Chapter 5. The HTTP/2 Protocol

This chapter provides an overview of how HTTP/2 works at a low level, down to the frames on the wire and how they interact. It will help you understand many of the benefits (and problems) the protocol provides. By the end you should have enough information to get started with tuning and debugging your own h2 installations in order to get the most out of the protocol. For the brave who would like to go deeper into the protocol, perhaps for implementation purposes, RFC 75401 is an excellent place to start.

Layers of HTTP/2

HTTP/2 can be generalized into two parts: the framing layer, which is core to h2’s ability to multiplex, and the data or http layer, which contains the portion that is traditionally thought of as HTTP and its associated data. It is tempting to completely separate the two layers and think of them as totally independent things. Careful readers of the specification will note that there is a tension between the framing layer being a completely generic reusable construct, and being something that was designed to transport HTTP. For example, the specification starts out talking generically about endpoints and bidirectionality—something that would be perfect for many messaging applications—and then segues into talking about clients, servers, requests, and responses. When reading about the framing layer it is important to not lose sight of the fact that its purpose is to transport and communicate HTTP and nothing else.

Though the data layer is purposely designed to be backward compatible with HTTP/1.1, there are a number of aspects of h2 that will cause developers familiar with h1 and accustomed to reading the protocol on the wire to perform a double take:

- Binary protocol

-

The h2 framing layer is a binary framed protocol. This makes for easy parsing by machines but causes eye strain when read by humans.

- Header compression

-

As if a binary protocol were not enough, in h2 the headers are heavily compressed. This can have a dramatic effect on redundant bytes on the wire.

- Multiplexed

-

When looking at a connection that is transporting h2 in your favorite debugging tool, requests and responses will be interwoven with each other.

- Encrypted

-

To top it off, for the most part the data on the wire is encrypted, making reading on the fly more challenging.

The Connection

The base element of any HTTP/2 session is the connection. This is defined as a TCP/IP socket initiated by the client, the entity that will send the HTTP requests. This is no different than h1; however, unlike h1, which is completely stateless, h2 bundles connection-level elements that all of the frames and streams that run over it adhere to. These include connection-level settings and the header table (which are both described in more detail later in this chapter). This implies a certain amount of overhead in each h2 connection that does not exist in earlier versions of the protocol. The intent is that the benefits of that overhead far outweigh the costs.

In order to doubly confirm to the server that the client endpoint speaks h2, the client sends a magic octet stream called the connection preface as the first data over the connection. This is primarily intended for the case where a client has upgraded from HTTP/1.1 over clear text. This stream in hex is:

0x505249202a20485454502f322e300d0a0d0a534d0d0a0d0a

Decoded as ASCII you get:

PRI * HTTP/2.0\r\n\r\nSM\r\n\r\n

The point of this string is to cause an explicit error if by some chance the server (or some intermediary) did not end up being able to speak h2. The message is purposely formed to look like an h1 message. If a well-behaving h1 server receives this string, it will choke on the method (PRI) or the version (HTTP/2.0) and will return an error, allowing the h2 client to explicitly know something bad happened.

This magic string is then followed immediately by a SETTINGS frame. The server, to confirm its ability to speak h2, acknowledges the client’s SETTINGS frame and replies with a SETTINGS frame of its own (which is in turn acknowledged) and the world is considered good and h2 can start happening. Much work went into making certain this dance was as efficient as possible. Though it may seem on the surface that this is worryingly chatty, the client is allowed to start sending frames right away, assuming that the server’s SETTINGS frame is coming. If by chance the overly optimistic client receives something before the SETTINGS frame, the negotiation has failed and everyone gets to GOAWAY.

Frames

As mentioned before, HTTP/2 is a framed protocol. Framing is a method for wrapping all the important stuff in a way that makes it easy for consumers of the protocol to read, parse, and create. In contrast, h1 is not framed but is rather text delimited. Look at the following simple example:

GET / HTTP/1.1 <crlf> Host: www.example.com <crlf> Connection: keep-alive <crlf> Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9... <crlf> User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_11_4)... <crlf> Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, sdch <crlf> Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.8 <crlf> Cookie: pfy_cbc_lb=p-browse-w; customerZipCode=99912|N; ltc=%20;... <crlf> <crlf>

Parsing something like this is not rocket science but it tends to be slow and error prone. You need to keep reading bytes until you get to a delimiter, <crlf> in this case, while also accounting for all of the less spec-compliant clients that just send <lf>. A state machine looks something like this:

loop while( ! CRLF ) read bytes end while if first line parse line as the Request-Line else if line is empty break out of the loop # We are done else if line starts with non-whitespace parse the header line into a key/value pair else if line starts with space add the continuation header to the previous header end if end loop # Now go on to ready the request/response based on whatever was # in the Transfer-encoding header and deal with all of the vagaries # of browser bugs

Writing this code is very doable and has been done countless times. The problems with parsing an h1 request/response are:

-

You can only have one request/response on the wire at a time. You have to parse until done.

-

It is unclear how much memory the parsing will take. This leads to a host of questions: What buffer are you reading a line into? What happens if that line is too long? Should you grow and reallocate, or perhaps return a 400 error? These types of questions makes working in a memory efficient and fast manner challenging.

Frames, on the other hand, let the consumer know up front what they will be getting. Framed protocols in general, and h2 specifically, start with some known number of bytes that contain a length field for the overall size of the frame. Figure 5-1 shows what an HTTP/2 frame looks like.

Figure 5-1. HTTP/2 frame header

The first nine bytes (octets) are consistent for every frame. The consumer just needs to read those bytes and it knows precisely how many bytes to expect in the whole frame. See Table 5-1 for a description of each field.

| Name | Length | Description |

|---|---|---|

Length |

3 bytes |

Indicates the length of the frame payload (value in the range of 214 through 224-1 bytes). Note that 214 bytes is the default max frame size, and longer sizes must be requested in a SETTINGS frame. |

Type |

1 bytes |

What type of frame this is (see Table 5-2 for a description). |

Flags |

1 bytes |

Flags specific to the frame type. |

R |

1 bit |

A reserved bit. Do not set this. Doing so might have dire consequences. |

Stream Identifier |

31 bits |

A unique identifier for each stream. |

Frame Payload |

Variable |

The actual frame content. Its length is indicated in the Length field. |

Because everything is deterministic, the parsing logic is more like:

loop Read 9 bytes off the wire Length = the first three bytes Read the payload based on the length. Take the appropriate action based on the frame type. end loop

This is much simpler to write and maintain. It also has a second extremely significant advantage over h1’s delimited format: with h1 you need to send a complete request or response before you can send another. Because of h2’s framing, requests and responses can be interwoven, or multiplexed. Multiplexing helps get around problems such as head of line blocking, which was described in “Head of line blocking”.

There are 10 different frame types in the protocol. Table 5-2 provides a brief description, and you are welcome to jump to Appendix A if you’d like to learn more about each one.

| Name | ID | Description |

|---|---|---|

DATA |

0x0 |

Carries the core content for a stream |

HEADERS |

0x1 |

Contains the HTTP headers and, optionally, priorities |

PRIORITY |

0x2 |

Indicates or changes the stream priority and dependencies |

RST_STREAM |

0x3 |

Allows an endpoint to end a stream (generally an error case) |

SETTINGS |

0x4 |

Communicates connection-level parameters |

PUSH_PROMISE |

0x5 |

Indicates to a client that a server is about to send something |

PING |

0x6 |

Tests connectivity and measures round-trip time (RTT) |

GOAWAY |

0x7 |

Tells an endpoint that the peer is done accepting new streams |

WINDOW_UPDATE |

0x8 |

Communicates how many bytes an endpoint is willing to receive (used for flow control) |

CONTINUATION |

0x9 |

Used to extend HEADER blocks |

Streams

The HTTP/2 specification defines a stream as “an independent, bidirectional sequence of frames exchanged between the client and server within an HTTP/2 connection.” You can think of a stream as a series of frames making up an individual HTTP request/response pair on a connection. When a client wants to make a request it initiates a new stream. The server will then reply on that same stream. This is similar to the request/response flow of h1 with the important difference that because of the framing, multiple requests and responses can interleave together without one blocking another. The Stream Identifier (bytes 6–9 of the frame header) is what indicates which stream a frame belongs to.

After a client has established an h2 connection to the server, it starts a new stream by sending a HEADERS frame and potentially CONTINUATION frames if the headers need to span multiple frames (see “CONTINUATION Frames” for more on the CONTINUATIONS frame). This HEADERS frame generally contains the HTTP request or response, depending on the sender. Subsequent streams are initiated by sending a new HEADERS frame with an incremented Stream Identifier.

Messages

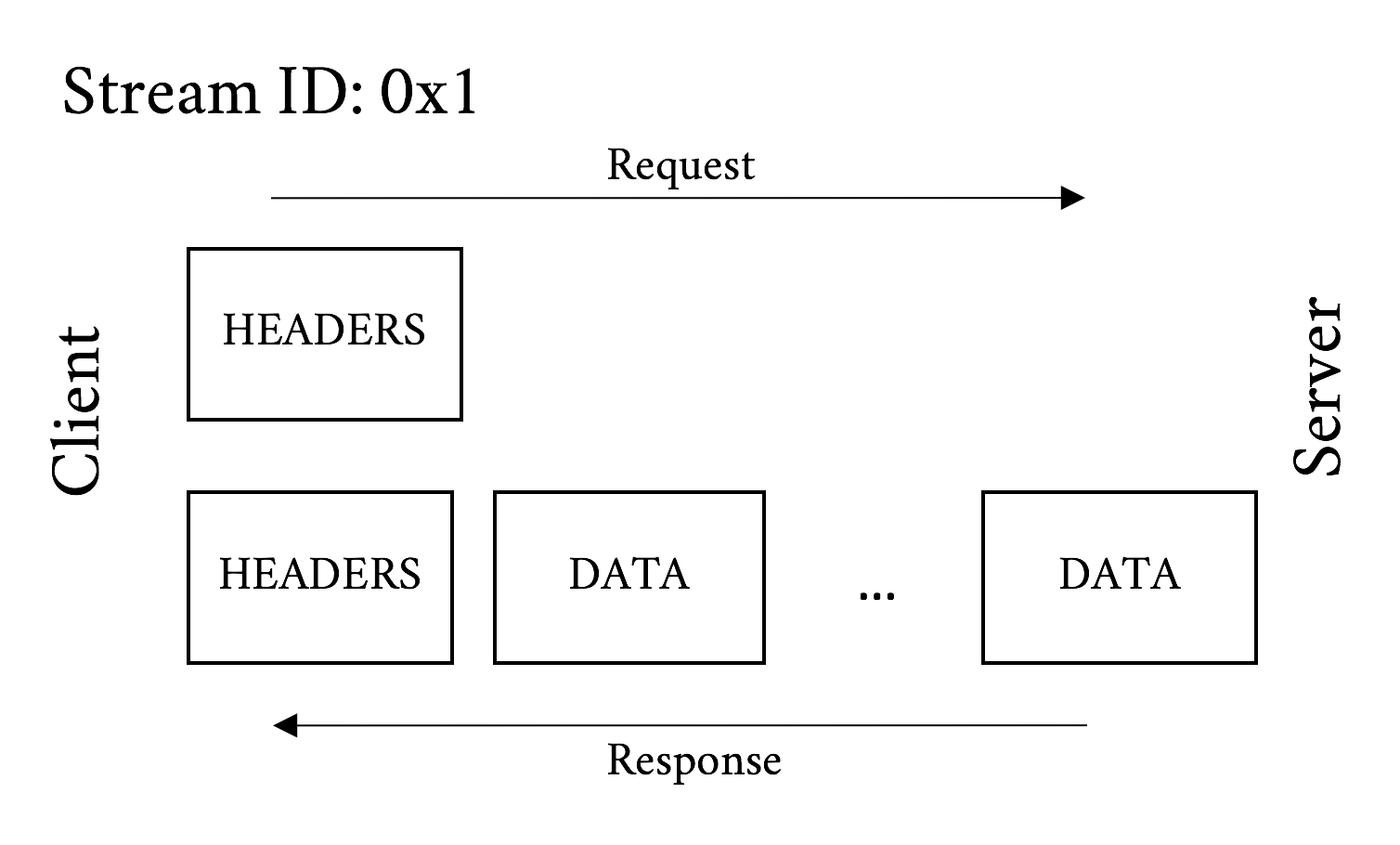

An HTTP message is a generic term for an HTTP request or response. As mentioned in the previous section, a stream is created to transport a pair of request/response messages. At a minimum a message consists of a HEADERS frame (which initiates the stream) and can additionally contain CONTINUATION and DATA frames, as well as additional HEADERS frames. Figure 5-2 is an example flow for a common GET request.

Figure 5-2. GET Request message and response message

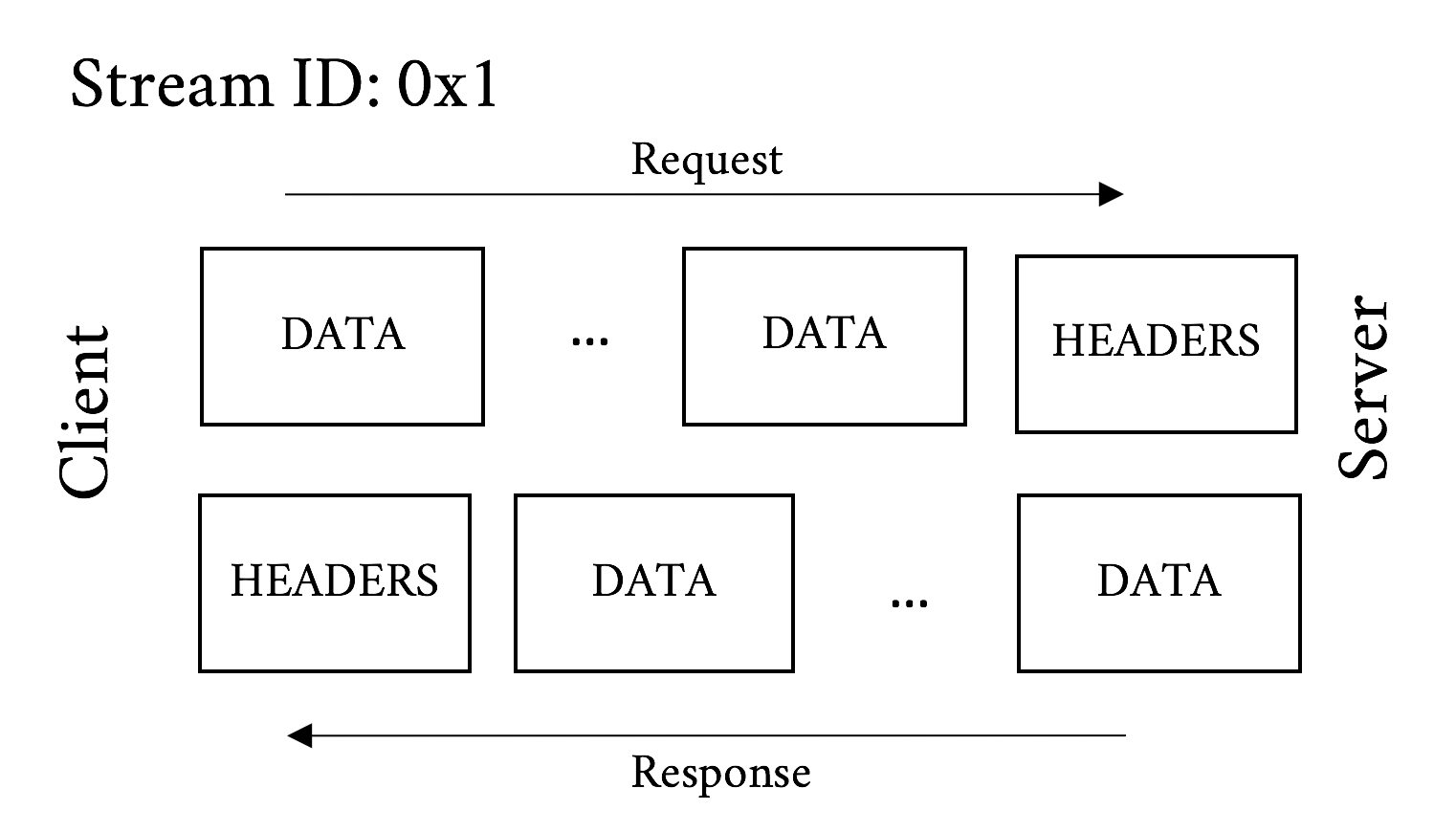

And Figure 5-3 illustrates what the frames may look like for a POST message. Remember that the big difference between a POST and a GET is that a POST commonly includes data sent from the client.

Figure 5-3. POST request message and response message

Just like h1 requests/responses are split into the message headers and the message body, an h2 request/response is split into HEADERS and DATA frames.

For reference, HTTP messages are defined in HTTP/1.1’s RFC 7230.3

Here are a few notable difference between HTTP/1 and HTTP/2 messages:

- Everything is a header

-

h1 split messages into request/status lines and headers. h2 did away with this distinction and rolled those lines into magic pseudo headers. For example, a sample request and response in HTTP/1.1 might look like:

GET / HTTP/1.1 Host: www.example.com User-agent: Next-Great-h2-browser-1.0.0 Accept-Encoding: compress, gzip HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-type: text/plain Content-length: 2 ...

And its HTTP/2 equivalent:

:scheme: https :method: GET :path: / :authority: www.example.com User-agent: Next-Great-h2-browser-1.0.0 Accept-Encoding: compress, gzip :status: 200 content-type: text/plain

Note how the request and status lines are split out into the

:scheme,:method,:path, and:statusheaders. Also note that this representation of the h2 headers is not what goes over the wire. Skip to “HEADERS Frame Fields” for a description of the HEADERS frame and “Header Compression (HPACK)” for more on that. - No chunked encoding

-

Who needs chunking in the world of frames? Chunking was used to piece out data to the peer without knowing the length ahead of time. With frames as part of the core protocol there is no need for it any longer.

- No more 101 responses

-

The Switching Protocols response is a corner case of h1. Its most common use today is probably for upgrading to a WebSocket connection. ALPN provides more explicit protocol negotiation paths with less round-trip overhead.

Flow Control

A new feature in h2 is stream flow control. Unlike h1 where the server will send data just about as fast as the client will consume it, h2 provides the ability for the client to pace the delivery. (And, as just about everything in h2 is symmetrical, the server can do the same thing.) Flow control information is indicated in WINDOW_UPDATE frames. Each frame tells the peer endpoint how many bytes the sender is willing to receive. As the endpoint receives and consumes sent data, it will send out a WINDOWS_UPDATE frame to indicate its updated ability to consume bytes. (Many an early HTTP/2 implementor spent a good deal of time debugging window updates to answer the “Why am I not getting data?” question.) It is the responsibility of the sender to honor these limits.

A client may want to use flow control for a variety of reasons. One very practical reason may be to make certain one stream does not choke out others. Or a client may have limited bandwidth or memory available and forcing the data to come down in manageable chunks will lead to efficiency gains. Though flow control cannot be turned off, setting the maximum value of 231–1 effectively disables it, at least for files under 2 GB in size. Another case to keep in mind is intermediaries. Very often content is delivered through a proxy or CDN that terminated the HTTP connections. Because the different sides of the proxy could have different throughput capabilities, flow control allows a proxy to keep the two sides closely in sync to minimize the need for overly taxing proxy resources.

Priority

The last important characteristic of streams is dependencies. Modern browsers are very careful to ask for the most important elements on a web page first, which improves performance by fetching objects in an optimal order. Once it has the HTML in hand, the browser generally needs things like cascading style sheets (CSS) and critical JavaScript before it can start painting the screen. Without multiplexing, it needs to wait for a response to complete before it can ask for a new object. With h2, the client can send all of its requests for resources at the same time and a server can start working on those requests right away. The problem with that is the browser loses the implicit priority scheme that it had in h1. If the server receives a hundred requests for objects at the same time, with no indication of what is more important, it will send everything more or less simultaneously and the less important elements will get in the way of the critical elements.

HTTP/2 addresses this through stream dependencies. Using HEADERS and PRIORITY frames, the client can clearly communicate what it needs and the suggested order in which they are needed. It does this by declaring a dependency tree and the relative weights inside that tree:

-

Dependencies provide a way for the client to tell the server that the delivery of a particular object (or objects) should be prioritized by indicating that other objects are dependent on it.

-

Weights let the client tell the server how to prioritize objects that have a common dependency.

Take this simple website as an example:

-

index.html

-

header.jpg

-

critical.js

-

less_critical.js

-

style.css

-

ad.js

-

photo.jpg

-

After receiving the base HTML file, the client could parse it and create a dependency tree, and assign weights to the elements in the tree. In this case the tree might look like:

-

index.html

-

style.css

-

critical.js

-

less_critical.js (weight 20)

-

photo.jpg (weight 8)

-

header.jpg (weight 8)

-

ad.js (weight 4)

-

-

-

In this dependency tree, the client is communicating that it wants style.css before anything else, then critical.js. Without these two files, it can’t make any forward progress toward rendering the web page. Once it has critical.js, it provides the relative weights to give the remaining objects. The weights indicate the relative amount of “effort” that should be expended serving an object. In this case less_critical.js has a weight of 20 relative to a total of 40 for all weights. This means the server should spend about half of its time and/or resources working on delivering less_critical.js compared to the other three objects. A well-behaved server will do what it can to make certain the client gets those objects as quickly as possible. In the end, what to do and how to honor priorities is up to the server. It retains the ability to do what it thinks is best. Intelligently dealing with priorities will likely be a major distinguishing performance factor between h2-capable web servers.

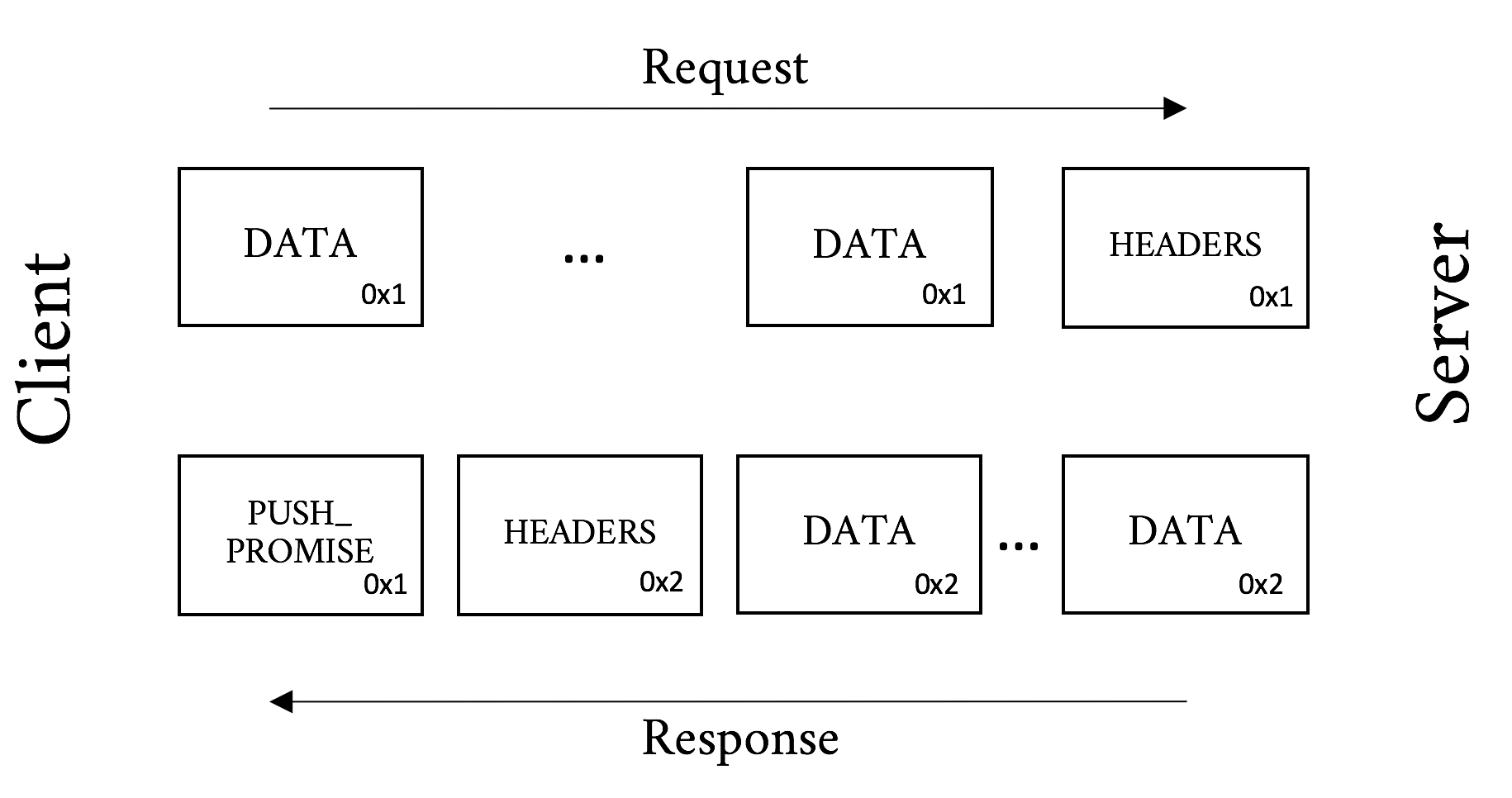

Server Push

The best way to improve performance for a particular object is to have it positioned in the browser’s cache before it is even asked for. This is the goal of HTTP/2’s Server Push feature. Push gives the server the ability to send an object to a client proactively, presumably because it knows that it will be needed at a near future date. Allowing a server to arbitrarily send objects down to a client could cause problems, including performance and security issues, so it is not just a matter of doing it, but also a matter of doing it well.

Pushing an Object

When the server decides it wants to push an object (referred to as “pushing a response” in the RFC), it constructs a PUSH_PROMISE frame. There are a number of important attributes to this frame:

-

The stream ID in the PUSH_PROMISE frame header is the stream ID of the request that the response is associated with. A pushed response is always related to a request the client has already sent. For example, if a browser asks for a base HTML page, a server would construct a PUSH_PROMISE on that request’s stream ID for a JavaScript object on that page.

-

The PUSH_PROMISE frame has a header block that resembles what the client would send if it were to request the object itself. This gives the client a chance to sanity check what is about to be sent.

-

The object that is being sent must be considered cacheable.

-

The

:methodheader field must be considered safe. Safe methods are those that are idempotent, which is a fancy way of saying ones that do not change any state. For example, a GET request is considered idempotent as it is (usually) just fetching an object, while a POST request is considered nonidempotent because it may change state on the server side. -

Ideally the PUSH_PROMISE should be sent down to the client before the client receives the DATA frames that might refer to the pushed object. If the server were to send the full HTML down before the PUSH_PROMISE is sent, for example, the client might have already sent a request for the object before the PUSH_PROMISE is received. The h2 protocol is robust enough to deal with this situation gracefully, but there is wasted effort and opportunity.

-

The PUSH_PROMISE frame will indicate what Stream Identifier the future sent response will be on.

Note

When a client chooses Stream Identifiers, it starts with 1 and then increments by two for each new stream, thus using only odd numbers. When a server initiates a new stream indicated in a PUSH_PROMISE it starts with 2 and sticks to even numbers. This avoids a race condition between the client and server on stream IDs and makes it easy to tell what objects were pushed. Stream 0 is reserved for overall connection-level control messages and cannot be used for new streams.

If a client is unsatisfied with any of the preceding elements of a PUSH_PROMISE, it can reset the new stream (with an RST_STREAM) or send a PROTOCOL_ERROR (in a GOAWAY frame), depending on the reason for the refusal. A common case could be that it already has the object in cache. The error responses are reserved for protocol-level problems with the PUSH_PROMISE such as unsafe methods or sending a push when the client has indicated that it would not accept push in a SETTINGS frame. It is worth noting that the server can start the stream right after the promise is sent, so canceling an in-flight push still may result in a good deal of the resource being sent. Pushing the right things and only the right things is an important performance feature.

Assuming the client does not refuse the push, the server will go ahead and send the object on the new stream identifier indicated in the PUSH_PROMISE (Figure 5-4).

Figure 5-4. Server Push message processing

Choosing What to Push

Depending on the application, deciding what to push may be trivial or extraordinarily complex. Take a simple HTML page, for example. When a server gets a request for the page, it needs to decide if it is going to push the objects on that page or wait for the client to ask for them. The decision-making process should take into account:

-

The odds of the object already being in the browser’s cache

-

The assumed priority of the object from the client’s point of view (see “Priority”)

-

The available bandwidth and similar resources that might have an effect on the client’s ability to receive a push

If the server chooses correctly it can really help the performance of the overall page, but a poor decision can have the opposite effect. This is probably why general-purpose push solutions are relatively uncommon today, even though SPDY introduced the feature over five years ago.

A more specialized case such as an API or an application communicating over h2 might have a much easier time deciding what will be needed in the very near future and what the client does not have cached. Think of a server streaming updates to a native application. These are areas that will see the most benefit from push in the near term.

Header Compression (HPACK)

As mentioned in “Fat message headers”, the average web page requires around 140 requests and the median size of an HTTP request is 460 bytes, totaling 63 KB of requests. That can cause quite the delay in the best of circumstances, but when you think about a congested WiFi or a poor cellular connection, things can get downright painful. The real crime is that between those requests there are generally very few new and unique bytes. They are screaming out for some type of compression.

It was known from the start that header compression would be a key element of HTTP/2. But how should they be compressed? The browser world was just recovering from from the CRIME vulnerability in SPDY, which leveraged the deflate header compression in a creative way to decrypt the early encrypted frames, so that approach was out. There was a need for a CRIME-proof mechanism that would have similar compression ability as GZIP.

After much innovative deliberation, HPACK was proposed. HPACK is a table lookup compression scheme that leverages Huffman encoding to get compression rates that approach GZIP. The best way to understand how HPACK works is probably with a simplified example.

Warning

Why not just use GZIP for header compression instead of HPACK? It would be a lot less work, for certain. Unfortunately the CRIME attack showed that it would also be vulnerable leakage of encrypted information. CRIME works by the attackers adding data to a request and then observing whether the resultant compressed and encrypted payload is smaller. If it is smaller they know that their inserted text overlaps with something else in the request such as a secret session cookie. In a relatively small amount of time the entire secret payload can be extracted in this manner. Thus, off-the-shelf compression schemes were out, and HPACK was invented.

Downloading a web page and its dependent objects involves many requests. This number commonly reaches into the hundreds for a single web page. These requests tend to be extremely similar. Take, for example, the following two requests. They are two requests that are likely to follow one another in a browser session requesting a full web page. The few unique bytes are emphasized in bold.

Request #1:

:authority: www.akamai.com :method: GET :path: / :scheme: https accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml accept-language: en-US,en;q=0.8 cookie: last_page=286A7F3DE upgrade-insecure-requests: 1 user-agent: Awesome H2/1.0

Request #2:

:authority: www.akamai.com :method: GET :path: /style.css :scheme: https accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml accept-language: en-US,en;q=0.8 cookie: last_page=*398AB8E8F upgrade-insecure-requests: 1 user-agent: Awesome H2/1.0

You can see that much of the latter request is a repeat of the former. The first request is about 220 bytes, and the second about 230. But only 36 bytes are unique. Just sending those 36 bytes will mean roughly an 85% savings in bytes sent. At a high level that is how HPACK works.

The following is a contrived and simplified example to help explain what HPACK is doing. The reality is much more of a stark, dystopian landscape, and if you’re curious to learn more, you should read RFC 7541, “HPACK: Header Compression for HTTP/2.”4

Let’s assume a client sends the following headers, in order:

Header1: foo Header2: bar Header3: bat

When the client sends the request, it can indicate in the header block that a particular header and its value should be indexed. It would create a table like:

| Index | Name | Value |

|---|---|---|

62 |

Header1 |

foo |

63 |

Header2 |

bar |

64 |

Header3 |

bat |

On the server side, when it reads the headers it would create the same table. On the next request when the client sends the request, if it sends the same headers it can simply send a header block like:

62 63 64

which the server will then look up and expand into the full headers that those indexes represent.

One of the major implications of this is that each connection is maintaining state, something that was nonexistent at the protocol level for h1.

The reality of HPACK is much more complicated. Here are a few tidbits for the curious:

-

There are actually two tables maintained on each side of a request or response. One is a dynamic table created in a manner similar to the preceding example. One is a static table made up of the 61 most common header names and value combinations. For example,

:method: GETis in the static table at index 2. The static table is defined to be 61 entries long, hence why the example started at 62. -

There are a number of controls on how items are indexed. These include:

-

Send literal values and indexes (as in the preceding example)

-

Send literal values and do not index them (for one-off or sensitive headers)

-

Send an indexed header name with a literal value and do not index it (for things like

:path: /foo.htmlwhere the value is always changing) -

Send an indexed header and value (as in the second request of the previous example)

-

-

It uses integer compression with a packing scheme for extreme space efficiency.

-

Leverages Huffman coding table for further compression of string literals.

Experiments show that HPACK works very well, especially on sites with large repeated headers (think: cookies). Since the bulk of the headers that are sent from request to request to a particular website are duplicated, HPACK’s table lookup mechanisms effectively eliminate those duplicate bytes from the communication.

On the Wire

Let’s look at an hHTTP/2 request and response and break it down. Note again, though we are spelling them out in text here for easy visual consumption, h2 on the wire is in a binary format and is compressed.

A Simple GET

The GET is the workhorse of HTTP. Semantically simple, it does what it says. It gets a resource from a server. Take, for instance, Example 5-1, a request to akamai.com (lines are truncated for clarity).

Example 5-1. HTTP/2 GET request

:authority: www.akamai.com :method: GET :path: / :scheme: https accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,... accept-language: en-US,en;q=0.8 cookie: sidebar_collapsed=0; _mkto_trk=... upgrade-insecure-requests: 1 user-agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh;...

This request asks for the index page from www.akamai.com over HTTPS using the GET method. Example 5-2 shows the response.

Note

The :authority header’s name may seem odd. Why not :host? The reason for this is that it is analogous to the Authority section of the URI and not the HTTP/1.1 Host header. The Authority section includes the host and optionally the port, and thus fills the role of the Host header quite nicely. For the few of you who jumped to and read the URI RFC,5 the User Information section of the Authority (i.e., the username and password) is explicitly forbidden in h2.

Example 5-2. HTTP/2 GET response (headers only)

:status: 200 cache-control: max-age=600 content-encoding: gzip content-type: text/html;charset=UTF-8 date: Tue, 31 May 2016 23:38:47 GMT etag: "08c024491eb772547850bf157abb6c430-gzip" expires: Tue, 31 May 2016 23:48:47 GMT link: <https://c.go-mpulse.net>;rel=preconnect set-cookie: ak_bmsc=8DEA673F92AC... vary: Accept-Encoding, User-Agent x-akamai-transformed: 9c 237807 0 pmb=mRUM,1 x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN <DATA Frames follow here>

In this response the server is saying that the request was successful (200 status code), sets a cookie (cookie header), indicates that the content is gzipped (content-encoding header), as well as a host of other important bits of information used behind the scenes.

Now let’s take our first look at what goes over the wire for a simple GET. Using Tatsuhiro Tsujikawa’s excellent nghttp tool,6 we can get a verbose output to see all the living details of h2:

$ nghttp -v -n --no-dep -w 14 -a -H "Header1: Foo" https://www.akamai.com

This command line sets the window size to 16 KB (214), adds an arbitrary header, and asks to download a few key assets from the page. The following section shows the annotated output of this command:

[ 0.047] Connected The negotiated protocol: h2[ 0.164] send SETTINGS frame <length=12, flags=0x00, stream_id=0>

(niv=2) [SETTINGS_MAX_CONCURRENT_STREAMS(0x03):100] [SETTINGS_INITIAL_WINDOW_SIZE(0x04):16383]

Here you see that nghttp:

Successfully negotiated h2

As per spec, sent a SETTINGS frame right away

Set the window size to 16 KB as requested in the command line

Note the use of stream_id 0 for the connection-level information. (You do not see the connection preface in the output but it was sent before the SETTINGS frame.)

Continuing with the output:

[ 0.164] send HEADERS frame <length=45, flags=0x05, stream_id=1>

; END_STREAM | END_HEADERS  (padlen=0)

; Open new stream

:method: GET

:path: /

:scheme: https

:authority: www.akamai.com

accept: */*

accept-encoding: gzip, deflate

user-agent: nghttp2/1.9.2

header1: Foo

(padlen=0)

; Open new stream

:method: GET

:path: /

:scheme: https

:authority: www.akamai.com

accept: */*

accept-encoding: gzip, deflate

user-agent: nghttp2/1.9.2

header1: Foo

This shows the header block for the request.

Note the client (nghttp) sent the END_HEADERS and END_STREAM flags. This tells the server that there are no more headers coming and to expect no data. Had this been a POST, for example, the END_STREAM flag would not have been sent at this time.

This is the header we added on the

nghttpcommand line.

[ 0.171] recv SETTINGS frame <length=30, flags=0x00, stream_id=0>(niv=5) [SETTINGS_HEADER_TABLE_SIZE(0x01):4096] [SETTINGS_MAX_CONCURRENT_STREAMS(0x03):100] [SETTINGS_INITIAL_WINDOW_SIZE(0x04):65535] [SETTINGS_MAX_FRAME_SIZE(0x05):16384] [SETTINGS_MAX_HEADER_LIST_SIZE(0x06):16384] [ 0.171] send SETTINGS frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=0>

; ACK (niv=0) [ 0.197] recv SETTINGS frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=0> ; ACK (niv=0)

Ngttpd received the server’s SETTINGS frame.

Sent and received acknowledgment of the SETTINGS frames.

[ 0.278] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) :status: 200

[ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) last-modified: Wed, 01 Jun 2016 ... [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) content-type: text/html;charset=UTF-8 [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) etag: "0265cc232654508d14d13deb...gzip" [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) vary: Accept-Encoding, User-Agent [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) x-akamai-transformed: 9 - 0 pmb=mRUM,1 [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) content-encoding: gzip [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) expires: Wed, 01 Jun 2016 22:01:01 GMT [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) date: Wed, 01 Jun 2016 22:01:01 GMT [ 0.279] recv (stream_id=1, sensitive) set-cookie: ak_bmsc=70A833EB... [ 0.279] recv HEADERS frame <length=458, flags=0x04, stream_id=1>

; END_HEADERS (padlen=0) ; First response header

Here we have the response headers from the server.

The

stream_idof 1 indicates which request it is associated with (we have only sent one request, but life is not always that simple).

Nghttpd got a 200 status code from the server. Success!

Note that this time the END_STREAM was not sent because there is DATA to come.

[ 0.346] recv DATA frame <length=2771, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>[ 0.346] recv DATA frame <length=4072, flags=0x00, stream_id=1> [ 0.346] recv DATA frame <length=4072, flags=0x00, stream_id=1> [ 0.348] recv DATA frame <length=4072, flags=0x00, stream_id=1> [ 0.348] recv DATA frame <length=1396, flags=0x00, stream_id=1> [ 0.348] send WINDOW_UPDATE frame <length=4, flags=0x00, stream_id=1> (window_size_increment=10915)

At last we got the data for the stream. You see five DATA frames come down followed by a WINDOW_UPDATE frame. The client indicated to the server that it consumed 10,915 bytes of the DATA frames and is ready for more data. Note that this stream is not done yet. But the client has work to do and thanks to multiplexing it can get to it.

[ 0.348] send HEADERS frame <length=39, flags=0x25, stream_id=15>:path: /styles/screen.1462424759000.css [ 0.348] send HEADERS frame <length=31, flags=0x25, stream_id=17> :path: /styles/fonts--full.css [ 0.348] send HEADERS frame <length=45, flags=0x25, stream_id=19> :path: /images/favicons/favicon.ico?v=XBBK2PxW74

Now that the client has some of the base HTML, it can start asking for objects on the page. Here you see three new streams created, IDs 15, 17, and 19 for stylesheet files and a favicon. (Frames were skipped and abbreviated for clarity.)

[ 0.378] recv DATA frame <length=2676, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.378] recv DATA frame <length=4072, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.378] recv DATA frame <length=1445, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.378] send WINDOW_UPDATE frame <length=4, flags=0x00, stream_id=13>

(window_size_increment=12216)

[ 0.379] recv HEADERS frame <length=164, flags=0x04, stream_id=17>  [ 0.379] recv DATA frame <length=175, flags=0x00, stream_id=17>

[ 0.379] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=17>

; END_STREAM

[ 0.380] recv DATA frame <length=2627, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.380] recv DATA frame <length=95, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.385] recv HEADERS frame <length=170, flags=0x04, stream_id=19>

[ 0.379] recv DATA frame <length=175, flags=0x00, stream_id=17>

[ 0.379] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=17>

; END_STREAM

[ 0.380] recv DATA frame <length=2627, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.380] recv DATA frame <length=95, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.385] recv HEADERS frame <length=170, flags=0x04, stream_id=19>  [ 0.387] recv DATA frame <length=1615, flags=0x00, stream_id=19>

[ 0.387] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=19>

; END_STREAM

[ 0.389] recv HEADERS frame <length=166, flags=0x04, stream_id=15>

[ 0.387] recv DATA frame <length=1615, flags=0x00, stream_id=19>

[ 0.387] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=19>

; END_STREAM

[ 0.389] recv HEADERS frame <length=166, flags=0x04, stream_id=15>  [ 0.390] recv DATA frame <length=2954, flags=0x00, stream_id=15>

[ 0.390] recv DATA frame <length=1213, flags=0x00, stream_id=15>

[ 0.390] send WINDOW_UPDATE frame <length=4, flags=0x00, stream_id=0>

(window_size_increment=36114)

[ 0.390] send WINDOW_UPDATE frame <length=4, flags=0x00, stream_id=15>

[ 0.390] recv DATA frame <length=2954, flags=0x00, stream_id=15>

[ 0.390] recv DATA frame <length=1213, flags=0x00, stream_id=15>

[ 0.390] send WINDOW_UPDATE frame <length=4, flags=0x00, stream_id=0>

(window_size_increment=36114)

[ 0.390] send WINDOW_UPDATE frame <length=4, flags=0x00, stream_id=15>  (window_size_increment=11098)

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=3977, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=4072, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=1589, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

(window_size_increment=11098)

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=3977, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=4072, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=1589, flags=0x00, stream_id=1>  [ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=1>

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=15>

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=1>

[ 0.410] recv DATA frame <length=0, flags=0x01, stream_id=15>

Here we see the overlapping streams coming down.

You can see the HEADERS frames for streams 15, 17, and 19.

You can see the HEADERS frames for streams 15, 17, and 19.

You see the various window updates, including a connection-level update for stream 0.

You see the various window updates, including a connection-level update for stream 0.

The last DATA frame for stream 1.

The last DATA frame for stream 1.

[ 0.457] send GOAWAY frame <length=8, flags=0x00, stream_id=0>

(last_stream_id=0, error_code=NO_ERROR(0x00), opaque_data(0)=[])

Finally we get the GOAWAY frame. Ironically this is the polite way to tear down the connection.

The flow may seem cryptic at first, but walk through it a few times. Everything logically follows the spec and has a specific purpose. In this straightforward example you can see many of the elements that make up h2, including flow control, multiplexing, and connection settings. Try the nghttp tool yourself against a few h2-enabled sites and see if you can follow those flows as well. Once it starts to make sense you will be well on your way to understanding the protocol.

Summary

The HTTP/2 protocol was many years in development and is full of design ideas, decisions, innovations, and compromises. This chapter has provided the basics for being able to look at a Wireshark dump (see “Wireshark”) of h2 and understand what is going on, and even find potential problems in your site’s use of the protocol (constantly changing cookie, perhaps?). For those who would like to go deeper, the ultimate resource is the RFC 7540 itself.7 It will provide every detail needed for the implementor, debugger, or masochist that lurks inside you.