Chapter 3. How and Why We Hack the Web

Using a (relatively) ancient protocol to deliver fast modern web pages has become a virtual act of acrobatics. An entire specialty of web performance engineer has built up around it. One could argue that O’Reilly’s Velocity conference series was born in part from people wanting to share their various tricks and hacks to get the most out of the venerable protocol. To understand where we are going (namely, toward HTTP/2), it is important to understand where we are, the challenges we face, and how we are dealing with them today.

Performance Challenges Today

Delivering a modern web page or web application is far from a trivial affair. With hundreds of objects per page, tens of domains, variability in the networks, and a wide range of device abilities, creating a consistent and fast web experience is a challenge. Understanding the steps involved in web page retrieval and rendering, as well as the challenges faced in those steps, is an important factor in creating something that does not get in the way of users interacting with your site. It also provides you with the insight needed to understand the motivations behind HTTP/2 and will allow you to evaluate the relative merits of its features.

The Anatomy of a Web Page Request

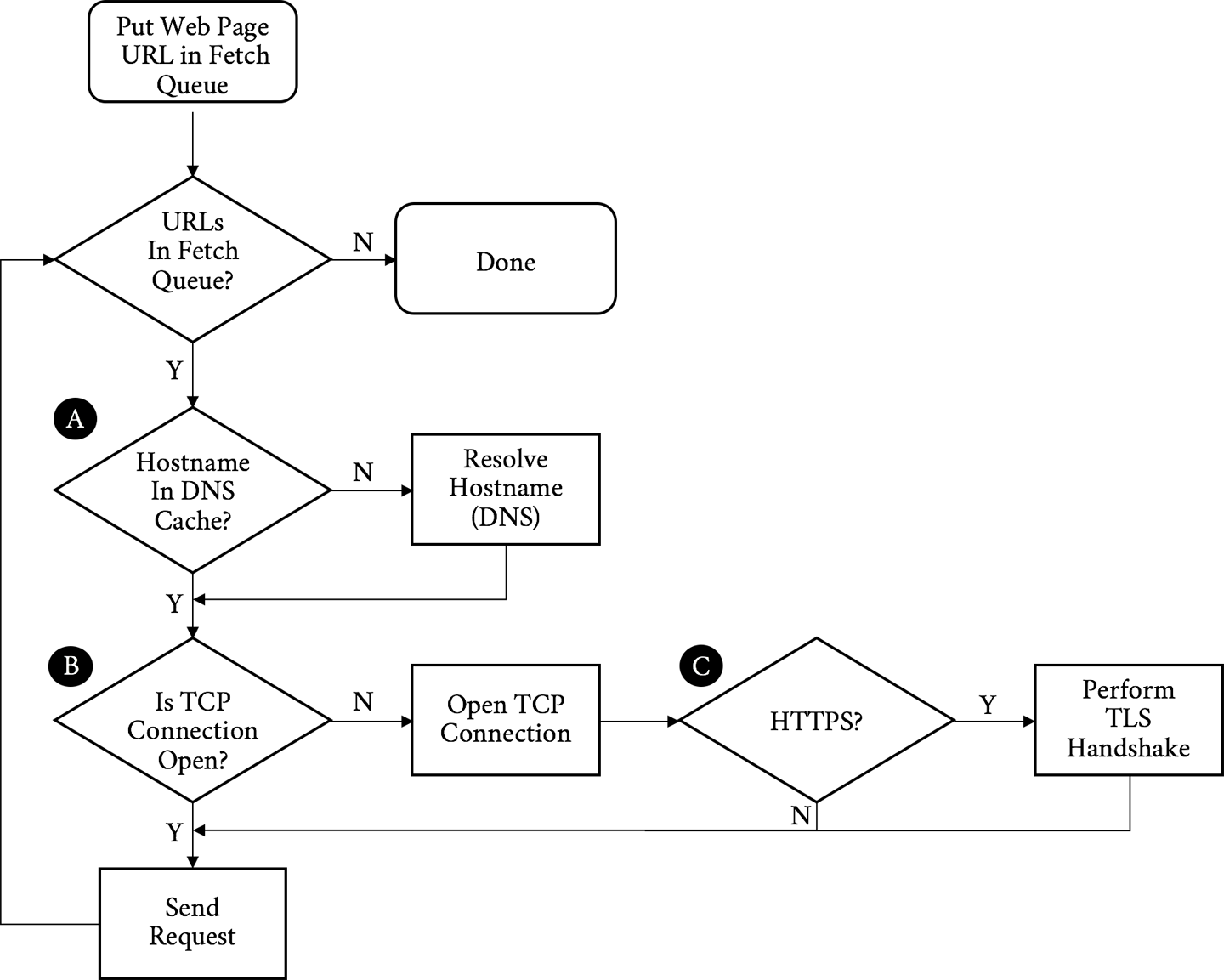

Before we dig in, it is important to have a baseline understanding of what we are trying to optimize; specifically, what goes on in the time between when users click a link in a web browser and the page being displayed on their screen. When a browser requests a web page, it goes through a repetitive process to get all of the information it needs to paint the page on the screen. It is easiest to think of this in two parts: the object fetching logic, and the page parsing/rendering logic. Let’s start with fetching. Figure 3-1 shows the components of this process.

Figure 3-1. Object request/fetching flowchart

Walking through the flowchart, we:

-

Put the URL to fetch in the queue

-

Resolve the IP address of the hostname in the URL (A)

-

Open a TCP connection to the host (B)

-

If it is an HTTPS request, initiate and finish a TLS handshake (C)

-

Send the request for the base page URL

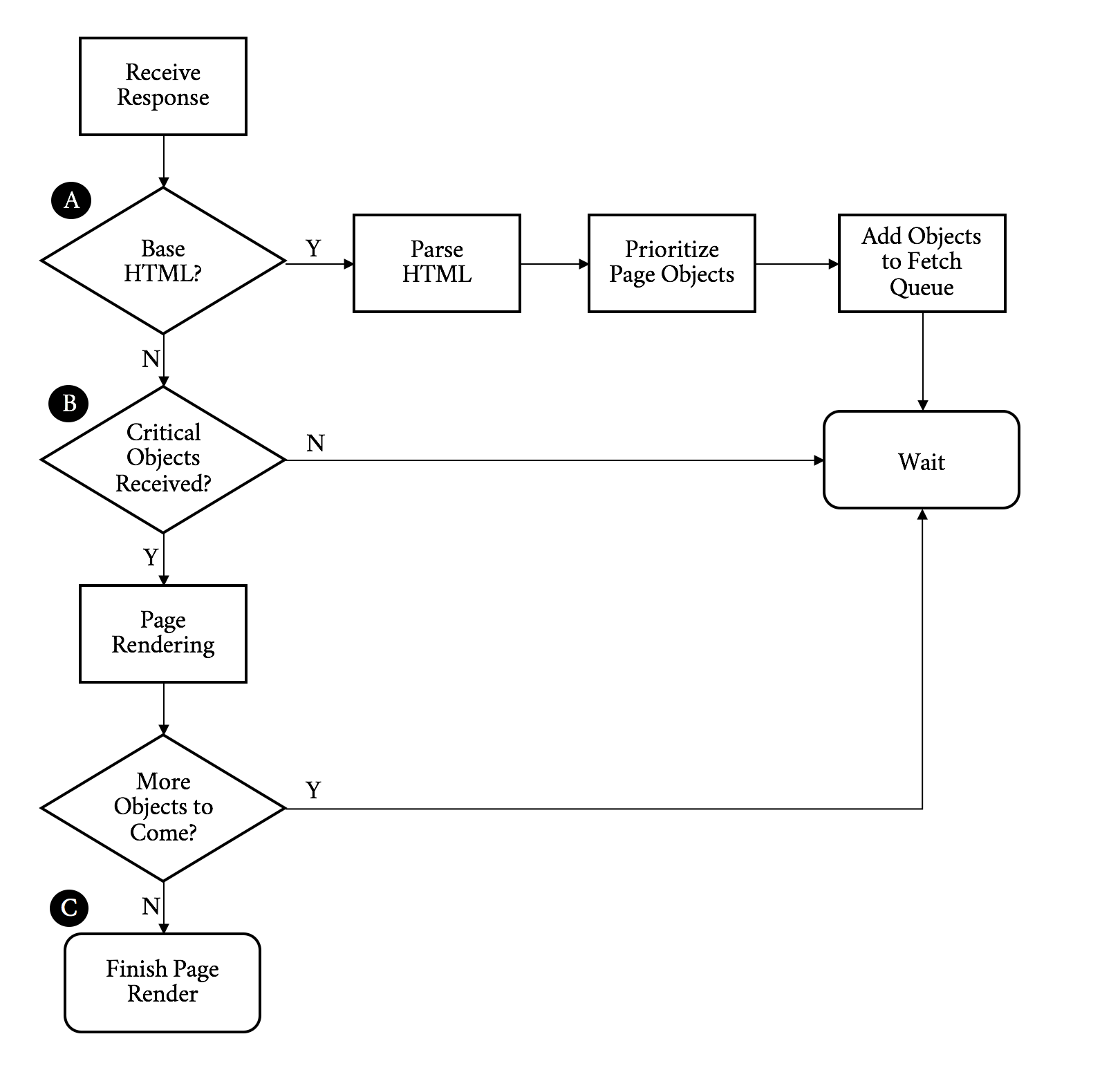

Figure 3-2 describes receiving the response and rendering the page.

Figure 3-2. Object response/page rendering flowchart

Continuing on with our walk through the flowchart, we:

-

Receive the response

-

If this is the base HTML, parse it and trigger prioritized fetches for the objects on the page (A)

-

If the critical objects on a page have been received, start rendering (B)

-

As additional objects are received, continue to parse and render until done (C)

The preceding process needs to be repeated for every page click. It puts a strain on the network and device resources. Working to optimize or eliminate any of these steps is core to the art of web performance tuning.

Critical Performance

With the previous diagrams we can call out the areas that matter for web performance and where our challenges may start. Let’s start with the network-level metrics that have an overall effect on the loading of a web page:

- Latency

-

The latency is how long it takes for an IP packet to get from one point to another. Related is the Round-Trip Time (RTT), which is twice the latency. Latency is a major bottleneck to performance, especially for protocols such as HTTP, which tend to make many round-trips to the server.

- Bandwidth

-

A connection between two points can only handle so much data at one time before it is saturated. Depending on the amount of data on a web page and the capacity of the connection, bandwidth may be a bottleneck to performance.

- DNS lookup

-

Before a client can fetch a web page, it needs to translate the hostname to an IP address using the Domain Name System (DNS), the internet’s phone book (for the few of you readers who will understand the metaphor). This needs to happen for every unique hostname on the fetched HTML page as well, though luckily only once per hostname.

- Connection time

-

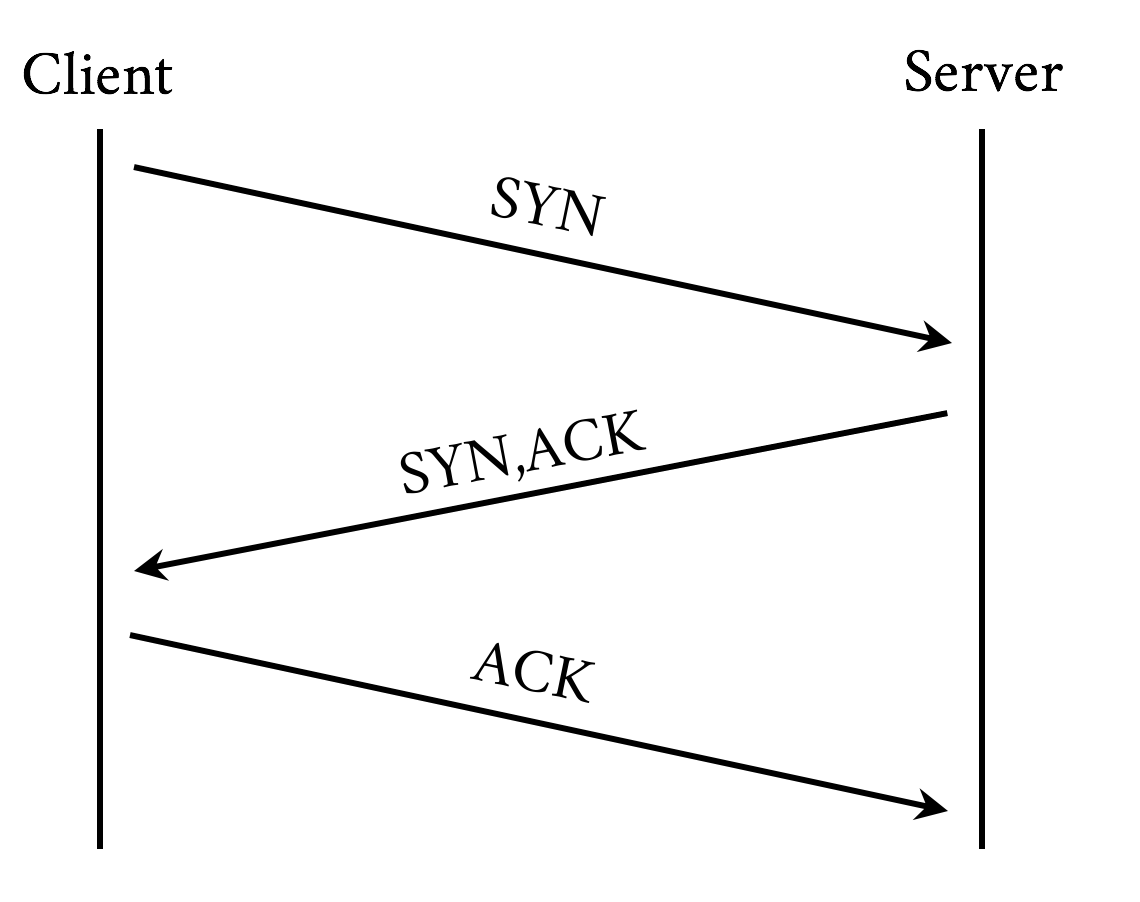

Establishing a connection requires a back and forth (round-trip) between the client and the server called the “three-way handshake.” This handshake time is generally related to the latency between the client and the server. The handshake involves sending a synchronize (SYN) packet from the client to the server, followed by a acknowledgment (ACK) of that SYN from the server, a SYN packet from the server to the client, and an ACK of that SYN from the client to the server. See Figure 3-3.

Figure 3-3. TCP three-way handshake

- TLS negotiation time

-

If the client is making an HTTPS connection, it needs to negotiate Transport Layer Security (TLS), the successor to Secure Socket Layer (SSL). This involves more round-trips on top of server and client processing time.

At this point the client has yet to even send the request and has already spent a DNS round-trip plus a few more for TCP and TLS. Next we have metrics that are more dependent on the content or the performance of the server itself as opposed to the network:

- Time to First Byte

-

TTFB is the measure of time from when the client starts the navigation to a web page until the first byte of the base page response is received. It is a sum of many of the preceding metrics as well as any server processing time. For objects on a page, TTFB measures the time from when the browser sends the request to the time the first byte comes back.

- Content download time

-

This is the Time to Last Byte (TTLB) for the requested object.

- Start render time

-

How quickly is the client able to start putting something on the screen for the user? This is the measurement of how long the user spends looking at a blank page.

- Document complete (aka Page Load Time)

-

This is the time that the page is considered done by the client.

When we look at web performance, especially if the goal is to create a new protocol that will make things faster, these are the metrics that must be kept in mind. We will reference these as we discuss the problems we face with HTTP/1.1 and why we might want something different.

With those metrics in mind you can see the internet’s trend toward more of everything has led to performance bottlenecks. Here are some of the mores we need to keep in mind:

- More bytes

-

A truism is that every year pages are larger, images are larger, and JavaScript and CSS are larger. Larger means more bytes to download and longer page load times.

- More objects

-

Objects are not just larger, but there are many more of them. More objects can contribute to higher times overall as everything is fetched and processed.

- More complexity

-

Pages and their dependent objects are getting increasingly complex as we add more and richer functionality. With complexity, the time to calculate and render pages, especially on weaker mobile devices with less processing power, goes up.

- More hostnames

-

Pages are not fetched from individual hosts, and most pages have tens of referenced hosts. Each hostname means more DNS lookups, connection times, and TLS negotiations.

- More TCP sockets

-

In an effort to address some of these mores, clients open multiple sockets per hostname. This increases the per-host connection negotiation overhead, adds load to the device, and potentially overloads network connections, causing effective bandwidth to drop due to retransmits and bufferbloat.

The Problems with HTTP/1

HTTP/1 has gotten us to were we are today, but the demands of the modern web put focus on its design limitations. Following are some of the more significant issues the protocol faces, and consequently the core problems that HTTP/2 was designed to address.

Note

There is no such thing as HTTP/1. We are using that (and h1) as a shorthand for HTTP/1.0 (RFC 1945) and HTTP/1.1 (RFC 2616).

Head of line blocking

A browser rarely wants to get a single object from a particular host. More often it wants to get many objects at the same time. Think of a website that puts all of its images on a particular domain. HTTP/1 provides no mechanism to ask for those objects simultaneously. On a single connection it needs to send a request and then wait for a response before it can send another. h1 has a feature called pipelining that allows it to send a bunch of requests at once, but it will still receive the responses one after another in the order they were sent. Additionally, pipelining is plagued by various issues around interop and deployment that make its use impractical.

If any problems occur with any of those requests or responses, everything else gets blocked behind that request/response. This is referred to as head of line blocking. It can grind the transmission and rendering of a web page to a halt. To combat this, today’s browser will open up to six connections to a particular host and send a request down each connection. This achieves a type of parallelism, but each connection can still suffer from head of line blocking. In addition, it is not a good use of limited device resources; the following section explains why.

Inefficient use of TCP

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) was designed to be conservative in its assumptions and fair to the different traffic uses on a network. Its congestion avoidance mechanisms are built to work on the poorest of networks and be relatively fair in the presence of competing demand. That is one of the reasons it has been as successful as it has—not necessarily because it is the fastest way to transmit data, but because it is one of the most reliable. Central to this is a concept called the congestion window. The congestion window is the number of TCP packets that the sender can transmit out before being acknowledged by the receiver. For example, if the congestion window was set to one, the sender would transmit one packet, and only when it gets the receiver’s acknowledgment of that packet would it send another.

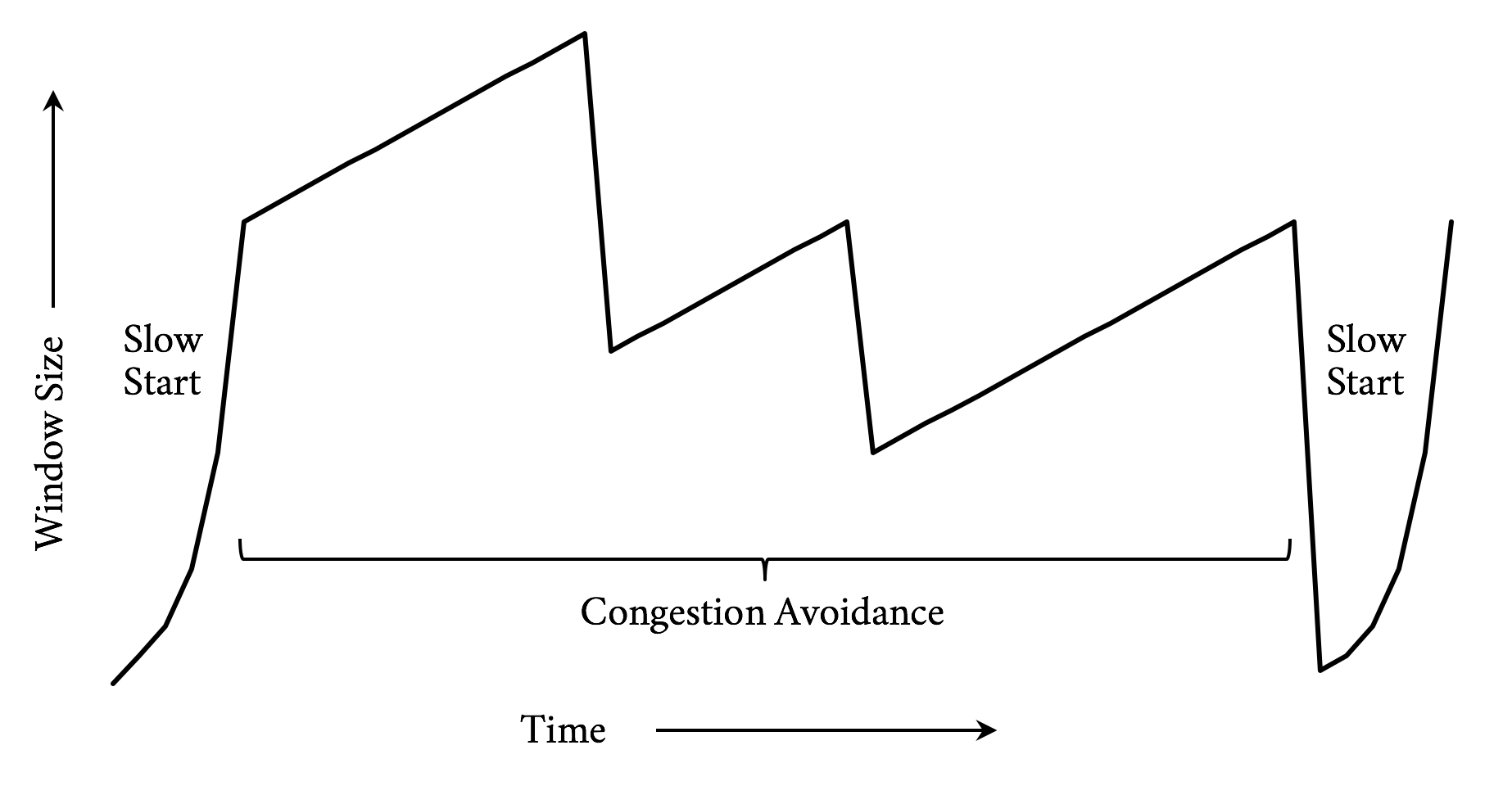

Sending one packet at a time is not terribly efficient. TCP has a concept called Slow Start to determine what the correct congestion window should be for the current connection. The design goal for Slow Start is to allow a new connection to feel out the state of a network and avoid making an already congested network worse. It allows the sender to send an additional unacknowledged packet for every acknowledgment it receives. This means that on a new connection after the first acknowledgment, it could send two packets, and when those two are acknowledged, it could send four, and so on. This geometric growth soon reaches an upper limit defined in the protocol, at which point the connection will enter what is called the congestion avoidance phase. See Figure 3-4.

Figure 3-4. TCP congestion control (Reno algorithm)

It takes a few round-trips to get to the optimal congestion window size. And those few round-trips are precious time when it comes to addressing performance. Modern operating systems commonly use an initial congestion window size between 4 and 10 packets. When you consider a packet has a maximum size of around 1,460 bytes on the lower end, only 5,840 bytes can be sent before the sender needs to wait for acknowledgments. Today’s web pages are averaging around 2 MB of data, including the HTML and all dependent objects. In a perfect world and with some generous hand waving, that means it will take around nine round-trips to transmit the page. On top of that, since browsers are commonly opening six connections to a particular host, they need to do this for each connection.

Note

Traditional TCP implementations employ congestion control algorithms that use loss as a feedback mechanism. When a packet is determined to have been lost, the algorithm will react by shrinking the congestion window. This is similar to navigating a dark room by deciding to turn when your shin collides with the coffee table. In the presence of timeouts where an expected response does not come in time, it will even reset the congestion window completely and reenter slow start. Newer algorithms take other factors into account, such as latency to provide a better feedback mechanism.

As previously mentioned, because h1 does not support multiplexing, a browser will commonly open up six connections to a particular host. This means this congestion window dance needs to occur six times in parallel. TCP will make certain that those connections play nicely together, but it does not guarantee that their performance will be optimal.

Fat message headers

Though h1 provides a mechanism for the compression of the requested objects, there is no way to compress the message headers. Headers can really add up, and though on responses the ratio of header size to object size may be very small, the headers make up the majority (if not all) of the bytes on requests. With cookies it is not uncommon for request headers to grow to a few kilobytes in size.

According to the HTTP archives, as of late 2016, the median request header is around 460 bytes. For a common web page with 140 objects on it, that means the total size of the requests is around 63 KB. Hark back to our discussion on TCP congestion window management and it might take three or four round-trips just to send the requests for the objects. The cost of the network latency begins to pile up quickly. Also, since upload bandwidth is often constrained by the network, especially in mobile cases, the windows might never get large enough to begin with, causing even more round-trips.

A lack of header compression can also cause clients to hit bandwidth limits. This is especially true on low-bandwidth or highly congested links. A classic example is the “Stadium Effect.” When tens of thousands of people are in the same place at the same time (such as at a major sporting event), cellular bandwidth is quickly exhausted. Smaller requests with compressed headers would have an easier time in situations like that and put less overall load on the system.

Limited priorities

When a browser opens up multiple sockets (each of which suffers from head of line blocking) to a host and starts requesting objects, its options for indicating the priorities of those requests is limited: it either sends a request or not. Since some objects on a page are much more important than others, this forces even more serialization as the browser holds off on requesting objects to get the higher priority objects firsts. This can lead to having overall longer page downloads since the servers do not have the opportunity to work on the lower priority items as the browser potentially waits for processing on the higher priority items. It can also result in cases where a high-priority object is discovered, but due to how the browser processed the page it gets stuck behind lower priority items already being fetched.

Third-party objects

Though not specifically a problem with HTTP/1, we will round out the list with a growing performance issue. Much of what is requested on a modern web page is completely out of the control of the web server, what we refer to as third-party objects. Third-party object retrieval and processing commonly accounts for half of the time spent loading today’s web pages. Though there are many tricks to minimize the impact of third-party objects on a page’s performance, with that much content out of a web developer’s direct control there is a good chance that some of those objects will have poor performance and delay or block the rendering of the page. Any discussion of web performance would be incomplete without mentioning this problem. (But, spoiler: h2 has no magic bullet with dealing with it either.)

Web Performance Techniques

While working at Yahoo! in the early 2000s, Steve Souders and his team proposed and measured the impact of techniques aimed at making web pages load faster on client web browsers. This research led him to author two seminal books, High Performance Websites2 and its follow-up Even Faster Websites,3 which laid the ground work for the science of web performance.

Since then, more studies have confirmed the direct impact of performance on the website owner’s bottom line, be it in terms of conversion rate, user engagement, or brand awareness. In 2010, Google added performance as one of the many parameters that come into play in its search engine to compute a given URL ranking.4 As the importance of a web presence keeps growing for most businesses, it has become critical for organizations to understand, measure, and optimize website performance.

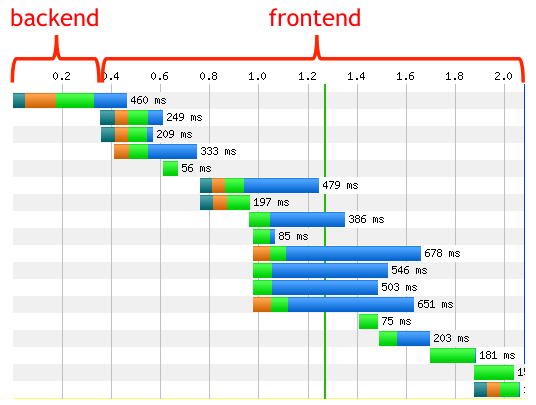

As discussed earlier in this chapter, for the majority of web pages the bulk of the browser’s time is not spent serving the initial content (generally the HTML) from the hosting infrastructure, but rather fetching all the assets and rendering the page on the client. This fact is captured by the diagram in Figure 3-5.5

Figure 3-5. Timeline frontent and backend

As a result, there has been an increased emphasis among web developers on improving the performance by reducing the client’s network latency and optimizing page render time. Quite literally, time is money.

Best Practices for Web Performance

As previously noted, the web has changed significantly—even in just the past few years. The relatively recent prevalence of mobile devices, the advances in JavaScript frameworks, and the evolution of the use of HTML warrant revisiting the rules laid out in the books referenced earlier, and going over the latest optimization techniques observed in the field.

Optimize DNS lookups

Since a DNS lookup needs to take place before a connection can be made to a host, it is critical that this resolution process be as fast as possible. The following best practices are a good place to start:

-

Limit the number of unique domains/hostnames. Of course, this is not always in your control; however, the relative performance impact of the number of unique hostnames will only grow when moving to HTTP/2.

-

Ensure low resolution latencies. Understand the topology of your DNS serving infrastructure and perform regular resolution time measurements from all the locations where your end users are (you can achieve this by using synthetic/real user monitoring). If you decide to rely on a third-party provider, select one best suited to your needs, as the quality of the services they offer can differ widely.

-

Leverage DNS prefetch6 from your initial HTML or response. This will start DNS resolution of specific hostnames on the page while the initial HTML is being downloaded and processed. For example, the following will prefetch a DNS resolition for ajax.googleapis.com:

<linkrel="dns-prefetch"href="//ajax.googleapis.com">

These techniques will help ensure the fixed overhead of DNS is minimized.

Optimize TCP connections

As discussed earlier in this chapter, opening new connections can be a time-consuming process. If the connection uses TLS (as they all should), the overhead is even higher. Mitigations for this overhead include:

-

Leverage preconnect,7 as it will remove connection times from the waterfall critical path by having the connection established before it is needed. For example:

<linkrel="preconnect"href="//fonts.example.com"crossorigin>

-

Use early termination. Leveraging a Content Delivery Network (CDN), connections can be terminated at the edges of the internet located close to the requesting client, and therefore can greatly minimize the round-trip latencies incurred by establishing a new connection. See “Content Delivery Networks (CDNs)” for more information on CDNs.

-

Implement the latest TLS best practices8 for optimizing HTTPS.

If a lot of resources are requested from the same hostname, the client browsers will automatically open parallel connections to the server to avoid resource-fetching bottlenecks. You don’t have direct control over the number of parallel connections a client browser will open for a given hostname, although most browsers now support six or more.

Avoid redirects

Redirects usually trigger connections to additional hostnames, which means an extra connection needs to be established. On radio networks (think mobile phones), an additional redirect may add hundreds of ms in latency, which is detrimental to the user experience, and eventually detrimental to the business running the websites. The obvious solution is to remove redirects entirely, as more often than not there is no “good” justification for some of them. If they cannot be simply removed, then you have two options:

-

Leverage a CDN to perform the redirect “in the cloud” on behalf of the client

-

If it is a same host redirect, use rewrite rules on the web server to avoid the redirect and map the user to the needed resource

Oftentimes, redirects are used to help with the dark art of Search Engine Optimization (SEO) to avoid short-term search result pain or consequent backend information layout changes. In such cases, you have to decide whether the redirect cost is worth the SEO benefits. Sometimes tearing the Band-Aid off in one go is the best long-term solution.

Cache on the client

Nothing is faster than retrieving an asset from the local cache, as no network connection is involved. As the saying goes (or at least will starting now), the fastest request is the one you do not make. In addition, when the content is retrieved locally, no charge is incurred either by the ISP or the CDN provider. The directive that tells the browser how long to cache an object is called the Time to Live, or TTL. Finding the best TTL for a given resource is not a perfect science; however, the following tried-and-tested guidelines are a good starting point:

-

So-called truly static content, like images or versioned content, can be cached forever on the client. Keep in mind, though, that even if the TTL is set to expire in a long time, say one month away, the client may have to fetch it from the origin before it expires due to premature eviction or cache wipes. The actual TTL will eventually depend on the device characteristics (specifically the amount of available disk storage for the cache) and the end user’s browsing habits and history.

-

For CSS/JS and personalized objects, cache for about twice the median session time. This duration is long enough for most users to get the resources locally while navigating a website, and short enough to almost guarantee fresh content will be pulled from the network during the next navigation session.

-

For other types of content, the ideal TTL will vary depending on the staleness threshold you are willing to live with for a given resource, so you’ll have to use your best judgment based on your requirements.

Client caching TTL can be set through the HTTP header “cache control” and the key “max-age” (in seconds), or the “expires” header.

Cache at the edge

Caching at the edge of the network provides a faster user experience and can offload the serving infrastructure from a great deal of traffic as all users can benefit from the shared cache in the cloud.

A resource, to be cacheable, must be:

-

Shareable between multiple users, and

-

Able to accept some level of staleness

Unlike client caching, items like personal information (user preferences, financial information, etc.) should never be cached at the edge since they cannot be shared. Similarly, assets that are very time sensitive, like stock tickers in a real-time trading application, should not be cached. This being said, everything else is cacheable, even if it’s only for a few seconds or minutes. For assets that don’t change very frequently but must be updated on very short notice, like breaking news, for instance, leverage the purging mechanisms offered by all major CDN vendors. This pattern is called “Hold ’til Told”: cache it forever until told not to.

Conditional caching

When the cache TTL expires, the client will initiate a request to the server. In many instances, though, the response will be identical to the cached copy and it would be a waste to re-download content that is already in cache. HTTP provides the ability to make conditional requests, which is effectively the client asking the server to, “Give me the object if it has changed, otherwise just tell me it is the same.” Using conditional requests can have a significant bandwidth and performance savings when an object may not often change, but making the freshest version of the object available quickly is important. To use conditional caching:

-

Include the Last-Modified-Since HTTP header in the request. The server will only return the full content if the latest content has been updated after the date in the header, else it will return a 304 response, with a new timestamp “Date” in the response header.

-

Include an entity tag, or ETag, with the request that uniquely identifies the object. The ETag is provided by the server in a header along with the object itself. The server will compare the current ETag with the one received from the request header, and if they match will only return a 304, else the full content.

Most web servers will honor these techniques for images and CSS/JS, but you should check that it is also in place for any other cached content.

Compression and minification

All textual content (HTML, JS, CSS, SVG, XML, JSON, fonts, etc.), can benefit from compression and minification. These two methods can be combined to dramatically reduce the size of the objects. Fewer bytes means fewer round-trips, which means less time spent.

Minification is a process for sucking all of the nonessential elements out of a text object. Generally these objects are written by humans in a manner that makes them easy to read and maintain. The browser does not care about readability, however, and removing that readability can save space. As a trivial example, consider the following HTML:

<html><head><!-- Change the title as you see fit --><title>My first web page</title></head><body><!-- Put your message of the day here --><p>Hello, World!</p></body></html>

This is a perfectly acceptable HTML page and will render perfectly (if boringly) in a browser. But there is information in it that the browser does not need, including comments, newlines, and spaces. A minified version could look like:

<html><head><title>My first web page</title></head><body><p>Hello, World!</p></body></html>

It is not as pretty nor as maintainable, but it takes half the number of bytes (92 versus 186).

Compression adds another layer of savings on top of minification. Compression takes objects and reduces their size in an algorithmic way that can be reversed without loss. A server will compress objects before they are sent and result in a 90% reduction in bytes on the wire. Common compression schemes include gzip and deflate, with a relative newcomer, Brotli, beginning to enter the scene.

Avoid blocking CSS/JS

CSS instructions will tell the client browser how and where to render content in the viewing area. As a consequence, clients will make sure to download all the CSS before painting the first pixel on the screen. While the browser pre-parser can be smart and fetch all the CSS it needs from the entire HTML early on, it is still a good practice to place all the CSS resource requests early in the HTML, in the head section of the document, and before any JS or images are fetched and processed.

JS will by default be fetched, parsed, and executed at the point it is located in the HTML, and will block the downloading and rendering of any resource past the said JS, until the browser is done with it. In some instances, it is desirable to have the downloading and execution of a given JS block the parsing and execution of the remainder of the HTML; for instance, when it instantiates a so-called tag-manager, or when it is critical that the JS be executed first to avoid references to nonexisting entities or race conditions.

However, most of the time this default blocking behavior incurs unnecessary delays and can even lead to single points of failure. To mitigate the potential negative effects of blocking JS, we recommend different strategies for both first-party content (that you control) and third-party content (that you don’t control):

-

Revisit their usage periodically. Over time, it is likely the web page keeps downloading some JS that may no longer be needed, and removing it is the fastest and most effective resolution path!

-

If the JS execution order is not critical and it must be run before the onload event triggers, then set the “async”9 attribute, as in:

<script async src=”/js/myfile.js”>.

This alone can improve your overall user experience tremendously by downloading the JS in parallel to the HTML parsing. Watch out for

document.writedirectives as they would most likely break your pages, so test carefully! -

If the JS execution ordering is important and you can afford to run the scripts after the DOM is loaded, then use the “defer” attribute,10 as in:

<script defer src="/js/myjs.js">

-

If the JS is not critical to the initial view, then you should only fetch (and process) the JS after the onload event fires.

-

You can consider fetching the JS through an iframe if you don’t want to delay the main onload event, as it’ll be processed separately from the main page. However, JS downloaded through an iframe may not have access to the main page elements.

If all this sounds a tad complicated, that’s because it is. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to this problem, and it can be hazardous to recommend a particular strategy without knowing the business imperatives and the full HTML context. The preceding list, though, is a good starting point to ensure that no JS is left blocking the rendering of the page without a valid reason.

Optimize images

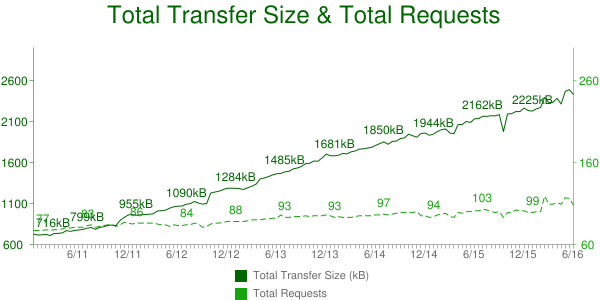

The relative and absolute weight of images for the most popular websites keeps increasing over time. The chart11 in Figure 3-6 shows the number of requests and bytes size per page over a five-year period.

Figure 3-6. Transfer size and number of requests from 2011–2016 (source: httparchive.com)

Since most modern websites are dominated by images, optimizing them can yield some of the largest performance benefits. Image optimizations all aim at delivering the fewest bytes to achieve a given visual quality. Many factors negatively influence this goal and ought to be addressed:

-

Image “metadata,” like the subject location, timestamps, image dimension, and resolution are often captured with the binary information, and should be removed before serving to the clients (just ensure you don’t remove the copyright and ICC profile data). This quality-lossless process can be done at build time. For PNG images, it is not unusual to see gains of about 10% in size reduction. If you want to learn more about image optimizations, you can read High Performance Images (O’Reilly 2016) by Tim Kadlec, Colin Bendell, Mike McCall, Yoav Weiss, Nick Doyle, and Guy Podjarny.

-

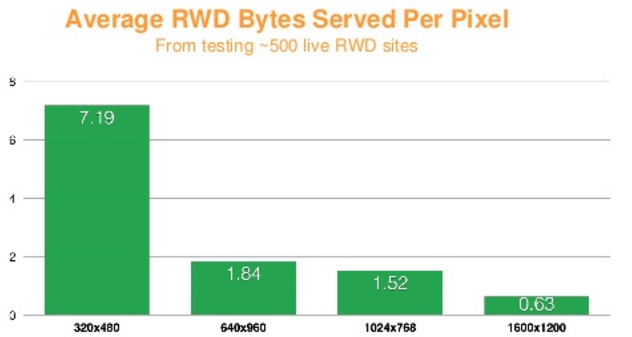

Image overloading refers to images that end up being scaled down by the browsers, either because the natural dimensions exceed the placement size in the browser viewport, or because the image resolution exceeds the device display’s capability. This scaling down not only wastes bandwidth, but also consumes significant CPU resources, which are sometimes in short supply for handheld devices. We commonly witness this effect in Responsive Web Design (RWD) sites, which indiscriminately serve the same images regardless of the rendering device. Figure 3-7 captures this over-download issue.

Figure 3-7. Average RWD bytes served per pixel. Source: http://goo.gl/6hOkQp

Techniques for mitigating image overloading involve serving images that are tailored (in terms of size and quality) to the user’s device, network conditions, and the expected visual quality.

Anti-Patterns

Because HTTP/2 will only open a single connection per hostname, some HTTP/1.1 best practices are turning into anti-patterns for h2. The following sections discuss some popular methods that no longer apply to h2-enabled websites.

Spriting and resource consolidation/inlining

Spriting aims at consolidating many small images into a larger one in order to only incur one resource request for multiple image elements. For instance, color swatches or navigation elements (arrows, icons, etc.) get consolidated into one larger image, called a sprite. In the HTTP/2 model, where a given request is no longer blocking and many requests can be handled in parallel, spriting becomes moot from a performance standpoint and website administrators no longer need to worry about creating them, although it is probably not worth the effort to undo them.

In the same vein, small text-like resources like JS and CSS are routinely consolidated into single larger resources, or embedded into the main HMTL, so as to also reduce the number of client-server connections. One negative effect is that a small CSS or JS, which may be cacheable on its own, may become inherently uncacheable if embedded in an otherwise noncacheable HTML, so such practices should be avoided when a site migrates from h1 to h2. However, a study published by khanacademy.org,12 November 2015, shows that packaging many small JS files into one may still make sense over h2, both for compression and CPU-saving purposes.

Sharding

Sharding aims at leveraging the browser’s ability to open multiple connections per hostname to parallelize asset download. The optimum number of shards for a given website is not an exact science and it’s fair to say that different views still prevail in the industry.

In an HTTP/2 world, it would require a significant amount of work for site administrators to unshard resources. A better approach is to keep the existing sharding, while ensuring the hostnames share a common certificate (Wildcard/SAN), mapped to the same server IP and port, in order to benefit from the browser network coalescence and save the connection establishment to each sharded hostname.

Cookie-less domains

In HTTP/1 the content of the request and response headers is never compressed. As the size of the headers has increased over time, it is no longer unusual to see cookie sizes larger than a single TCP packet (~1.5 KB). As a result, the cost of shuttling header information back and forth between the origin and the client may amount to measurable latency.

It was therefore a rational recommendation to set up cookie-less domains for resources that don’t rely on cookies, for instance, images.

With HTTP/2 though, the headers are compressed (see “Header Compression (HPACK)” in Chapter 5) and a “header history” is kept at both ends to avoid transmitting information already known. So if you perform a site redesign you can make your life simpler and avoid cookie-less domains.

Serving static objects from the same hostname as the HTML eliminates additional DNS lookups and (potentially) socket connections that delay fetching the static resources. You can improve performance by ensuring render-blocking resources are delivered over the same hostname as the HTML.

Summary

HTTP/1.1 has bred a messy if not exciting world of performance optimizations and best practices. The contortions that the industry has gone through to eek out performance have been extraordinary. One of the goals of HTTP/2 is to make many (though not all) of these techniques obsolete. Regardless, understanding them and the reasons they work will provide a deeper understanding of the web and how it works.