Simple Solutions to Difficult Problems

in Java 8 and 9

Copyright © 2017 Ken Kousen. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491973172 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Modern Java Recipes, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the authors have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the authors disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-491-97317-2

[LSI]

Hey Xander, this one’s yours. Surprise!

There’s no doubt that the new features in Java 8, particularly lambda expressions and the Streams API, are a huge step forward for the Java language. I’ve been using Java 8 and telling developers about the new features at conferences, in workshops, and via blog posts for a several years now. What’s clear to me is that although lambdas and streams bring a more functional style of programming to Java (and also allow us to seamlessly make use of parallel processing power), it’s not these attributes that make them so appealing to developers once they start using them—it’s how much easier it is to solve certain types of problems using these idioms, and how much more productive they make us.

My passion as a developer, presenter, and writer is not just to make other developers aware of the evolution of the Java language, but to show how this evolution helps make our lives as developers easier—how we have options for simpler solutions to problems, or even solve different types of problems. What I love about Ken’s work is that he focuses on exactly this—helping you learn something new without having to wade through details you already know or don’t need, focusing on the parts of a technology that are valuable to real world developers.

I first came across Ken’s work when he presented “Making Java Groovy” at JavaOne. At the time, the team I was working on was struggling with writing readable and useful tests, and one of the solutions we were contemplating was Groovy. As a long-time Java programmer, I was reluctant to learn a whole new language just to write tests, especially when I thought I knew how to write tests. But seeing Ken talk about Groovy for Java programmers taught me a lot of what I needed to know without repeating things I already understood. It made me realise that with the right learning material I didn’t need to wade through all the details of a language just to learn the bits I cared about. I bought his book immediately.

This new book on Modern Java Recipes follows a similar theme—as experienced developers, we don’t need to learn everything about all the new features in Java 8 and 9 as if we’re new to the language, nor do we have the time to do that. What we need is a guide that quickly makes the relevant features available to us, that gives us real examples that apply to our jobs. This book is that guide. By presenting recipes based on the sorts of problems we encounter daily, and showing how to solve those using new features in Java 8 and 9, we become familiar with the updates to the language in a way that’s much more natural for us. We can evolve our skills.

Even those who’ve been using Java 8 and 9 can learn something. The section on Reduction Operators really helped me understand this functional-style programming without having to reprogram my brain. The Java 9 features that are covered are exactly the ones that are useful to us as developers, and they are not (yet) well known. This is an excellent way to get up to speed on the newest version of Java in a quick and effective fashion. There’s something in this book for every Java developer who wants to level up their knowledge.

Sometimes it’s hard to believe that a language with literally 20 years of backward compatibility could change so drastically. Prior to the release of Java SE 8 in March of 2014,1 for all of its success as the definitive server-side programming language, Java had acquired the reputation of being “the COBOL of the 21st century.” It was stable, pervasive, and solidly focused on performance. Changes came slowly when they came at all, and companies felt little urgency to upgrade when new versions became available.

That all changed when Java SE 8 was released. Java SE 8 included “Project Lambda,” the major innovation that introduced functional programming concepts into what was arguably the world’s leading object-oriented language. Lambda expressions, method references, and streams fundamentally changed the idioms of the language, and developers have been trying to catch up ever since.

The attitude of this book is not to judge whether the changes are good or bad or could have been done differently. The goal here is to say, “this is what we have, and this is how you use it to get your job done.” That’s why this book is designed as a recipes book. It’s all about what you need to do, and how the new features in Java help you do it.

That said, there are a lot of advantages to the new programming model, once you get used to them. Functional code tends to be simpler and easier to both write and understand. The functional approach favors immutability, which makes writing concurrent code cleaner and more likely to be successful. Back when Java was created, you could still rely on Moore’s law to double your processor speed roughly every 18 months. These days performance improvements come from the fact that even most phones have multiple processors.

Since Java has always been sensitive to backward compatibility, many companies and developers have moved to Java SE 8 without adopting the new idioms. The platform is more powerful even so, and is worth using, not to mention the fact that Oracle formally declared Java 7 end-of-life in April 2015.

It has taken a couple of years, but most Java developers are now working with the Java 8 JDK, and it’s time to dig in and understand what that means and what consequences it has for your future development. This book is designed to make that process easier.

The recipes in this book assume that the typical reader already is comfortable with Java versions prior to Java SE 8. You don’t need to be an expert, and some older concepts are reviewed, but the book is not intended to be a beginner’s guide to Java or object-oriented programming. If you have used Java on a project before and you are familiar with the standard library, you’ll be fine.

This book covers almost all of Java SE 8, and includes one chapter focused on the new changes coming in Java 9. If you need to understand how the new functional idioms added to the language will change the way you write code, this book is a use-case-driven way of accomplishing that goal.

Java is pervasive on the server side, with a rich support system of open source libraries and tools. The Spring Framework and Hibernate are two of the most popular open source frameworks, and both either require Java 8 as a minimum or will very soon. If you plan to operate in this ecosystem, this book is for you.

This book is organized into recipes, but it’s difficult to discuss recipes containing lambda expressions, method references, and streams individually without referring to the others. In fact, the first six chapters discuss related concepts, though you don’t have to read them in any particular order.

The chapters are organized as follows:

Chapter 1, The Basics, covers the basics of lambda expressions and method references, and follows with the new features of interfaces: default methods and static methods. It also defines the term “functional interface” and explains how it is key to understanding lambda expressions.

Chapter 2, The java.util.function Package, presents the new java.util.function package, which was added to the language in Java 8. The interfaces in that package fall into four special categories (consumers, suppliers, predicates, and functions) that are used throughout the rest of the standard library.

Chapter 3, Streams, adds in the concept of streams, and how they represent an abstraction that allows you to transform and filter data rather than process it iteratively. The concepts of “map,” “filter,” and “reduce” relate to streams, as shown in the recipes in this chapter. They ultimately lead to the ideas of parallelism and concurrency covered in Chapter 9.

Chapter 4, Comparators and Collectors, involves the sorting of streaming data, and converting it back into collections. Partitioning and grouping is also part of this chapter, which turns what are normally considered database operations into easy library calls.

Chapter 5, Issues with Streams, Lambdas, and Method References, is a miscellaneous chapter; the idea being that now that you know how to use lambdas, method references, and streams, you can look at ways they can be combined to solve interesting problems. The concepts of laziness, deferred execution, and closure composition are also covered, as is the annoying topic of exception handling.

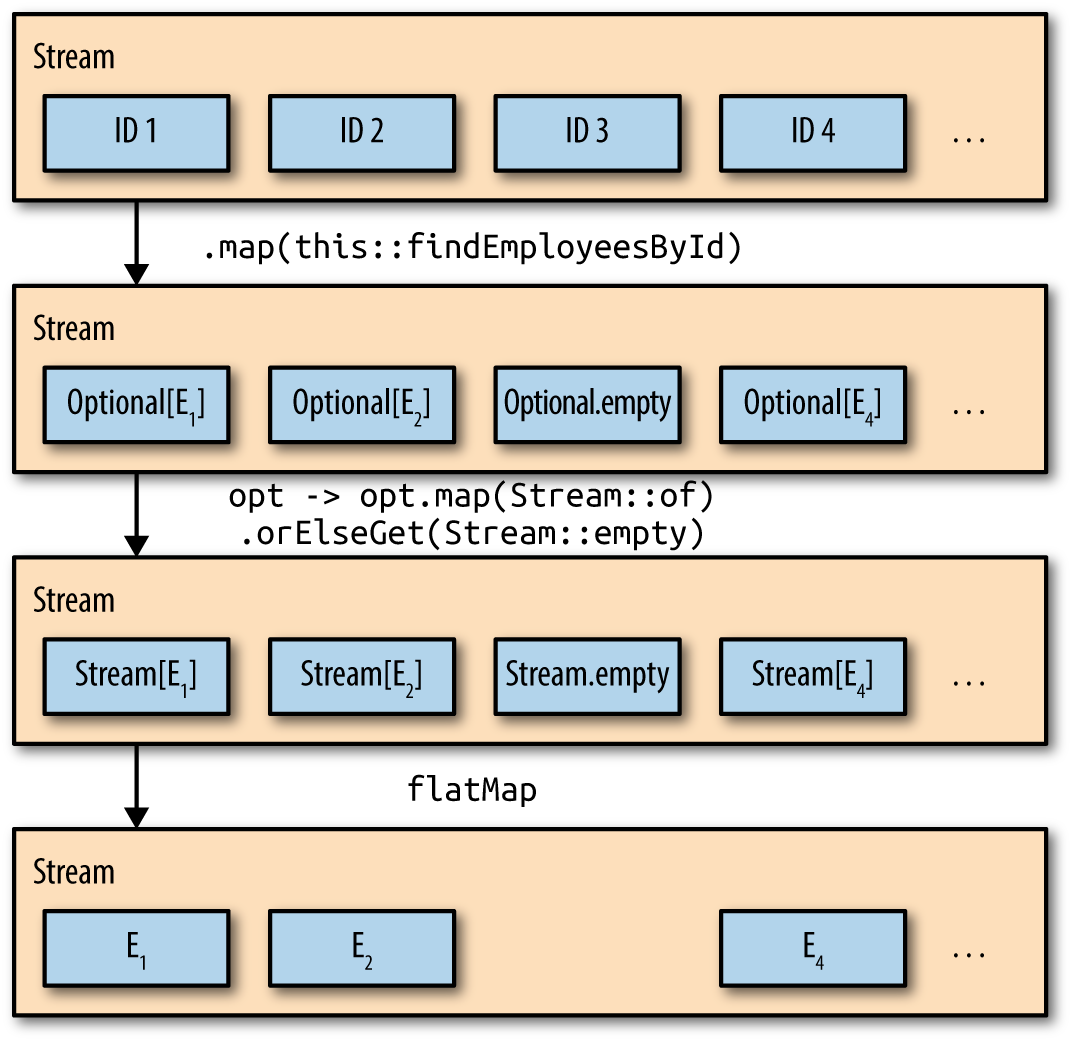

Chapter 6, The Optional Type, discusses one of the more controversial additions to the language—the Optional type. Recipes in this chapter describe how the new type is intended to be used and how you can both create instances and extract values from them. This chapter also revisits the functional idea of map and flat-map operations on Optionals, and how they differ from the same operations on streams.

Chapter 7, File I/O, switches to the practical topic of input/output streams (as opposed to functional streams), and the additions made to the standard library to incorporate the new functional concepts when dealing with files and directories.

Chapter 8, The java.time Package, shows the basics of the new Date-Time API, and how (at long last) they replace the legacy Date and Calendar classes. The new API is based on the Joda-Time library, which is backed by many developer-years of experience and use and has been rewritten to form the java.time package. Frankly, if this had been the only addition to Java 8, it would have been worth the upgrade.

Chapter 9, Parallelism and Concurrency, addresses one of the implicit promises of the stream model: that you can change a sequential stream to a parallel one with a single method call, and thereby take advantage of all the processors available on your machine. Concurrency is a big topic, but this chapter presents the additions to the Java library that make it easy to experiment with and assess when the costs and benefits are worth the effort.

Chapter 10, Java 9 Additions, covers many of the changes coming in Java 9, which is currently scheduled to be released September 21, 2017. The details of Jigsaw can fill an entire book by themselves, but the basics are clear and are described in this chapter. Other recipes cover private methods in interfaces, the new methods added to streams, collectors, and Optional, and how to create a stream of dates.2

Appendix A, Generics and Java 8, is about the generics capabilities in Java. While generics as a technology was added back in 1.5, most developers only learned the minimum they needed to know to make them work. One glance at the Javadocs for Java 8 and 9 shows that those days are over. The goal of the appendix is to show you how to read and interpret the API so you understand the much more complex method signatures involved.

The chapters, and indeed the recipes themselves, do not have to be read in any particular order. They do complement each other and each recipe ends with references to others, but you can start reading anywhere. The chapter groupings are provided as a way to put similar recipes together, but it is expected that you will jump from one to another to solve whatever problem you may have at the moment.

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant widthUsed for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width boldShows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italicShows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element signifies a general note.

This element indicates a warning or caution.

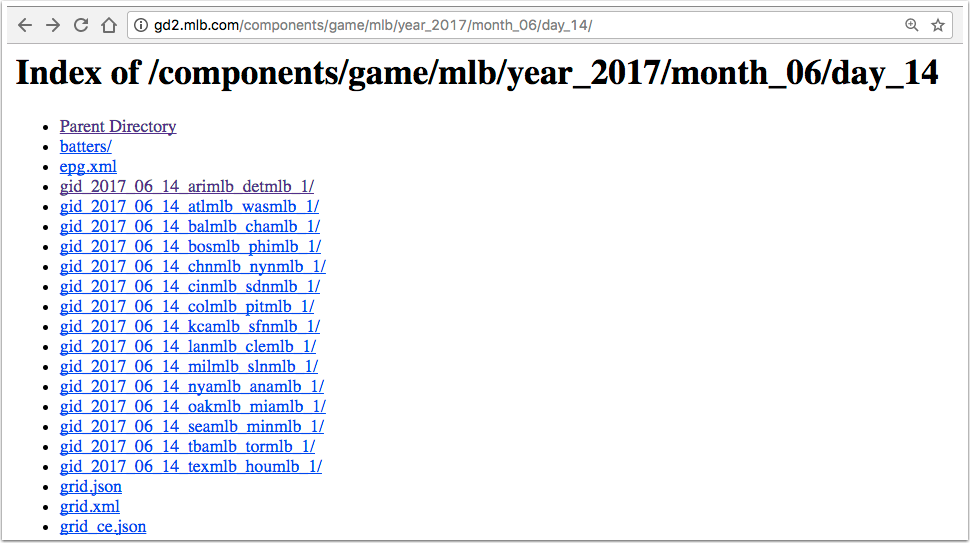

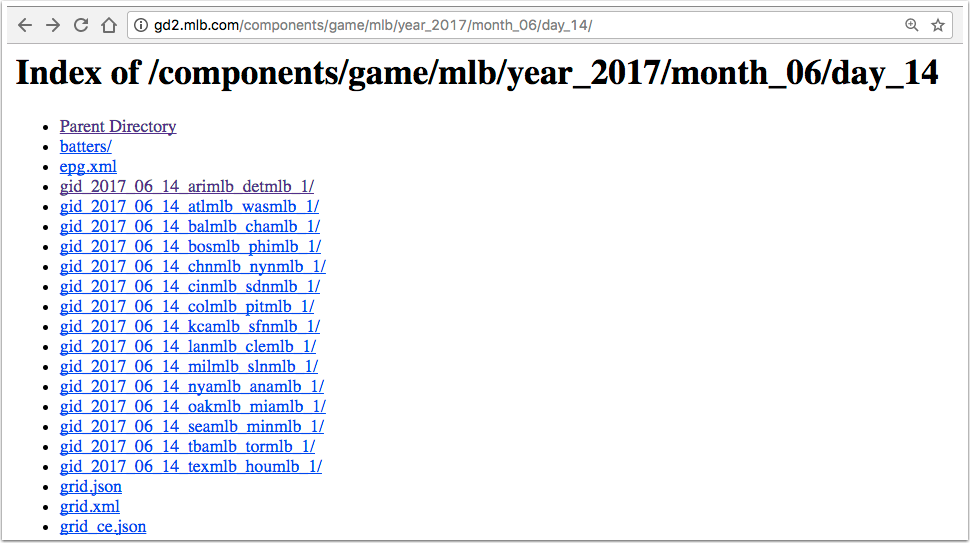

The source code for the book is located in three GitHub repositories: one for the Java 8 recipes (everything but Chapter 10) at https://github.com/kousen/java_8_recipes, one for the Java 9 recipes at https://github.com/kousen/java_9_recipes, and a special one for the larger CompletableFuture example in Recipe 9.7 at https://github.com/kousen/cfboxscores. All are configured as Gradle projects with tests and a build file.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Modern Java Recipes by Ken Kousen (O’Reilly). Copyright 2017 Ken Kousen, 978-0-491-97317-2.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Learning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including O’Reilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

This book is the unexpected result of a conversation I had with Jay Zimmerman back in late July 2015. I was (and still am) a member of the No Fluff, Just Stuff conference tour, and that year several Java 8 talks were being given by Venkat Subramaniam. Jay told me that Venkat had decided to scale back his activity in the coming year and Jay was wondering whether I would be willing to do similar talks in the new season starting in early 2016. I had been coding in Java since the mid-’90s (I started with Java 1.0.6) and had been planning to learn the new APIs anyway, so I agreed.

I have now been giving presentations on the new functional features of Java for a couple of years. By the Fall of 2016 I had completed my last book,3 and since the idea was to write another recipes book for the same publisher I foolishly thought the project would be easy.

Noted science fiction author Neil Gaiman famously once said that after finishing American Gods he thought he knew how to write a novel. His friend corrected him, saying he now knew how to write this novel. I now understand what he meant. The original proposal for this book anticipated about 25 to 30 recipes spanning about 150 pages. The final result you hold in your hand has more than 70 recipes filling nearly 300 pages, but the larger scope and greater detail has produced a much more valuable book than I intended.

Of course, that’s because I had lots of help. The aforementioned Venkat Subramaniam has been extremely helpful, both through his talks, his other books, and private discussions. He also was kind enough to be a technical reviewer on this book, so any remaining errors are all his fault. (No, they’re mine, but please don’t tell him I admitted that.)

I also am very grateful to have had the frequent assistance of Tim Yates, who is one of the best coders I’ve ever met. I knew him from his work in the Groovy community, but his versatility goes well beyond that, as his Stack Overflow rating will show. Rod Hilton, who I met while giving Java 8 presentations on the NFJS tour, was also kind enough to offer a review. Both of their recommendations have been invaluable.

I have been fortunate enough to work with the excellent editors and staff at O’Reilly Media over the course of two books, over a dozen video courses, and many online training classes delivered on their Safari online platform. Brian Foster has been a constant source of support, not to mention his almost magical ability to cut through bureaucracy. I met him while writing my previous book, and though he wasn’t the editor of this one, his help and friendship have been very valuable to me throughout the process.

My editor, Jeff Bleiel, was very understanding as the book doubled in length, and provided the structure and organization needed to keep making progress. I’m very glad we got to work together and hope we will continue to do so in the future.

I need to acknowledge many of my fellow speakers on the NFJS tour, including Nate Schutta, Michael Carducci, Matt Stine, Brian Sletten, Mark Richards, Pratik Patel, Neal Ford, Craig Walls, Raju Gandhi, Kirk Knoernschild, Dan “the Man” Hinojosa, and Janelle Klein for their constant perspective and encouragement. Both writing books and teaching training classes (my actual day job) are solitary pursuits. It’s great having a community of friends and colleagues that I can rely on for perspective, advice, and various forms of entertainment.

Finally, I need to express all my love to my wife Ginger and my son Xander. Without the support and kindness of my family I would not be the person I am today, a fact that grows more obvious to me with each passing year. I can never express what you both mean to me.

1 Yes, it’s actually been over three years since the first release of Java SE 8. I can’t believe it either.

2 Yes, I too wish that the Java 9 chapter had been Chapter 9, but it didn’t seem right to reorder the chapters just for that accidental symmetry. This footnote will have to suffice.

3 Gradle Recipes for Android, also from O’Reilly Media, all about the Gradle build tool as it is applied to Android projects.

The biggest change in Java 8 is the addition of concepts from functional programming to the language. Specifically, the language added lambda expressions, method references, and streams.

If you haven’t used the new functional features yet, you’ll probably be surprised by how different your code will look from previous Java versions. The changes in Java 8 represent the biggest changes to the language ever. In many ways, it feels like you’re learning a completely new language.

The question then becomes: Why do this? Why make such drastic changes to a language that’s already twenty years old and plans to maintain backward compatibility? Why make such dramatic revisions to a language that has been, by all accounts, extremely successful? Why switch to a functional paradigm after all these years of being one of the most successful object-oriented languages ever?

The answer is that the software development world has changed, so languages that want to be successful in the future need to adapt as well. Back in the mid-’90s, when Java was shiny and new, Moore’s law1 was still fully in force. All you had to do was wait a couple of years and your computer would double in speed.

Today’s hardware no longer relies on increasing chip density for speed. Instead, even most phones have multiple cores, which means software needs to be written expecting to be run in a multiprocessor environment. Functional programming, with its emphasis on “pure” functions (that return the same result given the same inputs, with no side effects) and immutability simplifies programming in parallel environments. If you don’t have any shared, mutable state, and your program can be decomposed into collections of simple functions, it is easier to understand and predict its behavior.

This, however, is not a book about Haskell, or Erlang, or Frege, or any of the other functional programming languages. This book is about Java, and the changes made to the language to add functional concepts to what is still fundamentally an object-oriented language.

Java now supports lambda expressions, which are essentially methods treated as though they were first-class objects. The language also has method references, which allow you to use an existing method wherever a lambda expression is expected. In order to take advantage of lambda expressions and method references, the language also added a stream model, which produces elements and passes them through a pipeline of transformations and filters without modifying the original source.

The recipes in this chapter describe the basic syntax for lambda expressions, method references, and functional interfaces, as well the new support for static and default methods in interfaces. Streams are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

Use one of the varieties of lambda expression syntax and assign the result to a reference of functional interface type.

A functional interface is an interface with a single abstract method (SAM). A class implements any interface by providing implementations for all the methods in it. This can be done with a top-level class, an inner class, or even an anonymous inner class.

For example, consider the Runnable interface, which has been in Java since version 1.0. It contains a single abstract method called run, which takes no arguments and returns void. The Thread class constructor takes a Runnable as an argument, so an anonymous inner class implementation is shown in Example 1-1.

publicclassRunnableDemo{publicstaticvoidmain(String[]args){newThread(newRunnable(){@Overridepublicvoidrun(){System.out.println("inside runnable using an anonymous inner class");}}).start();}}

The anonymous inner class syntax consists of the word new followed by the Runnable interface name and parentheses, implying that you’re defining a class without an explicit name that implements that interface. The code in the braces ({}) then overrides the run method, which simply prints a string to the console.

The code in Example 1-2 shows the same example using a lambda expression.

newThread(()->System.out.println("inside Thread constructor using lambda")).start();

The syntax uses an arrow to separate the arguments (since there are zero arguments here, only a pair of empty parentheses is used) from the body. In this case, the body consists of a single line, so no braces are required. This is known as an expression lambda. Whatever value the expression evaluates to is returned automatically. In this case, since println returns void, the return from the expression is also void, which matches the return type of the run method.

A lambda expression must match the argument types and return type in the signature of the single abstract method in the interface. This is called being compatible with the method signature. The lambda expression is thus the implementation of the interface method, and can also be assigned to a reference of that interface type.

As a demonstration, Example 1-3 shows the lambda assigned to a variable.

Runnabler=()->System.out.println("lambda expression implementing the run method");newThread(r).start();

There is no class in the Java library called Lambda. Lambda expressions can only be assigned to functional interface references.

Assigning a lambda to the functional interface is the same as saying the lambda is the implementation of the single abstract method inside it. You can think of the lambda as the body of an anonymous inner class that implements the interface. That is why the lambda must be compatible with the abstract method; its argument types and return type must match the signature of that method. Notably, however, the name of the method being implemented is not important. It does not appear anywhere as part of the lambda expression syntax.

This example was especially simple because the run method takes no arguments and returns void. Consider instead the functional interface java.io.FilenameFilter, which again has been part of the Java standard library since version 1.0. Instances of FilenameFilter are used as arguments to the File.list method to restrict the returned files to only those that satisfy the method.

From the Javadocs, the FilenameFilter class contains the single abstract method accept, with the following signature:

booleanaccept(Filedir,Stringname)

The File argument is the directory in which the file is found, and the String name is the name of the file.

The code in Example 1-4 implements FilenameFilter using an anonymous inner class to return only Java source files.

Filedirectory=newFile("./src/main/java");String[]names=directory.list(newFilenameFilter(){@Overridepublicbooleanaccept(Filedir,Stringname){returnname.endsWith(".java");}});System.out.println(Arrays.asList(names));

In this case, the accept method returns true if the filename ends with .java and false otherwise.

The lambda expression version is shown in Example 1-5.

Filedirectory=newFile("./src/main/java");String[]names=directory.list((dir,name)->name.endsWith(".java"));System.out.println(Arrays.asList(names));}

The resulting code is much simpler. This time the arguments are contained within parentheses, but do not have types declared. At compile time, the compiler knows that the list method takes an argument of type FilenameFilter, and therefore knows the signature of its single abstract method (accept). It therefore knows that the arguments to accept are a File and a String, so that the compatible lambda expression arguments must match those types. The return type on accept is a boolean, so the expression to the right of the arrow must also return a boolean.

If you wish to specify the data types in the code, you are free to do so, as in Example 1-6.

Filedirectory=newFile("./src/main/java");String[]names=directory.list((Filedir,Stringname)->name.endsWith(".java"));

Finally, if the implementation of the lambda requires more than one line, you need to use braces and an explicit return statement, as shown in Example 1-7.

Filedirectory=newFile("./src/main/java");String[]names=directory.list((Filedir,Stringname)->{returnname.endsWith(".java");});System.out.println(Arrays.asList(names));

This is known as a block lambda. In this case the body still consists of a single line, but the braces now allow for multiple statements. The return keyword is now required.

Lambda expressions never exist alone. There is always a context for the expression, which indicates the functional interface to which the expression is assigned. A lambda can be an argument to a method, a return type from a method, or assigned to a reference. In each case, the type of the assignment must be a functional interface.

(double colon) notation in method references”)))

If a lambda expression is essentially treating a method as though it was a object, then a method reference treats an existing method as though it was a lambda.

For example, the forEach method in Iterable takes a Consumer as an argument. Example 1-8 shows that the Consumer can be implemented as either a lambda expression or as a method reference.

Stream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).forEach(x->System.out.println(x));Stream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).forEach(System.out::println);Consumer<Integer>printer=System.out::println;Stream.of(3,1,4,1,5,9).forEach(printer);

The double-colon notation provides the reference to the println method on the System.out instance, which is a reference of type PrintStream. No parentheses are placed at the end of the method reference. In the example shown, each element of the stream is printed to standard output.2

If you write a lambda expression that consists of one line that invokes a method, consider using the equivalent method reference instead.

The method reference provides a couple of (minor) advantages over the lambda syntax. First, it tends to be shorter, and second, it often includes the name of the class containing the method. Both make the code easier to read.

Method references can be used with static methods as well, as shown in Example 1-9.

Stream.generate(Math::random).limit(10).forEach(System.out::println);

The generate method on Stream takes a Supplier as an argument, which is a functional interface whose single abstract method takes no arguments and produces a single result. The random method in the Math class is compatible with that signature, because it also takes no arguments and produces a single, uniformly distributed, pseudorandom double between 0 and 1. The method reference Math::random refers to that method as the implementation of the Supplier interface.

Since Stream.generate produces an infinite stream, the limit method is used to ensure only 10 values are produced, which are then printed to standard output using the System.out::println method reference as an implementation of Consumer.

There are three forms of the method reference syntax, and one is a bit misleading:

object::instanceMethodRefer to an instance method using a reference to the supplied object, as in System.out::println

Class::staticMethodRefer to static method, as in Math::max

Class::instanceMethodInvoke the instance method on a reference to an object supplied by the context, as in String::length

That last example is the confusing one, because as Java developers we’re accustomed to seeing only static methods invoked via a class name. Remember that lambda expressions and method references never exist in a vacuum—there’s always a context. In the case of an object reference, the context will supply the argument(s) to the method. In the printing case, the equivalent lambda expression is (as shown in context in Example 1-8):

// equivalent to System.out::printlnx->System.out.println(x)

The context provides the value of x, which is used as the method argument.

The situation is similar for the static max method:

// equivalent to Math::max(x,y)->Math.max(x,y)

Now the context needs to supply two arguments, and the lambda returns the greater one.

The “instance method through the class name” syntax is interpreted differently. The equivalent lambda is:

// equivalent to String::lengthx->x.length()

This time, when the context provides x, it is used as the target of the method, rather than as an argument.

If you refer to a method that takes multiple arguments via the class name, the first element supplied by the context becomes the target and the remaining elements are arguments to the method.

Example 1-10 shows the sample code.

List<String>strings=Arrays.asList("this","is","a","list","of","strings");List<String>sorted=strings.stream().sorted((s1,s2)->s1.compareTo(s2)).collect(Collectors.toList());List<String>sorted=strings.stream().sorted(String::compareTo).collect(Collectors.toList());

The sorted method on Stream takes a Comparator<T> as an argument, whose single abstract method is int compare(String other). The sorted method supplies each pair of strings to the comparator and sorts them based on the sign of the returned integer. In this case, the context is a pair of strings. The method reference syntax, using the class name String, invokes the compareTo method on the first element (s1 in the lambda expression) and uses the second element s2 as the argument to the method.

In stream processing, you frequently access an instance method using the class name in a method reference if you are processing a series of inputs. The code in Example 1-11 shows the invocation of the length method on each individual String in the stream.

Stream.of("this","is","a","stream","of","strings").map(String::length).forEach(System.out::println);

This example transforms each string into an integer by invoking the length method, then prints each result.

A method reference is essentially an abbreviated syntax for a lambda. Lambda expressions are more general, in that each method reference has an equivalent lambda expression but not vice versa. The equivalent lambdas for the method references from Example 1-11 are shown in Example 1-12.

Stream.of("this","is","a","stream","of","strings").map(s->s.length()).forEach(x->System.out.println(x));

As with any lambda expression, the context matters. You can also use this or super as the left side of a method reference if there is any ambiguity.

You can also invoke constructors using the method reference syntax. Constructor references are shown in Recipe 1.3. The package of functional interfaces, including the Supplier interface discussed in this recipe, is covered in Chapter 2.

When people talk about the new syntax added to Java 8, they mention lambda expressions, method references, and streams. For example, say you had a list of people and you wanted to convert it to a list of names. One way to do so would be the snippet shown in Example 1-13.

List<String>names=people.stream().map(person->person.getName()).collect(Collectors.toList());// or, alternatively,List<String>names=people.stream().map(Person::getName).collect(Collectors.toList());

What if you want to go the other way? What if you have a list of strings and you want to create a list of Person references from it? In that case you can use a method reference, but this time using the keyword new. That syntax is called a constructor reference.

To show how it is used, start with a Person class, which is just about the simplest Plain Old Java Object (POJO) imaginable. All it does is wrap a simple string attribute called name in Example 1-14.

publicclassPerson{privateStringname;publicPerson(){}publicPerson(Stringname){this.name=name;}// getters and setters ...// equals, hashCode, and toString methods ...}

Given a collection of strings, you can map each one into a Person using either a lambda expression or the constructor reference in Example 1-15.

List<String>names=Arrays.asList("Grace Hopper","Barbara Liskov","Ada Lovelace","Karen Spärck Jones");List<Person>people=names.stream().map(name->newPerson(name)).collect(Collectors.toList());// or, alternatively,List<Person>people=names.stream().map(Person::new).collect(Collectors.toList());

The syntax Person::new refers to the constructor in the Person class. As with all lambda expressions, the context determines which constructor is executed. Because the context supplies a string, the one-arg String constructor is used.

A copy constructor takes a Person argument and returns a new Person with the same attributes, as shown in Example 1-16.

publicPerson(Personp){this.name=p.name;}

This is useful if you want to isolate streaming code from the original instances. For example, if you already have a list of people, convert the list into a stream, and then back into a list, the references are the same (see Example 1-17).

Personbefore=newPerson("Grace Hopper");List<Person>people=Stream.of(before).collect(Collectors.toList());Personafter=people.get(0);assertTrue(before==after);before.setName("Grace Murray Hopper");assertEquals("Grace Murray Hopper",after.getName());

Using a copy constructor, you can break that connection, as in Example 1-18.

people=Stream.of(before).map(Person::new).collect(Collectors.toList());after=people.get(0);assertFalse(before==after);assertEquals(before,after);before.setName("Rear Admiral Dr. Grace Murray Hopper");assertFalse(before.equals(after));

This time, when invoking the map method, the context is a stream of Person instances. Therefore the Person::new syntax invokes the constructor that takes a Person and returns a new, but equivalent, instance, and has broken the connection between the before reference and the after reference.3

Consider now a varargs constructor added to the Person POJO, shown in Example 1-19.

publicPerson(String...names){this.name=Arrays.stream(names).collect(Collectors.joining(" "));}

This constructor takes zero or more string arguments and concatenates them together with a single space as the delimiter.

How can that constructor get invoked? Any client that passes zero or more string arguments separated by commas will call it. One way to do that is to take advantage of the split method on String that takes a delimiter and returns a String array:

String[]split(Stringdelimiter)

Therefore, the code in Example 1-20 splits each string in the list into individual words and invokes the varargs constructor.

names.stream().map(name->name.split(" ")).map(Person::new).collect(Collectors.toList());

This time, the context for the map method that contains the Person::new constructor reference is a stream of string arrays, so the varargs constructor is called. If you add a simple print statement to that constructor:

System.out.println("Varargs ctor, names="+Arrays.asList(names));

then the result is:

Varargs ctor, names=[Grace, Hopper] Varargs ctor, names=[Barbara, Liskov] Varargs ctor, names=[Ada, Lovelace] Varargs ctor, names=[Karen, Spärck, Jones]

Constructor references can also be used with arrays. If you want an array of Person instances, Person[], instead of a list, you can use the toArray method on Stream, whose signature is:

<A>A[]toArray(IntFunction<A[]>generator)

This method uses A to represent the generic type of the array returned containing the elements of the stream, which is created using the provided generator function. The cool part is that a constructor reference can be used for that, too, as in Example 1-21.

Person[]people=names.stream().map(Person::new).toArray(Person[]::new);

The toArray method argument creates an array of Person references of the proper size and populates it with the instantiated Person instances.

Constructor references are just method references by another name, using the word new to invoke a constructor. Which constructor is determined by the context, as usual. This technique gives a lot of flexibility when processing streams.

Method references are discussed in Recipe 1.2.

A functional interface in Java 8 is an interface with a single, abstract method. As such, it can be the target for a lambda expression or method reference.

The use of the term abstract here is significant. Prior to Java 8, all methods in interfaces were considered abstract by default—you didn’t even need to add the keyword.

For example, here is the definition of an interface called PalindromeChecker, shown in Example 1-22.

@FunctionalInterfacepublicinterfacePalindromeChecker{booleanisPalidrome(Strings);}

All methods in an interface are public,4 so you can leave out the access modifier, just as you can leave out the abstract keyword.

Since this interface has only a single, abstract method, it is a functional interface. Java 8 provides an annotation called @FunctionalInterface in the java.lang package that can be applied to the interface, as shown in the example.

This annotation is not required, but is a good idea, for two reasons. First, it triggers a compile-time check that the interface does, in fact, satisfy the requirement. If the interface has either zero abstract methods or more than one, you will get a compiler error.

The other benefit to adding the @FunctionalInterface annotation is that it generates a statement in the Javadocs as follows:

Functional Interface: This is a functional interface and can therefore be used as the assignment target for a lambda expression or method reference.

Functional interfaces can have default and static methods as well. Both default and static methods have implementations, so they don’t count against the single abstract method requirement. Example 1-23 shows the sample code.

@FunctionalInterfacepublicinterfaceMyInterface{intmyMethod();// int myOtherMethod();defaultStringsayHello(){return"Hello, World!";}staticvoidmyStaticMethod(){System.out.println("I'm a static method in an interface");}}

Note that if the commented method myOtherMethod was included, the interface would no longer satisfy the functional interface requirement. The annotation would generate an error of the form “multiple non-overriding abstract methods found.”

Interfaces can extend other interfaces, even more than one. The annotation checks the current interface. So if one interface extends an existing functional interface and adds another abstract method, it is not itself a functional interface. See Example 1-24.

publicinterfaceMyChildInterfaceextendsMyInterface{intanotherMethod();}

The MyChildInterface is not a functional interface, because it has two abstract methods: myMethod, which it inherits from MyInterface; and anotherMethod, which it declares. Without the @FunctionalInterface annotation, this compiles, because it’s a standard interface. It cannot, however, be the target of a lambda expression.

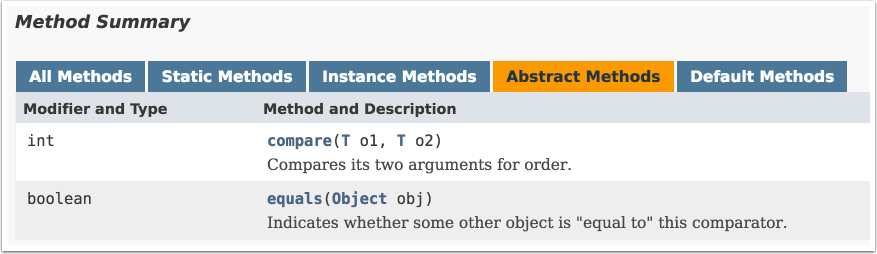

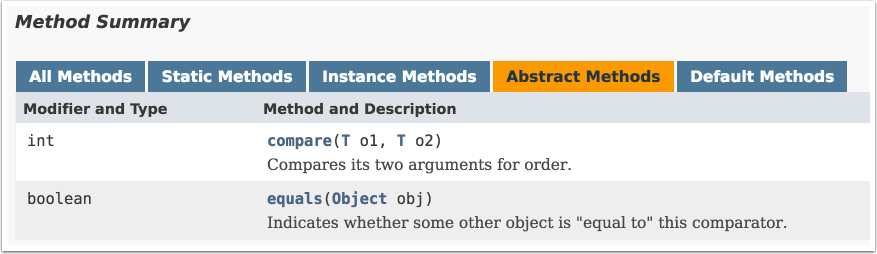

One edge case should also be noted. The Comparator interface is used for sorting, which is discussed in other recipes. If you look at the Javadocs for that interface and select the Abstract Methods tab, you see the methods shown in Figure 1-1.

Wait, what? How can this be a functional interface if there are two abstract methods, especially if one of them is actually implemented in java.lang.Object?

What is special here is that the equals method shown is from Object, and therefore already has a default implementation. The detailed documentation says that for performance reasons you can supply your own equals method that satisfies the same contract, but that “it is always safe not (emphasis in original) to override” this method.

The rules for functional interfaces say that methods from Object don’t count against the single abstract method limit, so Comparator is still a functional interface.

Default methods in interfaces are discussed in Recipe 1.5, and static methods in interfaces are discussed in Recipe 1.6.

Use the keyword default on the interface method, and add the implementation in the normal way.

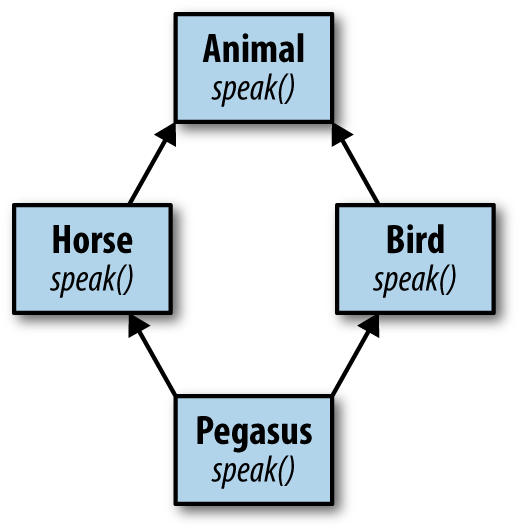

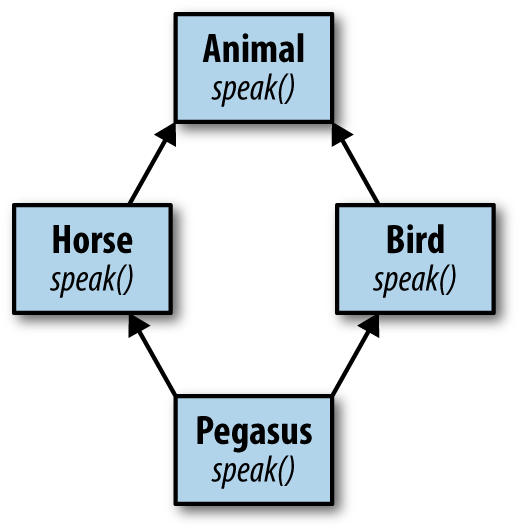

The traditional reason Java never supported multiple inheritance is the so-called diamond problem. Say you have an inheritance hierarchy as shown in the (vaguely UML-like) Figure 1-2.

Class Animal has two child classes, Bird and Horse, each of which overrides the speak method from Animal, in Horse to say “whinny” and in Bird to say “chirp.” What, then, does Pegasus (which multiply inherits from both Horse and Bird)5 say? What if you have a reference of type Animal assigned to an instance of Pegasus? What then should the speak method return?

Animalanimal=newPegaus();animal.speak();// whinny, chirp, or other?

Different languages take different approaches to this problem. In C++, for example, multiple inheritance is allowed, but if a class inherits conflicting implementations, it won’t compile.6 In Eiffel,7 the compiler allows you to choose which implementation you want.

Java’s approach was to prohibit multiple inheritance, and interfaces were introduced as a workaround for when a class has an “is a kind of” relationship with more than one type. Since interfaces had only abstract methods, there were no implementations to conflict. Multiple inheritance is allowed with interfaces, but again that works because only the method signatures are inherited.

The problem is, if you can never implement a method in an interface, you wind up with some awkward designs. Among the methods in the java.util.Collection interface, for example, are:

booleanisEmpty()intsize()

The isEmpty method returns true if there are no elements in the collection, and false otherwise. The size method returns the number of elements in the collections. Regardless of the underlying implementation, you can immediately implement the isEmpty method in terms of size, as in Example 1-25.

publicbooleanisEmpty(){returnsize()==0;}

Since Collection is an interface, you can’t do this in the interface itself. Instead, the standard library includes an abstract class called java.util.AbstractCollection, which includes, among other code, exactly the implementation of isEmpty shown here. If you are creating your own collection implementation and you don’t already have a superclass, you can extend AbstractCollection and you get the isEmpty method for free. If you already have a superclass, you have to implement the Collection interface instead and remember to provide your own implementation of isEmpty as well as size.

All of this is quite familiar to experienced Java developers, but as of Java 8 the situation changes. Now you can add implementations to interface methods. All you have to do is add the keyword default to a method and provide an implementation. The code in Example 1-26 shows an interface with both abstract and default methods.

publicinterfaceEmployee{StringgetFirst();StringgetLast();voidconvertCaffeineToCodeForMoney();defaultStringgetName(){returnString.format("%s %s",getFirst(),getLast());}}

The getName method has the keyword default, and its implementation is in terms of the other, abstract, methods in the interface, getFirst and getLast.

Many of the existing interfaces in Java have been enhanced with default methods in order to maintain backward compatibility. Normally when you add a new method to an interface, you break all the existing implementations. By adding a new method as a default, all the existing implementations inherit the new method and still work. This allowed the library maintainers to add new default methods throughout the JDK without breaking existing implementations.

For example, java.util.Collection now contains the following default methods:

defaultbooleanremoveIf(Predicate<?superE>filter)defaultStream<E>stream()defaultStream<E>parallelStream()defaultSpliterator<E>spliterator()

The removeIf method removes all of the elements from the collection that satisfy the Predicate8 argument, returning true if any elements were removed. The stream and parallelStream methods are factory methods for creating streams. The spliterator method returns an object from a class that implements the Spliterator interface, which is an object for traversing and partitioning elements from a source.

Default methods are used the same way any other methods are used, as Example 1-27 shows.

List<Integer>nums=newArrayList<>();nums.add(-3);nums.add(1);nums.add(4);nums.add(-1);nums.add(5);nums.add(9);booleanremoved=nums.removeIf(n->n<=0);System.out.println("Elements were "+(removed?"":"NOT")+" removed");nums.forEach(System.out::println);

What happens when a class implements two interfaces with the same default method? That is the subject of Recipe 5.5, but the short answer is that if the class implements the method itself everything is fine. See Recipe 5.5 for details.

Recipe 5.5 shows the rules that apply when a class implements multiple interfaces with default methods.

Make the method static and provide the implementation in the usual way.

Static members of Java classes are class-level, meaning they are associated with the class as a whole rather than with a particular instance. That makes their use in interfaces problematic from a design point of view. Some questions include:

What does a class-level member mean when the interface is implemented by many different classes?

Does a class need to implement an interface in order to use a static method?

Static methods in classes are accessed by the class name. If a class implements an interface, does a static method get called from the class name or the interface name?

The designers of Java could have decided these questions in several different ways. Prior to Java 8, the decision was not to allow static members in interfaces at all.

Unfortunately, however, that led to the creation of utility classes: classes that contain only static methods. A typical example is java.util.Collections, which contains methods for sorting and searching, wrapping collections in synchronized or unmodifiable types, and more. In the NIO package, java.nio.file.Paths is another example. It contains only static methods that parse Path instances from strings or URIs.

Now, in Java 8, you can add static methods to interfaces whenever you like. The requirements are:

Add the static keyword to the method.

Provide an implementation (which cannot be overridden). In this way they are like default methods, and are included in the default tab in the Javadocs.

Access the method using the interface name. Classes do not need to implement an interface to use its static methods.

One example of a convenient static method in an interface is the comparing method in java.util.Comparator, along with its primitive variants, comparingInt, comparingLong, and comparingDouble. The Comparator interface also has static methods naturalOrder and reverseOrder. Example 1-28 shows how they are used.

List<String>bonds=Arrays.asList("Connery","Lazenby","Moore","Dalton","Brosnan","Craig");List<String>sorted=bonds.stream().sorted(Comparator.naturalOrder()).collect(Collectors.toList());// [Brosnan, Connery, Craig, Dalton, Lazenby, Moore]sorted=bonds.stream().sorted(Comparator.reverseOrder()).collect(Collectors.toList());// [Moore, Lazenby, Dalton, Craig, Connery, Brosnan]sorted=bonds.stream().sorted(Comparator.comparing(String::toLowerCase)).collect(Collectors.toList());// [Brosnan, Connery, Craig, Dalton, Lazenby, Moore]sorted=bonds.stream().sorted(Comparator.comparingInt(String::length)).collect(Collectors.toList());// [Moore, Craig, Dalton, Connery, Lazenby, Brosnan]sorted=bonds.stream().sorted(Comparator.comparingInt(String::length).thenComparing(Comparator.naturalOrder())).collect(Collectors.toList());// [Craig, Moore, Dalton, Brosnan, Connery, Lazenby]

The example shows how to use several static methods in Comparator to sort the list of actors who have played James Bond over the years.9 Comparators are discussed further in Recipe 4.1.

Static methods in interfaces remove the need to create separate utility classes, though that option is still available if a design calls for it.

The key points to remember are:

Static methods must have an implementation

You cannot override a static method

Call static methods from the interface name

You do not need to implement an interface to use its static methods

Static methods from interfaces are used throughout this book, but Recipe 4.1 covers the static methods from Comparator used here.

1 Coined by Gordon Moore, one of the co-founders of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, based on the observation that the number of transistors that could be packed into an integrated circuit doubled roughly every 18 months. See Wikipedia’s Moore’s law entry for details.

2 It is difficult to discuss lambdas or method references without discussing streams, which have their own chapter later. Suffice it to say that a stream produces a series of elements sequentially, does not store them anywhere, and does not modify the original source.

3 I mean no disrespect by treating Admiral Hopper as an object. I have no doubt she could still kick my butt, and she passed away in 1992.

4 At least until Java 9, when private methods are also allowed in interfaces. See Recipe 10.2 for details.

5 “A magnificent horse, with the brain of a bird.” (Disney’s Hercules movie, which is fun if you pretend you know nothing about Greek mythology and never heard of Hercules.)

6 This can be solved by using virtual inheritance, but still.

7 There’s an obscure reference for you, but Eiffel was one of the foundational languages of object-oriented programming. See Bertrand Meyer’s Object-Oriented Software Construction, Second Edition (Prentice Hall, 1997).

8 Predicate is one of the new functional interfaces in the java.util.function package, described in detail in Recipe 2.3.

9 The temptation to add Idris Elba to the list is almost overwhelming, but no such luck as yet.

The previous chapter discussed the basic syntax of lambda expressions and method references. One basic principle is that for either, there is always a context. Lambda expressions and method references are always assigned to functional interfaces, which provide information about the single abstract method being implemented.

While many interfaces in the Java standard library contain only a single, abstract method and are thus functional interfaces, there is a new package that is specifically designed to contain only functional interfaces that are reused in the rest of the library. That package is called java.util.function.

The interfaces in java.util.function fall into four categories: (1) consumers, (2) suppliers, (3) predicates, and (4) functions. Consumers take a generic argument and return nothing. Suppliers take no arguments and return a value. Predicates take an argument and return a boolean. Functions take a single argument and return a value.

For each of the basic interfaces, there are several related ones. For example, Consumer has variations customized for primitive types (IntConsumer, LongConsumer, and DoubleConsumer) and a variation (BiConsumer) that takes two arguments and returns void.

Although by definition the interfaces in this chapter only contain a single abstract method, most also include additional methods that are either static or default. Becoming familiar with these methods will make your job as a developer easier.

The java.util.function.Consumer interface has as its single, abstract method, void accept(T t). See Example 2-1.

voidaccept(Tt)defaultConsumer<T>andThen(Consumer<?superT>after)

The accept method takes a generic argument and returns void. One of the most frequently used examples of a method that takes a Consumer as an argument is the default forEach method in java.util.Iterable, shown in Example 2-2.

All linear collections implement this interface by performing the given action for each element of the collection, as in Example 2-3.

List<String>strings=Arrays.asList("this","is","a","list","of","strings");strings.forEach(newConsumer<String>(){@Overridepublicvoidaccept(Strings){System.out.println(s);}});strings.forEach(s->System.out.println(s));strings.forEach(System.out::println);

The lambda expression conforms to the signature of the accept method, because it takes a single argument and returns nothing. The println method in PrintStream, accessed here via System.out, is compatible with Consumer. Therefore, either can be used as the target for an argument of type Consumer.

The java.util.function package also contains primitive variations of Consumer<T>, as well as a two-argument version. See Table 2-1 for details.

| Interface | Single abstract method |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consumers are expected to operate via side effects, as shown in Recipe 2.3.

The BiConsumer interface has an accept method that takes two generic arguments, which are assumed to be of different types. The package contains three variations on BiConsumer where the second argument is a primitive. One is ObjIntConsumer, whose accept method takes two arguments, a generic and and an int. ObjLongConsumer and ObjDoubleConsumer are defined similarly.

Other uses of the Consumer interface in the standard library include:

Optional.ifPresent(Consumer<? super T> consumer)If a value is present, invoke the specified consumer. Otherwise do nothing.

Stream.forEach(Consumer<? super T> action)Performs an action for each element of the stream.1 The Stream.forEachOrdered method is similar, accessing elements in encounter order.

Stream.peek(Consumer<? super T> action)Returns a stream with the same elements as the existing stream, first performing the given action. This is a very useful technique for debugging (see Recipe 3.5 for an example).

The andThen method in Consumer is used for composition. Function composition is discussed further in Recipe 5.8. The peek method in Stream is examined in Recipe 3.5.

The java.util.function.Supplier interface is particularly simple. It does not have any static or default methods. It contains only a single, abstract method, T get().

Implementing Supplier means providing a method that takes no arguments and returns the generic type. As stated in the Javadocs, there is no requirement that a new or distinct result be returned each time the Supplier is invoked.

One simple example of a Supplier is the Math.random method, which takes no arguments and returns a double. That can be assigned to a Supplier reference and invoked at any time, as in Example 2-4.

Loggerlogger=Logger.getLogger("...");DoubleSupplierrandomSupplier=newDoubleSupplier(){@OverridepublicdoublegetAsDouble(){returnMath.random();}};randomSupplier=()->Math.random();randomSupplier=Math::random;logger.info(randomSupplier);

The single abstract method in DoubleSupplier is getAsDouble, which returns a double. The other associated Supplier interfaces in the java.util.function package are shown in Table 2-2.

| Interface | Single abstract method |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the primary use cases for Suppliers is to support the concept of deferred execution. The info method in java.util.logging.Logger takes a Supplier, whose get method is only called if the log level means the message will be seen (shown in detail in Recipe 5.7). This process of deferred execution can be used in your own code, to ensure that a value is retrieved from a Supplier only when appropriate.

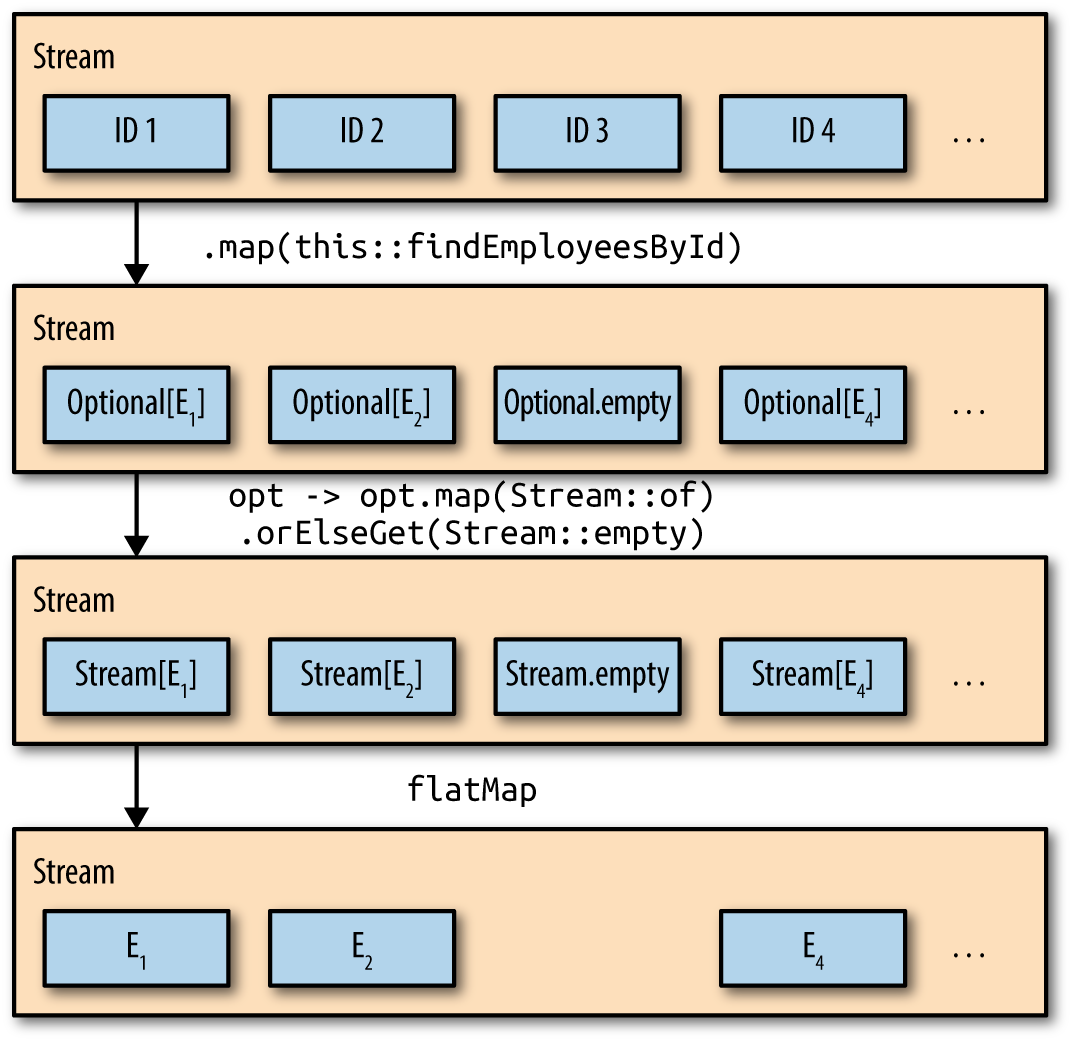

Another example from the standard library is the orElseGet method in Optional, which also takes a Supplier. The Optional class is discussed in Chapter 6, but the short explanation is that an Optional is a nonnull object that either wraps a value or is empty. It is typically returned by methods that may reasonably expect to have no result, like finding a value in an empty collection.

To see how that might work, consider searching for a name in a collection, as shown in Example 2-5.

List<String>names=Arrays.asList("Mal","Wash","Kaylee","Inara","Zoë","Jayne","Simon","River","Shepherd Book");Optional<String>first=names.stream().filter(name->name.startsWith("C")).findFirst();System.out.println(first);System.out.println(first.orElse("None"));System.out.println(first.orElse(String.format("No result found in %s",names.stream().collect(Collectors.joining(", ")))));System.out.println(first.orElseGet(()->String.format("No result found in %s",names.stream().collect(Collectors.joining(", ")))));

The findFirst method on Stream returns the first encountered element in an ordered stream.2 Since it’s possible to apply a filter so there are no elements remaining in the stream, the method returns an Optional. That Optional either contains the desired element, or is empty. In this case, none of the names in the list pass the filter, so the result is an empty Optional.

The orElse method on Optional returns either the contained element, or a specified default. That’s fine if the default is a simple string, but can be wasteful if processing is necessary to return a value.

In this case, the returned value shows the complete list of names in comma-separated form. The orElse method creates the complete string, whether the Optional contains a value or not.

The orElseGet method, however, takes a Supplier as an argument. The advantage is that the get method on the Supplier will only be invoked when the Optional is empty, so the complete name string is not formed unless it is necessary.

Other examples from the standard library that use Suppliers include:

The orElseThrow method in Optional, which takes a Supplier<X extends Exception>. The Supplier is only executed if an exception occurs.

Objects.requireNonNull(T obj, Supplier<String> messageSupplier) only customizes its response if the first argument is null.

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(Supplier<U> supplier) returns a CompletableFuture that is asynchronously completed by a task running with the value obtained by calling the given Supplier.

The Logger class has overloads for all its logging methods that takes a Supplier<String> rather than just a string (used as an example in Recipe 5.7).

Using the overloaded logging methods that take a Supplier is discussed in Recipe 5.7. Finding the first element in a collection is discussed in Recipe 3.9. Completable futures are part of several recipes in Chapter 9, and Optional is the topic of recipes in Chapter 6.

Implement the boolean test(T t) method in the Predicate interface using a lambda expression or a method reference.

Predicates are used primarily to filter streams. Given a stream of items, the filter method in java.util.stream.Stream takes a Predicate and returns a new stream that includes only the items that satisfy the given predicate.

The single abstract method in Predicate is boolean test(T t), which takes a single generic argument and returns true or false. The complete set of methods in Predicate, including state and defaults, is given in Example 2-6.

defaultPredicate<T>and(Predicate<?superT>other)static<T>Predicate<T>isEqual(ObjecttargetRef)defaultPredicate<T>negate()defaultPredicate<T>or(Predicate<?superT>other)booleantest(Tt)

Say you have a collection of names and you want to find all the instances that have a particular length. Example 2-7 shows an example of how to use stream processing to do so.

publicStringgetNamesOfLength(intlength,String...names){returnArrays.stream(names).filter(s->s.length()==length).collect(Collectors.joining(", "));}

Alternatively, perhaps you want only the names that start with a particular string, as in Example 2-8.

publicStringgetNamesStartingWith(Strings,String...names){returnArrays.stream(names).filter(str->str.startsWith(s)).collect(Collectors.joining(", "));}

These can be made more general by allowing the condition to be specified by the client. Example 2-9 shows a method to do that.

publicclassImplementPredicate{publicStringgetNamesSatisfyingCondition(Predicate<String>condition,String...names){returnArrays.stream(names).filter(condition).collect(Collectors.joining(", "));}}// ... other methods ...}

This is quite flexible, but it may be a bit much to expect the clients to write every predicate themselves. One option is to add constants to the class representing the most common cases, as in Example 2-10.

publicclassImplementPredicate{publicstaticfinalPredicate<String>LENGTH_FIVE=s->s.length()==5;publicstaticfinalPredicate<String>STARTS_WITH_S=s->s.startsWith("S");// ... rest as before ...}

The other advantage to supplying a predicate as an argument is that you can also use the default methods and, or, and negate to create a composite predicate from a series of individual elements.

The test case in Example 2-11 demonstrates all of these techniques.

importstaticfunctionpackage.ImplementPredicate.*;importstaticorg.junit.Assert.assertEquals;// ... other imports ...publicclassImplementPredicateTest{privateImplementPredicatedemo=newImplementPredicate();privateString[]names;@BeforepublicvoidsetUp(){names=Stream.of("Mal","Wash","Kaylee","Inara","Zoë","Jayne","Simon","River","Shepherd Book").sorted().toArray(String[]::new);}@TestpublicvoidgetNamesOfLength5()throwsException{assertEquals("Inara, Jayne, River, Simon",demo.getNamesOfLength(5,names));}@TestpublicvoidgetNamesStartingWithS()throwsException{assertEquals("Shepherd Book, Simon",demo.getNamesStartingWith("S",names));}@TestpublicvoidgetNamesSatisfyingCondition()throwsException{assertEquals("Inara, Jayne, River, Simon",demo.getNamesSatisfyingCondition(s->s.length()==5,names));assertEquals("Shepherd Book, Simon",demo.getNamesSatisfyingCondition(s->s.startsWith("S"),names));assertEquals("Inara, Jayne, River, Simon",demo.getNamesSatisfyingCondition(LENGTH_FIVE,names));assertEquals("Shepherd Book, Simon",demo.getNamesSatisfyingCondition(STARTS_WITH_S,names));}@TestpublicvoidcomposedPredicate()throwsException{assertEquals("Simon",demo.getNamesSatisfyingCondition(LENGTH_FIVE.and(STARTS_WITH_S),names));assertEquals("Inara, Jayne, River, Shepherd Book, Simon",demo.getNamesSatisfyingCondition(LENGTH_FIVE.or(STARTS_WITH_S),names));assertEquals("Kaylee, Mal, Shepherd Book, Wash, Zoë",demo.getNamesSatisfyingCondition(LENGTH_FIVE.negate(),names));}}

Other methods in the standard library that use predicates include:

Optional.filter(Predicate<? super T> predicate)If a value is present, and the value matches the given predicate, returns an Optional describing the value, otherwise returns an empty Optional.

Collection.removeIf(Predicate<? super E> filter)Removes all elements of this collection that satisfy the predicate.

Stream.allMatch(Predicate<? super T> predicate)Returns true if all elements of the stream satisfy the given predicate. The methods anyMatch and noneMatch work similarly.

Collectors.partitioningBy(Predicate<? super T> predicate)Returns a Collector that splits a stream into two categories: those that satisfy the predicate and those that do not.

Predicates are useful whenever a stream should only return certain elements. This recipe hopefully gives you an idea where and when that might be useful.

Closure composition is also discussed in Recipe 5.8. The allMatch, anyMatch, and noneMatch methods are discussed in Recipe 3.10. Partitioning and group by operations are discussed in Recipe 4.5.

Provide a lambda expression that implements the R apply(T t) method.

The functional interface java.util.function.Function contains the single abstract method apply, which is invoked to transform a generic input parameter of type T into a generic output value of type R. The methods in Function are shown in Example 2-12.

default<V>Function<T,V>andThen(Function<?superR,?extendsV>after)Rapply(Tt)default<V>Function<V,R>compose(Function<?superV,?extendsT>before)static<T>Function<T,T>identity()

The most common usage of Function is as an argument to the Stream.map method. For example, one way to transform a String into an integer would be to invoke the length method on each instance, as in Example 2-13.

List<String>names=Arrays.asList("Mal","Wash","Kaylee","Inara","Zoë","Jayne","Simon","River","Shepherd Book");List<Integer>nameLengths=names.stream().map(newFunction<String,Integer>(){@OverridepublicIntegerapply(Strings){returns.length();}}).collect(Collectors.toList());nameLengths=names.stream().map(s->s.length()).collect(Collectors.toList());nameLengths=names.stream().map(String::length).collect(Collectors.toList());System.out.printf("nameLengths = %s%n",nameLengths);// nameLengths == [3, 4, 6, 5, 3, 5, 5, 5, 13]

The complete list of primitive variations for both the input and the output generic types are shown in Table 2-3.

| Interface | Single abstract method |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The argument to the map method in Example 2-13 could have been a ToIntFunction, because the return type on the method is an int primitive. The Stream.mapToInt method takes a ToIntFunction as an argument, and mapToDouble and mapToLong are analogous. The return types on mapToInt, mapToDouble, and mapToLong are IntStream, DoubleStream, and LongStream, respectively.

What if the argument and return type are the same? The java.util.function package defines UnaryOperator for that. As you might expect, there are also interfaces called IntUnaryOperator, DoubleUnaryOperator, and LongUnaryOperator, where the input and output arguments are int, double, and long, respectively. An example of a UnaryOperator would be the reverse method in StringBuilder, because both the input type and the output type are strings.

The BiFunction interface is defined for two generic input types and one generic output type, all of which are assumed to be different. If all three are the same, the package includes the BinaryOperator interface. An example of a binary operator would be Math.max, because both inputs and the output are either int, double, float, or long. Of course, the interface also defines interfaces called IntBinaryOperator, DoubleBinaryOperator, and LongBinaryOperator for those situations.3

To complete the set, the package also has primitive variations of BiFunction, which are summarized in Table 2-4.

| Interface | Single abstract method |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

While the various Stream.map methods are the primary usages of Function, they do appear in other contexts. Among them are:

Map.computeIfAbsent(K key, Function<? super K,? extends V> mappingFunction)If the specified key does not have a value, use the provided Function to compute one and add it to a Map.

Comparator.comparing(Function<? super T,? extends U> keyExtractor)Discussed in Recipe 4.1, this method generates a Comparator that sorts a collection by the key generated from the given Function.

Comparator.thenComparing(Function<? super T,? extends U> keyExtractor)An instance method, also used in sorting, that adds an additional sorting mechanism if the collection has equal values by the first sort.

Functions are also used extensively in the Collectors utility class for grouping and downstream collectors.

The andThen and compose methods are discussed in Recipe 5.8. The identity method is simply the lambda expression e -> e. One usage is shown in Recipe 4.3.

See Recipe 5.8 for examples of the andThen and compose methods in the Function interface. See Recipe 4.3 for an example of Function.identity. See Recipe 4.6 for examples of using functions as downstream collectors. The computeIfAbsent method is discussed in Recipe 5.4. Binary operators are also covered in Recipe 3.3.

1 This is such a common operation that forEach was also added directly to Iterable. The Stream variation is useful when the source elements do not come from a collection, or if you want to make the stream parallel.

2 Streams may have an encounter order or they may not, just as lists are assumed to be ordered by index and sets are not. This can be different from the order in which elements are processed. See Recipe 3.9 for more information.

3 See Recipe 3.3 for more on BinaryOperator uses in the standard library.

Java 8 introduces a new streaming metaphor to support functional programming. A stream is a sequence of elements that does not save the elements or modify the original source. Functional programming in Java often involves generating a stream from some source of data, passing the elements through a series of intermediate operations (called a pipeline), and completing the process with a terminal expression.

Streams can only be used once. After a stream has passed through zero or more intermediate operations and reached a terminal operation, it is finished. To process the values again, you need to make a new stream.

Streams are also lazy. A stream will only process as much data as is necessary to reach the terminal condition. Recipe 3.13 shows this in action.

The recipes in this chapter demonstrate various typical stream operations.

Use the static factory methods in the Stream interface, or the stream methods on Iterable or Arrays.

The new java.util.stream.Stream interface in Java 8 provides several static methods for creating streams. Specifically, you can use the static methods Stream.of, Stream.iterate, and Stream.generate.

The Stream.of method takes a variable argument list of elements:

static<T>Stream<T>of(T...values)

The implementation of the of method in the standard library actually delegates to the stream method in the Arrays class, shown in Example 3-1.

@SafeVarargspublicstatic<T>Stream<T>of(T...values){returnArrays.stream(values);}

The @SafeVarargs annotation is part of Java generics. It comes up when you have an array as an argument, because it is possible to assign a typed array to an Object array and then violate type safety with an added element. The @SafeVarargs annotation tells the compiler that the developer promises not to do that. See Appendix A for additional details.

As a trivial example, see Example 3-2.

Since streams do not process any data until a terminal expression is reached, each of the examples in this recipe will add a terminal method like collect or forEach at the end.

Stringnames=Stream.of("Gomez","Morticia","Wednesday","Pugsley").collect(Collectors.joining(","));System.out.println(names);// prints Gomez,Morticia,Wednesday,Pugsley

The API also includes an overloaded of method that takes a single element T t. This method returns a singleton sequential stream containing a single element.

Speaking of the Arrays.stream method, Example 3-3 shows an example.

String[]munsters={"Herman","Lily","Eddie","Marilyn","Grandpa"};names=Arrays.stream(munsters).collect(Collectors.joining(","));System.out.println(names);// prints Herman,Lily,Eddie,Marilyn,Grandpa

Since you have to create an array ahead of time, this approach is less convenient, but works well for variable argument lists. The API includes overloads of Arrays.stream for arrays of int, long, and double, as well as the generic type used here.

Another static factory method in the Stream interface is iterate. The signature of the iterate method is:

static<T>Stream<T>iterate(Tseed,UnaryOperator<T>f)

According to the Javadocs, this method “returns an infinite (emphasis added) sequential ordered Stream produced by iterative application of a function f to an initial element seed.” Recall that a UnaryOperator is a function whose single input and output types are the same (discussed in Recipe 2.4). This is useful when you have a way to produce the next value of the stream from the current value, as in Example 3-4.

List<BigDecimal>nums=Stream.iterate(BigDecimal.ONE,n->n.add(BigDecimal.ONE)).limit(10).collect(Collectors.toList());System.out.println(nums);// prints [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]Stream.iterate(LocalDate.now(),ld->ld.plusDays(1L)).limit(10).forEach(System.out::println)// prints 10 days starting from today

The first example counts from one using BigDecimal instances. The second uses the new LocalDate class in java.time and adds one day to it repeatedly. Since the resulting streams are both unbounded, the intermediate operation limit is needed.

The other factory method in the Stream class is generate, whose signature is:

static<T>Stream<T>generate(Supplier<T>s)

This method produces a sequential, unordered stream by repeatedly invoking the Supplier. A simple example of a Supplier in the standard library (a method that takes no arguments but produces a return value) is the Math.random method, which is used in Example 3-5.

longcount=Stream.generate(Math::random).limit(10).forEach(System.out::println)

If you already have a collection, you can take advantage of the default method stream that has been added to the Collection interface, as in Example 3-6.1

List<String>bradyBunch=Arrays.asList("Greg","Marcia","Peter","Jan","Bobby","Cindy");names=bradyBunch.stream().collect(Collectors.joining(","));System.out.println(names);// prints Greg,Marcia,Peter,Jan,Bobby,Cindy

There are three child interfaces of Stream specifically for working with primitives: IntStream, LongStream, and DoubleStream. IntStream and LongStream each have two additional factory methods for creating streams, range and rangeClosed. The methods from IntStream and LongStream are:

staticIntStreamrange(intstartInclusive,intendExclusive)staticIntStreamrangeClosed(intstartInclusive,intendInclusive)staticLongStreamrange(longstartInclusive,longendExclusive)staticLongStreamrangeClosed(longstartInclusive,longendInclusive)

The arguments show the difference between the two: rangeClosed includes the end value, and range doesn’t. Each returns a sequential, ordered stream that starts at the first argument and increments by one after that. An example of each is shown in Example 3-7.

List<Integer>ints=IntStream.range(10,15).boxed().collect(Collectors.toList());System.out.println(ints);// prints [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]List<Long>longs=LongStream.rangeClosed(10,15).boxed().collect(Collectors.toList());System.out.println(longs);// prints [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

The only quirk in that example is the use of the boxed method to convert the int values to Integer instances, which is discussed further in Recipe 3.2.

To summarize, here are the methods to create streams:

Stream.of(T... values) and Stream.of(T t)

Arrays.stream(T[] array), with overloads for int[], double[], and long[]

Stream.iterate(T seed, UnaryOperator<T> f)