Chapter 2. Chapter 2: Give Everyone a Role

In the last chapter, we looked at how encouraging diversity in a team helps generate and test ideas more easily and quickly, but can bring up conflict in some cases. Establishing clear roles for people helps channel their energies and can reduce unproductive tension around different responsibilities. In this chapter you will learn how to approach assembling different collaborators, and how to use explicit roles to channel different skills and impulses. Christina Wodtke, founder of Balanced Team pointed out that “we know how to channel people from a skill set perspective, designers design and developers write code. But, if non-functional roles aren’t delineated there’s guaranteed to be conflict.” She says clear roles deal with things like, “Who makes decisions? Who brings what perspectives? Who’s able to facilitate openly? Who will plan and track what the collaborators do?” Wodtke also acknowledges that roles are never a set-piece that can work anywhere. “Different collaborations will have different shapes,” she says, calling up classic comic book collaborations as an example. Stan Lee & Steve Ditko, early pioneers of comic book creation, approached writing and drawing together as two equals with different skills building one thing. Neil Gaiman the sci-fi and fantasy author on the other hand, will turn over a full manuscript for a graphic novel without really having thought much about or worked much with the imagery. Both approaches clearly result in quality output, but each is suited to the individual collaborators.

There are some conventional role definition frameworks can be used/adapted for collaboration success, as well as some roles that don’t typically get called out in such frameworks, but that are critical. At the end of the day, roles are a way to formally establish authority and scope in a way that the whole team can share in. The importance of roles lies not only in their ability to channel power dynamics. Defining clear roles also helps create growth opportunities for more junior team members, or those who are looking to grow their skills. One way to help people skill up in a role they don’t tend toward naturally is to try it out briefly. This can be especially useful if there is a group of 3 or 4 people who are co-creating something and there is a natural set of alliances that emerge. By “forcing” people to shift their role, they will also shift their perspective and perhaps be able to get beyond their default position to get to a breakthrough.

Next we’ll look at how roles help channel people’s energy and clarify boundaries and responsibilities within the team to keep a diverse set of people focused and productive. Roles should be defined for those who are fully focused on the effort as well as for stakeholders and experts that advise the team. Roles aren’t like job functions that are stable; over time, you may find that roles can shift to give people different experiences.

Levels of Contribution

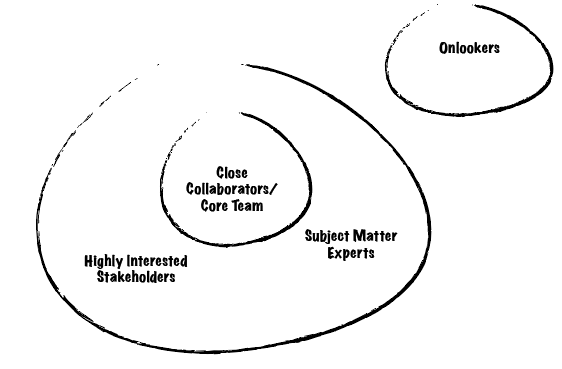

When you are enlisting many people, as we looked at in Chapter 1, you need to acknowledge that there is a time and place for many people to participate, but there are also times when a smaller, core group of people need to dive into solutions. It pays to be clear about different levels of contribution as shown below. (Figure 2.1)

Figure 2-1. A Model for understanding different types of collaborators

At the center, you have the inner circle of Close Collaborators who are doing the bulk of the heavy lifting, where a few people who are very close to the problem explore ideas and develop them to be tested. These are the people who are focused on the problem fully, and who have the diverse skills needed to create solutions for it. The roles here need to support a balance between exploring divergent ideas and converging and testing ideas in a way that is traceable and transparent.

Surrounding the close collaborators are Highly Interested Stakeholders who are collaborators in the effort, even if they aren’t directly responsible for delivering the solution. These people are affected by the outcome of the collaboration but aren’t actively participating on a daily basis. These might be those who manage a function that is critical, or who manage related efforts that have dependencies or related priorities. The biggest challenge that arises here is when these stakeholders are not clear on how they are to participate, especially senior leaders accustomed to having casual remarks about ideas or solutions taken are clear directives about where to go next. Establishing the lines of authority around decisions and how feedback is given is critical.

On the outside are Onlookers who are watching your collaboration even if they haven’t been invited to participate. This may be because they are inspired by the challenge, or fearful for being left out, or simply bored and looking for a distraction. While it can be tempting to ignore these folks, it’s useful to make sure you are communicating to this audience so they don’t become active detractors.

It’s important to point out that collaborators aren’t necessarily those within your direct organization. You are likely to have to include clients, or outside partners with specific expertise. There isn’t necessarily a big difference in how people work together from different companies, but it is worth noting that goals may be generally aligned but still not 100% the same. For example, a vendor you rely on for key technology needs a seat at the table, but success for them may be selling you more product over your end-product being successful.

Roles for Close Collaborators

From Agile, to Sprints, to Design Thinking, there’s a great deal out there about how to get close collaborators working well. I have found that, when it comes to making use of roles, the world of “pairing” holds a lot of value. Pair Programming is a movement that started with software developers, as a way to increase the quality of code and as a way to move quickly through a variety of approaches to a problem. Pair Design takes a similar approach to the architecture and overall design of a product or service. Pairing can be practiced by Designers, Developers, and Product Managers. In our book for O’Reilly, Pair Design, Chris Noessel and I look at how pairing works and show some variations of how it is practiced in detail. For our purposes, it’s less about people working in literal pairs than giving small groups of 2-5 collaborators structure for their participation in an intimate group. Below are roles that can help your team share responsibilities for working together as a core team.

The Navigator

The Driver(s)

The Historian

Critics

The Facilitator

Make like others?

Add key takeaways to each chapter

The Driver(s)

If the Navigator within a collaboration is focusing on the bigger picture for the group to explore, the Driver is the person (or people) working through possible solutions to the challenges within that space. They will be holding the pen at the whiteboard, or will be using the keyboard to write code or draw ideas quickly. Drivers are less concerned with tracking the flow or keeping the whole picture in mind than navigators, focusing instead on developing divergent approaches to a problem quickly, so that the pair can evaluate them.

Drivers are typically responsible for:

Technical solutions: developing ideas and creating them (in code, on whiteboard, etc.)

Expansive thinking: the team needs drivers to be able to develop multiple approaches to a solution rather than simply honing in on one. This is where having several drivers is useful.

Bringing expertise: drivers should have perspectives on the problem and solution space that is more specific

When assigning people the role of Drivers, you are looking for people who have enough technical ability to render their ideas quickly in some medium for the pair or small group to react to. Drivers should also be able to easily come up with multiple solutions to a challenge, not augur in on a single idea and argue it. Drivers should be:

Fluent in the medium: whether you are developing a new organizational model, or creating a new feature for a product, drivers should have the requisite technical skills and knowledge to create substantive artifacts.

Solution-focused: whether your driver(s) are extrovert who enjoy duking it out over ideas at the whiteboard, or more internal processors who need to work “offline” to generate ideas to critique, their job is to give options, not rehash assumptions or redraw the map.

Invested in group success: driving is not about winning. Drivers should be made to think they are the team lead or in competition to come up with the solution.

Not one work style. Note that not all drivers need to be highly verbal types who think on their feet. Drivers who are more introverted may need to develop ideas on their own, and bring them back to the group to share and critique.

It’s worth noting that at least during early stages, this circle of close collaborators may be 3 or 4, (or even 5, maybe!) people. When there are more than a handful of people who have a great deal of trust and respect, you are more likely workshopping ideas with a group that involves some stakeholders, rather than actually doing deep, close collaboration. In these cases, you should be very clear about who the Navigator is, and assign all others to be drivers. In a group of 3 or 4, you might try having people work “Alone, Together” as Jake Knapp calls it in the Google Sprint book. In this vein, rather than a pair work tightly out-loud on the problem, you would have people work for bits on developing ideas and sharing them, doing a critique led by the navigator, and then refining the ideas iteratively in the group. It is a good idea to state clearly that all Drivers in that setting are equals, even if there are technically more senior and more junior people in the role. As the master of collaboration, you can help the Driver or Drivers be successful by:

Killing Egos: model what it looks like to focus on group success; use group retrospectives to keep big egos in check and help others feel heard.

Together time/Alone time: Most successful pairing I’ve seen will have a schedule that might put people working closely together for a few hours in the morning, and then having them work independently in the afternoon. When they return the next day, they can check in about where each person got to.

Dedicated focus: like Navigators, drivers need enough time and space to take the ideas that the pair has worked through to the next level. If Drivers are people who are spread across multiple problems, you will find that they resort of “swoop and poop” behavior rather than being invested in the specific problem and pair.

Finally, when wrangling people in very close collaboration be aware that these roles can (and in some cases should be) fluid. Especially later in the process when the collaboration is about specific implementations of solutions, as opposed to a big vision, it can be useful to have people take different perspectives and switch often. Sometimes this happens naturally. When observing pair programming, I’ve seen two people working the same keyboard and mouse because each person is very familiar with the problem and each of them has skills or expertise that is specific to solving the problem. There are also pairs who fit so naturally into the roles that no swapping happens. Often if one of the collaborators is a product manager, or other generalist skill set, they will fit naturally in the role of Navigator, and won’t have the technical expertise or fluency to be a driver. If you are filling one of the roles of close collaboration, make sure you yourself are keeping to your assigned role, and check in often to make sure you haven’t lost sight of the path you are navigating.

The Historian

Every good collaboration lives and dies on its ability to tell it’s story well. I’ve found that good stories don’t write themselves, and while everyone thinks they know how to tell them, they never make the time. At crunch time, it’s the artifacts and prototypes that pull our attention. Do yourself a favor and nominate someone to be the Historian for the group. This isn’t necessarily the person who tells the story, but who helps craft it. Historians keep great notes about the trajectory of the collaboration so that when it’s time to pull the plot together, you’ve got good reference material.

Historians are primarily responsible for:

Tracking the decisions, arguments and “ah-has” of the team

Taking a longer view of the work, noticing how it changs vs. getting stuck in the present moment

Knowing what’s been communicated, to whom

The Historian is a great role to give to someone who is looking to grow their skills and learn to do more than contribute technical or subject-matter expertise. Good historians will be:

Invested in people: from the team, to the users, to the key stakeholders, these are people who are curious about how people think and take in information. Researchers are often well-suited to this role.

Detail-oriented: while you don’t want this person to be a “note-taker” who just transcribes every blow-by-blow, you do need them to capture more than the final outcomes over time.

Synthesizers:

Historians may consider themselves to be in a “support” role for the team, when in fact their contribution is critical, and requires many leadership qualities. You can help Historians be successful by:

Giving them time to recap every session: it’s hard at the end of a long session together to find the energy and time to recap key moments. We love to focus on action items and next steps, instead of talking through what the key moments were.

Plotting out the story: alongside the artifacts and prototypes, help the historian write out why the outcomes matter, to whom and how they unfolded

Critics

We’ve all had the colleague who just can’t help but shut down every idea that they encounter. Whether it’s because “we already tried that” or “it’s not possible,” they’ve never met a solution they didn’t like. Their energy isn’t just annoying, it can infect the entire group by making people doubt themselves or tire them out having to debate endlessly with someone who won’t engage.

Explicitly giving someone the role of being the Critic, can turn their negativity into something productive, but it takes some doing. You must first decide when to assign this role. If you know that someone important to include is likely to be a naysayer, approach them ahead of time and tell them you specifically want them to play this position. Be sure to frame it as a critical part of the process, to harness their expertise to find weaknesses in the solution set so they can be refined.

If the resistance appears during the process of defining the objective or generating divergent options, you will have to try to reframe their participation after the fact, which can be awkward. I find it helpful to explain the overall process and timeframe of the effort, and be clear about when they will be called upon. You can give them a specific meeting, or series, with the group for them to “lead” their critiques. It’s important to remove them from the meetings where that energy won’t be welcome. I tend to say something like, “you can skip tomorrow’s session. We’re going to be doing more brainstorming which is going to drive you crazy. Why don’t you do something more important and we’ll share what we come up with afterward. We’d love to hear your thoughts in next week’s session.”

The trick is elevating their negative energy into an official part of the process. Help critics feel valued and be useful by:

Being rigorous. Give them specific guidance on how to frame their feedback. List out specific questions you are looking for them to answer about the work so they know where to focus. It also helps to be clear about where in the process the work is, and what assumptions you’ve made along the way.

Letting them air out their reservations. Don’t give into the tendency to argue with their critique. The points that are valid can be used to make solutions stronger. Points that are conjecture or strawman arguments can be ignored.

Giving them dedicated space. Ask critics to lead a specific session to tackle ideas, not while generating options. It can also be useful to ask them to write down their arguments, or comment on what others have written rather than do it all face to face.

Testing their theories. Remember that in general, the critics arguments are just as much a guess as the ideas they attack. Enlist the critic to help test ideas out and identify what evidence would be needed to know when an idea is good, bad, or impossible.

Celebrating their improvements. When critique does make ideas better, be sure to call that out. That is something the whole team should feel good about.

The Facilitator

In addition to a Navigator, you may need a separate facilitator to guide discussions, most often when the core of close collaborators are bringing in stakeholders or subject matter experts to explore ideas and give feedback. It’s worth noting that most experts in facilitation see the core responsibility of the role to guide the process, with less focus on the content of the problem area or solution. Appoint a Facilitator to wrangle larger groups, especially if there are many different levels of seniority, authority, and expertise coming together. If you or those you work with will not be seen as impartial, and the challenge is highly charged or political, consider hiring a facilitator, or finding someone in the org who is seen as impartial and who can be a trusted facilitator.

Facilitators are primarily responsible for:

Structuring and managing time

Keeping focus on the material and appropriate topics

Keep discussions and decisions visible, working with navigator

Helping the group make “Lasting agreements”, move through the diverge/converge process as a group

When choosing a facilitator, look for someone who can stay above the fray, and keep the big picture in mind. You, as someone who is curious enough about successful collaboration are a likely candidate for this role. Facilitators have three key traits:

Above the fray: A facilitator is a guide to help people move through a process together, not the seat of wisdom and knowledge. That means a facilitator isn’t there to give opinions, but to draw out opinions and ideas of the group members.

Invested in the team: Facilitators focus on how people participate in the process of learning or planning, not just on what gets achieved

Open-minded: A facilitator is neutral and never takes sides

If you feel like you aren’t this person, or maybe don’t feel like you have enough political clout to pull it off, being the Navigator is another role to consider where you can hone your leadership skills, not just technical skills.

RACI Models

In many organizations, a model known as RACI is used to organize decision-making. To summarize it briefly, RACI is an acronym that encapsulates each of the key roles:

R = Responsible: The person responsible for delivering the desired outcome

A = Accountable: The person accountable for the outcomes and any associated risks

C = Consulted: often the meat of the team, those consulted include the functional experts, subject-matter experts, and even actual users

I = Informed: Those who should know about key decisions, who need to understand what has occured but who aren’t directly responsible for the effort

Responsible: the person who fully understands the challenge, the desired outcome and who is accountable for the success of the effort. Without this person being adequately incented to make “winning” decisions, without them being accountable, they serve more of a facilitative role. As the person who arguably is closest to the problem and the possibilities, they benefit from having the risk/reward of making the right decisions, or more likely, learning from decisions to get to the right decision.

Accountable or the Advisor: the person (or people) who are positioned to understand the risk implications of different decisions, who have veto authority, and who are aware of how outcomes affect the company. I have found that while the CEO might be ultimately accountable for a decision, giving them the explicit accountability means they rarely have enough information to question the ideas of the Driver. To this end, making them as Advisor who can veto or challenge ideas sets them up as a contractive foil to the D, and less likely to blindly accept their recommendations or argue for argument’s sake.

Contributors: These are those who are responsible for actually developing solutions to challenges and seeing them implemented. These will certainly include the close collaborators we looked at previously. It may also include those who are responsible for aspects of the solution that are dependent or highly-related but adjacent to the core solution such as DevOps Engineers or members of the legal team. Often the group of contributors, are actually those who inhabit the creation-oriented roles described above such as drivers or passengers or critics.

Informed: This group tends to be overlooked and dismissed in the (mistaken) assumption that they are less important that those above. However, as we will see, and you likely have experienced, if those who should be informed don’t feel adequately prepared, they are likely to become bottlenecks or adversaries who need to be won over after the fact.

You may have seen or read about this model as DACI, instead of RACI. In a DACI model, the R becomes a D for the Decider or Driver of the effort. Given the previous discussion of pairing or close collaboration, I will use the RACI “Responsible” to avoid confusion about this role. In my experience, and in the experience of those I spoke with, the differences are negligible between the two sets of acronyms. The key is to assign different focuses between those who have a great deal of accountability for a solution, but little hands-on time or experience and those who work a problem directly. Having seen this model employed in many different settings, I have seen it provide healthy clarity around decisions, and helps teams work in smaller groups with less friction with those who are Interested and perhaps want to be more than Informed.

Assigning Roles and Understanding Skills

While RACI roles tend to be obvious to assign based on skills and hierarchy, roles for close collaborators may be less clear. Roles are simply a tool to get a wide variety of people with different perspectives to work together with less friction. To that end, you need to get to know folks in order to figure out where to put them.

Things to consider when assigning roles and putting the group together:

Expertise and skills. You need a variety, but also need to cover what’s required to get the job done. Even if you can’t get full participation from someone with critical knowledge or abilities, see what time and attention you can get rather than trying to make do.

Ability to think on their feet vs “offline” and on their own. If the entire group loves to debate verbally and intensely, you may find that ideas are being chosen based on that public performance, without careful analysis. See who might be able to work offline or in writing to bring a different lens.

Language proficiency. If not everyone shares the same native language, see if you can get the group to use simple words and syntax, avoiding acronyms or abbreviations that won’t be well-known.

By being thoughtful about how you place people in a team, and being prepared ahead of time, you can channel people’s energy more productively.

Troubleshooting Roles

Assigning roles and getting people to stay in them is key to keeping people aligned and coordinated. Below are ideas for how to handle issues within the core team and with stakeholders.

Assumed Hierarchy in the Team

While there’s nothing inherent in any of the roles I’ve described above that specifically calls out one as more important than another, people may still think that way. Because our corporate culture tends to celebrate individuals who lead by speaking frequently and making decisions, it’s natural to assume a hierarchy that doesn’t need to be there. After all, no one can make a well-informed decision about something complex without the hard work and expertise of contributors who put in blood, sweat, and tears to lay out the options. While according to the org chart there may be actual hierarchy in a group, the point of roles is often to establish different, more inclusive lines of authority that make room for those “at the bottom.” When people start assuming that some people are more important than others in a collaboration, it’s not just a morale killer, it’s a perspective killer.

So What Can I Do?

Rotate roles. One way to make it clear that all roles are valued, as are all people in a team, it’s useful to have people swap roles from time to time. This is less applicable to the RACI roles which should stay stable among a group of people who aren’t working an issue day-to-day. But asking Navigators to be Drivers for a cycle can help people see the value of both roles. It’s also a good way to give people experience doing things they may not naturally be drawn to, or excel at. Asking someone who’s used to only generating ideas, to serve as the “big picture” person for a while, may give them some empathy for how hard that role can be. Vice versa, those who don’t think of themselves as “creative” may be surprised at their ability to open up when they freed up from charting the team’s path.

Model and celebrate being a “contributor.” When RACI roles are assigned, there’s often much more attention paid to who gets to decide things, and who gets to advise on or veto them. You can help draw energy away from these roles, by calling out key contributions that the team needs, whether it’s expertise, or key deliverables. When you yourself are a contributor, take great pride in knowing that the “real work” you are doing is what moves the needle as much as any leader. Any many good senior leaders are very willing to share the limelight, and call out the efforts of contributors, especially if you ask them to.

Roles Get Ignored

Just because you’ve assigned roles, doesn’t mean that they are always respected. Especially over time, people can fall into natural ruts, and let roles fall by the wayside. Or, people take on responsibilities that rightfully belong to others because they are easier, or seen to be more prestigious.

So What Can I Do?

Look for a mismatch. You may have a person who’s been put in a role that’s a bit of a stretch for them. Perhaps that was an intentional move to give them a growth opportunity, or perhaps they over-committed themselves. It may be worth revisiting roles and adjusting responsibilities temporarily, or for the longer term.

Commit to responsibilities as a group. If it feels like the person or people aren’t “staying in their lane” out of laziness or willful ignorance, it’s worth having the group periodically review different roles and commit to them explicitly. When people are made to sign up to something publicly, that gives the group the ability to hold them accountable, or give them the needed prod to hold themselves accountable.

Conclusion

Roles help channel people’s energy and clarify boundaries and responsibilities so it’s worth taking the time to define them and make sure they are understood. Having a set of roles for close collaborators will help them work through defining problems and generating ideas. For stakeholders and other interested parties, RACI roles provide structure to discuss and decide productively. It’s important to note that roles aren’t positions, and can and should flex over time, giving people different experiences and adjusting to where the groups focus is. In the next chapter we will look at how to help teams develop trust in each other to help them when things get tough or uncomfortable.

Key Takeaways

Collaborations include differing levels of contribution. Not everyone is focused on the problem full-time, so it’s good to discern between the core team of close collaborators and the stakeholders and subject-matter experts that support them.

Close collaborators need roles that keep them focused on their contributions when defining objectives and exploring ideas.

The Navigator roles holds down the big picture and directs the teams efforts to explore ideas and generate solutions to be tested.

The Driver(s) role focuses people on the solutions to the problem and thinking creatively.

The Historian roles keeps track of what the team has done, and what it has discovered to help tell the story later.

Critics are those who help evaluate ideas and bring in constraints to make them stronger.

The Facilitator role focuses on the process and team dynamics rather than the content of the collaboration to keep things flowing, and keep conflicts productive.

For stakeholders and subject-matter experts who might be tempted to be overly prescriptive and dictate solutions, the RACI model helps with making decisions, establishing accountability, and knowing who should be informed.