Chapter 6. The Optional Type

Sigh, why does everything related to Optional have to take 300 messages?

Brian Goetz, lambda-libs-spec-experts mailing list (October 23, 2013)

The Java 8 API introduced a new class called java.util.Optional<T>. While many developers assume that the goal of Optional is to remove NullPointerExceptions from your code, that’s not its real purpose. Instead, Optional is designed to communicate to the user when a returned value may legitimately be null. This situation can arise whenever a stream of values is filtered by some condition that happens to leave no elements remaining.

In the Stream API, the following methods return an Optional if no elements remain in the stream: reduce, min, max, findFirst, findAny.

An instance of Optional can be in one of two states: a reference to an instance of type T, or empty. The former case is called present, and the latter is known as empty (as opposed to null).

Warning

While Optional is a reference type, it should never be assigned a value of null. Doing so is a serious error.

This chapter looks at the idiomatic ways to use Optional. While the proper use of Optional is likely to be a lively source of discussions in your company,1 the good news is that there are standard recommendations for its proper use. Following these principles should help keep your intentions clear and maintainable.

6.1 Creating an Optional

Solution

Use Optional.of, Optional.ofNullable, or Optional.empty.

Discussion

Like many other new classes in the Java 8 API, instances of Optional are immutable. The API refers to Optional as a value-based class, meaning instances:

-

Are final and immutable (though they may contain references to mutable objects)2

-

Have no public constructors, and thus must be instantiated by factory methods

-

Have implementations of

equals,hashCode, andtoStringthat are based only on their state

The static factory methods to create an Optional are empty, of, and ofNullable, whose signatures are:

static<T>Optional<T>empty()static<T>Optional<T>of(Tvalue)static<T>Optional<T>ofNullable(Tvalue)

The empty method returns, naturally enough, an empty Optional. The of method returns an Optional that wraps the specified value or throws an exception if the argument is null. The expected way to use it is as shown in Example 6-2.

Example 6-2. Creating an Optional with “of”

publicstatic<T>Optional<T>createOptionalTheHardWay(Tvalue){returnvalue==null?Optional.empty():Optional.of(value);}

The description of the method in Example 6-2 is called “The Hard Way” not because it’s particularly difficult, but because an easier way is to use the ofNullable method, as in Example 6-3.

Example 6-3. Creating an Optional with “ofNullable”

publicstatic<T>Optional<T>createOptionalTheEasyWay(Tvalue){returnOptional.ofNullable(value);}

In fact, the implementation of ofNullable in the reference implementation of Java 8 is the line shown in createOptionalTheHardWay: check if the contained value is null, and if it is return an empty Optional, otherwise use Optional.of to wrap it.

Incidentally, the classes OptionalInt, OptionalLong, and OptionalDouble wrap primitives that can never be null, so they only have an of method:

staticOptionalIntof(intvalue)staticOptionalLongof(longvalue)staticOptionalDoubleof(doublevalue)

Instead of get, the getter methods on those classes are getAsInt, getAsLong, and getAsDouble.

See Also

Other recipes in this chapter, like Recipes 6.4 and 6.5, also create Optional values, but from provided collections. Recipe 6.3 uses the methods in this recipe to wrap provided values.

6.2 Retrieving Values from an Optional

Solution

Use the get method, but only if you’re sure a value exists inside the Optional. Otherwise use one of the variations of orElse. You can also use ifPresent if you only want to execute a Consumer when a value is present.

Discussion

If you invoke a method that returns an Optional, you can retrieve the value contained inside by invoking the get method. If the Optional is empty, however, then the get method throws a NoSuchElementException.

Consider a method that returns the first even-length string from a stream of them, as shown in Example 6-4.

Example 6-4. Retrieving the first even-length string

Optional<String>firstEven=Stream.of("five","even","length","string","values").filter(s->s.length()%2==0).findFirst();

The findFirst method returns an Optional<String>, because it’s possible that none of the strings in the stream will pass the filter. You could print the returned value by calling get on the Optional:

System.out.println(firstEven.get()) // Don't do this, even if it works

The problem is that while this will work here, you should never call get on an Optional unless you’re sure it contains a value or you risk throwing the exception, as in Example 6-5.

Example 6-5. Retrieving the first odd-length string

Optional<String>firstOdd=Stream.of("five","even","length","string","values").filter(s->s.length()%2!=0).findFirst();System.out.println(firstOdd.get());// throws NoSuchElementException

How do you get around this? You have several options. The first is to check that the Optional contains a value before retrieving it, as in Example 6-6.

Example 6-6. Retrieving the first even-length string with a protected get

Optional<String>firstEven=Stream.of("five","even","length","string","values").filter(s->s.length()%2==0).findFirst();System.out.println(first.isPresent()?first.get():"No even length strings");

While this works, you’ve only traded null checking for isPresent checking, which doesn’t feel like much of an improvement.

Fortunately, there’s a good alternative, which is to use the very convenient orElse method, as shown in Example 6-7.

Example 6-7. Using orElse

Optional<String>firstOdd=Stream.of("five","even","length","string","values").filter(s->s.length()%2!=0).findFirst();System.out.println(firstOdd.orElse("No odd length strings"));

The orElse method returns the contained value if one is present, or a supplied default otherwise. It’s therefore a convenient method to use if you have a fallback value in mind.

There are a few variations of orElse:

-

orElse(T other)returns the value if present, otherwise it returns the default value,other -

orElseGet(Supplier<? extends T> other)returns the value if present, otherwise it invokes theSupplierand returns the result -

orElseThrow(Supplier<? extends X> exceptionSupplier)returns the value if present, otherwise throws the exception created by theSupplier

The difference between orElse and orElseGet is that the former returns a string that is always created, whether the value exists in the Optional or not, while the latter uses a Supplier, which is only executed if the Optional is empty.

In this case, the value is a simple string, so the difference is pretty minimal. If, however, the argument to orElse is a complex object, orElseGet with a Supplier ensures the object is only created when needed, as in Example 6-8.

Example 6-8. Using a Supplier in orElseGet

Optional<ComplexObject>val=values.stream.findFirst()val.orElse(newComplexObject());val.orElseGet(()->newComplexObject())

Note

Using a Supplier as a method argument is an example of deferred or lazy execution. It allows you to avoid invoking the get method on the Supplier until necessary.3

The implementation of orElseGet in the library is shown in Example 6-9.

Example 6-9. Implementation of Optional.orElseGet in the JDK

publicTorElseGet(Supplier<?extendsT>other){returnvalue!=null?value:other.get();}

The orElseThrow method also takes a Supplier. From the API, the method signature is:

<X extends Throwable> T orElseThrow(Supplier<? extends X> exceptionSupplier)

Therefore, in Example 6-10, the constructor reference used as the Supplier argument isn’t executed when the Optional contains a value.

Example 6-10. Using orElseThrow as a Supplier

Optional<String>first=Stream.of("five","even","length","string","values").filter(s->s.length()%2==0).findFirst();System.out.println(first.orElseThrow(NoSuchElementException::new));

Finally, the ifPresent method allows you to provide a Consumer that is only executed when the Optional contains a value, as in Example 6-11.

Example 6-11. Using the ifPresent method

Optional<String>first=Stream.of("five","even","length","string","values").filter(s->s.length()%2==0).findFirst();first.ifPresent(val->System.out.println("Found an even-length string"));first=Stream.of("five","even","length","string","values").filter(s->s.length()%2!=0).findFirst();first.ifPresent(val->System.out.println("Found an odd-length string"));

In this case, only the message “Found an even-length string” will be printed.

See Also

Suppliers are discussed in Recipe 2.2. Constructor references are in Recipe 1.3. The findAny and findFirst methods in Stream that return an Optional are covered in Recipe 3.9.

6.3 Optional in Getters and Setters

Discussion

The Optional data type communicates to a user that the result of an operation may legitimately be null, without throwing a NullPointerException. The Optional class, however, was deliberately designed not to be serializable, so you don’t want to use it to wrap fields in a class.

Consequently, the preferred mechanism for adding Optionals in getters and setters is to wrap nullable attributes in them when returned from getter methods, but not to do the same in setters, as in Example 6-12.

Example 6-12. Using Optional in a DAO layer

publicclassDepartment{privateManagerboss;publicOptional<Manager>getBoss(){returnOptional.ofNullable(boss);}publicvoidsetBoss(Managerboss){this.boss=boss;}}

In Department, the Manager attribute boss is considered nullable.4 You might be tempted to make the attribute of type Optional<Manager>, but because Optional is not serializable, neither would be Department.

The approach here is not to require the user to wrap a value in an Optional in order to call a setter method, which is what would be necessary if the setBoss method took an Optional<Manager> as an argument. The purpose of an Optional is to indicate a value that may legitimately be null, and the client already knows whether or not the value is null, and the internal implementation here doesn’t care.

Finally, returning an Optional<Manager> in the getter method accomplishes the goal of telling the caller that the department may or may not have a boss at the moment and that’s OK.

The downside to this approach is that for years the “JavaBeans” convention defined getters and setters in parallel, based on the attribute. In fact, the definition of a property in Java (as opposed to simply an attribute) is that you have getters and setters that follow the standard pattern. The approach in this recipe violates that pattern. The getter and the setter are no longer symmetrical.

It’s (partly) for this reason that some developers say that Optional should not appear in your getters and setters at all. Instead, they treat it as an internal implementation detail that shouldn’t be exposed to the client.

The approach used here is popular among open source developers who use Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) tools like Hibernate, however. The overriding consideration there is communicating to the client that you’ve got a nullable database column backing this particular field, without forcing the client to wrap a reference in the setter as well.

That seems a reasonable compromise, but, as they say, your mileage may vary.

See Also

Recipe 6.5 uses this DAO example to convert a collection of IDs into a collection of employees. Recipe 6.1 discusses wrapping values in an Optional.

6.4 Optional flatMap Versus map

Discussion

The map and flatMap methods in Stream are discussed in Recipe 3.11. The concept of flatMap is a general one, however, and can also be applied to Optional.

The signature of the flatMap method in Optional is:

<U>Optional<U>flatMap(Function<?superT,Optional<U>>mapper)

This is similar to map from Stream, in that the Function argument is applied to each element and produces a single result, in this case of type Optional<U>. More specifically, if the argument T exists, flatMap applies the function to it and returns an Optional wrapping the contained value. If the argument is not present, the method returns an empty Optional.

As discussed in Recipe 6.3, a Data Access Object (DAO) is often written with getter methods that return Optionals (if the property can be null), but the setter methods do not wrap their arguments in Optionals. Consider a Manager class that has a nonnull string called name, and a Department class that has a nullable Manager called boss, as shown in

Example 6-13.

Example 6-13. Part of a DAO layer with Optionals

publicclassManager{privateStringname;publicManager(Stringname){this.name=name;}publicStringgetName(){returnname;}}publicclassDepartment{privateManagerboss;publicOptional<Manager>getBoss(){returnOptional.ofNullable(boss);}publicvoidsetBoss(Managerboss){this.boss=boss;}}

If the client calls the getBoss method on Department, the result is wrapped in an Optional. See Example 6-14.

Example 6-14. Returning an Optional

ManagermrSlate=newManager("Mr. Slate");Departmentd=newDepartment();d.setBoss(mrSlate);System.out.println("Boss: "+d.getBoss());Departmentd1=newDepartment();System.out.println("Boss: "+d1.getBoss());

So far, so good. If the Department has a Manager, the getter method returns it wrapped in an Optional. If not, the method returns an empty Optional.

The problem is, if you want the name of the Manager, you can’t call getName on an Optional. You either have to get the contained value out of the Optional, or use the map method (Example 6-15).

Example 6-15. Extract a name from an Optional manager

System.out.println("Name: "+d.getBoss().orElse(newManager("Unknown")).getName());System.out.println("Name: "+d1.getBoss().orElse(newManager("Unknown")).getName());System.out.println("Name: "+d.getBoss().map(Manager::getName));System.out.println("Name: "+d1.getBoss().map(Manager::getName));

The map method (discussed further in Recipe 6.5) applies the given function only if the Optional it’s called on is not empty, so that’s the simpler approach here.

Life gets more complicated if the Optionals might be chained. Say a Company might have a Department (only one, just to keep the code simple), as in Example 6-16.

Example 6-16. A company may have a department (only one, for simplicity)

publicclassCompany{privateDepartmentdepartment;publicOptional<Department>getDepartment(){returnOptional.ofNullable(department);}publicvoidsetDepartment(Departmentdepartment){this.department=department;}}

If you call getDepartment on a Company, the result is wrapped in an Optional. If you then want the manager, the solution would appear to be to use the map method as in Example 6-15. But that leads to a problem, because the result is an Optional wrapped inside an Optional (Example 6-17).

Example 6-17. An Optional wrapped inside an Optional

Companyco=newCompany();co.setDepartment(d);System.out.println("Company Dept: "+co.getDepartment());System.out.println("Company Dept Manager: "+co.getDepartment().map(Department::getBoss));

This is where flatMap on Optional comes in. Using flatMap flattens the structure, so that you only get a single Optional. See Example 6-18, which assumes the company was created as in the previous example.

Example 6-18. Using flatMap on a company

System.out.println(co.getDepartment().flatMap(Department::getBoss).map(Manager::getName));

Now wrap the company in an Optional as well, as in Example 6-19.

Example 6-19. Using flatMap on an optional company

Optional<Company>company=Optional.of(co);System.out.println(company.flatMap(Company::getDepartment).flatMap(Department::getBoss).map(Manager::getName));

Whew! As the example shows, you can even wrap the company in an Optional, then just use Optional.flatMap repeatedly to get to whatever property you want, finishing with an Optional.map operation.

See Also

Wrapping a value inside an Optional is discussed in Recipe 6.1. The flatMap method in Stream is discussed in Recipe 3.11. Using Optional in a DAO layer is in Recipe 6.3. The map method in Optional is in Recipe 6.5.

6.5 Mapping Optionals

Solution

Use the map method in Optional.

Discussion

Say you have a list of employee ID values and you want to retrieve a collection of the corresponding employee instances. If the findEmployeeById method has the signature

publicOptional<Employee>findEmployeeById(intid)

then searching for all the employees will return a collection of Optional instances, some of which may be empty. You can then filter out the empty Optionals, as shown in Example 6-20.

Example 6-20. Finding Employees by ID

publicList<Employee>findEmployeesByIds(List<Integer>ids){returnids.stream().map(this::findEmployeeById).filter(Optional::isPresent)).map(Optional::get).collect(Collectors.toList());}

The result of the first map operation is a stream of Optionals, each of which either contains an employee or is empty. To extract the contained value, the natural idea is to invoke the get method, but you’re never supposed to call get unless you’re sure a value is present. Instead use the filter method with Optional::isPresent as a predicate to remove all the empty Optionals. Then you can map the Optionals to their contained values by mapping them using Optional::get.

This example used the map method on Stream. For a different approach, there is also a map method on Optional, whose signature is:

<U>Optional<U>map(Function<?superT,?extendsU>mapper)

The map method in Optional takes a Function as an argument. If the Optional is not empty, the map method extracts the contained value, applies the function to it, and returns an Optional containing the result. Otherwise it returns an empty Optional.

The finder operation in Example 6-20 can be rewritten using this method to the version in Example 6-21.

Example 6-21. Using Optional.map

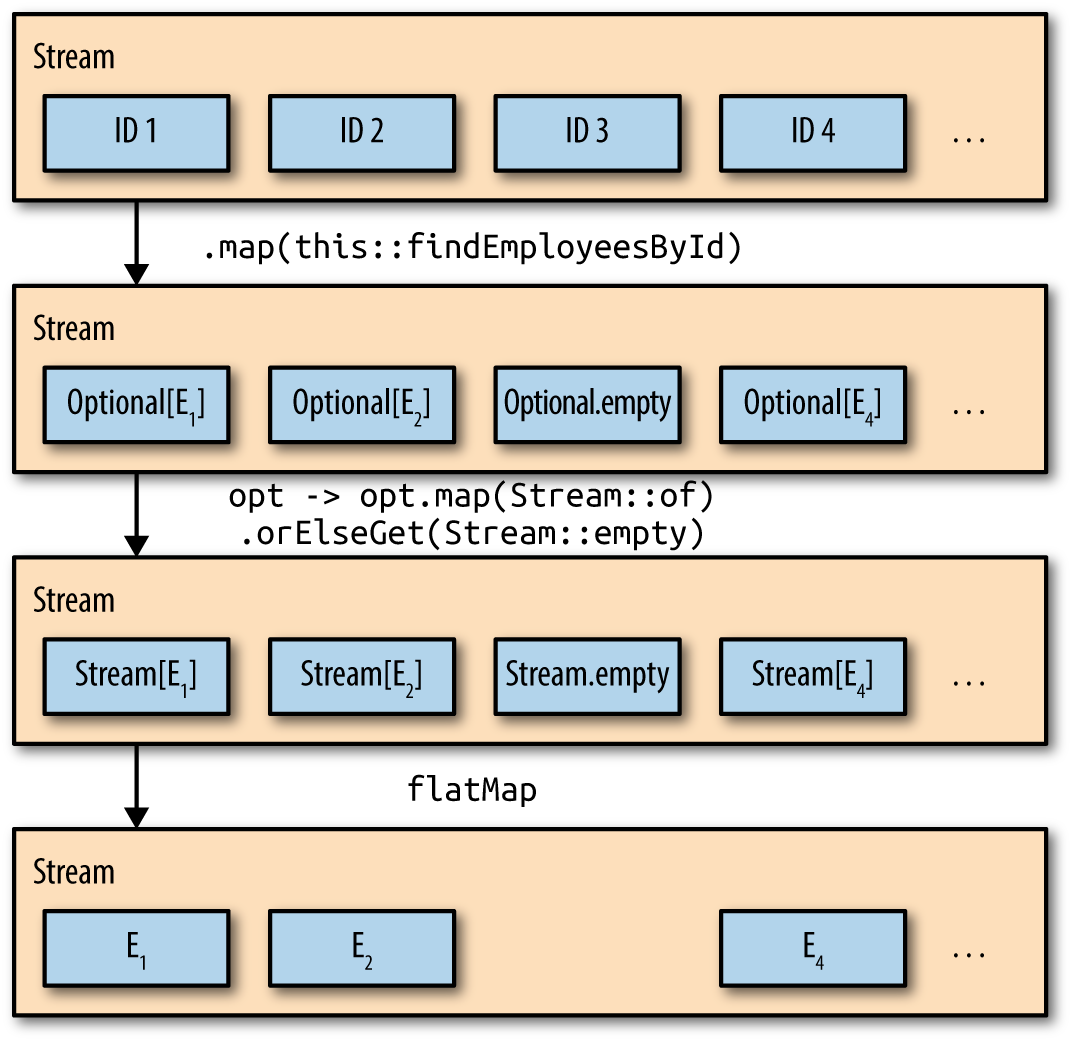

publicList<Employee>findEmployeesByIds(List<Integer>ids){returnids.stream().map(this::findEmployeeById).flatMap(optional->optional.map(Stream::of).orElseGet(Stream::empty)).collect(Collectors.toList());}

The idea is that if the optional containing an employee is not empty, invoke the Stream::of method on the contained value, which turns it into a one-element stream of that value, which is then wrapped in an Optional. Otherwise return an empty optional.

Say an employee was found by ID. The findEmployeeById method returns an Optional<Employee> for that value. The optional.map(Stream::of) method then returns an Optional containing a one-element stream holding that employee, so we have Optional<Stream<Employee>>. Then the orElseGet method extracts the contained value, yielding Stream<Employee>.

If the findEmployeeById method returned an empty Optional, then optional.map(Stream::of) returns an empty Optional as well, and the orElseGet(Stream::empty) method returns an empty stream.

The result is that you get a combination of Stream<Employee> elements and empty streams, and that’s exactly what the flatMap method in Stream was designed to handle. It reduces everything down to a Stream<Employee> for only the nonempty streams, so the collect method can return them as a List of employees.

The process is illustrated in Figure 6-1.

Figure 6-1. Optional map and flatMap

The Optional.map method is a convenience5 method for (hopefully) simplifying stream processing code. The filter/map approach discussed earlier is certainly more intuitive, especially for developers unaccustomed to flatMap operations, but the result is the same.

Of course, you can use any function you wish inside the Optional.map method. The Javadocs illustrate converting names into file input streams. A different example is shown in Recipe 6.4.

Incidentally, Java 9 adds a stream method to Optional. If the Optional is not empty, it returns a one-element stream wrapping the contained value. Otherwise it returns an empty stream. See Recipe 10.6 for details.

See Also

Recipe 6.3 illustrates how to use Optional in a DAO (data access object) layer. Recipe 3.11 discusses the flatMap method on streams, while Recipe 6.4 discusses the flatMap method on Optionals. Recipe 10.6 talks about the new methods added to Optional in Java 9.

1 I’m being diplomatic here.

2 See the sidebar about immutability.

3 See Chapter 6 of Venkat Subramaniam’s book Functional Programming in Java (Pragmatic Programmers, 2014) for a detailed explanation.

4 Perhaps this is just wishful thinking, but an appealing idea, nonetheless.

5 At least, that’s the idea.