Applying Commands in a Script

Combining a series of edits in a script can have unexpected results. You might not think of the consequences one edit can have on another. New users typically think that sed applies an individual editing command to all lines of input before applying the next editing command. But the opposite is true. Sed applies the entire script to the first input line before reading the second input line and applying the editing script to it. Because sed is always working with the latest version of the original line, any edit that is made changes the line for subsequent commands. Sed doesn’t retain the original. This means that a pattern that might have matched the original input line may no longer match the line after an edit has been made.

Let’s look at an example that uses the substitute command. Suppose someone quickly wrote the following script to change “pig” to “cow” and “cow” to “horse”:

s/pig/cow/g s/cow/horse/g

What do you think happened? Try it on a sample file. We’ll discuss what happened later, after we look at how sed works.

The Pattern Space

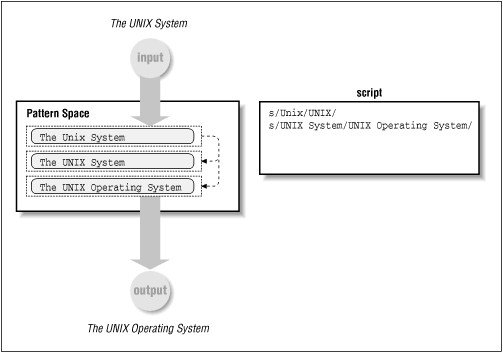

Sed maintains a pattern space, a workspace or temporary buffer where a single line of input is held while the editing commands are applied.[1] The transformation of the pattern space by a two-line script is shown in Figure 4.1. It changes “The Unix System” to “The UNIX Operating System.”

Initially, the pattern space contains a copy of a single input line. In Figure 4.1, that line is “The Unix System.” The normal flow through the script is to execute each command on that line until the end of the script is reached. The first command in the script is applied to that line, changing “Unix” to “UNIX.” Then the second command is applied, changing “UNIX System” to “UNIX Operating System.”[2] Note that the pattern for the second substitute command does not match the original input line; it matches the current line as it has changed in the pattern space.

When all the instructions have been applied, the current line is output and the next line of input is read into the pattern space. Then all the commands in the script are applied to that line.

As a consequence, any sed command might change the contents of the pattern space for the next command. The contents of the pattern space are dynamic and do not always match the original input line. That was the problem with the sample script at the beginning of this chapter. The first command would change “pig” to “cow” as expected. However, when the second command changed “cow” to “horse” on the same line, it also changed the “cow” that had been a “pig.” So, where the input file contained pigs and cows, the output file has only horses!

This mistake is simply a problem of the order of the commands in the script. Reversing the order of the commands—changing “cow” into “horse” before changing “pig” into “cow”—does the trick.

s/cow/horse/g s/pig/cow/g

Some sed commands change the flow through the script, as we will see in subsequent chapters. For example, the N command reads another line into the pattern space without removing the current line, so you can test for patterns across multiple lines. Other commands tell sed to exit before reaching the bottom of the script or to go to a labeled command. Sed also maintains a second temporary buffer called the hold space. You can copy the contents of the pattern space to the hold space and retrieve them later. The commands that make use of the hold space are discussed in Chapter 6.

[1] One advantage of the one-line-at-a-time design is that sed can read very large files without any problems. Screen editors that have to read the entire file into memory, or some large portion of it, can run out of memory or be extremely slow to use in dealing with large files.

[2] Yes, we could have changed “Unix System” to “UNIX Operating System” in one step. However, the input file might have instances of “UNIX System” as well as “Unix System.” So by changing “Unix” to “UNIX” we make both instances consistent before changing them to “UNIX Operating System.”