Chapter 9. Parallelism and Concurrency

This chapter confronts the issues of parallelization and concurrency in Java 8. Some of the concepts extend back to language additions from much earlier versions of the language (especially the java.util.concurrent package added in Java 5), but Java 8 specifically added several capabilities to the language to help you operate at a higher level of abstraction.

One hazard of parallelization and concurrency is that when you try to talk about them, someone will care a lot—very vocally—about the distinction between the two words. Let’s get that out of the way right now:

-

Concurrency is when multiple tasks can run in overlapping time periods

-

Parallelism is when multiple tasks run at literally the same time

You design for concurrency—the ability to decompose your problem into independent operations that can run simultaneously, even if they aren’t doing so at the moment. A concurrent application is composed of independently executing processes. You can then implement the concurrent tasks in parallel, which may or may not improve performance, assuming you have multiple processing units.1

Why wouldn’t parallelization help performance? There are many reasons, but parallelization in Java by default splits work into multiple sections, assigning each to the common fork-join pool, executing them, and joining the results together. All of that work introduces overhead. A lot of expected performance improvements will be decided by how well your problem maps to that algorithm. One of the recipes in this chapter gives some guidelines on how to make the decision on whether or not to parallelize.

Java 8 makes it easy to try out parallelism. There is a classic presentation by Rich Hickey (the creator of the Clojure programming language) called “Simple Made Easy.”2 One of the basic concepts in his talk is that the words simple and easy imply different concepts. In short, something that is simple is conceptually clear, while something that is easy might be elementary to do but might hide massive complexity under the hood. For example, some sorting algorithms are simple and some are not, but calling the sorted method on a Stream is always easy.3

Parallel and concurrent processing is a complex topic, and difficult to get right. From the beginning, Java included low-level mechanisms to support multithreaded access, with methods like wait, notify, and notifyAll in Object, as well as the synchronized keyword. Getting concurrency right with such primitives is extremely difficult, so later the language added the java.util.concurrent package, which allowed developers to work with concurrency at a higher level of abstraction using classes like ExecutorService, ReentrantLock, and BlockingQueue. Still, managing concurrency is hard, especially in the presence of the dreaded “shared mutable state” monster.

With Java 8, asking for parallel streams is easy because it involves a single method call. That’s unquestionably easy. The problem is, improving performance is hardly simple. All the problems from before are still there; they’re just hidden under the surface.

The recipes in this section are not a complete discussion of concurrency and parallelization. Those topics can and do span entire books.4 Here the goal is to show you what the available mechanisms are and how they are intended to be used. You can then apply the concepts to your code and make your own measurements and decisions.

9.1 Converting from Sequential to Parallel Streams

Solution

Use the stream or parallelStream methods on Collection, or the sequential or parallel methods on Stream.

Discussion

By default, when you create a stream in Java the result is sequential. In BaseStream (the superclass of the Stream interface), you can use the method isParallel to determine whether the stream is operating sequentially or in parallel.

Example 9-1 shows how all the standard mechanisms used to create streams are sequential by default.

Example 9-1. Creating sequential streams (parts of a JUnit test)

@TestpublicvoidsequentialStreamOf()throwsException{assertFalse(Stream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).isParallel());}@TestpublicvoidsequentialIterateStream()throwsException{assertFalse(Stream.iterate(1,n->n+1).isParallel());}@TestpublicvoidsequentialGenerateStream()throwsException{assertFalse(Stream.generate(Math::random).isParallel());}@TestpublicvoidsequentialCollectionStream()throwsException{List<Integer>numbers=Arrays.asList(3,1,4,1,5,9);assertFalse(numbers.stream().isParallel());}

If the source was a collection, you can use the parallelStream method to yield a (possibly) parallel stream, as in Example 9-2.

Example 9-2. Using the parallelStream method

@TestpublicvoidparallelStreamMethodOnCollection()throwsException{List<Integer>numbers=Arrays.asList(3,1,4,1,5,9);assertTrue(numbers.parallelStream().isParallel());}

The reason for the “possibly” qualification is that it is allowable for this method to return a sequential stream, but by default the stream will be parallel. The Javadocs imply that the sequential case will only occur if you create your own spliterator, which is pretty unusual.5

The other way to create a parallel stream is to use the method parallel on an existing stream, as in Example 9-3.

Example 9-3. Using the parallel method on a stream

@TestpublicvoidparallelMethodOnStream()throwsException{assertTrue(Stream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).parallel().isParallel());}

Interestingly enough, there is also a sequential method, which returns a sequential stream, as in Example 9-4.

Example 9-4. Converting a parallel stream to sequential

@TestpublicvoidparallelStreamThenSequential()throwsException{List<Integer>numbers=Arrays.asList(3,1,4,1,5,9);assertFalse(numbers.parallelStream().sequential().isParallel());}

Be careful, though. There’s a trap here. Say you plan a pipeline where part of the processing can reasonably be done in parallel, but other parts should be done sequentially. You might be tempted to try the code in Example 9-5.

Example 9-5. Switching from parallel to sequential (NOT WHAT YOU MIGHT EXPECT)

List<Integer>numbers=Arrays.asList(3,1,4,1,5,9);List<Integer>nums=numbers.parallelStream().map(n->n*2).peek(n->System.out.printf("%s processing %d%n",Thread.currentThread().getName(),n)).sequential().sorted().collect(Collectors.toList());

The idea here is that you want to double all the numbers, and then sort them. Since the doubling function is stateless and associative, there’s no reason not to do it parallel. Sorting, however, is inherently sequential.6

The peek method is used to show the name of the thread doing the processing, and in the example peek is invoked after the call to parallelStream but before the call to sequential. The output is:

main processing 6 main processing 2 main processing 8 main processing 2 main processing 10 main processing 18

The main thread did all the processing. In other words, the stream is sequential, despite the call to parallelStream. Why is that? Remember that with streams, no processing is done until the terminal expression is reached, so it’s at that moment that the state of the stream is evaluated. Since the last parallel or sequential call before the collect method was to sequential, the stream is sequential and the elements are processed accordingly.

Warning

When executing, a stream can be either parallel or sequential. The parallel or sequential methods effectively set or unset a boolean, which is checked when the terminal expression is reached.

If you really have your heart set on processing part of a stream in parallel and part sequentially, use two separate streams. It’s an awkward solution, but there aren’t any better alternatives.

9.2 When Parallel Helps

Solution

Use parallel streams under the right conditions.

Discussion

The stream API was designed to make it easy to switch from sequential to parallel streams, but that may or may not help your performance. Keep in mind that moving to parallel streams is an optimization. Make sure you have working code first. Then try to decide whether or not using parallel streams is worth it. Those decisions are best made with actual data.

By default, Java 8 parallel streams use a common fork-join pool to distribute the work. The size of that pool is equal to the number of processors, which you can determine via Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors().7 Managing the fork-join pool requires overhead, both in dividing the work into individual segments and in combining the individual results back into a final answer.

For the additional overhead to be worthwhile, you need:

-

A large amount of data, or

-

A time-consuming process for each element, and

-

A source of data that is easy to divide, and

-

Operations that are stateless and associative

The first two requirements are often combined. If N is the number of data elements and Q is the amount of computational time required for each element, then in general you need N * Q to exceed some threshold.8 The next requirement means that you need to have a data structure that is easy to divide into segments, like an array. Finally, doing anything stateful or where order matters is clearly going to cause problems when going parallel.

Here is an example that is about the simplest demonstration of a computation where parallel streams help. The stream code in Example 9-6 adds a very small number of integers.

Example 9-6. Adding integers in a sequential stream

publicstaticintdoubleIt(intn){try{Thread.sleep(100);}catch(InterruptedExceptionignore){}returnn*2;}// in main...Instantbefore=Instant.now();total=IntStream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).map(ParallelDemo::doubleIt).sum();Instantafter=Instant.now();Durationduration=Duration.between(start,end);System.out.println("Total of doubles = "+total);System.out.println("time = "+duration.toMillis()+" ms");

Since adding numbers is blazingly fast, going parallel isn’t likely to show much improvement unless an artificial delay is introduced. Here N is very small, so Q is inflated by introducing a 100-millisecond sleep.

By default, streams are sequential. Since the doubling of each element is delayed by 100 milliseconds and there are six elements, the overall process should take just over 0.6 seconds, and that’s what happens:

Total of doubles = 46 time = 621 ms

Now change the stream code to use a parallel stream instead. The Stream interface has a method called parallel for this purpose, shown in Example 9-7.

Example 9-7. Using a parallel stream

total=IntStream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).parallel().map(ParallelDemo::doubleIt).sum();

On a machine with eight cores, the instantiated fork-join pool will be of size eight.9 That means each element in the stream can have its own core (assuming nothing else is going on—a point to be addressed later), so all the doubling operations can happen essentially simultaneously.

The result now is:

Total of doubles = 46 time = 112 ms

Since each doubling operation is delayed by 100 milliseconds and there are enough threads for every number to be handled individually, the overall computation only took just over 100 milliseconds.

Timing using JMH

Performance measurements are notoriously difficult to get right, because they are dependent on many different issues like caching, JVM startup times, and more. The demonstration shown here is quite crude. One mechanism that can be used for more rigorous testing is the micro-benchmarking framework JMH (Java Micro-benchmark Harness, available at http://openjdk.java.net/projects/code-tools/jmh/).

JMH lets you use annotations to specify the timing mode, scope, JVM arguments, and more. Refactoring the example from this section to use JMH is shown in Example 9-8.

Example 9-8. Timing the doubling operation using JMH

importorg.openjdk.jmh.annotations.*;importjava.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;importjava.util.stream.IntStream;@BenchmarkMode(Mode.AverageTime)@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS)@State(Scope.Thread)@Fork(value=2,jvmArgs={"-Xms4G","-Xmx4G"})publicclassDoublingDemo{publicintdoubleIt(intn){try{Thread.sleep(100);}catch(InterruptedExceptionignored){}returnn*2;}@BenchmarkpublicintdoubleAndSumSequential(){returnIntStream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).map(this::doubleIt).sum();}@BenchmarkpublicintdoubleAndSumParallel(){returnIntStream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).parallel().map(this::doubleIt).sum();}}

The default settings are to run 20 iterations in two separate threads, after a series of warmup iterations. The results in a typical run are:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units DoublingDemo.doubleAndSumParallel avgt 40 103.523 ± 0.247 ms/op DoublingDemo.doubleAndSumSequential avgt 40 620.242 ± 1.656 ms/op

The values are essentially the same as the crude estimate—that is, the sequential processing averaged about 620 ms while the parallel case averaged about 103. Running in parallel on a system that can assign an individual thread to each of six numbers is about six times faster than doing each computation consecutively, as long as there are enough processors to go around.

Summing primitives

The previous example artificially inflated Q for a small N in order to show the effectiveness of using parallel streams. This section will make N large enough to draw some conclusions, and compare both parallel and sequential for both generic streams and primitive streams, as well as straight iteration.

Note

The example in this section is basic, but it is based on a similar demo in the excellent book Java 8 and 9 in Action.10

The iterative approach is shown in Example 9-9.

Example 9-9. Iteratively summing numbers in a loop

publiclongiterativeSum(){longresult=0;for(longi=1L;i<=N;i++){result+=i;}returnresult;}

Next, Example 9-10 shows both sequential and iterative approaches to summing a Stream<Long>.

Example 9-10. Summing generic streams

publiclongsequentialStreamSum(){returnStream.iterate(1L,i->i+1).limit(N).reduce(0L,Long::sum);}publiclongparallelStreamSum(){returnStream.iterate(1L,i->i+1).limit(N).parallel().reduce(0L,Long::sum);}

The parallelStreamSum method is working with the worst situation possible, in that the computation is using Stream<Long> instead of LongStream and working with a collection of data produced by the iterate method. The system does not know how to divide the resulting work easily.

By contrast, Example 9-11 both uses the LongStream class (which has a sum method) and works with rangeClosed, which Java knows how to partition.

Example 9-11. Using LongStream

publiclongsequentialLongStreamSum(){returnLongStream.rangeClosed(1,N).sum();}publiclongparallelLongStreamSum(){returnLongStream.rangeClosed(1,N).parallel().sum();}

Sample results using JMH for N = 10,000,000 elements are:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units iterativeSum avgt 40 6.441 ± 0.019 ms/op sequentialStreamSum avgt 40 90.468 ± 0.613 ms/op parallelStreamSum avgt 40 99.148 ± 3.065 ms/op sequentialLongStreamSum avgt 40 6.191 ± 0.248 ms/op parallelLongStreamSum avgt 40 6.571 ± 2.756 ms/op

See how much all the boxing and unboxing costs? The approaches that use Stream<Long> instead of LongStream are much slower, especially combined with the fact that using a fork-join pool with iterate is not easy to divide. Using LongStream with a rangeClosed method is so fast that there is very little difference between sequential and parallel performance at all.

9.3 Changing the Pool Size

Discussion

The Javadocs for the java.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool class state that you can control the construction of the common pool using three system properties:

-

java.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool.common.parallelism -

java.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool.common.threadFactory -

java.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool.common.exceptionHandler

By default, the size of the common thread pool equals the number of processors on your machine, computed from Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors(). Setting the parallelism flag to a nonnegative integer lets you specify the parallelism level.

The flag can be specified either programmatically or on the command line. For instance, Example 9-12 shows how to use System.setProperty to create the desired degree of parallelism.

Example 9-12. Specifying the common pool size programmatically

System.setProperty("java.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool.common.parallelism","20");longtotal=LongStream.rangeClosed(1,3_000_000).parallel().sum();intpoolSize=ForkJoinPool.commonPool().getPoolSize();System.out.println("Pool size: "+poolSize);

Warning

Setting the pool size to a number greater than the number of available cores is not likely to improve performance.

On the command line, you can use the -D flag as with any system property. Note that the programmatic setting overrides the command-line setting, as shown in Example 9-13:

Example 9-13. Setting the common pool size using a system parameter

$java-cpbuild/classes/mainconcurrency.CommonPoolSizePoolsize:20// ...comment out the System.setProperty("...parallelism,20") line...$java-cpbuild/classes/mainconcurrency.CommonPoolSizePoolsize:7$java-cpbuild/classes/main\-Djava.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool.common.parallelism=10\concurrency.CommonPoolSizePoolsize:10

This example was run on a machine with eight processors. The pool size by default is seven, but that doesn’t include the main thread, so there are eight active threads by default.

Using your own ForkJoinPool

The ForkJoinPool class has a constructor that takes an integer representing the degree of parallelism. You can therefore create your own pool, separate from the common pool, and submit your jobs to that pool instead.

The code in Example 9-14 uses this mechanism to create its own pool.

Example 9-14. Creating your own ForkJoinPool

ForkJoinPoolpool=newForkJoinPool(15);ForkJoinTask<Long>task=pool.submit(()->LongStream.rangeClosed(1,3_000_000).parallel().sum());try{total=task.get();}catch(InterruptedException|ExecutionExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}finally{pool.shutdown();}poolSize=pool.getPoolSize();System.out.println("Pool size: "+poolSize);

The common pool used when invoking parallel on a stream performs quite well in most circumstances. If you need to change its size, use the system property. If that still doesn’t get you what you want, try creating your own ForkJoinPool and submit the jobs to it.

In any case, be sure to collect data on the resulting performance before deciding on a long-term solution.

See Also

A related way to do parallel computations with your own pool is use CompletableFuture, as discussed in Recipe 9.5.

9.4 The Future Interface

Solution

Use a class that implements the java.util.concurrent.Future interface.

Discussion

This book is about the new features in Java 8 and 9, one of which is the very helpful class CompletableFuture. Among its other qualities, a CompletableFuture implements the Future interface, so it’s worth a brief review to see what Future can do.

The java.util.concurrent package was added to Java 5 to help developers operate at a higher level of abstraction than simple wait and notify primitives. One of the interfaces in that package is ExecutorService, which has a submit method that takes a Callable and returns a Future wrapping the desired object.

For instance, Example 9-15 contains code that submits a job to an ExecutorService, prints a string, then retrieves the value from the Future.

Example 9-15. Submitting a Callable and returning the Future

ExecutorServiceservice=Executors.newCachedThreadPool();Future<String>future=service.submit(newCallable<String>(){@OverridepublicStringcall()throwsException{Thread.sleep(100);return"Hello, World!";}});System.out.println("Processing...");getIfNotCancelled(future);

The getIfNotCancelled method is shown in Example 9-16.

Example 9-16. Retrieving a value from a Future

publicvoidgetIfNotCancelled(Future<String>future){try{if(!future.isCancelled()){System.out.println(future.get());}else{System.out.println("Cancelled");}}catch(InterruptedException|ExecutionExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}}

The method isCancelled does exactly what it sounds like. Retrieving the value inside the Future is done with the get method, which is a blocking call that returns the generic type inside it. The method shown uses a try/catch block to deal with the declared exceptions.

The output is:

Processing... Hello, World!

Since the submitted call returns the Future<String> immediately, the code prints “Processing…” right away. Then the call to get blocks until the Future completes, and then prints the result.

Of course, this is a book on Java 8, so it’s worth noting that the anonymous inner class implementation of the Callable interface can be replaced with a lambda expression, as shown in Example 9-17.

Example 9-17. Using a lambda expression and checking if the Future is done

future=service.submit(()->{Thread.sleep(10);return"Hello, World!";});System.out.println("More processing...");while(!future.isDone()){System.out.println("Waiting...");}getIfNotCancelled(future);

This time, in addition to using the lambda expression, the isDone method is invoked in a while loop to poll the Future until it is finished.

Warning

Using isDone in a loop is called busy waiting and is not generally a good idea because of the potentially millions of calls it generates. The CompletableFuture class, discussed in the rest of this chapter, provides a better way to react when a Future completes.

This time the output is:

More processing... Waiting... Waiting... Waiting... // ... lots more waiting ... Waiting... Waiting... Hello, World!

Clearly a more elegant mechanism is needed to notify the developer when the Future is completed, especially if the plan is to use the result of this Future as part of another calculation. That’s one of the issues addressed by CompletableFuture.

Finally, the Future interface has a cancel method in case you change your mind about it, as shown in Example 9-18.

Example 9-18. Cancelling the Future

future=service.submit(()->{Thread.sleep(10);return"Hello, World!";});future.cancel(true);System.out.println("Even more processing...");getIfNotCancelled(future);

This code prints:

Even more processing... Cancelled

Since CompletableFuture extends Future, all the methods covered in this recipe are available there as well.

9.5 Completing a CompletableFuture

Solution

Use the completedFuture, complete, or the completeExceptionally methods.

Discussion

The CompletableFuture class implements the Future interface. The class also implements the CompletionStage interface, whose dozens of methods open up a wide range of possible use cases.

The real benefit of CompletableFuture is that it allows you to coordinate activities without writing nested callbacks. That will be the subject of the next two recipes. Here the question is how to complete a CompletableFuture when you know the value you want to return.

Say your application needs to retrieve a product based on its ID, and that the retrieval process may be expensive because it involves some kind of remote access. The cost could be a network call to a RESTful web service, or a database call, or any other relatively time-consuming mechanism.

You therefore decide to create a cache of products locally in the form of a Map. That way, when a product is requested, the system can check the map first, and if it returns null, then undergo the more expensive operation. The code in Example 9-19 represents both local and remote ways of fetching a product.

Example 9-19. Retrieving a product

privateMap<Integer,Product>cache=newHashMap<>();privateLoggerlogger=Logger.getLogger(this.getClass().getName());privateProductgetLocal(intid){returncache.get(id);}privateProductgetRemote(intid){try{Thread.sleep(100);if(id==666){thrownewRuntimeException("Evil request");}}catch(InterruptedExceptionignored){}returnnewProduct(id,"name");}

The idea now is to create a getProduct method that takes an ID for an argument and returns a product. If you make the return type CompletableFuture<Product>, however, the method can return immediately and you can do other work while the retrieval actually happens.

To make this work, you need a way to complete a CompletableFuture. There are three methods relevant here:

booleancomplete(Tvalue)static<U>CompletableFuture<U>completedFuture(Uvalue)booleancompleteExceptionally(Throwableex)

The complete method is used when you already have a CompletableFuture and you want to give it a specific value. The completedFuture method is a factory method that creates a CompletableFuture with an already-computed value. The completeExceptionally method completes the Future with a given exception.

Using them together produces the code in Example 9-20. The code assumes that you already have a legacy mechanism for returning a product from a remote system, which you want to use to complete the Future.

Example 9-20. Completing a CompletableFuture

publicCompletableFuture<Product>getProduct(intid){try{Productproduct=getLocal(id);if(product!=null){returnCompletableFuture.completedFuture(product);}else{CompletableFuture<Product>future=newCompletableFuture<>();Productp=getRemote(id);cache.put(id,p);future.complete(p);returnfuture;}}catch(Exceptione){CompletableFuture<Product>future=newCompletableFuture<>();future.completeExceptionally(e);returnfuture;}}

The method first tries to retrieve a product from the cache. If the map returns a non-null value, then the factory method CompletableFuture.completedFuture is used to return it.

If the cache returns null, then remote access is necessary. The code simulates a synchronous approach (more about that later) that would presumably be the legacy code. A CompletableFuture is instantiated, and the complete method is used to populate it with the generated value.

Finally, if something goes horribly wrong (simulated here with an ID of 666), then a RuntimeException is thrown. The completeExceptionally method takes that exception as an argument and completes the Future with it.

The way the exception handling works is shown in the test cases in Example 9-21.

Example 9-21. Using completeExceptionally on a CompletableFuture

@Test(expected=ExecutionException.class)publicvoidtestException()throwsException{demo.getProduct(666).get();}@TestpublicvoidtestExceptionWithCause()throwsException{try{demo.getProduct(666).get();fail("Houston, we have a problem...");}catch(ExecutionExceptione){assertEquals(ExecutionException.class,e.getClass());assertEquals(RuntimeException.class,e.getCause().getClass());}}

Both of these tests pass. When completeExceptionally is called on a CompletableFuture, the get method throws an ExecutionException whose cause is the exception that triggered the problem in the first place. Here that’s a RuntimeException.

Note

The get method declares an ExecutionException, which is a checked exception. The join method is the same as get except that it throws an unchecked CompletionException if completed exceptionally, again with the underlying exception as its cause.

The part of the example code most likely to be replaced is the synchronous retrieval of the product. For that, you can use supplyAsync, one of the other static factory methods available in CompletableFuture. The complete list is given by:

staticCompletableFuture<Void>runAsync(Runnablerunnable)staticCompletableFuture<Void>runAsync(Runnablerunnable,Executorexecutor)static<U>CompletableFuture<U>supplyAsync(Supplier<U>supplier)static<U>CompletableFuture<U>supplyAsync(Supplier<U>supplier,Executorexecutor)

The runAsync methods are useful if you don’t need to return anything. The supplyAsync methods return an object using the given Supplier. The single-argument methods use the default common fork-join pool, while the two-argument overloads use the executor given as the second argument.

The asynchronous version is shown in Example 9-22.

Example 9-22. Using supplyAsync to retrieve a product

publicCompletableFuture<Product>getProductAsync(intid){try{Productproduct=getLocal(id);if(product!=null){logger.info("getLocal with id="+id);returnCompletableFuture.completedFuture(product);}else{logger.info("getRemote with id="+id);returnCompletableFuture.supplyAsync(()->{Productp=getRemote(id);cache.put(id,p);returnp;});}}catch(Exceptione){logger.info("exception thrown");CompletableFuture<Product>future=newCompletableFuture<>();future.completeExceptionally(e);returnfuture;}}

In this case, the product is retrieved in the lambda expression shown that implements Supplier<Product>. You could always extract that as a separate method and reduce the code here to a method reference.

The challenge is how to invoke another operation after the CompletableFuture has finished. Coordinating multiple CompletableFuture instances is the subject of the next recipe.

See Also

The example in this recipe is based on a similar one in a blog post by Kenneth Jørgensen.

9.6 Coordinating CompletableFutures, Part 1

Solution

Use the various instance methods in CompletableFuture that coordinate actions, like thenApply, thenCompose, thenRun, and more.

Discussion

The best part about the CompletableFuture class is that it makes it easy to chain Futures together. You can create multiple futures representing the various tasks you need to perform, and then coordinate them by having the completion of one Future trigger the execution of another.

As a trivial example, consider the following process:

-

Ask a

Supplierfor a string holding a number -

Parse the number into an integer

-

Double the number

-

Print it

The code in Example 9-23 shows how simple that can be.

Example 9-23. Coordinating tasks using a CompletableFuture

privateStringsleepThenReturnString(){try{Thread.sleep(100);}catch(InterruptedExceptionignored){}return"42";}CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(this::sleepThenReturnString).thenApply(Integer::parseInt).thenApply(x->2*x).thenAccept(System.out::println).join();System.out.println("Running...");

Because the call to join is a blocking call, the output is 84 followed by “Running…”. The supplyAsync method takes a Supplier (in this case of type String). The thenApply method takes a Function, whose input argument is the result of the previous CompletionStage. The function in the first thenApply converts the string into an integer, then the function in the second thenApply doubles the integer. Finally, the thenAccept method takes a Consumer, which it executes when the previous stage completes.

There are many different coordination methods in CompletableFuture. The complete list (other than overloads, discussed following the table) is shown in Table 9-1.

| Modifier(s) | Return type | Method name | Arguments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All of the methods shown in the table use the common ForkJoinPool of worker threads, whose size is equal to the total number of processors.

We have already discussed the runAsync and supplyAsync methods. They are factory methods that let you specify a Runnable or a Supplier and return a CompletableFuture. As the table shows, you can then chain additional methods like thenApply or thenCompose to add tasks that will start when the previous one completes.

The table omits a set of similar patterns for each method—two for each that end in the word Async: one with an Executor and one without. For example, looking at thenAccept, the variations are:

CompletableFuture<Void>thenAccept(Consumer<?superT>action)CompletableFuture<Void>thenAcceptAsync(Consumer<?superT>action)CompletableFuture<Void>thenAcceptAsync(Consumer<?superT>action,Executorexecutor)

The thenAccept method executes its Consumer argument in the same thread as the original task, while the second version submits it to the pool again. The third version supplies an Executor, which is used to run the task instead of the common fork-join pool.

Tip

Choosing whether or not to use the Async versions of the methods is a trade-off. You may get faster individual task execution with asynchronous tasks, but they also add overhead, so the overall completion speed may not improve.

If you want to use your own Executor instead of the common pool, remember that the ExecutorService implements the Executor interface. The code in Example 9-24 shows a variation using a separate pool.

Example 9-24. Running CompletableFuture tasks on a separate thread pool

ExecutorServiceservice=Executors.newFixedThreadPool(4);CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(this::sleepThenReturnString,service).thenApply(Integer::parseInt).thenApply(x->2*x).thenAccept(System.out::println).join();System.out.println("Running...");

The subsequent thenApply and thenAccept methods use the same thread as the supplyAsync method. If you use thenApplyAsync, the task will be submitted to the pool, unless you add yet another pool as an additional argument.

For those CompletableFuture instances that return a value, you can retrieve the value using either the get or join methods. Both block until the Future completes or throws an exception. The difference between the two is that get throws a (checked) ExecutionException, while join throws an (unchecked) CompletionException. This means that join is easier to use in lambda expressions.

You can also cancel a CompletableFuture using the cancel method, which takes a boolean:

booleancancel(booleanmayInterruptIfRunning)

If the Future has not already completed, this method will complete it by using a CancellationException. Any dependent Futures will also complete exceptionally with a CompletionException caused by the CancellationException. As it happens, the boolean argument does nothing.11

The code in Example 9-23 demonstrated the thenApply and thenAccept methods. thenCompose is an instance method that allows you to chain another Future to the original, with the added benefit that the result of the first is available in the second. The code in Example 9-25 is probably the world’s most complicated way of adding two numbers.

Example 9-25. Composing two Futures together

@Testpublicvoidcompose()throwsException{intx=2;inty=3;CompletableFuture<Integer>completableFuture=CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(()->x).thenCompose(n->CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(()->n+y));assertTrue(5==completableFuture.get());}

The argument to thenCompose is a function, which takes the result of the first Future and transforms it into the output of the second. If you would rather that the Futures be independent, you can use thenCombine instead, as in Example 9-26.12

Example 9-26. Combining two Futures

@Testpublicvoidcombine()throwsException{intx=2;inty=3;CompletableFuture<Integer>completableFuture=CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(()->x).thenCombine(CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(()->y),(n1,n2)->n1+n2);assertTrue(5==completableFuture.get());}

The thenCombine method takes a Future and a BiFunction as arguments, where the results of both Futures are available in the function when computing the result.

One other special method is of note. The handle method has the signature:

<U>CompletableFuture<U>handle(BiFunction<?superT,Throwable,?extendsU>fn)

The two input arguments to the BiFunction are the result of the Future if it completes normally and the thrown exception if not. Your code decides what to return. There are also handleAsyc methods that take either a BiFunction or a BiFunction and an Executor. See Example 9-27.

Example 9-27. Using the handle method

privateCompletableFuture<Integer>getIntegerCompletableFuture(Stringnum){returnCompletableFuture.supplyAsync(()->Integer.parseInt(num)).handle((val,exc)->val!=null?val:0);}@TestpublicvoidhandleWithException()throwsException{Stringnum="abc";CompletableFuture<Integer>value=getIntegerCompletableFuture(num);assertTrue(value.get()==0);}@TestpublicvoidhandleWithoutException()throwsException{Stringnum="42";CompletableFuture<Integer>value=getIntegerCompletableFuture(num);assertTrue(value.get()==42);}

The example simply parses a string, looking for an integer. If the parse is successful, the integer is returned. Otherwise a ParseException is thrown and the handle method returns zero. The two tests show that the operation works in either case.

As you can see, there are a wide variety of ways you can combine tasks, both synchronously and asynchronously, on the common pool or your own executors. The next recipe gives a larger example of how they can be used.

See Also

A more complex example is given in Recipe 9.7.

9.7 Coordinating CompletableFutures, Part 2

Problem

You want to see a larger example of coordinating CompletableFuture instances.

Solution

Access a set of web pages for each date in baseball season, each of which contains links to the games played on that day. Download the box score information for each game and transform it into a Java class. Then asynchronously save the data, compute the results for each game, find the game with the highest total score, and print the max score and the game in which it occurred.

Discussion

This recipe demonstrates a more complex example than the simple demonstrations shown in the rest of this book. Hopefully it will give you an idea of what is possible, and how you might combine CompletableFuture tasks to accomplish your own goals.

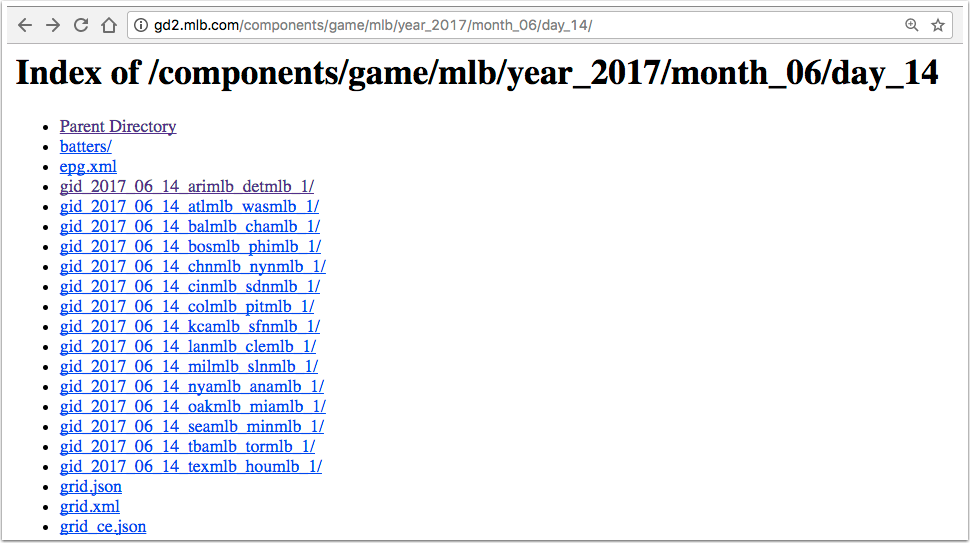

The application relies on the fact that Major League Baseball maintains a set of web pages with the box scores of each game played on a given date.13 Figure 9-1 shows the web page for all the games played on June 14, 2017.

Figure 9-1. Games played on June 14, 2017

On that page, each of the links to a game begins with the letters “gid”, followed by the year, month, and day, then by the code for the away team and the code for the home team. If you follow each link, the resulting site has a list of files, one of which is called boxscore.json.

The design of this application is to:

-

Access the site that contains the games for a range of dates.

-

Determine the game links on each page.

-

Download the boxscore.json file for each game.

-

Convert the JSON file for each game to a Java object.

-

Save the downloaded result into local files.

-

Determine the scores of each game.

-

Determine the game with the biggest total score.

-

Print the individual scores along with the maximum game and score.

Many of these tasks can be arranged to execute concurrently, and many can be run in parallel.

The complete code for this example is too large to fit in this book, but is available on the companion website. This recipe will illustrate the uses of parallel streams and completable Futures.

The first challenge is to find the game links for each date in a given range. The GamePageLinksSupplier class in Example 9-28 implements the Supplier interface to produce a list of strings representing the game links.

Example 9-28. Get the game links for a range of dates

publicclassGamePageLinksSupplierimplementsSupplier<List<String>>{privatestaticfinalStringBASE="http://gd2.mlb.com/components/game/mlb/";privateLocalDatestartDate;privateintdays;publicGamePageLinksSupplier(LocalDatestartDate,intdays){this.startDate=startDate;this.days=days;}publicList<String>getGamePageLinks(LocalDatelocalDate){// Use the JSoup library to parse the HTML web page and// extract the links that start with "gid"}@OverridepublicList<String>get(){returnStream.iterate(startDate,d->d.plusDays(1)).limit(days).map(this::getGamePageLinks).flatMap(list->list.isEmpty()?Stream.empty():list.stream()).collect(Collectors.toList());}}

The get method iterates over a range of dates by using the iterate method on Stream. It starts with the given date and adds days up to the limit.

Note

The datesUntil method added in Java 9 to LocalDate produces a Stream<LocalDate>. See Recipe 10.7 for details.

Each LocalDate becomes the argument to the getGamePageLinks method, which uses the JSoup library to parse the HTML page, find all the links that start with “gid”, and return them as strings.

The next step is to access the boxscore.json file at each game link. That is done using the BoxscoreRetriever class, which implements Function<List<String>, List<Result>> and is shown in Example 9-29.

Example 9-29. Retrieving the list of box scores from the list of game links

publicclassBoxscoreRetrieverimplementsFunction<List<String>,List<Result>>{privatestaticfinalStringBASE="http://gd2.mlb.com/components/game/mlb/";privateOkHttpClientclient=newOkHttpClient();privateGsongson=newGson();@SuppressWarnings("ConstantConditions")publicOptional<Result>gamePattern2Result(Stringpattern){// ... code omitted ...StringboxscoreUrl=BASE+dateUrl+pattern+"boxscore.json";// .. set up OkHttp to make the network call ...try{// ... get the response ...if(!response.isSuccessful()){System.out.println("Box score not found for "+boxscoreUrl);returnOptional.empty();}returnOptional.ofNullable(gson.fromJson(response.body().charStream(),Result.class));}catch(IOExceptione){e.printStackTrace();returnOptional.empty();}}@OverridepublicList<Result>apply(List<String>strings){returnstrings.parallelStream().map(this::gamePattern2Result).filter(Optional::isPresent).map(Optional::get).collect(Collectors.toList());}}

This class relies on the OkHttp library and the Gson JSON parsing library to download the box score in JSON form and convert it into an object of type Result. The class implements the Function interface, so it implements the apply method to convert the list of strings into a list of results. A box score for a given game may not exist if the game is rained out or if some other network error occurs, so the gamePattern2Result method returns an Optional<Result>, which is empty in those cases.

The apply method streams over the game links, converting each one into an Optional<Result>. Next it filters the stream, passing only the Optional instances that are not empty, and then invokes the get method on each one. Finally it collects them into a list of results.

Note

Java 9 also adds a stream method to Optional, which would simplify the filter(Optional::isPresent) followed by map(Optional::get) process. See Recipe 10.6 for details.

Once the box scores are retrieved, they can be saved locally. This can be done in the methods shown in Example 9-30.

Example 9-30. Save each box score to a file

privatevoidsaveResultList(List<Result>results){results.parallelStream().forEach(this::saveResultToFile);}publicvoidsaveResultToFile(Resultresult){// ... determine a file name based on the date and team names ...try{Filefile=newFile(dir+"/"+fileName);Files.write(file.toPath().toAbsolutePath(),gson.toJson(result).getBytes());}catch(IOExceptione){e.printStackTrace();}}

The Files.write method with its default options creates a file if it doesn’t exist or overwrites it if it does, then closes it.

Two other postprocessing methods are used. One, called getMaxScore, determines the maximum total score from a given game. The other, called getMaxGame, returns the game with the max score. Both are shown in Example 9-31.

Example 9-31. Getting the maximum total score and the game where it occurred

privateintgetTotalScore(Resultresult){// ... sum the scores of both teams ...}publicOptionalIntgetMaxScore(List<Result>results){returnresults.stream().mapToInt(this::getTotalScore).max();}publicOptional<Result>getMaxGame(List<Result>results){returnresults.stream().max(Comparator.comparingInt(this::getTotalScore));}

Now, at last, all of the preceding methods and classes can be combined with completable Futures. See Example 9-32 for the main application code.

Example 9-32. Main application code

publicvoidprintGames(LocalDatestartDate,intdays){CompletableFuture<List<Result>>future=CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(newGamePageLinksSupplier(startDate,days)).thenApply(newBoxscoreRetriever());CompletableFuture<Void>futureWrite=future.thenAcceptAsync(this::saveResultList).exceptionally(ex->{System.err.println(ex.getMessage());returnnull;});CompletableFuture<OptionalInt>futureMaxScore=future.thenApplyAsync(this::getMaxScore);CompletableFuture<Optional<Result>>futureMaxGame=future.thenApplyAsync(this::getMaxGame);CompletableFuture<String>futureMax=futureMaxScore.thenCombineAsync(futureMaxGame,(score,result)->String.format("Highest score: %d, Max Game: %s",score.orElse(0),result.orElse(null)));CompletableFuture.allOf(futureWrite,futureMax).join();future.join().forEach(System.out::println);System.out.println(futureMax.join());}

Several CompletableFuture instances are created. The first uses the GamePageLinksSupplier to retrieve all the game page links for the desired dates, then applies the BoxscoreRetriever to convert them into results. The second sets up writing each one to disk, completing exceptionally if something goes wrong. Then the post-processing steps of finding the maximum total score and the game in which it occurred are set up.14 The allOf method is used to complete all of the tasks, then the results are printed.

Note the use of thenApplyAsync, which isn’t strictly necessary, but allows for the tasks to run asynchronously.

If you run the program for May 5, 2017, for three days, you get:

GamePageParserparser=newGamePageParser();parser.printGames(LocalDate.of(2017,Month.MAY,5),3);

The output results are:

Box score not found for Los Angeles at San Diego on May 5, 2017 May 5, 2017: Arizona Diamondbacks 6, Colorado Rockies 3 May 5, 2017: Boston Red Sox 3, Minnesota Twins 4 May 5, 2017: Chicago White Sox 2, Baltimore Orioles 4 // ... more scores ... May 7, 2017: Toronto Blue Jays 2, Tampa Bay Rays 1 May 7, 2017: Washington Nationals 5, Philadelphia Phillies 6 Highest score: 23, Max Game: May 7, 2017: Boston Red Sox 17, Minnesota Twins 6

Hopefully this will give you a sense of how you can combine many features discussed throughout this book, from future tasks using CompletableFuture to functional interfaces like Supplier and Function to classes like Optional, Stream, and LocalDate, and even methods like map, filter, and flatMap, to accomplish an interesting problem.

See Also

The coordination methods for completable Futures are discussed in Recipe 9.6.

1 An excellent, (relatively) short discussion of these concepts can be found in “Concurrency Is Not Parallelism,” by Rob Pike, creator of the Go programming language. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cN_DpYBzKso for a video.

2 Video: http://www.infoq.com/presentations/Simple-Made-Easy, Transcript: http://bit.ly/hickey-simplemadeeasy

3 Another great example of simple versus easy is found in a story told about Patrick Stewart while he was playing Captain Picard in Star Trek: The Next Generation. A writer tried to describe to him all the detailed steps necessary to enter orbit around a planet. “Nonsense,” Stewart replied. “You just say, ‘Standard orbit, Ensign.’”

4 Of particular note are Java Concurrency in Practice by Brian Goetz (Addison-Wesley Professional) and Programming Concurrency on the JVM by Venkat Subramaniam (Pragmatic Bookshelf).

5 An interesting topic, to be sure, but ultimately beyond the scope of this book.

6 Think of it this way: sorting using a parallel stream would mean dividing up the range into equal parts and sorting each of them individually, then trying to combine the resulting sorted ranges. The output wouldn’t be sorted overall.

7 Technically the pool size is processors minus one, but the main thread is still used as well.

8 Frequently you’ll see this expressed as N * Q > 10,000, but nobody ever seems to put dimensions on Q, so that’s difficult to interpret.

9 The size will actually be seven, but there will be eight separate threads involved including the main thread.

10 Java 8 and 9 in Action, Urma, Fusco, and Mycroft (Manning Publishers, 2017)

11 Interestingly enough, according to the Javadocs the boolean parameter “has no effect because interrupts are not used to control processing.”

12 OK, this is probably the most complicated way of adding two numbers ever.

13 For this example, all you need to know about baseball is that two teams play, each scores runs until one team wins, and that the collection of statistics for a game is called a box score.

14 Clearly this could be done together, but it makes for a nice thenCombine example.