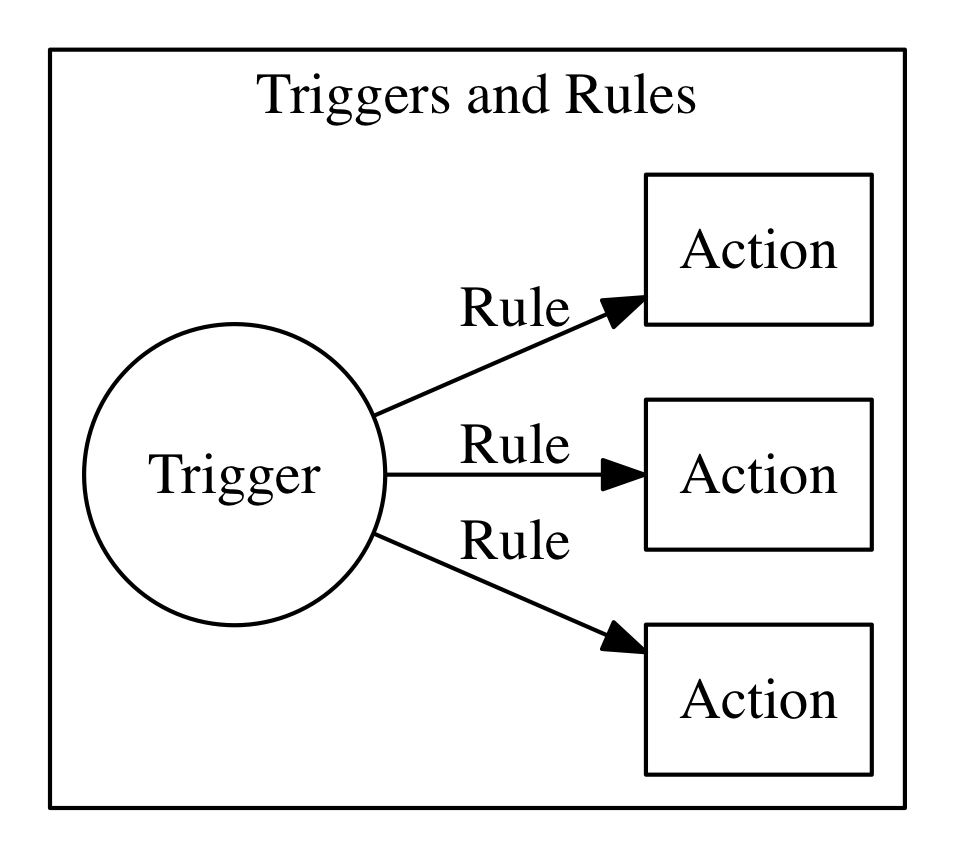

This feature is implemented using triggers and rules (see 5).

A trigger is merely a named invocation. You can create a trigger, but by itself a trigger does nothing. However, you can then associate the trigger with multiple actions using Rules.

Once you have created the trigger and associated some action with it, you can fire the trigger providing parameters.

Triggers cannot be part of a package. They are something top-level. They can be part of a namespace, however, discussed in the following paragraph.

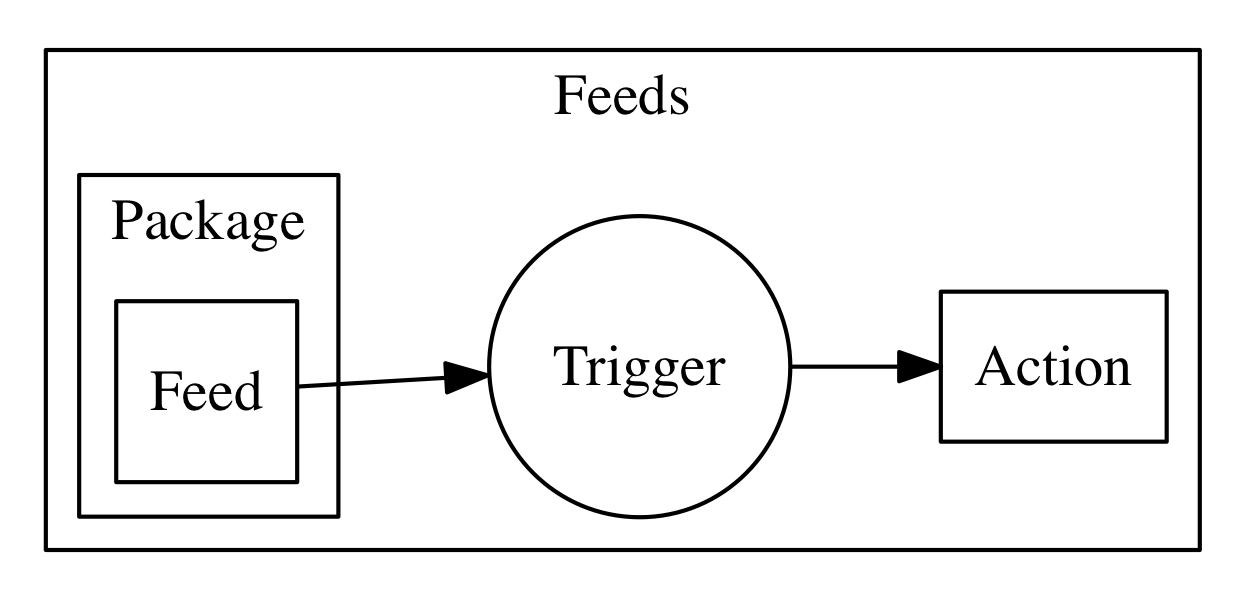

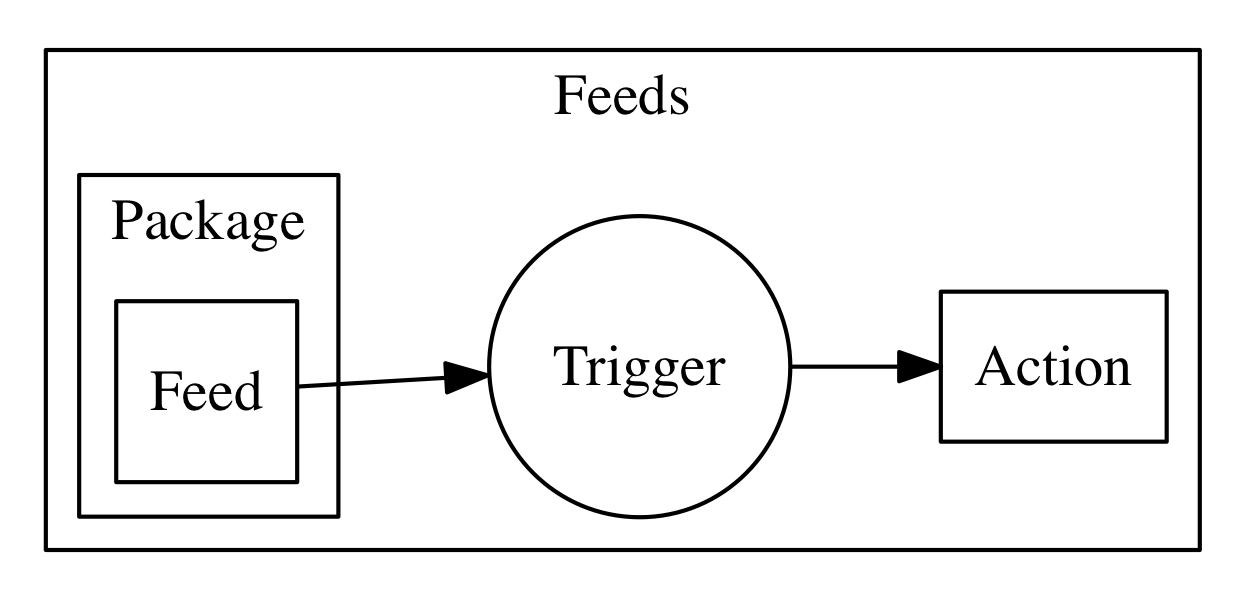

The connection between actions and triggers is called a feed (see 6). A feed is an ordinary action that must follow an implementation pattern. We will see in the chapter devoted to the design pattern. Essentially it must implement an observer pattern, and be able to activate a trigger when an event happens.

When you create an action that follows the feed pattern (and that can be implemented in many different ways), that action can be marked as a feed in a package. In this case, you can combine a trigger and feed when you deploy the application, to use a feed as a source of events for a trigger (and in turn activate other actions).

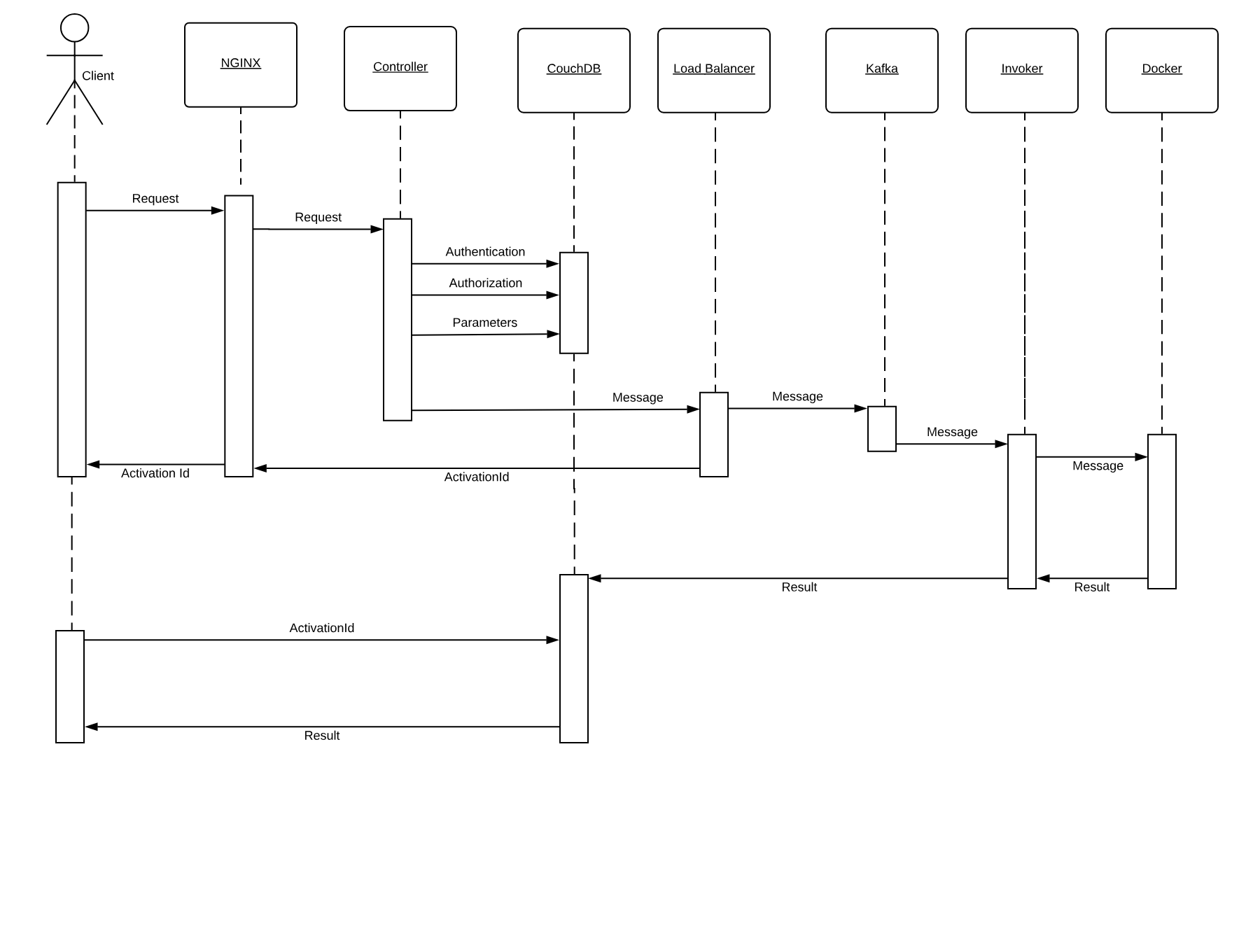

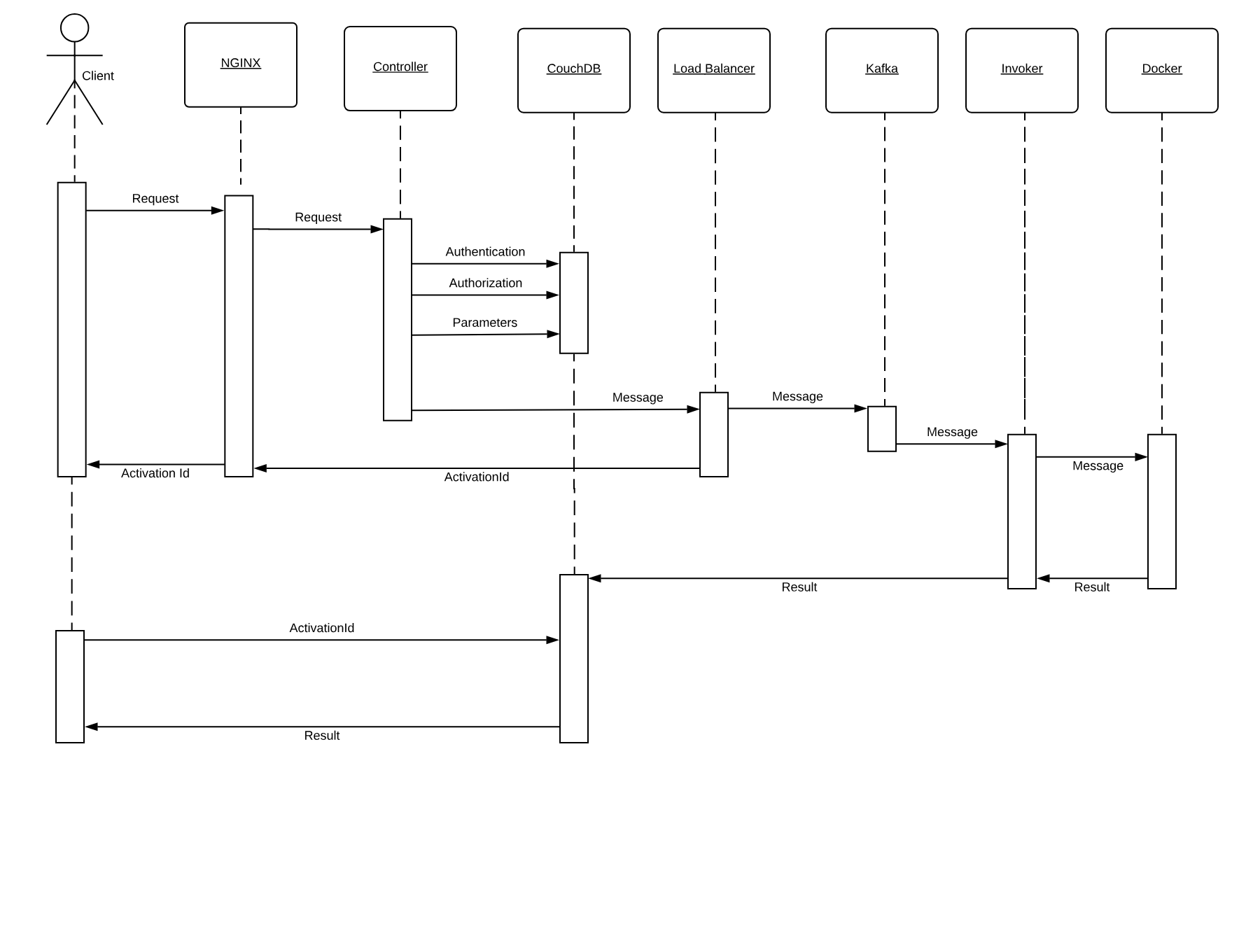

Once it is clear what are the components of OpenWhisk, it is time to see what are the actual steps that are performed when it executes an action.

As we can see the process is pretty complicated. We are going to meet some critical components of OpenWhisk. OpenWhisk is “built on the shoulder of giants,” and it uses some widely known and well developed open source projects.

More in detail it includes:

NGINX, a high-performance web server and reverse proxy.

CouchDB, a scalable, document-oriented, NO-SQL Database.

Kafka, a distributed, high performing, publish-subscribe messaging system.

Docker, an environment to manage execution of applications in an efficient but constrained, virtual-machine like environment.

Furthermore, OpenWhisk can be split into some components of its own:

the Controller, managing the execution of actions

the Load Balancer, distributing the load

the Invoker, actually executing the actions

In Figure Figure 1-4 we can see how the whole processing happens. We are going to discuss it in detail, step by step.

Basically, all the processing done in OpenWhisk is asynchronous, so we will go into the details of an asynchronous action invocation. Synchronous execution fires an asynchronous execution and then wait for the result.

Everything starts when an action is invoked. There are different ways to invoke an action:

from the Web, when the action is exposed as Web Action

when another action invokes it through the API

when a trigger is activated and there is a rule to invoke the action

from the Command Line Interface

Let’s call the client the subject who invokes the action. OpenWhisk is a RESTful system, so every invocation is translated in an https call and hits the so-called “edge” node.

The edge is actually the web server and reverse proxy Nginx. The primary purpose of Nginx is implementing support for the “https” secure web protocol. So it deploys all the certificates required for secure processing. Nginx then forwards the requests to the actual internal service component, the Controller.

The Controller, that is implemented in Scala, before effectively executing the action, performs pretty complicated processing.

It needs to be sure it can execute the action. Hence the need to authenticate the requests, verifying if the source of the request is a legitimate subject.

Once the origin of the request has been identified, it needs to be authorized, verifying that the subject has the appropriate permissions.

The request must be enriched with all the default parameters that have been configured. Those parameters, as we will see, are part of the action configuration.

To perform all those steps the Controller consults the database, that in OpenWhisk is CouchDB.

Once validated and enriched, the action is now is ready to be executed, so it is sent to the next component of the processing, the Load Balancer.

Load Balancer job, as its name states, is to balance the load among the various executors in the system, which are called in OpenWhisk Invokers.

We already saw that OpenWhisk executes actions in runtimes, and there are runtimes available for many programming languages. The Load Balancer keeps an eye on all the available instances of the runtime, checks its status and decide which one should be used to serve the new action requested, or if it must create a new instance.

We got to the point where the system is ready to invoke the action. However, you can not just send your action to an Invoker, because it can be busy serving another action. There is also the possibility that an invoker crashed, or even the whole system may have crashed and is restarting.

So, because we are working in a massively parallel environment that is expected to scale, we have to consider the eventuality we do not have the resources available to execute the action immediately. Hence we have to buffer invocations.

The solution for this purpose is using Kafka. Kafka is a high performing “publish and subscribe” messaging system, able to store your requests, keep them waiting until they are ready to be executed. The request is turned in a message, addressed to the invoker the Load Balancer chose for the execution.

Each message sent to an Invoker has an identifier, the ActivationId. Once the message has been queued in Kafka, the ActivationId is sent back as the final answer of the request to the client, and the request completes.

Because as we said the processing is asynchronous, the Client is expected to come back later to check the result of the invocation.

The Invoker is the critical component of OpenWhisk and it is in charge of executing the Actions. Actions are actually executed by the Invoker creating an isolated environment provided by Docker.

Docker can create execution environments (called “Containers”) that resemble an entire operating system, providing everything code written in any programming language needs to run.

In a sense, an environment provided by Docker looks like, as seen by action, to an entire computer for it (just like a Virtual Machine). However, execution within containers is much more efficient than VMs, so they are used in preference to actual emulated environments.

It would be safe to say that, without containers, the entire concept of a Serverless Environment like OpenWhisk executing actions as separate entities, would not have been possible to implement.

Docker actually uses Images as the starting point for creating containers where it executes actions. A runtime is really a Docker image. The Invoker launches a new Image for the chosen runtime then initialize it with the code of the action.

OpenWhisk provides a set of Docker Images including support for the various languages, and the execution logic to accept the initialization: JavaScript, Python, Java, Go, etc.

Once the runtime is up and running, the invoker passes the whole action requests that have been constructed in the processing so far. Also, Invokers will take care of managing and storing logs to facilitate debugging.

Once OpenWhisk completes the processing, it must store the result somewhere. This place is again CouchDB (where also configuration data are stored). Each result of the execution of an action is then associated with the ActivationId, the one that was sent back to the client. Thus the client will be able to retrieve the result of its request querying the database with the id.

As we already said, the processing described so far is asynchronous. This fact means the client will start a request and forget. Well, it will not leave it behind entirely, because it returns an activation id as a result of an invocation. As we have seen so far, the activation id is used to associate the result in the database after the processing.

So, to retrieve the final result, the client will have to perform a request again later, passing the activation id as a parameter. Once the action completes, the result, the logs, and other information are available in the database and can be retrieved.

Synchronous processing is available in addition to the asynchronous one. It primarily works in the same way as the asynchronous, except the client will block waiting for the action to complete and retrieve the result immediately.

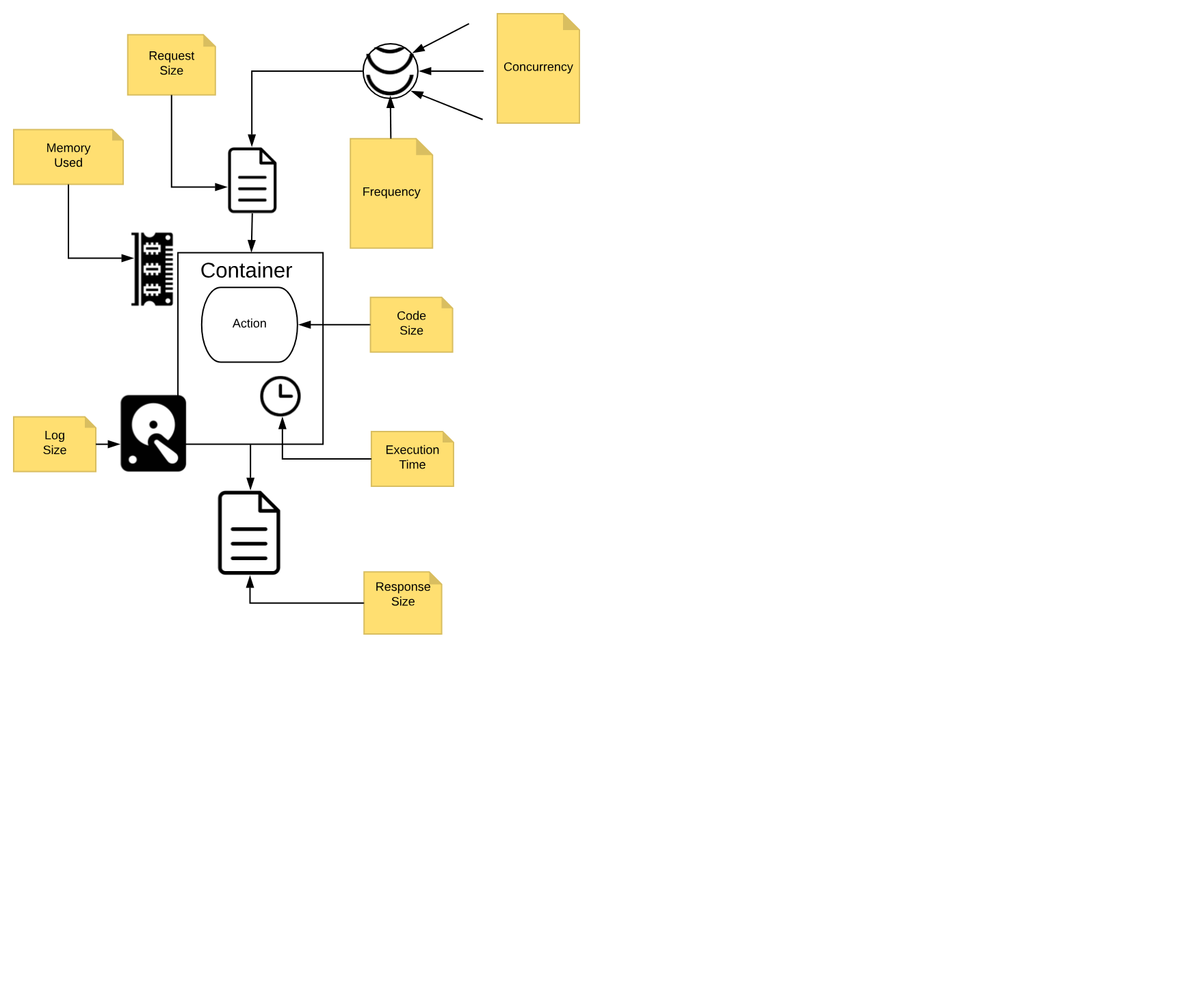

The OpenWhisk architecture and its way of operation mandate that, When you develop Serverless applications, you have to abide by some constraints and limitations.

We call those constraints execution model, and we are going to discuss it in detail.

You need to think to your application as decomposed as a set of actions, collaborating each other to reach the purpose of the application.

It is essential to keep in mind that each action, running in a Serverless environment, will be executed within certain limits, and those limits must be considered when designing the application.

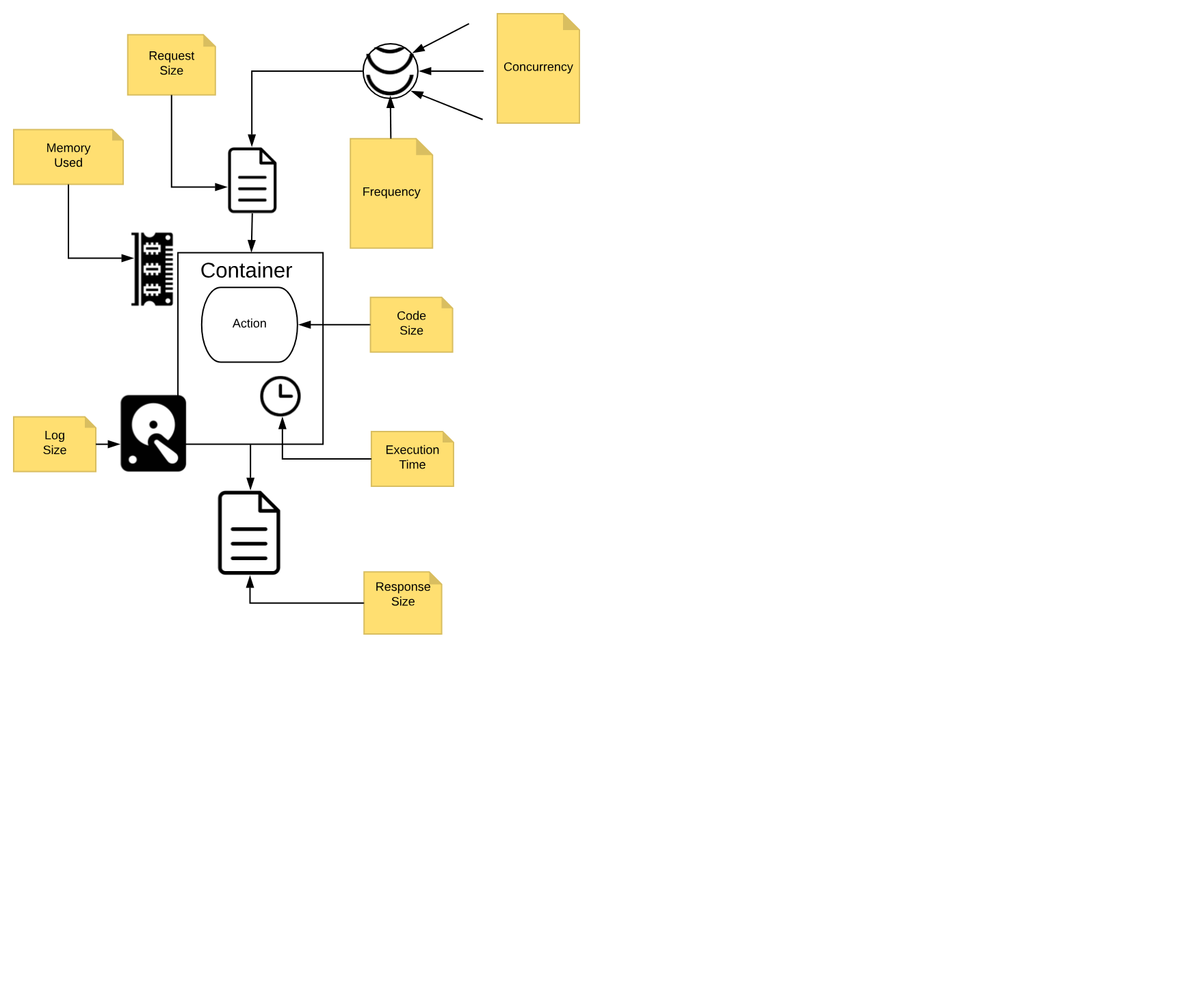

In Figure Figure 1-5 are depicted the significant constraints an action is subject.

All the constraints have some value in term of time or space, either timeout, frequency, memory, size of disk space. Some are configurable; others are hardcoded. The standard values (that can be different according to the particular cloud or installation you are using) are:

execution time: max 1 minute per action (configurable)

memory used: max 256MB per action (configurable)

log size: max 10MB per action (configurable)

code size: max 48MB per action (fixed)

parameters: max 1MB per action (fixed)

result: max 1MB per action (fixed)

Furthermore, there are global constraints:

concurrency: max 100 concurrent activations can be queued at the same time (configurable)

frequency: max 120 activations per minute can be requested (configurable)

Global constraints are actually per namespace. Think to a namespace as the collection of all the OpenWhisk resources assigned to a specific user, so it is practically equivalent to a Serverless application, since it is split into multiple entities.

Let’s discuss more in detail those constraints.

As already mentioned, each action must be a function, invoked with a single input and must produce a single output.

The input is a string in JSON format. The action usually deserializes the string in a data structure, specific to the programming language used for the implementation.

The runtime generally performs the deserialization, so the developer will receive an already parsed data structure.

If you use dynamic languages like Javascript or Python, usually you receive something like a Javascript object or a Python dictionary, that can be efficiently processed using the feature of the programming language.

If you use a more statically typed language like Java or Go, you may need to put more effort in decoding the input. Libraries for performing the decoding task are generally readily available. However, some decoding work may be necessary to map the generally untyped arguments to the typed data structure of the language.

The same holds true for returning the output. It must be a single data structure, the programming language you are using can create, but it must be serialized back in JSON format before being returned. Runtimes also usually take care of serializing data structures back in a string.

Everything in the Serverless environment is activated by events. You cannot have any long running process. It is the system that will invoke actions, only when they are needed.

For example, an event is a user that when is browsing the web opens the URL of a serverless application. In such a case, the action is triggered to serve it.

However, this is only one possible event. Other events include for example a request, maybe originated by another action, that arrives on a message queue.

Also, database management is event-driven. You can perform a query on a database, then wait until an event is triggered when the data arrives.

Other websites can also originate events. For example, you may receive an event:

when someone pushes a commit on GitHub

when a user interacts with Slack and sends a message

when a scheduled alarm is triggered

when an action update a database

etc.

Actions are executed in Docker containers. As a consequence (by Docker design) file system is ephemeral. Once a container terminates, all the data stored on the file system will be removed too.

However, this does not mean you cannot store anything on files when using a function. You can use files for temporary data while executing an application.

Indeed a container can be used multiple times, so for example, if your application needs some data downloaded from the web, an action can download some stuff it makes available to other actions executed in the same container.

What you cannot assume is that the data will stay there forever. At some point in time, either the container will be destroyed or another container will be created to execute the action. In a new container, the data you downloaded in a precedent execution of the action will be no more available.

In short, you can use local storage only as a cache for speed up further actions, but you cannot rely on the fact data you store in a file will persist forever. For long-term persistence, you need to use other means. Typically a database or another form of cloud storage.

It is essential to understand that action must execute in the shortest time possible. As we already mentioned, the execution environment imposes time limits on the execution time of an action. If the action does not terminate within the timeout, it will be aborted. This fact is also true for background actions or threads you may have started.

So you need to be well aware of this behavior and ensure your code will not keep going for an unlimited amount of time, for example when it gets larger input. Instead, you may sometimes need to split the processing into smaller chunks and ensure the execution time of your action will stay within limits.

Also usually the billing charge is time-dependent. If you run your application in a cloud provider supporting OpenWhisk, you are charged for the time your action takes. So faster actions will result in lower cost. When you have millions of actions executed, a few milliseconds speedier action can sum up in significant savings.

Note also that actions are not ordered. You cannot rely on the fact action is invoked before another. If you have action A at time X and action B at time Y, with X < Y, action B can be executed before A.

As a consequence, if the action has a side effect, for example writing in the database, the side effect of action A may be applied later than the action B. Furthermore, there is not even any guarantee that an action will be executed entirely before or after another action. They may overlap in time.

So for example when you write in a database you must be aware that while you are writing in it, and before you have finished, another action may start writing in it too. So you have to provide your transaction support.

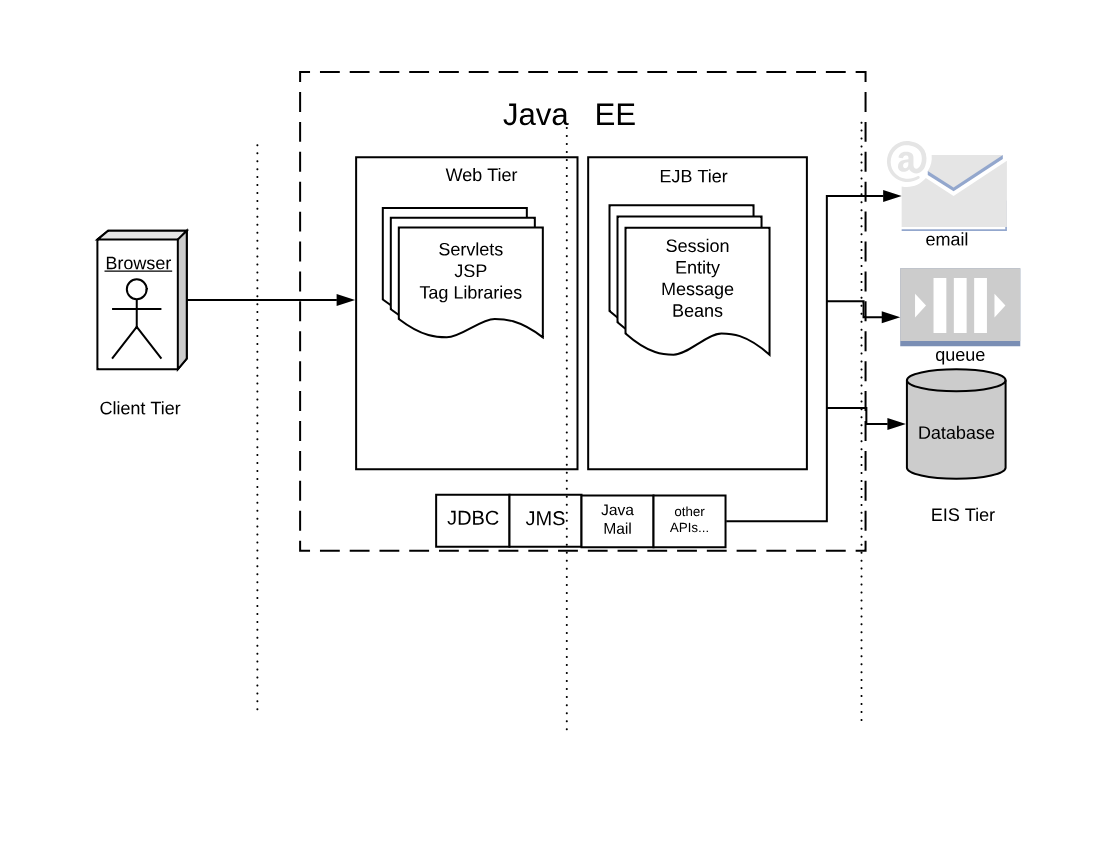

The Serverless Architecture looks brand new, however it shares concepts and practices with existing architectures. In a sense, it is an evolution of those historical architectures.

Of course, every architectural decision made in the past has been adapted to emerging technologies, most notably virtualization and containers. Also, the requirements of the Cloud era impose scalability virtually unlimited.

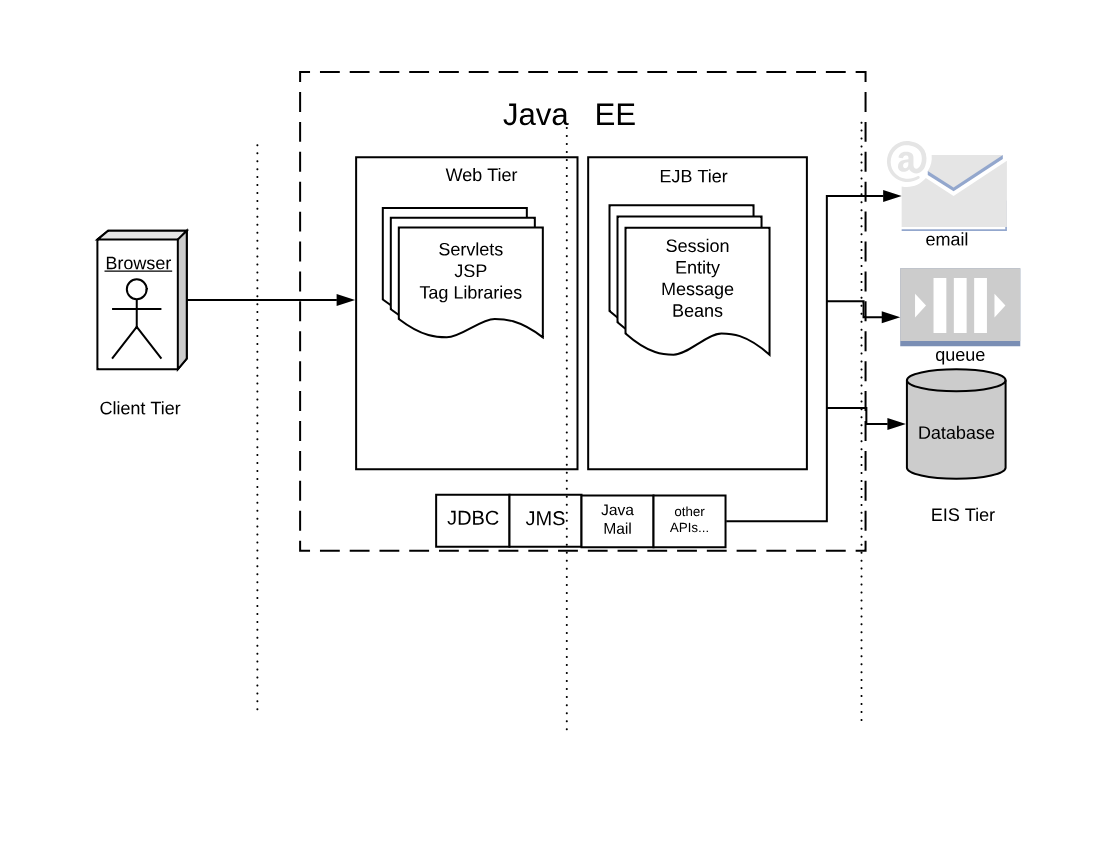

To better understand the genesis and the advantages of the Serverless Architecture, it makes sense to compare OpenWhisk architecture it with another essential historical precedent that is currently in extensive use: the Architecture of Java Enterprise Edition, or JavaEE.

The core idea behind JavaEE was allowing the development of large application out of small, manageable parts. It was a technology designed to help application development for large organizations, using the Java programming language. Hence the name of Java Enterprise Edition.

At the time of the creation of JavaEE, everything was based on the Java programming language, or more specifically, the Java Virtual Machine. Historically, when JavaEE was created Java was the only programming language available for building large, scalable applications (meant to replace C++). Scripting languages like Python were at the time considered toys and not in extensive use.

To facilitate the development of that vast and complex application, JavaEE provided a productive (and complicated) infrastructure of services.

To use them, JavaEE offered many different types of components, each one deployable separately, and many ways to let the various part to communicate with each other.

Those services were put together and made available through the use of Application Server. JavaEE itself was a specification.

The actual implementation was a set of competing products. The most prominent names in the world of application servers that are still in broad use today are Oracle Weblogic and IBM WebSphere.

If we look at the classical JavaEE architecture we can quickly identify the following tiers:

The client (front end) tier

The web (back-end) tier

The EJB (business) tier

The EIS (integration) tier

The following ideas characterize it:

Application is split into discrete components, informally called beans.

Components are executed in (Java-based) containers.

Interface to the external world is provided by connectors.

In JavaEE, we have different types of components.

The client tier is expected to implement the application logic at the client level. Historically Java was used to implement applet, small java components that can be downloaded and run in the browser. Javascript, CSS, and HTML nowadays entirely replace those web components

In the web tier, the most crucial kind of components are the servlets. They are further specialized in JSP, tag libraries, etc. Those components define the web user interface at the server level.

The so-called business logic, managing data and connection to other “enterprise systems” is expected to be implemented in the Business Tier using the so-called EJB (Enterprise Java Beans). There were many flavors of EJB, like Entity Beans, Session Beans, Message Beans, etc.

Each component in JavaEE is a set of Java classes that must implement an API. The developer writes those classes and then deliver them to the Application Server, that loads the components and run them in their containers.

Furthermore, application servers also provide a set of connectors to interface the application with the external world, the EIS tier. There were connectors, written for Java, allowing to interface to virtually any resource of interest,

The more common in JavaEE are connectors to:

databases

message queues

email and other communication systems

In the JavaEE world, Application Servers provided the implementation of all the JavaEE specification, and included APIs and connectors, to be a one-stop solution for all the development needs of enterprises.

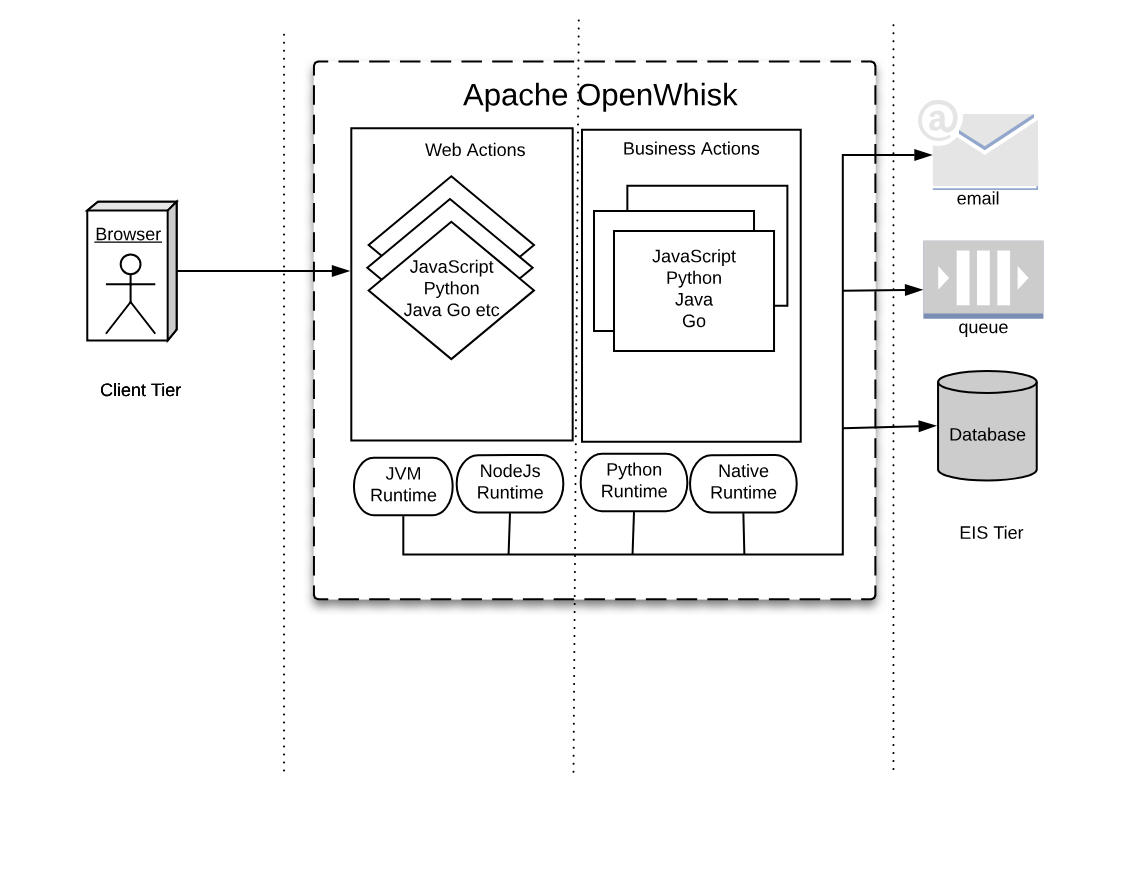

For many reasons, the architecture of Serverless application and OpenWhisk can be seen as an evolution of JavaEE. Everything starts from the same basic idea: split your application into many small, manageable parts, and provide a system to quickly put together all those pieces.

However, the technological landscape driving the development of Serverless environment is different than the one driving JavaEE development. In our brave new world, we have:

applications are spread among multiple servers in the cloud, requiring virtually infinite scalability

numerous programming languages, including scripting languages, are in extensive use and must be usable

virtual machine and container technologies are available to wrap and control the execution of programs

HTTP can be considered a standard transport protocol

JSON is simple and widely used to be usable as a universal exchange format

Now, let’s compare JavaEE with the OpenWhisk architecture in Figure Figure 1-7. The Figure is intentionally similar to the Figure Figure 1-6, to highlight similarities and differences.

As you can see in the Figure, we can recognize web tier and a business tier also in OpenWhisk, in addition to a client and an integration tier.

While there is not a formal difference between the two tiers, in practice we have actions directly exposed to the web (web actions) and actions that are not.

Web Actions can be considered to be the web tier. Those actions which are meant to serve events, either coming from web actions or triggered by other services in the infrastructure, can be considered “Business Actions,” defining a “Business Tier.”

In JavaEE, everything runs in the Java Virtual Machine, and everything must be coded in Java (or any language that can generate JVM-compatible byte-code).

In OpenWhisk, you can code applications in multiple programming languages. We use their runtimes as equivalents of the Java Virtual Machine. Furthermore, those runtimes are wrapped in Docker containers to provide isolation and control over resource usage.

Hence you can write your components in any (supported) language you like. You are no more confined to write your application solely for the JVM. However, a JVM runtime is available, so you can still use Java and its family of languages if you like.

You can now write your code for the JavaScript Virtual Machine, more commonly referred to as NodeJs .

Under the hood, Nodes it is an adaptation of the V8 Javascript interpreter that powers the Chrome Browser. It is a fast executor of the javascript language, which also does complicated things like compiling on-the-fly to native code.

If you choose to use the Python programming languages, you are also using its interpreter. Python has many available interpreters, one being the move widely used CPython, but there is also other available, like Pypy. The JVM can even execute Python.

Furthermore, you may choose not to use a virtual machine at all, but write your application in a language producing native executables like Swift or Go. In the Serverless world, it is becoming to become a popular choice. As long as you compile your application for Linux and AMD64, you can use it for OpenWhisk.

In JavaEE, you have APIs available to interact with the rest of the world, written in Java itself. Basically, the JavaEE model is , and every interesting resource for writing applications has been adapted to be used by Java.

In OpenWhisk, you have first and before all only one API, available for all the supported programming languages. This API is the OpenWhisk API itself, and it is a RESTful API. You can invoke it over HTTP using JSON as an interchange format.

This API can even be invoked directly just using an HTTP library, reading and writing JSON strings. However, are available wrappers for all the supported programming languages to use it efficiently. This API acts as glue for the various components in OpenWhisk.

All the communication between the different parts in OpenWhisk are performed in JSON over HTTP.

In JavaEE, you have connectors for each external system you want to communicate with, primarily drivers. For example, if you’re going to interact with an Oracle database you need an Oracle JDBC driver, to communicate with IBM DB2 you need a specify DB2 JDBC driver, etc. The same holds true for messaging queues, email, etc.

In OpenWhisk, interaction with other systems is wrapped in packages, that are a collection of actions explicitly written to interact with a particular system. You can use any programming language and available APIs and drivers to communicate with it. So if you have for example a Java driver for a database, you can write a package to interact with it. Those packages act as Connectors.

In the IBM Cloud, there are packages available to communicate with essential services in the cloud. Most notably, we have

the cloud database Cloudant

the Kafka messaging system,

the enterprise chat Slack

many others, some specific to IBM services

You use the Feed mechanism provided by OpenWhisk to hook in those systems.

Finally, in JavaEE, everything is managed by Application Servers. They are “the place” where Enterprise Applications are meant to be deployed.

In a sense, OpenWhisk itself replaces the Application Server concept, providing a cloud-based, multi-node, language agnostic execution service.

Using a serverless engine like OpenWhisk, the cloud becomes a transparent entity where you deploy your code. The environment manages the distribution of application in the Cloud.

The problem becomes not to install your code, but to install correctly OpenWhisk. Each component of OpenWhisk must be then appropriately deployed according to the available resources of the Cloud. The installation of OpenWhisk in Cloud is a complex subject, and we will devote a chapter of the book to discuss it.

For now, we have to say that OpenWhisk by itself runs in Docker containers. However, scaling Docker in a Cloud requires you to manage those Docker containers under some supervisor system called Orchestrators.

There are many Orchestrator available. At this stage, OpenWhisk supports:

Kubernetes, a widely used orchestration system, initially developed by Google

DC/OS, a “cloud” operating system, supporting the management of distributed application and Docker.

The goal of this chapter is to introduce the development of OpenWhisk applications using JavaScript (and NodeJS) as a programming language, using a command line interface. The reader will get a feeling of how Serverless development works.

For this purpose, we are going to implement step by step a simple application with OpenWisk: a contact form for your website.

You cannot store contacts in your static website; you need some server logic to save them. Furthermore, you may want some logic to validate the data (since the user can disable javascript in their browser) and additionally receive emails notifying of what is going on on the website.

In this introduction to OpenWhisk, we are going to assume our static website is stored on the Amazon AWS Cloud, but we will implement our commenting functions the IBM Cloud, that offers OpenWhisk out of the box.

OpenWhisk is an open source project meant to be cloud-independent, and you can adopt it without being constrained to one single vendor.

Let’s assume we already have a website, built with a static website generator. Creating a site statically was the standard at the beginning of the web. Later, this practice was replaced by the use of a Content Management Systems; however it trendy again today. Indeed, static websites are fast, can be built with the maximum flexibility and there are plenty of tools to create them. Once you have a static site you can publish it on many different platforms offering static publishing. For example, a popular option is AWS S3.

However, usually, not everything in a website can be static. For example, you may need to allow your website visitors to contact you. Of course, you may then want to store the contacts in a database, to manage the data with a CRM application.

Before Serverless environments were available, the only way to enhance a static website with server-side logic was to provision a server, typically a virtual machine, deploy a web server with server-side programming support, then add a database, and finally implement the function you need using a server-side programming language, like PHP or Java.

Today, you can keep your website mostly static and implement a contact form in a Serverless environment, without any need for provisioning any virtual machine, web server or database.

While it may look odd, it is the nature of the Cloud: applications are going to be built with different services available from multiple vendors acting as one large distributed computing environment.

In this book we will use examples of services on AWS Cloud, invoked from the IBM Cloud. Indeed the book is about Apache OpenWhisk, not about the IBM Cloud.

The implementation that is shown in the example is not the best possible. It is just the simplest that we can do to show a result quickly and give a feeling of how we can do with OpenWhisk without getting lost in many details. Later in the book, we will rework the example to implement it in a more structured way.

Serverless development is primarily performed at the terminal, using a command line interface (CLI). We are going to use mostly the Unix based CLI and the command line interpreter Bash. In a sense, this is a Unix-centered book. Bash is available out-of-the-box in any Linux based environment and on OSX. It can also be installed on Windows.

On Windows, you can use either a command line environment including Bash like Git for Windows. Note that, despite the name, it is not just Git: it includes a complete Unix-like environment, based on Bash, ported to Windows. Also, on the more recent version of Windows, you may choose to install instead of the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) which even includes a complete Linux distribution like Ubuntu, with Bash of course. It is informally called Bash for windows also it is is a whole Linux OS running within Windows.

In the following examples, we are also going to use Bash widely for (numerous) command line examples. So you need to familiar working with Bash and the command line.

$ pwd/Users/msciab $ ls \

-l # total 16

-rw-r--r--@ 1 msciab staff 1079 24 Feb 09:53 form.js -rw-r--r--@ 1 msciab staff 71 23 Feb 17:18 submit.js

you should type now pwd at the command line

you should type at the terminal both the two lines

this is an example of the output you should expect

In the text, there will be both examples to be typed at the terminal and code snippets. You will identify code you have to type at the terminal (as in point 1 and 2) by the prefix $. In those examples only the code in the line after $ must be typed at the terminal, the rest is the expected output of the command.

Sometimes long command lines (as in point 2) are split into multiple lines, so you have to type all of them. You will notice when the input spawns for many lines, because lines end with a \.

One central theme of this books is the fact that Apache OpenWhisk is an Open Source product and you can deploy it in any cloud. We will see later in the book how to implement your environment, on-premises or in the cloud of your choice.

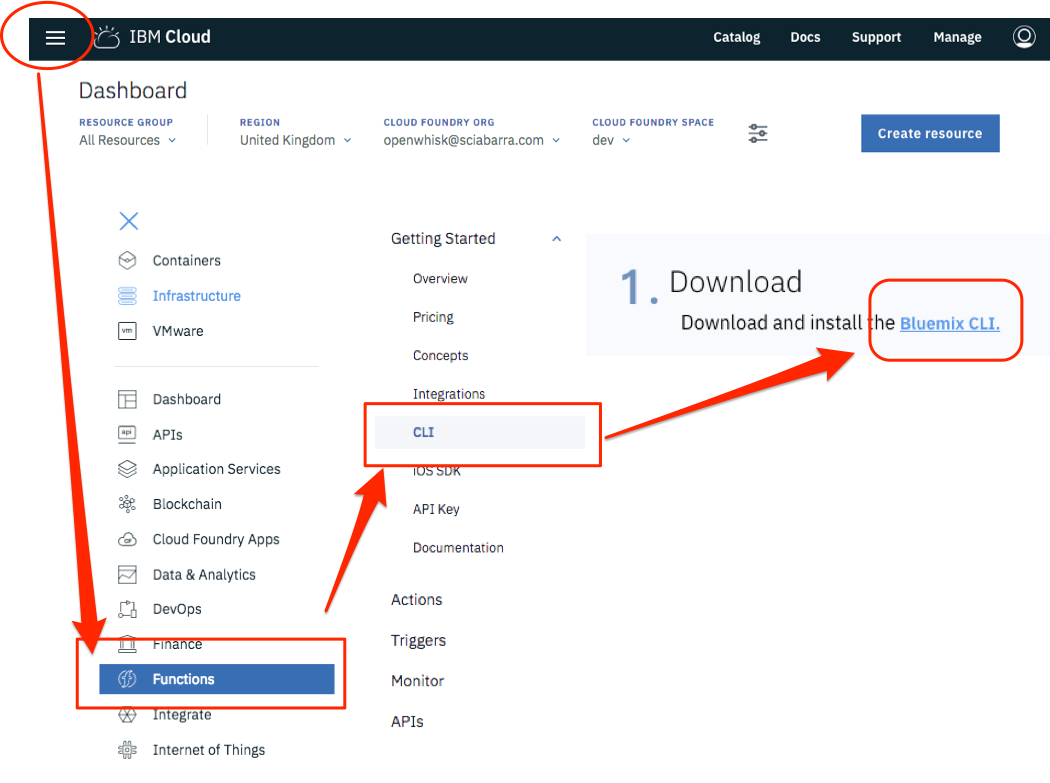

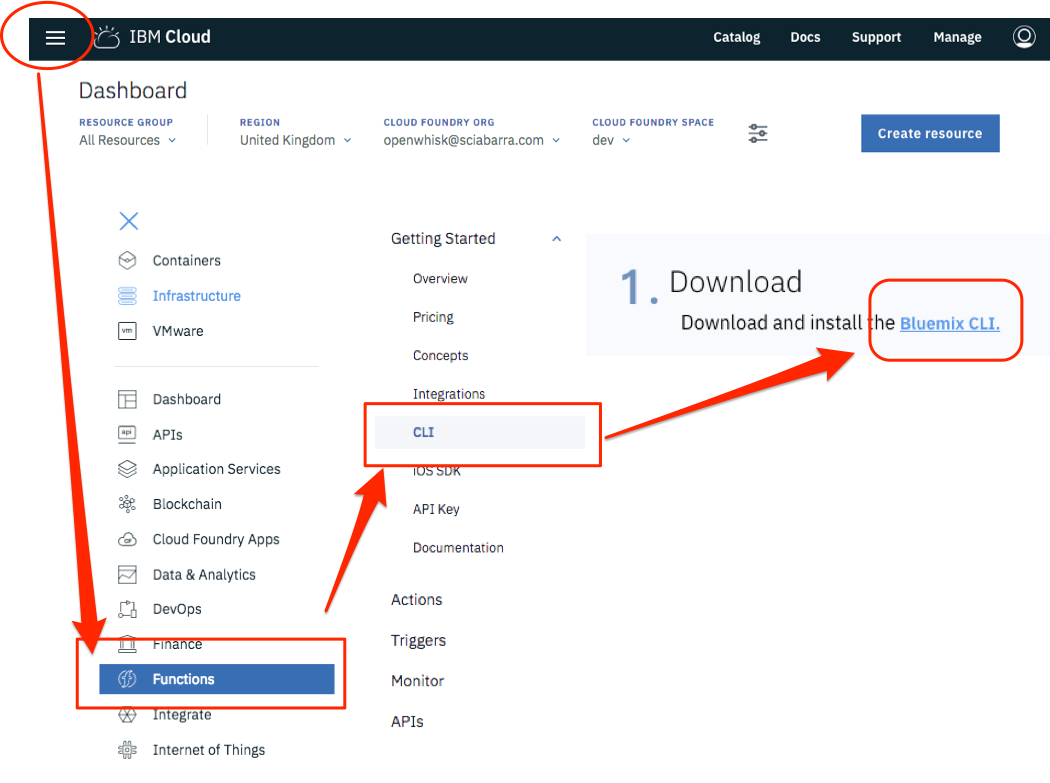

However, since Apache OpenWhisk is a project initiated by IBM and then donated to the Apache Foundation, it is available ready to use in the IBM Cloud. Since the OpenWhisk environment is offered for free for development purposes, the simplest way, to begin with, is to create an account there, and use it as our test environment.

Please be aware that since registration procedures and links may change over the time, when you will be reading the book there can be some differences in the actual procedure. So we are not going to delve into too many details describing the description of the registration process. It is pretty simple though, so you should be able to figure out by yourself.

At the time of this writing, you can start by going to the URL: http://console.bluemix.net. You can see then a button saying Create a free account.

You can then click there, provide your data and an email address and then activate your account, clicking on the link sent by email. Then you are done, and no credit card is required.

Please note the most important actions to do after the registrations are:

Login to the cloud

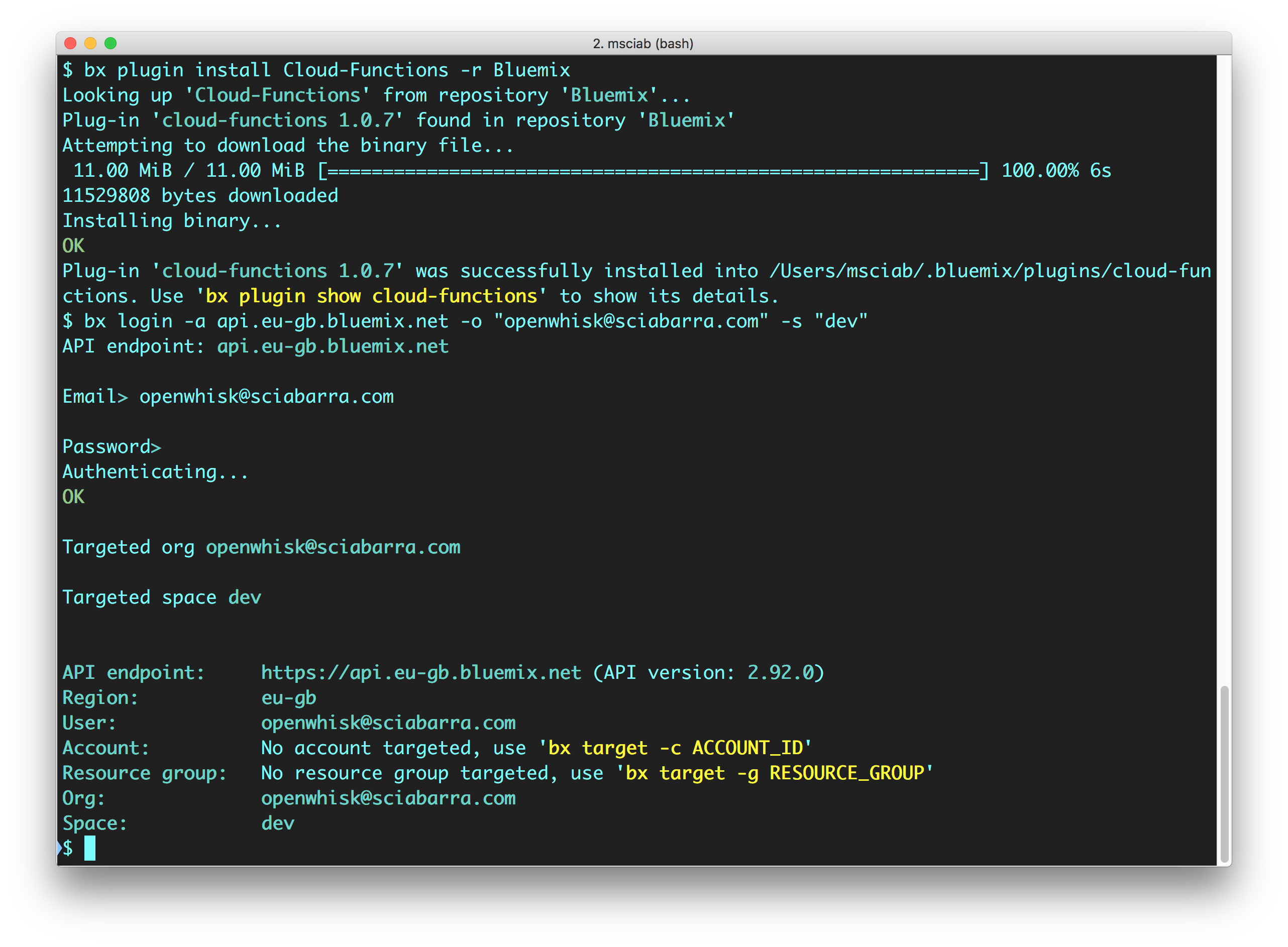

Download the bx CLI tool: Figure Figure 2-1

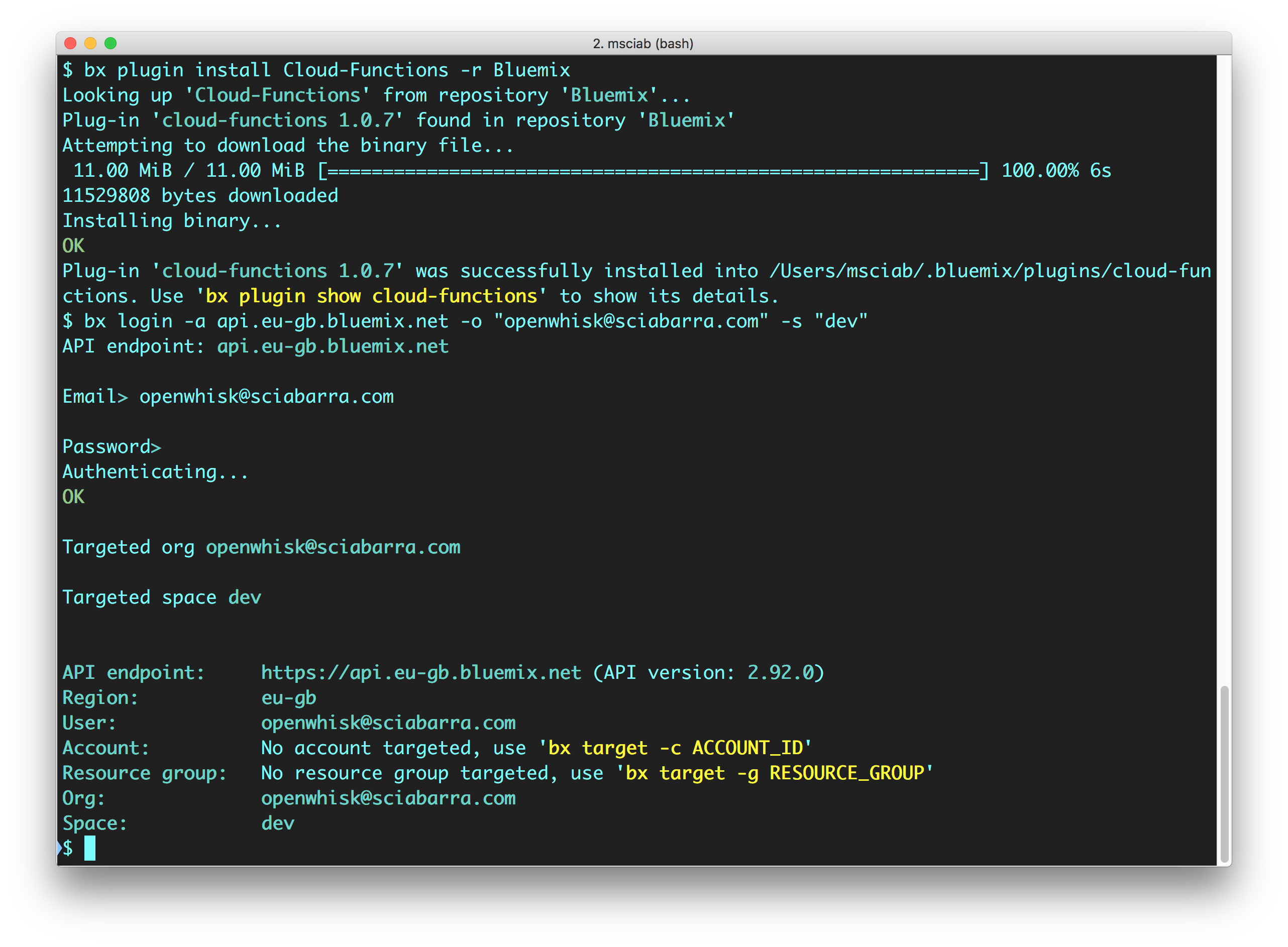

Install the CLI (bx) and the Cloud Functions plugin (wsk): Figure Figure 2-2

Login to the Cloud.

To be sure you are ready, run the following command at the terminal check the result. If they match with the listing, then everything is configured correctly!

$ bx wsk action invoke /whisk.system/utils/echo -p message hello --result

{

"message": "hello"

}

Now we are going to create and deploy a simple contact form.

We assume you already installed the bx command line tool with the wsk plugin. We also assume you are using a Unix-like command line environment: for example Linux, OSX or, if you are using Windows, you have already installed a version of Bash on Windows.

Open now a terminal and start Bash and let’s do the first step, creating a package to group our code:

$ wsk package create contact ok: created package contact

Now we are ready to start coding our application. In the Serverless world you can write some code, then deploy and execute it immediately. This modularity is the essence of the platform.

We are going to call the code we create actions. Action will generally be, at least in this chapter, one single file. There will be an exception when we bundle an action file with some libraries we need, and we deploy them together. In such a case, the action will be deployed as a zip file, composed of many files.

Let’s write our first action. The action is a simple HTML page returned by a javascript function.

function main() {

return {

body: `<html><head>

<link href="//maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.3.0/css/bootstrap.min.css"

rel="stylesheet" id="bootstrap-css">

</head><body>

<div id="container">

<div class="row">

<div class="col-md-8 col-md-offset-2">

<h4><strong>Get in Touch</strong></h4>

<form method="POST" action="submit">

<div class="form-group">

<input type="text" name="name"

class="form-control" placeholder="Name">

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<input type="email" name="email"

class="form-control" placeholder="E-mail">

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<input type="tel" name="phone"

class="form-control" placeholder="Phone">

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<textarea name="message" rows="3"

class="form-control" placeholder="Message"

></textarea>

</div>

<button class="btn btn-default" type="submit" name="button">

Send

</button>

</form>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</body></html>`

}

}

Note the general structure of the actions: the function is called main, it takes as an input a javascript obj and returns a javascript object. Those objects will be displayed at the terminal in JSON format.

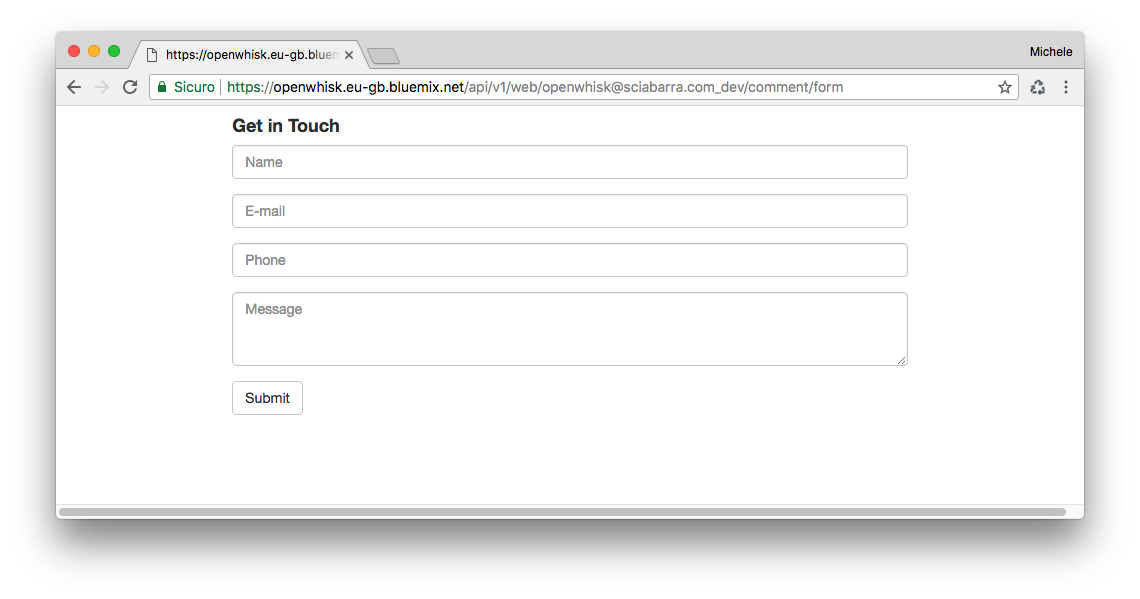

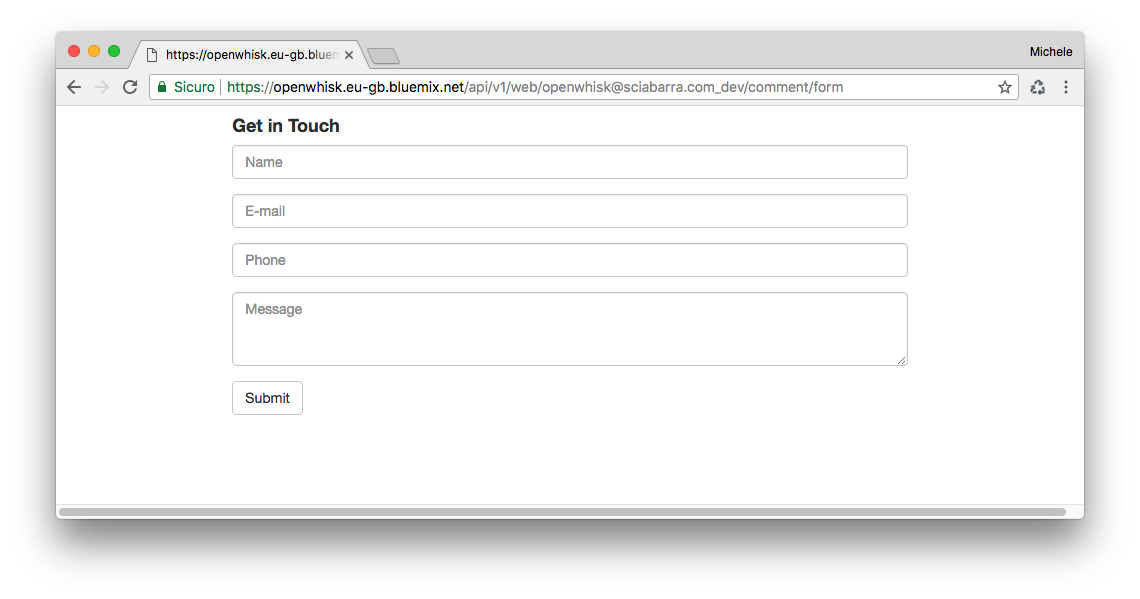

Once you wrote the code, you can deploy it, then retrieve the actual URL you can use to execute the action.

$ wsk action create contact/form form.js --web true ok: created action contact/form$ wsk action get contact/form --url ok: got action form https://openwhisk.eu-gb.bluemix.net/api/v1/web/openwhisk%40sciabarra.com_dev/contact/form

The actual URL returned will be different since it depends on your account and location.

We can now test if the form was deployed correctly just opening the URL with a web browser.

If you now click on the submit button, you will get an error, because it will try to submit the form to the action command/submit that does not (yet) exists.

{

"error": "The requested resource does not exist.",

"code": 3850005

}

After displaying, the next step of the processing is the validation of the data the user submits, before we store them in a database.

We will now create an action called submit.js we discuss step by step. First, let’s “wrap” our code in the main function:

function main(args) {

message = []

errors = []

// TODO: <Form Validation>  // TODO: <Returning the Result>

// TODO: <Returning the Result>  }

}

Note that the action has a similar structure to the preceding, with a main method, now with an explicit parameter args. Let see what happens when you submit the form.

We have a form with some fields: “name”, “email”, “phone”, “message”. On submit, the form data will be encoded, sent to OpenWhisk, that will decode them (we will provide all the details of the processing later in this chapter).

You create a javascript object to process a request using an action. Each key corresponds to a field of the form. This object is passed as the argument of the main function. So our form fields are available to the main function as args.name, arg.email, etc. We can now validate them.

Below we show the code to process the form, adding valid fields to message or any error to errors.

First, let’s check only if the name is provided.

You should add the snippets in this paragraph after <Form Validation>

// validate the name

if(args.name) {

message.push("name: "+args.name)

} else {

errors.push("No name provided")

}

Second, let’s validate the email address, checking if it “looks like” an email. We use here a regular expression:

// validate email

var re = /\S+@\S+\.\S+/;

if(args.email && re.test(args.email)) {

message.push("email: "+args.email)

} else {

errors.push("Email missing or incorrect.")

}

Third, let’s validate the phone number, checking it has “enough” digits (at least 10):

/// validate the phone

if(args.phone && args.phone.match(/\d/g).length >= 10) {

message.push("phone: "+args.phone)

} else {

errors.push("Phone number missing or incorrect.")

}

Finally, let’s add the message text if any:

/// add the message text, optional

if(args.message) {

message.push("message:

"+args.message)

}

Once we have all the fields validated, we can return the result. There is now a bit of logic: we choose if returning an error message or an acceptance message.

Insert the snippets in this paragraph after <Returning the Result>

// complete the processing

var data = "<pre>"+message.join("\n")+"</pre>"

var errs = "<ul><li>"+errors.join("</li><li>")+"</li></ul>"

if(errors.length) {

return {

body: "<h1>Errors!</h1>"+

data + errs +

'<br><a href="javascript:window.history.back()">Back</a>'

}

} else {

// storing in the database

// TODO: <Store the message in the database>  return {

body: "<h1>Thank you!</h1>"+ data

}

}

return {

body: "<h1>Thank you!</h1>"+ data

}

}

The action is not complete (we have still to see how to store the data) but we can test this partial code with this command:

$ wsk action create contact/submit submit.js --web true ok: created action contact/submit

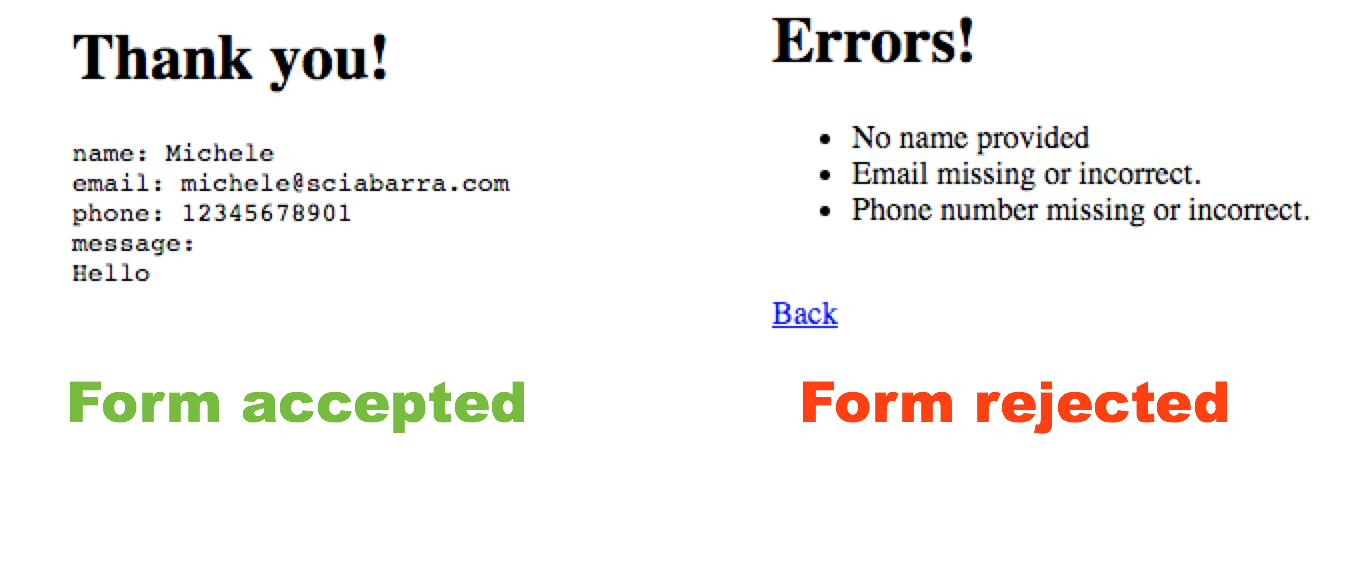

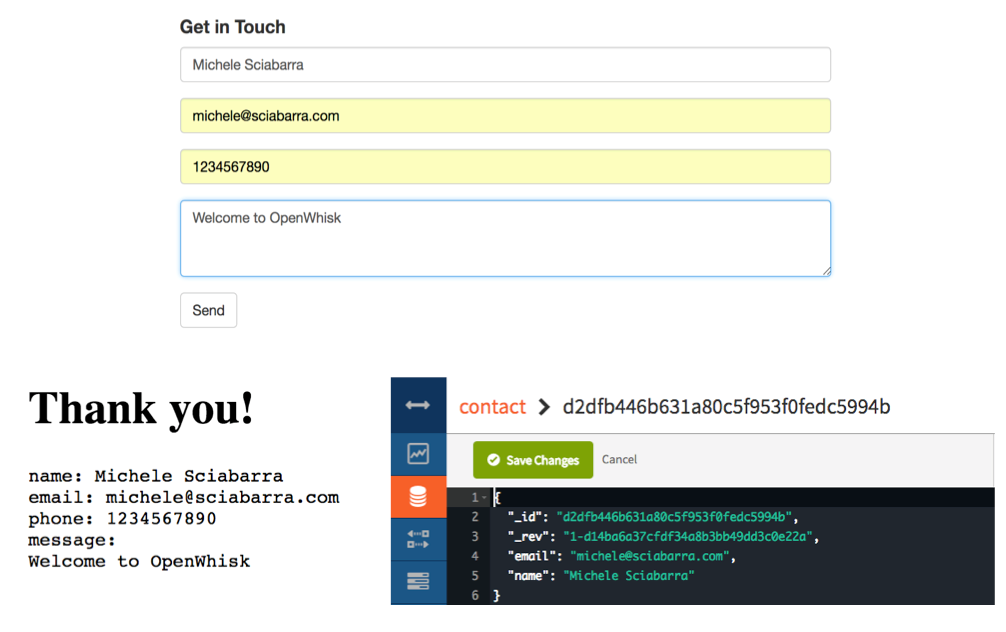

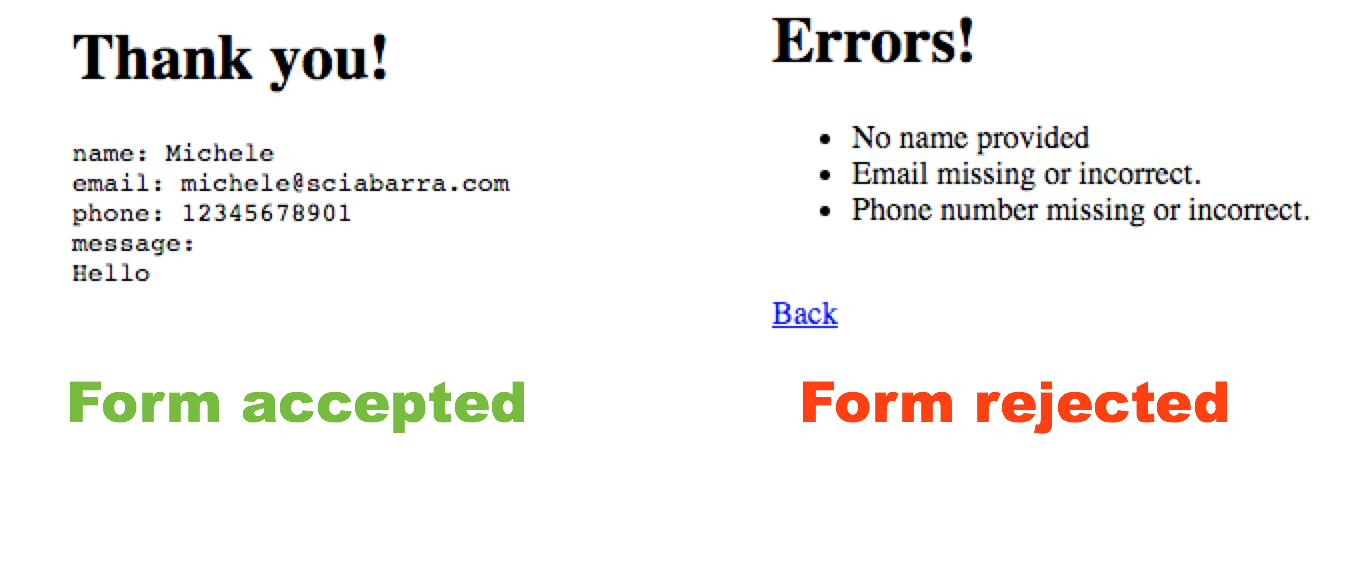

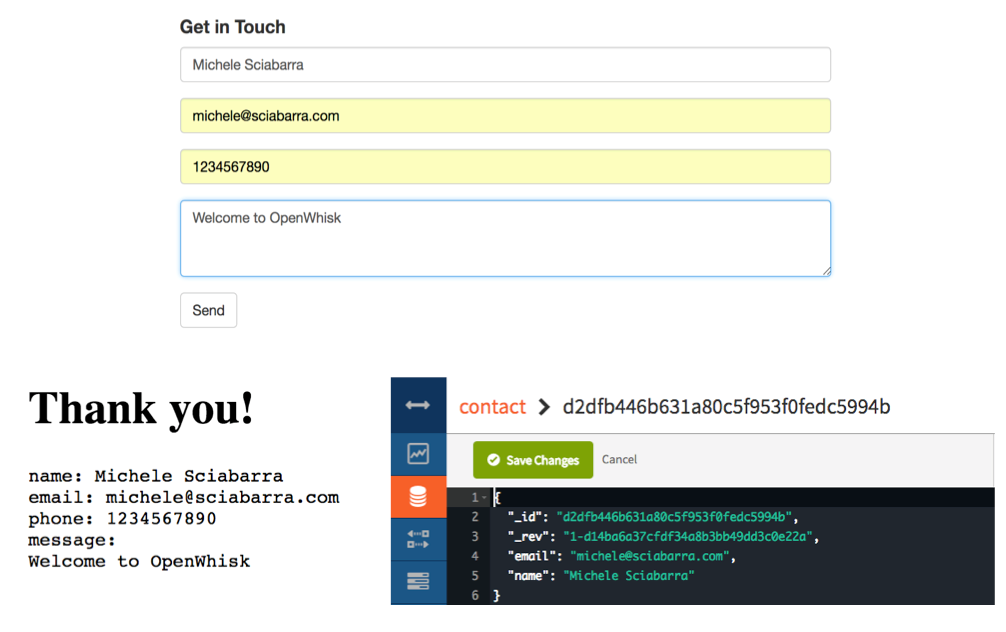

If you now submit the form empty, you will see the message in Figure Figure 2-4 under “Form Rejected”. If we instead provide all the parameters correctly, we will be gratified with the acknowledgment under “Form Accepted”.

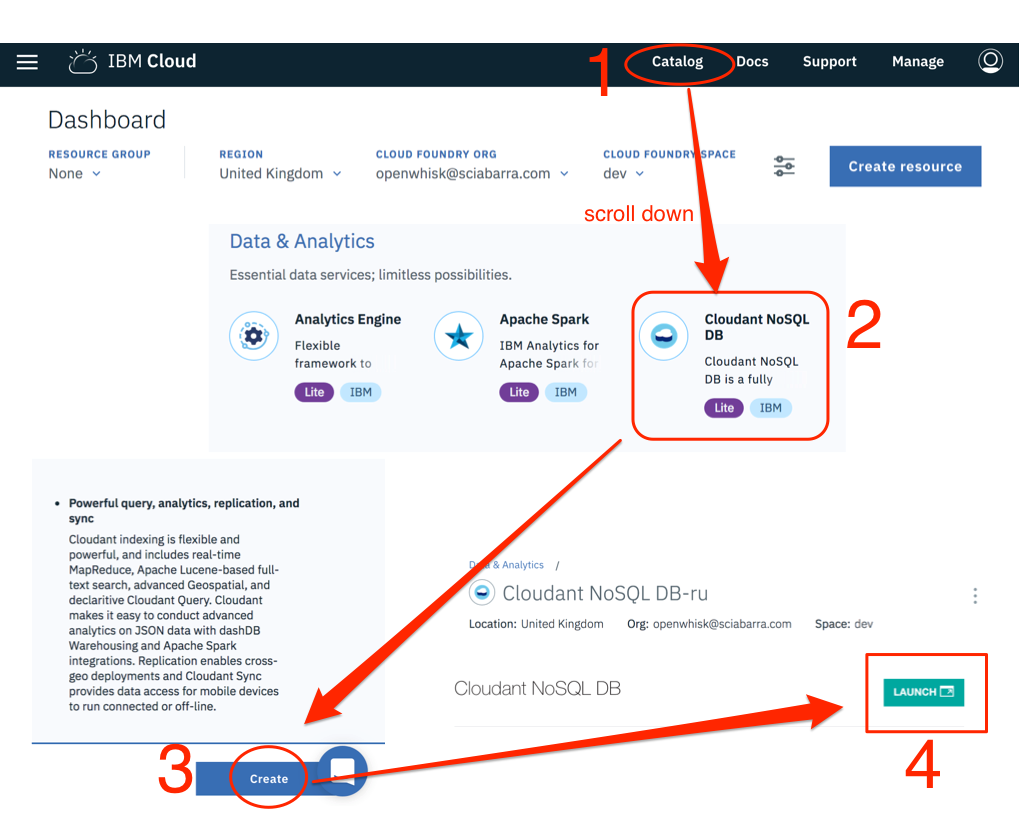

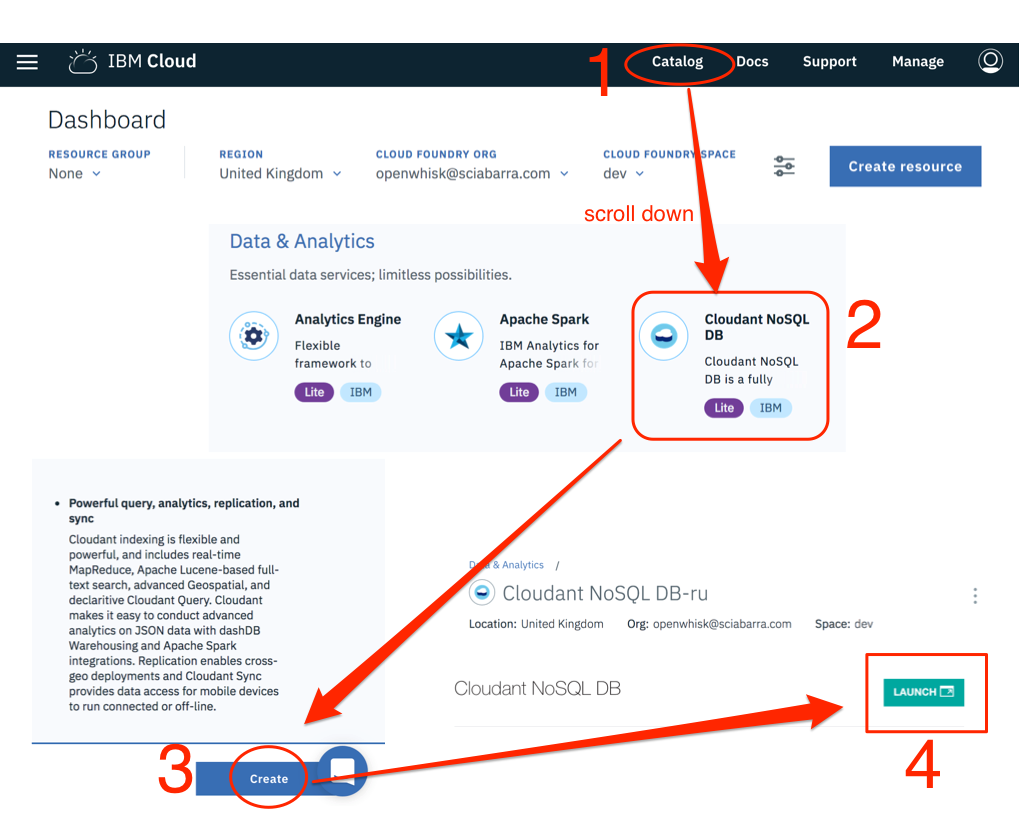

Now we can focus on database creation, to store our form data. Since we have already an IBM Cloud account, the simplest way is to provision a Cloudant database. For small amounts of data, it is free to use.

Steps to create the database, as shown in Figure Figure 2-5 are pretty simple.

Select Catalog

Search for Cloudant NoSQL database the click

Select the button Create to create a Lite instance

Click on Launch to access the administrative interface

Click on “Create Database” (not shown in the Figure)

Finally, specify contact as the database name

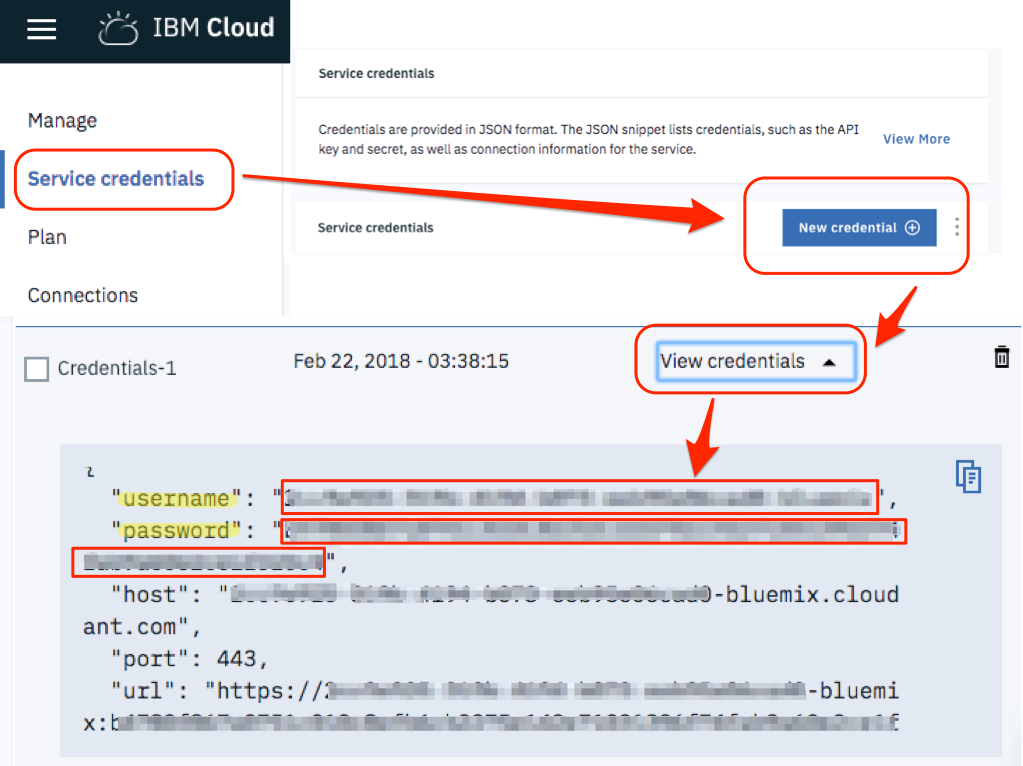

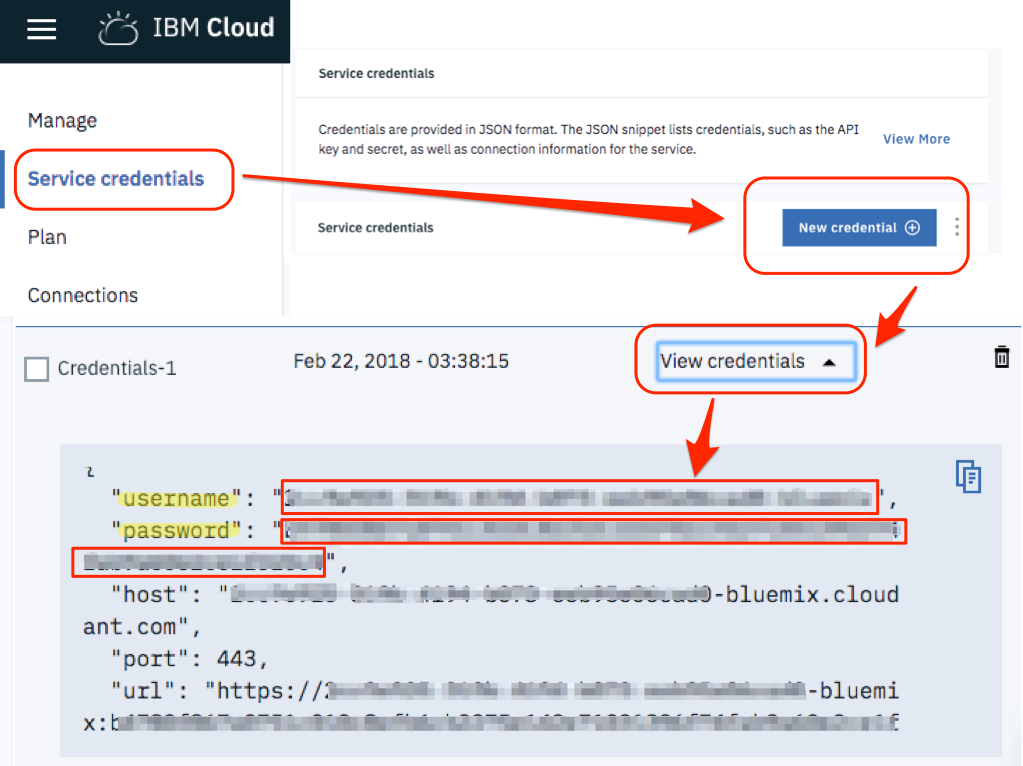

Now we need to get the credentials to access the database.

You have to go into the menu of the Cloudant service, click on “Service Credentials”, then click on “New Credentials” and finally select “View Credentials”. It will show a JSON file.

You need to extract the values in the fields username and password. You can now use those values at the command line to “bind” the database: This is what you have to type on the terminal.

$ export USER=XXXX$ export PASS=YYYY

$ wsk package bind \ /whisk.system/cloudant contactdb \ -p username $USER \ -p password $PASS \ -p host $USER.cloudant.com \ -p dbname contactdb ok: created binding contactdb $ wsk action invoke contactdb/create-database -r

{ "ok": true } $ wsk package list

packages /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/contactdb private /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/contact private

copy here the username

copy here the password

create the actual database

now check you will have two packages

Note that after binding you have a new package with some parameters, allowing to read and write in your database. OpenWhisk provides a set of generic packages. We used the command bind to make it specific to write in our database giving username and password.

This package provides many actions we can see listing them (the following output is simplified since the actions are a lot):

$ wsk action list contactdb /whisk.system/cloudant/write private nodejs:6 /whisk.system/cloudant/read private nodejs:6

Creating the package binding gave you access to multiple databases. But since we need just one, we specified the default database we want to use (using the parameter dbname for the package) and then we explicitly invoked the create-database to be sure that database is created.

So far we have seen how we can create actions and how to invoke them. Actually, in the first two examples, we have seen one specific kind of actions: web action (you may have noted the --web true flag in the commands). Those are the actions which can be invoked directly, navigating to web URLs or submitting web forms.

However, not all the actions are there to be invoked straight from the web. Many of them execute internal processing and are activated only through some specific APIs.

The actions letting to read and write in the database, those who we just exported from the Cloudant package, are not web actions. They can be invoked however using the command line interface.

In particular, we have to use the wsk action invoke command, passing parameters with the --param options and data in JSON format as a command line argument.

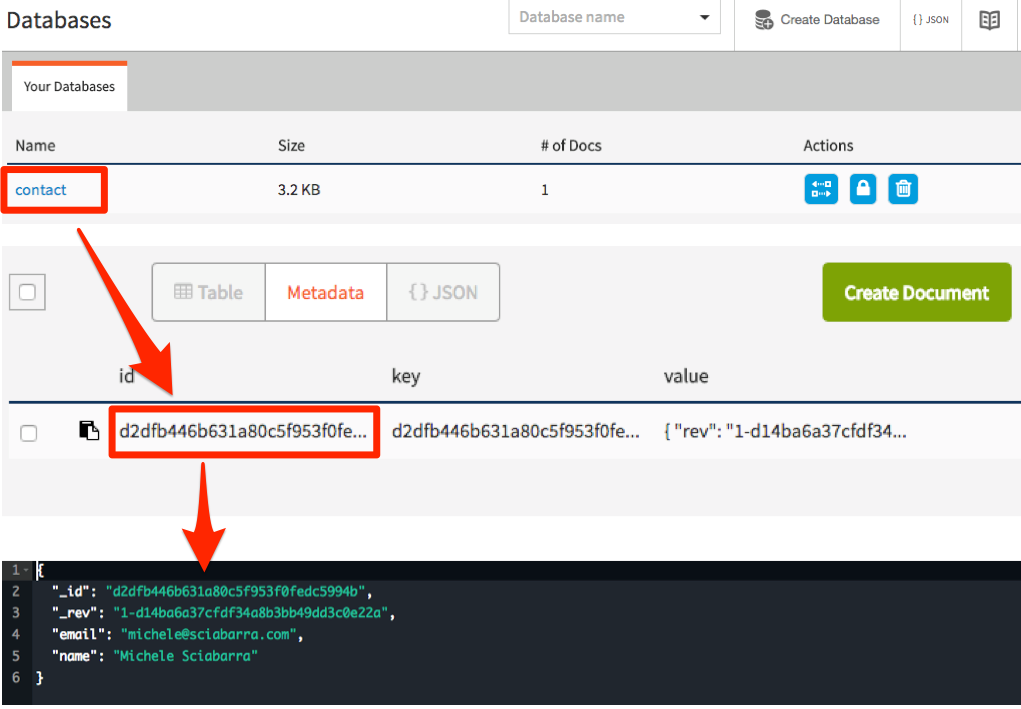

Let verify how it works, writing in the database, by invoking the action directly write, as follows.

$ wsk action invoke contactdb/write \

--blocking --result --param dbname contactdb \

--param doc '{"name":"Michele Sciabarra", "email": "michele@sciabarra.com"}'

{

"id": "fad432c6ea1145e71e99053c0d811475",

"ok": true,

"rev": "1-d14ba6a37cfdf34a8b3bb49dd3c0e22a"

}

We used the --blocking option to wait for the result; otherwise, the action will start asynchronously, and we will have to come back later to get the result. Furthermore, we are using the --result option to print the final result. Those options will be discussed in details in the next chapter.

The database replied with a confirmation and some extra information. Most notably, the result includes the id of a new record, that we can use later for retrieving the value.

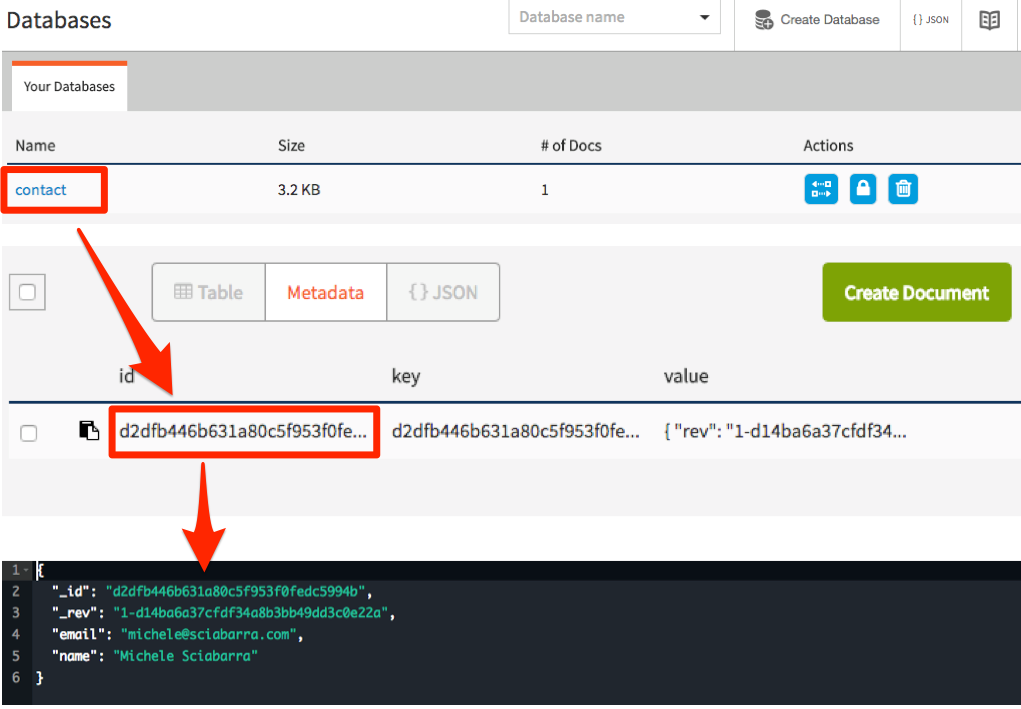

We can now check the database user interface to see the data we just stored in it. You can select the database, then the id and you can see the data we just inserted in the database in JSON format.

As you can see, to write data in the database you need just a JSON object. So far we wrote data using the command line. Let’s look at how we can do it in code.

OpenWhisk includes an API to interact with the rest of the system. Among the possibilities, there is the ability to invoke actions.

We provisioned the database as a package binding. Thus we have now an action available to write in the database. To use it we need to invoke the action from another action. Let see how.

First and before all, we need a:

var openwhisk = require('openwhisk')

to access to the openwhisk API. This code is the entry point to interact with OpenWhisk from within an action.

Now, we can define the function save using the OpenWhisk API to invoke the action to write in the database. The following code should be placed at the beginning of the submit.js:

var openwhisk = require('openwhisk')

function save(doc) {

var ow = openwhisk()

return ow.actions.invoke({

"name": "/_/contactdb/write",

"params": {

"dbname": "contactdb",

"doc": doc

}

})

}

Currently, you need to add the var ow = openwhisk() inside the body of the main function. It is a documented issue: environment variables used to link the library to the rest of the system, are available only within the main method. So you cannot initialize the variable outside (as you may be tempted to do).

Once the save function is available, you can use it to save data just by creating an appropriate JSON object and pass it as a parameter. Place the following code after <Store the message in the database>:

save({

"name": args.name,

"email": args.email,

"phone": args.phone,

"message": args.message

})

We “extracted” the arguments instead of just saving the whole args object because it includes other information we do not want to keep.

The code is now complete. We can deploy it, as a web action too, to be executed when the user posts the form:

$ wsk action update contact/submit submit.js --web true ok: updated action contact/submit

We can now manually test the action from the command line, to check if it writes in the database:

$ wsk action invoke contact/submit -p name Michele -p email \

michele@sciabarra.com -p phone 1234567890 -r

{

"body": "<h1>Thank you!</h1><pre>name: Michele

email: michele@sciabarra.com

phone: 1234567890</pre>"

}

Now we can go on and try our form, verifying data are written in the database, as in figure Figure 2-8.

We do not generally recommend manual testing for your Serverless code. Indeed there will be an entire chapter devoted to how to write automated tests. We are showing manual test here only as a tool to get a feeling of the system, not as a recommendation of how you should write your code.

Now we add a feature that demonstrates interaction with other systems. In a sense, it is going to be a bit advanced. We are going to send an email when someone uses our contact form. Not just sending emails when a visitor completes the submission, but also we want to be notified even of partial and wrong submissions of the form.

Sending email is usually done with the SMTP protocol, but since email is generally abused to send spam in all the cloud services, cloud providers usually block SMTP ports; hence it is not usable. In the IBM Cloud which we are using, they are indeed blocked (at least in our tests). This fact is the reason we used a third party service for sending email, a service that provides an HTTP API and a javascript library to use it.

We are going to use the service Mailgun for this purpose. It provides free accounts, allowing for a limited number of emails sent only to selected and validated addresses. It is perfect for our goal.

To use Mailgun you need to go to the website www.mailgun.com and register for a free account. Once you have set up an account you will get a “sandboxed” account (note the site will ask for a phone number for verification purposes).

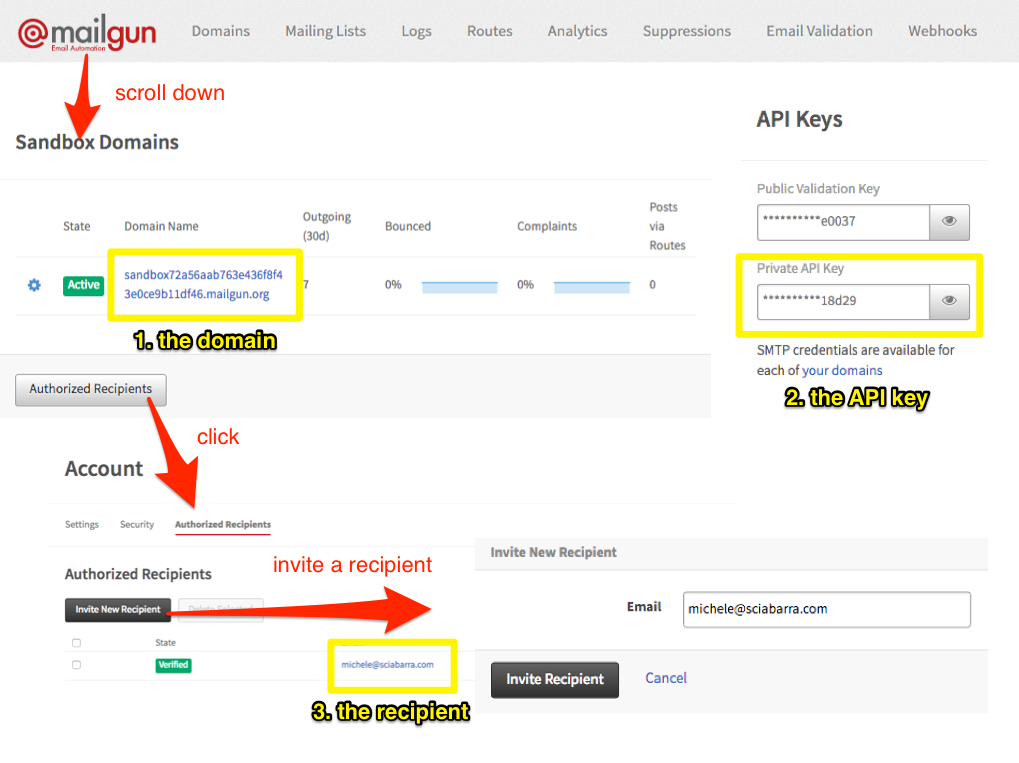

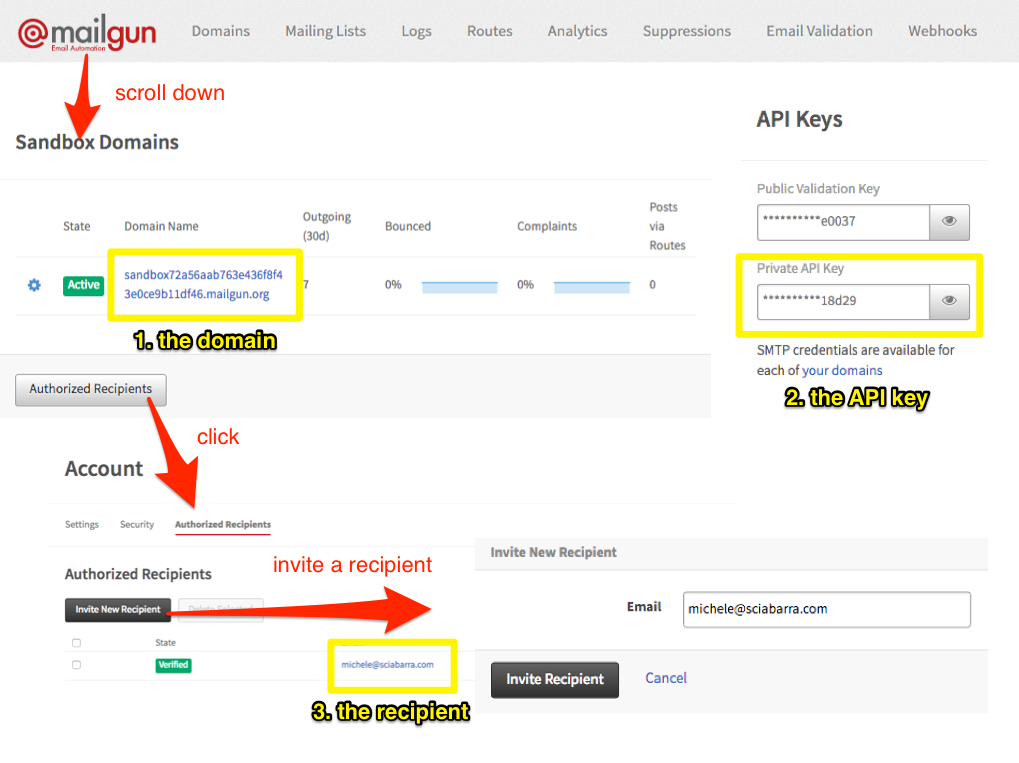

Once registered, to retrieve credentials for sending an email (Figure Figure 2-9) you need to:

Login in Mailgun

Scroll down until you find the Sandbox Domain

Click on “Authorized Recipient”

Invite the recipient

Click on the link in the email received

Once done, you need the following information, as shown in the figure, for writing your script:

the sandboxed domain

the private API key

the authorized recipient address

Now, we can build an action for sending an email. Actually, the purpose of this example is to show how you can create more complex action involving third-party services and libraries.

Hence now preparing this action is a bit more complicated than the actions we have seen before, because we need to use and install an external library then and deploy it together with the action code.

Let start by creating a folder and importing the library mailgun-js with the npm tool. We assume you have installed it, refer to Appendix II for details about the purpose and usage of this tool.

$ mkdir sendmail $ cd sendmail $ npm init -y $ npm install --save mailgun-js

Now we can write a simple action that can send an email and place it in sendmail/index.js. Check the listing with the notes about the information you have to replace with those who collected before when registering to Mailgun.

var mailgun = require("mailgun.js")

var mg = mailgun.client({username: 'api',

key: 'key-<YOUR-PRIVATE-API-KEY>'})  function main(args) {

return mg.messages.create(

'<YOUR-SANDBOX-DOMAIN>.mailgun.org', {

function main(args) {

return mg.messages.create(

'<YOUR-SANDBOX-DOMAIN>.mailgun.org', {  from: "<YOUR-RECIPIENT-EMAIL>",

from: "<YOUR-RECIPIENT-EMAIL>",  to: ["<YOUR-RECIPIENT-EMAIL>"],

to: ["<YOUR-RECIPIENT-EMAIL>"],  subject: "[Contact Form]",

html: args.body

}).then(function(msg) {

console.log(msg);

return args;

}).catch(function(err) {

console.log(err);

return args;

})

}

subject: "[Contact Form]",

html: args.body

}).then(function(msg) {

console.log(msg);

return args;

}).catch(function(err) {

console.log(err);

return args;

})

}

replace key-<YOUR-PRIVATE-API-KEY> with the Private API Key

replace <YOUR-SANDBOX-DOMAIN>.mailgun.org with the Sandbox Domain

replace <YOUR-RECIPIENT-EMAIL> with the one that is used both as the sender and the recipient

same as 3

For simplicity, we placed the keys within the script. Also, this is not a recommended practice. We will see later how we can define parameters for a package and use them for each action, so you do not have to store keys in the code.

We can deploy now the action. Since this time the action is not a single file, but it includes libraries, we have to package everything in a zip file, to deploy them too.

$ zip ../sendmail.zip -r * $ wsk action update contact/sendmail ../mailgun.zip --kind nodejs:6 ok: updated action contact/sendmail

We are using update here even if the action was not present before. Indeed since update will create the action if it does not exists, we prefer to use just update always to avoid the error create gives if the action was already there. Also, since we place the action in a zip file, we need to specify its type because the command line cannot deduct it from the filename.

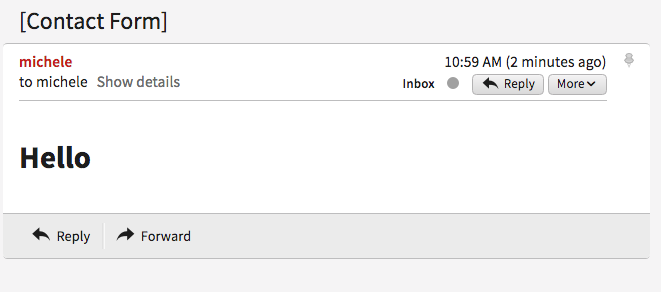

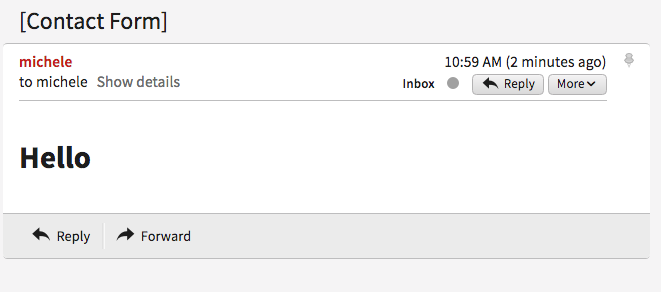

We can now test the action invoking it directly:

$ wsk action invoke contact/sendmail -p body "<h1>Hello</h1>" -r

{

"body": "<h1>Hello</h1>"

}

The action acts as a filter, accepting the input and copying it in the output. We will leverage this behavior to chain the action to the submit.

When invoked, it will return an output, but also it will send an email as a side effect.

So far we have developed an action that can send an email as a stand-alone action.

However, we designed the action in such a way that it can take the output of the submit action and return it as is. So we can create a pipeline of actions, similar to the Unix shell processing, where the output of a command is used as an input for another command.

We are going to take the output of the sendmail action, use it as the input for the submit action and then return it as the final result of the email submission.

Please note as a side effect; it will send emails for every submission, also for incorrect inputs, so we can know someone is trying to use the form without providing full information.

However, we will store in the database only the fully validated data. Let’s create such a pipeline that is called sequence in OpenWhisk, and then test it.

$ wsk action create contact/submit-sendmail \

--sequence contact/submit,contact/sendmail \

--web true

ok: updated action contact/submit-sendmail

$ wsk action invoke contact/submit-sendmail -p name Michele -r

{

"body": "<h1>Errors!</h1><pre>name: Michele</pre><ul><li>Email missing or incorrect.</li><li>Phone number missing or incorrect.</li></ul><br><a href=\"javascript:window.history.back()\">Back</a>"

}

As a result, we should be receiving an email for each attempt of submitting a form, including partial data from the contact form.

Now we are ready. We can use the complete form including storing in the database and sending the email. But now the form should activate our sequence, not just the submission action. The simplest way is to edit the form.js, replacing the action we are invoking in the form. We should do the following change in form.js:

-<form method="POST" action="submit"> +<form method="POST" action="submit-sendmail">

The change to do in your code is in patch format. We are not going to cover it in detail, but mostly the prefix - means: remove this line, while the prefix + means: add this line. We will use this notation again in the book.

If we now update the action and try it, we will receive an email for each form submission, but the form will be stored in the database only when the data is complete.

Started from scratch with OpenWhisk.

Learned how to get an account in a cloud supporting it (the IBM cloud) and download the command line interface.

Created a simple HTML form in OpenWhisk

Implemented simple form validation logic.

Stored results in a NO-SQL database (Cloudant)

Connected to a third party service (Mailgun) to send an email.

OpenWhisk applications are composed by some “entities” that you can manipulate either using a command line interface or programmatically in javascript code.

The command line interface is the wsk command line tools, that can be used directly on the command line or automated through scripts. You can also use Javascript using an API crafted explicitly for OpenWhisk. They are both external interfaces to the REST API that OpenWhisk exposes. Since they are both two different aspects of the same thing (talking to OpenWhisk) they are both covered in this chapter.

Before we go deeper through the details of the many examples covering design patterns in the next chapters, we need to be familiar with the OpenWhisk API.

The API is used frequently to let multiple actions to collaborate. This chapter is hence a key chapter since the API is critical to writing applications that leverage the specific OpenWhisk features.

We already quickly saw the fundamental entities of OpenWhisk in the practical example in Chapter 2, but here we recap them here for convenience and clarity:

Packages: they are a way to grouping actions together, also they provide a base URL that can be used by web applications.

Actions: the building blocks of an OpenWhisk application, can be written in any programming language; they receive input and provide an output, both in JSON format.

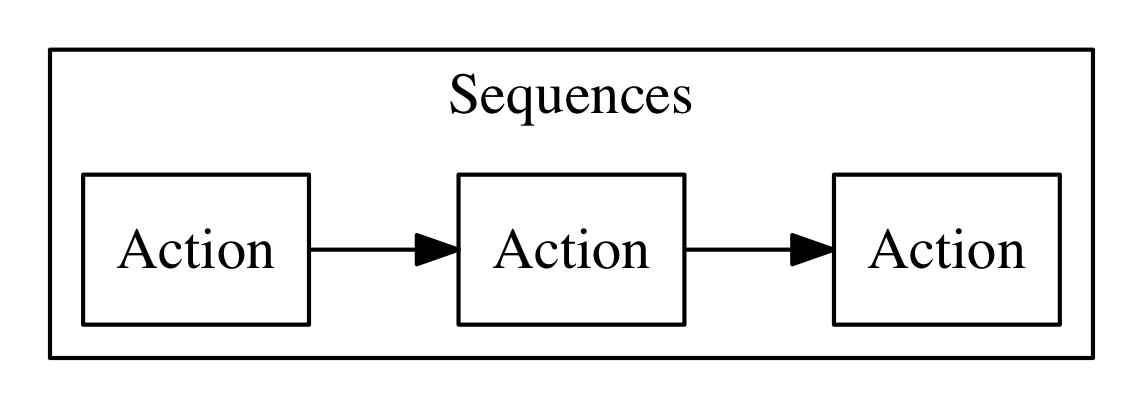

Sequences: actions can be interconnected, where the output of action becomes the input of another, creating, in fact, a sequence.

Triggers: they are entry points with a name and can be used to activate multiple actions.

Rules: a rule associate a trigger with an action, so when you fire a trigger, then all the associated actions are invoked.

Feeds: they are specially crafted actions, implementing a well-defined pattern; its purpose is connecting events provided by a package with triggers defined by a consumer.

Now let’s give an overview of the command line interface of OpenWhisk, namely the command wsk.The wsk command is composed of many commands, each one with many subcommands. The general format is:

wsk <COMMAND> <SUB-COMMAND> <PARAMETERS> <FLAGS>

Note that <PARAMETERS> and <FLAGS> are different for each <SUBCOMMAND>, and for each <COMMAND> there are many subcommands.

The CLI itself is self-documenting and provides help when you do not feed enough parameters to it. Just typing wsk you get the list of the main commands. If you type the wsk command then the subcommand you get the help for that subcommand.

For example, let’s see wsk output (showing the command) and the more frequently used command, action, also showing the more common subcommands, shared with many others:

$ wsk Available Commands: action work with actions activation work with activations package work with packages rule work with rules trigger work with triggers property work with whisk properties namespace work with namespaces list list entities in the current namespace $ wsk action create create a new actionupdate update an existing action

invoke invoke action get get action

delete delete action

list list all action

create available for actions, packages, rules and triggers

update available for actions, packages, rules and triggers

get available for actions, packages, rules and triggers, and also for activations, namespaces and properties

delete available for actions, package, rule and triggers

list available for actions, package, rule and triggers, and also for namespace and for everything.

Remembering that commands are the entities and the subcommands are C.R.U.D. (Create, get/list for Retrieve, Update, Delete) gives you a good mnemonic of how the whole wsk command works. Of course, there are individual cases, but we cover those in the discussion along the chapter.

Subcommands also have flags, some specific for the subcommand. In the rest of the paragraph, we discuss all the subcommands. We provide the details of interesting flags as we meet them.

The wsk command has many “properties” you can configure to access to an OpenWhisk environment. When you use the IBM Cloud, those properties are actually set for you by the ibmcloud main command. If you have a different OpenWhisk deployment, you may need to change the properties manually to access it.

You can see the currently configured properties with:

$ wsk property get Client key whisk auth xxxxx:YYYYYwhisk API host openwhisk.eu-gb.bluemix.net

whisk API version v1 whisk namespace _

whisk CLI version 2017-11-15T19:55:32+00:00 whisk API build 2018-02-28T23:44:25Z whisk API build number whisk-build-7922

the API authentication key (replaced in the example with xxxxx:YYYYY) - your own will be different

the OpenWhisk host you connect to control OpenWhisk with the CLI - depends on your location

your current namespace (the value _ is a shorthand for you default namespace)

If you install a local OpenWhisk environment, you need to set those properties using wsk property set manually. In particular, you need to set the whisk auth and the whisk host properties with values provided by your local installation.

Let’s see how we name things. As you may already know, in OpenWhisk we have the following entities with a name:

packages

actions

sequences

triggers

rules

feeds

There are precise naming conventions for them. Furthermore, those conventions are reflected in the structure of the URL used to invoke the various elements of OpenWhisk.

First and before all, each user is placed in a namespace, and everything a user creates, belong to it. It acts as a workspace and also provides a base URL for what a user creates. Credentials for a user allows access to all the resources in its namespace.

For example, when I registered in the IBM Cloud, my namespace was /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/. It is my username followed by _dev (for development).

You can create a namespace in an OpenWhisk installation if you are authorized, otherwise, a namespace is created for you by the system administrator.

Under a namespace you can create triggers, rules, actions and packages, so they will have names like:

/openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/a-triggger

/openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/a-rule

/openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/a-package

/openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/an-action

When you create a package, you can put in its actions and feeds. So for example below the package a-package you can have:

/openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/a-package/another-action

/openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/a-package/a-feed

To recap:

The general format for entities is: /namespace/package/entity, but it can be reduced to /namespacke/entity

Under a namespace you can create triggers, rules, package, and actions but not feeds.

Under a package you can create actions and feeds, but not triggers, rules, and other packages.

Most of the time you do not need to specify the namespace. If you specify an action as a relative action (not starting with /) it will be placed in your current namespace. Note that the special namespace name of _ means “your current namespace” and the full namespace name automatically replace it.

In OpenWhisk, according to the naming conventions, all the entities are grouped in a namespace. We can put actions under a namespace.

Below a namespace, you can create packages to bundle actions together. A package is useful for two main purposes:

group related actions together, to reuse them and share with others

provide base a URL to those related actions, useful for actions that refer each other, like in web applications.

However, it is usually convenient to further groups actions. Under a namespace, we can create packages, and put action under them. Packages are hence useful for grouping actions (and feeds, that are just actions too), treating them as a single unit. Furthermore, a package can also include parameters.

Let’s do an example. We can just create a package sample, also providing a parameter, as follows.

$ wsk package create sample -p email michele@sciabarra.com ok: created package basics

Parameters of a package are available to all the actions in a package.

Now you can list packages, get`information from packages, `update it (for example with different parameters) and finally delete it.

$ wsk package list packages /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/sample private /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/basics private /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/contact private /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/contactdb private $ wsk package update sample -p email openwhisk@sciabarra.com ok: updated package sample $ wsk package get sample -spackage /openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/sample: Returns a result based on parameter email (parameters: *email) $ wsk package delete sample ok: deleted package basics

Now let’s see another essential function of a package: binding.

OpenWhisk allows to import (or bind) to your namespace, packages from a third party, to customize them for your purposes.

Keep in mind that credentials of a user allow access to all the resources under a namespace. As a result, to bind a package in our namespace has the effect of making it accessible to the other actions in the namespace.

For example, let’s review first the packages available in the IBM cloud. Of course, this cloud includes their solution for everyday needs like databases and message queues. The database available in the IBM Cloud is a scalable version of the popular no-SQL database CouchDB, i.e., Cloudant.

A package for Cloudant is available, as we can see below, and all we need to do to use it is to bind it. In the example below, we use the configuration file cloudant.json. How to retrieve the configuration file is described in Chapter 2.

$ wsk package list /whisk.system packages/whisk.system/cloudant shared /whisk.system/websocket shared /whisk.system/alarms shared /whisk.system/messaging shared $ wsk package get /whisk.system/cloudant -s | head -2

package /whisk.system/cloudant: Cloudant database service (parameters: *apihost, *bluemixServiceName, *dbname, *host, overwrite, *password, *username)

$ wsk package bind /whisk.system/cloudant patterndb \

-P cloudant.json -p dbname pattern

ok: created binding contactdb

We are listing the packages available in the IBM Cloud. I edited and shortened the output for clarity.

We are inspecting the Cloudant package. We are limiting to see only the first two lines, those describing the package.

Note here the required parameters to use the database

we created here the binding to make the database accessible

We are using the file cloudant.json for the specifying host, username and password, and providing the dbname on the command line.

Two common flags, available also for actions, feed and triggers are -p and -P. With -p <name> <value> you can specify a parameter named <name> with value <value>. With the -P you can put some parameters in a JSON file that is assumed to be a map.

The subcommand wsk actions let you manipulate actions.

The more common subcommands are the CRUD actions to list, create, update and delete actions. Let’s demonstrate them with some examples.

We create and use a simple now action for our examples:

function main(args) {

return { body: Date() }

}

Now, if we want to deploy this simple action in the package basics we do:

$ wsk package update basicsok: updated package basics $ wsk action create basics/now basics/now.js

ok: created action basics/now

You could omit the basics and place the action in the namespace and not in a package. We do not advise to do so, however, because gathering your actions in packages is always a good idea to improve modularity and reuse.

Now that the action has been deployed, we can invoke it. The simplest way is to call it as:

$ wsk action invoke basics/now ok: invoked /_/basics/now with id fec047bc81ff40bc8047bc81ff10bc85

Wait a minute… where is the result? Actually, actions in OpenWhisk are by default asynchronous, so what you get usually is just an id (called activation id) to retrieve the result after the action completed. We discuss activations in detail in the next paragraph.

If we instead we want to see the result immediately, we can provide the flag -r or --result. It blocks until we get an answer. So:

$ wsk action invoke basics/now -r

{

"body": "Thu Mar 15 2018 14:24:39 GMT+0000 (UTC)"

}

Great. However, what is if want to access that action from the web? We can retrieve an URL with get and --url.

If we leave out the --url we get a complete description of the action in JSON format:

$ wsk action get basics/now --url

https://openwhisk.eu-gb.bluemix.net/api/v1/namespaces/openwhisk%40sciabarra.com_dev/actions/basics/now

$ wsk action get basics/now

{

"namespace": "openwhisk@sciabarra.com_dev/basics",

"name": "now",

"version": "0.0.1",

"exec": {

"kind": "nodejs:6",

"code": "function main(args) {\n return { body: Date() }\n}\n\n",

"binary": false

},

"annotations": [

{

"key": "exec",

"value": "nodejs:6"

}

],

"limits": {

"timeout": 60000,

"memory": 256,

"logs": 10

},

"publish": false

}

However, if we try to use the URL to run the action we may have a nasty surprise:

$ curl https://openwhisk.eu-gb.bluemix.net/api/v1/namespaces/openwhisk%40sciabarra.com_dev\

/actions/basics/now

{"error":"The resource requires authentication, which was not supplied with the request",\

"code":9814}

The fact is: all the actions (and everything else) in OpenWhisk is accessible with a REST API. However, by default, the actions are protected and not accessible without authentication.

However, it is possible to mark an action as publicly accessible with the flag --web true flag when creating or updating it. We call them web actions.

A web action is supposed to produce web output so that you can view with a web browser. There are some other constraints on Web action we discuss later. For now, focus on the fact the answer must have a body property that is rendered as the body of an HTML page.

Now, since our action was not a web one, we must change it. This case is an opportunity to demonstrate how the update command that can change an action. Then we can immediately retrieve its URL and invoke it directly.