That’s an Expression

You are probably familiar with the kinds of expressions that a calculator interprets. Look at the following arithmetic expression:

2 + 4

“Two plus four” consists of several constants or literal values and an operator. A calculator program must recognize, for instance, that “2” is a numeric constant and that the plus sign represents an operator, not to be interpreted as the “+” character.

An expression tells the computer how to produce a result. Although it is the result of “two plus four” that we really want, we don’t simply tell the computer to return a six. We instruct the computer to evaluate the expression and return a value.

An expression can be more complicated than “2 + 4”; in fact, it might consist of multiple simple expressions, such as the following:

2 + 3 * 4

A calculator normally evaluates an expression from left to right. However, certain operators have precedence over others: that is, they will be performed first. Thus, the above expression will evaluate to 14 and not 20 because multiplication takes precedence over addition. Precedence can be overridden by placing the simple expression in parentheses. Thus, “(2 + 3) * 4” or “the sum of two plus three times four” will evaluate to 20. The parentheses are symbols that instruct the calculator to change the order in which the expression is evaluated.

A regular expression, by contrast, describes a pattern or sequence of characters. Concatenation is the basic operation implied in every regular expression. That is, a pattern matches adjacent characters. Look at the following regular expression:

ABE

Each literal character is a regular expression that matches only that single character. This expression describes an “A followed by a B then followed by an E” or simply “the string ABE”. The term “string” means each character concatenated to the one preceding it. That a regular expression describes a sequence of characters can’t be emphasized enough. (Novice users are inclined to think in higher-level units such as words, and not individual characters.) Regular expressions are case-sensitive; “A” does not match “a”.[1]

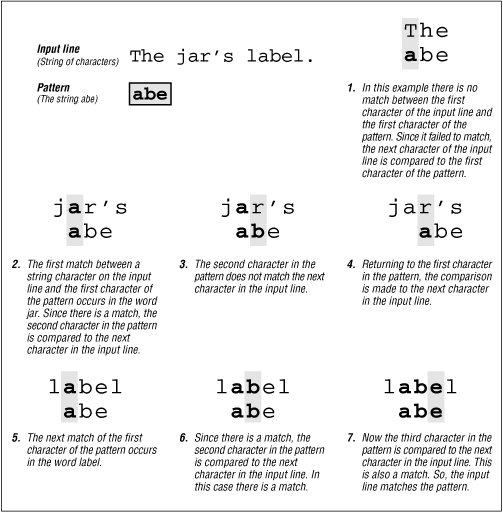

Programs such as grep that accept regular expressions must first evaluate the syntax of the regular expression to produce a pattern. They then read the input line-by-line trying to match the pattern. An input line is a string, and to see if a string matches the pattern, a program compares the first character in the string to the first character of the pattern. If there is a match, it compares the second character in the string to the second character of the pattern. Whenever it fails to make a match, it goes back and tries again, beginning one character later in the string. Figure 3.1 illustrates this process, trying to match the pattern “abe” on an input line.

A regular expression is not limited to literal characters. There is, for instance, a metacharacter—the dot (.)—that can be used as a “wildcard” to match any single character. You can think of this wildcard as analogous to a blank tile in Scrabble where it means any letter. Thus, we can specify the regular expression “A.E” and it will match “ACE,” “ABE”, and “ALE”. It will match any character in the position following “A”.

The metacharacter *,

the asterisk, is used to match zero or more occurrences of the

preceding regular expression, which typically is a

single character. You may be familiar with * as a shell

metacharacter, where it means “zero or more characters.” But that

meaning is very different from * in a

regular expression. By itself, the asterisk metacharacter does not match

anything; it modifies what goes before it. The regular expression

.* matches any number of characters,

whereas in the shell, * has that

meaning. (For instance, in the shell, ls * will list all the files in the

current directory.) The regular expression “A.*E” matches any string that matches “A.E” but

it will also match any number of characters between “A” and “E”:

“AIRPLANE,” “A FINE,” “AFFABLE,” or “A LONG WAY HOME,” for example. Note

that “any number of characters” can even be zero!

If you understand the difference between “.” and “*” in regular expressions, you already know about the two basic types of metacharacters: those that can be evaluated to a single character, and those that modify how preceding characters are evaluated.

It should also be apparent that by use of metacharacters you can expand or limit the possible matches. You have more control over what’s matched and what’s not.

[1] Some other programs that use regular expressions offer the option of having them be case-insensitive, but sed and awk do not.