Building Effective Product Teams

Copyright © 2019 Gretchen Anderson. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492041733 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Mastering Collaboration, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-04173-3

[LSI]

Now I know what you’re thinking: Everyone? That sounds...messy. In meaningful collaborations “everyone” cannot literally mean everyone, but as a principle it’s worth realizing that the more you include people who are affected by, and invested in, the topic at hand the better your results will be. Enlisting everyone, done right, actually helps.

It’s counterintuitive, but casting a wide net and including more people, actually helps you move faster. Because, consider for a moment that everyone is already “helping” you. They just aren’t doing it in a way that is actually helpful. Group dynamics, especially in competitive corporate culture, lead people to see efforts that exclude them as potential threats or a drain on resources that feel tight. At first, the people that you have not engaged (for whatever reason) might stand off to the side, neither helping or hurting your efforts. But it doesn’t take much for those who’ve been made to feel excluded to stake out a position on the opposite bank, and work against what you are trying to create. Often we assume anyone not working with us are neutral parties, but if those parties think they should be involved, they won’t stay neutral. Often in a rush to just “get to it” we leapfrog over interested parties, only to find that we must spend large amounts of time and energy trying to get their buy-in later. Their participation often takes place after the fact, as combative reviews of “finished” work, or worse, competitive efforts spring up and muddy the waters.

This isn’t necessarily because these people don’t believe in what you are doing. Rather, their reaction is a normal response to having a perspective that isn’t being heard. When we have a real interest in an effort, we can’t help but want to contribute, and if we aren’t given a chance, it can bring up an emotional response that is hard to corral productively. By engaging “everyone” in approaching a problem, you increase their commitment to the end-product and you reduce the drag on momentum.

Including “everyone” doesn’t mean every person is always fully involved, it means widening the funnel of inputs to the process, enlisting varied perspectives to generate solutions, and getting a larger set of people to vett ideas to find their faults and make our case stronger. Everyone can help if you can help make room for different perspectives and ways of engaging. Some people may be dedicating their full attention to the problem, pushing solutions forward, others may be advising or providing feedback on work. The purpose of including everyone is to get a sufficiently diverse set of perspectives on a problem to mitigate risks and drive innovative solutions.

This chapter will show how being more inclusive makes teams stronger by widening their perspective and making them more invested in the team’s success. Managing groups that are very different can present some challenges and create conflict. You can take steps to help teams work through their differences, at least enough to make working together less painful.

A recent “innovation” from Doritos stands as a great reminder of how limiting the variety of orientations to a problem can have ridiculous results. The maker of tasty chips completed some customer research, and found a surprising problem. Women reported not feeling comfortable eating Doritos in public, saying that crunching loudly and licking the delicious chemical flavor powder from dainty fingertips just didn’t seem ladylike to many. So the brand announced a plan to address this problem by creating Lady Doritos – a less crunchy, less finger-lickin’ good version of the product. They had successfully dealt with every every issue identified. Or, had they?

Now, mind you, the problem wasn’t that women weren’t buying the chips, but that they had an aversion to eating them publicly. Both the analysis of the findings, and the proposed solution stink of a team that lacks diversity. And I don’t mean women. I suspect that those involved were all “product” people whose only hammer is a new product type, and every nail a gap in the product line. Thankfully, the Internet shame that surrounded this moment kept this idea from moving forward, but Doritos could have avoided the PR gaffe if they’d included people not responsible for product development. Because the issue is a messaging opportunity, not a product-market fit problem. A simple ad campaign showing women gustily enjoying chips in meetings, at the park, on the bus, all while smiling and laughing would have gone a long way, and probably requires a lot less investment.

Blair Reeves, head of product management at SAS and author of Building Products for the Enterprise: Product Management in Enterprise Software, says sometimes, the blind spot comes in defining the very problem itself. Prior to getting into product management, Reeves worked in international development in Cameroon. He recalls how projects to improve infrastructure among communities was often without partnership from the people. People were used to having solutions provided that may not be used or sustained once finished because they weren’t seen as something that they had ownership of. When he began asking communities about their priorities, he found that they were different than had been assumed. AIDS and HIV education weren’t as big issue for them as his organization assumed; instead the people wanted help with combating malaria and building latrines – issues that were more disruptive day-to-day.

Asking a diverse group of those who are closer to the problem is one way to spot potential missteps and avoid them. A group that’s too homogenous may miss incorrect assumptions or apply too narrow a lens to finding solutions. You should also make time to be sure that the team understands, and seeks out the right skills sets, rather than assuming they are present or trying to “make do” blindly.

[sidebar 1.1 Balanced Tam Pie]

It turns out that including those who are affected by the outcomes of the work is also a boon to morale. When Reeves not only discovered the community’s real priorities, he also found that when he started asking people about the problem, that they were easier to engage in the solutions. Those we work with are no different. When you can invite more people into a thoughtful consideration of a problem, or enlist their help testing solutions they become more active and interested. It seems obvious that when people are only shown finished work and informed of its existence they care less about it – unless of course they actively hate it. And yet, sharing finished work that can’t be changed much is standard for many office cultures.

Companies know that having more engaged employees is beneficial, it’s why they spend so much time and money measuring engagement. Marc Benioff of Salesforce found his organization faced with a challenge of employee engagement at senior levels of his leadership, something that corporations pay a great deal of attention to. Higher engagement can multiply productivity and quality so much that substantial amounts of time and money is spent monitoring and supporting people’s experience at work. Benioff wanted to nip his engagement problem in the bud, so he took pains to create a virtual space to understand what fueled the issue and define the problem and address it. “In the end the dialogue lasted for weeks beyond the actual meeting. More important, by fostering a discussion across the entire organization, [he] has been able to better align the whole workforce around its mission. The event served as a catalyst for the creation of a more open and empowered culture at the company.” Clearly senior leaders at Salesforce are busy people whose typical focus is on the products and services they create, but without spending time to come together widely as a group and establish shared understanding and priorities their day-to-day efforts would have been affected.

Collaboration is an approach to problem solving, but it’s just as valuable as a cultural force that helps employees engage with purpose and meaning in their jobs, not just productivity.

So, maybe enlisting “everyone” has some advantages, but employing this principle can also bring up issues around diversity and inclusion for the group, and as a master of collaboration, it is important that you stay aware of dynamics that can reduce the benefits.

In studying cultural differences, there’s a force known as the Power-Distance Index, first identified by Geert Hofstede, which measures the degree to which a group values hierarchy and ascribes power to leaders. A country like the US has relatively low Power Distance because we value flatter organization and independence over bowing to authority. Japan, on the other hand, rates very high, as the culture demands a great deal of respect for elders and authority.

Malcolm Gladwell in his book, Outliers, tells the story of Korean Air’s “cockpit culture” during the late 90s when the airline was experiencing more plane crashes than any other airline. Analysis showed that the cultural norm of giving into superiors and avoiding challenging them meant that junior pilots who spotted problems failed to raise them, In Forbes, Gladwell said, “What they were struggling with was a cultural legacy, that Korean culture is hierarchical. You are obliged to be deferential toward your elders and superiors in a way that would be unimaginable in the U.S.

But Boeing and Airbus design modern, complex airplanes to be flown by two equals. That works beautifully in low-power-distance cultures [like the U.S., where hierarchies aren’t as relevant]. But in cultures that have high power distance, it’s very difficult.”

When the airline made some adjustments, their problem went away. They flattened out the power-distance index by reinforcing the value of junior aviators, and, “a small miracle happened,” Gladwell writes. “Korean Air turned itself around. Today, the airline is a member in good standing of the prestigious SkyTeam alliance. Its safety record since 1999 is spotless. In 2006, Korean Air was given the Phoenix Award by Air Transport World in recognition of its transformation. Aviation experts will tell you that Korean Air is now as safe as any airline in the world.”

How we react to power isn’t the only cultural difference you’re likely to run into. If you’re beginning to see how widening the circle of collaborators and making sure they are active, respected participants, you might be wondering how to define the right level of everyone for your teams. Getting diversity means including those with a variety of:

Experiences in industry and skills

Cultural backgrounds

Introversion and extroversion

Working styles

Primary languages

Ownership, from end-users to senior leaders and everyone in-between

Helping teams deal with cultural differences requires being open to talking about differences, creating norms that bridge gaps, and having productive conflict. When people can acknowledge to themselves and others where their perspective is coming from, it makes it easier for the group to not reject it because it’s an outlier. Discussion about how the group will handle certain differences is also a healthy thing to promote. Creating explicit norms about everything from group vs. individual working time to how decisions get made gives the group common ground. It’s important to model respecting team norms, and hold each other accountable when they aren’t respected.

[Sidebars 1.2 and 1.3]

At some point in your journey to master collaboration, you will have a realization - people are a problem. Working with power structures can be challenging, especially if you don’t happen to have a lot of authority in the system. And people are irrational and messy, which is why organizations create structures in the first place, to help guide our decisions and establish ways to control and command. Cyd Harrell knows all about these kinds of structures as someone who has made a big push in the last few years to bring innovation and inclusivity to the US Government. As a leader at 18F, the digital services arm of the government, Harrell has worked with huge governmental agencies, elected officials, and political appointees, and she’s seen first-hand the challenges of bringing a collaborative approach to command and control cultures.

“Some kinds of hierarchy are not conducive to good collaboration,” she says, “but you have to find a way through anyway. That culture exists for a reason, and many of your stakeholders have a great deal invested in it.” It’s important to note that not all organizations are chasing less hierarchy and flatter structures. Civil servants and government agencies typically have a much longer tenure than you find in Silicon Valley, and many people work hard for years to attain a level of authority and power that they aren’t eager to shove aside in the interests of being “transparent” and non-hierarchical. These organizations have succeeded in large-scale often high-risk situations because they employ what Harrell calls a “submit and review” approach where ideas are taken to a final state where a gatekeeper has the power to approve or reject the work in a single blow. In that model, more senior people are seen as experts whose point of view is critical to be aligned with. Conversely, those who are elected or appointed, might serve short tenures, with a great deal of authority, and priorities and perspectives change once that person has been replaced or voted out of office. Both of these forces tend to make collaboration hard, or nearly impossible.

But, Harrell says, at the same time, you can’t get around these cultural forces. Approaching collaboration in this setting without respecting the system and structures is likely to have bad effects. When I offered some ideas I’ve seen used to break through power imbalances and help create a different vibe in a team, Harrell was quick to correct me. “You can’t make changing the culture central to your success” in an environment where so many are so invested in its structure. And trying to go around it might end you up in hot water, having violated the chain of command by going to a senior influencer. Asking people lower on the totem pole to speak up in front of more senior people can also backfire, since the system doesn’t reward new ideas as much as it rewards supporting the hierarchy.

The US Government is one specific culture, and Harrell has learned how to navigate it, rather than fight it during her tenure. Her approach is a simple one, bring great deal of empathy for your stakeholders, however reluctant, and don’t force it. Rather, create a space where the rules and systems are paused or changed temporarily and invite them in. Or ,run your collaborations cloaked within a command and control mode where you slow down to the pace required to continually seek reviews and approvals from those who matter more than others. The trick is to acknowledge to yourself and the team, that the situation simply requires another iteration or two to bring the sticky stakeholder along. Since you are always showing “finished” work, you must be willing to be “wrong” so that a meaningful conversation can be had about what’s not working and how it might be fixed.

But cultural differences can also be more geographically influenced, in teams that are large and international or dispersed. Erin Meyer is an author and researcher who’s done a lot to map out the ways in which cultures differ which in turn helps you navigate them. Her work is useful for those who are navigating national cultural differences in teams, from how negative feedback is given to how scheduling happens. More typically, teams are made up of many different cultures, so it may be more useful to focus on mapping individual behaviors than focus on countries of origin.

Some companies have collaboration build into their cultures from the start. Netflix began with an unusual business model, mailing customers DVDs of movies from their queue, and made the transition to streaming media at a time when physical media was losing adoption. The company has recently undergone another transition and begun creating it’s own movies and TV shows to stream. The resilience of their business model and technology are impressive, and much of the credit for the company’s success is attributed to their strong culture that values collaboration highly. This culture is embodied in a famous “deck” of slides that was shared openly on the internet and is now published on the company’s website. Andrea Mangini, Director of Product Design, shared her observations about how that culture works on the inside, as someone relatively new to the org. She says that people are constantly showing their work and inviting people to weigh in. People value getting feedback, and in fact not seeking out the opinions of others is frowned upon. Because the emphasis on collaboration has been at the core of the company since the start, it’s second nature to many people. The company sees so much value in breaking down silos, they worry less about duplication of efforts and optimizing the creation of new ideas.

No matter what environment you exist in, by being intentional about involving “everyone” and making it possible for differences to become productive through norms, you get the diversity you need, while maintaining the sanity you deserve. By understanding power differences, and openly discussing cultural differences, whether they are based on nationality, or background, or skill set, you will help create a more harmonious collaboration.

Bringing many different people together can bring up many emotional and interpersonal issues in the team and with stakeholders. Below are some ideas you can use to mitigate these issues and keep the team focused.

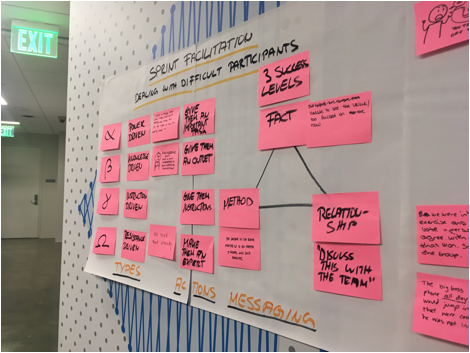

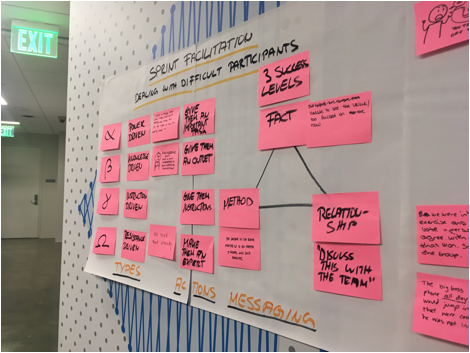

However you’ve decided to set up your core team, it’s likely that at some point, one or more of them will turn out to be trouble. Whether it’s someone who dominates, or those you can’t seem to get to speak up, difficult people are a fact of collaborative life. Thorsten Borek and his team at Neon Sprints in Hamburg, Germany have created a simple framework to understand the problematic people who show up to collaborate (or not, as we will see). I have recreated their framework here with permission because it’s simply too useful not to share. The framework has four main types of difficult people, and ways you can handle them gracefully:

The Leader

The Know-it-All

The Introvert

The Negativist

The Indecisive

The Leader. This person is someone who can’t help but take over in a meeting, controlling conversations, dominating ideas. Whether they are literally the boss or just act like it, their presence is likely stifling to others and a pain to facilitate. The key to this person is to understand that their motivations are power-driven, meaning that they seek to be seen as powerful by others. To handle an Leader, Borek suggests giving them an important task. The key word being, important. These folks should be asked to lead a discussion about key decision criteria, or to be asked to make critical decisions.

The Know-it-All. Know-it-alls show up as those who constantly drag the discussion in a specific direction or bring up what seems like minutia when the group is talking about the big picture. They make other participants cringe because they take things off-track even though they may be saying important things. Understand that they are knowledge-driven, and need a way to channel and share their expertise with the group, productively. Handling betas means giving them an outlet in a collaboration. Consider giving them a chance to present their knowledge of constraints as part of framing a problem, or let them share insights about a specific technology you are considering. Truly disruptive people may need to be handled with care, and only included in places where they won’t drown everyone else out all the time.

The Introvert. You may not always notice introverts as problems in your team, because gammas tend to be nice and quiet, eagerly following along, and agreeing with whatever the last person said. Introverts are instruction-driven, meaning they may not be extroverted or confident enough to participate in messy, free-form discussions. Giving them very clear instructions, or doing an example of an exercise together before asking them to do it on their own will help build up their comfort level and confidence. They can also be enlisted to help out the group in many ways, since they highly value helping the group get along.

The Negativist. Finally come those who no matter what, can’t help but resist what is happening every step of the way. These people will question the process being used ad nauseum, or insist that every idea offered has already been tried. Often these folks are resistance-driven because they’ve not been listened to, either by you, or others in the past. Handle negative people with care, making them into valued experts, and enlisting them to prepare and strategize ahead of time. But these people may also prove difficult to change, so consider asking them to serve as a critic of the effort, rather than an idea generator to best take advantage of their energy.

The Indecisive. This type of team member typically is well integrated in how the team works and eager to participate in discussions. Frequently they will introduce different perspectives on a subject or ask to consider more aspects of the matter at hand. However, when asked to make a decision they have really hard time to make up their mind. And once they do decide in 9 of 10 cases they will ask to change that decision after a few minutes. Potentially asking the team for more input “just to be sure”. The Indecisive team member is safety-driven and they need constant reassurance with regards to proceedings and decisions made.

Messaging. Borek also breaks down how to position what you want to different types of people, depending on their orientation to what they value.He posits three ways to succeed in your messaging (Figure 1.1). Those who value facts respond well to descriptions of the outcomes that the joint effort will produce These people want to know what will be different in the future if all goes well. Others are more interested in methods; they want to know what an approach has a great pedigree, and respond well to hearing a step-by-step plan of how to get there. Those who value relationships are likely to want to “ask the team” what they think about a topic, seeking a more democratic and people-oriented approach.

It’s worth getting to know your team members and stakeholders well enough to understand what they value, and what drives them. You can do this in a variety of ways, from 1:1 interviews, to asking people who have experience with individuals what they think, to trying out different approaches and seeing what works.

This is the person who despite your invitations, just won’t show interest or participate in the effort. Many I spoke to described this experience of an important stakeholder, or person with subject-matter expertise fail to attend even short sessions, and sometimes expressing deep skepticism of the enterprise.

The cause of this lack of engagement can vary. Often it is just that they have competing priorities, and yours doesn’t rise to the top of the pile. This happens with people whose expertise is in high demand; and when I dug in with one such person I learned that their days had a Groundhog Day quality where they were called upon over and over again to deliver the same perspective, the same information across many groups, and each new request felt even less interesting and valuable than the last.

So What Can I Do?

Understand their priorities. When you can’t get the attention of someone critical to the effort, it’s worth spending some time trying to understand what they are devoting attention to. You can frame your project in ways to align with what they care about to get more support. You can do this by speaking with them directly, but if they aren’t engaging with you, try speaking to those around them who are likely to know what their focus is. And it may be necessary to acknowledge that their other priorities are more important. You may need to wait until they have the time and space to devote to your effort.

Burn a cycle. When a key stakeholder won’t give you the time of day because they don’t believe the work is needed, it probably won’t do to try to force them to play ball. My advice is to run through a cycle of exploration to get quickly from the fuzzy front-end questions and assumptions to asserting a hypothesis about the solution, or creating a prototype. This answer need not be (and probably won’t be) the right one, so beware of investing a lot of time or making it very high-fidelity. But, what you might find is that once you assert a “truth” developed by the collaboration, you will suddenly get their attention. And beware, it’s likely to be negative. But, this is the time to make sure that person feels like their input and guidance is what will make the difference in solving the problem. When I work with people in complex domains, I often show them things early on that are wrong or incomplete so that they will be compelled to step in to provide guidance and fill in what’s missing. If you prepare yourself to take an extra cycle or two to draw people in, you save yourself the frustration of having more finished work “rejected” by someone who could have been helpful earlier on.

Join forces or have a runoff. As a consultant, it’s shocking the number of times I’ve been hired by large organizations to work on problems that had redundant efforts going on. When you discover this consider merging or aligning your efforts with the other team, in the spirit of sharing the load to move faster. Or, alert leadership about the duplication, because it may be something they aren’t aware of. In my experience however, this isn’t always a case of the right hand not knowing what the left hand is doing. In some companies, they are intentionally setting up different teams to see what different solutions they can get. In this case, you should know your work is in a runoff, and proceed anyway. It may be a good idea to make sure that the comparison of the ideas is on an equal footing though. Try to ensure that leaders aren’t going to end up comparing the cookie dough from one team with the fresh out of the oven cookies from another.

Having team members who are spread too thin will stress any team. One of the strengths of Agile / Sprint methodology is the insistence on 100% dedication to the team. This is a great goal, but all too often I run into people who have too much on their plates. When your collaborators have varying levels of dedication to the cause, you may run into resentment (“x isn’t pulling their weight”) or dismay (“I want to do more, but I can’t!”).

So What Can I Do?

Speak to a manager. You can try to ask the person who oversees the employee to help clear the person’s plate, for everyone’s sanity. Don’t do this behind the employee’s back, but rather include them in the discussion about how everyone wants to make sure priorities are aligned. This isn’t the employee’s problem, it’s the resource manager’s.

Spread the gospel for them. When a key player is trapped in a cycle of being the subject-matter expert, you can help them by aggregating some of their requests for them, and aligning their input sessions (at least up front) into a single learning session so they can get off the hamster wheel. You could also offer to attend meetings with other groups to consolidate. And, while you are there, consider taking video, and compiling great notes that they can use as a first line of defense for requests for their time. This should also serve to create a bond that hopefully they feel the need to repay you for but giving you just enough attention later.

Change their status. If someone really can’t be spared the needed time to focus on your collaboration, then it’s a good idea to be explicit about making them an advisor who can review and weigh in, but who isn’t part of the core team. It’s also worth seeing if they have a protegé or colleague who might be better able to participate, even if at a lower-level of expertise.

The main objective of many personnel managers is to minimize dust-ups between employees and promote healthy teams. The irony being, of course, that avoiding conflict ends up creating more issues than it solves. If the business of business were really without contention, and everyone agreed, then we could have delegated it all to the robots and retired in our utopia long ago. But the reality is, we need to express and work through differences of opinion to get to better answers – the very heart of what this book is about.

But what happens when your teams, whether intrinsically, or based on coaching, won’t fully engage in healthy debate? If you notice that there are few points of disagreement in your team, it’s time to stir the pot. Otherwise, productivity will actually suffer, as energy spent not-arguing takes away from accomplishing goals.

You need to strike a balance among team members where there is productive tension and conflict about specific ideas not individual people.

So What Can I Do?

Talk cross-culturally. A lot of what underlies the willingness to speak up, or not, may be cultural. In the spirit of openness, it might be a good idea for your team to spend time together talking openly about what their expectations are, and sharing their previous experiences. Erin Meyer has fantastic advice in her book, The Culture Map, and online about helping teams embrace productive conflict despite cultural differences. She suggests using specific language like, “help me understand your point” in place of, “I disagree with that” to depersonalize and invite intellectual dsicussion among those who might otherwise give in. https://www.erinmeyer.com/2012/04/managing-confrontation-in-multi-cultural-teams/

Map it out. Meyer also suggests mapping out the differences in the team explicitly. The diagram below is specific to national cultural differences, which may be both irrelevant and overly simplistic for your purposes. But if you replace the nationalities with specific team members and their individual predispositions, you can use this tool to help the team better understand where each other are coming from.

Remove the boss. Some people may be more reticent to express themselves when someone of authority is in the room. Help your diverse teams feel comfortable by making sure they have space to engage with each other where they don’t feel like they are being watched or need to align with a superior.

Team norms. Establishing team norms about things like when meetings will be held, or what the “definition of done” is, is a key practice. For managing conflict, it can be good to discuss and decide what the team considers healthy, and not, when facing a conflict. I’ve seen teams with norms such as, “Ask for explanations over offering attacks” that are the result of a diverse team striving to be inclusive of different views.

Work asynchronously. Some conflict comes when people try to do too much all together. Keep an eye on people’s energy levels, and be aware of those who may do better work on their own, and then come back to share and critique. Make time and space for people to be away from one another and keep their discussion focused on the content of work and decisions.

Collaboration at the core is about including diverse perspectives and people. Being inclusive makes teams stronger; you have more to draw on and get more people invested in success of the effort. But groups often need help bringing their differences together productively. You can help teams be open with each other and develop shared norms to govern behaviors. You can also model what respecting differences and healthy tension looks like so that the group doesn’t just stick to what’s “safe” because it’s easier. In the next chapter, we’ll look at how to give people clear roles to channel their energies and contribute to a healthier environment.

Being inclusive of many different kinds of people, skillsets, and perspectives is a core part of collaboration that helps mitigate risks, engage the team, and find blindspots before they become a problem

Inclusivity can challenge the status quo of how people interact and may bring about interpersonal conflicts that are destructive to the team

Working in different cultures that aren’t naturally conducive to collaboration is challenging, but don’t get causght up in making changing the culture your mission. Instead, focus on keeping the team productive to deliver results. Culture change will happen as a by-product of good results over time.

In the last chapter, we looked at how encouraging diversity in a team helps generate and test ideas more easily and quickly, but can bring up conflict in some cases. Establishing clear roles for people helps channel their energies and can reduce unproductive tension around different responsibilities. In this chapter you will learn how to approach assembling different collaborators, and how to use explicit roles to channel different skills and impulses. Christina Wodtke, founder of Balanced Team pointed out that “we know how to channel people from a skill set perspective, designers design and developers write code. But, if non-functional roles aren’t delineated there’s guaranteed to be conflict.” She says clear roles deal with things like, “Who makes decisions? Who brings what perspectives? Who’s able to facilitate openly? Who will plan and track what the collaborators do?” Wodtke also acknowledges that roles are never a set-piece that can work anywhere. “Different collaborations will have different shapes,” she says, calling up classic comic book collaborations as an example. Stan Lee & Steve Ditko, early pioneers of comic book creation, approached writing and drawing together as two equals with different skills building one thing. Neil Gaiman the sci-fi and fantasy author on the other hand, will turn over a full manuscript for a graphic novel without really having thought much about or worked much with the imagery. Both approaches clearly result in quality output, but each is suited to the individual collaborators.

There are some conventional role definition frameworks can be used/adapted for collaboration success, as well as some roles that don’t typically get called out in such frameworks, but that are critical. At the end of the day, roles are a way to formally establish authority and scope in a way that the whole team can share in. The importance of roles lies not only in their ability to channel power dynamics. Defining clear roles also helps create growth opportunities for more junior team members, or those who are looking to grow their skills. One way to help people skill up in a role they don’t tend toward naturally is to try it out briefly. This can be especially useful if there is a group of 3 or 4 people who are co-creating something and there is a natural set of alliances that emerge. By “forcing” people to shift their role, they will also shift their perspective and perhaps be able to get beyond their default position to get to a breakthrough.

Next we’ll look at how roles help channel people’s energy and clarify boundaries and responsibilities within the team to keep a diverse set of people focused and productive. Roles should be defined for those who are fully focused on the effort as well as for stakeholders and experts that advise the team. Roles aren’t like job functions that are stable; over time, you may find that roles can shift to give people different experiences.

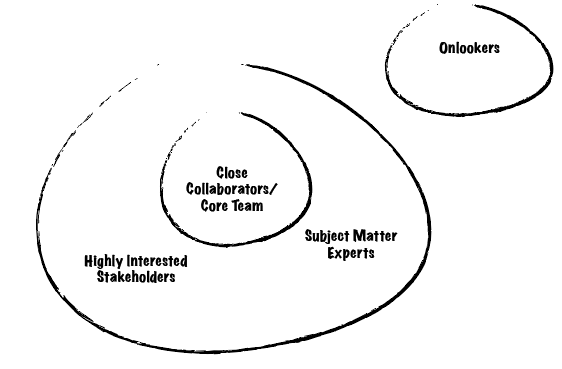

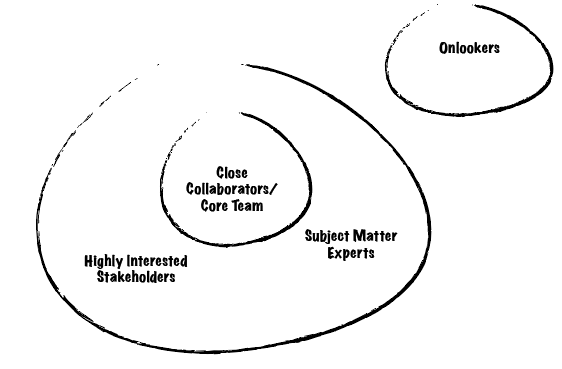

When you are enlisting many people, as we looked at in Chapter 1, you need to acknowledge that there is a time and place for many people to participate, but there are also times when a smaller, core group of people need to dive into solutions. It pays to be clear about different levels of contribution as shown below. (Figure 2.1)

At the center, you have the inner circle of Close Collaborators who are doing the bulk of the heavy lifting, where a few people who are very close to the problem explore ideas and develop them to be tested. These are the people who are focused on the problem fully, and who have the diverse skills needed to create solutions for it. The roles here need to support a balance between exploring divergent ideas and converging and testing ideas in a way that is traceable and transparent.

Surrounding the close collaborators are Highly Interested Stakeholders who are collaborators in the effort, even if they aren’t directly responsible for delivering the solution. These people are affected by the outcome of the collaboration but aren’t actively participating on a daily basis. These might be those who manage a function that is critical, or who manage related efforts that have dependencies or related priorities. The biggest challenge that arises here is when these stakeholders are not clear on how they are to participate, especially senior leaders accustomed to having casual remarks about ideas or solutions taken are clear directives about where to go next. Establishing the lines of authority around decisions and how feedback is given is critical.

On the outside are Onlookers who are watching your collaboration even if they haven’t been invited to participate. This may be because they are inspired by the challenge, or fearful for being left out, or simply bored and looking for a distraction. While it can be tempting to ignore these folks, it’s useful to make sure you are communicating to this audience so they don’t become active detractors.

It’s important to point out that collaborators aren’t necessarily those within your direct organization. You are likely to have to include clients, or outside partners with specific expertise. There isn’t necessarily a big difference in how people work together from different companies, but it is worth noting that goals may be generally aligned but still not 100% the same. For example, a vendor you rely on for key technology needs a seat at the table, but success for them may be selling you more product over your end-product being successful.

From Agile, to Sprints, to Design Thinking, there’s a great deal out there about how to get close collaborators working well. I have found that, when it comes to making use of roles, the world of “pairing” holds a lot of value. Pair Programming is a movement that started with software developers, as a way to increase the quality of code and as a way to move quickly through a variety of approaches to a problem. Pair Design takes a similar approach to the architecture and overall design of a product or service. Pairing can be practiced by Designers, Developers, and Product Managers. In our book for O’Reilly, Pair Design, Chris Noessel and I look at how pairing works and show some variations of how it is practiced in detail. For our purposes, it’s less about people working in literal pairs than giving small groups of 2-5 collaborators structure for their participation in an intimate group. Below are roles that can help your team share responsibilities for working together as a core team.

The Navigator

The Driver(s)

The Historian

Critics

The Facilitator

Make like others?

Add key takeaways to each chapter

If the Navigator within a collaboration is focusing on the bigger picture for the group to explore, the Driver is the person (or people) working through possible solutions to the challenges within that space. They will be holding the pen at the whiteboard, or will be using the keyboard to write code or draw ideas quickly. Drivers are less concerned with tracking the flow or keeping the whole picture in mind than navigators, focusing instead on developing divergent approaches to a problem quickly, so that the pair can evaluate them.

Drivers are typically responsible for:

Technical solutions: developing ideas and creating them (in code, on whiteboard, etc.)

Expansive thinking: the team needs drivers to be able to develop multiple approaches to a solution rather than simply honing in on one. This is where having several drivers is useful.

Bringing expertise: drivers should have perspectives on the problem and solution space that is more specific

When assigning people the role of Drivers, you are looking for people who have enough technical ability to render their ideas quickly in some medium for the pair or small group to react to. Drivers should also be able to easily come up with multiple solutions to a challenge, not augur in on a single idea and argue it. Drivers should be:

Fluent in the medium: whether you are developing a new organizational model, or creating a new feature for a product, drivers should have the requisite technical skills and knowledge to create substantive artifacts.

Solution-focused: whether your driver(s) are extrovert who enjoy duking it out over ideas at the whiteboard, or more internal processors who need to work “offline” to generate ideas to critique, their job is to give options, not rehash assumptions or redraw the map.

Invested in group success: driving is not about winning. Drivers should be made to think they are the team lead or in competition to come up with the solution.

Not one work style. Note that not all drivers need to be highly verbal types who think on their feet. Drivers who are more introverted may need to develop ideas on their own, and bring them back to the group to share and critique.

It’s worth noting that at least during early stages, this circle of close collaborators may be 3 or 4, (or even 5, maybe!) people. When there are more than a handful of people who have a great deal of trust and respect, you are more likely workshopping ideas with a group that involves some stakeholders, rather than actually doing deep, close collaboration. In these cases, you should be very clear about who the Navigator is, and assign all others to be drivers. In a group of 3 or 4, you might try having people work “Alone, Together” as Jake Knapp calls it in the Google Sprint book. In this vein, rather than a pair work tightly out-loud on the problem, you would have people work for bits on developing ideas and sharing them, doing a critique led by the navigator, and then refining the ideas iteratively in the group. It is a good idea to state clearly that all Drivers in that setting are equals, even if there are technically more senior and more junior people in the role. As the master of collaboration, you can help the Driver or Drivers be successful by:

Killing Egos: model what it looks like to focus on group success; use group retrospectives to keep big egos in check and help others feel heard.

Together time/Alone time: Most successful pairing I’ve seen will have a schedule that might put people working closely together for a few hours in the morning, and then having them work independently in the afternoon. When they return the next day, they can check in about where each person got to.

Dedicated focus: like Navigators, drivers need enough time and space to take the ideas that the pair has worked through to the next level. If Drivers are people who are spread across multiple problems, you will find that they resort of “swoop and poop” behavior rather than being invested in the specific problem and pair.

Finally, when wrangling people in very close collaboration be aware that these roles can (and in some cases should be) fluid. Especially later in the process when the collaboration is about specific implementations of solutions, as opposed to a big vision, it can be useful to have people take different perspectives and switch often. Sometimes this happens naturally. When observing pair programming, I’ve seen two people working the same keyboard and mouse because each person is very familiar with the problem and each of them has skills or expertise that is specific to solving the problem. There are also pairs who fit so naturally into the roles that no swapping happens. Often if one of the collaborators is a product manager, or other generalist skill set, they will fit naturally in the role of Navigator, and won’t have the technical expertise or fluency to be a driver. If you are filling one of the roles of close collaboration, make sure you yourself are keeping to your assigned role, and check in often to make sure you haven’t lost sight of the path you are navigating.

Every good collaboration lives and dies on its ability to tell it’s story well. I’ve found that good stories don’t write themselves, and while everyone thinks they know how to tell them, they never make the time. At crunch time, it’s the artifacts and prototypes that pull our attention. Do yourself a favor and nominate someone to be the Historian for the group. This isn’t necessarily the person who tells the story, but who helps craft it. Historians keep great notes about the trajectory of the collaboration so that when it’s time to pull the plot together, you’ve got good reference material.

Historians are primarily responsible for:

Tracking the decisions, arguments and “ah-has” of the team

Taking a longer view of the work, noticing how it changs vs. getting stuck in the present moment

Knowing what’s been communicated, to whom

The Historian is a great role to give to someone who is looking to grow their skills and learn to do more than contribute technical or subject-matter expertise. Good historians will be:

Invested in people: from the team, to the users, to the key stakeholders, these are people who are curious about how people think and take in information. Researchers are often well-suited to this role.

Detail-oriented: while you don’t want this person to be a “note-taker” who just transcribes every blow-by-blow, you do need them to capture more than the final outcomes over time.

Synthesizers:

Historians may consider themselves to be in a “support” role for the team, when in fact their contribution is critical, and requires many leadership qualities. You can help Historians be successful by:

Giving them time to recap every session: it’s hard at the end of a long session together to find the energy and time to recap key moments. We love to focus on action items and next steps, instead of talking through what the key moments were.

Plotting out the story: alongside the artifacts and prototypes, help the historian write out why the outcomes matter, to whom and how they unfolded

We’ve all had the colleague who just can’t help but shut down every idea that they encounter. Whether it’s because “we already tried that” or “it’s not possible,” they’ve never met a solution they didn’t like. Their energy isn’t just annoying, it can infect the entire group by making people doubt themselves or tire them out having to debate endlessly with someone who won’t engage.

Explicitly giving someone the role of being the Critic, can turn their negativity into something productive, but it takes some doing. You must first decide when to assign this role. If you know that someone important to include is likely to be a naysayer, approach them ahead of time and tell them you specifically want them to play this position. Be sure to frame it as a critical part of the process, to harness their expertise to find weaknesses in the solution set so they can be refined.

If the resistance appears during the process of defining the objective or generating divergent options, you will have to try to reframe their participation after the fact, which can be awkward. I find it helpful to explain the overall process and timeframe of the effort, and be clear about when they will be called upon. You can give them a specific meeting, or series, with the group for them to “lead” their critiques. It’s important to remove them from the meetings where that energy won’t be welcome. I tend to say something like, “you can skip tomorrow’s session. We’re going to be doing more brainstorming which is going to drive you crazy. Why don’t you do something more important and we’ll share what we come up with afterward. We’d love to hear your thoughts in next week’s session.”

The trick is elevating their negative energy into an official part of the process. Help critics feel valued and be useful by:

Being rigorous. Give them specific guidance on how to frame their feedback. List out specific questions you are looking for them to answer about the work so they know where to focus. It also helps to be clear about where in the process the work is, and what assumptions you’ve made along the way.

Letting them air out their reservations. Don’t give into the tendency to argue with their critique. The points that are valid can be used to make solutions stronger. Points that are conjecture or strawman arguments can be ignored.

Giving them dedicated space. Ask critics to lead a specific session to tackle ideas, not while generating options. It can also be useful to ask them to write down their arguments, or comment on what others have written rather than do it all face to face.

Testing their theories. Remember that in general, the critics arguments are just as much a guess as the ideas they attack. Enlist the critic to help test ideas out and identify what evidence would be needed to know when an idea is good, bad, or impossible.

Celebrating their improvements. When critique does make ideas better, be sure to call that out. That is something the whole team should feel good about.

In addition to a Navigator, you may need a separate facilitator to guide discussions, most often when the core of close collaborators are bringing in stakeholders or subject matter experts to explore ideas and give feedback. It’s worth noting that most experts in facilitation see the core responsibility of the role to guide the process, with less focus on the content of the problem area or solution. Appoint a Facilitator to wrangle larger groups, especially if there are many different levels of seniority, authority, and expertise coming together. If you or those you work with will not be seen as impartial, and the challenge is highly charged or political, consider hiring a facilitator, or finding someone in the org who is seen as impartial and who can be a trusted facilitator.

Facilitators are primarily responsible for:

Structuring and managing time

Keeping focus on the material and appropriate topics

Keep discussions and decisions visible, working with navigator

Helping the group make “Lasting agreements”, move through the diverge/converge process as a group

When choosing a facilitator, look for someone who can stay above the fray, and keep the big picture in mind. You, as someone who is curious enough about successful collaboration are a likely candidate for this role. Facilitators have three key traits:

Above the fray: A facilitator is a guide to help people move through a process together, not the seat of wisdom and knowledge. That means a facilitator isn’t there to give opinions, but to draw out opinions and ideas of the group members.

Invested in the team: Facilitators focus on how people participate in the process of learning or planning, not just on what gets achieved

Open-minded: A facilitator is neutral and never takes sides

If you feel like you aren’t this person, or maybe don’t feel like you have enough political clout to pull it off, being the Navigator is another role to consider where you can hone your leadership skills, not just technical skills.

In many organizations, a model known as RACI is used to organize decision-making. To summarize it briefly, RACI is an acronym that encapsulates each of the key roles:

R = Responsible: The person responsible for delivering the desired outcome

A = Accountable: The person accountable for the outcomes and any associated risks

C = Consulted: often the meat of the team, those consulted include the functional experts, subject-matter experts, and even actual users

I = Informed: Those who should know about key decisions, who need to understand what has occured but who aren’t directly responsible for the effort

Responsible: the person who fully understands the challenge, the desired outcome and who is accountable for the success of the effort. Without this person being adequately incented to make “winning” decisions, without them being accountable, they serve more of a facilitative role. As the person who arguably is closest to the problem and the possibilities, they benefit from having the risk/reward of making the right decisions, or more likely, learning from decisions to get to the right decision.

Accountable or the Advisor: the person (or people) who are positioned to understand the risk implications of different decisions, who have veto authority, and who are aware of how outcomes affect the company. I have found that while the CEO might be ultimately accountable for a decision, giving them the explicit accountability means they rarely have enough information to question the ideas of the Driver. To this end, making them as Advisor who can veto or challenge ideas sets them up as a contractive foil to the D, and less likely to blindly accept their recommendations or argue for argument’s sake.

Contributors: These are those who are responsible for actually developing solutions to challenges and seeing them implemented. These will certainly include the close collaborators we looked at previously. It may also include those who are responsible for aspects of the solution that are dependent or highly-related but adjacent to the core solution such as DevOps Engineers or members of the legal team. Often the group of contributors, are actually those who inhabit the creation-oriented roles described above such as drivers or passengers or critics.

Informed: This group tends to be overlooked and dismissed in the (mistaken) assumption that they are less important that those above. However, as we will see, and you likely have experienced, if those who should be informed don’t feel adequately prepared, they are likely to become bottlenecks or adversaries who need to be won over after the fact.

You may have seen or read about this model as DACI, instead of RACI. In a DACI model, the R becomes a D for the Decider or Driver of the effort. Given the previous discussion of pairing or close collaboration, I will use the RACI “Responsible” to avoid confusion about this role. In my experience, and in the experience of those I spoke with, the differences are negligible between the two sets of acronyms. The key is to assign different focuses between those who have a great deal of accountability for a solution, but little hands-on time or experience and those who work a problem directly. Having seen this model employed in many different settings, I have seen it provide healthy clarity around decisions, and helps teams work in smaller groups with less friction with those who are Interested and perhaps want to be more than Informed.

While RACI roles tend to be obvious to assign based on skills and hierarchy, roles for close collaborators may be less clear. Roles are simply a tool to get a wide variety of people with different perspectives to work together with less friction. To that end, you need to get to know folks in order to figure out where to put them.

Things to consider when assigning roles and putting the group together:

Expertise and skills. You need a variety, but also need to cover what’s required to get the job done. Even if you can’t get full participation from someone with critical knowledge or abilities, see what time and attention you can get rather than trying to make do.

Ability to think on their feet vs “offline” and on their own. If the entire group loves to debate verbally and intensely, you may find that ideas are being chosen based on that public performance, without careful analysis. See who might be able to work offline or in writing to bring a different lens.

Language proficiency. If not everyone shares the same native language, see if you can get the group to use simple words and syntax, avoiding acronyms or abbreviations that won’t be well-known.

By being thoughtful about how you place people in a team, and being prepared ahead of time, you can channel people’s energy more productively.

Assigning roles and getting people to stay in them is key to keeping people aligned and coordinated. Below are ideas for how to handle issues within the core team and with stakeholders.

While there’s nothing inherent in any of the roles I’ve described above that specifically calls out one as more important than another, people may still think that way. Because our corporate culture tends to celebrate individuals who lead by speaking frequently and making decisions, it’s natural to assume a hierarchy that doesn’t need to be there. After all, no one can make a well-informed decision about something complex without the hard work and expertise of contributors who put in blood, sweat, and tears to lay out the options. While according to the org chart there may be actual hierarchy in a group, the point of roles is often to establish different, more inclusive lines of authority that make room for those “at the bottom.” When people start assuming that some people are more important than others in a collaboration, it’s not just a morale killer, it’s a perspective killer.

So What Can I Do?

Rotate roles. One way to make it clear that all roles are valued, as are all people in a team, it’s useful to have people swap roles from time to time. This is less applicable to the RACI roles which should stay stable among a group of people who aren’t working an issue day-to-day. But asking Navigators to be Drivers for a cycle can help people see the value of both roles. It’s also a good way to give people experience doing things they may not naturally be drawn to, or excel at. Asking someone who’s used to only generating ideas, to serve as the “big picture” person for a while, may give them some empathy for how hard that role can be. Vice versa, those who don’t think of themselves as “creative” may be surprised at their ability to open up when they freed up from charting the team’s path.

Model and celebrate being a “contributor.” When RACI roles are assigned, there’s often much more attention paid to who gets to decide things, and who gets to advise on or veto them. You can help draw energy away from these roles, by calling out key contributions that the team needs, whether it’s expertise, or key deliverables. When you yourself are a contributor, take great pride in knowing that the “real work” you are doing is what moves the needle as much as any leader. Any many good senior leaders are very willing to share the limelight, and call out the efforts of contributors, especially if you ask them to.

Just because you’ve assigned roles, doesn’t mean that they are always respected. Especially over time, people can fall into natural ruts, and let roles fall by the wayside. Or, people take on responsibilities that rightfully belong to others because they are easier, or seen to be more prestigious.

So What Can I Do?

Look for a mismatch. You may have a person who’s been put in a role that’s a bit of a stretch for them. Perhaps that was an intentional move to give them a growth opportunity, or perhaps they over-committed themselves. It may be worth revisiting roles and adjusting responsibilities temporarily, or for the longer term.

Commit to responsibilities as a group. If it feels like the person or people aren’t “staying in their lane” out of laziness or willful ignorance, it’s worth having the group periodically review different roles and commit to them explicitly. When people are made to sign up to something publicly, that gives the group the ability to hold them accountable, or give them the needed prod to hold themselves accountable.

Roles help channel people’s energy and clarify boundaries and responsibilities so it’s worth taking the time to define them and make sure they are understood. Having a set of roles for close collaborators will help them work through defining problems and generating ideas. For stakeholders and other interested parties, RACI roles provide structure to discuss and decide productively. It’s important to note that roles aren’t positions, and can and should flex over time, giving people different experiences and adjusting to where the groups focus is. In the next chapter we will look at how to help teams develop trust in each other to help them when things get tough or uncomfortable.

Collaborations include differing levels of contribution. Not everyone is focused on the problem full-time, so it’s good to discern between the core team of close collaborators and the stakeholders and subject-matter experts that support them.

Close collaborators need roles that keep them focused on their contributions when defining objectives and exploring ideas.

The Navigator roles holds down the big picture and directs the teams efforts to explore ideas and generate solutions to be tested.

The Driver(s) role focuses people on the solutions to the problem and thinking creatively.

The Historian roles keeps track of what the team has done, and what it has discovered to help tell the story later.

Critics are those who help evaluate ideas and bring in constraints to make them stronger.

The Facilitator role focuses on the process and team dynamics rather than the content of the collaboration to keep things flowing, and keep conflicts productive.

For stakeholders and subject-matter experts who might be tempted to be overly prescriptive and dictate solutions, the RACI model helps with making decisions, establishing accountability, and knowing who should be informed.

Building Effective Product Teams

Copyright © 2019 Gretchen Anderson. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492041733 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Mastering Collaboration, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-04173-3

[LSI]

Now I know what you’re thinking: Everyone? That sounds...messy. In meaningful collaborations “everyone” cannot literally mean everyone, but as a principle it’s worth realizing that the more you include people who are affected by, and invested in, the topic at hand the better your results will be. Enlisting everyone, done right, actually helps.

It’s counterintuitive, but casting a wide net and including more people, actually helps you move faster. Because, consider for a moment that everyone is already “helping” you. They just aren’t doing it in a way that is actually helpful. Group dynamics, especially in competitive corporate culture, lead people to see efforts that exclude them as potential threats or a drain on resources that feel tight. At first, the people that you have not engaged (for whatever reason) might stand off to the side, neither helping or hurting your efforts. But it doesn’t take much for those who’ve been made to feel excluded to stake out a position on the opposite bank, and work against what you are trying to create. Often we assume anyone not working with us are neutral parties, but if those parties think they should be involved, they won’t stay neutral. Often in a rush to just “get to it” we leapfrog over interested parties, only to find that we must spend large amounts of time and energy trying to get their buy-in later. Their participation often takes place after the fact, as combative reviews of “finished” work, or worse, competitive efforts spring up and muddy the waters.

This isn’t necessarily because these people don’t believe in what you are doing. Rather, their reaction is a normal response to having a perspective that isn’t being heard. When we have a real interest in an effort, we can’t help but want to contribute, and if we aren’t given a chance, it can bring up an emotional response that is hard to corral productively. By engaging “everyone” in approaching a problem, you increase their commitment to the end-product and you reduce the drag on momentum.

Including “everyone” doesn’t mean every person is always fully involved, it means widening the funnel of inputs to the process, enlisting varied perspectives to generate solutions, and getting a larger set of people to vett ideas to find their faults and make our case stronger. Everyone can help if you can help make room for different perspectives and ways of engaging. Some people may be dedicating their full attention to the problem, pushing solutions forward, others may be advising or providing feedback on work. The purpose of including everyone is to get a sufficiently diverse set of perspectives on a problem to mitigate risks and drive innovative solutions.

This chapter will show how being more inclusive makes teams stronger by widening their perspective and making them more invested in the team’s success. Managing groups that are very different can present some challenges and create conflict. You can take steps to help teams work through their differences, at least enough to make working together less painful.

A recent “innovation” from Doritos stands as a great reminder of how limiting the variety of orientations to a problem can have ridiculous results. The maker of tasty chips completed some customer research, and found a surprising problem. Women reported not feeling comfortable eating Doritos in public, saying that crunching loudly and licking the delicious chemical flavor powder from dainty fingertips just didn’t seem ladylike to many. So the brand announced a plan to address this problem by creating Lady Doritos – a less crunchy, less finger-lickin’ good version of the product. They had successfully dealt with every every issue identified. Or, had they?

Now, mind you, the problem wasn’t that women weren’t buying the chips, but that they had an aversion to eating them publicly. Both the analysis of the findings, and the proposed solution stink of a team that lacks diversity. And I don’t mean women. I suspect that those involved were all “product” people whose only hammer is a new product type, and every nail a gap in the product line. Thankfully, the Internet shame that surrounded this moment kept this idea from moving forward, but Doritos could have avoided the PR gaffe if they’d included people not responsible for product development. Because the issue is a messaging opportunity, not a product-market fit problem. A simple ad campaign showing women gustily enjoying chips in meetings, at the park, on the bus, all while smiling and laughing would have gone a long way, and probably requires a lot less investment.

Blair Reeves, head of product management at SAS and author of Building Products for the Enterprise: Product Management in Enterprise Software, says sometimes, the blind spot comes in defining the very problem itself. Prior to getting into product management, Reeves worked in international development in Cameroon. He recalls how projects to improve infrastructure among communities was often without partnership from the people. People were used to having solutions provided that may not be used or sustained once finished because they weren’t seen as something that they had ownership of. When he began asking communities about their priorities, he found that they were different than had been assumed. AIDS and HIV education weren’t as big issue for them as his organization assumed; instead the people wanted help with combating malaria and building latrines – issues that were more disruptive day-to-day.

Asking a diverse group of those who are closer to the problem is one way to spot potential missteps and avoid them. A group that’s too homogenous may miss incorrect assumptions or apply too narrow a lens to finding solutions. You should also make time to be sure that the team understands, and seeks out the right skills sets, rather than assuming they are present or trying to “make do” blindly.

[sidebar 1.1 Balanced Tam Pie]

It turns out that including those who are affected by the outcomes of the work is also a boon to morale. When Reeves not only discovered the community’s real priorities, he also found that when he started asking people about the problem, that they were easier to engage in the solutions. Those we work with are no different. When you can invite more people into a thoughtful consideration of a problem, or enlist their help testing solutions they become more active and interested. It seems obvious that when people are only shown finished work and informed of its existence they care less about it – unless of course they actively hate it. And yet, sharing finished work that can’t be changed much is standard for many office cultures.

Companies know that having more engaged employees is beneficial, it’s why they spend so much time and money measuring engagement. Marc Benioff of Salesforce found his organization faced with a challenge of employee engagement at senior levels of his leadership, something that corporations pay a great deal of attention to. Higher engagement can multiply productivity and quality so much that substantial amounts of time and money is spent monitoring and supporting people’s experience at work. Benioff wanted to nip his engagement problem in the bud, so he took pains to create a virtual space to understand what fueled the issue and define the problem and address it. “In the end the dialogue lasted for weeks beyond the actual meeting. More important, by fostering a discussion across the entire organization, [he] has been able to better align the whole workforce around its mission. The event served as a catalyst for the creation of a more open and empowered culture at the company.” Clearly senior leaders at Salesforce are busy people whose typical focus is on the products and services they create, but without spending time to come together widely as a group and establish shared understanding and priorities their day-to-day efforts would have been affected.

Collaboration is an approach to problem solving, but it’s just as valuable as a cultural force that helps employees engage with purpose and meaning in their jobs, not just productivity.

So, maybe enlisting “everyone” has some advantages, but employing this principle can also bring up issues around diversity and inclusion for the group, and as a master of collaboration, it is important that you stay aware of dynamics that can reduce the benefits.

In studying cultural differences, there’s a force known as the Power-Distance Index, first identified by Geert Hofstede, which measures the degree to which a group values hierarchy and ascribes power to leaders. A country like the US has relatively low Power Distance because we value flatter organization and independence over bowing to authority. Japan, on the other hand, rates very high, as the culture demands a great deal of respect for elders and authority.

Malcolm Gladwell in his book, Outliers, tells the story of Korean Air’s “cockpit culture” during the late 90s when the airline was experiencing more plane crashes than any other airline. Analysis showed that the cultural norm of giving into superiors and avoiding challenging them meant that junior pilots who spotted problems failed to raise them, In Forbes, Gladwell said, “What they were struggling with was a cultural legacy, that Korean culture is hierarchical. You are obliged to be deferential toward your elders and superiors in a way that would be unimaginable in the U.S.

But Boeing and Airbus design modern, complex airplanes to be flown by two equals. That works beautifully in low-power-distance cultures [like the U.S., where hierarchies aren’t as relevant]. But in cultures that have high power distance, it’s very difficult.”

When the airline made some adjustments, their problem went away. They flattened out the power-distance index by reinforcing the value of junior aviators, and, “a small miracle happened,” Gladwell writes. “Korean Air turned itself around. Today, the airline is a member in good standing of the prestigious SkyTeam alliance. Its safety record since 1999 is spotless. In 2006, Korean Air was given the Phoenix Award by Air Transport World in recognition of its transformation. Aviation experts will tell you that Korean Air is now as safe as any airline in the world.”

How we react to power isn’t the only cultural difference you’re likely to run into. If you’re beginning to see how widening the circle of collaborators and making sure they are active, respected participants, you might be wondering how to define the right level of everyone for your teams. Getting diversity means including those with a variety of:

Experiences in industry and skills

Cultural backgrounds

Introversion and extroversion

Working styles

Primary languages

Ownership, from end-users to senior leaders and everyone in-between

Helping teams deal with cultural differences requires being open to talking about differences, creating norms that bridge gaps, and having productive conflict. When people can acknowledge to themselves and others where their perspective is coming from, it makes it easier for the group to not reject it because it’s an outlier. Discussion about how the group will handle certain differences is also a healthy thing to promote. Creating explicit norms about everything from group vs. individual working time to how decisions get made gives the group common ground. It’s important to model respecting team norms, and hold each other accountable when they aren’t respected.

[Sidebars 1.2 and 1.3]

At some point in your journey to master collaboration, you will have a realization - people are a problem. Working with power structures can be challenging, especially if you don’t happen to have a lot of authority in the system. And people are irrational and messy, which is why organizations create structures in the first place, to help guide our decisions and establish ways to control and command. Cyd Harrell knows all about these kinds of structures as someone who has made a big push in the last few years to bring innovation and inclusivity to the US Government. As a leader at 18F, the digital services arm of the government, Harrell has worked with huge governmental agencies, elected officials, and political appointees, and she’s seen first-hand the challenges of bringing a collaborative approach to command and control cultures.

“Some kinds of hierarchy are not conducive to good collaboration,” she says, “but you have to find a way through anyway. That culture exists for a reason, and many of your stakeholders have a great deal invested in it.” It’s important to note that not all organizations are chasing less hierarchy and flatter structures. Civil servants and government agencies typically have a much longer tenure than you find in Silicon Valley, and many people work hard for years to attain a level of authority and power that they aren’t eager to shove aside in the interests of being “transparent” and non-hierarchical. These organizations have succeeded in large-scale often high-risk situations because they employ what Harrell calls a “submit and review” approach where ideas are taken to a final state where a gatekeeper has the power to approve or reject the work in a single blow. In that model, more senior people are seen as experts whose point of view is critical to be aligned with. Conversely, those who are elected or appointed, might serve short tenures, with a great deal of authority, and priorities and perspectives change once that person has been replaced or voted out of office. Both of these forces tend to make collaboration hard, or nearly impossible.