For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact

Special Sales Department Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 Email: orders@manning.com

©2017 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed

on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources

of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental

chlorine.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed

on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources

of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental

chlorine.

|

Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 |

Development editors: Cynthia Kane, Dan Seiter, Marina Michaels Technical development editor: Andrew West Review editor: Donna Clements Project editor: Karen Gulliver Copyeditor: Andy Carroll Proofreader: Katie Tennant Technical proofreader: Michiel Trimpe Typesetter: Dottie Marsico Cover designer: Marija Tudor

ISBN 9781617293436

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 – EBM – 22 21 20 19 18 17

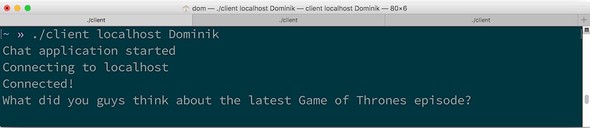

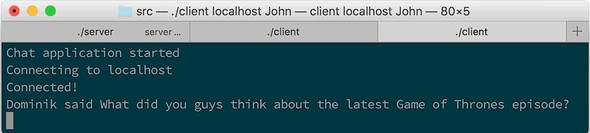

Chapter 3. Writing a chat application

1.2. Nim’s benefits and shortcomings

Chapter 3. Writing a chat application

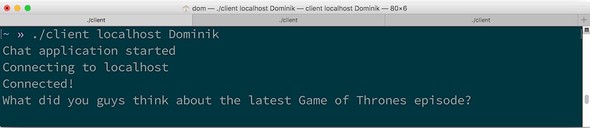

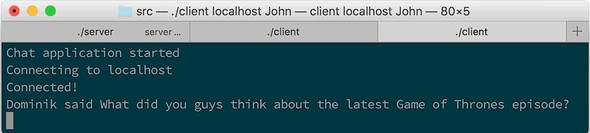

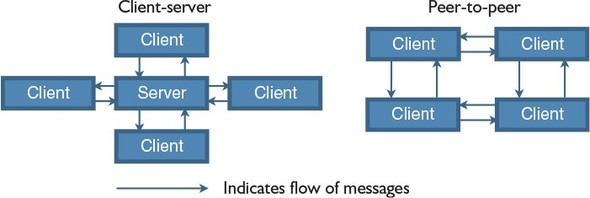

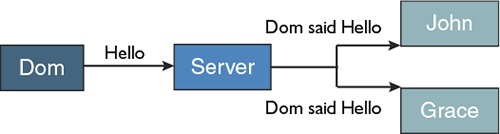

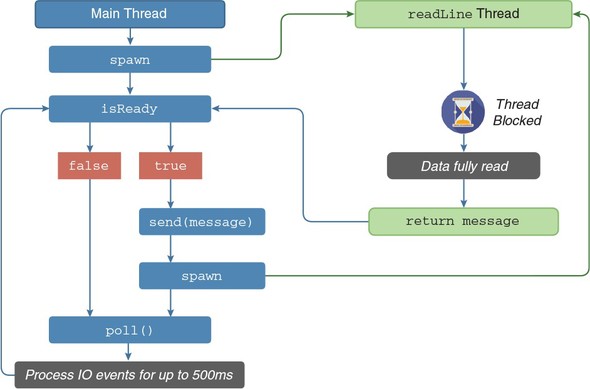

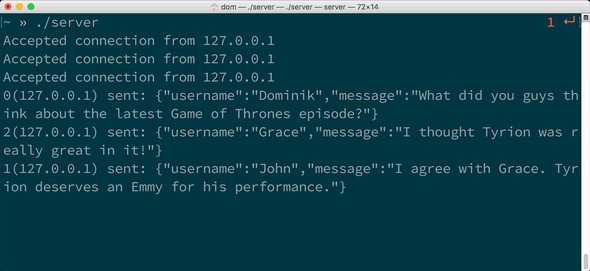

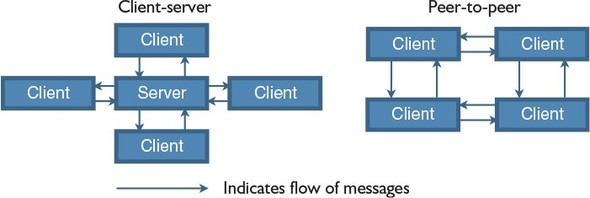

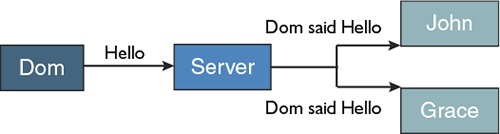

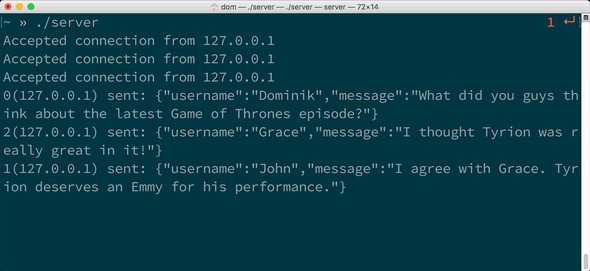

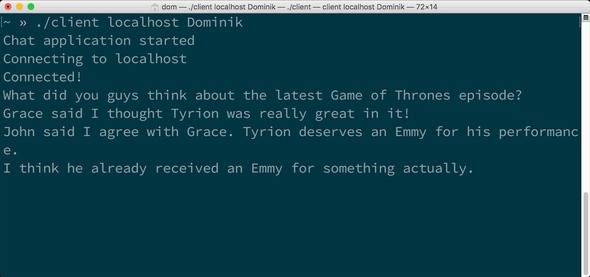

3.1. The architecture of a chat application

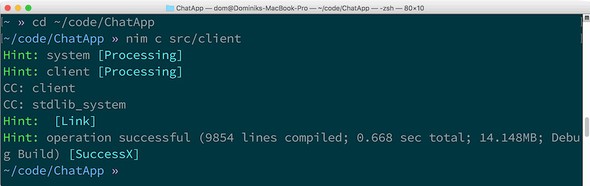

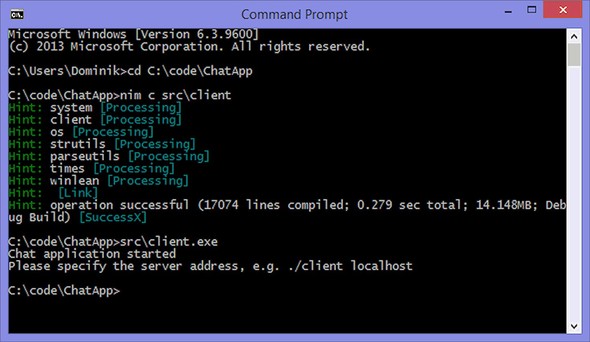

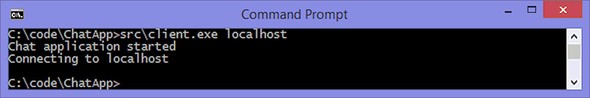

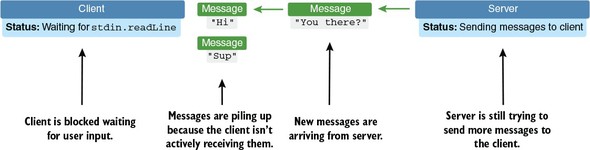

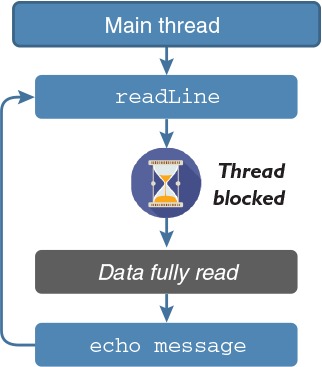

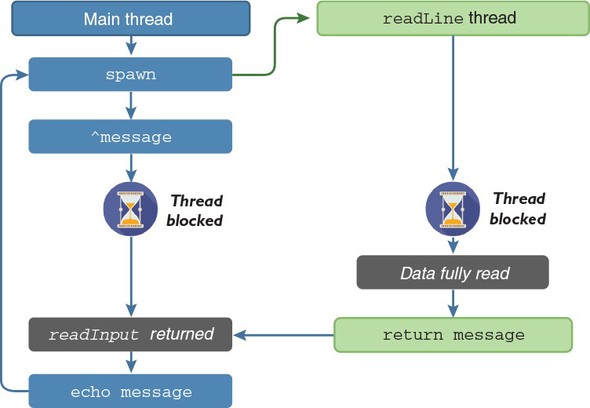

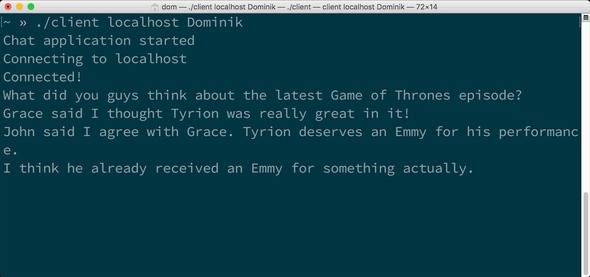

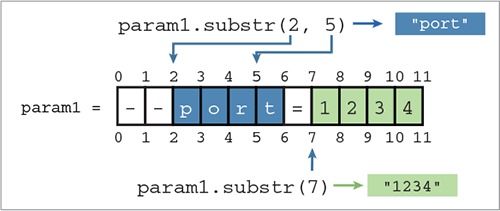

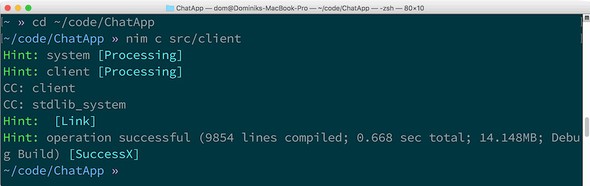

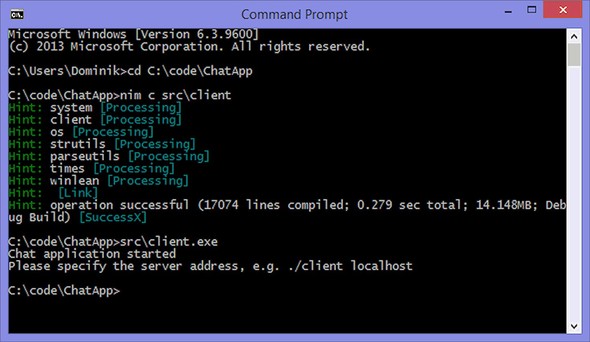

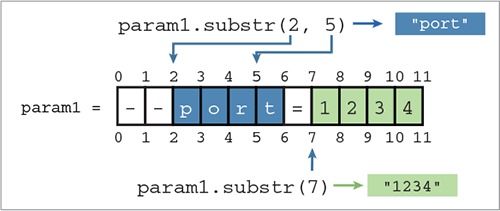

3.3. Retrieving input in the client component

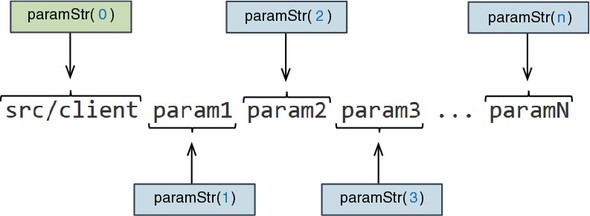

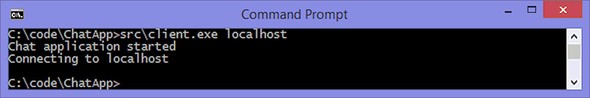

3.3.1. Retrieving command-line parameters supplied by the user

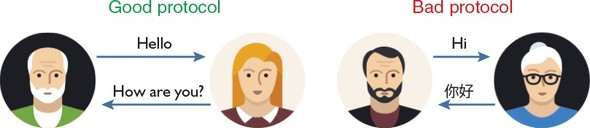

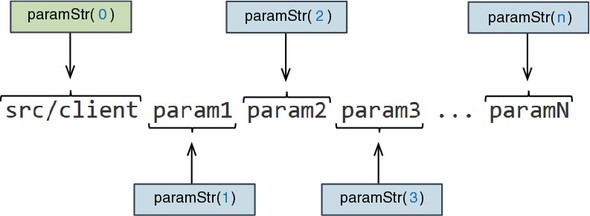

3.4. Implementing the protocol

3.5. Transferring data using sockets

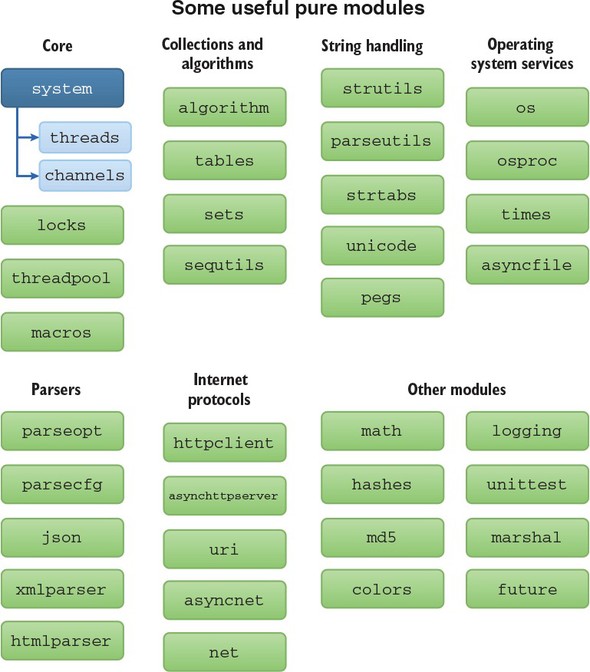

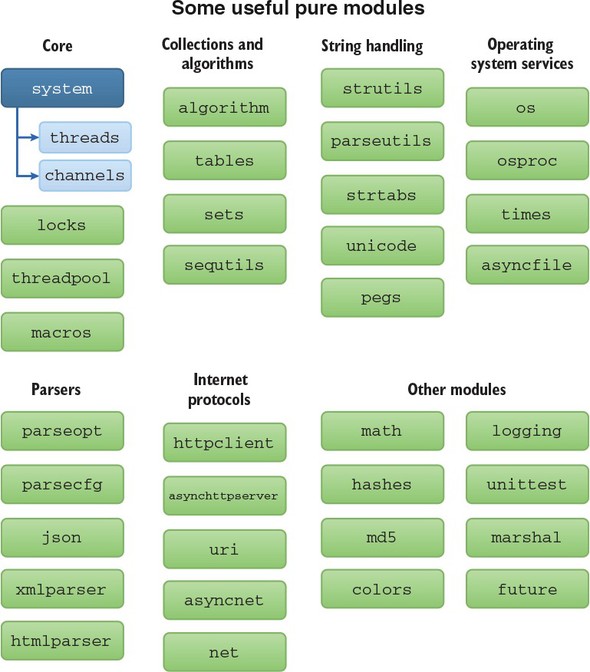

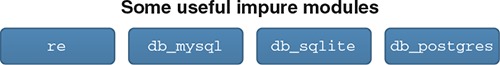

Chapter 4. A tour through the standard library

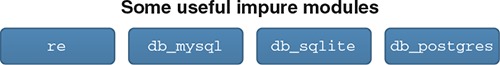

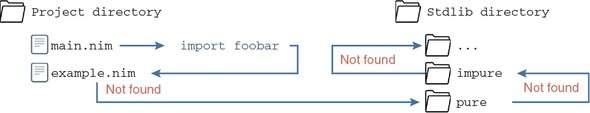

4.2. Overview of the standard library

4.4. Data structures and algorithms

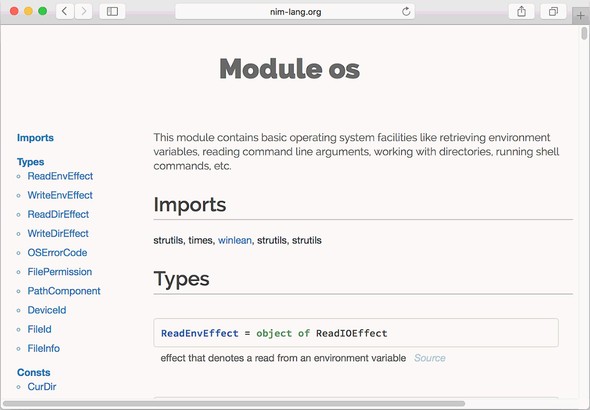

4.5. Interfacing with the operating system

4.5.1. Working with the filesystem

4.6. Understanding and manipulating data

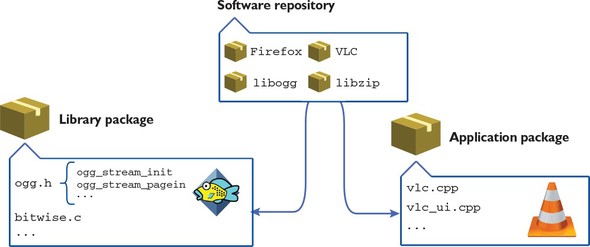

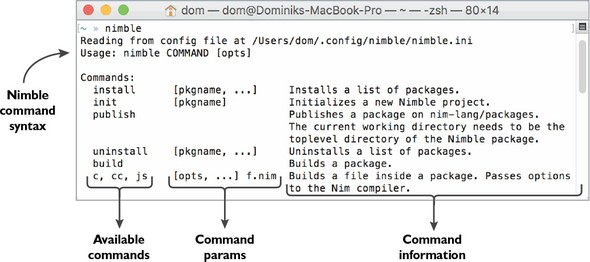

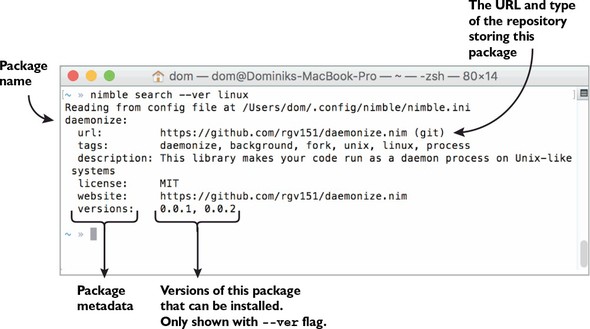

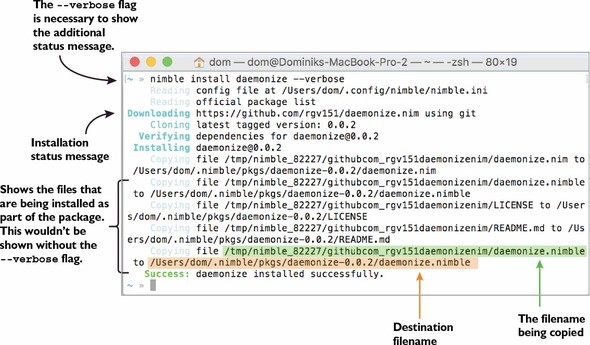

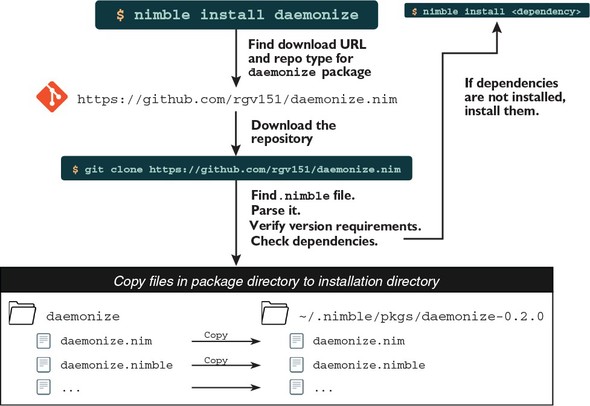

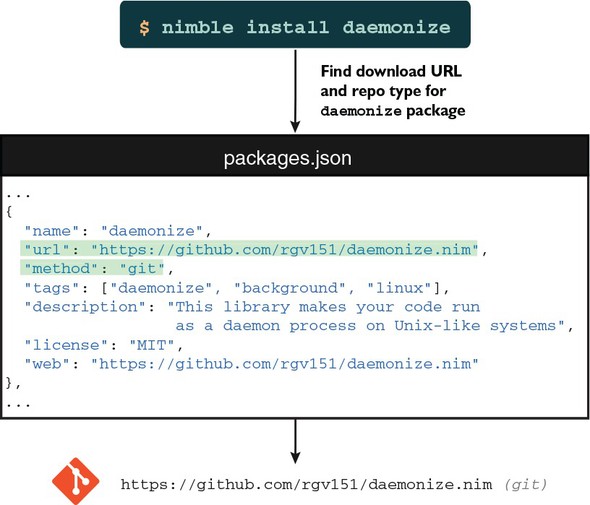

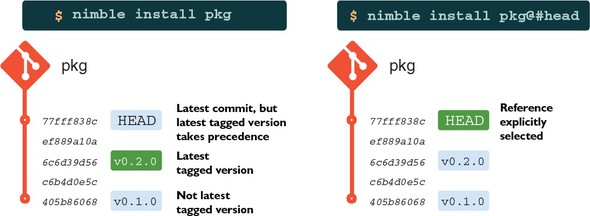

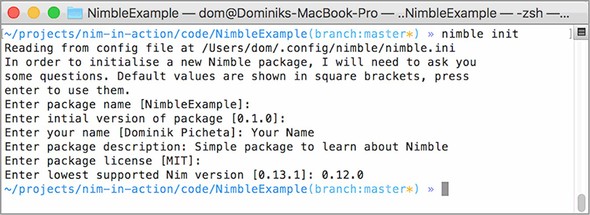

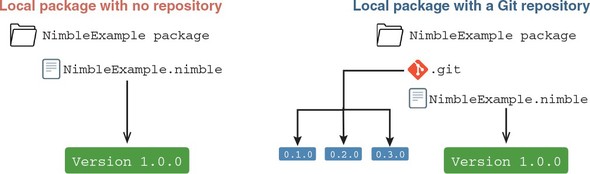

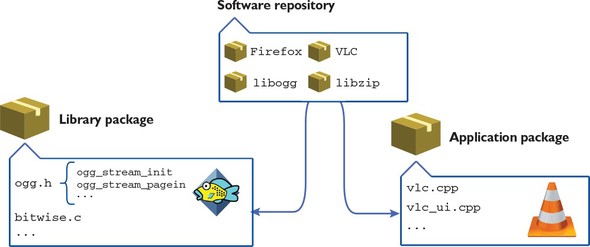

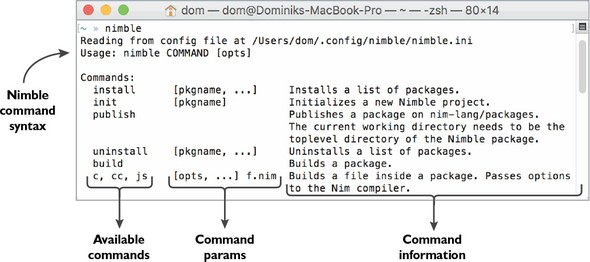

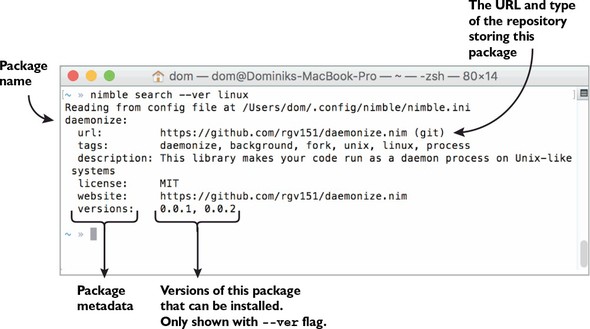

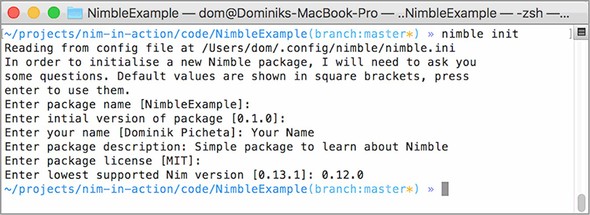

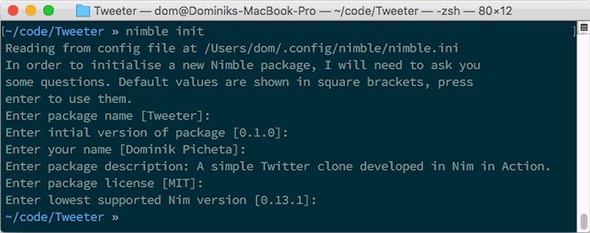

5.3. The nimble command-line tool

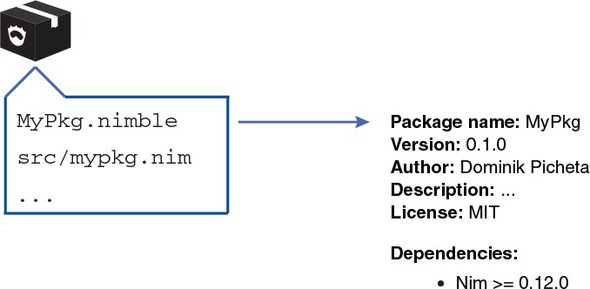

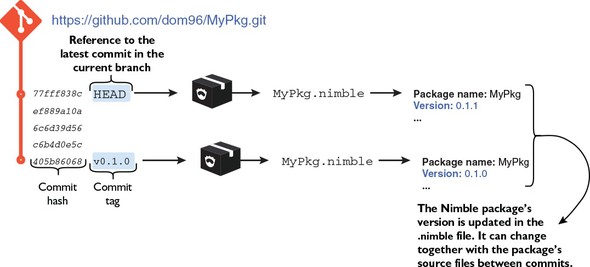

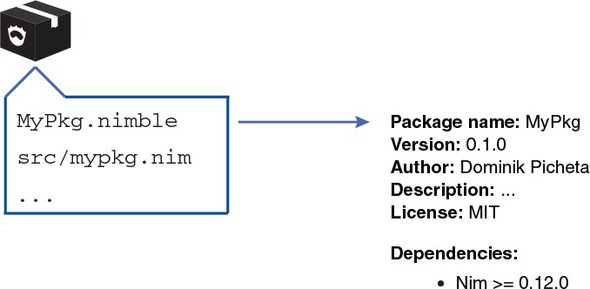

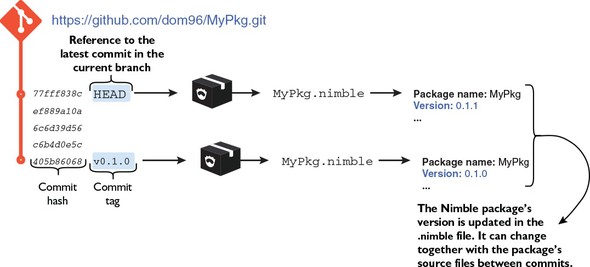

5.4. What is a Nimble package?

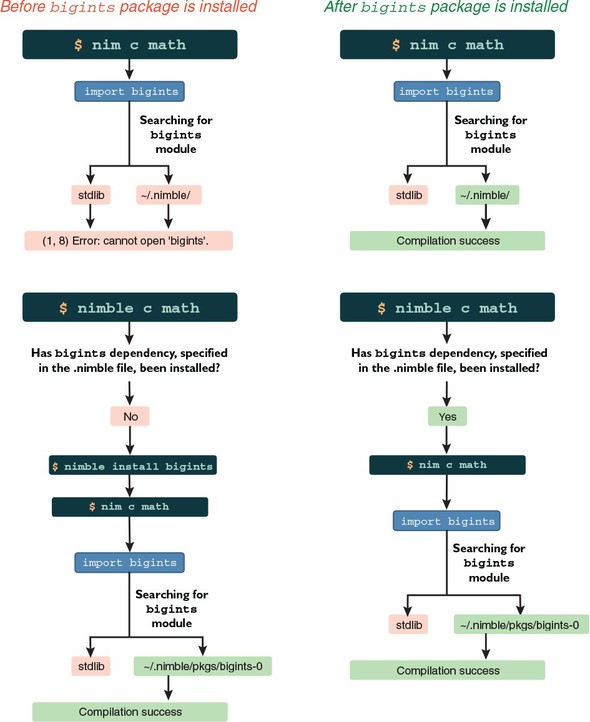

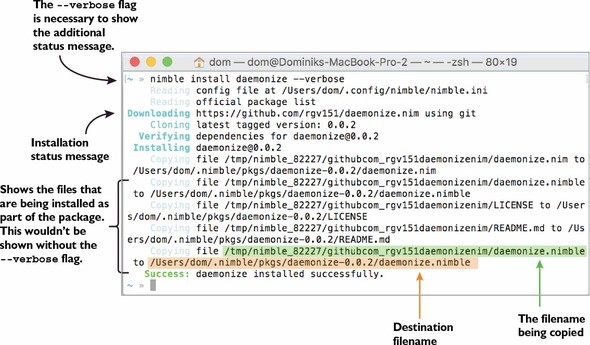

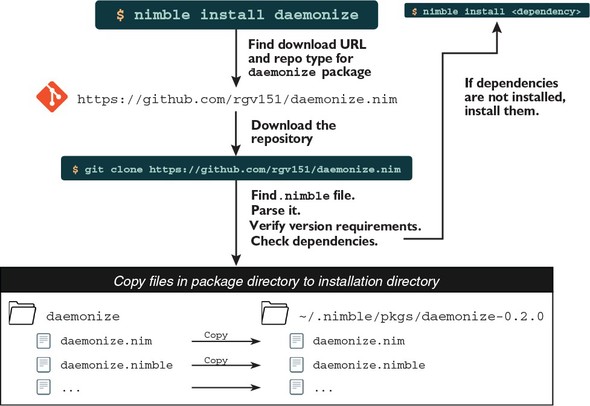

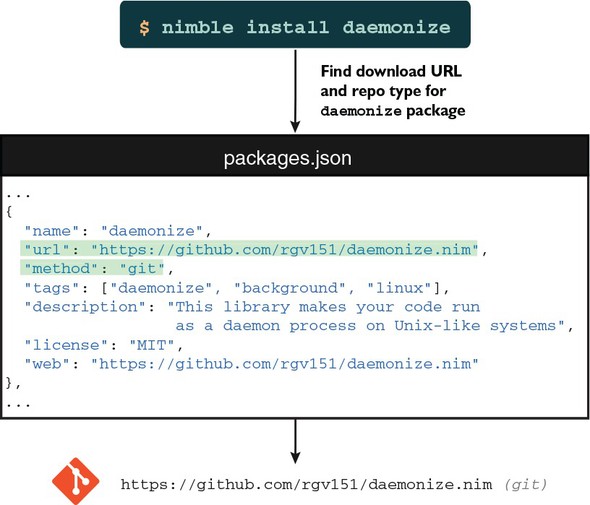

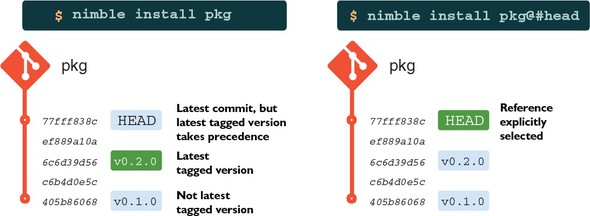

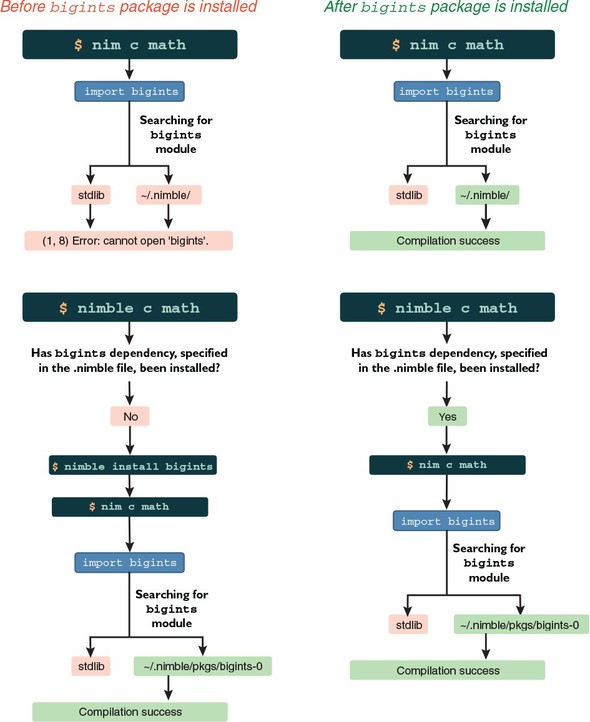

5.5. Installing Nimble packages

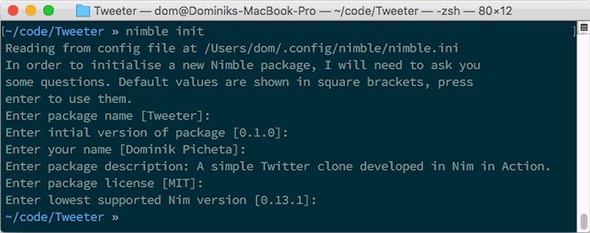

5.6. Creating a Nimble package

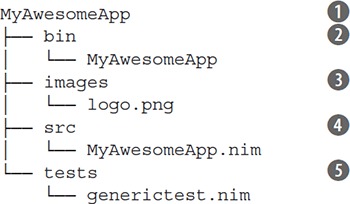

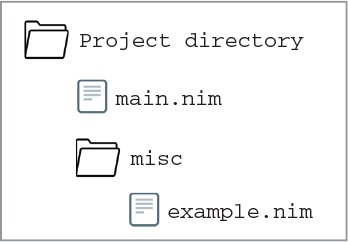

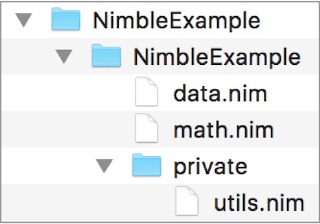

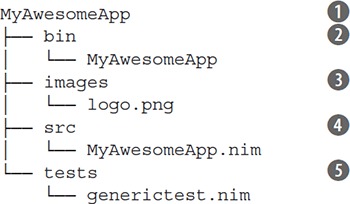

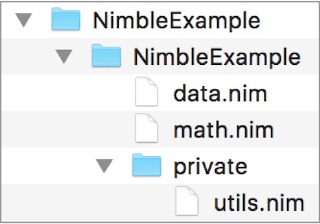

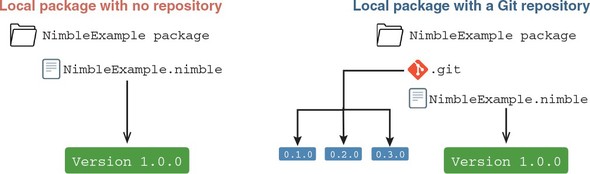

5.6.2. A Nimble package’s directory layout

5.6.3. Writing the .nimble file and sorting out dependencies

5.7. Publishing Nimble packages

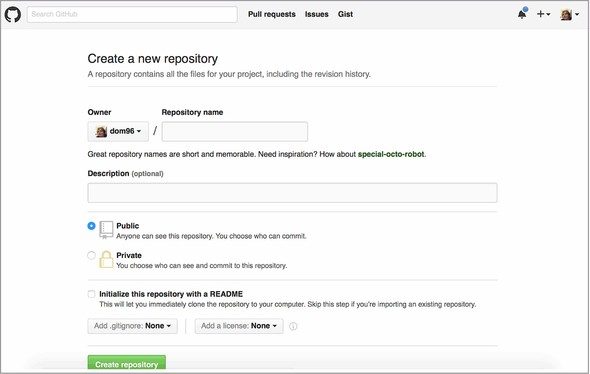

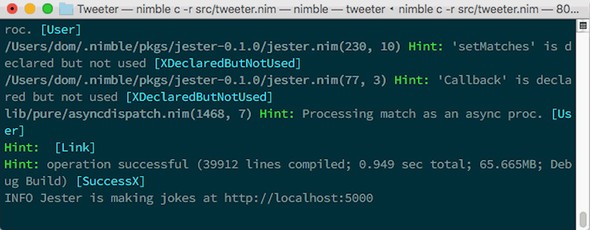

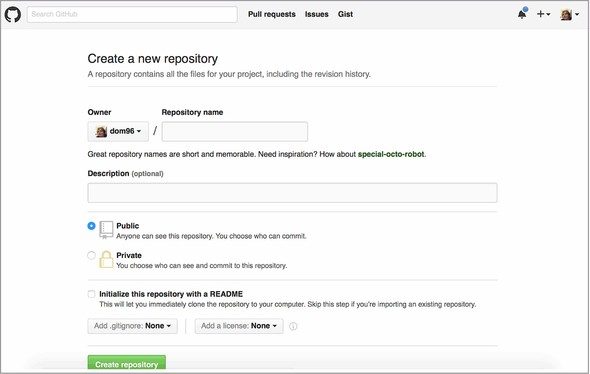

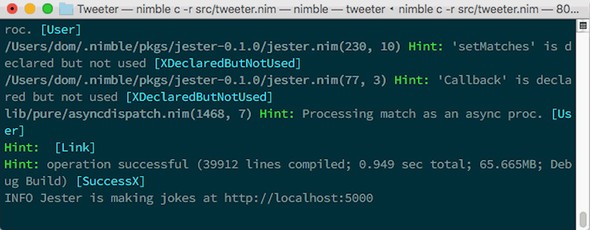

5.8. Developing a Nimble package

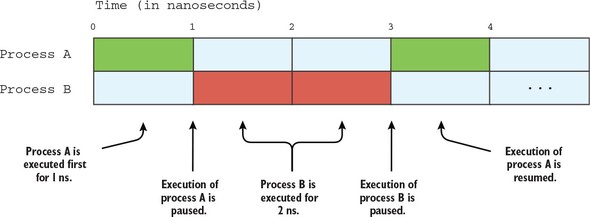

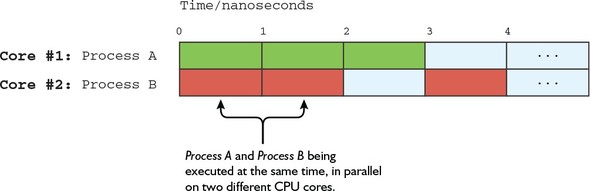

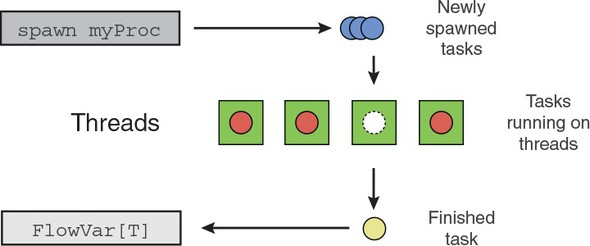

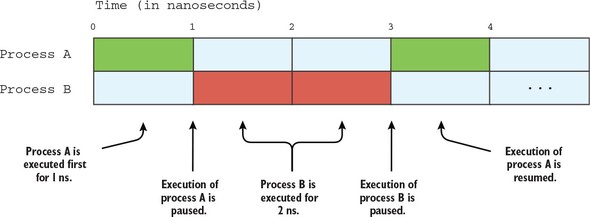

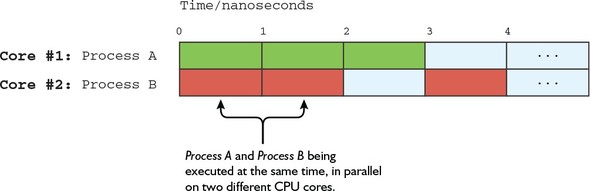

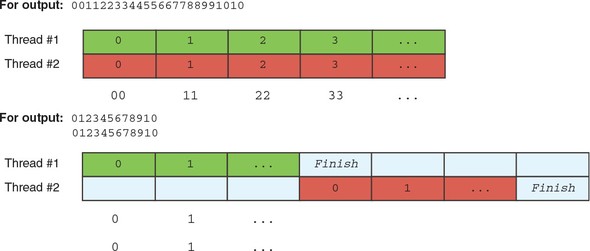

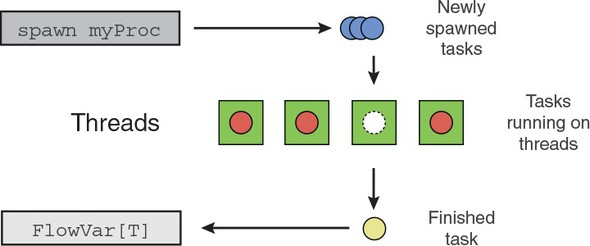

6.1. Concurrency vs. parallelism

6.3.1. Understanding the Wikipedia page-counts format

6.4.1. Measuring the execution time of sequential_counts

6.4.2. Parallelizing sequential_counts

6.4.3. Type definitions and the parse procedure

6.4.4. The parseChunk procedure

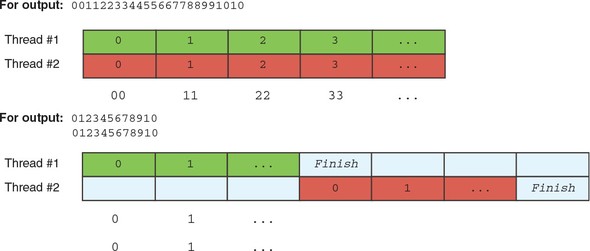

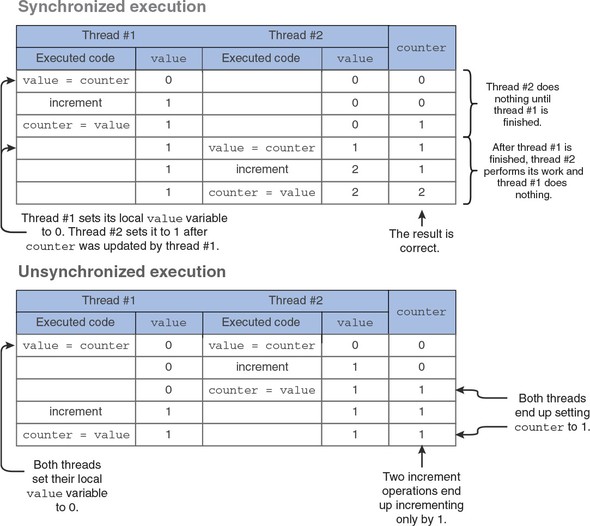

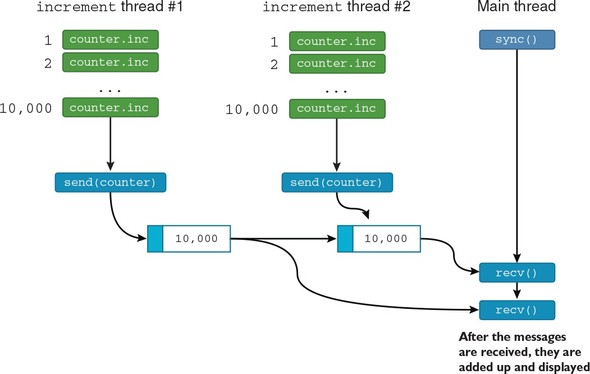

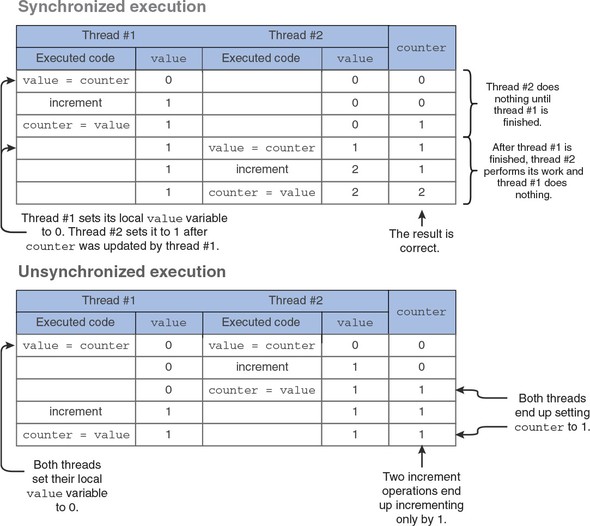

6.5. Dealing with race conditions

6.5.1. Using guards and locks to prevent race conditions

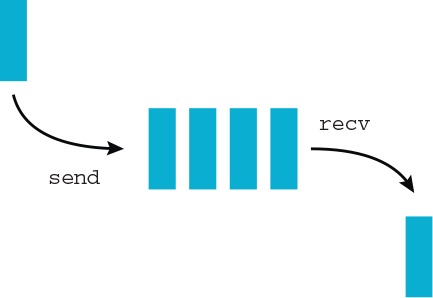

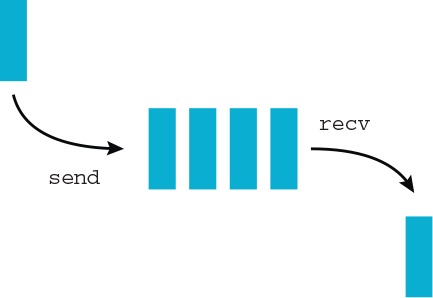

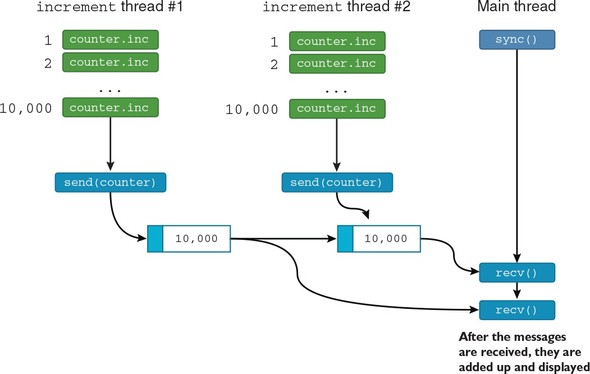

6.5.2. Using channels so threads can send and receive messages

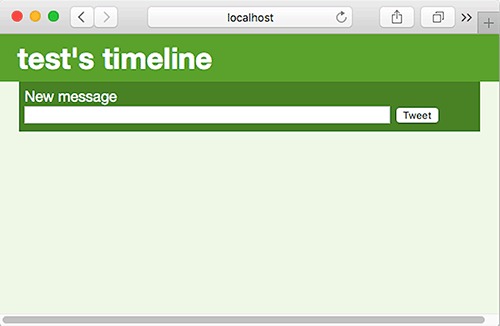

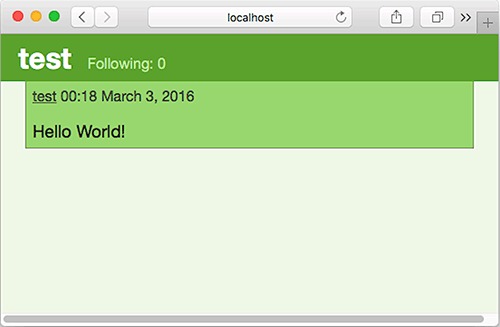

Chapter 7. Building a Twitter clone

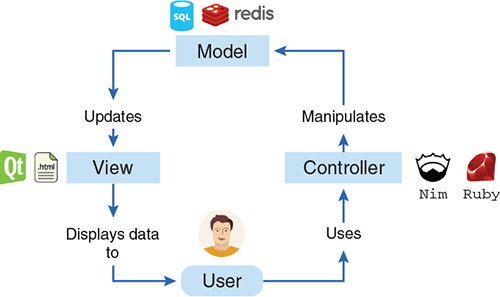

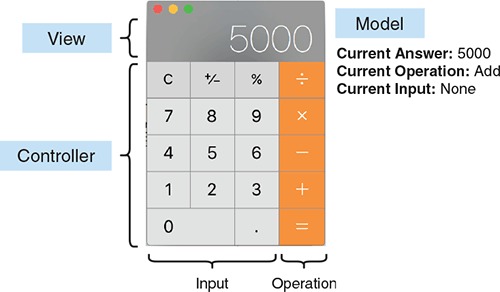

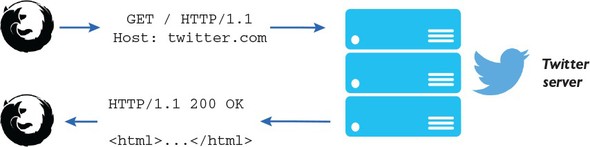

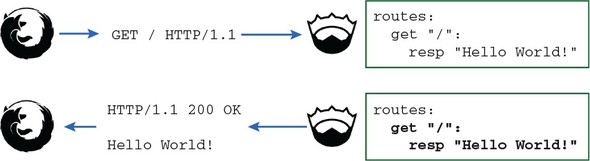

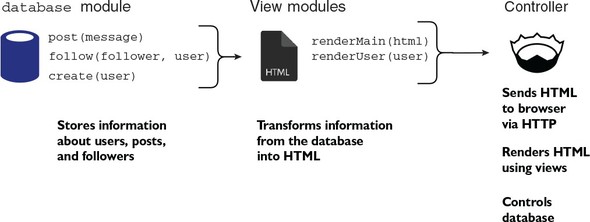

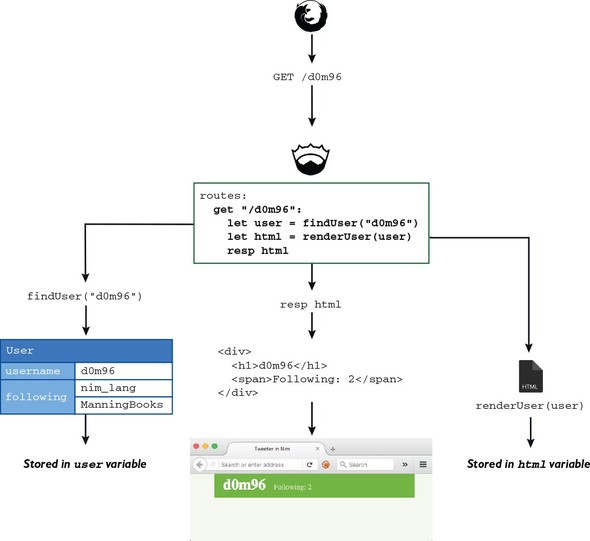

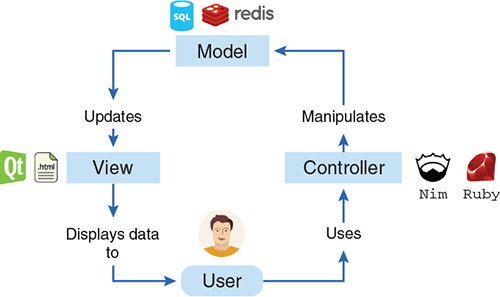

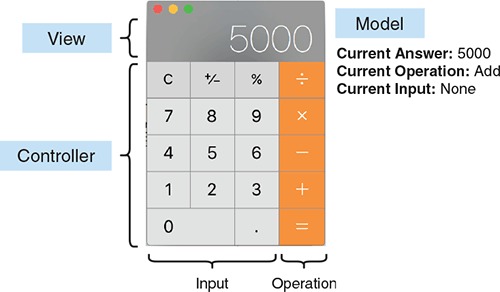

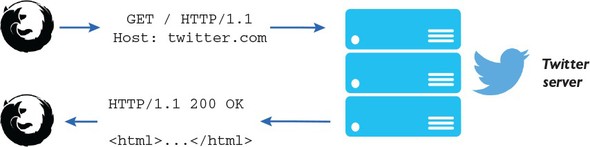

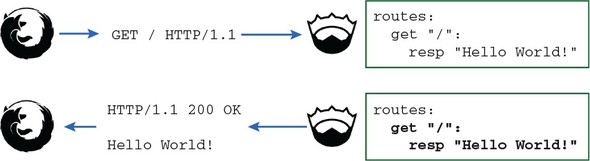

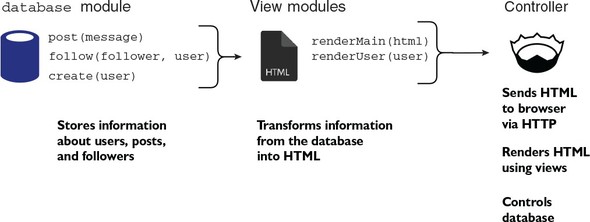

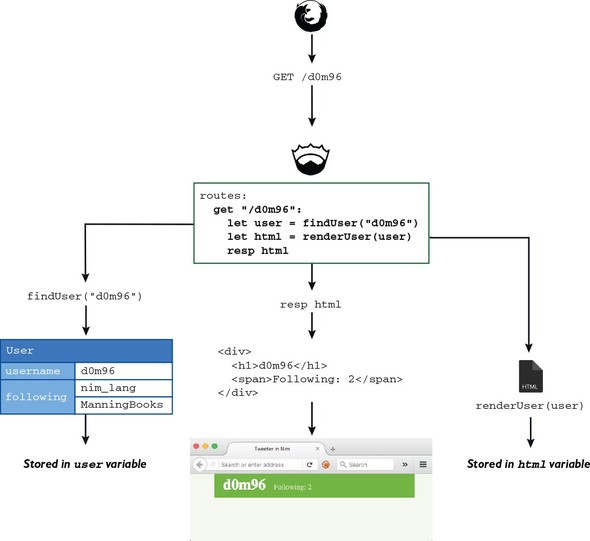

7.1. Architecture of a web application

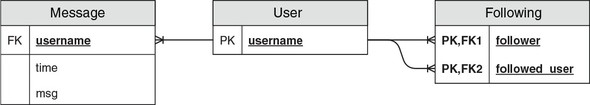

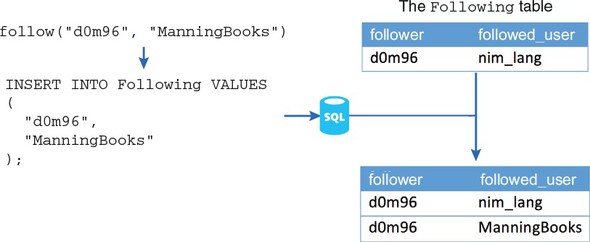

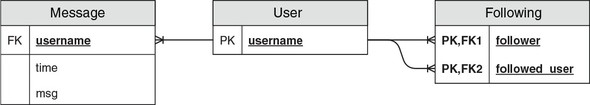

7.3. Storing data in a database

7.3.2. Setting up the database

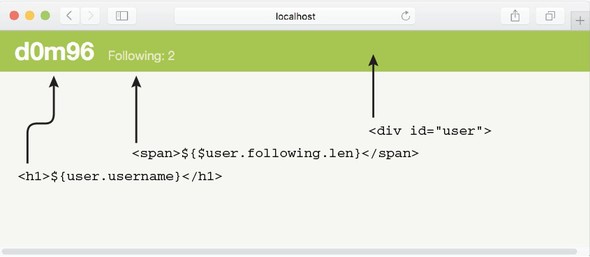

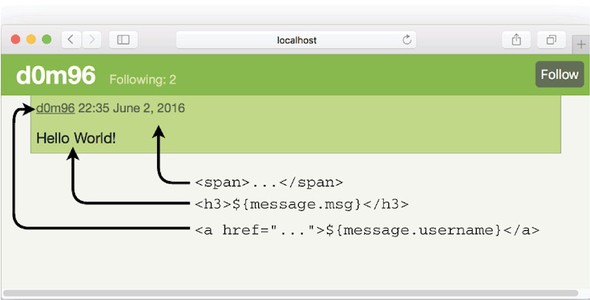

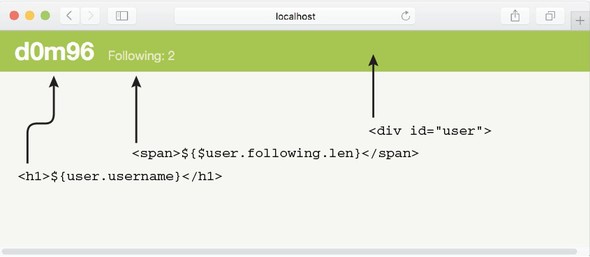

7.4. Developing the web application’s view

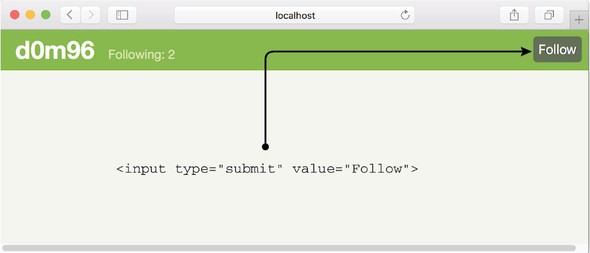

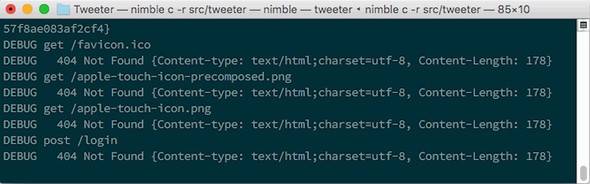

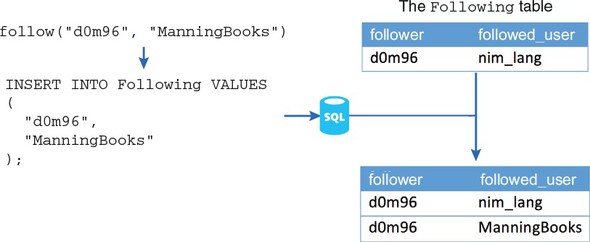

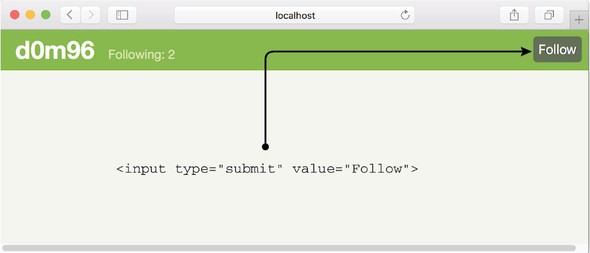

7.5. Developing the controller

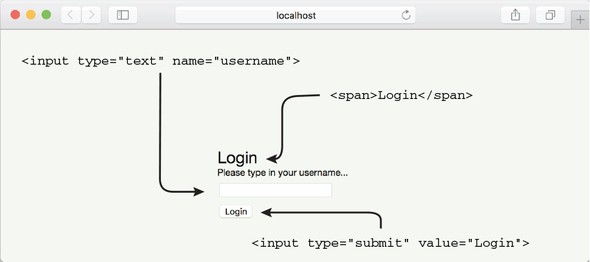

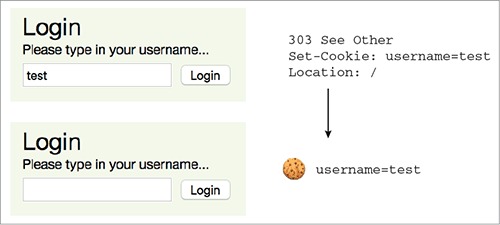

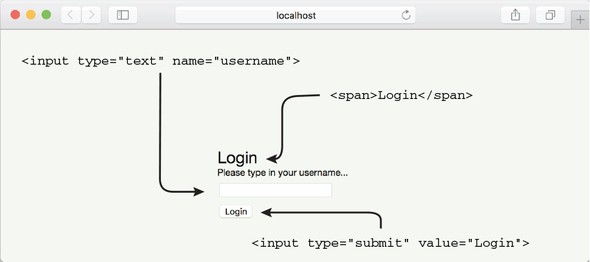

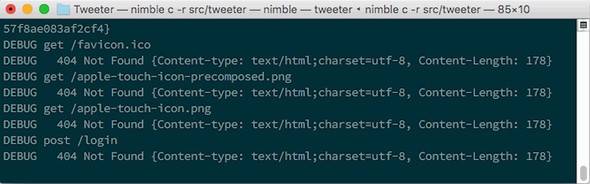

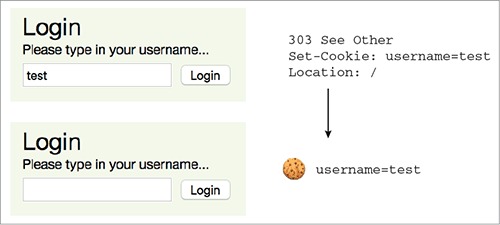

7.5.1. Implementing the /login route

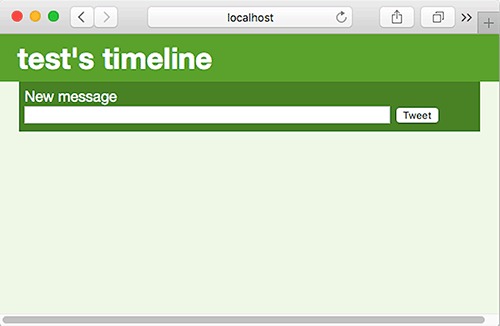

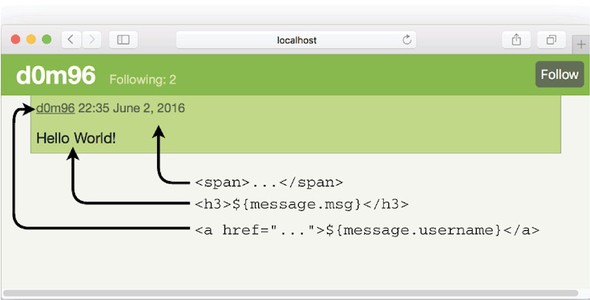

7.5.3. Implementing the /createMessage route

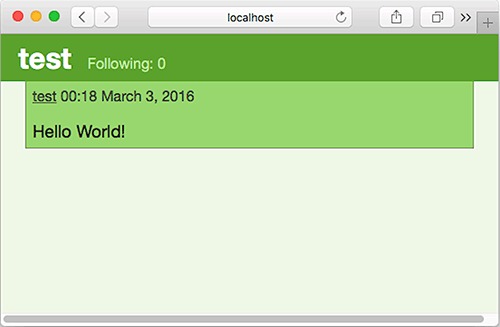

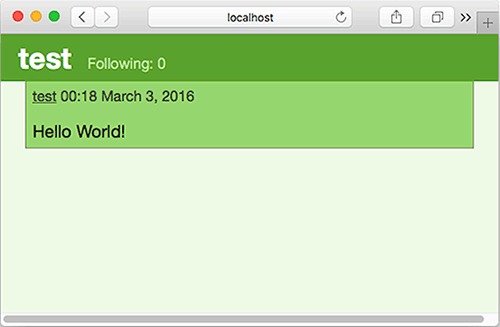

7.5.4. Implementing the user route

7.6. Deploying the web application

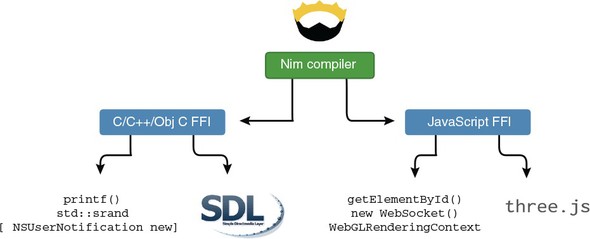

Chapter 8. Interfacing with other languages

8.1. Nim’s foreign function interface

8.2. Wrapping an external C library

8.2.1. Downloading the library

8.2.2. Creating a wrapper for the SDL library

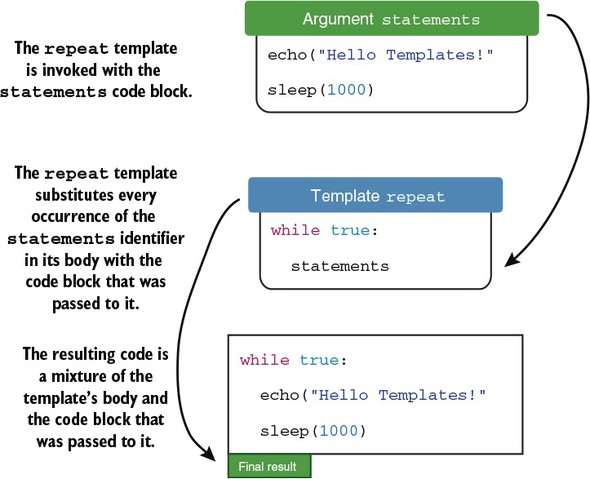

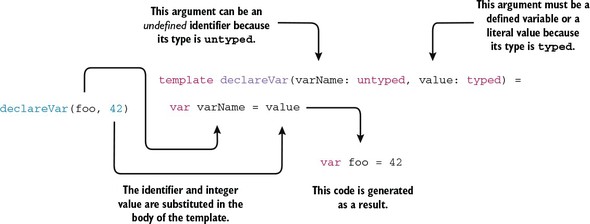

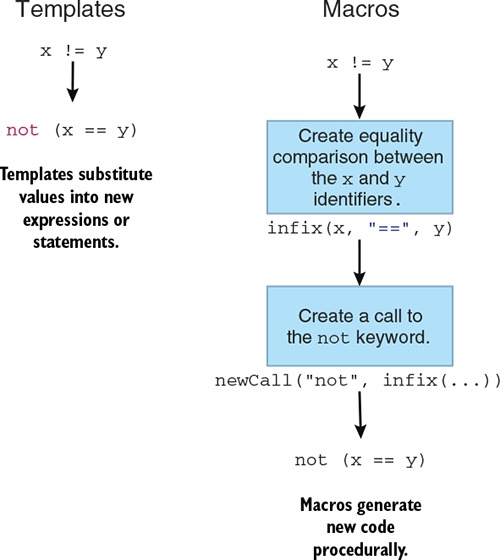

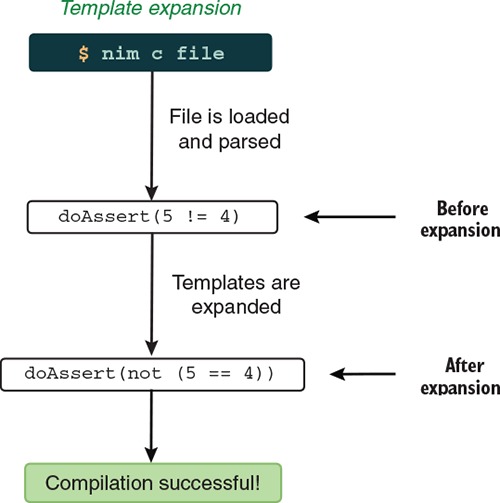

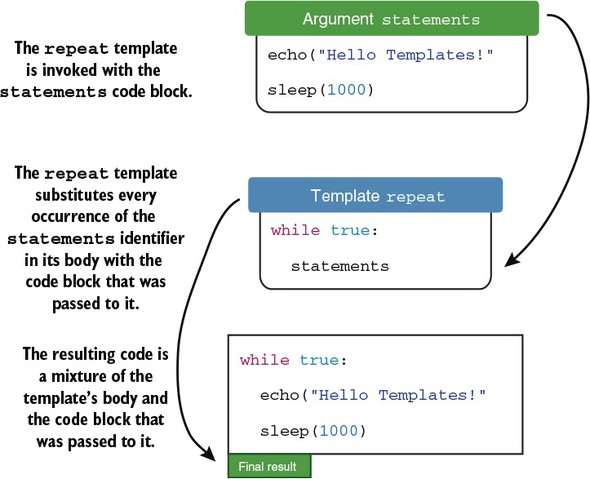

9.2.1. Passing a code block to a template

9.4. Creating a configuration DSL

9.4.1. Starting the configurator project

9.4.2. Generating the object type

9.4.3. Generating the constructor procedure

B.1. Installing the Nim compiler

B.2. Installing the Aporia IDE

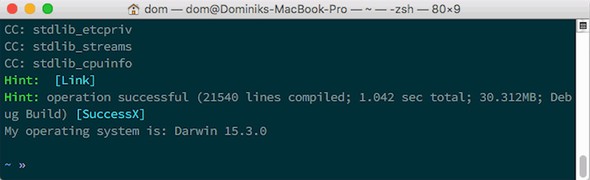

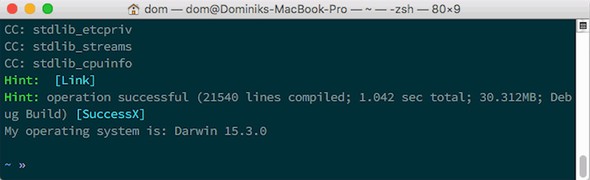

B.3. Testing your new development environment

Nim has been my labor of love over the years. Gradually, from the time I discovered it, I’ve become increasingly involved in its development. Although I sacrificed considerable time working on it, Nim gave back in the form of experience and knowledge. My work with Nim has taught me far more than any other work or studies have done. Many opportunities have also opened up for me, a shining example being this book.

I never actually thought I would end up writing a book, and until a Manning acquisitions editor got in touch with me, I didn’t realize that I wanted to. While planning this book, I looked to other books and determined where they fell short. I realized that this, the first book on Nim, must be written for programmers with a bit of experience. I decided that I wanted to write a book that teaches programmers about Nim, but that also teaches other programming concepts that work well in Nim’s particular programming paradigms. These concepts can also be applied to other programming languages and have been very useful in my career.

My other goal for this book was to make it fun and engaging. I decided to do this by building some chapters around small projects. The projects are designed to be practical and to teach a number of Nim features and concepts. By following along and developing these projects, you’ll gain hands-on experience developing Nim applications. This should put you in a good position to write your own software, which is the ultimate goal of this book.

Nim in Action covers a lot, but it can’t cover everything. It shouldn’t be viewed as a complete Nim reference; instead, it should be considered a practical guide to writing software in Nim.

It’s my hope that this book helps you learn Nim and that you find it a useful reference for many years to come. I and the Nim community are at your disposal and are available online to help you solve any problems you run into. Thank you for purchasing this book and taking an interest in Nim.

First, I would like to thank Andreas Rumpf for creating Nim and for both his reviews and words of encouragement throughout the development of this book. Andreas created a one-of-a-kind programming language, and without his commitment to Nim, this book wouldn’t exist.

This book wouldn’t be what it is today without the brilliant and passionate people at Manning publications. I give my thanks to Marjan Bace, who made it possible to publish this book; my editors Cynthia Kane, Dan Seiter, and Marina Michaels, for helping me improve my writing; and the production team, including Andy Carroll, Janet Vail, Karen Gulliver, and Katie Tennant.

I thank the Nim community and everyone who participated in reviews and provided feedback on the manuscript, including technical proofreader Michiel Trimpe, and the following reviewers: Andrea Ferretti, Yuriy Glukhov, Michał Zieliński, Stefan Salewski, Konstantin Molchanov, Sébastien Ménard, Abel Brown, Alessandro Campeis, Angelo Costa, Christoffer Fink, Cosimo Attanasi, James Anaipakos, Jonathan Rioux, Marleny Nunez, Mikkel Arentoft, Mohsen Mostafa Jokar, Paulo Nuin, Peter Hampton, Robert Walsh, Samuel Bosch, Thomas Ballinger, and Vincent Keller.

Thanks also to the readers of the Manning Early Access Program (MEAP). Their corrections and comments on the manuscript as it was being written were invaluable.

Finally, I’d like to thank my family and friends, who in their own way steered my life in a positive direction, leading me to authoring this book. First, I thank my mother, Bogumiła Picheta, for her bravery and hard work, without which I wouldn’t have had the means to start my programming journey, and I especially thank her for making a hard decision that turned out to be very beneficial for my future. I would also like to thank my uncle, Piotr Kossakowski-Stefański, and aunt, Marzena Kossakowska--Stefańska, for inspiring and challenging me to write software, and also for always being there to share their advice. Thanks to Ilona, Maciej Sr., and Maciej Jr. Łosinski for my first exposure to a computer and the internet. And I thank Kazimierz Ślebioda, a.k.a Kazik, for the Age of Empires 2 LAN parties and for showing me how delicious chicken with garlic can be.

Most of all, I thank my partner, Amy-Leigh Shaw, for always believing in me, and for her patience and support throughout my work on this book. I love you very much Amy, and am lucky to have you.

Nim in Action is a practical way to learn how to develop software using the open source Nim programming language. This book includes many examples, both large and small, to show and teach you how software is written in Nim.

Nim is unique. It’s multi-paradigm, and unlike most other languages, it doesn’t emphasize object-oriented programming. Because of this, I encourage you to consciously absorb the styles used in this book instead of applying your own. Nim in Action will teach you a set of best practices and idioms that you’ll also find useful in other programming languages.

By learning Nim, you’ll discover a language that straddles the lines between efficiency, expressiveness, and elegance. Nim will make you productive and your end users happy.

This is by no means a beginner’s book. It assumes that you know at least one other programming language and have experience writing software in it. For example, I expect you to be aware of basic programming language features such as functions, variables, and types. The fundamentals of programming aren’t explained in this book.

This book will teach you how to develop practical software in the Nim programming language. It covers features that are present in all programming languages, such as concurrency, parallelism, user-defined types, the standard library, and more. In addition, it covers Nim features that you may not be familiar with, such as asynchronous input/output, metaprogramming, and the foreign function interface.

The book is divided into three parts and includes a total of nine chapters.

Part 1 introduces the language and its basic features:

Part 2 includes a wide range of examples to show how Nim is used in practice:

Part 3 introduces some advanced Nim features:

You may wish to skip the first two chapters if you already know the basics of Nim. I recommend reading the book from beginning to end, and I especially encourage you to follow along with the examples. Each chapter teaches you something new about Nim, even if it primarily focuses on a standalone example. If you get stuck, feel free to get in touch with me or the Nim community. Appendix A contains information on how to get help, so use it to your advantage.

The source code examples in this book are fairly close to the samples that you’ll find online, but for the sake of brevity, many of the comments were removed. The online samples include a lot of comments to make them as easy to understand as possible, so you’re encouraged to take a look at them to learn more.

The source code is available for download from the publisher’s website at https://manning.com/books/nim-in-action and from GitHub at https://github.com/dom96/nim-in-action-code. Nim is still evolving, so be sure to watch the repository for changes. I’ll do my best to keep it up to date with the latest Nim version.

This book contains many examples of source code, both in numbered listings and inline with normal text. In both cases, source code is formatted in a mono-spaced typeface like this, to distinguish it from ordinary text. Sometimes code is also in bold to highlight code that has changed from previous steps in the chapter, such as when a new feature is added to existing code.

In many cases, the original source code has been reformatted for print; we’ve added line breaks and reworked the indentation

to accommodate the available page space in the book. In rare cases, even this was not enough, and listings include line-continuation

markers ( ). Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text.

). Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text.

The purchase of Nim in Action includes free access to a private web forum run by Manning Publications, where you can make comments about the book, ask technical questions, and receive help from the author and from other users. To access the forum, go to https://forums.manning.com/forums/nim-in-action. You can also learn more about Manning’s forums and the rules of conduct at https://forums.manning.com/forums/about.

Manning’s commitment to our readers is to provide a venue where a meaningful dialogue between individual readers and between readers and the author can take place. It is not a commitment to any specific amount of participation on the part of the author, whose contribution to the forum remains voluntary (and unpaid). We suggest you try asking him some challenging questions lest his interest stray! The forum and the archives of previous discussions will be accessible from the publisher’s website as long as the book is in print.

DOMINIK PICHETA (@d0m96, picheta.me) is a Computer Science student at Queen’s University Belfast. He is one of the core developers of the Nim programming language and has been using it for most of its history. He also wrote Nimble, the official Nim package manager, and many other Nim libraries and tools.

The figure on the cover of Nim in Action is captioned “Morlaque de l’Isle Opus,” or “A Morlach from the Island of Opus.” The Morlachs were a Vlach people originally centered around the eastern Adriatic port of Ragusa, or modern Dubrovnik. The illustration is taken from a collection of dress costumes from various countries by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur (1757–1810), titled Costumes de Différents Pays, published in France in 1797. Each illustration is finely drawn and colored by hand. The rich variety of Grasset de Saint-Sauveur’s collection reminds us vividly of how culturally apart the world’s towns and regions were just 200 years ago. Isolated from each other, people spoke different dialects and languages. In the streets or in the countryside, it was easy to identify where they lived and what their trade or station in life was just by their dress.

The way we dress has changed since then and the diversity by region, so rich at the time, has faded away. It is now hard to tell apart the inhabitants of different continents, let alone different towns, regions, or countries. Perhaps we have traded cultural diversity for a more varied personal life—certainly, for a more varied and fast-paced technological life.

At a time when it is hard to tell one computer book from another, Manning celebrates the inventiveness and initiative of the computer business with book covers based on the rich diversity of regional life of two centuries ago, brought back to life by Grasset de Saint-Sauveur’s pictures.

This part of the book begins your study of the Nim programming language. It doesn’t assume you know much about Nim, so chapter 1 begins by looking at the characteristics of the language, what makes it different from other languages, and how it’s used in the real world. Chapter 2 looks at some of the most commonly used elements of any programming language—the syntax, semantics, and type system—and in doing so teaches you the necessary foundations for writing simple applications in Nim.

This chapter covers

Nim is still a relatively new programming language. In fact, you’re holding one of the very first books about it. The language is still not fully complete, but core aspects, like its syntax, the semantics of procedures, methods, iterators, generics, templates, and more, are all set in stone. Despite its newness, there has been significant interest in Nim from the programming community because of the unique set of features that it implements and offers its users.

This chapter answers questions that you may ask before learning Nim, such as why you might want to use it. In this chapter, I outline some of the common practical uses of Nim, compare it to other programming languages, and discuss some of its strengths and weaknesses.

Nim is a general-purpose programming language designed to be efficient, expressive, and elegant. These three goals are difficult to achieve at the same time, so Nim’s designers gave each of them different priorities, with efficiency being the most important and elegance being the least.

But despite the fact that elegance is relatively unimportant to Nim’s design, it’s still considered during the design process. Because of this, the language remains elegant in its own right. It’s only when trade-offs between efficiency and elegance need to be made that efficiency wins.

On the surface, Nim shares many of Python’s characteristics. In particular, many aspects of Nim’s syntax are similar to Python’s, including the use of indentation to delimit scope as well as the tendency to use words instead of symbols for certain operators. Nim also shares other aspects with Python that aren’t related to syntax, such as the highly user-friendly exception tracebacks, shown here:

Traceback (most recent call last) request.nim(74) request request.nim(25) getUsers json.nim(837) [] tables.nim(147) [] Error: unhandled exception: key not found: totalsForAllResults [KeyError]

You’ll also see many differences, especially when it comes to the semantics of the language. The major differences lie within the type system and execution model, which you’ll learn about in the next sections.

Andreas Rumpf started developing Nim in 2005. The project soon gained support and many contributions from the open source community, with many volunteers around the world contributing code via pull requests on GitHub. You can see the current open Nim pull requests at https://github.com/nim-lang/Nim/pulls.

The compiler, standard library, and related tools are all open source and written in Nim. The project is available on GitHub, and everyone is encouraged to contribute. Contributing to Nim is a good way to learn how it works and to help with its development. See Nim’s GitHub page for more information: https://github.com/nim-lang/Nim#contributing.

Nim was designed to be a general-purpose programming language from the outset. As such, it consists of a wide range of features that make it usable for just about any software project. This makes it a good candidate for writing software in a wide variety of application domains, ranging from web applications to kernels. In this section, I’ll discuss how Nim’s features and programming support apply in several use cases.

Although Nim may support practically any application domain, this doesn’t make it the right choice for everything. Certain aspects of the language make it more suitable for some categories of applications than others. This doesn’t mean that some applications can’t be written using Nim; it just means that Nim may not support the code styles that are best suited for writing some kinds of applications.

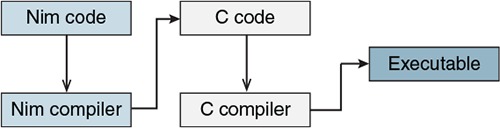

Nim is a compiled language, but the way in which it’s compiled is special. When the Nim compiler compiles source code, it first translates the code into C code. C is an old but well supported systems programming language that allows easier and more direct access to the physical hardware of the machine. This makes Nim well suited to systems programming, allowing projects such as operating systems (OSs), compilers, device drivers, and embedded system software to be written.

Internet of Things (IoT) devices, which are physical devices with embedded electronics that are connected to the internet, are good targets for Nim, primarily thanks to the power offered by Nim’s ease of use and its systems programming capabilities.

A good example of a project making use of Nim’s systems programming features is a very simple OS called NimKernel available on GitHub: https://github.com/dom96/nimkernel.

I describe Nim’s unusual compilation model and its benefits in detail in section 1.1.3.

Applications written in Nim are very fast; in many cases, just as fast as applications written in C, and more than thirteen times faster than applications written in Python. Efficiency is the highest priority, and some features make optimizing code easy. This goes hand in hand with a soft real-time garbage collector, which allows you to specify the amount of time that should be spent collecting memory. This feature becomes important during game development, where an ordinary garbage collector may slow down the rendering of frames on the screen if it uses too much time collecting memory. It’s also useful in real-time systems that need to run in very strict time frames.

Nim can be used alongside other much slower languages to speed up certain performance-critical components. For example, an application written in Ruby that requires certain CPU-intensive calculations can be partially written in Nim to gain a considerable speed advantage. Such speed-ups are important in areas such as scientific computing and high-speed trading.

Applications that perform I/O operations, such as reading files or sending data over a network, are also well supported by Nim. Web applications, for example, can be written easily using a number of web frameworks like Jester (https://github.com/dom96/jester). Nim’s script-like syntax, together with its powerful, asynchronous I/O support, makes it easy to develop these applications rapidly.

Command-line applications can benefit greatly from Nim’s efficiency. Also, because Nim applications are compiled, they’re standalone and so don’t require any bulky runtime dependencies. This makes their distribution incredibly easy. One such application written in Nim is Nimble; it’s a package manager for Nim that allows users to install Nim libraries and applications.

These are just a few use cases that Nim fits well; it’s certainly not an exhaustive list.

Another thing to keep in mind is that, at the time of writing, Nim is still in development, not having yet reached version 1.0. Certain features haven’t been implemented yet, making Nim less suited for some applications. For example, Nim includes a backend that allows you to write JavaScript applications for your web pages in Nim. This backend works, but it’s not yet as mature as the rest of the language. This will improve with time.

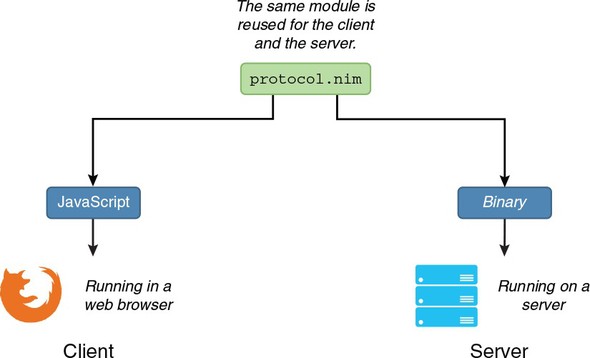

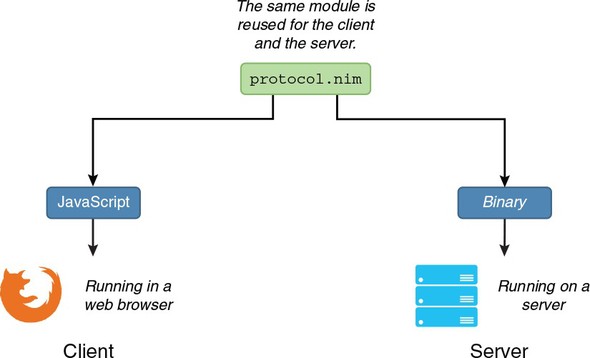

Of course, Nim’s ability to compile to JavaScript makes it suitable for full-stack applications that need components that run on a server and in a browser. This is a huge advantage, because code can easily be reused for both the browser and server components of the application.

Now that you know a little bit about what Nim is, its history, and some of the applications that it’s particularly well suited for, let’s look at some of Nim’s features and talk about how it works.

In many ways, Nim is very innovative. Many of Nim’s features can’t be found in any other programming language. If you enjoy learning new programming languages, especially those with interesting and unique features, then Nim is definitely the language for you.

In this section, we’ll look at some of the core features of Nim—in particular, the features that make Nim stand out from other programming languages:

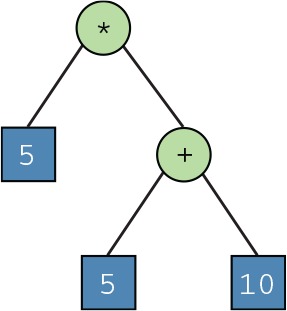

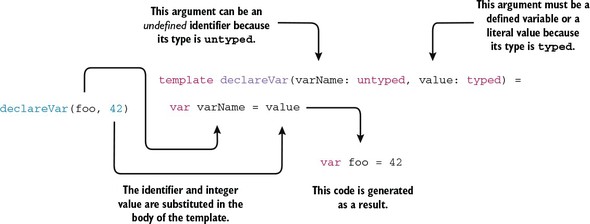

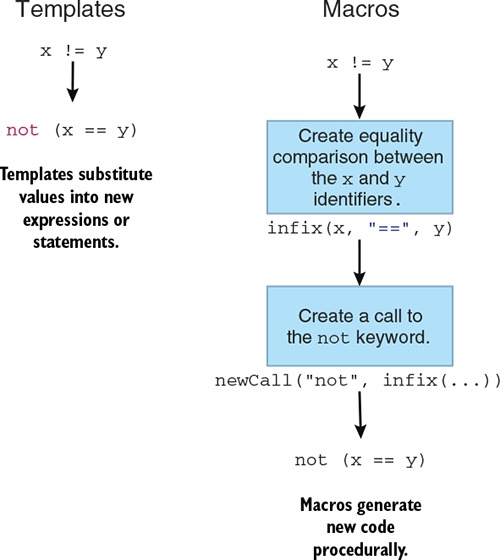

The most practical, and in some senses unique, feature of Nim is its extensive metaprogramming support. Metaprogramming allows you to read, generate, analyze, and transform source code. It was by no means a Nim invention, but there’s no other programming language with metaprogramming that’s so extensive and at the same time easy to pick up as Nim’s. If you’re familiar with Lisp, then you might have some experience with metaprogramming already.

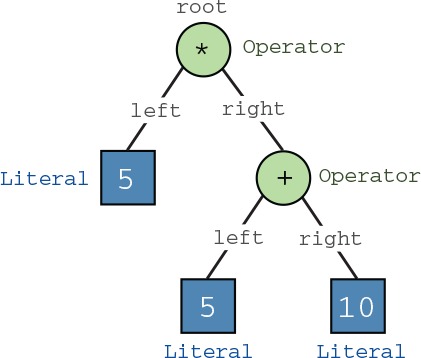

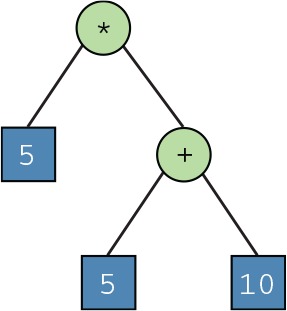

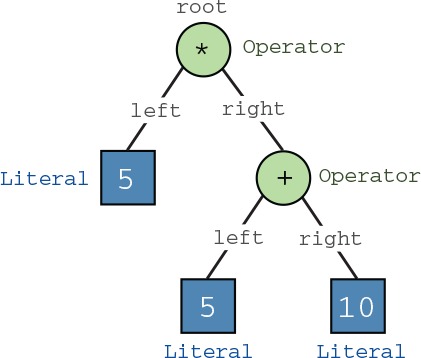

With metaprogramming, you treat code as data in the form of an abstract syntax tree. This allows you to manipulate existing code as well as generate brand new code while your application is being compiled.

Metaprogramming in Nim is special because languages with good metaprogramming features typically belong to the Lisp family of languages. If you’re already familiar with the likes of Java or Python, you’ll find it easier to start using Nim than Lisp. You’ll also find it more natural to learn how to use Nim’s metaprogramming features than Lisp’s.

Although it’s generally an advanced topic, metaprogramming is a very powerful feature that you’ll get to know in far more detail in chapter 9 of this book. One of the main benefits that metaprogramming offers is the ability to remove boilerplate code. Metaprogramming also allows the creation of domain-specific languages (DSLs); for example,

html:

body:

p: "Hello World"

This DSL specifies a bit of HTML code. Depending on how it’s implemented, the DSL will likely be translated into Nim code resembling the following:

echo("<html>")

echo(" <body>")

echo(" <p>Hello World</p>")

echo(" </body>")

echo("</html>")

That Nim code will result in the following output:

<html>

<body>

<p>Hello World</p>

</body>

</html>

With Nim’s metaprogramming, you can define DSLs and mix them freely with your ordinary Nim code. Such languages have many use cases; for example, the preceding one can be used to create HTML templates for your web apps.

Metaprogramming is at the center of Nim’s design. Nim’s designer wants to encourage users to use metaprogramming in order to accommodate their style of programming. For example, although Nim does offer some object-oriented programming (OOP) features, it doesn’t have a class definition construct. Instead, anyone wishing to use OOP in Nim in a style similar to that of other languages should use metaprogramming to create such a construct.

Another of Nim’s interesting and likely unique features is style insensitivity. One of the hardest things a programmer has to do is come up with names for all sorts of identifiers like variables, functions, and modules. In many programming languages, these names can’t contain whitespace, so programmers have been forced to adopt other ways of separating multiple words in a single name. Multiple differing methods were devised, the most popular being snake_case and camelCase. With Nim, you can use snake_case even if the identifier has been defined using camelCase, and vice versa. So you can write code in your preferred style even if the library you’re using adopted a different style for its identifiers.

import strutils 1

echo("hello".to_upper()) 2

echo("world".toUpper()) 3

This works because Nim considers the identifiers to_upper and toUpper to be equal.

When comparing identifiers, Nim considers the case of the first character, but it doesn’t bother with the case of the rest of the identifier’s characters, ignoring the underscores as well. As a result, the identifiers toUpper and ToUpper aren’t equal because the case of the first character differs. This allows type names to be distinguished from variable names, because, by convention, type names should start with an uppercase letter and variable names should start with a lowercase letter.

The following listing shows one scenario where this convention is useful.

type

Dog = object 1

age: int 2

let dog = Dog(age: 3) 3

One of the many characteristics that differentiate programming languages from one another is their type system. The main purpose of a type system is to reduce the opportunities for bugs in your programs. Other benefits that a good type system provides are certain compiler optimizations and better documentation of code.

The main categories used to classify type systems are static and dynamic. Most programming languages fall somewhere between the two extremes and incorporate ideas from both. This is because both static and dynamic type systems require certain trade-offs. Static typing finds more errors at compile time, but it also decreases the speed at which programs can be written. Dynamic typing is the opposite.

Nim is statically typed, but unlike some statically typed programming languages, it also incorporates many features that make development fast. Type inference is a good example of that: types can be resolved by the compiler without the need for you to write the types out yourself (though you can choose to). Because of that, your program can be bug-free and yet your development speed isn’t hindered. Nim also incorporates some dynamic type-checking features, such as runtime type information, which allows for the dynamic dispatch of functions.

One way that a type system ensures that your program is free of bugs is by verifying memory safety. Some programming languages, like C, aren’t memory safe because they allow programs to access memory that hasn’t been assigned for their use. Other programming languages are memory safe at the expense of not allowing programs to access low-level details of memory, which in some cases is necessary. Nim combines both: it’s memory safe as long as you don’t use any of the unsafe types, such as ptr, in your program, but the ptr type is necessary when interfacing with C libraries. Supporting these unsafe features makes Nim a powerful systems programming language.

By default, Nim protects you against every type of memory error:

Finally, one of the most important features of Nim’s type system is the ability to use generic programming. Generics in Nim allow for a great deal of code reuse without sacrificing type safety. Among other things, they allow you to specify that a single function can accept multiple different types. For example, you may have a showNumber procedure that displays both integers and floats on the screen:

proc showNumber(num: int | float) = echo(num) showNumber(3.14) showNumber(42)

Here, the showNumber procedure accepts either an int type or a float type. The | operator specifies that both int and float can be passed to the procedure.

This is a simple demonstration of Nim’s generics. You’ll learn a lot more about Nim’s type system, as well as its generics, in later chapters.

I mentioned in the previous section that the Nim compiler compiles source code into C first, and then feeds that source code into a C compiler. You’ll learn a lot more about how this works in section 1.1.3, but right now I’ll talk about some of the many practical advantages of this compilation model.

The C programming language is very well established as a systems programming language and has been in use for over 40 years. C is one of the most portable programming languages, with multiple implementations for Windows, Linux, Mac OS, x86, AMD64, ARM, and many other, more obscure OSs and platforms. C compilers support everything from supercomputers to microcontrollers. They’re also very mature and implement many powerful optimizations, which makes C very efficient.

Nim takes advantage of these aspects of C, including its portability, widespread use, and efficiency.

Compiling to C also makes it easy to use existing C and C++ libraries—all you need to do is write some simple wrapper code. You can write this code much faster by using a tool called c2nim. This tool converts C and C++ header files to Nim code, which wraps those files. This is of great benefit because many popular libraries are written in C and C++.

Nim also offers you the ability to build libraries that are compatible with C and C++. This is handy if you want your library to be used from other programming languages. You’ll learn all about wrapping C and C++ libraries in chapter 8.

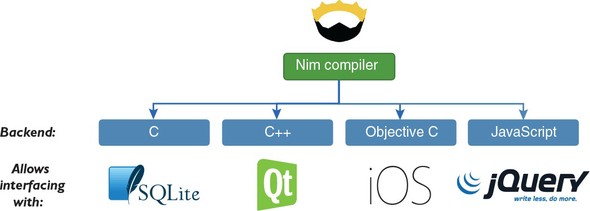

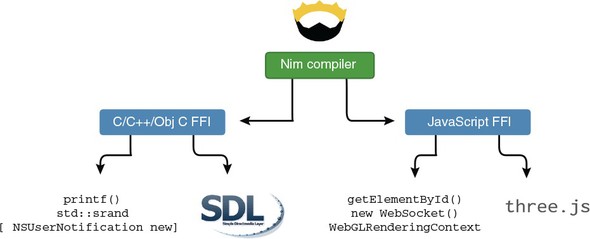

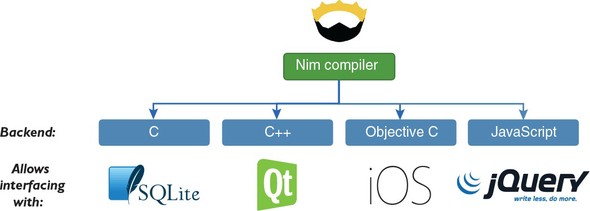

Nim source code can also be compiled into Objective C and JavaScript. The Objective C language is mainly used for iOS software development; by compiling to it, you can write iOS applications natively in Nim. You can also use Nim to develop Android applications by using the C++ compilation backend. JavaScript is the client-side language used by billions of websites; it’s sometimes called the “assembly language of the web” because it’s the only programming language that’s supported by all the major web browsers. By compiling to JavaScript, you can write client-side applications for web browsers in Nim. Figure 1.1 shows the available Nim backends.

You may now be wondering just how fast Nim is at compiling software. Perhaps you’re thinking that it’s very slow; after all, Nim needs to translate source code to an intermediate language first. But in fact it’s fairly fast. As an example, the Nim compiler, which consists of around 100,000 lines of Nim code, takes about 12 seconds to compile on a MacBook Pro with a 2.7 GHz Intel Core i5 CPU. Each compilation is cached, so the time drops to 5 seconds after the initial compilation.

C and C++ both require you to manually manage memory, carefully ensuring that what you allocate is deallocated once it’s no longer needed. Nim, on the other hand, manages memory for you using a garbage collector. But there are situations when you may want to avoid garbage collectors; they’re considered by many to be inadequate for certain application domains, like embedded systems and games. For this reason, Nim supports a number of different garbage collectors with different applications in mind. The garbage collector can also be removed completely, giving you the ability to manage memory yourself.

Switching between garbage collectors is easy. You just need to specify the --gc:<gc_name> flag during compilation and replace <gc_name> with markandsweep, boehm, or none.

This was just a small taste of Nim’s most prominent features. There’s a lot more to it: not just the unique and innovative features, but also the unique composition of features from existing programming languages that makes Nim as a whole very unique indeed.

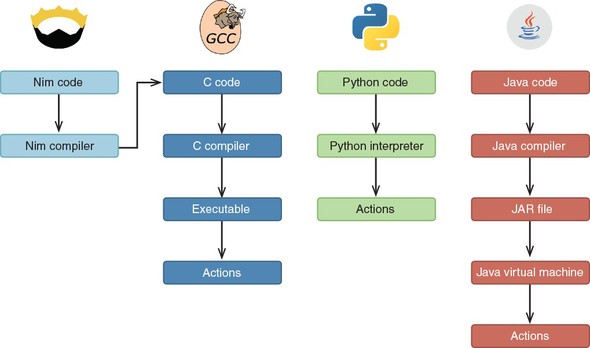

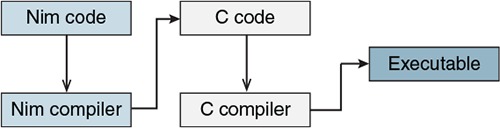

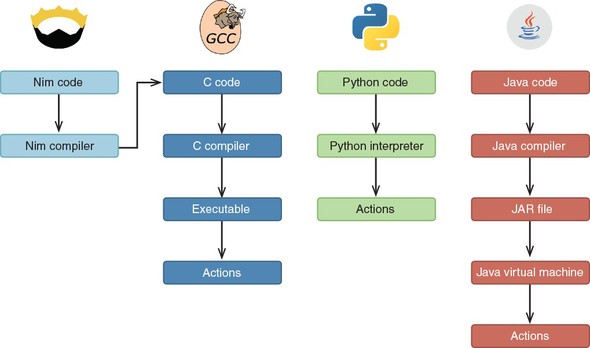

One of the things that makes Nim unique is its implementation. Every programming language has an implementation in the form of an application, which either interprets the source code or compiles the source code into an executable. These implementations are called an interpreter and a compiler, respectively. Some languages may have multiple implementations, but Nim’s only implementation is a compiler. The compiler compiles Nim source code by first translating the code to another programming language, C, and then passing that C source code to a C compiler, which then compiles it into a binary executable. The executable file contains instructions that indicate the specific tasks that the computer should perform, including the ones specified in the original Nim source code. Figure 1.2 shows how a piece of Nim code is compiled into an executable.

The compilers for most programming languages don’t have this extra step; they compile the source code into a binary executable themselves. There are also others that don’t compile code at all. Figure 1.3 shows how different programming languages transform source code into something that can be executed.

Nim connects to the C compilation process in order to compile the C source code that was generated by it. This means that the Nim compiler depends on an external C compiler, such as GCC or Clang. The result of the compilation is an executable that’s specific to the CPU architecture and OS it was compiled on.

This should give you a good idea of how Nim source code is transformed into a working application, and how this process is different from the one used in other programming languages. Every time you make a change to your Nim source code, you’ll need to recompile it.

Now let’s look at Nim’s positive and negative aspects.

It’s important to understand why you might want to use a language, but it’s just as important to learn why that language may not be correct for your particular use case.

In this section, I’ll compare Nim to a number of other programming languages, focusing on a variety of characteristics and factors that are typically used in such comparisons. After that, I’ll discuss some of the areas where Nim still needs to catch up with other languages.

As you read this book, you may wonder how Nim compares to the programming languages that you’re familiar with. There are many ways to draw a comparison and multiple factors that can be considered, including the language’s execution speed, expressiveness, development speed, readability, ecosystem, and more. This section looks at some of these factors to give you a better idea of the benefits of Nim.

The speed at which applications written in a programming language execute is often used in comparisons. One of Nim’s goals is efficiency, so it should be no surprise that it’s a very efficient programming language.

C is one of the most efficient programming languages, so you may be wondering how Nim compares. In the previous section, you learned that the Nim compiler first translates Nim code into an intermediate language. By default, the intermediate language is C, which suggests that Nim’s performance is similar to C’s, and that’s true.

Because of this feature, you can use Nim as a complete replacement for C, with a few bonuses:

In comparison to C, metaprogramming in Nim is unique, as it doesn’t use a preprocessor but is instead a part of the main compilation process. In general, you can expect to find many modern features in Nim that you won’t find in C, so picking Nim as a C replacement makes a lot of sense.

Table 1.1 shows the results of a small benchmark test.[1] Nim matches C’s speed and is significantly faster than Python.

You can read more about this benchmark test on Dennis Felsing’s HookRace blog: http://hookrace.net/blog/what-is-special-about-nim/#good-performance.

|

Programming language |

Time (seconds) |

|---|---|

| C | 2.6 |

| Nim | 2.6 |

| Python (CPython) | 35.1 |

In this benchmark, the Nim application’s runtime matches the speed of the C app and is significantly faster than the app implemented in Python. Micro benchmarks such as this are often unreliable, but there aren’t many alternatives. Nim’s performance matches that of C, which is already one of the most efficient programming languages out there.

Nim is a very expressive language, which means that it’s easy to write Nim code that’s clear to both the compiler and the human reader. Nim code isn’t cluttered with the curly brackets and semicolons of C-like programming languages, such as JavaScript and C++, nor does it require the do and end keywords that are present in languages such as Ruby.

Compare this expressive Nim code with the less-expressive C++ code

for i in 0 .. <10: echo(i)

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

cout << i << endl;

}

return 0;

}

The Nim code is more readable and far more compact. The C++ code contains many elements that are optional in Nim, such as the main function declaration, which is entirely implicit in Nim.

Nim is easy to write but, more importantly, it’s also easy to read. Good code readability goes a long way. For example, it makes debugging easier, allowing you to spend more time writing beautiful Nim code, cutting down your development time.

This has been mentioned already, but it’s worth revisiting to describe how other languages compare, and in particular why some require a runtime.

Compiled programming languages such as Nim, C, Go, D, and Rust produce an executable that’s native to the OS on which the compiler is running. Compiling a Nim application on Windows results in an executable that can only be executed on Windows. Similarly, compiling it on Mac OS results in an executable that can only be executed on Mac OS. The CPU architecture also comes into play: compilation on ARM results in an executable that’s only compatible with ARM CPUs. This is how things work by default, but it’s possible to instruct Nim to compile an executable for a different OS and CPU combination through a process known as cross-compilation.

Cross-compilation is usually used when a computer with the desired architecture or OS is unavailable, or the compilation takes too long. One common use case would be compiling for ARM devices such as the Raspberry Pi, where the CPU is typically slow. More information about cross-compilation can be found in the Nim Compiler User Guide: http://nim-lang.org/docs/nimc.html#cross-compilation.

Among other things, the JVM was created to remove the need for cross-compilation. You may have heard the phrase “write once, run anywhere.” Sun Microsystems created this slogan to illustrate Java’s cross-platform benefits. A Java application only needs to be compiled once, and the result of this compilation is a JAR file that holds all the compiled Java classes. The JAR file can then be executed by the JVM to perform the programmed actions on any platform and architecture. This makes the JAR file a platform and architecture-agnostic executable. The downside to this is that in order to run these JAR files, the JVM must be installed on the user’s system. The JVM is a very big dependency that may contain bugs and security issues. But on the other hand, it does allow the Java application to be compiled only once.

Python, Ruby, and Perl are similar. They also use a virtual machine (VM) to execute code. In Python’s case, a VM is used to optimize the execution of Python code, but it’s mostly hidden away as an implementation detail of the Python interpreter. The Python interpreter parses the code, determines what actions that code is describing, and immediately executes those actions. There’s no compilation step like with Java, C, or Nim. But the advantages and disadvantages are mostly the same as the JVM’s; there’s no need for cross-compilation, but in order to execute a Python application, the system needs to have a Python interpreter installed.

Similar to the “write once, run anywhere” slogan, other programming languages adopted the “write once, compile anywhere” philosophy, giving a computer program the ability to be compiled on all platforms without the need to modify its source code. This applies to languages such as C, Pascal, and Ada. But these languages still require platform-specific code when dealing with more-specialized features of the OS, such as when creating new threads or downloading the contents of a web page. Nim goes a step further; its standard library abstracts away the differences between OSs so you can use a lot of the features that modern OSs offer.

Unfortunately, in many cases, virtual machines and interpreters cause more problems than they solve. The number of common CPU architectures and the most popular OSs is not that large, so compiling for each of them isn’t that difficult. In contrast, the source code for applications written in interpreted languages is often distributed to the user, and they’re expected to install the correct version of the interpreter or virtual machine. This can result in a lot of problems.

One example of the difficulty associated with distributing such applications is the recent introduction of Python 3. Because it’s not backward compatible with the previous version, it has caused many issues for software written originally in Python 2. Python 3 was released in 2008, and as of this writing, there are still libraries written for Python 2 that don’t work with the Python 3 interpreter.[2] This wouldn’t be a problem with a compiled language because the binaries would still continue to work.

See the Python 3 Readiness page for a list of Python 3–ready packages: http://py3readiness.org/.

The lightweight nature of Nim should make it particularly appealing, especially in contrast to some of the languages mentioned in this section.

There are many different styles that software can be written in. A programming paradigm is a fundamental style of writing software, and each programming language supports a different set of paradigms. You’re probably already familiar with one or more of them, and at the very least you know what object-oriented programming (OOP) is because it’s taught as part of many computer science courses.

Nim is a multi-paradigm programming language. Unlike some popular programming languages, Nim doesn’t focus on the OOP paradigm. It’s mainly a procedural programming language, with varying support for OOP, functional, declarative, concurrent, and other programming styles.

That’s not to say that OOP isn’t well supported. OOP as a programming style is simply not forced on you. Nim supports common OOP features, including inheritance, polymorphism, and dynamic dispatch.

To give you a better idea of what Nim’s primary paradigm looks like, let’s look at the one big difference between the OOP paradigm and the procedural paradigm. In the OOP paradigm, methods and attributes are bound to objects, and the methods operate on their own data structure. In the procedural paradigm, procedures are standalone entities that operate on data structures. This may be hard for you to visualize, so let’s look at some code examples to illustrate it.

In this subsection I mention methods and procedures. These are simply different names for subroutines or functions. Method is the term used in the context of OOP, procedure is used in procedural programming, and function is used in functional programming.

The following code listings show the same application. The first is written in Python using the OOP style. The second is written in Nim using the procedural style.

class Dog:

def bark(self): 1

print("Woof!")

dog = Dog()

dog.bark() 2

type

Dog = object

proc bark(self: Dog) = 1

echo("Woof!")

let dog = Dog()

dog.bark() 2

In the Python code, the bark method is placed under the class definition. In the Nim code, the bark method (called a procedure in Nim) isn’t bound to the Dog type in the same way as it is in the Python code; it’s independent of the definition of the Dog type. Instead, its first argument specifies the type it’s associated with.

You could also implement something similar in Python, but it wouldn’t allow you to call the bark method in the same manner. You’d be forced to call it like so: bark(dog), explicitly passing the dog variable to the method as its first argument. The reason this is not the case with Nim is because Nim rewrites dog.bark() to bark(dog), making it possible for you to call methods using the traditional OOP style without having to explicitly bind them to a class.

This ability, which is referred to as Uniform Function Call Syntax (UFCS), has multiple advantages. It allows you to create new procedures on existing objects externally and allows procedure calls to be chained.

Defining classes and methods in Nim in a manner similar to Python is also possible. Metaprogramming can be used to do this, and the community has already created numerous libraries that emulate the syntax. See, for example, the Nim OOP macro: https://nim-by-example.github.io/oop_macro/.

Another paradigm that Nim supports is the functional programming (FP) paradigm. FP is not as popular as OOP, though in recent years it has seen a surge in popularity. FP is a style of programming that primarily avoids the changing of state and the use of mutable data. It uses certain features such as first-class functions, anonymous functions, and closures, all of which Nim supports.

Let’s look at an example to see the differences between programming in a procedural style and a functional one. The following code listings show code that separates people’s full names into first and last names. Listing 1.7 shows this done in a functional style and listing 1.8 in a procedural style.

import sequtils, future, strutils 1 let list = @["Dominik Picheta", "Andreas Rumpf", "Desmond Hume"] 2 list.map( 3 (x: string) -> (string, string) => (x.split[0], x.split[1]) 4 ).echo 5

import strutils 1 let list = @["Dominik Picheta", "Andreas Rumpf", "Desmond Hume"] 2 for name in list: echo((name.split[0], name.split[1])) 3

The functional version uses the map procedure to iterate over the list variable, which contains a list of names. The procedural version uses a for loop. Both versions split the name into a first and last name. They then display the result in a tuple. (I’m throwing a lot of new terms at you here. Don’t worry if you aren’t familiar with them; I’ll introduce you to them in chapter 2.) The output of the code listings will look similar to this:

(Field0: Dominik, Field1: Picheta) (Field0: Andreas, Field1: Rumpf) (Field0: Desmond, Field1: Hume)

Field0 and Field1 are just default field names given to tuples when a field name isn’t specified.

Nim is incredibly flexible and allows you to write software in many different styles. This was just a small taste of the most popular paradigms supported by Nim and of how they compare to Nim’s main paradigm. Nim also supports more-obscure paradigms, and support for others can be introduced easily using metaprogramming.

Throughout this chapter, I’ve been comparing Python to Nim. While Nim does take a lot of inspiration from Python, the two languages differ in one important way: Python is dynamically typed and Nim is statically typed. As a statically typed language, Nim provides a certain level of type safety that dynamically typed programming languages don’t provide.

Although Nim is statically typed, it feels very dynamic because it supports type inference and generics. You’ll learn more about these features later in the book. For now, think of it as a way to retain the high development speed that dynamically typed programming languages allow, while also providing extra type safety at compile time.

In addition to being statically typed, Nim implements an exception-tracking mechanism that is entirely opt-in. With exception tracking, you can ensure that a procedure won’t raise any exceptions, or that it will only raise exceptions from a predefined list. This prevents unexpected crashes by ensuring that you handle exceptions.

Throughout this section, I’ve compared Nim to various other programming languages. I’ve discussed efficiency, the dependencies of the resulting software, the flexibility of the language, and the language’s ability to catch errors before the software is deployed. Based on these characteristics alone, Nim is an excellent candidate for replacing some of the most popular programming languages out there, including Python, Java, C, and more.

For reference, table 1.2 lists different programming languages and shows some of the features that they do and don’t support.

|

Programming language |

Type system |

Generics |

Modules |

GC |

Syntax |

Metaprogramming |

Execution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nim | Static and strong | Yes | Yes | Yes, multiple and optional[a] | Python-like | Yes | Compiled binary |

| C | Static and weak | No | No | No | C | Very limited[b] | Compiled binary |

| C++ | Static and weak | Yes | No | No | C-like | Limited[c] | Compiled binary |

| D | Static and strong | Yes | Yes | Yes, optional | C-like | Yes | Compiled binary |

| Go | Static and strong | No | Yes | Yes | C-like | No | Compiled binary |

| Rust | Static and strong | Yes | Yes | No | C-like | Limited[d] | Compiled binary |

| Java | Static and strong | Yes | Yes | Yes, multiple[e] | C-like | No | Executed via the JVM |

| Python | Dynamic and strong | N/A | Yes | Yes | Python | Yes[f] | Executed via the Python interpreter |

| Lua | Dynamic and weak | N/A | Yes | Yes | Modula-like[g] | Yes via Metalua | Executed via the Lua interpreter or Lua JIT compiler |

Nim supports ref counting, a custom GC, and Boehm. Nim also allows the GC to be switched off altogether.

Some very limited metaprogramming can be achieved via C’s preprocessor.

C++ only offers metaprogramming through templates, limited CTFE (compile-time function execution), and no AST macros.

Rust has some support for declarative macros through its macro_rules! directive, but no built-in procedural macros that allow you to transform the AST except for compiler plugins, and no CTFE.

See the “Oracle JVM Garbage Collectors Available From JDK 1.7.0_04 And After” article on Fasterj: www.fasterj.com/articles/oraclecollectors1.shtml.

You can modify the behavior of functions, including manipulating their AST, using the ast module, but only at runtime.

Lua uses do and end keywords to delimit scope.

Nothing in this world is perfect, and programming languages are no exception. There’s no programming language that can solve every problem in the most reliable and rapid manner. Each programming language has its own strengths and weaknesses, and Nim is no exception.

So far, I’ve been focusing on Nim’s strengths. Nim has many more fine aspects that I haven’t yet mentioned, and you’ll discover them throughout this book. But it would be unfair to only talk about Nim’s strengths. Nim is still a young programming language, so of course it can still improve.

All programming languages go through a period of immaturity. Some of Nim’s newer and more-advanced features are still unstable. Using them can result in buggy behavior in the compiler, such as crashes, though crashes don’t happen very often. Importantly, Nim’s unstable features are opt-in, which means that you can’t accidentally use them.

Nim has a package manager called Nimble. Where other programming languages may have thousands of packages available, Nim only has about 500. This means that you may need to write libraries for certain tasks yourself. This situation is, of course, improving, with new packages being created by the Nim community every day. In chapter 5, I’ll show you how to create your own Nimble packages.

Nim has a small number of users compared to the mainstream programming languages. The result is that few Nim jobs exist. Finding a company that uses Nim in production is rare, but when it does happen, the demand for good Nim programmers can make the salaries quite high.

On the other hand, one of the most unique things about Nim is that its development is exceptionally open. Andreas Rumpf (Nim’s creator) and many other Nim developers (including me) openly discuss Nim’s future development plans on GitHub and on IRC. Anyone is free to challenge these plans and, because the community is still quite small, it’s easy to do so. IRC is also a great place for newcomers to ask questions about Nim and to meet fellow Nim programmers.

Take a look at appendix A for details on how to connect to Nim’s IRC channel.

These problems are temporary. Nim has a bright future ahead of it, and you can help shape it. This book teaches you how.

This chapter covers

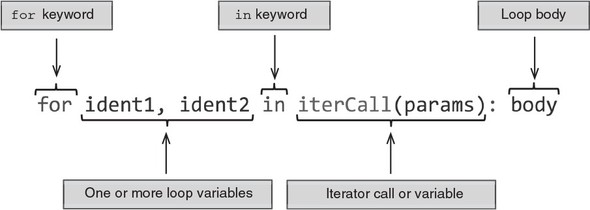

In this chapter, you’ll learn about Nim’s syntax, procedures, for loops, and other basic aspects of the language. Throughout this chapter, we’ll cover a lot of information to give you a broad taste of the language.

Before you begin, make sure you have Nim installed and that it works on your computer. You’ll also need a text editor to edit Nim code. Take a look at appendix B for instructions on how to install Nim and other related tools.

The syntax of a programming language is a set of rules that govern the way programs are written in that language. You’ve already had a small taste of Nim’s syntax in the previous chapter.

Most languages share many similarities in terms of syntax. This is especially true for the C family of languages, which happens to also be the most popular—so much so that four of the most popular programming languages are syntactically heavily inspired by C.[1] Nim aims to be highly readable, so it often uses keywords instead of punctuation. Because of this, the syntax of Nim differs significantly from the C language family; instead, much of it is inspired by Python and Pascal.

According to the TIOBE Index for December 2016, www.tiobe.com/index.php/content/paperinfo/tpci/index.html.

In this section, I’ll teach you the basics of Nim’s syntax. Learning the syntax is a very important first step, as it teaches you the specific ways in which Nim code should be written.

Most programming languages have the notion of a keyword, and Nim is no exception. A keyword is a word with a special meaning associated with it when it’s used in a specific context. Because of this, you may not use keywords as identifiers in your source code.

You can get around this limitation by using stropping. See section 1.2 to learn more.

As of version 0.12.0, Nim has 70 keywords. This may sound like a lot, but you must remember that you won’t be using most of them. Some of them don’t yet have a meaning and are reserved for future versions of the language; others have minor use cases.

The most commonly used keywords allow you to do the following:

You’ll learn exactly what these keywords mean and how to use them in the next sections of this chapter. For a full list of keywords, consult the Nim manual, available at http://nim-lang.org/docs/manual.html#lexical-analysis-identifiers-keywords.

Many programmers indent their code to make the program’s structure more apparent. In most programming languages, this isn’t a requirement and serves only as an aid to human readers of the code. In those languages, keywords and punctuation are often used to delimit code blocks. In Nim, just like in Python, the indentation itself is used.

Let’s look at a simple example to demonstrate the difference. The following three code samples written in C, Ruby, and Nim all do the same thing. But note the different ways in which code blocks are delimited.

if (42 >= 0) {

printf("42 is greater than 0");

}

if 42 >= 0 puts "42 is greater than 0" end

if 42 >= 0: echo "42 is greater than 0"

As you can see, C uses curly brackets to delimit a block of code, Ruby uses the keyword end, and Nim uses indentation. Nim also uses the colon character on the line that precedes the start of the indentation. This is required for the if statement and for many others. But as you continue learning about Nim, you’ll see that the colon isn’t required for all statements that start an indented code block.

Note also the use of the semicolon in listing 2.1. This is required at the end of each line in some programming languages (mostly the C family). It tells the compiler where a line of code ends. This means that a single statement can span multiple lines, or multiple statements can be on the same line. In C, you’d achieve both like this:

printf("The output is: %d",

0);

printf("Hello"); printf("World");

In Nim, the semicolon is optional and can be used to write two statements on a single line. Spanning a single statement over multiple lines is a bit more complex—you can only split up a statement after punctuation, and the next line must be indented. Here’s an example:

echo("Output: ", 1

5)

echo(5 + 1

5)

echo(5 2

+ 5)

echo(5 +

5) 3

Because indentation is important in Nim, you need to be consistent in its style. The convention states that all Nim code should be indented by two spaces. The Nim compiler currently disallows tabs because the inevitable mixing of spaces and tabs can have detrimental effects, especially in a whitespace-significant programming language.

Comments in code are important because they allow you to add additional meaning to pieces of code. Comments in Nim are written using the hash character (#). Anything following it will be a comment until the start of a new line. A multiline comment can be created with #[ and ]#, and code can also be disabled by using when false:. Here’s an example:

# Single-line comment

#[

Multiline comment

]#

when false:

echo("Commented-out code")

The first of the two types of multiline comment can be used to comment out both text and code, whereas the latter should only be used to comment out code. The compiler will still parse the code and ensure that it’s syntactically valid, but it won’t be included in the resulting program. This is because the compiler checks when statements at compile time.

Now that you have a basic understanding of Nim’s syntax, you have a good foundation for learning some of the semantics of Nim. In this section, you’ll learn some of the essentials that every Nim programmer uses on a daily basis. You’ll learn about the most commonly used static types, the details of mutable and immutable variables, and how to separate commonly used code into standalone units by defining procedures.

Nim is a statically typed programming language. This means that each identifier in Nim has a type associated with it at compile time. When you compile your Nim program, the compiler ensures that your code is type safe. If it isn’t, compilation terminates and the compiler outputs an error. This is in contrast to dynamically typed programming languages, such as Ruby, that will only ensure that your code is type safe at runtime.

By convention, type names start with an uppercase letter. Built-in types don’t follow this convention, so it’s easy for you to distinguish between built-in types and user-defined types by checking the first letter of the name. Nim supports many built-in types, including ones for dealing with the C foreign function interface (FFI). I don’t cover all of them here, but they will be covered later in this book.

The foreign function interface (FFI) is what allows you to use libraries written in other programming languages. Nim includes types that are native to C and C++, allowing libraries written in those languages to be used.

Most of the built-in types are defined in the system module, which is imported automatically into your source code. When referring to these types in your code, you can qualify them with the module name (for example, system.int), but doing so isn’t necessary. See table 2.1 for a list of the basic types defined in the system module.

Modules are imported using the import keyword. You’ll learn more about modules later in this book.

|

Type |

Description and uses |

|---|---|

| int | The integer type is the type used for whole numbers; for example, 52. |

| float | The float is the type used for numbers with a decimal point; for example, 2.5. |

| string | The string type is used to store multiple characters. String literals are created by placing multiple characters inside double quotes: "Nim is awesome". |

| bool | The Boolean type stores one of two values, either true or false. |

| char | The character type stores a single ASCII character. Character literals are created by placing a character inside single quotes; for example, 'A'. |

The integer type represents numerical data without a fractional component; that is, whole numbers. The amount of data this type can store is finite, so there are multiple versions of it in Nim, each suited to different size requirements. The main integer type in Nim is int. It’s the integer type you should be using most in your Nim programs. See table 2.2 for a list of integer types.

An integer literal in Nim can be represented using decimal, octal, hexadecimal, or binary notation.

let decimal = 42 let hex = 0x42 let octal = 0o42 let binary = 0b101010

Listing 2.4 defines four integer variables and assigns a different integer literal to each of them, using the four different integer-literal formats.

You’ll note that the type isn’t specified for any of the defined variables. The Nim compiler will infer the correct type based on the integer literal that’s specified. In this case, all variables will have the type int.

The compiler determines which integer type to use by looking at the size of the integer literal. The type is int64 if the integer literal exceeds the 32-bit range; otherwise, it’s int. But what if you want to use a specific integer type for your variable? There are multiple ways to accomplish this:

let a: int16 = 42 1 let b = 42'i8 2

Explicitly using a small integer type such as int8 may result in a compile-time or, in some cases, a runtime error. Take a look at the ranges in table 2.2 to see what size of integer can fit into which integer type. You should be careful not to attempt to assign an integer that’s bigger or smaller than the type can hold.

Nim supports type suffixes for all integer types, both signed and unsigned. The format is 'iX, where X is the size of the signed integer, and 'uX, where X is the size of the unsigned integer.[2]

See the Nim manual for more on numerical constants: http://nim-lang.org/docs/manual.html#lexical--analysis-numerical-constants.

The floating-point type represents an approximation of numerical data with a fractional component. The main floating-point type in Nim is float, and its size depends on the platform.

let a = 1'f32 let b = 1.0e19

The compiler will implicitly use the float type for floating-point literals.

You can specify the type of the literal using a type suffix. There are two type suffixes for floats that correspond to the available floating-point types: 'f32 for float32 and 'f64 for float64.

Exponents can also be specified after the number. Variable b in the preceding listing will be equal to 1x1019 (1 times 10 to the power of 19).

The Boolean type represents one of two values: usually a true or false value. In Nim, the Boolean type is called bool.

let a = false let b = true

The false and true values of a Boolean must begin with a lowercase letter.

The character type represents a single character. In Nim, the character type is called char. It can’t represent UTF-8 characters but instead encodes ASCII characters. Because of this, char is really just a number.

A character literal in Nim is a single character enclosed in quotes. The character may also be an escape sequence introduced by a backward slash (\). Some common character-escape sequences are listed in table 2.3.

|

Result |

|

|---|---|

| \r, \c | Carriage return |

| \l | Line feed |

| \t | Tab |

| \\ | Backslash |

| \' | Apostrophe |

| \" | Quotation mark |

let a = 'A' let b = '\109' let c = '\x79'

The unicode module contains a Rune type that can hold any unicode character.

The newline escape sequence \n isn’t allowed in a character literal as it may be composed of multiple characters on some platforms. On Windows, it’s \r\l (carriage return followed by line feed), whereas on Linux it’s just \l (line feed). Specify the character you want explicitly, such as '\r' to get a carriage return, or use a string.

The string type represents a sequence of characters. In Nim, the string type is called string. It’s a list of characters terminated by '\0'.

The string type also stores its length. A string in Nim can store UTF-8 text, but the unicode module should be used for processing it, such as when you want to change the case of UTF-8 characters in a string.

There are multiple ways to define string literals, such as this:

let text = "The book title is \"Nim in Action\""

When defining string literals this way, certain characters must be escaped in them. For instance, the double-quote character (") should be escaped as \" and the backward-slash character (\) as \\. String literals support the same character-escape sequences that character literals support; see table 2.3 for a good list of the common ones. One major additional escape sequence that string literals support is \n, which produces a newline; the actual characters that are produced depend on the platform.

The need to escape some characters makes some things tedious to write. One example is Windows file paths:

let filepath = "C:\\Program Files\\Nim"

Nim supports raw string literals that don’t require escape sequences. Apart from the double-quote character ("), which still needs to be escaped as "", any character placed in a raw string literal will be stored verbatim in the string. A raw string literal is a string literal preceded by an r:

let filepath = r"C:\Program Files\Nim"

It’s also possible to specify multiline strings using triple-quoted string literals:

let multiLine = """foo bar baz """ echo multiLine

The output for the preceding code looks like this:

foo bar baz

Triple-quoted string literals are enclosed between three double-quote characters, and these string literals may contain any characters, including the double-quote character, without any escape sequences. The only exception is that your string literal may not repeat the double-quote character three times. There’s no way to include three double-quote characters in a triple-quoted string literal.

The indentation added to the string literal defining the multiLine variable causes leading whitespace to appear at the start of each line. This can be easily fixed by the use of the unindent procedure. It lives in the strutils module, so you must first import it:

import strutils let multiLine = """foo bar baz """ echo multiLine.unindent

This will produce the following output:

foo bar baz

Storage in Nim is defined using three different keywords. In addition to the let keyword, which you saw in the previous section, you can also define storage using const and var.

let number = 10

By using the let keyword, you’ll be creating what’s known as an immutable variable—a variable that can only be assigned to once. In this case, a new immutable variable named number is created, and the identifier number is bound to the value 10. If you attempt to assign a different value to this variable, your program won’t compile, as in the following numbers.nim example:

let number = 10 number = 4000

The preceding code will produce the following output when compiled:

numbers.nim(2, 1) Error: 'number' cannot be assigned to

Nim also supports mutable variables using the keyword var. Use these if you intend on changing the value of a variable. The previous example can be fixed by replacing the let keyword with the var keyword:

var number = 10 number = 4000

In both examples, the compiler will infer the type of the number variable based on the value assigned to it. In this case, number will be an int. You can specify the type explicitly by writing the type after the variable name and separating it with a colon character (:). By doing this, you can omit the assignment, which is useful when you don’t want to assign a value to the variable when defining it.

var number: int 1

Immutable variables must be assigned a value when they’re defined because their values can’t change. This includes both const and let defined storage.

A variable’s initial value will always be binary zero. This will manifest in different ways, depending on the type. For example, by default, integers will be 0 and strings will be nil. nil is a special value that signifies the lack of a value for any reference type. You’ll learn more about this later.

The type of a variable can’t change. For example, assigning a string to an int variable will result in a compile-time error, as in this typeMismatch.nim example:

var number = 10 number = "error"

Here’s the error output:

typeMismatch.nim(2, 10) Error: type mismatch: got (string) but expected 'int'

Nim also supports constants. Because the value of a constant is also immutable, constants are similar to immutable variables defined using let. But a Nim constant differs in one important way: its value must be computable at compile time.

proc fillString(): string =

result = ""

echo("Generating string")

for i in 0 .. 4:

result.add($i) 1

const count = fillString()

Don’t worry about not understanding the details of procedures in Nim yet. You’ll be introduced to them shortly.

The fillString procedure in listing 2.8 will generate a new string, equal to "01234". The constant count will then be assigned this string.

I added the echo at the top of fillString’s body, in order to show you that it’s executed at compile time. Try compiling the example using Aporia or in a terminal by executing nim c file.nim. You’ll see "Generating string" amongst the output. Running the binary will never display that message because the result of the fillString procedure is embedded in it.

In order to generate the value of the constant, the fillString procedure must be executed at compile time by the Nim compiler. You have to be aware, though, that not all code can be executed at compile time. For example, if a compile-time procedure uses the FFI, you’ll find that the compiler will output an error similar to “Error: cannot ‘importc’ variable at compile time.”

The main benefit of using constants is efficiency. The compiler can compute a value for you at compile time, saving time that would be otherwise spent during runtime. The obvious downside is longer compilation time, but it could also produce a larger executable size. As with many things, you must find the right balance for your use case. Nim gives you the tools, but you must use them responsibly.[3]

With great power comes great responsibility.

You can also specify multiple variable definitions under the same var, let, or const keyword. To do this, add a new line after the keyword and indent the identifier on the next line:

var text = "hello" number: int = 10 isTrue = false

The identifier of a variable is its name. It can contain any characters, as long as the name doesn’t begin with a number and doesn’t contain two consecutive underscores. This applies to all identifiers, including procedure and type names. Identifiers can even make use of Unicode characters:

var 火 = "Fire" let ogień = true

Unlike in many other programming languages, identifiers in Nim are case insensitive with the exception of the first letter of the identifier. This is to help distinguish variable names, which must begin with lowercase letters, from type names, which must begin with uppercase letters.

As you may recall from section 2.1, there are identifiers in Nim that are reserved. Such identifiers are called keywords, and because they have a special meaning, they can’t be used as names for variables, types, or procedures.

In order to get around this limitation, you can either pick a different name or explicitly mark the identifier using backticks (`). The latter approach is called stropping, and here’s how it can be used:

var `var` = "Hello" echo(`var`)

The var keyword is enclosed in backticks, allowing a variable with that name to be defined.

Identifiers in Nim are also style insensitive. This allows identifiers written in camelCase to be equivalent to identifiers written in snake_case. The way this is accomplished is by ignoring the underscore character in identifiers, so fooBar is equivalent to foo_bar. You’re free to write identifiers in whichever style you prefer, even when they’re defined in a different style. But you’re encouraged to follow Nim’s style conventions, which specify that variables should use camelCase and types should use PascalCase. For more information about Nim’s conventions, take a look at the “Style Guide for Nim Code” on GitHub: https://github.com/nim-lang/Nim/wiki/Style-Guide-for-Nim-Code.

Procedures allow you to separate your program into different units of code. These units generally perform a single task, after being given some input data, usually in the form of one or more parameters.

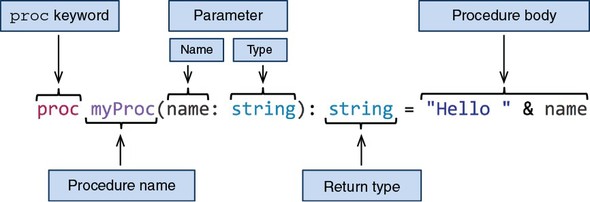

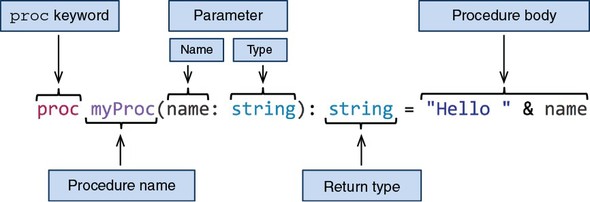

In this section, we’ll explore procedures in Nim. In other programming languages a procedure may be known as a function, method, or subroutine. Each programming language attaches different meanings to these terms, and Nim is no exception. A procedure in Nim can be defined using the proc keyword, followed by the procedure’s name, parameters, optional return type, =, and the procedure body. Figure 2.1 shows the syntax of a Nim procedure definition.

The procedure in figure 2.1 is named myProc and it takes one parameter (name) of type string, and returns a value of type string. The procedure body implicitly returns a concatenation of the string literal "Hello " and the parameter name.

You can call a procedure by writing the name of the procedure followed by parentheses: myProc("Dominik"). Any parameters can be specified inside the parentheses. Calling the myProc procedure with a "Dominik" parameter, as in the preceding example, will cause the string "Hello Dominik" to be returned.

Whenever procedures with a return value are called, their results must be used in some way.

proc myProc(name: string): string = "Hello " & name

myProc("Dominik")

Compiling this example will result in an error: “file.nim(2, 7) Error: value of type ‘string’ has to be discarded.” This error occurs as a result of the value returned by the myProc procedure being implicitly discarded. In most cases, ignoring the result of a procedure is a bug in your code, because the result could describe an error that occurred or give you a piece of vital information. You’ll likely want to do something with the result, such as store it in a variable or pass it to another procedure via a call. In cases where you really don’t want to do anything with the result of a procedure, you can use the discard keyword to tell the compiler to be quiet:

proc myProc(name: string): string = "Hello " & name

discard myProc("Dominik")

The discard keyword simply lets the compiler know that you’re happy to ignore the value that the procedure returns.

Procedures must be defined above the call site. For example, the following code will fail to compile:

myProc()

proc myProc() = echo("Hello World")

For procedures that have a circular dependency, a forward declaration must be used:

proc bar(): int 1 proc foo(): float = bar().float proc bar(): int = foo().int

A future version of Nim will likely remove the need for forward declarations and allow procedures to be defined in any order.

When a procedure returns no values, the return type can be omitted. In that case, the procedure is said to return void. The following two examples return no value:

proc noReturn() = echo("Hello")