Chapter 8. Putting Evolutionary Architecture into Practice

Finally, we look at the steps required to implement the ideas around evolutionary architecture. This includes both technical and business concerns, including organization and team impacts. We also suggest where to start and how to sell these ideas to your business.

Organizational Factors

The impact of software architecture has a surprisingly wide breadth on a variety of factors not normally associated with software, including team impacts, budgeting, and a host of others.

Teams structured around domains rather than technical capabilities have several advantages when it comes to evolutionary architecture and exhibit some common characteristics.

Cross-Functional Teams

Domain-centric teams tend to be cross-functional, meaning every project role is covered by someone on the project. The goal of a domain-centric team is to eliminate operational friction. In other words, the team has all the roles needed to design, implement, and deploy their service, including traditionally separate roles like operations. But these roles must change to accommodate this new structure, which includes the following roles:

- Business Analysts

-

Must coordinate the goals of this service with other services, including other service teams.

- Architecture

-

Design architecture to eliminate inappropriate coupling that complicates incremental change. Notice this doesn’t require an exotic architecture like microservices. A well-designed modular monolithic application may display the same ability to accommodate incremental change (although architects must design the application explicitly to support this level of change).

- Testing

-

Testers must become accustomed to the challenges of integration testing across domains, such as building integration environments, creating and maintaining contracts, and so on.

- Operations

-

Slicing up services and deploying them separately (often alongside existing services and deployed continuously) is a daunting challenge for many organizations with traditional IT structures. Naive old school architects believe that component and operational modularity are the same thing, but this is often not the case in the real world. Automating DevOps tasks like machine provisioning and deployment are critical to success.

- Data

-

Database administrators must deal with new granularity, transaction, and system of record issues.

One goal of cross-functional teams is to eliminate coordination friction. On traditional siloed teams, developers often must wait on a DBA to make changes or wait for someone in operations to provide resources. Making all the roles local eliminates the incidental friction of coordination across silos.

While it would be luxurious to have every role filled by qualified engineers on every project, most companies aren’t that lucky. Key skill areas are always constrained by external forces like market demand. So, many companies aspire to create cross-functional teams but cannot because of resources. In those cases, constrained resources may be shared across projects. For example, rather than have one operations engineer per service, perhaps they rotate across several different teams.

By modeling architecture and teams around the domain, the common unit of change is now handled within the same team, reducing artificial friction. A domain-centric architecture may still use layered architecture for its other benefits, such as separation of concerns. For example, the implementation of a particular microservice might depend on a framework that implements the layered architecture, allowing that team to easily swap out a technical layer. Microservices encapsulate the technical architecture inside the domain, inverting the traditional relationship.

Organized Around Business Capabilities

Organizing teams around domains implicitly means organizing them around business capabilities. Many organizations expect their technical architecture to represent its own complex abstraction, loosely related to business behavior because architect’s traditional emphasis has been around purely technical architecture, that is typically segregated by functionality. For example, a layered architecture is designed to make swapping technical architecture layers easier, not make working on a domain entity like Customer easier. Most of this emphasis was driven by external factors. For example, many architectural styles of the past decade focused heavily on maximizing shared resources because of expense.

Architects have gradually detangled themselves from commercial restrictions via the embrace of open source in all corners of most organizations. Shared resource architecture has inherent problems around inadvertent interference between parts. Now that developers have the option of creating custom-made environments and functionality, it is easier for them to shift emphasis away from technical architectures and focus more on domain-centric ones to better match the common unit of change in most software projects.

Tip

Organize teams around business capabilities, not job functions.

Product over Project

One mechanism many companies use to shift their team emphasis is to model their work around products rather than projects. Software projects have a common workflow in most organizations. A problem is identified, a development team is formed, and they work on the problem until “completion,” at which time they turn the software over to operations for care, feeding, and maintenance for the rest of its life. Then the project team moves on to the next problem.

This causes a slew of common problems. First, because the team has moved on to other concerns, bug fixes and other maintenance work is often difficult to manage. Second, because the developers are isolated from the operational aspects of their code, they care less about things like quality. In general, the more layers of indirection between a developer and their running code, the less connection they have to that code. This sometimes leads to an “us versus them” mentality between operational silos, which isn’t surprising, as many organizations have incentivized workers to exist in conflict.

By thinking of software as a product, it shifts the company’s perspective in three ways. First, products live forever, unlike the lifespan of projects. Cross-functional teams (frequently based on the Inverse Conway Maneuver) stay associated with their product. Second, each product has an owner who advocates for its use within the ecosystem and manages things like requirements. Third, because the team is cross-functional, each role needed by the product is represented: business analyst, developers, QA, DBA, operations, and any other required roles.

The real goal of shifting from a project to a product mentality concerns long-term company buy-in. Product teams take ownership responsibility for the long-term quality of their product. Thus, developers take ownership of quality metrics and pay more attention to defects. This perspective also helps provide a long-term vision to the team.

Having small, cross-functional teams also takes andvantage of human nature. Amazon’s “two-pizza team” mimics small group primate behavior. Most sports teams have around 10 players, and anthropologists believe that preverbal hunting parties were also around this size. Building highly responsible teams leverages innate social behavior, making team members more responsible. For example, suppose a developer in a traditional project structure wrote some code two years ago that blew up in the middle of the night, forcing someone in operations to respond to a pager in the night and fix it. The next morning, our careless developer may not even realize they accidentally caused a panic in the middle of the night. On a cross-functional team, if the developer wrote code that blew up in the night and someone from his team had to respond to it, the next morning, our hapless developer has to look across the table at the sad, tired eyes of their team member they inadvertently affected. It should make our errant developer want to be a better teammate.

Creating cross-functional teams prevents finger pointing across silos and engenders a feeling of ownership in the team, encouraging team members to do their best work.

Dealing with External Change

We advocate building components that are highly decoupled in terms of technical architecture, team structure, and so on to allow maximum opportunities for evolution, in the real world, components must interact with one another to share information that collaboratively solves domain problems. So how can we build components that can freely evolve yet make sure we can maintain the integrity of our integration points?

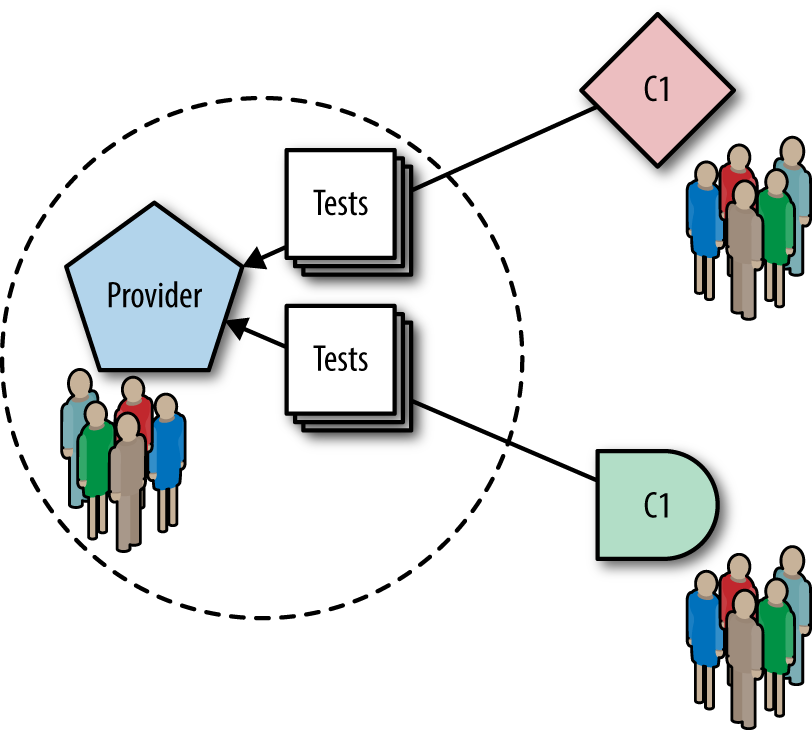

For any dimension in our architecture that requires protection from the side effects of evolution, we create fitness functions. A common practice in microservices architectures is the use of consumer-driven contracts, which are atomic integration architecture fitness functions. Consider the illustration shown in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. Consumer-driven contracts use tests to establish contracts between a provider and consumer(s)

In Figure 8-1, the provider team is supplying information (typically data in a lightweight format) to each of the consumers, C1 and C2. In consumer-driven contracts, the consumers of information put together a suite of tests that encapsulate what they need from the provider and hand off those tests to the provider, who promises to keep those tests passing at all times. Because the tests cover the information needed by the consumer, the provider can evolve in any way that doesn’t break these fitness functions. In the scenario shown in Figure 8-1, the provider runs tests on behalf of all three consumers in addition to their own suite of tests. Using fitness functions like this is informally known as an engineering safety net. Maintaining integration protocol consistency shouldn’t be done manually when it is easy to build fitness functions to handle this chore.

One implicit assumption included in the incremental change aspect of evolutionary architecture is a certain level of engineering maturity amongst the development teams. For example, if a team is using consumer-driven contracts but they also have broken builds for days at time, they can’t be sure their integration points are still valid. Using engineering practice to police practices via fitness functions relieves lots of manual pain from developers but requires a certain level of maturity to be successful.

Connections Between Team Members

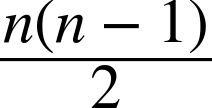

Many companies have found anecdotally that large development teams don’t work well, and J. Richard Hackman, a famous expert on team dynamics, offers an explanation as to why. It’s not the number of people but the number of connections they must maintain. He uses the formula shown in Equation 8-1 to determine how many connections exist between people, where n is the number of people.

Equation 8-1. Number of connections between people

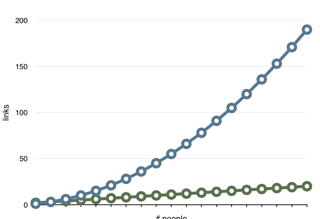

In Equation 8-1, as the number of people grows, the number of connections grows rapidly, as shown in Figure 8-2.

Figure 8-2. As the number of people grows, the connections grow rapidly.

In Figure 8-2, when the number of people on a team reaches 20, they must manage 190 links; when it reaches 50 team members, the number of links is a daunting 1225. Thus, the motivation to create small teams revolves around the desire to cut down on communication links. And these small teams should be cross-functional to eliminate artificial friction imposed by coordinating across silos.

Each team shouldn’t have to know what other teams are doing, unless integration points exist between the teams. Even then, fitness functions should be used to ensure integrity of integration points.

Team Coupling Characteristics

The way firms organize and govern their own structures significantly influences the way that software is built and architected. In this section, we explore the different organizational and team aspects that make building evolutionary architectures easier or harder. Most architects don’t think about how team structure affects the coupling characteristics of the architecture, but it has a huge impact.

Culture

Culture, (n.): The ideas, customs, and social behavior of a particular people or society.

Oxford Dictionary

Architects should care about how engineers build their system and watch out for the behaviors their organization rewards. The activities and decision-making processes architects use to choose tools and create designs can have a big impact on how well software endures evolution. Well-functioning architects take on leadership roles, creating the technical culture and designing approaches for how developers build systems. They teach and encourage in individual engineers the skills necessary to build evolutionary architecture.

An architect can seek to understand a team’s engineering culture by asking questions like:

-

Does everyone on the team know what fitness functions are and consider the impact of new tool or product choices on the ability to evolve new fitness functions?

-

Are teams measuring how well their system meets their defined fitness functions?

-

Do engineers understand cohesion and coupling?

-

Are there conversations about what domain and technical concepts belong together?

-

Do teams choose solutions not based on what technology they want to learn, but based on its ability to make changes?

-

How are teams responding to business changes? Do they struggle to incorporate small changes, or are they spending too much time on small business change?

Adjusting the behavior of the team often involves adjusting the process around the team, as people respond to what is asked of them to do.

Tell me how you measure me, and I will tell you how I will behave.

Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt (The Haystack Syndrome)

If a team is unaccustomed to change, an architect can introduce practices that start making that a priority. For example, when a team considers a new library or framework, the architect can ask the team to explicitly evaluate, through a short experiment, how much extra coupling the new library or framework will add. Will engineers be able to easily write and test code outside of the given library or framework, or will the new library and framework require additional runtime setup that may slow down the development loop?

In addition to the selection of new libraries or frameworks, code reviews are a natural place to consider how well newly changed code supports future changes. If there is another place in the system that will suddenly use another external integration point, and that integration point will change, how many places would need to be updated? Of course, developers must watch out for overengineering, prematurely adding additional complexity or abstractions for change. The Refactoring book contains relevant advice:

Three strikes and you refactor

The first time you do something, you just do it. The second time you do something similar, you wince at the duplication, but you do the duplicate thing anyway. The third time you do something similar, you refactor.

Many teams are driven and rewarded most often for delivering new functionality, with code quality and the evolvable aspect considered only if teams make it a priority. An architect that cares about evolutionary architecture needs to watch out for team actions that prioritize design decisions that help with evolvability or to finds ways to encourage it.

Culture of Experimentation

Successful evolution demands experimentation, but some companies fail to experiment because they are too busy delivering to plans. Successful experimentation is about running small activities on a regular basis to try out new ideas (both from a technical and product perspective) and to integrate successful experiments into existing systems.

The real measure of success is the number of experiments that can be crowded into 24 hours.

Thomas Alva Edison

Organizations can encourage experimentation in a variety of ways:

- Bringing ideas from outside

-

Many companies send their employees to conferences and encourage them to find new technologies, tools, and approaches that might solve a problem better. Other companies bring in external advice or consultants as sources of new ideas.

- Encouraging explicit improvement

-

Toyota is most famous for their culture of kaizen, or continuous improvement. Everyone is expected to continually seek constant improvements, particularly those closest to the problems and empowered to solve them.

- Spike and stabilize

-

A spike solution is an extreme programming practice where teams generate a throw-away solution to quickly learn a tough technical problem, explore an unfamiliar domain, or increase confidence in estimates. Using spike solutions increases learning speed at the cost of software quality; no one would want to put a spike solution straight into production because it would lack the necessary thought and time to make it operational. It was created for learning, not as the well engineered solution.

- Creating innovation time

-

Google is well known for their 20% time, where employees can work on any project for 20% of their time. Other companies organize Hackathons and allow teams to find new products or improvements to existing products. Atlassian holds regular 24-hour sessions called ShipIt days.

- Following set-based development

-

Set-based development focuses on exploring multiple approaches. At first glance, multiple options appear costly because of extra work, but in exploring several options simultaneously, teams end up with a better understanding of the problem at hand and discover real constraints with tooling or approach. The key to effective set-based development is to prototype several approaches in a short time-period (i.e., less than a few days) to build more concrete data and experience. A more robust solution often appears after taking into account several competing solutions.

- Connecting engineers with end-users

-

Experimentation is only successful when teams understand the impact of their work. In many firms with an experimentation mindset, teams and product people see first-hand the impact of decisions on end-customers and are encouraged to experiment to explore this impact. A/B testing is one such practice companies use with this experimentation mindset. Another practice companies implement is sending teams and engineers to observe how users interact with their software to achieve a certain task. This practice, taken from the pages of the usability community, builds empathy with end-users and engineers often return with a better understanding of user needs, and with new ideas to better fulfill them.

CFO and Budgeting

Many traditional functions of enterprise architecture, such as budgeting, must reflect changing priorities in an evolutionary architecture. In the past, budgeting was based on the ability to predict long-term trends in a software development ecosystem. However, as we’ve suggested throughout this book, the fundamental nature of dynamic equilibrium destroys predictability.

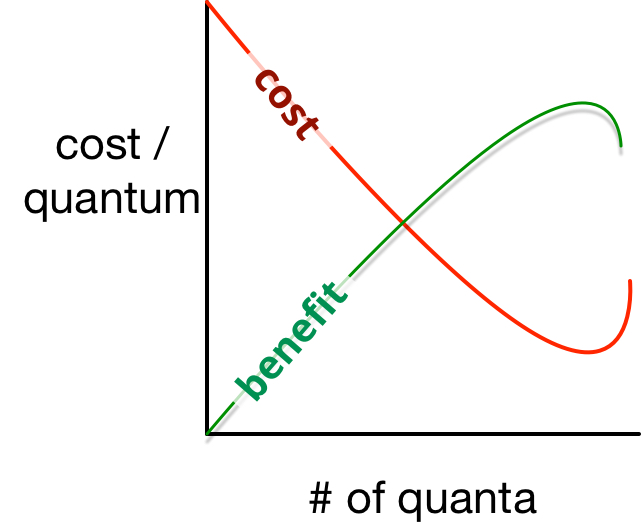

In fact, an interesting relationship exists between architectural quanta and the cost of architecture. As the number of quanta rises, the cost per quantum goes down, until architects reach a sweet spot, as illustrated in Figure 8-3.

Figure 8-3. The relationship between architectural quanta and cost

In Figure 8-3, as the number of architectural quanta rises, the cost of each diminishes because of several factors. First, because the architecture consists of smaller parts, the separation of concerns should be more discrete and defined. Second, rising numbers of physical quanta require automation of their operational aspects because, beyond a certain point, it is no longer practical for people to handle chores manually.

However, it is possible to make quanta so small that the shear numbers become more costly. For example, in a microservices architecture, it is possible to build services at the granularity of a single field on a form. At that level, the coordination cost between each small part starts dominating other factors in the architecture. Thus, at the extremes of the graph, the sheer number of quanta drives benefit per quantum down.

In an evolutionary architecture, architects strive to find the sweet spot between the proper quantum size and the corresponding costs. Every company is different. For example, a company in an aggressive market may need to move faster and therefore desire a smaller quantum size. Remember, the speed at which new generations appear is proportional to cycle time, and smaller quanta tend to have shorter cycle times. Another company may find it pragmatic to build a service-based architecture (covered in Chapter 4) with larger “portion of the application” quantum sizes because it more closely models common change.

As we face an ecosystem that defies planning, many factors determine the best match between architecture and cost. This reflects our observation that the role of architect has expanded: Architectural choices have more impact than ever.

Rather than adhere to decades-old “best practice” guides about enterprise architecture, modern architects must understand the benefits of evolvable systems along with the inherent uncertainty that goes with them.

Building Enterprise Fitness Functions

In an evolutionary architecture, the role of the enterprise architect revolves around guidance and enterprise-wide fitness functions. Microservices architectures reflect this changing model. Because each service is operationally decoupled from the others, sharing resources isn’t a consideration. Instead, architects provide guidance around the purposeful coupling points in the architecture (such as service templates) and platform choices. Enterprise architecture typically owns this shared infrastructure function and constrains platform choices to those supported consistently enterprise wide.

The other new role that evolutionary architecture creates has enterprise architects defining enterprise-wide fitness functions. Enterprise architects are typically respsonsible for enterprise-wide nonfunctional requirements, such as scalability and security. Many organizations lack the ability to automatically assess how well projects perform individually and in aggregate for these characteristics. Once projects adopt fitness functions to protect parts of their architecture, enterprise architects can utilize the same mechanism to verify that enterprise-wide characteristics remain intact.

If each project uses a deployment pipeline to apply fitness functions as part of their build, enterprise architects can insert some of their own fitness functions as well. This allows each project to verify cross-cutting concerns, such as scalability, security, and other enterprise-wide concerns, on a continual basis, discovering flaws as early as possible. Just as projects in microservices share service templates to unify parts of technical architecture, enterprise architects can use deployment pipelines to drive consistent testing across projects.

Case Study: PenultimateWidgets as a Platform

Business at PenultimateWidgets is going so well they have decided to sell part of their platform to other sellers of things like widgets. Part of the appeal of the PenultimateWidgets platform is its proven scalability, resiliency, performance, and other assets. However, their architects don’t want to sell the platform only to start hearing stories of failures because users extend it in damaging ways.

To help preserve the important characteristics of the platform, the PenultimateWidgets architects provide a deployment pipeline along with the platform with built-in fitness functions around important dimensions. To remain certified, users of the platform must preserve the existing fitness functions and (hopefully) add their own as they extend the platform.

Where Do You Start?

Many architects with existing architectures that resemble Big Balls of Mud struggle with where to start adding evolvability. While appropriate coupling and using modularity are some of the first steps you should take, sometimes there are other priorities. For example, if your data schema is hopelessly coupled, determining how DBAs can achieve modularity might be the first step. Here are some common strategies and reasons to adopt the practices around building evolutionary architectures.

Low-Hanging Fruit

If an organization needs an early win to prove the approach, architects may choose the easiest problem that highlights the evolutionary architecture approach. Generally, this will be part of the system that is already decoupled to a large degree and hopefully not on the critical path to any dependencies. Increasing modularity and decreasing coupling allows teams to demonstrate other aspects of evolutionary architecture, namely fitness functions and incremental change. Building better isolation allows more focused testing and the creation of fitness functions. Better isolation of deployable units makes building deployment pipelines easier and provides a platform for building more robust testing.

Metrics are a common adjunct to the deployment pipeline in incremental change environments. If teams use this effort as a proof-of-concept, developers should gather appropriate metrics for both before and after scenarios. Gathering concrete data is the best way to for developers to vet the approach; remember the adage that demonstration defeats discussion.

This “easiest first” approach minimizes risk at the possible expense of value, unless a team is lucky enough to have easy and high value align. This is a good strategy for companies that are skeptical and want to dip their toes in the metaphorical water of evolutionary architecture.

Highest-Value

An alternative approach to “easiest first” is “highest value first”—find the most critical part of the system and build evolutionary behavior around it first. Companies may take this approach for several reasons. First, if architects are convinced that they want to pursue an evolutionary architecture, choosing the highest value portion first indicates commitment. Second, for companies still evaluating these ideas, their architects may be curious as to how applicable these techniques are within their ecosystem. Thus, by choosing the highest value part first, they demonstrate the long-term value proposition of evolutionary architecture. Third, if architects have doubts that these ideas can work for their application, vetting the concepts via the most valuable part of the system provides actionable data as to whether they want to proceed.

Testing

Many companies lament the lack of testing their systems have. If developers find themselves in a code base with anemic or no testing, they may decide to add some critical tests before undertaking the more ambitious move to evolutionary architecture.

It is generally frowned upon for developers to undertake a project that only adds tests to a code base. Management looks upon this activity with suspicion, especially if new feature implementation is delayed. Rather, architects should combine increasing modularity with high-level functional tests. Wrapping functionality with unit tests provides better scaffolding for engineering practices such as test-driven development (TDD) but takes time to retrofit into a code base. Instead, developers should add coarse-grained functional tests around some behavior before restructuring the code, allowing you to verify that the overall system behavior hasn’t changed because of the restructuring.

Testing is a critical component to the incremental change aspect of evolutionary architecture, and fitness functions leverage tests aggressively. Thus, at least some level of testing enables these techniques, and a strong correlation exists between comprehensiveness of testing and ease of implementing an evolutionary architecture.

Infrastructure

New capabilities come slow to some companies, and the operations group is a common victim of lack of innovation. For companies that have a dysfunctional infrastructure, getting those problems solved may be a precursor to building an evolutionary architecture. Infrastructure issues come in many forms. For example, some companies outsource all their operational responsibilities to another company and thus don’t control that critical piece of their ecosystem; the difficultly of DevOps rises orders of magnitude when saddled with the overhead of cross-company coordination.

Another common infrastructure dysfunction is an impenetrable firewall between development and operations, where developers have no insight into how code eventually runs. This structure is common in companies rife with politics across divisions, where each silo acts autonomously.

Lastly, architects and developers in some organizations have ignored good practices and consequently built massive amounts of technical debt that manifests within infrastructure. Some companies don’t even have a good idea of what runs where and other basic knowledge of the interactions between architecture and infrastructure.

Ultimately, the advice parallels the annoying-but-accurate consultant’s answer of It Depends! Only architects, developers, DBAs, DevOps, testing, security, and the other host of contributors can ultimately determine the best roadmap toward evolutionary architecture.

Case Study: Enterprise Architecture at PenultimateWidgets

PenultimateWidgets is considering revamping a major part of their legacy platform, and a team of enterprise architects generated a spreadsheet listing all the properties the new platform should exhibit: security, performance metrics, scalability, deployability, and a host of other properties. Each category contained 5 to 20 cells, each with some specific criteria. For example, one of the uptime metrics insisted that each service offer five nines (99.999) of availability. In total, they identified 62 discrete items.

But they realized some problems with this approach. First, would they verify each of these 62 properties on projects? They could create a policy, but who would verify that policy on an ongoing basis? Verifying all these things manually, even on an ad hoc basis, would be a considerable challenge.

Second, would it make sense to impose strict availability guidelines across every part of the system? Is it critical that the administrator’s management screens offer five nines? Creating blanket policies often leads to egregious overengineering.

To solve these problems, the enterprise architects defined their criteria as fitness functions and created a deployment pipeline template each project starts with. Within the deployment pipeline, the architects designed fitness functions to automatically check critical features such as security, leaving individual teams to add specific fitness functions (like availability) for their service.

Future State?

What is the future state of evolutionary architecture? As teams become more familiar with the ideas and practices, they will subsume them into business as usual and start using these ideas to build new capabilities, such as data-driven development.

Much work must be done around the more difficult kinds of fitness functions, but progress is already occurring as organizations solve problems and open source many of their solutions. In the early days of agility, people lamented that some problems were just too hard to automate, but intrepid developers kept chipping away and now entire data centers have succumbed to automation. For instance, Netflix has made tremendous innovations in conceptualizing and building tools like the Simian Army, supporting holistic continuous fitness functions (but not yet calling them that).

There are a couple of promising areas.

Fitness Functions Using AI

Gradually, large open source artificial intelligence frameworks are becoming available for regular projects. As developers learn to utilize these tools to support software development, we envision fitness functions based on AI that look for anomalous behavior. Credit card companies already apply heuristics such as flagging near-simultaneous transactions in different parts of the world; architects can start to build investigatory tools to look for odd behaviors in architecture.

Generative Testing

A practice common in many functional programming communities gaining wider acceptance is the idea of generative testing. Traditional unit tests include assertions of correct outcomes within each test case. However, with generative testing, developers run a large number of tests and capture the outcomes then use statistical analysis on the results to look for anomalies. For example, consider the mundane case of boundary checking ranges of numbers. Traditional unit tests check the known places where numbers break (negatives, rolling over numerical sizes, and so on) but are immune to unanticipated edge cases. Generative tests check every possible value and report on edge cases that break.

Why (or Why Not)?

No silver bullets exist, including in architecture. We don’t recommend that every project take on the extra cost and effort of evolvability unless it benefits them.

Why Should a Company Decide to Build an Evolutionary Architecture?

Many businesses find that the cycle of change has accelerated over the past few years, as reflected in the aforementioned Forbes observation that every company must be competent at software development and delivery.

Predictable versus evolvable

Many companies value long-term planning for resources and other strategic matters; companies obviously value predictability. However, because of the dynamic equilibrium of the software development ecosystem, predictability has expired. Enterprise architects may still make plans, but they may be invalidated at any moment.

Even companies in staid, established industries shouldn’t ignore the perils of systems that cannot evolve. The taxi industry was a multicentury, international institution when it was rocked by ride-sharing companies that understood and reacted to the implications of the shifting ecosystem. The phenomenon known as The Innovators Dilemma predicts that companies in well-established markets are likely to fail as more agile startups address the changing ecosystem better.

Building evolvable architecture takes extra time and effort, but the reward comes when the company can react to substantive shifts in the marketplace without major rework. Predictability will never return to the nostalgic days of mainframes and dedicated operations centers. The highly volatile nature of the development world increasingly pushes all organizations toward incremental change.

Scale

For a while, the best practice in architecture was to build transactional systems backed by relational databases, using many of the features of the database to handle coordination. The problem with that approach is scaling—it becomes hard to scale the backend database. Lots of byzantine technologies spawned to mitigate this problem, but they were only bandaids to the fundamental problem of scale: coupling. Any coupling point in an architecture eventually prevents scale, and relying on coordination at the database eventually hits a wall.

Amazon faced this exact problem. The original site was designed with a monolithic frontend tied to a monolithic backend modeled around databases. When traffic increased, they had to scale up the databases. At some point, they reached the limits of database scale, and the impact on their site was decreasing performance—every page loaded more slowly.

Amazon realized that coupling everything to one thing (whether a relational database, enterprise service bus, and so on) ultimately limited scalability. By redesigning their architecture in a more microservices style that eliminated inappropriate coupling, they allowed their overall ecosystem to scale.

A side benefit of that level of decoupling is enhanced evolvability. As we have illustrated throughout the book, inappropriate coupling represents the biggest challenge to evolution. Building a scalable system also tends to correspond to an evolvable one.

Advanced business capabilities

Many companies look with envy at Facebook, Netflix, and other cutting-edge technology companies because they have sophisticated features. Incremental change allows well-known practices such as hypotheses and data-driven development. Many companies yearn to incorporate their users into their feedback loop via multivariate testing. A key building block for many advanced DevOps practices is an architecture that can evolve. For example, developers find it difficult to perform A/B testing if a high degree of coupling exists between components, making isolation of concerns more daunting. Generally, an evolutionary architecture allows a company better technical responsiveness to inevitable but unpredictable changes.

Cycle time as a business metric

In “Deployment Pipelines”, we made the distinction between Continuous Delivery, where at least one stage in the deployment pipeline performs a manual pull, and Continuous Deployment, where every stage automatically promotes to the next upon success. Building continuous deployment takes a fair amount of engineering sophistication—why would a company go quite that far?

Because cycle time has become a business differentiator in some markets. Some large conservative organizations view software as overhead and thus try to minimize cost. Innovative companies see software as a competitive advantage. For example, if AcmeWidgets has created an architecture where the cycle time is three hours, and PenultimateWidgets still has a six-week cycle time, AcmeWidgets has an advantage they can exploit.

Many companies have made cycle time a first-class business metric, mostly because they live in a highly competitive market. All markets eventually become competitive in this way. For example, in the early 1990s, some big companies were more aggressive in moving toward automating manual workflows via software and gained a huge advantage as all companies eventually realized that necessity.

Isolating architectural characteristics at the quantum level

Thinking of traditional nonfunctional requirements as fitness functions and building a well-encapsulated architectural quantum allows architects to support different characteristics per quantum, one of the benefits of a microservices architecture. Because the technical architecture of each quantum is decoupled from other quanta, architects can choose different architectures for different use cases. For example, developers on one small service may choose a microkernel architecture because they want to support a small core that allows incremental addition. Another team of developers may choose an event-driven architecture for their service because of scalability concerns. If both services were part of a monolith, architects would have to make tradeoffs to attempt to satisfy both requirements. By isolating technical architecture at a small quantum level, architects are free to focus on the primary characteristics of a singular quantum, not analyzing the tradeoffs for competing priorities.

Case Study: Selective Scale at PenultimateWidgets

PenultimateWidgets has some services that require little in the way of scale and are therefore written in simple technology stacks. However, a couple of services stand out. The Import service must import inventory figures from brick-and-mortar stores every night for the accounting system. Thus, the architectural characteristics and fitness functions the developers built into Import include scalability and resiliency, which greatly complicate the technical architecture of that service. Another service, MarketingFeed, is typically called by each store at opening to get daily sales and marketing updates. Operationally, MarketingFeed needs elasticity to be able to handle the burst of requests as stores open across time zones.

A common problem in highly coupled architectures is inadvertent overengineering. In a more coupled architecture, developers would have to build scalability, resiliency, and elasticity into every service, complicating the ones that don’t need those capabilities. Architects are accustomed to choosing architectures against a spectrum of tradeoffs. Building architectures with clearly defined quantum boundaries allows exact specification of the required architectural characteristics.

Adaptation versus evolution

Many organizations fall into the trap of gradually increasing technical debt and reluctance to make needed restructuring modifications, which in turns makes systems and integration points increasingly brittle. Companies try to pave over this brittleness with connection tools like service buses, which alleviates some of the technical headaches but doesn’t address deeper logical cohesion of business processes. Using a service bus is an example of adapting an existing system to use in another setting. But as we’ve highlighted previously, a side effect of adaptation is increased technical debt. When developers adapt something, they preserve the original behavior and layer new behavior alongside it. The more adaptation cycles a component endures, the more parallel behavior there is, increasing complexity, hopefully strategically.

The use of feature toggles offers a good example of the benefits of adaptation. Often, developers use toggles when trying several alternate alternatives via hypotheses-driven development, testing their users to see what resonates best. In this case, the technical debt imposed by toggles is purposeful and desirable. Of course, the engineering best practices around these types of toggles is to remove them as soon as the decision is resolved.

Alternatively, evolving implies fundamental change. Building an evolvable architecture entails changing the architecture in situ, protected from breakages via fitness functions. The end result is a system that continues to evolve in useful ways without an increasing legacy of outdated solutions lurking within.

Why Would a Company Choose Not to Build an Evolutionary Architecture?

We don’t believe that evolutionary architecture is the cure for all ailments! Companies have several legitimate reasons to pass on these ideas.

Can’t evolve a ball of mud

One of the key “-ilities” architects neglect is feasibility—should the team undertake this project? If an architecture is a hopelessly coupled Big Ball of Mud, making it possible to evolve it cleanly will take an enormous amount of work—likely more than rewriting it from scratch. Companies loath throwing anything away that has perceived value, but often rework is more costly than rewrite.

How can companies tell if they’re in this situation? The first step to converting an existing architecture into an evolvable one is modularity. Thus, a developer’s first task requires finding whatever modularity exists in the current system and restructuring the architecture around those discoveries. Once the architecture becomes less entangled, it becomes easier for architects to see underlying structures and make reasonable determinations about the effort needed for restructuring.

Other architectural characteristics dominate

Evolvability is only one of many characteristics architects must weigh when choosing a particular architecture style. No architecture can fully support conflicting core goals. For example, building high performance and high scale into the same architecture is difficult. In some cases, other factors may outweigh evolutionary change.

Most of the time, architects choose an architecture for a broad set of requirements. For example, perhaps an architecture needs to support high availability, security, and scale. This leads towards general architecture patterns, such as monolith, microservices, or event-driven. However, a family of architectures known as domain-specific architectures that attempt to maximize a single characteristic.

An excellent example of a domain-specific architecture is LMAX, a custom trading solution. Their primary goal was fast transaction throughput, and they experimented with a variety of techniques with no success. Ultimately, by analyzing at the lowest level, they discovered the key to scalability was making their logic small enough to fit in the CPU’s cache, and preallocating all memory to prevent garbage collection. Their architecture achieved a stunning 6 million transactions per second on a single Java thread!

Having built their architecture for such a specific purpose, evolving it to accomodate other concerns would present difficulties (unless developers are extraordinarily lucky and architectural concerns overlap). Thus, most domain-specific architectures aren’t concerned with evolution because their specific purpose overrides other concerns.

Sacrificial architecture

Martin Fowler defined a sacrificial architecture as one designed to throw away. Many companies need to build simple versions initially to investigate a market or prove viability. Once proven, they can build the real architecture to support the characteristics that have manifested.

Many companies do this strategically. Often, companies build this type of architecture when creating a minimum viable product to test a market, anticipating building a more robust architecture if the market approves. Building a sacrificial architecture implies that architects aren’t going to try to evolve it but rather replace it at the appropriate time with something more permanent. Cloud offerings make this an attractive option for companies experimenting with the viability of a new market or offering.

Planning on closing the business soon

Evolutionary architecture helps businesses adapt to changing ecosystem forces. If a company doesn’t plan to be in business in a year, there’s no reason to build evolvability into their architecture.

Some companies are in this position; they just don’t realize it yet.

Convincing Others

Architects and developers struggle to make nontechnical managers and coworkers understand the benefits of something like evolutionary architecture. This is especially true of parts of the organization most disrupted by some of the necessary changes. For example, developers who lecture the operations group about doing their job incorrectly will generally find resistance.

We introduced the best solution to this problem in Chapter 6. Rather than try to convince reticent parts of the organization, demonstrate how these ideas improve their practices.

Case Study: Consulting Judo

A colleague was working with a big retailer trying to convince the enterprise architects and operations group to embrace more modern DevOps practices, such as automated machine provisioning, better monitoring, and so on. Yet her pleas fell on deaf ears because of two common refrains: “We don’t have time” and “Our setup is so complex, those things will never work here.”

She applied an excellent technique called consulting judo. Judo as a martial art has numerous techniques that use the opponent’s weight against them. Consulting judo entails finding a particular pain point and fixing it as an exemplar. The pain point at the retailer was QA environments: There were never enough of them. Consequently, teams would attempt to share environments, but that caused major headaches. Having found her case study, she received approval to creating QA environments using modern DevOps tools and techniques.

When she was complete, she demonstrated the falseness of both previous assumptions. Now, any team that needs a QA environment can provision one trivially. Her effort in turn convinced operations to invest more fully into modern techniques because of demonstrable value. Demonstration defeats discussion.

The Business Case

Business people are often wary of ambitious IT projects, which sound like expensive replumbing exercises. However, many businesses find that many desirable capabilities have their basis in more evolutionary architectures.

“The Future Is Already Here…”

The future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.

William Gibson

Many companies view software as overhead, like the heating system. When software architects talk to executives at those companies about innovation in software, they imagine plumbers upselling them on pretty but expensive overhead. However, that antiquated view of the strategic importance of software is discredited. Consequently, decision makers who control software purchases tend to became institutionally conservative, valuing cost savings over innovation. Enterprise architects make this mistake for understandable reasons—they look at other companies within their ecosystem to see how they approach these decisions. But that approach is dangerous because a disruptive company that has modern software architecture may move into the existing company’s realm and suddenly dominate because they have better information technology.

Moving Fast Without Breaking Things

Most large enterprises complain about the pace of change within the organization. One side effect of building an evolutionary architecture manifests as better engineering efficiency. All the practices we call incremental change improve automation and efficiency. Defining top-level enterprise architecture concerns as fitness functions both unifies a disparate set of concerns under one umbrella and forces developers to think in terms of objective outcomes.

Building an evolutionary architecture implies that teams can make incremental changes at the architectural level with confidence. In Chapter 2, we described a GitHub case study where a foundational component of an architecture with no regressions (while uncovering other undiscovered bugs). Business people fear breaking change. If developers build an architecture that allows incremental change with better confidence than older architectures, both business and engineering win.

Less Risk

With improved engineering practices comes decreased risk. Evolutionary architecture forces modern practices on teams in the guise of incremental change, a beneficial side effect. Once developers have confidence that their practices will allow them to make changes in the architecture without breaking things, companies can increase their release cadence.

New Capabilities

The best way to sell the ideas of evolutionary architecture to the business revolves around the new business capabilities it delivers, such as hypothesis-driven development. Business people glaze over when architects wax poetic about technical improvements, so it is better to couch the impact in their terms.

Building Evolutionary Architectures

Our ideas about building evolutionary architectures build upon and rely on many existing things: testing, metrics, deployment pipelines, and a host of other supporting infrastructure and innovation. We’re creating a new perspective to unify previously diversified concepts using fitness functions. For us, anything that verifies the architecture is a fitness function, and treating all those mechanisms uniformly makes automation and verification easier.

We want architects to start thinking of architectural characteristics as evaluable things rather than ad hoc aspirations, allowing them to build more resilient architectures.

Making some systems more evolvable won’t be easy, but we don’t really have a choice: The software development ecosystem is going to continue to churn out new ideas from unexpected places. Organizations who can react and thrive in that environment will have a serious advantage.