Chapter 5. React with JSX

In the last chapter, we looked at how the virtual DOM is a set of instructions that React follows when creating and updating a user interface. These instructions are made up of JavaScript objects called React elements. So far, we’ve learned two ways to create React elements: using React.createElement and using factories.

An alternative to typing out verbose React.createElement calls is JSX, a JavaScript extension that allows us to define React elements using syntax that looks similar to HTML. In this chapter, we are going to discuss how to use JSX to construct a virtual DOM with React elements.

React Elements as JSX

Facebook’s React team released JSX when they released React to provide a concise syntax for creating complex DOM trees with attributes. They also hoped to make React more readable, like HTML and XML.

In JSX, an element’s type is specified with a tag. The tag’s attributes represent the properties. The element’s children can be added between the opening and closing tags.

You can also add other JSX elements as children. If you have an unordered list, you can add child list item elements to it with JSX tags. It looks very similar to HTML (see Example 5-1).

Example 5-1. JSX for an unordered list

<ul><li>1 lb Salmon</li><li>1 cup Pine Nuts</li><li>2 cups Butter Lettuce</li><li>1 Yellow Squash</li><li>1/2 cup Olive Oil</li><li>3 cloves of Garlic</li></ul>

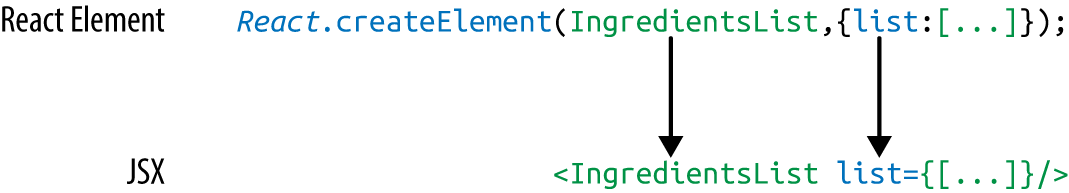

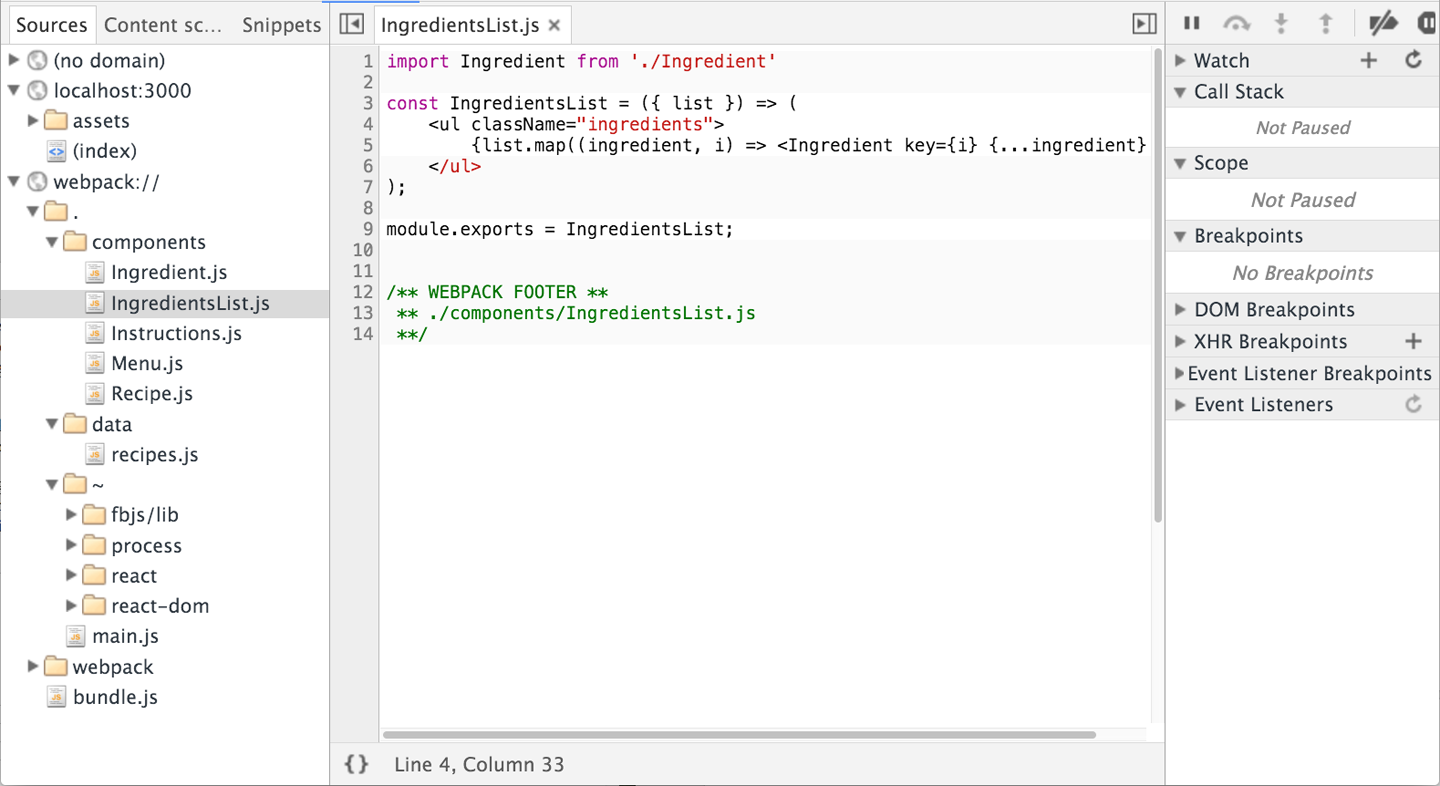

JSX works with components as well. Simply define the component using the class name. In Figure 5-1, we pass an array of ingredients to the IngredientsList as a property with JSX.

Figure 5-1. Creating the IngredientsList with JSX

When we pass the array of ingredients to this component, we need to surround it with curly braces. This is called a JavaScript expression, and we must use these when passing JavaScript values to components as properties. Component properties will take two types: either a string or a JavaScript expression. JavaScript expressions can include arrays, objects, and even functions. In order to include them, you must surround them in curly braces.

JSX Tips

JSX might look familiar, and most of the rules result in syntax that is similar to HTML. However, there are a few considerations that you should understand when working with JSX.

Nested components

JSX allows you to add components as children of other components. For example, inside the IngredientsList, we can render another component called Ingredient multiple times (Example 5-2).

Example 5-2. IngredientsList with three nested Ingredient components

<IngredientsList><Ingredient/><Ingredient/><Ingredient/></IngredientsList>

className

Since class is a reserved word in JavaScript, className is used to define the class attribute instead:

<h1className="fancy">Baked Salmon</h1>

JavaScript expressions

JavaScript expressions are wrapped in curly braces and indicate where variables shall be evaluated and their resulting values returned. For example, if we want to display the value of the title property in an element, we can insert that value using a JavaScript expression. The variable will be evaluated and its value returned:

<h1>{this.props.title}</h1>

Values of types other than string should also appear as JavaScript expressions:

<inputtype="checkbox"defaultChecked={false}/>

Evaluation

The JavaScript that is added in between the curly braces will get evaluated. This means that operations such as concatenation or addition will occur. This also means that functions found in JavaScript expressions will be invoked:

<h1>{"Hello"+this.props.title}</h1><h1>{this.props.title.toLowerCase().replace}</h1>functionappendTitle({this.props.title}){console.log(`${this.props.title}is great!`)}

Mapping arrays to JSX

JSX is JavaScript, so you can incorporate JSX directly inside of JavaScript functions. For example, you can map an array to JSX elements (Example 5-3).

Example 5-3. Array.map() with JSX

<ul>{this.props.ingredients.map((ingredient, i) =><likey={i}>{ingredient}</li>)}</ul>

JSX looks clean and readable, but it can’t be interpreted with a browser. All JSX must be converted into createElement calls or factories. Luckily, there is an excellent tool for this task: Babel.

Babel

Most software languages allow you to compile your source code. JavaScript is an interpreted language: the browser interprets the code as text, so there is no need to compile JavaScript. However, not all browsers support the latest ES6 and ES7 syntax, and no browser supports JSX syntax. Since we want to use the latest features of JavaScript along with JSX, we are going to need a way to convert our fancy source code into something that the browser can interpret. This process is called transpiling, and it is what Babel is designed to do.

The first version of the project was called 6to5, and it was released in September 2014. 6to5 was a tool that could be used to convert ES6 syntax to ES5 syntax, which is more widely supported by web browsers. As the project grew, it aimed to be a platform to support all of the latest changes in ECMAScript. It also grew to support transpiling JSX into pure React. The project was renamed to Babel in February 2015.

Babel is used in production at Facebook, Netflix, PayPal, Airbnb, and more. Previously, Facebook had created a JSX transformer that was their standard, but it was soon retired in favor of Babel.

There are many ways of working with Babel. The easiest way to get started is to include a link to the babel-core transpiler directly in your HTML, which will transpile any code in script blocks that have a type of “text/babel”. Babel will transpile the source code on the client before running it. Although this may not be the best solution for production, it is a great way to get started with JSX (see Example 5-4).

Example 5-4. Including babel-core

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><metacharset="utf-8"><title>React Examples</title></head><body><divclass="react-container"></div><!-- React Library & React DOM --><scriptsrc="https://unpkg.com/react@15.4.2/dist/react.js"></script><scriptsrc="https://unpkg.com/react-dom@15.4.2/dist/react-dom.js"></script><scriptsrc="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/babel-core/5.8.29/browser.js"></script><scripttype="text/babel">// JSX code here. Or link to separate JavaScript file that contains JSX.</script></body></html>

Babel v5.8 Required

To transpile code in the browser, use Babel v. 5.8. Babel 6.0+ will not work as an in-browser transformer.

Later in the chapter, we’ll look at how we can use Babel with webpack to transpile our JavaScript files statically. For now, using the in-browser transpiler will do.

Recipes as JSX

One of the reasons that we have grown to love React is that it allows us to write web applications with beautiful code. It is extremely rewarding to create beautifully written modules that clearly communicate how the application functions. JSX provides us with a nice, clean way to express React elements in our code that makes sense to us and is immediately readable by the engineers that make up our community. The drawback of JSX is that it is not readable by the browser. Before our code can be interpreted by the browser, it needs to be converted from JSX into pure React.

The array in Example 5-5 contains two recipes, and they represent our application’s current state.

Example 5-5. Array of recipes

vardata=[{"name":"Baked Salmon","ingredients":[{"name":"Salmon","amount":1,"measurement":"l lb"},{"name":"Pine Nuts","amount":1,"measurement":"cup"},{"name":"Butter Lettuce","amount":2,"measurement":"cups"},{"name":"Yellow Squash","amount":1,"measurement":"med"},{"name":"Olive Oil","amount":0.5,"measurement":"cup"},{"name":"Garlic","amount":3,"measurement":"cloves"}],"steps":["Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.","Spread the olive oil around a glass baking dish.","Add the salmon, garlic, and pine nuts to the dish.","Bake for 15 minutes.","Add the yellow squash and put back in the oven for 30 mins.","Remove from oven and let cool for 15 minutes. Add the lettuce and serve."]},{"name":"Fish Tacos","ingredients":[{"name":"Whitefish","amount":1,"measurement":"l lb"},{"name":"Cheese","amount":1,"measurement":"cup"},{"name":"Iceberg Lettuce","amount":2,"measurement":"cups"},{"name":"Tomatoes","amount":2,"measurement":"large"},{"name":"Tortillas","amount":3,"measurement":"med"}],"steps":["Cook the fish on the grill until hot.","Place the fish on the 3 tortillas.","Top them with lettuce, tomatoes, and cheese."]}];

The data is expressed in an array of two JavaScript objects. Each object contains the name of the recipe, a list of the ingredients required, and a list of steps necessary to cook the recipe.

We can create a UI for these recipes with two components: a Menu component for listing the recipes and a Recipe component that describes the UI for each recipe. It’s the Menu component that we will render to the DOM. We will pass our data to the Menu component as a property called recipes (Example 5-6).

Example 5-6. Recipe app code structure

// The data, an array of Recipe objectsvardata=[...];// A stateless functional component for an individual RecipeconstRecipe=(props)=>(...)// A stateless functional component for the Menu of RecipesconstMenu=(props)=>(...)// A call to ReactDOM.render to render our Menu into the current DOMReactDOM.render(<Menurecipes={data}title="Delicious Recipes"/>,document.getElementById("react-container"))

ES6 Support

We will be using ES6 in this file as well. When we transpile our code from JSX to pure React, Babel will also convert ES6 into common ES5 JavaScript that is readable by all browsers. Any ES6 features used have been discussed in Chapter 2.

The React elements within the Menu component are expressed as JSX (Example 5-7). Everything is contained within an article element. A header element, an h1 element, and a div.recipes element are used to describe the DOM for our menu. The value for the title property will be displayed as text within the h1.

Example 5-7. Menu component structure

constMenu=(props)=><article><header><h1>{props.title}</h1></header><divclassName="recipes"></div></article>

Inside of the div.recipes element, we add a component for each recipe (Example 5-8).

Example 5-8. Mapping recipe data

<divclassName="recipes">{props.recipes.map((recipe,i)=><Recipekey={i}name={recipe.name}ingredients={recipe.ingredients}steps={recipe.steps}/>)}</div>

In order to list the recipes within the div.recipes element, we use curly braces to add a JavaScript expression that will return an array of children. We can use the map function on the props.recipes array to return a component for each object within the array. As mentioned previously, each recipe contains a name, some ingredients, and cooking instructions (steps). We will need to pass this data to each Recipe as props. Also remember that we should use the key property to uniquely identify each element.

Using the JSX spread operator can improve our code. The JSX spread operator works like the object spread operator discussed in Chapter 2. It will add each field of the recipe object as a property of the Recipe component. The syntax in Example 5-9 accomplishes the same results.

Example 5-9. Enhancement: JSX spread operator

{props.recipes.map((recipe,i)=><Recipekey={i}{...recipe}/>)}

Another place we can make an ES6 improvement to our Menu component is where we take in the props argument. We can use object destructuring to scope the variables to this function. This allows us to access the title and recipes variables directly, no longer having to prefix them with props (Example 5-10).

Example 5-10. Refactored Menu component

constMenu=({title,recipes})=>(<article><header><h1>{title}</h1></header><divclassName="recipes">{recipes.map((recipe,i)=><Recipekey={i}{...recipe}/>)}</div></article>)

Now let’s code the component for each individual recipe (Example 5-11).

Example 5-11. Complete Recipe component

constRecipe=({name,ingredients,steps})=><sectionid={name.toLowerCase().replace(/ /g,"-")}><h1>{name}</h1><ulclassName="ingredients">{ingredients.map((ingredient,i)=><likey={i}>{ingredient.name}</li>)}</ul><sectionclassName="instructions"><h2>CookingInstructions</h2>{steps.map((step,i)=><pkey={i}>{step}</p>)}</section></section>

This component is also a stateless functional component. Each recipe has a string for the name, an array of objects for ingredients, and an array of strings for the steps. Using ES6 object destructuring, we can tell this component to locally scope those fields by name so we can access them directly without having to use props.name, or props.ingredients, props.steps.

The first JavaScript expression that we see is being used to set the id attribute for the root section element. It is converting the recipe’s name to a lowercase string and globally replacing spaces with dashes. The result is that “Baked Salmon” will be converted to “baked-salmon” (and likewise, if we had a recipe with the name “Boston Baked Beans” it would be converted to “boston-baked-beans”) before it is used as the id attribute in our UI. The value for name is also being displayed in an h1 as a text node.

Inside of the unordered list, a JavaScript expression is mapping each ingredient to an li element that displays the name of the ingredient. Within our instructions section, we see the same pattern being used to return a paragraph element where each step is displayed. These map functions are returning arrays of child elements.

The complete code for the application should look like Example 5-12.

Example 5-12. Finished code for recipe app

constdata=[{"name":"Baked Salmon","ingredients":[{"name":"Salmon","amount":1,"measurement":"l lb"},{"name":"Pine Nuts","amount":1,"measurement":"cup"},{"name":"Butter Lettuce","amount":2,"measurement":"cups"},{"name":"Yellow Squash","amount":1,"measurement":"med"},{"name":"Olive Oil","amount":0.5,"measurement":"cup"},{"name":"Garlic","amount":3,"measurement":"cloves"}],"steps":["Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.","Spread the olive oil around a glass baking dish.","Add the salmon, garlic, and pine nuts to the dish.","Bake for 15 minutes.","Add the yellow squash and put back in the oven for 30 mins.","Remove from oven and let cool for 15 minutes. Add the lettuce and serve."]},{"name":"Fish Tacos","ingredients":[{"name":"Whitefish","amount":1,"measurement":"l lb"},{"name":"Cheese","amount":1,"measurement":"cup"},{"name":"Iceberg Lettuce","amount":2,"measurement":"cups"},{"name":"Tomatoes","amount":2,"measurement":"large"},{"name":"Tortillas","amount":3,"measurement":"med"}],"steps":["Cook the fish on the grill until hot.","Place the fish on the 3 tortillas.","Top them with lettuce, tomatoes, and cheese."]}]constRecipe=({name,ingredients,steps})=><sectionid={name.toLowerCase().replace(/ /g,"-")}><h1>{name}</h1><ulclassName="ingredients">{ingredients.map((ingredient,i)=><likey={i}>{ingredient.name}</li>)}</ul><sectionclassName="instructions"><h2>CookingInstructions</h2>{steps.map((step,i)=><pkey={i}>{step}</p>)}</section></section>constMenu=({title,recipes})=><article><header><h1>{title}</h1></header><divclassName="recipes">{recipes.map((recipe,i)=><Recipekey={i}{...recipe}/>)}</div></article>ReactDOM.render(<Menurecipes={data}title="Delicious Recipes"/>,document.getElementById("react-container"))

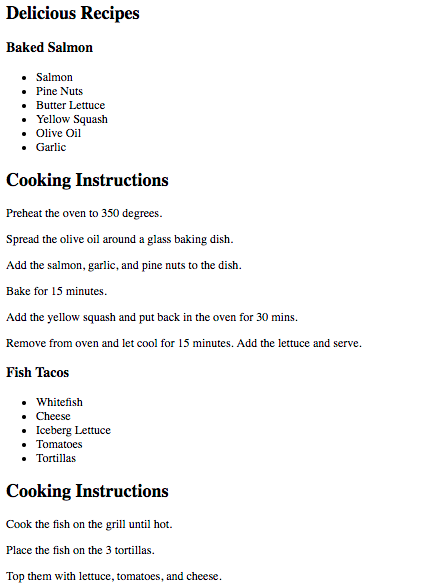

When we run this code in the browser, React will construct a UI using our instructions with the recipe data as shown in Figure 5-2.

Figure 5-2. Delicious Recipes output

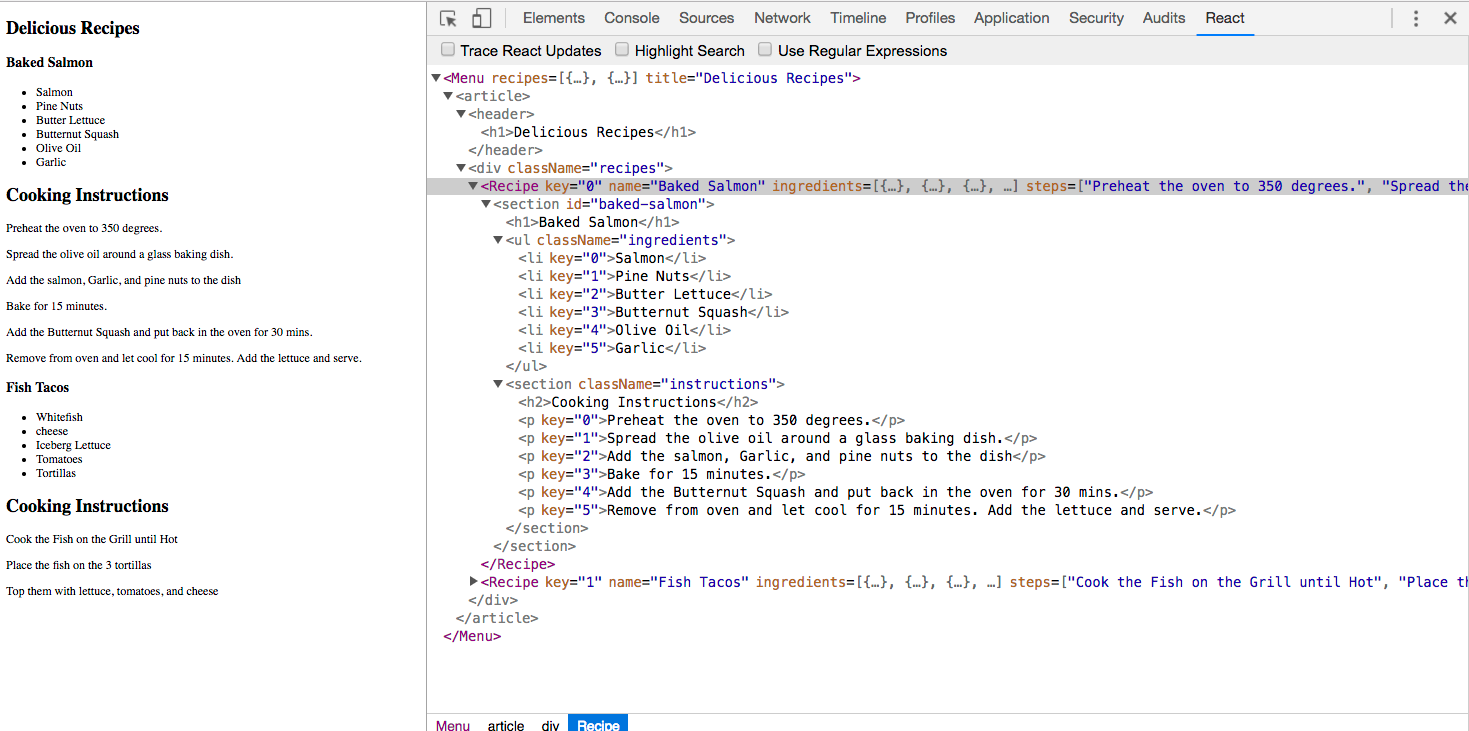

If you are using Google Chrome and you have the React Developer Tools Extension installed, you can take a look at the present state of the virtual DOM. To do this, open the developer tools and select the React tab (Figure 5-3).

Figure 5-3. Resulting virtual DOM in React Developer Tools

Here we can see our Menu and its child elements. The data array contains two objects for recipes, and we have two Recipe elements. Each Recipe element has properties for the recipe name, ingredients, and steps.

The virtual DOM is constructed based on the application’s state data being passed to the Menu component as a property. If we change the recipes array and rerender our Menu component, React will change this DOM as efficiently as possible.

Intro to Webpack

Once we start working in production with React, there are a lot of questions to consider: How do we want to deal with JSX and ES6+ transformation? How can we manage our dependencies? How can we optimize our images and CSS?

Many different tools have emerged to answer these questions, including Browserify, Gulp, and Grunt. Due to its features and widespread adoption by large companies, webpack has also emerged as one of the leading tools for bundling CommonJS modules (see Chapter 2 for more on CommonJS).

Webpack is billed as a module bundler. A module bundler takes all of our different files (JavaScript, LESS, CSS, JSX, ES6, and so on) and turns them into a single file. The two main benefits of modular bundling are modularity and network performance.

Modularity will allow you to break down your source code into parts, or modules, that are easier to work with, especially in a team environment.

Network performance is gained by only needing to load one dependency in the browser, the bundle. Each script tag makes an HTTP request, and there is a latency penalty for each HTTP request. Bundling all of the dependencies into a single file allows you to load everything with one HTTP request, thereby avoiding additional latency.

Aside from transpiling, webpack also can handle:

- Code splitting

-

Splits up your code into different chunks that can be loaded when you need them. Sometimes these are called rollups or layers; the aim is to break up code as needed for different pages or devices.

- Minification

-

Removes whitespace, line breaks, lengthy variable names, and unnecessary code to reduce the file size.

- Feature flagging

-

Sends code to one or more—but not all—environments when testing out features.

- Hot Module Replacement (HMR)

-

Watches for changes in source code. Changes only the updated modules immediately.

Webpack Loaders

A loader is a function that handles the transformations that we want to put our code through during the build process. If our application uses ES6, JSX, CoffeeScript, and other languages that can’t be read natively by the browser, we’ll specify the necessary loaders in the webpack.config.js file to do the work of converting the code into syntax that can be read natively by the browser.

Webpack has a huge number of loaders that fall into a few categories. The most common use case for loaders is transpiling from one dialect to another. For example, ES6 and React code is transpiled by including the babel-loader. We specify the types of files that Babel should be run on, then webpack takes care of the rest.

Another popular category of loaders is for styling. The css-loader looks for files with the .scss extension and compiles them to CSS. The css-loader can be used to include CSS modules in your bundle. All CSS is bundled as JavaScript and automatically added when the bundled JavaScript file is included. There’s no need to use link elements to include stylesheets.

Check out the full list of loaders if you’d like to see all of the different options.

Recipes App with a Webpack Build

The Recipes app that we built earlier in this chapter has some limitations that webpack will help us alleviate. Using a tool like webpack to statically build your client JavaScript makes it possible for teams to work together on large-scale web applications. We can also gain the following benefits by incorporating the webpack module bundler:

- Modularity

-

Using the CommonJS module pattern in order to export modules that will later be imported or required by another part of the application makes our source code more approachable. It allows development teams to easily work together by allowing them to create and work with separate files that will be statically combined into a single file before sending to production.

- Composing

-

With modules, we can build small, simple, reusable React components that we can compose efficiently into applications. Smaller components are easier to comprehend, test, and reuse. They are also easier to replace down the line when enhancing your applications.

- Speed

-

Packaging all of the application’s modules and dependencies into a single client bundle will reduce the load time of your application because there is latency associated with each HTTP request. Packaging everything together in a single file means that the client will only need to make a single request. Minifying the code in the bundle will improve load time as well.

- Consistency

-

Since webpack will transpile JSX into React and ES6 or even ES7 into universal JavaScript, we can start using tomorrow’s JavaScript syntax today. Babel supports a wide range of ESNext syntax, which means we do not have to worry about whether the browser supports our code. It allows developers to consistently use cutting-edge JavaScript syntax.

Breaking components into modules

Approaching the Recipes app with the ability to use webpack and Babel allows us to break our code down into modules that use ES6 syntax. Let’s take a look at our stateless functional component for recipes (Example 5-13).

Example 5-13. Current Recipe component

constRecipe=({name,ingredients,steps})=><sectionid="baked-salmon"><h1>{name}</h1><ulclassName="ingredients">{ingredients.map((ingredient,i)=><likey={i}>{ingredient.name}</li>)}</ul><sectionclassName="instructions"><h2>CookingInstructions</h2>{steps.map((step,i)=><pkey={i}>{step}</p>)}</section></section>

This component is doing quite a bit. We are displaying the name of the recipe, constructing an unordered list of ingredients, and displaying the instructions, with each step getting its own paragraph element.

A more functional approach to the Recipe component would be to break it up into smaller, more focused stateless functional components and compose them together. We can start by pulling the instructions out into their own stateless functional component and creating a module in a separate file that we can use for any set of instructions (Example 5-14).

Example 5-14. Instructions component

constInstructions=({title,steps})=><sectionclassName="instructions"><h2>{title}</h2>{steps.map((s,i)=><pkey={i}>{s}</p>)}</section>exportdefaultInstructions

Here we have created a new component called Instructions. We will pass the title of the instructions and the steps to this component. This way we can reuse this component for “Cooking Instructions,” “Baking Instructions,” “Prep Instructions”, or a “Pre-cook Checklist”—anything that has steps.

Now think about the ingredients. In the Recipe component, we are only displaying the ingredient names, but each ingredient in the data for the recipe has an amount and measurement as well. We could create a stateless functional component to represent a single ingredient (Example 5-15).

Example 5-15. Ingredient component

constIngredient=({amount,measurement,name})=><li><spanclassName="amount">{amount}</span><spanclassName="measurement">{measurement}</span><spanclassName="name">{name}</span></li>exportdefaultIngredient

Here we assume each ingredient has an amount, a measurement, and a name. We destructure those values from our props object and display them each in independent classed span elements.

Using the Ingredient component, we can construct an IngredientsList component that can be used any time we need to display a list of ingredients (Example 5-16).

Example 5-16. IngredientsList using Ingredient component

importIngredientfrom'./Ingredient'constIngredientsList=({list})=><ulclassName="ingredients">{list.map((ingredient,i)=><Ingredientkey={i}{...ingredient}/>)}</ul>exportdefaultIngredientsList

In this file, we first import the Ingredient component because we are going to use it for each ingredient. The ingredients are passed to this component as an array in a property called list. Each ingredient in the list array will be mapped to the Ingredient component. The JSX spread operator is used to pass all of the data to the Ingredient component as props.

Using spread operator:

<Ingredient{...ingredient}/>

is another way of expressing:

<Ingredientamount={ingredient.amount}measurement={ingredient.measurement}name={ingredient.name}/>

So, given an ingredient with these fields:

letingredient={amount:1,measurement:'cup',name:'sugar'}

we get:

<Ingredientamount={1}measurement="cup"name="sugar"/>

Now that we have components for ingredients and instructions, we can compose recipes using these components (Example 5-17).

Example 5-17. Refactored Recipe component

importIngredientsListfrom'./IngredientsList'importInstructionsfrom'./Instructions'constRecipe=({name,ingredients,steps})=><sectionid={name.toLowerCase().replace(/ /g,'-')}><h1>{name}</h1><IngredientsListlist={ingredients}/><Instructionstitle="Cooking Instructions"steps={steps}/></section>exportdefaultRecipe

First we import the components that we are going to use, IngredientsList and Instructions. Now we can use them to create the Recipe component. Instead of a bunch of complicated code building out the entire recipe in one place, we have expressed our recipe more declaratively by composing smaller components. Not only is the code nice and simple, but it also reads well. This shows us that a recipe should display the name of the recipe, a list of ingredients, and some cooking instructions. We’ve abstracted away what it means to display ingredients and instructions into smaller, simple components.

In a modular approach with CommonJS, the Menu component would look pretty similar. The key difference is that it would live in its own file, import the modules that it needs to use, and export itself (Example 5-18).

Example 5-18. Completed Menu component

importRecipefrom'./Recipe'constMenu=({recipes})=><article><header><h1>DeliciousRecipes</h1></header><divclassName="recipes">{recipes.map((recipe,i)=><Recipekey={i}{...recipe}/>)}</div></article>exportdefaultMenu

We still need to use ReactDOM to render the Menu component. We will still have a index.js file, but it will look much different (Example 5-19).

Example 5-19. Completed index.js file

importReactfrom'react'import{render}from'react-dom'importMenufrom'./components/Menu'importdatafrom'./data/recipes'window.React=Reactrender(<Menurecipes={data}/>,document.getElementById("react-container"))

The first four statements import the necessary modules for our app to work. Instead of loading react and react-dom via the script tag, we import them so webpack can add them to our bundle. We also need the Menu component, and a sample data array which has been moved to a separate module. It still contains two recipes: Baked Salmon and Fish Tacos.

All of our imported variables are local to the index.js file. Setting window.React to React exposes the React library globally in the browser. This way all calls to React.createElement are assured to work.

When we render the Menu component, we pass the array of recipe data to this component as a property. This single ReactDOM.render call will mount and render our Menu component.

Now that we have pulled our code apart into separate modules and files, let’s create a static build process with webpack that will put everything back together into a single file.

Installing webpack dependencies

In order to create a static build process with webpack, we’ll need to install a few things. Everything that we need can be installed with npm. First, we might as well install webpack globally so we can use the webpack command anywhere:

sudo npm install -g webpack

Webpack is also going to work with Babel to transpile our code from JSX and ES6 to JavaScript that runs in the browser. We are going to use a few loaders along with a few presets to accomplish this task:

npm install babel-core babel-loader babel-preset-env babel-preset-react babel-preset-stage-0 --save-dev

Our application uses React and ReactDOM. We’ve been loading these dependencies with the script tag. Now we are going to let webpack add them to our bundle. We’ll need to install the dependencies for React and ReactDOM locally:

npm install react react-dom --save

This adds the necessary scripts for react and react-dom to the ./node_modules folder. Now we have everything needed to set up a static build process with webpack.

Webpack configuration

For this modular Recipes app to work, we are going to need to tell webpack how to bundle our source code into a single file. We can do this with configuration files, and the default webpack configuration file is always webpack.config.js.

The starting file for our Recipes app is index.js. It imports React, ReactDOM, and the Menu.js file. This is what we want to run in the browser first. Wherever webpack finds an import statement, it will find the associated module in the filesystem and include it in the bundle. Index.js imports Menu.js, Menu.js imports Recipe.js, Recipe.js imports Instructions.js and IngredientsList.js, and IngredientsList.js imports Ingredient.js. Webpack will follow this import tree and include all of these necessary modules in our bundle.

ES6 import Statements

We are using ES6 import statements, which are not presently supported by most browsers or by Node.js. The reason ES6 import statements work is because Babel will convert them into require('module/path'); statements in our final code. The require function is how CommonJS modules are typically loaded.

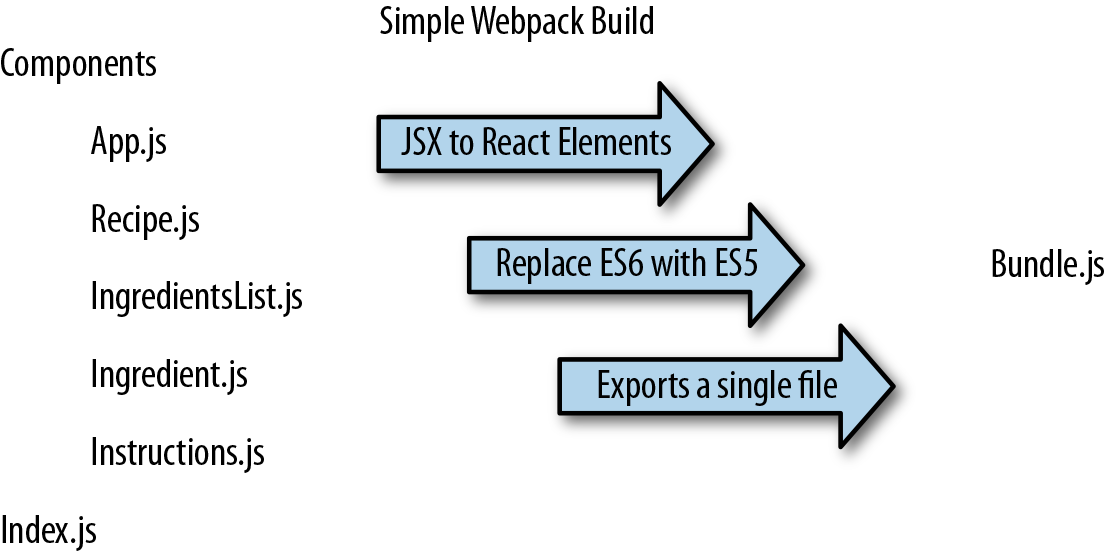

As webpack builds our bundle, we need to tell webpack to transpile JSX to pure React elements. We also need to convert any ES6 syntax to ES5 syntax. Our build process will initially have three steps (Figure 5-4).

Figure 5-4. Recipe app build process

The webpack.config.js file is just another module that exports a JavaScript literal object that describes the actions that webpack should take. This file (Example 5-20) should be saved to the root folder of the project, right next to the index.js file.

Example 5-20. webpack.config.js

module.exports={entry:"./src/index.js",output:{path:"dist/assets",filename:"bundle.js"},module:{rules:[{test:/\.js$/,exclude:/(node_modules)/,loader:['babel-loader'],query:{presets:['env','stage-0','react']}}]}}

First, we tell webpack that our client entry file is ./src/index.js. It will automatically build the dependency tree based upon import statements starting in that file. Next, we specify that we want to output a bundled JavaScript file to ./dist/assets/bundle.js. This is where webpack will place the final packaged JavaScript.

The next set of instructions for webpack consists of a list of loaders to run on specified modules. The rules field is an array because there are many types of loaders that you can incorporate with webpack. In this example, we are only incorporating babel.

Each loader is a JavaScript object. The test field is a regular expression that matches the file path of each module that the loader should operate on. In this case, we are running the babel-loader on all imported JavaScript files except those found in the node_modules folder. When the babel-loader runs, it will use presets for ES2015 (ES6) and React to transpile any ES6 or JSX syntax into JavaScript that will run in most browsers.

Webpack is run statically. Typically bundles are created before the app is deployed to the server. Since you have installed webpack globally, you can run it from the command line:

$ webpack

Time: 1727ms

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

bundle.js 693 kB 0 [emitted] main

+ 169 hidden modules

Webpack will either succeed and create a bundle, or fail and show you an error. Most errors have to do with broken import references. When debugging webpack errors, look closely at the filenames and file paths used in import statements.

Loading the bundle

We have a bundle, so now what? We exported the bundle to the dist folder. This folder contains the files that we want to run on the web server. The dist folder is where the index.html file (Example 5-21) should be placed. This file needs to include a target div element where the React Menu component will be mounted. It also requires a single script tag that will load our bundled JavaScript.

Example 5-21. index.html

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><metacharset="utf-8"><title>React Recipes App</title></head><body><divid="react-container"></div><scriptsrc="assets/bundle.js"></script></body></html>

This is the home page for your app. It will load everything it needs from one file, one HTTP request: bundle.js. You will need to deploy these files to your web server or build a web server application that will serve these files with something like Node.js or Ruby on Rails.

Source mapping

Bundling our code into a single file can cause some setbacks when it comes time to debug the application in the browser. We can eliminate this problem by providing a source map. A source map is a file that maps a bundle to the original source files. With webpack, all we have to do is add a couple of lines to our webpack.config.js file (Example 5-22).

Example 5-22. webpack.config.js with source mapping

module.exports={entry:"./src/index.js",output:{path:"dist/assets",filename:"bundle.js",sourceMapFilename:'bundle.map'},devtool:'#source-map',module:{rules:[{test:/\.js$/,exclude:/(node_modules)/,loader:['babel-loader'],query:{presets:['env','stage-0','react']}}]}}

Setting the devtool property to '#source-map' tells webpack that you want to use source mapping. A sourceMapFilename is required. It is always a good idea to name your source map file after the target dependency. Webpack will associate the bundle with the source map during the export.

The next time you run webpack, you will see that two output files are generated and added to the assets folder: the original bundle.js and bundle.map.

The source map is going to let us debug using our original source files. In the Sources tab of your browser’s developer tools, you should find a folder named webpack://. Inside of this folder, you will see all of the source files in your bundle (Figure 5-5).

Figure 5-5. Sources panel of Chrome Developer Tools

You can debug from these files using the browser’s step-through debugger. Clicking on any line number adds a breakpoint. Refreshing the browser will pause JavaScript processing when any breakpoints are reached in your source file. You can inspect scoped variables in the Scope panel or add variables to Watch in the watch panel.

Optimizing the bundle

The output bundle file is still simply a text file, so reducing the amount of text in this file will reduce the file size and cause it to load faster over HTTP. Some things that can be done to reduce the file size include removing all whitespace, reducing variable names to a single character, and removing any lines of code that the interpreter will never reach. Reducing the size of your JavaScript file with these tricks is referred to as minifying or uglifying your code.

Webpack has a built-in plugin that you can use to uglify the bundle. In order to use it, you will need to install webpack locally:

npm install webpack --save-dev

We can add extra steps to the build process using webpack plugins. In this example, we are going to add a step to our build process to uglify our output bundle, which will significantly reduce the file size (Example 5-23).

Example 5-23. webpack.config.js with Uglify plugin

varwebpack=require("webpack");module.exports={entry:"./src/index.js",output:{path:"dist/assets",filename:"bundle.js",sourceMapFilename:'bundle.map'},devtool:'#source-map',module:{rules:[{test:/\.js$/,exclude:/(node_modules)/,loader:['babel-loader'],query:{presets:['env','stage-0','react']}}]},plugins:[newwebpack.optimize.UglifyJsPlugin({sourceMap:true,warnings:false,mangle:true})]}

To use the Uglify plugin, we need to require webpack, which is why we needed to install webpack locally.

UglifyJsPlugin is a function that gets instructions from its arguments. Once we uglify our code, it will become unrecognizable. We are going to need a source map, which is why sourceMap is set to true. Setting warnings to false will remove any console warnings from the exported bundle. Mangling our code means that we are going to reduce long variable names like recipes or ingredients to a single letter.

The next time you run webpack, you will see that the size of your bundled output file has been significantly reduced, and it’s no longer recognizable. Including a source map will still allow you to debug from your original source even though your bundle has been minified.

create-react-app

As the Facebook team mentions in their blog, “the React ecosystem has commonly become associated with an overwhelming explosion of tools.”1 In response to this, the React team launched create-react-app a command-line tool that autogenerates a React project. create-react-app was inspired by the Ember CLI project, and it lets developers get started with React projects quickly without the manual configuration of webpack, Babel, ESLint, and associated tools.

To get started with create-react-app, install the package globally:

npm install -g create-react-app

Then, use the command and the name of the folder where you’d like the app to be created:

create-react-app my-react-project

This will create a React project in that directory with just three dependencies: React, ReactDOM, and react-scripts. react-scripts was also created by Facebook and is where the real magic happens. It installs Babel, ESLint, webpack, and more, so that you don’t have to configure them manually. Within the generated project folder, you’ll also find a src folder containing an App.js file. Here, you can edit the root component and import other component files.

From within the my-react-project folder, you can run npm start. If you prefer, you can also run yarn start. This will start your application on port 3000.

You can run tests with npm test or yarn test. This runs all of the test files in the project in an interactive mode.

You can also run the npm run build command. Using yarn, run yarn build.

This will create a production-ready bundle that has been transpiled and minified.

create-react-app is a great tool for beginners and experienced React developers alike. As the tool evolves, more functionality will likely be added, so you can keep an eye on the changes on GitHub.

1 Dan Abramov, “Create Apps with No Configuration”, React Blog, July 22, 2016.