Chapter 3. Databases and SQL

PHP’s role is often that of a conduit between various data sources and the user. In fact, some people describe PHP more as a platform than just a programming language. To this end, PHP is frequently used to interact with a database.

PHP is well suited for this role, particularly due to the extensive list of databases with which it can communicate. The following list is a small sample of the databases that PHP supports:

| DB2 |

| ODBC |

| SQLite |

| InterBase |

| Oracle |

| Sybase |

| MySQL |

| PostgreSQL |

| DBM |

As with any remote data store, databases carry their own risks. Although database security is not a topic that this book covers, the security of the database is something to keep in mind, particularly concerning whether to consider data obtained from the database as input .

As discussed in Chapter 1, all input must be filtered, and all output must be escaped. When dealing with a database, this means that all data coming from the database must be filtered, and all data going to the database must be escaped.

Tip

A common mistake is to forget that a SELECT query is data that is being sent to the database. Although the purpose of the query is to retrieve data, the query itself is output.

Many PHP developers fail to filter data coming from the database because only filtered data is stored therein. While the security risk inherent in this approach is slight, it is still not a best practice and not an approach that I recommend. This approach places trust in the security of the database, and it also violates the principle of Defense in Depth. Remember, redundant safeguards have value, and this is a perfect example. If malicious data is somehow injected into the database, your filtering logic can catch it, but only if such logic exists.

This chapter covers a few other topics of concern, including exposed access credentials and SQL injection. SQL injection is of particular concern due to the frequency with which such vulnerabilities are discovered in popular PHP applications.

Exposed Access Credentials

One of the primary concerns related to the use of a database is the disclosure of the database access credentials—the username and password. For convenience, these might be stored in a file named db.inc:

<?php $db_user = 'myuser'; $db_pass = 'mypass'; $db_host = '127.0.0.1'; $db = mysql_connect($db_host, $db_user, $db_pass); ?>

Both myuser and mypass are sensitive, so they warrant particular attention. Their presence in your source code poses a risk, but it is an unavoidable one. Without them, your database cannot be protected with a username and password.

If you look at a default httpd.conf (Apache’s configuration file), you can see that the default type is text/plain. This poses a particular risk when a file such as db.inc is stored within document root. Every resource within document root has a corresponding URL, and because Apache does not typically have a particular content type associated with .inc files, a request for such a resource will return the source in plain text (the default type), including the database access credentials.

To further explain this risk, consider a server with a document root of /www. If db.inc is stored in /www/inc, it has its own URL—http://example.org/inc/db.inc (assuming that example.org is the host). Visiting this URL displays the source of db.inc in plain text. Thus, your access credentials risk exposure if db.inc is stored in any subdirectory of /www, document root.

The best solution to this particular problem is to store your includes outside of document root. You do not need to have them in any particular place in the filesystem to be able to include or require them—all you need to do is ensure that the web server has read privileges. Therefore, it is an unnecessary risk to place them within document root, and any method that attempts to minimize this risk without relocating all includes outside of document root is subpar. In fact, you should place only resources that absolutely must be accessible via URL within document root. It is, after all, a public directory.

Tip

This topic also applies to SQLite databases. It is very convenient to use a database that is stored within the current directory because you can reference it by name and do not have to specify the path. However, this places your database within document root and represents an unnecessary risk. Your database can be compromised with a simple HTTP request if you do not take additional steps to prevent direct access. Keeping your SQLite databases outside of document root is highly recommended.

If outside factors prevent you from achieving the optimal solution of placing all includes outside of document root, you can configure Apache to reject requests for .inc resources:

<Files ~ "\.inc$">

Order allow,deny

Deny from all

</Files>Tip

See Chapter 8 for a method of protecting your database access credentials that is particularly effective in shared hosting environments (in which files outside of document root are still at risk of exposure).

SQL Injection

SQL injection is one of the most common vulnerabilities in PHP applications. What is particularly surprising about this fact is that an SQL injection vulnerability requires two failures on the part of the developer—a failure to filter data as it enters the application (filter input), and a failure to escape data as it is sent to the database (escape output). Neither of these crucial steps should ever be omitted, and both steps deserve particular attention in an attempt to minimize errors.

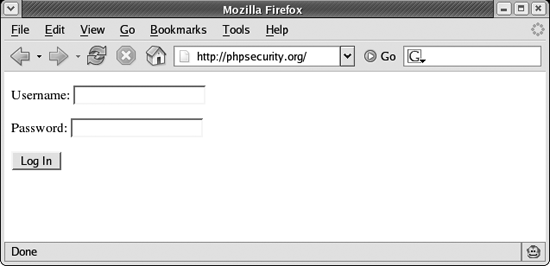

SQL injection typically requires some speculation and experimentation on the part of the attacker—it is necessary to make an educated guess about your database schema (assuming, of course, that the attacker does not have access to your source code or database schema). Consider a simple login form:

<form action="/login.php" method="POST"> <p>Username: <input type="text" name="username" /></p> <p>Password: <input type="password" name="password" /></p> <p><input type="submit" value="Log In" /></p> </form>

Figure 3-1 shows how this form looks when rendered in a browser.

An attacker presented with this form begins to speculate about the type of query that you might be using to validate the username and password provided. By viewing the HTML source, the attacker can begin to make guesses about your habits regarding

naming conventions. A common assumption is that the names used in the form match columns in the database table. Of course, making sure that these differ is not a reliable safeguard.

A good first guess, as well as the actual query that I will use in the following discussion, is as follows:

<?php

$password_hash = md5($_POST['password']);

$sql = "SELECT count(*)

FROM users

WHERE username = '{$_POST['username']}'

AND password = '$password_hash'";

?>Tip

Using the MD5 of a user’s password is a common approach that is no longer considered particularly safe. Recent discoveries have revealed both weaknesses in the MD5 algorithm , and many MD5 databases minimize the effort required to reverse an MD5. To see an example, visit http://md5.rednoize.com/.

The best protection is to salt the user’s password using a string that is unique to your application. For example:

<?php $salt = 'SHIFLETT'; $password_hash = md5($salt . md5($_POST['password'] . $salt)); ?>

Of course, it’s not necessary that the attacker guess the schema correctly on the first try. Some experimentation is almost always necessary. An example of a good experiment is to provide a single quote as the username, because this can expose some important information. Many developers use functions such as mysql_error() whenever an error is encountered during the execution of the query. The following illustrates this approach:

<?php mysql_query($sql) or exit(mysql_error()); ?>

While this approach is very helpful during development, it can expose vital information to an attacker. If the attacker provides a single quote as the username and mypass as the password, the query becomes:

<?php

$sql = "SELECT *

FROM users

WHERE username = '''

AND password = 'a029d0df84eb5549c641e04a9ef389e5'";

?>If this query is sent to MySQL as illustrated in the previous example, the following error is displayed:

You have an error in your SQL syntax. Check the manual that corresponds to your MySQL server version for the right syntax to use near 'WHERE username = ''' AND password = 'a029d0df84eb55

With very little work, the attacker already knows the names of two columns (username and password) and the order in which they appear in the query. In addition, the attacker knows that data is not being properly filtered (there was no application error mentioning an invalid username) nor escaped (there was a database error), and the entire WHERE clause has been exposed. Knowing the format of the WHERE clause, the attacker can now try to manipulate which records are matched by the query.

From this point, the attacker has many options. One is to try to make the query match regardless of whether the access credentials are correct by providing the following username:

myuser' or 'foo' = 'foo' --

Assuming mypass is used as the password, the query becomes:

<?php

$sql = "SELECT *

FROM users

WHERE username = 'myuser' or 'foo' = 'foo' --

AND password = 'a029d0df84eb5549c641e04a9ef389e5'";

?>Because — begins an SQL comment, the query is effectively terminated at that point. This allows an attacker to log in successfully without knowing either a valid username or password.

If a valid username is known, an attacker can target a particular account, such as chris:

chris' --

As long as chris is a valid username, the attacker is allowed to take control of the account because the query becomes the following:

<?php

$sql = "SELECT *

FROM users

WHERE username = 'chris' --

AND password = 'a029d0df84eb5549c641e04a9ef389e5'";

?>Luckily, SQL injection is easily avoided. As mentioned in Chapter 1, you should always filter input and escape output.

While neither step should be omitted, performing either of these steps eliminates most of the risk of SQL injection. If you filter input and fail to escape output, you’re likely to encounter database errors (the valid data can interfere with the proper form of your SQL query), but it’s unlikely that valid data is going to be capable of modifying the intended behavior of a query. On the other hand, if you escape output but fail to filter input, the escaping will ensure that the data does not interfere with the format of the SQL query and can protect you against many common SQL injection attacks.

Of course, both steps should always be taken. Filtering input depends entirely on the type of data being filtered (some examples are provided in Chapter 1), but escaping output

in the case of data being sent to a database generally requires only a single function. For MySQL users, this function is mysql_real_escape_string():

<?php

$clean = array();

$mysql = array();

$clean['last_name'] = "O'Reilly";

$mysql['last_name'] = mysql_real_escape_string($clean['last_name']);

$sql = "INSERT

INTO user (last_name)

VALUES ('{$mysql['last_name']}')";

?>Use an escaping function native to your database if one exists. Otherwise, using addslashes() is a good last resort.

With all data used to create an SQL query properly filtered and escaped, there is no practical risk of SQL injection.

Tip

If you use a database library that offers support for bound parameters or placeholders (PEAR::DB, PDO, etc.), you can enjoy an extra layer of protection. For example, consider the following query using PEAR::DB:

<?php

$sql = 'INSERT

INTO user (last_name)

VALUES (?)';

$dbh->query($sql, array($clean['last_name']));

?>Because the data cannot directly manipulate the format of the query, the risk of SQL injection is mitigated. PEAR::DB automatically escapes and quotes the data according to the requirements of your database, so your responsiblity is reduced to filtering input.

If you use bound parameters, your data never enters a context where it is considered anything other than data. This removes the necessity of escaping, although you can consider the escaping to be a step that essentially does nothing (if you prefer to stick to the habit of always escaping output) because there are no characters that need to be represented in a special way. Bound parameters offer the strongest protection against SQL injection.

Exposed Data

Another concern regarding databases is the exposure of sensitive data. Whether you’re storing credit card numbers, social security numbers, or something else, you want to make sure that the data in your database is safe.

While protecting the security of the database itself is outside the scope of this book (and most likely outside a PHP developer’s responsibility), you can encrypt the data that is most sensitive, so that a compromise of the database is less disastrous as long as the key is kept safe. See Appendix C for more information about cryptography.