Chapter 5. PDFs and Problem Solving in Python

Publishing data only in PDFs is criminal, but sometimes you don’t have other options. In this chapter, you are going to learn how to parse PDFs, and in doing so you will learn how to troubleshoot your code.

We will also cover how to write a script, starting with some basic concepts like imports, and introduce some more complexity. Throughout this chapter, you will learn a variety of ways to think about and tackle problems in your code.

Avoid Using PDFs!

The data used in this section is the same data as in the previous chapter, but in PDF form. Normally, one does not seek data in difficult-to-parse formats, but we did for this book because the data you need to work with may not always be in the ideal format. You can find the PDF we use in this chapter in the book’s GitHub repository.

There are a few things you need to consider before you start parsing PDF data:

-

Have you tried to find the data in another form? If you can’t find it online, try using a phone or email.

-

Have you tried to copy and paste the data from the document? Sometimes, you can easily select, copy, and paste data from a PDF into a spreadsheet. This doesn’t always work, though, and it is not scalable (meaning you can’t do it for many files or pages quickly).

If you can’t avoid dealing with PDFs, you’ll need to learn how to parse your data with Python. Let’s get started.

Programmatic Approaches to PDF Parsing

PDFs are more difficult to work with than Excel files because each one can be in an unpredictable format. (When you have a series of PDF files, parsing comes in handy, because hopefully they will be a consistent set of documents.)

PDF tools handle documents in various ways, including by converting the PDFs to text. As we were writing this book, Danielle Cervantes started a conversation about PDF tools on a listserv for journalists called NICAR. The conversation led to the compilation of the following list of PDF parsing tools:

-

ABBYY’s Transformer

-

Able2ExtractPro

-

Acrobat Professional

-

Adobe Reader

-

Apache Tika

-

Cogniview’s PDF to Excel

-

CometDocs

-

Docsplit

-

Nitro Pro

-

PDF XChange Viewer

-

pdfminer -

pdftk -

pdftotext -

Poppler

-

Tabula

-

Tesseract

-

xPDF

-

Zamzar

Besides these tools, you can also parse PDFs with many programming languages—including Python.

Note

Just because you know a tool like Python doesn’t mean it’s always the best tool for the job. Given the variety of tools available, you may find another tool is easier for part of your task (such as data extraction). Keep an open mind and investigate many options before proceeding.

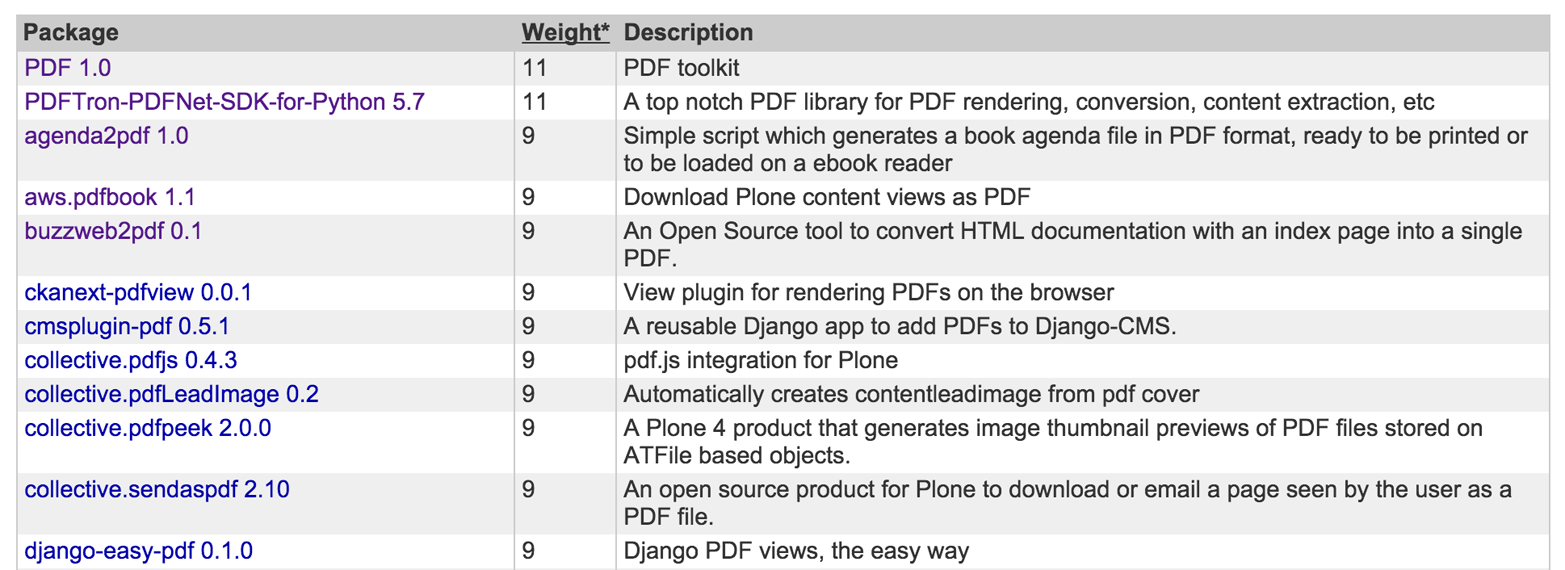

As mentioned in “Installing Python Packages”, PyPI is a convenient place for us to look for Python packages. If you search for “PDF”, you’ll get a bunch of results, similar to those shown in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1. PDF packages on PyPI

If you start looking through these options to get more information on each of the libraries, none of them will look like an obvious choice for parsing PDFs. If you try a couple more searches, such as “parse pdf,” more options will surface, but there is no obvious leader. So, we went back to search engines to look for what people are using.

Warning

Watch the publication dates on the materials you find when you are looking for libraries or solutions. The older a post or question is, the greater the probability it might be out of date and no longer usable. Try searching within the past two years, then extend further only if needed.

After looking at various tutorials, documentation, blog posts, and a couple of helpful articles such as this one, we decided to try the slate library.

Tip

slate worked well for what we needed, but this won’t always be the case. It’s OK to abandon something and start over. If there are multiple options, use what makes sense to you, even if someone tells you that it is not the “best” tool. Which tool is best is a matter of opinion. When you’re learning how to program, the best tool is the most intuitive one.

Opening and Reading Using slate

We decided to use the slate library for this problem, so let’s go ahead and install it. On your command line, run the following:

pip install slate

Now you have slate installed, so you can create a script with the following code and save it as parse_pdf.py. Make sure it is in the same folder as the PDF file, or correct the file path. This code prints the first two pages of the file:

importslate='EN-FINAL Table 9.pdf'withopen(,'rb')asf:doc=slate.(f)forpageindoc[:2]:page

Imports the

slatelibrary.

Creates a string variable to hold the file path—make sure your spaces and cases match exactly.

Passes the filename string to Python’s

openfunction, so Python can open the file. Python will open the file as the variablef.

Passes the opened file known as

ftoslate.PDF(f), soslatecan parse the PDF into a usable format.

Loops over the first couple of pages in the doc and outputs them, so we know everything is working.

Warning

Usually pip will install all necessary dependencies; however, it depends on the package managers to list them properly. If you see an ImportError, using this library or otherwise, you should carefully read the next line and see what packages are not installed. If you received the message ImportError: No module named pdfminer.pdfparser when running this code, it means installing slate did not properly install pdfminer, even though it’s a requirement. To do so, you need to run pip

install --upgrade --ignore-installed slate==0.3 pdfminer==20110515 (as documented in the slate issue tracker).

Run the script, and then compare the output to what is in the PDF.

Here is the first page:

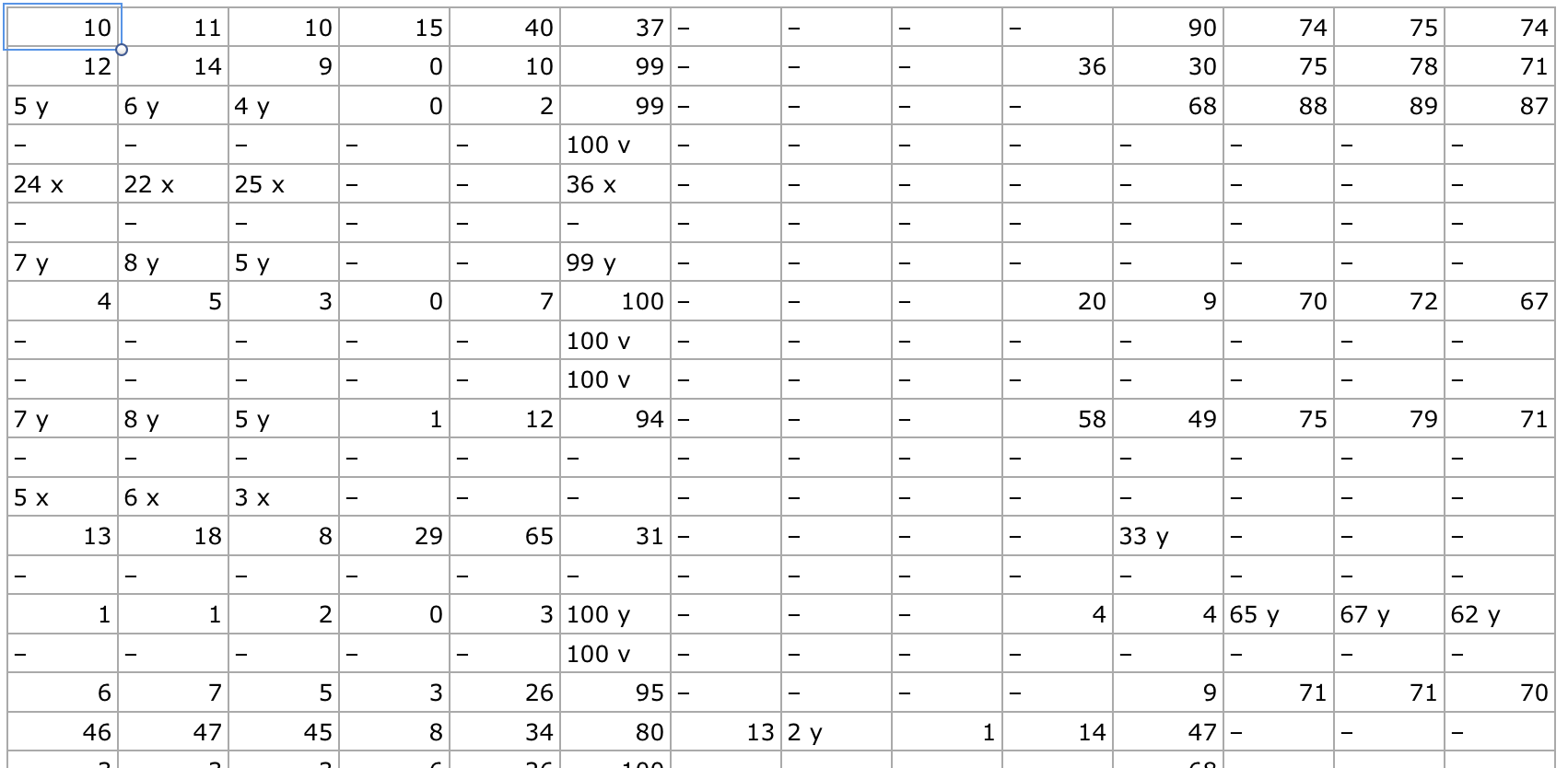

TABLE 9Afghanistan 10 11 10 15 40 37 – – – – 90 74 75 74Albania 12 14 9 0 10 99 – – – 36 30 75 78 71Algeria 5 y 6 y 4 y 0 2 99 – – – – 68 88 89 87Andorra – – – – – 100 v – – – – – – – –Angola 24 x 22 x 25 x – – 36 x – – – – – – – –Antigua and Barbuda – – – – – – – – – – – – – –Argentina 7 y 8 y 5 y – – 99 y – – – – – – – –Armenia 4 5 3 0 7 100 – – – 20 9 70 72 67Australia – – – – – 100 v – – – – – – – –Austria – – – – – 100 v – – – – – – – –Azerbaijan 7 y 8 y 5 y 1 12 94 – – – 58 49 75 79 71Bahamas – – – – – – – – – – – – – –Bahrain 5 x 6 x 3 x – – – – – – – – – – –Bangladesh 13 18 8 29 65 31 – – – – 33 y – – –Barbados – – – – – – – – – – – – – –Belarus 1 1 2 0 3 100 y – – – 4 4 65 y 67 y 62 yBelgium – – – – – 100 v – – – – – – – –Belize 6 7 5 3 26 95 – – – – 9 71 71 70Benin 46 47 45 8 34 80 13 2 y 1 14 47 – – –Bhutan 3 3 3 6 26 100 – – – – 68 – – –Bolivia ( Plurinational State of) 26 y 28 y 24 y 3 22 76 y – – – – 16 – – –Bosnia and Herzegovina 5 7 4 0 4 100 – – – 6 5 55 60 50Botswana 9 y 11 y 7 y – – 72 – – – – – – – –Brazil 9 y 11 y 6 y 11 36 93 y – – – – – – – –Brunei Darussalam – – – – – – – – – – – – – –Bulgaria – – – – – 100 v – – – – – – – –Burkina Faso 39 42 36 10 52 77 76 13 9 34 44 83 84 82Burundi 26 26 27 3 20 75 – – – 44 73 – – –Cabo Verde 3 x,y 4 x,y 3 x,y 3 18 91 – – – 16 y 17 – – –Cambodia 36 y 36 y 36 y 2 18 62 – – – 22 y 46 y – – –Cameroon 42 43 40 13 38 61 1 1 y 7 39 47 93 93 93Canada – – – – – 100 v – – – – – – – –Central African Republic 29 27 30 29 68 61 24 1 11 80 y 80 92 92 92Chad 26 25 28 29 68 16 44 18 y 38 – 62 84 85 84Chile 3 x 3 x 2 x – – 100 y – – – – – – – –China – – – – – – – – – – – – – –Colombia 13 y 17 y 9 y 6 23 97 – – – – – – – –Comoros 27 x 26 x 28 x – – 88 x – – – – – – – –Congo 25 24 25 7 33 91 – – – – 76 – – –TABLE 9 CHILD PROTECTIONCountries and areasChild labour (%)+ 2005–2012*Child marriage (%) 2005–2012*Birth registration (%)+ 2005–2012*totalFemale genital mutilation/cutting (%)+ 2002–2012*Justification of wife beating (%) 2005–2012*Violent discipline (%)+ 2005–2012*prevalenceattitudestotalmalefemalemarried by 15married by 18womenagirlsbsupport for the practicecmalefemaletotalmalefemale78 THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2014 IN NUMBERS

If you look at your PDF, it’s easy to see the pattern of rows in the page. Let’s check what data type the page is:

forpageindoc[:2]:type(page)

Running that generates the following output:

<type'str'><type'str'>

So, we know a page in slate is a long string. This is helpful because we now understand we can use string methods (for a refresher on these, refer back to Chapter 2).

Overall, this file was not difficult to read. Because it contains only tables and barely any text, slate could parse it pretty well. In some cases, the tables are buried inside the text, so you might have to skip lines to get to the data you need. If you do have to skip lines, you can follow the pattern in the Excel example in the previous chapter, where we created a counter incremented by one for each row, used it to find the region, and then used the technique described in “What Is Indexing?” to select only the data we needed.

Our end goal is to get the data from the PDF into the same format as the Excel file output. To do so, we need to break the strings apart to pull out each row. The thought process behind this is to look for patterns to identify where a new row begins. That might sound easy, but it can get pretty complicated.

When dealing with large strings, people often use regular expressions (RegEx). If you aren’t familiar with regex and writing regex searches, this could be a difficult approach. If you are up for the challenge and want to learn more about regex with Python, check out the section “RegEx Matching”. For our purposes, we’ll try a simpler approach to extract our data.

Converting PDF to Text

First we want to convert the PDF to text; then we will parse it. This approach is better if you have a very large file or files. (In the slate library, our script will parse the PDF every time it runs. This can be very time- and memory-consuming with large or numerous files).

To convert our PDF to text, we will need to use pdfminer. Start by installing that:

pip install pdfminer

Once you install pdfminer, a command called pdf2txt.py is available, which will convert your PDF to file to text. Let’s do that now. We can run the following command to convert the PDF to text in the same folder so all of our materials are together:

pdf2txt.py -o en-final-table9.txt EN-FINAL\ Table\ 9.pdf

The first argument (-o en-final-table9.txt) is the text file we want to create. The second argument (EN-FINAL\ TABLE\ 9.pdf) is our PDF. Make sure to use the correct capitalization and capture any spaces in the filename. Spaces will need to be preceded with a backslash (\). This is referred to as escaping. Escaping tells the computer the space is part of whatever is being typed out.

After running this command, we have a text version of our PDF in a file called en-final-table9.txt.

Let’s read our new file into Python. Create a new script with the following code in the same folder as your previous script. Call it parse_pdf_text.py, or something similar that makes sense to you:

pdf_txt='en-final-table9.txt'openfile=open(pdf_txt,'r')forlineinopenfile:line

We can read in the text line by line and print each line, showing we have the table in text form.

Parsing PDFs Using pdfminer

Because PDFs are notoriously difficult to work with, we’ll be learning how to work through problems in our code and do some basic troubleshooting.

We want to start collecting the country names, because the country names are going to be the keys in our final dataset. If you open up your text file, you will find that the eighth line is the last line before the countries start. That line has the text and areas:

5 TABLE 9 CHILD PROTECTION 6 7 Countries 8 and areas 9 Afghanistan 10 Albania 11 Algeria 12 Andorra

If you look through the text document, you will see that this is a consistent pattern. So, we want to create a variable which acts as an on/off switch to start and stop the collection process when it hits the line and areas.

To accomplish this we will update the for loop to include a Boolean variable, which is a True/False variable. We want to set our Boolean to True when we hit the and areas lines:

country_line=Falseforlineinopenfile:ifline.startswith('and areas'):country_line=True

Sets

country_linetoFalse, because by default the line is not a country line.

Searches for a line that starts with and areas.

Sets

country_linetoTrue.

The next thing we need to find is when to set the Boolean back to False. Take a moment to look at the text file to identify the pattern. How do you know when the list of countries ends?

If you look at the follow excerpt, you will notice there is a blank line:

45 China 46 Colombia 47 Comoros 48 Congo 49 50 total 51 10 52 12

But how does Python recognize a blank line? Add a line to your script to print out the Python representation of the line (see “Formatting Data” for more on string formatting):

country_line=Falseforlineinopenfile:ifcountry_line:'%r'%lineifline.startswith('and areas'):country_line=True

If

country_lineisTrue, which it will be after the previous iteration of theforloop…

… then print out the Python representation of the line.

If you look at the output, you will notice that all the lines now have extra characters at the end:

45 'China \n' 46 'Colombia \n' 47 'Comoros \n' 48 'Congo \n' 49 '\n' 50 'total\n' 51 '10 \n' 52 '12 \n'

The \n is the symbol of the end of a line, or a newline character. This is what we will now use as the marker to turn off the country_line variable. If country_line is set to True but the line is equal to \n, our code should set country_line to False, because this line marks the end of the country names:

country_line=Falseforlineinopenfile:ifcountry_line:lineifline.startswith('and areas'):country_line=Trueelifcountry_line:ifline=='\n':country_line=False

If

country_lineisTrue, print out the line so we can see the country name. This comes first because we don’t want it after our and areas test; we only want to print the actual country names, not the and areas line.

If

country_lineisTrueand the line is equal to a newline character, setcountry_linetoFalse, because the list of countries has ended.

Now, when we run our code, we get what looks like all the lines with countries returned. This will eventually turn into our country list. Now, let’s look for the markers for the data we want to collect and do the same thing. The data we are looking for is the child labor and child marriage figures. We will begin with child labor data—we need total, male, and female numbers. Let’s start with the total.

We will follow the same pattern to find total child labor:

-

Create an on/off switch using

True/False. -

Look for the starter marker to turn it on.

-

Look for the ending marker to turn it off.

If you look at the text, you will see the starting marker for data is total. Look at line 50 in the text file you created to see the first instance:1

45 China 46 Colombia 47 Comoros 48 Congo 49 50 total 51 10 52 12

The ending marker is once again a newline or \n, which you can see on line 71:

68 6 69 46 70 3 71 72 26 y 73 5

Let’s add this logic to our code and check the results using print:

country_line=total_line=Falseforlineinopenfile:ifcountry_lineortotal_line:lineifline.startswith('and areas'):country_line=Trueelifcountry_line:ifline=='\n':country_line=Falseifline.startswith('total'):total_line=Trueeliftotal_line:ifline=='\n':total_line=False

Sets

total_linetoFalse.

If

country_lineortotal_lineis set toTrue, outputs the line so we can see what data we have.

Checks where

total_linestarts and settotal_linetoTrue. The code following this line follows the same construction we used for thecountry_linelogic.

At this point, we have some code redundancy. We are repeating some of the same code, just with different variables or on and off switches. This opens up a conversation about how to create non-redundant code. In Python, we can use functions to perform repetitive actions. That is, instead of manually performing those sets of actions line by line in our code, we can put them in a function and call the function to do it for us. If we need to test each line of a PDF, we can use functions instead.

Note

When first writing functions, figuring out where to place them can be confusing. You need to write the code for the function before you want to call the function. This way Python knows what the function is supposed to do.

We will name the function we are writing turn_on_off, and we will set it up to receive up to four arguments:

-

lineis the line we are evaluating. -

statusis a Boolean (TrueorFalse) representing whether it is on or off. -

startis what we are looking for as the start of the section—this will trigger the on orTruestatus. -

endis what we are looking for as the end of the section—this will trigger the off orFalsestatus.

Update your code and add the shell for the function above your for loop. Do not forget to add a description of what the function does—this is so when you refer back to the function later, you don’t have to try to decipher it. These descriptions are called docstrings:

defturn_on_off(line,status,start,end='\n'):""" This function checks to see if a line starts/ends with a certainvalue. If the line starts/ends with that value, the status is set to on/off (True/False). """returnstatuscountry_line=total_line=Falseforlineinopenfile:.....

This line begins the function and will take up to four arguments. The first three,

line,status, andstart, are required arguments—that is, they must be provided because they have no default values. The last one,end, has a default value of a newline character, as that appears to be a pattern with our file. We can override the default value by passing a different value when we call our function.

Always write a description (or docstring) for your function, so you know what it does. It doesn’t have to be perfect. Just make sure you have something. You can always update it later.

The

returnstatement is the proper way to exit a function. In this case, we are going to returnstatus, which will beTrueorFalse.

Now, let’s move the code from our for loop into the function. We want to replicate the logic we had with country_line in our new turn_on_off function:

defturn_on_off(line,status,start,end='\n'):""" This function checks to see if a line starts/ends with a certain value. If the line starts/ends with that value, the status is set to on/off (True/False). """ifline.startswith(start):status=Trueelifstatus:ifline==end:status=Falsereturnstatus

Replaces what we are searching for on the starting line with the

startvariable.

Replaces the end text we used with the

endvariable.

Returns the status based on the same logic (

endmeansFalse,startmeansTrue).

Let’s now call the function in our for loop, and check out what our script looks like all together thus far:

pdf_txt='en-final-table9.txt'openfile=open(pdf_txt,"r")defturn_on_off(line,status,start,end='\n'):""" This function checks to see if a line starts/ends with a certain value. If the line starts/ends with that value, the status is set to on/off (True/False). """ifline.startswith(start):status=Trueelifstatus:ifline==end:status=Falsereturnstatuscountry_line=total_line=Falseforlineinopenfile:ifcountry_lineortotal_line:'%r'%linecountry_line=turn_on_off(line,country_line,'and areas')total_line=turn_on_off(line,total_line,'total')

In Python syntax, a series of

=symbols means we are assigning each of the variables listed to the final value. This line assigns bothcountry_lineandtotal_linetoFalse.

We want to still keep track of our lines and the data they hold when we are on. For this, we are employing

or. A Pythonorsays if one or the other is true, do the following. This line says if eithercountry_lineortotal_lineisTrue, print the line.

This calls the function for countries. The

country_linevariable catches the returned status that the function outputs and updates it for the nextforloop.

This calls the function for totals. It works the same as the previous line for country names.

Let’s start to store our countries and totals in lists. Then we will take those lists and turn them into a dictionary, where the country will be the key and the total will be the value. This will help us troubleshoot to see if we need to clean up our data.

Here’s the code to create the two lists:

countries=[]totals=[]country_line=total_line=Falseforlineinopenfile:ifcountry_line:countries.append(line)eliftotal_line:totals.append(line)country_line=turn_on_off(line,country_line,'and areas')total_line=turn_on_off(line,total_line,'total')

Creates empty countries list.

Creates empty totals list.

Note that we’ve removed the

if country_line or total_linestatement. We will break this out separately below.

If it’s a country line, this line adds the country to the country list.

This line collects totals, the same as we did with countries.

We are going to combine the totals and countries by “zipping” the two datasets. The zip function takes an item from each list and pairs them together until all items are paired. We can then convert the zipped list to a dictionary by passing it to the dict function.

Add the following to the end of the script:

importpprinttest_data=dict(zip(countries,totals))pprint.pprint(test_data)

Imports the

pprintlibrary. This prints complex data structures in a way that makes them easy to read.

Creates a variable called

test_data, which will be the countries and totals zipped together and then turned into a dictionary.

Passes

test_datato thepprint.pprint()function to pretty print our data.

If you run the script now, you will get a dictionary that looks like this:

{'\n': '49 \n',

' \n': '\xe2\x80\x93 \n',

' Republic of Korea \n': '70 \n',

' Republic of) \n': '\xe2\x80\x93 \n',

' State of) \n': '37 \n',

' of the Congo \n': '\xe2\x80\x93 \n',

' the Grenadines \n': '60 \n',

'Afghanistan \n': '10 \n',

'Albania \n': '12 \n',

'Algeria \n': '5 y \n',

'Andorra \n': '\xe2\x80\x93 \n',

'Angola \n': '24 x \n',

'Antigua and Barbuda \n': '\xe2\x80\x93 \n',

'Argentina \n': '7 y \n',

'Armenia \n': '4 \n',

'Australia \n': '\xe2\x80\x93 \n',

......

At this point, we are going to do some cleaning. This will be explained in greater detail in Chapter 7. For now, we need to clean up our strings, as they are very hard to read. We are going to do this by creating a function to clean up each line. Place this function above the for loop, near your other function:

defclean(line):""" Cleans line breaks, spaces, and special characters from our line. """line=line.strip('\n').strip()line=line.replace('\xe2\x80\x93','-')line=line.replace('\xe2\x80\x99','\'')returnline

Strips

\noff of the line and reassigns the output tolineso nowlineholds the cleaned version

Replaces special character encodings

Returns our newly cleaned string

Note

In the cleaning we just did, we could combine method calls like this:

line=line.strip('\n').strip().replace('\xe2\x80\x93','-').replace('\xe2\x80\x99s','\'')

However, well-formatted Python code lines should be no greater than 80 characters in length. This is a recommendation, not a rule, but keeping your lines restricted in length allows your code to be more readable.

Let’s apply the clean_line function in our for loop:

forlineinopenfile:ifcountry_line:countries.append(clean(line))eliftotal_line:totals.append(clean(line))

Now if we run our script, we get something that looks closer to what we are aiming for:

{'Afghanistan':'10','Albania':'12','Algeria':'5 y','Andorra':'-','Angola':'24 x','Antigua and Barbuda':'-','Argentina':'7 y','Armenia':'4','Australia':'-','Austria':'-','Azerbaijan':'7 y',...

If you skim the list, you will see our approach is not adequately parsing all of the data. We need to figure out why this is happening.

It looks like countries with names spread over more than one line are separated into two records. You can see with this Bolivia: we have records reading 'Bolivia (Plurinational': '', and 'State of)': '26 y',.

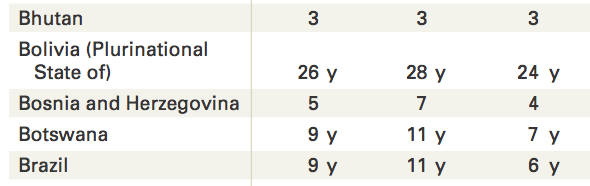

The PDF itself can be used as a visual reference to show you how the data should be organized. You can see these lines in the PDF, as shown in Figure 5-2.

Figure 5-2. Bolivia in the PDF

Warning

PDFs can be rabbit holes. Each PDF you process will require its own finesse. Because we are only parsing this PDF once, we are doing a lot of hand-checking. If this was a PDF we needed to parse on a regular basis, we would want to closely identify patterns over time and programmatically account for those, along with building checks and testing our code to ensure our import is accurate.

There are a couple of ways to approach this problem. We could try to create a placeholder to check for blank total lines and combine those with the following data lines. Another solution is to keep track of which countries have records spanning more than one line. We will try the second approach, as our dataset isn’t too large.

We will create a list of the first lines for each multiline country record and use this list to check each line in our script. You will want to put this list before your for loop. Often, reference items are put near the top of the script so they are easy to find and change as needed.

Let’s add Bolivia (Plurinational to a list of double-lined countries:

double_lined_countries=['Bolivia (Plurinational',]

Now we need to update our for loop to check if the previous line is in the double_lined_countries list, and, if so, combine that line with the current line. To do so, we will create a previous_line variable. Then, we will populate the previous_line variable at the end of the for loop. Only then will we be able to combine the rows when the code hits the next iteration of the loop:

countries=[]totals=[]country_line=total_line=Falseprevious_line=''forlineinopenfile:ifcountry_line:countries.append(clean(line))eliftotal_line:totals.append(clean(line))country_line=turn_on_off(line,country_line,'and areas')total_line=turn_on_off(line,total_line,'total')previous_line=line

Creates the

previous_linevariable and sets it to an empty string.

Populates the

previous_linevariable with the current line at the end of theforloop.

Now we have a previous_line variable and we can check to see if the previous_line is in double_lined_countries so we know when to combine the previous line with the current line. Furthermore, we will want to add the new combined line to the countries list. We also want to make sure we do not add the line to the countries list if the first part of the name is in the double_lined_countries list.

Let’s update our code to reflect these changes:

ifcountry_line:ifprevious_lineindouble_lined_countries:line=''.join([clean(previous_line),clean(line)])countries.append(line)eliflinenotindouble_lined_countries:countries.append(clean(line))

We want the logic in the

if country_linesection because it is only relevant to country names.

If the

previous_lineis in thedouble_lined_countrieslist, this line joins theprevious_linewith the current line and assigns the combined lines to thelinevariable.join, as you can see, binds a list of strings together with the preceding string. This line uses a space as the joining character.

If the line is not in the

double_lined_countrieslist, then the following line adds it to the countries list. Here, we utilizeelif, which is Python’s way of sayingelse if. This is a nice tool to use if you want to include a different logic flow thanif - else.

If we run our script again, we see 'Bolivia (Plurinational State of)' is now combined. Now we need to make sure we have all the countries. We will do this manually because our dataset is small, but if you had a larger dataset, you would automate this.

Look at the PDF in a PDF viewer to identify all the double-lined country names:

Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Democratic Republic of the Congo Lao People’s Democratic Republic Micronesia (Federated States of) Saint Vincent and the Grenadines The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia United Republic of Tanzania Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)

We know this is likely not how Python sees it, so we need to print out the countries as Python sees them and add those to the list:

ifcountry_line:'%r'%lineifprevious_lineindouble_lined_countries:

Run your script to populate the double_lined_countries list with the Python representation:

double_lined_countries=['Bolivia (Plurinational\n','Democratic People\xe2\x80\x99s\n','Democratic Republic\n','Micronesia (Federated\n',#... uh oh.]

We are missing Lao People’s Democratic Republic from our output, but it’s on two lines in the PDF. Let’s go back to the text version of the PDF and see what happened.

After looking at the text, can you identify the issue? Look at the turn_on_off function. How does that work in relation to how this text is written?

The problem turns out to be a blank line or \n right after the and areas we were looking for as a marker. If you look at the text file that we created, you will see the stray blank line on line number 1343:

... 1341 Countries 1342 and areas 1343 1344 Iceland 1345 India 1346 Indonesia 1347 Iran (Islamic Republic of) ...

That means our function didn’t work. There are multiple ways we could approach this problem. For this example, we could try adding in more logic to make sure our on/off code works as intended. When we start to collect countries, there should be at least one country collected before we turn off the country collection. If no countries have been collected, then we should not turn off the collecting action. We can also use the previous line as a way to solve this problem. We can test the previous line in our on/off function and ensure it’s not in a list of special lines.

In case we come across any other anomalies, let’s set up this special line:

defturn_on_off(line,status,start,prev_line,end='\n'):""" This function checks to see if a line starts/ends with a certain value. If the line starts/ends with that value, the status is set to on/off (True/False) as long as the previous line isn't special. """ifline.startswith(start):status=Trueelifstatus:ifline==endandprev_line!='and areas':status=Falsereturnstatus

If the line is equal to

endand the previous line is not equal to and areas, then we can turn data collection off. Here, we are using!=which is Python’s way of testing “not equal.” Similar to==,!=returns a Boolean value.

You will also need to update your code to pass the previous line:

country_line = turn_on_off(line, country_line, previous_line, 'and areas')

total_line = turn_on_off(line, total_line, previous_line, 'total')

Let’s go back to the original task we were working on—creating our list of double-lined countries so that we can make sure to collect both lines. We left off here:

double_lined_countries=['Bolivia (Plurinational\n','Democratic People\xe2\x80\x99s\n','Democratic Republic\n',]

Looking at the PDF, we see the next one is Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Let’s start adding from there by looking back at our script output:

double_lined_countries=['Bolivia (Plurinational\n','Democratic People\xe2\x80\x99s\n','Democratic Republic\n','Lao People\xe2\x80\x99s Democratic\n','Micronesia (Federated\n','Saint Vincent and\n','The former Yugoslav\n','United Republic\n','Venezuela (Bolivarian\n',]

If your list looks like the preceding list, when you run the script, you should have an output that pulls in the country names split over two lines. Make sure to add a print statement to the end of your script to view the country list:

importpprintpprint.pprint(countries)

Now that you have spent a bit of time with the country list, can you think of another approach to solve this issue? Take a look at a few of the second lines:

' Republic of Korea \n' ' Republic \n' ' of the Congo \n'

What do they have in common? They start with spaces. Writing code to check whether a line begins with three spaces would be more efficient. However, taking the approach we did allowed us to discover we were losing part of our dataset as it was being collected. As your coding skills develop, you will learn to find different ways to approach the same problem and determine which works best.

Let’s check to see how our total numbers line up with our countries. Update the pprint statement to match the following:

importpprintdata=dict(zip(countries,totals))pprint.pprint(data)

Zips the countries and totals lists together by calling

zip(countries, totals). This turns them into a tuple. We then change the tuple into a dictionary, or dict (for easier reading), by passing it to thedictfunction.

Prints out the data variable we just created.

What you will see returned is a dictionary where the country names are the keys and the totals are the values. This is not our final data format; we are just doing this to see our data so far. The result should look like this:

{'':'-','Afghanistan':'10','Albania':'12','Algeria':'5 y','Andorra':'-','Angola':'24 x',...}

If you check this again alongside the PDF, you will notice it falls apart right at the point of the first country on a double line. The numbers pulled in are the ones from the Birth registration column:

{...'Bolivia (Plurinational State of)':'','Bosnia and Herzegovina':'37','Botswana':'99','Brazil':'99',...}

If you look at the text version of the PDF, you will notice there is a gap between the numbers when the country is on a double line:

6 46 3 26 y 5 9 y

In the same way we accounted for this in the country name collection, we need to account for this in data collection. If we have a blank space in our data lines, we need to make sure we don’t collect it—that way, we only collect the data that matches the countries we’ve been collecting. Update your code to the following:

forlineinopenfile:ifcountry_line:'%r'%lineifprevious_lineindouble_lined_countries:line=''.join([clean(previous_line),clean(line)])countries.append(line)eliflinenotindouble_lined_countries:countries.append(clean(line))eliftotal_line:iflen(line.replace('\n','').strip())>0:totals.append(clean(line))country_line=turn_on_off(line,country_line,previous_line,'and areas')total_line=turn_on_off(line,total_line,previous_line,'total')previous_line=line

We know from experience the PDF uses newlines as blank lines. On this line, the code replaces newlines with nothing and strips whitespace to clean it. Then this code tests whether the string still has a length greater than zero. If so, we know there is data and we can add it to our data (totals) list.

After running our updated code, things fall apart again at our first double line. This time we are pulling in those Birth registration numbers again, aligned with our first double-lined country. All the following values are also incorrect. Let’s go back to the text file and figure out what is happening. If you look at the numbers in that column in the PDF, you can find the pattern in the text version of the PDF starting on line number 1251:

1250 1251 total 1252 – 1253 5 x 1254 26 1255 – 1266 –

If you look closely, you will notice the title of the Birth registration column ends in total:

266 Birth 267 registration 268 (%)+ 269 2005–2012* 270 total 271 37 272 99

Right now the function collecting totals is looking for total, so this column is getting picked up before we even get to the next line of countries. We also see that the Violent discipline (%) column has a label for total with a blank line above it. This follows the same pattern as the total we want to collect.

Encountering back-to-back bugs likely means the problem exists in the larger logic you’ve constructed. Because we started our script using these on/off switches, to fix the underlying problem we would need to rework the logic there. We’d need to figure out how to best determine the right column, maybe by collecting column names and sorting them. We might need to determine a way to see if the “page” has changed. If we keep quick-fixing the solution, we will likely run into more errors.

Tip

Only spend as much time on a script as you think you need to invest. If you are trying to build a sustainable process you can run on a large dataset multiple times over a long period, you are going to want to take the time to carefully consider all of the steps.

This is the process of programming—write code, debug, write code, debug. No matter how experienced a computer programmer you are, there will be moments when you introduce errors in your code. When learning to code, these moments can be demoralizing. You might think, “Why isn’t this working for me? I must not be good at this.” But that’s not true; programming takes practice, like anything else.

At this point, it’s clear our current process isn’t working. Based on what we now know about the text file, we can tell we began with a false notion that the file defines the beginning and end of each section using text. We could begin again with this file, starting at a new point; however, we want to explore some other ways of problem solving to fix the errors and get the data we want.

Learning How to Solve Problems

There are a variety of exercises you can try to parse the PDF script while also challenging your ability to write Python. First, let’s review our code so far:

pdf_txt='en-final-table9.txt'openfile=open(pdf_txt,"r")double_lined_countries=['Bolivia (Plurinational\n','Democratic People\xe2\x80\x99s\n','Democratic Republic\n','Lao People\xe2\x80\x99s Democratic\n','Micronesia (Federated\n','Saint Vincent and\n','The former Yugoslav\n','United Republic\n','Venezuela (Bolivarian\n',]defturn_on_off(line,status,prev_line,start,end='\n',count=0):"""This function checks to see if a line starts/ends with a certainvalue. If the line starts/ends with that value, the status isset to on/off (True/False) as long as the previous line isn't special."""ifline.startswith(start):status=Trueelifstatus:ifline==endandprev_line!='and areas':status=Falsereturnstatusdefclean(line):"""Clean line breaks, spaces, and special characters from our line."""line=line.strip('\n').strip()line=line.replace('\xe2\x80\x93','-')line=line.replace('\xe2\x80\x99','\'')returnlinecountries=[]totals=[]country_line=total_line=Falseprevious_line=''forlineinopenfile:ifcountry_line:ifprevious_lineindouble_lined_countries:line=' '.join([clean(previous_line),clean(line)])countries.append(line)eliflinenotindouble_lined_countries:countries.append(clean(line))eliftotal_line:iflen(line.replace('\n','').strip())>0:totals.append(clean(line))country_line=turn_on_off(line,country_line,previous_line,'and areas')total_line=turn_on_off(line,total_line,previous_line,'total')previous_line=lineimportpprintdata=dict(zip(countries,totals))pprint.pprint(data)

There are multiple solutions to the problems we are facing; we’ll walk through some of them in the following sections.

Exercise: Use Table Extraction, Try a Different Library

After scratching our heads at the perplexities illustrated by this PDF-to-text conversion, we went searching for alternatives to using pdfminer for table extraction. We came across pdftables, which is a presumed-defunct library (the last update from the original maintainers was more than two years ago).

We installed the necessary libraries, which can be done simply by running pip install pdftables and pip install requests. The maintainers didn’t keep all the documentation up to date, so certain examples in the documentation and README.md were blatantly broken. Despite that, we did find one “all in one” function we were able to use to get at our data:

frompdftablesimportget_tablesall_tables=get_tables(open('EN-FINAL Table 9.pdf','rb'))all_tables

Let’s start a new file for our code and run it (pdf_table_data.py). You should see a whirlwind of data that looks like the data we want to extract. You will notice not all of the headers convert perfectly, but it seems every line is contained in the all_tables variable. Let’s take a closer look to extract our headers, data columns, and notes.

You might have noticed all_tables is a list of lists (or a matrix). It has every row, and it also has rows of rows. This probably is a good idea in table extraction, because that’s essentially what a table is—columns and rows. The get_tables function returns each page as its own table, and the each of those tables has a list of rows with a contained list of columns.

Our first step is to find the titles we can use for our columns. Let’s try viewing the first few rows to see if we can identify the one containing our column headers:

all_tables[0][:6]

Here we are just looking at the first page’s first six rows:

...[u'',u'',u'',u'',u'',u'',u'Birth',u'Female',u'genital mutila',u'tion/cutting (%)+',u'Jus',u'tification of',u'',u'',u'E'],[u'',u'',u'Child labour (%',u')+',u'Child m',u'arriage (%)',u'registration',u'',u'2002\u201320',u'12*',u'wife',u'beating (%)',u'',u'Violent disciplin',u'e (%)+ 9'],[u'Countries and areas',u'total',u'2005\u20132012*male',u'female',u'2005married by 15',u'\u20132012*married by 18',u'(%)+ 2005\u20132012*total',u'prwomena',u'evalencegirlsb',u'attitudessupport for thepracticec',u'2male',u'005\u20132012*female',u'total',u'2005\u20132012*male',u'female'],...

We can see the titles are included in the first three lists, and they are messy. However, we can also see from our print statement that the rows are actually fairly clean. If we manually set up our titles by comparing them to the PDF, as shown here, we might have a clean dataset:

headers=['Country','Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) total','Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) male','Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) female','Child Marriage 2005-2012 (%) married by 15','Child Marriage 2005-2012 (%) married by 18','Birth registration 2005-2012 (%)','Female Genital mutilation 2002-2012 (prevalence), women','Female Genital mutilation 2002-2012 (prevalence), girls','Female Genital mutilation 2002-2012 (support)','Justification of wife beating 2005-2012 (%) male','Justification of wife beating 2005-2012 (%) female','Violent discipline 2005-2012 (%) total','Violent discipline 2005-2012 (%) male','Violent discipline 2005-2012 (%) female']fortableinall_tables:forrowintable:zip(headers,row)

Adds all of our headers, including the country names, to one list. We can now zip this list with rows to have our data aligned.

Uses the

zipmethod to zip together the headers with each row.

We can see from the output of our code that we have matches for some of the rows, but there are also many rows that are not country rows (similar to what we saw earlier when we found extra spaces and newlines in our table).

We want to programmatically solve this problem with some tests based on what we’ve learned so far. We know some of the countries span more than one row. We also know the file uses dashes (-) to show missing data, so completely empty rows are not actual data rows. We know from our previous print output that the data starts for each page on the fifth row. We also know the last row we care about is Zimbabwe. Let’s combine our knowledge and see what we get:

fortableinall_tables:forrowintable[5:]:ifrow[2]=='':row

Isolates only the rows for each page we want, meaning only the slice from the fifth index onward

If there is data that looks null, prints out the row to see what’s in that row

When you run the code, you’ll see there are some random blank rows scattered throughout the list that aren’t part of the country names. Maybe this is the cause of our problems in the last script. Let’s try to just get the country names put together and skip other blank rows. Let’s also add in the test for Zimbabwe:

first_name=''fortableinall_tables:forrowintable[5:]:ifrow[0]=='':continueifrow[2]=='':first_name=row[0]continueifrow[0].startswith(''):row[0]='{} {}'.format(first_name,row[0])zip(headers,row)ifrow[0]=='Zimbabwe':break

If the data row is missing index 0, it has no country name and is a blank row. The next line skips it using

continue, which is a Python keyword that tells theforloop to go to the next iteration.

If the data row is missing index 2, we know this is probably the first part of a country name. This line saves the first part of the name in a variable

first_name. The next line moves on to the next row of data.

If the data row starts with spaces, we know it’s the second part of a country name. We want to put the name back together again.

If we are right in our hypothesis, we can match these things by printing out the results for human review. This line prints out each iteration so we can see them.

When we reach Zimbabwe, this line breaks out of our

forloop.

Most of the data looks good, but we are still seeing some anomalies. Take a look here:

[('Country',u'80 THE STATE OF T'),('Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) total',u'HE WOR'),('Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) male',u'LD\u2019S CHILDRE'),('Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) female',u'N 2014'),('Child Marriage 2005-2012 (%) married by 15',u'IN NUMBER'),('Child Marriage 2005-2012 (%) married by 18',u'S'),('Birth registration 2005-2012 (%)',u''),.....

We see the line number is at the beginning of the section we thought was the country name. Do you know any countries that have numbers in their name? We sure don’t! Let’s put in a test for numbers and see if we can lose the bad data. We also noticed our two-line countries are not properly mapping. From the looks of it, the pdftables import autocorrected for spaces at the beginning of lines. How kind! Now we should add in a test and see if the very last line has a first_name or not:

frompdftablesimportget_tablesimportpprintheaders=['Country','Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) total','Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) male','Child Labor 2005-2012 (%) female','Child Marriage 2005-2012 (%) married by 15','Child Marriage 2005-2012 (%) married by 18','Birth registration 2005-2012 (%)','Female Genital mutilation 2002-2012 (prevalence), women','Female Genital mutilation 2002-2012 (prevalence), girls','Female Genital mutilation 2002-2012 (support)','Justification of wife beating 2005-2012 (%) male','Justification of wife beating 2005-2012 (%) female','Violent discipline 2005-2012 (%) total','Violent discipline 2005-2012 (%) male','Violent discipline 2005-2012 (%) female']all_tables=get_tables(open('EN-FINAL Table 9.pdf','rb'))first_name=Falsefinal_data=[]fortableinall_tables:forrowintable[5:]:ifrow[0]==''orrow[0][0].isdigit():continueelifrow[2]=='':first_name=row[0]continueiffirst_name:row[0]=u'{} {}'.format(first_name,row[0])first_name=Falsefinal_data.append(dict(zip(headers,row)))ifrow[0]=='Zimbabwe':breakpprint.pprint(final_data)

Manipulates the country name entry in the row if it has a

first_name

Sets

first_nameback toFalse, so our next iteration operates properly

We now have our completed import. You’ll need to further manipulate the data if you want to match the exact structure we had with our Excel import, but we were able to preserve the data in our rows from the PDF.

Warning

pdftables is not actively supported, and the people who developed it now only offer a new product to replace it as a paid service. It’s dangerous to rely on unsupported code, and we can’t depend on pdftables to be around and functional forever.2 Part of belonging to

the open source community, however, is giving back; so we encourage you to find good projects and help out by contributing and publicizing them in the hopes that projects like pdftables stay open source and continue to grow and thrive.

Next, we’ll take a look at some other options for parsing PDF data, including cleaning it by hand.

Exercise: Clean the Data Manually

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room. Throughout this chapter, you might have wondered why we haven’t simply edited the text version of the PDF for easier processing. You could do that—it’s one of many ways to solve these problems. However, we challenge you to process this file using Python’s many tools. You won’t always be able to edit PDFs manually.

If you have a difficult PDF or other file type presenting issues, it’s possible extraction to a text file and some hand–data wrangling are in order. In those cases, it’s a good idea to estimate how much time you’re willing to spend on manual manipulation and hold yourself to that estimate.

For more on data cleanup automation, check out Chapter 8.

Exercise: Try Another Tool

When we first started to look for a Python library to use for parsing PDFs, we found slate—which looked easy to use but required some custom code—by searching the Web to see what other people were using for the task.

To see what else was out there, instead of searching for “parsing pdfs python,” we tried searching for “extracting tables from pdf,” which gave us more distinct solutions for the table problem (including a blog post reviewing several tools).

With a small PDF like the one we are using, we could try Tabula. Tabula isn’t always going to be the solution, but it has some good capabilities.

To get started with Tabula:

-

Launch the application by double-clicking on it; this will launch the tool in your browser.

-

Upload the child labor PDF.

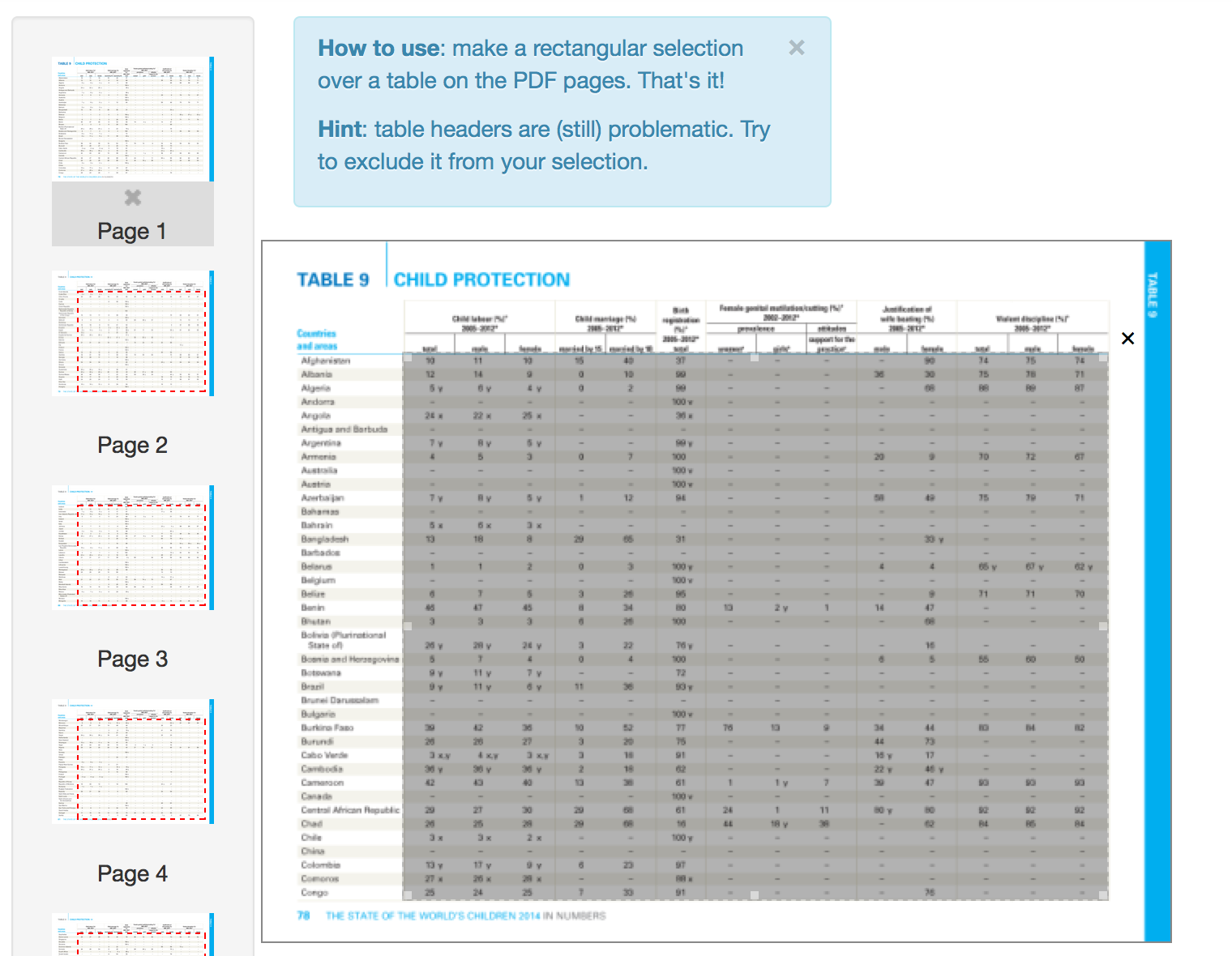

From here, you need to adjust the selection of the content Tabula tries to grab. Getting rid of the header rows enables Tabula to identify the data on every page and automatically highlight it for extraction. First, select the tables you are interested in (see Figure 5-3).

Figure 5-3. Select tables in Tabula

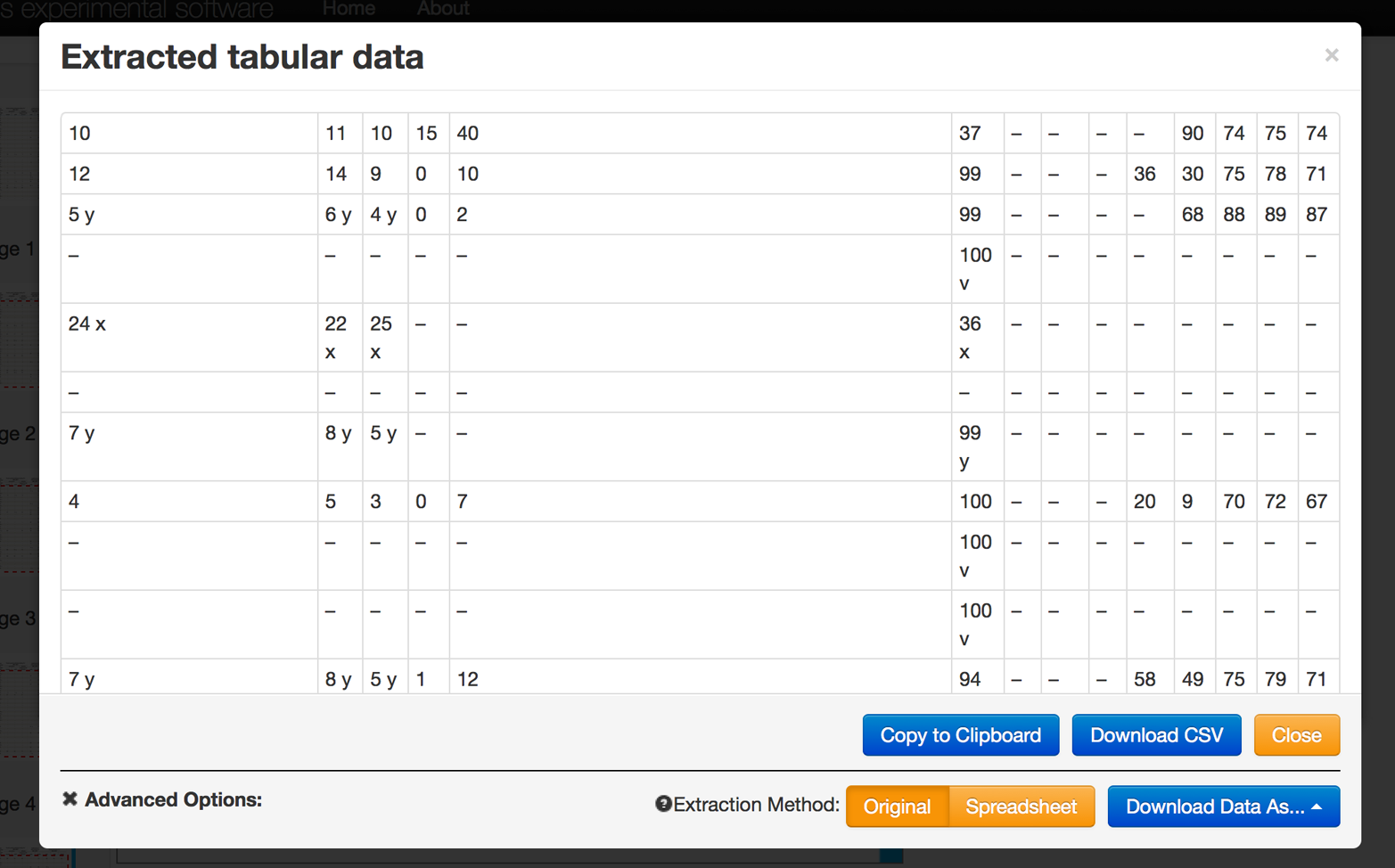

Next, download the data (see Figure 5-4).

Figure 5-4. Download screen in Tabula

Click “Download CSV” and you will get something that looks like Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5. Exacted data in CSV form

It’s not perfect, but the data is cleaner than we received from pdfminer.

The challenge will be to take the CSV you created with Tabula and parse it. It is different from the other CSVs we parsed (in Chapter 3) and a little messier. If you get stumped, put it aside and come back to it after reading Chapter 7.

Uncommon File Types

So far in this book, we have covered CSV, JSON, XML, Excel, and PDF files. Data in PDFs can be difficult to parse, and you may think the world of data wrangling can’t get any worse—sadly, it can.

The good news is, there’s probably no problem you will face that someone hasn’t solved before. Remember, asking the Python or greater open source communities for help and tips is always a great solution, even if you come away learning you should keep looking for more accessible datasets.

You may encounter problems if the data has the following attributes:

-

The file was generated on an old system using a an uncommon file type.

-

The file was generated by a proprietary system.

-

The file isn’t launchable in a program you have.

Solving problems related to uncommon file types is simply a matter of building on what you have already learned:

-

Identify the file type. If this is not easily done through the file extension, then use the

python-magiclibrary. -

Search the Internet for “how to parse <file extension> in Python,” replacing “<file extension>” with the actual file extension.

-

If there is no obvious solution, try opening the file in a text editor or reading the file with Python’s

openfunction. -

If the characters look funky, read up on Python encoding. If you are just getting started with Python character encoding, then watch the PyCon 2014 talk “Character encoding and Unicode in Python”.

Summary

PDF and other hard-to-parse formats are the worst formats you will encounter. When you find data in one of these formats, the first thing you should do is see if you can acquire the data in another format. With our example, the data we received in the CSV format was more precise because the numbers were rounded for the PDF charts. The more raw the format, the more likely it is to be accurate and easy to parse with code.

If it is not possible to get the data in another format, then you should try the following process:

-

Identify the data type.

-

Search the Internet to see how other folks have approached the problem. Is there a tool to help import the data?

-

Select the tool that is most intuitive to you. If it’s Python, then select the library that makes the most sense to you.

-

Try to convert the data to a an easier to use format.

In this chapter, we learned about the libraries and tools in Table 5-1.

| Library or tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Parses the PDF into a string in memory every time the script is run |

|

Converts the PDF into text, so you can parse the text file |

|

Uses |

Tabula |

Offers an interface to extract PDF data into CSV format |

Besides learning about new tools, we also learned a few new Python programming concepts, which are summarized in Table 5-2.

| Concept | Purpose |

|---|---|

Escaping tells the computer there is a space or special character in the file path or name by preceding it with a backslach ( |

|

|

The |

In the process of writing |

|

Functions in Python are used to execute a piece of code. By making reusable code into functions, we can avoid repeating ourselves. |

|

|

|

A tuple is like a list, but immutable, meaning it cannot be updated. To update a tuple, it would have to be stored as a new object. |

|

|

In the next chapter, we’ll talk about data acquisition and storage. This will provide more insight on how to acquire alternative data formats. In Chapters 7 and 8, we cover data cleaning, which will also help in the complexity of processing PDFs.

1 Your text editor likely has an option to turn on line numbers, and might even have a shortcut to “hop” to a particular line number. Try a Google search if it’s not obvious how to use these features.

2 It does seem there are some active GitHub forks that may be maintained and supported. We encourage you to keep an eye on them for your PDF table parsing needs.