In order to look for SQL injection vulnerabilities, we can use the following as an initial testing string:

'1 or 1==1--

The main purpose is generating a Boolean value, TRUE, which could be evaluated in a SQL statement, but there are other similar strings that could work, for example:

'1 or 1=1

'a' = 'a

'1=1

The preceding three strings have the same effect and can be used when one of them does not work.

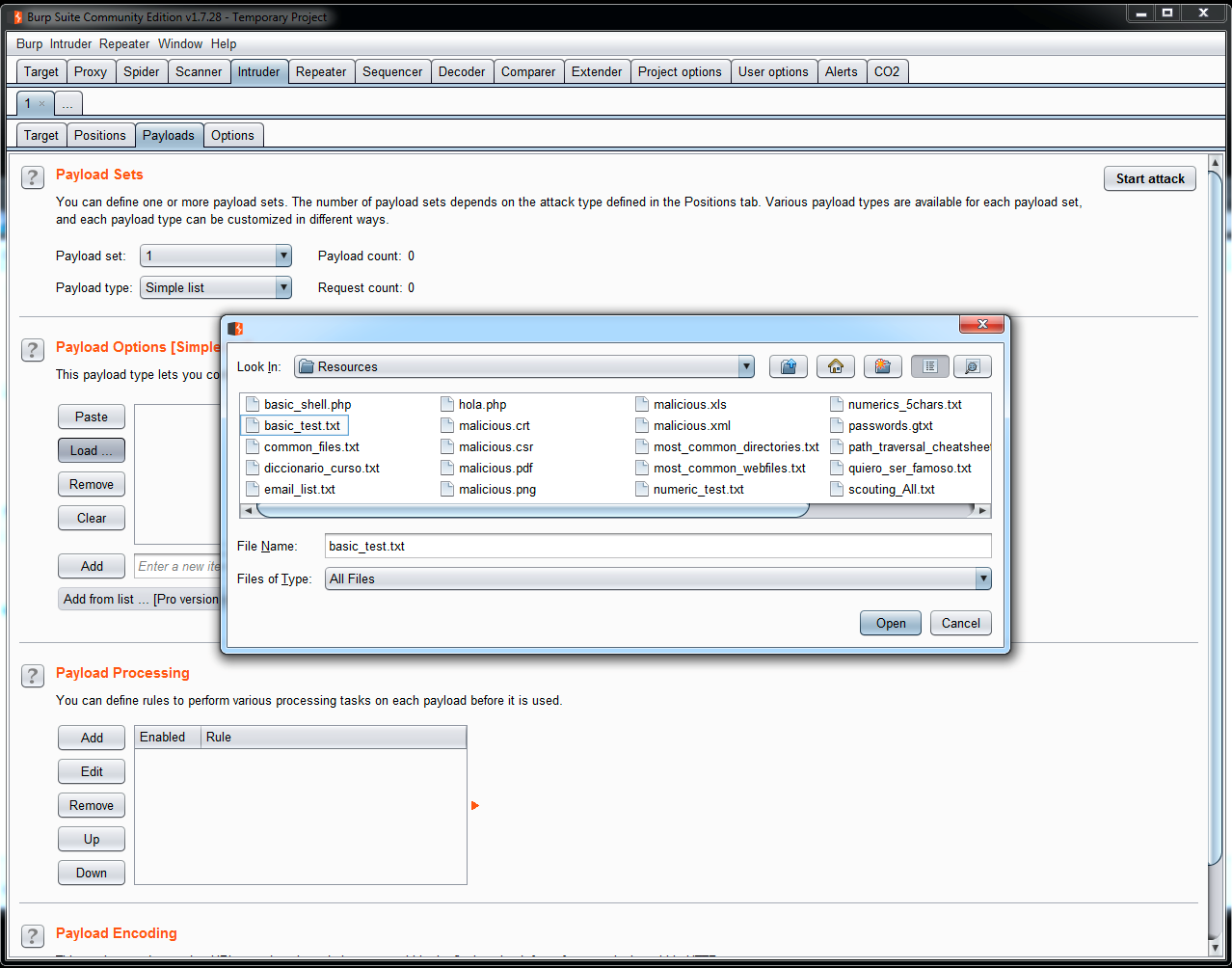

For the basic identification of SQL injection vulnerabilities, it is highly recommended to use the Intruder tool included in Burp Suite. You can load all these testing strings in a file and launch to a bug quantity of fields:

- To add these testing strings, create a TXT file and add all of them. Then, open Burp Suite, go to Intruder | Payloads | Payload Options | Load, and select the file that you have created. Now, you can use all the strings to test all the fields in an application:

- Now, let's see another example used in applications. The SELECT statement is used to get information from a database, but there are other statements. Another very commonly used statement is INSERT, which is used to add information to a database. So, imagine that the application used to manage the students in a university has a query for adding new information, as follows:

INSERT INTO students (student_name, average, group, subject) VALUES ('Diana', '9', '1CV01', 'Math');

- This statement means—insert the values Diana, 9, 1CV01, and Math in this order in the values student_name, average, group, and subject. So, if we want to execute this statement from an application, we are going to use parameters or variables to pass the values to the application's backend, for example:

"INSERT INTO students (student_name, average, group, subject) VALUES (\'".$name."\', \'".$number."\', \'".$group.", \'".$subject."\');"

- Let's see the use of \ to escape the single quotes. Most programming languages solve the use of special characters in this way. What happened if we entered special characters in the following statement?

"INSERT INTO students (student_name, average, group, subject) VALUES (\'".Diana')-

At this moment, the application will crash because a rule for INSERT statements is that the number of values that you want to insert needs to be the same number that is weighted by the application. However, as you can see, the same problem is detected in the SELECT statement. If queries are not validated in the way inputs are provided, then it is possible to modify the information to cut the complete statement and have control over the information to be inserted.

You should not always enter new registers in a database; sometimes you just need to update information in a register that currently exists. To do that, SQL uses the UPDATE statement. As an example, look at the next line:

UPDATE students SET password='miscalificacionesnadielasve' WHERE student_name = 'Diana' and password = 'yareprobetodo'

In this statement, the scholar system is changing the password for the student Diana, and at the same time it is validating whether she is a student present in the database, because the password needs to be stored in the same database to perform the change. As in the other statements, let's insert special characters into this:

"UPDATE students SET password=\'".$new_passsowrd."\' WHERE student_name = \'".student_name."\' and password = \'".$past_password."

The preceding line is the SQL statement as the application sees it, with the parameters that need to be filled with information. Now, insert the testing string:

"UPDATE students SET password=\'".$new_passsowrd."\' WHERE student_name = \'".Diana' 1 or 1==1--"

This line is so interesting; as I said before, the SQL statement was thought to validate the current password, before changing it to a new one. Now, what happened when the string Diana' 1 or 1==1-- is inserted? Well, all this part is evaluated as a TRUE value. So, at this moment it is not important whether the user has the current password or not; the update will be done without the validation of the current password.

Also, it is possible to add and erase information; to do that, SQL uses the DELETE statement. Let's check the statement in the following example:

DELETE FROM students WHERE student_name = 'Diana'

Translated as the statement used by the application, it looks as follows:

"DELETE FROM students WHERE student_name = \'".$name."\'"

So, as in the other statements, let's check what happened:

DELETE FROM students WHERE student_name = 'or 1==1--

Due to the statement being evaluated as TRUE, all the registers are deleted.