Chapter 7. Authentication and Authorization

Many web applications suffer from broken authentication and authorization mechanisms. This chapter discusses vulnerabilities related to these mechanisms and teaches practices that can help you avoid the most common mistakes. These practices are further illustrated with example code, but be careful not to copy an example blindly out of context—it is more important to understand the principles and practices being taught. Only then can you apply them correctly.

Authentication is the process by which a user’s identity is proven. This typically involves a simple username and password check. Thus, a user who is logged in is an authenticated user.

Authorization, often called access control, is how you guard access to protected resources and determine whether a user is authorized to access a particular resource. For example, many web applications have resources that are available only to authenticated users, resources that are available only to administrators, and resources that are available to everyone.

A predominant cause of access control vulnerabilities is carelessness—less care and attention are given to the sections of a web application that are used the least. Administrative features and access control are often an afterthought, and they are written with an authorized user in mind, without considering what an attacker might try to do. An authorized user is trusted more than an anonymous user, but if your administrative features are available via a public URL, they are an inviting target to an attacker. In these cases, negligence is your primary foe.

As with security, access control needs to be integrated into your design. It is not something to be bolted onto an existing application. Although possible, this approach is very error-prone, and errors in your access control are necessarily security vulnerabilities.

Tip

Access control also requires a reliable identification mechanism. After all, if an attacker can impersonate a legitimate user, any access control based on the user’s identity is useless. Therefore, you want to also be mindful of attacks, such as session hijacking. See Chapter 4 for more information about sessions and related attacks.

This chapter covers four common concerns related to authentication and authorization: brute force attacks , password sniffing, replay attacks, and persistent logins.

Brute Force Attacks

A brute force attack is an attack in which all available options are exhausted with no intelligence regarding which options are more likely. This is more formally known as an enumeration attack—the attack enumerates through all possibilities.

In terms of access control, brute force attacks typically involve an attacker trying to log in with a very large number of attempts. In most cases, known valid usernames are used, and the password is the only thing being guessed.

Tip

Although not technically a brute force attack, dictionary attacks are very similar. The biggest difference is that more intelligence is used to make each guess. A dictionary attack enumerates through a list of likely possibilities, rather than enumerating through a list of all possibilities.

Throttling authentication attempts or otherwise limiting the number of failures allowed is a fairly effective safeguard, but the dilemma is to be able to identify and stymie an attacker without adversely affecting your legitimate users.

In these situations, recognizing consistency can help you to distinguish between a particular attacker and everyone else. The idea is very similar to the Defense in Depth approach described in Chapter 4 to help protect against session hijacking, but you’re trying to identify an attacker instead of a legitimate user.

Consider the following HTML form:

<form action="http://example.org/login.php" method="POST">

<p>Username: <input type="text" name="username" /></p>

<p>Password: <input type="password" name="password" /></p>

<p><input type="submit" /></p>

</form>An attacker can observe this form and create a script that tries to authenticate by sending the expected POST request to http://example.org/login.php:

<?php

$username = 'victim';

$password = 'guess';

$content = "username=$username&password=$password";

$content_length = strlen($content);

$http_request = '';

$http_response = '';

$http_request .= "POST /login.php HTTP/1.1\r\n";

$http_request .= "Host: example.org\r\n";

$http_request .= "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded\r\n";

$http_request .= "Content-Length: $content_length\r\n";

$http_request .= "Connection: close\r\n";

$http_request .= "\r\n";

$http_request .= $content;

if ($handle = fsockopen('example.org', 80))

{

fputs($handle, $http_request);

while (!feof($handle))

{

$http_response .= fgets($handle, 1024);

}

fclose($handle);

/* Check Response */

}

else

{

/* Error */

}

?>With such a script, an attacker can add a simple loop to continue trying different passwords, and $http_response can be checked after each attempt. When a change in $http_response is observed, the authentication credentials are expected to be valid.

You can implement a number of safeguards to help protect against these types of attacks. It is worth noting that the HTTP requests used in a brute force attack are often identical in every way with one exception—the password.

Although a useful defense is to temporarily suspend an account once a maximum number of login failures are recorded, you might consider suspending an account according to certain aspects of the request, so that an attacker is less likely to interfere with a legitimate user’s use of your application.

A few other approaches can also be used to make brute force attacks more difficult and less likely to succeed. A simple throttling mechanism can help to eliminate the practicality of such an attack:

<?php

/* mysql_connect() */

/* mysql_select_db() */

$clean = array();

$mysql = array();

$now = time();

$max = $now - 15;

$salt = 'SHIFLETT';

if (ctype_alnum($_POST['username']))

{

$clean['username'] = $_POST['username'];

}

else

{

/* ... */

}

$clean['password'] = md5($salt . md5($_POST['password'] . $salt));

$mysql['username'] = mysql_real_escape_string($clean['username']);

$sql = "SELECT last_failure, password

FROM users

WHERE username = '{$mysql['username']}'";

if ($result = mysql_query($sql))

{

if (mysql_num_rows($result))

{

$record = mysql_fetch_assoc($result);

if ($record['last_failure']> $max)

{

/* Less than 15 seconds since last failure */

}

elseif ($record['password'] == $clean['password'])

{

/* Successful Login */

}

else

{

/* Failed Login */

$sql = "UPDATE users

SET last_failure = '$now'

WHERE username = '{$mysql['username']}'";

mysql_query($sql);

}

}

else

{

/* Invalid Username */

}

}

else

{

/* Error */

}

?>This throttles the rate with which a user is allowed to try again after a login failure. If a new attempt is made within 15 seconds of a previous failure, authentication fails regardless of whether the login credentials are correct. This is a key point in the implementation. It is not enough to simply deny access when a new attempt is made within 15 seconds of the previous failure—the output in such cases must be consistent regardless of whether the login would otherwise be successful; otherwise, an attacker can simply check for inconsistent output in order to determine whether the login credentials are correct.

Password Sniffing

Although not specific to access control, when an attacker can sniff (observe) traffic between your users and your application, being mindful of data exposure becomes increasingly important, particularly regarding authentication credentials.

Using SSL is an effective way to protect the contents of both HTTP requests and their corresponding responses from exposure. Any request for a resource that uses the https scheme is protected against password sniffing

. It is a best practice to always use SSL for sending authentication credentials, and you might consider also using SSL for all requests that contain a session identifier because this helps protect your users against session hijacking.

To protect a user’s authentication credentials from exposure, use an https scheme for the URL in the form’s action attribute as follows:

<form action="https://example.org/login.php" method="POST">

<p>Username: <input type="text" name="username" /></p>

<p>Password: <input type="password" name="password" /></p>

<p><input type="submit" /></p>

</form>Tip

Using the POST request method is highly recommended for authentication forms because the authentication credentials are less exposed than when using GET, regardless of whether SSL is being used.

Although this is all that is required to protect a user’s authentication credentials from exposure, you should also protect the HTML form itself with SSL. There is no technical reason to do so, but users feel more comfortable providing authentication credentials when they see that the form is protected with SSL (see Figure 7-1).

Replay Attacks

A replay attack, sometimes called a presentation attack, is any attack that involves the attacker replaying data sent previously by a legitimate user in order to gain access or other privileges granted to that user.

As with password sniffing, protecting against replay attacks requires you to be mindful of data exposure. In order to prevent replay attacks, you want to make it very difficult for an attacker to capture any data that can be used to gain access to a protected resource. This primarily requires that you focus on avoiding the following:

The use of any data that provides permanent access to a protected resource

The exposure of any data that provides access to a protected resource (even when the data provides only temporary access)

Thus, you should use only data that provides temporary access to protected resources, and you should avoid exposing this data as much as possible. These are generic guidelines, but they can offer guidance as you implement your mechanisms.

The first guideline is one that I see violated with frightening frequency. Many developers focus on protecting sensitive data from exposure but ignore the risks of using data that provides permanent access.

For example, consider the use of client-side scripting to hash the password provided in an authentication form. Instead of the cleartext password being exposed, only its hash is. This protects the user’s original password. The problem with this approach is that it is still vulnerable to a replay attack—an attacker can simply replay a valid authentication attempt in order to be authenticated, and this works as long as the user’s password is consistent.

Tip

For more secure implementations and JavaScript source for MD5 and other algorithms, see http://pajhome.org.uk/crypt/md5/.

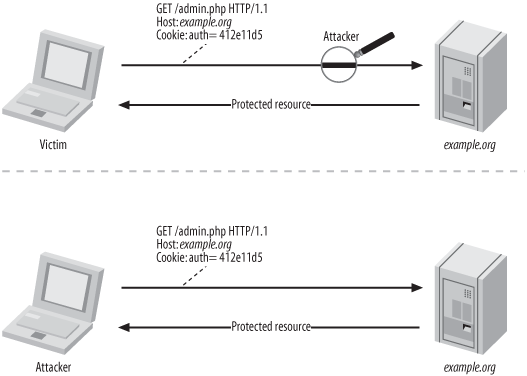

A similar violation of the first guideline is assigning a cookie that provides permanent access to a resource. For example, consider an attempt to implement a persistent login mechanism that issues cookies as follows:

<?php

$auth = $username . md5($password);

setcookie('auth', $cookie);

?>If an unauthenticated user presents an auth cookie, it can be inspected to determine whether the hash of the password in the cookie matches the hash of the password stored in the database for that user. If it does, the user is authenticated.

The problem with this approach is that the exposure of this cookie is an extreme risk. If captured, it provides an attacker with permanent access. Although the legitimate user’s cookie may expire, an attacker can always present the cookie required for authentication, and until the legitimate user’s password changes, authentication is successful. See Figure 7-2 for a complete illustration of this scenario.

A better persistent login implementation uses data that only temporarily grants access, and this is the topic of the next section.

Persistent Logins

A persistent login is a mechanism that persists authentication between browser sessions. In other words, a user who logs in today is still logged in tomorrow, even if the user’s session expires between visits.

A persistent login diminishes the security of your authentication mechanism, but it increases usability. Instead of troubling the user to provide authentication credentials upon each visit, you can provide the user with the option of being remembered.

Tip

The most common flawed implementation of a persistent login that I have observed is to store the username and password in a cookie. The temptation is understandable—rather than prompting the user for a username and password, you can simply read them from a cookie. Everything else about the authentication process is consistent, so this makes the implementation easy.

If you store the username and password in a cookie, immediately disable this feature and read the rest of this section for some ideas for a more secure implementation. You should also require users who present such cookies in the future to change their passwords because they have been exposed.

A persistent login requires a persistent login cookie, often called an authentication cookie , because a cookie is the only standard mechanism that can be used to persist data across multiple sessions. If this cookie provides permanent access, it poses a serious risk to the security of your application, so you want to be sure that the information you store in the cookie has a restricted window of time for which it can be used to authenticate.

The first step is to devise a method that mitigates the risk posed by a captured persistent login cookie. Although capture is clearly something that you want to avoid, a Defense in Depth approach is best, particularly because this mechanism diminishes the security of an authentication form even when implemented correctly. Thus, the cookie should not be based upon any information that provides permanent access, such as the user’s password.

To avoid the use of the user’s password, create a token that is valid for a single authentication:

<?php

$token = md5(uniqid(rand(), TRUE));

?>You can store this token in a user’s session in order to associate it with that particular user, but this doesn’t help you persist logins across sessions, which is the whole point. Therefore, you must use a different method to associate a token with a particular user.

Because a username is less sensitive than a password, you can store it in the cookie, and this can be used during authentication to determine which user’s token is being presented. However, a slightly better approach is to use a secondary identifier that is less likely to be predicted or discovered. Consider a table for storing usernames and passwords that has three additional columns for a secondary identifier (identifier), a persistent login token (token), and a persistent login timeout (timeout):

mysql> DESCRIBE users;

+------------+------------------+------+-----+---------+-------+

| Field | Type | Null | Key | Default | Extra |

+------------+------------------+------+-----+---------+-------+

| username | varchar(25) | | PRI | | |

| password | varchar(32) | YES | | NULL | |

| identifier | varchar(32) | YES | MUL | NULL | |

| token | varchar(32) | YES | | NULL | |

| timeout | int(10) unsigned | YES | | NULL | |

+------------+------------------+------+-----+---------+-------+By generating and storing a secondary identifier along with the token, you can create a cookie that does not disclose any of the user’s authentication credentials:

<?php

$salt = 'SHIFLETT';

$identifier = md5($salt . md5($username . $salt));

$token = md5(uniqid(rand(), TRUE));

$timeout = time() + 60 * 60 * 24 * 7;

setcookie('auth', "$identifier:$token", $timeout);

?>When a user presents a persistent login cookie, you can check to see that several criteria are met:

<?php

/* mysql_connect() */

/* mysql_select_db() */

$clean = array();

$mysql = array();

$now = time();

$salt = 'SHIFLETT';

list($identifier, $token) = explode(':', $_COOKIE['auth']);

if (ctype_alnum($identifier) && ctype_alnum($token))

{

$clean['identifier'] = $identifier;

$clean['token'] = $token;

}

else

{

/* ... */

}

$mysql['identifier'] = mysql_real_escape_string($clean['identifier']);

$sql = "SELECT username, token, timeout

FROM users

WHERE identifier = '{$mysql['identifier']}'";

if ($result = mysql_query($sql))

{

if (mysql_num_rows($result))

{

$record = mysql_fetch_assoc($result);

if ($clean['token'] != $record['token'])

{

/* Failed Login (wrong token) */

}

elseif ($now > $record['timeout'])

{

/* Failed Login (timeout) */

}

elseif ($clean['identifier'] !=

md5($salt . md5($record['username'] . $salt)))

{

/* Failed Login (invalid identifier) */

}

else

{

/* Successful Login */

}

}

else

{

/* Failed Login (invalid identifier) */

}

}

else

{

/* Error */

}

?>You should adhere to three important implementation details to restrict the use of a persistent login cookie:

The cookie itself expires in one week (or less).

The cookie is good for only a single authentication (delete or regenerate the token after a successful login).

A timeout of one week (or less) is enforced on the server.

Tip

If you want a user to be remembered indefinitely as long as the user visits your application more frequently than the timeout, simply regenerate the token after each authentication and set a new cookie.

Another useful guideline is to require that the user provide a password prior to performing a sensitive transaction. The persistent login should grant access to only the features of your application that are not considered to be extremely sensitive. There is simply no substitute for requiring a user to manually authenticate prior to performing some sensitive transaction.

Lastly, you want to make sure that a user who logs out is really logged out, and this includes deleting the persistent login cookie:

<?php

setcookie('auth', 'DELETED!', time());

?>This overwrites the cookie with a useless value and also sets it to expire immediately. Thus, a user whose clock somehow causes this cookie to persist should still be effectively logged out.