Chapter 14. Migrating to Continuous Delivery

At this point in the book, you have learned many of the technical principles and practices associated with continuous delivery. In this chapter, you will learn about the challenges with migrating your organization and team to this way of working. You will also learn current good practices and approaches to make this easier.

Continuous Delivery Capabilities

If you have read the book chapter to chapter, you will have read several times about the continuous delivery capabilities that Nicole Forsgren, Gene Humble, and Gene Kim have identified in their book, Accelerate. Through their work with the State of DevOps Reports and by running the DevOps Enterprise conference series they have had a unique opportunity to identify what makes a high-performing organization. They have also developed insight into which approaches work and which don’t, and developed scientifically validated models on best practices.

One of the key findings of their research is the uncovering of 24 key capabilities that drive improvement in software delivery performance in a statistically significant way. These capabilities have been classified into five categories: continuous delivery; architecture; product and process; lean manufacturing and monitoring; and cultural. You will note that continuous delivery is a category in and of itself; this is how significant the practice is for creating a high-performing organization.

Examining the continuous capabilities in more depth, you will see the following list:

-

Use version control for all production artifacts.

-

Automate your deployment process.

-

Implement continuous integration.

-

Use trunk-based development methods.

-

Implement test automation.

-

Support test data management.

-

Shift left on security.

-

Implement continuous delivery.

Forsgren, Humble, and Kim argue in their book that if you and your organization invest in these capabilities, your software delivery performance will increase. Throughout this book, you have learned the technical skills associated with these capabilities, and this is therefore a good checklist to reference when migrating a team within your organization to continuous delivery.

Implementing Continuous Delivery Can Be Challenging

So, you’ve worked your way through the book and are keen to start helping your organization move toward fully embracing continuous delivery. However, this is not as easy as it may initially appear. Maybe you have seen this when attempting to introduce new technologies or methodologies to your team in the past, or perhaps you are simply visualizing potential technical or organizational hurdles—you know, the ones that make your organizational working practices “special.” (Spoiler alert: every organization is unique, but very few are particularly “special” when it comes to continuous delivery.) Don’t be discouraged if your initial efforts appear fruitless; migrating to continuous delivery can take time.

The first question to ask, particularly if your organization consists of more than one software delivery team or product, is how do you pick which application to migrate first?

Picking Your Migration Project

The DevOps Handbook, a highly recommended read for any technical leader, contains an entire chapter dedicated to choosing which project, or more correctly, which “value stream” to start with when attempting a DevOps transformation. Whether you are looking to begin a full-scale transformation or simply to implement continuous delivery, the advice for choosing a target is very much the same. The first step in picking a migration process is to do some research on your organization. If you are a relatively small startup or medium-scale enterprise, this may be easy. If you are working in a large-scale multinational organization, this may be more challenging, and you may want to limit your research to only the geographic area in which you work.

Cataloguing the value streams, systems, and applications can provide you with an overview of which areas to tackle first. When doing your research, The DevOps Handbook authors recommend considering both brownfield and greenfield projects, as well as systems of record (resource planning and analytic systems) and systems of engagement (customer-facing applications). The advice continues by suggesting that you “start with the most sympathetic and innovative groups.” The goal is to find the teams that already believe in the need for continuous delivery (and other DevOps principles), and teams that already possess a desire and demonstrated ability to innovate and be early adopters in new technologies and techniques.

Once you have chosen your project or team to begin your continuous delivery journey, you must then take time to understand their situation in more depth.

Situational Awareness

Any large-scale change within a company or organization will take commitment of resources, time, and determination. An organization is a complex adaptive system and can appear at times to be much like a living creature itself. This is further compounded when the organization and the change involve the use of technology, as you are then dealing with a “socio-technical” system. The Cynefin framework is a conceptual framework used to help leaders and policy makers reach decisions. Developed in the early 2000s within IBM, it was described as a “sense-making device.”

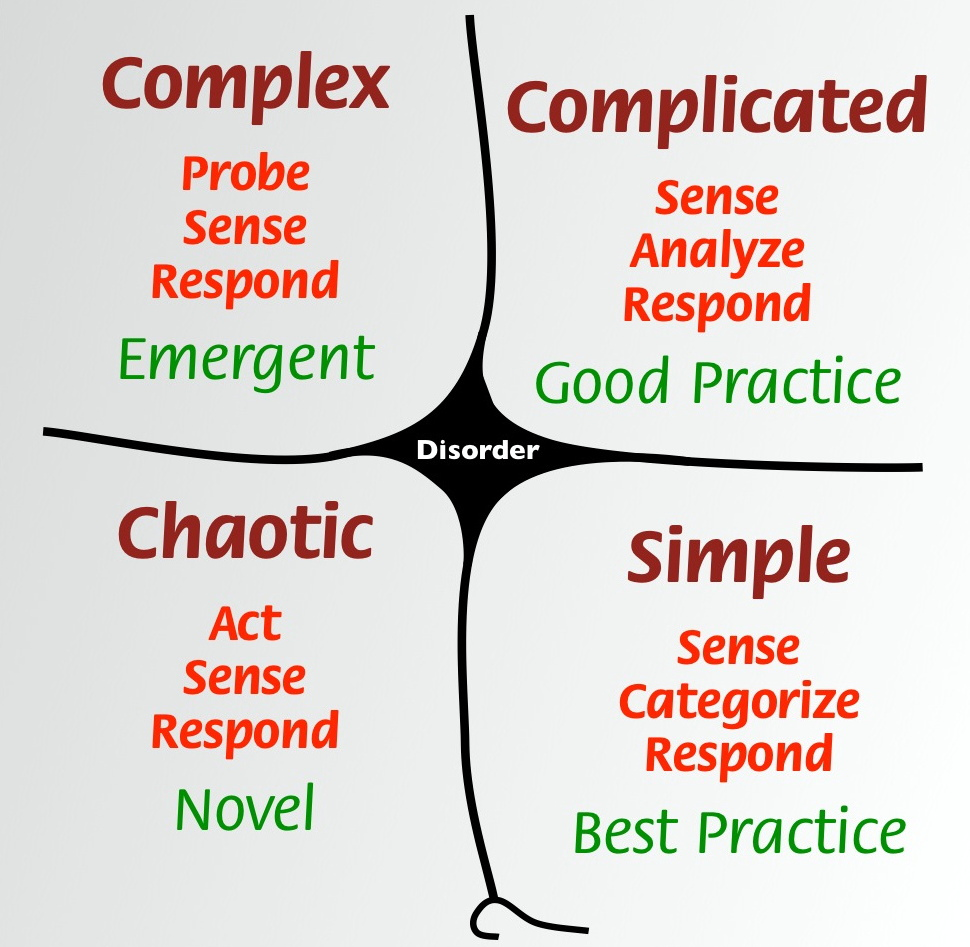

Cynefin offers five decision-making contexts or domains: simple, complicated, complex, chaotic, and disorder. The purpose of the framework is to enable leaders to indicate how they perceive situations, and to make sense of their own and other people’s behavior and decide how to act in similar situations. Figure 14-1 shows that the domains on the right, simple and complicated, are ordered: cause and effect are known or can be discovered. The domains on the left, complex and chaotic, are unordered: cause and effect can be deduced only with hindsight or not at all.

Figure 14-1. The Cynefin framework: a conceptual framework used to help leaders perceive and analyze situations, and decide how to act. (Image from Dave Snowden taken from Wikipedia)

The Cynefin Framework and Continuous Delivery

The Cynefin framework can be a useful tool when implementing continuous delivery within an organization. Although nearly all organizations are in the Complex quadrant, many of the situations involved within a journey to embracing continuous delivery fall elsewhere in the framework.

Simple

The simple domain represents the known knowns. These are rules or best practices: the situation is stable, and the relationship between cause and effect is clear. The advice is to sense–categorize–respond: establish the facts (sense), categorize, and then respond by following the rule or applying a best practice. For example, one of the first situations encountered with a continuous delivery adoption journey is the storing, access, and management of source code. Here you can do the following:

- Establish the facts

-

Application source code is stored in Git, config is stored only in a database, and infrastructure code is stored within scripts marked with version numbers.

- Categorize it

-

Review the source code storage mechanisms.

- Respond

-

The current best practice within this space is to utilize a version-control system (VCS) or distributed VCS (DVCS).

Complicated

The complicated domain consists of the known unknowns. The relationship between cause and effect requires analysis or expertise; there is a range of right answers. The framework recommends sense–analyse–respond:

- Sense and assess the facts

-

Identify the steps required to take code from a local development machine to production.

- Analyze

-

Examine and analyze each of the steps, and determine the techniques and tools required, along with the teams (and any challenges) that will need to be involved.

- Respond

-

By applying the appropriate recommended practice.

You will often encounter the complicated domain when attempting to build your first continuous delivery pipeline. The steps within such a pipeline are known, but how to implement them for your specific use cases is not. Here it is possible to work rationally toward a decision, but doing so requires refined judgment and expertise.

Complex

The complex domain represents the unknown unknowns. Cause and effect can be deduced only in retrospect, and there are no right answers. Instructive patterns can emerge if experiments are conducted that are safe to fail. Cynefin calls this process probe–sense–respond. Complexity within continuous delivery is often encountered when attempting to increase adoption in an organization.

Chaotic

In the chaotic domain, cause and effect are unclear. Events in this domain are “too confusing to wait for a knowledge-based response,” and action is the first and only way to respond appropriately. In this context, leaders act–sense–respond: act to establish order; sense where stability lies; respond to turn the chaotic into the complex. This is typically how external consultants operate when called in to implement continuous delivery pipelines or firefight operational issues.

Disorder

The dark disorder domain in the center represents situations where there is no clarity about which of the other domains apply. As noted by David Snowden and Mary Boone, by definition it is hard to see when this domain applies: “The way out of this realm is to break down the situation into constituent parts and assign each to one of the other four realms. Leaders can then make decisions and intervene in contextually appropriate ways.”

All Models Are Wrong, Some Are Useful

Whenever your adoption of continuous delivery stalls or becomes stuck, it can often be a good idea to step back from the issue, look at the wider context, and attempt to classify where your issue sits within the Cynefin framework. This can allow you to use the best approach in resolving the issue. For example, if you are dealing with a simple issue (for example, whether to use a VCS), you don’t need to conduct experiments—the widely accepted best practice suggests that this is beneficial.

However, if you are dealing with a complex problem, such as securing organizational funding to further roll out your build pipeline initiative to additional departments, then conducting experiments that are safe to fail can be highly beneficial. For example, you’d identify a team that has issues deploying software, collect baseline delivery metrics (build success, deployment throughput, etc.), and work with them on a time-boxes experiment to create a simple build pipeline to address their pain.

Bootstrapping Continuous Delivery

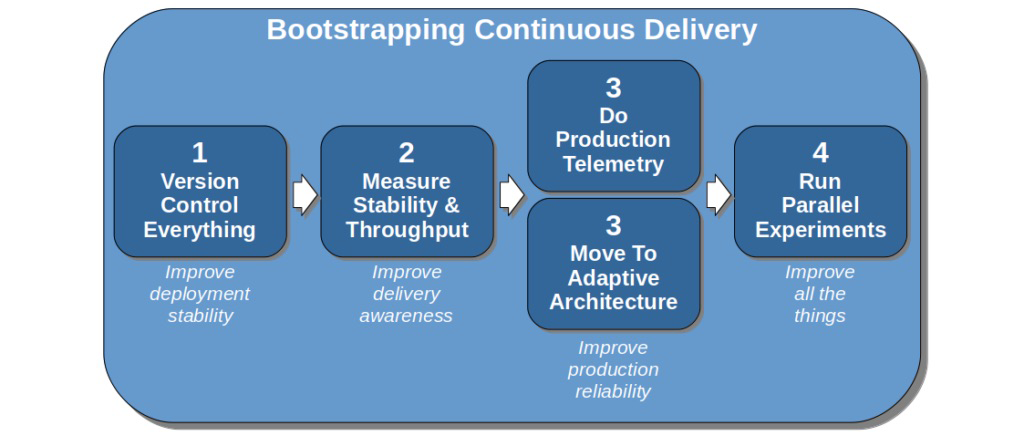

In an informative blog post by Steve Smith, “Resilience as a Continuous Delivery Enabler”, he presents a four-stage model for bootstrapping continuous delivery that complements the capabilities discussed at the start of this chapter (Figure 14-2).

The first stage to focus on is version controlling everything. This approach is echoed in the book Accelerate, as the research here shows that version controlling everything is correlated with higher performance in software delivery; “application code, system configuration, application configuration, and build and configuration scripts” should all be stored in version control. Not only can this provide increased performance, but deployment stability can also be improved.

Once this is achieved, Smith suggests that you should measure the stability and throughput of your delivery process; for example, how many deployments fail or result in near misses, and how fast can you get code committed to delivering value in production? The goal in this step is to improve delivery awareness and to provide baseline metrics that can be used for comparison later in your continuous delivery journey.

The third areas to focus on include adding production telemetry, which enables you to observe what is happening in the application both from a technical and business perspective, and moving to an adaptive (or “evolutionary”) architecture, which promotes looser coupling between components and easier modifications. The goal here is to improve production reliability.

The final stage of Smith’s model is to run parallel experiments with the goal of “improving all things.” This is where continual improvement happens over a longer time period and sets the framework for ongoing iterative improvement. (You will learn more about this in the final chapter of this book.)

Figure 14-2. Bootstrapping continuous delivery (image courtesy of Steve Smith’s blog post, “Resilience as a Continuous Delivery Enabler”)

You already learned about version controlling everything (stage 1) in Chapter 9. You also learned about increasing production telemetry, or observability, and cultivating an adaptive architecture (stage 3) in Chapters 13 and 3, respectively. In the next two sections, you will learn the fundamentals of how to measure continuous delivery (stage 2) and run parallel experiments (stage 4).

Measuring Continuous Delivery

In Accelerate, the authors state that software delivery performance can be measured effectively via four factors:

- Lead time

-

A measure of how fast work can be completed, from the ticket creation in a feature or bug tracker to the delivery into production.

- Deployment frequency

-

How often code or configuration is deployed into a production environment.

- Mean time to restore (MTTR)

-

The time taken to restore or fix a service when something goes wrong in production. This includes the time taken to identify and find the issues, as well as the time required for the implementation and deployment of the fix.

- Change fail percentage

-

A measure of how many changes that are deployed result in some form of failure.

Steve Smith builds on this work in his book, Measuring Continuous Delivery. He states that the sum of lead time and deployment frequency is the throughput of your CD process, and the sum of failure rate and failure recovery time (the MTTR) is the stability.

All four of these metrics should be established from the start of your CD migration efforts, as this will provide a baseline for comparison later. Lead time and deployment frequency can typically easily be collected from your build pipeline tooling, such as Jenkins. The failure rate and failure recovery time can be more challenging to capture unless you use an issue-tracking system (which records discovery and remediation times), and these metrics may need to be collected manually by a responsible party.

Apply Maturity Models Cautiously

Many consulting companies and DevOps tool vendors are providing maturity models that promise to capture, measure, and analyze progress with a CD implementation. There can be some value in the structure that this provides, especially if an organization is in particular chaos, but, in general, they can present challenges. Often, maturity models present a static level of technical progress that relies on the measurement of the tool’s install-base or technical proficiency, and they also assume that the steps in the model apply equally to all areas of the organization. Focusing on capabilities can account for context and variation across an organization, and drive focus on outcomes rather than obtaining a particularly qualitative measure that can be gamed.

Start Small, Experiment, Learn, Share, and Repeat

Adopting continuous delivery is a complex process, and therefore there are somewhat limited “best practices” that apply to all contexts. There are, however, many good experiments that can be run once you get to stage 4 in Steve Smith’s model:

-

If you are starting with a greenfield project, construct a basic but functional pipeline, and deploy a sample application to production as soon as possible. Dan North refers to this as creating a Dancing Skeleton. This will identify not only technical challenges such as deployments to production that must be conducted manually via a vendor portal, but also organizational issues such as the sysadmin team not giving you SFTP access to production for fear that you may damage other application configurations.

-

Identify a piece of functionality that you can have end-to-end responsibility for delivery, and improve the stability and throughput of the associated application. Ideally, this will be non-business-critical (i.e., not the checkout process within an e-commerce system), but will clearly add business value, and the requirements must be well understood. A newsletter sign-up page or a promotional microsite are ideal candidates.

-

Define one or two metrics of success that you will focus on improving with any component within your system. This could be something that is causing a particular challenge to your organization; for example, a high percentage of builds fail, or lead time for change is unacceptably high.

Once you have made progress, you must create a virtuous loop of feedback and learning across the organization:

-

Demonstrate any positive results, benefits, and key learning to as big an audience as you can find. This must include at least one leader within your organization.

-

Reflect on your approaches and technology choices. Make changes as appropriate and be sure to share this knowledge.

-

Find a slightly bigger piece of functionality—ideally, something that uses a different technology stack, or that is owned by a different team or organization unit—and repeat the experimentation process.

-

After two or three rounds of experimentation, you should have begun to identify common patterns and approaches to solve both technical and social issues within your organization. This is where you can once again elevate visibility of the program, perhaps taking the findings to the organization’s VP of engineering or CTO, and campaign for a widespread rollout of continuous delivery.

-

As soon as a senior engineering leader agrees to make the implementation of continuous delivery a priority, it’s time to switch from experimentation to rollout.

Increasing adoption throughout an organization is challenging and depends a lot on the context in which you work, but several models and approaches can help.

Increase Adoption: Leading Change

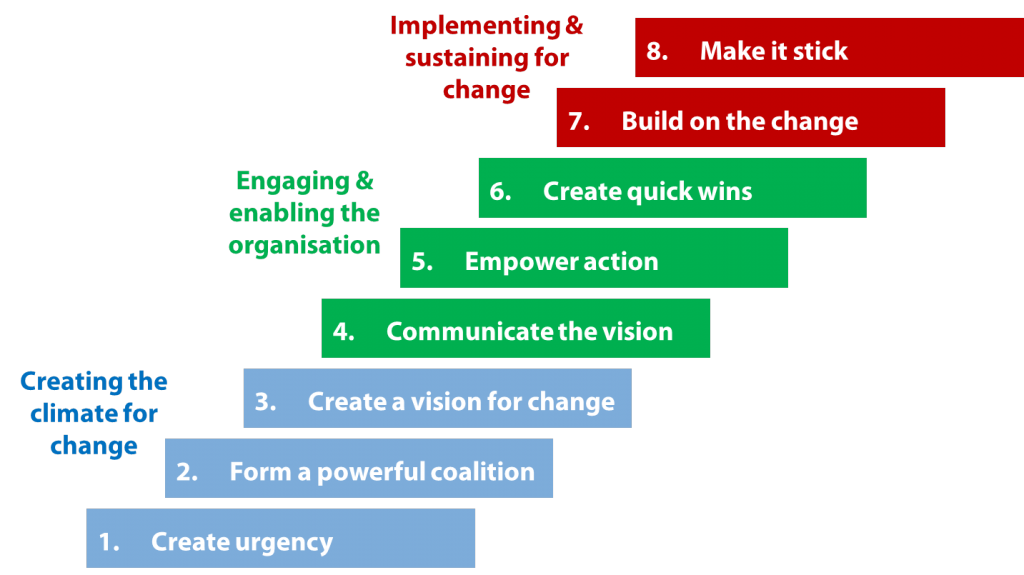

Once your experiments with continuous delivery have proved successful, the next stage is planning a wider rollout to the entire organization. Although the full process for this is beyond the scope of this book, it is worth mentioning John Kotter’s eight-step process for leading change. In his 1996 international bestseller Leading Change (Harvard Business Review Press), he defined the following steps:

-

Establishing a sense of urgency

-

Creating the guiding coalition

-

Developing a vision and strategy

-

Communicating the change vision

-

Empowering employees for broad-based action

-

Generating short-term wins

-

Consolidating gains and producing more change

-

Anchoring new approaches in the culture

These steps are relevant for any large-scale change within an organization, and implementing continuous delivery is very much a large-scale project for many companies. Figure 14-3 shows how the eight steps can be grouped into three stages, and the work you have undertaken so far falls into the first, “Creating the climate for change.” The experiments you have run should enable you to create urgency, by providing you with data you can share that shows the benefits of adopting continuous delivery (perhaps in comparison with data associated with the issues the company is currently facing).

Finding like-minded individuals and teams within the organization allows the formation of a coalition and the creation of a vision for change. The next stages for engaging and enabling the organization and implementing and sustaining for change also build upon your success and CD implementation principles and practices learned in the journey so far.

Figure 14-3. John Kotter’s eight-step process for leading change

Driving adoption of continuous delivery within an organization can be challenging—particularly when the existing delivery processes have been in place for some time, or the organization is not yet feeling enough pain to drive change (think Blockbuster versus Netflix).

Additional Guidance and Tips

An entire book could be written on how to improve adoption of continuous delivery, but a few particular areas often provide challenges: common bad practices and dealing with ugly architecture.

Bad Practices and Common Antipatterns

You have read several times within this chapter that implementing continuous delivery within an organization is a complex process, and although many good practices are context-specific, there are also bad practices that are not. It is good to be aware of these so that you can avoid them:

-

Overly ambitious choice (or scale) of functionality for continuous delivery proof-of-concept.

-

Attempting to implement continuous delivery for a completely new and innovative piece of functionality. This can be a valid choice for experimenting with CD, but it can also lead to long delays if the new functionality is not well-defined or does not have political support within the organization.

-

Introducing too much new technology into the stack—for example, going from deploying an EAR file for an application server hosted on in-house infrastructure to deploying Fat JAR applications within containers running on Kubernetes within the public cloud.

-

Simultaneously modifying the architecture in a disruptive manner and attempting to create a build pipeline for the application—for example, going from deploying the application as a single monolithic WAR file to attempting to deploy and orchestrate the application as 10 microservices.

-

Overreliance of external parties or vendors. Consultants and vendors can add a lot of value to a migration (and provide much needed expertise), but the migration process must ultimately be owned by an in-house team.

-

Simply automating current manual practices. This can be a good starting point, but care must be taken to ensure that each manual practice is valid and necessary. Automating the wrong process simply means that you can do it faster and more often, which may cause even more damage than before!

-

Not acknowledging the limitations or coupling imposed by a legacy application.

-

Not understanding that the current organizational structure is not compatible with continuous delivery (e.g., the environment is heavily politicized or Conway’s law is not being respected).

-

Not planning for migration or transformation of existing business data that is critical for the day-to-day operation of the organization.

-

Overreliance on third-party integrations (which can be solved with mocking and service virtualization).

-

Not providing access to self-service environments for development and testing.

This list is just some of the continuous delivery antipatterns that are seen in the wild. One of the most common issues deserves its own section within the chapter: the issue of “ugly” system architecture.

Ugly Architecture: To Fix, or Not to Fix

At some point within a continuous delivery implementation, the application’s architecture may be a limiting factor. Several typical examples and potential solutions are explained in this section.

Each end user/customer has separate codebase and database

It can be tempting to fork a single application codebase for individual customers, particularly if the applications share a similar core, but each customer wants customizations. This may scale when the business has only two or three customers, but soon becomes unmanageable, as a required security or critical bug patch has to be made on all the systems, and each fix may be subtly different because of the isolated evolution of each codebase.

Often an organization embracing continuous delivery with this style of application has to create as many build pipelines as there are customers, but this can also become unmanageable, particularly if the company has multiple products. A potential, but costly, solution to this issue is to attempt to consolidate all of the applications back into a single codebase that is deployed as a multitenant system, and any required custom functionality can be implemented via plugins or external modules.

Beware of the Big-Bang Fix

It can be tempting to try to fix all of your problems by throwing away (or retiring) an old application and deploying a new version as a “big bang.” This can be dangerous for many reasons: the old application evolves while the new one is being built; the business team becomes nervous that no tangible value is being delivered by the team working on the new application; engineers working on the old application become unmotivated; and the complexity of deploying the new application means that something nearly always goes wrong.

One approach to overcoming big bang rewrites that has become popular, especially within microservice migrations, is the Strangler Pattern. This pattern promotes the incremental isolation and extraction of functionality from a monolith into a series of independently deployable services.

No well-defined interface between application and external integrations

In a quest to add increased functionality to a system, engineers often integrate external applications into their applications; for example, email sending or social media integration. Often, the interface between the system and the external applications is custom and tightly coupled to the specific implementation details. This often directly affects the release cadence of your application.

When these types of systems are put into a continuous delivery pipeline, the tight integration means that typically one of two issues is seen. First, developers have created mocks or stubs to allow testing against the external application, but frequently these mocks don’t capture the true behavior of the application, or the external system constantly changes, which results in constant build failures and developers having to update the mocks. Second is that testing against the applications is conducted via external (test) sandbox implementations of the application, which are often flaky or lag behind the production implementation.

A solution to these types of issues is to introduce an anti-corruption layer (ACL)—or adapter—between the two systems. An ACL breaks the high coupling, and can facilitate the creation of a smaller, more nimble pipeline that tests the ACL adapter code against the real external (sandbox) service, and allows the company’s application to be tested against the ACL running in a virtual/stubbed mode.

Infrastructure provides a single point of integration (and coupling and failure)

Existing systems that have been deployed into production for a long time, particularly within an enterprise organization, may communicate or integrate into a centralized communication mechanism like an ESB or heavyweight MQ system. Much like the preceding example, if these systems do not provide an embedded or mock mode of operation, then it can be advantageous to implement ACLs that reduce the coupling between the application and the communication mechanism.

The application is a “framework tapestry” and contains (too) many application frameworks or middleware

Many systems that are more than 10 years old will often contain multiple application frameworks, such as EJB, Struts, and Spring, and often multiple versions of these frameworks. This soon becomes a maintenance nightmare, and the frameworks often clash at runtime, both in regards to functionality and classpaths. It can be difficult to re-create the issues seen in production within a build pipeline, especially without executing the entire application and running end-to-end tests. The classic book Working Effectively with Legacy Code (Prentice Hall) provides several good patterns for dealing with this issue. Be aware, however, that this type of architectural modification typically requires a lot of investment, and it can be advantageous to rewrite or extract certain parts of the application if there is a business case for modifying the functionality.

Think: Incremental, Hard Problems, and Pilot Project

Any migration must incrementally demonstrate value; otherwise, it is likely to get cancelled midway through the implementation. Solving, or at least understanding, the hard problems first increases the chances of delivering value, and it also typically forces you to think globally rather than getting stuck on a local optimization problem. In addition, make sure that the pilot project you pick for a migration has a clear sponsor who has political support within the organization. There will be challenging times within the migration, and you will need someone to support you and stand up for the work being undertaken.

Summary

In this chapter, you learned about the challenges of migrating to continuous delivery. You also explored techniques that help mitigate some of these challenges:

-

The research undertaken by Forsgren, Humble, and Kim shows that 24 key capabilities drive improvement in software delivery performance in a statistically significant way. Several of these capabilities have been grouped together and classified into the category of continuous delivery.

-

The first step in picking a continuous delivery migration process is to do some research on your organization. The goal is to find the teams that already believe in the need for continuous delivery and already possess a desire and demonstrated ability to innovate and be early adopters in new technologies and techniques.

-

Sense-making models, like Cynefin, can help you understand and classify some of the challenges you will encounter.

-

Steve Smith’s model for bootstrapping continuous delivery consists of: version controlling everything; measuring stability and throughput; adding production telemetry and moving to an adaptive architecture; and running parallel experiments.

-

Continuous delivery can be measured by throughput—lead time and deployment frequency, and stability—the change fail rate and mean time to recovery.

-

When you are learning how to implement continuous delivery effectively, you want to start with small hypotheses and ideas, experiment, learn, share locally and globally, and repeat.

-

Leadership is a vital skill that you will need to cultivate when attempting to increase adoption throughout the organization.

-

It is easy to fall into certain bad practices with CD, and there are potential challenges presented by “ugly” architectures.

With a good understanding of the technical practices of continuous delivery and the techniques required to roll this out across your team and organization, you are now in the perfect place to learn more about how to drive continual improvement in the final chapter.