Chapter 6. Service Workers: An Introduction

Service workers have become progressively popular over the last couple of years. Last year, the talk was all about what service workers are, now it’s about how we can use them. How do they help solve some of the common performance and security concerns with the modern browser? The next few chapters will discuss various applications of service workers, in an effort to bring further performance and security gains to the browser. Before diving into different use cases, let’s briefly go over what service workers are and the architecture behind how they work so that we can better understand why they help bridge the gap between security and performance.

What Are Service Workers?

Textbook definition of a service worker: a script that is run by your browser in the background, apart from a webpage.1 It’s essentially a shared worker that runs in its own global context and acts as an event-driven background service while handling incoming network requests.

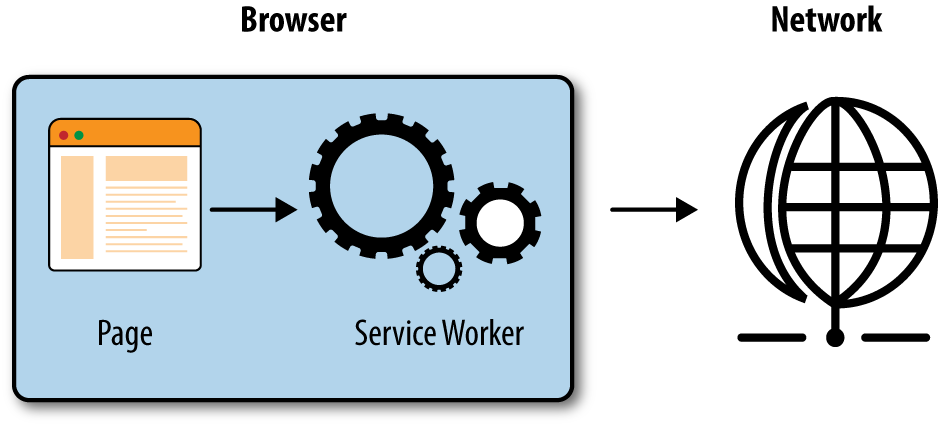

As displayed in Figure 6-1, a service worker lives in the browser while sitting in between the page/browser and the network, so that we can intercept incoming resource requests and perform actions based on predefined criteria. Because of the infrastructure, service workers address the need to handle offline experiences or experiences with terrible network connectivity.

Figure 6-1. Service worker architecture

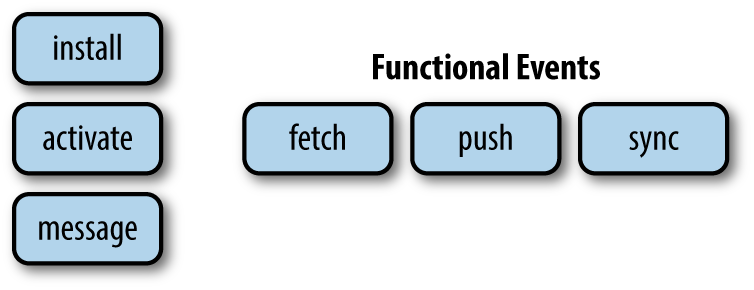

To get service workers up and running, certain event listeners need to be implemented, as displayed in Figure 6-2.

Figure 6-2. Events

These event listeners include the install and activate events, which allow developers to set up any necessary infrastructure, such as offline caches, prior to resource handling. Once a service worker has been installed and activated on the first page request, it can then begin intercepting any incoming resource requests on subsequent page requests using functional events. The available events are fetch, sync, and push; we will focus on leveraging the fetch event in the next few chapters. The fetch event hijacks incoming network requests and allows the browser to fetch content from different sources based on the request or even block content if desired.

Gotchas!

As with any new technology, there are of course several caveats.2 Knowing these will help gain insight as to why service workers can provide both a secure and optimal experience for the end user.

-

Service workers must be served over HTTPS. Given the ability to hijack incoming requests, it’s important that we leverage this functionality over secure traffic to avoid man-in-the-middle attacks.

-

Service workers are not yet supported in all browsers.

-

The browser can terminate a service worker at any time. If the service worker is not being used or has been potentially tampered with, the browser has the ability to put it into sleep mode to avoid impacting website functionality from both a security and performance perspective.

-

The service worker has no DOM access, which suggests there is less risk of code or objects being injected by an attacker.

-

Fetch events are limited to a certain scope: the location where the service worker is installed.

-

Fetch events do not get triggered for

<iframe>, other service workers, or requests triggered from within service workers (helps to prevent infinite loops of event handling).

In the next few chapters, we will discuss these caveats in relation to specific service worker implementations.

1 “Using Service Workers,” Mozilla Development Network, accessed October 13, 2016, https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Service_Worker_API/Using_Service_Workers

2 “Service Workers: An Introduction,” Matt Gaunt, accessed October 13, 2016, http://www.html5rocks.com/en/tutorials/service-worker/introduction